Real Time Systems Part II 1 Mutual Exclusion

- Slides: 69

Real Time Systems Part II 1

Mutual Exclusion Mutual exclusion between 2(n) tasks: while one of the tasks is in a critical section the other(s) cannot work at all or cannot proceed and operate on certain data • Critical Section: a part of the program which does something on certain data, requiring blocking other tasks to touch these data while operation is in progress – Un interrupted operation is achieved usually by priorities and not via the techniques explained here 2

Mutual Exclusion Example • An input task prepares data for a control process (three variables) • Control process is activated synchronously by the system timer, calculates a signal based on three variables S(v 1, v 2, v 3) • Exclusion has to ensure that control task awaits data input complete. • The signal S then is sent to a third process • What would happen is Control Proc. uses only partially new values? • Avoid this problem by use of critical sections 3

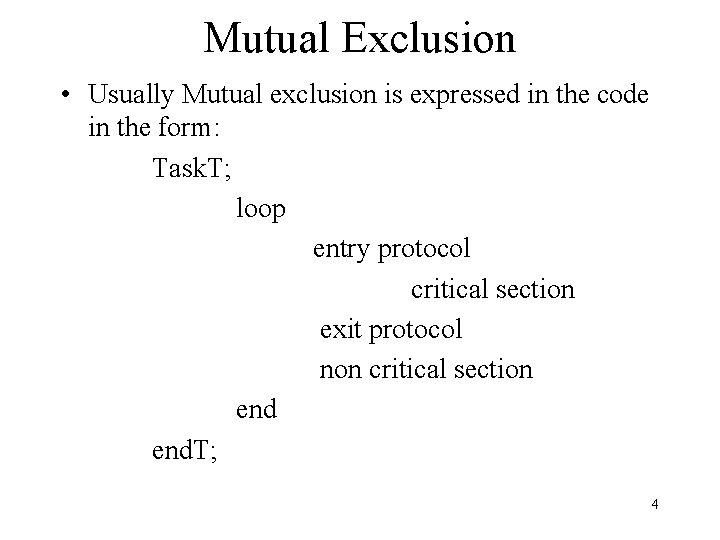

Mutual Exclusion • Usually Mutual exclusion is expressed in the code in the form: Task. T; loop entry protocol critical section exit protocol non critical section end. T; 4

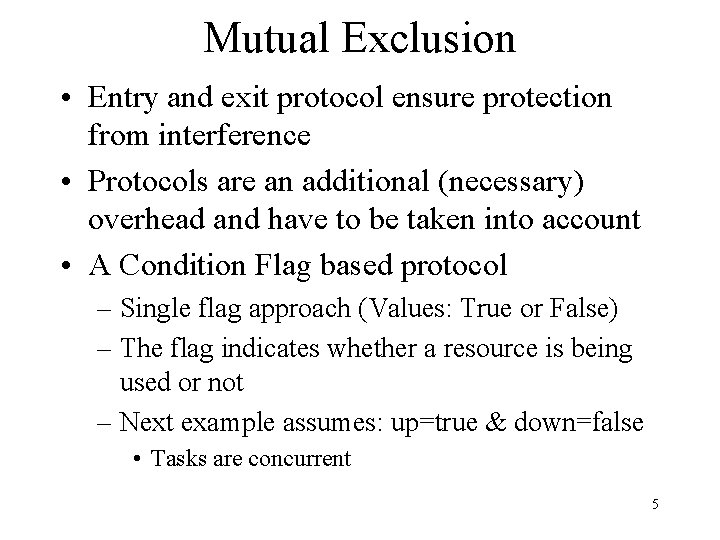

Mutual Exclusion • Entry and exit protocol ensure protection from interference • Protocols are an additional (necessary) overhead and have to be taken into account • A Condition Flag based protocol – Single flag approach (Values: True or False) – The flag indicates whether a resource is being used or not – Next example assumes: up=true & down=false • Tasks are concurrent 5

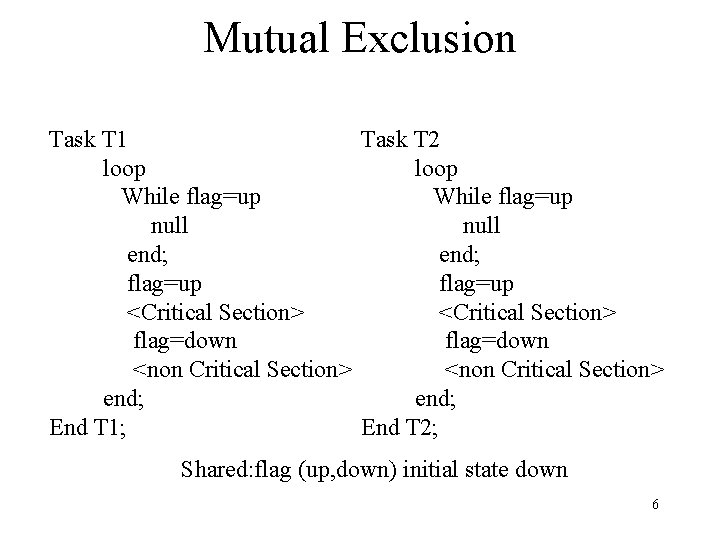

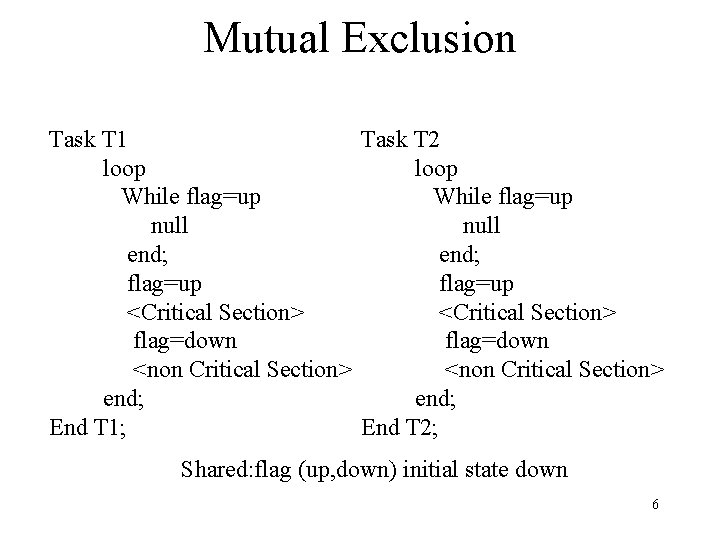

Mutual Exclusion Task T 1 Task T 2 loop While flag=up null end; flag=up <Critical Section> flag=down <non Critical Section> end; End T 1; End T 2; Shared: flag (up, down) initial state down 6

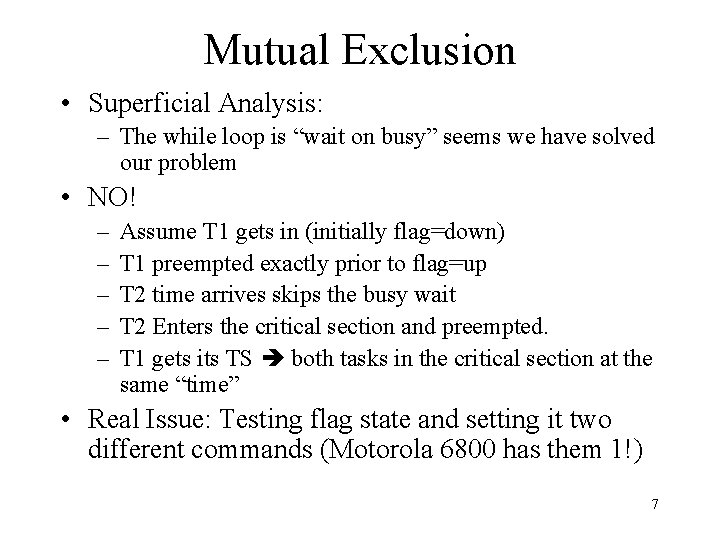

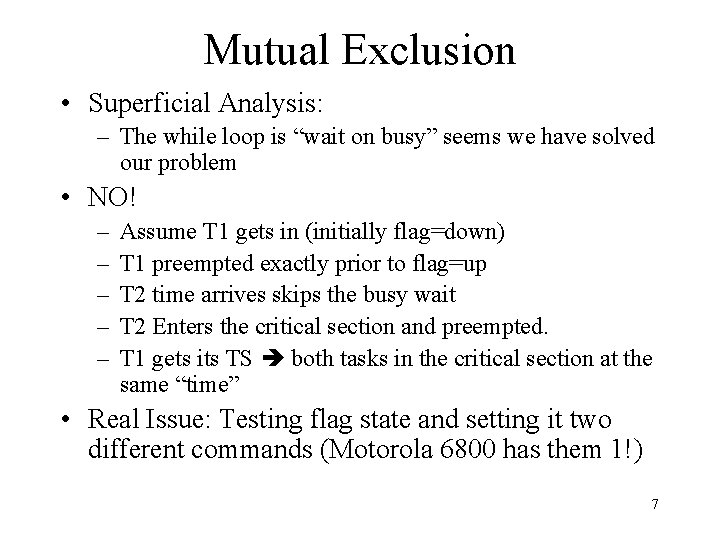

Mutual Exclusion • Superficial Analysis: – The while loop is “wait on busy” seems we have solved our problem • NO! – – – Assume T 1 gets in (initially flag=down) T 1 preempted exactly prior to flag=up T 2 time arrives skips the busy wait T 2 Enters the critical section and preempted. T 1 gets its TS both tasks in the critical section at the same “time” • Real Issue: Testing flag state and setting it two different commands (Motorola 6800 has them 1!) 7

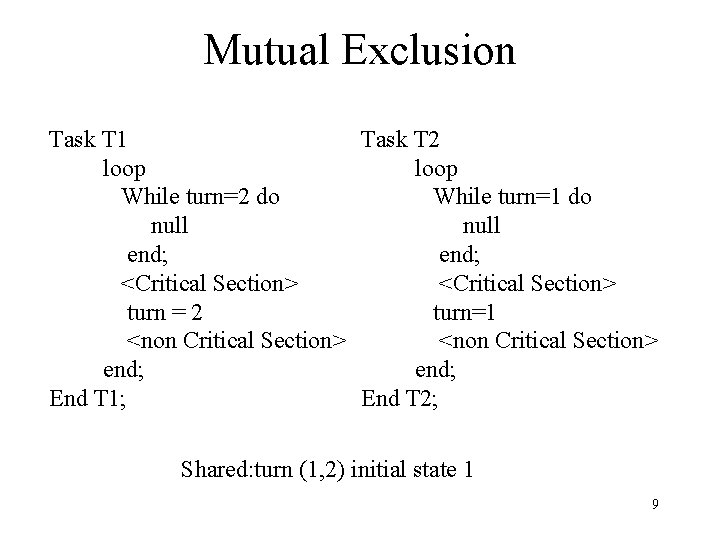

Mutual Exclusion • Last example sensed resource free, a better way ensure who runs next • Task knows whether the other Task is first or second • A better solution: A task can run only after its “turn” is signaled! • Hence the name “Flag with a turn” 8

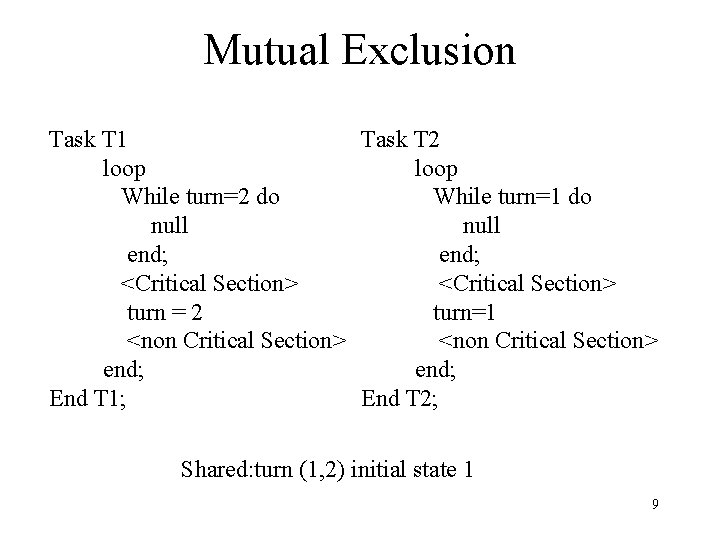

Mutual Exclusion Task T 1 Task T 2 loop While turn=2 do While turn=1 do null end; <Critical Section> turn = 2 turn=1 <non Critical Section> end; End T 1; End T 2; Shared: turn (1, 2) initial state 1 9

Mutual Exclusion • Tasks run only according to a predefined order! • Single Flag solution is forbidden on ground of security • Turn solution major draw backs (applies to flag too) – Efficiency: Waste of CPU spend a considerable time in checking states (polling!) – Blocking: If any task stops the other is blocked! 10

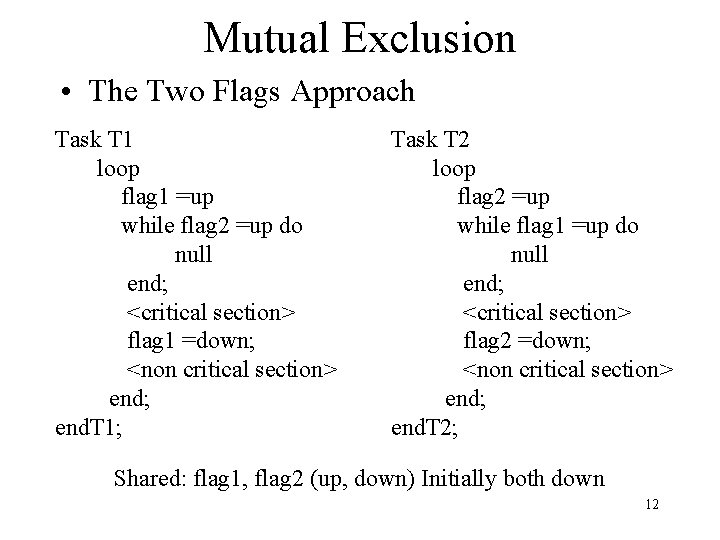

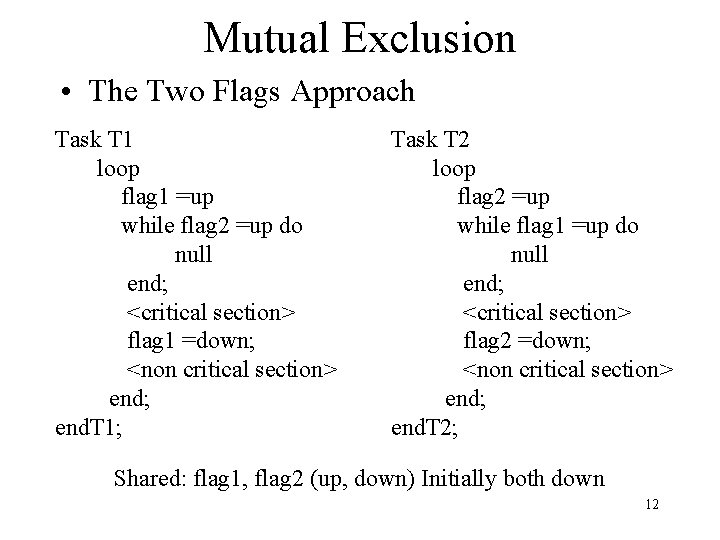

Mutual Exclusion • The Two Flags Approach – One flag per Task – Each Task sets its flag so the other enters busy wait – Seems to be better (solves synchronization? ) – Not so! (next example) – Assumptions: we have tasks T 1 and T 2 each sets its own flag (flag 1 and flag 2) – Each enters waits busy while the other one is in the critical section 11

Mutual Exclusion • The Two Flags Approach Task T 1 loop flag 1 =up while flag 2 =up do null end; <critical section> flag 1 =down; <non critical section> end; end. T 1; Task T 2 loop flag 2 =up while flag 1 =up do null end; <critical section> flag 2 =down; <non critical section> end; end. T 2; Shared: flag 1, flag 2 (up, down) Initially both down 12

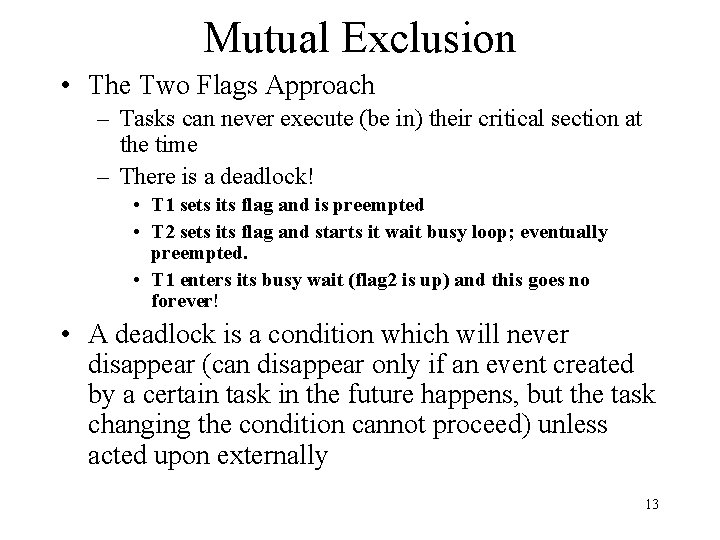

Mutual Exclusion • The Two Flags Approach – Tasks can never execute (be in) their critical section at the time – There is a deadlock! • T 1 sets its flag and is preempted • T 2 sets its flag and starts it wait busy loop; eventually preempted. • T 1 enters its busy wait (flag 2 is up) and this goes no forever! • A deadlock is a condition which will never disappear (can disappear only if an event created by a certain task in the future happens, but the task changing the condition cannot proceed) unless acted upon externally 13

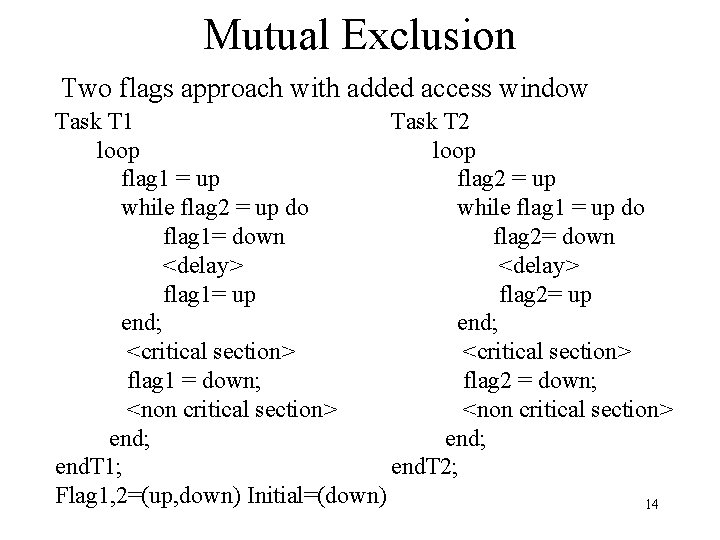

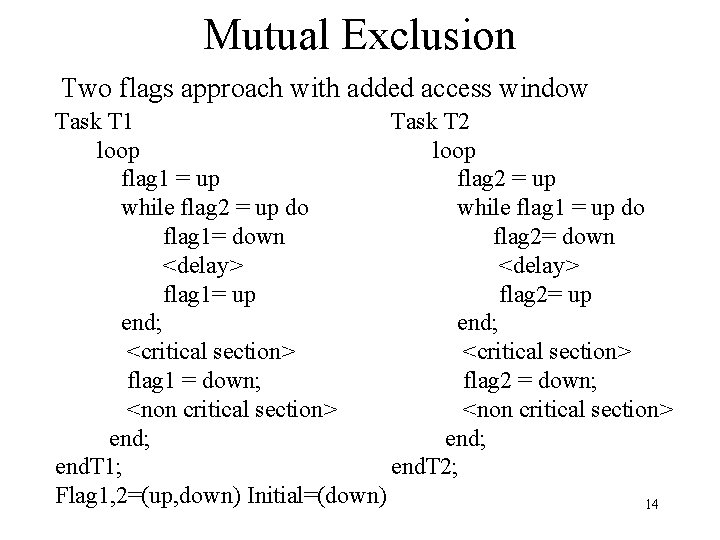

Mutual Exclusion Two flags approach with added access window Task T 1 Task T 2 loop flag 1 = up flag 2 = up while flag 2 = up do while flag 1 = up do flag 1= down flag 2= down <delay> flag 1= up flag 2= up end; <critical section> flag 1 = down; flag 2 = down; <non critical section> end; end. T 1; end. T 2; Flag 1, 2=(up, down) Initial=(down) 14

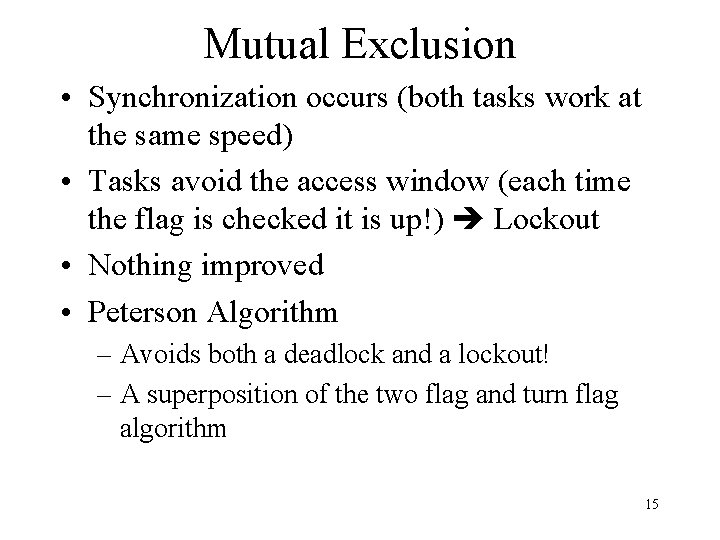

Mutual Exclusion • Synchronization occurs (both tasks work at the same speed) • Tasks avoid the access window (each time the flag is checked it is up!) Lockout • Nothing improved • Peterson Algorithm – Avoids both a deadlock and a lockout! – A superposition of the two flag and turn flag algorithm 15

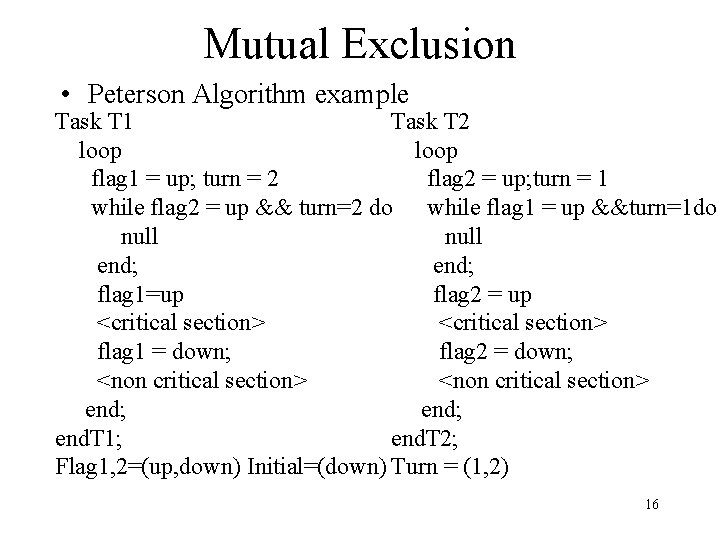

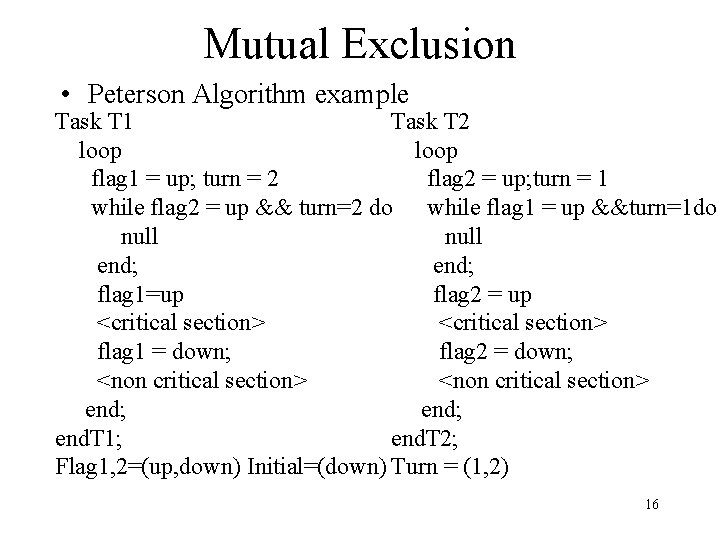

Mutual Exclusion • Peterson Algorithm example Task T 1 Task T 2 loop flag 1 = up; turn = 2 flag 2 = up; turn = 1 while flag 2 = up && turn=2 do while flag 1 = up &&turn=1 do null end; flag 1=up flag 2 = up <critical section> flag 1 = down; flag 2 = down; <non critical section> end; end. T 1; end. T 2; Flag 1, 2=(up, down) Initial=(down) Turn = (1, 2) 16

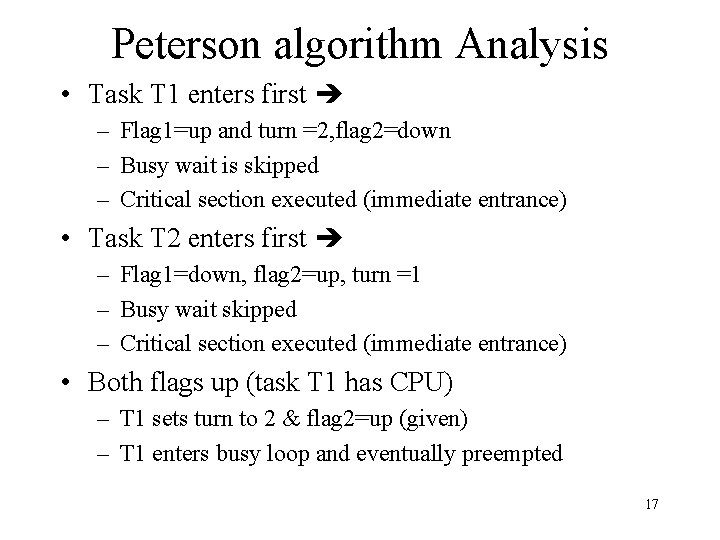

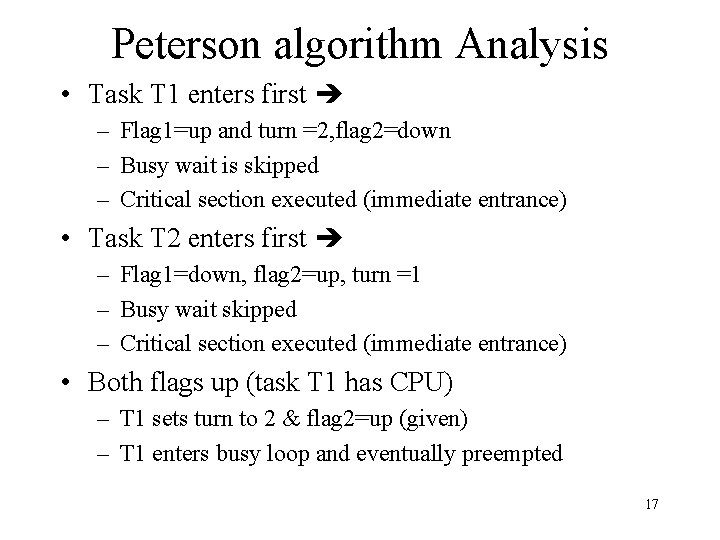

Peterson algorithm Analysis • Task T 1 enters first – Flag 1=up and turn =2, flag 2=down – Busy wait is skipped – Critical section executed (immediate entrance) • Task T 2 enters first – Flag 1=down, flag 2=up, turn =1 – Busy wait skipped – Critical section executed (immediate entrance) • Both flags up (task T 1 has CPU) – T 1 sets turn to 2 & flag 2=up (given) – T 1 enters busy loop and eventually preempted 17

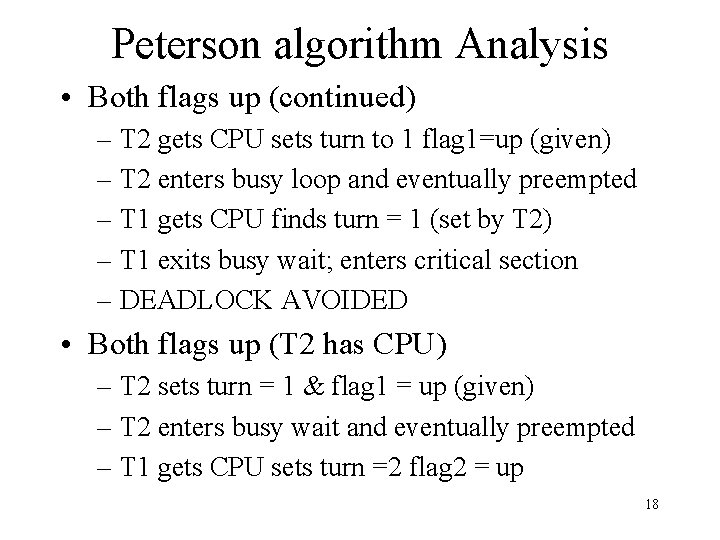

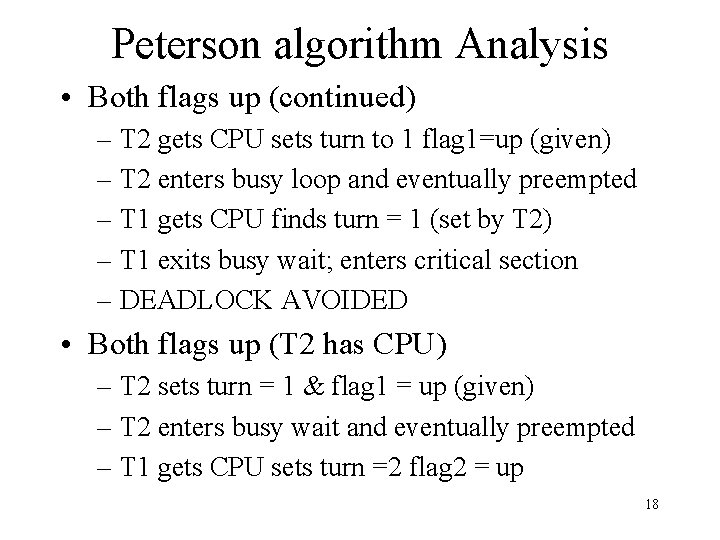

Peterson algorithm Analysis • Both flags up (continued) – T 2 gets CPU sets turn to 1 flag 1=up (given) – T 2 enters busy loop and eventually preempted – T 1 gets CPU finds turn = 1 (set by T 2) – T 1 exits busy wait; enters critical section – DEADLOCK AVOIDED • Both flags up (T 2 has CPU) – T 2 sets turn = 1 & flag 1 = up (given) – T 2 enters busy wait and eventually preempted – T 1 gets CPU sets turn =2 flag 2 = up 18

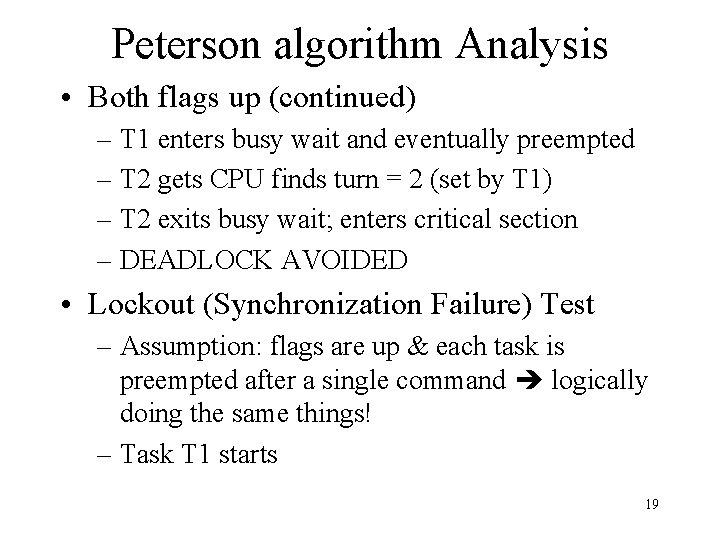

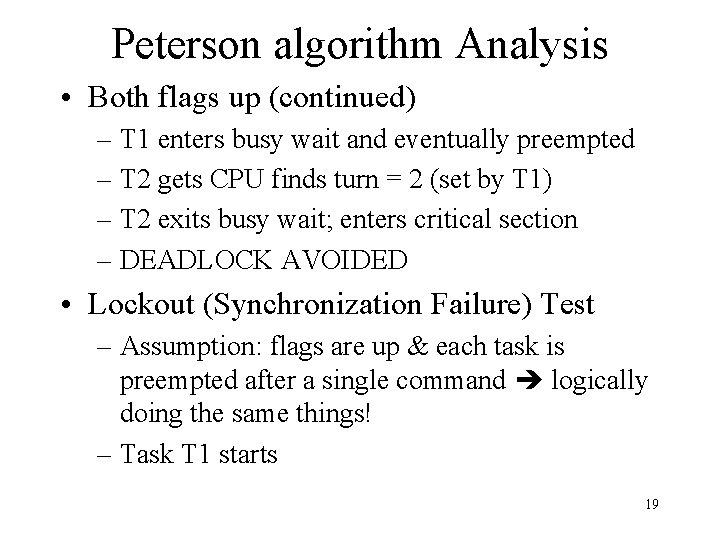

Peterson algorithm Analysis • Both flags up (continued) – T 1 enters busy wait and eventually preempted – T 2 gets CPU finds turn = 2 (set by T 1) – T 2 exits busy wait; enters critical section – DEADLOCK AVOIDED • Lockout (Synchronization Failure) Test – Assumption: flags are up & each task is preempted after a single command logically doing the same things! – Task T 1 starts 19

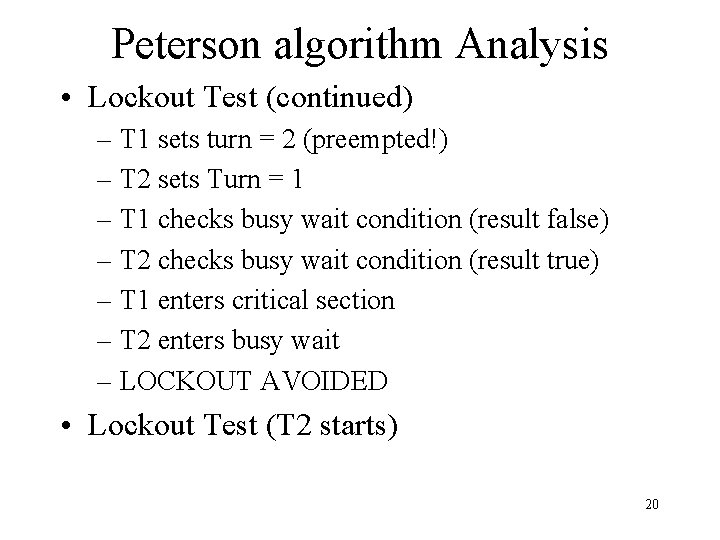

Peterson algorithm Analysis • Lockout Test (continued) – T 1 sets turn = 2 (preempted!) – T 2 sets Turn = 1 – T 1 checks busy wait condition (result false) – T 2 checks busy wait condition (result true) – T 1 enters critical section – T 2 enters busy wait – LOCKOUT AVOIDED • Lockout Test (T 2 starts) 20

Peterson algorithm Analysis • Lockout Test (continued) – T 2 sets turn = 1 (preempted!) – T 1 sets turn = 2 – T 2 checks busy wait condition (result false) – T 1 checks busy wait condition (result true) – T 2 enters critical section – T 1 enters busy wait – LOCKOUT AVOIDED • Method is good and safe • Clutters program with all flags A non trivial bug source 21

Mutual Exclusion • Semaphores are maintained by OS • Have well defined access and operational functions • Developed by Dijkstra to reduce program clutter • Semaphores are: protected variables which can be accessed by clearly specified operations 22

Mutual Exclusion • Semaphore Goals: – Provide synchronization mechanism independent of computer architecture – Be easy to use and hence simplify concurrent programming problems – Avoid in efficiencies (waste of CPU) of internal busy loops • Semaphore kinds: binary and counters – Binary has values 0, 1(true false) – Counters by definition have values from 0 to N 23

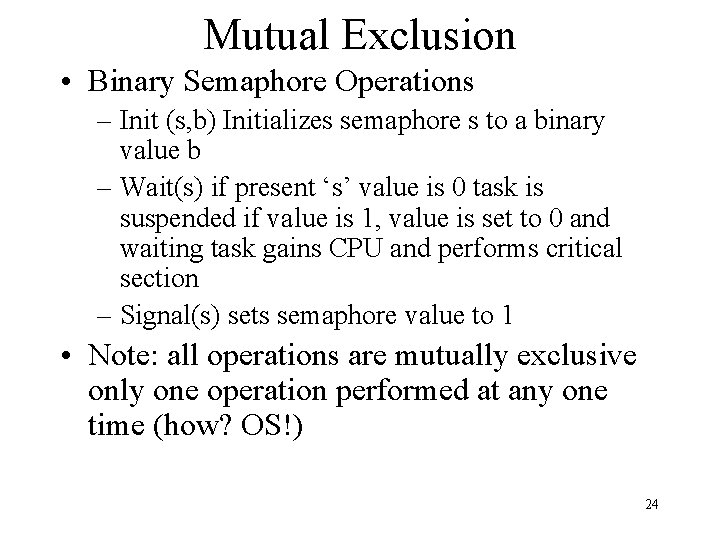

Mutual Exclusion • Binary Semaphore Operations – Init (s, b) Initializes semaphore s to a binary value b – Wait(s) if present ‘s’ value is 0 task is suspended if value is 1, value is set to 0 and waiting task gains CPU and performs critical section – Signal(s) sets semaphore value to 1 • Note: all operations are mutually exclusive only one operation performed at any one time (how? OS!) 24

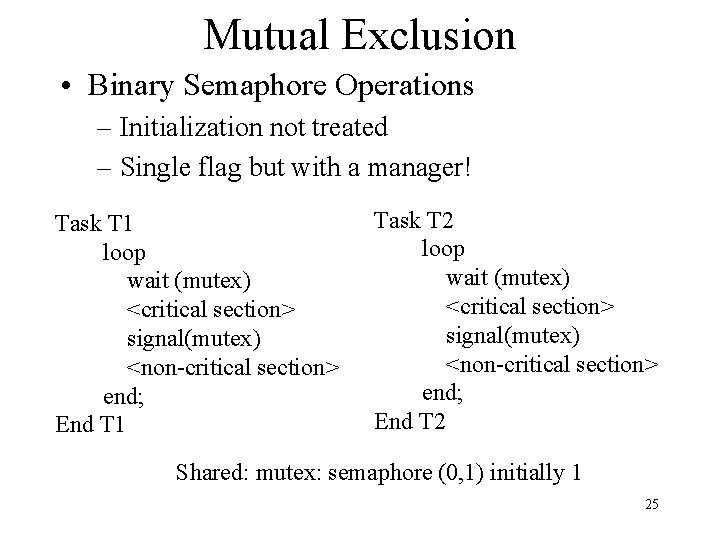

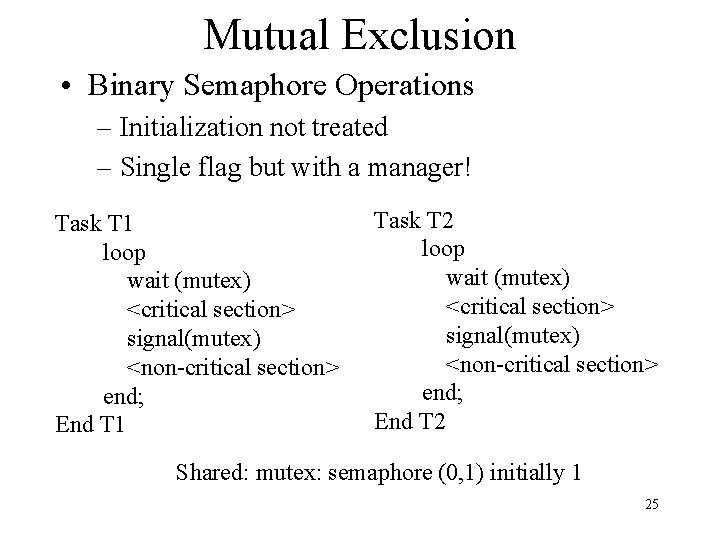

Mutual Exclusion • Binary Semaphore Operations – Initialization not treated – Single flag but with a manager! Task T 1 loop wait (mutex) <critical section> signal(mutex) <non-critical section> end; End T 1 Task T 2 loop wait (mutex) <critical section> signal(mutex) <non-critical section> end; End T 2 Shared: mutex: semaphore (0, 1) initially 1 25

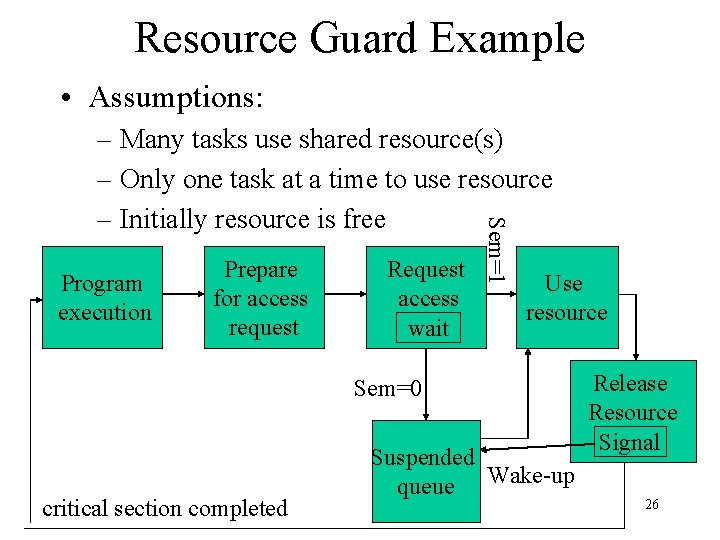

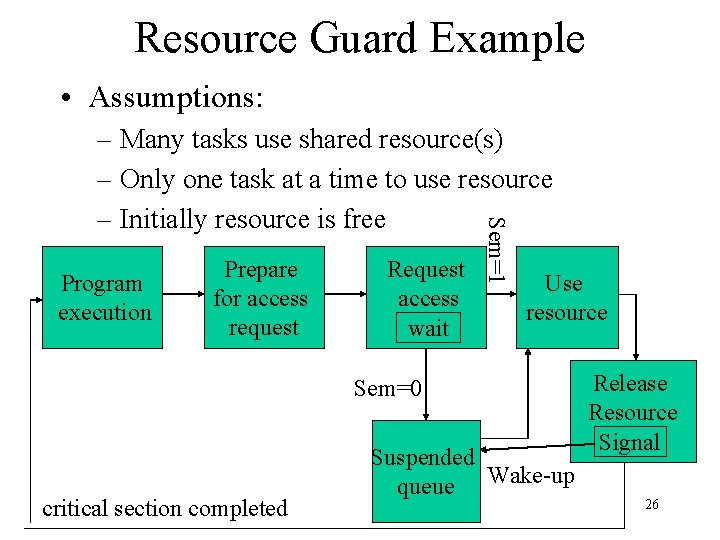

Resource Guard Example • Assumptions: Program execution Prepare for access request Request access wait Sem=1 – Many tasks use shared resource(s) – Only one task at a time to use resource – Initially resource is free Use resource Sem=0 critical section completed Suspended queue Wake-up Release Resource Signal 26

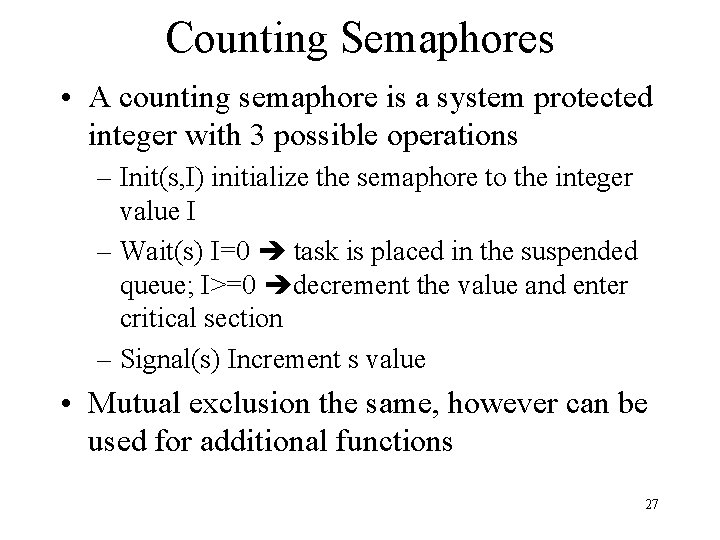

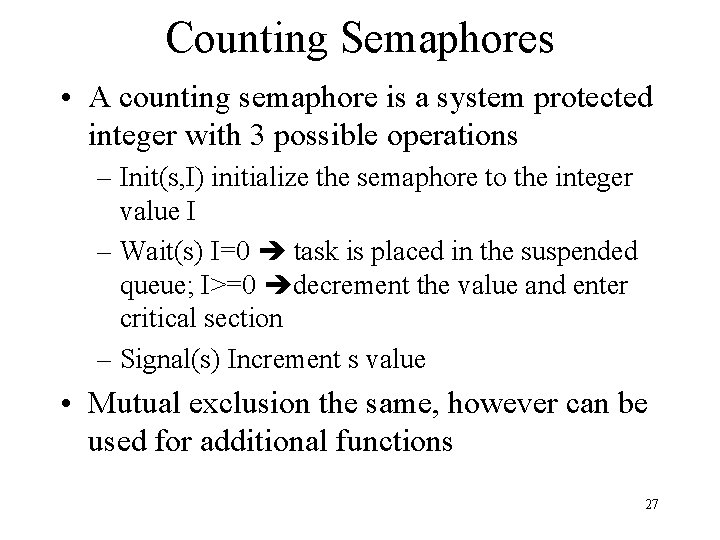

Counting Semaphores • A counting semaphore is a system protected integer with 3 possible operations – Init(s, I) initialize the semaphore to the integer value I – Wait(s) I=0 task is placed in the suspended queue; I>=0 decrement the value and enter critical section – Signal(s) Increment s value • Mutual exclusion the same, however can be used for additional functions 27

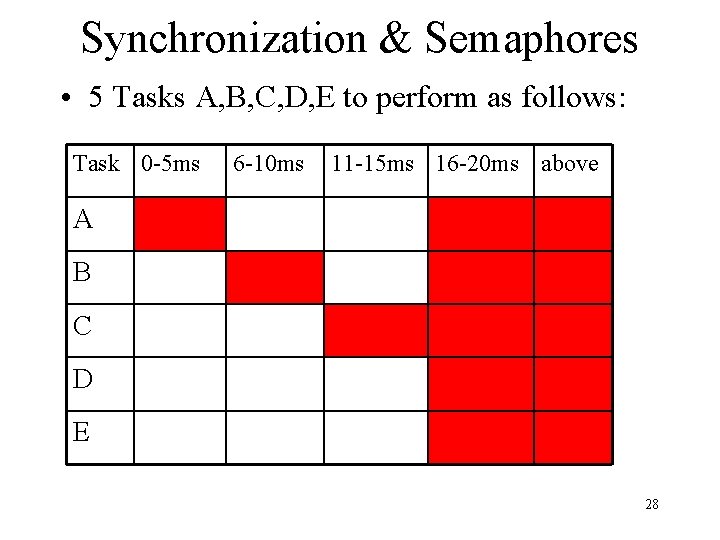

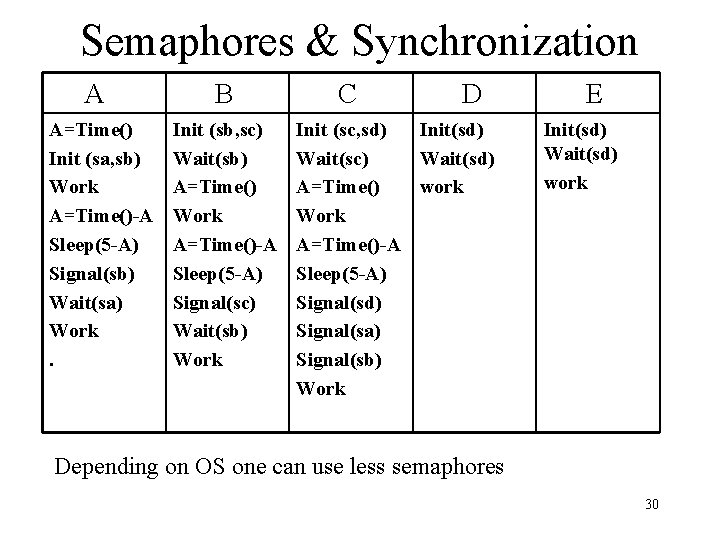

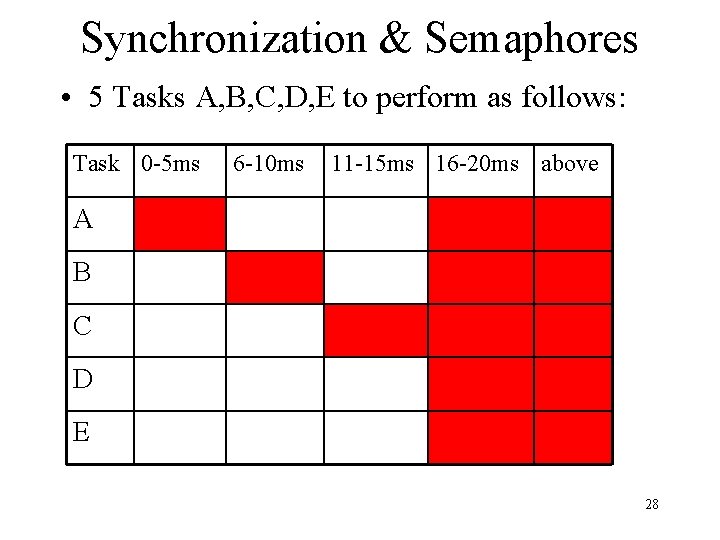

Synchronization & Semaphores • 5 Tasks A, B, C, D, E to perform as follows: Task 0 -5 ms 6 -10 ms 11 -15 ms 16 -20 ms above A B C D E 28

Semaphores & Synchronization • Example (continued) – Tasks can be scheduled by OS in any order – Timing is important! – Concurrency is determined by OS – Red means executing • Two different flags: Semaphore and time • Assume TS more than time to signal() but less than 5 ms else timing will not be exact! 29

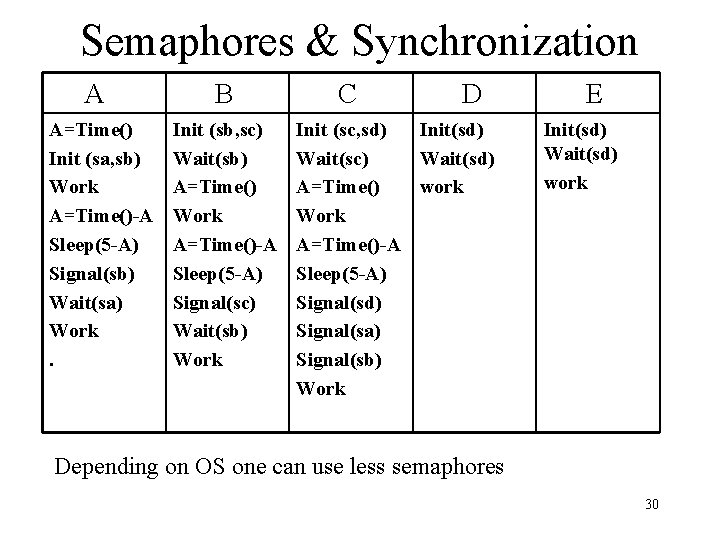

Semaphores & Synchronization A A=Time() Init (sa, sb) Work A=Time()-A Sleep(5 -A) Signal(sb) Wait(sa) Work. B Init (sb, sc) Wait(sb) A=Time() Work A=Time()-A Sleep(5 -A) Signal(sc) Wait(sb) Work C D Init (sc, sd) Init(sd) Wait(sc) Wait(sd) A=Time() work Work A=Time()-A Sleep(5 -A) Signal(sd) Signal(sa) Signal(sb) Work E Init(sd) Wait(sd) work Depending on OS one can use less semaphores 30

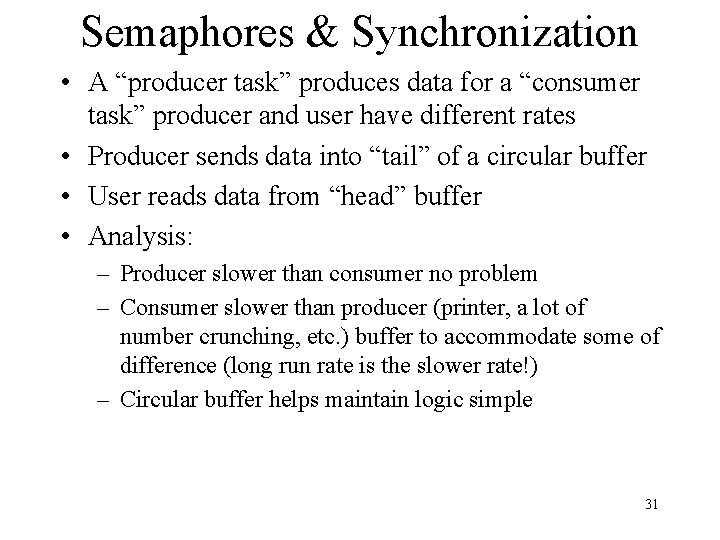

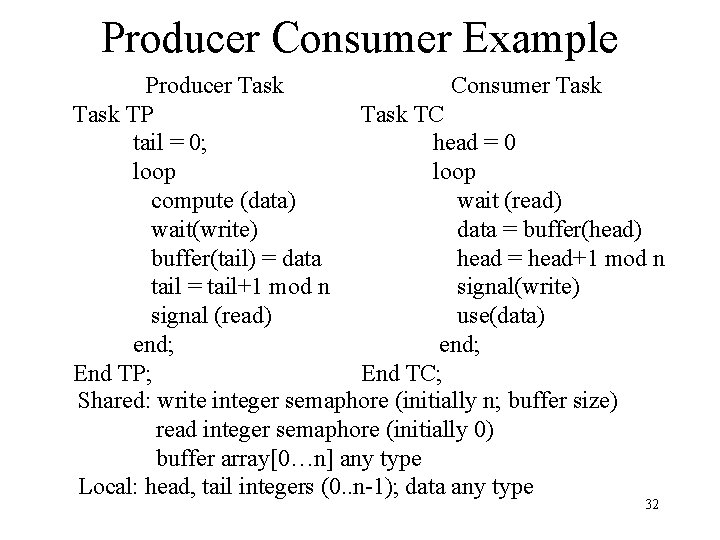

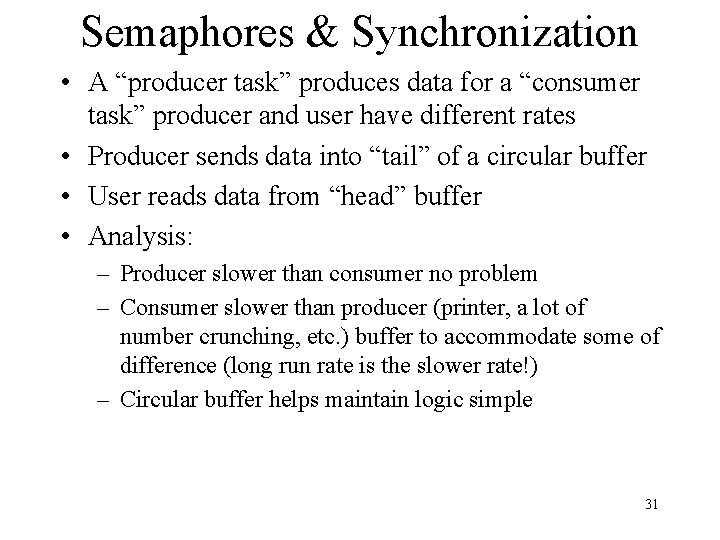

Semaphores & Synchronization • A “producer task” produces data for a “consumer task” producer and user have different rates • Producer sends data into “tail” of a circular buffer • User reads data from “head” buffer • Analysis: – Producer slower than consumer no problem – Consumer slower than producer (printer, a lot of number crunching, etc. ) buffer to accommodate some of difference (long run rate is the slower rate!) – Circular buffer helps maintain logic simple 31

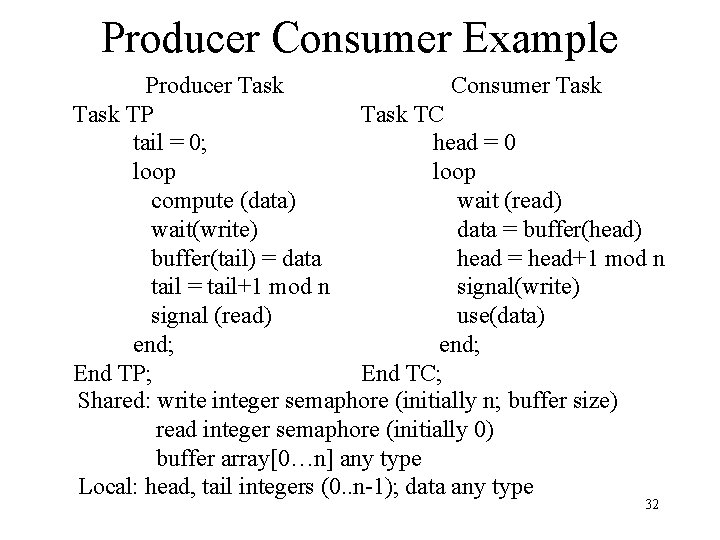

Producer Consumer Example Producer Task Consumer Task TP Task TC tail = 0; head = 0 loop compute (data) wait (read) wait(write) data = buffer(head) buffer(tail) = data head = head+1 mod n tail = tail+1 mod n signal(write) signal (read) use(data) end; End TP; End TC; Shared: write integer semaphore (initially n; buffer size) read integer semaphore (initially 0) buffer array[0…n] any type Local: head, tail integers (0. . n-1); data any type 32

Producer Consumer Example • Design analysis: – Circular buffer achieved via mod function – Insertion and removal locations independent – Integer semaphores increased according to available space and removal! – Once buffer full synchronization achieved! regardless of scheduler – Semaphores do not go beyond limits 33

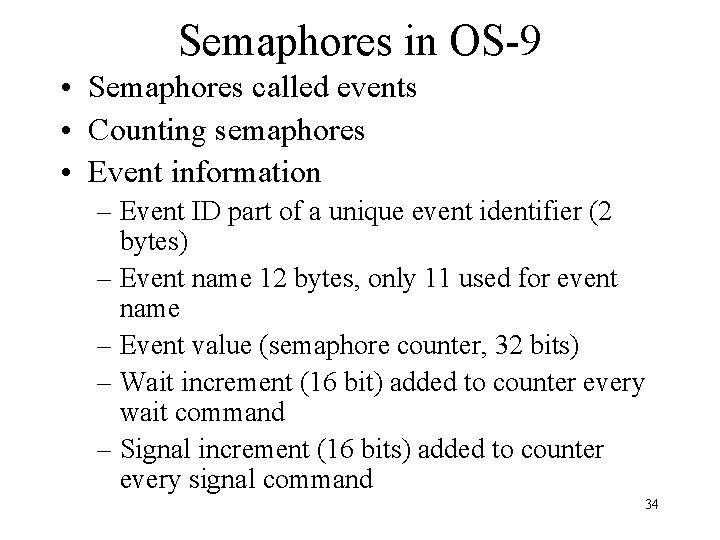

Semaphores in OS-9 • Semaphores called events • Counting semaphores • Event information – Event ID part of a unique event identifier (2 bytes) – Event name 12 bytes, only 11 used for event name – Event value (semaphore counter, 32 bits) – Wait increment (16 bit) added to counter every wait command – Signal increment (16 bits) added to counter every signal command 34

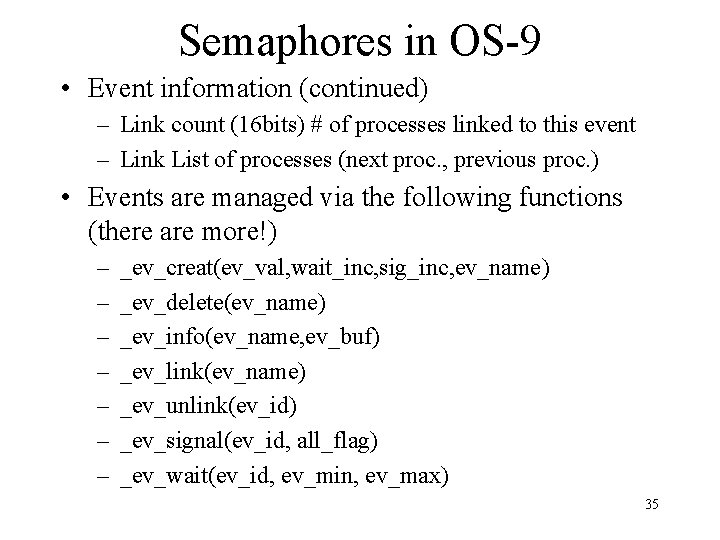

Semaphores in OS-9 • Event information (continued) – Link count (16 bits) # of processes linked to this event – Link List of processes (next proc. , previous proc. ) • Events are managed via the following functions (there are more!) – – – – _ev_creat(ev_val, wait_inc, sig_inc, ev_name) _ev_delete(ev_name) _ev_info(ev_name, ev_buf) _ev_link(ev_name) _ev_unlink(ev_id) _ev_signal(ev_id, all_flag) _ev_wait(ev_id, ev_min, ev_max) 35

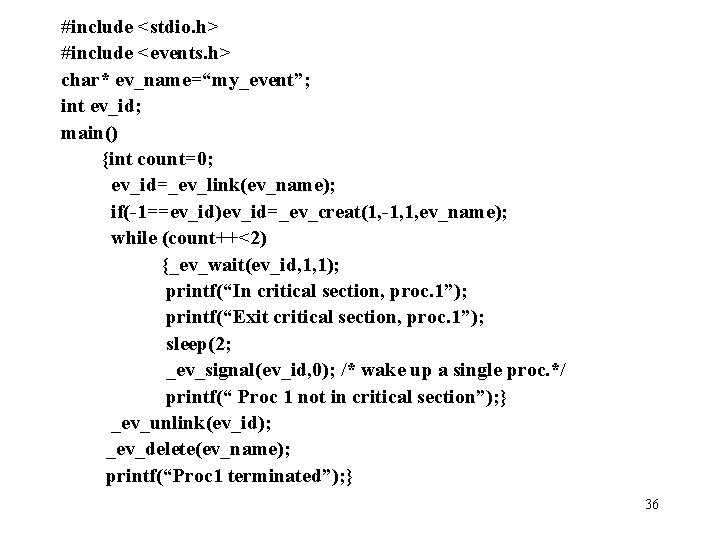

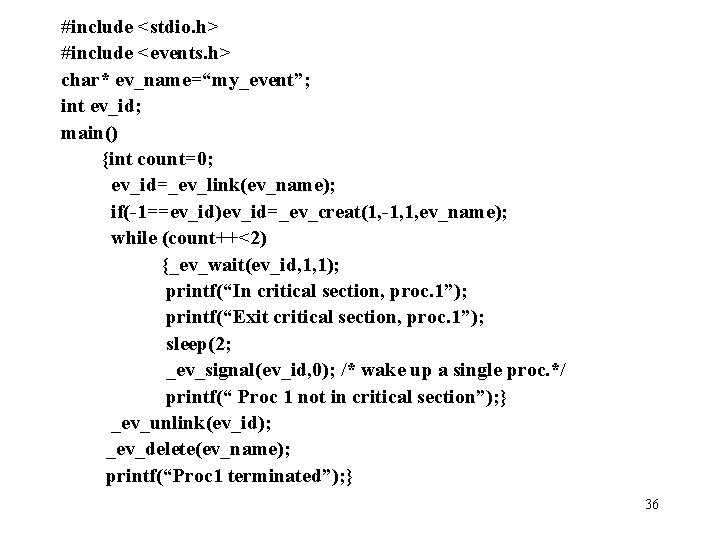

#include <stdio. h> #include <events. h> char* ev_name=“my_event”; int ev_id; main() {int count=0; ev_id=_ev_link(ev_name); if(-1==ev_id)ev_id=_ev_creat(1, -1, 1, ev_name); while (count++<2) {_ev_wait(ev_id, 1, 1); printf(“In critical section, proc. 1”); printf(“Exit critical section, proc. 1”); sleep(2; _ev_signal(ev_id, 0); /* wake up a single proc. */ printf(“ Proc 1 not in critical section”); } _ev_unlink(ev_id); _ev_delete(ev_name); printf(“Proc 1 terminated”); } 36

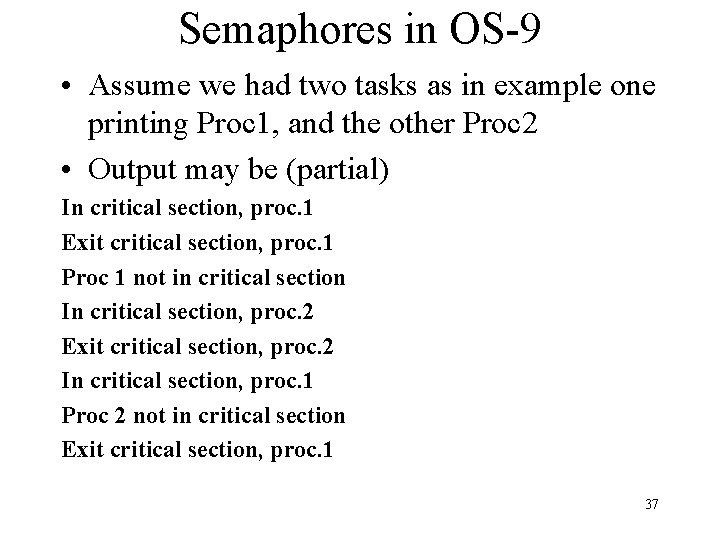

Semaphores in OS-9 • Assume we had two tasks as in example one printing Proc 1, and the other Proc 2 • Output may be (partial) In critical section, proc. 1 Exit critical section, proc. 1 Proc 1 not in critical section In critical section, proc. 2 Exit critical section, proc. 2 In critical section, proc. 1 Proc 2 not in critical section Exit critical section, proc. 1 37

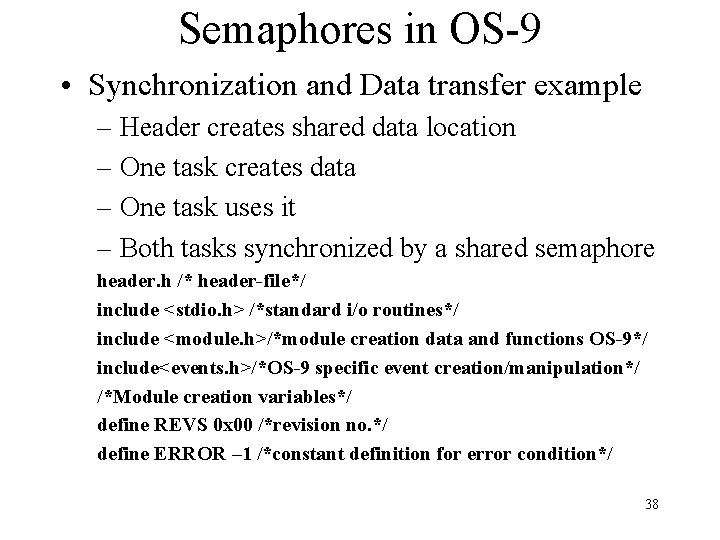

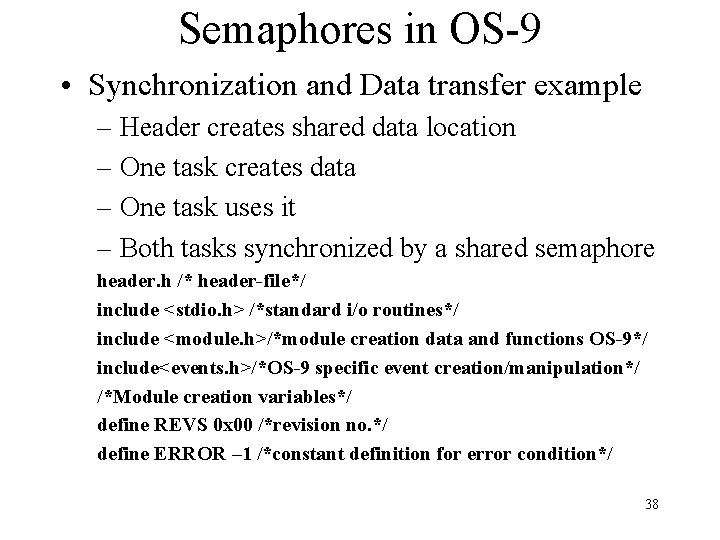

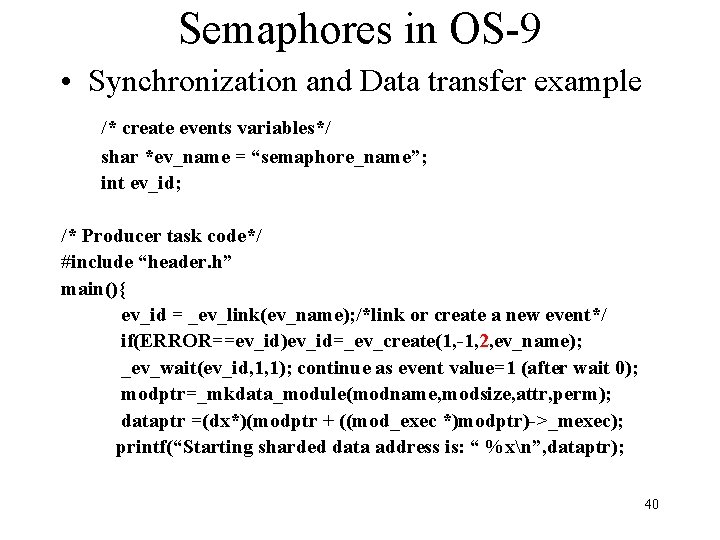

Semaphores in OS-9 • Synchronization and Data transfer example – Header creates shared data location – One task creates data – One task uses it – Both tasks synchronized by a shared semaphore header. h /* header-file*/ include <stdio. h> /*standard i/o routines*/ include <module. h>/*module creation data and functions OS-9*/ include<events. h>/*OS-9 specific event creation/manipulation*/ /*Module creation variables*/ define REVS 0 x 00 /*revision no. */ define ERROR – 1 /*constant definition for error condition*/ 38

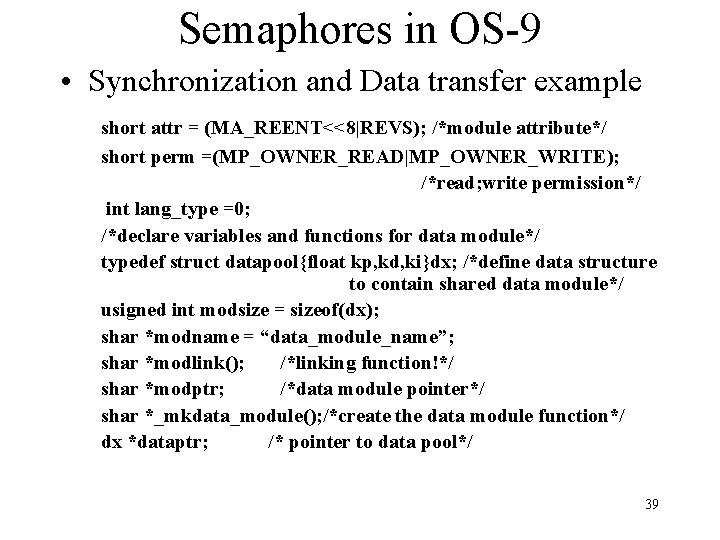

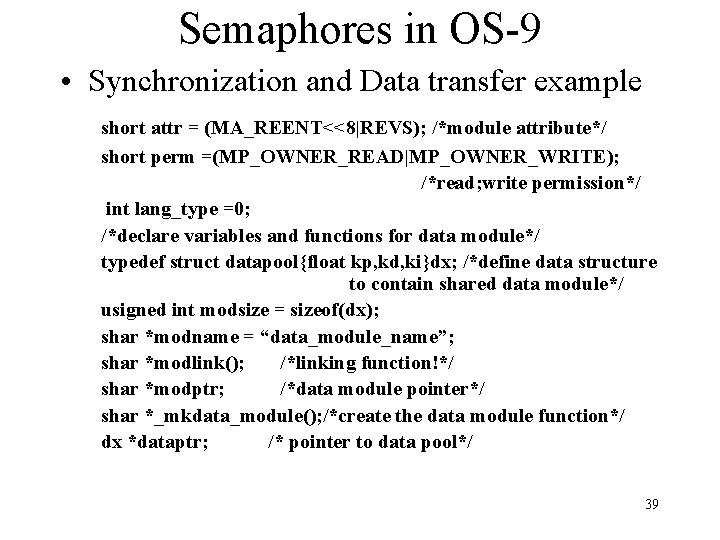

Semaphores in OS-9 • Synchronization and Data transfer example short attr = (MA_REENT<<8|REVS); /*module attribute*/ short perm =(MP_OWNER_READ|MP_OWNER_WRITE); /*read; write permission*/ int lang_type =0; /*declare variables and functions for data module*/ typedef struct datapool{float kp, kd, ki}dx; /*define data structure to contain shared data module*/ usigned int modsize = sizeof(dx); shar *modname = “data_module_name”; shar *modlink(); /*linking function!*/ shar *modptr; /*data module pointer*/ shar *_mkdata_module(); /*create the data module function*/ dx *dataptr; /* pointer to data pool*/ 39

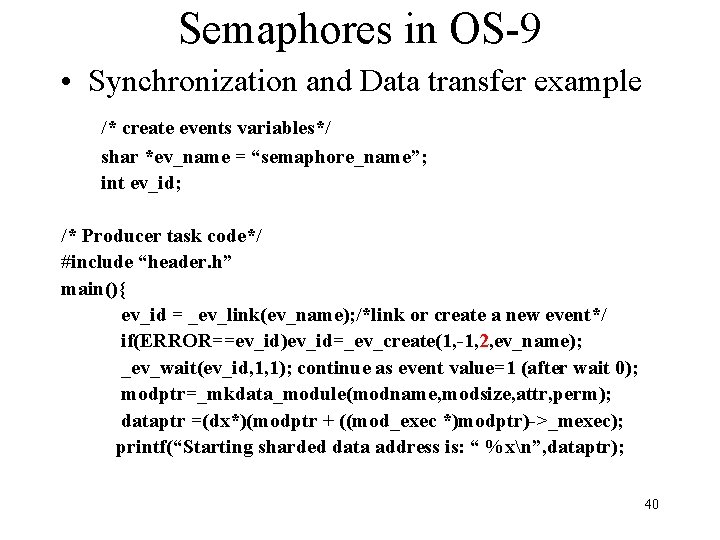

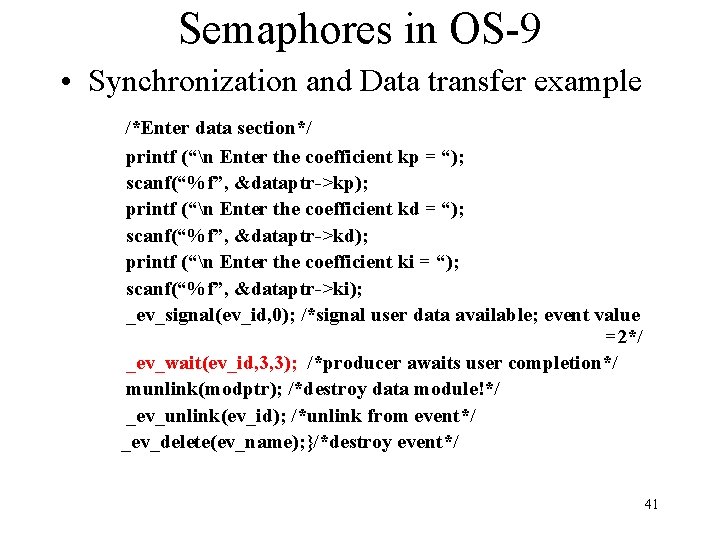

Semaphores in OS-9 • Synchronization and Data transfer example /* create events variables*/ shar *ev_name = “semaphore_name”; int ev_id; /* Producer task code*/ #include “header. h” main(){ ev_id = _ev_link(ev_name); /*link or create a new event*/ if(ERROR==ev_id)ev_id=_ev_create(1, -1, 2, ev_name); _ev_wait(ev_id, 1, 1); continue as event value=1 (after wait 0); modptr=_mkdata_module(modname, modsize, attr, perm); dataptr =(dx*)(modptr + ((mod_exec *)modptr)->_mexec); printf(“Starting sharded data address is: “ %xn”, dataptr); 40

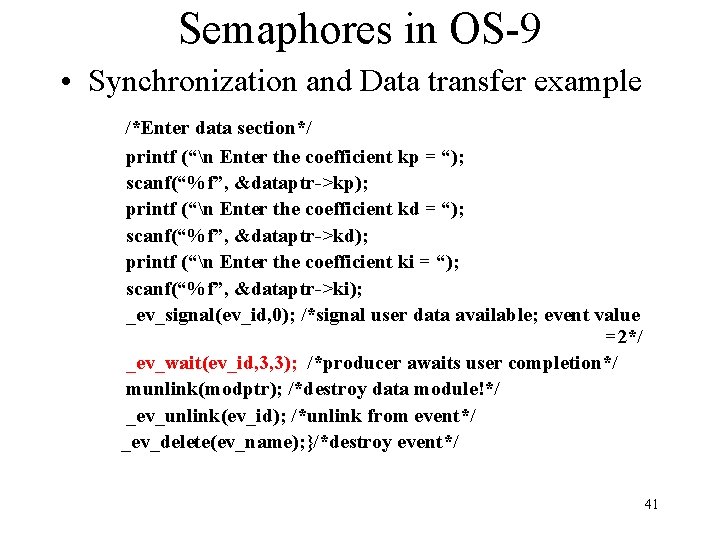

Semaphores in OS-9 • Synchronization and Data transfer example /*Enter data section*/ printf (“n Enter the coefficient kp = “); scanf(“%f”, &dataptr->kp); printf (“n Enter the coefficient kd = “); scanf(“%f”, &dataptr->kd); printf (“n Enter the coefficient ki = “); scanf(“%f”, &dataptr->ki); _ev_signal(ev_id, 0); /*signal user data available; event value =2*/ _ev_wait(ev_id, 3, 3); /*producer awaits user completion*/ munlink(modptr); /*destroy data module!*/ _ev_unlink(ev_id); /*unlink from event*/ _ev_delete(ev_name); }/*destroy event*/ 41

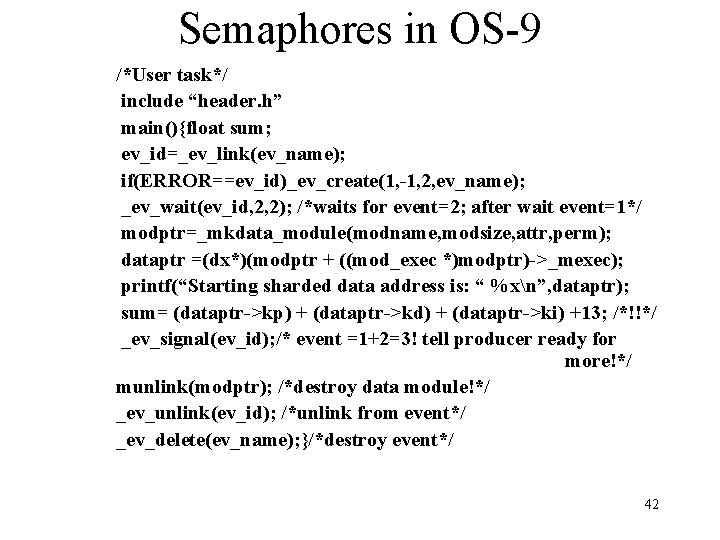

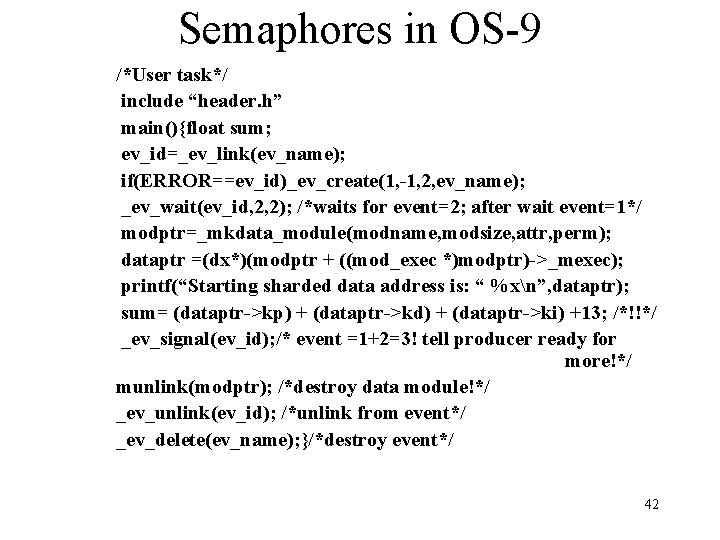

Semaphores in OS-9 /*User task*/ include “header. h” main(){float sum; ev_id=_ev_link(ev_name); if(ERROR==ev_id)_ev_create(1, -1, 2, ev_name); _ev_wait(ev_id, 2, 2); /*waits for event=2; after wait event=1*/ modptr=_mkdata_module(modname, modsize, attr, perm); dataptr =(dx*)(modptr + ((mod_exec *)modptr)->_mexec); printf(“Starting sharded data address is: “ %xn”, dataptr); sum= (dataptr->kp) + (dataptr->kd) + (dataptr->ki) +13; /*!!*/ _ev_signal(ev_id); /* event =1+2=3! tell producer ready for more!*/ munlink(modptr); /*destroy data module!*/ _ev_unlink(ev_id); /*unlink from event*/ _ev_delete(ev_name); }/*destroy event*/ 42

Faults in RT Systems • Definition: A fault is a system deviation from the system’s specified behavior • RT systems should have: – – Regular bugs Inability to discriminate faulty input Wrong timing Inadequate fault recovery • Faults (errors) sources vary and include: – Inadequate specifications – HW and (or) SW design errors – Failure of one component (HW, SW) 43

Faults in RT Systems • Faults sources (continued) – Transient or permanent stress (causing wrong behavior) – Misuse by operators (acting wrongly, overriding system’s suggestion) • Eliminating or minimizing errors – Specifications • Should be: complete; consistent; comprehensible; detailed (unambiguous) • Use of standards, inspections, and tools help • Rarely specifications cover all faults behavior and timings as it is very difficult 44

Faults in RT Systems • Eliminating or minimizing errors – Design • Use of design methodologies (Structured, OOD, Formal specification languages (B, Z) help • Use of standards, inspections, and tools help • Testing removes errors introduced however it is long and costly! • Testing finds only what we look for! • Not finding problems does not guaranty their absence! 45

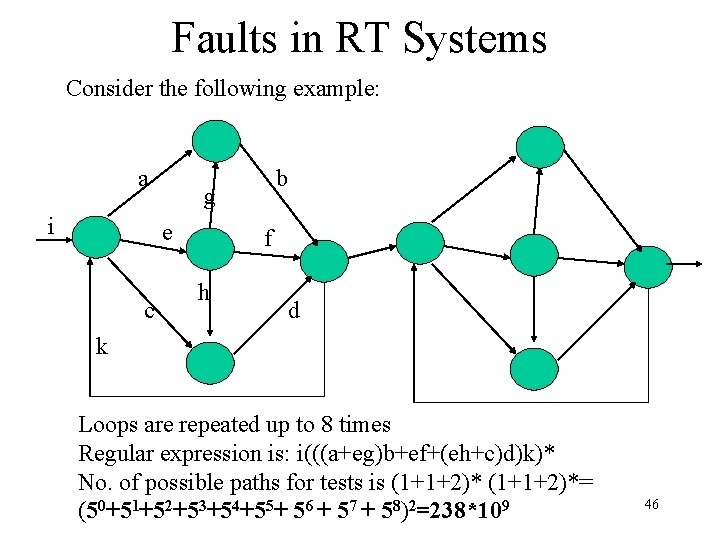

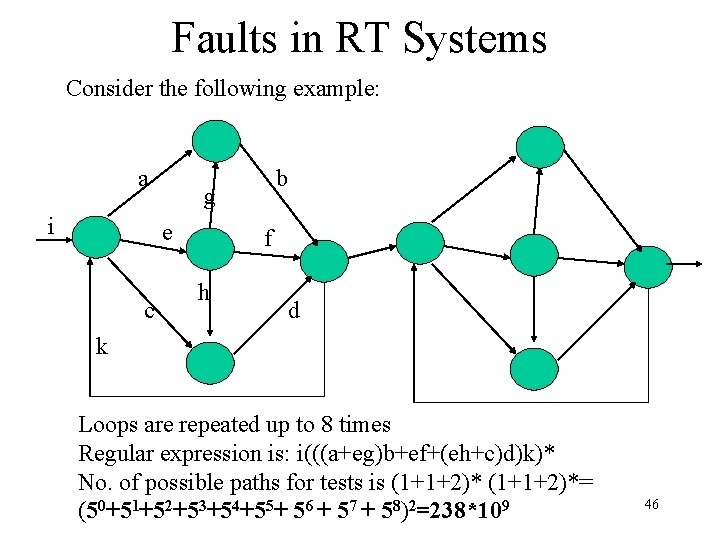

Faults in RT Systems Consider the following example: a i g e c b f h d k Loops are repeated up to 8 times Regular expression is: i(((a+eg)b+ef+(eh+c)d)k)* No. of possible paths for tests is (1+1+2)*= (50+51+52+53+54+55+ 56 + 57 + 58)2=238*109 46

Faults in RT systems • • • Assume: a test takes 1 mili-sec. In a year 365*86400*1000 =315360*106 Total time =250/3. 15*10 years!!! Smarter methods yield shorter times Finding “race” conditions is difficult! And almost impossible to “simulate” • Net Result: Realistic conditions for tests very difficult, errors introduced in early phases pop up in the final system! 47

Faults in RT systems • Faults may be transient (a task failed, but a copy was activated, a hw component fails) interference (result) may be either permanent (data lost, wrong action taken) or transient (not all received packets acknowledged) • Environmental condition may well trigger a problem!(HW causes SW and vice a versa) • How do we detect a problem – Many times wrong action means slow response! 48

Faults in RT systems • Treating Response time problems – Usually deadline set to be response time is no answer it is too late. – Try to have response time sensing shorter than deadline (not a necessary condition as alternative method short!) – What to do: • Have a primary (default) (P) procedure which usually works • In case of problem apply an alternative (A) procedure (usually much shorter) to compensate. 49

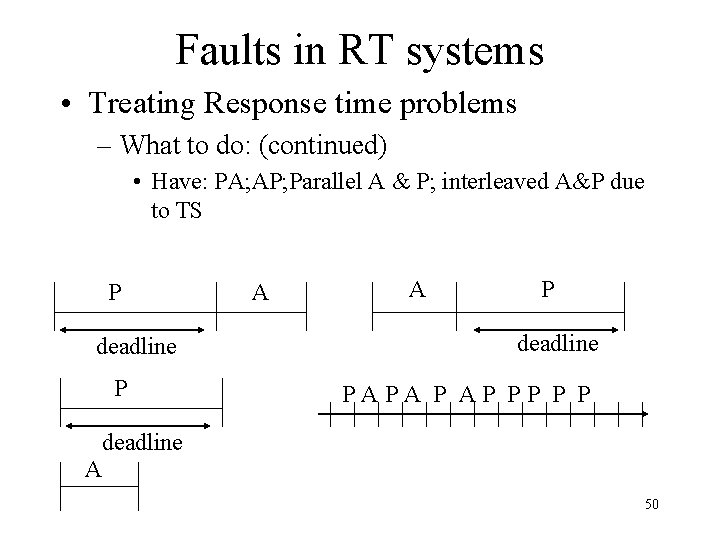

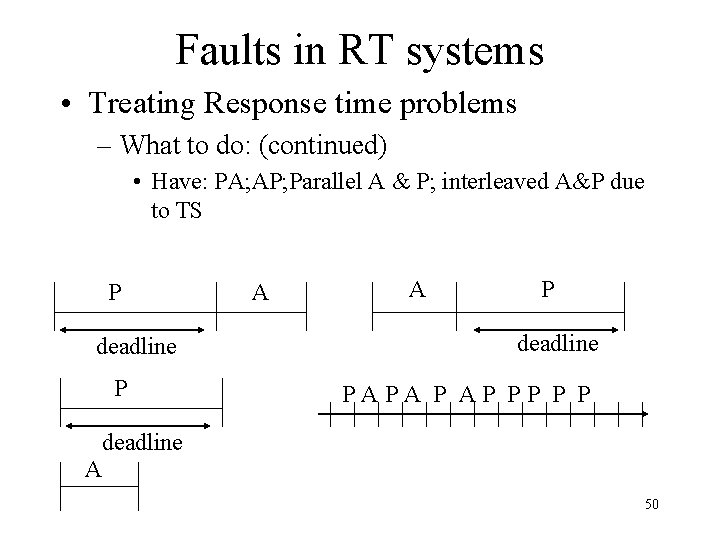

Faults in RT systems • Treating Response time problems – What to do: (continued) • Have: PA; AP; Parallel A & P; interleaved A&P due to TS P deadline P A A P deadline PAPA P AP PP P P deadline A 50

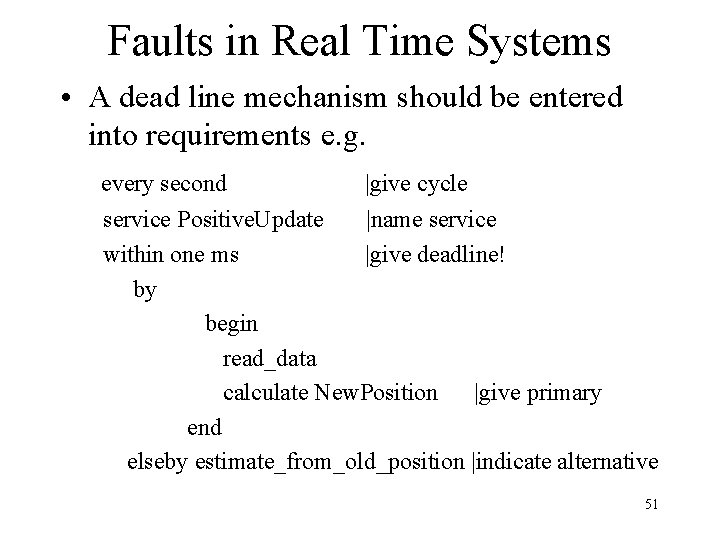

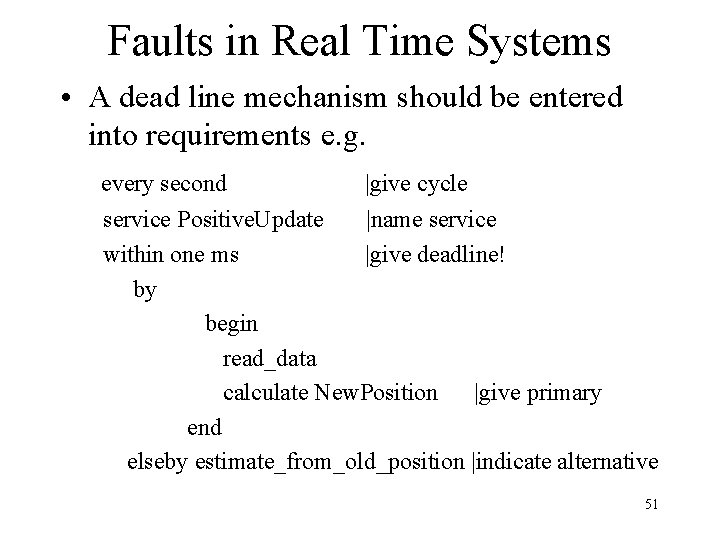

Faults in Real Time Systems • A dead line mechanism should be entered into requirements e. g. every second |give cycle service Positive. Update |name service within one ms |give deadline! by begin read_data calculate New. Position |give primary end elseby estimate_from_old_position |indicate alternative 51

Faults in Real Time Systems • Reliability is measured by the percent of time a system is operational • RT systems should be operational at all times (100%) Impossible!! • Need a built in mechanism so at least a degraded service operational mode is possible! • Reliability is built by: – Recovery from error (all types of errors) – Fault prevention – Fault tolerance 52

Faults in Real Time Systems • HW Fault Prevention – Selection of most reliable components • Cost performance is a factor! – Use proven components (usually special certification HLR!) – Use high integrity techniques for connecting components – Screen out interference – Design for testability! (HW or SW) 53

Faults in Real Time Systems • SW Fault Prevention – Proven rigorous techniques for requirements specifications, and design, use software patterns for design – Use ready made components (ADT, Math libraries, System tools, etc. ) – Design for testability – Use project support environments (compilers, editors, configuration management, quality focus groups etc. ) 54

Faults in Real Time Systems • SW Fault Tolerance – Faults are left behind…. – Design should plan for: • Fail operational provides full fault tolerance for a short time with no significant loss of functionality (data collected, is not transmitted, rather stored on disk!) • Fail soft provides graceful degradation. Some functionality stops (less important) while others continue, allowing later recovery and repair • Fail Safe provides for an orderly system halt which allows fast restart! 55

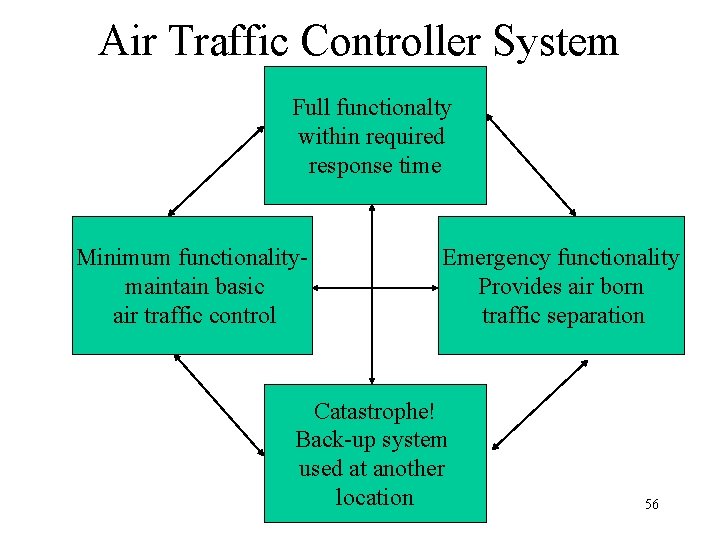

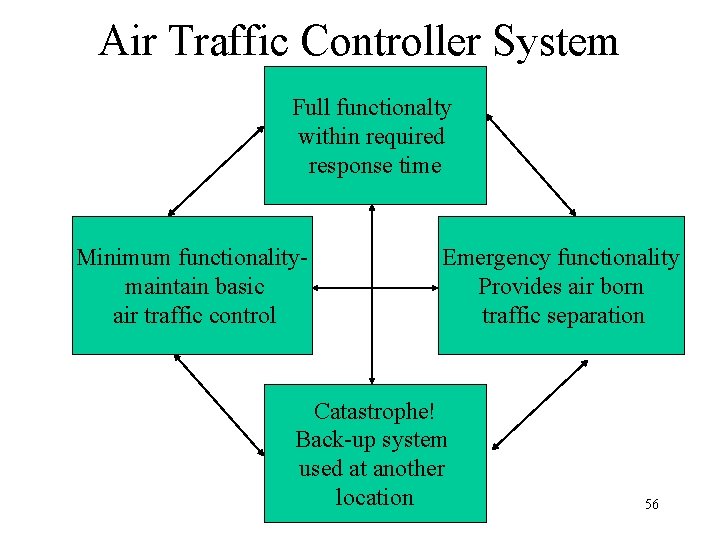

Air Traffic Controller System Full functionalty within required response time Minimum functionalitymaintain basic air traffic control Emergency functionality Provides air born traffic separation Catastrophe! Back-up system used at another location 56

HW component Fault Tolerance • Static Redundancy: components are redundant, used at all times, results compared and voted on (triple redundancy in guidance systems) • Dynamic Redundancy: redundant components are there (may be used for other tasks) on error detection additional tasks put on the redundant component (alternative route used in case of CRC errors on the main route!) 57

HW/SW component Fault Tolerance • HW methods Comparison: – Static method assumes no design error only transient error possible; needs a manager! – Dynamic method assumes something wrong now needs correction! Use an alternative for time being! • Software has Dynamic and Static redundancy too! – Static: always working needs a manager (N-Version) – Dynamic: error correction brought into action when needed (Exception Handlers) 58

SW Static Fault Tolerance • N-version programming: production of N>=2 independent programs with the same functionality • Program execute concurrently • Ideally with the same input the same output is produced! • A managing task should decide what to do • Basis: – specifications are: complete, consistent and unambiguous 59

SW Static Fault Tolerance • Basis (continued): – Different teams, languages, and OS eliminate possible dependency will never fail exactly at the same time or the same reasons!! • If same language to be used, use different compilers (Microsoft, Borland) – Managing process invokes each program, gets results and decides • Decision based on: comparison vectors, comparison status indicators, and comparison points • Output gets out of manager task (as in telecommunications) each task can become the manager! 60

SW Static Fault Tolerance • Comparison Vectors – “VOTES” Data structures representing the results of each version (new commands for guided missile engine, present locations of aircrafts (Air Control system) etc. ) • Comparison Status Indicators – Action that each version should take (stop, calculate next result with present votes attached, continue) • Comparison points – Certain points in each version program at which a version transfers some results and logical data to the manager 61

SW Static Fault Tolerance • Comparison points (continued) – Comparison points introduced to ensure fast, easy and correct comparison • Floating point calculations yield different results for different no. of calculations (depend on # of additions/multiplications etc. precision of result is fast decaying Result out of tolerance different paths in program ) • Logical data to ensure path taken by version results in information that can be compared (integration done, rather then interpolation) • Exact knowledge of algorithms increase range for comparison, 62

SW Fault Tolerance • Use of Fuzzy Logic to change comparison algorithm with different conditions • Too many comparison points Algorithm has to be very similar N-Version purpose defeated • Dynamic SW Redundancy has 4 parts – Detection, Confinement, Recovery, and Fix • Detection: A process by which error is detected. – Environmental Detection • HW detection: illegal instruction execution, Arithmetic Overflow, Protection Violation in some computers 63

SW Fault Tolerance – OS Detection • Null Pointer, No. out of bounds (floating), no more heap, no. more queues – Application Detection • Manager detecting differences (N-Version), Coding Checks (CRC (SW + HW)), Reversal checks (if a=mb+c b=(ac)/m ; get a and recalculate b to ensure; very complex!) Statistical checks (based on averages and sigma detect wrong data) Logical detection (age<0 || age>120) • Confinement: A design which will stop error from spreading. Modular Design (problem be confined to a single task) Dynamic read write permissions for shared data. 64

SW Fault Tolerance • Recovery: a method by which recovery from error is achieved – Forward Error Recovery –fixes problem and continues from error occurrence point (Hamming codes in communications, usually needs full knowledge of hazards very difficult (Missile Launch cannot be aborted after start, usually needs stop system!!) – Backward Error Recovery – after fix restarts at the beginning of the erroneous sequence (assumes error occurrence is accidental) needs no knowledge of reason, needs last state data and flags) – Used when unanticipated errors do not leave a permanent damage (Not good for Missile Launch!) 65

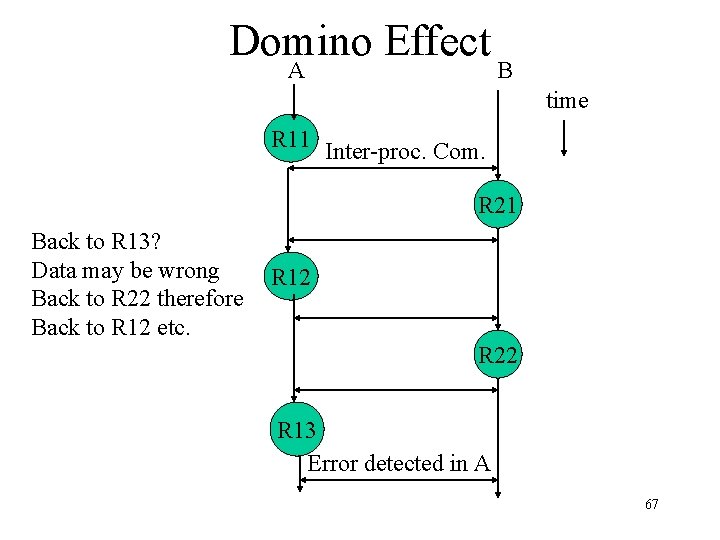

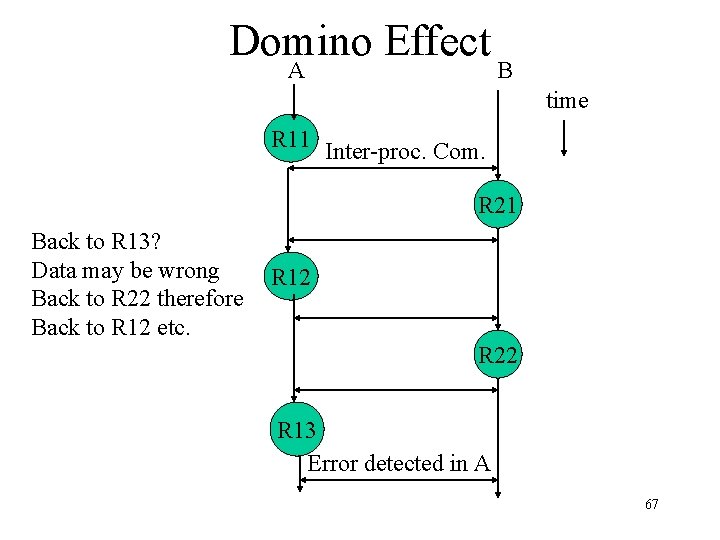

SW Fault Tolerance – Backward Error Recovery complicated by concurrent tasks! – Usually restarting one needs backing of the other – How far back depends on details of inter-tasks communication locations – Example: • assume 2 concurrent tasks with starting points Rij. • Inter-task communication in between Rij. • Backing one task will result in domino effect! 66

Domino Effect A B time R 11 Inter-proc. Com. R 21 Back to R 13? Data may be wrong Back to R 22 therefore Back to R 12 etc. R 12 R 22 R 13 Error detected in A 67

Dynamic Error Recovery • Recovering from a single error leaves reasons for errors in place • Continuous service requires elimination of root causes • HW components can be deactivated, and only redundancy temporarily reduced (Telco Switches, Rerouting in telecom) • Software can be changed, that is a fresh copy loaded (however, error cause is still there) • Continued service needs special algorithms for hot swap 68

Dynamic Error Recovery • Eliminating error root cause is system dependent, requires deep knowledge of the system, takes lots of time, expensive etc. • Most systems have very little of this • Usually all systems have exception handlers • C++, JAVA have them as part of the system – Try; Throw; Catch – Try is test; Throw invokes the system in order to: Catch and deal with the error 69