Real time computing neural systems and future challenges

- Slides: 50

Real time computing, neural systems and future challenges in HEP: an introduction to the RETINA initiative. Giovanni Punzi Universita' di Pisa and INFN XII seminar on software for Nuclear, Subnuclear and Applied Physics Alghero, Italy 24 -29 May 2015

Introduction This seminar is centered on a specific initiative, but it requires a lot of introduction, and will also take me into the domain of computing within living organism (“real” neural networks) It deals with real-time computing rather than off-line processing, although the boundary between the two is now less clear than ever. By real-time I mean processing that happens before substantial buffering has occurred, and there is still time to change what is done next. This involves not only data processing (reconstruction), but also Trigger and DAQ – Trigger = any system/methodology to select data to be preserved indefinitely – DAQ = any system/methodology to move data from sensors to permanent storage, or other needed destinations.

Introduction Trigger and DAQ have been part of HEP since its earliest days With time, they have become increasingly complex and computationally intensive Advancements in electronics technology caused huge price/performance drops - but requirements of HEP experiments kept increasing (data flow, complexity, rate. . . ) → Real-time processing is still today a major cost item of experiments → In many cases a major technical constraints

Current HEP trends In most modern systems, on-line is multi-layered and event-oriented Data flow progressively reduced by rejecting a fraction of the events. At each stage, computational cost, data input, and latency increase Innovation in the LHC era: Reduction in the number of stages (3 -4 in pre-LHC era) Larger use of commercial CPUs using high-level languages Complexity of CPU-based processing increased Complexity of first processing stage stayed constant Increasing rate of permanent stored data → growing storage

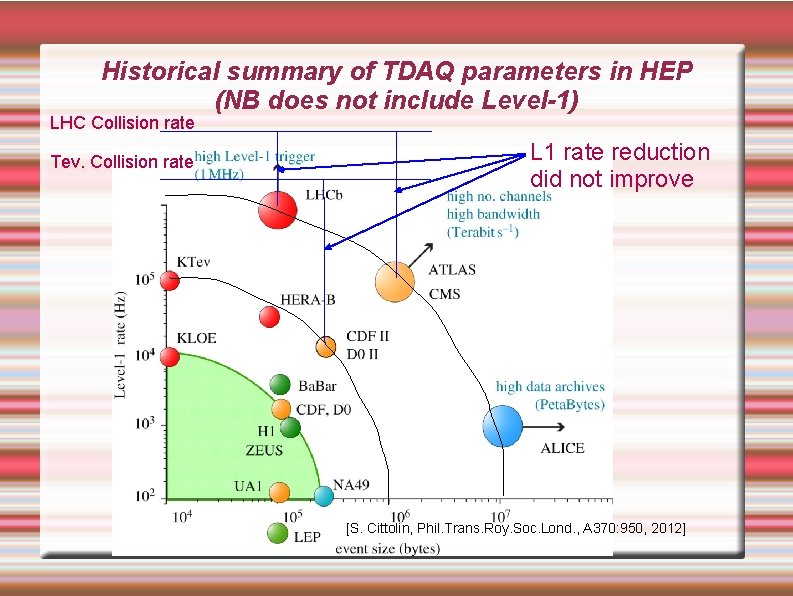

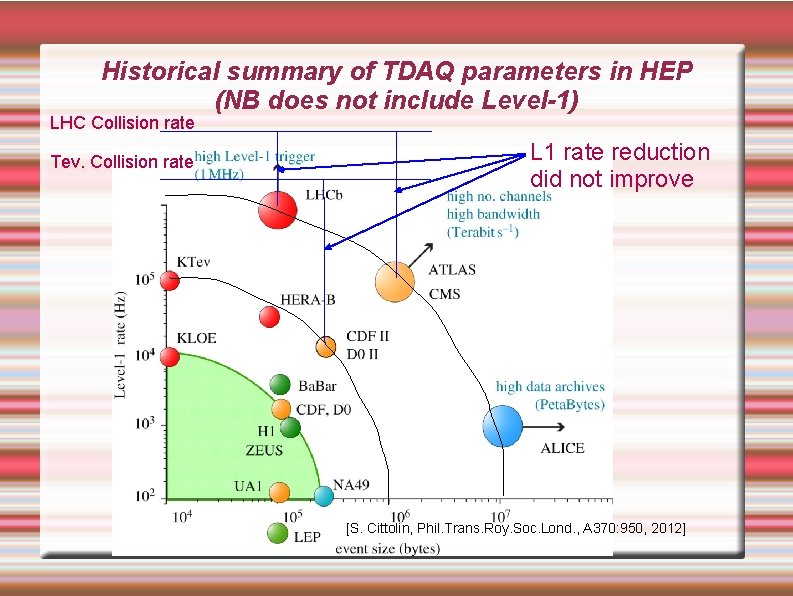

Historical summary of TDAQ parameters in HEP (NB does not include Level-1) LHC Collision rate Tev. Collision rate L 1 rate reduction did not improve [S. Cittolin, Phil. Trans. Roy. Soc. Lond. , A 370: 950, 2012]

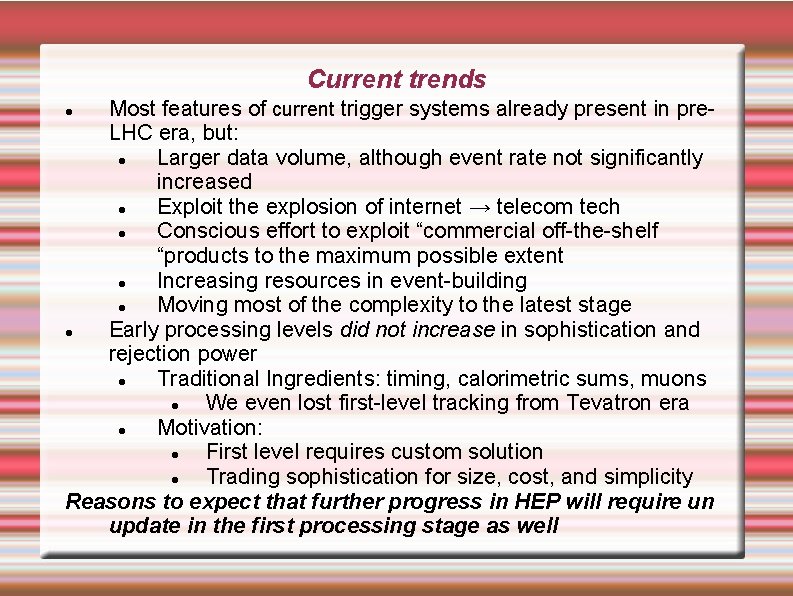

Current trends Most features of current trigger systems already present in pre. LHC era, but: Larger data volume, although event rate not significantly increased Exploit the explosion of internet → telecom tech Conscious effort to exploit “commercial off-the-shelf “products to the maximum possible extent Increasing resources in event-building Moving most of the complexity to the latest stage Early processing levels did not increase in sophistication and rejection power Traditional Ingredients: timing, calorimetric sums, muons We even lost first-level tracking from Tevatron era Motivation: First level requires custom solution Trading sophistication for size, cost, and simplicity Reasons to expect that further progress in HEP will require un update in the first processing stage as well

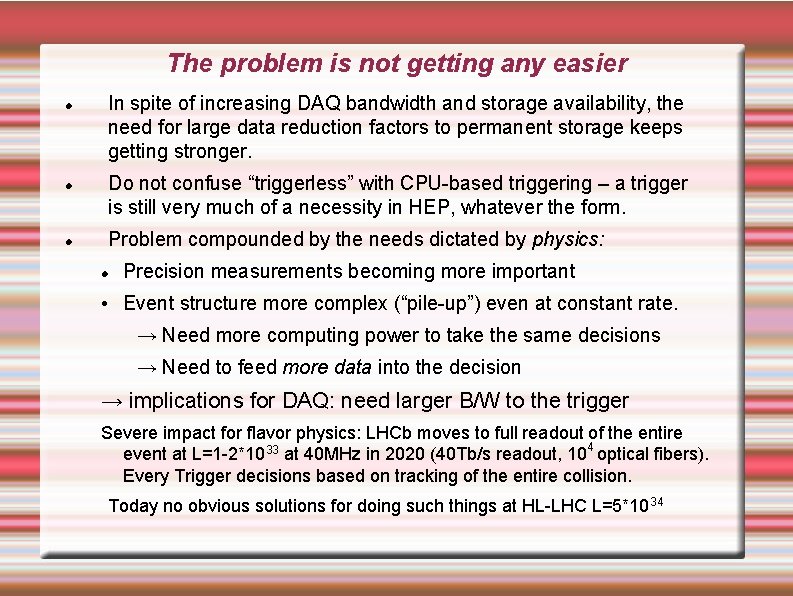

The problem is not getting any easier In spite of increasing DAQ bandwidth and storage availability, the need for large data reduction factors to permanent storage keeps getting stronger. Do not confuse “triggerless” with CPU-based triggering – a trigger is still very much of a necessity in HEP, whatever the form. Problem compounded by the needs dictated by physics: Precision measurements becoming more important • Event structure more complex (“pile-up”) even at constant rate. → Need more computing power to take the same decisions → Need to feed more data into the decision → implications for DAQ: need larger B/W to the trigger Severe impact for flavor physics: LHCb moves to full readout of the entire event at L=1 -2*1033 at 40 MHz in 2020 (40 Tb/s readout, 104 optical fibers). Every Trigger decisions based on tracking of the entire collision. Today no obvious solutions for doing such things at HL-LHC L=5*1034

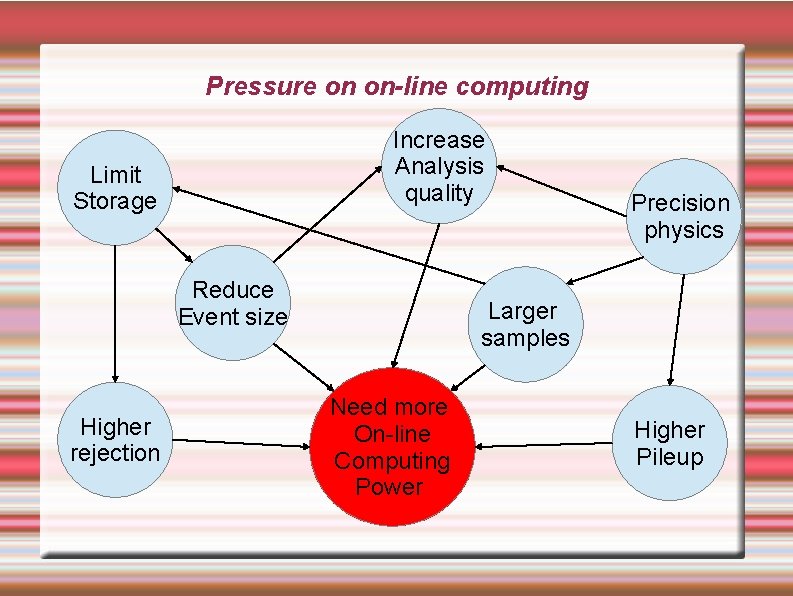

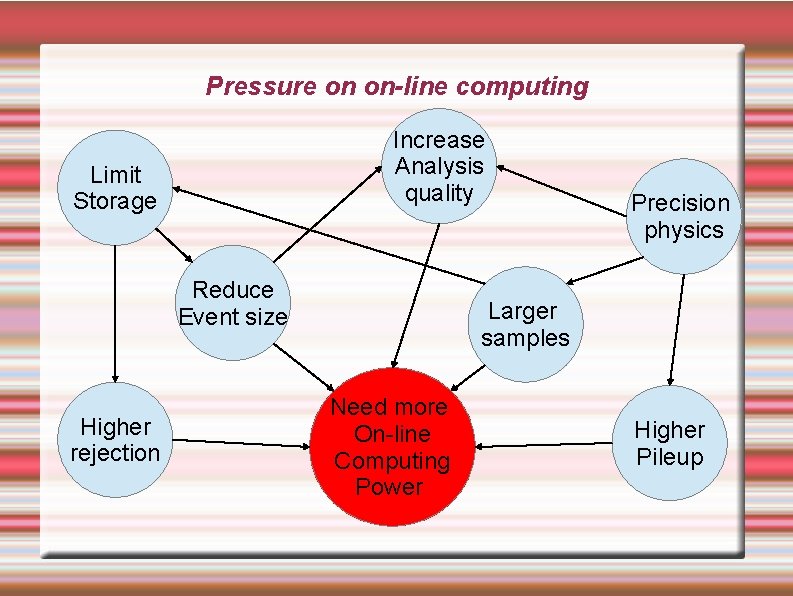

Pressure on on-line computing Increase Analysis quality Limit Storage Reduce Event size Higher rejection Precision physics Larger samples Need more On-line Computing Power Higher Pileup

The issue with the first level of processing It is “true real-time”: latency and local data availability requirements usually carry a weight Greater specificity, tighter optimization Less amenable to “plug-and-play” commercial solutions. • Requires larger development time, specialists • Less commonality with other solutions • In the old times is was implemented in “hardware” • Now the very distinction between hardware and software is much more blurred. . . electronics boards are typically completely programmable in software, although the software may be less well known • More than anything else, “architecture” counts. Design is not made of procedures, but of structures – this is happing to traditional software as well, where increasing parallelization requires the programmer to think in terms of actual execution.

Current R&D in tracking triggers Tight latency requirements at LHC (few µs at L 1) ATLAS introducing a tracking trigger already in 2015 Based on Associative Memories (FTK) Post-L 1: 100 k. Hz input, 40µs latency. Both CMS and ATLAS looking at L 1 tracking for 2025 (phase 2) • Not yet demonstrated to be possible for full detector • Current use-cases revolve around (di)muons • May represent a major challenge for operation at HL-LHC

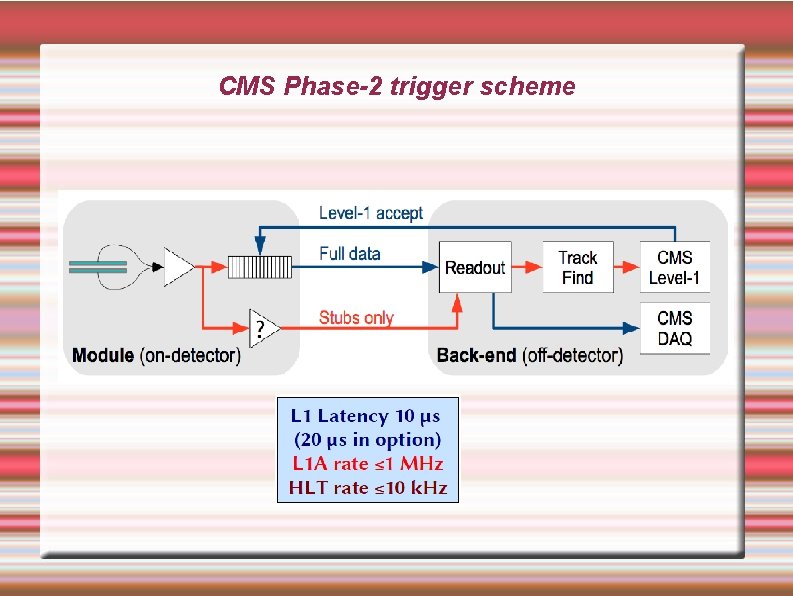

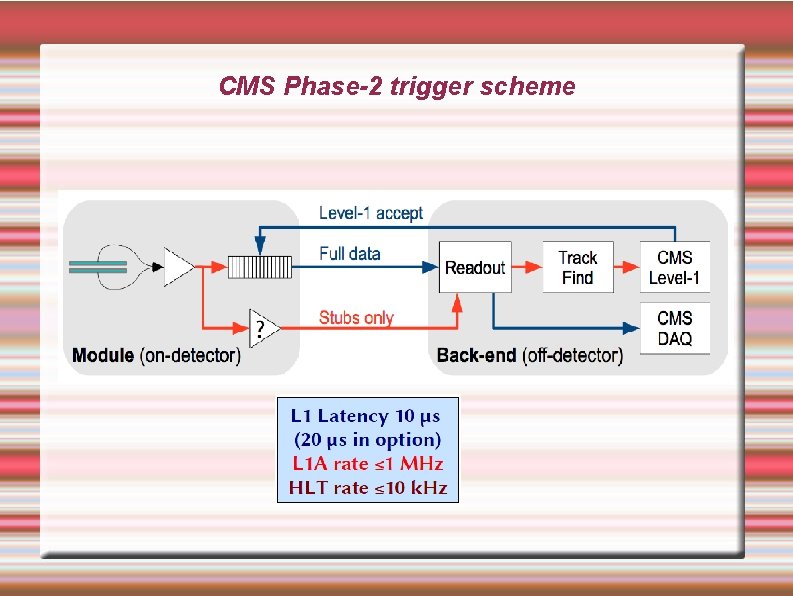

CMS Phase-2 trigger scheme

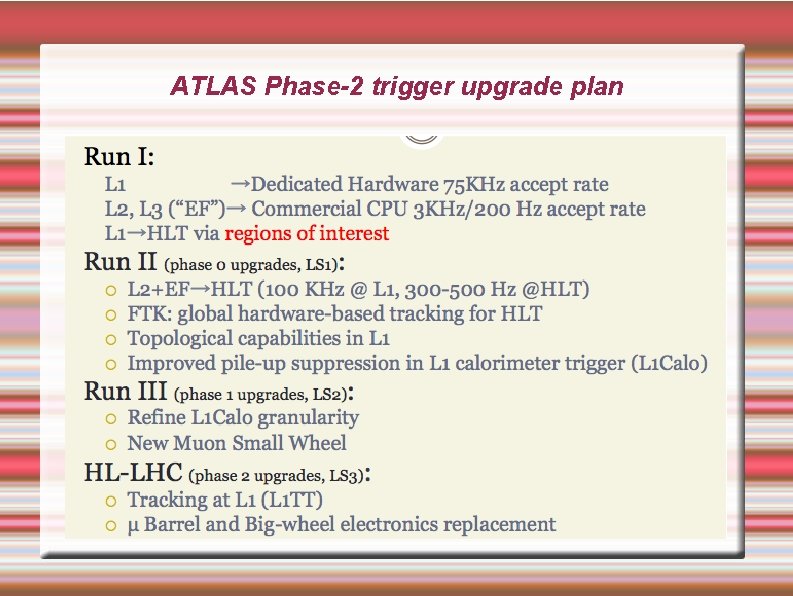

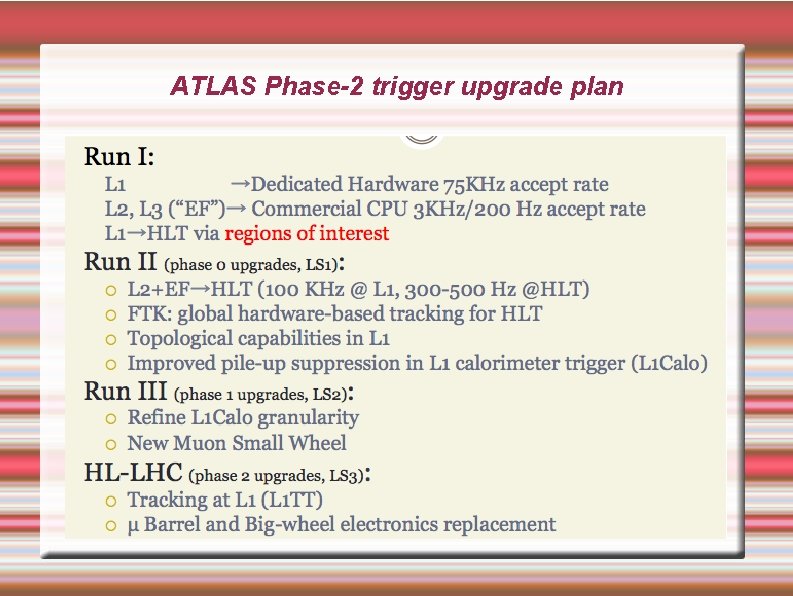

ATLAS Phase-2 trigger upgrade plan

Personal view of future evolution of HEP computing Experiments will be limited by computing Large “commodity” computing will be used Physics reconstruction will happen mostly on-line Only a small fraction of events, and of data within an event, will be saved Calibration will be completely done on-line First-level processing will evolve into “detector-embedded” reconstruction of complex primitives - that will make the rest of computation manageable. Some of this is already happening in 2015: LHCb real-time calibration in 2015 run – LHCb “turbo stream”: drop raw data and only save high-level info (for some event streams) The less obvious, and more controversial, point is about first-level processing – this is what I am going to discuss in the rest of this talk.

“Natural” computing While trying to guess how computing system will evolve, let me take a digression and mention that on this planet, the history of computing dates much back than what we usually think. Computing has been a crucial component of life since the last billion years. We have been concerned with mechanics, thermodinamics, chemistry. . . but only recently we have been starting to understand the “computing” aspect of life. Some aspects of “living” computing are not so far from the manmade computing as you might think. One example is natural vision, that is, the processing of visual images in the brain of living organisms

Two computing problems, compared VISION HEP Lots of complex data (possibly unanticipated) Little time available Pressure to make accurate decisions Strongly constrained computing resources

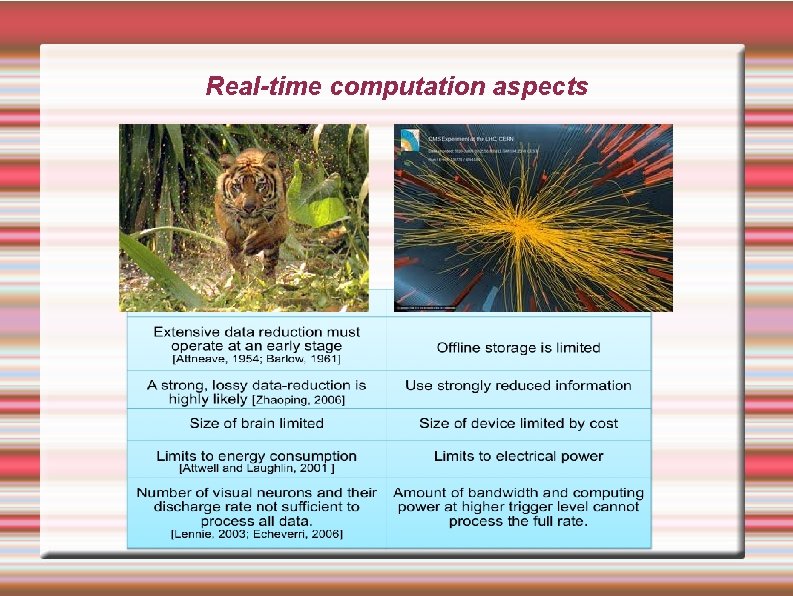

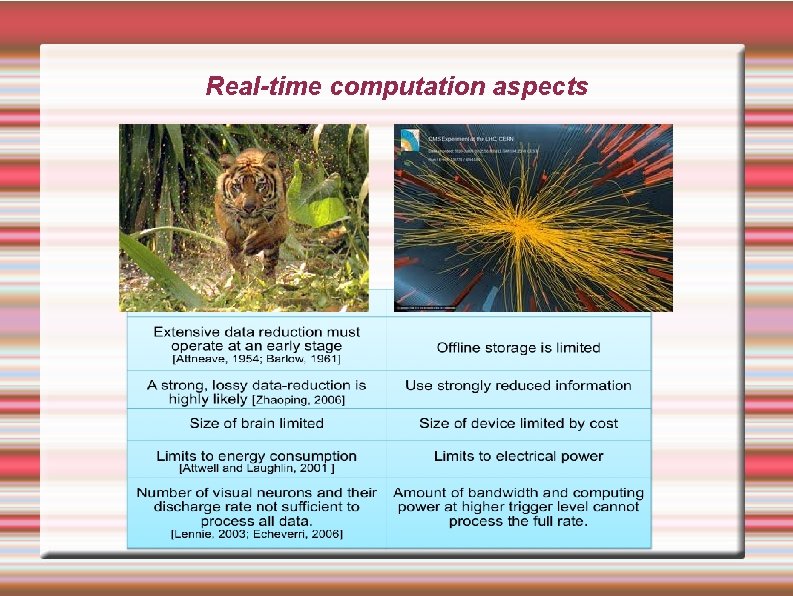

Real-time computation aspects

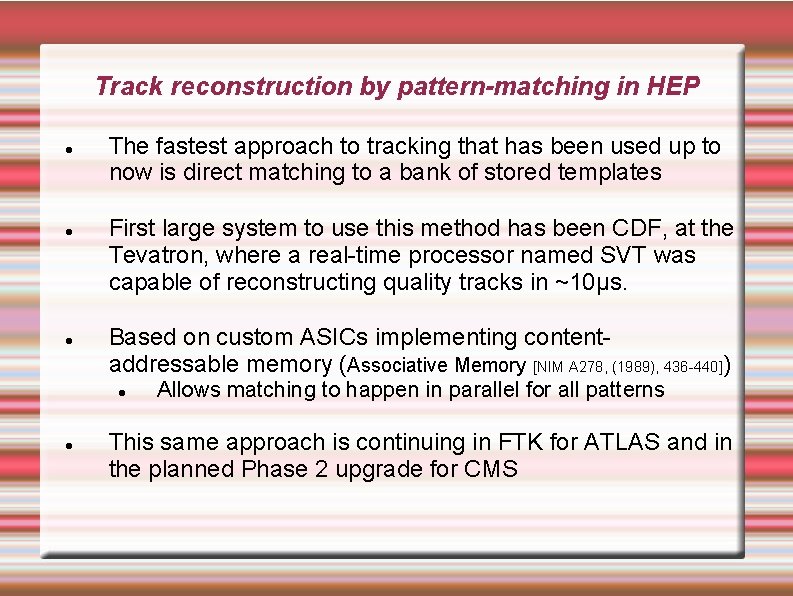

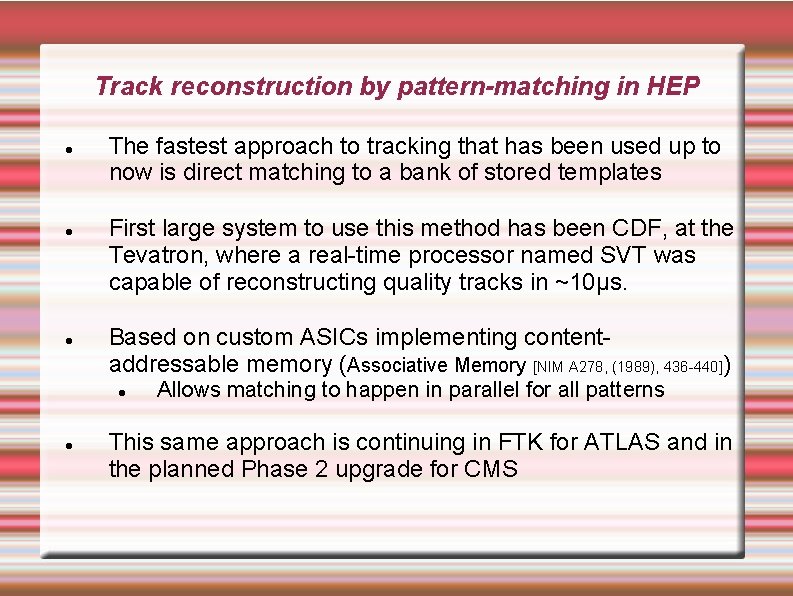

Track reconstruction by pattern-matching in HEP The fastest approach to tracking that has been used up to now is direct matching to a bank of stored templates First large system to use this method has been CDF, at the Tevatron, where a real-time processor named SVT was capable of reconstructing quality tracks in ~10µs. Based on custom ASICs implementing contentaddressable memory (Associative Memory [NIM A 278, (1989), 436 -440]) Allows matching to happen in parallel for all patterns This same approach is continuing in FTK for ATLAS and in the planned Phase 2 upgrade for CMS

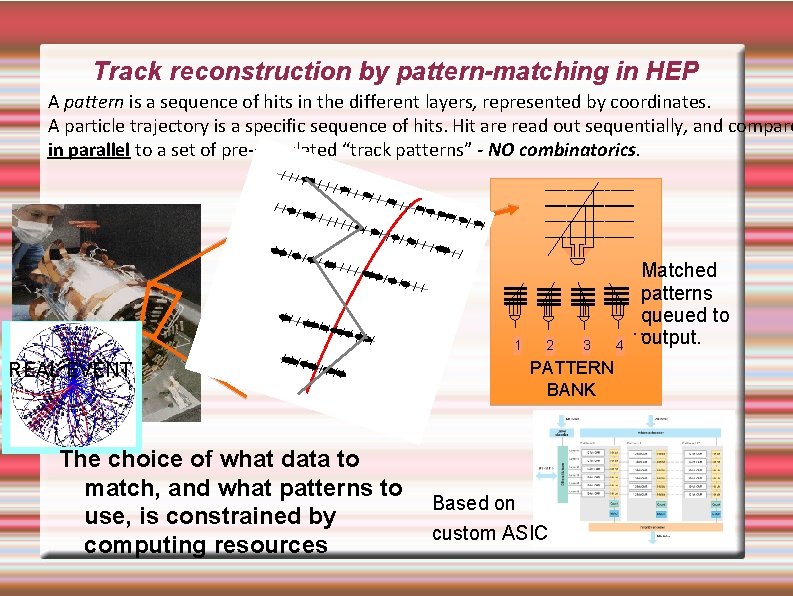

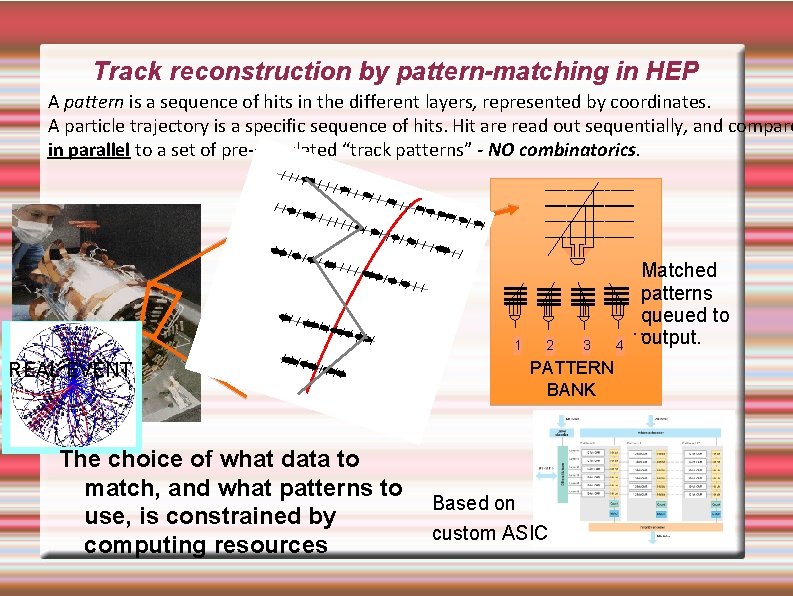

Track reconstruction by pattern-matching in HEP A pattern is a sequence of hits in the different layers, represented by coordinates. A particle trajectory is a specific sequence of hits. Hit are read out sequentially, and compare in parallel to a set of pre-calculated “track patterns” - NO combinatorics. 1 3 PATTERN BANK REAL EVENT The choice of what data to match, and what patterns to use, is constrained by computing resources 2 Based on custom ASIC 4 Matched patterns queued to … output.

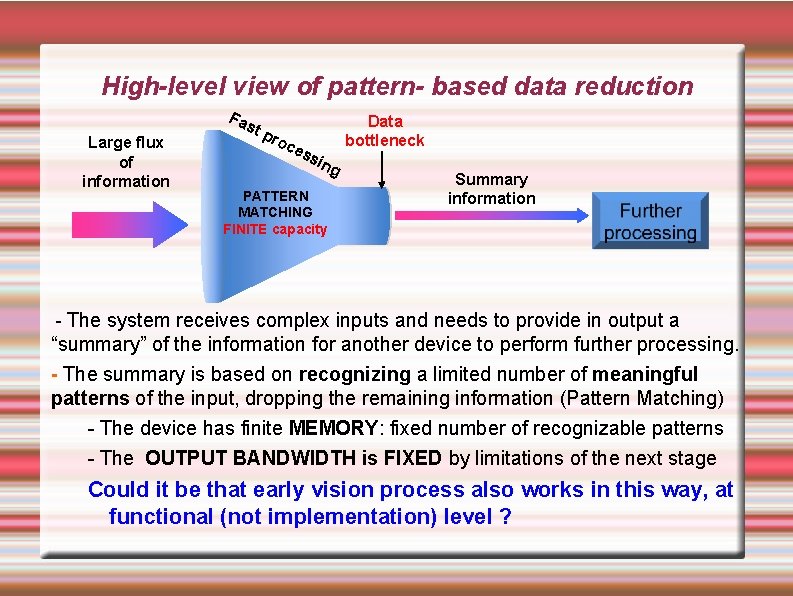

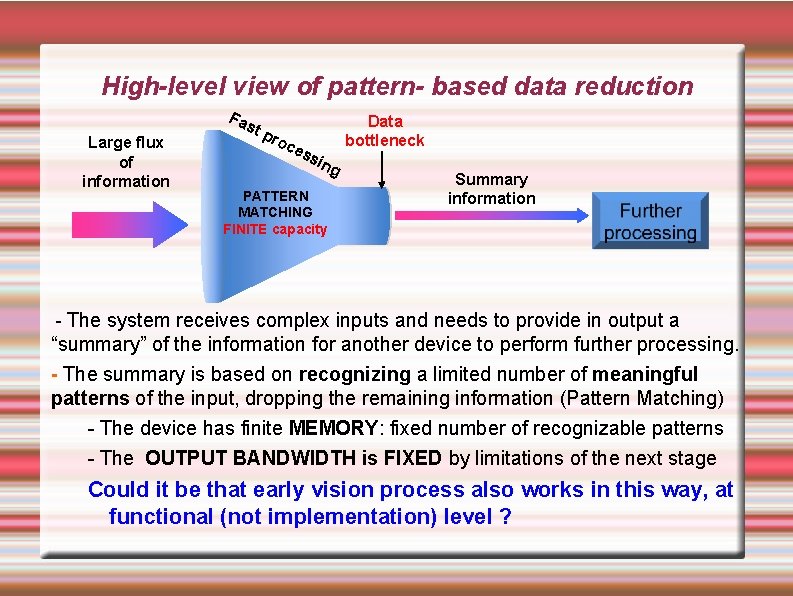

High-level view of pattern- based data reduction Fa Large flux of information st Data bottleneck pro ce ss ing PATTERN MATCHING FINITE capacity Summary information - The system receives complex inputs and needs to provide in output a “summary” of the information for another device to perform further processing. - The summary is based on recognizing a limited number of meaningful patterns of the input, dropping the remaining information (Pattern Matching) - The device has finite MEMORY: fixed number of recognizable patterns - The OUTPUT BANDWIDTH is FIXED by limitations of the next stage Could it be that early vision process also works in this way, at functional (not implementation) level ?

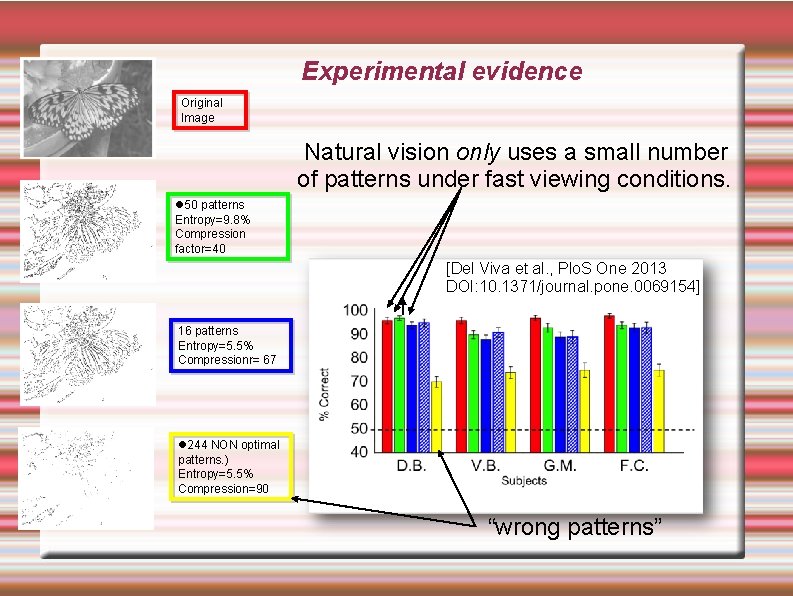

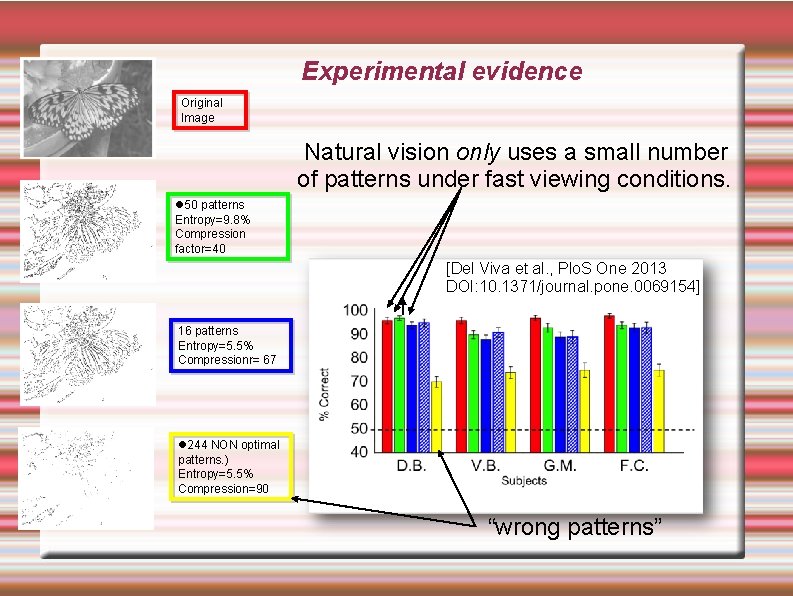

Experimental evidence Original Image Natural vision only uses a small number of patterns under fast viewing conditions. 50 patterns Entropy=9. 8% Compression factor=40 [Del Viva et al. , Plo. S One 2013 DOI: 10. 1371/journal. pone. 0069154] 16 patterns Entropy=5. 5% Compressionr= 67 244 NON optimal patterns. ) Entropy=5. 5% Compression=90 “wrong patterns”

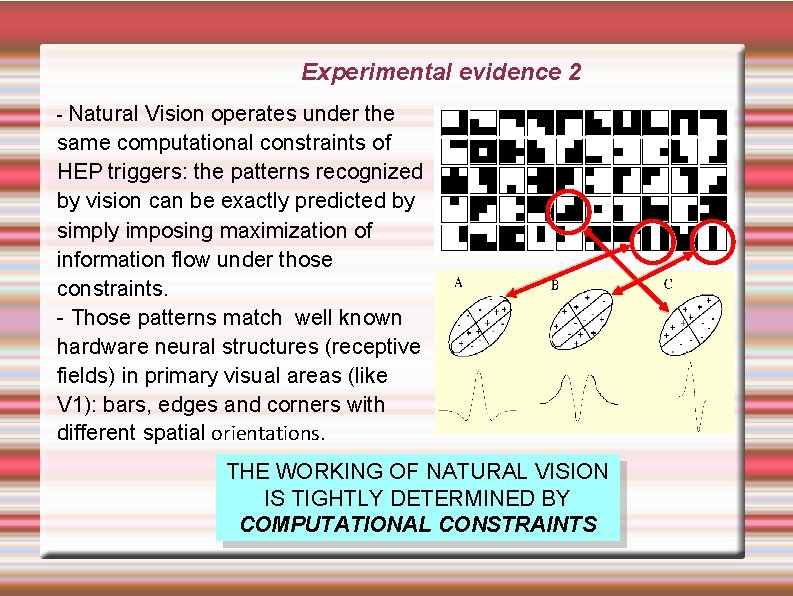

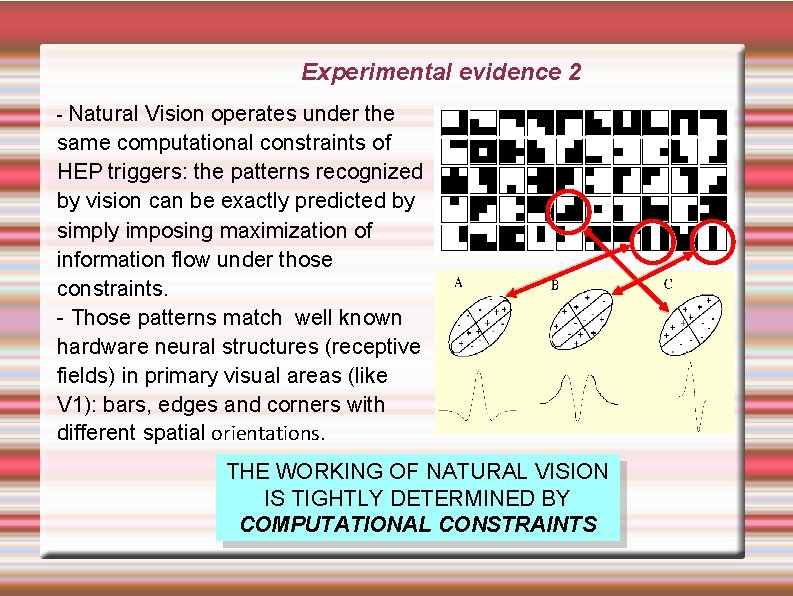

Experimental evidence 2 - Natural Vision operates under the same computational constraints of HEP triggers: the patterns recognized by vision can be exactly predicted by simply imposing maximization of information flow under those constraints. - Those patterns match well known hardware neural structures (receptive fields) in primary visual areas (like V 1): bars, edges and corners with different spatial orientations. THE WORKING OF NATURAL VISION IS TIGHTLY DETERMINED BY COMPUTATIONAL CONSTRAINTS

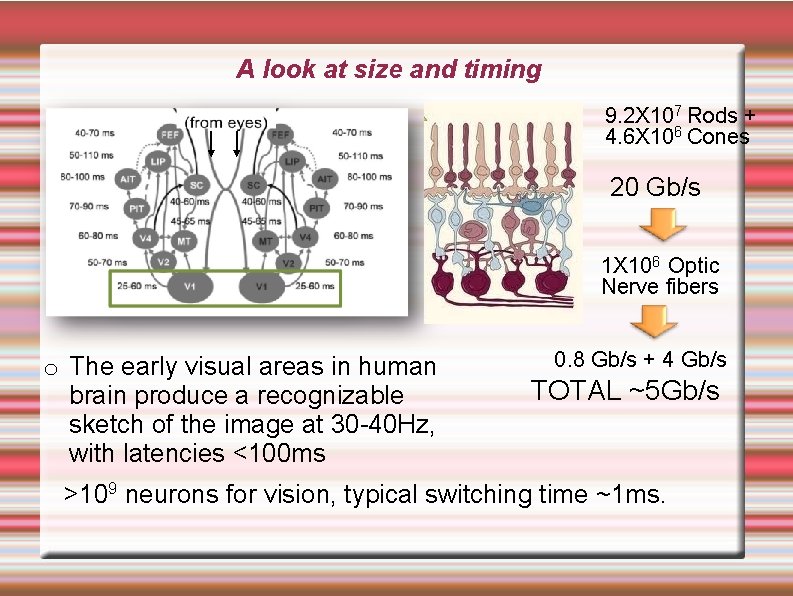

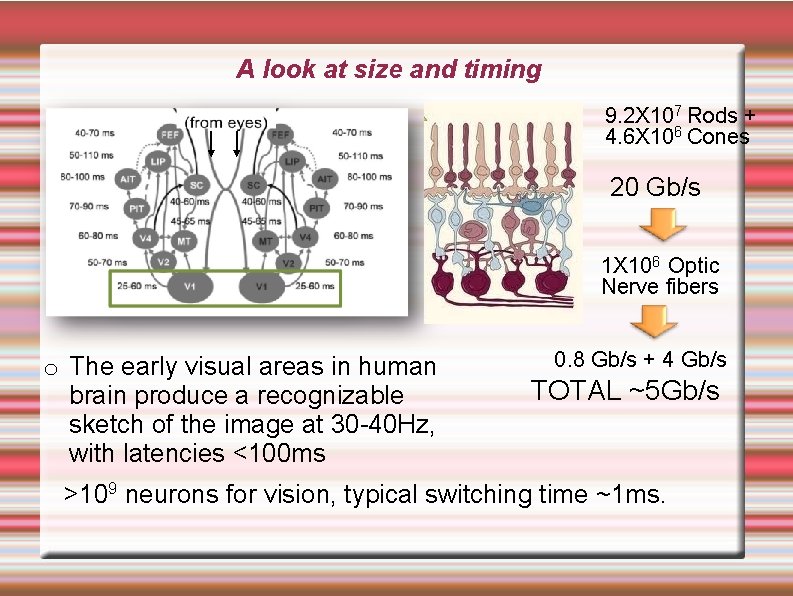

A look at size and timing 9. 2 X 107 Rods + 4. 6 X 106 Cones 20 Gb/s 1 X 106 Optic Nerve fibers Adapted from H. Kirchner, S. J. Thorpe / Vision Research 46 (2006) 1762– 1776 o The early visual areas in human brain produce a recognizable sketch of the image at 30 -40 Hz, with latencies <100 ms 0. 8 Gb/s + 4 Gb/s TOTAL ~5 Gb/s >109 neurons for vision, typical switching time ~1 ms.

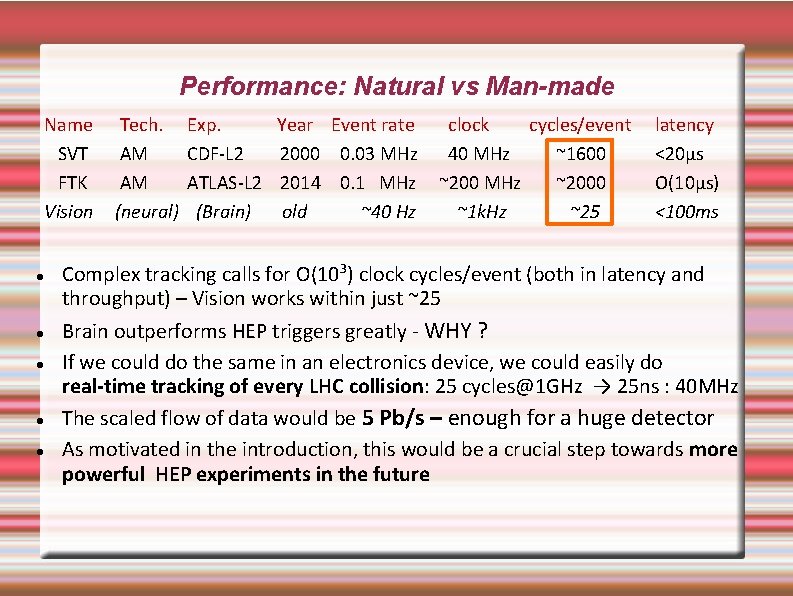

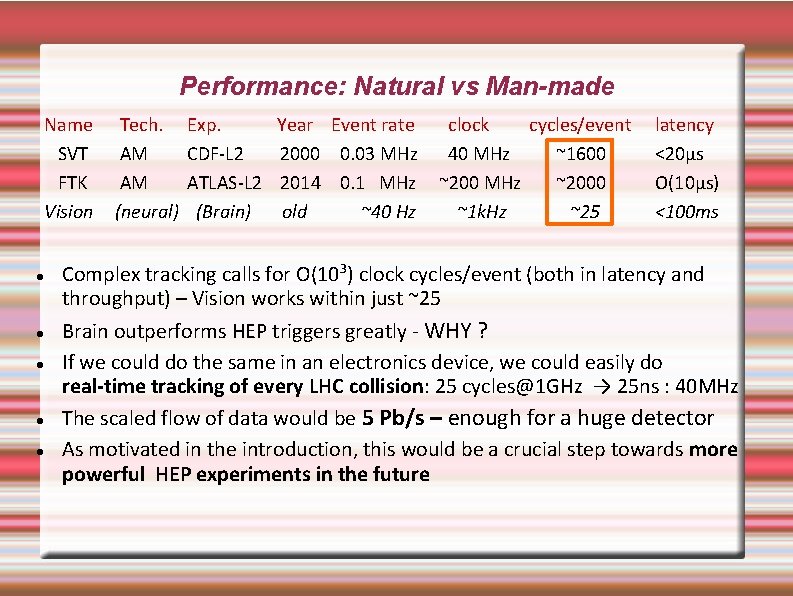

Performance: Natural vs Man-made Name SVT FTK Vision Tech. AM AM (neural) Exp. CDF-L 2 ATLAS-L 2 (Brain) Year Event rate 2000 0. 03 MHz 2014 0. 1 MHz old ~40 Hz clock cycles/event 40 MHz ~1600 ~200 MHz ~2000 ~1 k. Hz ~25 latency <20µs O(10µs) <100 ms Complex tracking calls for O(103) clock cycles/event (both in latency and throughput) – Vision works within just ~25 Brain outperforms HEP triggers greatly - WHY ? If we could do the same in an electronics device, we could easily do real-time tracking of every LHC collision: 25 cycles@1 GHz → 25 ns : 40 MHz The scaled flow of data would be 5 Pb/s – enough for a huge detector As motivated in the introduction, this would be a crucial step towards more powerful HEP experiments in the future

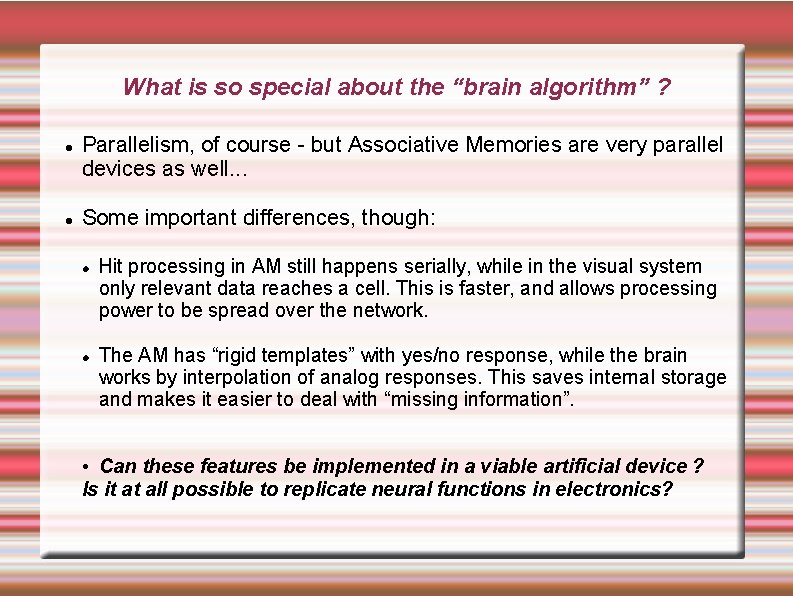

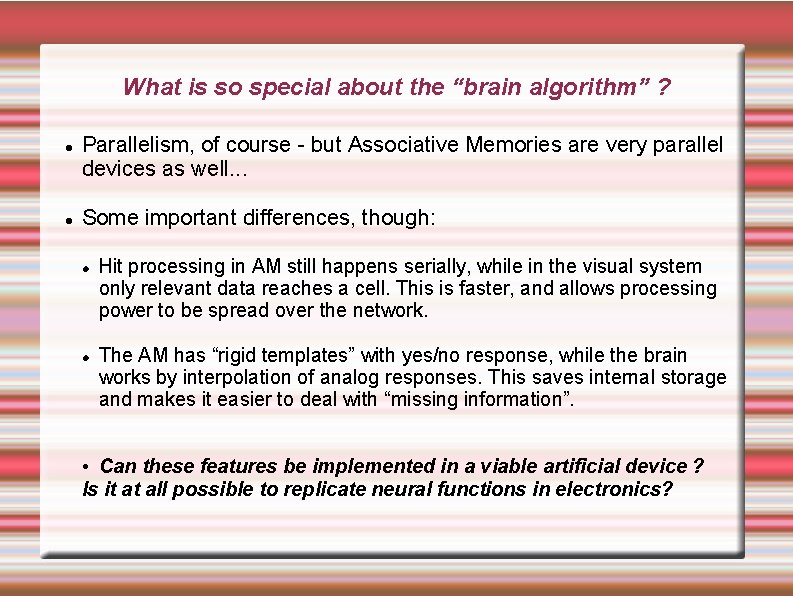

What is so special about the “brain algorithm” ? Parallelism, of course - but Associative Memories are very parallel devices as well. . . Some important differences, though: Hit processing in AM still happens serially, while in the visual system only relevant data reaches a cell. This is faster, and allows processing power to be spread over the network. The AM has “rigid templates” with yes/no response, while the brain works by interpolation of analog responses. This saves internal storage and makes it easier to deal with “missing information”. • Can these features be implemented in a viable artificial device ? Is it at all possible to replicate neural functions in electronics?

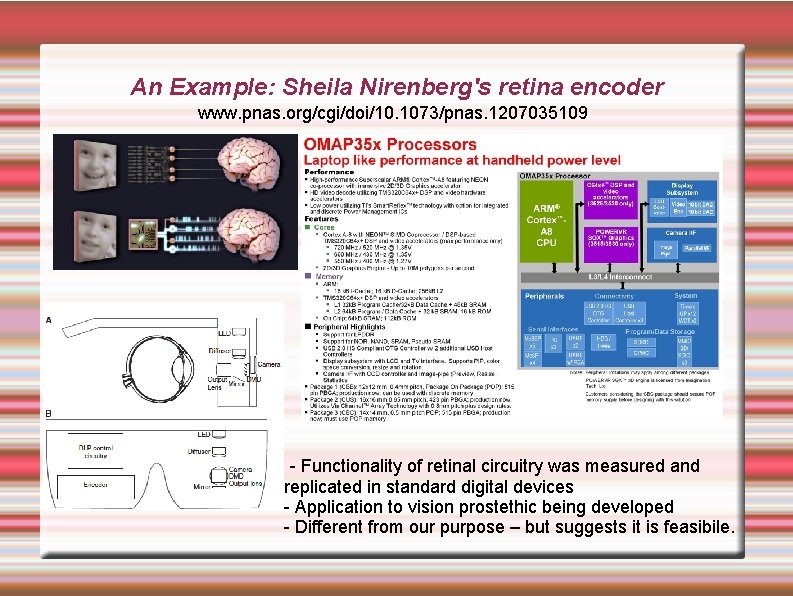

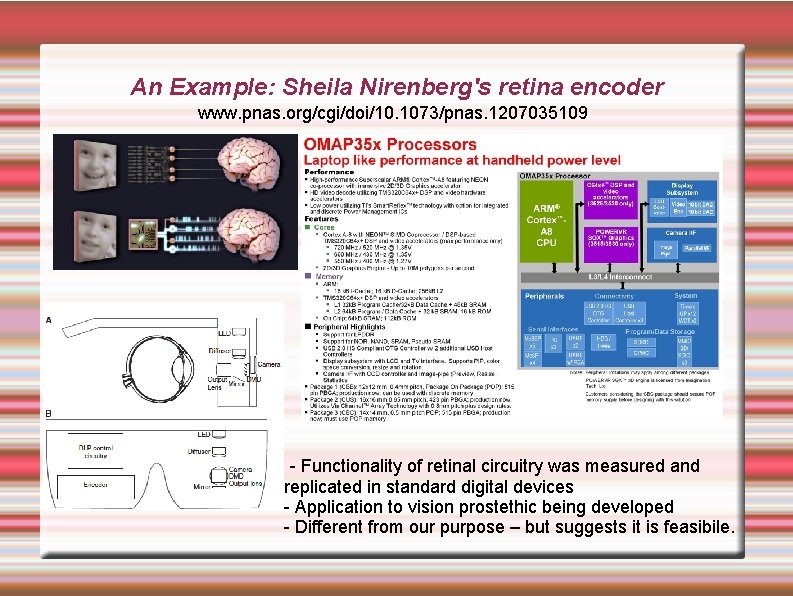

An Example: Sheila Nirenberg's retina encoder www. pnas. org/cgi/doi/10. 1073/pnas. 1207035109 - Functionality of retinal circuitry was measured and replicated in standard digital devices - Application to vision prostethic being developed - Different from our purpose – but suggests it is feasibile.

Introducing the RETINA project (REal time Tracking by Innovative Approach) Politecnico & INFN - Milano - University & INFN-Pisa – Scuola Normale Superiore – CERN https: //web 2. infn. it/RETINA - R&D program supported by INFN CSN 5 - Goal: study the possibility to build a specialized track processor ('TPU') based on a vision-like architecture and evaluate its performance for tracking in LHC environment - “A TPU is to tracking what GPU is to graphics” (just with a smaller market. . . ) - Not intended to replicate vision in detail - just exploit the same design principles.

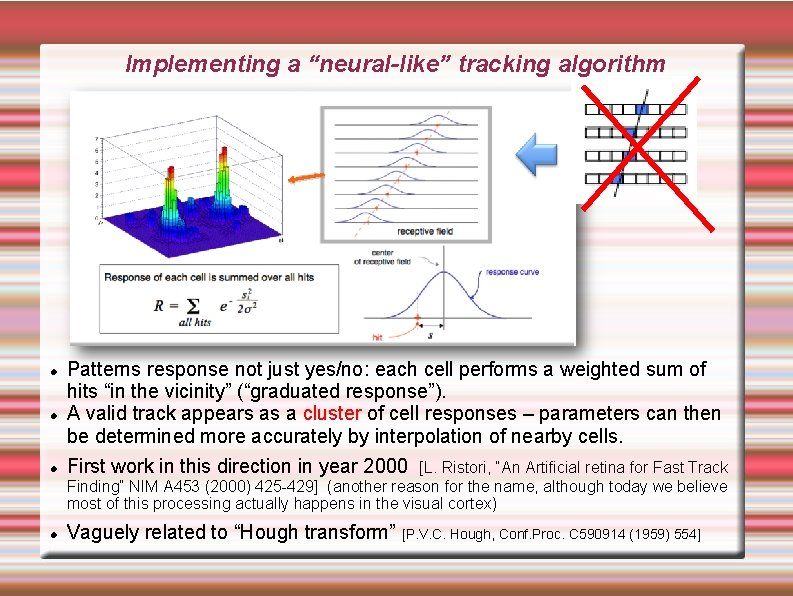

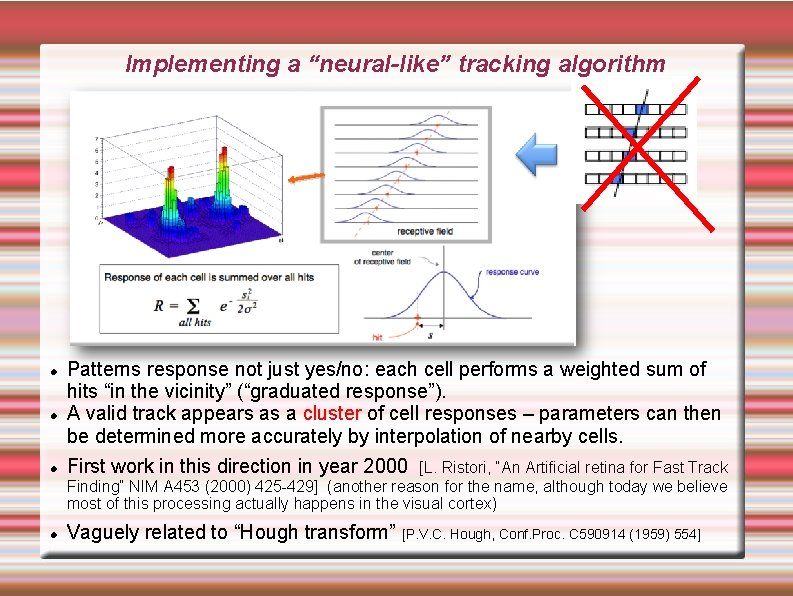

Implementing a “neural-like” tracking algorithm Patterns response not just yes/no: each cell performs a weighted sum of hits “in the vicinity” (“graduated response”). A valid track appears as a cluster of cell responses – parameters can then be determined more accurately by interpolation of nearby cells. First work in this direction in year 2000 Vaguely related to “Hough transform” [P. V. C. Hough, Conf. Proc. C 590914 (1959) 554] [L. Ristori, “An Artificial retina for Fast Track Finding” NIM A 453 (2000) 425 -429] (another reason for the name, although today we believe most of this processing actually happens in the visual cortex)

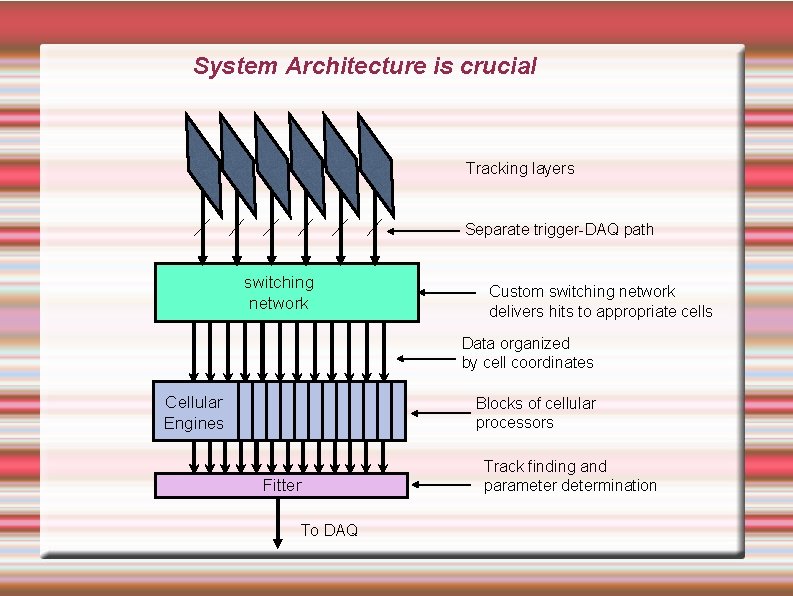

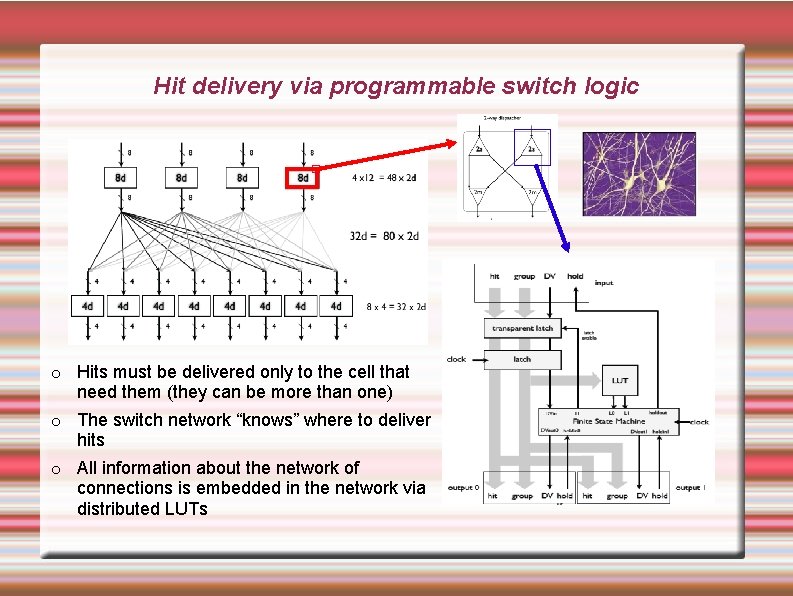

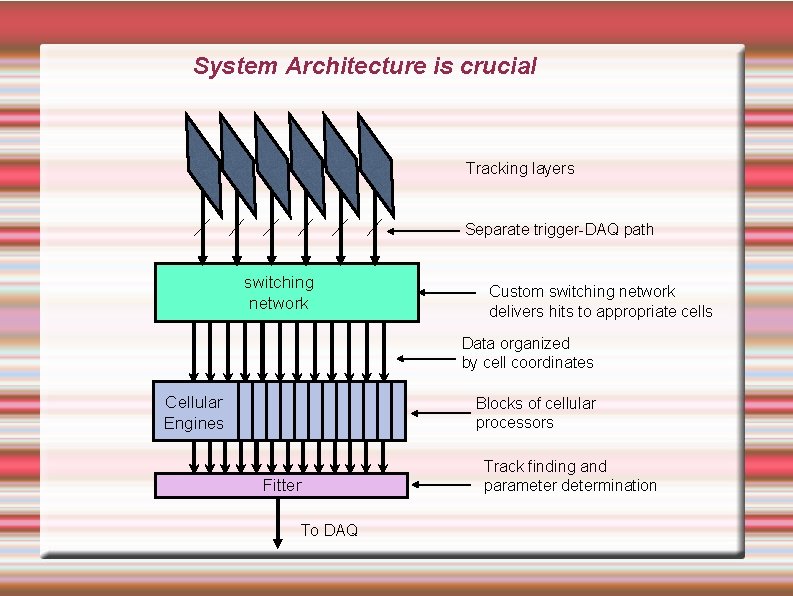

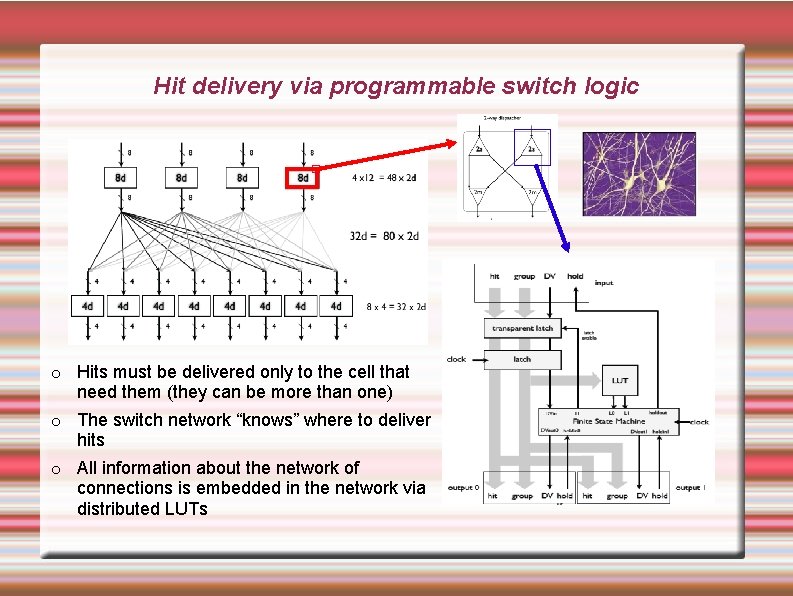

System Architecture is crucial Tracking layers Separate trigger-DAQ path switching network Custom switching network delivers hits to appropriate cells Data organized by cell coordinates Cellular Engines Blocks of cellular processors Fitter To DAQ Track finding and parameter determination

Hit delivery via programmable switch logic o Hits must be delivered only to the cell that need them (they can be more than one) o The switch network “knows” where to deliver hits o All information about the network of connections is embedded in the network via distributed LUTs

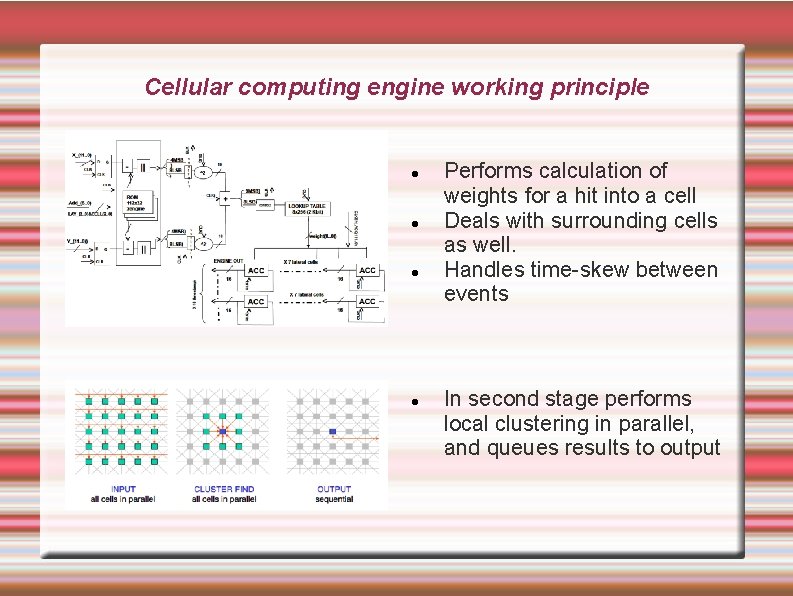

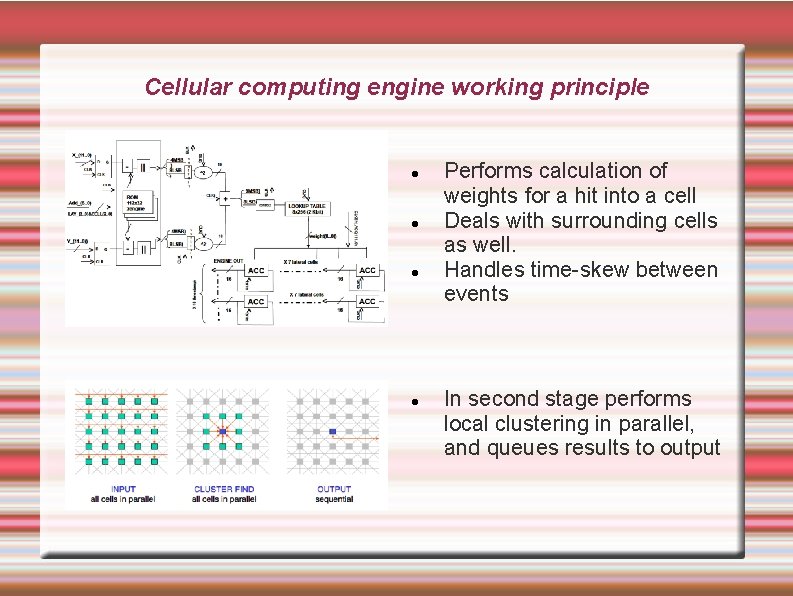

Cellular computing engine working principle Performs calculation of weights for a hit into a cell Deals with surrounding cells as well. Handles time-skew between events In second stage performs local clustering in parallel, and queues results to output

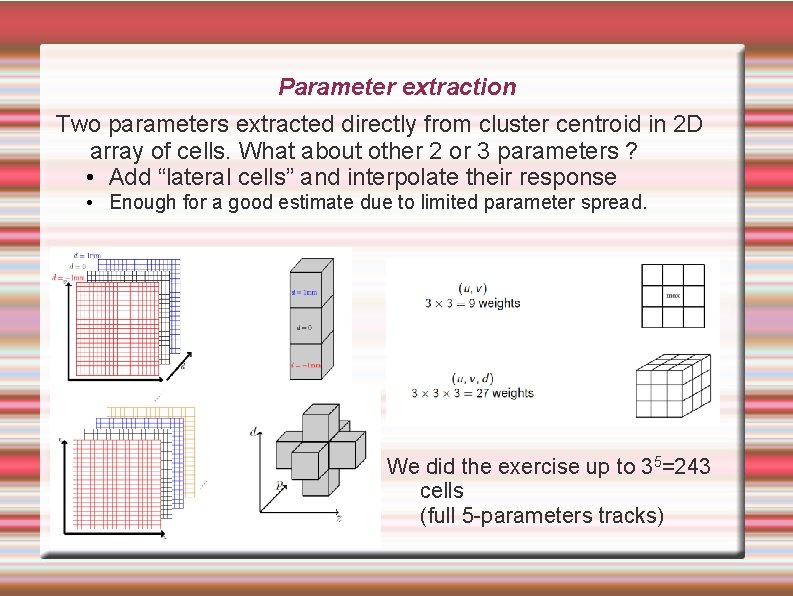

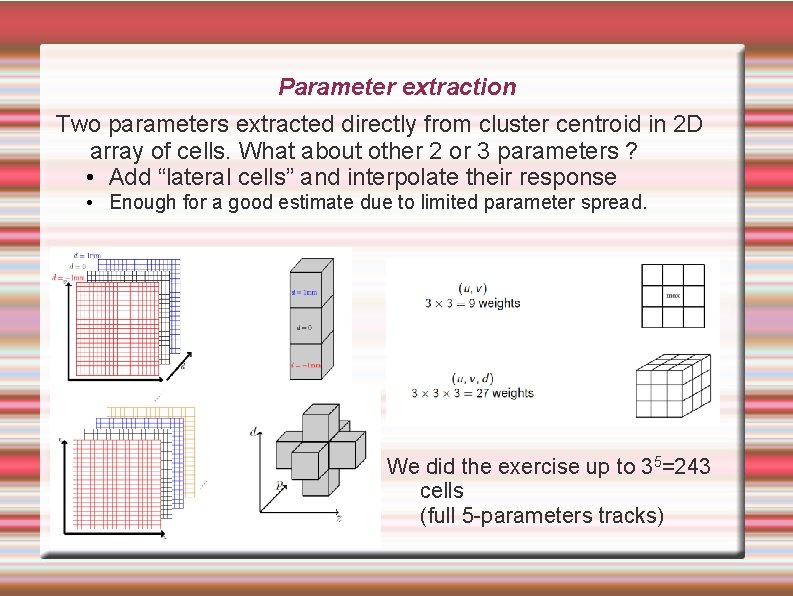

Parameter extraction Two parameters extracted directly from cluster centroid in 2 D array of cells. What about other 2 or 3 parameters ? • Add “lateral cells” and interpolate their response • Enough for a good estimate due to limited parameter spread. We did the exercise up to 35=243 cells (full 5 -parameters tracks)

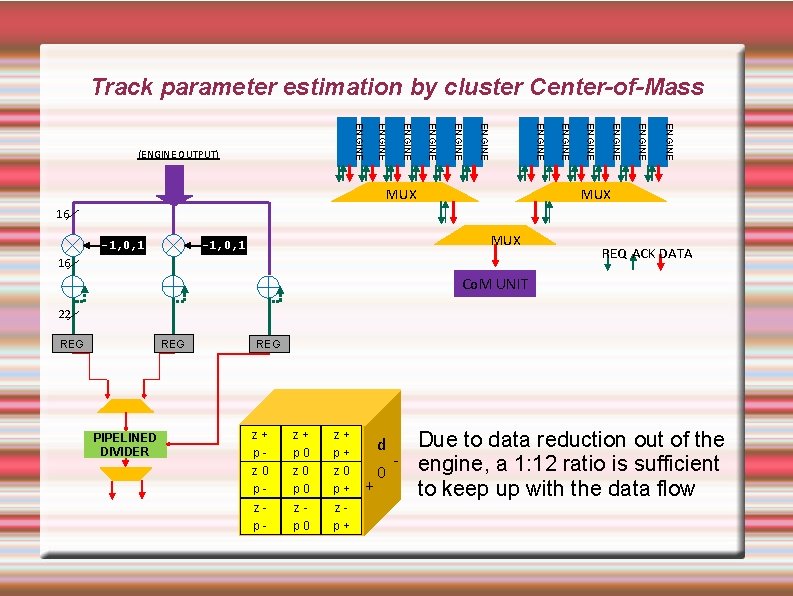

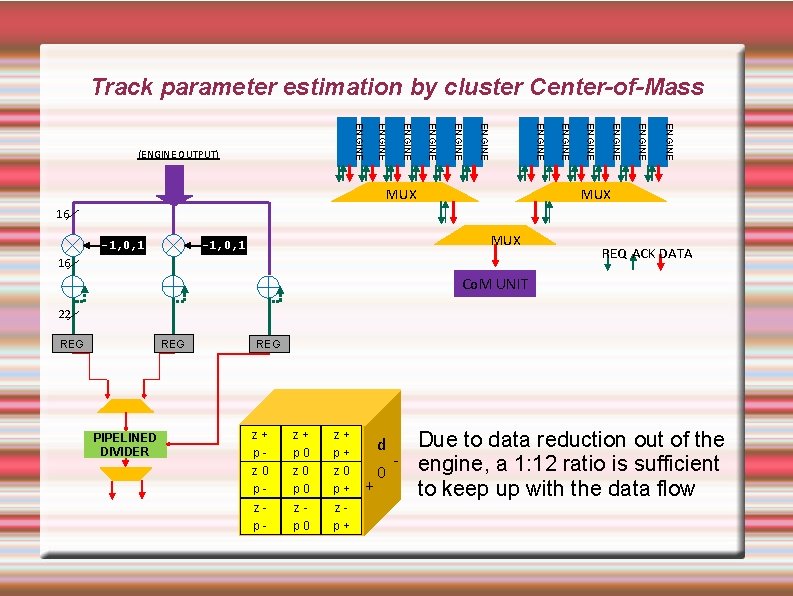

Track parameter estimation by cluster Center-of-Mass ENGINE MUX ENGINE ENGINE (ENGINE OUTPUT) MUX 16 -1, 0, 1 MUX -1, 0, 1 16 REQ ACK DATA Co. M UNIT 22 REG PIPELINED DIVIDER REG z+ z+ z+ p- p 0 p+ z 0 z 0 p- p 0 p+ z- z- z- p- p 0 p+ Due to data reduction out of the - engine, a 1: 12 ratio is sufficient 0 + to keep up with the data flow d

Implementation Use modern, large FPGA devices. • Large I/O capabilities: now O(Tb/s) with optical links ! • Large internal bandwidth (a must !) • Low power consumption • Fully flexible, easy (!) to program and simulate in software • Steep Moore's slope, and easy to upgrade • Highly reliable, easy to maintain and update → Industry's method of choice for complex project with small number of pieces (CT scanners, high-end radars. . . ) low-latency (finance, military)

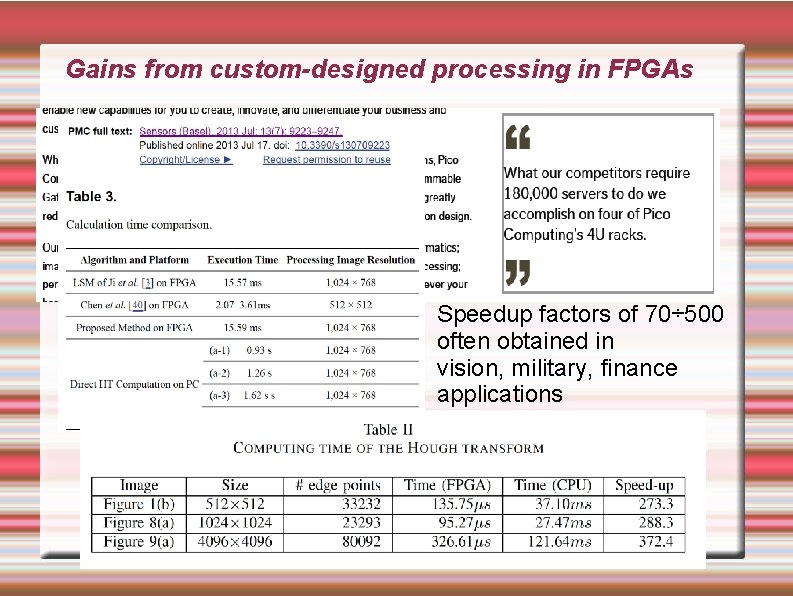

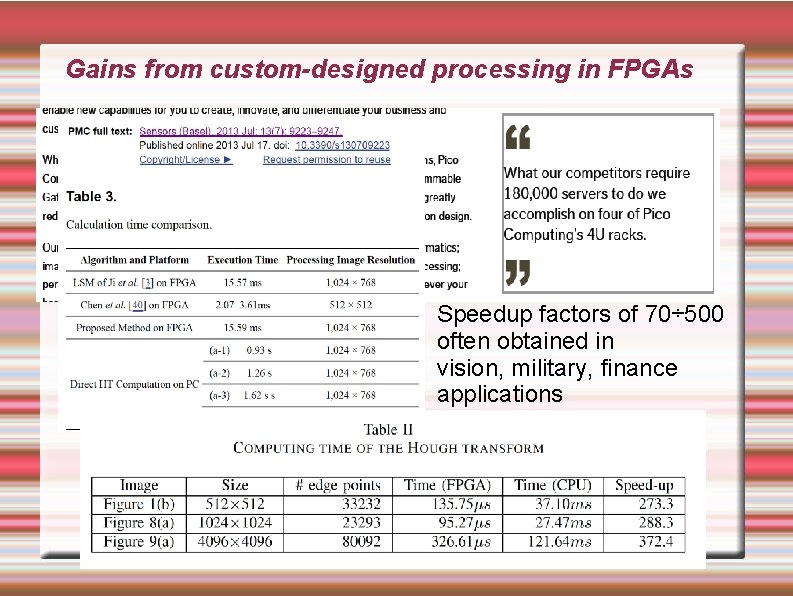

Gains from custom-designed processing in FPGAs Speedup factors of 70÷ 500 often obtained in vision, military, finance applications

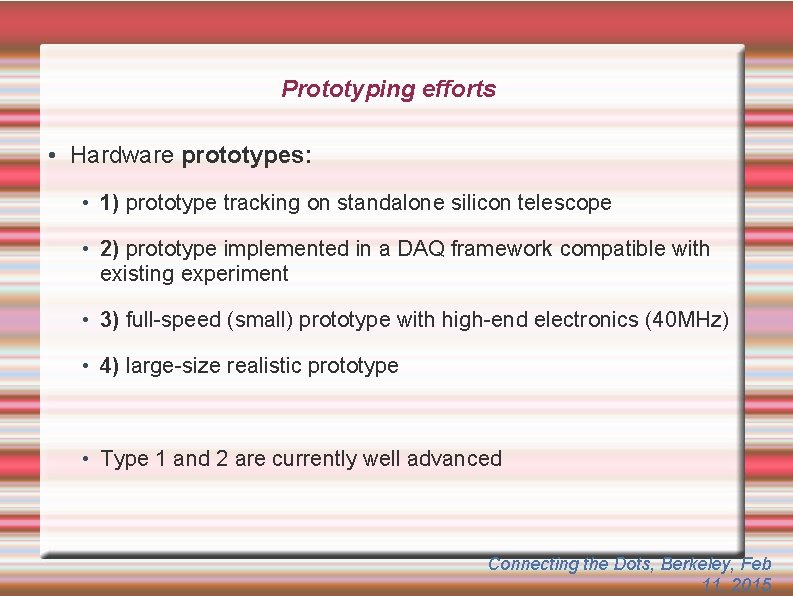

Prototyping efforts • Hardware prototypes: • 1) prototype tracking on standalone silicon telescope • 2) prototype implemented in a DAQ framework compatible with existing experiment • 3) full-speed (small) prototype with high-end electronics (40 MHz) • 4) large-size realistic prototype • Type 1 and 2 are currently well advanced Connecting the Dots, Berkeley, Feb 11, 2015

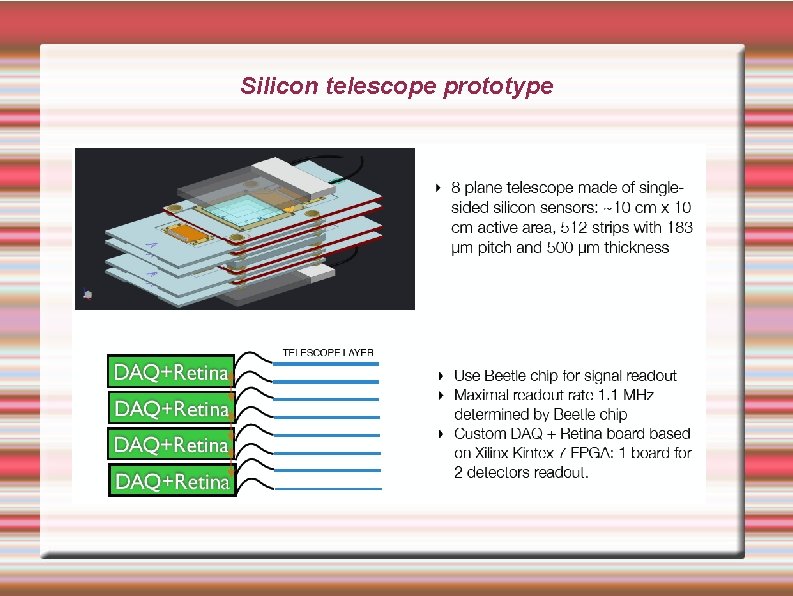

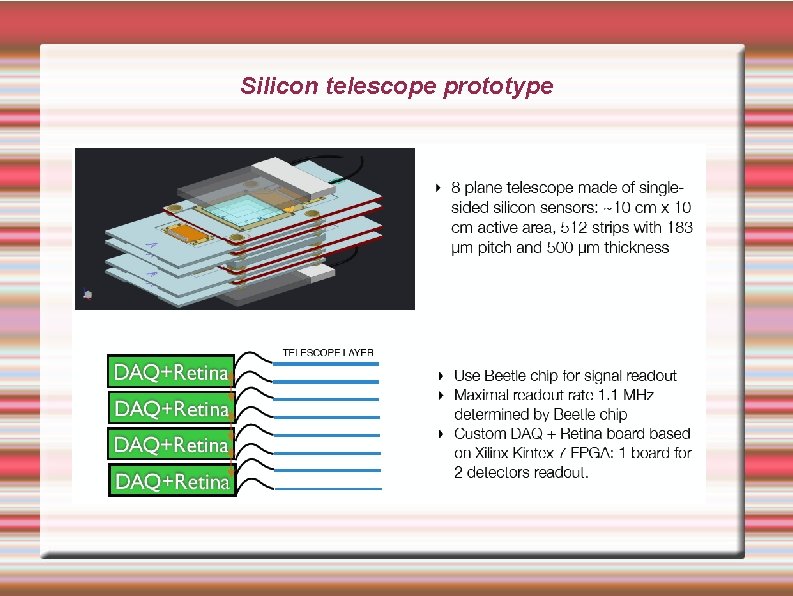

Silicon telescope prototype

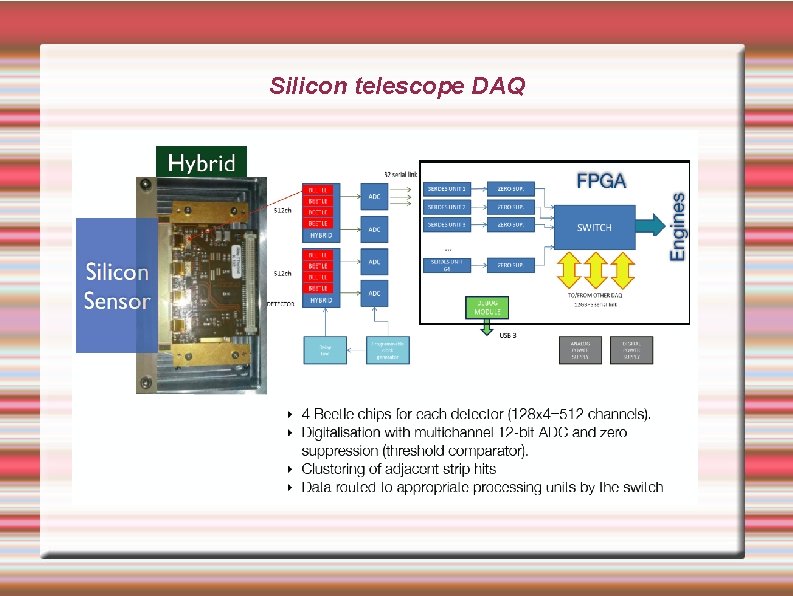

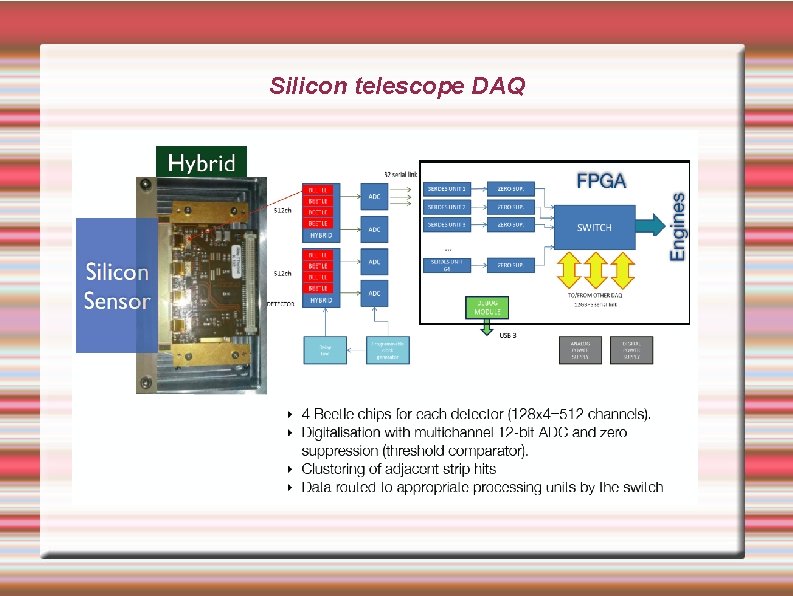

Silicon telescope DAQ

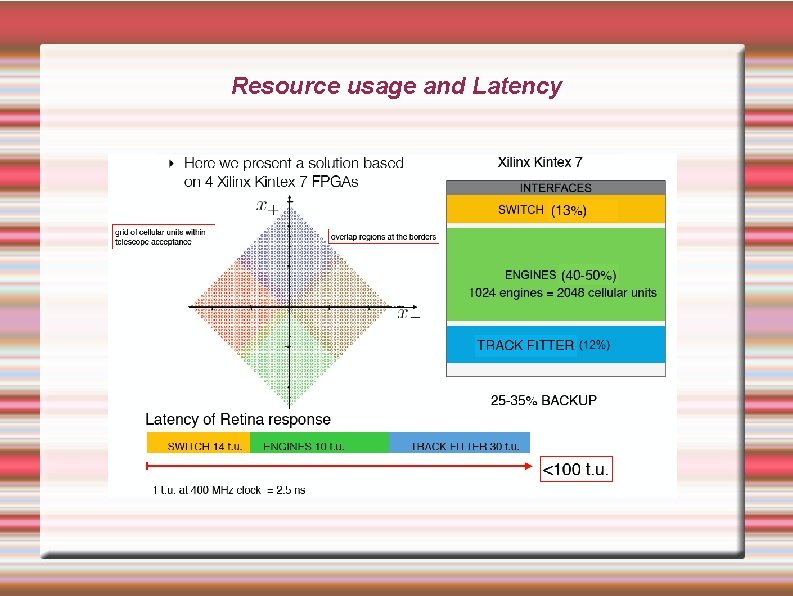

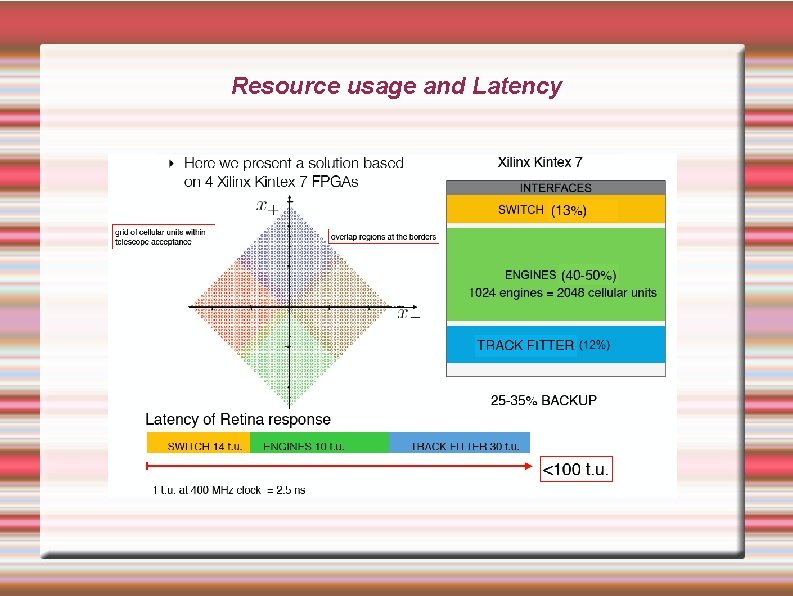

Resource usage and Latency

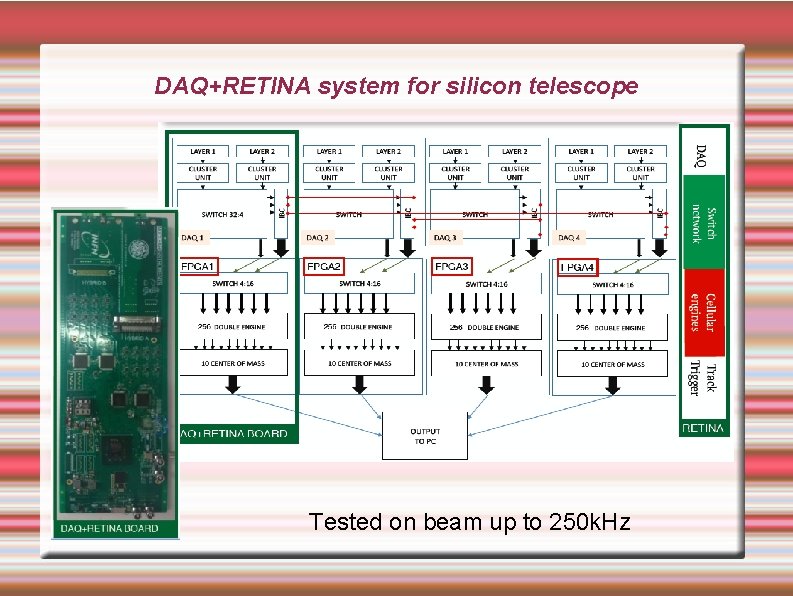

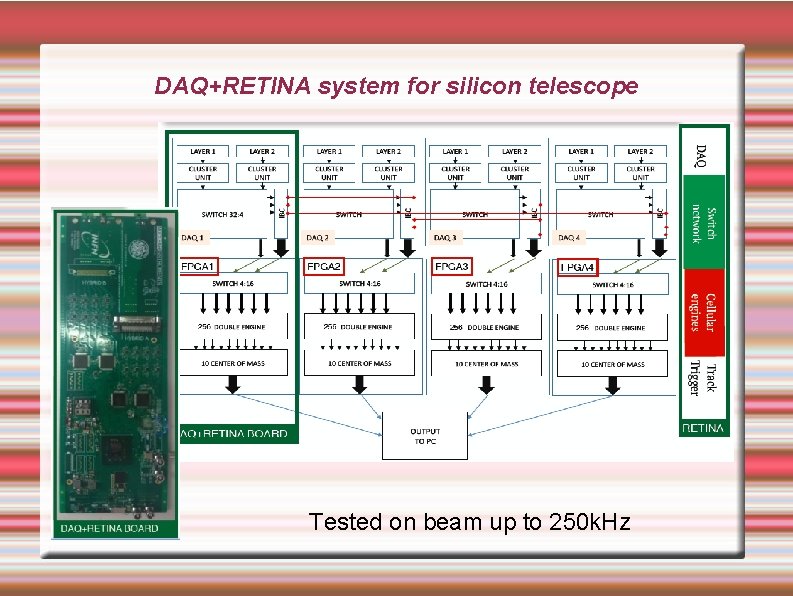

DAQ+RETINA system for silicon telescope Tested on beam up to 250 k. Hz

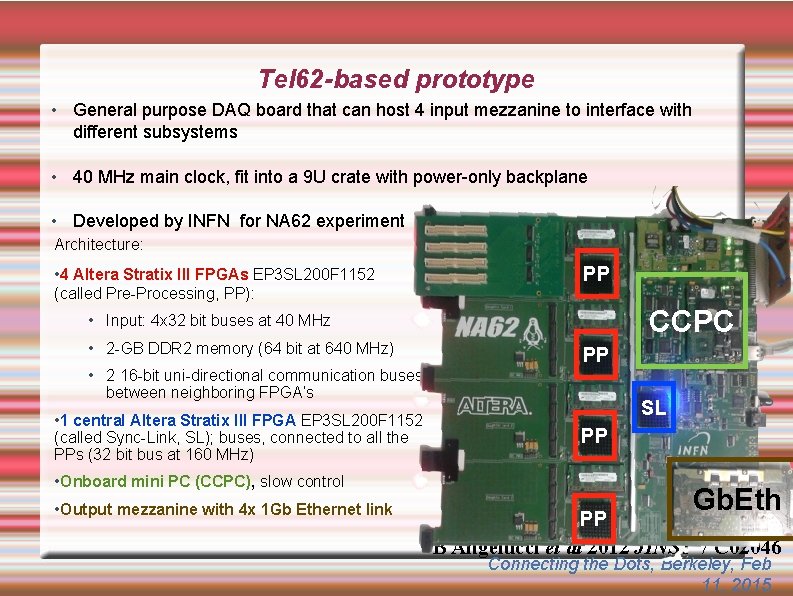

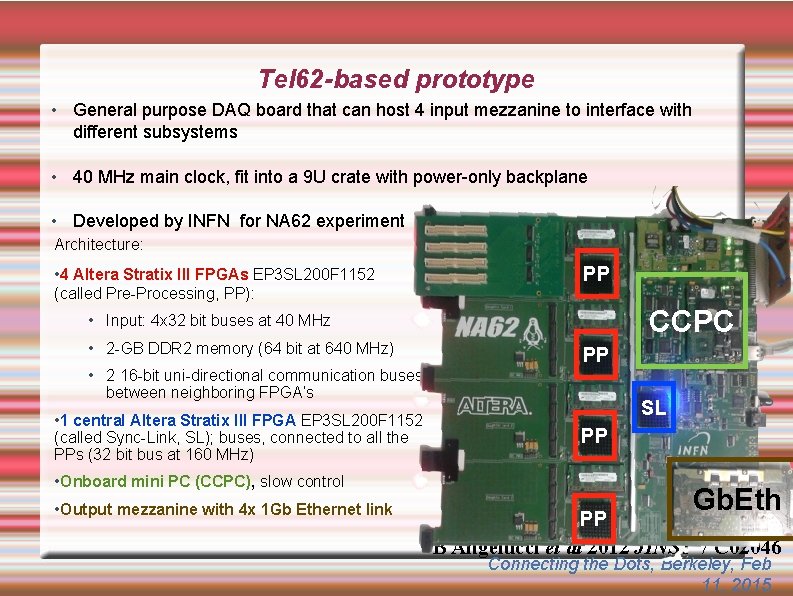

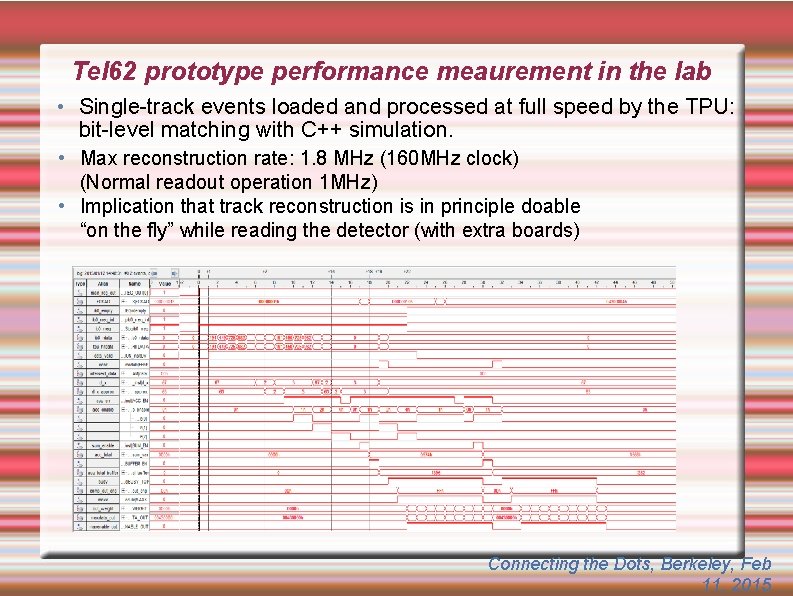

Tel 62 -based prototype • General purpose DAQ board that can host 4 input mezzanine to interface with different subsystems • 40 MHz main clock, fit into a 9 U crate with power-only backplane • Developed by INFN for NA 62 experiment Architecture: • 4 Altera Stratix III FPGAs EP 3 SL 200 F 1152 (called Pre-Processing, PP): PP CCPC • Input: 4 x 32 bit buses at 40 MHz • 2 -GB DDR 2 memory (64 bit at 640 MHz) • 2 16 -bit uni-directional communication buses between neighboring FPGA’s • 1 central Altera Stratix III FPGA EP 3 SL 200 F 1152 (called Sync-Link, SL); buses, connected to all the PPs (32 bit bus at 160 MHz) PP SL PP • Onboard mini PC (CCPC), slow control • Output mezzanine with 4 x 1 Gb Ethernet link PP Gb. Eth B Angelucci et al 2012 JINST 7 C 02046 Connecting the Dots, Berkeley, Feb 11, 2015

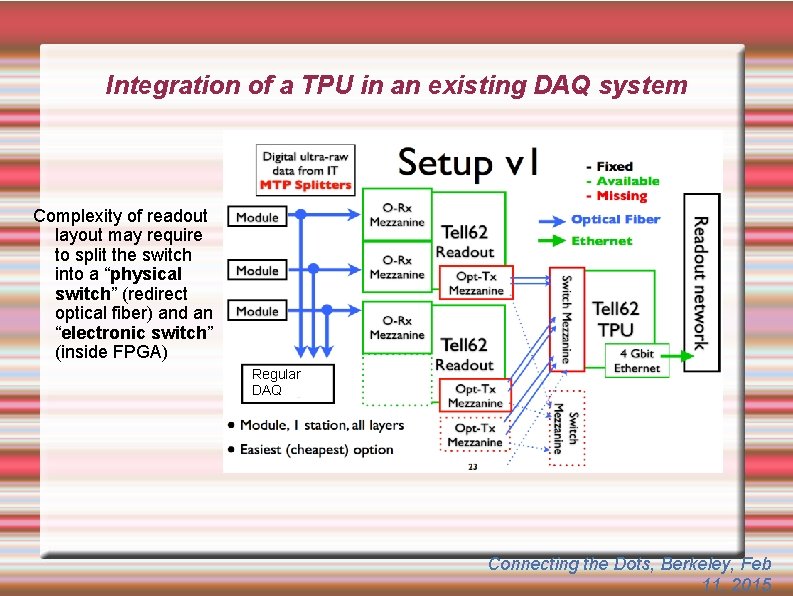

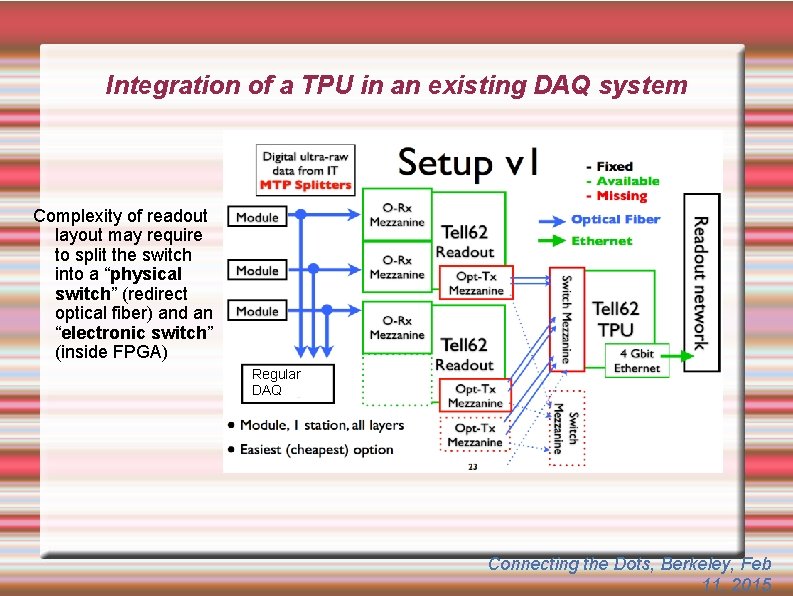

Integration of a TPU in an existing DAQ system Complexity of readout layout may require to split the switch into a “physical switch” (redirect optical fiber) and an “electronic switch” (inside FPGA) Regular DAQ Connecting the Dots, Berkeley, Feb 11, 2015

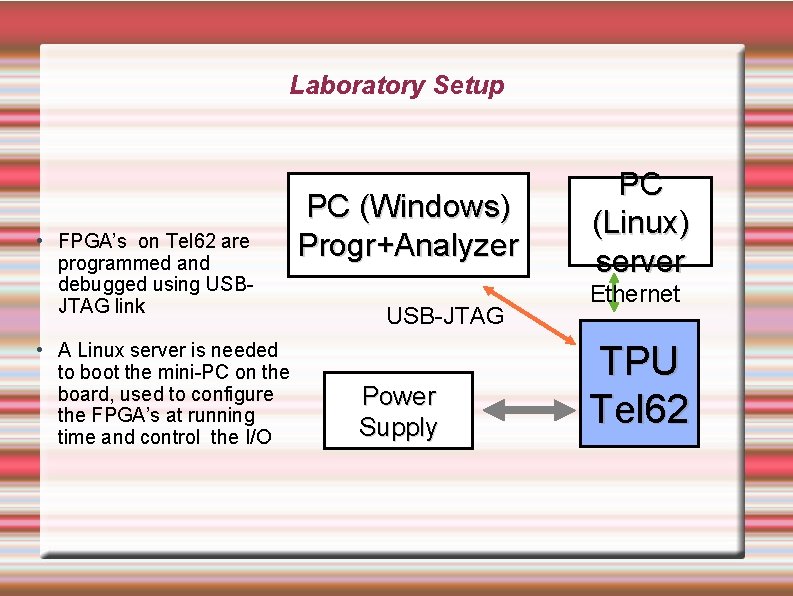

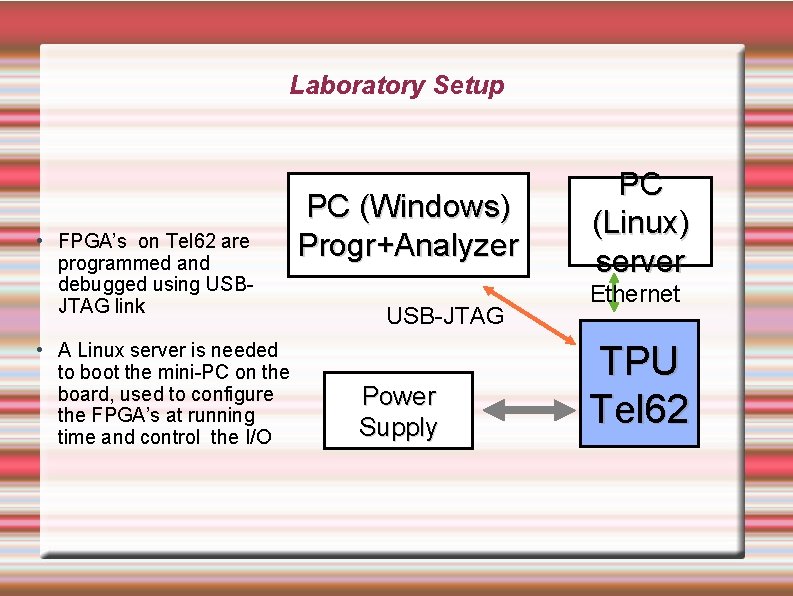

Laboratory Setup • FPGA’s on Tel 62 are programmed and debugged using USBJTAG link • A Linux server is needed to boot the mini-PC on the board, used to configure the FPGA’s at running time and control the I/O PC (Windows) Progr+Analyzer USB-JTAG Power Supply PC (Linux) server Ethernet TPU Tel 62

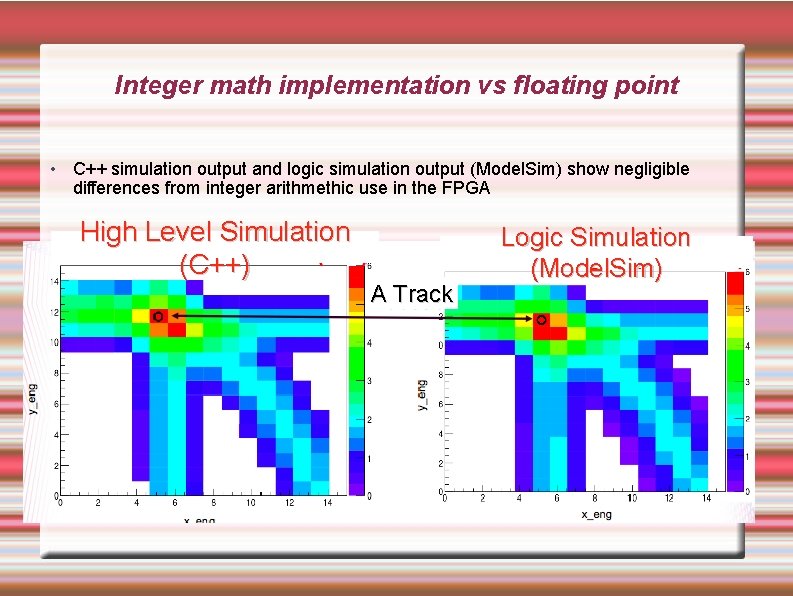

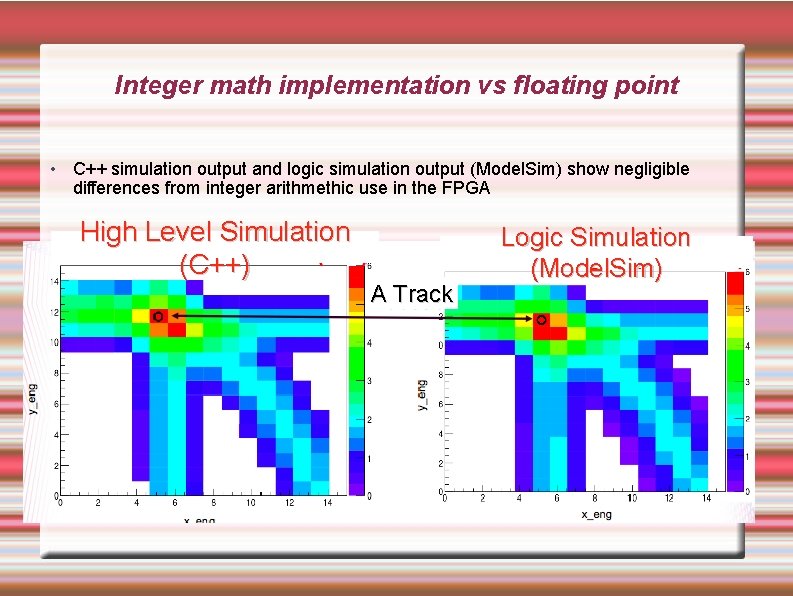

Integer math implementation vs floating point • C++ simulation output and logic simulation output (Model. Sim) show negligible differences from integer arithmethic use in the FPGA High Level Simulation (C++) A Track Logic Simulation (Model. Sim)

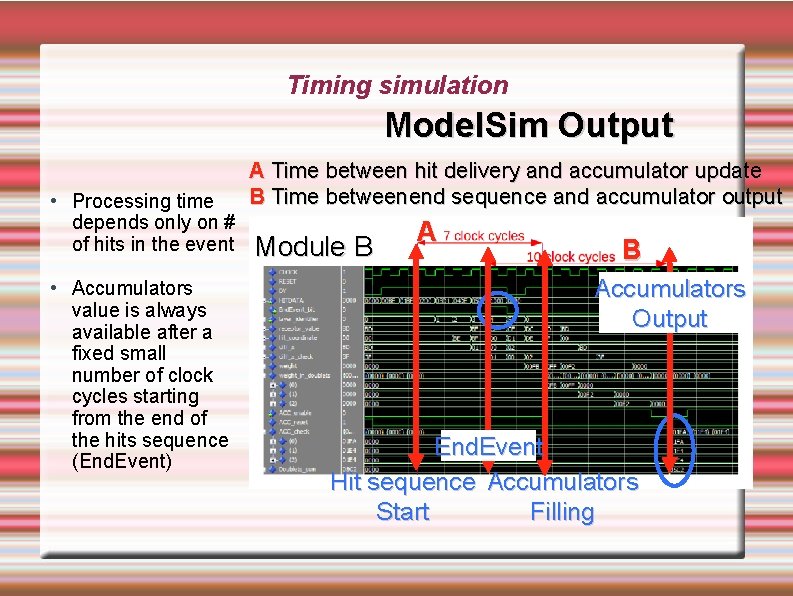

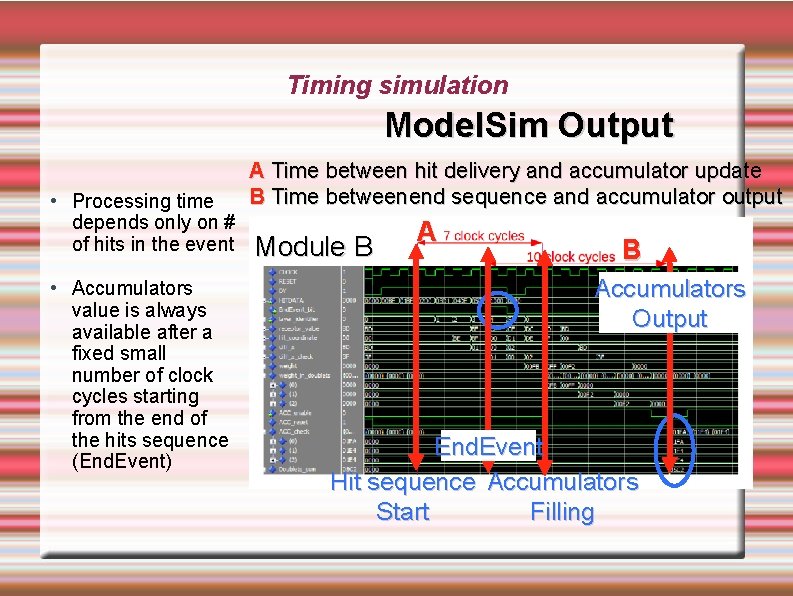

Timing simulation Model. Sim Output • Processing time depends only on # of hits in the event • Accumulators value is always available after a fixed small number of clock cycles starting from the end of the hits sequence (End. Event) A Time between hit delivery and accumulator update B Time betweenend sequence and accumulator output Module B Accumulators Output End. Event Hit sequence Accumulators Start Filling

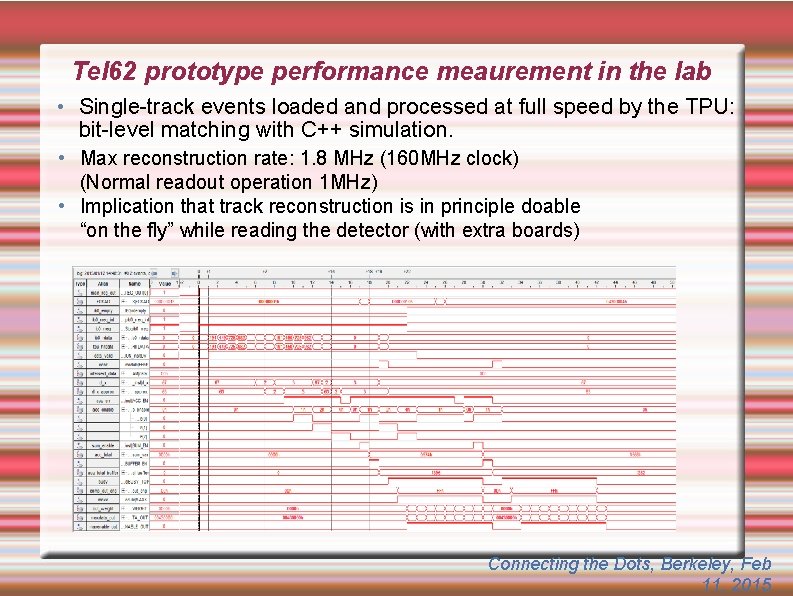

Tel 62 prototype performance meaurement in the lab • Single-track events loaded and processed at full speed by the TPU: bit-level matching with C++ simulation. • Max reconstruction rate: 1. 8 MHz (160 MHz clock) (Normal readout operation 1 MHz) • Implication that track reconstruction is in principle doable “on the fly” while reading the detector (with extra boards) Connecting the Dots, Berkeley, Feb 11, 2015

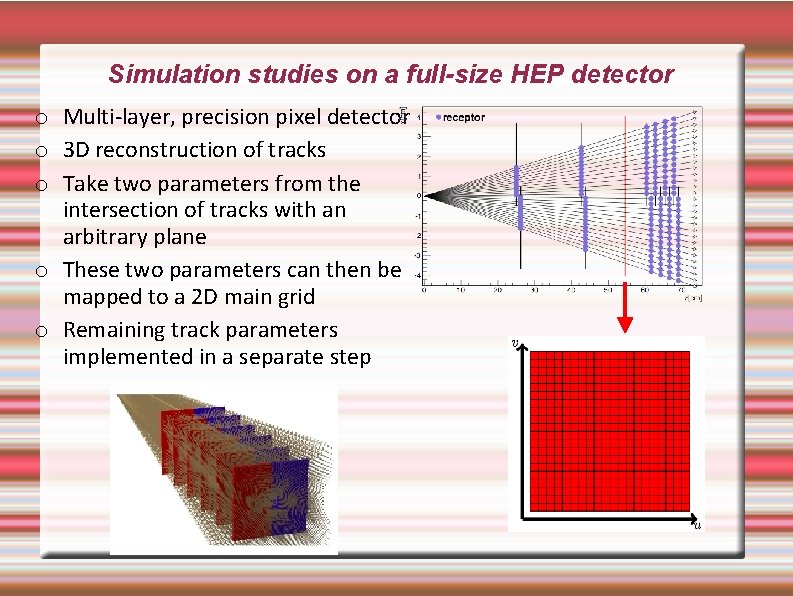

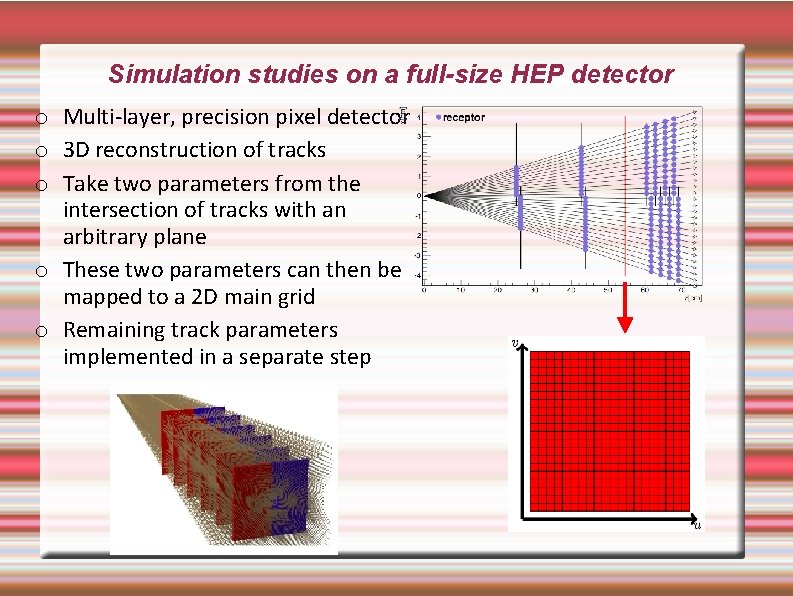

Simulation studies on a full-size HEP detector o Multi-layer, precision pixel detector o 3 D reconstruction of tracks o Take two parameters from the intersection of tracks with an arbitrary plane o These two parameters can then be mapped to a 2 D main grid o Remaining track parameters implemented in a separate step

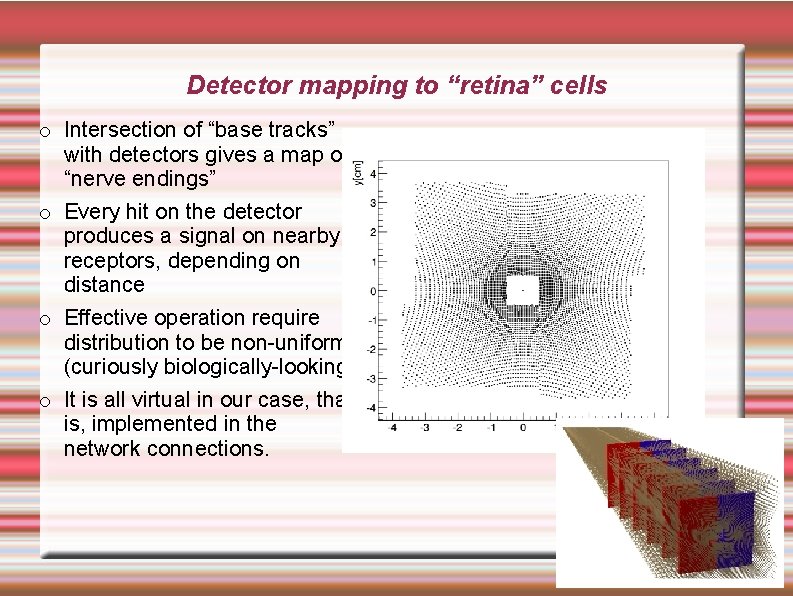

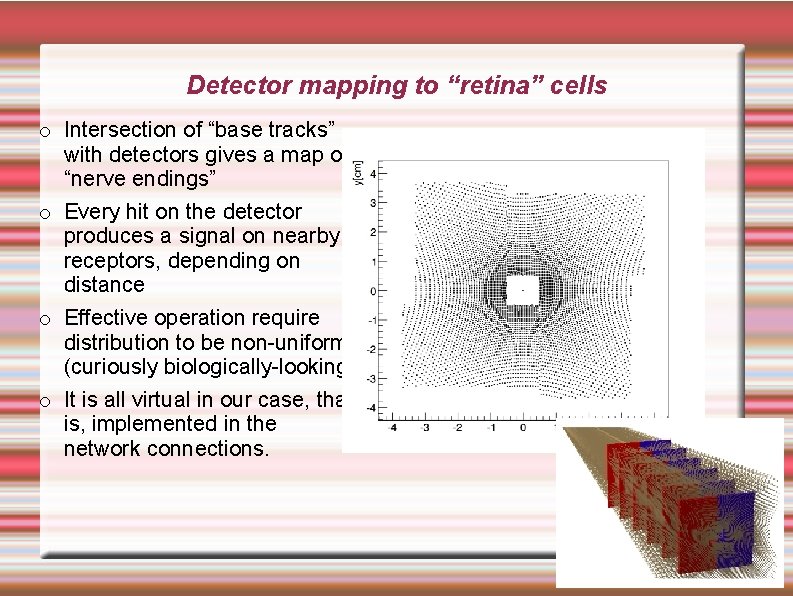

Detector mapping to “retina” cells o Intersection of “base tracks” with detectors gives a map of “nerve endings” o Every hit on the detector produces a signal on nearby receptors, depending on distance o Effective operation require distribution to be non-uniform. (curiously biologically-looking) o It is all virtual in our case, that is, implemented in the network connections.

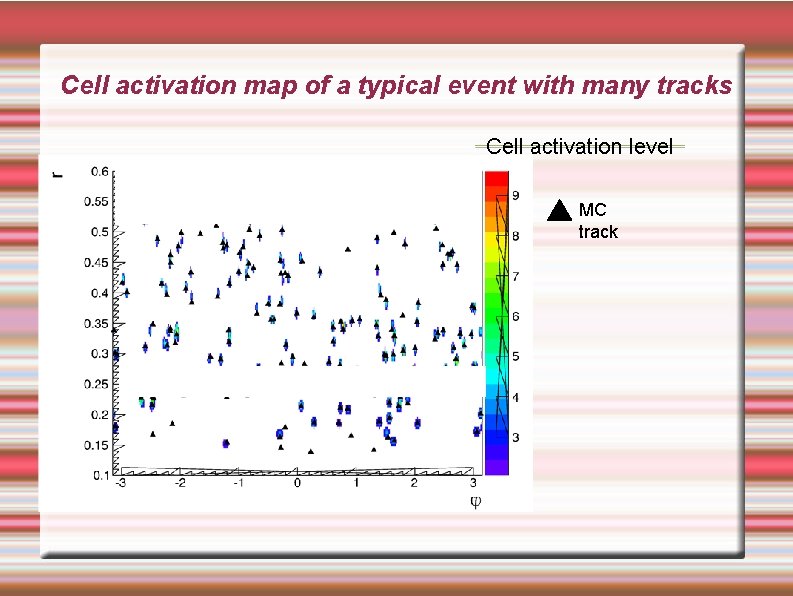

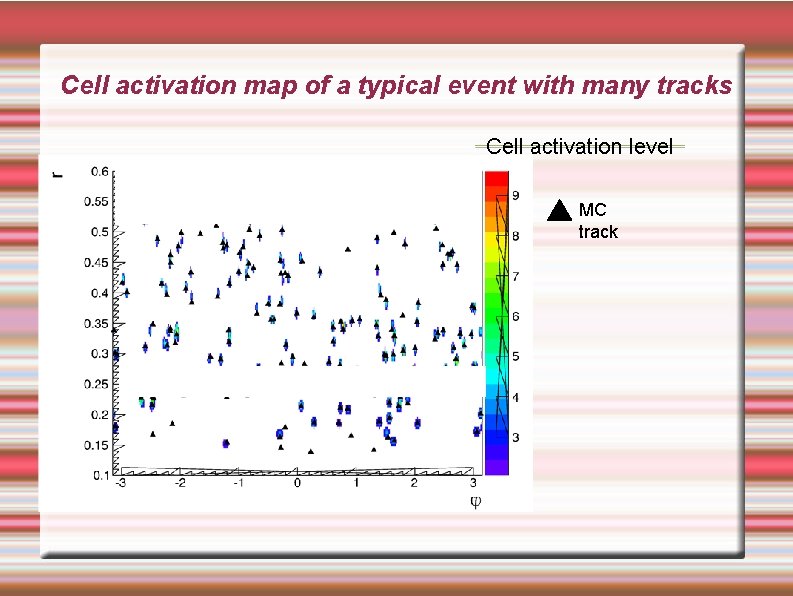

Cell activation map of a typical event with many tracks Cell activation level MC track

Tracking performance measurements Simulate real LHC conditions at L= 2*10^33 The simulated TPU system can process events every 25 ns using O(10^2) large FPGA chips EFFICIENCY/UNIFORMITY Equivalent to offline code z IP MOMENTUM RESOLUTION Very close to offline. Promise of quality reconstruction at LHC crossing frequency

Summary o Future HEP experiments will increasingly depend on large computing power o A key aspect will be the capability of real-time reconstruction by special-purpose processors. o Studies of natural vision show its dependence on similar computational issues and a high level of optimization o RETINA project aimed at designing a better real-time tracking processor using architectures inspired by natural vision o Encouraging preliminary results may lead in the future to a detector-embedded system for data reconstruction.