Reading to the Core Michigan Reading Association Summer

- Slides: 35

Reading to the Core Michigan Reading Association Summer Literature Conference Mackinac Island July 9, 2014 Dr. Elaine M. Weber. Language Arts Consultant, Macomb Intermediate School District

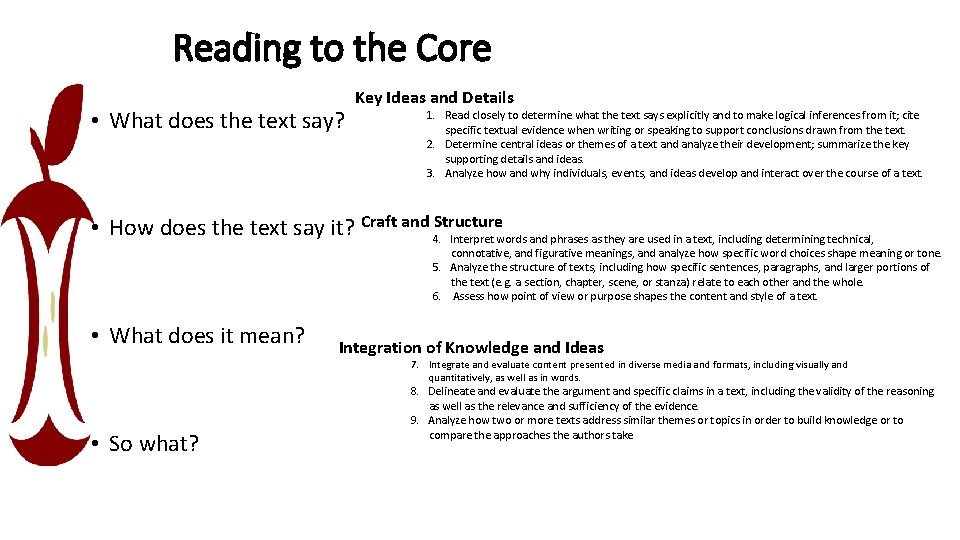

Reading to the Core • What does the text say? Key Ideas and Details 1. Read closely to determine what the text says explicitly and to make logical inferences from it; cite specific textual evidence when writing or speaking to support conclusions drawn from the text. 2. Determine central ideas or themes of a text and analyze their development; summarize the key supporting details and ideas. 3. Analyze how and why individuals, events, and ideas develop and interact over the course of a text. • How does the text say it? Craft and 4. Structure Interpret words and phrases as they are used in a text, including determining technical, connotative, and figurative meanings, and analyze how specific word choices shape meaning or tone. 5. Analyze the structure of texts, including how specific sentences, paragraphs, and larger portions of the text (e. g. a section, chapter, scene, or stanza) relate to each other and the whole. 6. Assess how point of view or purpose shapes the content and style of a text. • What does it mean? • So what? Integration of Knowledge and Ideas 7. Integrate and evaluate content presented in diverse media and formats, including visually and quantitatively, as well as in words. 8. Delineate and evaluate the argument and specific claims in a text, including the validity of the reasoning as well as the relevance and sufficiency of the evidence. 9. Analyze how two or more texts address similar themes or topics in order to build knowledge or to compare the approaches the authors take

Close Reading for the following purposes

Common Core and beyond…

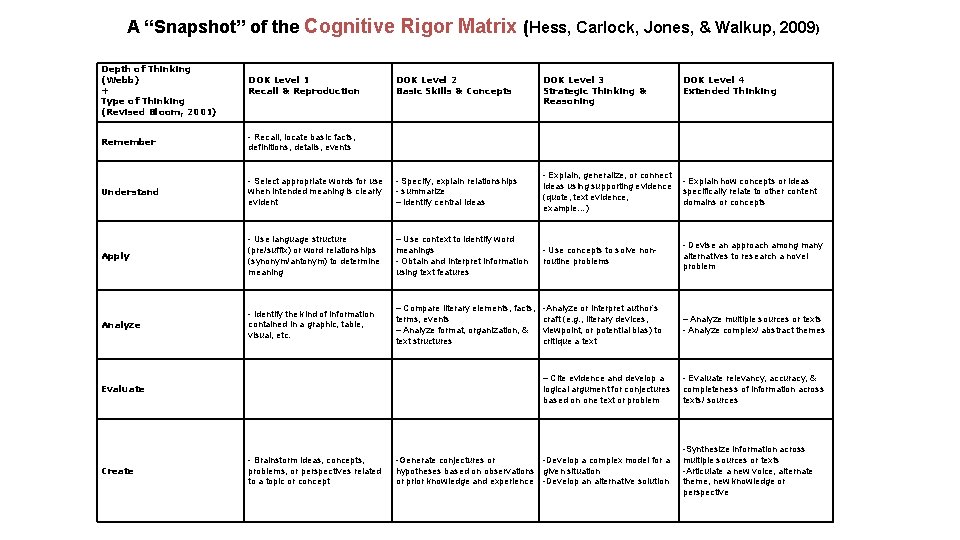

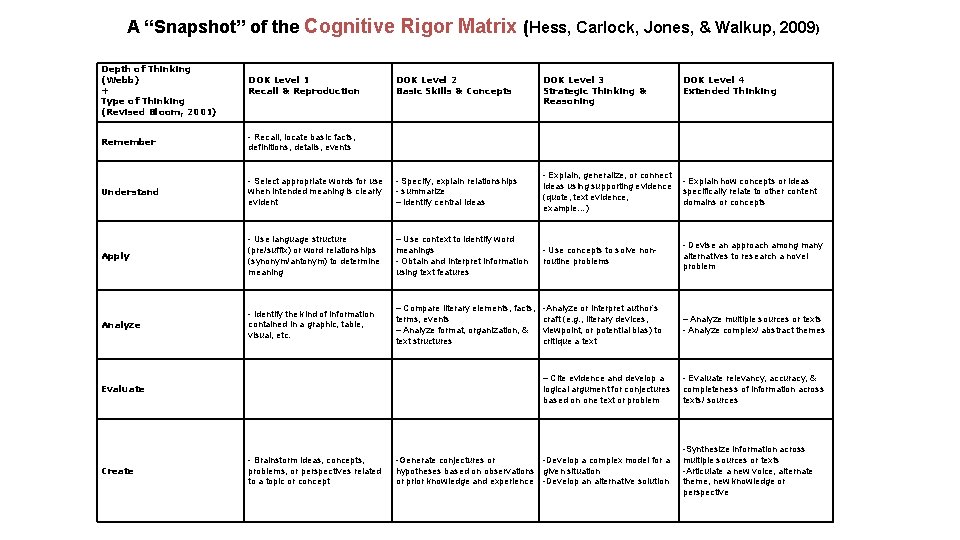

A “Snapshot” of the Cognitive Rigor Matrix (Hess, Carlock, Jones, & Walkup, 2009) Depth of Thinking (Webb) + Type of Thinking (Revised Bloom, 2001) DOK Level 1 Recall & Reproduction DOK Level 2 Basic Skills & Concepts DOK Level 3 Strategic Thinking & Reasoning DOK Level 4 Extended Thinking Remember - Recall, locate basic facts, definitions, details, events Understand - Select appropriate words for use when intended meaning is clearly evident - Specify, explain relationships - summarize – identify central ideas - Explain, generalize, or connect ideas using supporting evidence (quote, text evidence, example…) - Explain how concepts or ideas specifically relate to other content domains or concepts Apply - Use language structure (pre/suffix) or word relationships (synonym/antonym) to determine meaning – Use context to identify word meanings - Obtain and interpret information using text features - Use concepts to solve nonroutine problems - Devise an approach among many alternatives to research a novel problem Analyze - Identify the kind of information contained in a graphic, table, visual, etc. – Compare literary elements, facts, terms, events – Analyze format, organization, & text structures -Analyze or interpret author’s craft (e. g. , literary devices, viewpoint, or potential bias) to critique a text – Analyze multiple sources or texts - Analyze complex/ abstract themes – Cite evidence and develop a logical argument for conjectures based on one text or problem - Evaluate relevancy, accuracy, & completeness of information across texts/ sources Evaluate Create - Brainstorm ideas, concepts, problems, or perspectives related to a topic or concept -Generate conjectures or -Develop a complex model for a hypotheses based on observations given situation or prior knowledge and experience -Develop an alternative solution -Synthesize information across multiple sources or texts -Articulate a new voice, alternate theme, new knowledge or perspective

Thoughtful Reading • http: //www. youtube. com/watch? v=TZBTy. TWOZCM • ex·pli·cate • [ ékspli kàyt ] • explain something: to explain something, especially a literary text, in a detailed and formal way

Your turn to explicate. . We know what we are, but know not what we may be. William Shakespeare

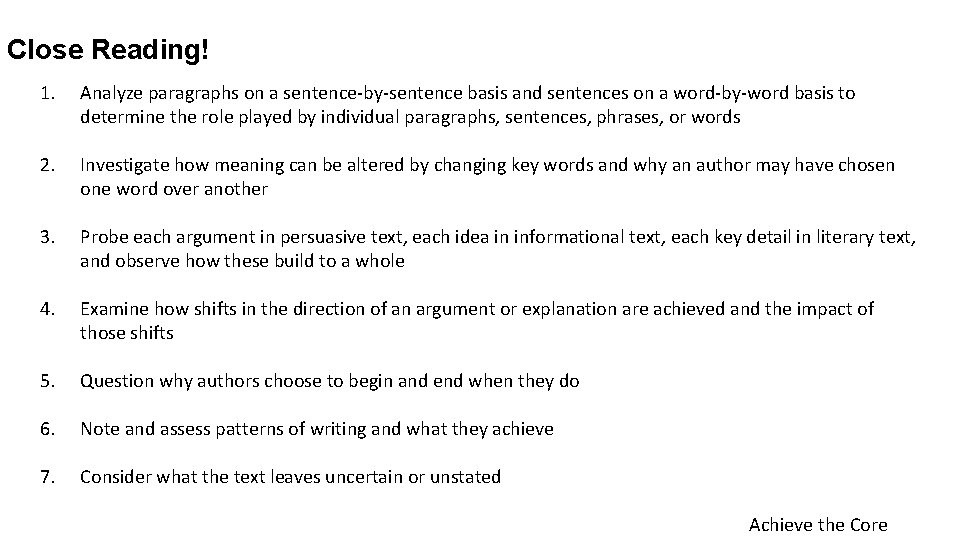

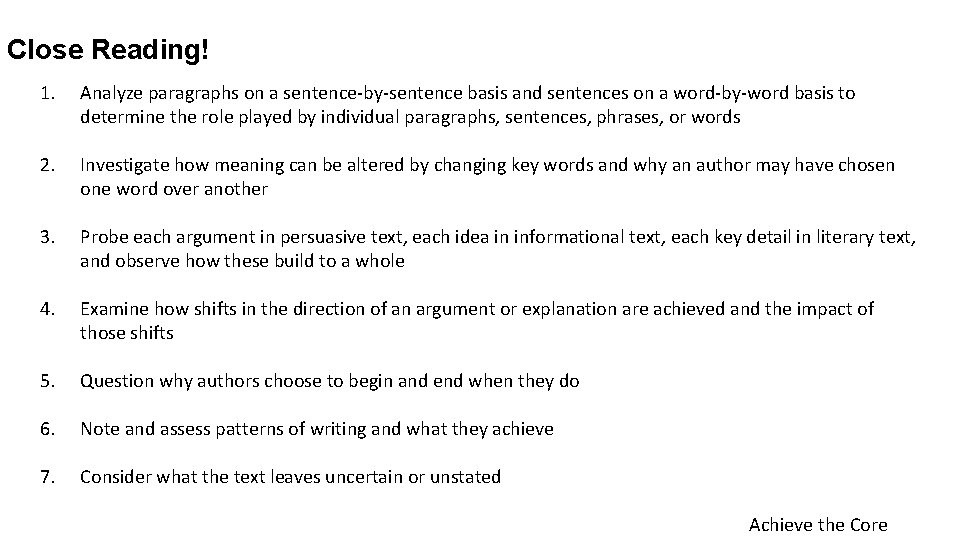

Close Reading! 1. Analyze paragraphs on a sentence-by-sentence basis and sentences on a word-by-word basis to determine the role played by individual paragraphs, sentences, phrases, or words 2. Investigate how meaning can be altered by changing key words and why an author may have chosen one word over another 3. Probe each argument in persuasive text, each idea in informational text, each key detail in literary text, and observe how these build to a whole 4. Examine how shifts in the direction of an argument or explanation are achieved and the impact of those shifts 5. Question why authors choose to begin and end when they do 6. Note and assess patterns of writing and what they achieve 7. Consider what the text leaves uncertain or unstated Achieve the Core

Pledge of Allegiance I pledge allegiance to the Flag of the United States of America, and to the Republic for which it stands, one Nation under God, indivisible, with liberty and justice for all.

Preamble to the Constitution • We the people of the United States, in order to form a more perfect union, establish justice, insure domestic tranquility, provide for the common defense, promote the general welfare, and secure the blessings of liberty to ourselves and our posterity, do ordain and establish this Constitution for the United States of America.

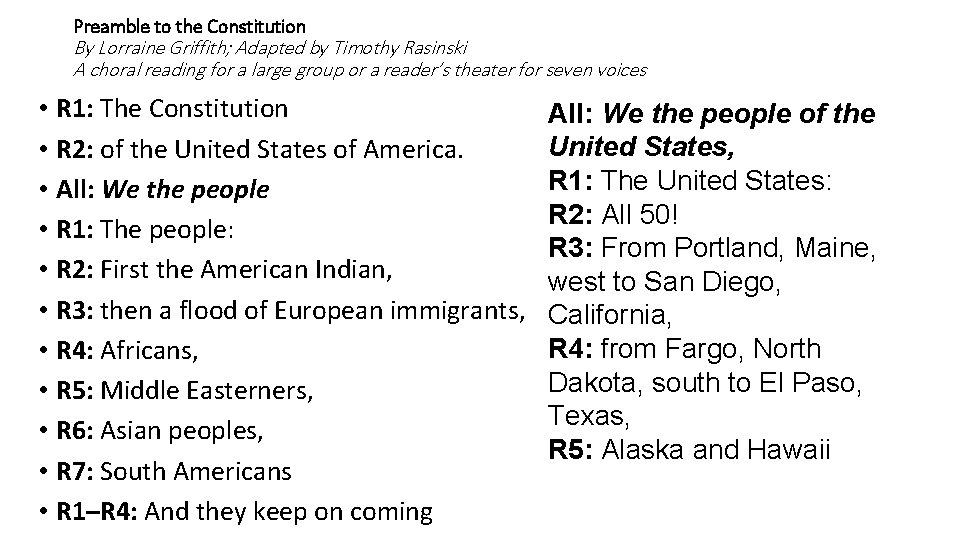

Preamble to the Constitution By Lorraine Griffith; Adapted by Timothy Rasinski A choral reading for a large group or a reader’s theater for seven voices • R 1: The Constitution • R 2: of the United States of America. • All: We the people • R 1: The people: • R 2: First the American Indian, • R 3: then a flood of European immigrants, • R 4: Africans, • R 5: Middle Easterners, • R 6: Asian peoples, • R 7: South Americans • R 1–R 4: And they keep on coming All: We the people of the United States, R 1: The United States: R 2: All 50! R 3: From Portland, Maine, west to San Diego, California, R 4: from Fargo, North Dakota, south to El Paso, Texas, R 5: Alaska and Hawaii

All: We the people of the United States, in order to form a more perfect Union, R 6: That Union seemed perfect, all of the colonies became states as well as the territories to the west, R 7: until the southern states seceded because they wanted states’ rights. R 1: But the Civil War ended with a more perfect union of states based upon the belief that all Americans deserved the right to life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness. . All: We the people of the United States, in order to form a more perfect Union, establish justice, R 2: Even before the established United States, justice was valued. R 3: John Adams had actually defended the British in court after they had attacked and killed colonists during the Boston Massacre. Although he didn’t believe in the British cause, he still believed justice was more important than retribution. R 4: Justice was ensured for Americans by following the fairness of John Adams in establishing a court system beginning with local courthouses and moving up to the Supreme Court in Washington, D. C

www. missionliteracy. com • http: //www. timrasinski. com/presentations/effe ctive_teaching_of_readingfrom_phonics_to_fluency_2009. pdf

Reading to Discriminate When you discriminate between two things, you can tell the difference between them and can tell them apart. What the text says Key Ideas and Details How the text says it. Craft and Structure.

Analytical Reading for craft and structure

John Updike’s Rabbit, Run Outdoors it is growing dark and cool. The Norway maples exhale the smell of their sticky new buds and the broad living-room windows along Wilbur Street show beyond the silver patch of a television set the warm bulbs burning in kitchens, like fires at the backs of caves. He walks downhill. The day is gathering itself in.

Carl Sagan’s “Pale Blue Dot” Look again at that dot. That's here. That's home. That's us. On it everyone you love, everyone you know, everyone you ever heard of, every human being who ever was, lived out their lives. The aggregate of our joy and suffering, thousands of confident religions, ideologies, and economic doctrines, every hunter and forager, every hero and coward, every creator and destroyer of civilization, every king and peasant, every young couple in love, every mother and father, hopeful child, inventor and explorer, every teacher of morals, every corrupt politician, every "superstar, " every "supreme leader, " every saint and sinner in the history of our species lived there--on a mote of dust suspended in a sunbeam.

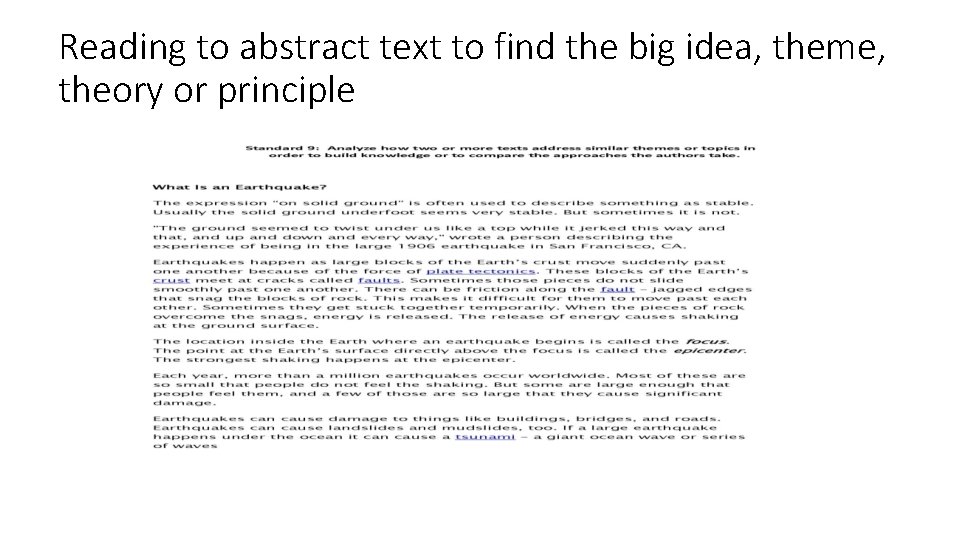

CCSS R 9. Analyze how two or more texts address similar themes or topics in order to build knowledge or to compare the approaches the authors take. The short answer is that earthquakes are caused by faulting, a sudden lateral or vertical movement of rock along a rupture (break) surface. Here's the longer answer: The surface of the Earth is in continuous slow motion. This is plate tectonics--the motion of immense rigid plates at the surface of the Earth in response to flow of rock within the Earth. The plates cover the entire surface of the globe. Since they are all moving they rub against each other in some places (like the San Andreas Fault in California), sink beneath each other in others (like the Peru-Chile Trench along the western border of South America), or spread apart from each other (like the Mid. Atlantic Ridge). At such places the motion isn't smooth--the plates are stuck together at the edges but the rest of each plate is continuing to move, so the rocks along the edges are distorted (what we call "strain"). As the motion continues, the strain builds up to the point where the rock cannot withstand any more bending. With a lurch, the rock breaks and the two sides move. An earthquake is the shaking that radiates out from the breaking rock. Most earthquakes are causally related to compressional or tensional stresses built up at the margins of the huge moving lithospheric plates that make up the earth's surface The immediate cause of most shallow earthquakes is the sudden release of stress along a fault, or fracture in the earth's crust, resulting in movement of the opposing blocks of rock past one another. These movements cause vibrations to pass through and around the earth in wave form, just as ripples are generated when a pebble is dropped into water. Volcanic eruptions, rockfalls, landslides, and explosions can also cause a quake, but most of these are of only local extent. Shock waves from a powerful earthquake can trigger smaller earthquakes in a distant location hundreds of miles away if the geologic conditions are favorable.

Eart hqua kes

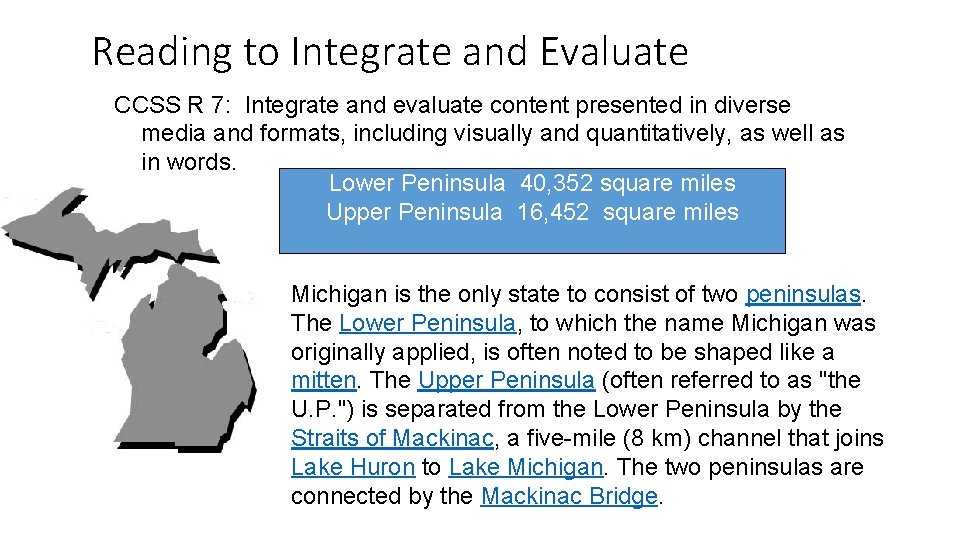

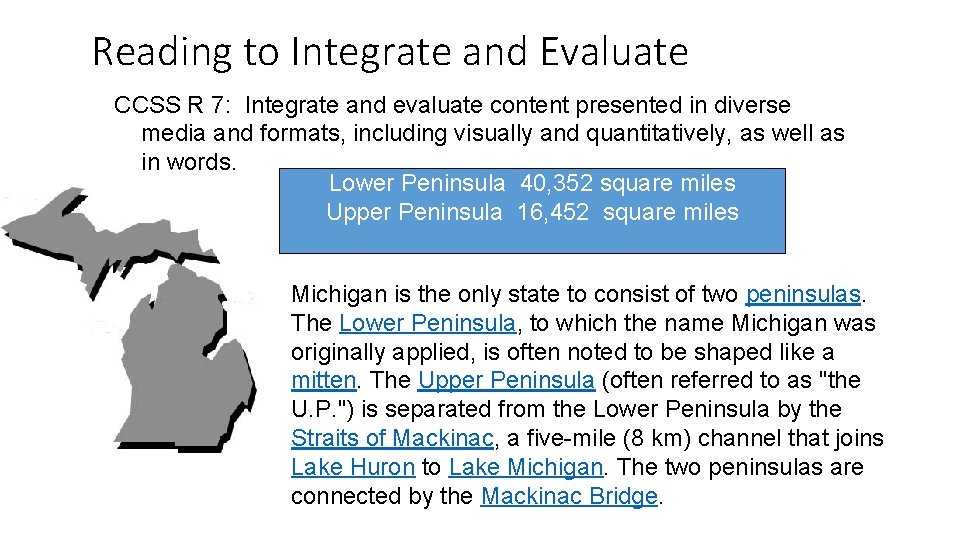

Reading to Integrate and Evaluate CCSS R 7: Integrate and evaluate content presented in diverse media and formats, including visually and quantitatively, as well as in words. Lower Peninsula 40, 352 square miles Upper Peninsula 16, 452 square miles Michigan is the only state to consist of two peninsulas. The Lower Peninsula, to which the name Michigan was originally applied, is often noted to be shaped like a mitten. The Upper Peninsula (often referred to as "the U. P. ") is separated from the Lower Peninsula by the Straits of Mackinac, a five-mile (8 km) channel that joins Lake Huron to Lake Michigan. The two peninsulas are connected by the Mackinac Bridge.

Read to Delineate and Evaluate CCSS R 8. Delineate and evaluate the argument and specific claims in a text, including the validity of the reasoning as well as the relevance and sufficiency of the evidence. Delin eate The Argu ment W h a t i s t h e i s s u e ? What is the issue? What is the claim? What are the reasons? What is the evidence? What is the counterargument? What is the rebuttal? What is the resolution?

What is the issue? What is the claim? What is the evidence? What is the counterclaim? Evaluate Is this an argument of fact, value or judgment, or of policy?

On November 3, 2005 a new law banning people from camping in public will be put into practice in the city of Flagstaff, Arizona (Sleeping banned on right of ways, property within city limits). Many people automatically assume that if they decide to take a quick nap in public that they will be in violation of the new law. The law, in fact, is “prohibiting people from sleeping in a public right of way, or on public property, when it appears they're doing so for living accommodations. ” (Peterson 1). Those opposed to this law do not believe that when people are camping in public they are doing any harm. This is very far from the truth. In fact, having people set up temporary residence in public would indirectly affect the income of many businesses in town.

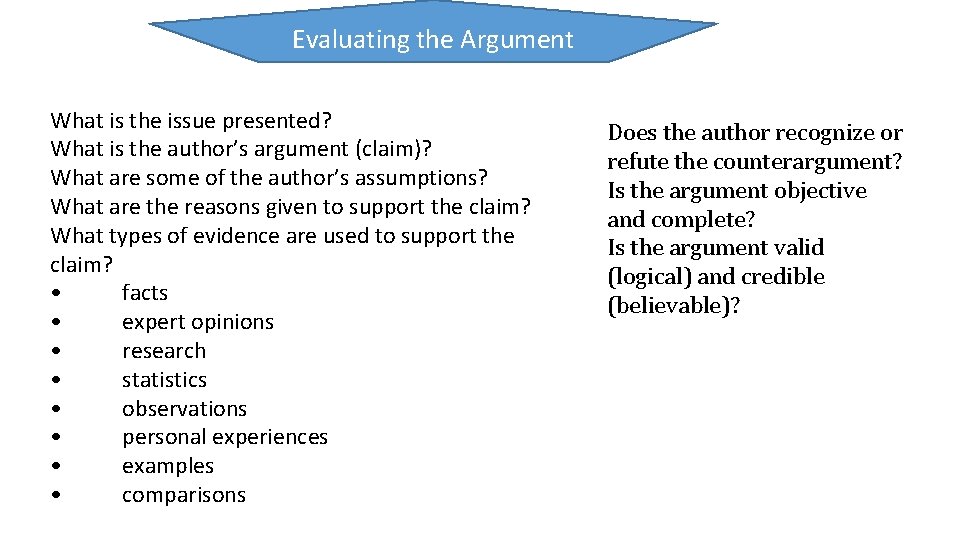

Evaluating the Argument What is the issue presented? What is the author’s argument (claim)? What are some of the author’s assumptions? What are the reasons given to support the claim? What types of evidence are used to support the claim? • facts • expert opinions • research • statistics • observations • personal experiences • examples • comparisons Does the author recognize or refute the counterargument? Is the argument objective and complete? Is the argument valid (logical) and credible (believable)?

Evaluating the Argument What emotional appeals does the author use? • Emotionally charged or biased language • False authority • Appeal to the “common folk” • “Join the crowd” appeal or bandwagon • Ed Hominem – attack on the person rather than his/her viewpoint. Errors in logical reasoning • Circular reasoning/begging the question • Hasty generalization – conclusions derived from insufficient evidence • Non sequitur – It doesn’t follow • False cause

Generative Reading Generative Thinking using Argument 1. Use the “counterargument” of an argument and make it the claim. Establish reasons to support the claim. Support the claim with appropriate evidence. Refute the original claim which is now the “counterclaim. ” Draw a conclusion. 2. Change the type of claim. If it is a Claim of Fact, change it to a Claim of Value or Judgment or to a Claim of Policy. Provide the reasoning and the new evidence that fits the type of claim. 3. Take an argument that is developed deductively (begins with a general statement or premise and moves toward a more specific statement) and rearrange it so that it is inductive (reaching a general conclusion from observed specifics). Find the opposite situation and reverse the arrangement.

Reading to abstract text to find the big idea, theme, theory or principle

Levels of Meaning

Perhaps a couple of quotes from the past are also appropriate. The first is attributed to the great plant hunter Ernest Henry Wilson, who wrote it just three years before his death in 1930: There are no happier folk than plant-lovers and none more generous than those who garden. There is a delightful freemasonry about them; they mingle on a common plane, share freely their knowledge and with advice help one over the stepping stones that lead to success. It is truthfully said that a congenial companion doubles the pleasures and halves the discomforts of travel and so it is with the brotherhood who love plants. (from E. H. Wilson, Plant Hunting, v. 1, 1927)

A second quote comes from one of my former students, who wrote an essay on why people embrace perennials in their gardens. His essay could have been about any of our favorite groups of plants. (Those who believe our students aren’t among the finest in the world need to come and visit my classes. ) Americans, as a rule, live with a certain sense of urgency. Perhaps this is the price we pay for living in such a young country. Why waste time with some fickle plant that will flower only for a few short moments each year when there are countless annuals just begging to bloom all summer long? The commitment perennials require represents the driving force behind gardening as a whole. When someone kills a window box of petunias, there is no love lost. Odds are that a quick trip to Kmart will have the window box blooming again in short order. Let there be no doubt about the glorious beauty of a wellplanted annual garden. But for all their show and eagerness-to-please, annuals provoke no anticipation. To be among an established garden teaches one why we have gardens at all; gardens are our refuge from the irritations of everyday life, places of peace and serenity that provide the hope and anticipation of good things to come. (Ken James, student, 1995)

The Challenge: To drift steadily on and on, distracted, across texts, is as much like deep reading, as stockpiling information is akin to acquiring knowledge. To fully understand the rich intricacy of any writing – from the multilayered symbolism of a novel to the nuanced arguments of great nonfiction, we must go deeply into the text. This is an unavoidable laborious, often uncomfortable yet inevitably rewarding process. (p. 180) - Maggie Jackson Distracted