Rationalist Epistemology Plato and Descartes Readings Quiz 3

- Slides: 66

Rationalist Epistemology Plato and Descartes

Readings, Quiz 3 DP Ch 2 "Rationalist Epistemology" and "The Philosophy of Plato" DP Ch 7 "Ancient Greek Moral Philosophers" (on Plato's ethics only) DP Ch 9 "Political Philosophy" (on Plato's political philosophy only) DP Ch 10 "Plato and Freud" CB The Allegory of the Cave Meno (all) Online

Epistemology is the branch of philosophy that investigates the nature, source, and limits of KNOWLEDGE. You can easily figure out what "epistemology" means if you know a little Greek. "Episteme" is the Greek word for "knowledge, " and you already know what logos means. The following are all typical epistemological questions: 1. Is there any knowledge in the world so certain that no reasonable person could doubt it? 2. Is there any secure basis for our future expectations, or is it just a matter of crossing our fingers and hoping for the best? 3. Does science explain — does it help us to understand anything? or does it merely describe? 4. What, if anything, is the contribution of the senses to

Ancient Greek Rationalism: The first rationalist in Western Philosophy was the ancient Greek philosopher Plato was monumentally important in the history of philosophy. Quiz 3 will focus entirely on Plato's philosophy. Continental Rationalism is a movement in epistemology in the modern period of philosophy (when was that? See the Chronological List of Western Philosophers). So Plato was a rationalist, but not a "Continental Rationalist. " The major figures of Continental Rationalism are Descartes (the focus of Quiz 4), Spinoza, and Leibniz. All the Continental Rationalists are rationalists in the broad sense; i. e. , all share the basic rationalist viewpoint with Plato

Rationalist Epistemology Rationalism in epistemology is the view that knowledge does not come from the senses. According to rationalists, the paradigm of knowledge is mathematics. Rationalists say knowledge comes primarily or solely from reason, or from intuition, or that we possess it innately (from birth).

In contrast, empiricist epistemology is the view that knowledge does come primarily or solely from the senses. But we will talk about this later.

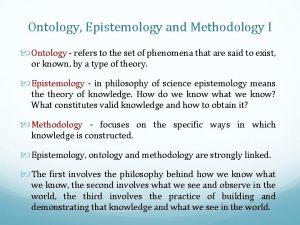

Metaphysics is the branch of philosophy that investigates the general nature of being or reality, especially the being of the sensible world, God, freedom, and souls. The word "metaphysics" is usually synonymous with the word "ontology. " The following are all metaphysical (or ontological) questions:

1. What is reality? 2. What do real things have that unreal things lack? 3. Are some kinds of things (e. g. , material things) more real than others (e. g. , concepts)? 4. Does a tree falling in the forest if no one is around make a real sound? 5. Is God real? 6. Is the mind a separate substance? If so, how does it relate to matter? What is matter? 7. Does human freedom exist? If so, what is it?

Rationalism A priori truths A statement is true or false a priori if no observation or experiment is required to determine if it is true or false. Examples of a priori statements are mathematical assertions, statements true or false by definition, and logical truths and falsehoods. We “just know” when some claims are a priori true or false. For example, we “just know” that the same statement cannot be both true and false in the same sense at the same time (a rule of logic called the law of non-contradiction).

a posteriori truths A statement is true or false a posteriori if observation or experiment is required to determine if it is true or false; we don’t “just know” it. Examples of a posteriori statements are statements about the world, e. g. , “Dogs are carnivores” or “Ottawa is the capitol of Canada. ”

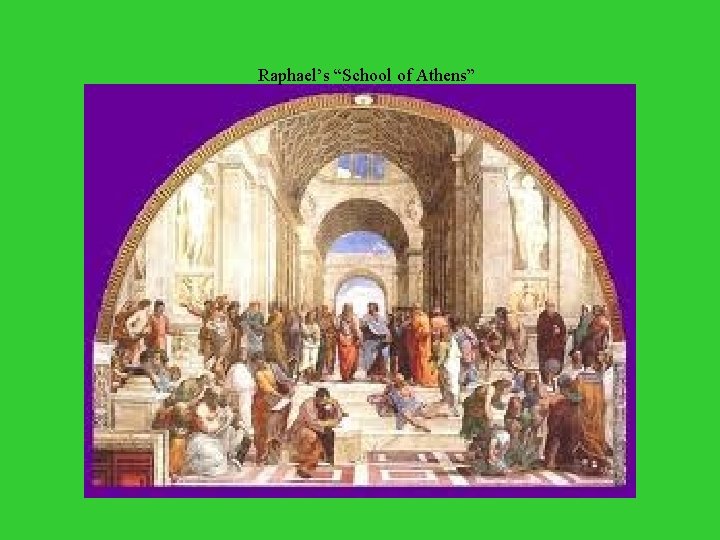

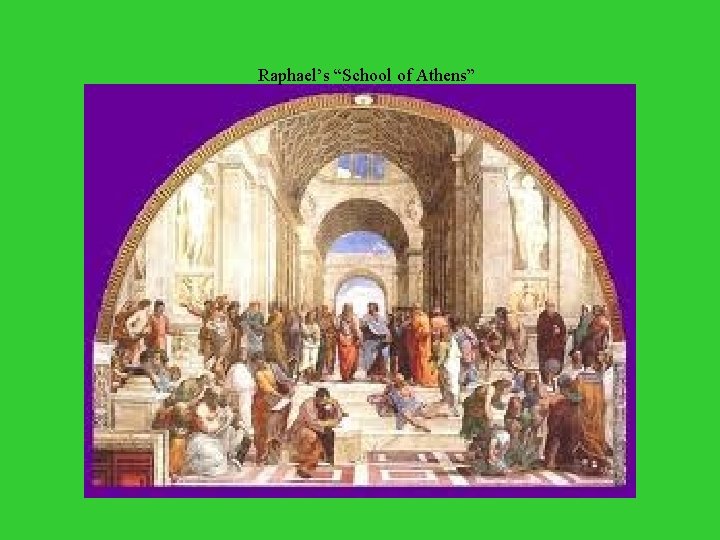

Raphael’s “School of Athens”

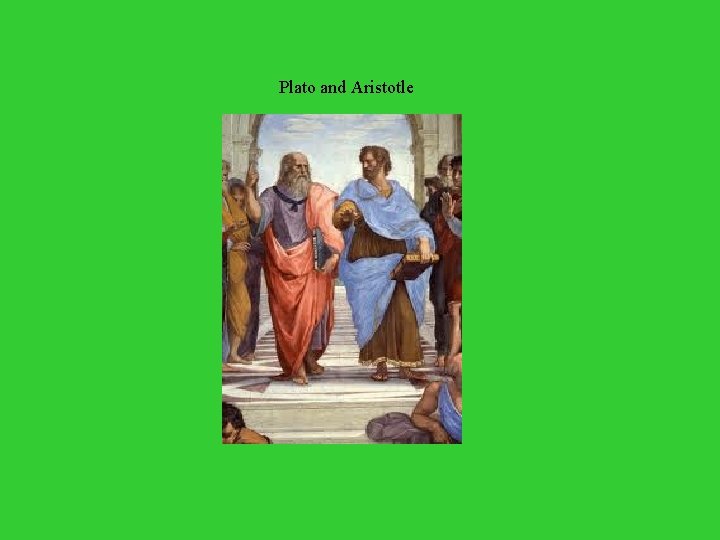

Plato and Aristotle

Plato’s Meno The dialog takes place around 402 BC, about 3 years before Socrates’ trial and execution. The character Anytus was later one of Socrates’ main accusers at the trial. Meno asks, “Can virtue (arete) be taught? ”

Meno • Phase I of the Meno (70 -80) has Socrates asking Meno for a general definition of arete, since as Socrates points out, we can’t figure out if arete can be taught if we don’t have a clear idea what it is. Note Socrates is looking for a general, or formal definition of arete, not just examples or instances of it. Socrates wants to know what all the examples of arete have in common: the “essence” or “form” of arete.

• Socratic Paradox The statement of the so-called Socratic paradox appears at 77 c-78 b. The Socratic paradox is Socrates’ apparent claim that arete is a kind of knowledge, and vice a kind of ignorance. It is a paradox (an odd or unusual claim) because people usually think a person can know the good and still fail to do it. That is, people usually think that arete is more than a matter of knowing; it is, people think, also a matter of willing. Christians, for example, think of sin as a matter of knowing what one should do and not doing it. But if virtue is knowledge, as Socrates says, anybody who really knew the good would automatically be good. If Socrates is right that arete is a kind of knowledge, it would be impossible to know the good and not be good.

Phase II • Begins with Meno’s challenge to Socrates at 80 d-e: if you don’t know what arete is already, you can’t even look for it, because if you don’t know what it is already, then even if you look, you won’t know when you’ve found it. Alternatively, if you know what it is you don’t need to look for it. • Socrates claims that knowing is a kind of remembering (i. e. , you do know what arete is already), and Socrates’ famous demonstration of the ignorant slave boy “remembering” geometry as a result of Socrates’ questioning.

Phase III (86 c-end) • Socrates reluctantly agrees to explore whether virtue can be taught. He proposes a strategy: first determine if virtue is a kind of knowledge. Then if it is, we’ll conclude it can be taught. And if virtue isn’t knowledge, we’ll conclude it can’t be taught. • In 87 -89 c, Socrates points out there are teachers for medicine, horsemanship, etc. and everybody agrees that these are genuine teachers, whereas people disagree about whether the Sophists really do teach virtue. Maybe this is because virtue cannot be taught. • Anytus now appears. Anytus mistakenly thinks that because Socrates has mentioned the Sophists as possible teachers of virtue, that Socrates must approve of the Sophists. (Anytus does not understand that Socrates was being ironic. ) Anytus is vehemently opposed to the Sophists. Socrates agrees with Anytus about the Sophists; but Socrates insists that Anytus give reasons for his opposition to them. Anytus can’t give any reasons. Socrates keeps asking until Anytus walks away furious, thinking he has been “dissed. ”

• (Phase III) In the last pages of the Meno, none of the early questions — whether virtue is knowledge, whether virtue can be taught, the nature of virtue itself — are answered. • But we arrive at some clarity about an unexpected issue: the nature and importance of knowledge. Knowledge is justified true belief. You need the justification — you need to be able to explain and support your true belief — because otherwise knowledge “flies away” like the statues of Daedalus. • Plato doesn’t point this out explicitly, but it’s clear we’ve just seen a perfect example, in Anytus, of the shortcomings of unjustified true belief.

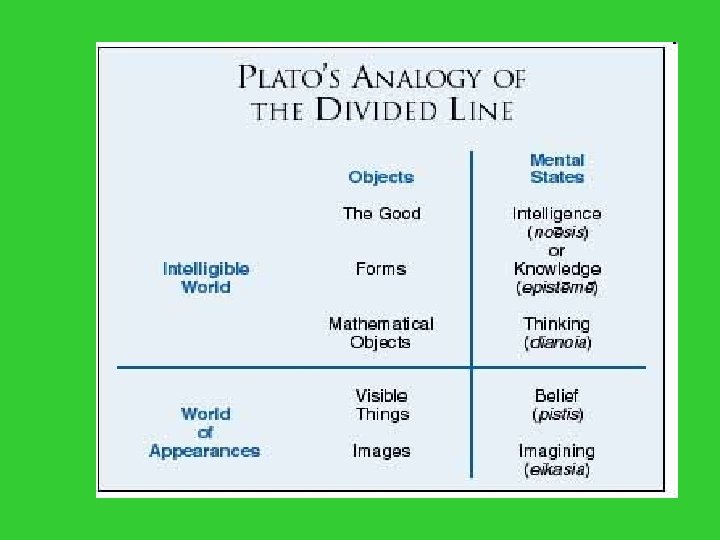

Plato’s Epistemology • Plato studied geometry with the Pythagoreans. He was amazed that geometrical statements — such as “The area of the circle is πr 2” — were true of all circles (universally) and were always true (unchanging). • Math demonstrates that universal and unchanging knowledge exists. For Plato, universal and unchanging knowledge is clearly better (“higher”) than particular and changing (sensory) knowledge. • In fact, for Plato, so-called “knowledge” from the senses, which is particular and changing, shouldn’t really be called knowledge at all.

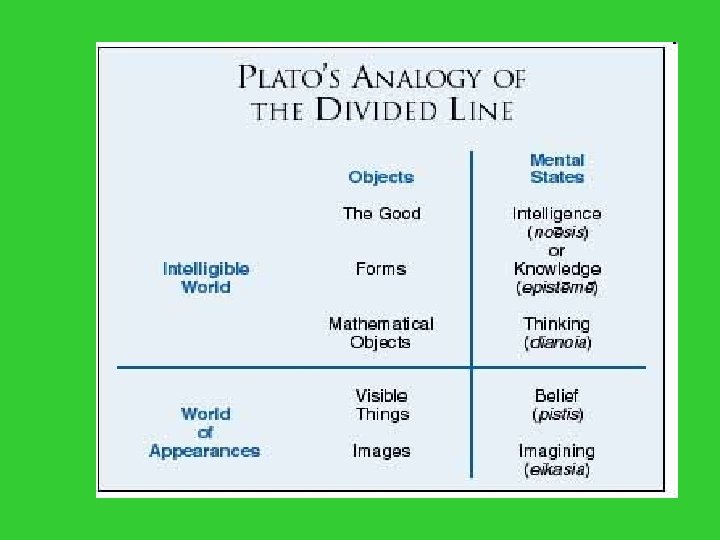

Plato’s metaphysics • For Plato, as for us, all knowledge is intentional, i. e. , knowledge of something. If the geometers know something, then, there must be something they know. The unchanging universal realities known through math — such as “the circle” — must exist. That is, math knowledge reveals a world of universal and unchanging realities. Plato calls these realities the Forms. What are Forms? • Forms are archetypes or models. Things in the world of the senses “imitate” or “participate in” Forms. • Plato reasons that there must be Forms for every thing that has being: trees, rocks, stars, circles, etc. Plato is especially interested in Forms of moral and aesthetic characteristics such as Beauty (the thing all beautiful things have), Courage (the thing all courageous people have), and Goodness (the highest Form). • Forms are changeless. Things in the world of the senses change; they go in and out of being. The Forms, according to Plato, do not change. For example, the Form of Treeness does not lose its leaves, or die. Thus, for Plato, the Forms have more reality or being than things in the world of the senses. Conversely, a thing has less reality the farther removed it is from its Form.

What are Forms? • Forms are mind-independent and objective realities. They are not just mental constructs • Forms are non-physical entities, perceivable by the mind or reason but not by the senses. • Forms are Eternal. Though individual circles or cats may perish. “Circle” itself, or “Cat” itself never perishes. • Forms are divine. • Forms are the true objects of knowledge. • Everything that exists is what it is because it participates in the forms. • The forms are Plato’s answer to the central questions of metaphysics, epistemology and ethics.

Allegory of the Cave Activity Make a drawing of Plato’s Cave which includes as many elements as you can find. Then interpret what you think the elements symbolize using the Analogy of the Divided Line.

Plato’s Ethics • A person is good, more courageous, etc. depending on how much their actions participate in the form of Good or Courage • A person becomes good to the extent that their reason is in control of the other elements of their soul. • The better a person can reason (simultaneously coming closer to apprehension of the ultimate Form, the Form of the Good), the better (and more human) a person is. The most realized, highly-developed, rational, and real person is the one who knows Goodness itself.

The Challenge of Glaucon • In Plato’s major work The Republic, Glaucon challenges Socrates to prove that being a just or good person is in your best interest. He narrates the story of the Ring of Gyges.

Tripartite Theory of the Soul For Plato there are three parts of the soul: • Reason is the faculty of the soul that can do math-type, abstract thinking, and thus apprehend the Forms. • Spirit (Thymos) Dignity, honor, aggressive energy • Appetite is the desire for food, sex, drink. Bodily pleasures.

Socrates’ Answer to Gaucon • A well-ordered, good, soul is one in which Reason rules. Such a soul, at its best, exercises virtue effortlessly as a result of the transformative experience of Goodness itself. Such a soul is psychically integrated, happiest, sanest, most moral, most free, and most fully human. Plato’s answer to Glaucon, then, is that one should strive to be a moral person because being moral, being reasonable, being happy, being sane, being free, and being fully human are all the same thing. • One whose soul is not well-ordered, not ruled by reason, is psychically dis-integrated, unhappy, immoral, a slave to passion, less than human. The psychically dis - integrated soul is sick; it is afflicted with akrasia (the origin of the English word "crazy").

Political Philosophy Plato thinks the State is also composed of three parts: • The class of those who reason well (Philosophers) - Reason • The Guardians (soldiers) – Spirit • Artisans/craftspeople/business people - Appetites

Just State A just state is a state with an analogous structure to a just individual. It should be ruled by philosophers (the most rational) with the aid of the guardians (the most spirited) over the largest sector – the business/craft/manufacturing class.

Unjust State • A badly-ordered state is in chaos. Allowing aggressive soldiers (e. g. , Klingons) or appetitive craftspeople (e. g. , Ferengi) to rule the state is like letting the inmates run the asylum. Such a government makes it difficult for its citizens to live fully human lives. People must perform jobs they’re not suited for, so everyone is personally unhappy. Unwise, shortsighted rulers are not wise, so there is rebellion and conflict within the state. Reasonable people will be persecuted, even executed (as Socrates was).

Why Art Should be Banned from the Just State Identify the arguments Plato gives why art should be banned from the Republic.

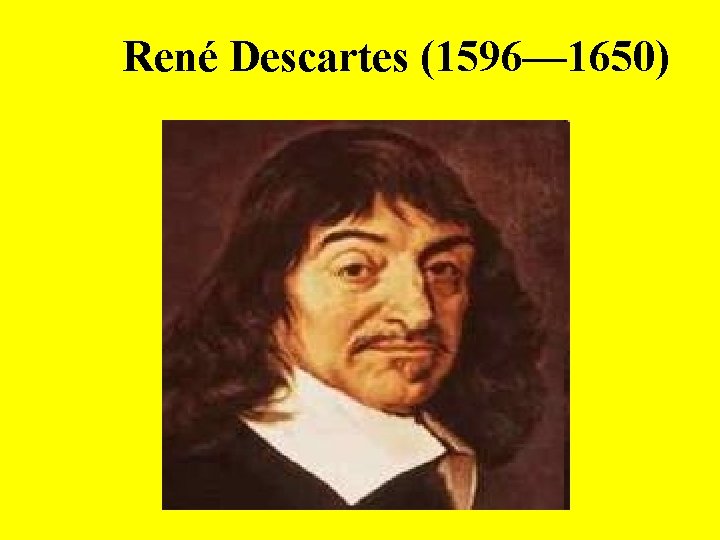

René Descartes (1596— 1650)

Reading • DP Ch 2 "Rene Descartes' Rationalism" • DP Ch 4 "Dualism" ( on Descartes only) • Meditations I, II, VI Online

Group Questions 1. What is Descartes’ ultimate goal in the “Meditations”? 2. The question of whether or not Jupiter has moons is an astronomical matter; it’s not a question of theology or Scripture. So why did the Church find this discovery alarming? The following questions refer to the Meditations:

3. What is Descartes dream argument. What exactly does it prove? 4. What is Descartes’ Evil Genius Argument? How does it go farther than the dream argument in its skepticism? 5. What a priori truth does Descartes find in Meditation II and why is it a priori? 6. What is Descartes argument for the existence of God? 7. In Meditation VI, Descartes finally concludes that he has knowledge of the world external to his mind. Why? What sort of knowledge of the external world does he get? Why was the Church happy with Descartes’

8. What is Descartes' argument of the wax? What does Descartes think it proves? 9. What is Cartesian Dualism?

Outline of the Meditations Meditation I • Methodological (Systematic Doubt) Argument From Illusions Dream Argument Evil Genius Hypothesis

Outline of the Meditations Meditation II • “I think, therefore I am” — cogito ergo sum. • Cartesian Dualism – Mind and Body are distinct substances. • Wax Argument. Notions of Substance and Identity are innate

Meditations III-V • A priori argument that God exists (My idea of perfection had to come from a perfect being) • God is not a deceiver. Therefore Math knowledge is indubitable • Therefore our knowledge of the sensible world is guaranteed at least insofar as our sensations of primary (mathematical) qualities are concerned.

Empiricist Epistemology, Locke, Berkeley and Hume • Empiricism stresses the power of a posteriori reasoning — reasoning from observation or experience — to grasp substantial truths about the world. • When a priori ideas conflict with the a posteriori, the a posteriori wins, according to empiricism. • Empiricism is usually opposed to rationalism - the view that reason rather than sensation or observation is the source of knowledge.

• Empiricists tend to see modern science as the paradigm of knowledge. The empiricist approach is hands-on, down-to-earth. Empiricists urge us to trust our senses, observe the world carefully, perform experiments, and learn from experience. • So, empiricists would say, we should be suspicious of explanations that make reference to nonobservable entities such as gods, souls, immaterial minds, and other metaphysical concepts not verifiable by the senses.

• British Empiricism was a movement in epistemology in the modern period of philosophy. The major figures of British Empiricism are Locke, Berkeley, and Hume. The ancient Greek philosopher Aristotle is usually considered a forerunner of modern empiricism. For example, he criticized Plato’s very non-empirical notion of transcendental forms.

British Empiricism The “British Empiricists” were: 1. John Locke (1632 -1704) 2. George Berkeley (1685 -1753) 3. David Hume (1711 -1776)

John Locke • Blank Slate Nihil in intellectu quod prius non fuerit in sensu. (“There’s nothing in the intellect that wasn’t previously in the senses. ”) • According to Locke, the mind at birth is a tabula rasa (blank slate).

• No ideas are innate. Locke applies Ockham’s Razor to innate ideas: we can explain everything we know without invoking innate ideas (our senses are enough); so innate ideas are unnecessary. • Metaphysical nominalism: only particular things exist (not concepts, abstractions, Forms, etc. ) • Psychological atomism: according to Locke, the ultimate building blocks of knowledge are simple, discrete perceptual units (his “simple ideas”). • “Simple” here means “from a single sense, ” and thus not able to be broken down into smaller constituent parts.

• Three kinds of complex ideas are built from simple ones: -compounds (“red house” = "red" + "house"); - relations (“taller than, ” “loves”) - abstractions which lead us to general ideas, e. g. , “blue”, “dog. ”Abstraction” is the name of a mental process by which general ideas are generated from particular ideas. • “Representative realism” is Locke’s view that we experience objects indirectly through “representations”.

• The mind represents the world, but does not duplicate it. Descartes also held this view. • Representative realism is opposed to naïve realism, the view that the mind literally duplicates or “mirrors” external reality. • Primary qualities are measurable using numbers (e. g. , size, weight). They represent the world as it is “objectively”, the same for everyone. • Secondary qualities result from the interaction of sense data with our sense organs, i. e. , they are “subjective” in the sense that the powers that produce them (corpuscles interacting on our senses) are nothing like the ideas themselves.

The Problem of Substance • Both Descartes and Locke conclude there’s a real substantive world “out there” that has certain qualities (the primary qualities). The primary qualities are qualities of the underlying “substance” (from sub (under) and stance (standing)). • But if Locke is committed to the view that all knowledge comes from the senses, he can’t allow that we know substance, since we have no sensation of substance (we have sensations only of

• the qualities). Thus an essential element of Locke’s empiricist philosophy remains unsupported (and unsupportable) by Locke’s empiricist principles.

George Berkeley held all the following views: • Locke did not apply Ockham’s razor vigorously enough. Berkeley applies Ockham’s razor to Locke’s notion of substance. • Experience is the source of most knowledge (except knowledge of self and knowledge of God). So Berkeley is an empiricist, but with an interesting idealist twist.

• • • All and only perceptions (qualities) are experienced. According to Berkeley, all experience is conscious, or, in other words, mental; we experience only “ideas”. Thus we never have direct experience of things themselves. Thus our experience does not support the view that there are things outside the mind at all. Socalled “material” things are really just clusters of ideas. Thus, there’s no way to distinguish primary and secondary qualities. All qualities are secondary (the object for me). Measurable qualities (so-

called “primary” qualities) are just as “subjective” as color and taste, since all qualities are “in my head”. • Thus, to be is to be perceived (esse est percipi). • But our experiences appear to be consistent with the experience of (supposed) “other people”. Also, things appear to exist continuously; they don’t appear to flash in and out of being depending on whether they’re being perceived. What accounts for this coherence and continuity of experience? • This inter-subjective agreement and apparent continuity of perception is due to the watchful

• attention of God – the great perceiver who never looks away. We can thus derive knowledge of the existence of God from a transcendental argument (God must exist for our experience to be what it is). • Inconsistencies in Berkeley. God is not something that is perceivable but Berkeley is an empiricist and empiricists say we can only have knowledge of what we perceive. • Berkeley also accepts the Cartesian view that we know our own existence, our Self innately. But empiricists aren’t supposed to believe in innate ideas.

David Hume Radical Empiricist Please respond to the following selected question you have been assigned. Create a legible preferably typed document answering the question. The document will be shown to the class.

1. What is Berkeley’s argument that there is no distinction between primary and secondary qualities? 2. Explain Berkeley’s view that physical objects are nothing more than sense data. Give an analysis of a couple objects as fully as you can in terms of sense data. 3. Explain the source of sense data, for Berkeley. How is this different from Locke’s view? How is it similar to Locke’s Evil Genius Hypothesis? 4. Explain how some of Berkeley’s beliefs seem to contradict his empiricism.

David Hume 5. Explain the characteristics of analytic and synthetic statements. How is this distinction used by Hume to dispose of all metaphysical knowledge? 6. Explain Hume’s destruction of the concept of “Self. ”

7. Explain Hume’s and the Positivist’s destruction of the concept of causality. 8. Explain the Positivist’s destruction of the concept of substance. How would the Positivist analyze the statement, “There is a car in the garage? ”

Immanuel Kant • The philosophy of Immanuel Kant (17241804) is sometimes called the “Copernican revolution of philosophy” to emphasize its novelty and huge importance. • Kant synthesized (brought together) rationalism and empiricism. After Kant, the old debate between rationalists and empiricists ended, and epistemology went in a new direction. • After Kant, no discussion of reality or knowledge could take place without awareness of the role of the human mind in constructing reality and knowledge.

Immanuel Kant Summary of Rationalism 1. Don’t trust senses, since they sometimes deceive; and since the “knowledge” they provide is inferior (because it changes). 2. Reason alone can provide knowledge. Math is the paradigm of real knowledge. 3. There are innate ideas, e. g. , Plato’s Forms, or Descartes’ concepts of self, substance, and identity.

4. The self is real and discernable through immediate intellectual intuition (cogito ergo sum). Kant says rationalists are sort of right about (3) and (4) above; wrong about (1) and (2).

Summary of Empiricism 1. Senses are the primary, or only, source of knowledge of world. Psychological atomism. 2. Mathematics and a priori claims deals only with relations of ideas (tautologies); gives no knowledge of world. 3. No innate ideas.

4. Hume — there’s no immediate intellectual intuition of self. The concept of “Self” is not supported by sensations either. 5. Hume — no sensations support the notion of necessary connections between causes and effects, or the notion that the future will resemble the past. Kant thinks empiricism is on the right track re (1), sort of right re (2), wrong re (3), (4), (5).

Transcendental Categories of the Understanding • Kant concludes after a long series of arguments in his great work, The Critique of Pure Reason, that there must be innate structures of the human mind that filter or interpret or structure the input of the senses. • Though innate these structures are not innate in the sense that Plato and Descartes mean.

• These categories include, such things as Space, Time, Substance, Cause and effect, Self, Unity (Identity). • The input of the senses is filtered through these structures in such a way that we must perceive the world in terms of substance, cause and effect, etc. (If we have rose colored glasses on, we must perceive the world as rose colored. ) • We can never know the world as it is in itself, without being filtered through the categories. The world as it really is, Kant calls the noumenal world.

• We can only know the world as we perceive it (through the filters). Kant calls the world as perceived, the phenomenal world. • Both the senses and the mind (reason) contribute to knowledge. “Thoughts without content (sense experience) are empty, intuitions (sense experience) without concepts (categories of understanding) are blind. ”

• Kant’s lasting influence: Philosophy was indelibly changed by Kant’s powerful idea that the mind is not a passive receptacle of sense data per the empiricists, but actively shapes our experience of the world. Any account of knowledge and perception must include the fact that our minds shape what we experience.

Rationalist epistemology

Rationalist epistemology Sum ergo edo

Sum ergo edo Leibniz rationalism

Leibniz rationalism Example of rationalism

Example of rationalism Rationalism example

Rationalism example Rationalist hero

Rationalist hero Rationalism vs empiricism

Rationalism vs empiricism Transcendental idealism kant

Transcendental idealism kant Eb = p x a x t

Eb = p x a x t What is epistemology in research

What is epistemology in research Ontological vs epistemological

Ontological vs epistemological Ontology epistemology axiology

Ontology epistemology axiology Epistemology and pedagogy

Epistemology and pedagogy Characteristics of skimming reading

Characteristics of skimming reading Theodolite is used to measure

Theodolite is used to measure Vernier caliper msr and vsr

Vernier caliper msr and vsr How to write keratometry readings

How to write keratometry readings 312زبان عشق

312زبان عشق Confined space gas limits

Confined space gas limits Rad 57 co readings

Rad 57 co readings Normal blood gas levels

Normal blood gas levels Reading a graduated cylinder

Reading a graduated cylinder Responsive readings for christmas

Responsive readings for christmas Responsive prayer of thanksgiving

Responsive prayer of thanksgiving Njcu map

Njcu map Purpose of ammeter

Purpose of ammeter Normal ecg readings

Normal ecg readings Interpretivist epistemology

Interpretivist epistemology Ontological argument for god

Ontological argument for god Realism philosophy

Realism philosophy Ontology epistemology methodology

Ontology epistemology methodology Aristotle epistemology

Aristotle epistemology Nietzsche existentialism

Nietzsche existentialism Genetic epistemology definition

Genetic epistemology definition Ontology in qualitative research

Ontology in qualitative research Sara potkonjak

Sara potkonjak Kant epistemology

Kant epistemology Epistemology positivism

Epistemology positivism Medo-lat epistemology

Medo-lat epistemology Tesa antitesa sintesa

Tesa antitesa sintesa Buddhist epistemology

Buddhist epistemology Epistemology

Epistemology Pierre de coubertin and plato

Pierre de coubertin and plato Philosophical contribution of socrates

Philosophical contribution of socrates Difference between aristotle and plato

Difference between aristotle and plato Plato vs aristotle

Plato vs aristotle Aristotelian logic

Aristotelian logic Functionalism vs structuralism

Functionalism vs structuralism Socrates plato and aristotle worksheet answer key

Socrates plato and aristotle worksheet answer key Was aristotle a philosopher

Was aristotle a philosopher Cogito2

Cogito2 Philisophical zombies

Philisophical zombies Descartes cosmological argument

Descartes cosmological argument Diyalektik dusunce

Diyalektik dusunce Descartes vortex theory

Descartes vortex theory Tres sustancias de descartes

Tres sustancias de descartes Ren descartes

Ren descartes Nicolas synnott

Nicolas synnott Descartes frans hals

Descartes frans hals Empirismo y racionalismo

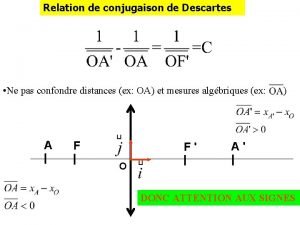

Empirismo y racionalismo Conjugaison de descartes

Conjugaison de descartes Philosophy about dreams

Philosophy about dreams Rene descartes human nature

Rene descartes human nature Descartes evil genius

Descartes evil genius Regla de los signos de descartes

Regla de los signos de descartes Rene descartes first meditation summary

Rene descartes first meditation summary Descartes rule of signs

Descartes rule of signs