Query Processing and Optimization n n Architecture of

- Slides: 55

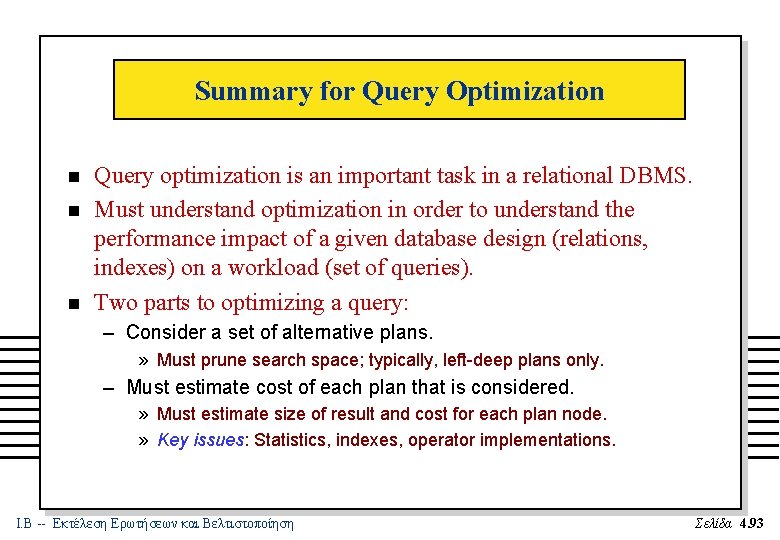

Query Processing and Optimization n n Architecture of the Query Processor in a DBMS Query Processing Implementation of Relational Operators (join, select, project, aggregates, etc. ) – Use of Indices – Buffering Query Optimization – Plans – Nested Queries Ι. Β -- Εκτέλεση Ερωτήσεων και Βελτιστοποίηση Σελίδα 4. 41

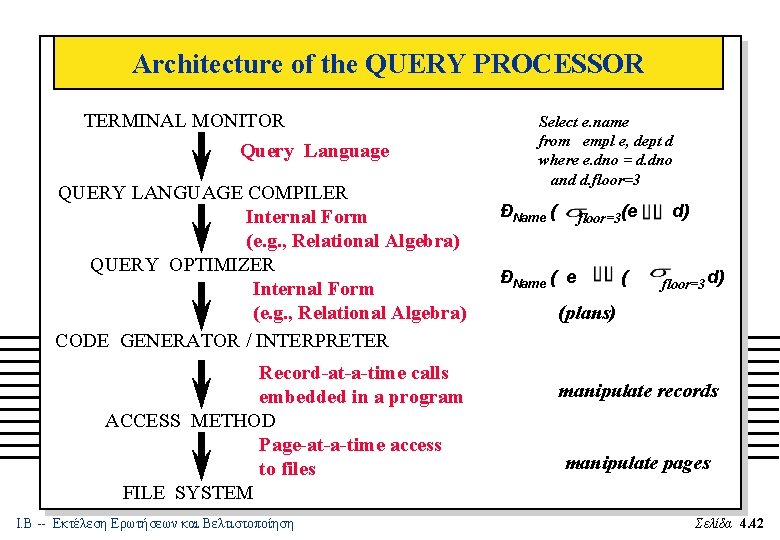

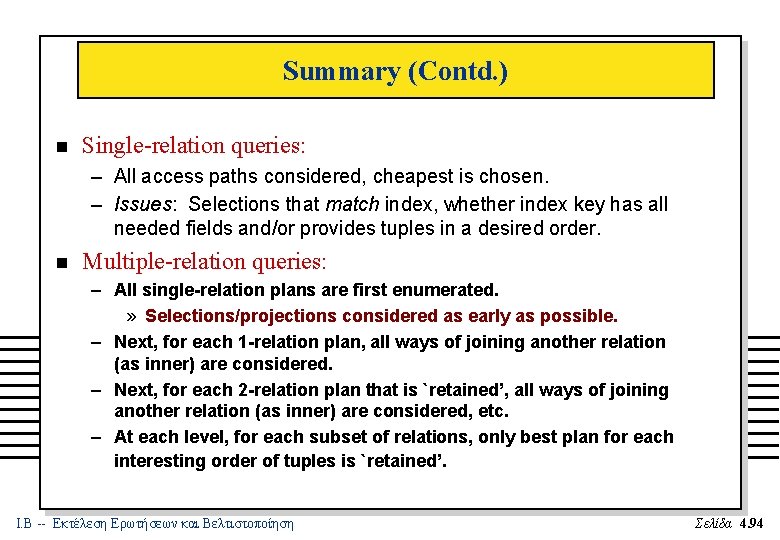

Architecture of the QUERY PROCESSOR TERMINAL MONITOR Query Language QUERY LANGUAGE COMPILER Internal Form (e. g. , Relational Algebra) QUERY OPTIMIZER Internal Form (e. g. , Relational Algebra) CODE GENERATOR / INTERPRETER Record-at-a-time calls embedded in a program ACCESS METHOD Page-at-a-time access to files FILE SYSTEM Ι. Β -- Εκτέλεση Ερωτήσεων και Βελτιστοποίηση Select e. name from empl e, dept d where e. dno = d. dno and d. floor=3 ÐName ( floor=3(e ÐName ( d) floor=3 d) (plans) manipulate records manipulate pages Σελίδα 4. 42

Query Processing in a DBMS n n The Query Language Compiler translates the query into an internal form, usually a relational algebra expression The Query Optimizer examines all the equivalent algebraic expressions (plans) and chooses the one that is estimated as cheapest – Uses estimates of sizes, usage and contents of the relations (kept in catalogs and updated dynamically) – Uses the knowledge of the Cost for relational database operations (how the joins are implemented, etc. ) Ι. Β -- Εκτέλεση Ερωτήσεων και Βελτιστοποίηση Σελίδα 4. 43

Query Processing in a DBMS -- (b) n n The Code Generator implements the access plan generated by the Optimizer The Access Methods support commands to access records of a file (one at a time). FUNCTIONS of an access method are: – – Record Layout on Pages Field Layout in Records Data Compression Indexing Records by Field Values Ι. Β -- Εκτέλεση Ερωτήσεων και Βελτιστοποίηση Σελίδα 4. 44

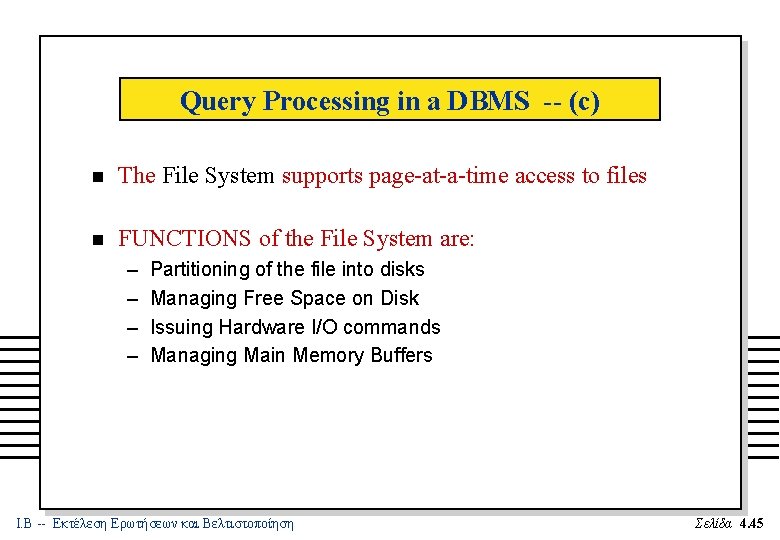

Query Processing in a DBMS -- (c) n The File System supports page-at-a-time access to files n FUNCTIONS of the File System are: – – Partitioning of the file into disks Managing Free Space on Disk Issuing Hardware I/O commands Managing Main Memory Buffers Ι. Β -- Εκτέλεση Ερωτήσεων και Βελτιστοποίηση Σελίδα 4. 45

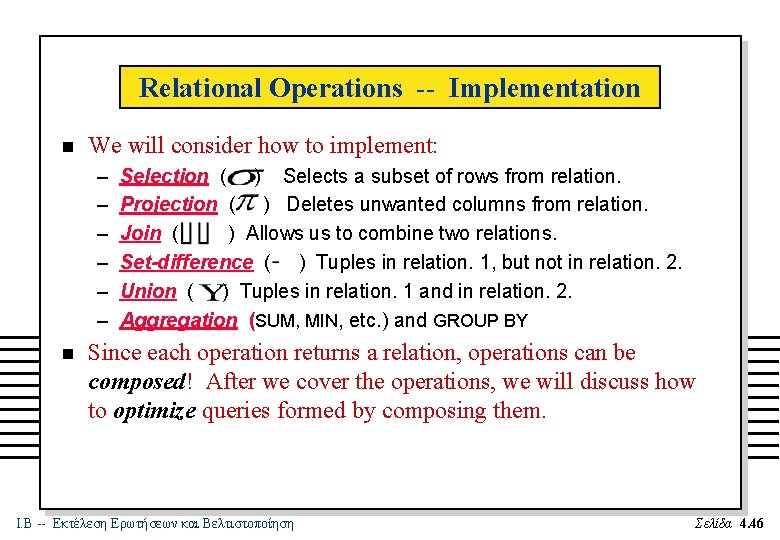

Relational Operations -- Implementation n We will consider how to implement: – – – n Selection ( ) Selects a subset of rows from relation. Projection ( ) Deletes unwanted columns from relation. Join ( ) Allows us to combine two relations. Set-difference ( ) Tuples in relation. 1, but not in relation. 2. Union ( ) Tuples in relation. 1 and in relation. 2. Aggregation (SUM, MIN, etc. ) and GROUP BY Since each operation returns a relation, operations can be composed! After we cover the operations, we will discuss how to optimize queries formed by composing them. Ι. Β -- Εκτέλεση Ερωτήσεων και Βελτιστοποίηση Σελίδα 4. 46

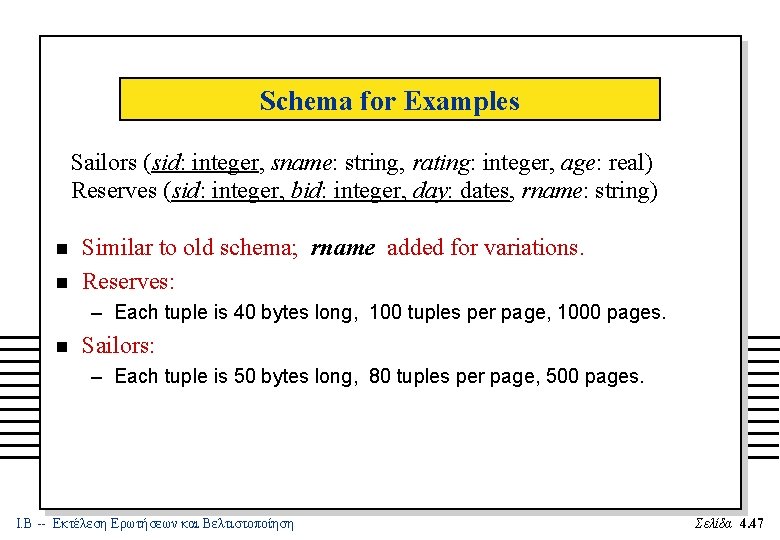

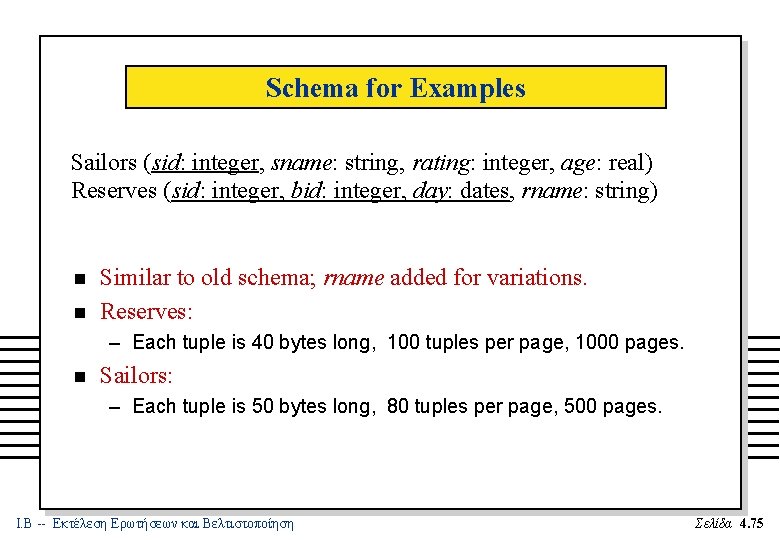

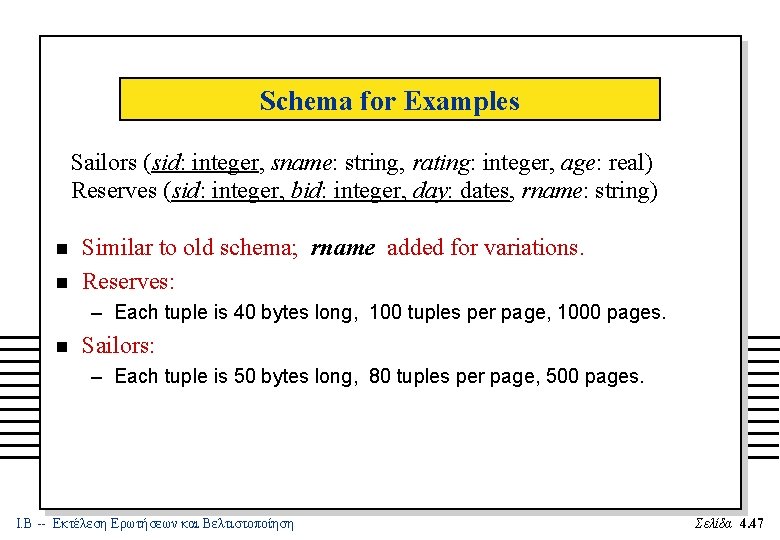

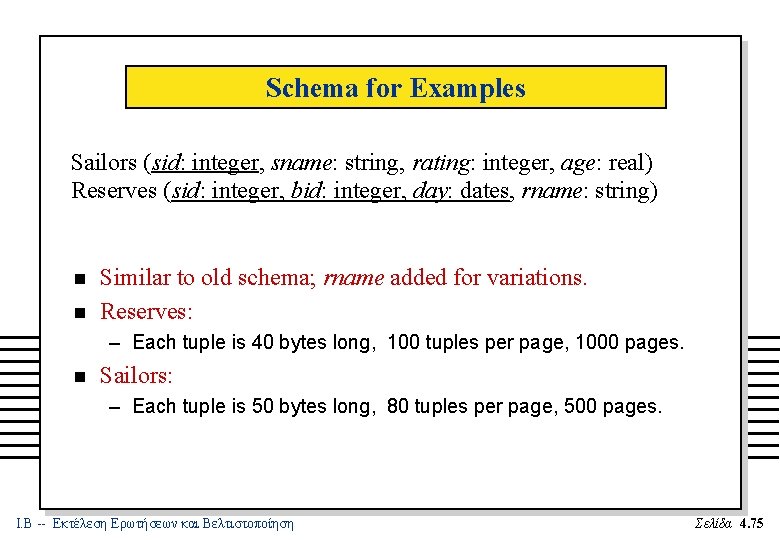

Schema for Examples Sailors (sid: integer, sname: string, rating: integer, age: real) Reserves (sid: integer, bid: integer, day: dates, rname: string) n n Similar to old schema; rname added for variations. Reserves: – Each tuple is 40 bytes long, 100 tuples per page, 1000 pages. n Sailors: – Each tuple is 50 bytes long, 80 tuples per page, 500 pages. Ι. Β -- Εκτέλεση Ερωτήσεων και Βελτιστοποίηση Σελίδα 4. 47

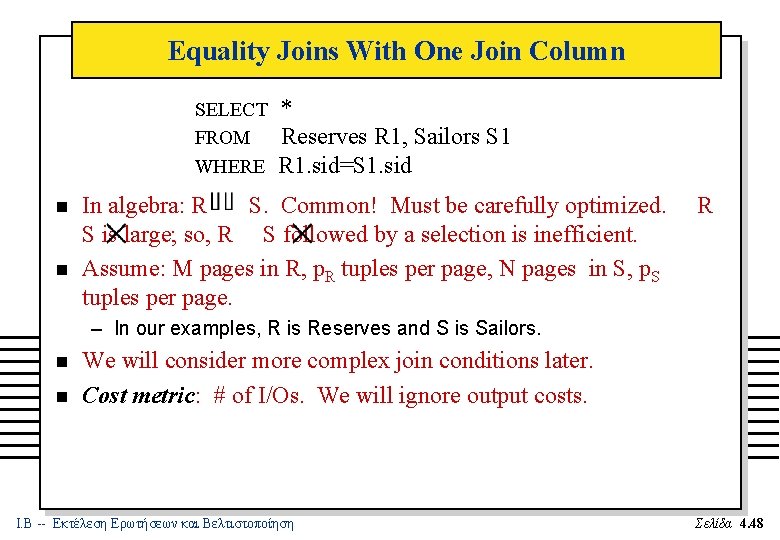

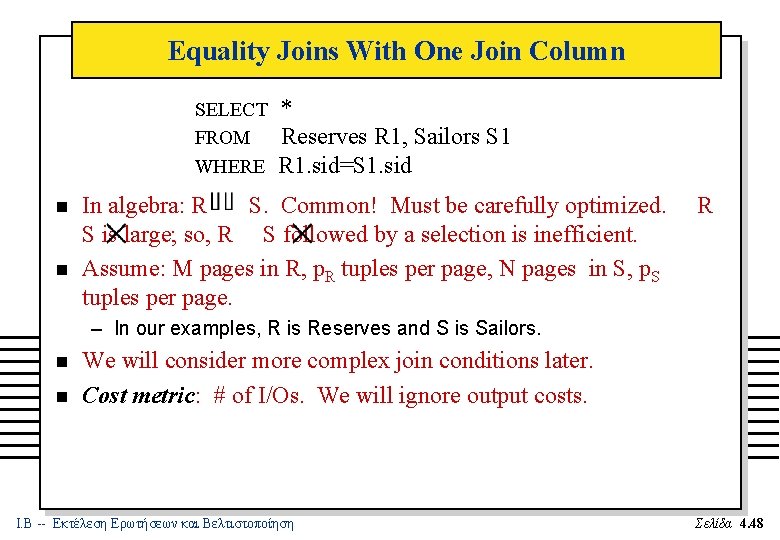

Equality Joins With One Join Column SELECT FROM WHERE n n * Reserves R 1, Sailors S 1 R 1. sid=S 1. sid In algebra: R S. Common! Must be carefully optimized. S is large; so, R S followed by a selection is inefficient. Assume: M pages in R, p. R tuples per page, N pages in S, p. S tuples per page. R – In our examples, R is Reserves and S is Sailors. n n We will consider more complex join conditions later. Cost metric: # of I/Os. We will ignore output costs. Ι. Β -- Εκτέλεση Ερωτήσεων και Βελτιστοποίηση Σελίδα 4. 48

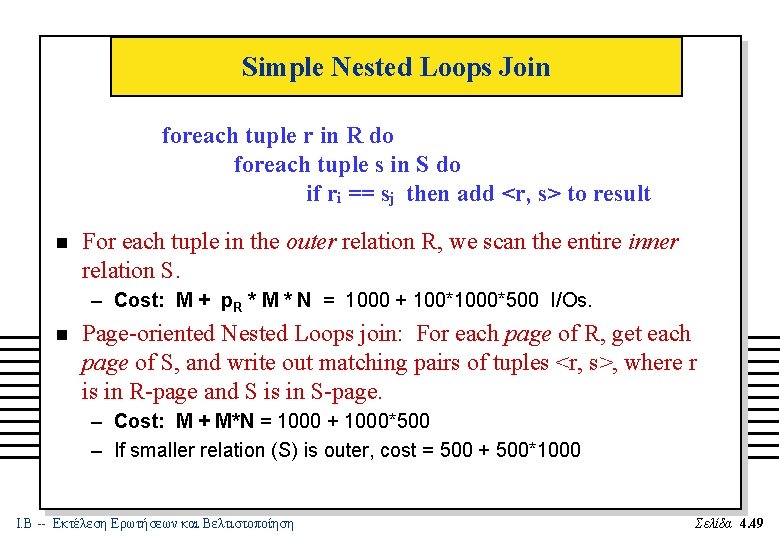

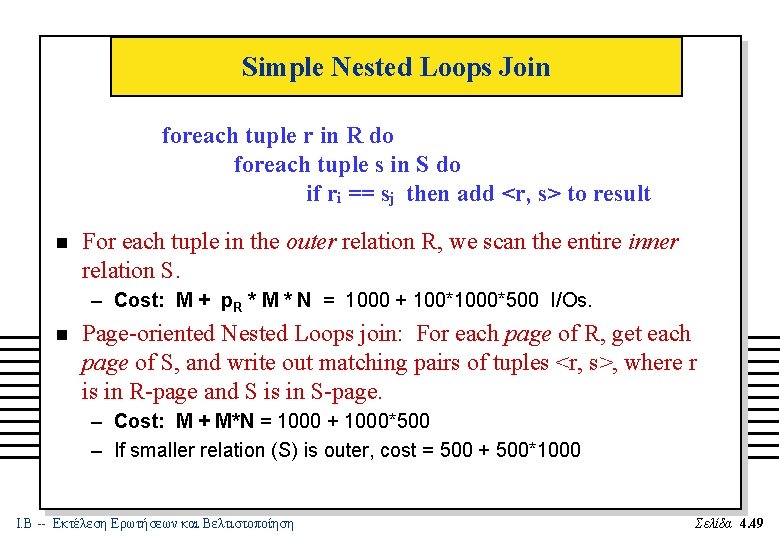

Simple Nested Loops Join foreach tuple r in R do foreach tuple s in S do if ri == sj then add <r, s> to result n For each tuple in the outer relation R, we scan the entire inner relation S. – Cost: M + p. R * M * N = 1000 + 100*1000*500 I/Os. n Page-oriented Nested Loops join: For each page of R, get each page of S, and write out matching pairs of tuples <r, s>, where r is in R-page and S is in S-page. – Cost: M + M*N = 1000 + 1000*500 – If smaller relation (S) is outer, cost = 500 + 500*1000 Ι. Β -- Εκτέλεση Ερωτήσεων και Βελτιστοποίηση Σελίδα 4. 49

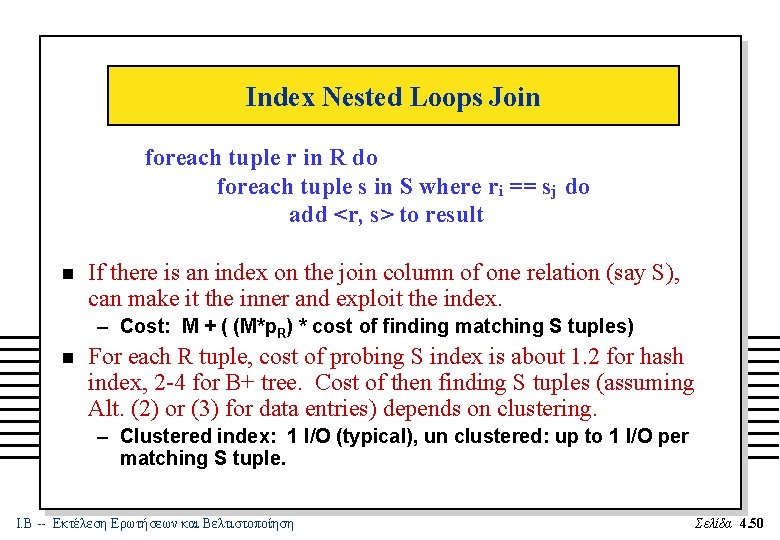

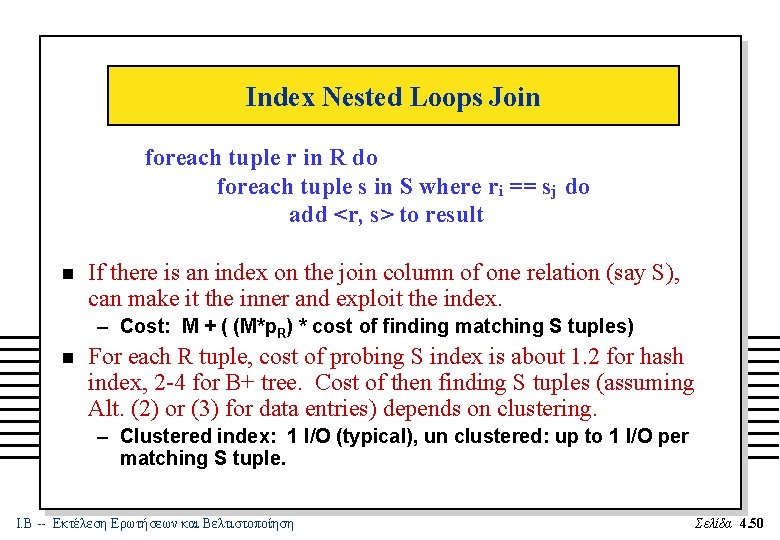

Index Nested Loops Join foreach tuple r in R do foreach tuple s in S where ri == sj do add <r, s> to result n If there is an index on the join column of one relation (say S), can make it the inner and exploit the index. – Cost: M + ( (M*p. R) * cost of finding matching S tuples) n For each R tuple, cost of probing S index is about 1. 2 for hash index, 2 -4 for B+ tree. Cost of then finding S tuples (assuming Alt. (2) or (3) for data entries) depends on clustering. – Clustered index: 1 I/O (typical), un clustered: up to 1 I/O per matching S tuple. Ι. Β -- Εκτέλεση Ερωτήσεων και Βελτιστοποίηση Σελίδα 4. 50

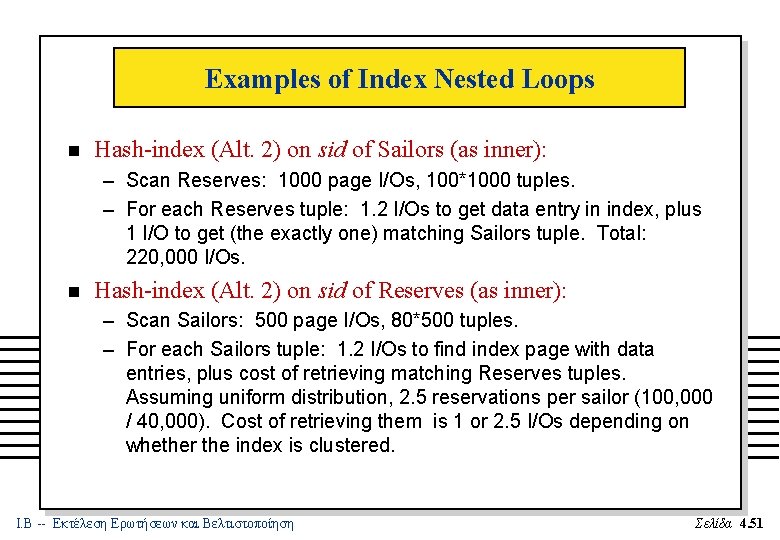

Examples of Index Nested Loops n Hash-index (Alt. 2) on sid of Sailors (as inner): – Scan Reserves: 1000 page I/Os, 100*1000 tuples. – For each Reserves tuple: 1. 2 I/Os to get data entry in index, plus 1 I/O to get (the exactly one) matching Sailors tuple. Total: 220, 000 I/Os. n Hash-index (Alt. 2) on sid of Reserves (as inner): – Scan Sailors: 500 page I/Os, 80*500 tuples. – For each Sailors tuple: 1. 2 I/Os to find index page with data entries, plus cost of retrieving matching Reserves tuples. Assuming uniform distribution, 2. 5 reservations per sailor (100, 000 / 40, 000). Cost of retrieving them is 1 or 2. 5 I/Os depending on whether the index is clustered. Ι. Β -- Εκτέλεση Ερωτήσεων και Βελτιστοποίηση Σελίδα 4. 51

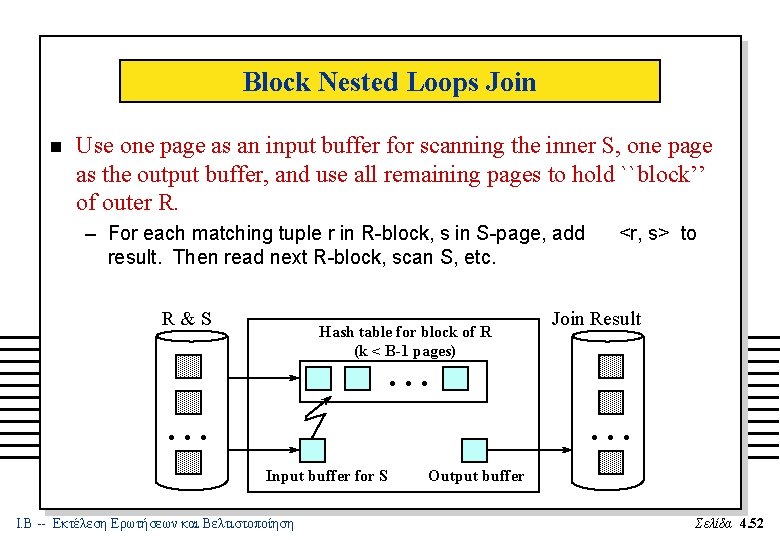

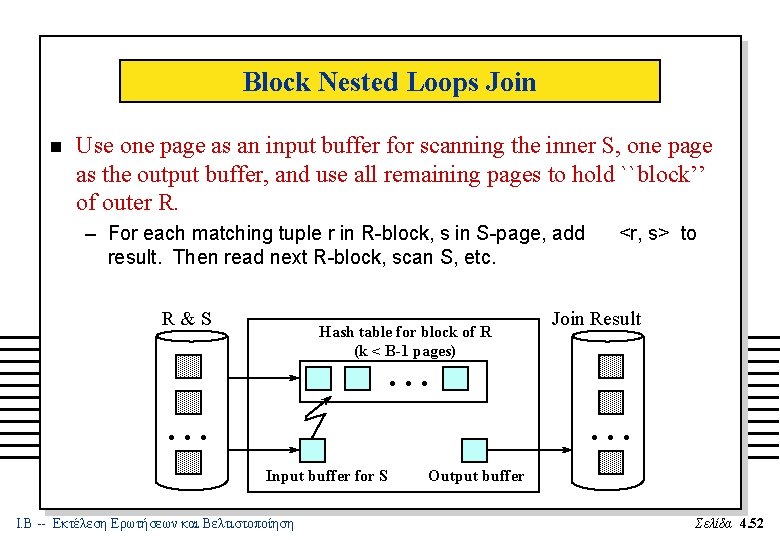

Block Nested Loops Join n Use one page as an input buffer for scanning the inner S, one page as the output buffer, and use all remaining pages to hold ``block’’ of outer R. – For each matching tuple r in R-block, s in S-page, add result. Then read next R-block, scan S, etc. R&S Hash table for block of R (k < B-1 pages) <r, s> to Join Result . . Input buffer for S Ι. Β -- Εκτέλεση Ερωτήσεων και Βελτιστοποίηση Output buffer Σελίδα 4. 52

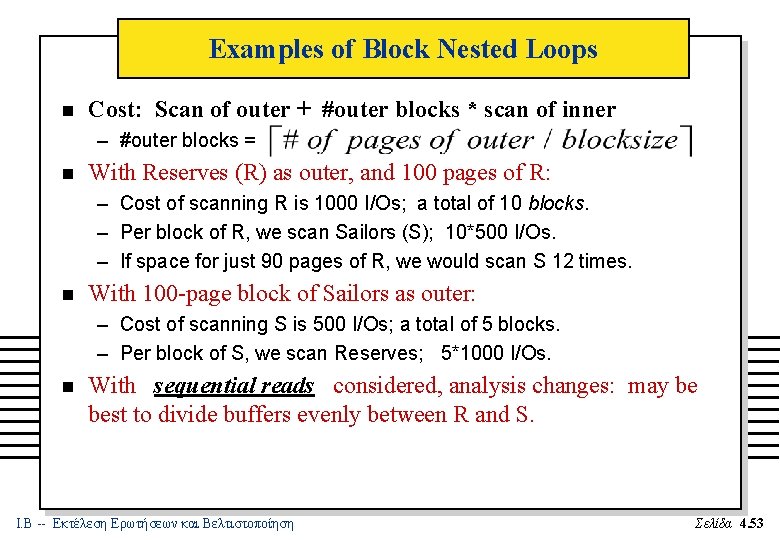

Examples of Block Nested Loops n Cost: Scan of outer + #outer blocks * scan of inner – #outer blocks = n With Reserves (R) as outer, and 100 pages of R: – Cost of scanning R is 1000 I/Os; a total of 10 blocks. – Per block of R, we scan Sailors (S); 10*500 I/Os. – If space for just 90 pages of R, we would scan S 12 times. n With 100 -page block of Sailors as outer: – Cost of scanning S is 500 I/Os; a total of 5 blocks. – Per block of S, we scan Reserves; 5*1000 I/Os. n With sequential reads considered, analysis changes: may be best to divide buffers evenly between R and S. Ι. Β -- Εκτέλεση Ερωτήσεων και Βελτιστοποίηση Σελίδα 4. 53

Sort-Merge Join (R n i=j S) Sort R and S on the join column, then scan them to do a ``merge’’ (on join col. ), and output result tuples. – Advance scan of R until current R-tuple >= current S tuple, then advance scan of S until current S-tuple >= current R tuple; do this until current R tuple = current S tuple. – At this point, all R tuples with same value in Ri (current R group) and all S tuples with same value in Sj (current S group) match; output <r, s> for all pairs of such tuples. – Then resume scanning R and S. n R is scanned once; each S group is scanned once per matching R tuple. (Multiple scans of an S group are likely to find needed pages in buffer. ) Ι. Β -- Εκτέλεση Ερωτήσεων και Βελτιστοποίηση Σελίδα 4. 54

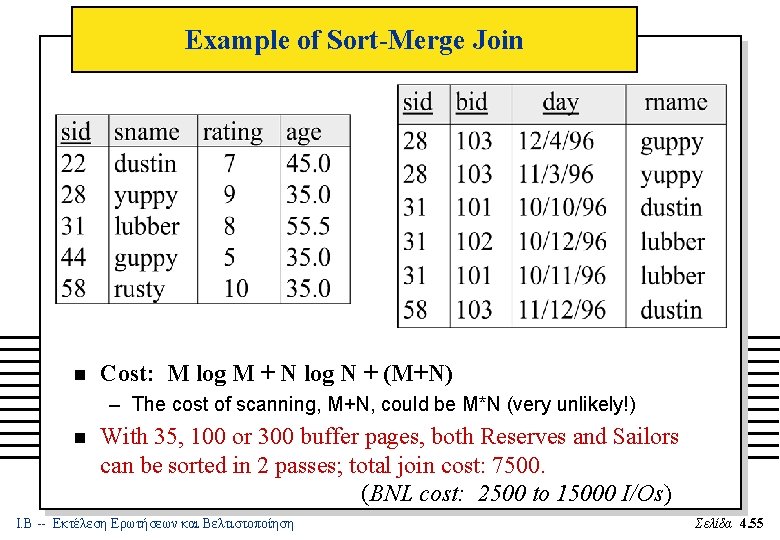

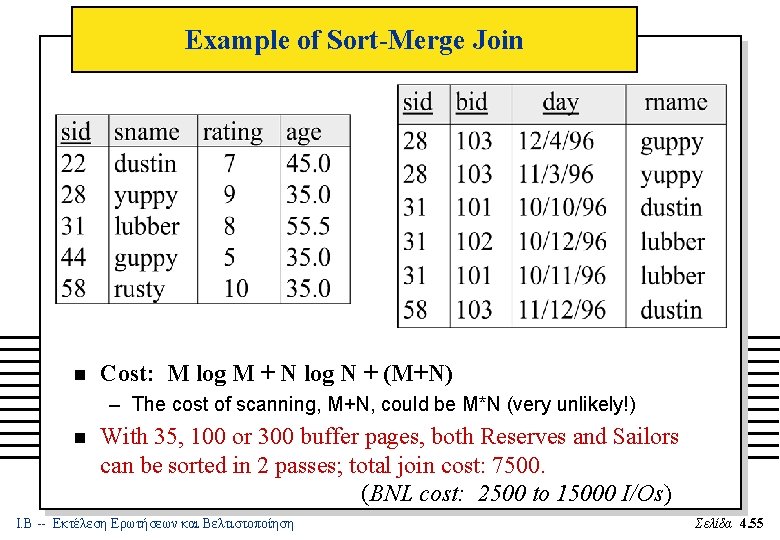

Example of Sort-Merge Join n Cost: M log M + N log N + (M+N) – The cost of scanning, M+N, could be M*N (very unlikely!) n With 35, 100 or 300 buffer pages, both Reserves and Sailors can be sorted in 2 passes; total join cost: 7500. (BNL cost: 2500 to 15000 I/Os) Ι. Β -- Εκτέλεση Ερωτήσεων και Βελτιστοποίηση Σελίδα 4. 55

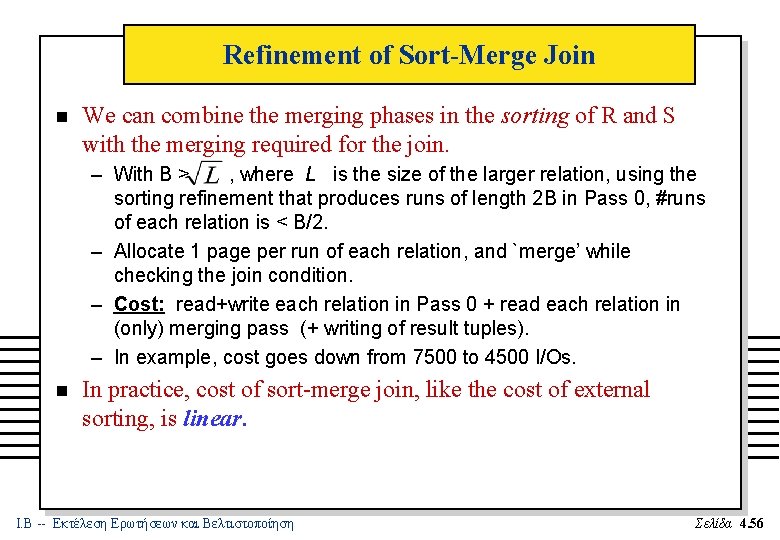

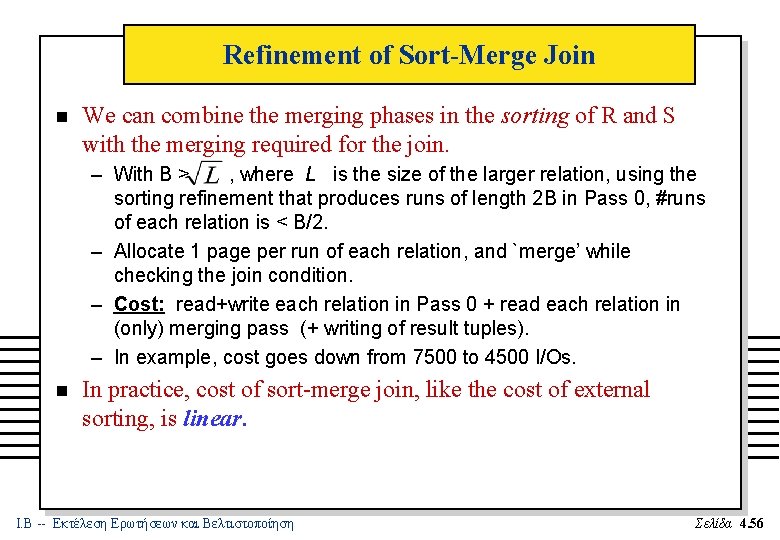

Refinement of Sort-Merge Join n We can combine the merging phases in the sorting of R and S with the merging required for the join. – With B > , where L is the size of the larger relation, using the sorting refinement that produces runs of length 2 B in Pass 0, #runs of each relation is < B/2. – Allocate 1 page per run of each relation, and `merge’ while checking the join condition. – Cost: read+write each relation in Pass 0 + read each relation in (only) merging pass (+ writing of result tuples). – In example, cost goes down from 7500 to 4500 I/Os. n In practice, cost of sort-merge join, like the cost of external sorting, is linear. Ι. Β -- Εκτέλεση Ερωτήσεων και Βελτιστοποίηση Σελίδα 4. 56

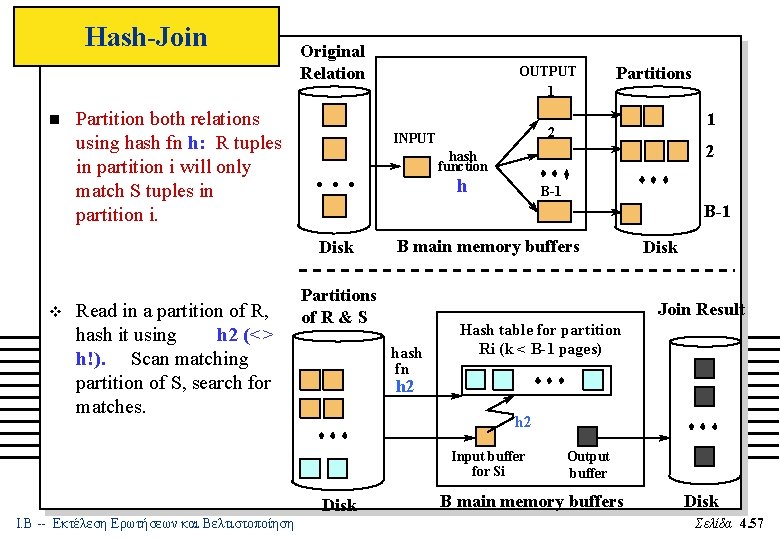

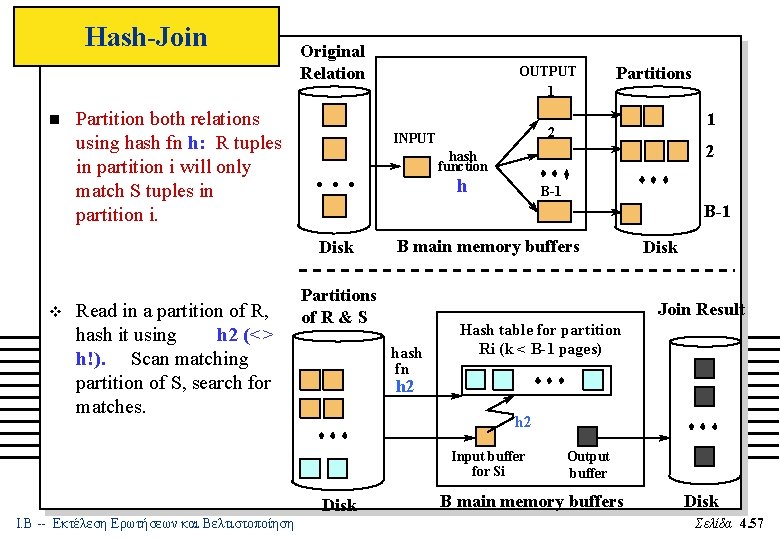

Hash-Join n Partition both relations using hash fn h: R tuples in partition i will only match S tuples in partition i. Original Relation Read in a partition of R, hash it using h 2 (<> h!). Scan matching partition of S, search for matches. 1 2 hash function . . . h B-1 B main memory buffers Partitions of R & S Disk Join Result hash fn Hash table for partition Ri (k < B-1 pages) h 2 Input buffer for Si Disk Ι. Β -- Εκτέλεση Ερωτήσεων και Βελτιστοποίηση Partitions 2 INPUT Disk v OUTPUT 1 Output buffer B main memory buffers Disk Σελίδα 4. 57

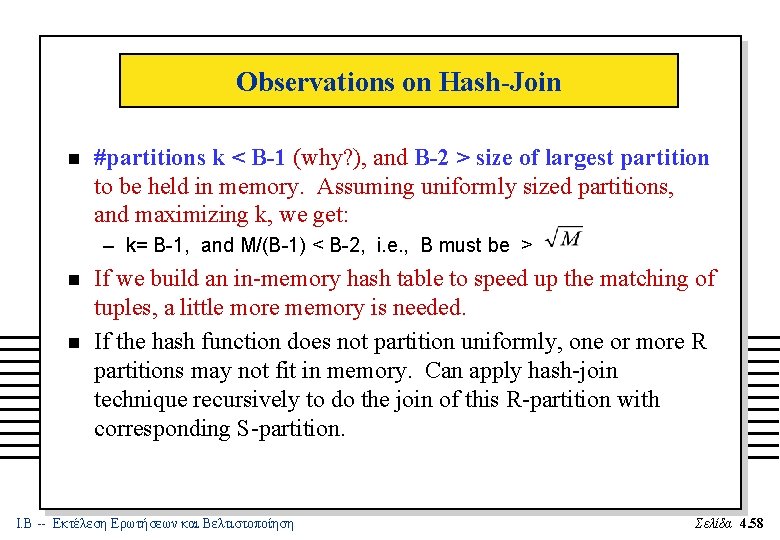

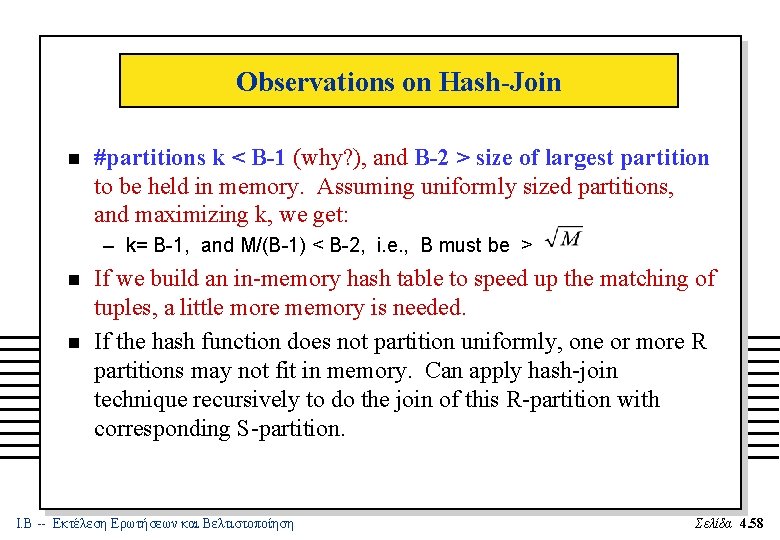

Observations on Hash-Join n #partitions k < B-1 (why? ), and B-2 > size of largest partition to be held in memory. Assuming uniformly sized partitions, and maximizing k, we get: – k= B-1, and M/(B-1) < B-2, i. e. , B must be > n n If we build an in-memory hash table to speed up the matching of tuples, a little more memory is needed. If the hash function does not partition uniformly, one or more R partitions may not fit in memory. Can apply hash-join technique recursively to do the join of this R-partition with corresponding S-partition. Ι. Β -- Εκτέλεση Ερωτήσεων και Βελτιστοποίηση Σελίδα 4. 58

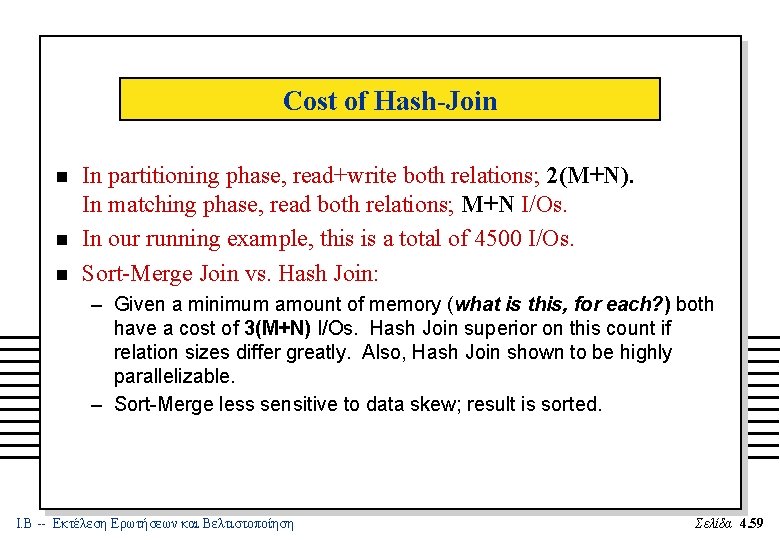

Cost of Hash-Join n In partitioning phase, read+write both relations; 2(M+N). In matching phase, read both relations; M+N I/Os. In our running example, this is a total of 4500 I/Os. Sort-Merge Join vs. Hash Join: – Given a minimum amount of memory (what is this, for each? ) both have a cost of 3(M+N) I/Os. Hash Join superior on this count if relation sizes differ greatly. Also, Hash Join shown to be highly parallelizable. – Sort-Merge less sensitive to data skew; result is sorted. Ι. Β -- Εκτέλεση Ερωτήσεων και Βελτιστοποίηση Σελίδα 4. 59

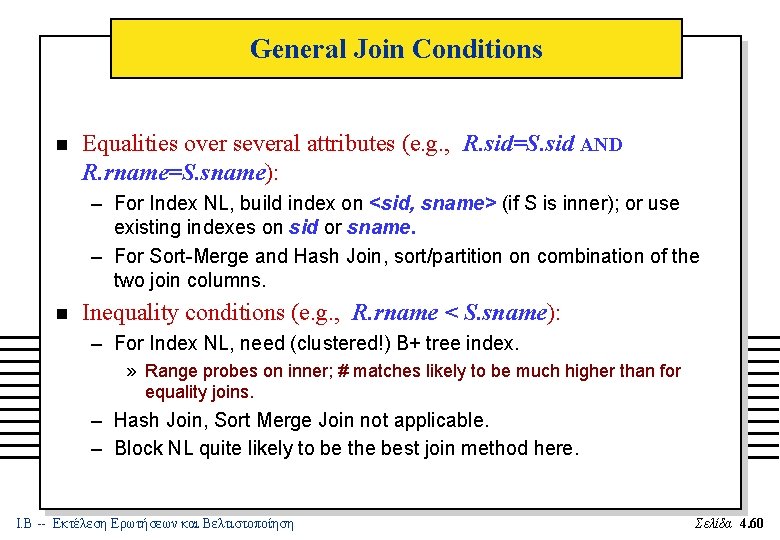

General Join Conditions n Equalities over several attributes (e. g. , R. sid=S. sid AND R. rname=S. sname): – For Index NL, build index on <sid, sname> (if S is inner); or use existing indexes on sid or sname. – For Sort-Merge and Hash Join, sort/partition on combination of the two join columns. n Inequality conditions (e. g. , R. rname < S. sname): – For Index NL, need (clustered!) B+ tree index. » Range probes on inner; # matches likely to be much higher than for equality joins. – Hash Join, Sort Merge Join not applicable. – Block NL quite likely to be the best join method here. Ι. Β -- Εκτέλεση Ερωτήσεων και Βελτιστοποίηση Σελίδα 4. 60

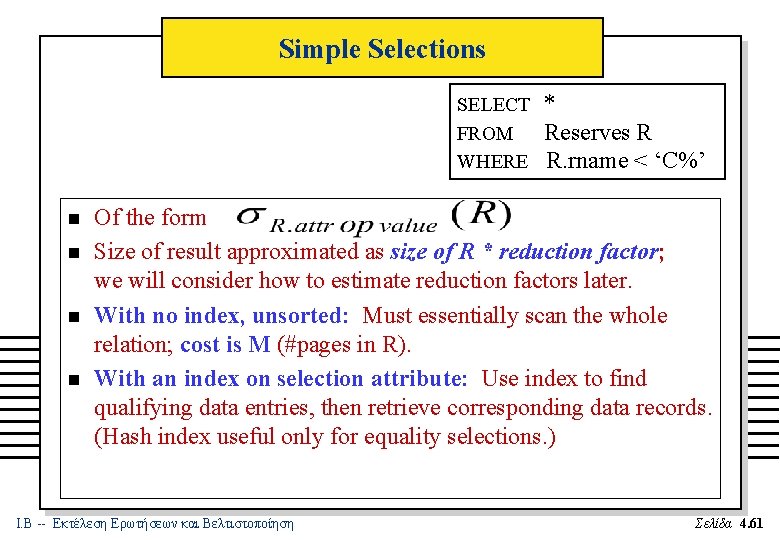

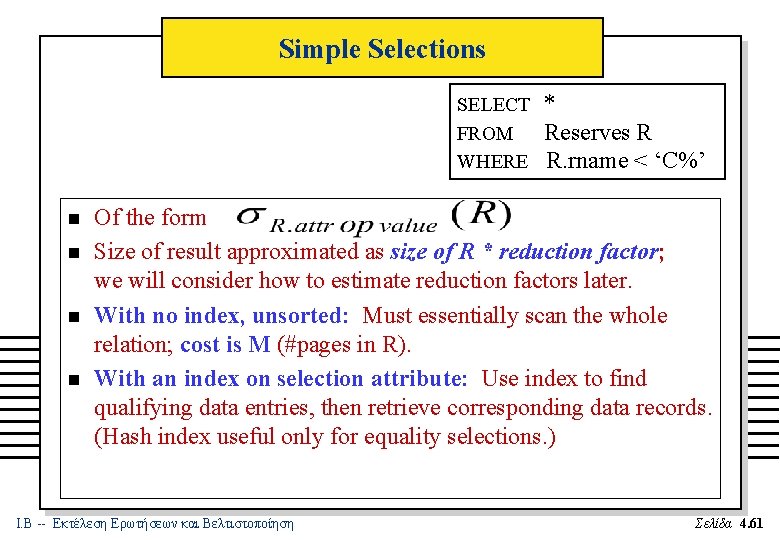

Simple Selections SELECT FROM WHERE n n * Reserves R R. rname < ‘C%’ Of the form Size of result approximated as size of R * reduction factor; we will consider how to estimate reduction factors later. With no index, unsorted: Must essentially scan the whole relation; cost is M (#pages in R). With an index on selection attribute: Use index to find qualifying data entries, then retrieve corresponding data records. (Hash index useful only for equality selections. ) Ι. Β -- Εκτέλεση Ερωτήσεων και Βελτιστοποίηση Σελίδα 4. 61

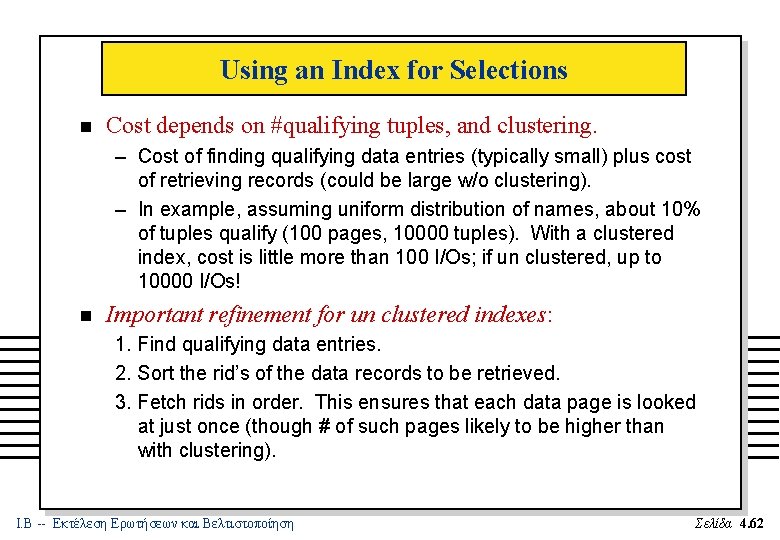

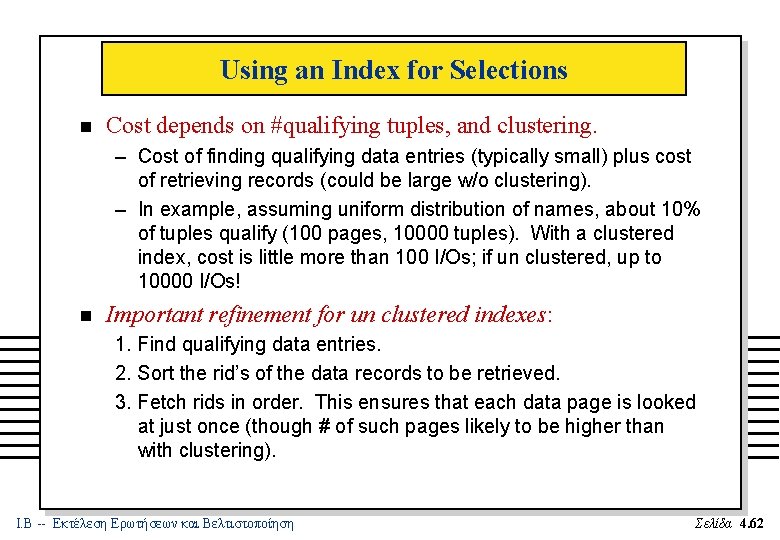

Using an Index for Selections n Cost depends on #qualifying tuples, and clustering. – Cost of finding qualifying data entries (typically small) plus cost of retrieving records (could be large w/o clustering). – In example, assuming uniform distribution of names, about 10% of tuples qualify (100 pages, 10000 tuples). With a clustered index, cost is little more than 100 I/Os; if un clustered, up to 10000 I/Os! n Important refinement for un clustered indexes: 1. Find qualifying data entries. 2. Sort the rid’s of the data records to be retrieved. 3. Fetch rids in order. This ensures that each data page is looked at just once (though # of such pages likely to be higher than with clustering). Ι. Β -- Εκτέλεση Ερωτήσεων και Βελτιστοποίηση Σελίδα 4. 62

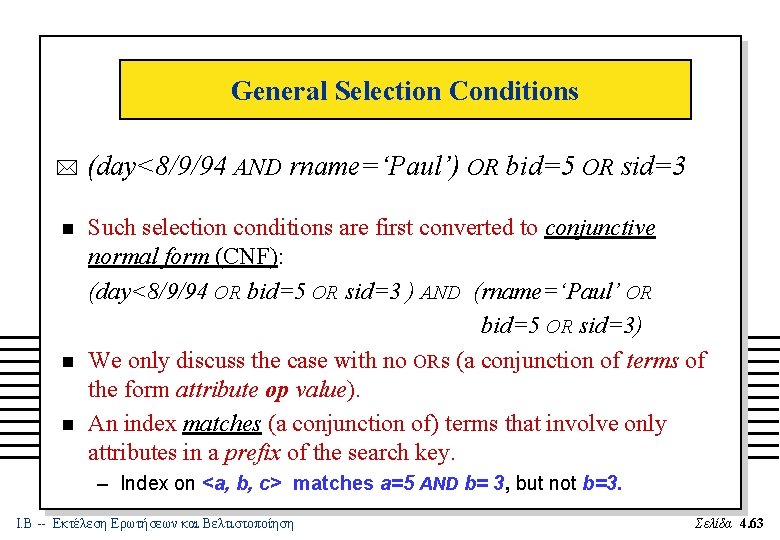

General Selection Conditions * n n n (day<8/9/94 AND rname=‘Paul’) OR bid=5 OR sid=3 Such selection conditions are first converted to conjunctive normal form (CNF): (day<8/9/94 OR bid=5 OR sid=3 ) AND (rname=‘Paul’ OR bid=5 OR sid=3) We only discuss the case with no ORs (a conjunction of terms of the form attribute op value). An index matches (a conjunction of) terms that involve only attributes in a prefix of the search key. – Index on <a, b, c> matches a=5 AND b= 3, but not b=3. Ι. Β -- Εκτέλεση Ερωτήσεων και Βελτιστοποίηση Σελίδα 4. 63

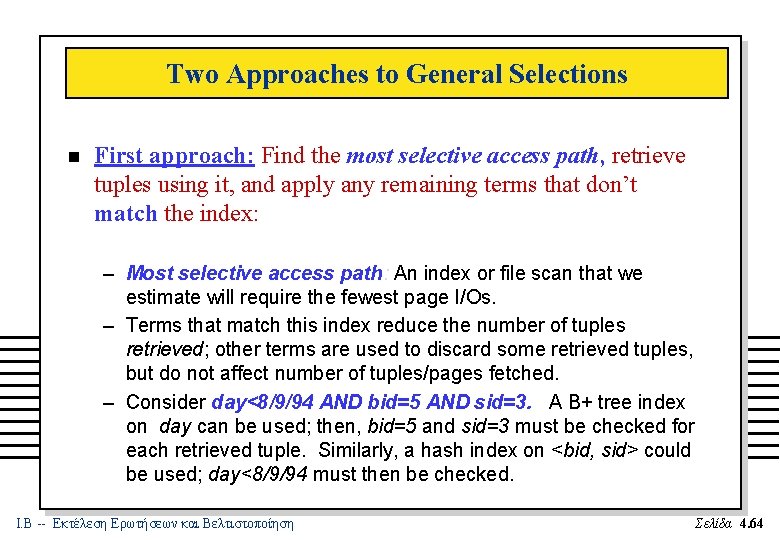

Two Approaches to General Selections n First approach: Find the most selective access path, retrieve tuples using it, and apply any remaining terms that don’t match the index: – Most selective access path: An index or file scan that we estimate will require the fewest page I/Os. – Terms that match this index reduce the number of tuples retrieved; other terms are used to discard some retrieved tuples, but do not affect number of tuples/pages fetched. – Consider day<8/9/94 AND bid=5 AND sid=3. A B+ tree index on day can be used; then, bid=5 and sid=3 must be checked for each retrieved tuple. Similarly, a hash index on <bid, sid> could be used; day<8/9/94 must then be checked. Ι. Β -- Εκτέλεση Ερωτήσεων και Βελτιστοποίηση Σελίδα 4. 64

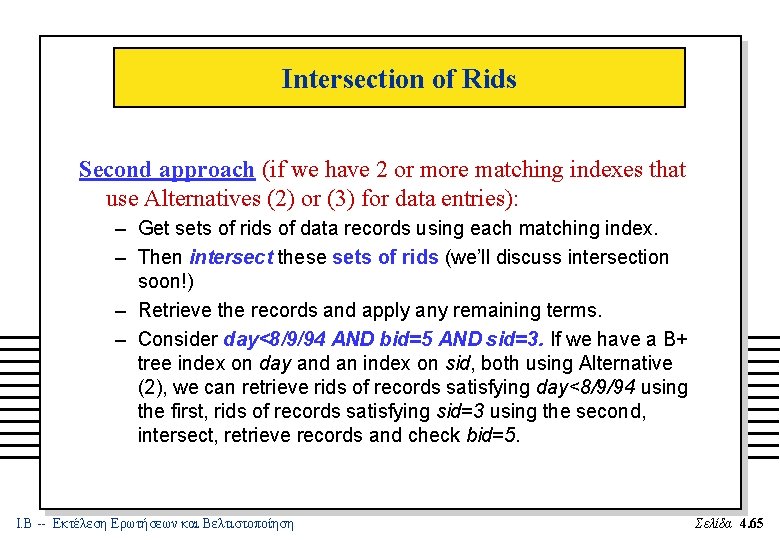

Intersection of Rids Second approach (if we have 2 or more matching indexes that use Alternatives (2) or (3) for data entries): – Get sets of rids of data records using each matching index. – Then intersect these sets of rids (we’ll discuss intersection soon!) – Retrieve the records and apply any remaining terms. – Consider day<8/9/94 AND bid=5 AND sid=3. If we have a B+ tree index on day and an index on sid, both using Alternative (2), we can retrieve rids of records satisfying day<8/9/94 using the first, rids of records satisfying sid=3 using the second, intersect, retrieve records and check bid=5. Ι. Β -- Εκτέλεση Ερωτήσεων και Βελτιστοποίηση Σελίδα 4. 65

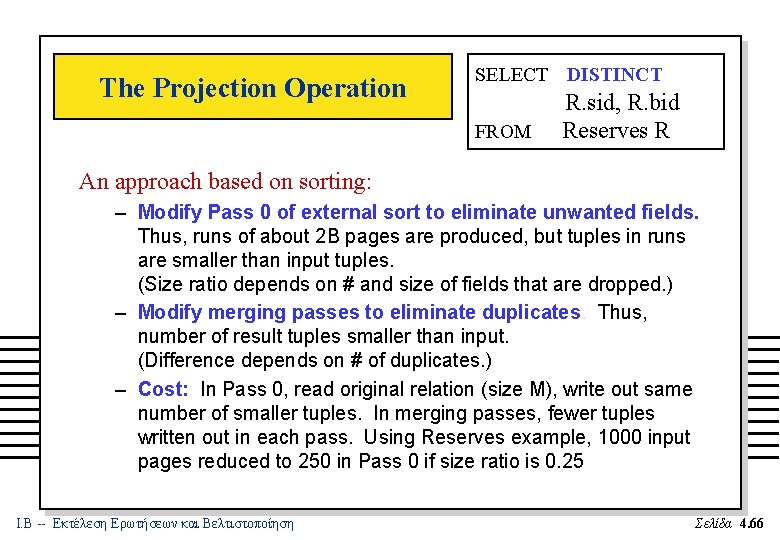

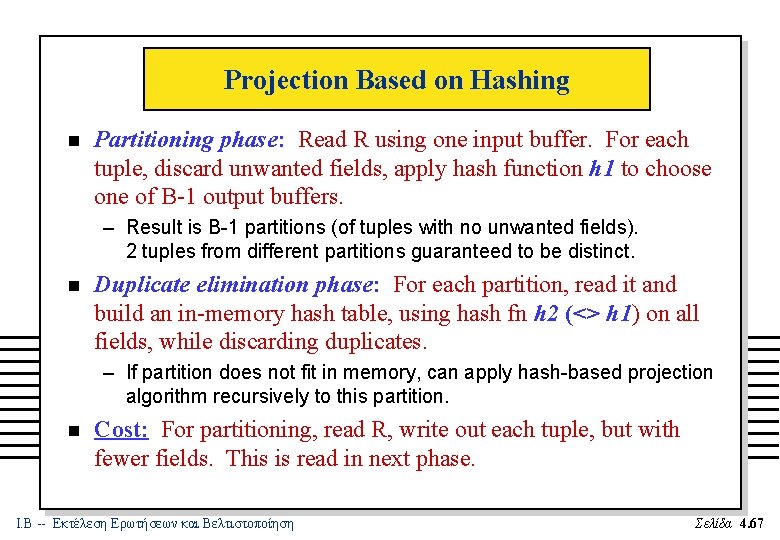

The Projection Operation SELECT DISTINCT FROM R. sid, R. bid Reserves R An approach based on sorting: – Modify Pass 0 of external sort to eliminate unwanted fields. Thus, runs of about 2 B pages are produced, but tuples in runs are smaller than input tuples. (Size ratio depends on # and size of fields that are dropped. ) – Modify merging passes to eliminate duplicates. Thus, number of result tuples smaller than input. (Difference depends on # of duplicates. ) – Cost: In Pass 0, read original relation (size M), write out same number of smaller tuples. In merging passes, fewer tuples written out in each pass. Using Reserves example, 1000 input pages reduced to 250 in Pass 0 if size ratio is 0. 25 Ι. Β -- Εκτέλεση Ερωτήσεων και Βελτιστοποίηση Σελίδα 4. 66

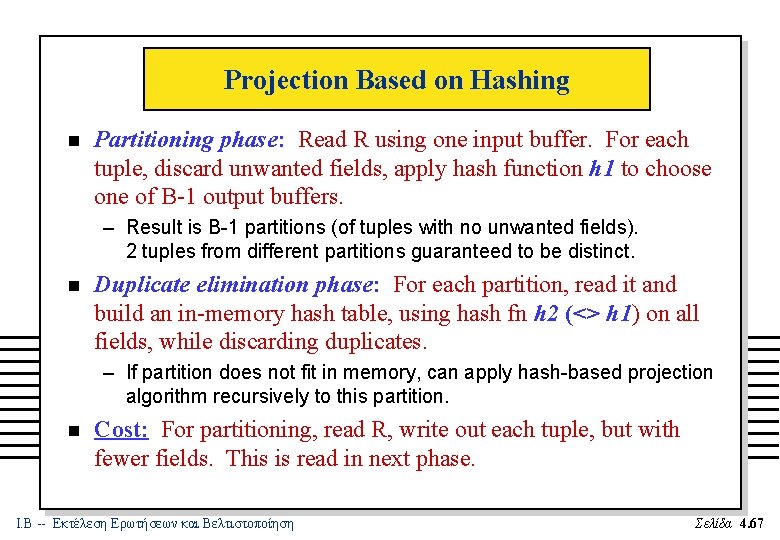

Projection Based on Hashing n Partitioning phase: Read R using one input buffer. For each tuple, discard unwanted fields, apply hash function h 1 to choose one of B-1 output buffers. – Result is B-1 partitions (of tuples with no unwanted fields). 2 tuples from different partitions guaranteed to be distinct. n Duplicate elimination phase: For each partition, read it and build an in-memory hash table, using hash fn h 2 (<> h 1) on all fields, while discarding duplicates. – If partition does not fit in memory, can apply hash-based projection algorithm recursively to this partition. n Cost: For partitioning, read R, write out each tuple, but with fewer fields. This is read in next phase. Ι. Β -- Εκτέλεση Ερωτήσεων και Βελτιστοποίηση Σελίδα 4. 67

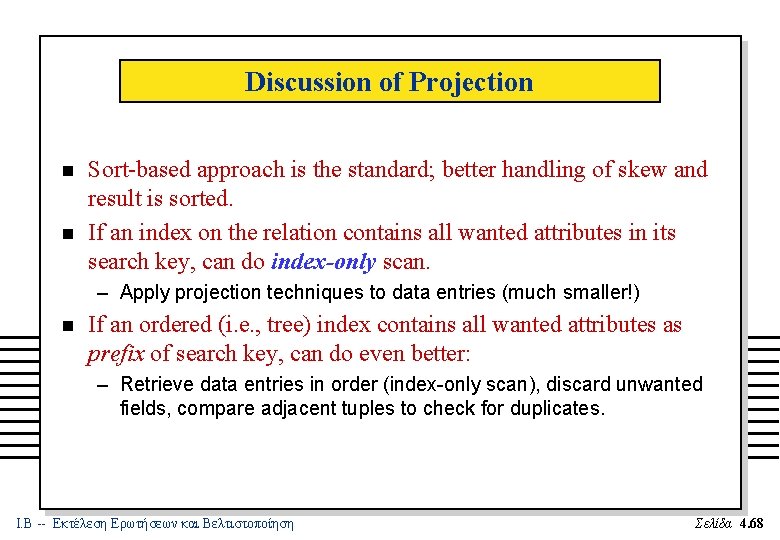

Discussion of Projection n n Sort-based approach is the standard; better handling of skew and result is sorted. If an index on the relation contains all wanted attributes in its search key, can do index-only scan. – Apply projection techniques to data entries (much smaller!) n If an ordered (i. e. , tree) index contains all wanted attributes as prefix of search key, can do even better: – Retrieve data entries in order (index-only scan), discard unwanted fields, compare adjacent tuples to check for duplicates. Ι. Β -- Εκτέλεση Ερωτήσεων και Βελτιστοποίηση Σελίδα 4. 68

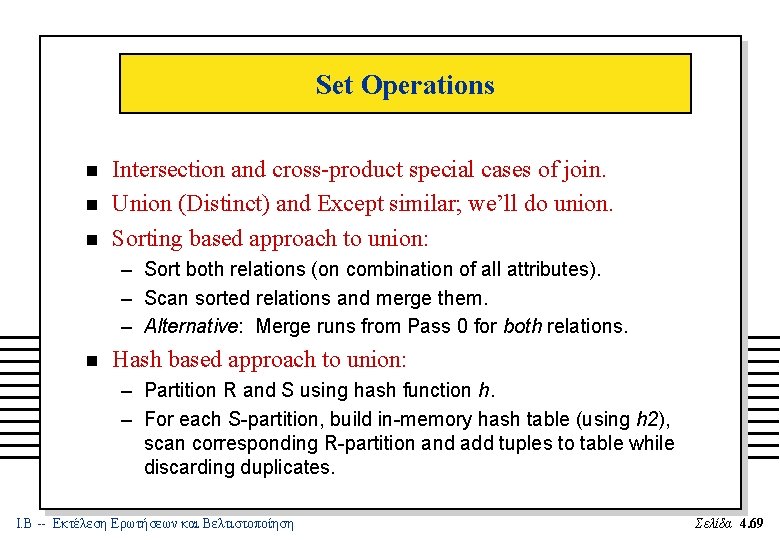

Set Operations n n n Intersection and cross-product special cases of join. Union (Distinct) and Except similar; we’ll do union. Sorting based approach to union: – Sort both relations (on combination of all attributes). – Scan sorted relations and merge them. – Alternative: Merge runs from Pass 0 for both relations. n Hash based approach to union: – Partition R and S using hash function h. – For each S-partition, build in-memory hash table (using h 2), scan corresponding R-partition and add tuples to table while discarding duplicates. Ι. Β -- Εκτέλεση Ερωτήσεων και Βελτιστοποίηση Σελίδα 4. 69

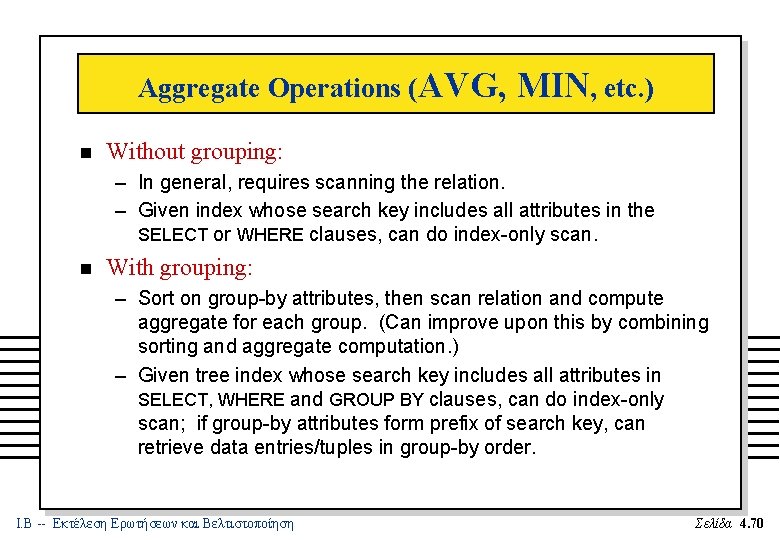

Aggregate Operations (AVG, n MIN, etc. ) Without grouping: – In general, requires scanning the relation. – Given index whose search key includes all attributes in the SELECT or WHERE clauses, can do index-only scan. n With grouping: – Sort on group-by attributes, then scan relation and compute aggregate for each group. (Can improve upon this by combining sorting and aggregate computation. ) – Given tree index whose search key includes all attributes in SELECT, WHERE and GROUP BY clauses, can do index-only scan; if group-by attributes form prefix of search key, can retrieve data entries/tuples in group-by order. Ι. Β -- Εκτέλεση Ερωτήσεων και Βελτιστοποίηση Σελίδα 4. 70

Impact of Buffering n n If several operations are executing concurrently, estimating the number of available buffer pages is guesswork. Repeated access patterns interact with buffer replacement policy. – e. g. , Inner relation is scanned repeatedly in Simple Nested Loop Join. With enough buffer pages to hold inner, replacement policy does not matter. Otherwise, MRU is best, LRU is worst (sequential flooding). – Does replacement policy matter for Block Nested Loops? – What about Index Nested Loops? Sort-Merge Join? Ι. Β -- Εκτέλεση Ερωτήσεων και Βελτιστοποίηση Σελίδα 4. 71

Summary for Relational Operators Implementation n A virtue of relational DBMSs: queries are composed of a few basic operators; the implementation of these operators can be carefully tuned (and it is important to do this!). Many alternative implementation techniques for each operator; no universally superior technique for most operators. Must consider available alternatives for each operation in a query and choose best one based on system statistics, etc. This is part of the broader task of optimizing a query composed of several ops. Ι. Β -- Εκτέλεση Ερωτήσεων και Βελτιστοποίηση Σελίδα 4. 72

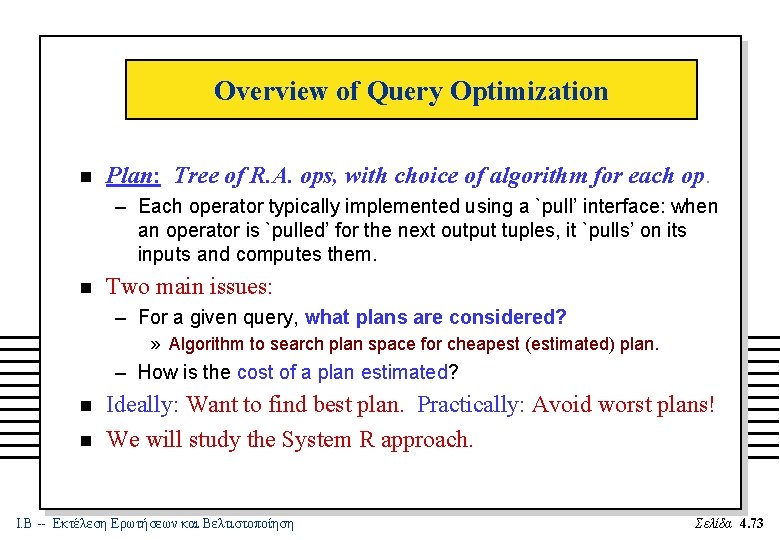

Overview of Query Optimization n Plan: Tree of R. A. ops, with choice of algorithm for each op. – Each operator typically implemented using a `pull’ interface: when an operator is `pulled’ for the next output tuples, it `pulls’ on its inputs and computes them. n Two main issues: – For a given query, what plans are considered? » Algorithm to search plan space for cheapest (estimated) plan. – How is the cost of a plan estimated? n n Ideally: Want to find best plan. Practically: Avoid worst plans! We will study the System R approach. Ι. Β -- Εκτέλεση Ερωτήσεων και Βελτιστοποίηση Σελίδα 4. 73

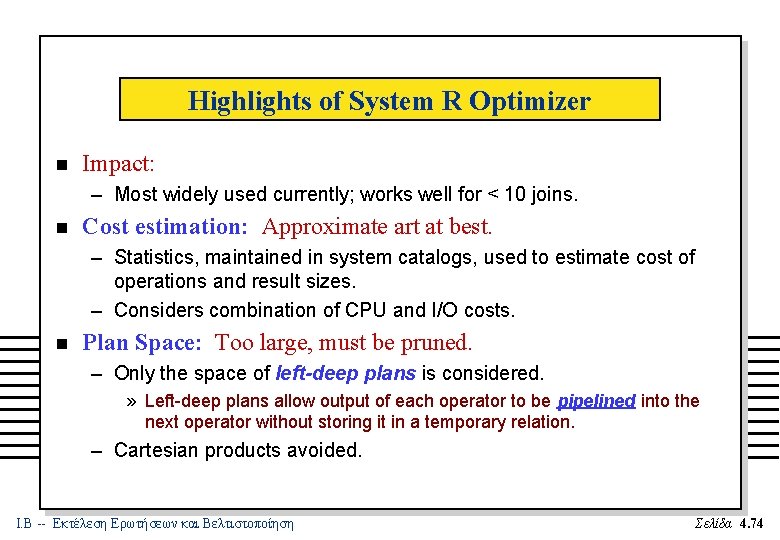

Highlights of System R Optimizer n Impact: – Most widely used currently; works well for < 10 joins. n Cost estimation: Approximate art at best. – Statistics, maintained in system catalogs, used to estimate cost of operations and result sizes. – Considers combination of CPU and I/O costs. n Plan Space: Too large, must be pruned. – Only the space of left-deep plans is considered. » Left-deep plans allow output of each operator to be pipelined into the next operator without storing it in a temporary relation. – Cartesian products avoided. Ι. Β -- Εκτέλεση Ερωτήσεων και Βελτιστοποίηση Σελίδα 4. 74

Schema for Examples Sailors (sid: integer, sname: string, rating: integer, age: real) Reserves (sid: integer, bid: integer, day: dates, rname: string) n n Similar to old schema; rname added for variations. Reserves: – Each tuple is 40 bytes long, 100 tuples per page, 1000 pages. n Sailors: – Each tuple is 50 bytes long, 80 tuples per page, 500 pages. Ι. Β -- Εκτέλεση Ερωτήσεων και Βελτιστοποίηση Σελίδα 4. 75

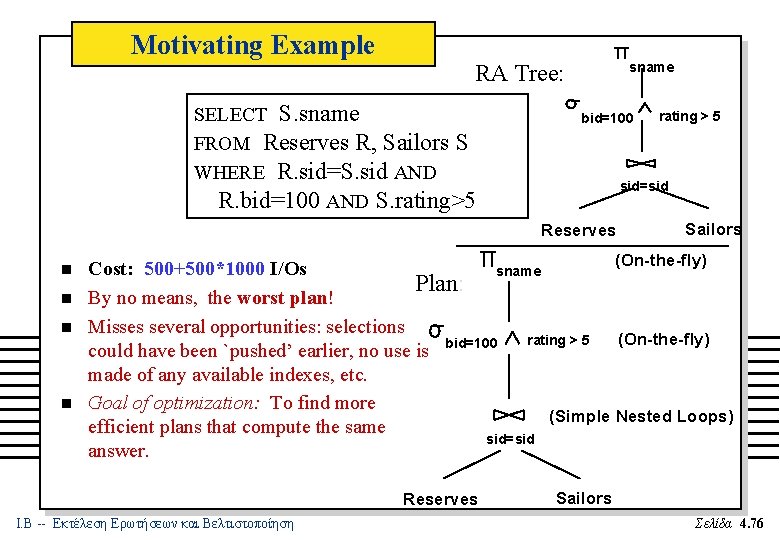

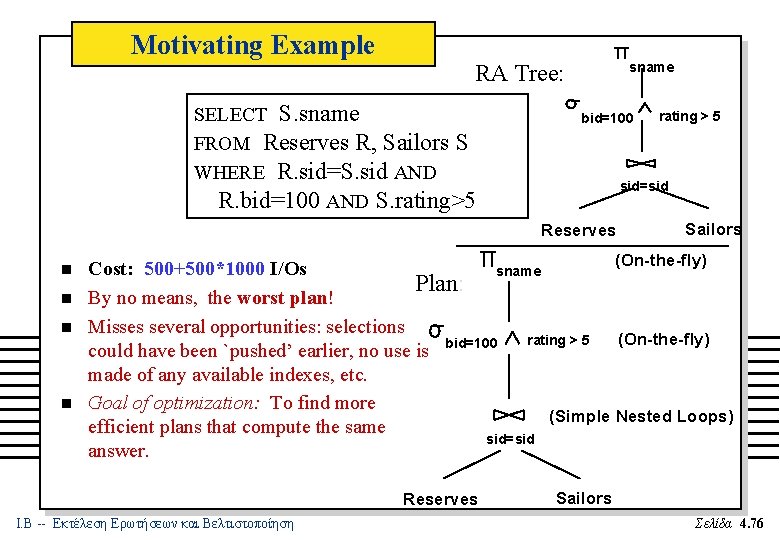

Motivating Example RA Tree: SELECT S. sname FROM Reserves R, Sailors S WHERE R. sid=S. sid AND R. bid=100 AND S. rating>5 sname bid=100 sid=sid Reserves n n rating > 5 Sailors (On-the-fly) Cost: 500+500*1000 I/Os sname Plan: By no means, the worst plan! Misses several opportunities: selections rating > 5 (On-the-fly) could have been `pushed’ earlier, no use is bid=100 made of any available indexes, etc. Goal of optimization: To find more (Simple Nested Loops) efficient plans that compute the same sid=sid answer. Reserves Ι. Β -- Εκτέλεση Ερωτήσεων και Βελτιστοποίηση Sailors Σελίδα 4. 76

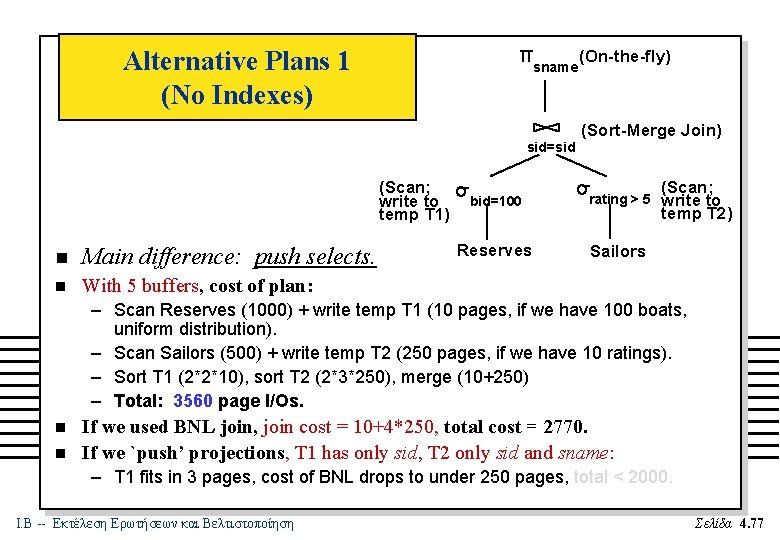

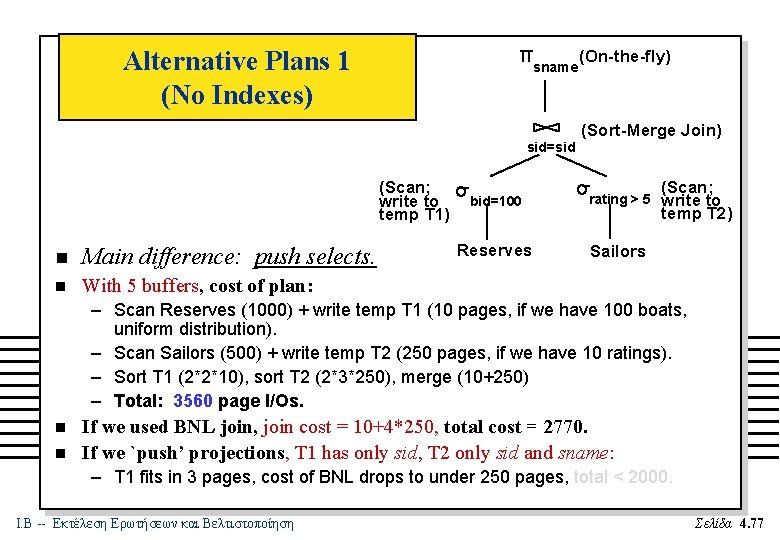

Alternative Plans 1 (No Indexes) sname sid=sid (Scan; write to temp T 1) n Main difference: push selects. n With 5 buffers, cost of plan: (On-the-fly) (Sort-Merge Join) bid=100 rating > 5 Reserves Sailors (Scan; write to temp T 2) – Scan Reserves (1000) + write temp T 1 (10 pages, if we have 100 boats, uniform distribution). – Scan Sailors (500) + write temp T 2 (250 pages, if we have 10 ratings). – Sort T 1 (2*2*10), sort T 2 (2*3*250), merge (10+250) – Total: 3560 page I/Os. n n If we used BNL join, join cost = 10+4*250, total cost = 2770. If we `push’ projections, T 1 has only sid, T 2 only sid and sname: – T 1 fits in 3 pages, cost of BNL drops to under 250 pages, total < 2000. Ι. Β -- Εκτέλεση Ερωτήσεων και Βελτιστοποίηση Σελίδα 4. 77

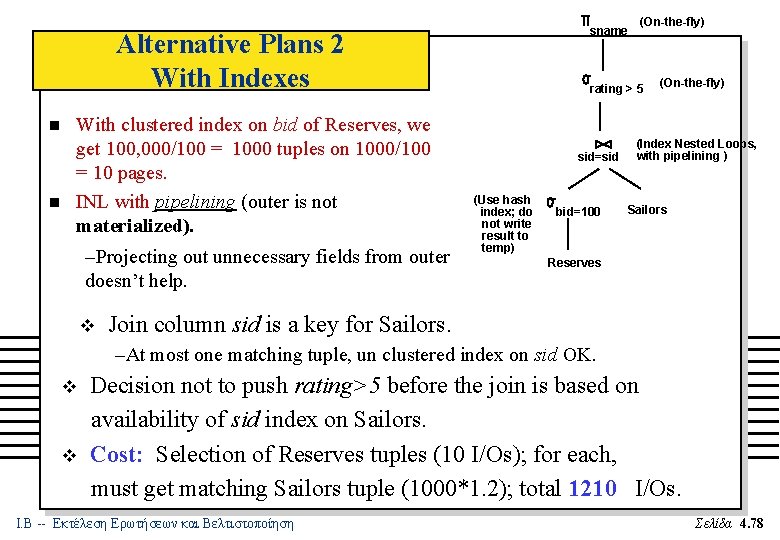

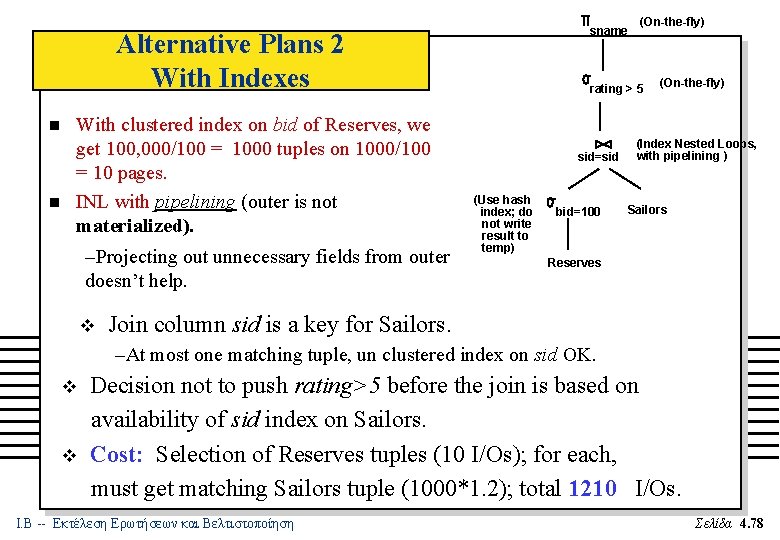

sname Alternative Plans 2 With Indexes n n With clustered index on bid of Reserves, we get 100, 000/100 = 1000 tuples on 1000/100 = 10 pages. INL with pipelining (outer is not materialized). –Projecting out unnecessary fields from outer doesn’t help. v (On-the-fly) rating > 5 sid=sid (Use hash index; do not write result to temp) bid=100 (On-the-fly) (Index Nested Loops, with pipelining ) Sailors Reserves Join column sid is a key for Sailors. –At most one matching tuple, un clustered index on sid OK. v v Decision not to push rating>5 before the join is based on availability of sid index on Sailors. Cost: Selection of Reserves tuples (10 I/Os); for each, must get matching Sailors tuple (1000*1. 2); total 1210 I/Os. Ι. Β -- Εκτέλεση Ερωτήσεων και Βελτιστοποίηση Σελίδα 4. 78

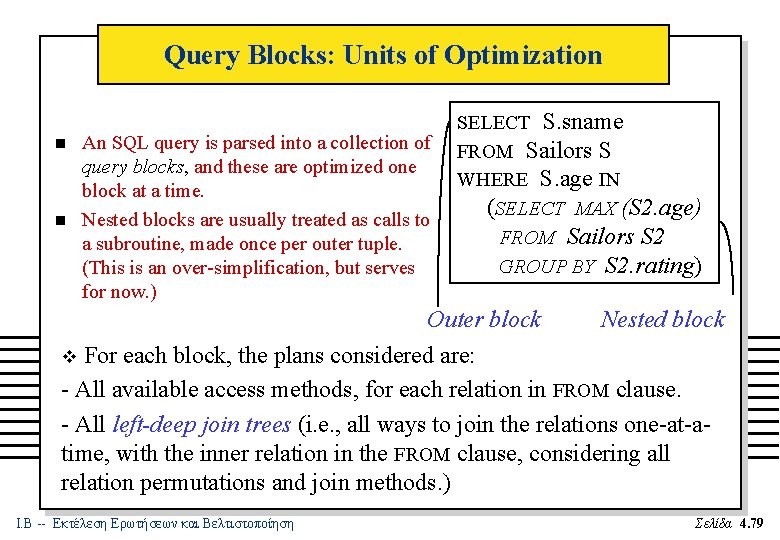

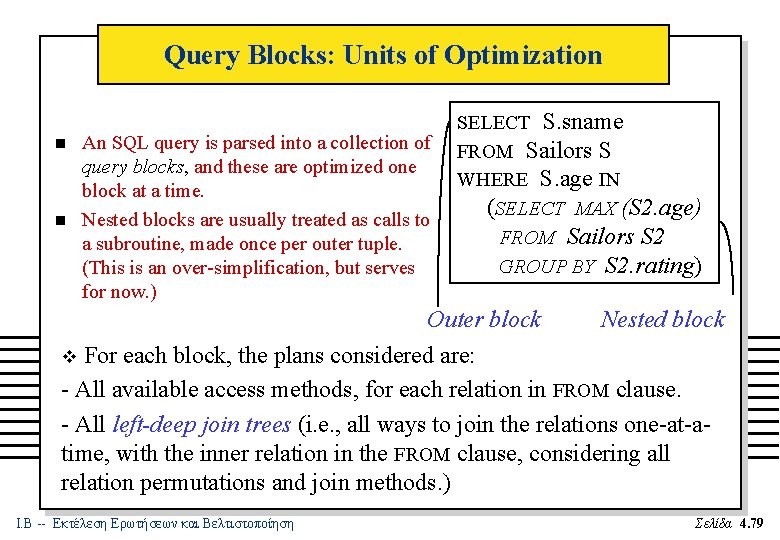

Query Blocks: Units of Optimization n n An SQL query is parsed into a collection of query blocks, and these are optimized one block at a time. Nested blocks are usually treated as calls to a subroutine, made once per outer tuple. (This is an over-simplification, but serves for now. ) SELECT S. sname FROM Sailors S WHERE S. age IN (SELECT MAX (S 2. age) FROM Sailors S 2 GROUP BY S 2. rating) Outer block Nested block v For each block, the plans considered are: - All available access methods, for each relation in FROM clause. - All left-deep join trees (i. e. , all ways to join the relations one-at-atime, with the inner relation in the FROM clause, considering all relation permutations and join methods. ) Ι. Β -- Εκτέλεση Ερωτήσεων και Βελτιστοποίηση Σελίδα 4. 79

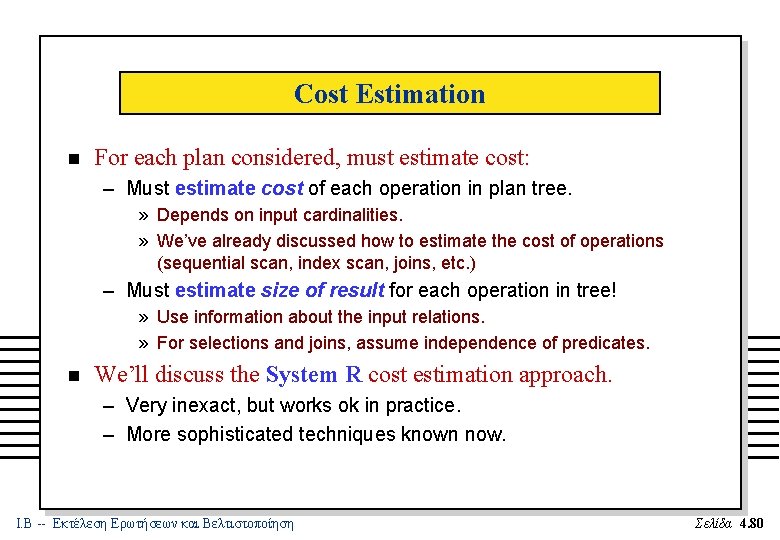

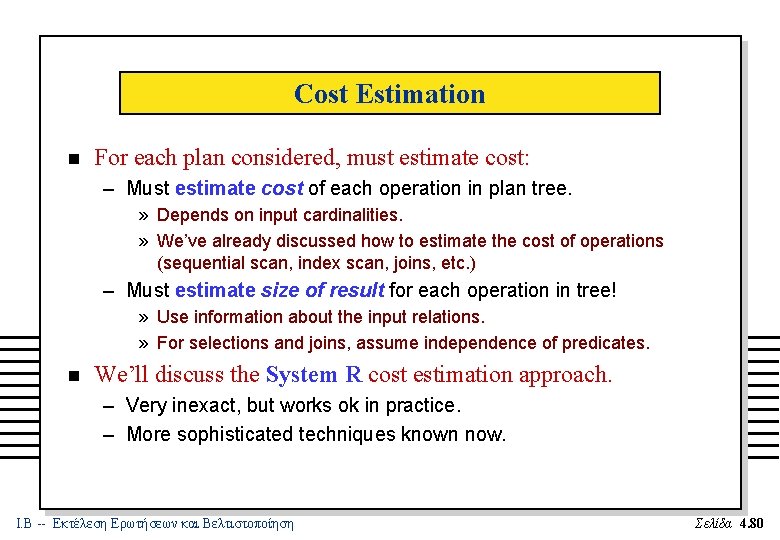

Cost Estimation n For each plan considered, must estimate cost: – Must estimate cost of each operation in plan tree. » Depends on input cardinalities. » We’ve already discussed how to estimate the cost of operations (sequential scan, index scan, joins, etc. ) – Must estimate size of result for each operation in tree! » Use information about the input relations. » For selections and joins, assume independence of predicates. n We’ll discuss the System R cost estimation approach. – Very inexact, but works ok in practice. – More sophisticated techniques known now. Ι. Β -- Εκτέλεση Ερωτήσεων και Βελτιστοποίηση Σελίδα 4. 80

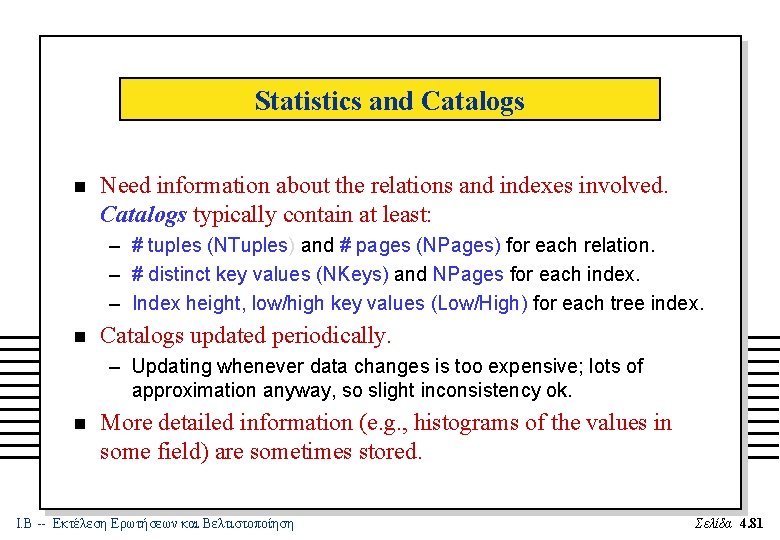

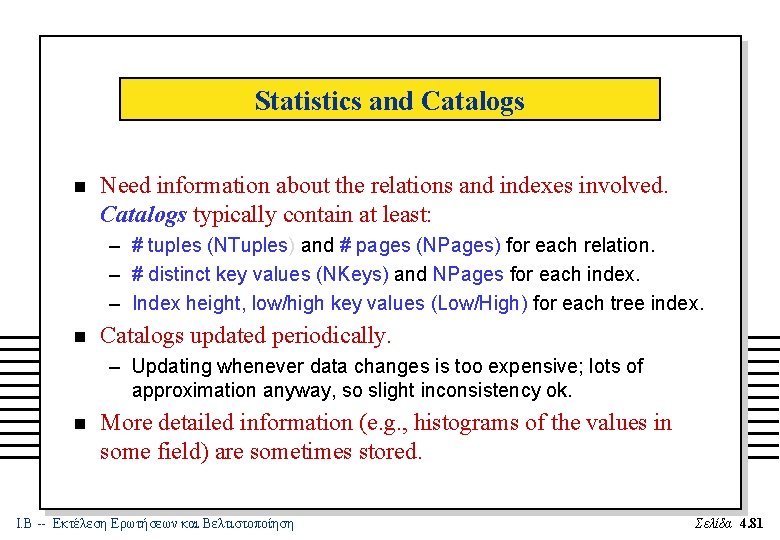

Statistics and Catalogs n Need information about the relations and indexes involved. Catalogs typically contain at least: – # tuples (NTuples) and # pages (NPages) for each relation. – # distinct key values (NKeys) and NPages for each index. – Index height, low/high key values (Low/High) for each tree index. n Catalogs updated periodically. – Updating whenever data changes is too expensive; lots of approximation anyway, so slight inconsistency ok. n More detailed information (e. g. , histograms of the values in some field) are sometimes stored. Ι. Β -- Εκτέλεση Ερωτήσεων και Βελτιστοποίηση Σελίδα 4. 81

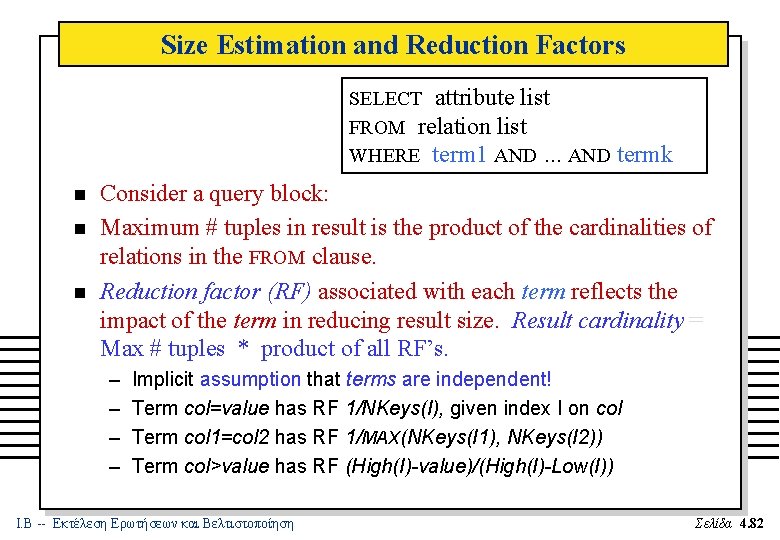

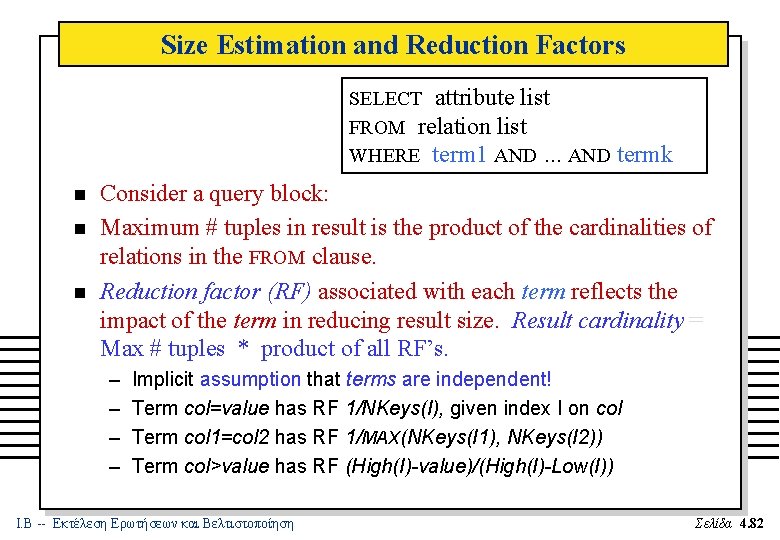

Size Estimation and Reduction Factors SELECT attribute list FROM relation list WHERE term 1 AND. . . AND n n n termk Consider a query block: Maximum # tuples in result is the product of the cardinalities of relations in the FROM clause. Reduction factor (RF) associated with each term reflects the impact of the term in reducing result size. Result cardinality = Max # tuples * product of all RF’s. – – Implicit assumption that terms are independent! Term col=value has RF 1/NKeys(I), given index I on col Term col 1=col 2 has RF 1/MAX(NKeys(I 1), NKeys(I 2)) Term col>value has RF (High(I)-value)/(High(I)-Low(I)) Ι. Β -- Εκτέλεση Ερωτήσεων και Βελτιστοποίηση Σελίδα 4. 82

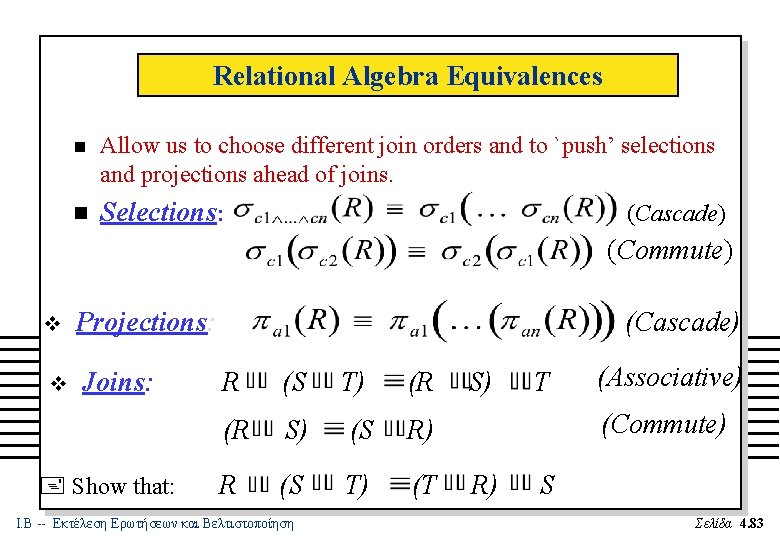

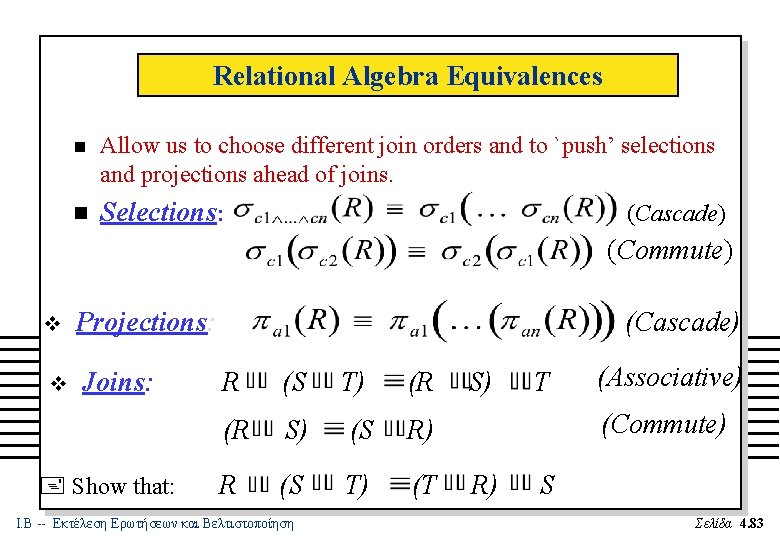

Relational Algebra Equivalences n Allow us to choose different join orders and to `push’ selections and projections ahead of joins. n Selections: (Cascade) (Commute) v Projections: v Joins: + Show that: (Cascade) R (S T) (R (R S) (S R) R (S T) (T Ι. Β -- Εκτέλεση Ερωτήσεων και Βελτιστοποίηση S) T (Associative) (Commute) R) S Σελίδα 4. 83

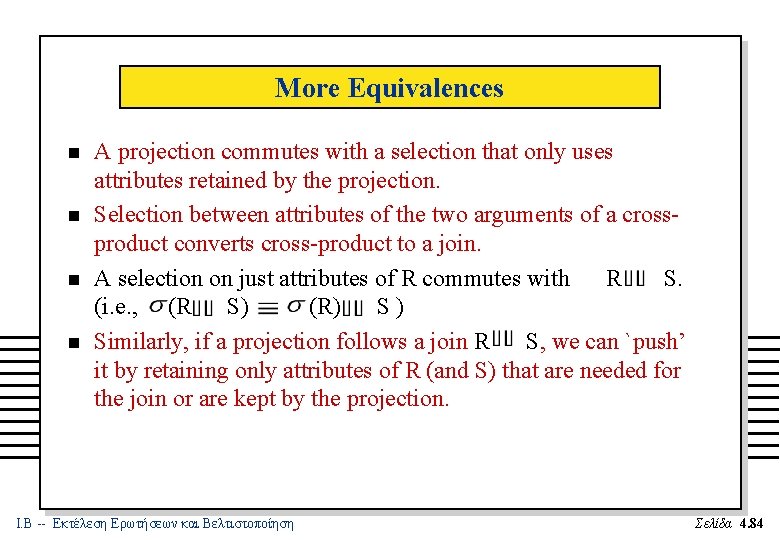

More Equivalences n n A projection commutes with a selection that only uses attributes retained by the projection. Selection between attributes of the two arguments of a crossproduct converts cross-product to a join. A selection on just attributes of R commutes with R S. (i. e. , (R S) (R) S) Similarly, if a projection follows a join R S, we can `push’ it by retaining only attributes of R (and S) that are needed for the join or are kept by the projection. Ι. Β -- Εκτέλεση Ερωτήσεων και Βελτιστοποίηση Σελίδα 4. 84

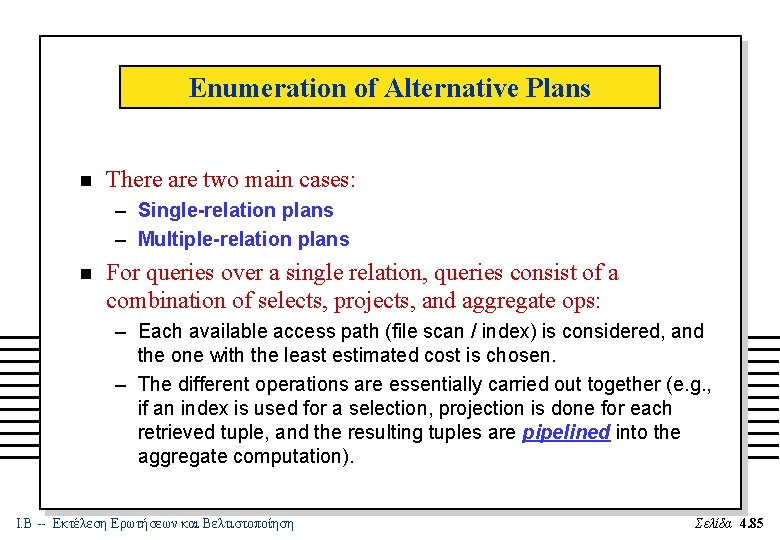

Enumeration of Alternative Plans n There are two main cases: – Single-relation plans – Multiple-relation plans n For queries over a single relation, queries consist of a combination of selects, projects, and aggregate ops: – Each available access path (file scan / index) is considered, and the one with the least estimated cost is chosen. – The different operations are essentially carried out together (e. g. , if an index is used for a selection, projection is done for each retrieved tuple, and the resulting tuples are pipelined into the aggregate computation). Ι. Β -- Εκτέλεση Ερωτήσεων και Βελτιστοποίηση Σελίδα 4. 85

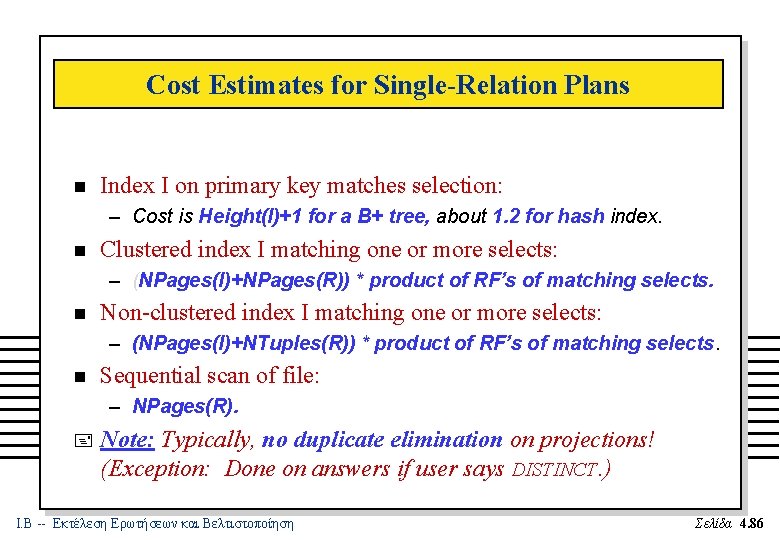

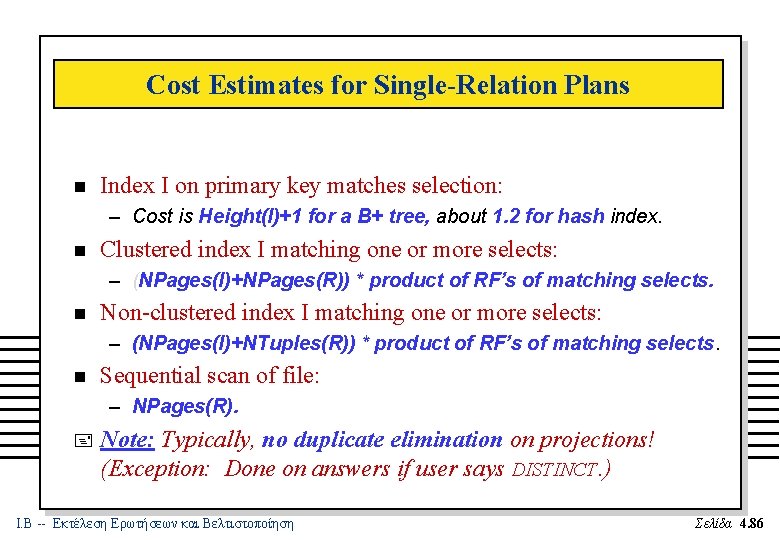

Cost Estimates for Single-Relation Plans n Index I on primary key matches selection: – Cost is Height(I)+1 for a B+ tree, about 1. 2 for hash index. n Clustered index I matching one or more selects: – (NPages(I)+NPages(R)) * product of RF’s of matching selects. n Non-clustered index I matching one or more selects: – (NPages(I)+NTuples(R)) * product of RF’s of matching selects. n Sequential scan of file: – NPages(R). + Note: Typically, no duplicate elimination on projections! (Exception: Done on answers if user says DISTINCT. ) Ι. Β -- Εκτέλεση Ερωτήσεων και Βελτιστοποίηση Σελίδα 4. 86

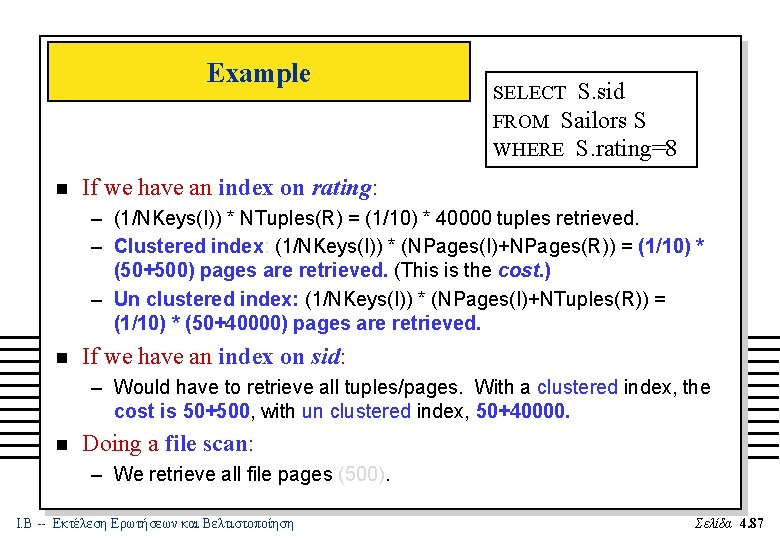

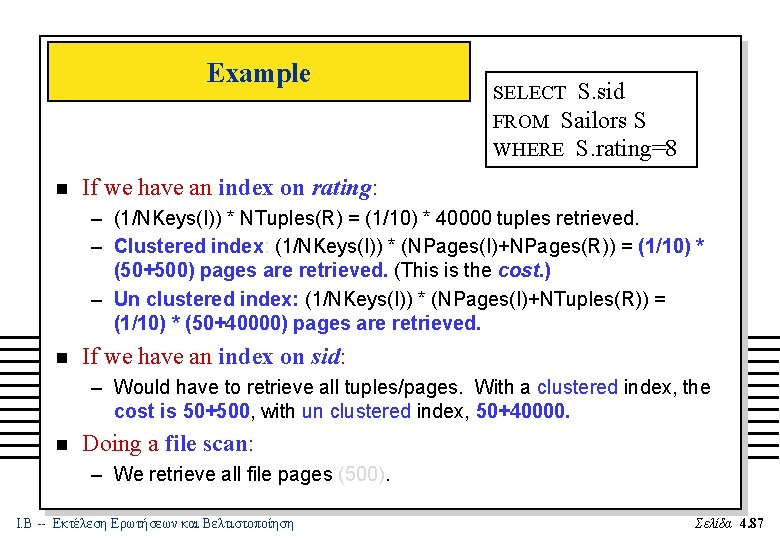

Example n SELECT S. sid FROM Sailors S WHERE S. rating=8 If we have an index on rating: – (1/NKeys(I)) * NTuples(R) = (1/10) * 40000 tuples retrieved. – Clustered index: (1/NKeys(I)) * (NPages(I)+NPages(R)) = (1/10) * (50+500) pages are retrieved. (This is the cost. ) – Un clustered index: (1/NKeys(I)) * (NPages(I)+NTuples(R)) = (1/10) * (50+40000) pages are retrieved. n If we have an index on sid: – Would have to retrieve all tuples/pages. With a clustered index, the cost is 50+500, with un clustered index, 50+40000. n Doing a file scan: – We retrieve all file pages (500). Ι. Β -- Εκτέλεση Ερωτήσεων και Βελτιστοποίηση Σελίδα 4. 87

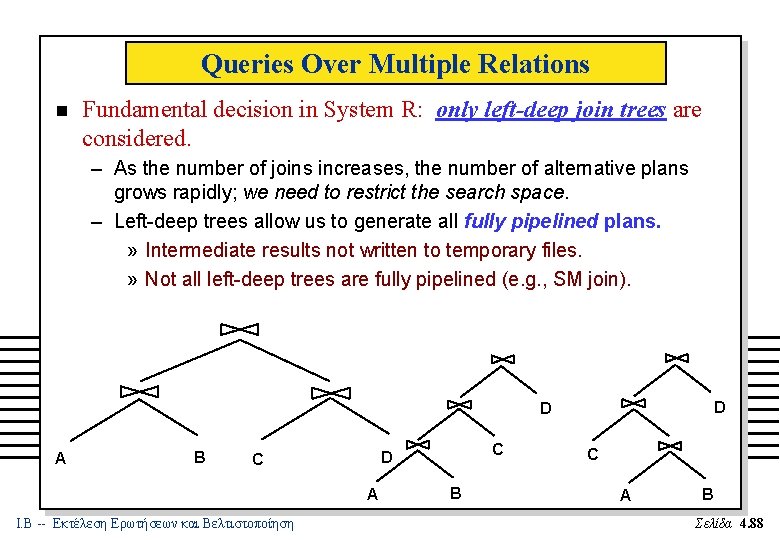

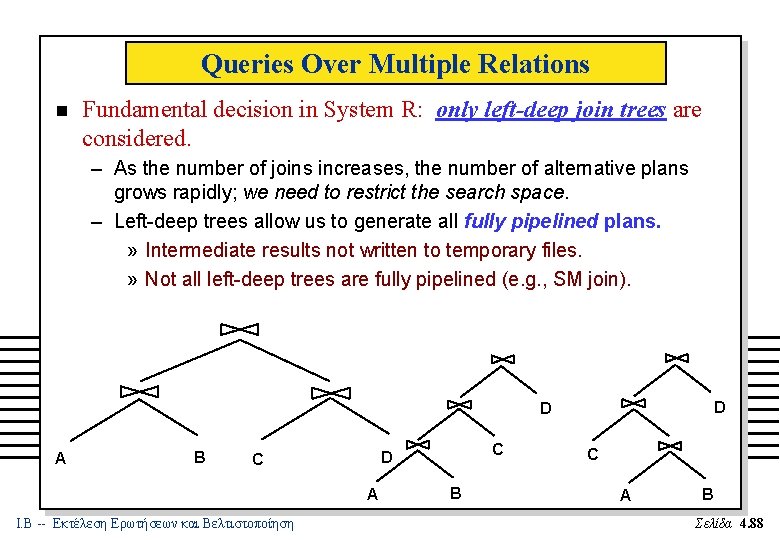

Queries Over Multiple Relations n Fundamental decision in System R: only left-deep join trees are considered. – As the number of joins increases, the number of alternative plans grows rapidly; we need to restrict the search space. – Left-deep trees allow us to generate all fully pipelined plans. » Intermediate results not written to temporary files. » Not all left-deep trees are fully pipelined (e. g. , SM join). D D A B A Ι. Β -- Εκτέλεση Ερωτήσεων και Βελτιστοποίηση C D C B C A B Σελίδα 4. 88

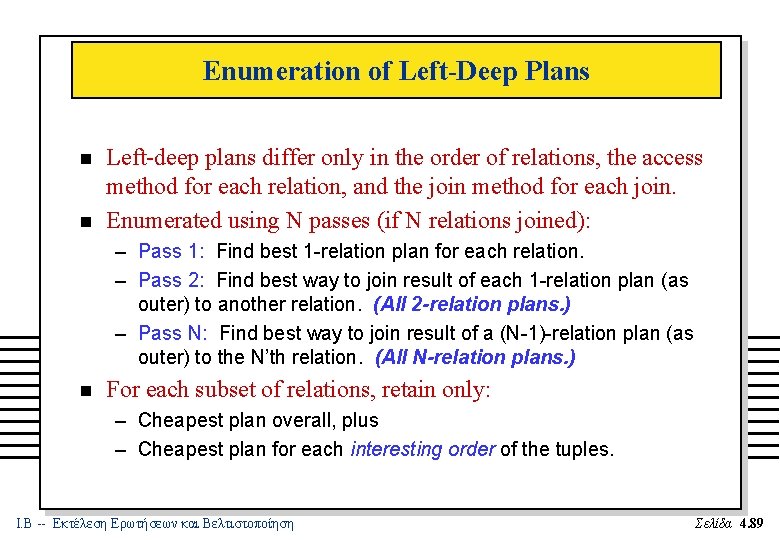

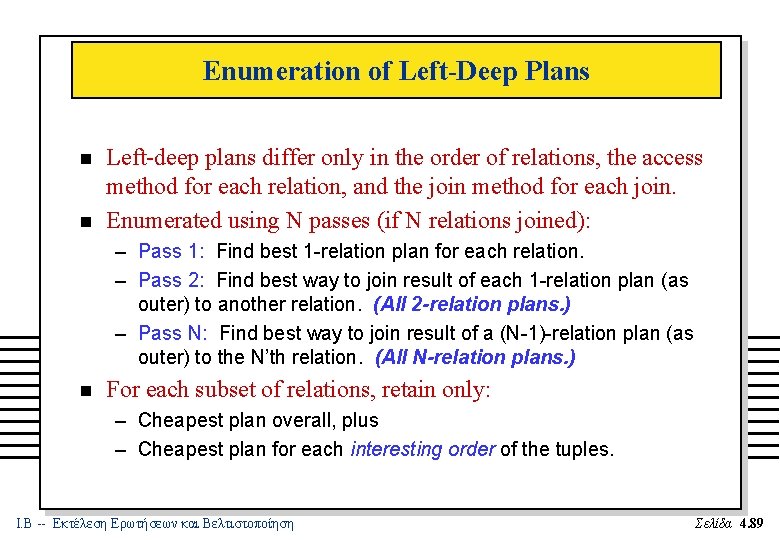

Enumeration of Left-Deep Plans n n Left-deep plans differ only in the order of relations, the access method for each relation, and the join method for each join. Enumerated using N passes (if N relations joined): – Pass 1: Find best 1 -relation plan for each relation. – Pass 2: Find best way to join result of each 1 -relation plan (as outer) to another relation. (All 2 -relation plans. ) – Pass N: Find best way to join result of a (N-1)-relation plan (as outer) to the N’th relation. (All N-relation plans. ) n For each subset of relations, retain only: – Cheapest plan overall, plus – Cheapest plan for each interesting order of the tuples. Ι. Β -- Εκτέλεση Ερωτήσεων και Βελτιστοποίηση Σελίδα 4. 89

Enumeration of Plans (Contd. ) n n ORDER BY, GROUP BY, aggregates etc. handled as a final step, using either an `interestingly ordered’ plan or an additional sorting operator. An N-1 way plan is not combined with an additional relation unless there is a join condition between them, unless all predicates in WHERE have been used up. – i. e. , avoid Cartesian products if possible. n In spite of pruning plan space, this approach is still exponential in the # of tables. Ι. Β -- Εκτέλεση Ερωτήσεων και Βελτιστοποίηση Σελίδα 4. 90

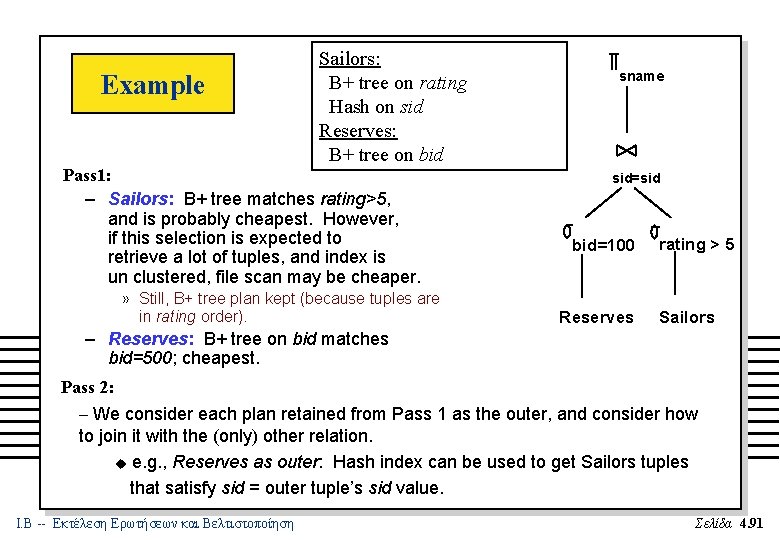

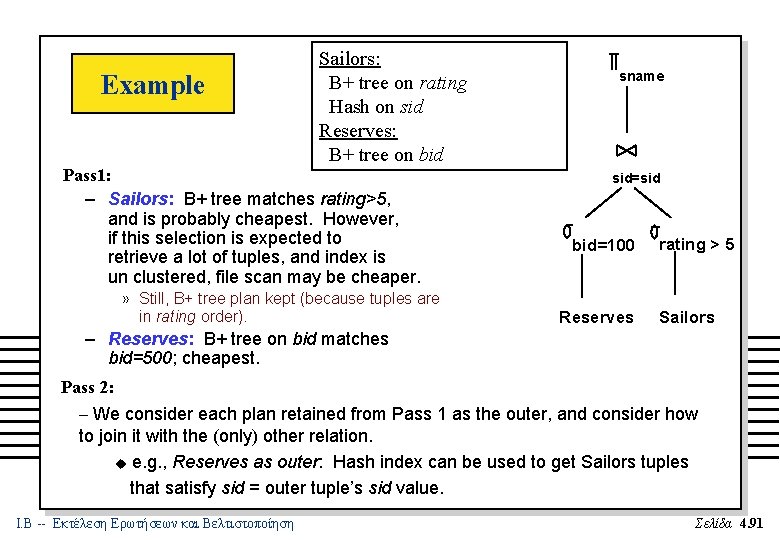

Example Sailors: B+ tree on rating Hash on sid Reserves: B+ tree on bid Pass 1: – Sailors: B+ tree matches rating>5, and is probably cheapest. However, if this selection is expected to retrieve a lot of tuples, and index is un clustered, file scan may be cheaper. » Still, B+ tree plan kept (because tuples are in rating order). sname sid=sid bid=100 Reserves rating > 5 Sailors – Reserves: B+ tree on bid matches bid=500; cheapest. Pass 2: – We consider each plan retained from Pass 1 as the outer, and consider how to join it with the (only) other relation. u e. g. , Reserves as outer: Hash index can be used to get Sailors tuples that satisfy sid = outer tuple’s sid value. Ι. Β -- Εκτέλεση Ερωτήσεων και Βελτιστοποίηση Σελίδα 4. 91

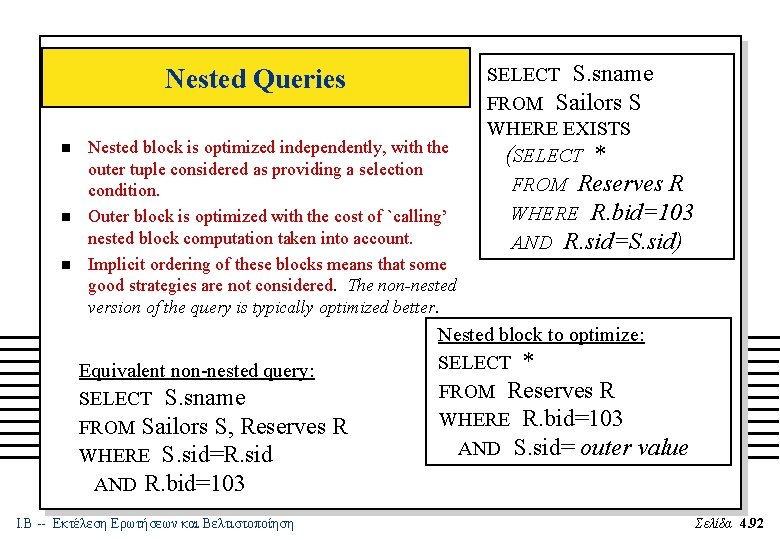

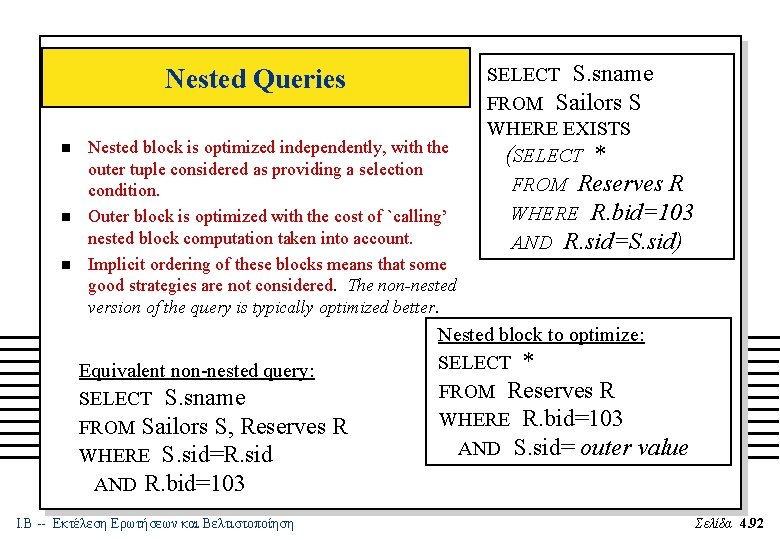

Nested Queries n n n Nested block is optimized independently, with the outer tuple considered as providing a selection condition. Outer block is optimized with the cost of `calling’ nested block computation taken into account. Implicit ordering of these blocks means that some good strategies are not considered. The non-nested version of the query is typically optimized better. Equivalent non-nested query: SELECT S. sname FROM Sailors S, Reserves WHERE S. sid=R. sid AND R. bid=103 Ι. Β -- Εκτέλεση Ερωτήσεων και Βελτιστοποίηση R SELECT S. sname FROM Sailors S WHERE EXISTS (SELECT * FROM Reserves R WHERE R. bid=103 AND R. sid=S. sid) Nested block to optimize: SELECT * FROM Reserves R WHERE R. bid=103 AND S. sid= outer value Σελίδα 4. 92

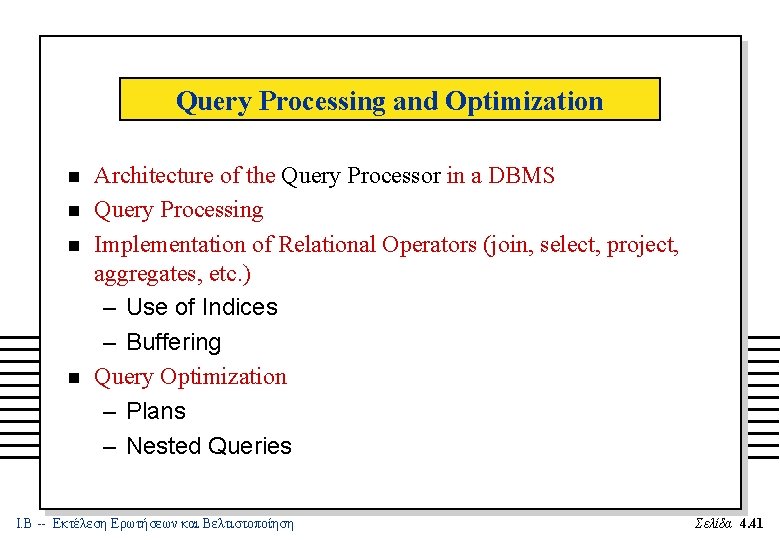

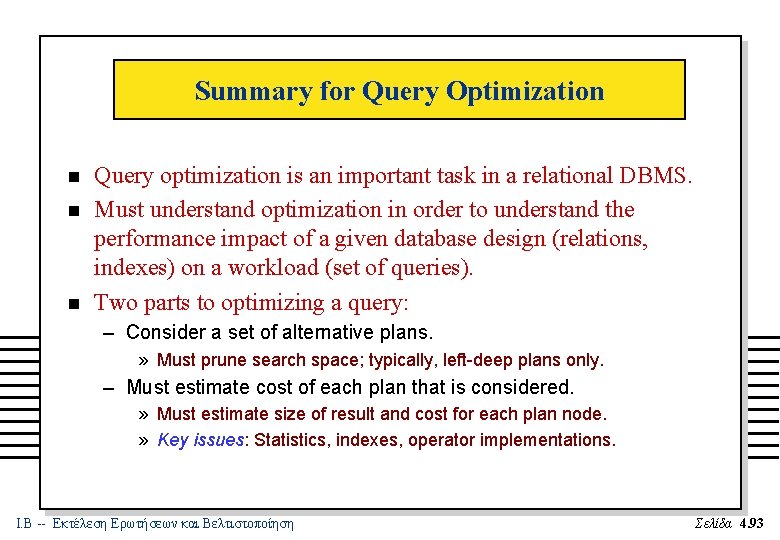

Summary for Query Optimization n Query optimization is an important task in a relational DBMS. Must understand optimization in order to understand the performance impact of a given database design (relations, indexes) on a workload (set of queries). Two parts to optimizing a query: – Consider a set of alternative plans. » Must prune search space; typically, left-deep plans only. – Must estimate cost of each plan that is considered. » Must estimate size of result and cost for each plan node. » Key issues: Statistics, indexes, operator implementations. Ι. Β -- Εκτέλεση Ερωτήσεων και Βελτιστοποίηση Σελίδα 4. 93

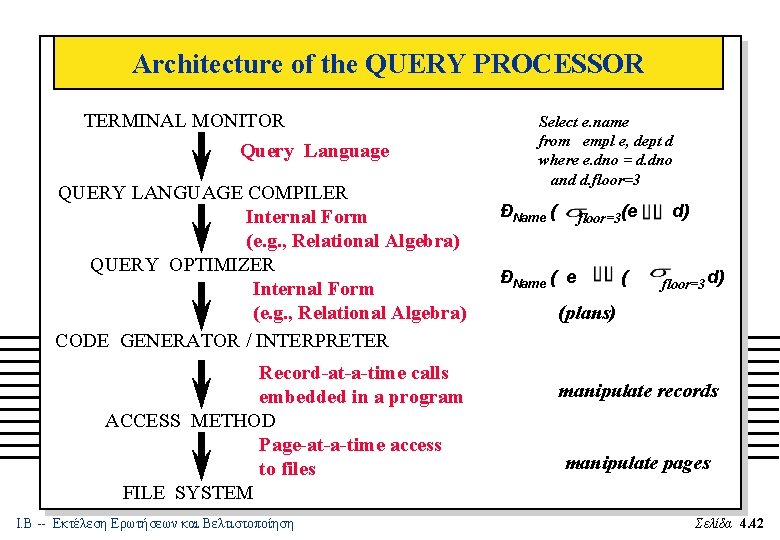

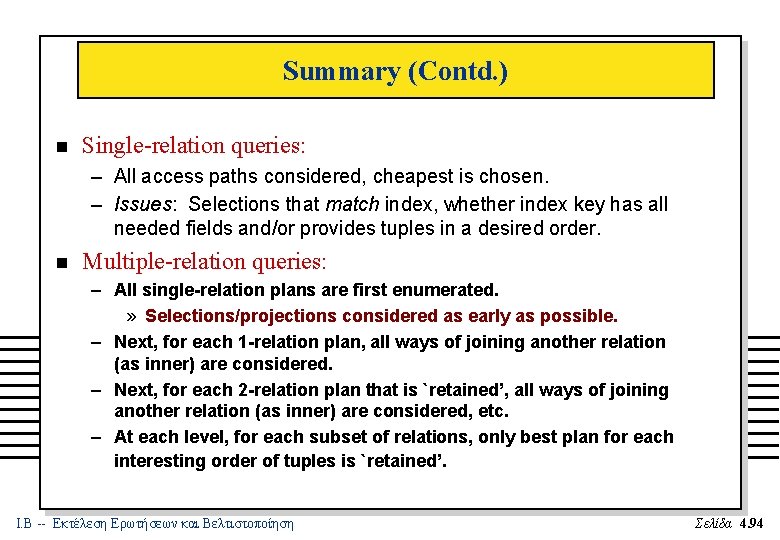

Summary (Contd. ) n Single-relation queries: – All access paths considered, cheapest is chosen. – Issues: Selections that match index, whether index key has all needed fields and/or provides tuples in a desired order. n Multiple-relation queries: – All single-relation plans are first enumerated. » Selections/projections considered as early as possible. – Next, for each 1 -relation plan, all ways of joining another relation (as inner) are considered. – Next, for each 2 -relation plan that is `retained’, all ways of joining another relation (as inner) are considered, etc. – At each level, for each subset of relations, only best plan for each interesting order of tuples is `retained’. Ι. Β -- Εκτέλεση Ερωτήσεων και Βελτιστοποίηση Σελίδα 4. 94