Python Control of Flow and Defining Classes LING

- Slides: 44

Python Control of Flow and Defining Classes LING 5200 Computational Corpus Linguistics Martha Palmer 1

For Loops 2

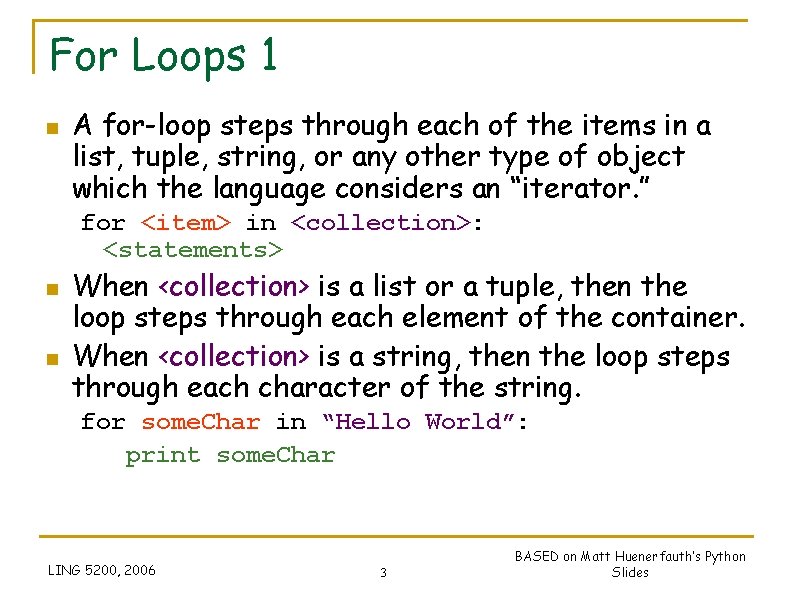

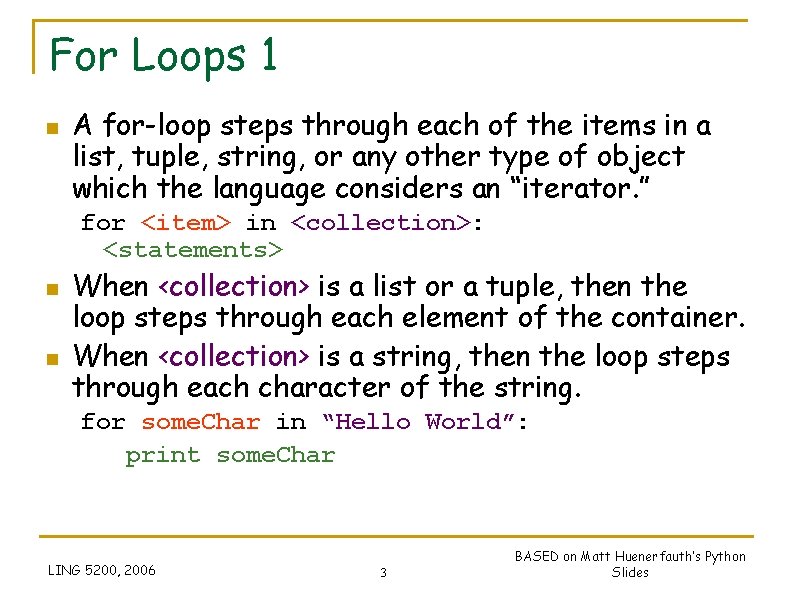

For Loops 1 n A for-loop steps through each of the items in a list, tuple, string, or any other type of object which the language considers an “iterator. ” for <item> in <collection>: <statements> n n When <collection> is a list or a tuple, then the loop steps through each element of the container. When <collection> is a string, then the loop steps through each character of the string. for some. Char in “Hello World”: print some. Char LING 5200, 2006 3 BASED on Matt Huenerfauth’s Python Slides

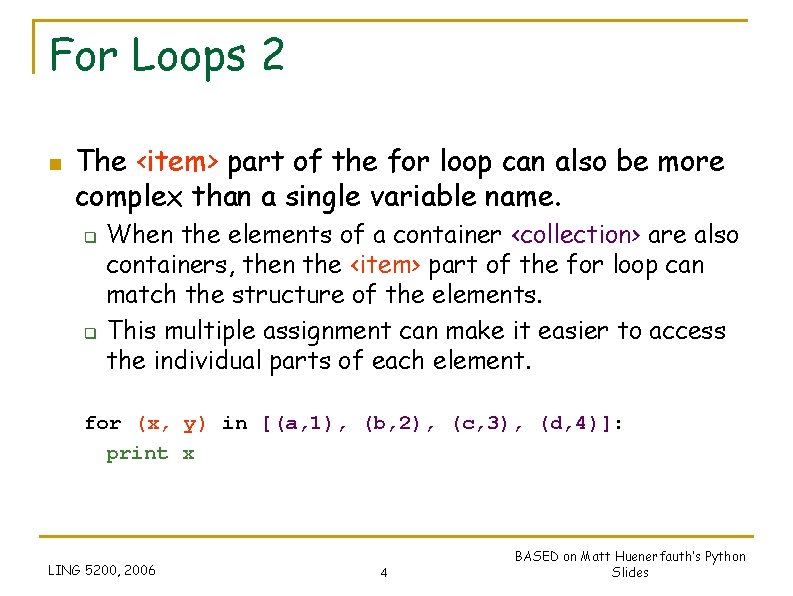

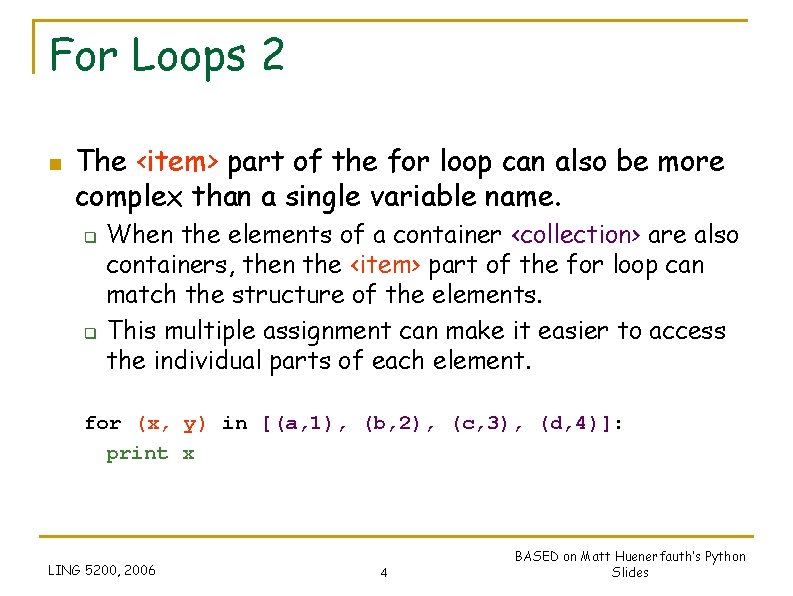

For Loops 2 n The <item> part of the for loop can also be more complex than a single variable name. q q When the elements of a container <collection> are also containers, then the <item> part of the for loop can match the structure of the elements. This multiple assignment can make it easier to access the individual parts of each element. for (x, y) in [(a, 1), (b, 2), (c, 3), (d, 4)]: print x LING 5200, 2006 4 BASED on Matt Huenerfauth’s Python Slides

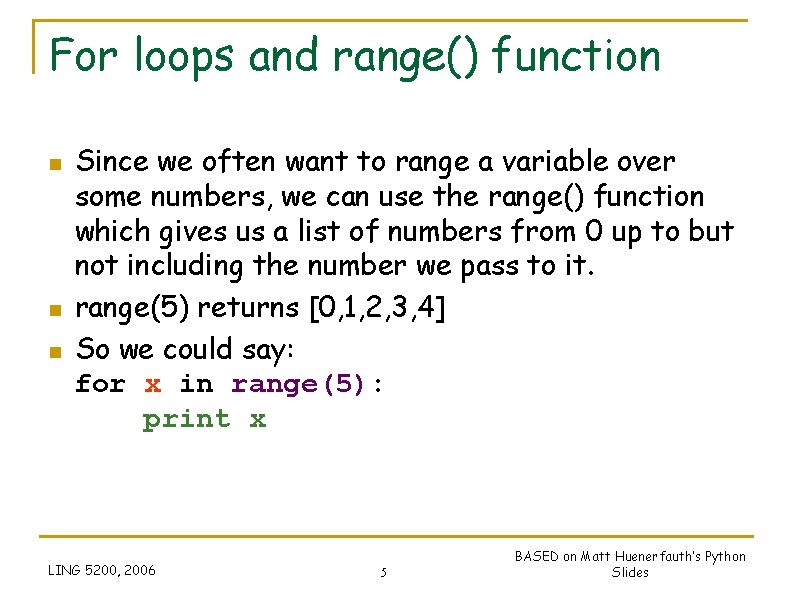

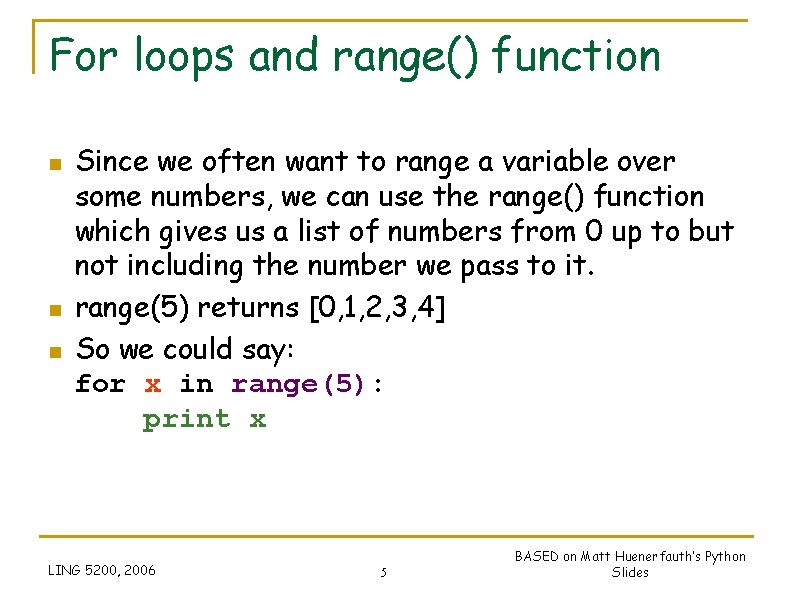

For loops and range() function n Since we often want to range a variable over some numbers, we can use the range() function which gives us a list of numbers from 0 up to but not including the number we pass to it. range(5) returns [0, 1, 2, 3, 4] So we could say: for x in range(5): print x LING 5200, 2006 5 BASED on Matt Huenerfauth’s Python Slides

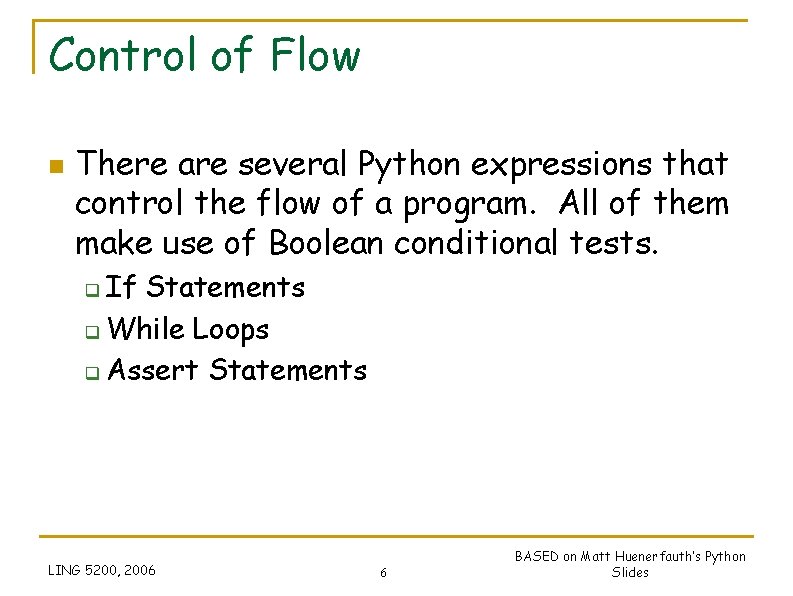

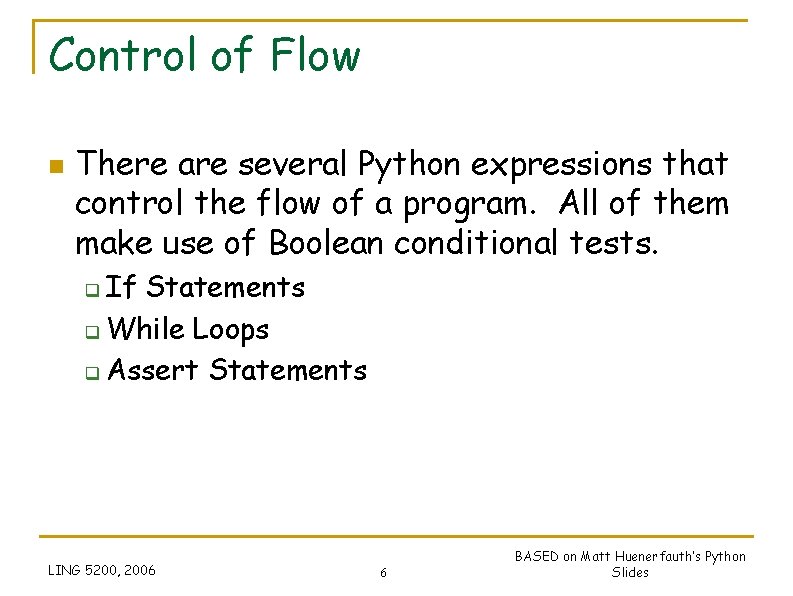

Control of Flow n There are several Python expressions that control the flow of a program. All of them make use of Boolean conditional tests. If Statements q While Loops q Assert Statements q LING 5200, 2006 6 BASED on Matt Huenerfauth’s Python Slides

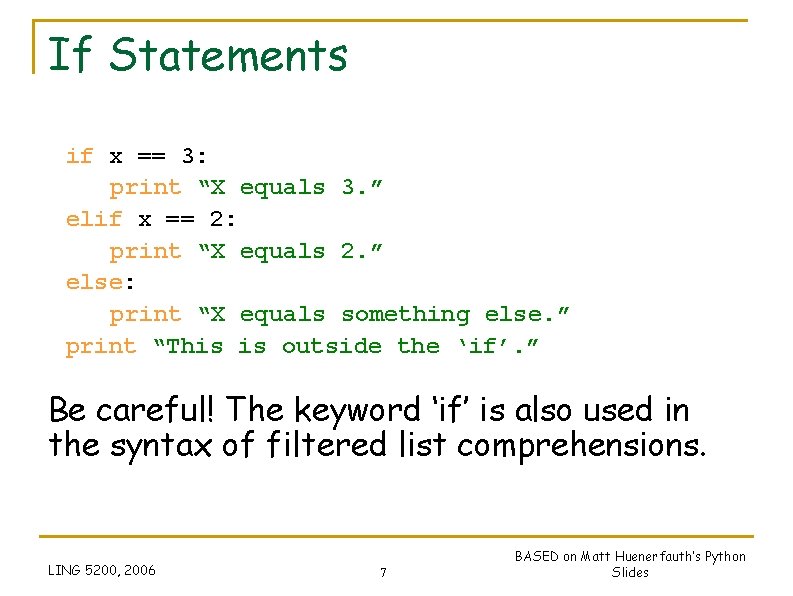

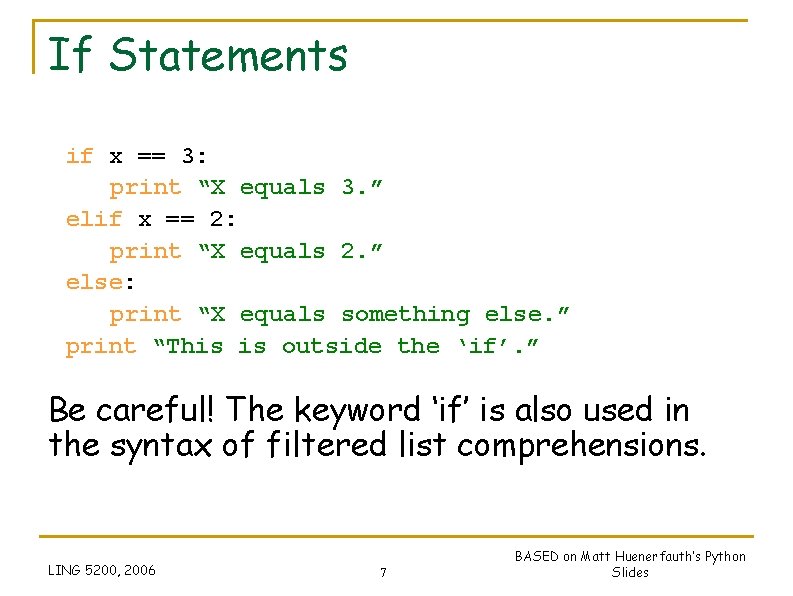

If Statements if x == 3: print “X equals 3. ” elif x == 2: print “X equals 2. ” else: print “X equals something else. ” print “This is outside the ‘if’. ” Be careful! The keyword ‘if’ is also used in the syntax of filtered list comprehensions. LING 5200, 2006 7 BASED on Matt Huenerfauth’s Python Slides

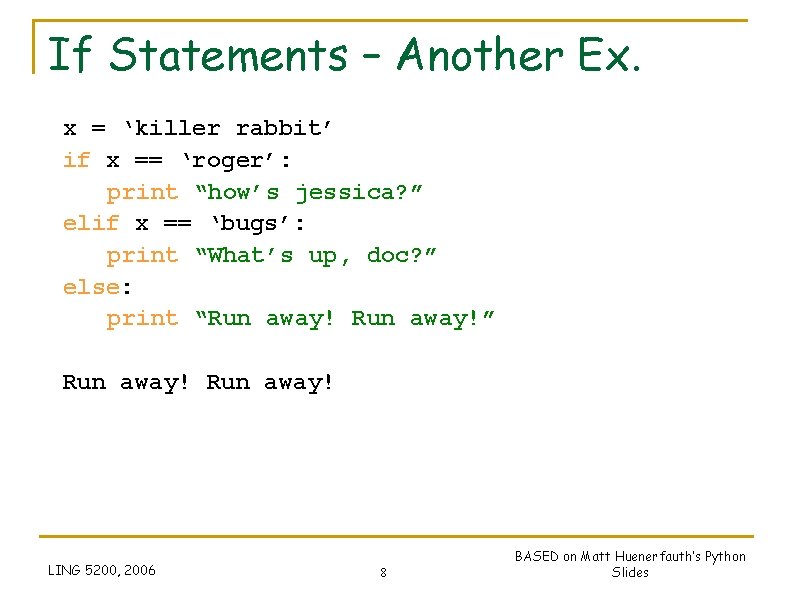

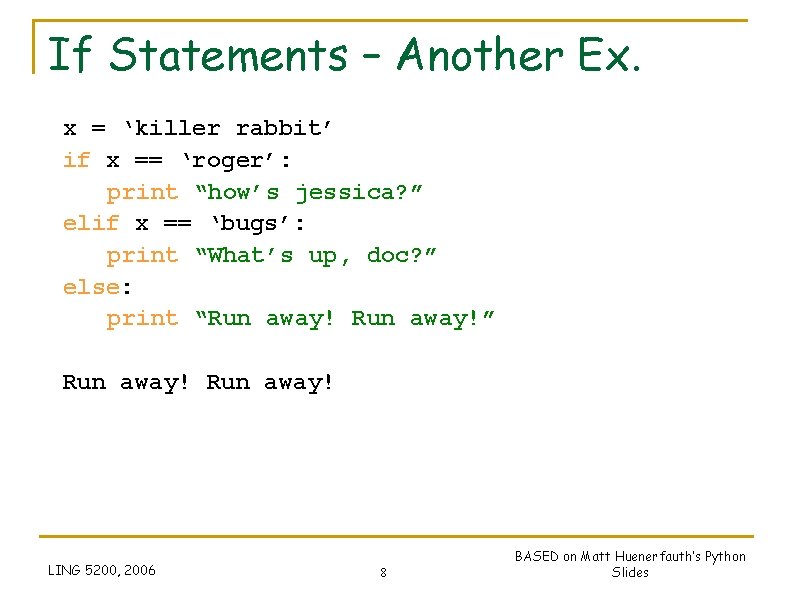

If Statements – Another Ex. x = ‘killer rabbit’ if x == ‘roger’: print “how’s jessica? ” elif x == ‘bugs’: print “What’s up, doc? ” else: print “Run away!” Run away! LING 5200, 2006 8 BASED on Matt Huenerfauth’s Python Slides

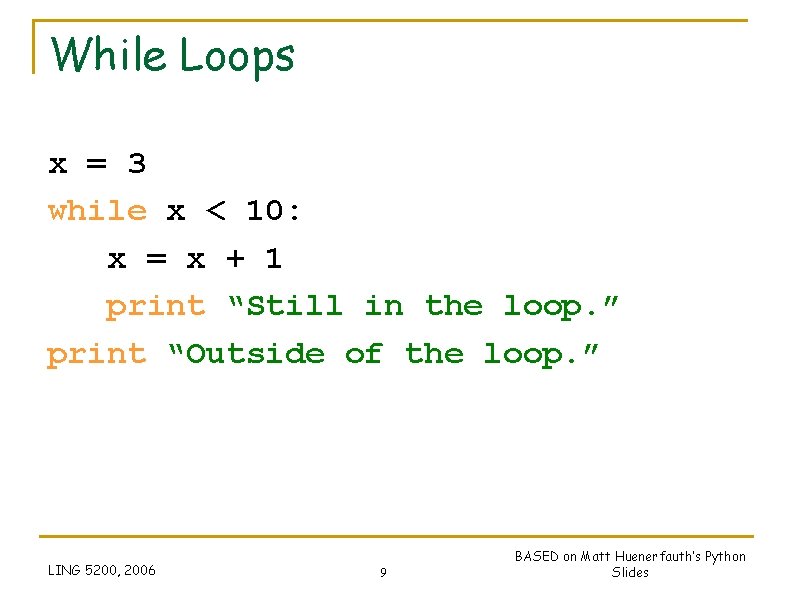

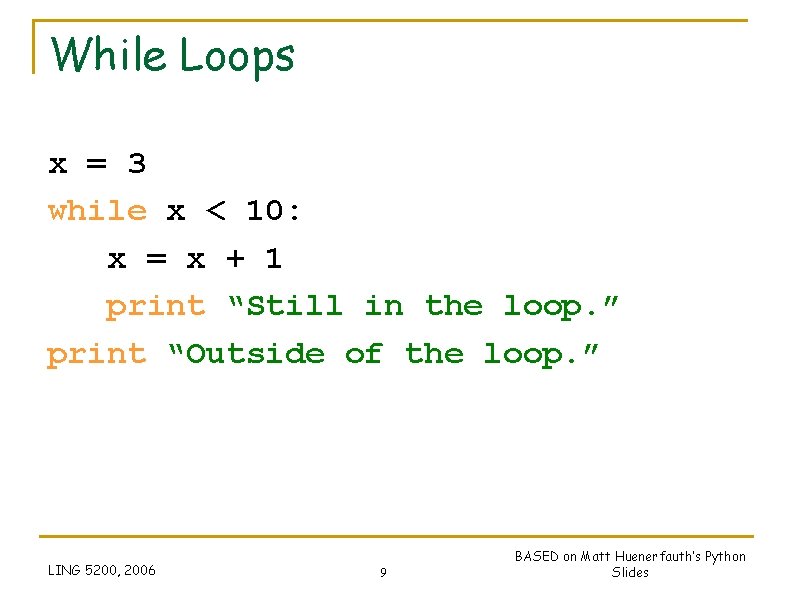

While Loops x = 3 while x < 10: x = x + 1 print “Still in the loop. ” print “Outside of the loop. ” LING 5200, 2006 9 BASED on Matt Huenerfauth’s Python Slides

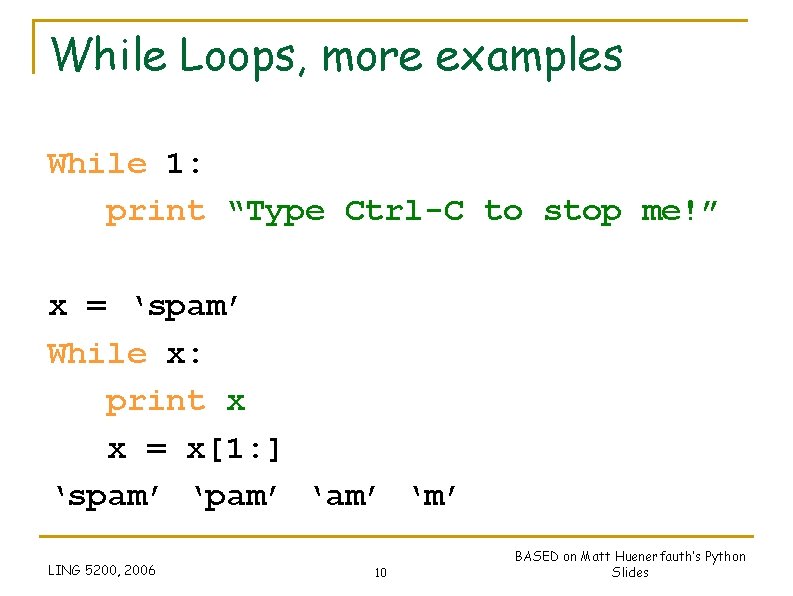

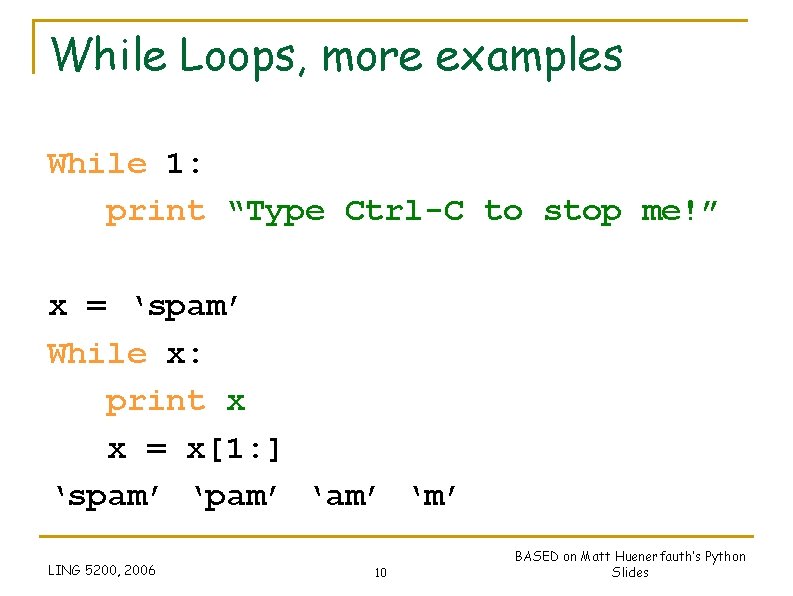

While Loops, more examples While 1: print “Type Ctrl-C to stop me!” x = ‘spam’ While x: print x x = x[1: ] ‘spam’ ‘am’ ‘m’ LING 5200, 2006 10 BASED on Matt Huenerfauth’s Python Slides

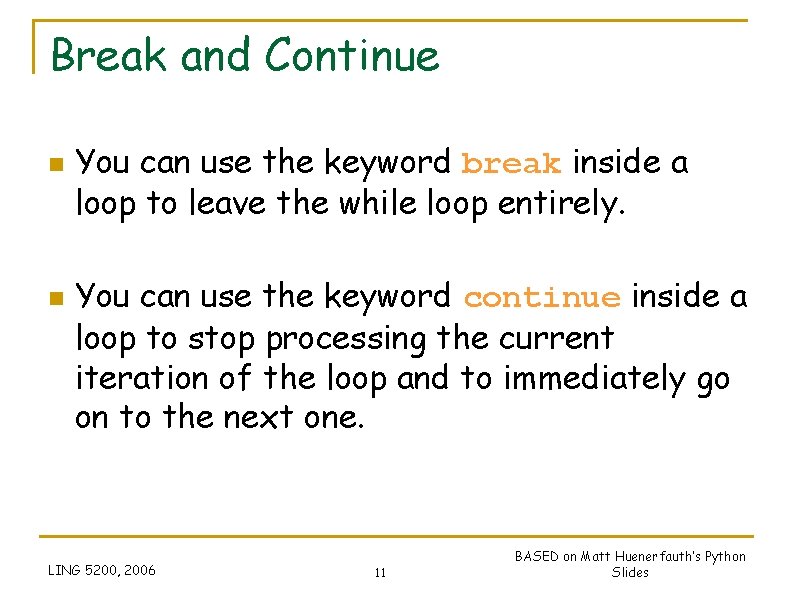

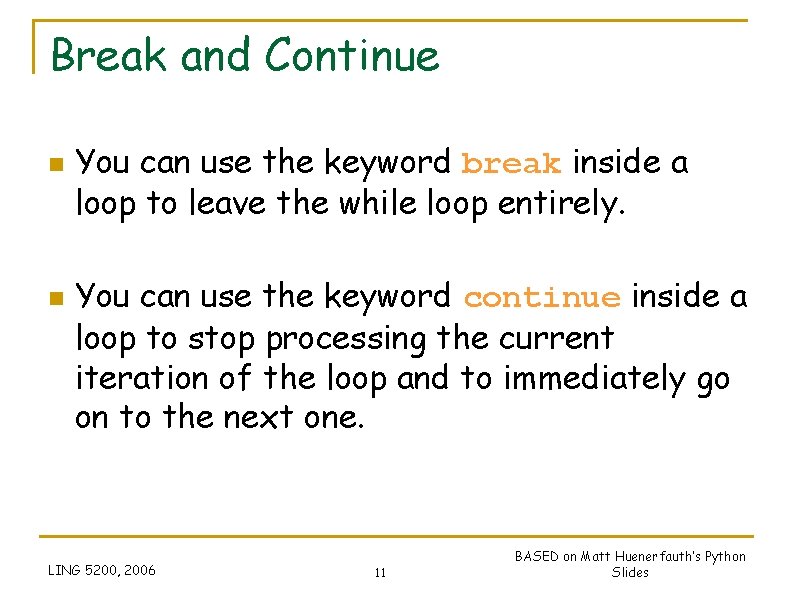

Break and Continue n n You can use the keyword break inside a loop to leave the while loop entirely. You can use the keyword continue inside a loop to stop processing the current iteration of the loop and to immediately go on to the next one. LING 5200, 2006 11 BASED on Matt Huenerfauth’s Python Slides

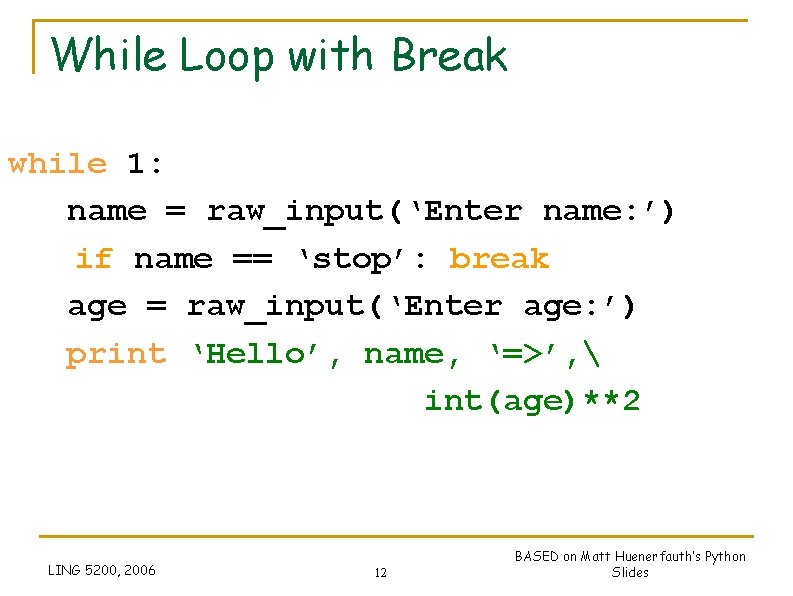

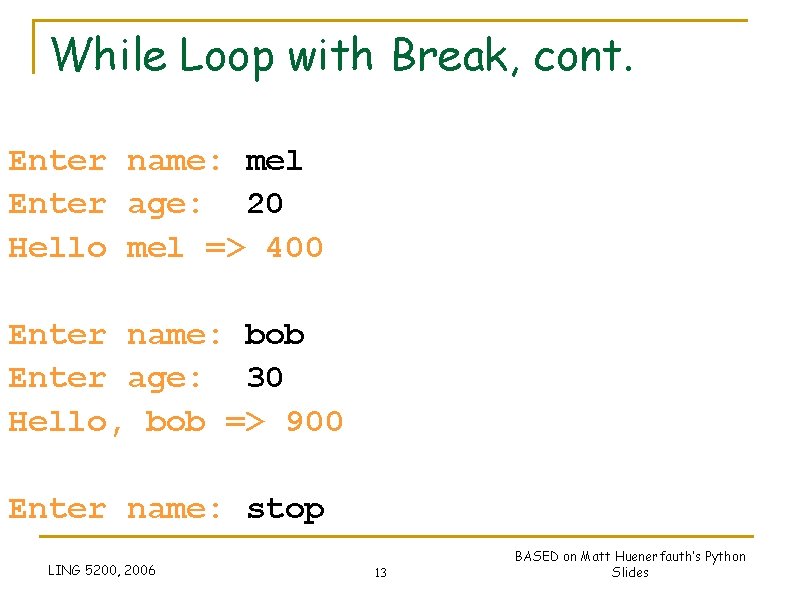

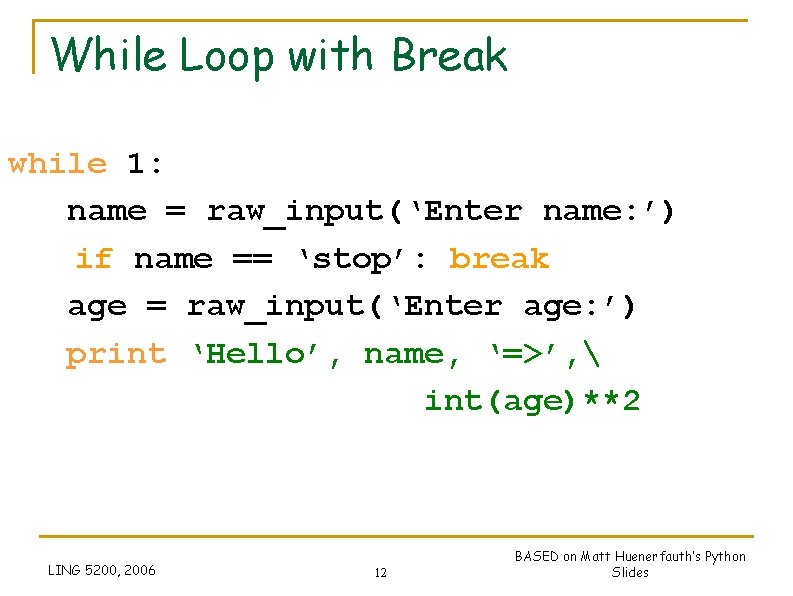

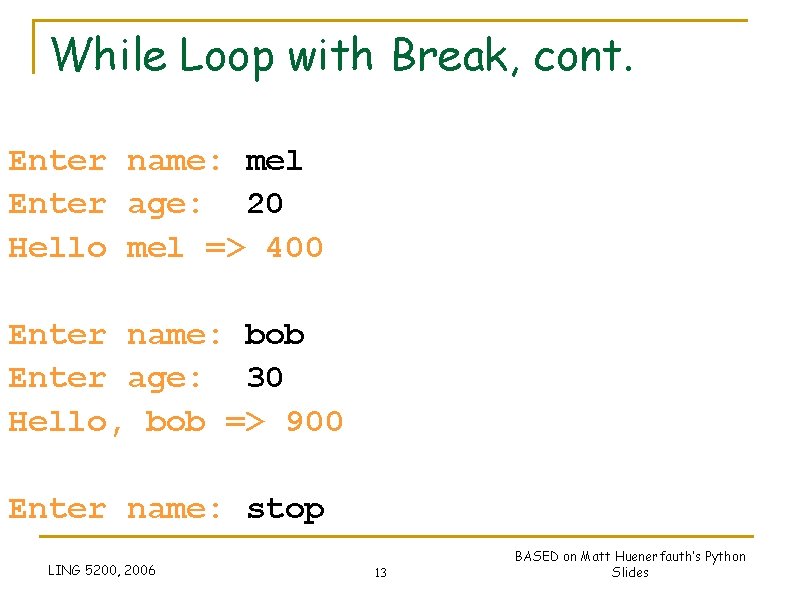

While Loop with Break while 1: name = raw_input(‘Enter name: ’) if name == ‘stop’: break age = raw_input(‘Enter age: ’) print ‘Hello’, name, ‘=>’, int(age)**2 LING 5200, 2006 12 BASED on Matt Huenerfauth’s Python Slides

While Loop with Break, cont. Enter name: mel Enter age: 20 Hello mel => 400 Enter name: bob Enter age: 30 Hello, bob => 900 Enter name: stop LING 5200, 2006 13 BASED on Matt Huenerfauth’s Python Slides

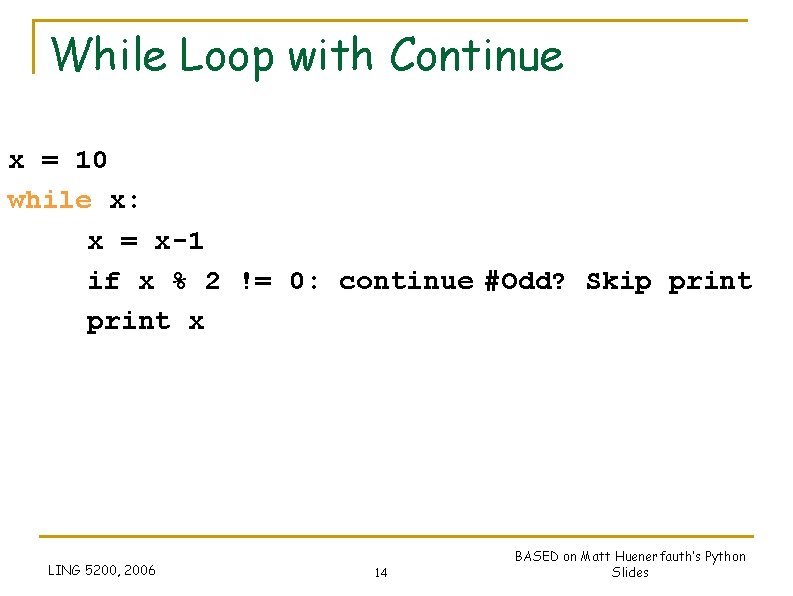

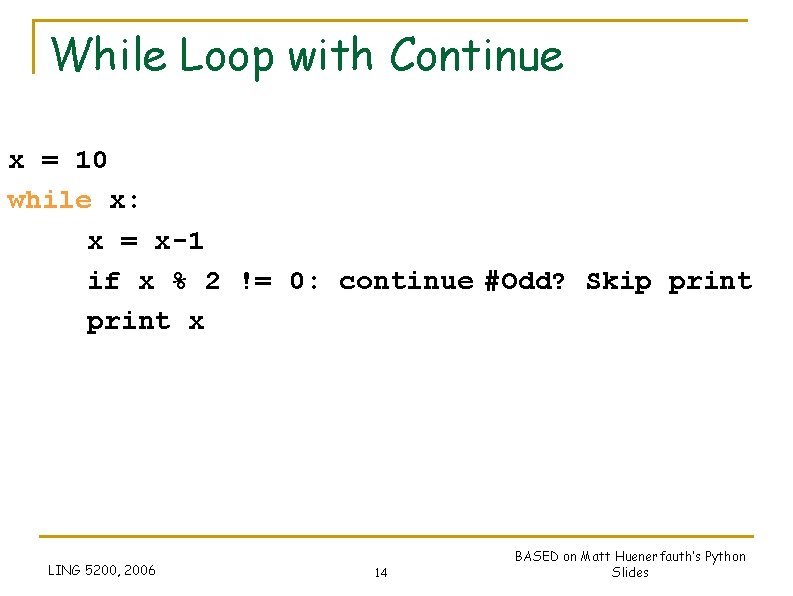

While Loop with Continue x = 10 while x: x = x-1 if x % 2 != 0: continue #Odd? Skip print x LING 5200, 2006 14 BASED on Matt Huenerfauth’s Python Slides

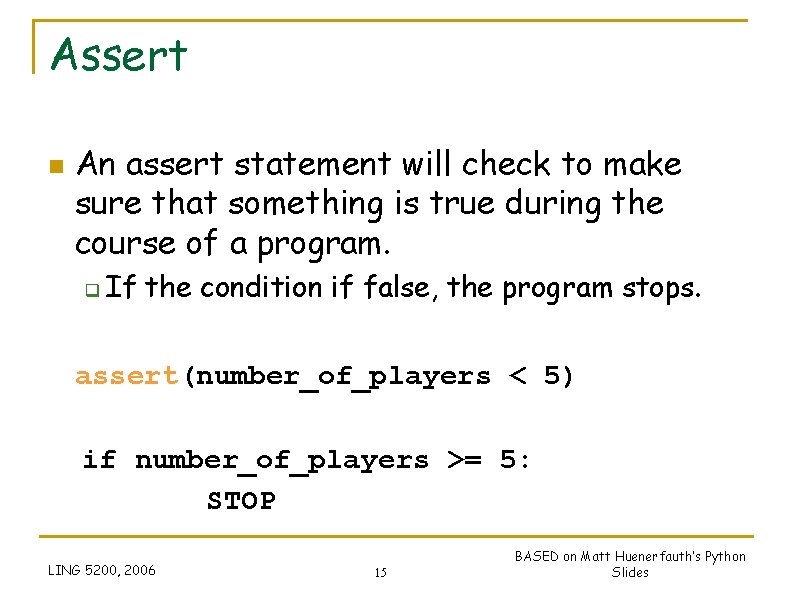

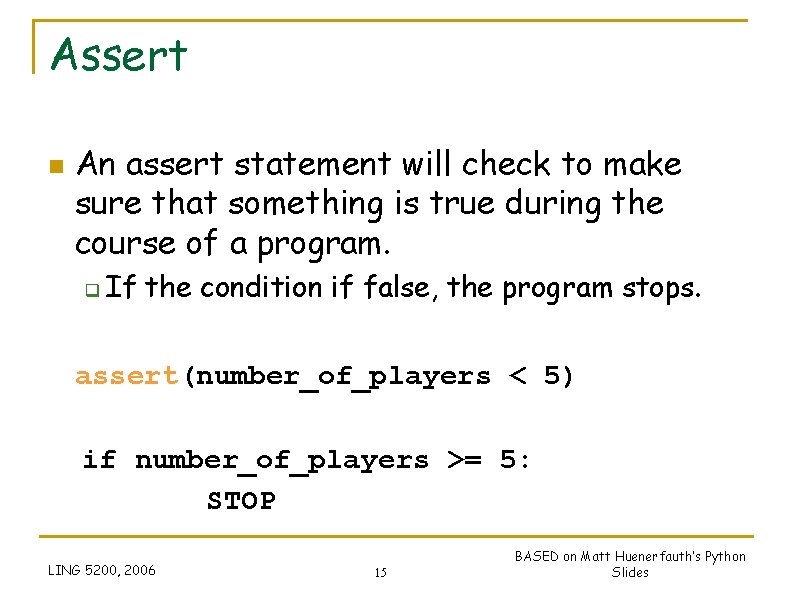

Assert n An assert statement will check to make sure that something is true during the course of a program. q If the condition if false, the program stops. assert(number_of_players < 5) if number_of_players >= 5: STOP LING 5200, 2006 15 BASED on Matt Huenerfauth’s Python Slides

Logical Expressions 16

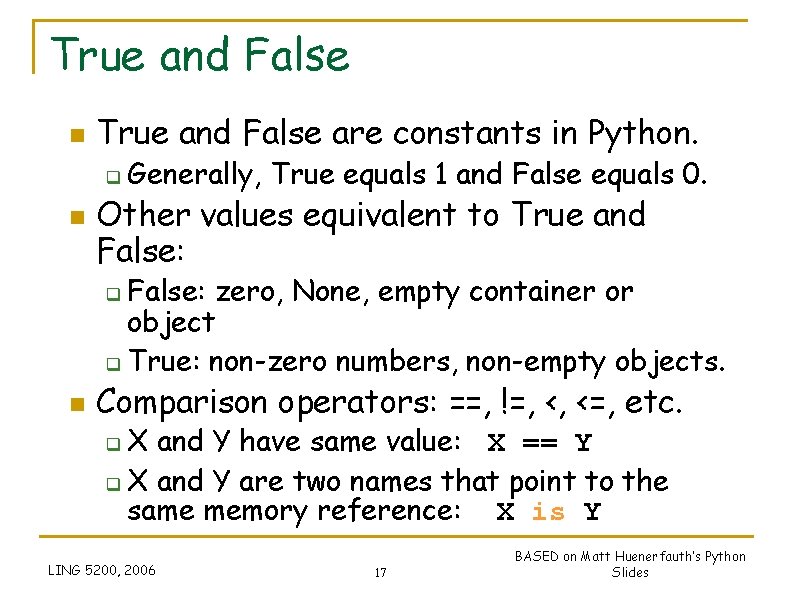

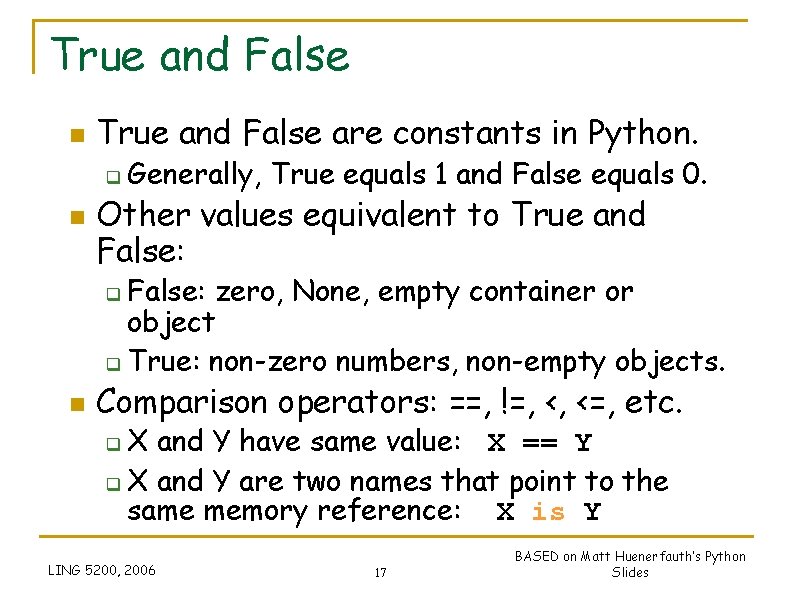

True and False n True and False are constants in Python. q n Generally, True equals 1 and False equals 0. Other values equivalent to True and False: zero, None, empty container or object q True: non-zero numbers, non-empty objects. q n Comparison operators: ==, !=, <, <=, etc. X and Y have same value: X == Y q X and Y are two names that point to the same memory reference: X is Y q LING 5200, 2006 17 BASED on Matt Huenerfauth’s Python Slides

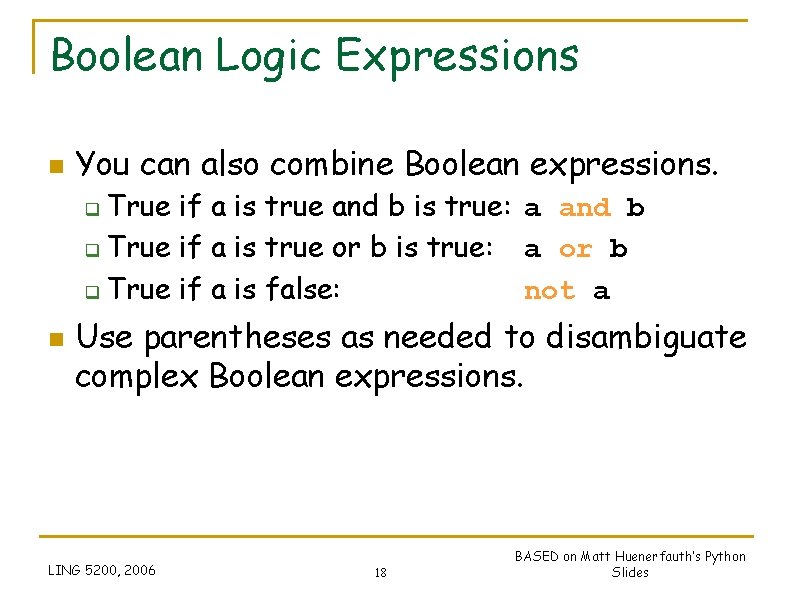

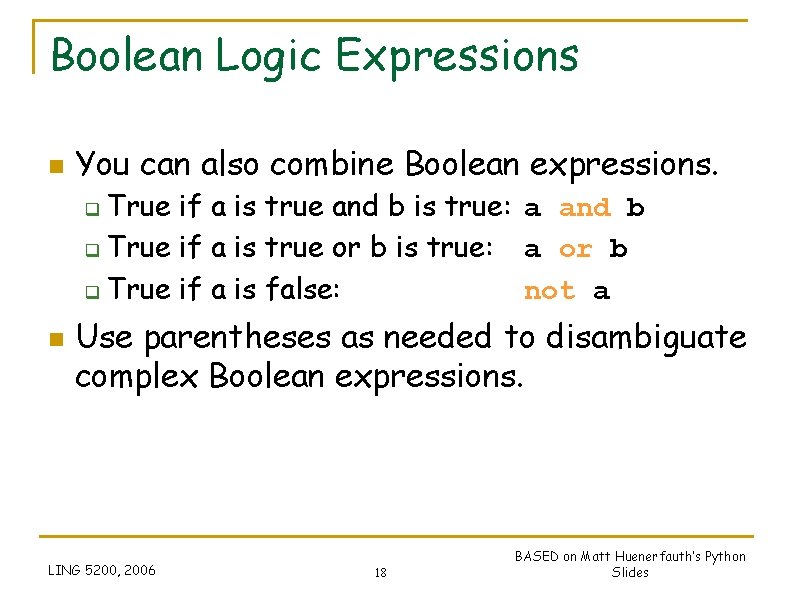

Boolean Logic Expressions n You can also combine Boolean expressions. True if a is true and b is true: a and b q True if a is true or b is true: a or b q True if a is false: not a q n Use parentheses as needed to disambiguate complex Boolean expressions. LING 5200, 2006 18 BASED on Matt Huenerfauth’s Python Slides

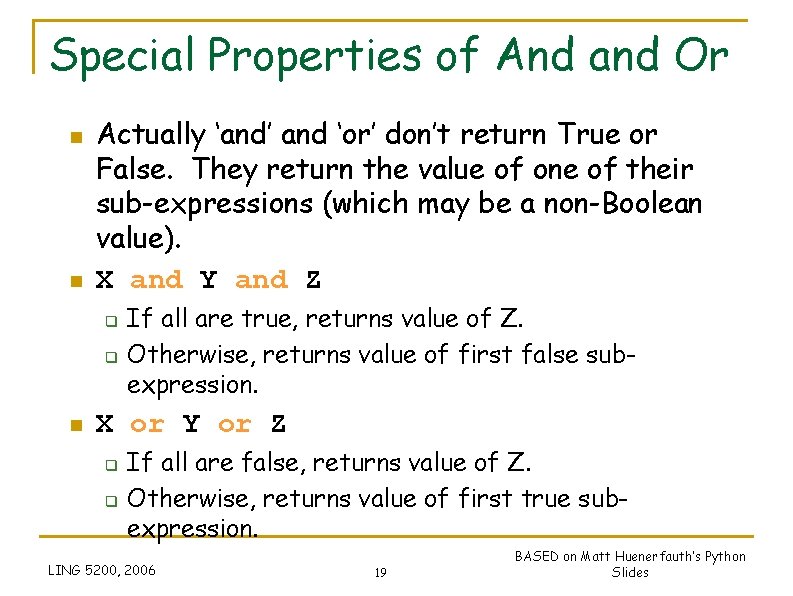

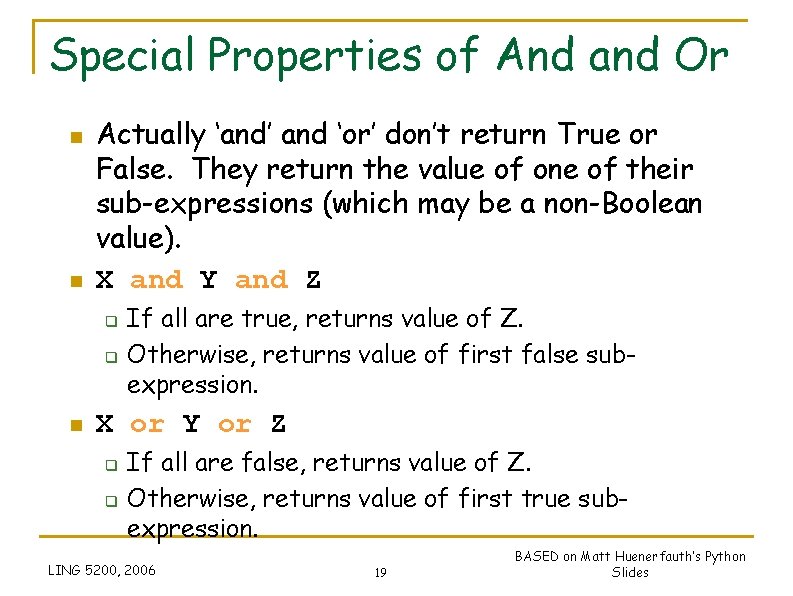

Special Properties of And and Or n n Actually ‘and’ and ‘or’ don’t return True or False. They return the value of one of their sub-expressions (which may be a non-Boolean value). X and Y and Z q q n If all are true, returns value of Z. Otherwise, returns value of first false subexpression. X or Y or Z q q If all are false, returns value of Z. Otherwise, returns value of first true subexpression. LING 5200, 2006 19 BASED on Matt Huenerfauth’s Python Slides

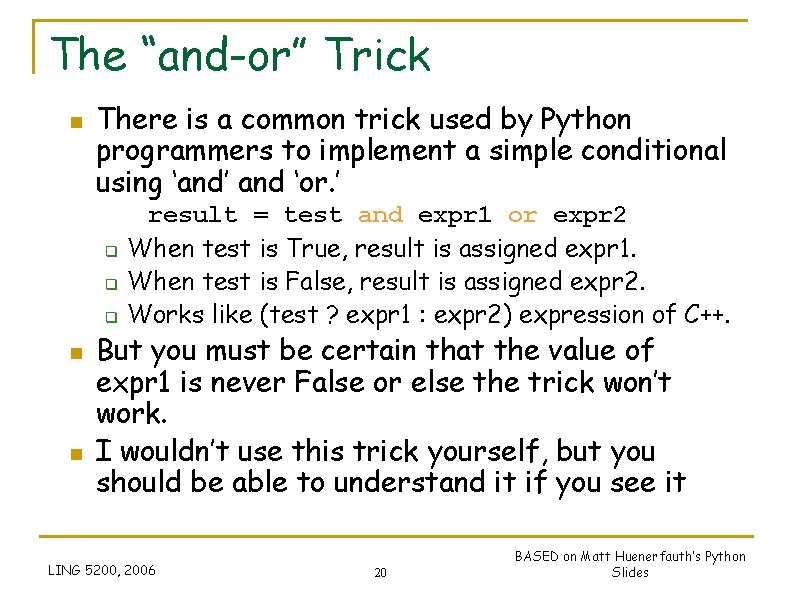

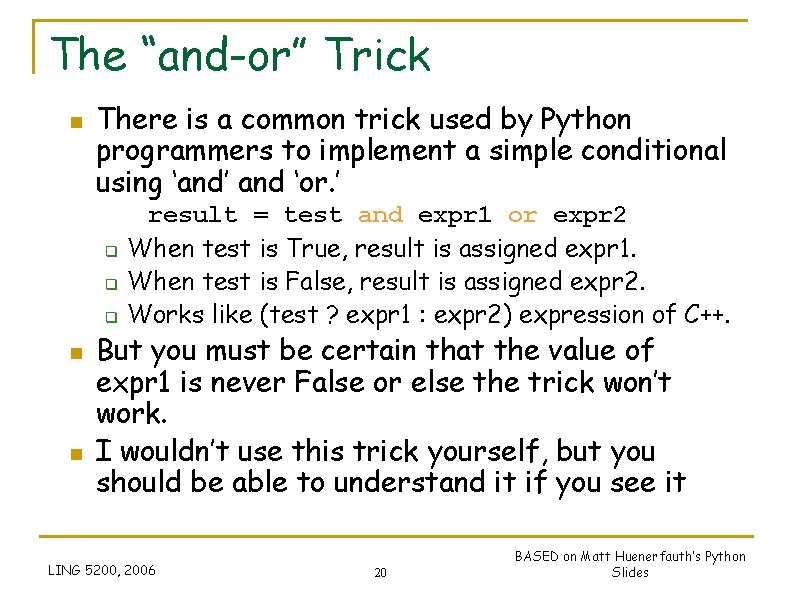

The “and-or” Trick n There is a common trick used by Python programmers to implement a simple conditional using ‘and’ and ‘or. ’ q q q n n result = test and expr 1 or expr 2 When test is True, result is assigned expr 1. When test is False, result is assigned expr 2. Works like (test ? expr 1 : expr 2) expression of C++. But you must be certain that the value of expr 1 is never False or else the trick won’t work. I wouldn’t use this trick yourself, but you should be able to understand it if you see it LING 5200, 2006 20 BASED on Matt Huenerfauth’s Python Slides

Object Oriented Programming in Python 21

It’s all objects… n Everything in Python is really an object. q q n We’ve seen hints of this already… “hello”. upper() list 3. append(‘a’) dict 2. keys() You can also design your own objects… in addition to these built-in data-types. In fact, programming in Python is typically done in an object oriented fashion. LING 5200, 2006 22 BASED on Matt Huenerfauth’s Python Slides

Defining Classes 23

Defining a Class n A class is a special data type which defines how to build a certain kind of object. The ‘class’ also stores some data items that are shared by all the instances of this class. q ‘Instances’ are objects that are created which follow the definition given inside of the class. q n Python doesn’t use separate class interface definitions as in some languages. You just define the class and then use it. LING 5200, 2006 24 BASED on Matt Huenerfauth’s Python Slides

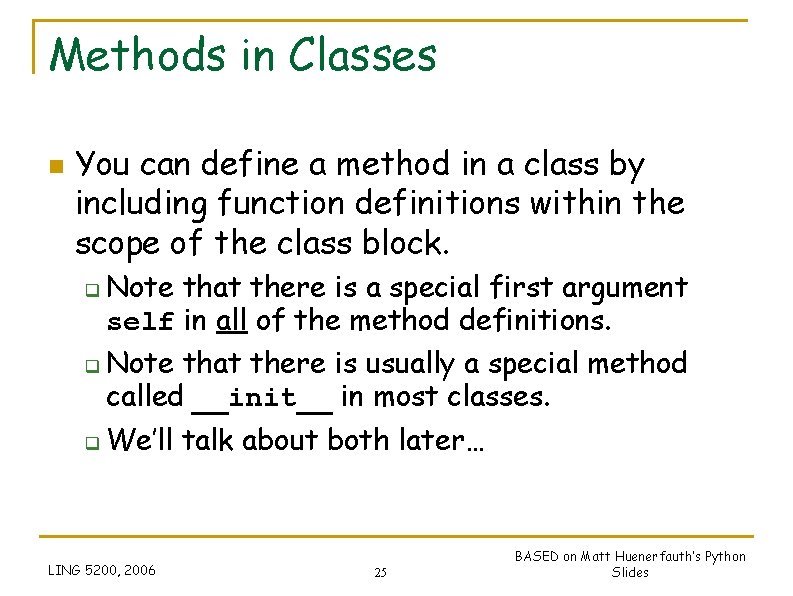

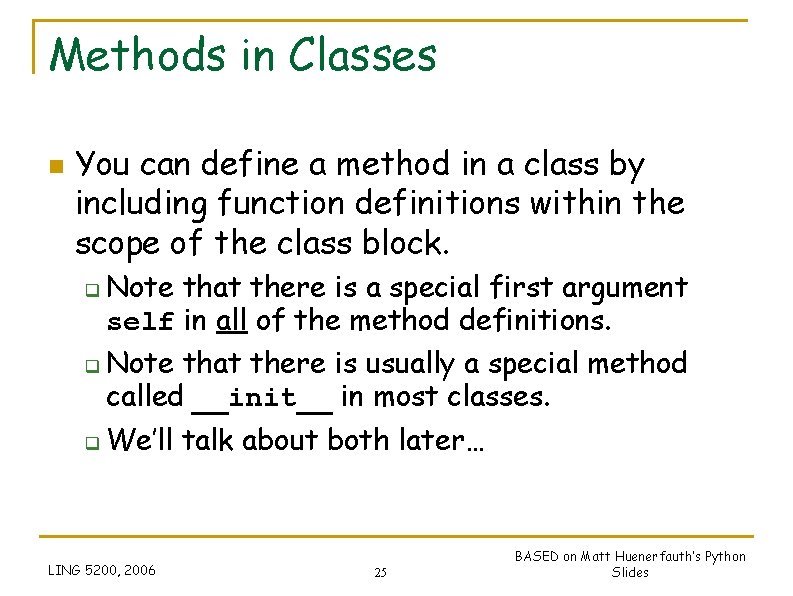

Methods in Classes n You can define a method in a class by including function definitions within the scope of the class block. q q q Note that there is a special first argument self in all of the method definitions. Note that there is usually a special method called __init__ in most classes. We’ll talk about both later… LING 5200, 2006 25 BASED on Matt Huenerfauth’s Python Slides

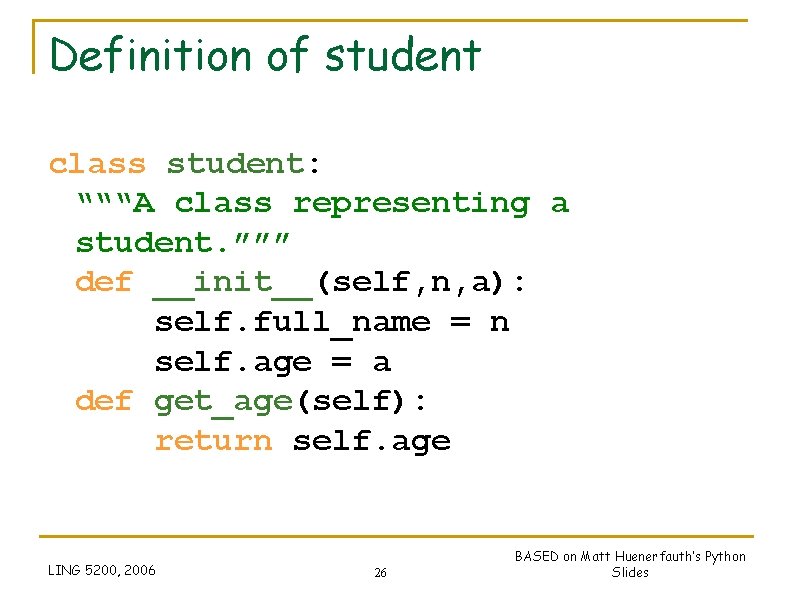

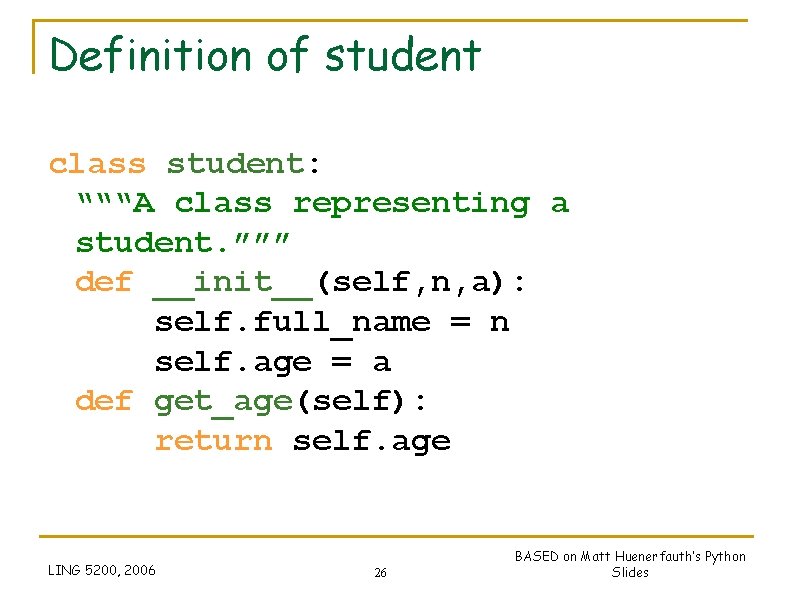

Definition of student class student: “““A class representing a student. ””” def __init__(self, n, a): self. full_name = n self. age = a def get_age(self): return self. age LING 5200, 2006 26 BASED on Matt Huenerfauth’s Python Slides

Creating and Deleting Instances 27

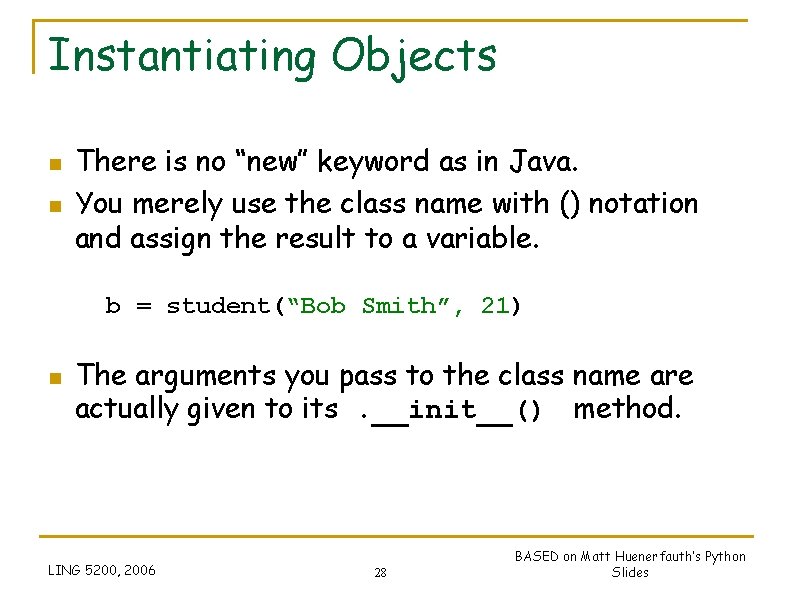

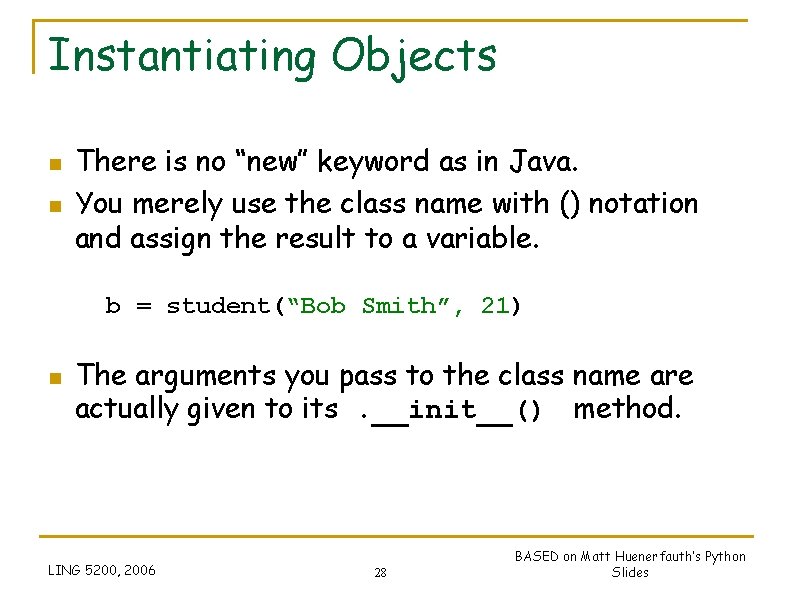

Instantiating Objects n n There is no “new” keyword as in Java. You merely use the class name with () notation and assign the result to a variable. b = student(“Bob Smith”, 21) n The arguments you pass to the class name are actually given to its. __init__() method. LING 5200, 2006 28 BASED on Matt Huenerfauth’s Python Slides

Constructor: __init__ n __init__ acts like a constructor for your class. q q When you create a new instance of a class, this method is invoked. Usually does some initialization work. The arguments you list when instantiating an instance of the class are passed along to the __init__ method. b = student(“Bob”, 21) So, the __init__ method is passed “Bob” and 21. LING 5200, 2006 29 BASED on Matt Huenerfauth’s Python Slides

Constructor: __init__ n Your __init__ method can take any number of arguments. q n Just like other functions or methods, the arguments can be defined with default values, making them optional to the caller. However, the first argument self in the definition of __init__ is special… LING 5200, 2006 30 BASED on Matt Huenerfauth’s Python Slides

Self n The first argument of every method is a reference to the current instance of the class. q n By convention, we name this argument self. In __init__, self refers to the object currently being created; so, in other class methods, it refers to the instance whose method was called. q q Similar to the keyword ‘this’ in Java or C++. But Python uses ‘self’ more often than Java uses ‘this. ’ LING 5200, 2006 31 BASED on Matt Huenerfauth’s Python Slides

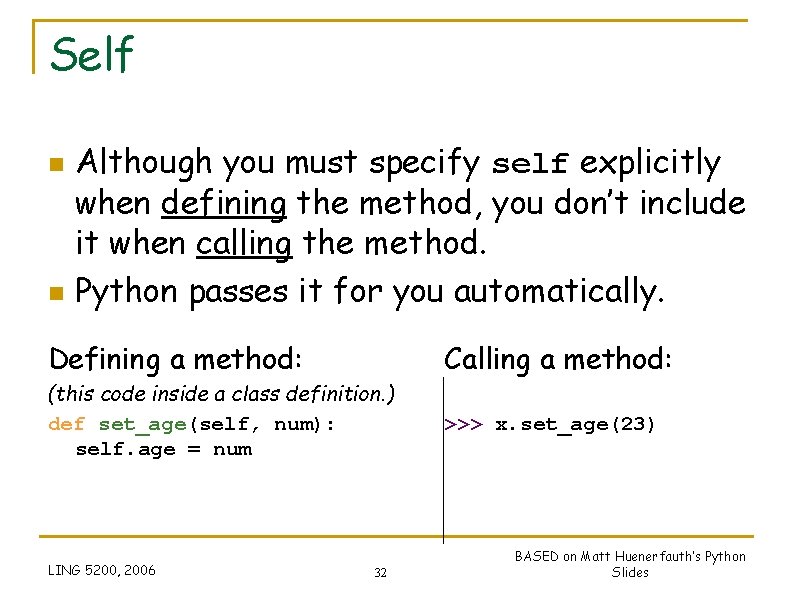

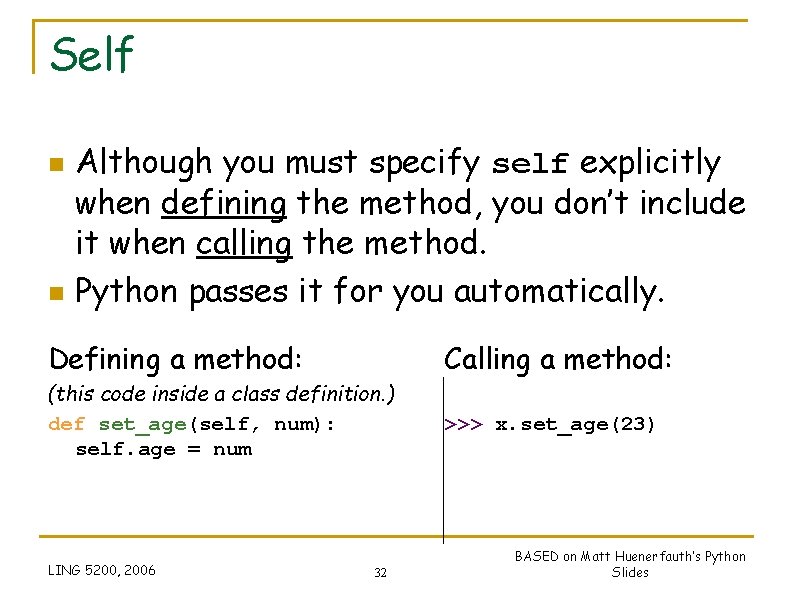

Self n n Although you must specify self explicitly when defining the method, you don’t include it when calling the method. Python passes it for you automatically. Defining a method: Calling a method: (this code inside a class definition. ) def set_age(self, num): self. age = num >>> x. set_age(23) LING 5200, 2006 32 BASED on Matt Huenerfauth’s Python Slides

No Need to “free” n When you are done with an object, you don’t have to delete or free it explicitly. Python has automatic garbage collection. q Python will automatically detect when all of the references to a piece of memory have gone out of scope. Automatically frees that memory. q Generally works well, few memory leaks. q There’s also no “destructor” method for classes. q LING 5200, 2006 33 BASED on Matt Huenerfauth’s Python Slides

Access to Attributes and Methods 34

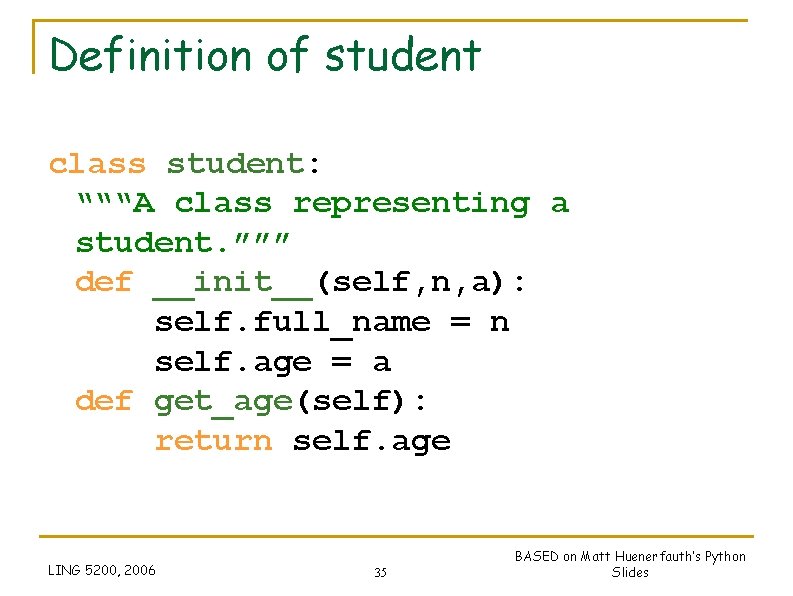

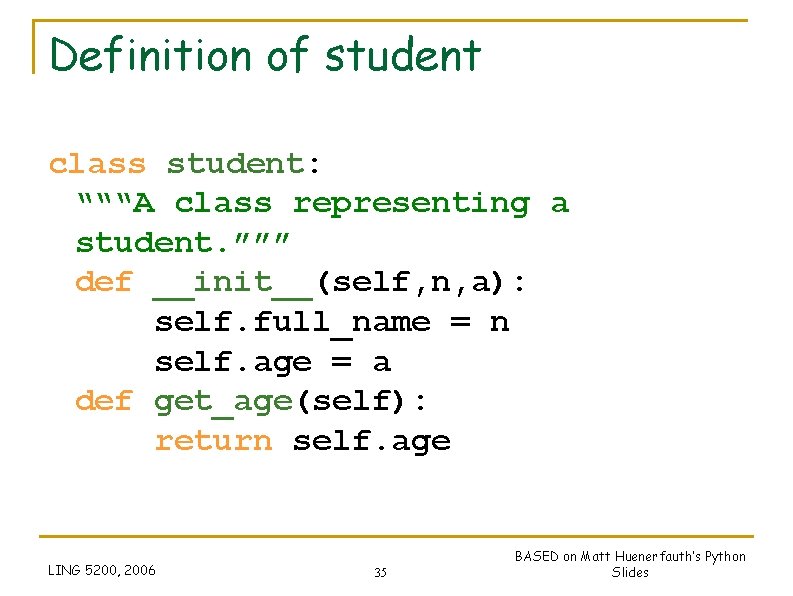

Definition of student class student: “““A class representing a student. ””” def __init__(self, n, a): self. full_name = n self. age = a def get_age(self): return self. age LING 5200, 2006 35 BASED on Matt Huenerfauth’s Python Slides

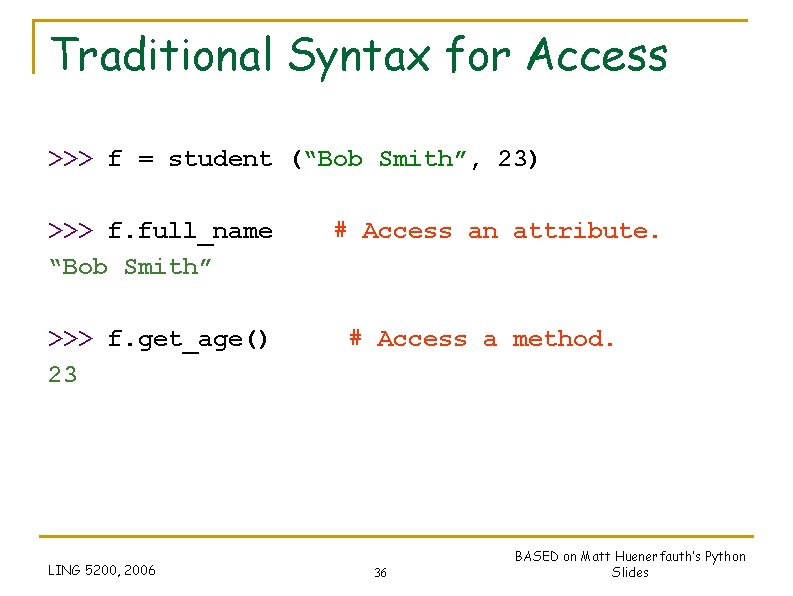

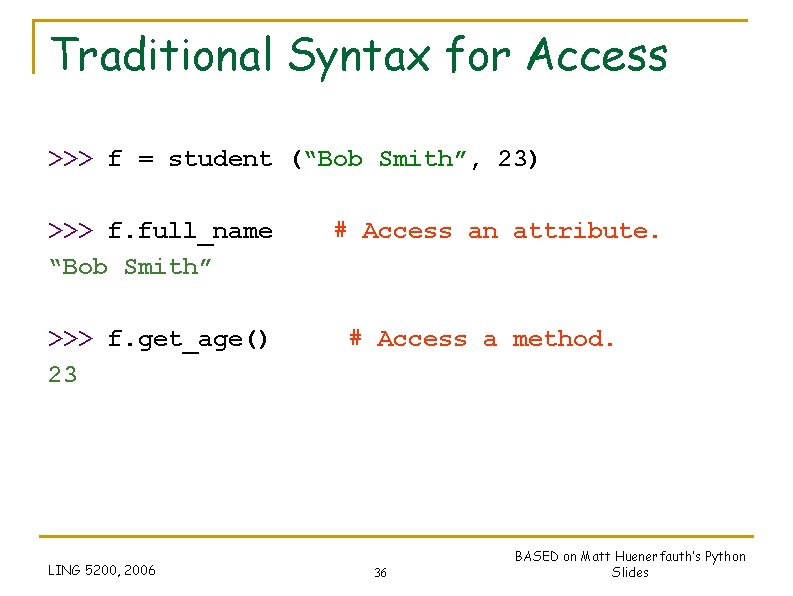

Traditional Syntax for Access >>> f = student (“Bob Smith”, 23) >>> f. full_name “Bob Smith” >>> f. get_age() 23 LING 5200, 2006 # Access an attribute. # Access a method. 36 BASED on Matt Huenerfauth’s Python Slides

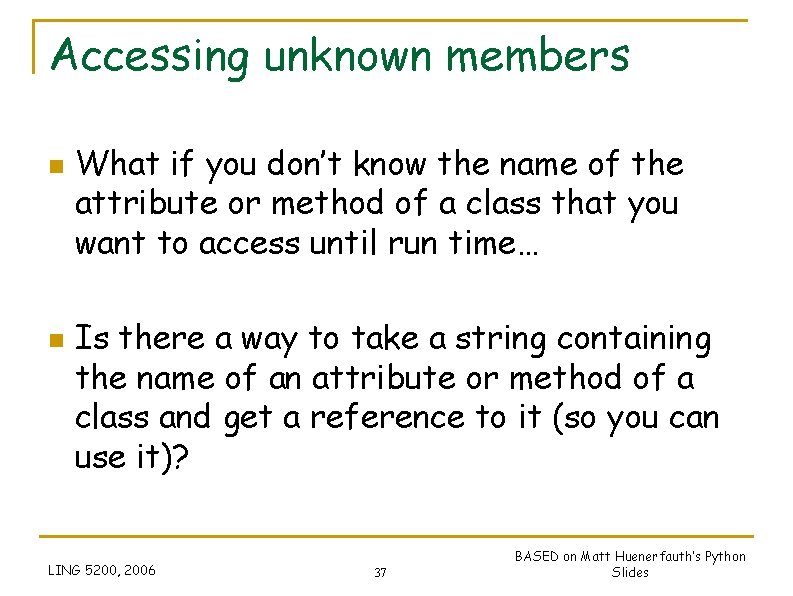

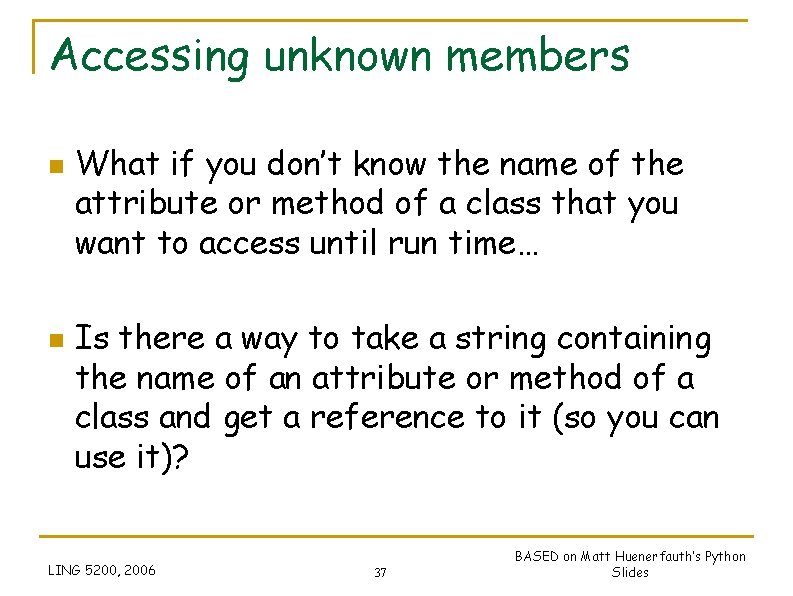

Accessing unknown members n n What if you don’t know the name of the attribute or method of a class that you want to access until run time… Is there a way to take a string containing the name of an attribute or method of a class and get a reference to it (so you can use it)? LING 5200, 2006 37 BASED on Matt Huenerfauth’s Python Slides

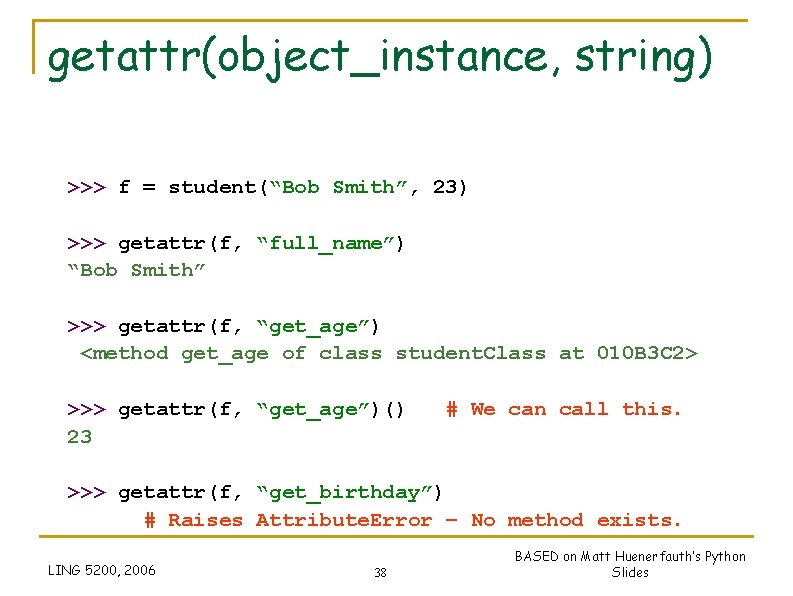

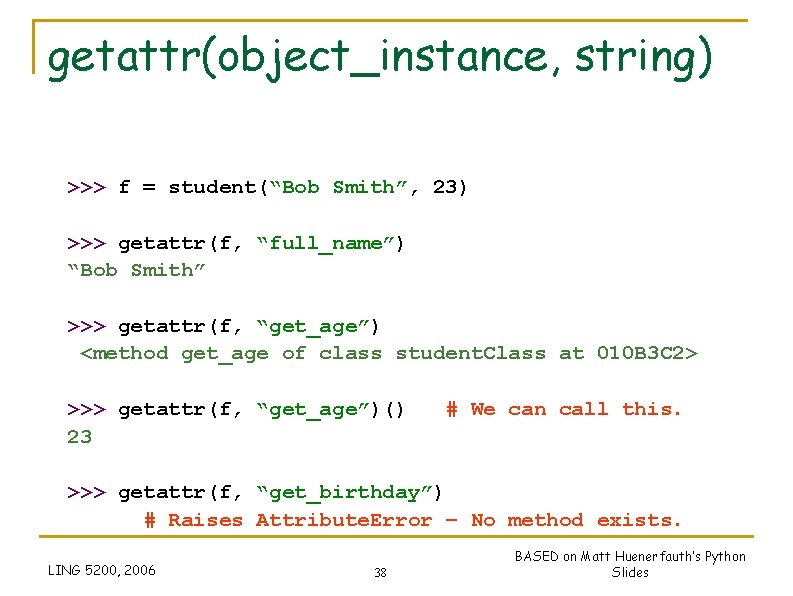

getattr(object_instance, string) >>> f = student(“Bob Smith”, 23) >>> getattr(f, “full_name”) “Bob Smith” >>> getattr(f, “get_age”) <method get_age of class student. Class at 010 B 3 C 2> >>> getattr(f, “get_age”)() 23 # We can call this. >>> getattr(f, “get_birthday”) # Raises Attribute. Error – No method exists. LING 5200, 2006 38 BASED on Matt Huenerfauth’s Python Slides

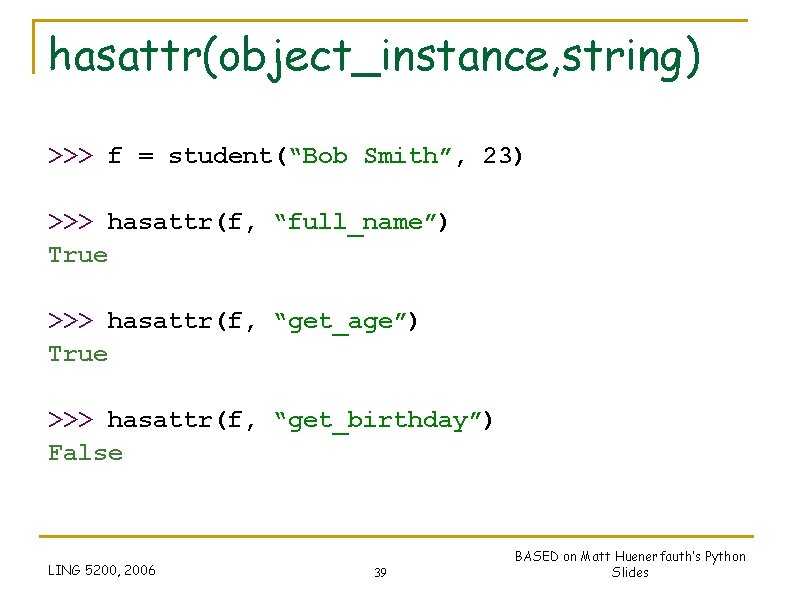

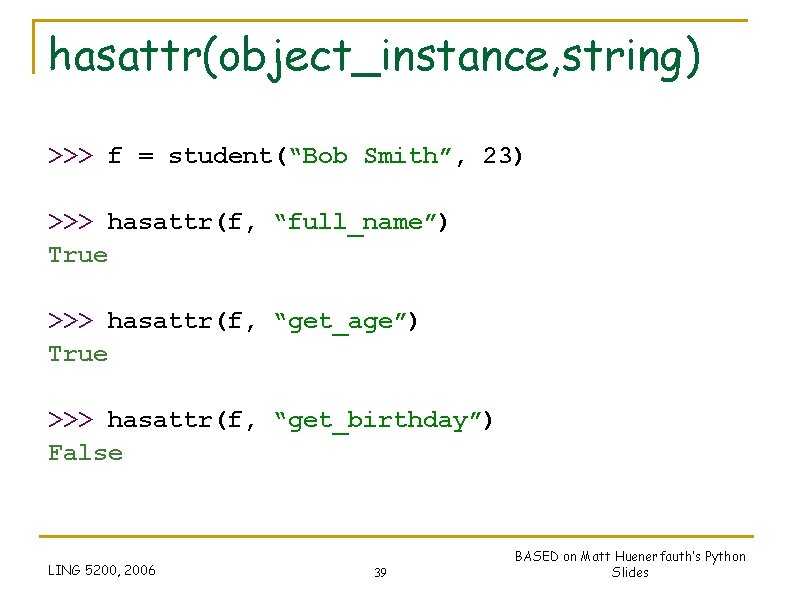

hasattr(object_instance, string) >>> f = student(“Bob Smith”, 23) >>> hasattr(f, “full_name”) True >>> hasattr(f, “get_age”) True >>> hasattr(f, “get_birthday”) False LING 5200, 2006 39 BASED on Matt Huenerfauth’s Python Slides

Attributes 40

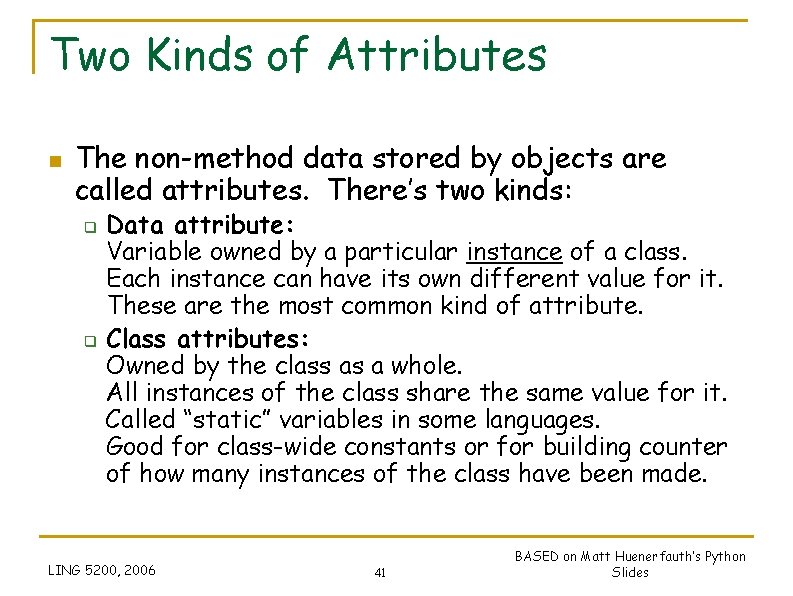

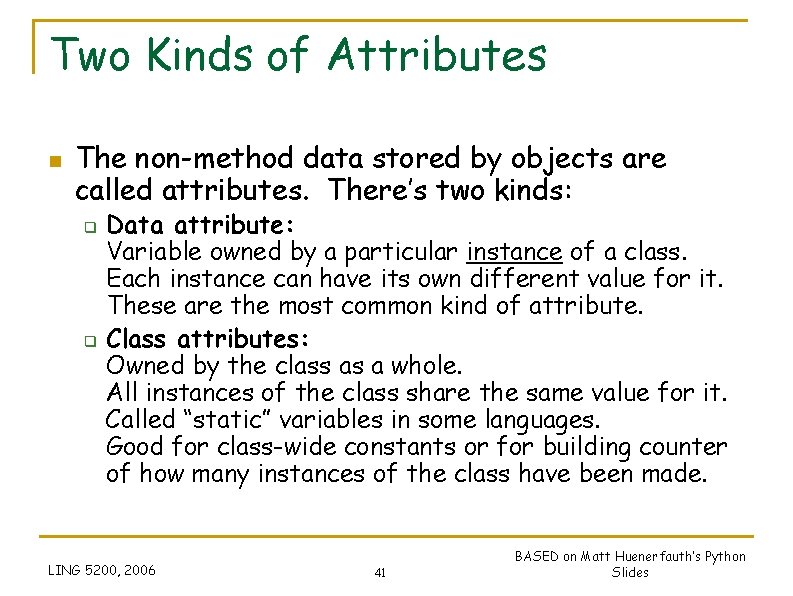

Two Kinds of Attributes n The non-method data stored by objects are called attributes. There’s two kinds: q q Data attribute: Variable owned by a particular instance of a class. Each instance can have its own different value for it. These are the most common kind of attribute. Class attributes: Owned by the class as a whole. All instances of the class share the same value for it. Called “static” variables in some languages. Good for class-wide constants or for building counter of how many instances of the class have been made. LING 5200, 2006 41 BASED on Matt Huenerfauth’s Python Slides

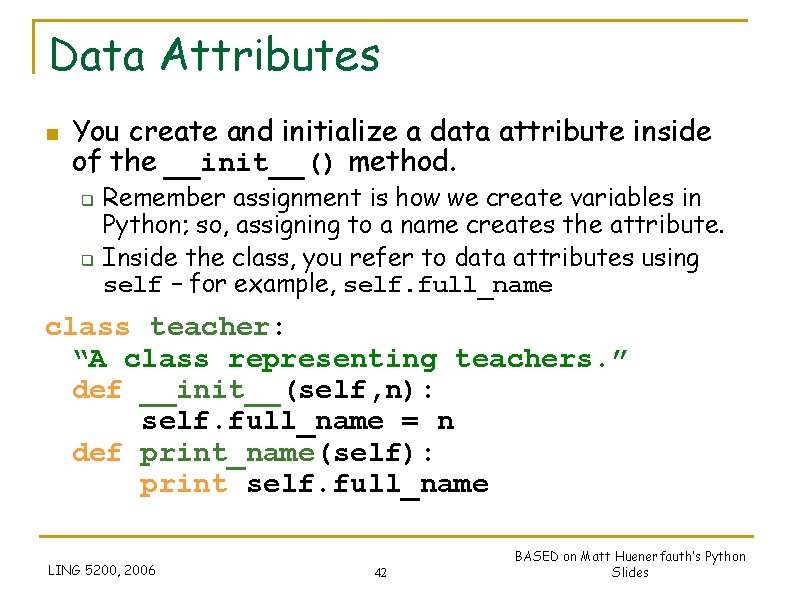

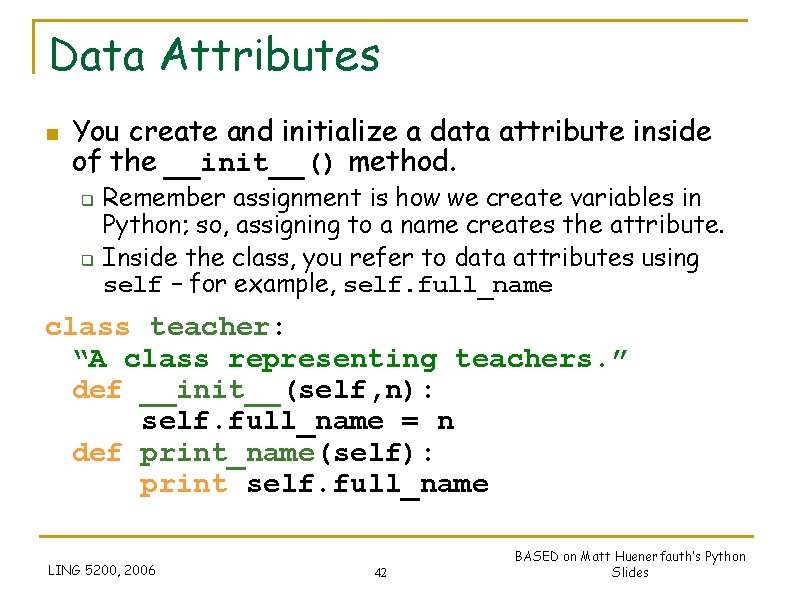

Data Attributes n You create and initialize a data attribute inside of the __init__() method. q q Remember assignment is how we create variables in Python; so, assigning to a name creates the attribute. Inside the class, you refer to data attributes using self – for example, self. full_name class teacher: “A class representing teachers. ” def __init__(self, n): self. full_name = n def print_name(self): print self. full_name LING 5200, 2006 42 BASED on Matt Huenerfauth’s Python Slides

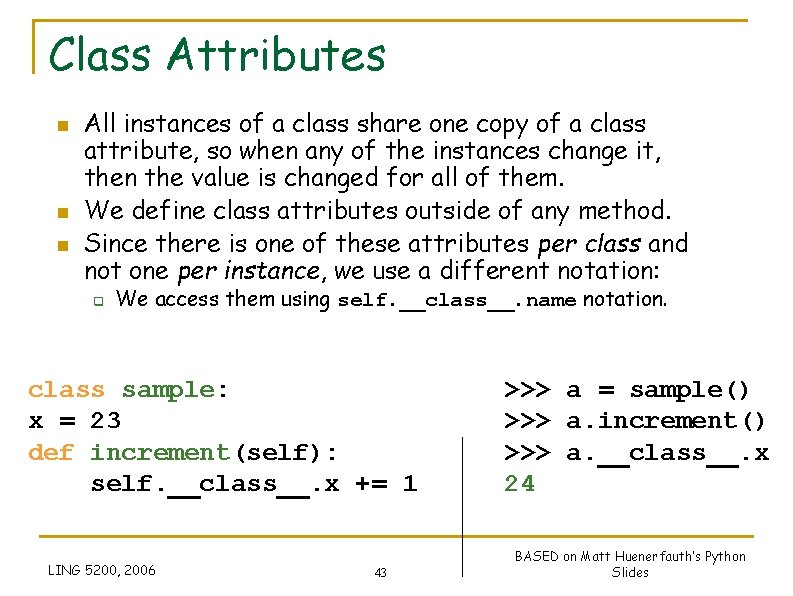

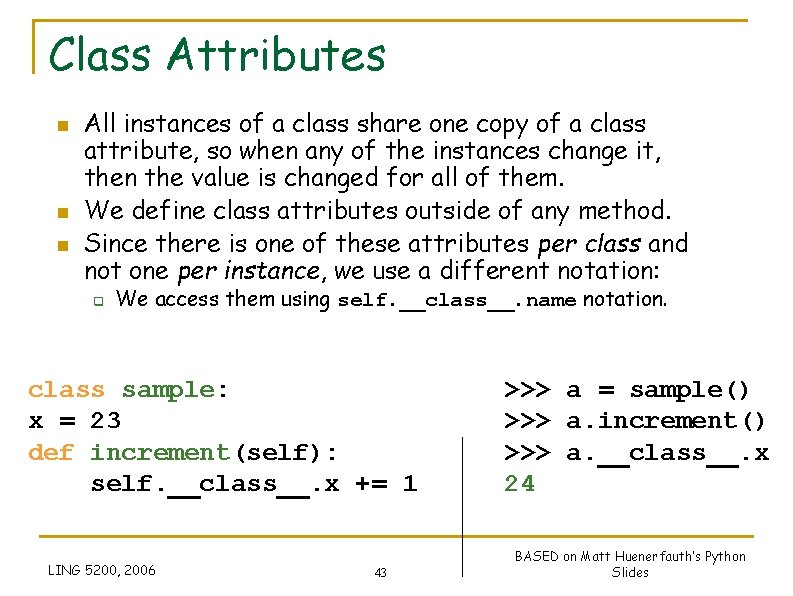

Class Attributes n n n All instances of a class share one copy of a class attribute, so when any of the instances change it, then the value is changed for all of them. We define class attributes outside of any method. Since there is one of these attributes per class and not one per instance, we use a different notation: q We access them using self. __class__. name notation. class sample: x = 23 def increment(self): self. __class__. x += 1 LING 5200, 2006 43 >>> a = sample() >>> a. increment() >>> a. __class__. x 24 BASED on Matt Huenerfauth’s Python Slides

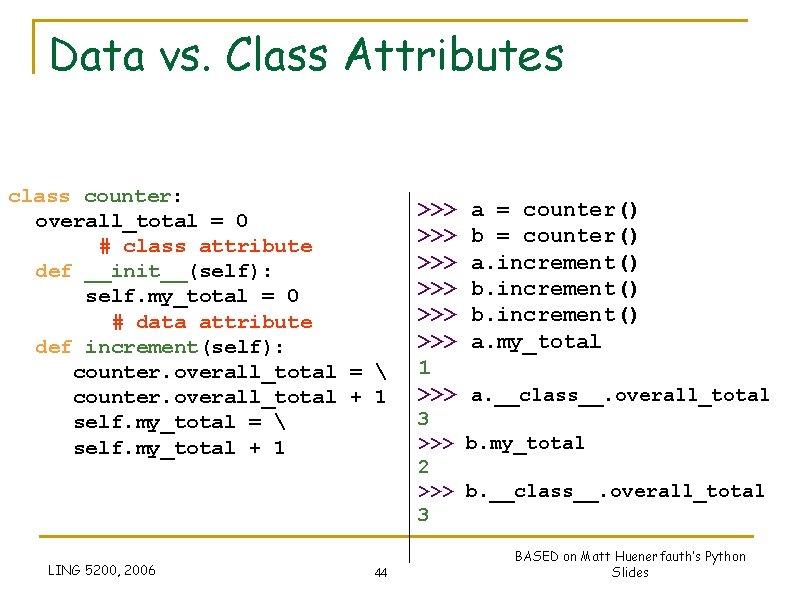

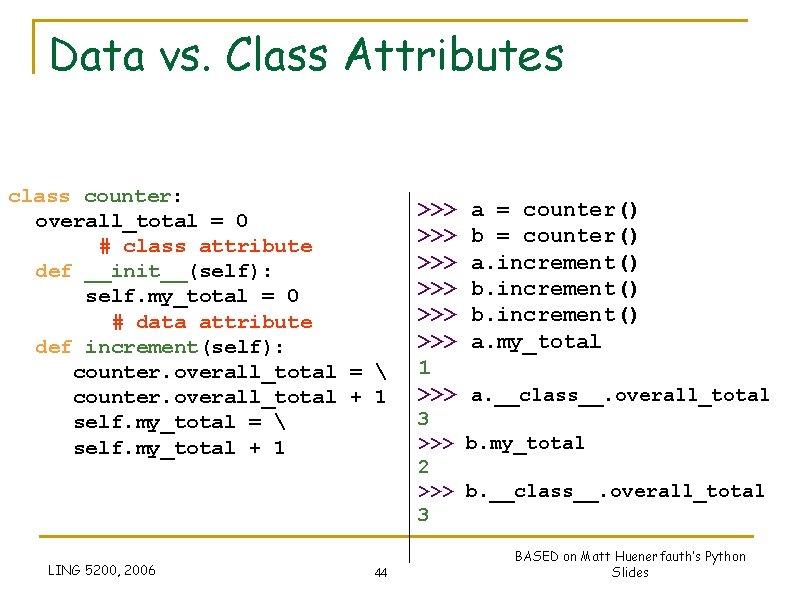

Data vs. Class Attributes class counter: overall_total = 0 # class attribute def __init__(self): self. my_total = 0 # data attribute def increment(self): counter. overall_total = counter. overall_total + 1 self. my_total = self. my_total + 1 LING 5200, 2006 44 >>> >>> >>> 1 >>> a = counter() b = counter() a. increment() b. increment() a. my_total a. __class__. overall_total 3 >>> b. my_total 2 >>> b. __class__. overall_total 3 BASED on Matt Huenerfauth’s Python Slides