Public Expenditure Tracking Surveys Rationale Results and Country

Public Expenditure Tracking Surveys: Rationale, Results, and Country Cases Oscar F. Picazo Sr. Economist, The World Bank Presentation for the WBI/CABRI Training Seminar on PFM in Sub-Saharan Africa Pretoria, South Africa June 20, 2007

What is PETS? (Oxford Policy Management, 2006) Ø PETS is a diagnostic tool that tracks resource flows from central government through line ministries (e. g. , MOH) and intermediary administrative levels (provinces, districts) to the service delivery unit (e. g. , hospital or clinic). l l l Budget allocations, timeliness of funding, local discretion in use of resources, degree of leakage Comparison of resources at each level (if possible, vis -à-vis performance); reasons for variances Assessment of “fiduciary risk” – risk that resources are not accounted for, or are not used for intended purposes

Why PETS (health focus)? Ø Some countries are already approaching or have exceeded the CMH’s standard of US$33 per capita health spending, yet health indicators are still poor l Ø Some countries now exceed the 15% Abuja target of gov’t allocation to health, yet health indicators are still poor l Ø Botswana, $171; Lesotho, $29; Namibia, $99; South Africa, $206; Swaziland, $66 DR Congo, 16%; Mozambique, 20%; Namibia, ~20%; Tanzania, 15%; Sao Tome & Principe, 15% Large external infusion of health resources (GF, GAVI, WB, PEPFAR, etc. ) are yet to demonstrate equally large improvement in health outcomes

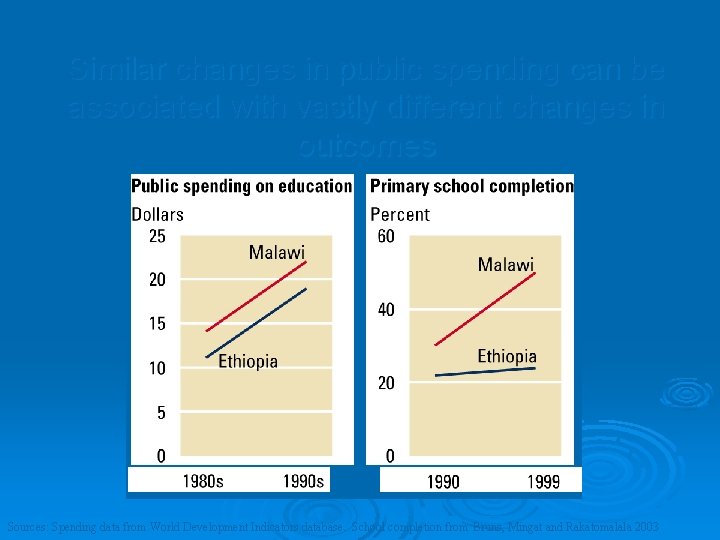

Similar changes in public spending can be associated with vastly different changes in outcomes Sources: Spending data from World Development Indicators database. School completion from Bruns, Mingat and Rakatomalala 2003

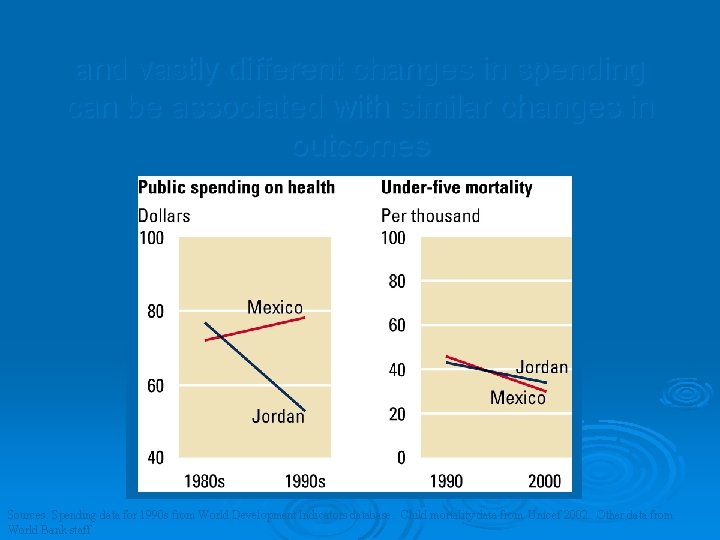

and vastly different changes in spending can be associated with similar changes in outcomes Sources: Spending data for 1990 s from World Development Indicators database. Child mortality data from Unicef 2002. Other data from World Bank staff

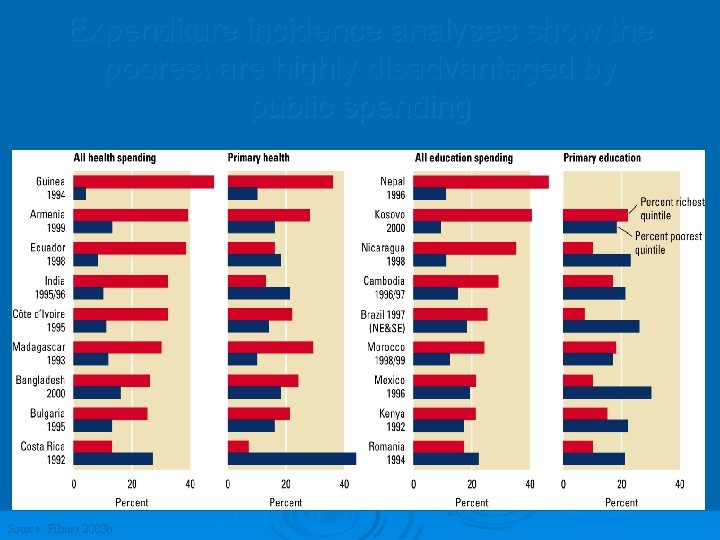

Expenditure incidence analyses show the poorest are highly disadvantaged by public spending Health Education Source: Filmer 2003 b

PETS Rationale – the need for a new tool to analyze health spending and service delivery (Reinikka, 2005) Evidence of limited impact of health spending on health coverage and outcomes Ø Traditional focus of inquiry has been on household data (DHS) and demand-side analysis, and little inquiry on supply side (how financing translates into actual service provision) Ø Global and local demand for evidence of efficiency and quality of service delivery (what works? what doesn’t? why? ) Ø Lack of reliable disaggregated data in countries with poor governance and weak institutions Ø

PETS also impelled by new approaches to development aid (Adapted from Reinikka, 2005; OPM, 2006) Move towards budget support and PRSCs – If donors have to put their assistance into the budget and give up control of management of inputs (as in projects), they need to be confident that the money is being used for their intended purposes (i. e. , minimal fiduciary risk) Ø Output-based aid – Health sector is being asked to account for its performance and outcomes, esp. in MDGs; PETS can provide critical M&E function Ø Transparency and accountability – Global agencies and local constituencies are demanding stronger fiduciary and performance systems Ø l l PETS as a diagnostic tool to identify weak areas PETS can lead to practical solutions to address weak areas

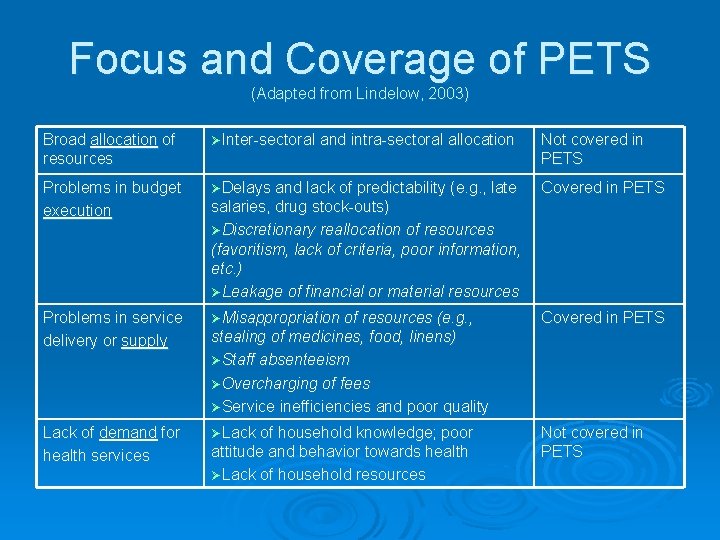

Focus and Coverage of PETS (Adapted from Lindelow, 2003) Broad allocation of resources ØInter-sectoral and intra-sectoral allocation Not covered in PETS Problems in budget execution ØDelays and lack of predictability (e. g. , late Covered in PETS Problems in service delivery or supply ØMisappropriation of resources (e. g. , Lack of demand for health services ØLack of household knowledge; poor salaries, drug stock-outs) ØDiscretionary reallocation of resources (favoritism, lack of criteria, poor information, etc. ) ØLeakage of financial or material resources Covered in PETS stealing of medicines, food, linens) ØStaff absenteeism ØOvercharging of fees ØService inefficiencies and poor quality attitude and behavior towards health ØLack of household resources Not covered in PETS

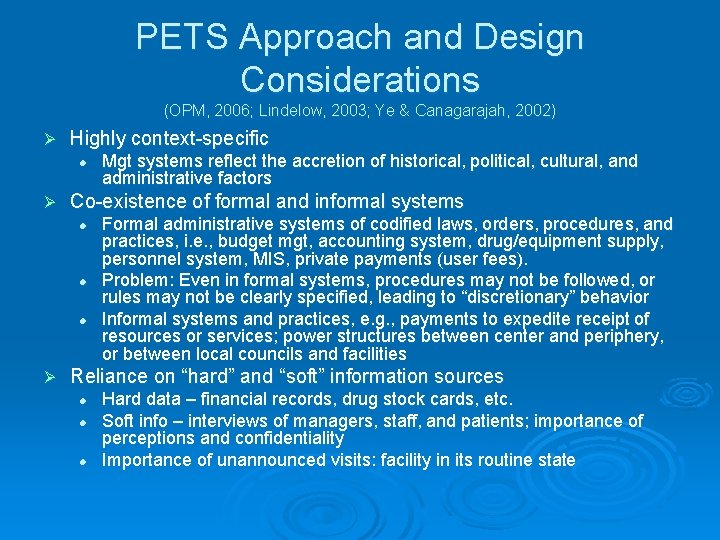

PETS Approach and Design Considerations (OPM, 2006; Lindelow, 2003; Ye & Canagarajah, 2002) Ø Highly context-specific l Ø Co-existence of formal and informal systems l l l Ø Mgt systems reflect the accretion of historical, political, cultural, and administrative factors Formal administrative systems of codified laws, orders, procedures, and practices, i. e. , budget mgt, accounting system, drug/equipment supply, personnel system, MIS, private payments (user fees). Problem: Even in formal systems, procedures may not be followed, or rules may not be clearly specified, leading to “discretionary” behavior Informal systems and practices, e. g. , payments to expedite receipt of resources or services; power structures between center and periphery, or between local councils and facilities Reliance on “hard” and “soft” information sources l l l Hard data – financial records, drug stock cards, etc. Soft info – interviews of managers, staff, and patients; importance of perceptions and confidentiality Importance of unannounced visits: facility in its routine state

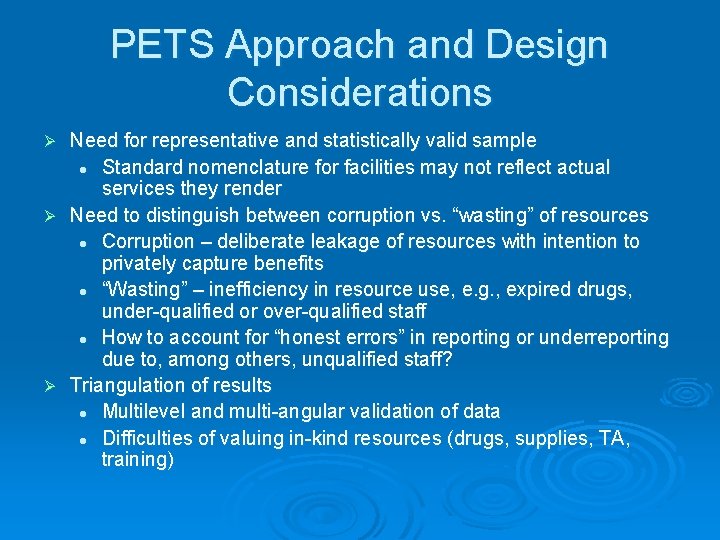

PETS Approach and Design Considerations Need for representative and statistically valid sample l Standard nomenclature for facilities may not reflect actual services they render Ø Need to distinguish between corruption vs. “wasting” of resources l Corruption – deliberate leakage of resources with intention to privately capture benefits l “Wasting” – inefficiency in resource use, e. g. , expired drugs, under-qualified or over-qualified staff l How to account for “honest errors” in reporting or underreporting due to, among others, unqualified staff? Ø Triangulation of results l Multilevel and multi-angular validation of data l Difficulties of valuing in-kind resources (drugs, supplies, TA, training) Ø

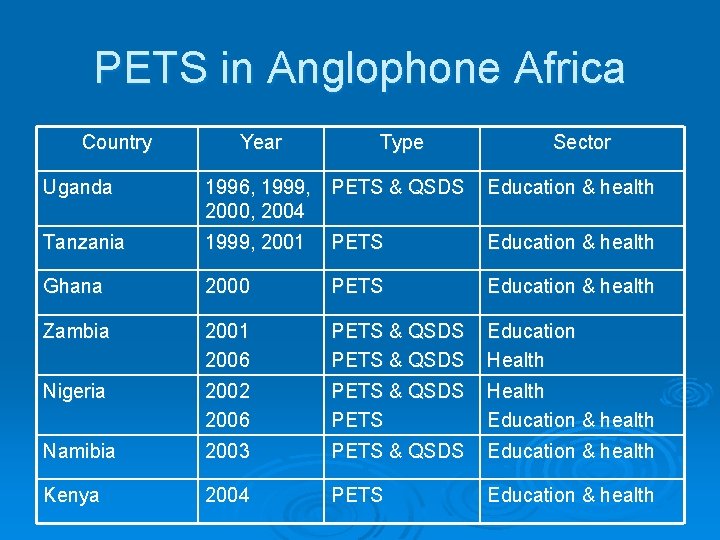

PETS in Anglophone Africa Country Year Type Sector Uganda 1996, 1999, PETS & QSDS 2000, 2004 Education & health Tanzania 1999, 2001 PETS Education & health Ghana 2000 PETS Education & health Zambia 2001 2006 PETS & QSDS Education Health Nigeria 2002 2006 PETS & QSDS PETS Health Education & health Namibia 2003 PETS & QSDS Education & health Kenya 2004 PETS Education & health

PETS in Francophone & Lusophone Africa Country Year Type Sector Rwanda 2000, 2004 PETS Education & health S. Leone 2000, 2001 PETS 6 sectors Mozambique 2002 PETS & QSDS Health Senegal 2002 PETS Health Cameroon 2003 2004 PETS Health Education Madagascar 2003 2005 PETS & QSDS Education PETS & QSDS Health Chad 2004 PETS & QSDS Health Mali 2005 PETS & QSDS Health & education

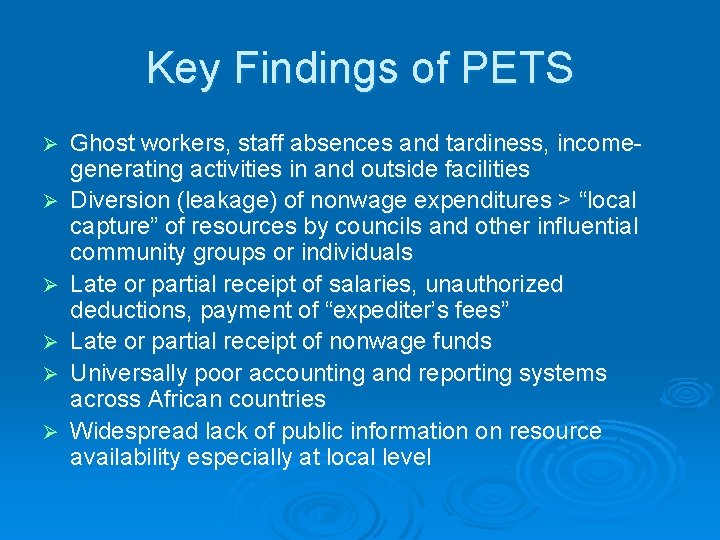

Key Findings of PETS Ø Ø Ø Ghost workers, staff absences and tardiness, incomegenerating activities in and outside facilities Diversion (leakage) of nonwage expenditures > “local capture” of resources by councils and other influential community groups or individuals Late or partial receipt of salaries, unauthorized deductions, payment of “expediter’s fees” Late or partial receipt of nonwage funds Universally poor accounting and reporting systems across African countries Widespread lack of public information on resource availability especially at local level

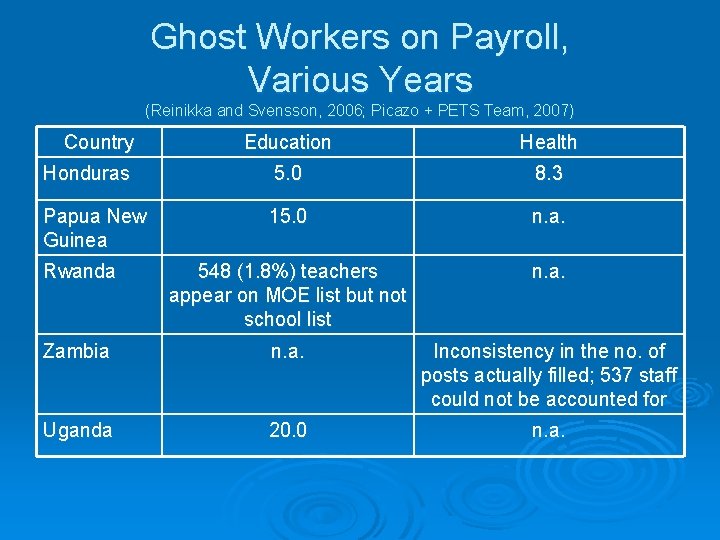

Ghost Workers on Payroll, Various Years (Reinikka and Svensson, 2006; Picazo + PETS Team, 2007) Country Education Health Honduras 5. 0 8. 3 Papua New Guinea 15. 0 n. a. Rwanda 548 (1. 8%) teachers appear on MOE list but not school list n. a. Zambia n. a. Inconsistency in the no. of posts actually filled; 537 staff could not be accounted for Uganda 20. 0 n. a.

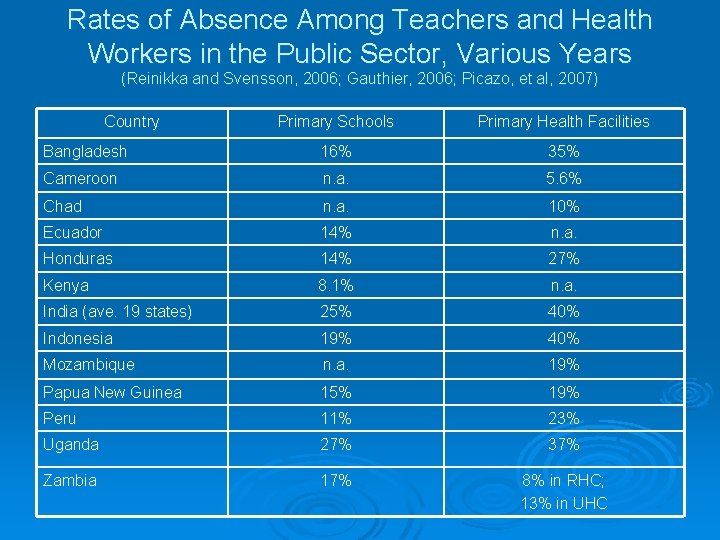

Rates of Absence Among Teachers and Health Workers in the Public Sector, Various Years (Reinikka and Svensson, 2006; Gauthier, 2006; Picazo, et al, 2007) Country Primary Schools Primary Health Facilities Bangladesh 16% 35% Cameroon n. a. 5. 6% Chad n. a. 10% Ecuador 14% n. a. Honduras 14% 27% Kenya 8. 1% n. a. India (ave. 19 states) 25% 40% Indonesia 19% 40% Mozambique n. a. 19% Papua New Guinea 15% 19% Peru 11% 23% Uganda 27% 37% Zambia 17% 8% in RHC; 13% in UHC

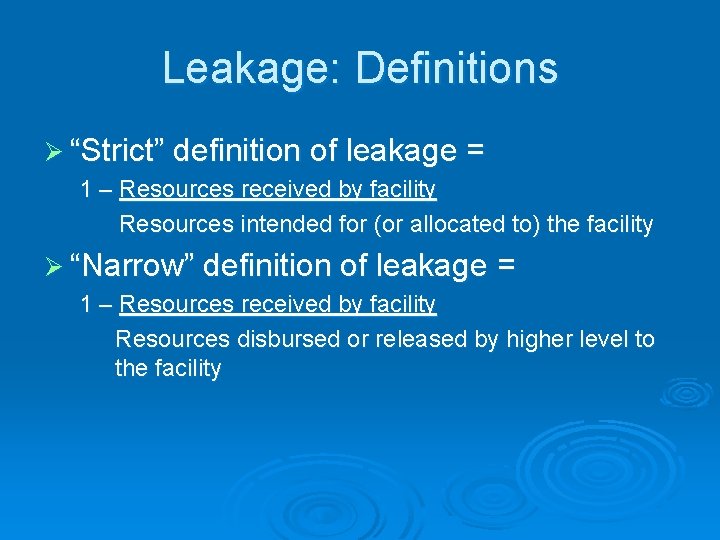

Leakage: Definitions Ø “Strict” definition of leakage = 1 – Resources received by facility Resources intended for (or allocated to) the facility Ø “Narrow” definition of leakage = 1 – Resources received by facility Resources disbursed or released by higher level to the facility

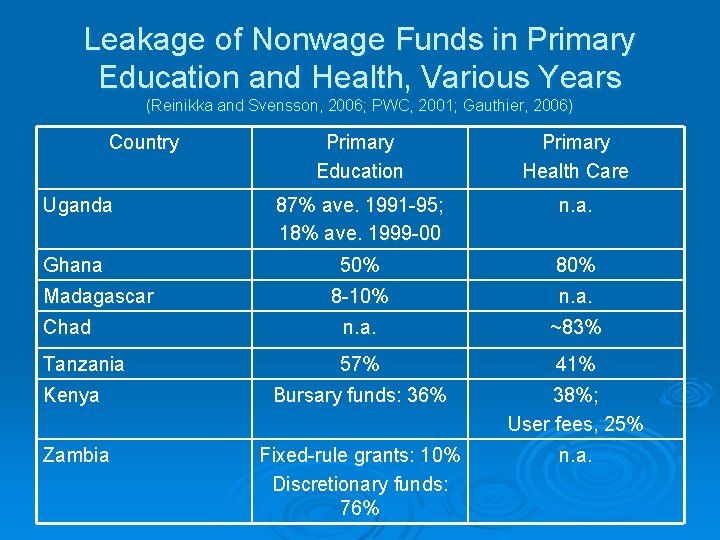

Leakage of Nonwage Funds in Primary Education and Health, Various Years (Reinikka and Svensson, 2006; PWC, 2001; Gauthier, 2006) Country Primary Education Primary Health Care Uganda 87% ave. 1991 -95; 18% ave. 1999 -00 n. a. Ghana 50% 8 -10% n. a. Chad n. a. ~83% Tanzania 57% 41% Kenya Bursary funds: 36% 38%; User fees, 25% Zambia Fixed-rule grants: 10% Discretionary funds: 76% n. a. Madagascar

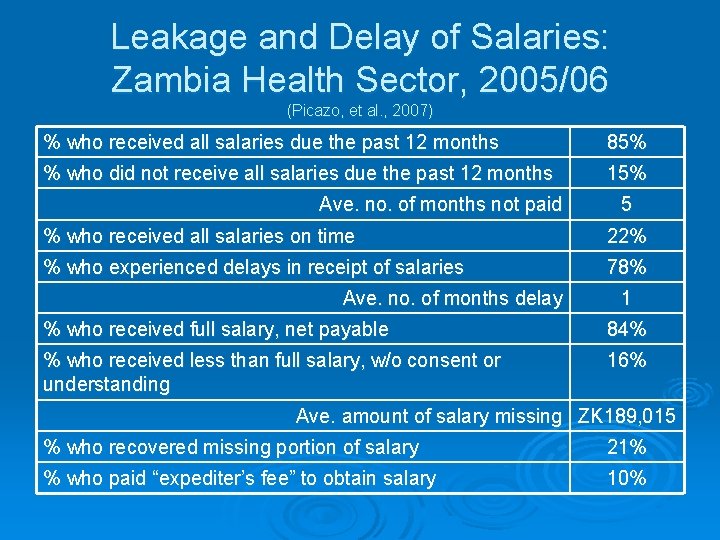

Leakage and Delay of Salaries: Zambia Health Sector, 2005/06 (Picazo, et al. , 2007) % who received all salaries due the past 12 months 85% % who did not receive all salaries due the past 12 months 15% Ave. no. of months not paid 5 % who received all salaries on time 22% % who experienced delays in receipt of salaries 78% Ave. no. of months delay 1 % who received full salary, net payable 84% % who received less than full salary, w/o consent or understanding 16% Ave. amount of salary missing ZK 189, 015 % who recovered missing portion of salary 21% % who paid “expediter’s fee” to obtain salary 10%

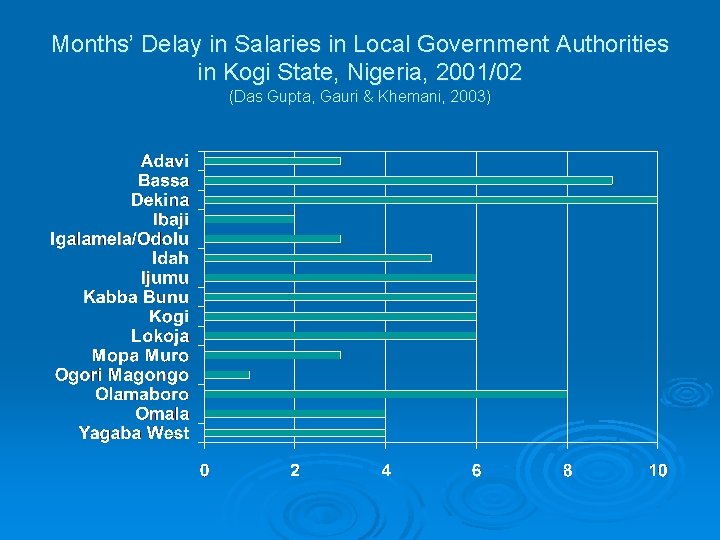

Months’ Delay in Salaries in Local Government Authorities in Kogi State, Nigeria, 2001/02 (Das Gupta, Gauri & Khemani, 2003)

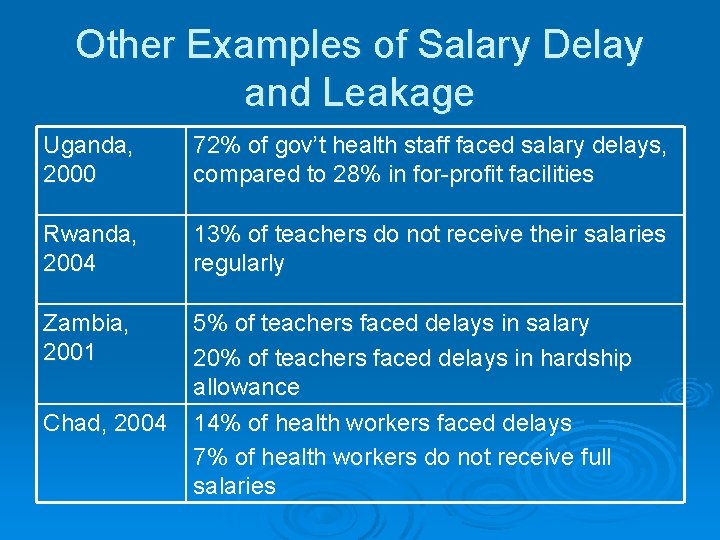

Other Examples of Salary Delay and Leakage Uganda, 2000 72% of gov’t health staff faced salary delays, compared to 28% in for-profit facilities Rwanda, 2004 13% of teachers do not receive their salaries regularly Zambia, 2001 5% of teachers faced delays in salary 20% of teachers faced delays in hardship allowance 14% of health workers faced delays 7% of health workers do not receive full salaries Chad, 2004

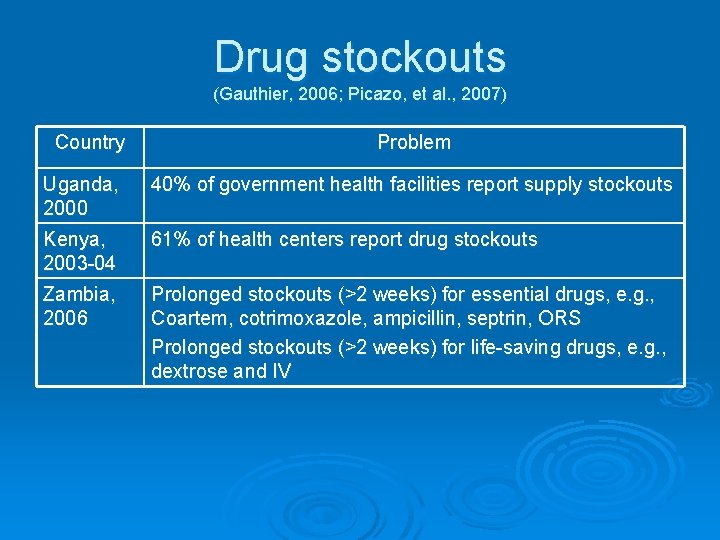

Drug stockouts (Gauthier, 2006; Picazo, et al. , 2007) Country Problem Uganda, 2000 40% of government health facilities report supply stockouts Kenya, 2003 -04 61% of health centers report drug stockouts Zambia, 2006 Prolonged stockouts (>2 weeks) for essential drugs, e. g. , Coartem, cotrimoxazole, ampicillin, septrin, ORS Prolonged stockouts (>2 weeks) for life-saving drugs, e. g. , dextrose and IV

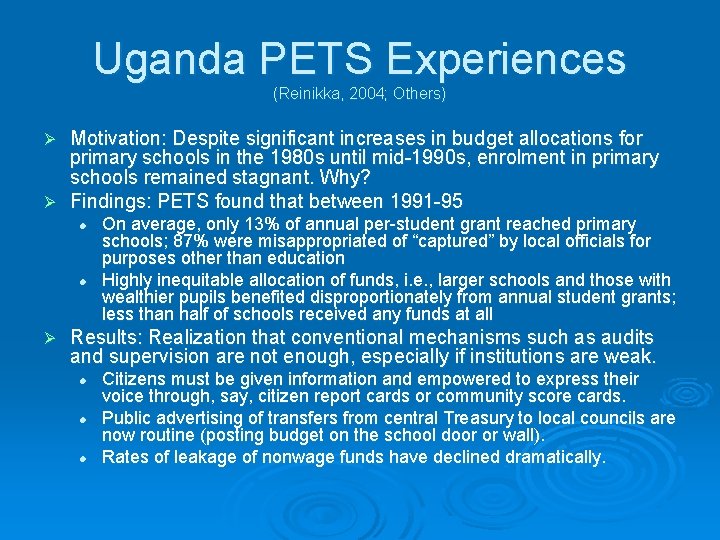

Uganda PETS Experiences (Reinikka, 2004; Others) Motivation: Despite significant increases in budget allocations for primary schools in the 1980 s until mid-1990 s, enrolment in primary schools remained stagnant. Why? Ø Findings: PETS found that between 1991 -95 Ø l l Ø On average, only 13% of annual per-student grant reached primary schools; 87% were misappropriated of “captured” by local officials for purposes other than education Highly inequitable allocation of funds, i. e. , larger schools and those with wealthier pupils benefited disproportionately from annual student grants; less than half of schools received any funds at all Results: Realization that conventional mechanisms such as audits and supervision are not enough, especially if institutions are weak. l l l Citizens must be given information and empowered to express their voice through, say, citizen report cards or community score cards. Public advertising of transfers from central Treasury to local councils are now routine (posting budget on the school door or wall). Rates of leakage of nonwage funds have declined dramatically.

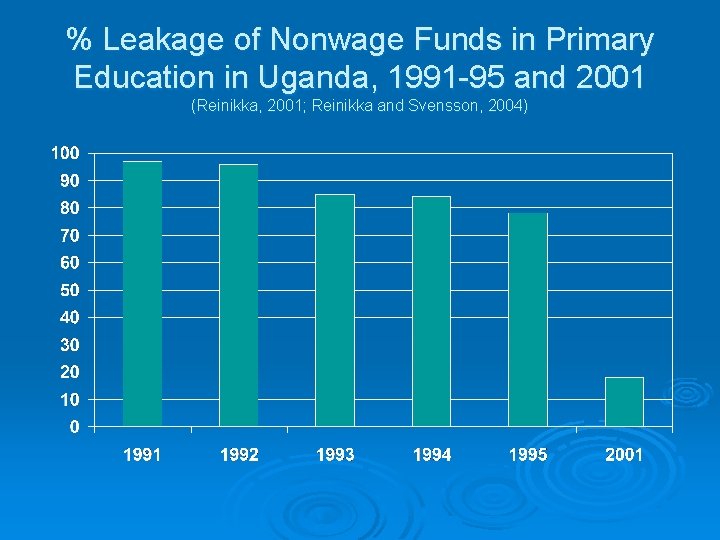

% Leakage of Nonwage Funds in Primary Education in Uganda, 1991 -95 and 2001 (Reinikka, 2001; Reinikka and Svensson, 2004)

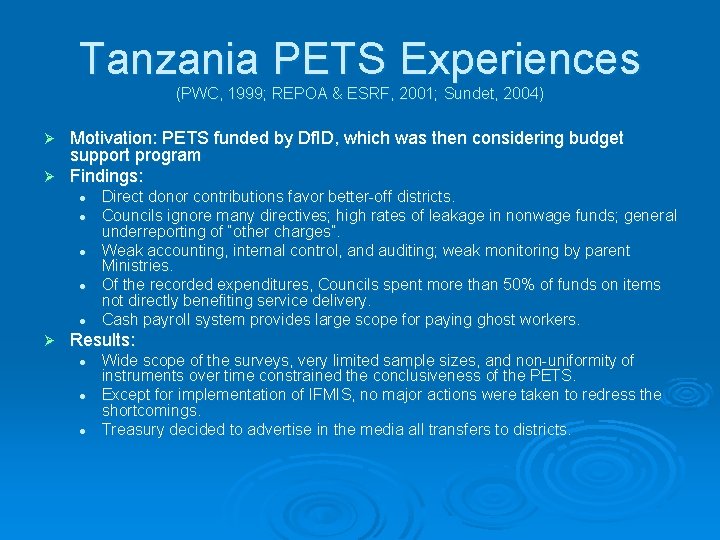

Tanzania PETS Experiences (PWC, 1999; REPOA & ESRF, 2001; Sundet, 2004) Motivation: PETS funded by Df. ID, which was then considering budget support program Ø Findings: Ø l l l Ø Direct donor contributions favor better-off districts. Councils ignore many directives; high rates of leakage in nonwage funds; general underreporting of “other charges”. Weak accounting, internal control, and auditing; weak monitoring by parent Ministries. Of the recorded expenditures, Councils spent more than 50% of funds on items not directly benefiting service delivery. Cash payroll system provides large scope for paying ghost workers. Results: l l l Wide scope of the surveys, very limited sample sizes, and non-uniformity of instruments over time constrained the conclusiveness of the PETS. Except for implementation of IFMIS, no major actions were taken to redress the shortcomings. Treasury decided to advertise in the media all transfers to districts.

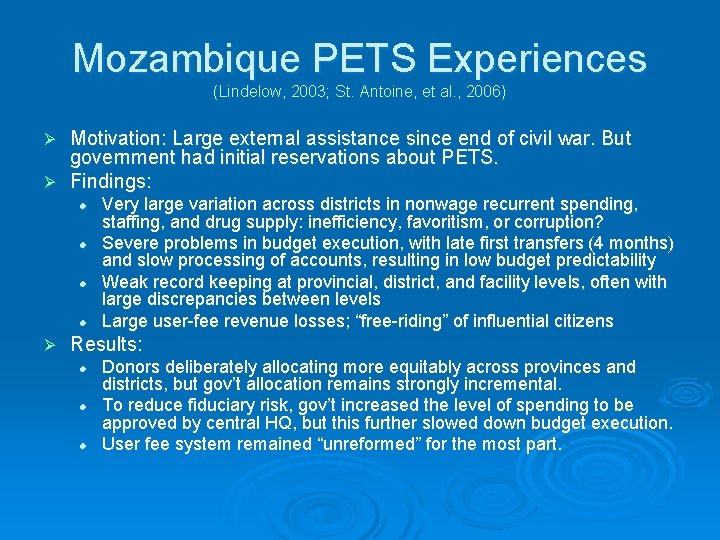

Mozambique PETS Experiences (Lindelow, 2003; St. Antoine, et al. , 2006) Motivation: Large external assistance since end of civil war. But government had initial reservations about PETS. Ø Findings: Ø l l Ø Very large variation across districts in nonwage recurrent spending, staffing, and drug supply: inefficiency, favoritism, or corruption? Severe problems in budget execution, with late first transfers (4 months) and slow processing of accounts, resulting in low budget predictability Weak record keeping at provincial, district, and facility levels, often with large discrepancies between levels Large user-fee revenue losses; “free-riding” of influential citizens Results: l l l Donors deliberately allocating more equitably across provinces and districts, but gov’t allocation remains strongly incremental. To reduce fiduciary risk, gov’t increased the level of spending to be approved by central HQ, but this further slowed down budget execution. User fee system remained “unreformed” for the most part.

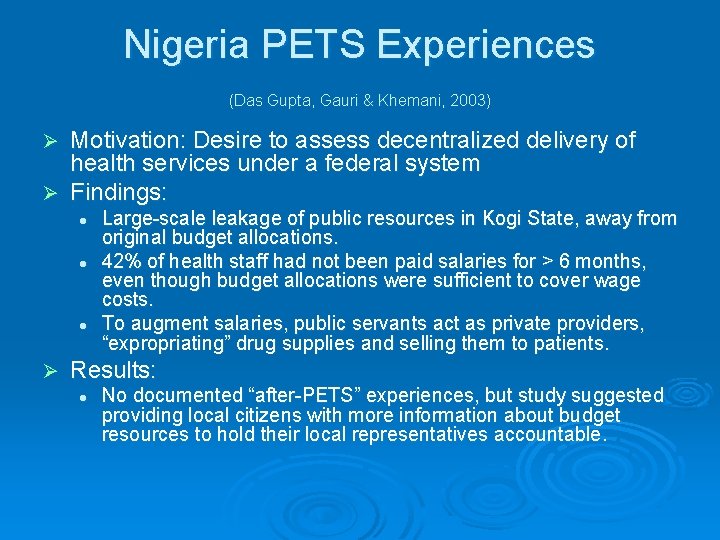

Nigeria PETS Experiences (Das Gupta, Gauri & Khemani, 2003) Motivation: Desire to assess decentralized delivery of health services under a federal system Ø Findings: Ø l l l Ø Large-scale leakage of public resources in Kogi State, away from original budget allocations. 42% of health staff had not been paid salaries for > 6 months, even though budget allocations were sufficient to cover wage costs. To augment salaries, public servants act as private providers, “expropriating” drug supplies and selling them to patients. Results: l No documented “after-PETS” experiences, but study suggested providing local citizens with more information about budget resources to hold their local representatives accountable.

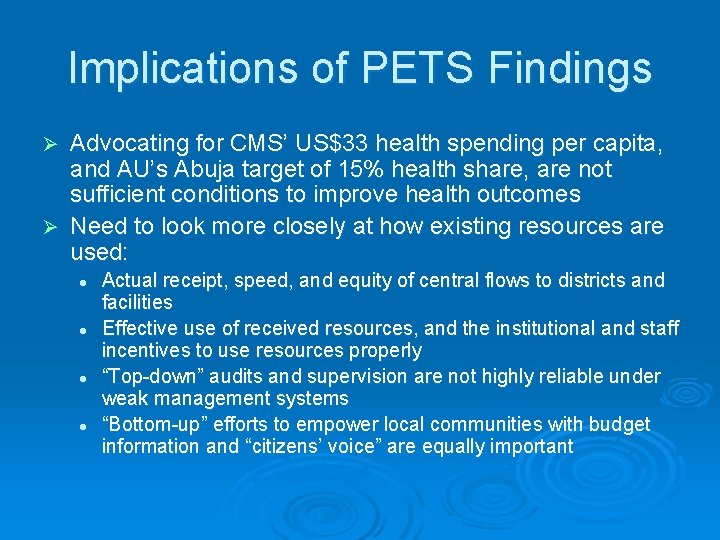

Implications of PETS Findings Advocating for CMS’ US$33 health spending per capita, and AU’s Abuja target of 15% health share, are not sufficient conditions to improve health outcomes Ø Need to look more closely at how existing resources are used: Ø l l Actual receipt, speed, and equity of central flows to districts and facilities Effective use of received resources, and the institutional and staff incentives to use resources properly “Top-down” audits and supervision are not highly reliable under weak management systems “Bottom-up” efforts to empower local communities with budget information and “citizens’ voice” are equally important

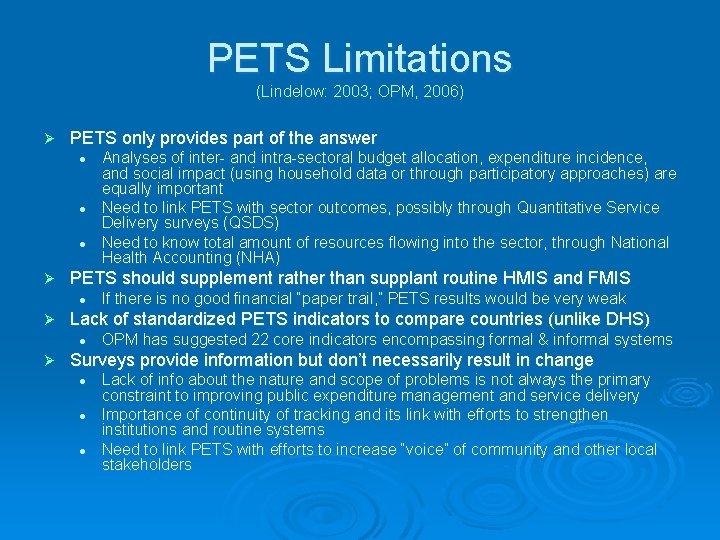

PETS Limitations (Lindelow: 2003; OPM, 2006) Ø PETS only provides part of the answer l l l Ø PETS should supplement rather than supplant routine HMIS and FMIS l Ø If there is no good financial “paper trail, ” PETS results would be very weak Lack of standardized PETS indicators to compare countries (unlike DHS) l Ø Analyses of inter- and intra-sectoral budget allocation, expenditure incidence, and social impact (using household data or through participatory approaches) are equally important Need to link PETS with sector outcomes, possibly through Quantitative Service Delivery surveys (QSDS) Need to know total amount of resources flowing into the sector, through National Health Accounting (NHA) OPM has suggested 22 core indicators encompassing formal & informal systems Surveys provide information but don’t necessarily result in change l l l Lack of info about the nature and scope of problems is not always the primary constraint to improving public expenditure management and service delivery Importance of continuity of tracking and its link with efforts to strengthen institutions and routine systems Need to link PETS with efforts to increase “voice” of community and other local stakeholders

- Slides: 29