Psychological Sciences Preoccupation with the Powerful A Quantitative

- Slides: 1

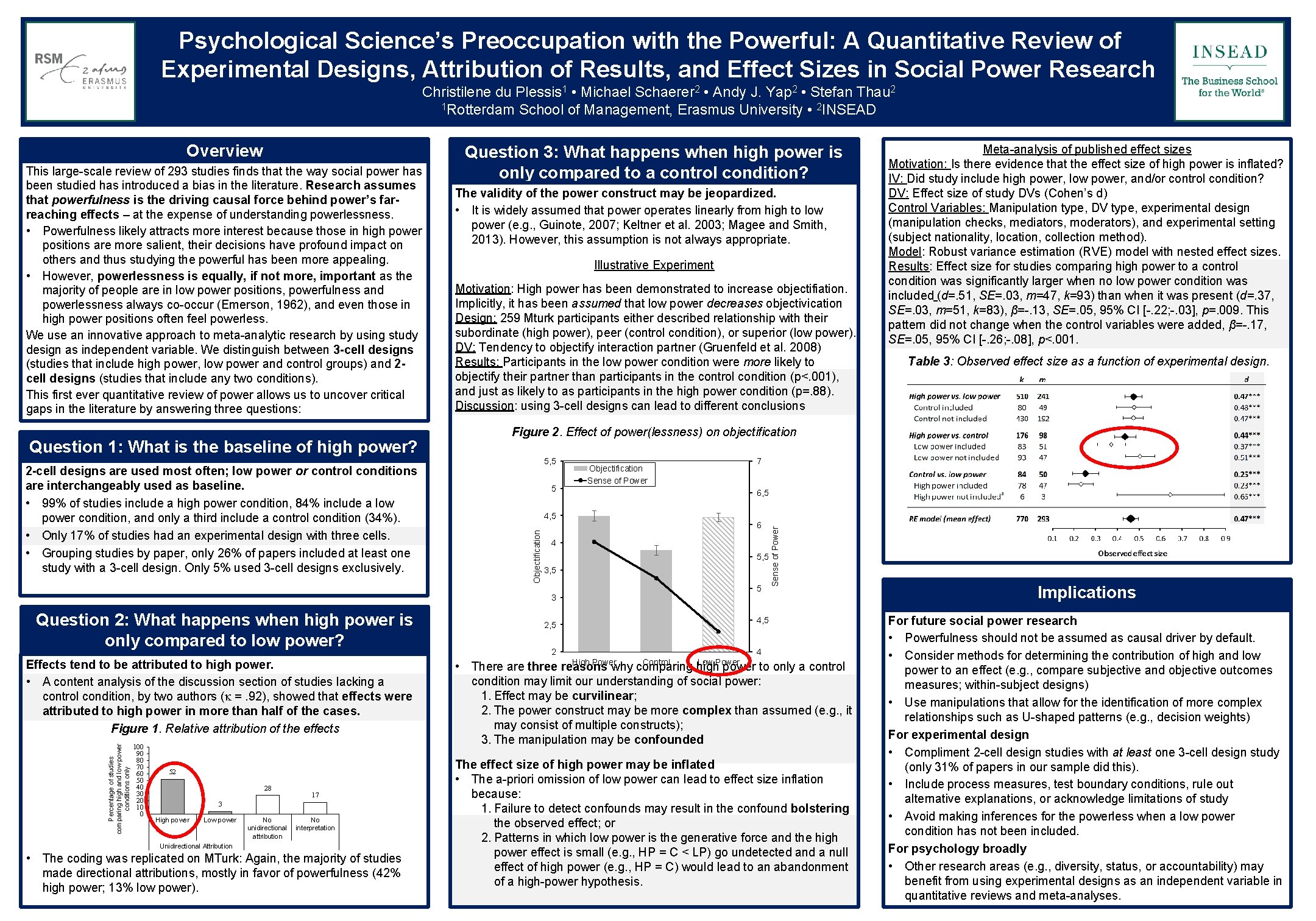

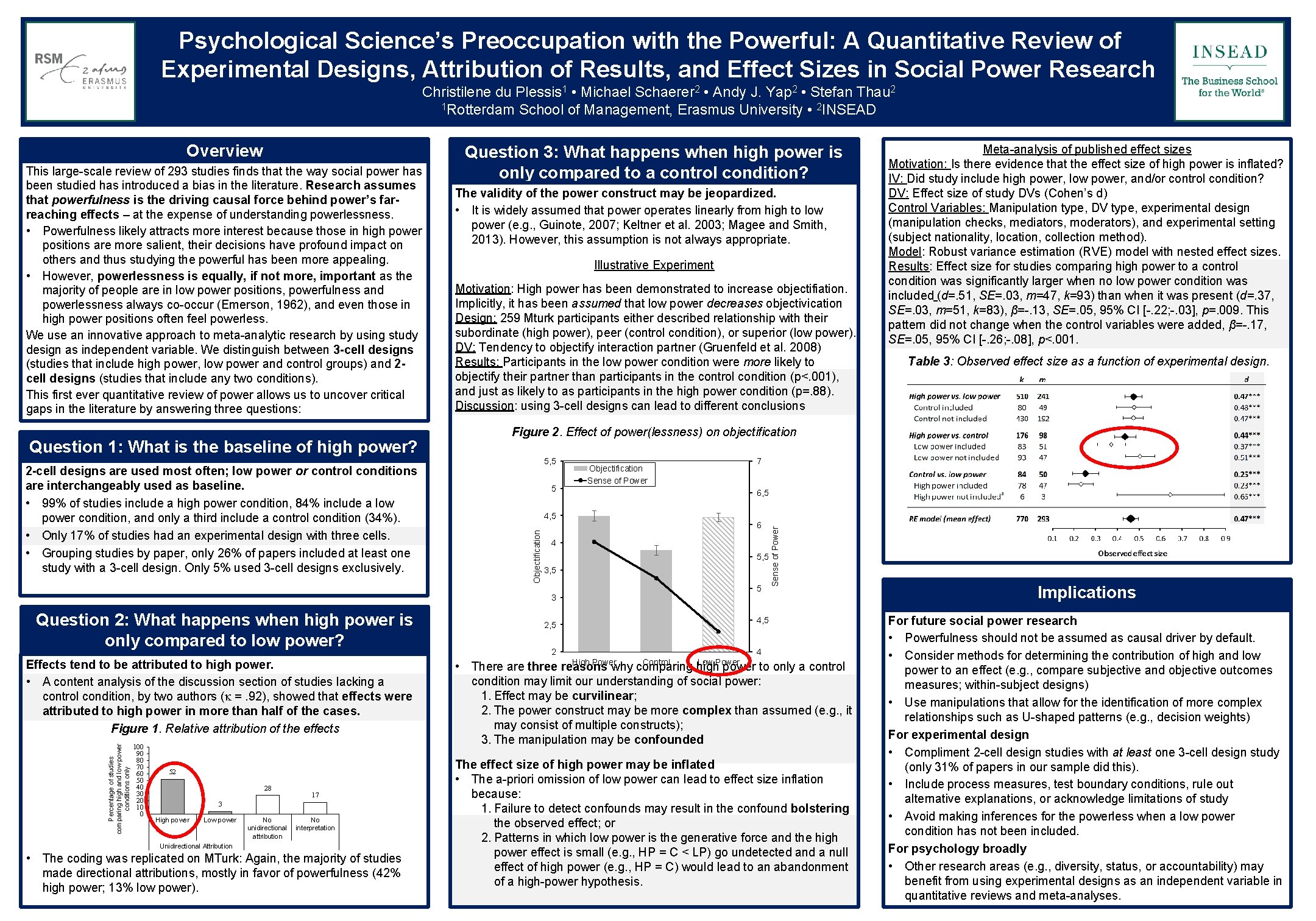

Psychological Science’s Preoccupation with the Powerful: A Quantitative Review of Experimental Designs, Attribution of Results, and Effect Sizes in Social Power Research Christilene du Plessis 1 • Michael Schaerer 2 • Andy J. Yap 2 • Stefan Thau 2 1 Rotterdam School of Management, Erasmus University • 2 INSEAD Question 1: What is the baseline of high power? 2 -cell designs are used most often; low power or control conditions are interchangeably used as baseline. • 99% of studies include a high power condition, 84% include a low power condition, and only a third include a control condition (34%). • Only 17% of studies had an experimental design with three cells. • Grouping studies by paper, only 26% of papers included at least one study with a 3 -cell design. Only 5% used 3 -cell designs exclusively. The validity of the power construct may be jeopardized. • It is widely assumed that power operates linearly from high to low power (e. g. , Guinote, 2007; Keltner et al. 2003; Magee and Smith, 2013). However, this assumption is not always appropriate. Illustrative Experiment Motivation: High power has been demonstrated to increase objectifiation. Implicitly, it has been assumed that low power decreases objectivication Design: 259 Mturk participants either described relationship with their subordinate (high power), peer (control condition), or superior (low power). DV: Tendency to objectify interaction partner (Gruenfeld et al. 2008) Results: Participants in the low power condition were more likely to objectify their partner than participants in the control condition (p<. 001), and just as likely to as participants in the high power condition (p=. 88). Discussion: using 3 -cell designs can lead to different conclusions 5, 5 5 4, 5 Percentage of studies comparing high and low power conditions only Effects tend to be attributed to high power. • A content analysis of the discussion section of studies lacking a control condition, by two authors ( =. 92), showed that effects were attributed to high power in more than half of the cases. Figure 1. Relative attribution of the effects 100 90 80 70 60 50 40 30 20 10 0 52 28 17 3 High power Low power No unidirectional attribution No interpretation Unidirectional Attribution • The coding was replicated on MTurk: Again, the majority of studies made directional attributions, mostly in favor of powerfulness (42% high power; 13% low power). Objectification Sense of Power Table 3: Observed effect size as a function of experimental design. 7 6, 5 6 4 5, 5 3 Question 2: What happens when high power is only compared to low power? Meta-analysis of published effect sizes Motivation: Is there evidence that the effect size of high power is inflated? IV: Did study include high power, low power, and/or control condition? DV: Effect size of study DVs (Cohen’s d) Control Variables: Manipulation type, DV type, experimental design (manipulation checks, mediators, moderators), and experimental setting (subject nationality, location, collection method). Model: Robust variance estimation (RVE) model with nested effect sizes. Results: Effect size for studies comparing high power to a control condition was significantly larger when no low power condition was included (d=. 51, SE=. 03, m=47, k=93) than when it was present (d=. 37, SE=. 03, m=51, k=83), β=-. 13, SE=. 05, 95% CI [-. 22; -. 03], p=. 009. This pattern did not change when the control variables were added, β=-. 17, SE=. 05, 95% CI [-. 26; -. 08], p<. 001. Figure 2. Effect of power(lessness) on objectification 2, 5 2 5 Sense of Power This large-scale review of 293 studies finds that the way social power has been studied has introduced a bias in the literature. Research assumes that powerfulness is the driving causal force behind power’s farreaching effects – at the expense of understanding powerlessness. • Powerfulness likely attracts more interest because those in high power positions are more salient, their decisions have profound impact on others and thus studying the powerful has been more appealing. • However, powerlessness is equally, if not more, important as the majority of people are in low power positions, powerfulness and powerlessness always co-occur (Emerson, 1962), and even those in high power positions often feel powerless. We use an innovative approach to meta-analytic research by using study design as independent variable. We distinguish between 3 -cell designs (studies that include high power, low power and control groups) and 2 cell designs (studies that include any two conditions). This first ever quantitative review of power allows us to uncover critical gaps in the literature by answering three questions: Question 3: What happens when high power is only compared to a control condition? Objectification Overview 4, 5 4 High Power Control Low Power • There are three reasons why comparing high power to only a control condition may limit our understanding of social power: 1. Effect may be curvilinear; 2. The power construct may be more complex than assumed (e. g. , it may consist of multiple constructs); 3. The manipulation may be confounded The effect size of high power may be inflated • The a-priori omission of low power can lead to effect size inflation because: 1. Failure to detect confounds may result in the confound bolstering the observed effect; or 2. Patterns in which low power is the generative force and the high power effect is small (e. g. , HP = C < LP) go undetected and a null effect of high power (e. g. , HP = C) would lead to an abandonment of a high-power hypothesis. Implications For future social power research • Powerfulness should not be assumed as causal driver by default. • Consider methods for determining the contribution of high and low power to an effect (e. g. , compare subjective and objective outcomes measures; within-subject designs) • Use manipulations that allow for the identification of more complex relationships such as U-shaped patterns (e. g. , decision weights) For experimental design • Compliment 2 -cell design studies with at least one 3 -cell design study (only 31% of papers in our sample did this). • Include process measures, test boundary conditions, rule out alternative explanations, or acknowledge limitations of study • Avoid making inferences for the powerless when a low power condition has not been included. For psychology broadly • Other research areas (e. g. , diversity, status, or accountability) may benefit from using experimental designs as an independent variable in quantitative reviews and meta-analyses.