PSY 4603 Research Methods The Research Variables How

PSY 4603 Research Methods The Research Variables & How to Control Them

– An experimental research hypothesis is an assertion that systematic variation of (1) an independent variable produces lawful changes in (2) a dependent variable. – A critical characteristic of a sound research is that (3) the extraneous variables are controlled (or addressed in some manner).

• Independent Variables – Stimulus Variables • In research, the independent variable is a stimulus, where the word "stimulus" broadly refers to any aspect of the environment (physical, social, and so on) that excites the receptors. • When we use the term "stimulus, " though, we actually mean a certain stimulus class. – Organismic Variables • The possible relationships between organismic variables and behavior are studied using the method of systematic observation (or quasi-experiments) rather than experimentation. • An organismic variable is any relatively stable physical characteristic of an organism such as gender, eye color, height, weight, and body build, as well as such characteristics as intelligence, educational level, neuroticism, and prejudice.

• Dependent Variables – Response Measures • Since in psychology we’re interested in some aspect of human or animal behavior, and since the components of behavior are responses, our dependent variables are typically (but not always) response measures. • "Response measures" is also an extremely broad class that includes such diverse phenomena as – number of drops of saliva a person secretes when tasting cheesecakes, – number of errors an employee makes on a task, – time it takes a person to solve a problem, amplitude of electromyograms (electrical signals given off by muscles when they contract), – number of words spoken in a given period of time, – accuracy of throwing a baseball, and – judgments of people about certain traits.

• Accuracy. One way to measure response accuracy would bewith a metrical system, such as when we fire a rifle at a target. • Latency. This is the time that it takes from the onset of a stimulus to the start of a response, as in reaction-time studies. • Duration (Speed). This is a measure of how long it takes to complete a response, once it has started. – To emphasize the distinction between latency and duration measures: latency is the time between the onset of the stimulus and the onset of the response, and speed or duration is the time between the onset and termination of the response, important differences indeed. • Frequency and Rate. Frequency is the number of times a response occurs, as in how many responses an organism makes before extinction of a behavior. • Additional Response Measures. Other examples are level of ability that a person can manifest (e. g. , how many problems of increasing difficulty one solves with an unlimited amount of time) or the intensity of a response (e. g. , the amplitude of the galvanic skin response in an emotional situation).

• The first requirement for a dependent variable - it must be valid. – By validity we mean that the data reported are actual measures of the dependent variable as it is operationally defined; that is, the question of validity is whether the operationally defined dependent variable truly measures that which is specified in the consequent condition of the hypothesis • Reliability of Dependent Variables – The second requirement is that a dependent variable should be reliable. – One meaning of reliability is the degree to which participants receive the same scores when repeated measurements of them are taken. – A one-way affair: If there are statistically reliable differences among groups, the dependent variable is probably reliable; if there are no significant differences, then no conclusion about its reliability is possible (at least on this information only).

– If replications of the experiment yield consistent results repeatedly, certainly the dependent variable is reliable. – Fundamental definitions are general in two senses: They are universally accepted, and they encompass a variety of specific concepts. » A fundamental definition of anxiety would encompass several specific definitions, with each specific definition weighted according to how much of the fundamental definition it accounts for. For instance, each definition of anxiety may be an indicator of a generalized, fundamental concept: fundamental concept of anxiety = f(anxiety 1, anxiety 2, . . . , anxiety. N)

• General Types of Empirical Relationships – There are two principal classes of empirical laws involving independent variables: (1) stimulus-response relationships which result from the use of the experimental method and (2) organismic-response laws which are derived from the use of the method of systematic observation (quasi-experimental & correlational approaches). – Stimulus-Response Laws • This type of law states that a certain response class is a function of a certain stimulus class and may be symbolized as R =f(S). • To establish an S-R law, a given stimulus is systematically varied as the independent variable to determine whether a given response (the dependent variable) also changes in a lawful manner. – Organismic-Behavioral Laws • This type of relationship asserts that a response class is a function of a class of organismic variables, which is symbolized R = f(O). • Research seeking to establish this kind of law aims to determine whether certain characteristics of an organism are associated with certain types of responses.

• The Nature of Experimental Control – An Example. . . – A sophisticated, but still ancient, investigation did include a control condition: "Athenaeus, in his Feasting Philosophers (Deiphosophistae, III, 84 -85), describes how it was discovered that citron was an antidote for poison. It seems that a magistrate in Egypt had sentenced a group of convicted criminals to be executed by exposing them to poisonous snakes in theater. It was reported back to him that, though the sentence had been duly carried out and all the criminals were bitten, none of them had died. The magistrate at once commenced an inquiry. He learned that when the criminals were being conducted into theater, a market woman out of pity had given them some citron to eat. The next day, on the hypothesis that it was the citron that had saved them, the magistrate had the group divided into pairs and ordered citron fed to one of a pair but not to the other. When the two were exposed to the snakes a second time, the one that had eaten the citron suffered no harm, the other died instantly. The experiment was repeated many times and in this way (says Anthenaeus) the efficacy Of Citron as an antidote for poison was firmly established" (Jones, 1964, p. 419).

– Two Kinds of Control of the Independent Variable • There are two ways in which an investigator may exercise control of the independent variable: (1) purposive variation (manipulation) of the variable, and (2) selection of the desired values of the variable from a number of values that already exist. • When purposive manipulation is used, an experiment is being conducted, but selection is used in the method of systematic observation. – If you are interested in whether the intensity of office lighting affects the rate of processing, you might vary intensity in two ways - high and low. » Since the stimulus is a light, such values as 2 and 20 candlepower might be chosen. » You would, then, at random: (1) assign the sample of participants to two groups, and (2) randomly determine which group would receive the low-intensity stimulus, which one the high. – In this case you are purposely varying (manipulating & controlling) the independent variable (this is an experiment). » The decision as to what values of the independent variable to study and, more important, which group receives which value is entirely up to you. » Perhaps equally important, you also "create" the values of the independent variable.

• To illustrate control of the independent variable by selection of values as they already exist (the method of systematic observation), consider the effect of intelligence on problemsolving. – Assume that the researcher is not interested in studying the effects of minor differences of intelligence but wants to study widely differing values of this variable, such as an average IQ of 135, a second of 100, and a third of 65. – Up to this point the procedures for the two types of control of the independent variables are the same; the investigator determines what values of the variables are to be studied. – However, in this case, the investigator must find certain groups that have the desired values of intelligence. » The IQs of the people tested determined who would be the participants. » The researcher has not, as in the experimental example, determined which participants would receive which value of the independent variable. – In selection it is thus the other way around: the value of the independent variable determines which participants will be used.

• Techniques of Extraneous Variable Control – The following common techniques illustrate major principles that can be applied to a wide variety of specific control problems. • Elimination. The most desirable way to control extraneous variables is simply to eliminate them from the research situation. – For example, some laboratories are sound deadened and opaque to eliminate extraneous noises and lights. Other extraneous variables that one would have a hard time eliminating are gender, age, and intelligence.

• Constancy of Conditions. Extraneous variables that cannot be eliminated might be held constant throughout the experiment. – The same value of such a variable is thus present for all participants. » Perhaps the time of day is an important variable in that people perform better on the dependent variable in the morning than in the afternoon. – One of the standard applications of the technique of holding conditions constant is to conduct experimental sessions in the same room. » Thus, whatever might be the influence of the particular characteristics of the room (gaiety, odors, color of the walls and furniture, location), it would be the same for all participants. » In like manner, to hold various organismic variables constant (educational level, sex, age), we would select participants with the characteristics that we want. – The technique of constancy of conditions dictates that all participants use the same carousel projector, Power. Point presentation, recording apparatus, or other equipment.

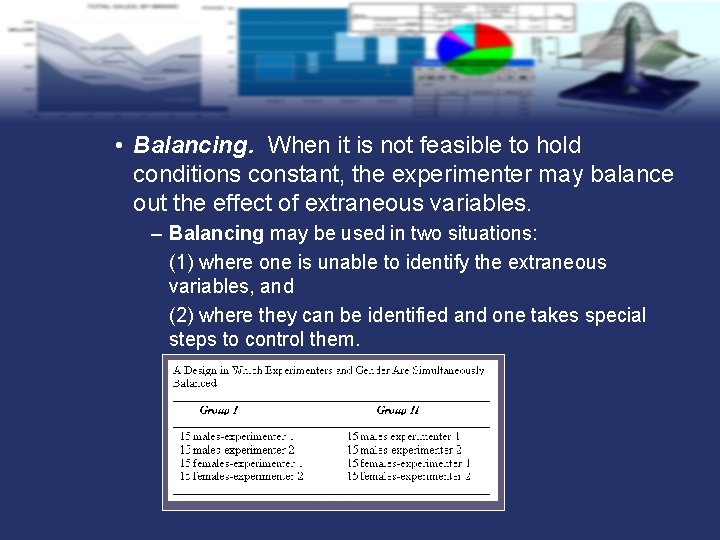

• Balancing. When it is not feasible to hold conditions constant, the experimenter may balance out the effect of extraneous variables. – Balancing may be used in two situations: (1) where one is unable to identify the extraneous variables, and (2) where they can be identified and one takes special steps to control them.

• Counterbalancing. In some experiments each participant serves under two or more different experimental conditions; for example, to determine whether a stop sign should be painted red or yellow, we might measure reaction times to them. – The general principle of counterbalancing is that: (1) in repeated treatment experiments, each condition (e. g. , color of sign) must be presented to each participant an equal number of times, and each condition must occur an equal number of times at each practice session. (2) Furthermore, each condition must precede and follow all other conditions an equal number of times.

– The Problem of Differential Transfer » Differential transfer means that the transfer from condition 1 (when it occurs first) to condition 2 is different from the transfer from condition 2 (when it occurs first) to condition 1. » In general, differential transfer reduces the recorded difference between two conditions, but it may also exaggerate the difference.

• Randomization is a procedure that assures that each member of a population or universe has an equal probability of being selected. – Randomization is used as a control technique because the experimenter takes certain steps to equalize effects of extraneous variables on the different groups. – Randomization has two general applications: (1) where it is known that certain extraneous variables operate in the experimental situation, but it is not feasible to apply one of the preceding techniques of control, and (2) where we assume that some extraneous variables will operate, but cannot specify them and therefore cannot apply the other techniques.

• Researcher Bias • Confounding Examples

- Slides: 19