PSIR 206 Political History of Europe II Slides

- Slides: 44

PSIR 206 Political History of Europe II Slides 7 1

J. ROBERT WEGS & ROBERT LADRECH CHAPTER 11: Eastern Europe and the Soviet Union to the 1970 s and Beyond: Decline Fall and Transition (pp. 233 -251) 2

& The Fall of Communism in Eastern Europe 3

� The Gorbachev «Phenomenon» as Wegs & Ladrech call it, naturally had a massive impact on other Eastern European regimes. � It must be emphasized, that the fundamental objective of Gorbachev’s reforms was not to end the Soviet Union’s socialist system, but, (by making it more efficient and effective), to save it! Nor was his ultimate objective to end the role of the Soviet Union as a world power. � Nevertheless, his efforts led to instability (as all major efforts to introduce change run the risk of doing), and more rapidly heightened the underlying tensions and spurred domestic opposition and nationalism in all non-Russian territories. 4

� While the so-called «Brezhnev Doctrine» had cracked down on the independence of communist regimes in eastern Europe, Gorbachev, partly perhaps due to the constraints under which he operated, followed a much less heavy-handed policy. In Eastern Europe too he also encouraged and supported reformists, though his preocuppation was with the USSR. When in late 1989 eastern European societies lined-up to overthrow their socialist regimes and leave the Warsaw Pact, Soviet foreign ministry spokesman Gennady Gerasimov humourously summarized the new Soviet doctrine in reference to the famous song by Frank Sinatra «my way» , each would choose its own fate and the USSR would not intervene Gorbachev had decided. * * It is of course questionable whether at this late stage (Fall 1989) Gorbachev could have 5 halted the tide of open & growing public opposition that eastern European regimes faced.

� Few predicted such a rapid collapse of communist regimes in Eastern Europe, even though it was clear to some by 1988 that change was in the air. Developments in the USSR under Gorbachev had spurred civil unrest and opposition in Eastern Europe. Further, developments in one Eastern European state had consequences for others ( «knock-on-effect» ), & the adoption of the «Sinatra Doctrine» made them all the more feasible. It could, from a more ideological perspective, be argued too that these regimes were doomed to fail. � Yet, while all of the above may be highlighted as causes of the end of communism in Eastern Europe, the dynamics of the collapse for each regime can only be fully comprehended with reference to domestic developments too. As such, developments in Poland, the first to fall, deserve some special recognition. 6

7

�A propensity for protest at working conditions & standards of living followed by compromise was noted during the Polish October of 1956. Many workers demands of the time were met, they were apologized to & the more popular Gomulka kept in power, albeit with the understanding that Poland remain essentailly loyal to socialist ideals and to the leadership of the USSR. � During the Brezhnev era Gomulka appeared to be becomming more conservative, freedoms of intellectuals & Church officials were restricted. Coupled with his deteriorated health, rising discontent following the violent suppression of workers’ strikes in 1970 led to his replacement by the younger more dynamic Edward Gierek. 8

� Initially Gierek managed to keep the population satisfied through the supply of more plentiful consumer goods made possible through Soviet subsidies (especially for energy) & western loans. By the mid-1970’s, however, reduced subsidies & loans forced him to hike the prices of basic necessities, leading to new strikes again crushed by force. � Public opposition to Gierek’s government grew with the selection of a Polish Cardinal to become the new Roman Catholic Pope in 1978. Pope John Paul II visited Poland the following year to be followed by massive adoring crowds. For a still highly religious society he became a figurehead & symbol of opposition, contrasting with that of the unpopular Communist regime. 9

� A new wave of strikes and protest occurred when Gierek’s attempted to increase the price of meat in 1980, leading to his replacement by Stanislaw Kania. The most significant of these strikes occurred at the Gdansk shipyard where a new trade union federation named «Soldiarity» ( «Solidarnosc» in Polish) was established. � The weakness of the ecnomoy and fear that widespread strikes woul both fuel futher public discontent and make it impossible to meet debt repayments pressured the authorities to compromise with Solidarity and its leader Lech Walesa. Several concessions were made, including the government for the first time recognizing the legality of a non-communist trade union and allowing the broadcast of Catholic services on radio. � Solidarity soon became much more than just a trade union, as discontented persons of different persuasions gathered under its leadership. By 1981 close to 10 million persons became official members and many others sympathized. 10

� As Solidarity gained in strength, the strength and legitimacy of the Communist Party diminished. Talk of Soviet intervention was met by moderation by Walesa, who temporarily stopped demonstrations demanding change; � However, when in Dec 1981 Solidarity demanded free and competitive elections, the Polish General, Wojciech Jaruzelski, who had become Communist Party leader the previous month, now declared martial law. With the support of Moscow, (but not direct intervention), Polish troops took over control and a military dictatorship was established. 11

� Though persecuted for several years, Solidarity survived underground (ie. İllegally) & remained popular, but, unable to resolve even economic difficulties the Communist Party never regained its legitimacy. With Gorbachev’s radical position in the USSR now apparent, Jaruzelski began official «Round Table» negotiations with Walesa in Feb 1989. � The «Round Table» talks resulted in a compromise whereby many, though not most seats in parliament would be contested freely in elections in June 1989, (the rest reserved for Communist Party approved candidates). It was also agreed that fully competitive elections would be held thereafter and a president elected by popular vote. The elections were a virtually complete victory for Solidarity which soon after led the formation of a new coalition government (including communists) was formed. The elections and their aftermath basically marked the end of the Communist regime in Poland. 12

13

� The fate of Hungary in 1956 had appeared much more dramatic than that of Poland where a military crackdown was avoided. Unlike Gomulka, Party General Secretary Janos Kadar had not had the benefit of public support, having been implicated in the Soviet-led crackdown. � Nevertheless, Kadar did become increasingly popular, as liberalizing measures were gradually introduced & standards of living improved. Reforms increasingly distancing the state from orthodox Marxist positions, led to the application of the term «Goulash Communism» for Hungary, referencing the famous Hungarian dish that is a mixture of a wide range of ingredients. 14

� Together with the introduction of greater freedom of speech & travel, & a tougher stance on corruption & privilege within the party, Kadar is best know for having introduced in 1968 the New Economic Mechnaism (NEM). It was in some ways a forerunner of reforms that Gorbachev was later to introduce in the USSR. � The NEM decentralized economic decision making; required economic enterprises to seek profits in order to stay afloat; allow for greater trade with the West (& thereby forced competition upon domestic producers); allowed the market to determine prices on certain services & products &; allowed both self-management of collective farms and the freedom of presents to control produce they gained from small private plots. � Improved economic conditions meant that public contentment soon appeared to be higher in Hungary than in any other E European country. 15

� Kadar grew old & ill, beginning to lose popularity when difficulties were faced in meeting continually rising expectations (especially when orders from the West were reduced during the widespread recession of the early 1980’s). Younger reformers pushed for more radical change including greater political reform which they argued would also contribute to greater freedom in economic decision-making & boost the economy. Gorbachev’s arrival soon provided them with the backing they needed to take control. 16

� In May 1988 Kadar (who died a year later) was pushed into retirement, admitting shortly before his death regret for some responsibility in the death of his onetime colleague Imre Nagy. Reformists now were in the majority. By October 1989 they had revised the constitution to eliminate the one-party rule of the communist party & began preparations for multi-party elections. � Held at the end of March, beginning of April 1990 both hard-line and reformed communists gained only a small proportion of the vote (4% & 9%) while the umbrella opposition party known as the Hungarian Democratic Forum (HDF) gained 43% & the liberal Alliance of Free Democrats (AFD) gained 24%. The HDF now formed the first wholly non-communist government & proceeded to fully liberalize the economy basically along the lines of the capitalist system. 17

18

� In the earlier post-War years one of the biggest difficulties faced by E Germany had been its loss of population, particularly of the younger & more skilled. Over 3 million had left for the West by the 1960’s (close to 20% of the overall population) many via west Berlin. The death of many young men during the War (at an age when they were most productive) and the eparations and the removal of much of its industrial capacity to the Soviet Union made matters worse. � By the beginning of the 1960’s, however things had stablized, (with emmigration virtually stopped, especially following the construction of the Berlin Wall in 1961). 19

� Under the leadership of Walter Ulbricht, the E German economy began to be seen as the most efficient in the East. In 1963 Ulbricht had introduced a reform programme known as the New Economic System for Planning and Management (NES) which brought decentralization to economic decision-making & had positive economic results. � Nevertheless, these results were not sufficiently positive when compared with those of Western Germany. Further, as far as contact with the West and political freedoms were concerned, East Germany (where numerous Soviet forces remained stationed following the war) was one of the least «liberal» . � Ulbricht’s strict rejection of contact with the west led during the early days of the period of Detente to the USSR putting pressure on the E Germany party for his replacement by Erich Honecker who was more of a pragmatist. Honecker essentially, though, continued along much the same path as before, albeit emphasizing consumer goods and athletic prowess a bit more. Dissent, however, was strictly rejected & adherence to the Communist Party, loyalty to the USSR paramount. 20

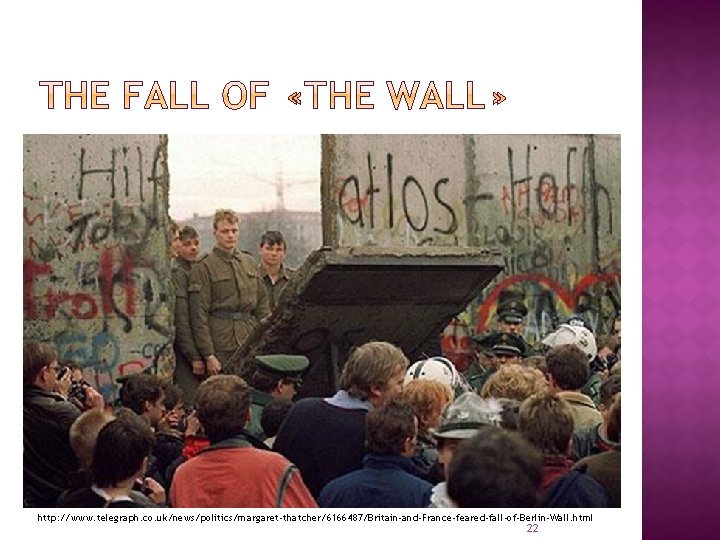

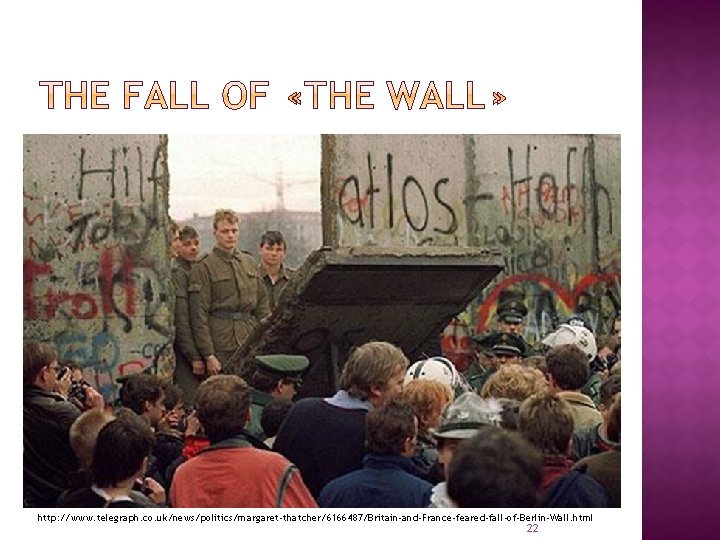

� With Gorbachev’s reforms challenging the political orthodoxy of Honecker’s regime & its legitimacy, and with news of developments in other Eatsren European states spreading, pressures began to mount. During May 1989 there appears to have been a big protest vote against the regime in local elections that Honnecker tried to cover-up, but this just increased tensions further with hundreds of thousands trying to leave the country via Hungary, which in its new more liberla form was prepared to act as a point of transit, and with which there were virtually no travel restrictions for E Germans. � Gorbachev, who was not happy with Honecker’s hardline politics, gave him the message that the Soviet Union would not intervene to end any popular protest, and interestingly this private message was leaked (actually encouraging people to protest). 21

http: //www. telegraph. co. uk/news/politics/margaret-thatcher/6166487/Britain-and-France-feared-fall-of-Berlin-Wall. html 22

� For a few days Honecker had tried to use police force to crush the protests, but, probably realizing the futility in the face of growing numbers, he finally resigned on 18 Oct. A temporary replacement Communist government then opened-up travel to W Germany on 9 th Nov, but couldn’t stop the outward flow & Germans who gathered at the wall began to symbollically chip it down & the rising public demands for unification with W Germany. � Even the change of the Communist Party name (to become «Party of Democratic Socialism» ) and inclusion of opposition representatives in the government could not restore order & stop demands that they go. Ultimately they too resigned, new elections dominated by branches of parties organized in West Germany were held in March 1990 and on 3 Oct 1990 West & East Germany were officially reunited. 23

� As noted, Gorbachev had made it clear that he wasn’t going to use Soviet military might to halt protests in E Germany. The East Germans were generally clamouring for union & W German Chancellor Helmut Kohl was doing all in his power (including reassuring the USSR) to allow it to proceed. Interestingly, however, recently revealed British government records show that in private at least (despite their more official statements) , the British & French leaders (PM Margaret Thatcher & Pres. François Mitterand) were not at all enthusiastic & would have preferred this reunification to be blocked. Thatcher even said as much to Gorbachev in a private meeting in Moscow! � See http: //www. telegraph. co. uk/news/politics/margaretthatcher/6166487/Britain-and-France-feared-fall-of-Berlin -Wall. html 24

25

The Prague Spring is commemorated as perhaps the most symbolic moment of opposition to the Cold War Soviet domination of E Europe. Compared to most other parts of E Europe, Czechoslovakia had been relatively industrialized before WWII & had maintained a liberal democratic political system until the Nazi takeover (itself made easier by the appeasment policies of France & Britain). Following the War Czechs & Slovaks had welcomed the liberating Red Army of the USSR, but most had not expected that they would within a few years come under the domination of a communist regime under Moscow’s thumb. � Antonin Novotnyn had followed largely orthododox communist policies & maintained loyalty to the Soviet model & leadership. Aware of growing opposition to his leadership, he convinced Brezhnev to come to Prague & make known to leading communists his support for Novotny. However, when Brezhnev saw how strong the opposition was he actually supported a change of leadership. � 26

� � The starting point of the «Prague Spring» can be identified as the comming to power of the reformist Alexander Dubcek as First Secretary (leader) of the Czechoslovak Communist Party in Jan 1968 though it reached its heights during the Spring months later that year, ending with Soviet-led invasion in Aug 1968. Dubcek argued for «socialism with a human face» & amongst democratizing reforms he introduced were those supporting freedom of expresion for the media and public, acceptance of non-communist organization, freedom of travel, and the granting of greater autonomy to the Slovaks(who constituted about 1/3 of the population, largely in the east) through the establishment of a federation. Likewsie the economy was also to become more decentralized, but it was the shift to democracy that he saw as vital even in this area, stating, "We shall have to remove everything that strangles artistic and scientific creativeness. " 27

� As hard-liners resisted introduction of the changes supported by Dubcek, protests in his support & demanding even more radical reforms grew on the streets. Particularly influential were the efforts of certain prominent writers from the Union of Czechoslovak Writers including Milan Kundera & Vaclav Havel. � While Dubcek took care to emphasize that changes would be adopted under the leadership of the Communist Party he pushed forward with reforms virtually eliminating censorship, referring to Czechoslovakia’s democratic history & calling for more friendly relations with the West. Writers & the media generally became openly critical of the regime & relations with Moscow, touching upon previously taboo topics. 28

� Initially shown some support among Warsaw Pact states by Janos Kadar, Brezhnev & those in the USSR became increasingly concerned that Dubcek was going too far & threatening the very existence of the regime & the solidarity of the Pact within the Cold War framework. They tried to negotiate with Dubcek to limit reforms, but feeling they were failing to restrain him, they led an invasion of Czechoslovakia (together with forces from Hungary, Poland, E Germany & Bulgaria – notably excluding Albania & Romania) on 20 -21 Aug 1968. � (You can read an interesting declassified archival transcript of a phone conversation between Dubcek & Brezhnev, in which the latter puts pressure on the former to reverse the changes brought by the Prague Spring from the following link: http: //www 2. gwu. edu/~nsarchiv/nsa/publications/ DOC_readers/psread/doc 81. htm ) 29

� Dubcek called upon the population not to resist the invasion, & apart from relatively minor incidents resistance took the form of nonviolent protest, including the use of semi-humourous actions such as cartoons & removal of roadsigns so that invading forces would take the wrong roads. The invasion was not solely criticized in the West. In fact, Romanian leader Cawusecsco publicly criticized the inasion & even in the USSR there was an unprecedented & embarrasing (for the authorities) protest in Moscow’s Red Square by 8 Soviet citizens holding a Czechoslovak flag & banners. � Though arrested & first taken to Moscow, Dubcek was not immediately removed from his official position as party leader. The Soviets were aware that public sentiment was not on their side. However, once things had calmed, Dubcek was (April 1969) removed & replaced by the more loyally pro-Soviet Gustav Husak who remained in power for the next 2 decades, maintaining an unpopular policy of «normalization» that reversed Dubcek’s reforms except for that relating to the federal separation of the Czech & Slovak republics. Dubcek spent most of his remaining working life as a forestry official. 30

� Husak followed an essentially orthodox and strongly pro-Soviet line. The economiy was centrally planned, though emphasis was given to consumer goods & satisfying material demands of the populace. In terms of political liberties however, no trace of the freedoms of expressions that Dubcek had tried to institute werre to remain. It was with the comming to power of Gorbachev that the economnic & political stagnation / status quo in Czechoslovakia was really challenged. 31

� Some limited dissent against the communist regime was maintained after the 1960’s notably through the spread of amateurly produced & secretly spread literature known as «samizdat» , yet despite underlying discontent, on the surface little mass opposition emerged till the late 1980’s. A few more visible expressions such as «Charter 77» demanding human rights (& formed in the wake of the arrest of a rock band known as «Plastic People of the Universe» regarded as a subversive influence of western culture), did not really reach the level of mass protest. However, on Nov. 17, 1989, (international student day), following developments in other E European states, a larger scale student protest was held. Permission had been given to the students to gather because they were part of a young communist organization, but in reality they no longer held sympathy for the party. Though later proved to be false, rumour spread that a student had been killed, which enflamed later public opinion & protest therafter very rapidly escalated into a virtual revolt against the regime by the population. 200, 000 people took to the streets of Prague on the 19 th, 500, 000 the following day. 32

� On 24 th much of the communist leadership resigned & as protest spread, parliament ended the communist monopoly on power on 30 Nov. Ten days later President Husak resigned having first appointed a new government controlled by a non-communist majority. Demonstrations continued, more as a guarantee that there would be no reverese, rather than because of any serious communist resistance. � By the end of the year the now aging Dubcek had been declared speaker of parliament, while Vaclav Havel, a long-standing dissident who had led many of these demonstrations, became President. Dubcek (who had supported the protests & spoke at street demonstrations) soon, however, was to fall on different sides of an ethnic divide with Havel, not so much as a result of their own personal wishes, but as a result of the strong Slovak demand for separate sovereignty. 33

� Established as a state with 2 major ethnic groups in 1917 following the collapse of the Austrian Empire, relations between Czech & Slovaks (about 1 Slovak for every 2 Czechs), had been relatively good. Many Slovaks, including Dubcek, had played a prominent role in government & had following amongst both ethnic groups. � Following the Velvet Revolution, however, some Slovak political parties began to push for greater decentralization of the federation, leading in fact to what many Czechs saw as a confederation. Some Czech leaders now claimed that it would be better to be completely independent rather than to have a framework so loose that it could not function, & negotiations were begun between the Slovak and Czech governments to end their federal union as of 31 Dec 1992. � Many strongly opposed the division though it could not be stopped, and the last Czechoslovak President, Vaclav Havel actually resigned rather than accept this. 34

http: //abook. org/abandoned-communist-party-headquarters-in-bulgaria/ 35

� The end of communism in Bulgaria followed a somewhat different pattern to that of other E European cases occuring ultimately through what some have described as a «palace revolution» or «palace coup» . � Wegs & Ladrech themselves refer to Bulgaria as the «Dutiful Ally» . Unlike Poland, Hungary or Czechoslovakia, there was never any notable challenge to Soviet hegemony during the Cold War, and this is partly explaianble through the longstanding historical & cultural ties. � Bulgaria shared a similar Orthodox & Slavic cultural heritage & Russia had for long acted as a «protector» in the Balkans, especially during the process of Bulgaria gaining independence from the Ottoman Empire. � During Communist rule Bulgaria essentially followed the lead of the USSR both in terms of implementing policy & strategically. 36

� For 35 years Bulgaria was ruled over by Todor Zhivkov (from 1954 -1989). 37

� Overall, Zhivkof’s tenure was until the latter years remarkably stable both politically & economically. Bulgaria benefited in particular from having an economy more compatible with that of the USSR & subsidies from the USSR esp for oil. � Standards of living generally improved, but by the 1980’s stagnation was becomming increaisngly evident & the Soviet Union facing it’s own economic difficulties was less willing to show costly favouritism towards Bulgaria. Nevertheless, there appeared to be no major challenge to Zhivkof, though more discontent became evident during the Gorbachev era. � Zhivkof also faced harsh criticism internationally due to his efforts in the 1980’s to «Bulgarize» the country substantial ethnic Turkish minority (c. 10% of population. Many hundreds of thousands were forced to flee the country, others imprisoned or persecuted in terms of religious freedoms & right to use their own language). 38

On 10 th Nov. 1989 Zhifkov was forced to resign by other leading members of the communist party. Several factors can be said to have played a role in this «palace coup» . 1) Gradually declining popularity & legitimacy 2) Weakening authority due to aging 3) Difficulty adjusting to the liberalization of Gorbachev 4) Communist Party leaders recognition of the international trend & desire to pre-empt more serious challenge & maintain their privieleged positions in a post-communist society Following the removal of Zhivkof the Communist Party itself (without the extent of domestic pressure witnessed in other cases) began to introduce radical economic & political changes. Eliminating the Party’s monopoly of power, organizing competitive elections & liberalizing the economy. Their strategy could be considered successful, because in elections held in June 1990 the reformed & renamed Communist Party gained 211 out of 400 seats! Governments have since fluctuated, but though Bulgaria is now a member of both the EU & NATO, former communists & their offspring continue to play a leading role in Bulgarian politics. � 39

40

� Some believed that while others fell one-by-one, the Romanian Communist regime under Nicolae Ceausescu would stay standing. True, Romania was in some ways a unique case, & Ceausescu’s regime fell last, yet fall it did. � Following the death of Stalin post-WWII Romanian Communist Party leader Gheorghe Gheorghiu-Dej had increasingly followed the national communist line, rejecting the largely peripheral economic role the Soviets foresaw for Romania & working to develop industry as well as opening-up increasing trade & diplomatic ties with the West. Ceausescu furthered this line of emphasizing Romanian sovereignty, publicly decrying the Soviet-led invasion of Czechoslovakia in 1968 (even though he opposed the changes themselves) & ignoring the Soviet-led boycot of the Los Angeles Olympic Games in 1984 & emphasizing Romanian national uniqueness. � Yet in many ways Ceausescu became increasingly Stalinist, relying on the most extensive secret police service (the Securitate) in Eastern Europe & developing a personality cult unrivalled among the communist states. 41

� As with other communist states, the early 1980’s were not a very easy time economically for Romania, but instead of relaxing conditions, Ceausescu resolved to rapidly pay back the country’s foreign debt (c. $10 billion) before the end of the decade so as fortify Romania’s independence. This goal was actually achieved shortly beore his fall from power, however at a very heavy cost for the population. � All of Romania’s best agricultural produce was exported to earn foregin currency, the population having to make do with the remainder through a rationing system that provided them, when available with inferior products. Shortages of energy & water supplies were notorious & discontent mounted under the surface. � That Ceausescu was in the meantime spending massive amounts on lavish & extravagant projects, (such as the building of the world’s largest & most expensive administrative building, the «People’s Palace» in Bucharest), was not appreciated by the almost destitute public. 42

� In mid-Dec 1989, there had still been no sign of mass opposition emerging. However, on the 16 th members of the Hungarian minority in the city of Timisoara reacted to the auths orders to remove in response to an attempt by the government to evict a pastor of the Hungarian Reformed Church pastor Laszlo Tokes who had been critical of Romanian human rights on Hungarian TV. The protest grew to include non. Hungarians also & when they continued the following day the army was sent in to crush the protests. By word-of- mouth and overseas broadcasters news of developments in Timisoara spread to other cities. � On 21 st Dec Ceasusescu organized a large crowd of about 100, 000 to speak to (most forcefully bussed in) in the capital Bucharest. These were supposed to be loyalists who would demonstrate support for Ceausescu, Romanians would all watch live on TV, & he put the blame on previous protests on «fascist agitators» . Yet gradually the crowd began to turn against him, booing & hissing & openly demonstrating for an end to his rule. 43

Developments over the next few days are still somewhat unclear. What is known is that the number of protestors grew, Ceausescu & his wife Elena tried to escape on a helipcopter, & bloody fighting developed between loyalist & opposition forces, most notably of the «National Salvation Front» (an organization that emerged from within the Party). � On 22 nd the Ceausescu’s were arrested, very quickly put on trial & executed by firing squad on 25 th Dec. About 1, 000 had died in fighting by then. Unclearly accounted for fighting continued for several days thereafter & about 3, 000 more were killed, & it appears this fighting was largely due to rivalry as to the post-Ceausescu transition. On the 27 the fighting suddenly stopped & the National Salvation Front (which included many former-communists & their offspring) began to convert Romania into a political system with competitive elections and a capitalist economy. � 44

Psir 206

Psir 206 Psir 206

Psir 206 Psir 426

Psir 426 Psir 426

Psir 426 Psir 426

Psir 426 Psir 426

Psir 426 Psir 426

Psir 426 Psir 426

Psir 426 Psir 426

Psir 426 A small child slides down the four frictionless slides

A small child slides down the four frictionless slides A spring loaded gun shoots a plastic ball

A spring loaded gun shoots a plastic ball Connecting europe facility 2021-2027

Connecting europe facility 2021-2027 Horizon europe slides

Horizon europe slides Me gustan me encantan (p. 135)

Me gustan me encantan (p. 135) Ee 206

Ee 206 Comp 206

Comp 206 221 bce

221 bce Prop 206 arizona pros and cons

Prop 206 arizona pros and cons Csce 206

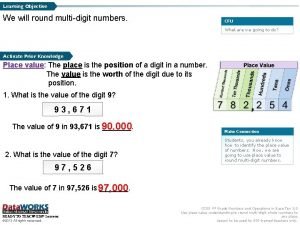

Csce 206 Round 787 206 to the nearest ten

Round 787 206 to the nearest ten 206 tl

206 tl Sn en 206

Sn en 206 206 ossa

206 ossa 206 to binary

206 to binary Tipos de huesos dibujos

Tipos de huesos dibujos Econ 206

Econ 206 Comp 206

Comp 206 Comp 206

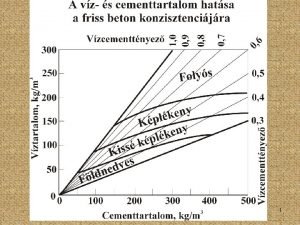

Comp 206 Cnom beton

Cnom beton En 206-1

En 206-1 206 ptt

206 ptt Plan bus 206

Plan bus 206 Ee 206

Ee 206 206-684-0268

206-684-0268 Stat 206

Stat 206 Comp 206

Comp 206 Political science and history relationship

Political science and history relationship Difference between sociology and political science

Difference between sociology and political science Plenty for beautification political cartoon

Plenty for beautification political cartoon History also history physical

History also history physical Caráter significado

Caráter significado Architecture runway slides

Architecture runway slides Classificadores em libras slides

Classificadores em libras slides Slides mania.com

Slides mania.com Fraction splat google slides

Fraction splat google slides