Proxy data sources Ice cores l l Data

- Slides: 12

Proxy data sources: Ice cores l l Data from ice cores is extracted in a number of ways. Oxygen isotopic analysis gives an idea of the temperature at which the ice was deposited (since O 18 has a higher vapour pressure, it is preferentially deposited). . In warmer conditions, more O 18 will be found in the polar ice (Craig, 1961 ; Morgan, 1982). Atmospheric gas concentrations can be extracted from bubbles formed by the closing off of air pores as firn turns to ice. (Raynaud & Lorius, 1973). Physical variations in ice structure such as crystal size, incidence of melts and number/structure of bubbles give an idea of temperature and frequency of melt periods or deposition (Langway, 1970; Koerner, 1977).

Proxy data sources: Dendroclimatology l l The pattern of growth of trees is laid down within their structure, providing a high-resolution (annual) picture of climatic variables in the Holocene. Much can be deduced from growth bands – the thickness corresponds to the favourability of climatic conditions (light, temperature, rainfall, windspeed) (Bradley, 1985; Fritts, 1976). l The density of the bands says much about the growing season (latewood is much denser than earlywood) (Schweingruber et al. , 1978). l l Isotopic analysis of the bands can also give us information about the climatic conditions. (Epstein et al. , 1976). By studying a number of trees in an area of a similar age, a statistically sound analysis of conditions can be obtained.

Proxy data sources: Oceanic sediments l Preferential uptake of O 18 under cool conditions by fossilized plankton allows analysis of the temperature of deposition by isotopic analysis. (Urey, 1948). l Species assemblages show variation in the number of warm- and cold-water plankton species. (Williams & Johnson, 1975) l l Morphological variations are expressed by a number of species in response to climatic variables. (Kennett, 1976). The content of terrigeneous material in sediments corresponds to continental weathering. Consequently, the purity of the calcareous ooze gives a strong indication of the extent of weathering. (Hays & Perruzza, 1972). l The chemical and physical processes affecting the inorganic sediments prior to deposition correspond to particular climate regimes. (Kolla et al. , 1979).

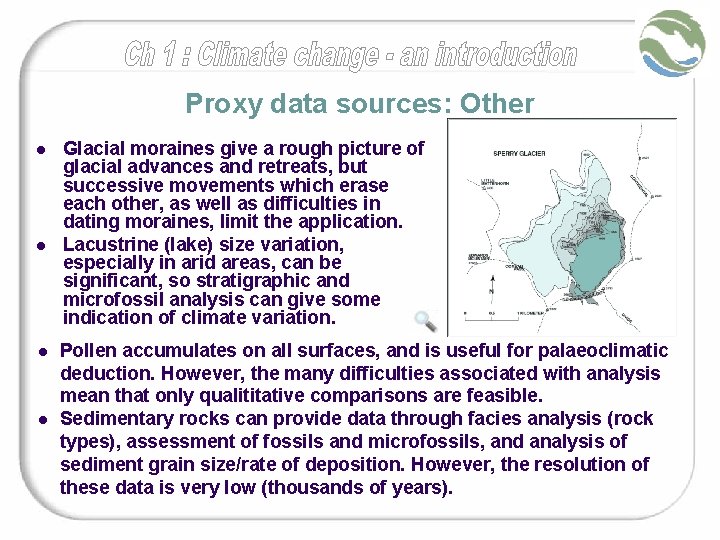

Proxy data sources: Other l l Glacial moraines give a rough picture of glacial advances and retreats, but successive movements which erase each other, as well as difficulties in dating moraines, limit the application. Lacustrine (lake) size variation, especially in arid areas, can be significant, so stratigraphic and microfossil analysis can give some indication of climate variation. Pollen accumulates on all surfaces, and is useful for palaeoclimatic deduction. However, the many difficulties associated with analysis mean that only qualititative comparisons are feasible. Sedimentary rocks can provide data through facies analysis (rock types), assessment of fossils and microfossils, and analysis of sediment grain size/rate of deposition. However, the resolution of these data is very low (thousands of years).

The role of climate models l l l Once historical and palaeoclimatological data have been gathered, we have some idea of: - How the climate has changed in the past - What atmospheric and biological conditions were associated with this change This allows us to build and test models of the interaction of climatic variables These models allow us some capacity to then establish how a given change in certain factors will affect future climate. This becomes the basis for assessment of the current state of the environment We will go into this in more detail in chapter 2.

Evidence for change • So, what evidence is there for anthropogenic • • • change? By comparing current data and measurements with historical and palaeclimatological data, we have obtained a good picture of the climate over the last several thousand years. It is clear that there has been a significant transformation of the climate over the last hundred years, and that the rate of change is increasing. Signal analysis and modelling has proved that this change cannot be attributed to processes other than human interaction with the environment.

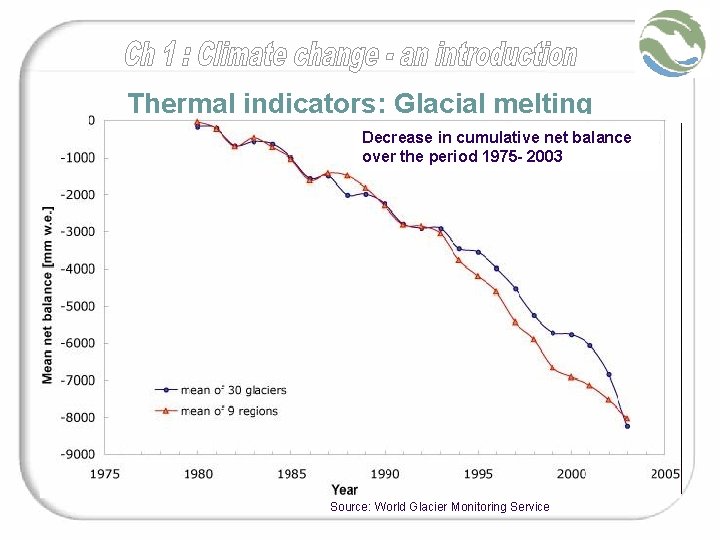

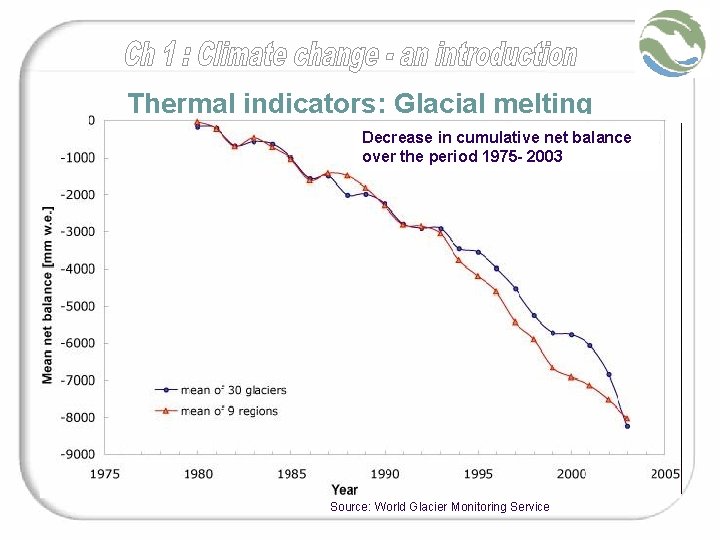

Thermal indicators: Glacial melting l l l Glacial retreat over a 98 year period in Glacier National Park , USA. Glacier National Park Archives/F. E. Mathes (1900), USGS/L. Mc. Keon (1998) l Decrease in cumulative net balance The change in size of glaciers is measured by their over periodgain/loss 1975 - 2003 of mass at mass balance: the netthe annual the glacier surface per unit surface area. This is useful because it measures the contribution of glacial melt to sea level rise. Almost all glaciers have been shown to be retreating. (IAHS (ICSI)/UNEP/UNESCO, 1998) Some glaciers in Norway and New Zealand are advancing, but this is because of increased precipitation due to warmer weather. Exposure of radiocarbon-dated ancient remains in high saddles in the Alps shows recession is reaching levels not seen for thousands of years This ice has not melted for thousands of years, hence the finding of the 5000 year-old Oetzal “ice man”. (IPCC, 2004) Source: World Glacier Monitoring Service

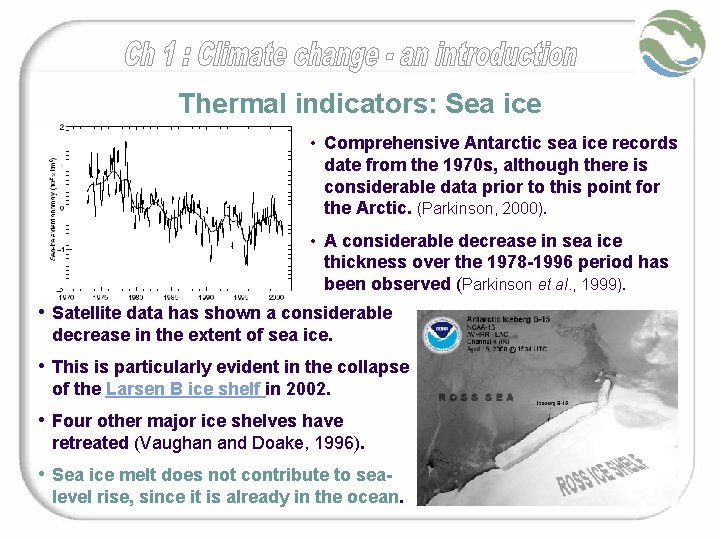

Thermal indicators: Sea ice • Comprehensive Antarctic sea ice records date from the 1970 s, although there is considerable data prior to this point for the Arctic. (Parkinson, 2000). • A considerable decrease in sea ice thickness over the 1978 -1996 period has been observed (Parkinson et al. , 1999). • Satellite data has shown a considerable decrease in the extent of sea ice. • This is particularly evident in the collapse of the Larsen B ice shelf in 2002. • Four other major ice shelves have retreated (Vaughan and Doake, 1996). • Sea ice melt does not contribute to sealevel rise, since it is already in the ocean.

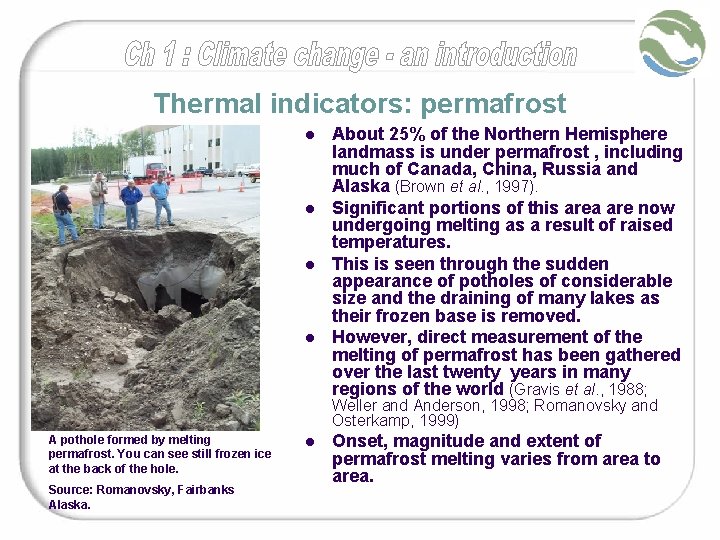

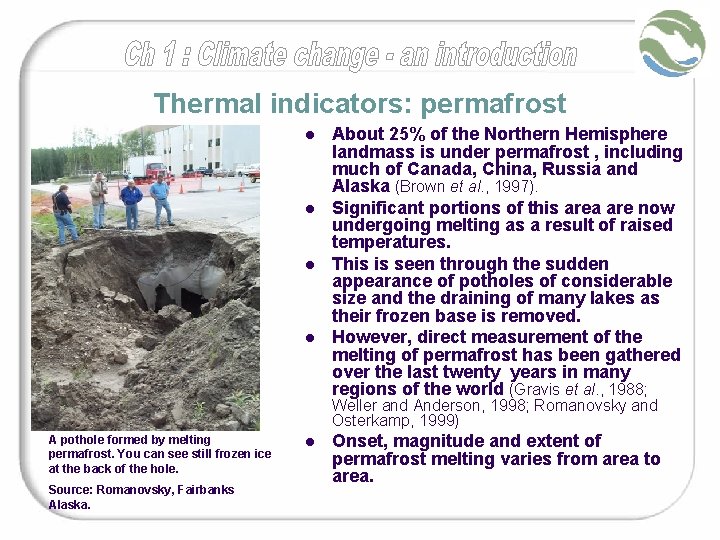

Thermal indicators: permafrost l l About 25% of the Northern Hemisphere landmass is under permafrost , including much of Canada, China, Russia and Alaska (Brown et al. , 1997). Significant portions of this area are now undergoing melting as a result of raised temperatures. This is seen through the sudden appearance of potholes of considerable size and the draining of many lakes as their frozen base is removed. However, direct measurement of the melting of permafrost has been gathered over the last twenty years in many regions of the world (Gravis et al. , 1988; Weller and Anderson, 1998; Romanovsky and Osterkamp, 1999) A pothole formed by melting permafrost. You can see still frozen ice at the back of the hole. Source: Romanovsky, Fairbanks Alaska. l Onset, magnitude and extent of permafrost melting varies from area to area.

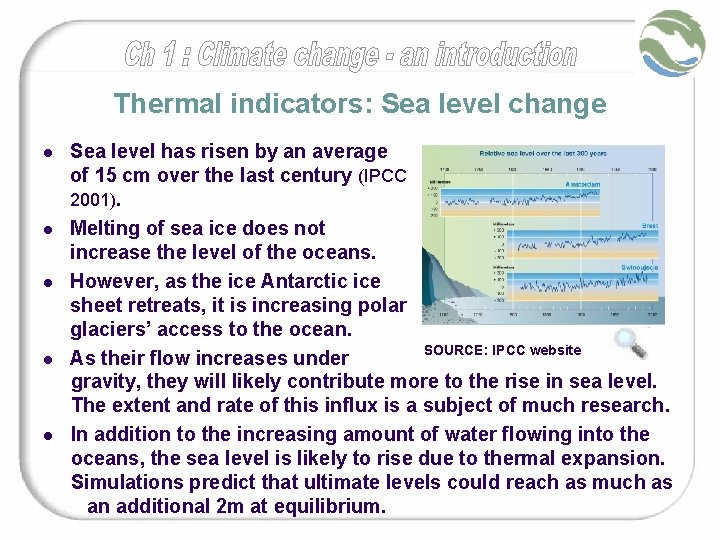

Thermal indicators: Sea level change l l l Sea level has risen by an average of 15 cm over the last century (IPCC 2001). Melting of sea ice does not increase the level of the oceans. However, as the ice Antarctic ice sheet retreats, it is increasing polar glaciers’ access to the ocean. SOURCE: IPCC website As their flow increases under gravity, they will likely contribute more to the rise in sea level. The extent and rate of this influx is a subject of much research. In addition to the increasing amount of water flowing into the oceans, the sea level is likely to rise due to thermal expansion. Simulations predict that ultimate levels could reach as much as an additional 2 m at equilibrium. .

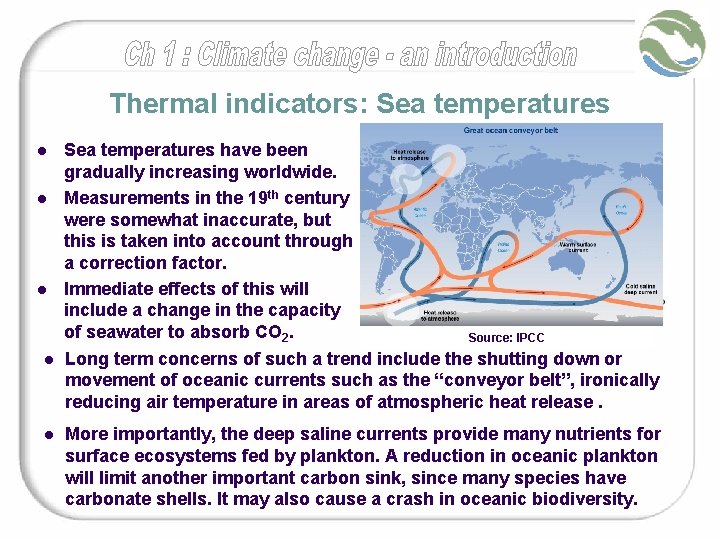

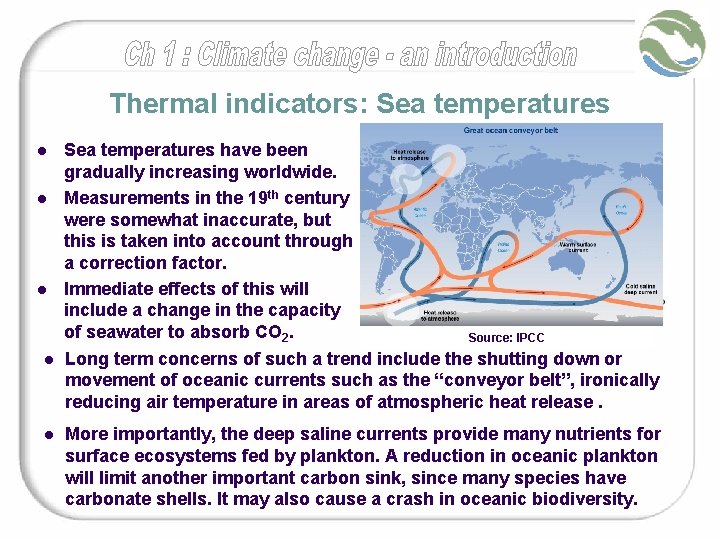

Thermal indicators: Sea temperatures l l l Sea temperatures have been gradually increasing worldwide. Measurements in the 19 th century were somewhat inaccurate, but this is taken into account through a correction factor. Immediate effects of this will include a change in the capacity Source: UK Meterological Office of seawater to absorb CO 2. Source: IPCC Long term concerns of such a trend include the shutting down or movement of oceanic currents such as the “conveyor belt”, ironically reducing air temperature in areas of atmospheric heat release. More importantly, the deep saline currents provide many nutrients for surface ecosystems fed by plankton. A reduction in oceanic plankton will limit another important carbon sink, since many species have carbonate shells. It may also cause a crash in oceanic biodiversity.

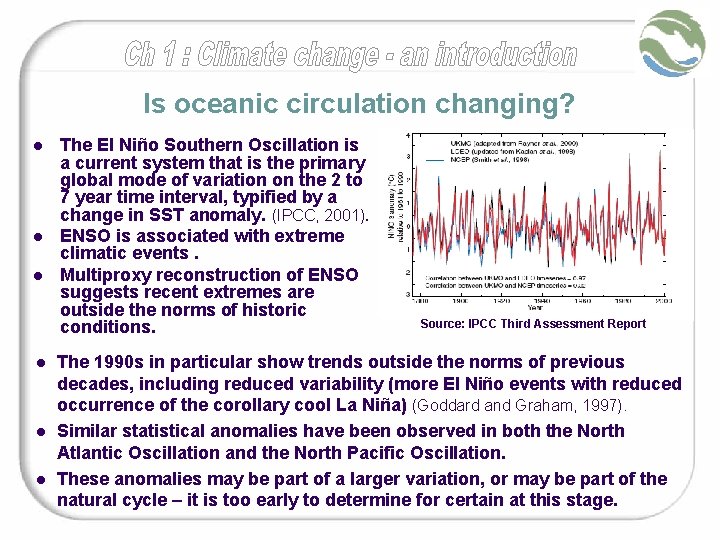

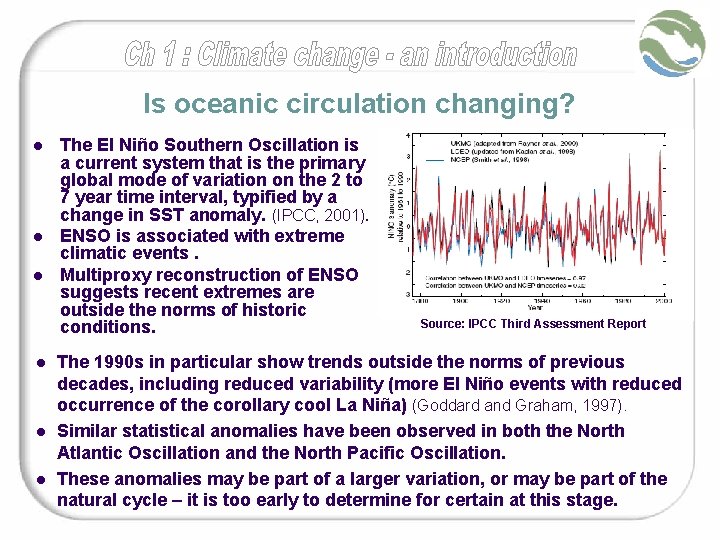

Is oceanic circulation changing? l l l The El Niño Southern Oscillation is a current system that is the primary global mode of variation on the 2 to 7 year time interval, typified by a change in SST anomaly. (IPCC, 2001). ENSO is associated with extreme climatic events. Multiproxy reconstruction of ENSO suggests recent extremes are outside the norms of historic conditions. Source: IPCC Third Assessment Report The 1990 s in particular show trends outside the norms of previous decades, including reduced variability (more El Niño events with reduced occurrence of the corollary cool La Niña) (Goddard and Graham, 1997). Similar statistical anomalies have been observed in both the North Atlantic Oscillation and the North Pacific Oscillation. These anomalies may be part of a larger variation, or may be part of the natural cycle – it is too early to determine for certain at this stage.