Protein structure Secondary structure helix sheet parallel and

- Slides: 43

Protein structure

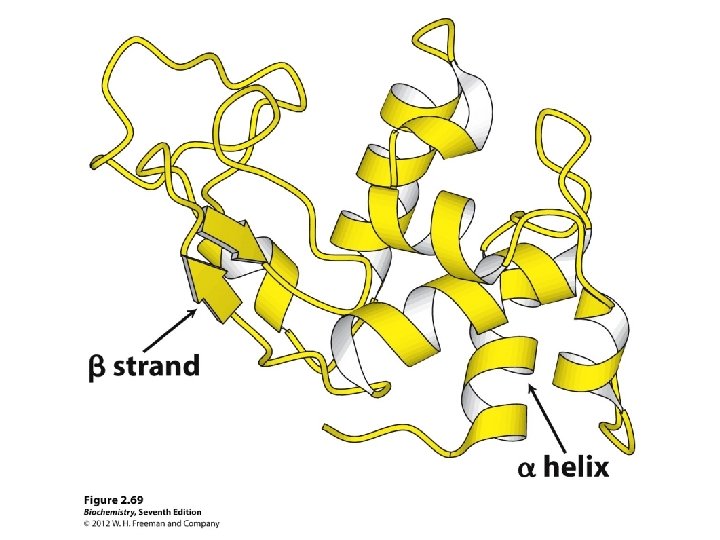

Secondary structure • α-helix • β-sheet: parallel and anti-parallel • β-turn • H-bonds between N-H and C=O in peptide backbone

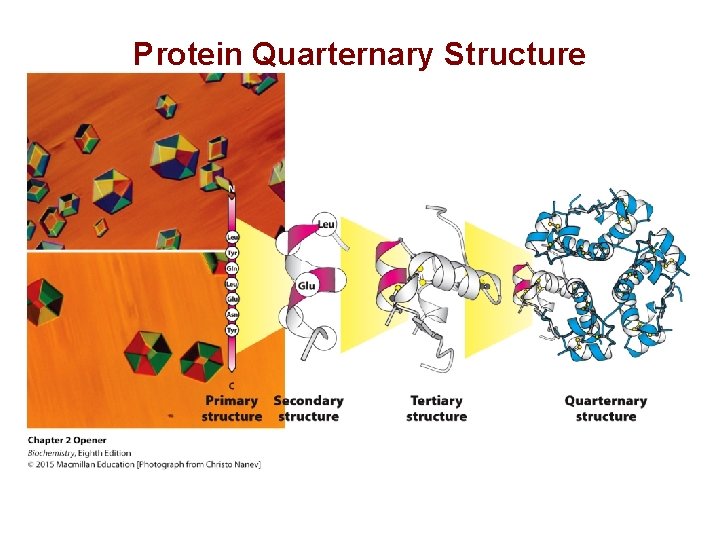

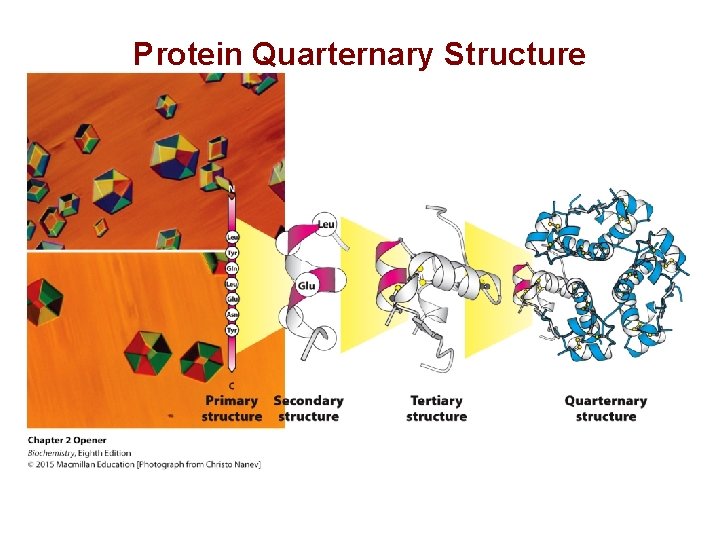

Protein Quarternary Structure

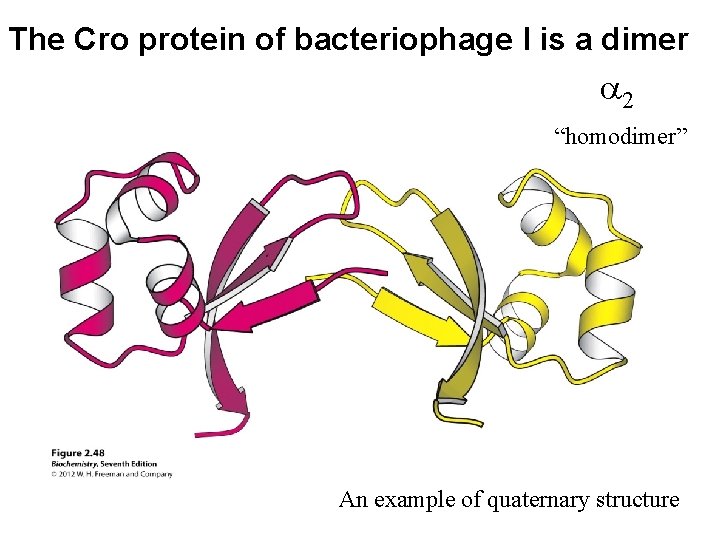

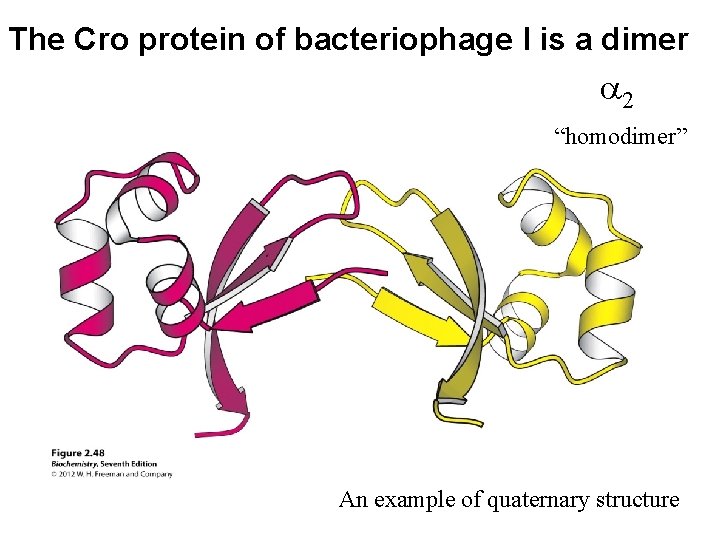

The Cro protein of bacteriophage l is a dimer a 2 “homodimer” An example of quaternary structure

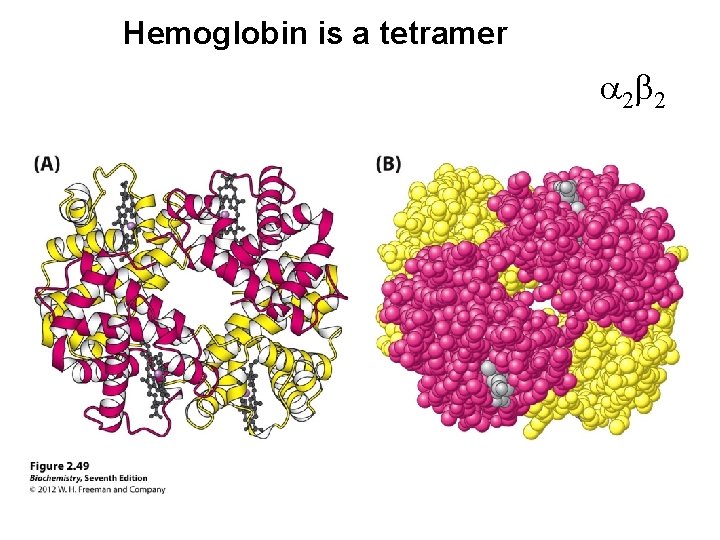

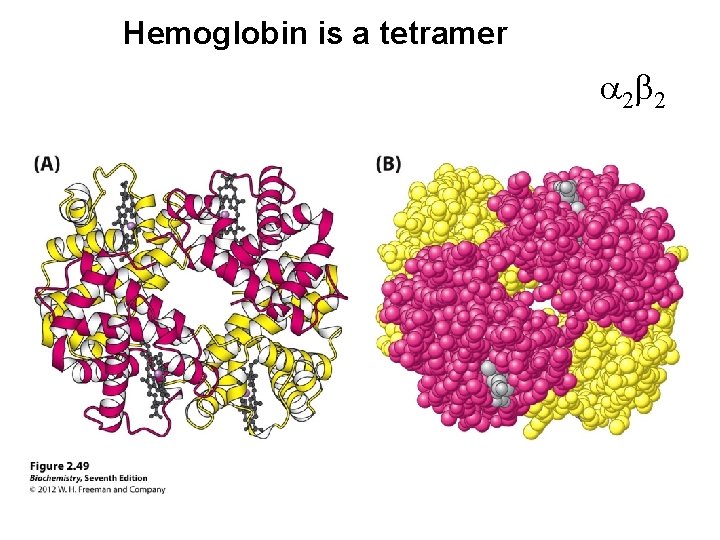

Hemoglobin is a tetramer a 2 b 2

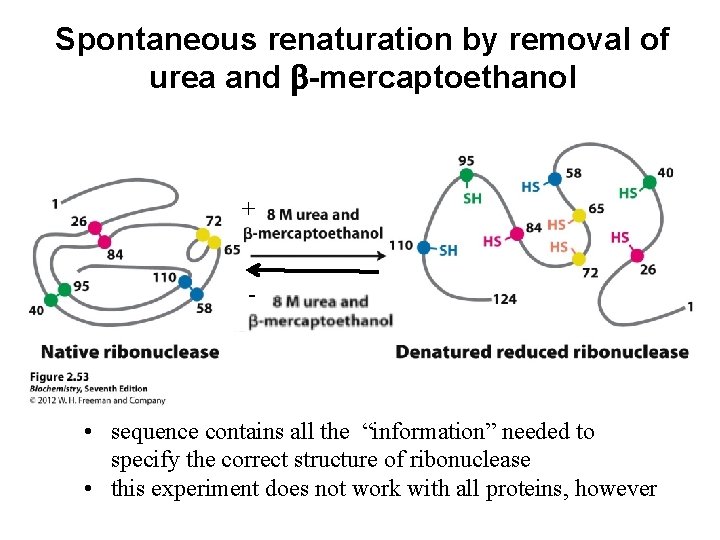

What determines three dimensional structure? Answer: Amino acid sequence How do we know this?

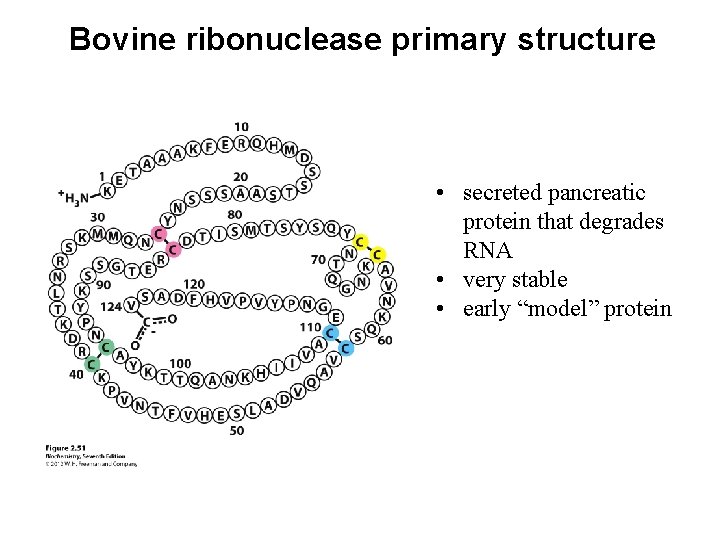

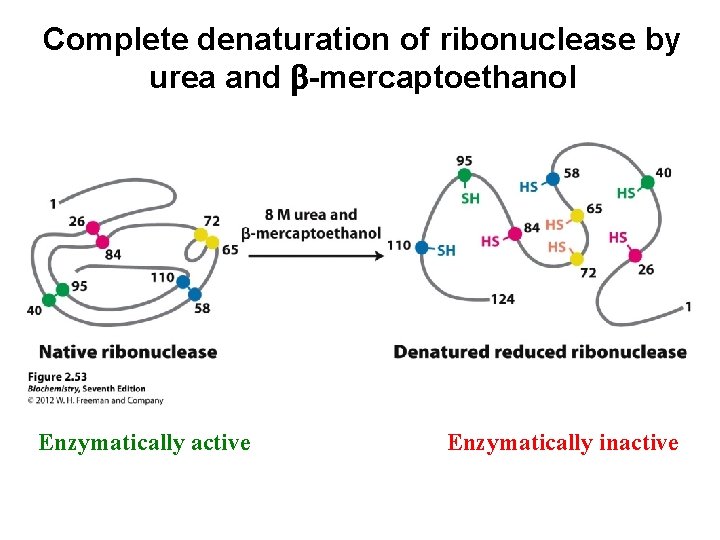

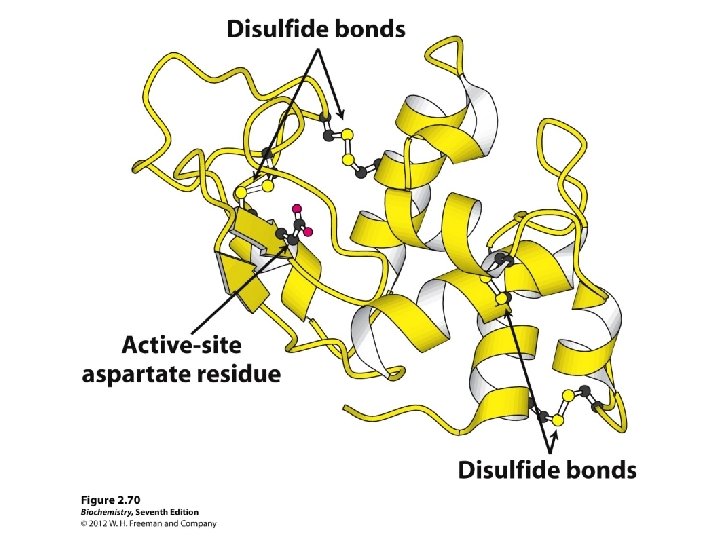

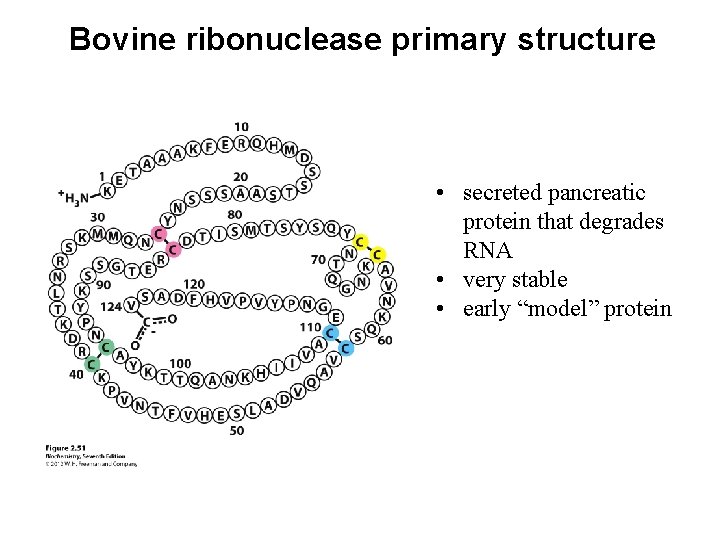

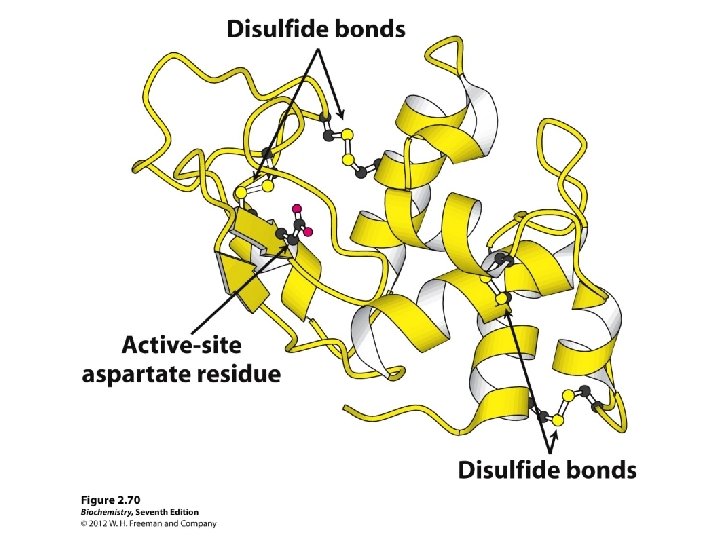

Bovine ribonuclease primary structure • secreted pancreatic protein that degrades RNA • very stable • early “model” protein

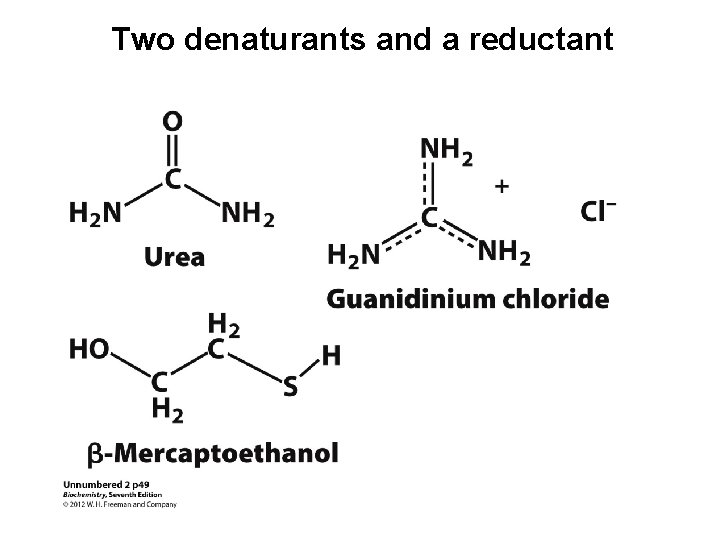

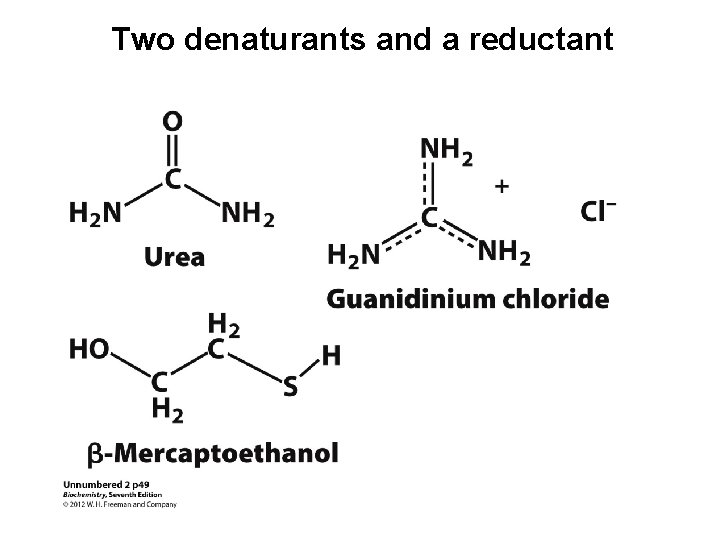

Two denaturants and a reductant

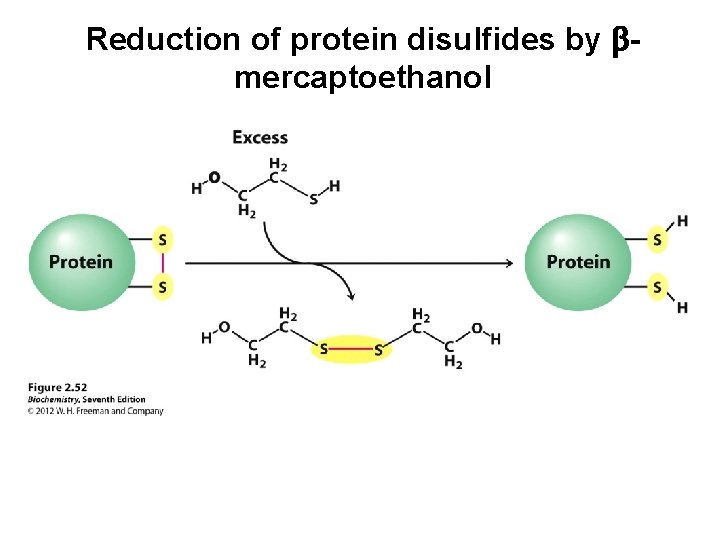

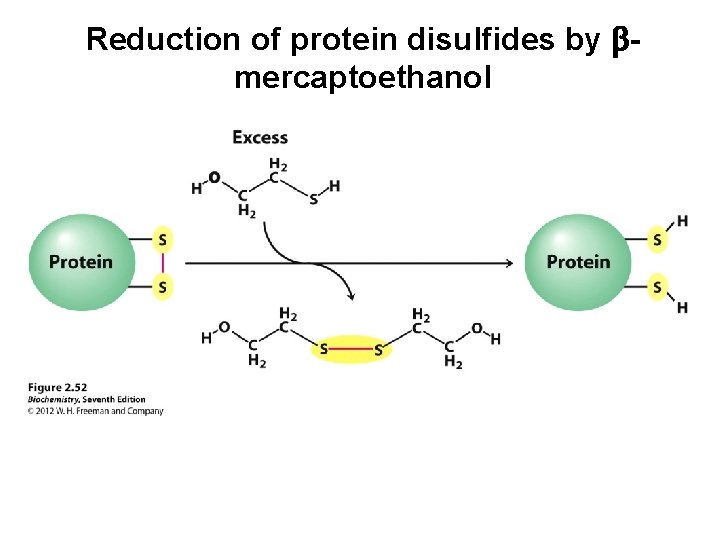

Reduction of protein disulfides by bmercaptoethanol

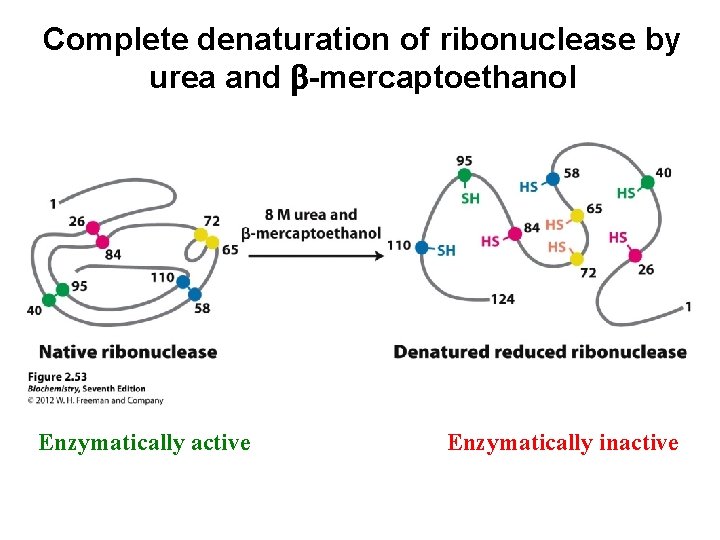

Complete denaturation of ribonuclease by urea and b-mercaptoethanol Enzymatically active Enzymatically inactive

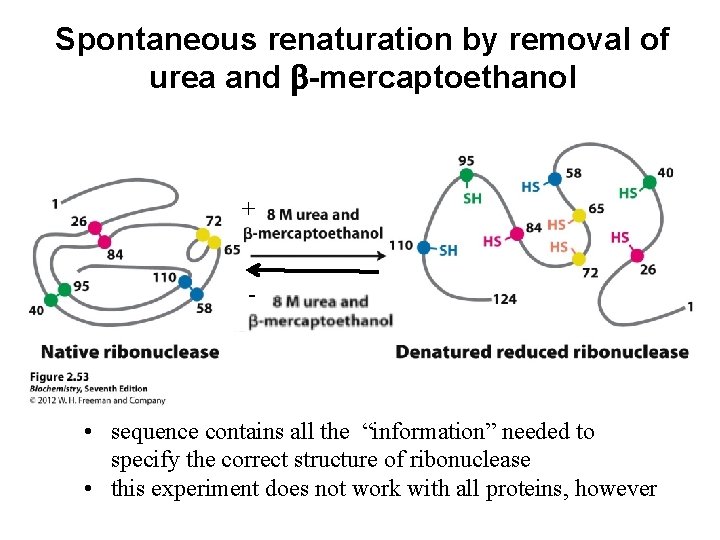

Spontaneous renaturation by removal of urea and b-mercaptoethanol + - • sequence contains all the “information” needed to specify the correct structure of ribonuclease • this experiment does not work with all proteins, however

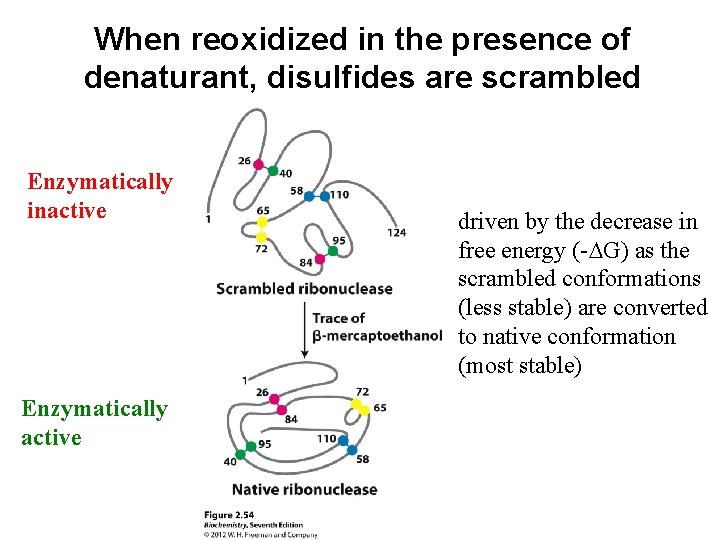

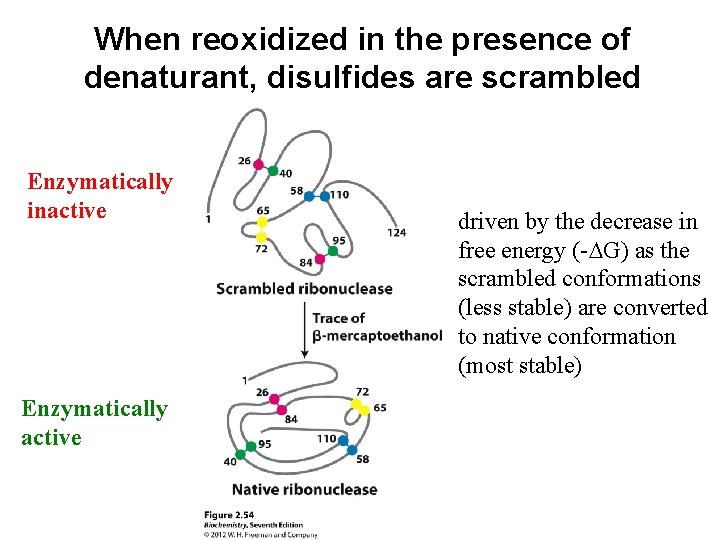

When reoxidized in the presence of denaturant, disulfides are scrambled Enzymatically inactive Enzymatically active driven by the decrease in free energy (-DG) as the scrambled conformations (less stable) are converted to native conformation (most stable)

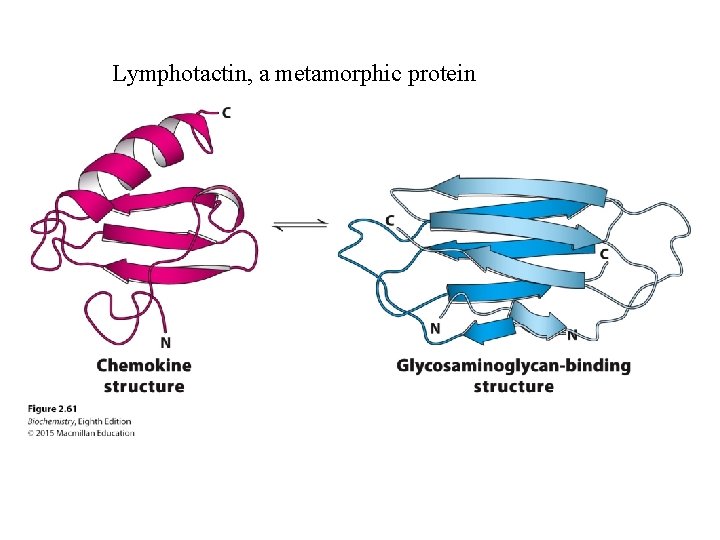

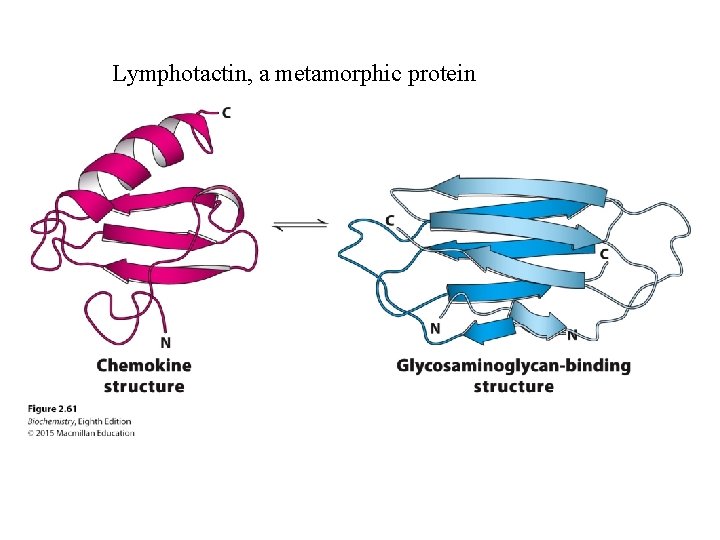

One amino acid sequence – one 3 D structure? • Most of the time • Exceptions: – Intrinsically unstructured proteins – Metamorphic proteins

Lymphotactin, a metamorphic protein

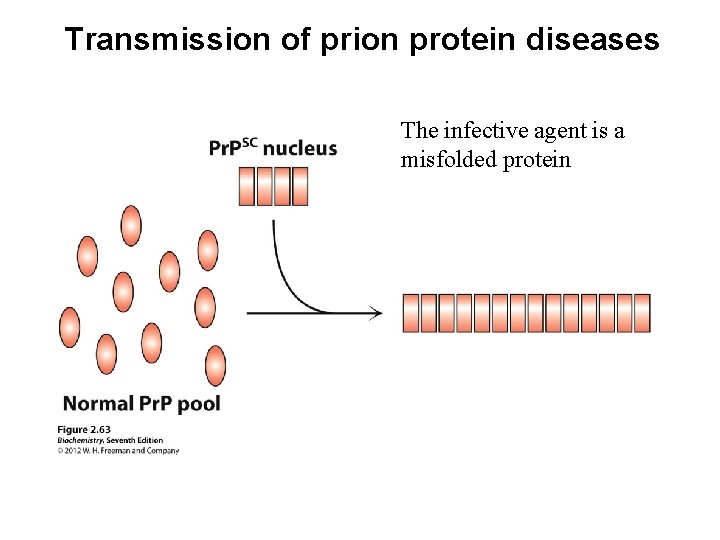

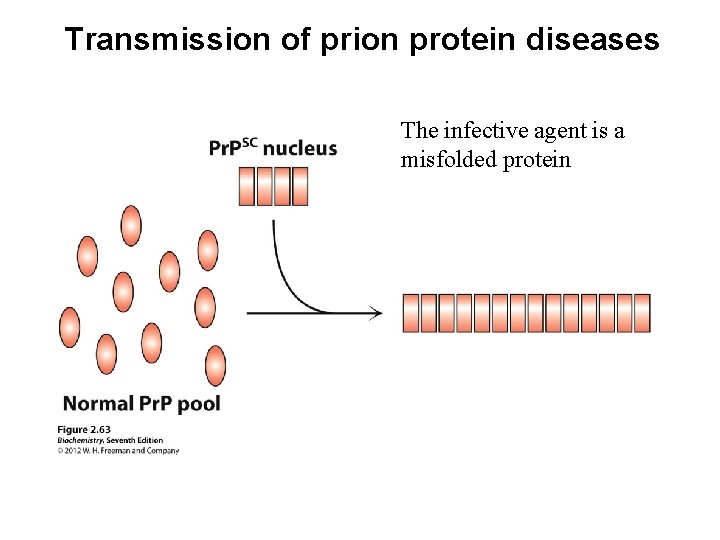

Protein misfolding: amyloid form of human prion protein Creutzfeld–Jacob disease (CJD) in humans; BSE (mad cow disease) in cows

Transmission of prion protein diseases The infective agent is a misfolded protein

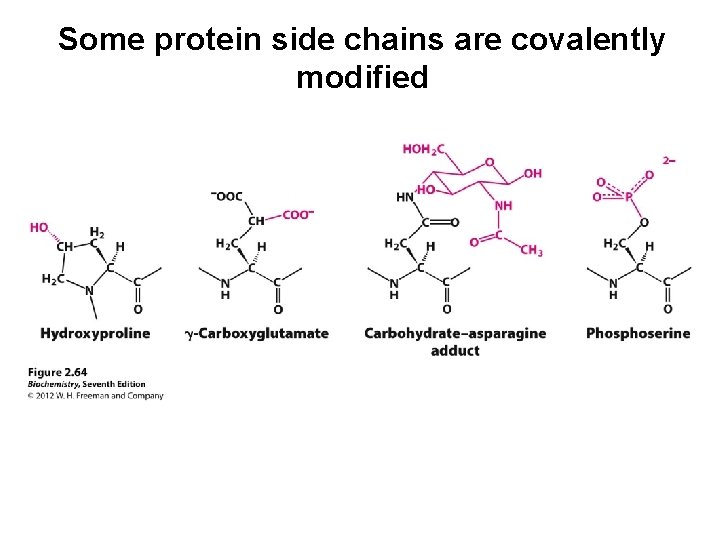

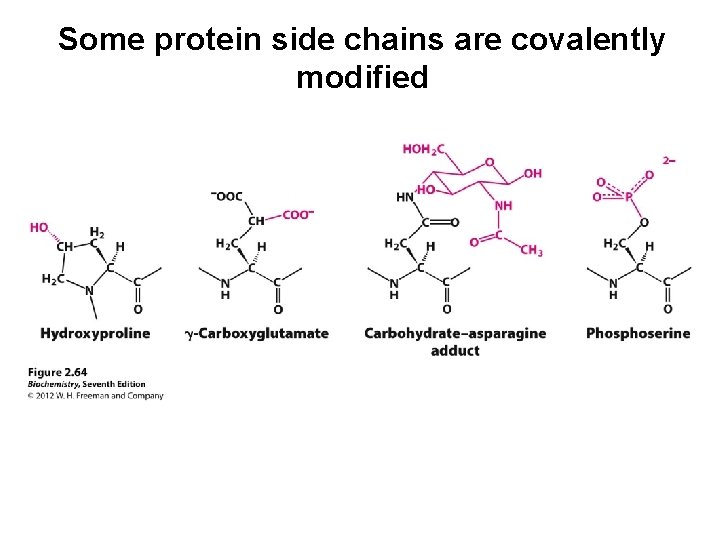

Some protein side chains are covalently modified

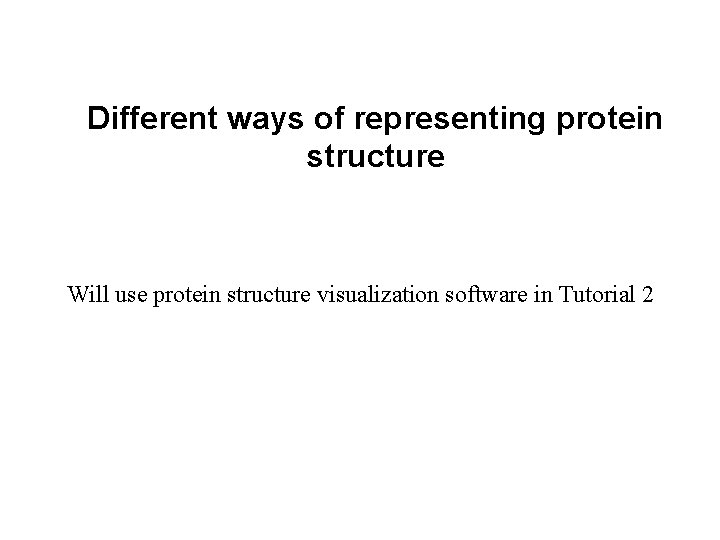

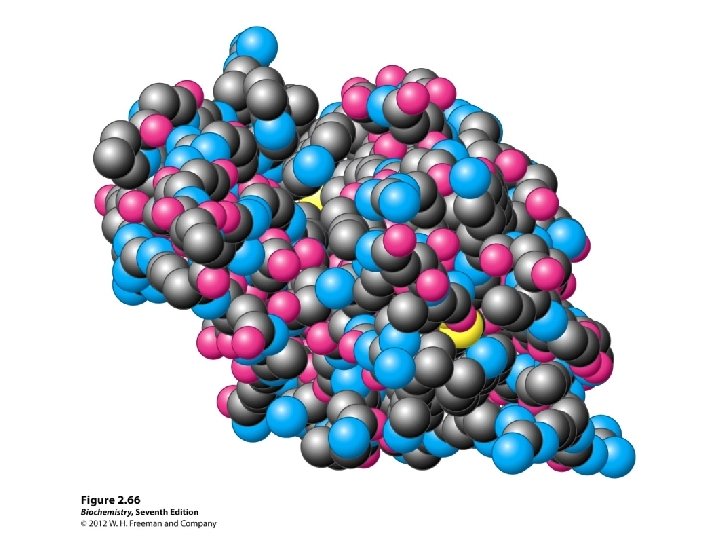

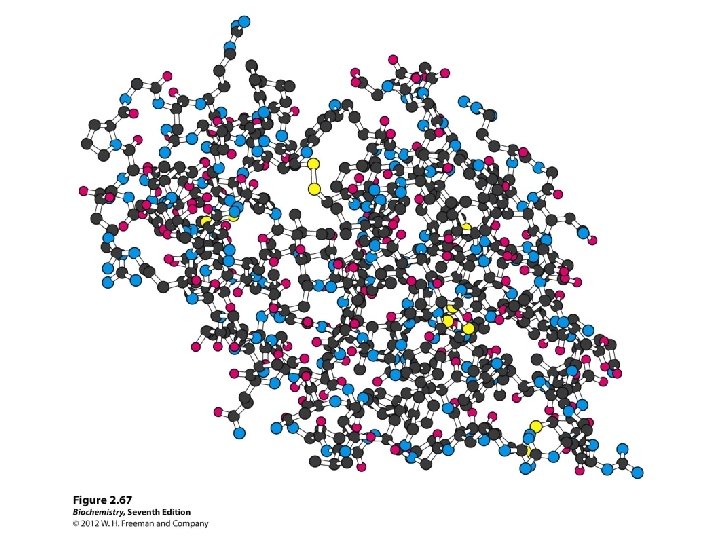

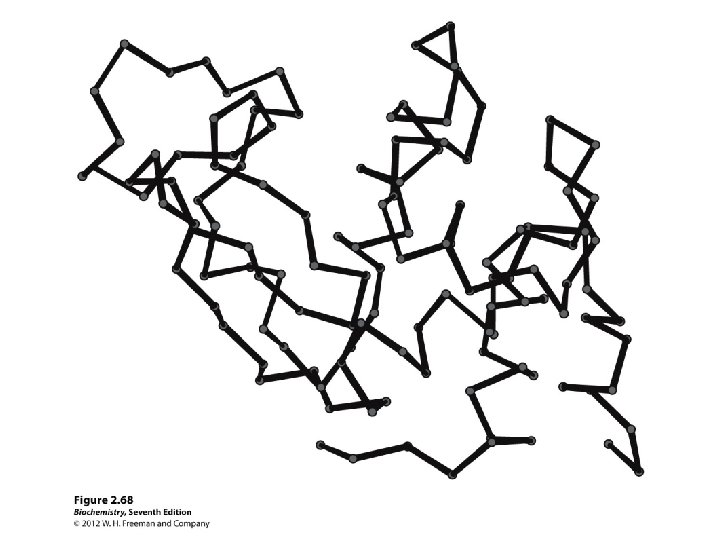

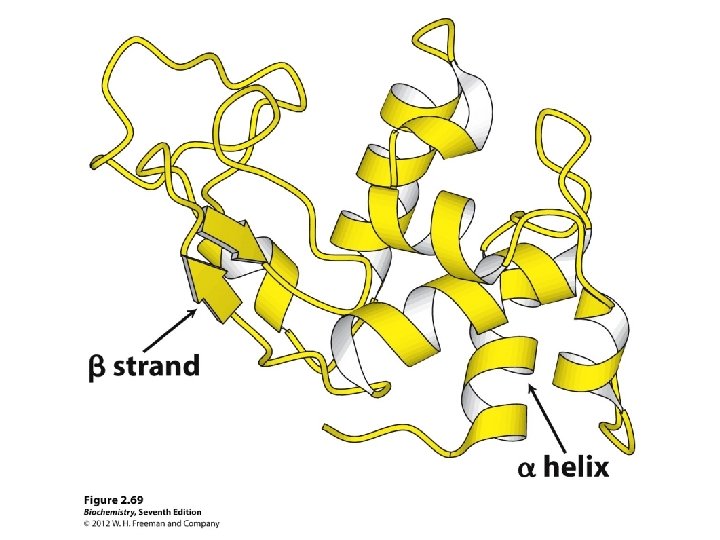

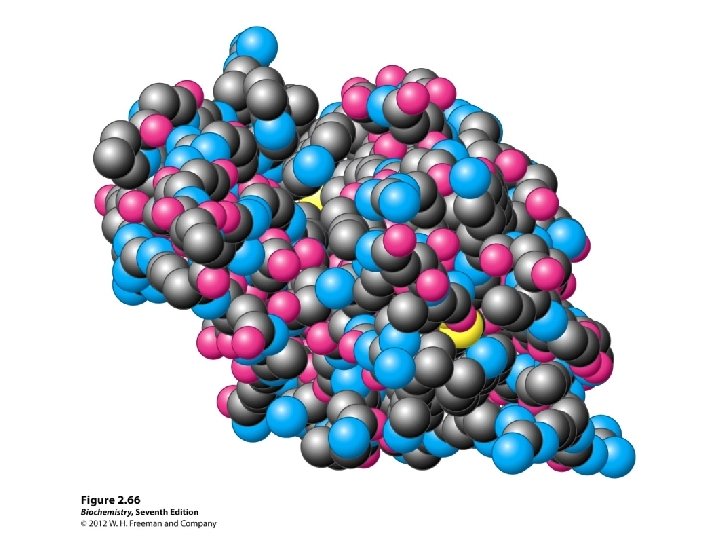

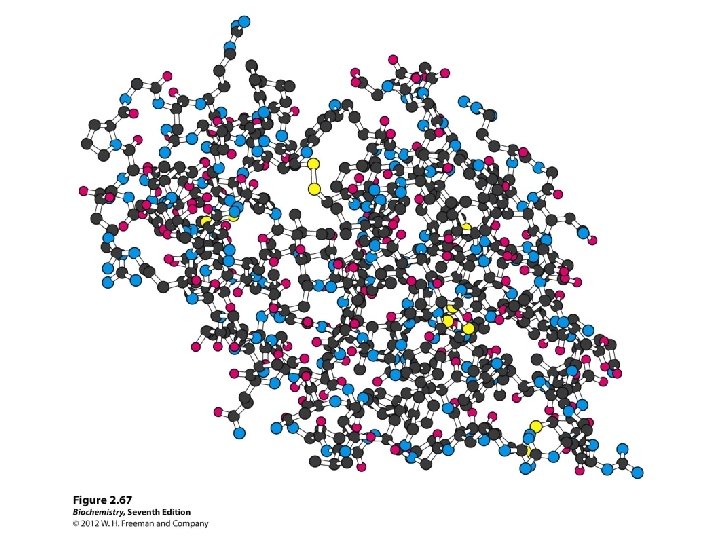

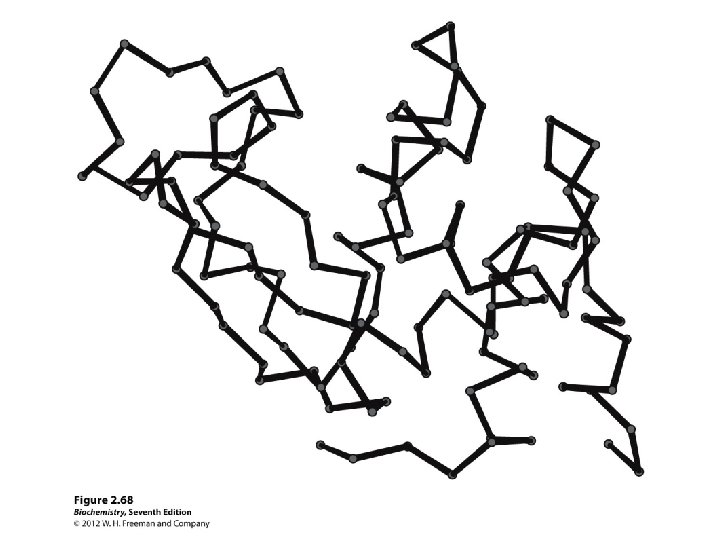

Different ways of representing protein structure Will use protein structure visualization software in Tutorial 2

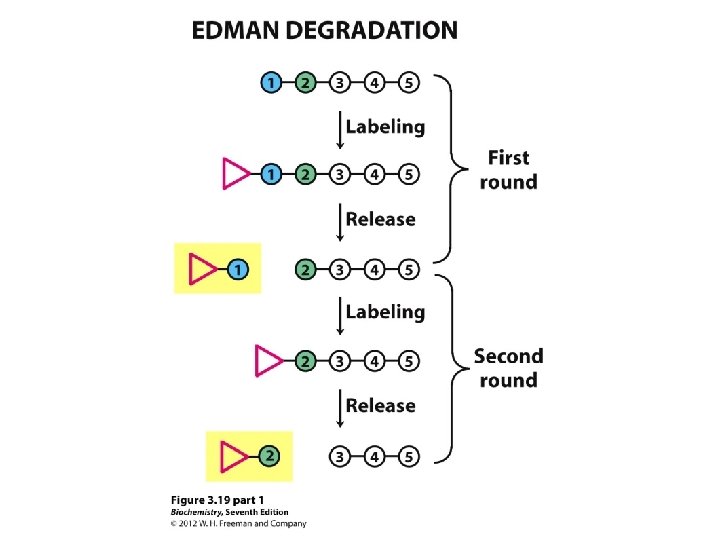

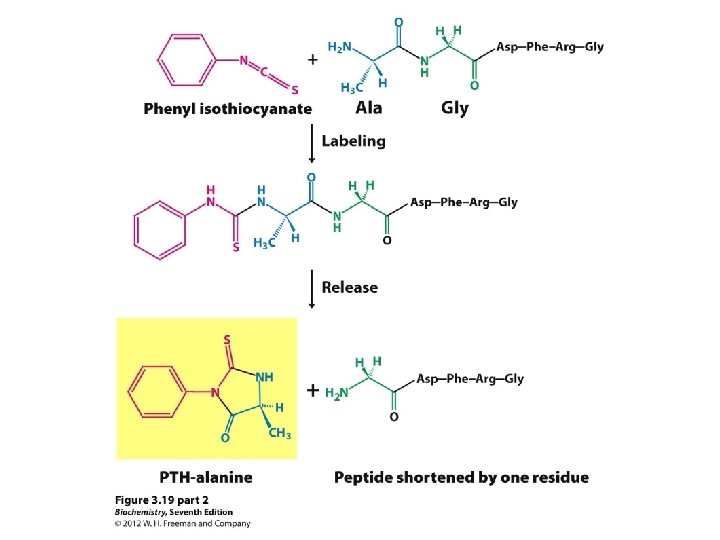

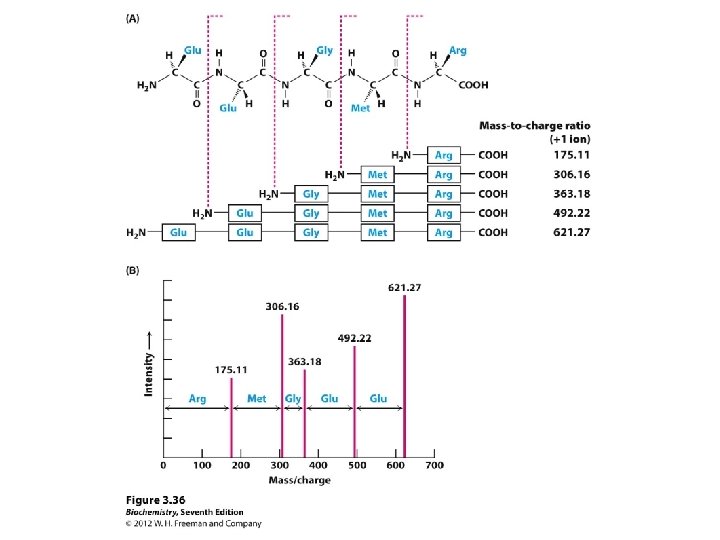

Determining amino acid sequences

Sequence comparisons

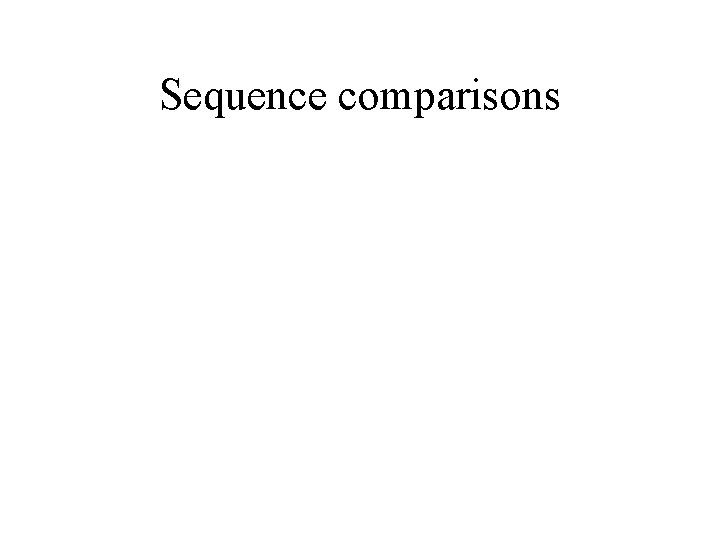

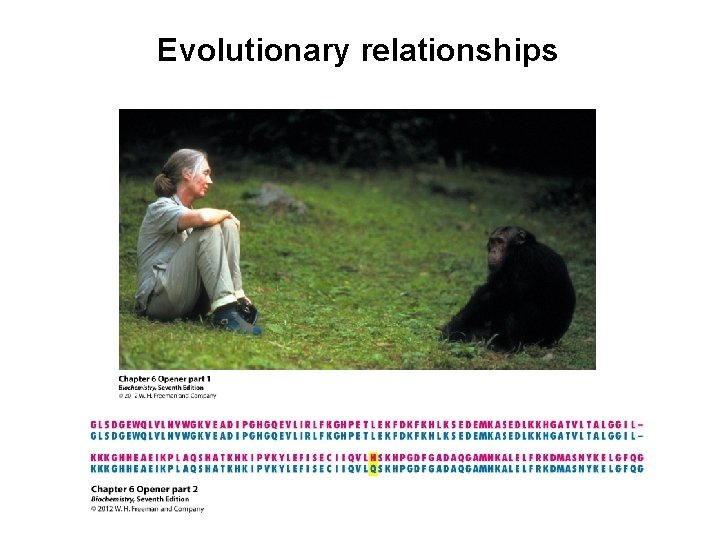

Evolutionary relationships

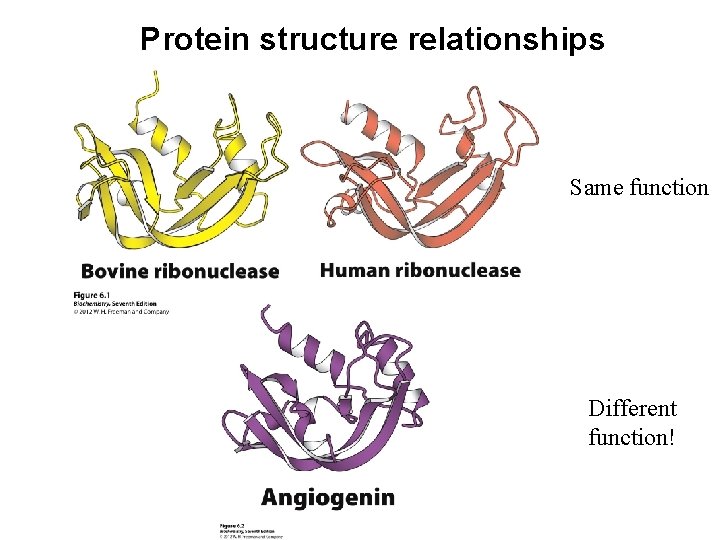

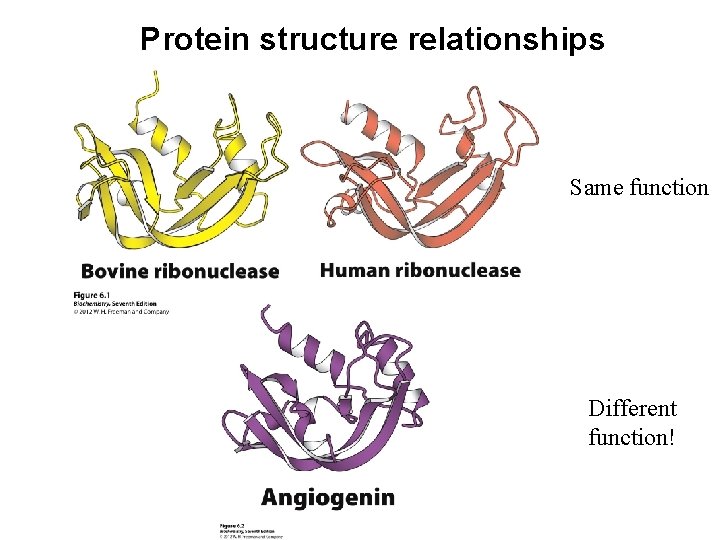

Protein structure relationships Same function Different function!

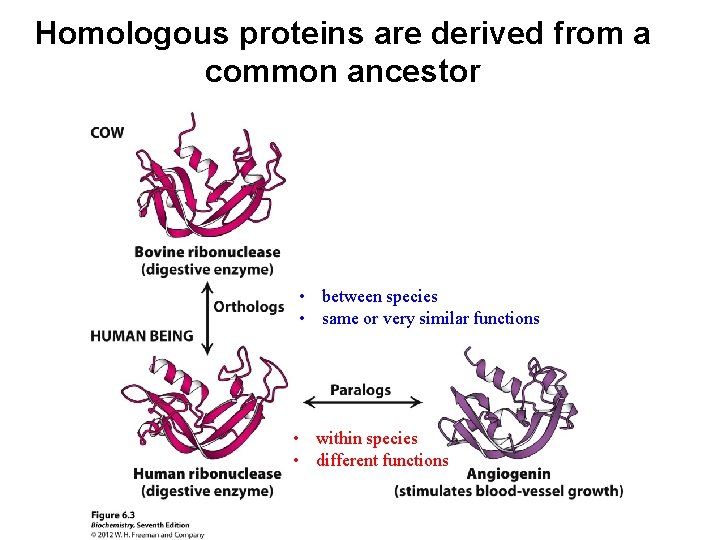

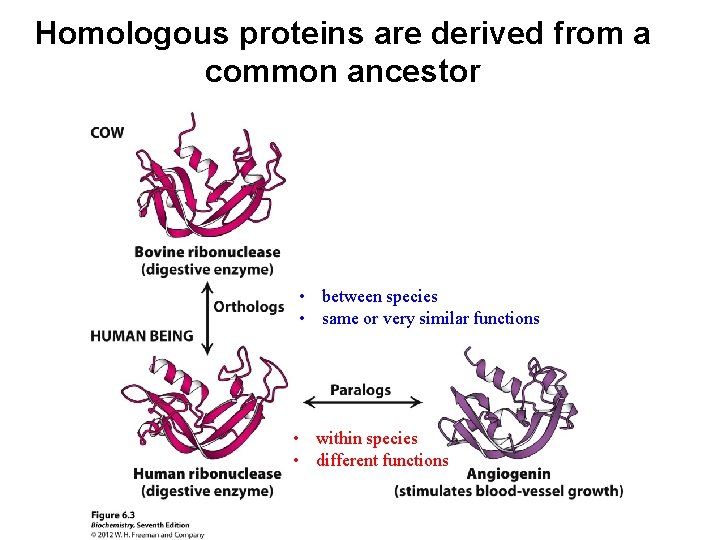

Homologous proteins are derived from a common ancestor • between species • same or very similar functions • within species • different functions

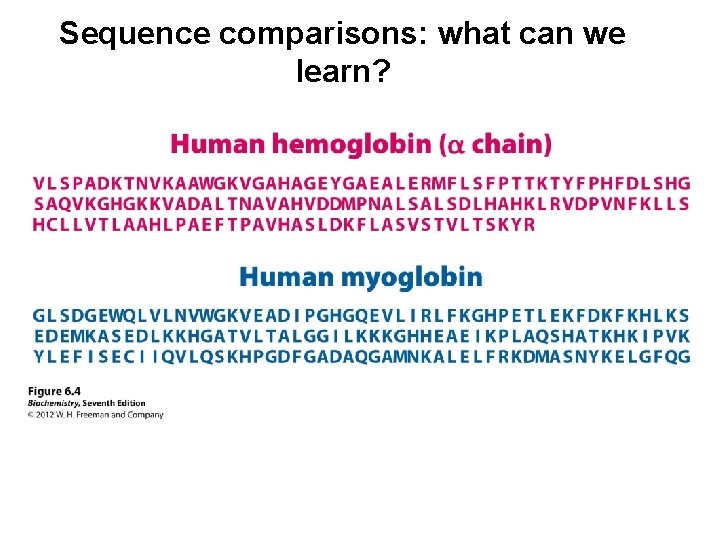

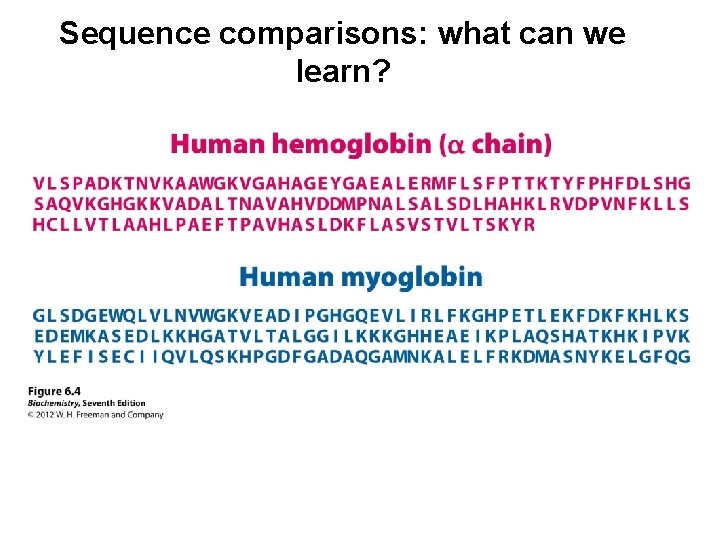

Sequence comparisons: what can we learn?

How do we find the “best” alignment? Simplest approach: “no frills”

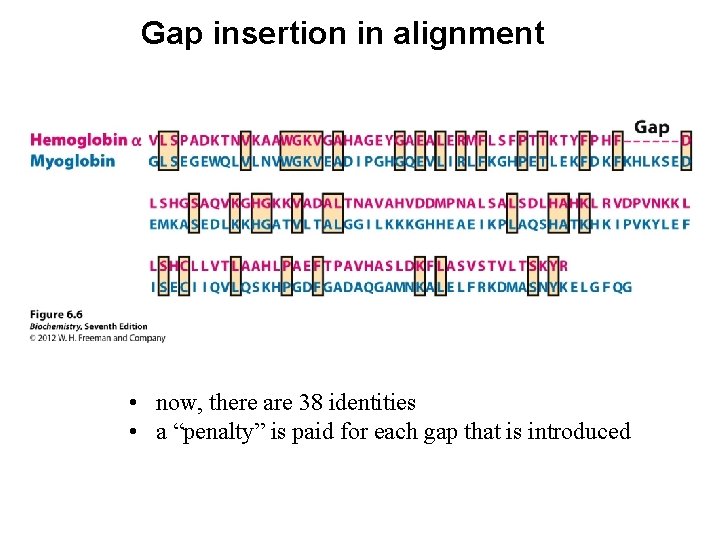

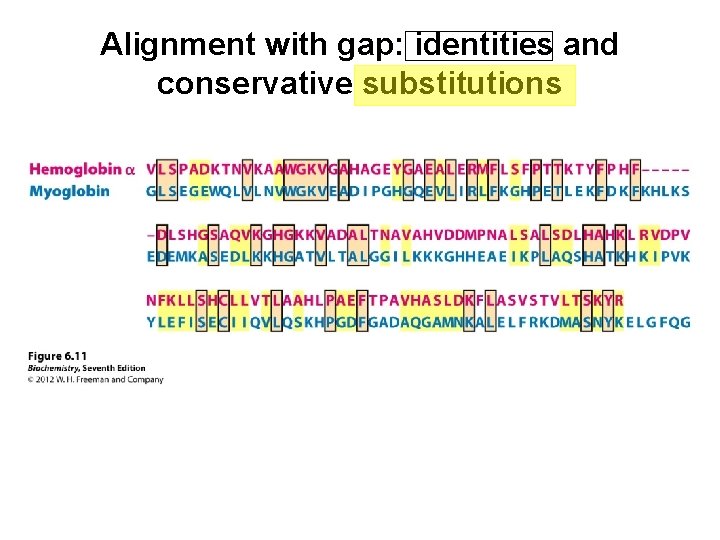

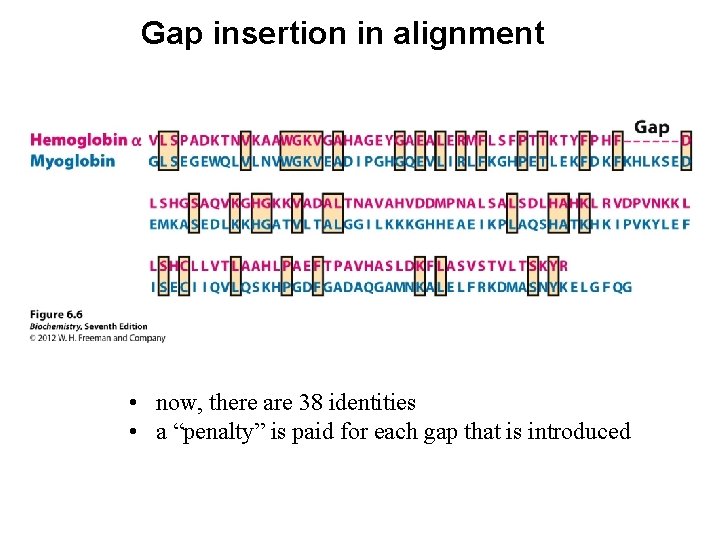

Gap insertion in alignment • now, there are 38 identities • a “penalty” is paid for each gap that is introduced

Scoring alignments scoring system: each identity between aligned sequences is counted as +10 points, whereas each gap introduced, regardless of size, counts for − 25 points.

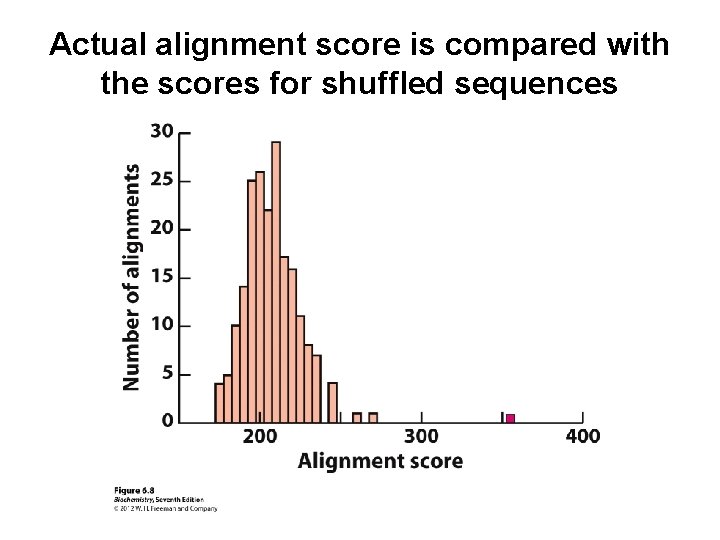

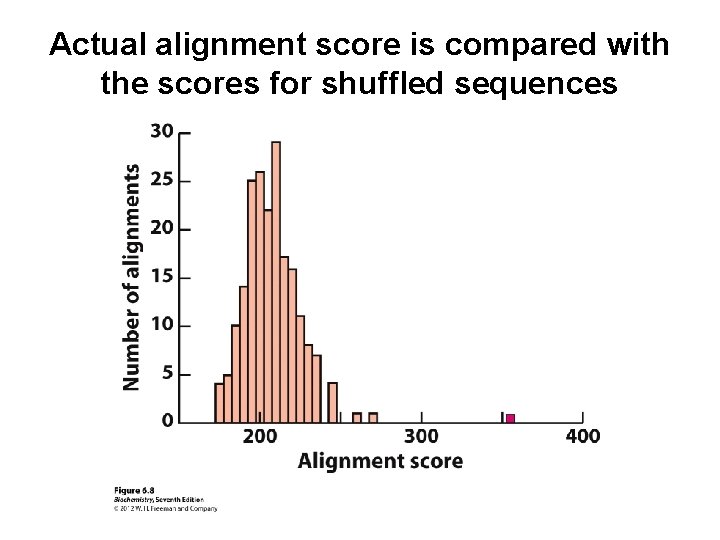

Shuffling is used to test for randomness of the alignment

Actual alignment score is compared with the scores for shuffled sequences

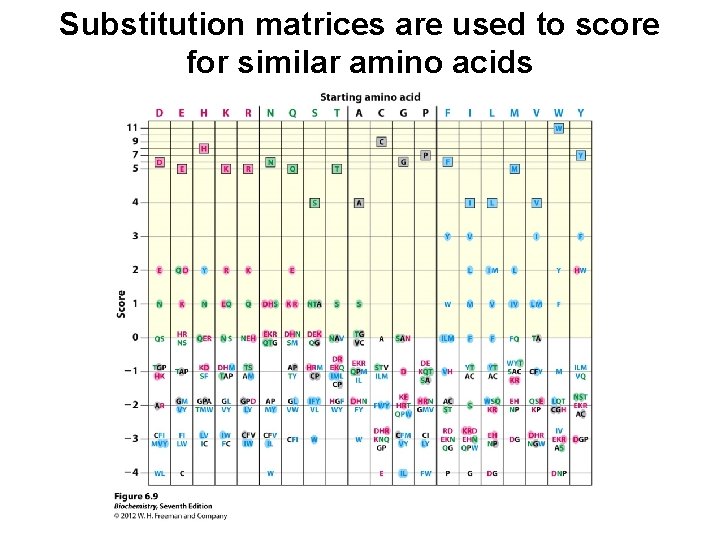

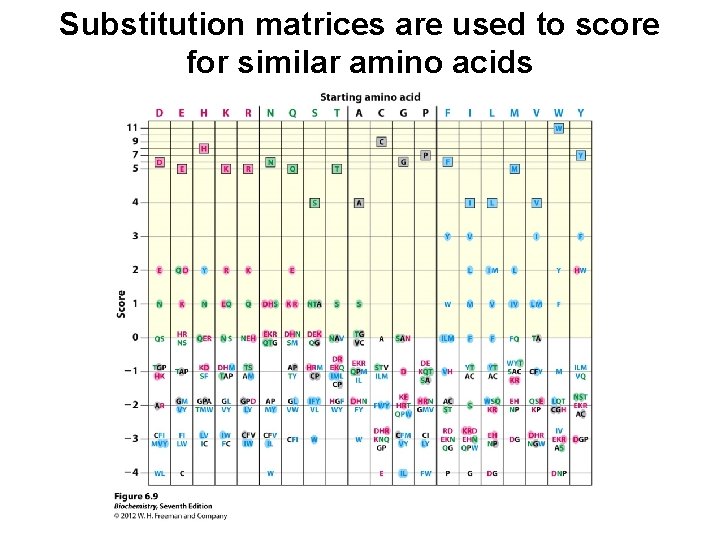

Substitution matrices are used to score for similar amino acids

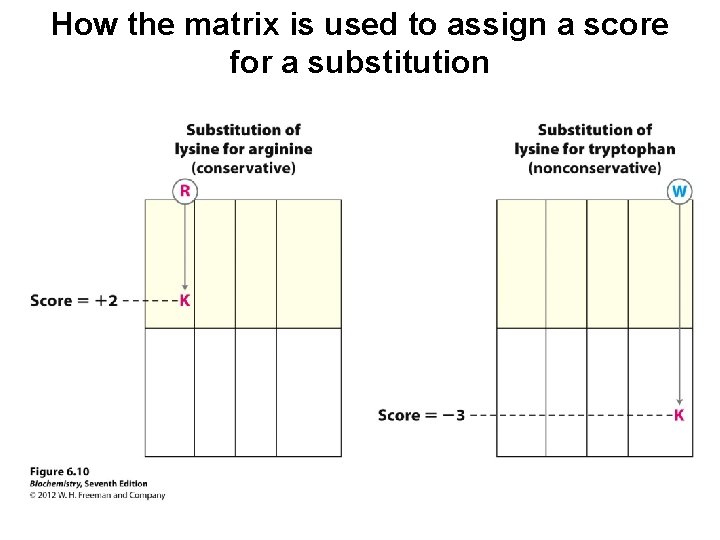

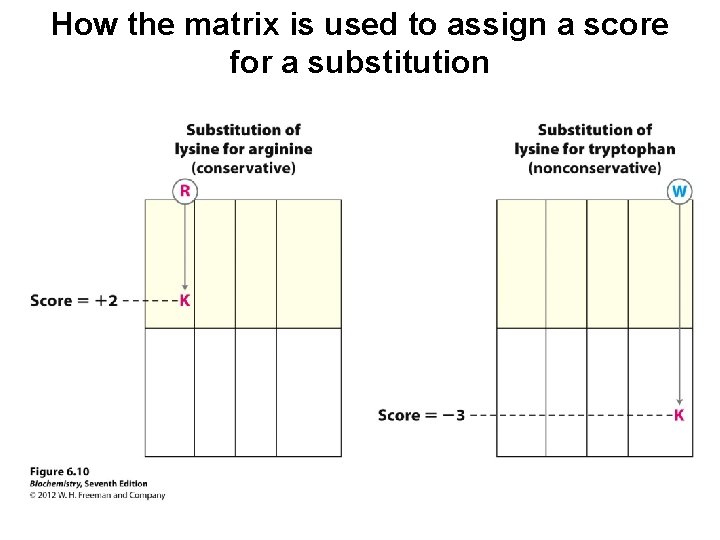

How the matrix is used to assign a score for a substitution

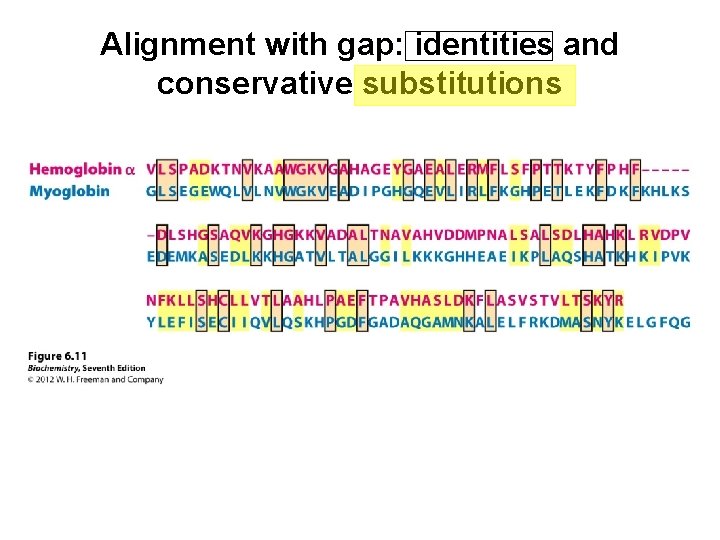

Alignment with gap: identities and conservative substitutions

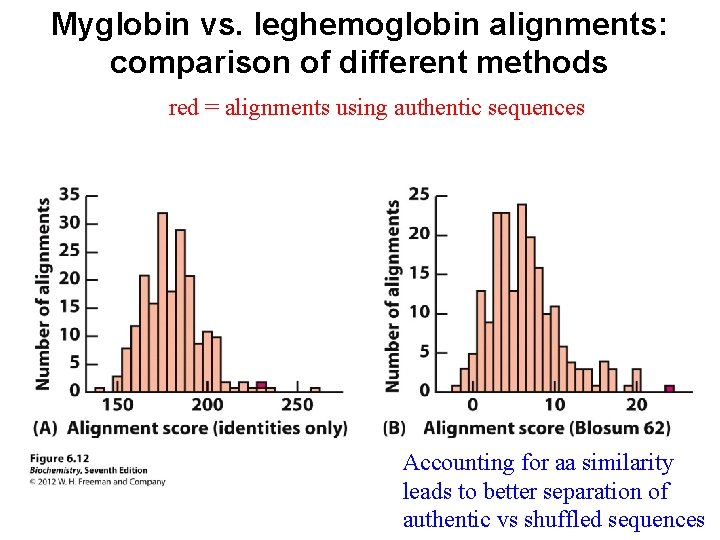

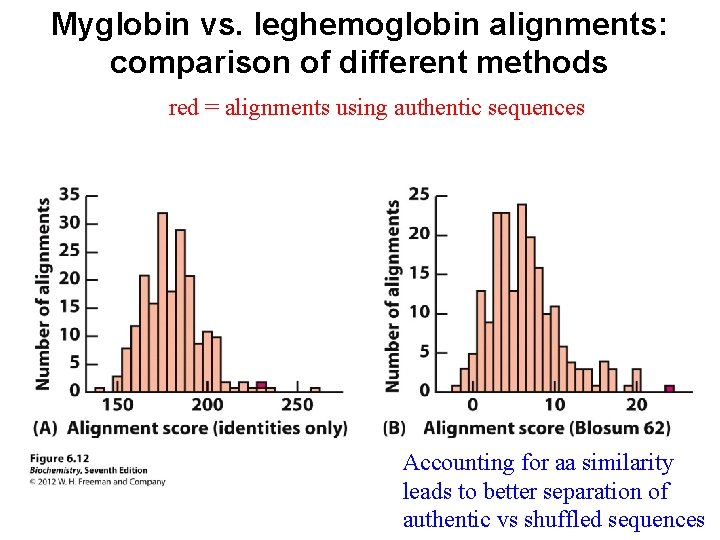

Myglobin vs. leghemoglobin alignments: comparison of different methods red = alignments using authentic sequences Accounting for aa similarity leads to better separation of authentic vs shuffled sequences

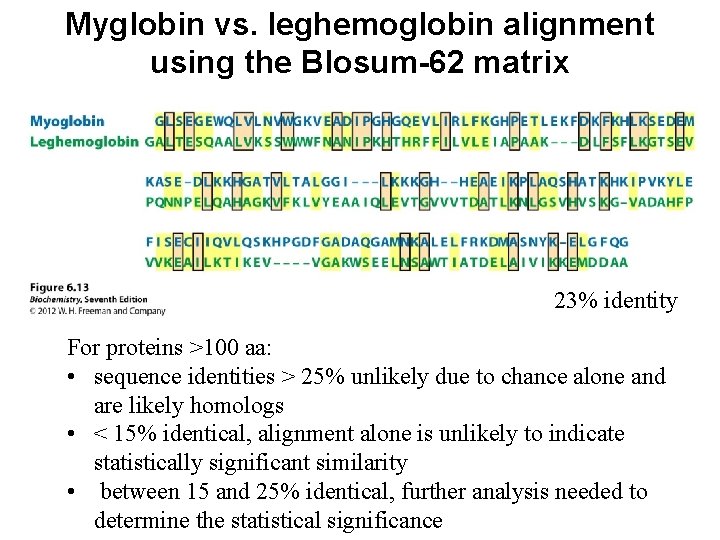

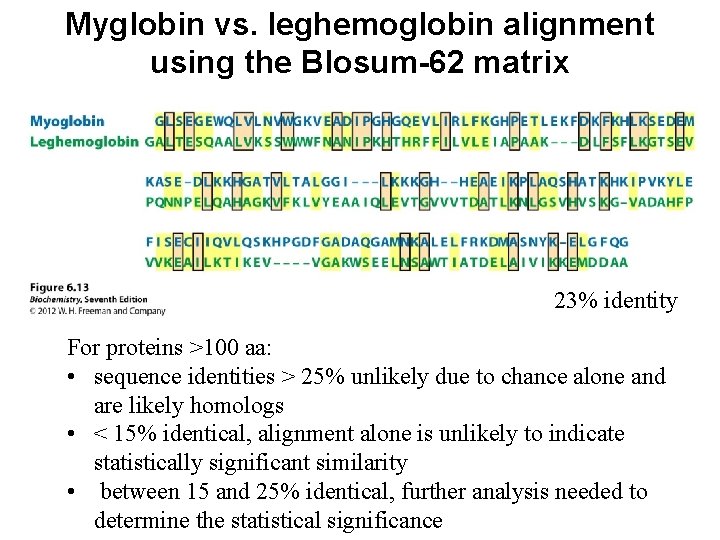

Myglobin vs. leghemoglobin alignment using the Blosum-62 matrix 23% identity For proteins >100 aa: • sequence identities > 25% unlikely due to chance alone and are likely homologs • < 15% identical, alignment alone is unlikely to indicate statistically significant similarity • between 15 and 25% identical, further analysis needed to determine the statistical significance

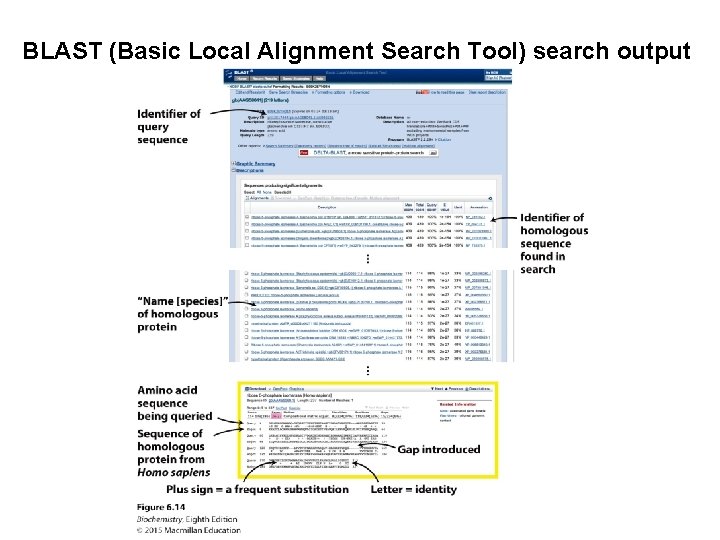

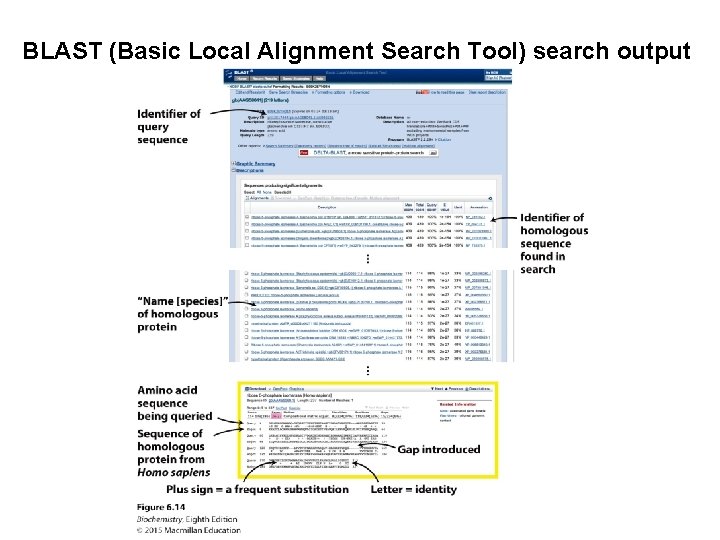

BLAST (Basic Local Alignment Search Tool) search output