PROGRAMMING IN HASKELL Functors Based on Haskell wikibook

PROGRAMMING IN HASKELL Functors Based on Haskell wikibook, the book “Learn You a Haskell for Great Good” (and a few other sources) 0

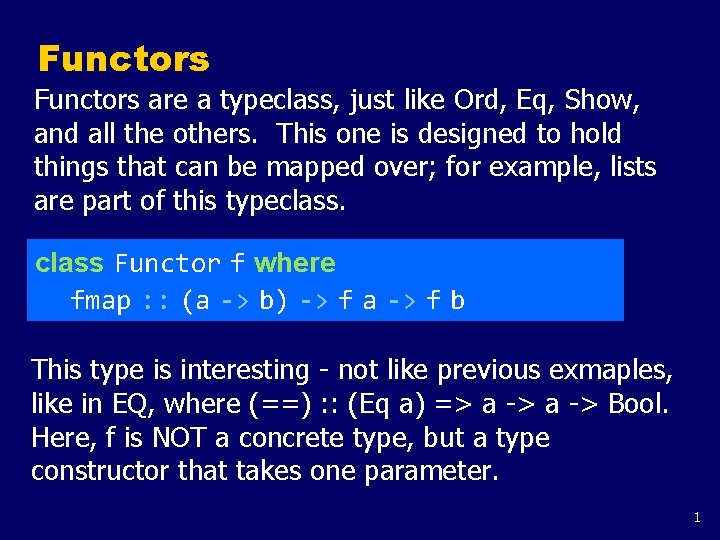

Functors are a typeclass, just like Ord, Eq, Show, and all the others. This one is designed to hold things that can be mapped over; for example, lists are part of this typeclass Functor f where fmap : : (a -> b) -> f a -> f b This type is interesting - not like previous exmaples, like in EQ, where (==) : : (Eq a) => a -> Bool. Here, f is NOT a concrete type, but a type constructor that takes one parameter. 1

Compare fmap to map: fmap : : (a -> b) -> f a -> f b map : : (a -> b) -> [a] -> [b] So map is a lot like a functor! Here, map takes a function and a list of type a, and returns a list of type b. In fact, can define map in terms of fmap: instance Functor [] where fmap = map 2

![Notice what we wrote: instance Functor [] where fmap = map We did NOT Notice what we wrote: instance Functor [] where fmap = map We did NOT](http://slidetodoc.com/presentation_image/ef04ac3d6b1a6c96af18a1445f454749/image-4.jpg)

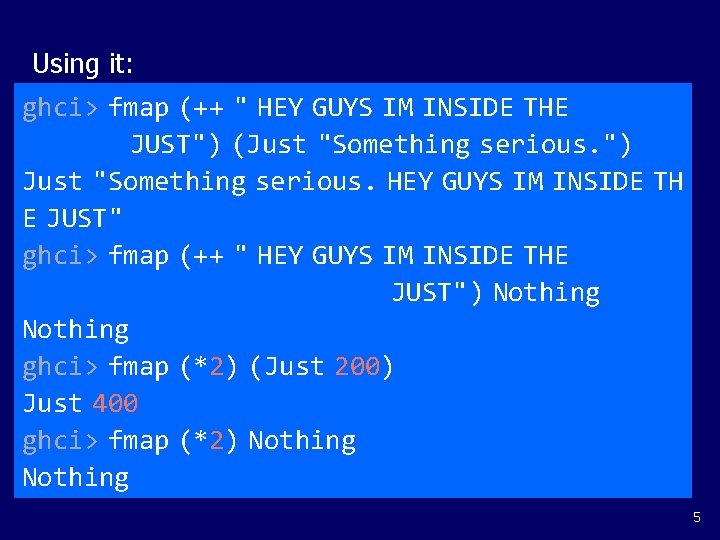

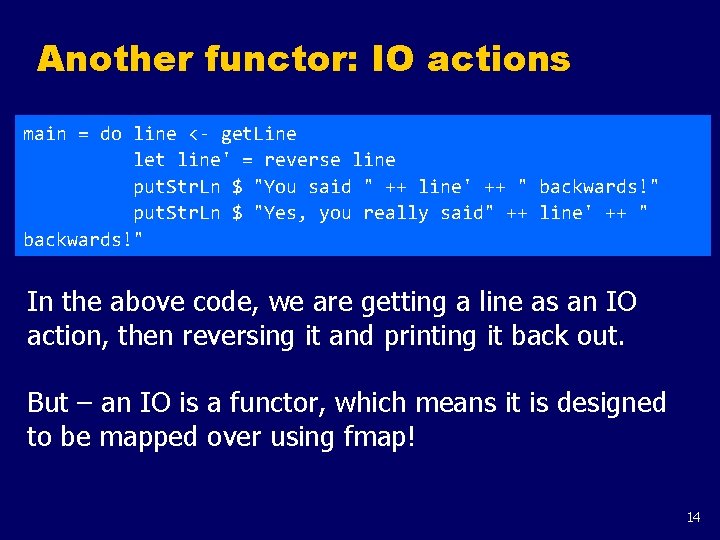

Notice what we wrote: instance Functor [] where fmap = map We did NOT write “instance Functor [a] where…”, since f has to be a type constructor that takes one type. Here, [a] is already a concrete type, while [] is a type constructor that takes one type and can produce many types, like [Int], [String], [[Int]], etc. 3

Another example: instance Functor Maybe where fmap f (Just x) = Just (f x) fmap f Nothing = Nothing Again, we did NOT write “instance Functor (Maybe m) where…”, since functor wants a type constructor. Mentally replace the f’s with Maybe, so fmap acts like (a -> b) -> Maybe a -> Maybe b. If we put (Maybe m), would have (a -> b) -> (Maybe m) a -> (Maybe m) b, which looks wrong. 4

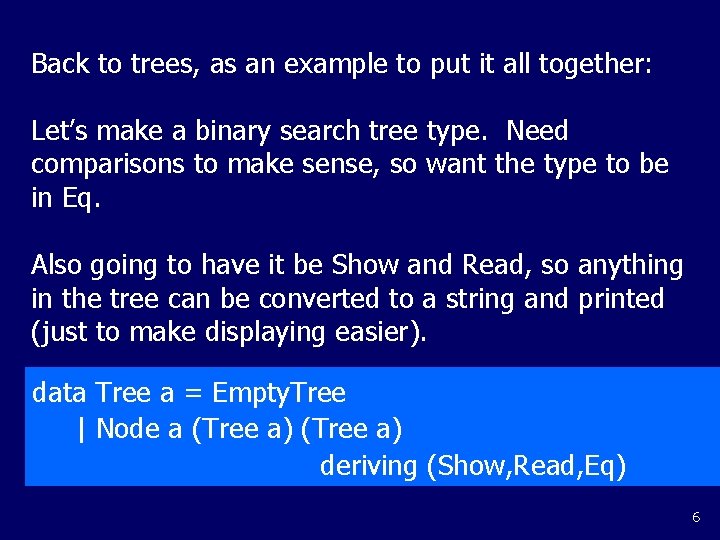

Using it: ghci> fmap (++ " HEY GUYS IM INSIDE THE JUST") (Just "Something serious. ") Just "Something serious. HEY GUYS IM INSIDE TH E JUST" ghci> fmap (++ " HEY GUYS IM INSIDE THE JUST") Nothing ghci> fmap (*2) (Just 200) Just 400 ghci> fmap (*2) Nothing 5

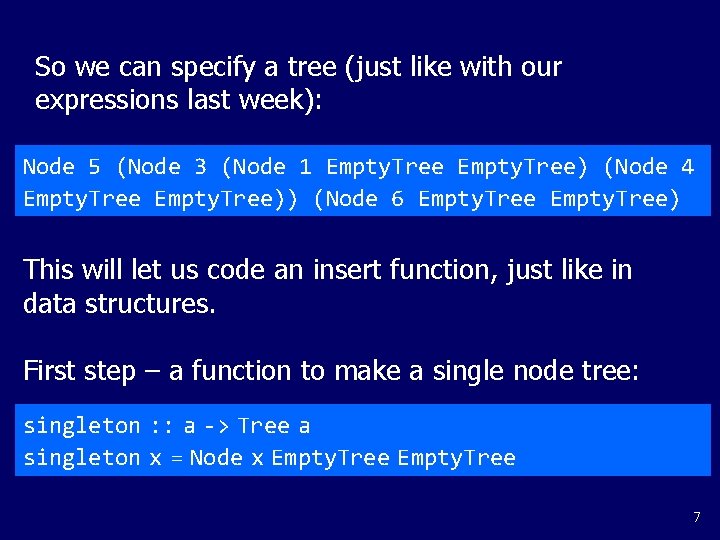

Back to trees, as an example to put it all together: Let’s make a binary search tree type. Need comparisons to make sense, so want the type to be in Eq. Also going to have it be Show and Read, so anything in the tree can be converted to a string and printed (just to make displaying easier). data Tree a = Empty. Tree | Node a (Tree a) deriving (Show, Read, Eq) 6

So we can specify a tree (just like with our expressions last week): Node 5 (Node 3 (Node 1 Empty. Tree) (Node 4 Empty. Tree)) (Node 6 Empty. Tree) This will let us code an insert function, just like in data structures. First step – a function to make a single node tree: singleton : : a -> Tree a singleton x = Node x Empty. Tree 7

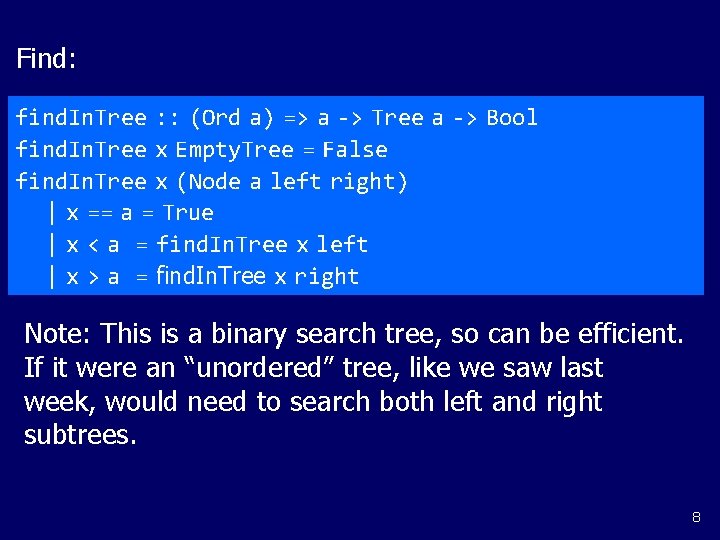

Find: find. In. Tree : : (Ord a) => a -> Tree a -> Bool find. In. Tree x Empty. Tree = False find. In. Tree x (Node a left right) | x == a = True | x < a = find. In. Tree x left | x > a = find. In. Tree x right Note: This is a binary search tree, so can be efficient. If it were an “unordered” tree, like we saw last week, would need to search both left and right subtrees. 8

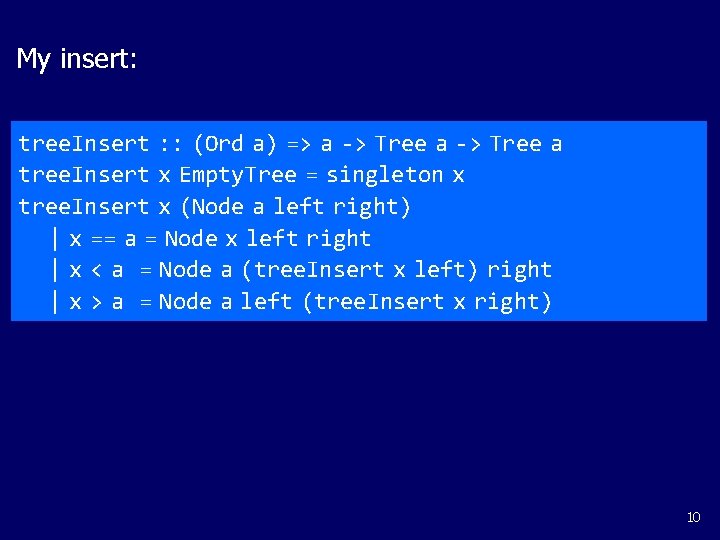

Now – let’s go code insert! tree. Insert : : (Ord a) => a -> Tree a tree. Insert x Empty. Tree = tree. Insert x (Node a left right) = 9

My insert: tree. Insert : : (Ord a) => a -> Tree a tree. Insert x Empty. Tree = singleton x tree. Insert x (Node a left right) | x == a = Node x left right | x < a = Node a (tree. Insert x left) right | x > a = Node a left (tree. Insert x right) 10

![An example run: ghci> let nums = [8, 6, 4, 1, 7, 3, 5] An example run: ghci> let nums = [8, 6, 4, 1, 7, 3, 5]](http://slidetodoc.com/presentation_image/ef04ac3d6b1a6c96af18a1445f454749/image-12.jpg)

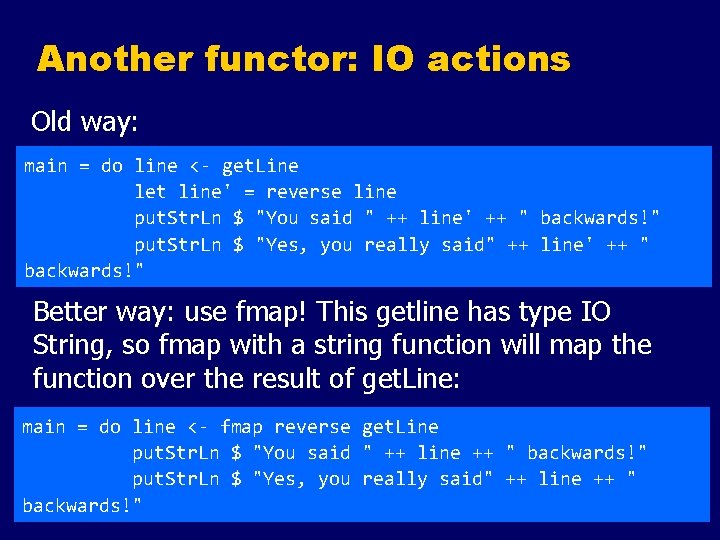

An example run: ghci> let nums = [8, 6, 4, 1, 7, 3, 5] ghci> let nums. Tree = foldr tree. Insert Empty. Tre e nums ghci> nums. Tree Node 5 (Node 3 (Node 1 Empty. Tree) (N ode 4 Empty. Tree)) (Node 7 (Node 6 Em pty. Tree Empty. Tree) (Node 8 Empty. Tree Empty. Tre e)) 11

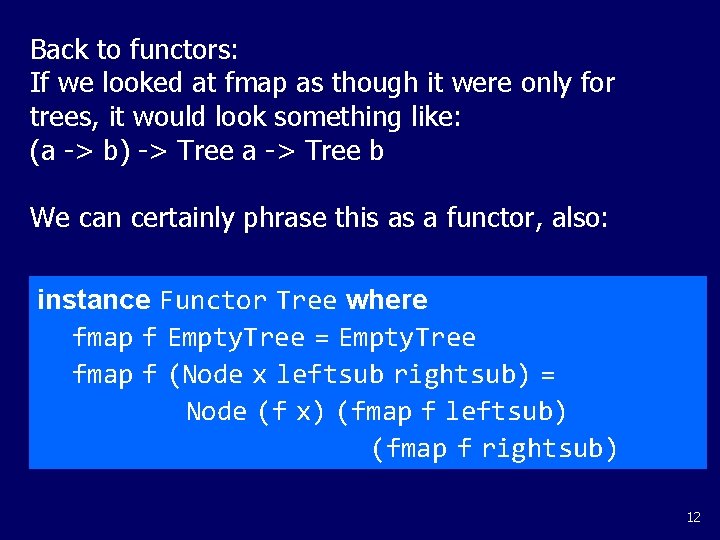

Back to functors: If we looked at fmap as though it were only for trees, it would look something like: (a -> b) -> Tree a -> Tree b We can certainly phrase this as a functor, also: instance Functor Tree where fmap f Empty. Tree = Empty. Tree fmap f (Node x leftsub rightsub) = Node (f x) (fmap f leftsub) (fmap f rightsub) 12

Using the tree functor: ghci> fmap (*2) Empty. Tree ghci> fmap (*4) (foldr tree. Insert Empty. Tree [5, 7, 3, 2, 1, 7]) Node 28 (Node 4 Empty. Tree (Node 8 Empty. Tree (N ode 12 Empty. Tree (Node 20 Empty. Tree )))) Empty. Tree 13

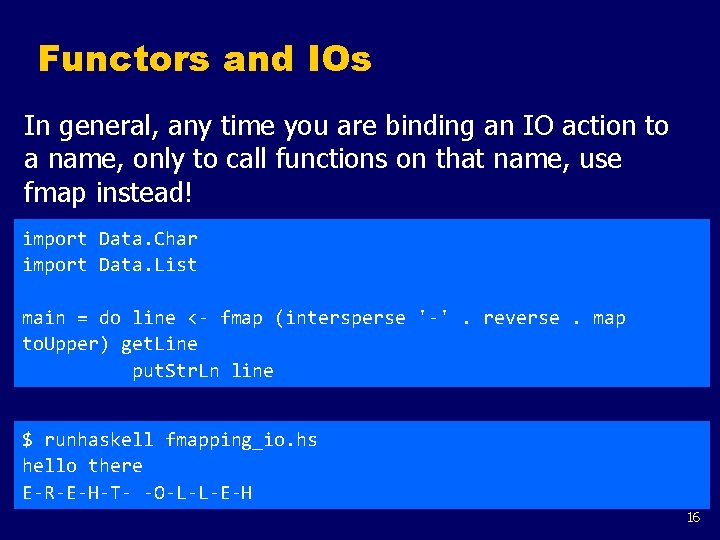

Another functor: IO actions main = do line <- get. Line let line' = reverse line put. Str. Ln $ "You said " ++ line' ++ " backwards!" put. Str. Ln $ "Yes, you really said" ++ line' ++ " backwards!" In the above code, we are getting a line as an IO action, then reversing it and printing it back out. But – an IO is a functor, which means it is designed to be mapped over using fmap! 14

Another functor: IO actions Old way: main = do line <- get. Line let line' = reverse line put. Str. Ln $ "You said " ++ line' ++ " backwards!" put. Str. Ln $ "Yes, you really said" ++ line' ++ " backwards!" Better way: use fmap! This getline has type IO String, so fmap with a string function will map the function over the result of get. Line: main = do line <- fmap reverse get. Line put. Str. Ln $ "You said " ++ line ++ " backwards!" put. Str. Ln $ "Yes, you really said" ++ line ++ " backwards!" 15

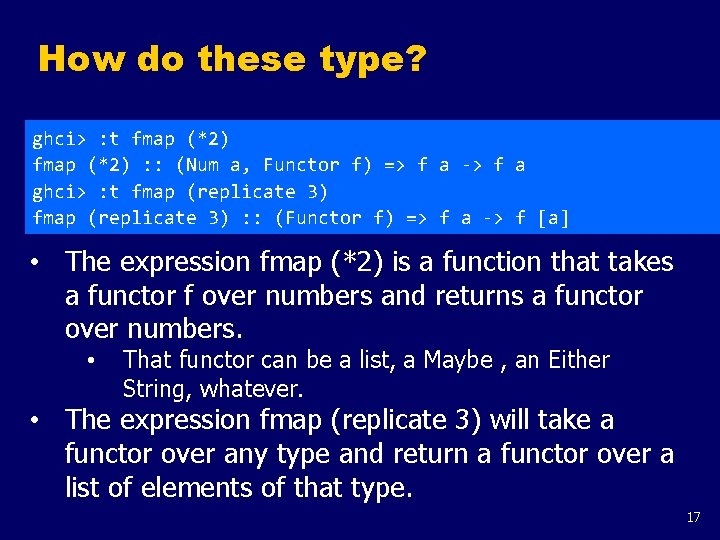

Functors and IOs In general, any time you are binding an IO action to a name, only to call functions on that name, use fmap instead! import Data. Char import Data. List main = do line <- fmap (intersperse '-'. reverse. map to. Upper) get. Line put. Str. Ln line $ runhaskell fmapping_io. hs hello there E-R-E-H-T- -O-L-L-E-H 16

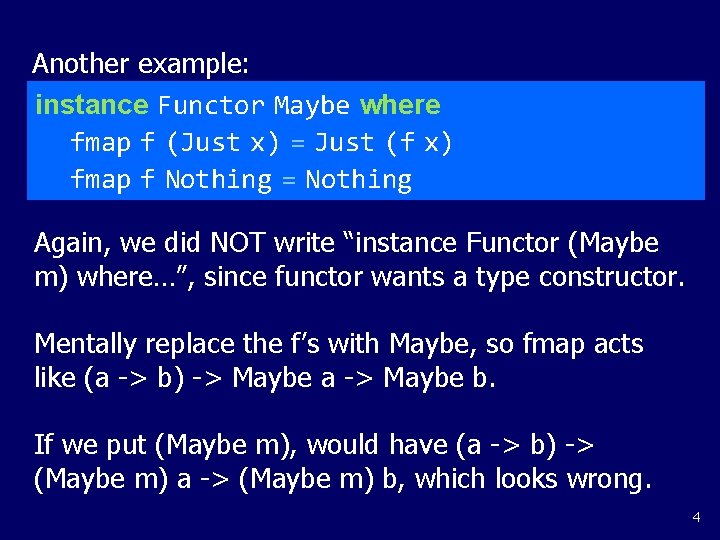

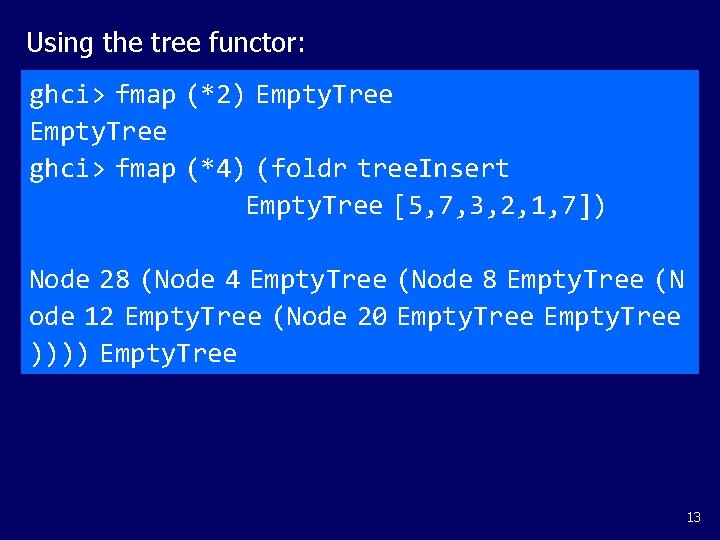

How do these type? ghci> : t fmap (*2) : : (Num a, Functor f) => f a -> f a ghci> : t fmap (replicate 3) : : (Functor f) => f a -> f [a] • The expression fmap (*2) is a function that takes a functor f over numbers and returns a functor over numbers. • That functor can be a list, a Maybe , an Either String, whatever. • The expression fmap (replicate 3) will take a functor over any type and return a functor over a list of elements of that type. 17

![What will one of these do? ghci> fmap (replicate 3) [1, 2, 3, 4] What will one of these do? ghci> fmap (replicate 3) [1, 2, 3, 4]](http://slidetodoc.com/presentation_image/ef04ac3d6b1a6c96af18a1445f454749/image-19.jpg)

What will one of these do? ghci> fmap (replicate 3) [1, 2, 3, 4] [[1, 1, 1], [2, 2, 2], [3, 3, 3], [4, 4, 4]] ghci> fmap (replicate 3) (Just 4) Just [4, 4, 4] ghci> fmap (replicate 3) Nothing • The type fmap (replicate 3) : : (Functor f) => f a -> f [a] means that the function will work on any functor. What exactly it will do depends on which functor we use it on. • • If we use fmap (replicate 3) on a list, the list's implementation for fmap will be chosen, which is just map. If we use it on a Maybe a, it'll apply replicate 3 to the value inside the Just, or if it's Nothing, then it stays Nothing. 18

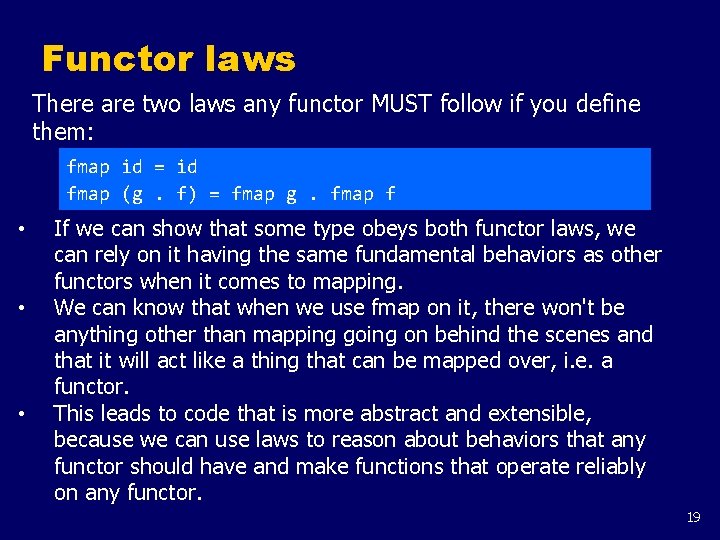

Functor laws There are two laws any functor MUST follow if you define them: fmap id = id fmap (g. f) = fmap g. fmap f • • • If we can show that some type obeys both functor laws, we can rely on it having the same fundamental behaviors as other functors when it comes to mapping. We can know that when we use fmap on it, there won't be anything other than mapping going on behind the scenes and that it will act like a thing that can be mapped over, i. e. a functor. This leads to code that is more abstract and extensible, because we can use laws to reason about behaviors that any functor should have and make functions that operate reliably on any functor. 19

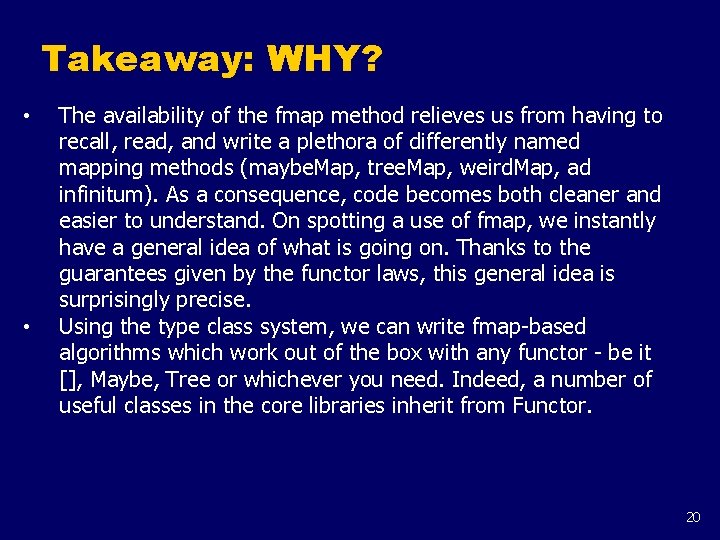

Takeaway: WHY? • • The availability of the fmap method relieves us from having to recall, read, and write a plethora of differently named mapping methods (maybe. Map, tree. Map, weird. Map, ad infinitum). As a consequence, code becomes both cleaner and easier to understand. On spotting a use of fmap, we instantly have a general idea of what is going on. Thanks to the guarantees given by the functor laws, this general idea is surprisingly precise. Using the type class system, we can write fmap-based algorithms which work out of the box with any functor - be it [], Maybe, Tree or whichever you need. Indeed, a number of useful classes in the core libraries inherit from Functor. 20

- Slides: 21