Programming in C Arrays Structs and Strings 72809

![Array Argument Example void add. Two( int a[], int size ) { int k; Array Argument Example void add. Two( int a[], int size ) { int k;](https://slidetodoc.com/presentation_image/2fc0ead94df9dbbd0e56e44f6ab3b5bd/image-7.jpg)

![String Code char first[10] = “bobby”; last[15] = “smith”; name[30]; you[5] = “bobo”; strcpy( String Code char first[10] = “bobby”; last[15] = “smith”; name[30]; you[5] = “bobo”; strcpy(](https://slidetodoc.com/presentation_image/2fc0ead94df9dbbd0e56e44f6ab3b5bd/image-11.jpg)

![union. c union data { int x; char c[8]; } ; int i; union union. c union data { int x; char c[8]; } ; int i; union](https://slidetodoc.com/presentation_image/2fc0ead94df9dbbd0e56e44f6ab3b5bd/image-25.jpg)

- Slides: 30

Programming in C Arrays, Structs and Strings 7/28/09

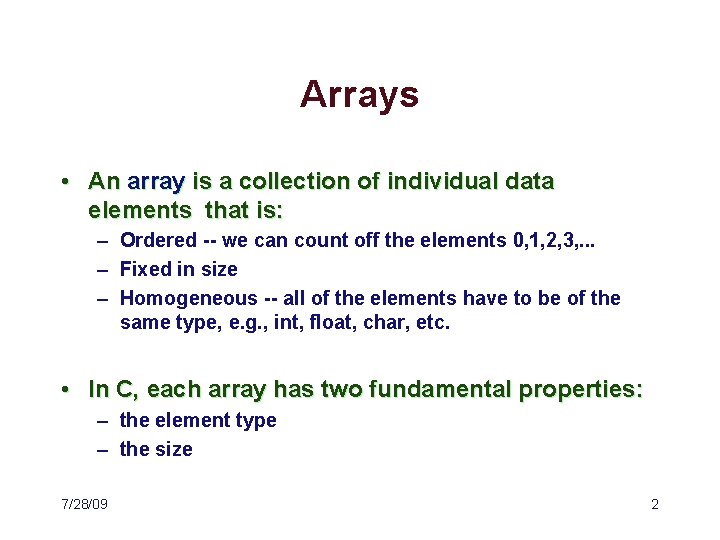

Arrays • An array is a collection of individual data elements that is: – Ordered -- we can count off the elements 0, 1, 2, 3, . . . – Fixed in size – Homogeneous -- all of the elements have to be of the same type, e. g. , int, float, char, etc. • In C, each array has two fundamental properties: – the element type – the size 7/28/09 2

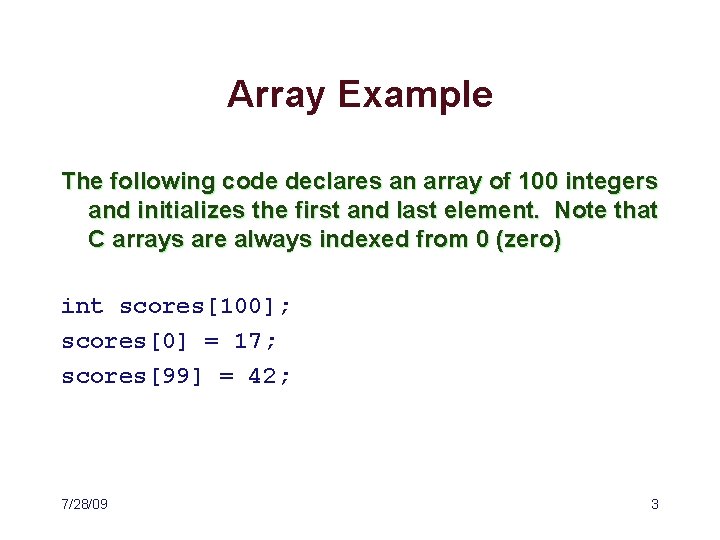

Array Example The following code declares an array of 100 integers and initializes the first and last element. Note that C arrays are always indexed from 0 (zero) int scores[100]; scores[0] = 17; scores[99] = 42; 7/28/09 3

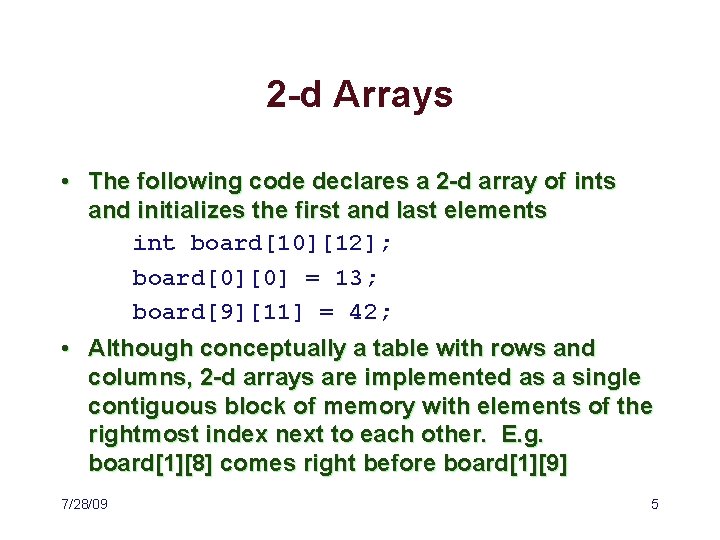

Arrays in Memory • The name of the array refers to the whole array by acting like a pointer (the memory address) of the start of the array scores . . . 0 1 98 99 Someone else’s memory 7/28/09 Don’t read/write here 4

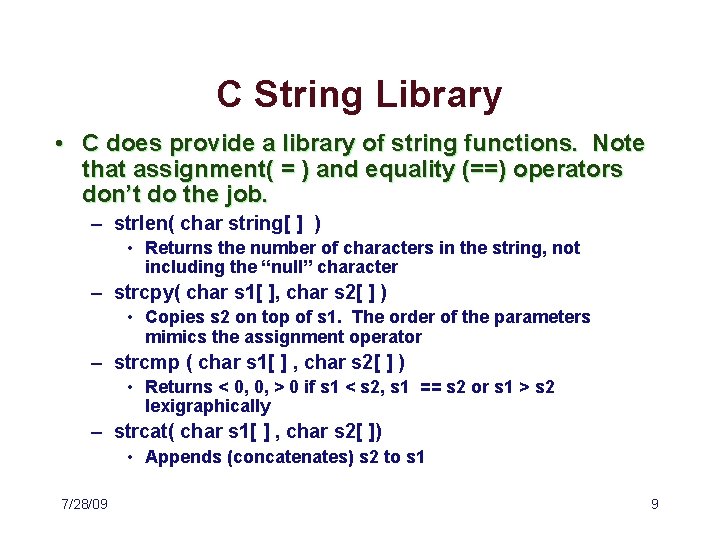

2 -d Arrays • The following code declares a 2 -d array of ints and initializes the first and last elements int board[10][12]; board[0][0] = 13; board[9][11] = 42; • Although conceptually a table with rows and columns, 2 -d arrays are implemented as a single contiguous block of memory with elements of the rightmost index next to each other. E. g. board[1][8] comes right before board[1][9] 7/28/09 5

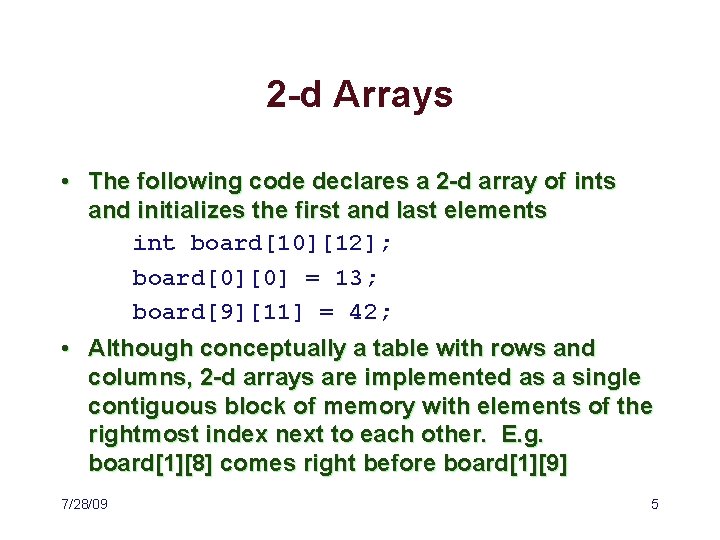

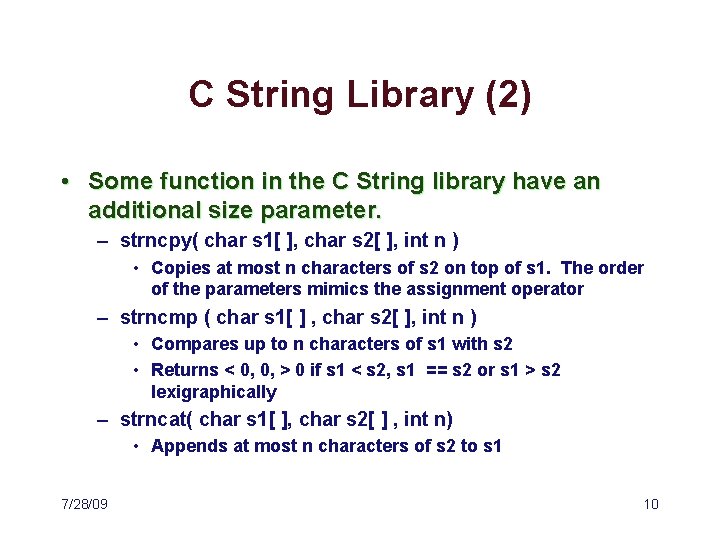

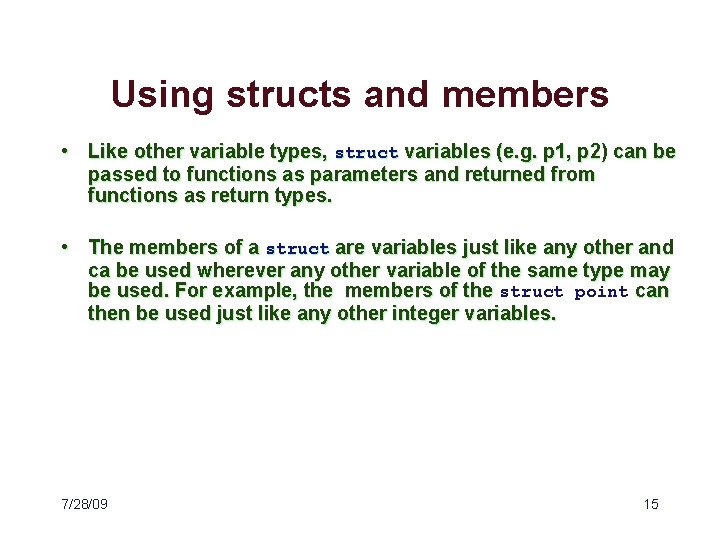

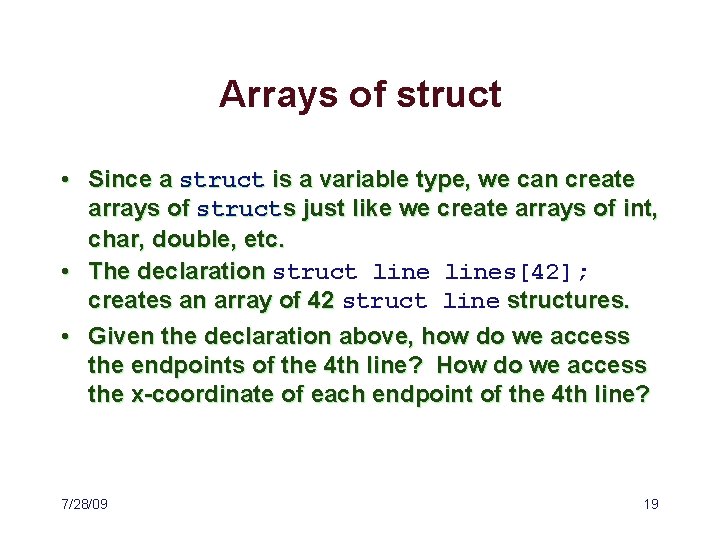

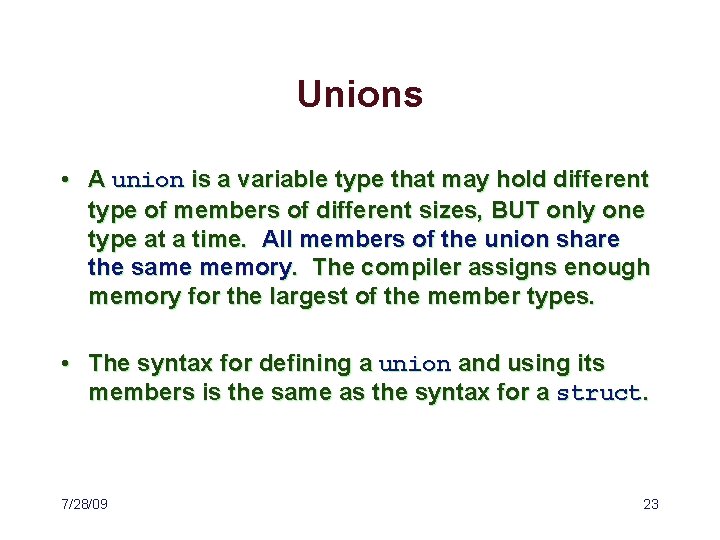

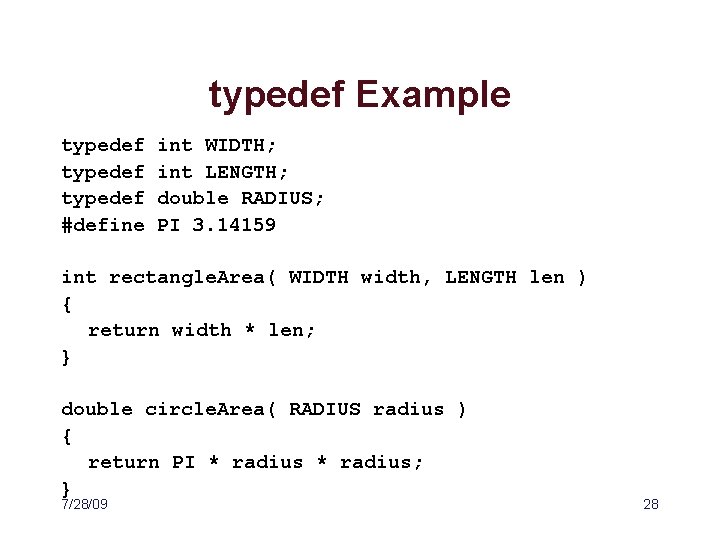

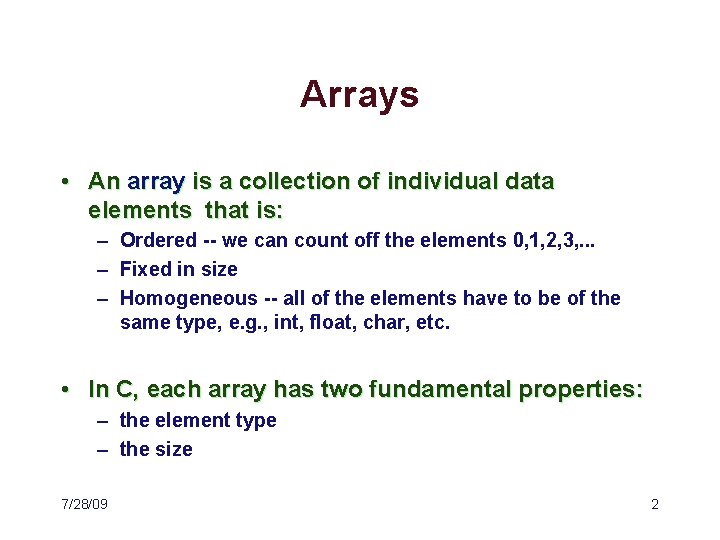

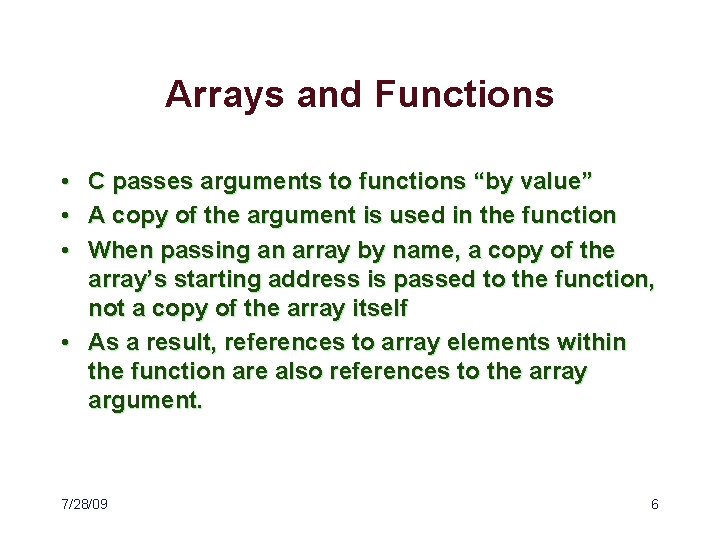

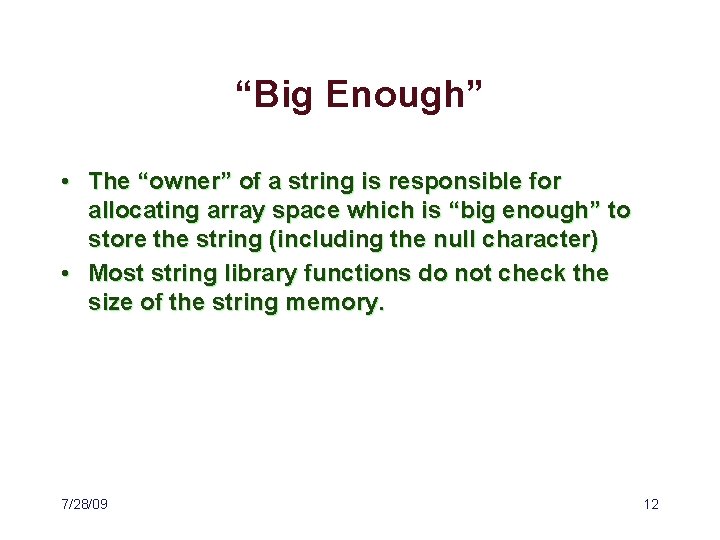

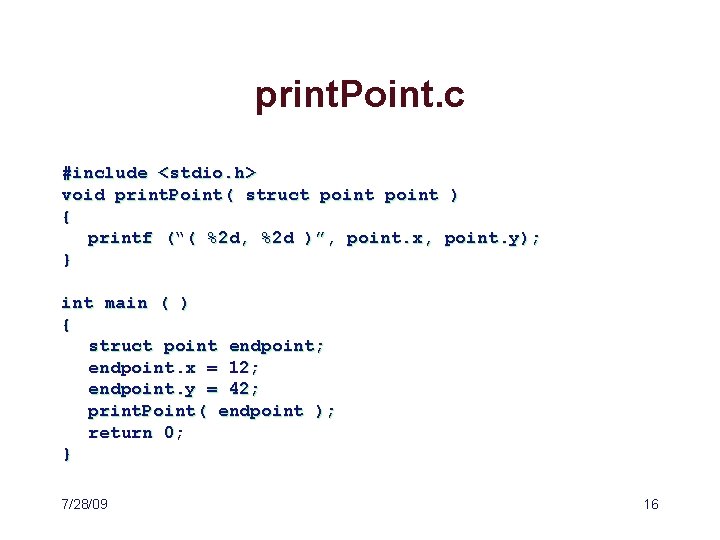

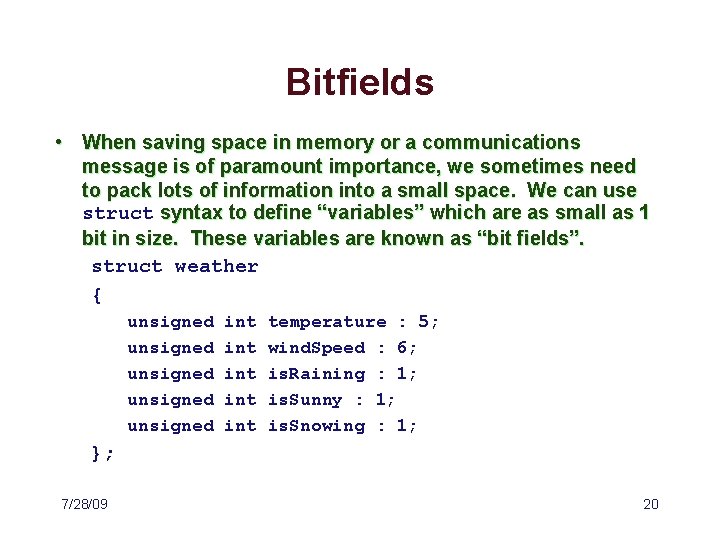

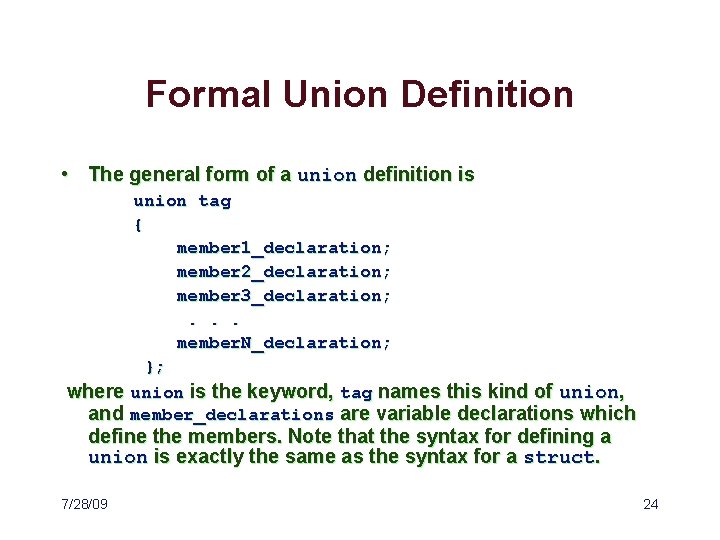

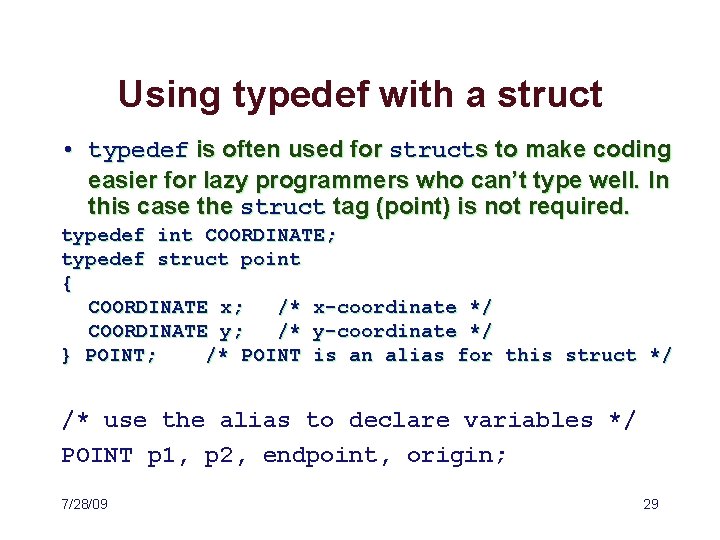

Arrays and Functions • • • C passes arguments to functions “by value” A copy of the argument is used in the function When passing an array by name, a copy of the array’s starting address is passed to the function, not a copy of the array itself • As a result, references to array elements within the function are also references to the array argument. 7/28/09 6

![Array Argument Example void add Two int a int size int k Array Argument Example void add. Two( int a[], int size ) { int k;](https://slidetodoc.com/presentation_image/2fc0ead94df9dbbd0e56e44f6ab3b5bd/image-7.jpg)

Array Argument Example void add. Two( int a[], int size ) { int k; for (k = 0; k < size; k++) a[k] += 2; } int main( ) { int j, scores[3]; scores[0] = 42; scores[1] = 33; scores[2] = 99; add. Two( scores, 3); for (j = 0; j < 3; j++) printf(“%d “, scores[j]); /* 44, 35, 101 */ return 0; } 7/28/09 7

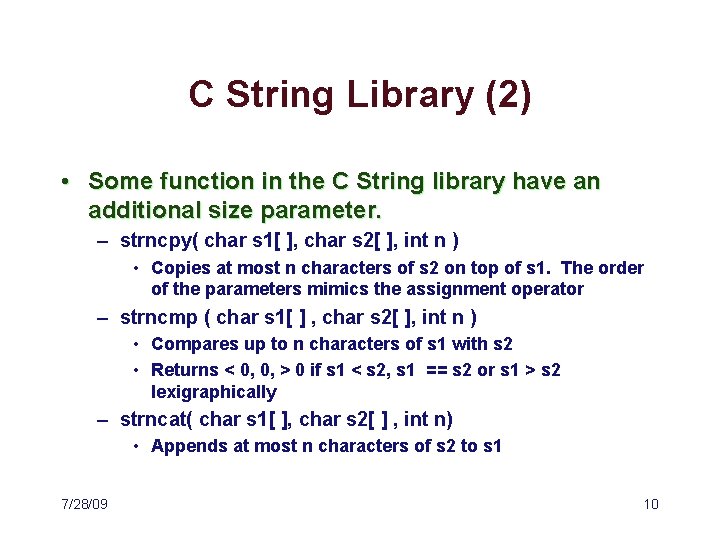

Strings in C • In C, a string is an array of characters terminated with the “null” character (‘�’, value = 0). char name[4] = “bob”; char title[10] = “Mr. ”; name ‘b’ ‘M’ ‘r’ ‘o’ ‘b’ � ‘. ’ � x x x title 7/28/09 8

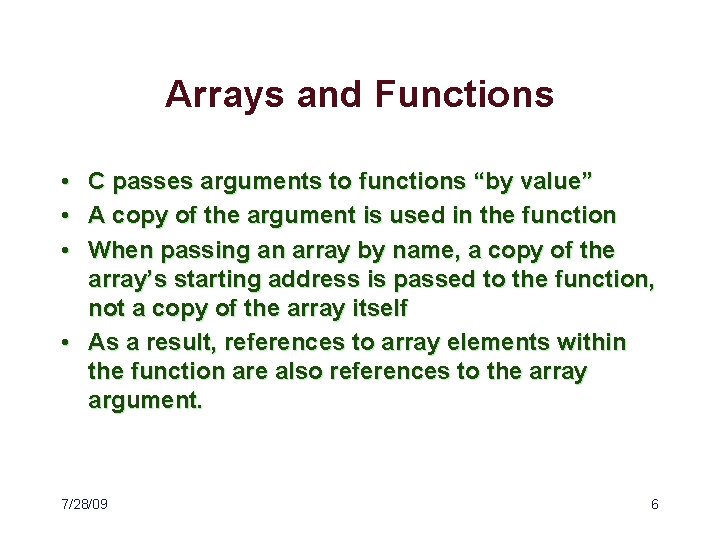

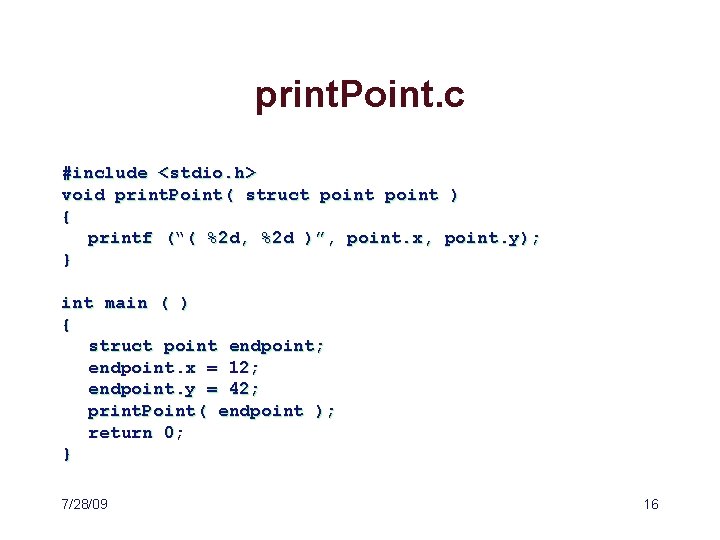

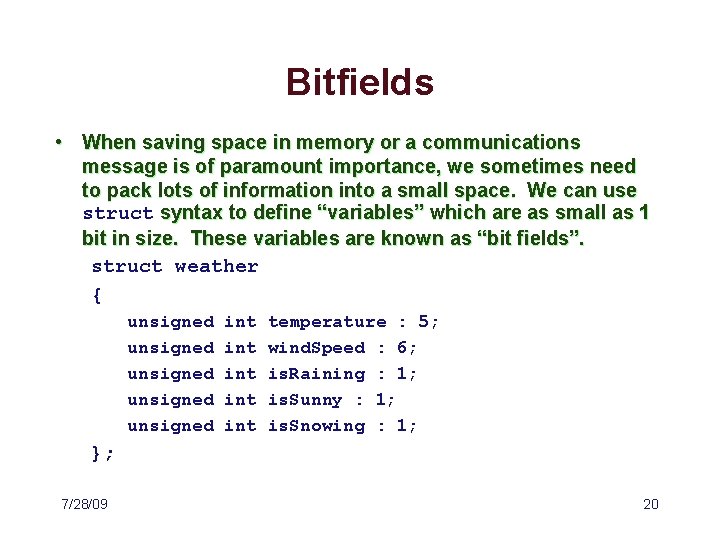

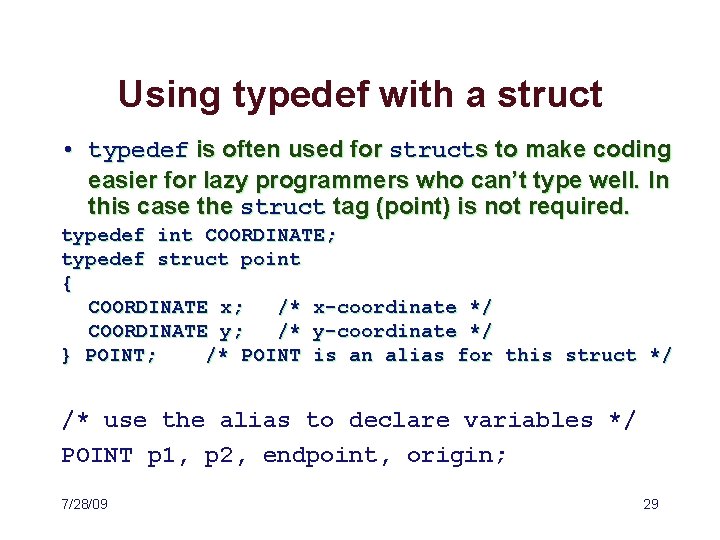

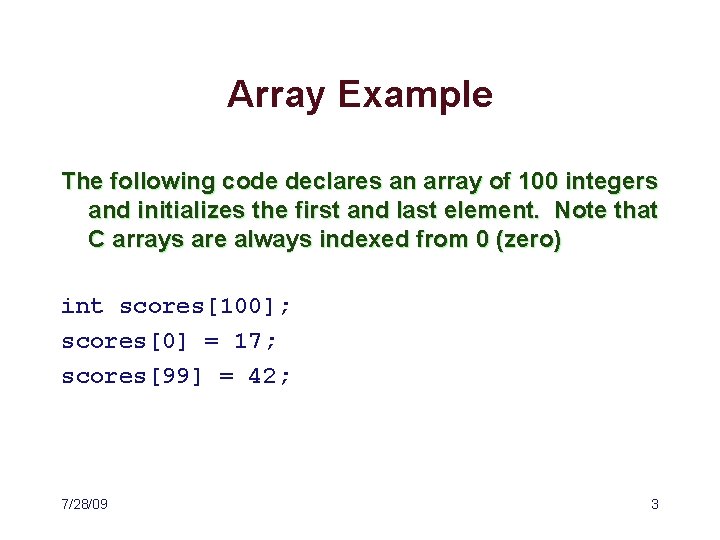

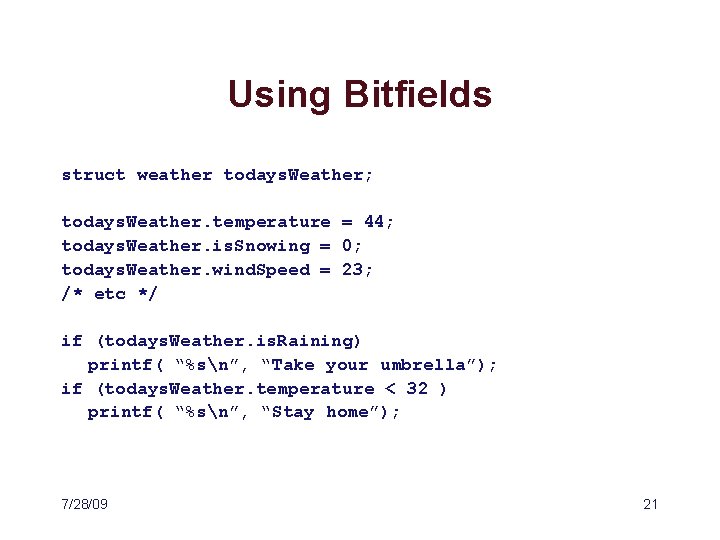

C String Library • C does provide a library of string functions. Note that assignment( = ) and equality (==) operators don’t do the job. – strlen( char string[ ] ) • Returns the number of characters in the string, not including the “null” character – strcpy( char s 1[ ], char s 2[ ] ) • Copies s 2 on top of s 1. The order of the parameters mimics the assignment operator – strcmp ( char s 1[ ] , char s 2[ ] ) • Returns < 0, 0, > 0 if s 1 < s 2, s 1 == s 2 or s 1 > s 2 lexigraphically – strcat( char s 1[ ] , char s 2[ ]) • Appends (concatenates) s 2 to s 1 7/28/09 9

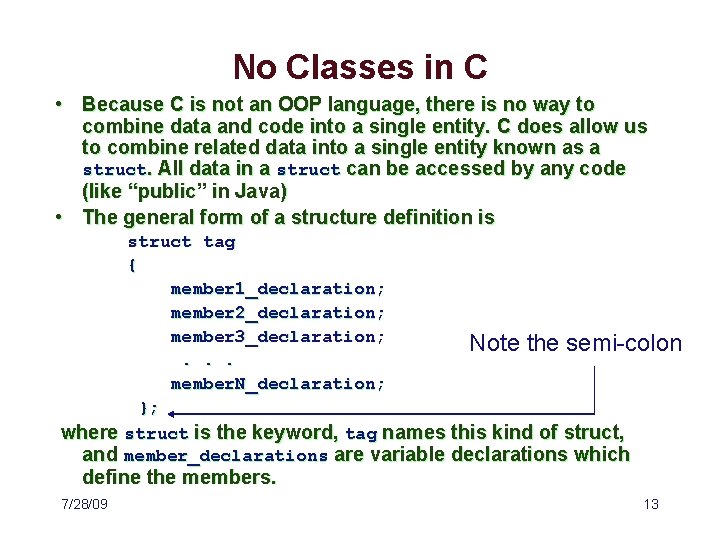

C String Library (2) • Some function in the C String library have an additional size parameter. – strncpy( char s 1[ ], char s 2[ ], int n ) • Copies at most n characters of s 2 on top of s 1. The order of the parameters mimics the assignment operator – strncmp ( char s 1[ ] , char s 2[ ], int n ) • Compares up to n characters of s 1 with s 2 • Returns < 0, 0, > 0 if s 1 < s 2, s 1 == s 2 or s 1 > s 2 lexigraphically – strncat( char s 1[ ], char s 2[ ] , int n) • Appends at most n characters of s 2 to s 1 7/28/09 10

![String Code char first10 bobby last15 smith name30 you5 bobo strcpy String Code char first[10] = “bobby”; last[15] = “smith”; name[30]; you[5] = “bobo”; strcpy(](https://slidetodoc.com/presentation_image/2fc0ead94df9dbbd0e56e44f6ab3b5bd/image-11.jpg)

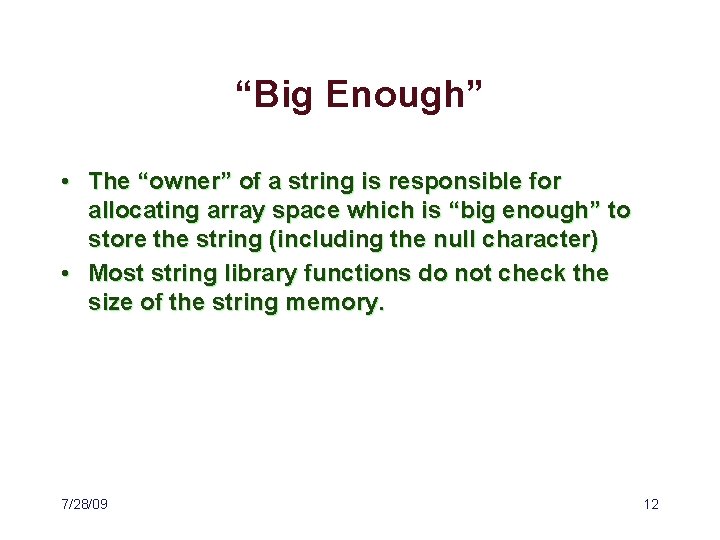

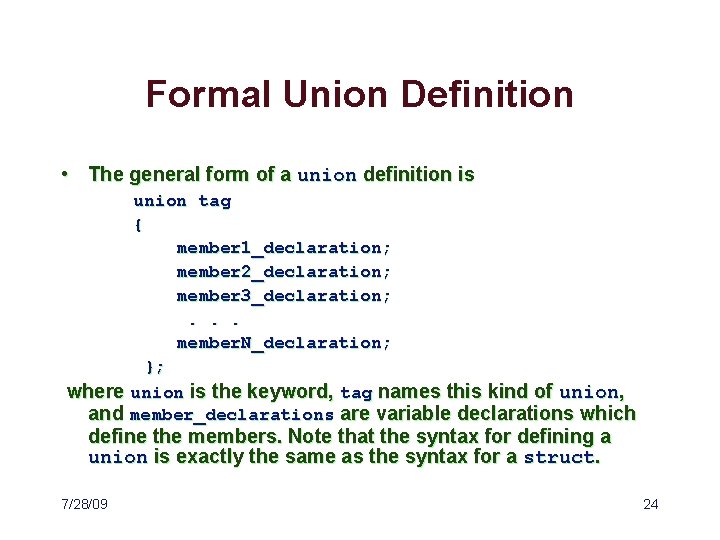

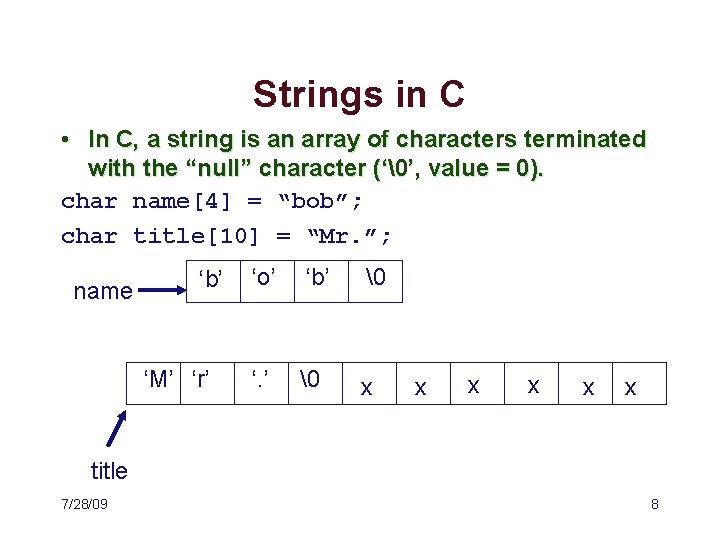

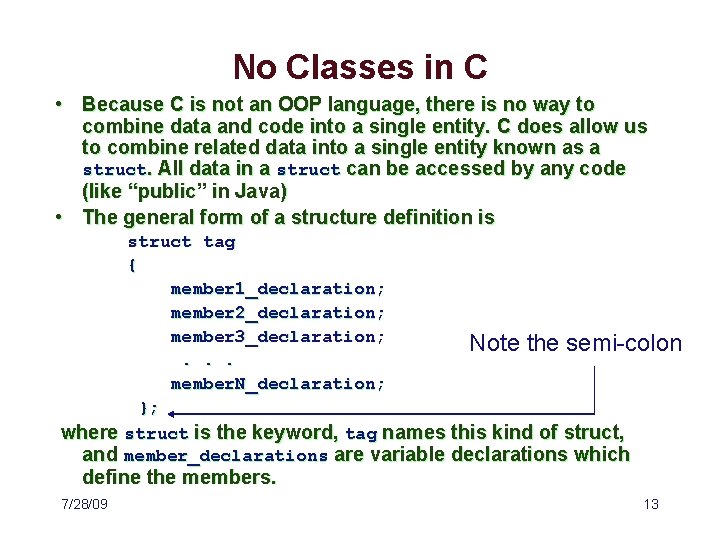

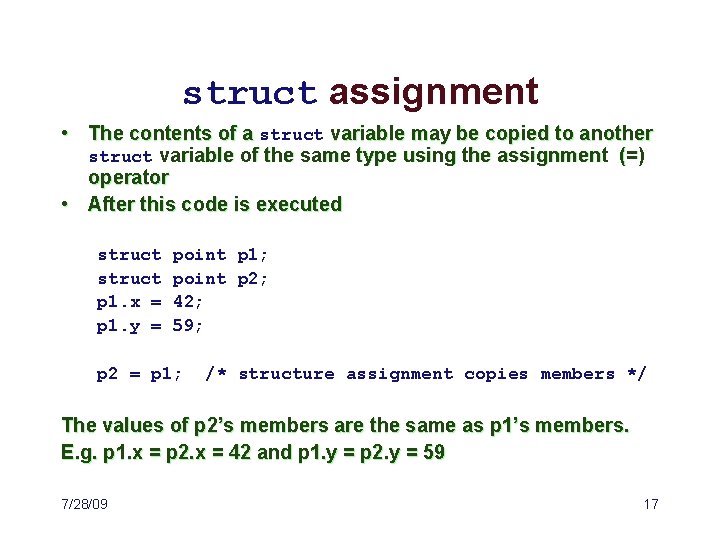

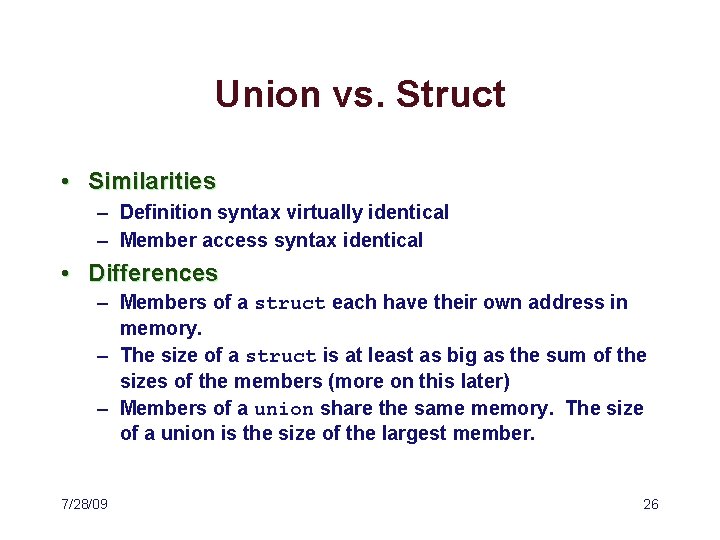

String Code char first[10] = “bobby”; last[15] = “smith”; name[30]; you[5] = “bobo”; strcpy( name, first ); strcat( name, last ); printf( “%d, %sn”, strlen(name) name ); strncpy( name, last, 2 ); printf( “%d, %sn”, strlen(name) name ); int result = strcmp( you, first ); result = strncmp( you, first, 3 ); strcat( first, last ); 7/28/09 11

“Big Enough” • The “owner” of a string is responsible for allocating array space which is “big enough” to store the string (including the null character) • Most string library functions do not check the size of the string memory. 7/28/09 12

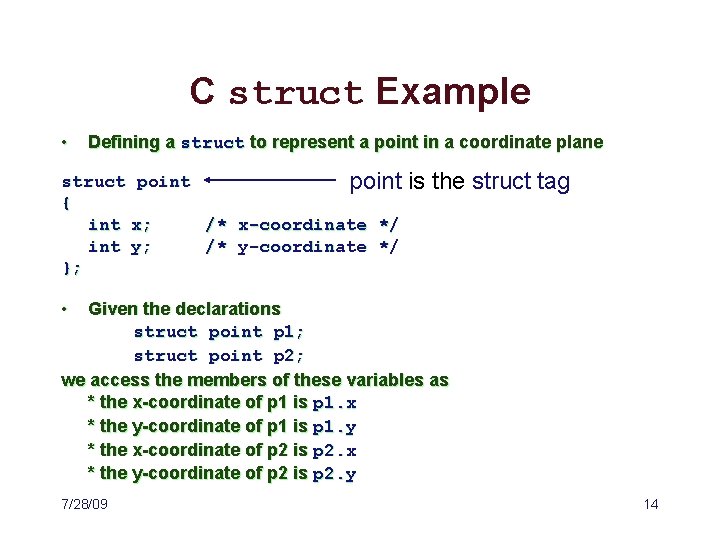

No Classes in C • Because C is not an OOP language, there is no way to combine data and code into a single entity. C does allow us to combine related data into a single entity known as a struct. All data in a struct can be accessed by any code (like “public” in Java) • The general form of a structure definition is struct tag { member 1_declaration; member 2_declaration; member 3_declaration; Note the semi-colon. . . member. N_declaration; }; where struct is the keyword, tag names this kind of struct, and member_declarations are variable declarations which define the members. 7/28/09 13

C struct Example • Defining a struct to represent a point in a coordinate plane struct point { int x; /* x-coordinate */ int y; /* y-coordinate */ }; is the struct tag • Given the declarations struct point p 1; struct point p 2; we access the members of these variables as * the x-coordinate of p 1 is p 1. x * the y-coordinate of p 1 is p 1. y * the x-coordinate of p 2 is p 2. x * the y-coordinate of p 2 is p 2. y 7/28/09 14

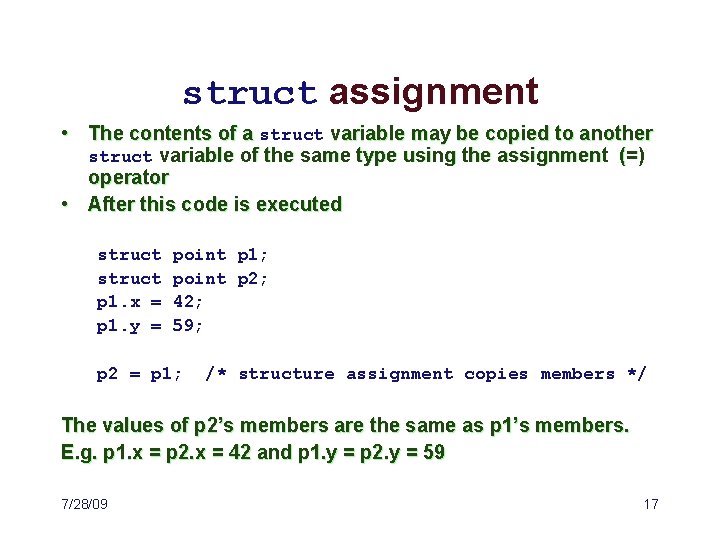

Using structs and members • Like other variable types, struct variables (e. g. p 1, p 2) can be passed to functions as parameters and returned from functions as return types. • The members of a struct are variables just like any other and ca be used wherever any other variable of the same type may be used. For example, the members of the struct point can then be used just like any other integer variables. 7/28/09 15

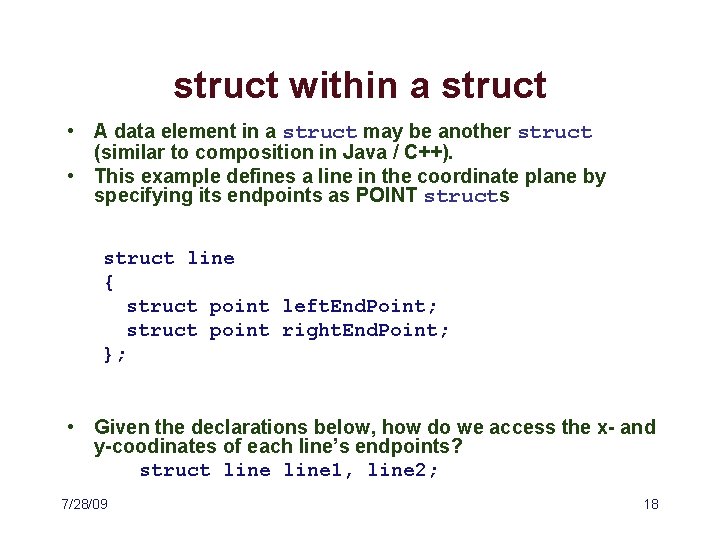

print. Point. c #include <stdio. h> void print. Point( struct point ) { printf (“( %2 d, %2 d )”, point. x, point. y); } int main ( ) { struct point endpoint; endpoint. x = 12; endpoint. y = 42; print. Point( endpoint ); return 0; } 7/28/09 16

struct assignment • The contents of a struct variable may be copied to another struct variable of the same type using the assignment (=) operator • After this code is executed struct p 1. x = p 1. y = point p 1; point p 2; 42; 59; p 2 = p 1; /* structure assignment copies members */ The values of p 2’s members are the same as p 1’s members. E. g. p 1. x = p 2. x = 42 and p 1. y = p 2. y = 59 7/28/09 17

struct within a struct • A data element in a struct may be another struct (similar to composition in Java / C++). • This example defines a line in the coordinate plane by specifying its endpoints as POINT structs struct line { struct point left. End. Point; struct point right. End. Point; }; • Given the declarations below, how do we access the x- and y-coodinates of each line’s endpoints? struct line 1, line 2; 7/28/09 18

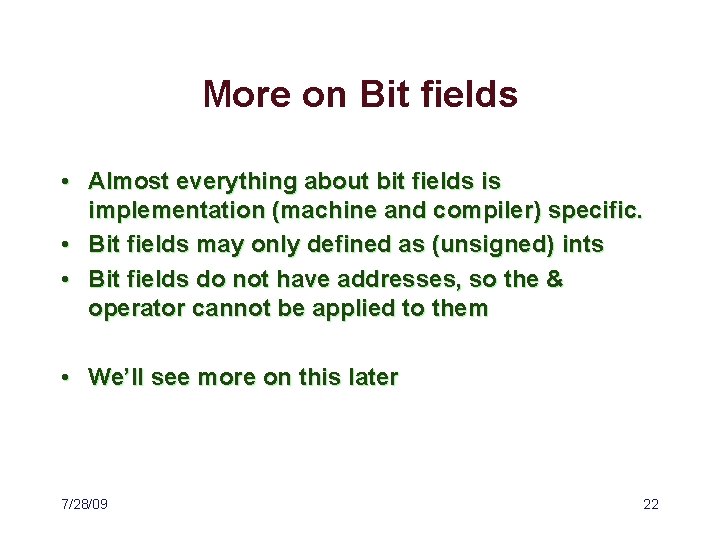

Arrays of struct • Since a struct is a variable type, we can create arrays of structs just like we create arrays of int, char, double, etc. • The declaration struct lines[42]; creates an array of 42 struct line structures. • Given the declaration above, how do we access the endpoints of the 4 th line? How do we access the x-coordinate of each endpoint of the 4 th line? 7/28/09 19

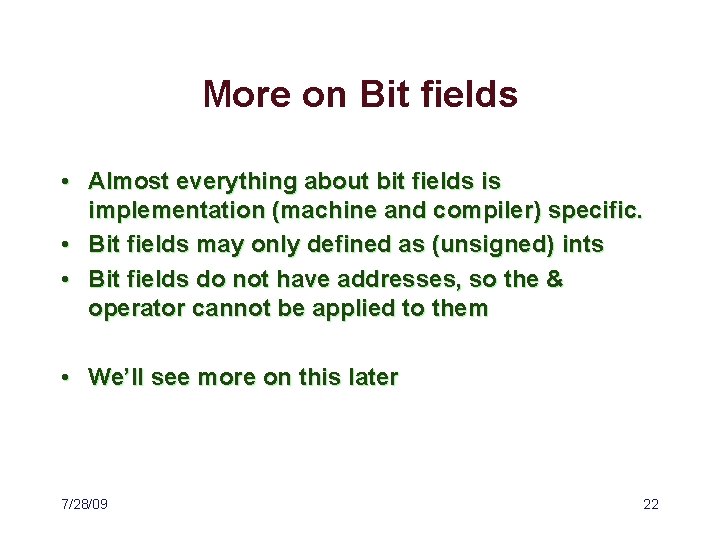

Bitfields • When saving space in memory or a communications message is of paramount importance, we sometimes need to pack lots of information into a small space. We can use struct syntax to define “variables” which are as small as 1 bit in size. These variables are known as “bit fields”. struct weather { unsigned unsigned int int int temperature : 5; wind. Speed : 6; is. Raining : 1; is. Sunny : 1; is. Snowing : 1; }; 7/28/09 20

Using Bitfields struct weather todays. Weather; todays. Weather. temperature = 44; todays. Weather. is. Snowing = 0; todays. Weather. wind. Speed = 23; /* etc */ if (todays. Weather. is. Raining) printf( “%sn”, “Take your umbrella”); if (todays. Weather. temperature < 32 ) printf( “%sn”, “Stay home”); 7/28/09 21

More on Bit fields • Almost everything about bit fields is implementation (machine and compiler) specific. • Bit fields may only defined as (unsigned) ints • Bit fields do not have addresses, so the & operator cannot be applied to them • We’ll see more on this later 7/28/09 22

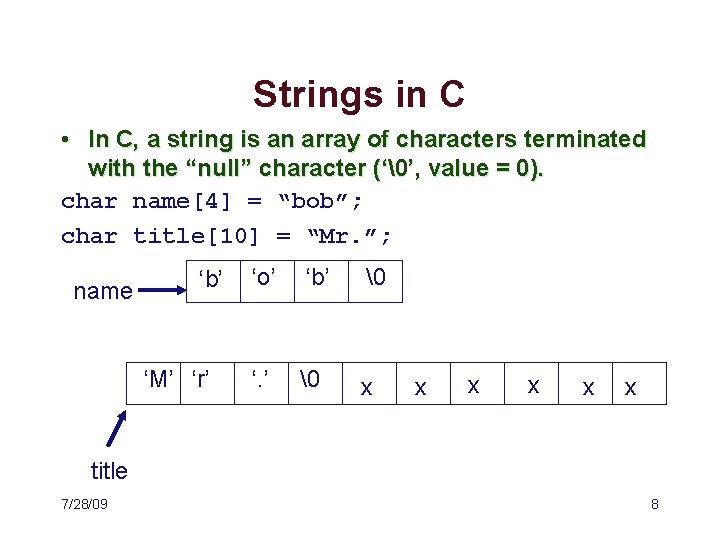

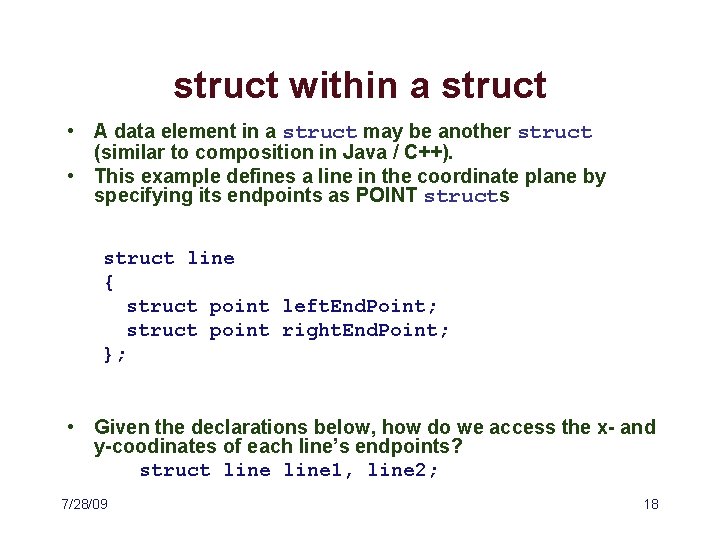

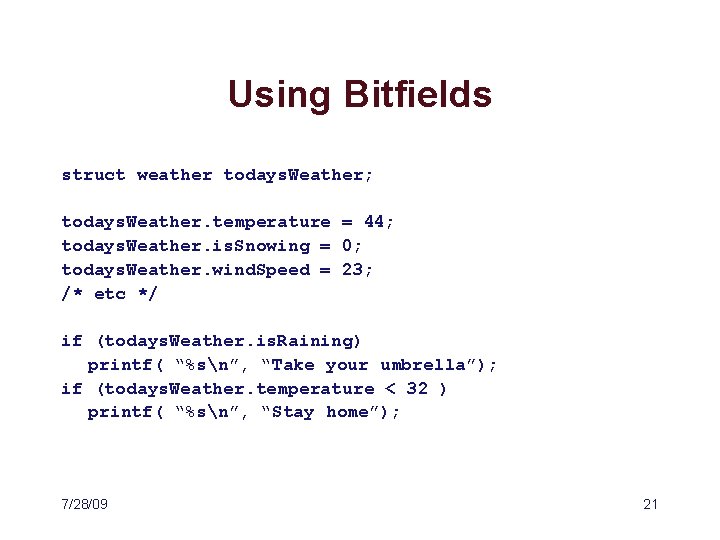

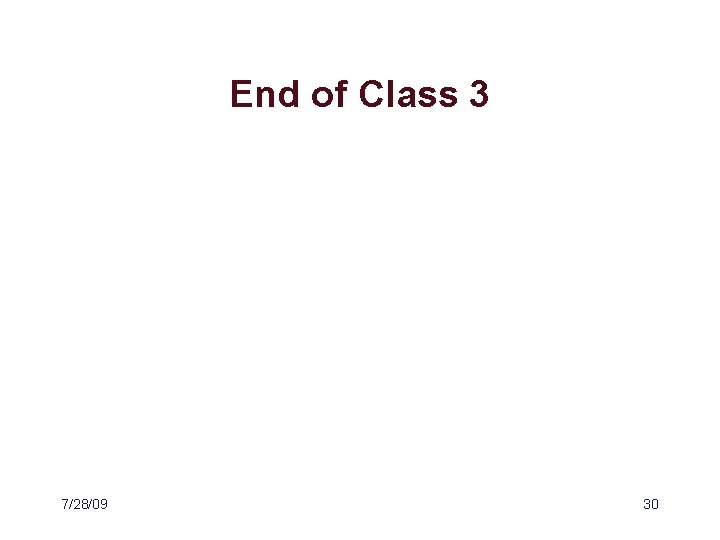

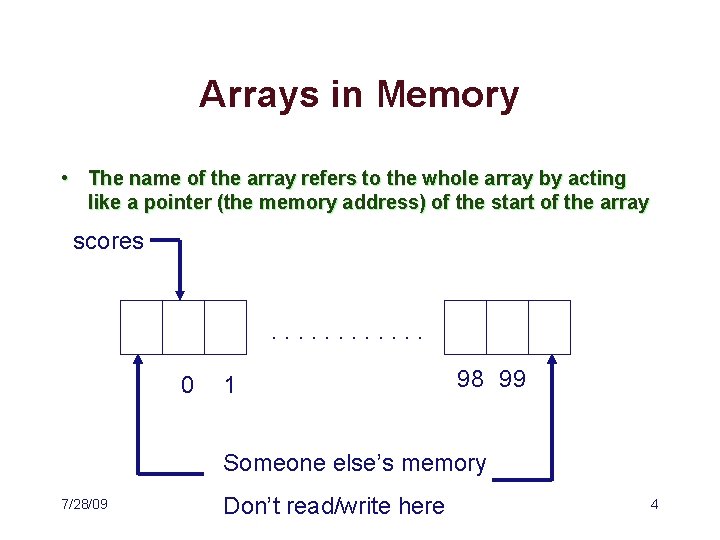

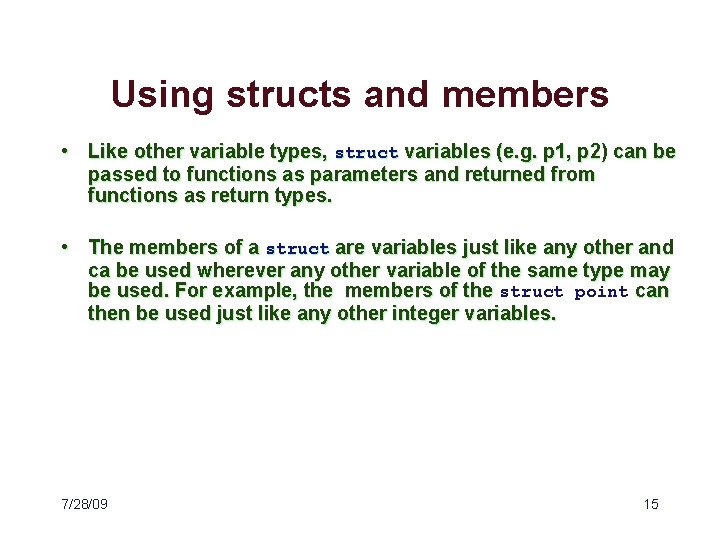

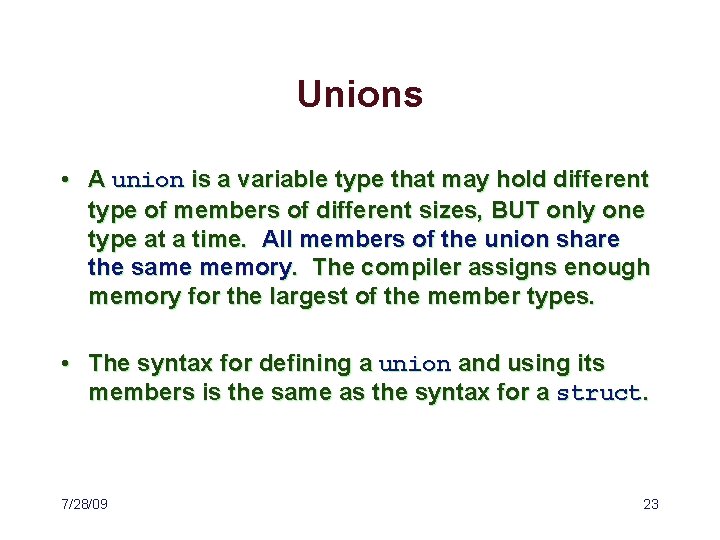

Unions • A union is a variable type that may hold different type of members of different sizes, BUT only one type at a time. All members of the union share the same memory. The compiler assigns enough memory for the largest of the member types. • The syntax for defining a union and using its members is the same as the syntax for a struct. 7/28/09 23

Formal Union Definition • The general form of a union definition is union tag { member 1_declaration; member 2_declaration; member 3_declaration; . . . member. N_declaration; }; where union is the keyword, tag names this kind of union, and member_declarations are variable declarations which define the members. Note that the syntax for defining a union is exactly the same as the syntax for a struct. 7/28/09 24

![union c union data int x char c8 int i union union. c union data { int x; char c[8]; } ; int i; union](https://slidetodoc.com/presentation_image/2fc0ead94df9dbbd0e56e44f6ab3b5bd/image-25.jpg)

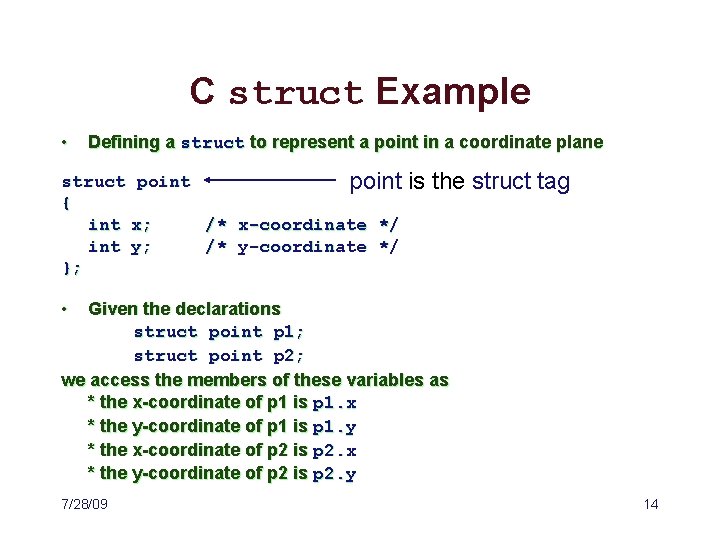

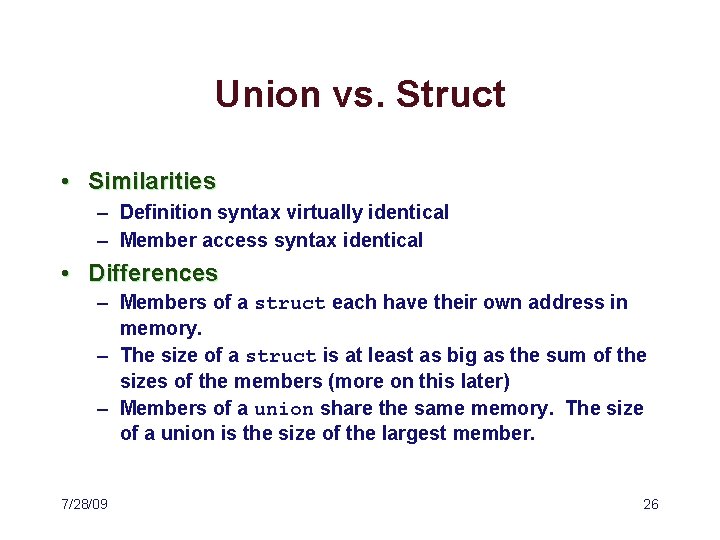

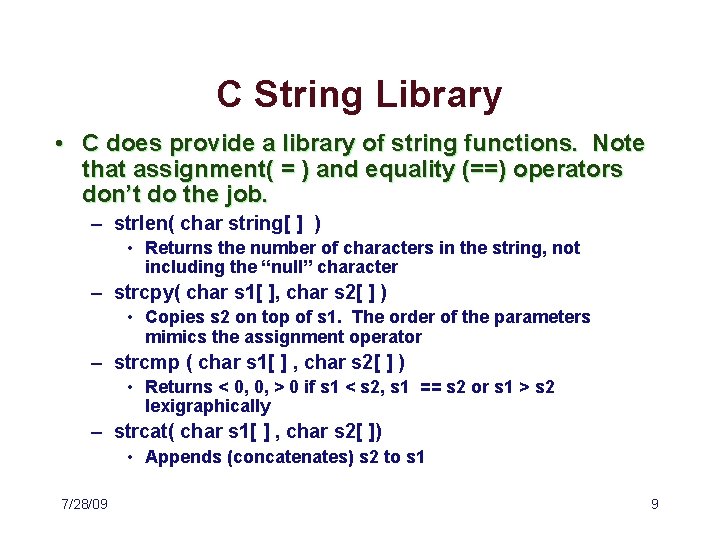

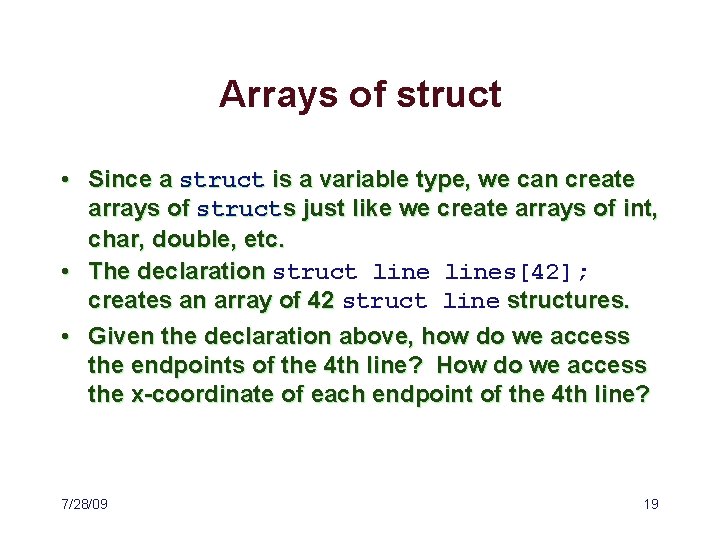

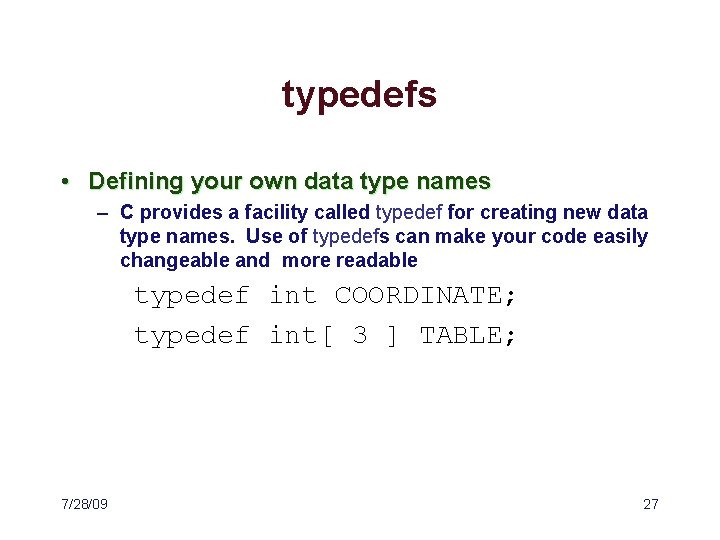

union. c union data { int x; char c[8]; } ; int i; union data item; item. x = 42; printf(“%d, %o, %x”, item. x, item. x ); for (i = 0; i < 8; i++ ) printf(“%x ”, item. c[i]); printf( “%s”, “n”); printf(“%sn”, “size of DATA = ”, sizeof(DATA)); 7/28/09 25

Union vs. Struct • Similarities – Definition syntax virtually identical – Member access syntax identical • Differences – Members of a struct each have their own address in memory. – The size of a struct is at least as big as the sum of the sizes of the members (more on this later) – Members of a union share the same memory. The size of a union is the size of the largest member. 7/28/09 26

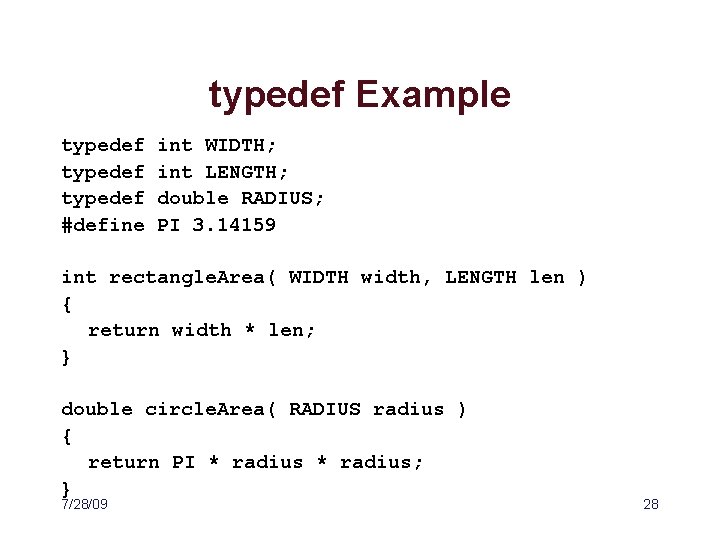

typedefs • Defining your own data type names – C provides a facility called typedef for creating new data type names. Use of typedefs can make your code easily changeable and more readable typedef int COORDINATE; typedef int[ 3 ] TABLE; 7/28/09 27

typedef Example typedef #define int WIDTH; int LENGTH; double RADIUS; PI 3. 14159 int rectangle. Area( WIDTH width, LENGTH len ) { return width * len; } double circle. Area( RADIUS radius ) { return PI * radius; } 7/28/09 28

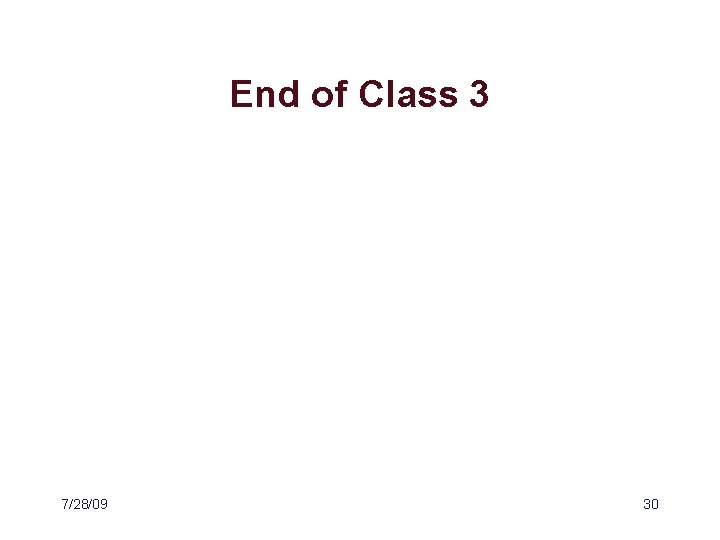

Using typedef with a struct • typedef is often used for structs to make coding easier for lazy programmers who can’t type well. In this case the struct tag (point) is not required. typedef int COORDINATE; typedef struct point { COORDINATE x; /* x-coordinate */ COORDINATE y; /* y-coordinate */ } POINT; /* POINT is an alias for this struct */ /* use the alias to declare variables */ POINT p 1, p 2, endpoint, origin; 7/28/09 29

End of Class 3 7/28/09 30