Processing EMG David De Lion UNLV Biomechanics Lab

Processing EMG David De. Lion UNLV Biomechanics Lab

Why do we process EMG? • Raw EMG offers us valuable information in a practically useless form • Raw EMG signals cannot be quantitatively compared between subjects • If electrodes are moved raw EMG signals cannot be quantitatively compared for the same subject

Types of Signal Processing • • Raw Half-wave rectified Full-wave rectified Filtering Averaging Smoothing Integration • • Root-mean Square Frequency spectrum Fatigue analysis Number of Zerocrossings • Amplitude Probability Distribution Function • Wavelet

Removing Bias • Low amplitude voltage offset present in hardware • Can be AC or DC • Calculate the mean of all the data • Subtract mean from each data point

Raw EMG • Unprocessed signal Amplitude of 0 -6 m. V Frequency of 10 -500 Hz • Peak-to-Peak Measured in m. V Represents the amount of muscle energy measured • Onset times can be determined • Analysis is mostly qualitative - -

Rectification • Only positive values are analyzed -Mean would be zero • Half-wave rectification - all negative data is discarded, positive data is kept. • Full-wave rectification- the absolute value of each data point is used • Full-wave is preferred

Filtering • Notch filter -Band reject filter; usually very narrow -For EMG normally set from 59 -61 Hz -Used to remove 60 Hz electrical noise -Also removes real data! -Too much noise will overwhelm the filter

Filtering • Band Pass filter -allows specified frequencies to pass -low end cutoff removes electrical noise associated with wire sway and biological artifacts -high end cutoff eliminates tissue noise at the electrode site -often set between 20 -300 Hz

Filtering • There are no perfect filters! • Face muscles can emit frequencies up to 500 Hz • Heart rate artifact can be eliminated with low end cutoffs of 100 Hz • Filters which include 60 Hz include the noise from equipment

Averaging • Average EMG can be used to quantify muscle activity over time • Measured in m. V • Values are averaged over a specified time window • Window can be moved or static • Moving windows are a digital smoothing technique • For moving windows the smaller the time window the less smooth the data will be

Averaging • For EMG window is typically between 100200 ms • Window is moved over the length of the sample • Moving averages introduce a phase shift • Moving averages create biased values -values are calculated from data which are common to the data used to calculate the previous value • Very commonly used technique

Integration • Calculation of area under the rectified signal • Measured in Vs • Values are summed over the specified time then divided by the total number of values • Values will increase continuously over time • The integrated average will represent 0. 637 of one-half of the peak to peak value • Quantifies muscle activity • Can be reset over a specified time or voltage

Root Mean Square • Recommended quantification method by Basmajian and De. Luca • Calculated by squaring each data point, summing the squares, dividing the sum by the number of observations, and taking the square root • Represents 0. 707 of one half of the peak-to-peak value

Number of Zero Crossings • Counting the number of times the amplitude of the signal crosses the zero line • Based on the idea that a more active muscle will generate more action potentials, which will cause more zero crossings in the signal • Primarily used before the FFT algorithm was widely available

Frequency Analysis • Fast Fourrie Transformation is used to break the EMG signal into its frequency components. • Frequency components are graphed as function of the probability of their occurrence • Useful in determining cutoff frequencies and muscle fatigue

Fatigue Analysis • Isometric contraction • The two most important parameters for fatigue analysis are the median and mean frequency. • Median frequency decreases with the onset of fatigue • If fatigue is being measured it is important to have a large band pass filter

Amplitude Probability Distribution Function • Illustrate variance in the signal • X-axis shows range of amplitudes • Y-axis shows the percentage of time spent at any given amplitude • Distribution during work should be bimodal -peak associated with effort -peak associated with rest

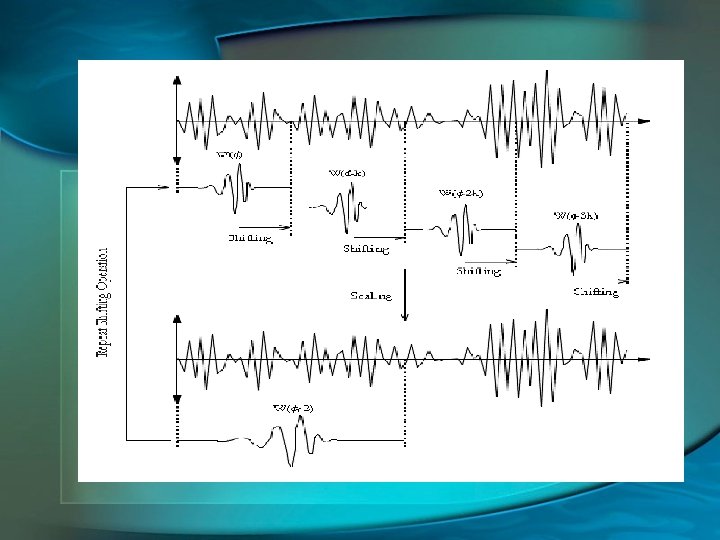

Wavelet analysis • Used for the processing of signals that are non-stationary and time varying • Wavelets are parts of functions or any function consists of an infinite number of wavelets • The goal is to express the signal as a linear combination of a set of functions • Obtained by running a wavelet of a given frequency through the original signal

Wavelet Analysis • This process creates wavelet coefficients • When an adequate number of coefficients have been calculated the signal can be accurately reconstructed • The signal is reconstructed as a linear combination of the basis functions which are weighted by the wavelet coefficients

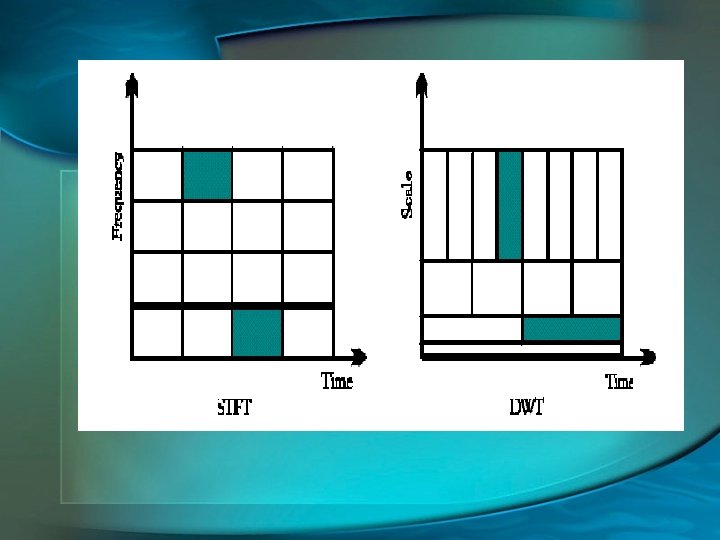

Wavelet Analysis • Time-frequency localization • Most of the energy of the wavelet is restricted to a finite time interval • Fourier transform is band limited • Produces good frequency localization at low frequencies, and good time localization at high frequencies • Segments, or tiles the time-frequency plane

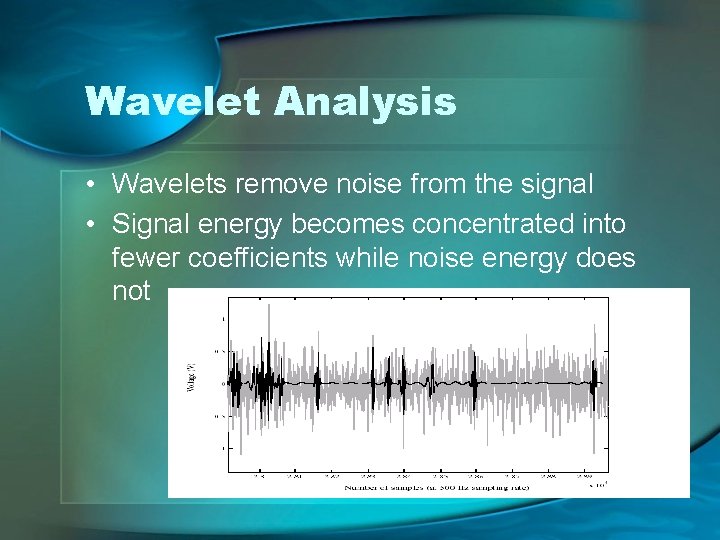

Wavelet Analysis • Wavelets remove noise from the signal • Signal energy becomes concentrated into fewer coefficients while noise energy does not

Normalizing • There is no absolute scale so direct comparisons between subjects or conditions cannot be made • Maximum voluntary contraction levels are often used to compare EMG readings between subjects (i. e. . 50% MVC) • Relies on subject to give max effort

Normalizing • Record contractions over a dynamic movement cycle • At least 4 repetitions are required • Peak values are averaged which creates an anchor point • Subsequent values are represented as a percentage of the anchor point

Conclusion • EMG offers a great deal of useful information • The information is only useful if it can be quantified • Quantifying EMG data can be a qualitative process

Thank You Any Questions?

Bibliography • Kleissen, R. F. M, Buurke, J. H. , Harlaar, J. , Zilvold, G. (1998) Electromyography in the Biomechanical analysis of human movement and its clinical application. Gait and Posture. Vol. 8, 143 -158 • Aminoff, M. J. (1978) Electromyography in Clinical Practice. Addison-Wesley Publishing Company, Menlo Park, CA • Dainty, D. A. , Norman, R. W. (1987) Standardized Biomechanical Testing in Sport. Human Kinetics Publishers, Champaign, IL • Cram, J. R. , Kasman, G. S. (1998) Introduction to Surface Electromyography. Aspen Publishers, Gaithersburg, MD • Medved, V. (2001) Measurement of Human Locomotion. CRC Press, New York, NY

Bibliography • Loeb, G. E. , Gans, C. (1986) Electromyography for Experimentalists. The University of Chicago Press, Chicago, IL • Basmajian, J. V. , De. Luca, C. J. (1985) Muscles Alive. Williams & Wilkins, Baltimore, MD • Moshou, D. , Hostens, I. , Ramon, H. (2000) Wavelets and Self. Organizing Maps in Electromyogram Analysis. Katholieke Universiteit Leuven • De. Luca, C. J. (1993) The Use of Surface Electromyography in Biomechanics. Neuro. Muscular Research Center, Boston University • De. Luca, C. J. (2002) Surface Electromyography: Detection and Recording. Delsys Incorporated.

- Slides: 29