Problem with NW and SW They are exhaustive

Problem with N-W and S-W They are exhaustive, with stringent statistical thresholds As the databases got larger, these began to take too long – computational constraints Need a program that runs an algorithm that is based on dynamic programming (substrings) but uses a heuristic approach (takes assumptions, quicker, not as refined). Therefore can deal with comparing a sequence against 100 million others in a relatively short time… the bigger the database, the more optimal the results.

Two heuristic approaches Each is based on different assumptions and calculations of probability thresholds (ie the statistical significance of results) 1. FASTA All proteins in the db are equally likely to be related to the query probability multiplied by the number of sequences in database 2. BLAST Query more likely to be related to a sequence its own length or shorter probability multiplied by N/n N: total number of residues in database n: length of subject sequence

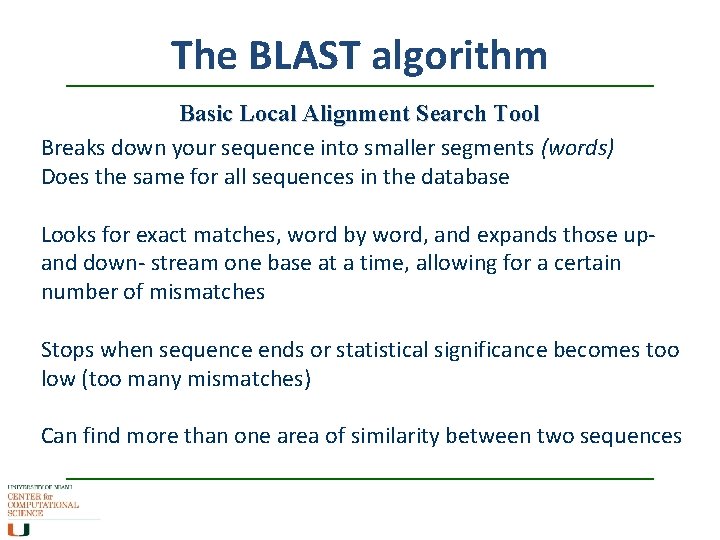

The BLAST algorithm Basic Local Alignment Search Tool Breaks down your sequence into smaller segments (words) Does the same for all sequences in the database Looks for exact matches, word by word, and expands those upand down- stream one base at a time, allowing for a certain number of mismatches Stops when sequence ends or statistical significance becomes too low (too many mismatches) Can find more than one area of similarity between two sequences

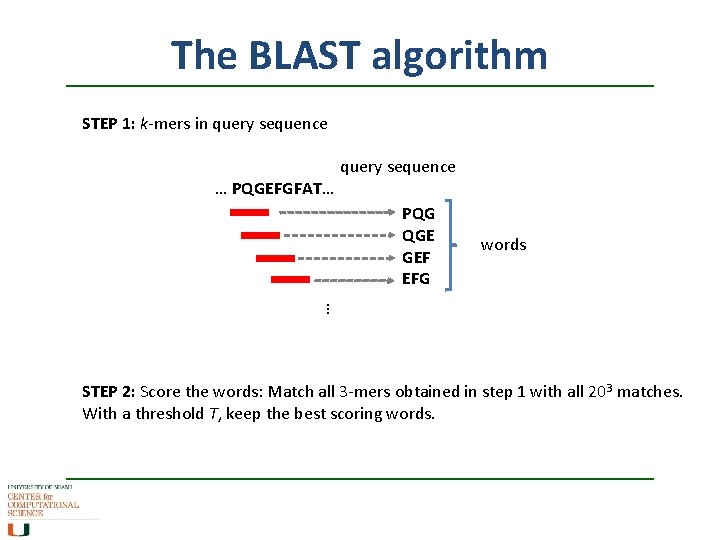

The BLAST algorithm STEP 1: k-mers in query sequence … PQGEFGFAT… PQG QGE GEF EFG words … STEP 2: Score the words: Match all 3 -mers obtained in step 1 with all 203 matches. With a threshold T, keep the best scoring words.

The BLAST algorithm STEP 3: organize the search words in a tree for efficient retrieval STEP 4: repeat step 2 -3 for each 3 -mer STEP 5: scan the database sequences to find exact matches of words, extend the exact matches to high-scoring segment pair (HSP). … PQGEFGFAT… … AQGEFEAQT… query sequence database sequence . . . -2 6 7 2 6 1 -2 -3 7 … HSP, score: 22

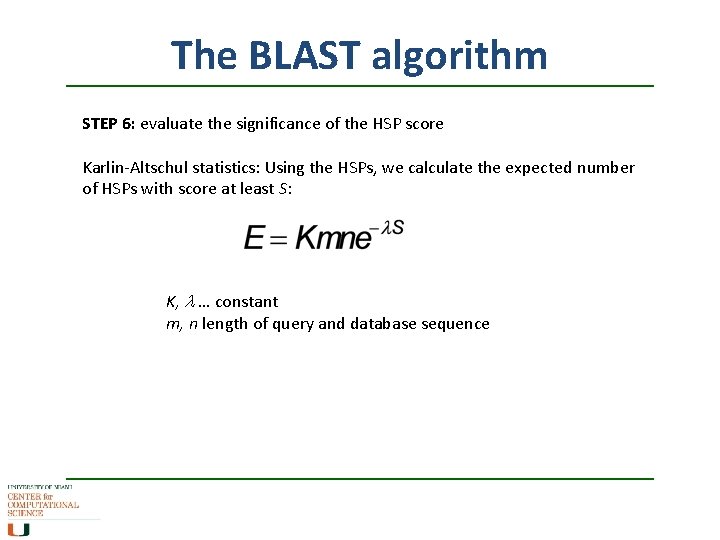

The BLAST algorithm STEP 6: evaluate the significance of the HSP score Karlin-Altschul statistics: Using the HSPs, we calculate the expected number of HSPs with score at least S: K, l … constant m, n length of query and database sequence

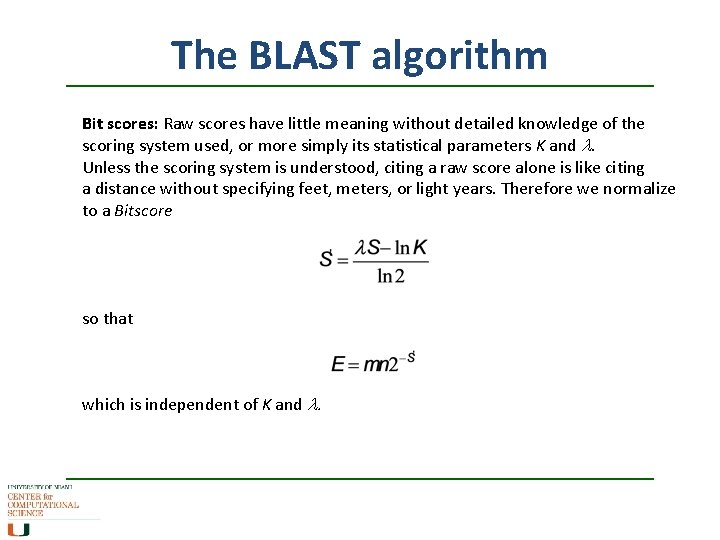

The BLAST algorithm Bit scores: Raw scores have little meaning without detailed knowledge of the scoring system used, or more simply its statistical parameters K and l. Unless the scoring system is understood, citing a raw score alone is like citing a distance without specifying feet, meters, or light years. Therefore we normalize to a Bitscore so that which is independent of K and l.

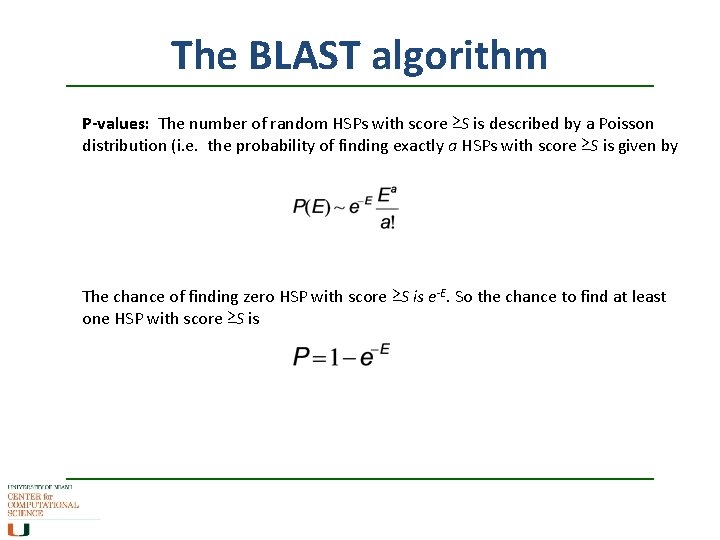

The BLAST algorithm P-values: The number of random HSPs with score ≥S is described by a Poisson distribution (i. e. the probability of finding exactly a HSPs with score ≥S is given by The chance of finding zero HSP with score ≥S is e-E. So the chance to find at least one HSP with score ≥S is

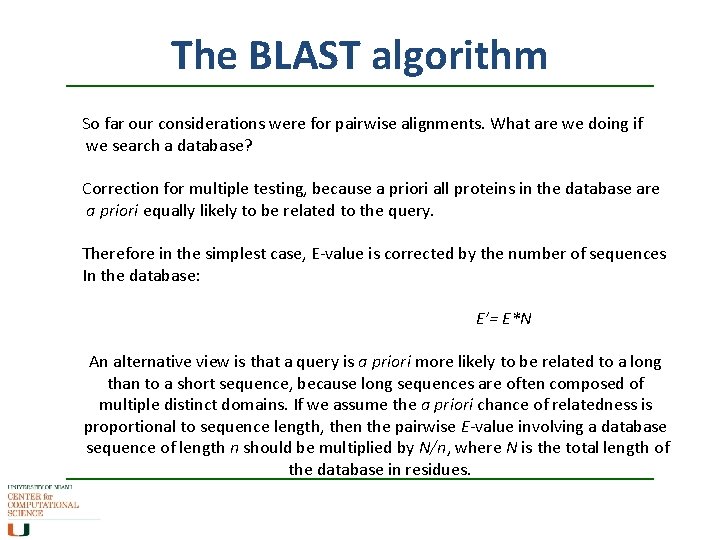

The BLAST algorithm So far our considerations were for pairwise alignments. What are we doing if we search a database? Correction for multiple testing, because a priori all proteins in the database are a priori equally likely to be related to the query. Therefore in the simplest case, E-value is corrected by the number of sequences In the database: E’= E*N An alternative view is that a query is a priori more likely to be related to a long than to a short sequence, because long sequences are often composed of multiple distinct domains. If we assume the a priori chance of relatedness is proportional to sequence length, then the pairwise E-value involving a database sequence of length n should be multiplied by N/n, where N is the total length of the database in residues.

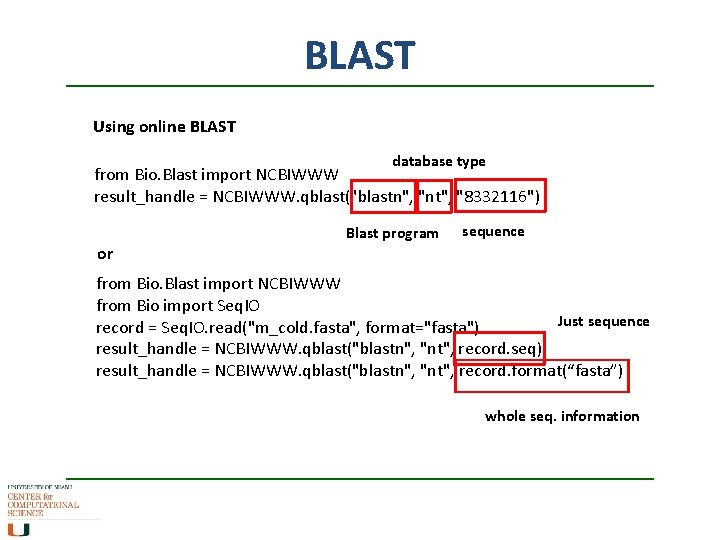

BLAST Using online BLAST database type from Bio. Blast import NCBIWWW result_handle = NCBIWWW. qblast("blastn", "nt", "8332116") Blast program sequence or from Bio. Blast import NCBIWWW from Bio import Seq. IO Just sequence record = Seq. IO. read("m_cold. fasta", format="fasta") result_handle = NCBIWWW. qblast("blastn", "nt", record. seq) result_handle = NCBIWWW. qblast("blastn", "nt", record. format(“fasta”) whole seq. information

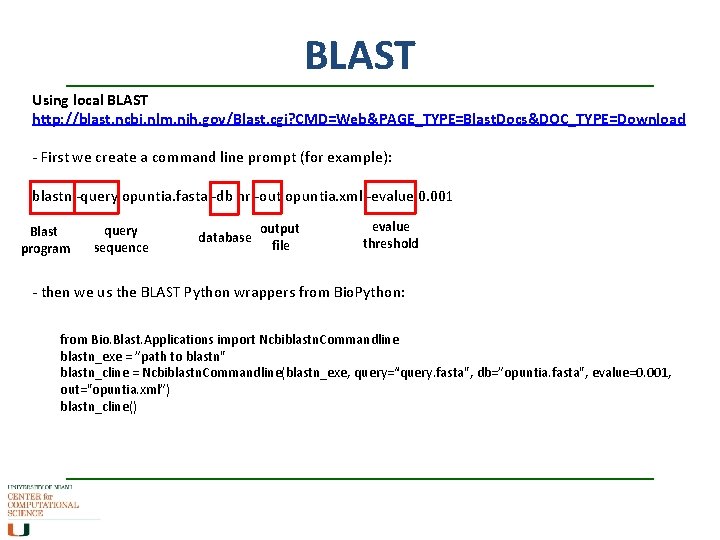

BLAST Using local BLAST http: //blast. ncbi. nlm. nih. gov/Blast. cgi? CMD=Web&PAGE_TYPE=Blast. Docs&DOC_TYPE=Download - First we create a command line prompt (for example): blastn -query opuntia. fasta -db nr -out opuntia. xml -evalue 0. 001 Blast program query sequence database output file evalue threshold - then we us the BLAST Python wrappers from Bio. Python: from Bio. Blast. Applications import Ncbiblastn. Commandline blastn_exe = ”path to blastn" blastn_cline = Ncbiblastn. Commandline(blastn_exe, query=“query. fasta", db=”opuntia. fasta", evalue=0. 001, out="opuntia. xml”) blastn_cline()

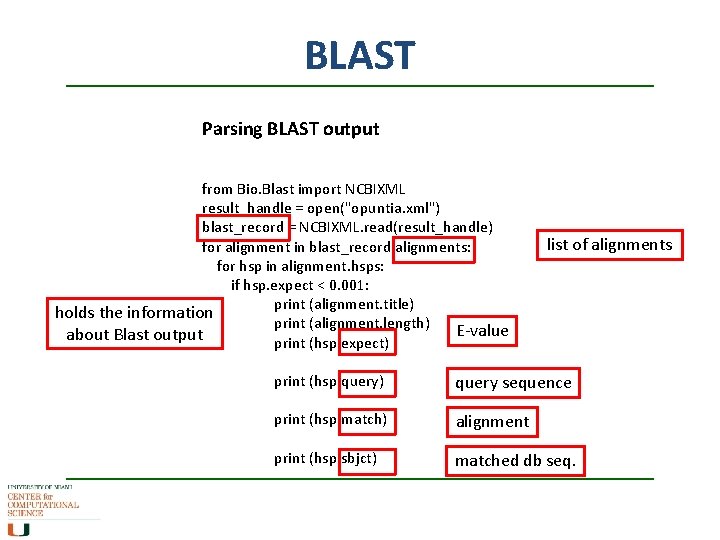

BLAST Parsing BLAST output from Bio. Blast import NCBIXML result_handle = open("opuntia. xml") blast_record = NCBIXML. read(result_handle) for alignment in blast_record. alignments: for hsp in alignment. hsps: if hsp. expect < 0. 001: print (alignment. title) holds the information print (alignment. length) E-value about Blast output print (hsp. expect) list of alignments print (hsp. query) query sequence print (hsp. match) alignment print (hsp. sbjct) matched db seq.

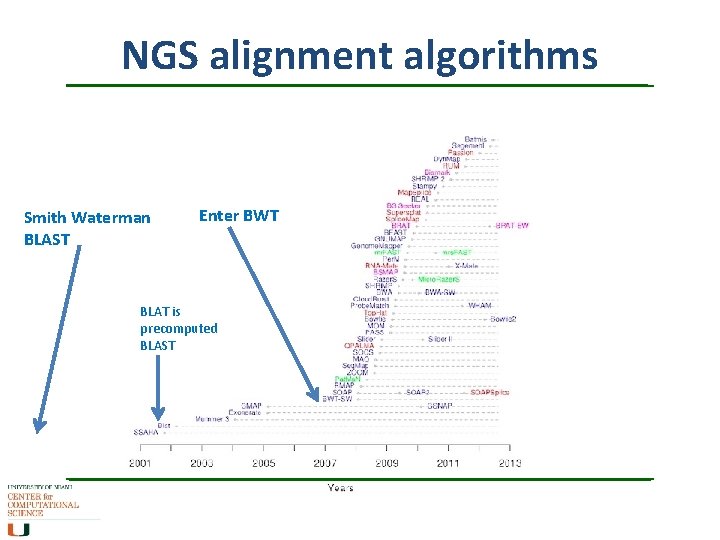

Algorithm evolution Smith Waterman Local alignment algorithm – finds small, locally similar regions (substrings), matrix-based, each cell in the matrix defined the end of a potential alignment. BLAST – start with highest scoring short pairs and extend and down the sequence. Great, but when you’re talking about millions of reads…

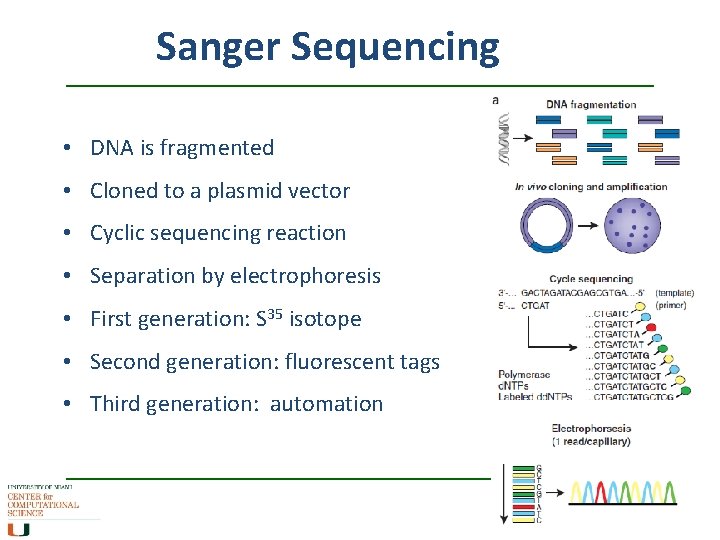

Sanger Sequencing • DNA is fragmented • Cloned to a plasmid vector • Cyclic sequencing reaction • Separation by electrophoresis • First generation: S 35 isotope • Second generation: fluorescent tags • Third generation: automation

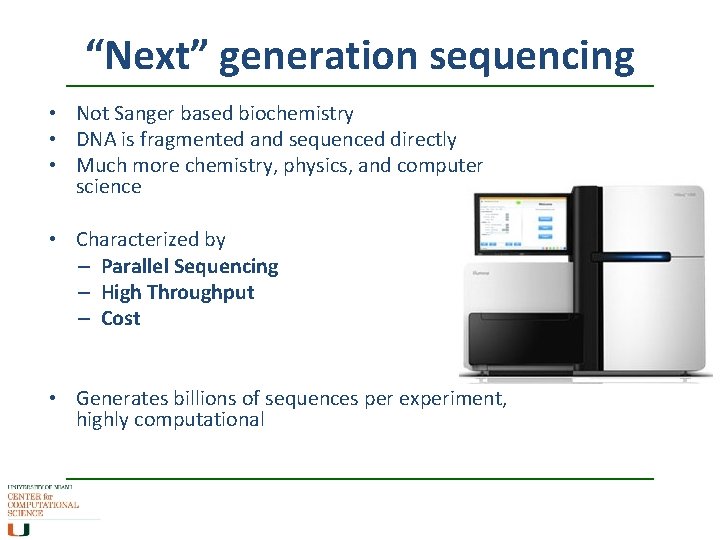

“Next” generation sequencing • Not Sanger based biochemistry • DNA is fragmented and sequenced directly • Much more chemistry, physics, and computer science • Characterized by – Parallel Sequencing – High Throughput – Cost • Generates billions of sequences per experiment, highly computational

Human Genome Project ENCODE project Hap. Map project SNP consortium Individual human genomes James Watson, Craig Venter, 3 asian gentlemen

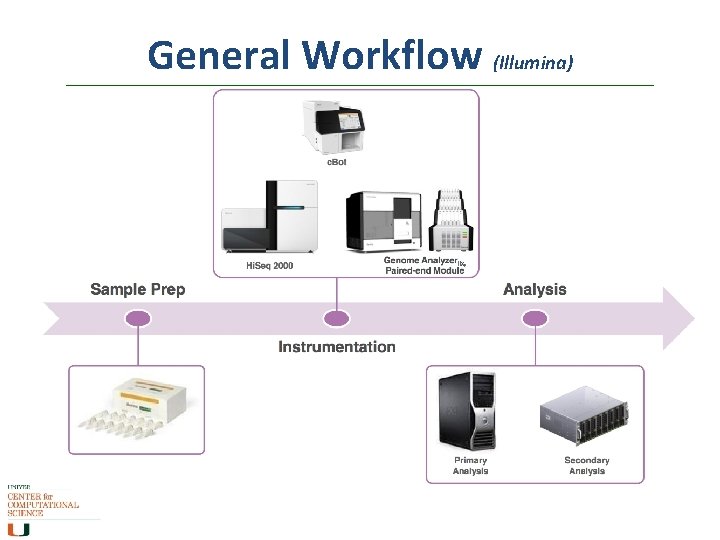

General Workflow (Illumina)

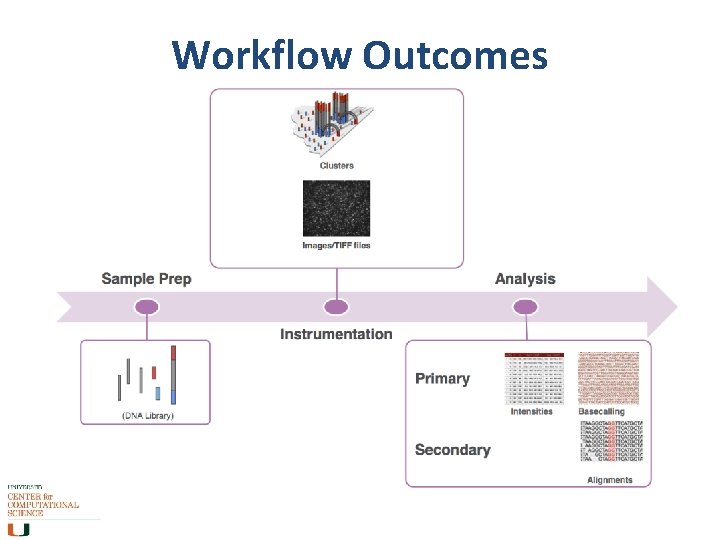

Workflow Outcomes

Data output • • Different technologies, though essentially similar Differences in number, length and quality of the sequences and in format of output Making data handling across platforms and analysis a challenge

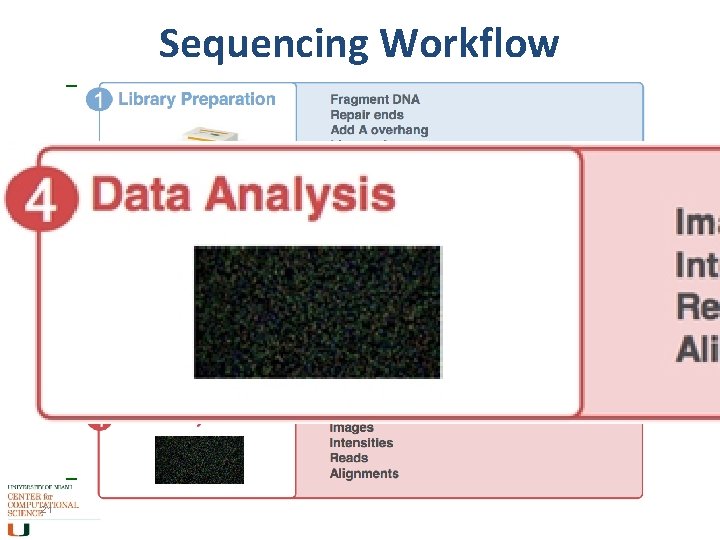

Sequencing Workflow 21

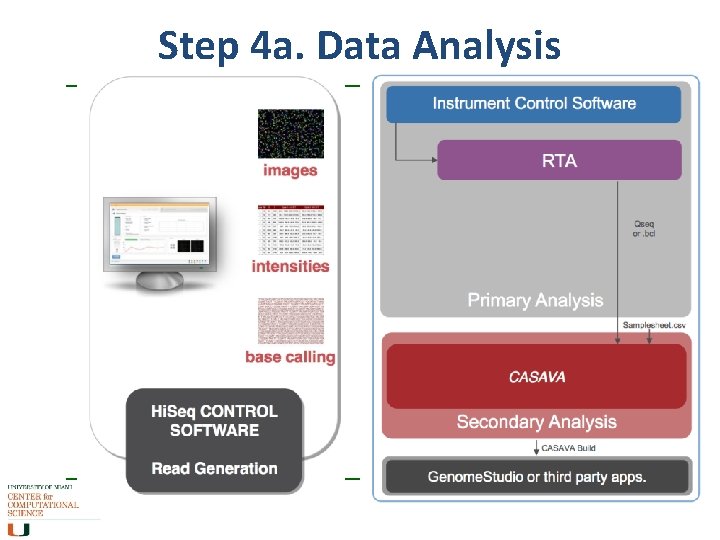

Step 4 a. Data Analysis

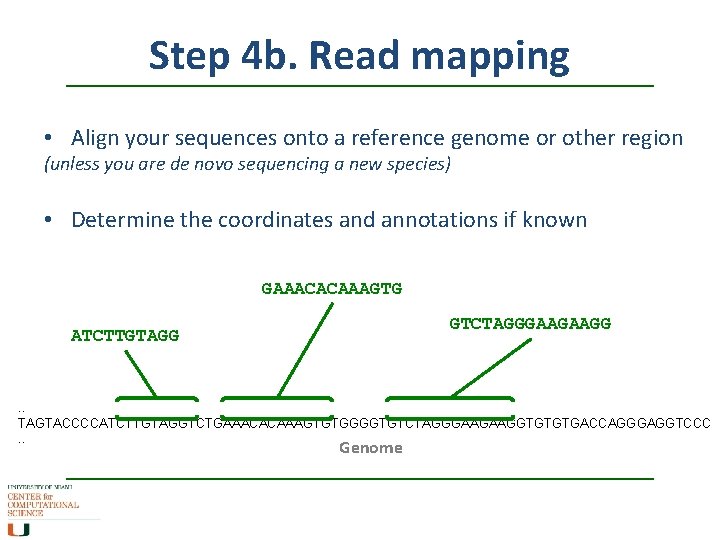

Step 4 b. Read mapping • Align your sequences onto a reference genome or other region (unless you are de novo sequencing a new species) • Determine the coordinates and annotations if known GAAACACAAAGTG GTCTAGGGAAGAAGG ATCTTGTAGG . . TAGTACCCCATCTTGTAGGTCTGAAACACAAAGTGTGGGGTGTCTAGGGAAGAAGGTGTGTGACCAGGGAGGTCCC. . Genome

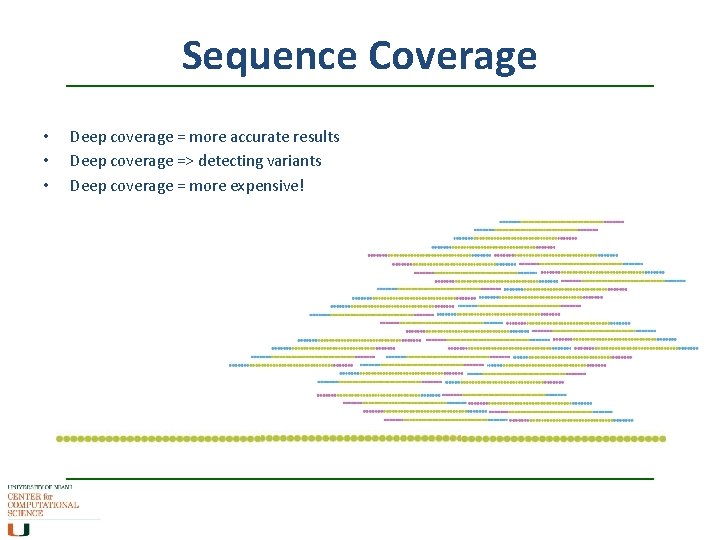

Sequence Coverage • • • Deep coverage = more accurate results Deep coverage => detecting variants Deep coverage = more expensive!

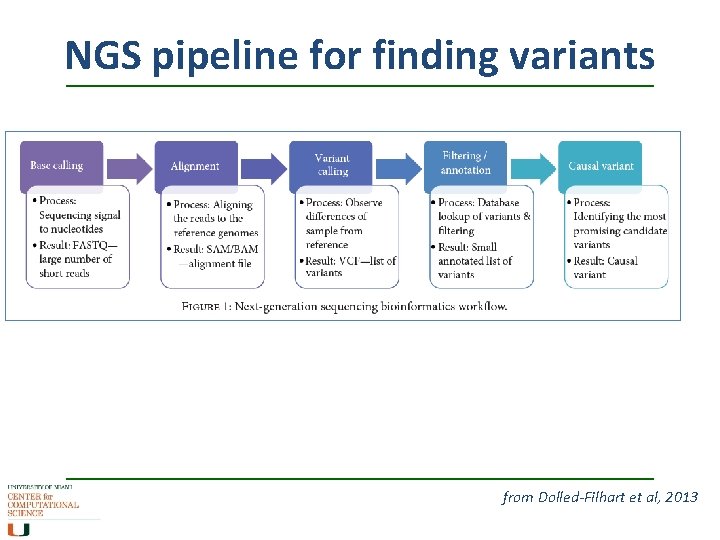

NGS pipeline for finding variants from Dolled-Filhart et al, 2013

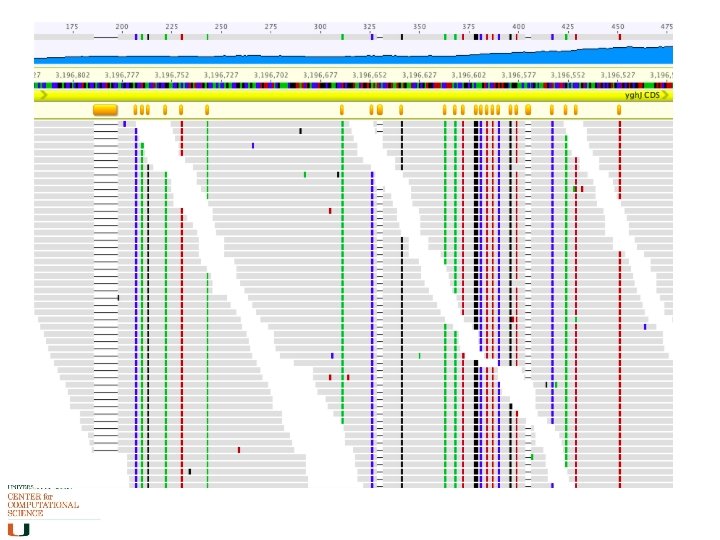

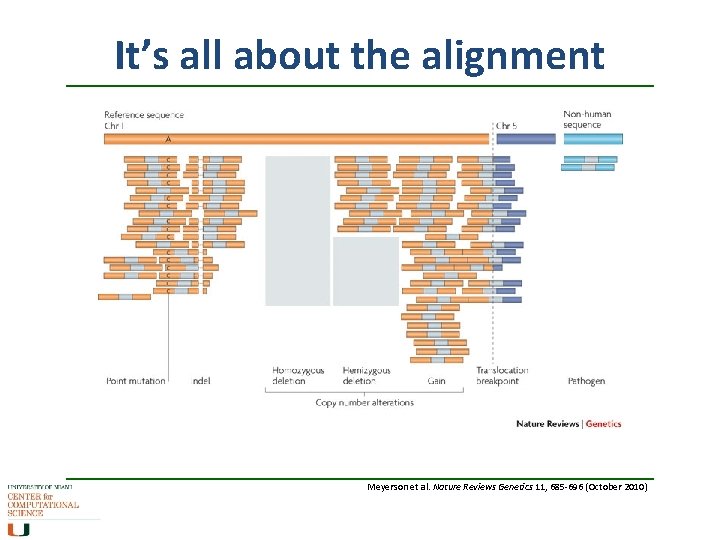

It’s all about the alignment Meyerson et al. Nature Reviews Genetics 11, 685 -696 (October 2010)

NGS alignment algorithms Smith Waterman BLAST Enter BWT BLAT is precomputed BLAST

- Slides: 28