Problem solving Some Questions We Will Consider How

Problem solving

Some Questions We Will Consider • How does the ability to solve a problem depend on how the problem is represented in the mind? • Is there anything special about “insight” problems? • How can analogies be used to help solve problems? • What is the difference between how experts in a field solve problems and how non experts solve problems?

What is problem? • A problem occurs when there is an obstacle between a present state and a goal, and it is not immediately obvious how to get around the obstacle. • Thus problem, as defined by psychologists, is difficult, and the solution is not immediately obvious. q. For example : When I ask students in my cognitive psychology class to indicate some problems they have solved or are currently working on, I get answers such as the following: q. Problems for math, chemistry, or physics courses; qgetting writing assignments in on time; qdealing with roommates, friends, and relationships in general; qdeciding what courses to take, qwhat career to go into; qwhether to go to graduate school or look for a job; qhow to pay for a new car

• You may notice, however, that my students’ list includes two different types of problems. • One type, such as solving a math or physics problem, is called a well-defined problem. • Well-defined problems usually have a correct answer, and there are certain procedures that, when applied correctly, will lead to a solution. • Another type of problem, like dealing with relationships or picking a career, is called an ill-defi ned problem. • Ill-defined problems, which occur frequently in everyday life, do not necessarily have one “correct answer, and the path to their solution is often unclear. • We will consider ill-defined problems at the end of the chapter when we discuss creative problem solving. Our main concern will be well-defined problems, because psychological research has focused on this type of problem. We begin by considering the approach of the Gestalt psychologists, who introduced the study of problem solving to psychology in the 1920,

The Gestalt Approach: Problem Solving as Representation and Restructuring • The Gestalt psychologists realized that one way to approach problem solving was to ask how problems are represented in a person’s mind. • Problem solving, for the Gestalt psychologists, was about • (1) how people represent a problem in their mind, and • (2) how solving a problem involves a reorganization or restructuring of this representation.

Representing a Problem in the Mind • The Gestalt psychologists were interested not only in perception, but also in learning, problem solving, and even attitudes and beliefs. • We can illustrate the Gestalt idea of representation and restructuring in problem solving by considering Figure 11. 2. • This problem, which was posed by Gestalt psychologist Wolfgang Kohler (1929), asks us to determine the length of the segment marked x, if the radius of the circle has a length r.

• The key to solving this problem is to create the mental representation of x as being a diagonal (a straight line joining two opposite corners) of the small rectangle. Representing x as the diagonal enables us to reorganize the representation by creating the rectangle’s other diagonal. • Once we realize that this diagonal is the radius of the circle, and that both diagonals are the same length, we can conclude that the length of x equals the length of the radius, r. • What is important about this solution is that it doesn’t require mathematical equations. Instead, the solution is obtained by first perceiving the object and then representing it in a different way. The Gestalt psychologists called the process of changing the problem’s representation restructuring.

Insight in Problem Solving • The Gestalt psychologists also introduced the idea that restructuring is associated with insight—a sudden realization of a problem’s solution. • Gestalt psychologists’ emphasis on insight is reflected in the types of problems they posed. • The solution to most of their problems involves discovering a crucial element that leads to solution of the problem. • The Gestalt psychologists assumed that people solving their problems were experiencing insight because the solutions usually seemed to come to them all of a sudden. • Modern researchers have debated whether insight actually exists, with some pointing to the fact that people often experience problem solving as an “Aha!” experience—at one point they don’t have the answer, and then next minute they have solved the problem— which is one of the characteristics associated with insight problems. • However, other researchers have emphasized the lack of evidence, other than untrustworthy reports, to support the specialness of the insight experience.

Experiment • Janet Metcalfe and David Wiebe (1987) did an experiment designed to distinguish between insight problems and noninsight problems. • Their starting point was the idea that there should be a basic difference between how participants feel they are progressing toward a solution as they are working on an insight problem, and how they feel as they are working on a noninsight problem. • They predicted that participants working on an insight problem, in which the answer appears suddenly, should not be very good at predicting how near they are to a solution, but that participants working on a noninsight problem, which involves a more methodical process, would have some knowledge that they are getting closer to the solution.

• To test this hypothesis, Metcalfe and Wiebe gave participants insight problems, like the ones in the demonstration below, and noninsight problems and had them make “warmth” judgments every 15 seconds, as they were working on the problems. • Ratings closer to “hot” (7 on a 7 -point scale) were used when they felt they were getting close to a solution, and ratings closer to “cold” (1 on the scale) were used when they felt that they were far from a solution.

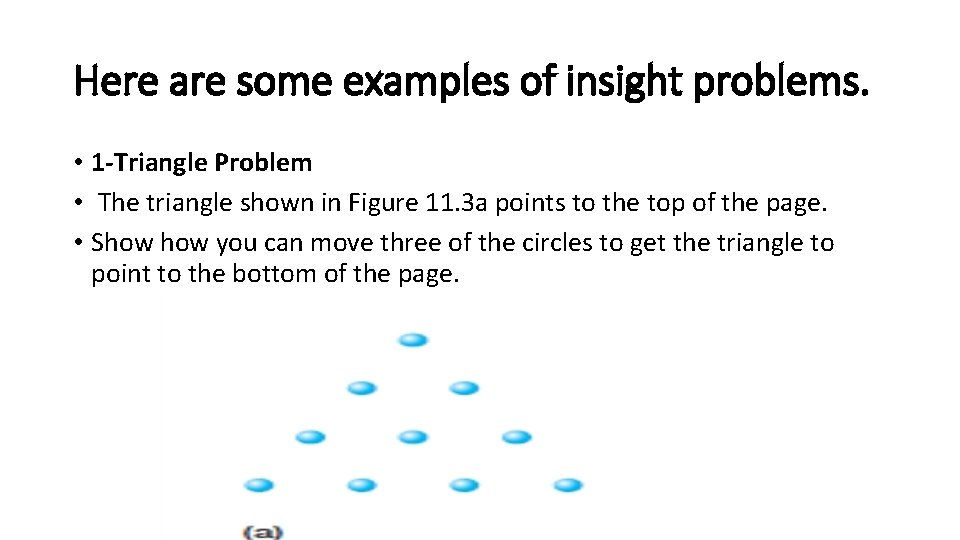

Here are some examples of insight problems. • 1 -Triangle Problem • The triangle shown in Figure 11. 3 a points to the top of the page. • Show you can move three of the circles to get the triangle to point to the bottom of the page.

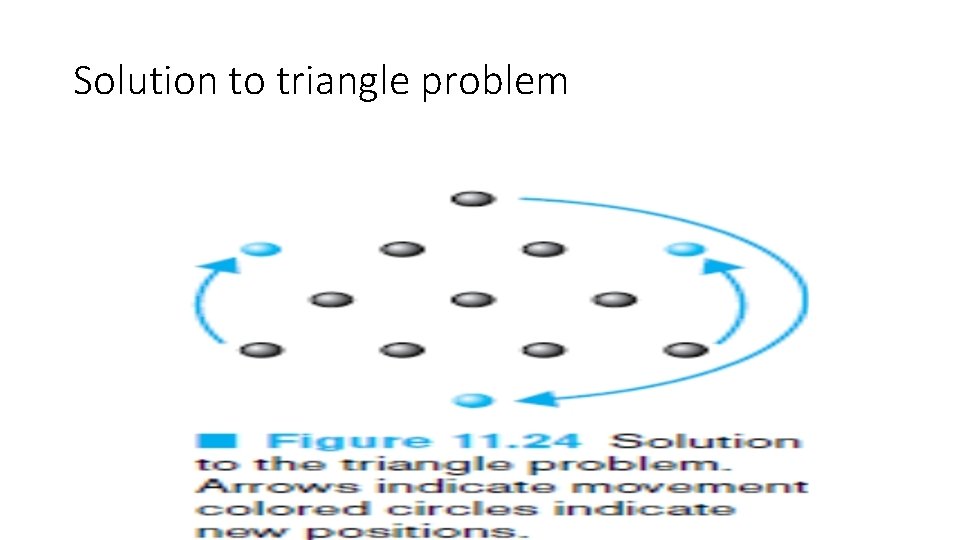

Solution to triangle problem

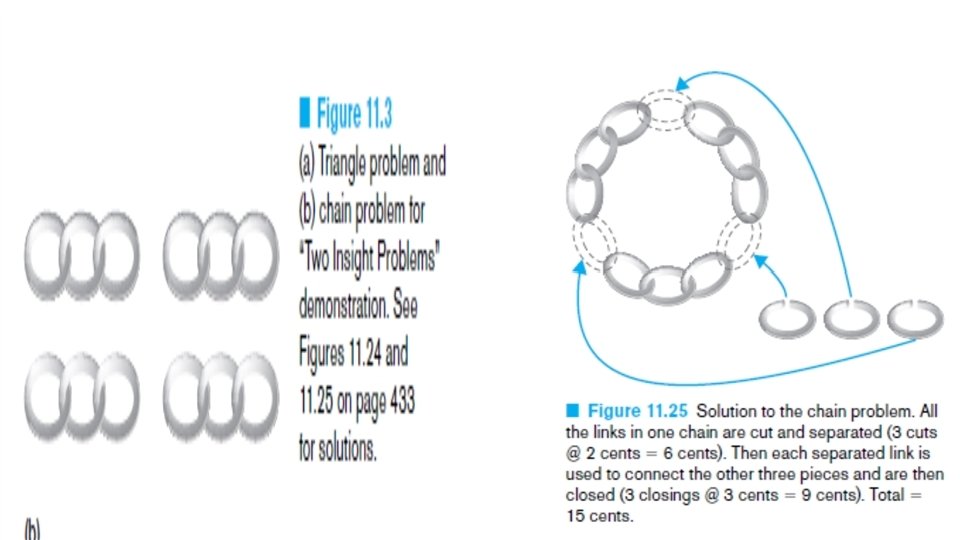

2. Chain Problem • A woman has four pieces of chain. Each piece is made up of three links, as shown in Figure 11. 3 b. • She wants to join the pieces into a single closed loop of chain. To open a link costs 2 cents and to close a link costs 3 cents. • She only has 15 cents. • How does she do it? • As you work on these problems, see whether you can monitor your progress. Do you feel as though you are making steady progress toward a solution, until eventually it all adds up.

• To the answer, or as though you were not really making much progress, but, if you did solve the problem, you experienced the solution all of a sudden, like an “Aha!” experience? • For noninsight problems, Metcalfe and Wiebe used algebra problems like the following, which were taken from a high school mathematics text. • ● Solve for x: (1/5)x 10 + 25 • ● Factor 16 y 2 -40 yz +25 z 2 • The results of their experiment are shown in Figure 11. 4, which indicates the median warmth ratings for all of the participants for the minute just before the participants solved the two kinds of problems.

• The results of their experiment are shown in Figure 11. 4, which indicates the median warmth ratings for all of the participants for the minute just before the participants solved the two kinds of problems. • For the insight problems (solid line), warmth ratings remain low at 2 or 3 until just before the problem is solved. • Notice that 15 seconds before the solution, the medium rating is a relatively cold 3. • In contrast, for the algebra problems (dashed line), the ratings gradually increased until the problem was solved. Thus, Metcalfe and Wiebe demonstrated a difference between insight and noninsight problems.

Obstacles to Problem Solving • One of the major obstacles to problem solving, according to the Gestalt psychologists, is • fixation—people’s tendency to focus on a specific characteristic of the problem that keeps them from arriving at a solution. • One type of fixation that can work against solving a problem is focusing on familiar uses of an object. • Restricting the use of an object to its familiar functions is called functional fixedness.

• The candle problem, first described by Karl Duncker (1945), illustrates how functional fixedness can hinder problem solving. • In his experiment, he asked participants to use various objects to complete a task. The following demonstration asks you to try to solve Duncker’s problem by imagining that you have the specified objects. • Demonstration The Candle Problem You are in a room with a corkboard on the wall. • You are given the materials— some candles, matches in a matchbox, and some tacks. • Your task is to stand a candle on the corkboard so it will burn without dripping wax on the floor.

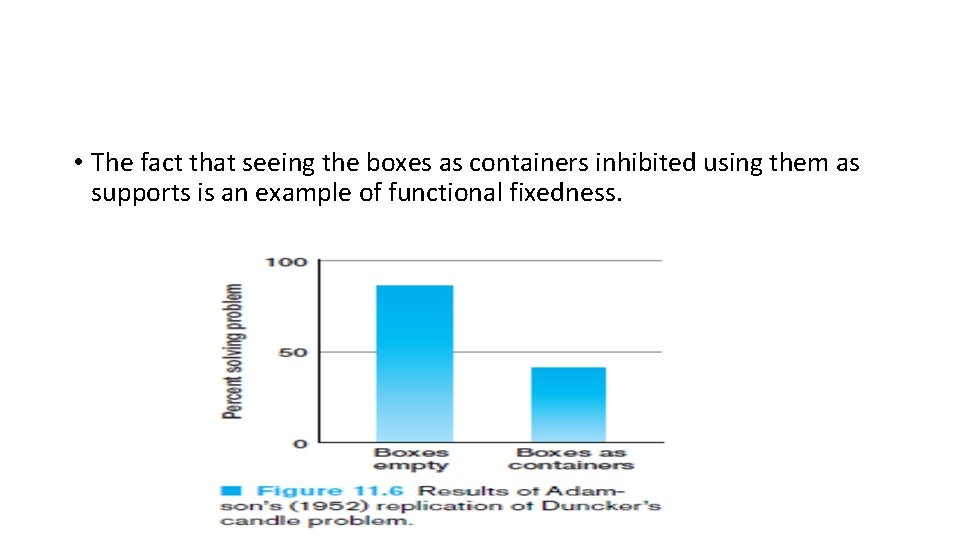

• The solution to the problem occurs when the person realizes that the matchbox can be used as a support rather than as a container. • When Duncker did this experiment, he presented one group of participants with small cardboard boxes containing the materials (candles, tacks, and matches) and presented another group with the same materials, but outside the boxes, so the boxes were empty. • When he compared the performance of the two groups, he found that the group that had been presented with the boxes as containers found the problem more difficult than did the group that was presented with empty boxes.

• The fact that seeing the boxes as containers inhibited using them as supports is an example of functional fixedness.

• Robert Adamson (1952) repeated Duncker’s experiment and obtained the same result: Participants who were presented with empty boxes were twice as likely to solve the problem as participants who were presented with boxes that were used as containers (Figure 11. 6).

two-string problem • The fact that seeing the boxes as containers inhibited using them as supports is an example of functional fixedness. Another demonstration of functional fixedness is provided by Maier’s (1931) two-string problem, in which the participants’ task was to tie together two strings that were hanging from the ceiling. • This is difficult because the strings are separated, so it is impossible to reach one of them while holding the other (Figure 11. 7). • Other objects available for solving this problem were a chair and a pair of pliers.

• To solve this problem, participants needed to tie the pliers to one of the strings to create a pendulum, which could be swung to within the person’s reach. • There are two things that are particularly significant about this problem. • First, 60 percent of the participants did not solve the problem because they focused on the usual function of pliers and did not think of using them as a weight. • Second, when Maier set the string into motion by “accidentally” brushing against it, 23 of 37 participants who hadn’t solved the problem after 10 minutes proceeded to solve it within 60 seconds. • Seeing the string swinging from side to side apparently triggered the insight that the pliers could be used as a weight to create a pendulum.

• In Gestalt terms, the solution to the problem occurred once the participants restructured their representation of how to achieve the solution (get the strings to swing from side to side) and their representation of the function of the pliers (they can be used as a weight to create a pendulum). • Both the candle problem and the two-string problem were difficult because of people’s preconceptions about the uses of objects. • The Gestalt psychologists also created problems in which the fixation was created by what a person experienced as he or she tried to solve the problem. When a person encounters a situation that influences his or her approach to a problem, this is called situationally produced mental set.

- Slides: 30