Probability Judgments General q Dates Every 2 weeks

Probability Judgments: General q Dates: Every 2 weeks q Objectives: Ø Presentation of phenomena Ø Explication of mechanisms Ø Improving capabilities q Exercises: Training

Probability Judgments: Overview I q Heuristics and Bias Approach: Focal heuristics: Ø Availability heuristic Ø Representativeness heuristic. Ø Anchoring and adjustment.

Probability Judgments: Overview I q Biases in handling probability information Ø Probability matching. Ø Conditional probability. Ø Base rate neglect. q Two process theories and the cognitive reflection test (CRT).

Probability Judgments: Overview II q Probabilistic Reasoning: Methods Ø Theory of Probabilistic reasoning. Ø Variants of Bayes theorem. q Probabilistic Reasoning: Classical problems Ø Cab problem. Ø Monty Hall problem.

Probability Judgments: Overview II q Improving probabilistic reasoning: Ø Natural sampling (natural frequencies). Ø Using graphical devices. q Explaining the mechanisms underlying the improvements: Ø Evolutionary approach. Ø Problem solving approach.

Probability Judgments: Overview III q Criticisms of the Heuristic and Bias Approach Ø General criticisms. Ø Specific criticisms. Ø Answers to criticisms.

Probability Judgments: Overview III q Paradoxes and Biases in Decision making Ø Sunk cost. Ø Framing effects. Ø Nontransitivity of decisions. Ø Allais & Ellsberg Paradox. Ø Prospect theory and mental accounting.

Example 1: Conditional probabilities: q Which of the following two probabilities is higher: Ø The probability that a person who is smoking suffers from lung cancer? Ø The probability the a person suffering from lung cancer is smoking?

Example 1: Conditional probabilities: q Which of the following two probabilities is higher: Ø The probability that a person with migration background has committed a crime? Ø The probability that a person having committed a crime has a migration back ground?

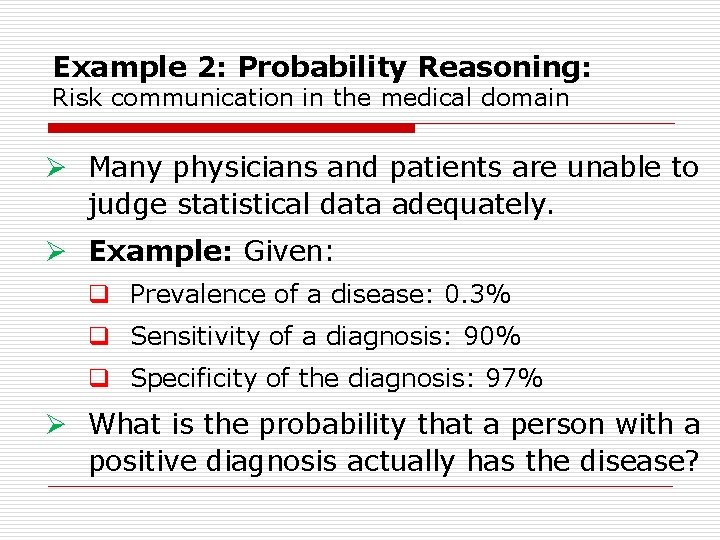

Example 2: Probability Reasoning: Risk communication in the medical domain Ø Many physicians and patients are unable to judge statistical data adequately. Ø Example: Given: q Prevalence of a disease: 0. 3% q Sensitivity of a diagnosis: 90% q Specificity of the diagnosis: 97% Ø What is the probability that a person with a positive diagnosis actually has the disease?

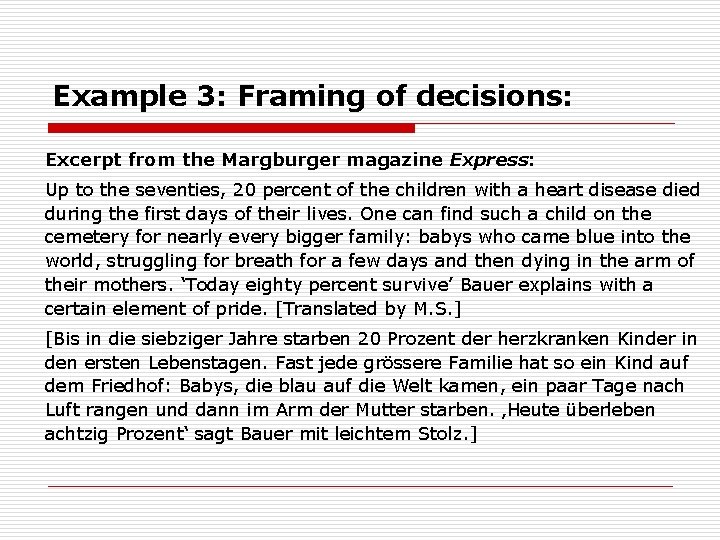

Example 3: Framing of decisions: Excerpt from the Margburger magazine Express: Up to the seventies, 20 percent of the children with a heart disease died during the first days of their lives. One can find such a child on the cemetery for nearly every bigger family: babys who came blue into the world, struggling for breath for a few days and then dying in the arm of their mothers. ‘Today eighty percent survive’ Bauer explains with a certain element of pride. [Translated by M. S. ] [Bis in die siebziger Jahre starben 20 Prozent der herzkranken Kinder in den ersten Lebenstagen. Fast jede grössere Familie hat so ein Kind auf dem Friedhof: Babys, die blau auf die Welt kamen, ein paar Tage nach Luft rangen und dann im Arm der Mutter starben. ‚Heute überleben achtzig Prozent‘ sagt Bauer mit leichtem Stolz. ]

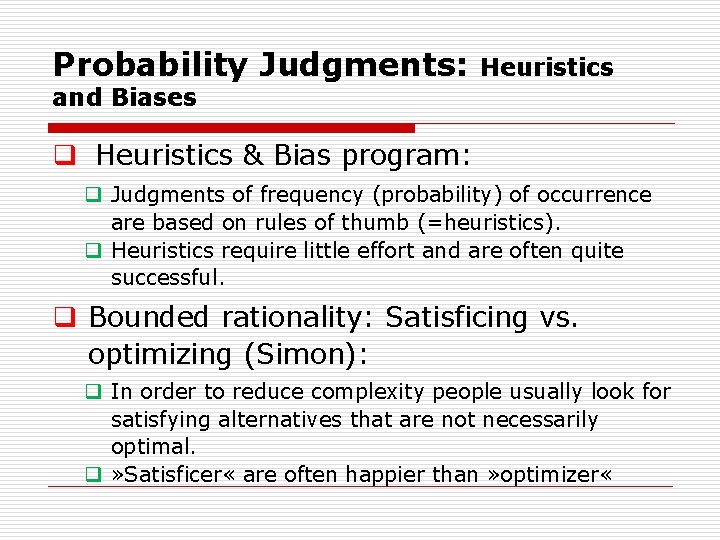

Probability Judgments: Heuristics and Biases q Heuristics & Bias program: q Judgments of frequency (probability) of occurrence are based on rules of thumb (=heuristics). q Heuristics require little effort and are often quite successful. q Bounded rationality: Satisficing vs. optimizing (Simon): q In order to reduce complexity people usually look for satisfying alternatives that are not necessarily optimal. q » Satisficer « are often happier than » optimizer «

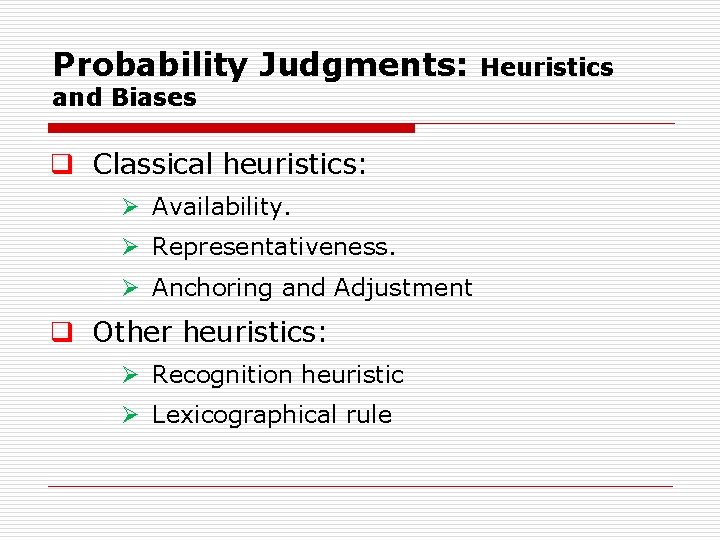

Probability Judgments: and Biases q Classical heuristics: Ø Availability. Ø Representativeness. Ø Anchoring and Adjustment q Other heuristics: Ø Recognition heuristic Ø Lexicographical rule Heuristics

Availability heuristic: Functioning The frequency of an event is judged according to the easiness with which particluar instances can be generated (or come to mind). Problem: Availability of instances and frequency of occurence are generally not correlated.

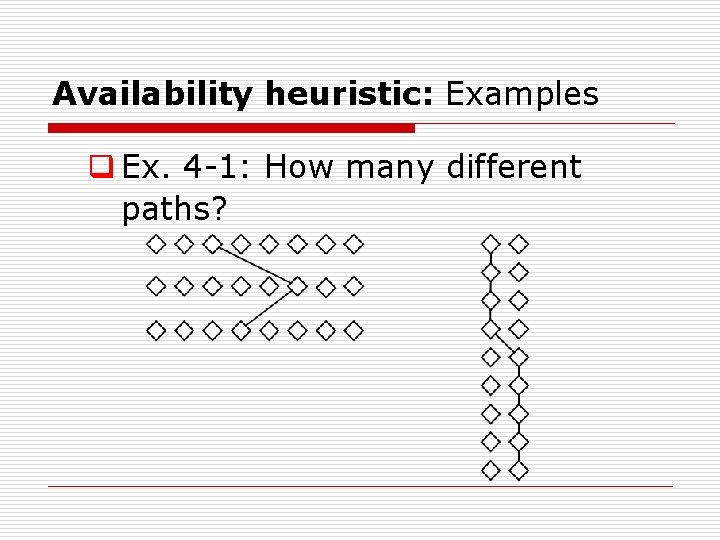

Availability heuristic: Examples q Ex. 4 1: How many different paths?

Availability heuristic: Examples q Ex. 4 2: Memory and availability Ø Two lists A and B: List A: 19 famous women and 20 common names of men. List B: 19 famous men and 20 common names of women. Ø Results: Famous names are judged as being more frequent and are better remembered.

Availability heuristic: Examples q Ex. 4 2: Memory and availability Ø Being killed by falling aircraft parts vs. being killed by an attacking shark. Ø Diabetes vs. murder. Ø Car accident vs. stomach cancer. q Attack on WTC in 9/11 2001 and increase in death due to car accidents.

Availability heuristic: Imagination and availability Imaginative techniques foster false memories and increase availability. q Ex. 4 5: Imagination and estimation of acquiring a disease. Ø Factor 1: Imagination vs. No Imagination Instruction to imagine to have been infected by the disease and to suffer from its reported symptoms for three weeks vs. no instruction. Ø Factor 2: Concreteness of to be imagined symptoms: Concrete and easy to imagine: headache. Difficult to imagine: vague sense of disorientation.

Availability heuristic: Imagination and availability q Ex. 4 5: Imagination and estimation of acquiring a disease. Results: Ø Imagination influenced subjective probability of getting the disease. Ø Both factors had an influence: Instruction to imagine increases subjective probability. Ø In condition with imagination: Concreteness of symptoms increases subjective probability.

Availability heuristic: Vividness and personal experience q Ex. 4 6: An anecdote (Nisbett & Ross, 1980): Urs Bürli intends to buy a new car. He decides to purchase a Swedish car: a Saab or a Volvo. Since he is unsure with respect to the relative robustness of both brands he studies the relevant journals and repair statistics. On the basis of this information that includes hundreds of cases he finally decides to buy a Saab.

Availability heuristic: Vividness and personal experience q Ex. 4 6: An anecdote (Nisbett & Ross, 1980): On Sunday evening just before fixing the purchase he meets his friend Hans Rudi at his regular’s table in their pub and he talks with him about his decision. Hans Rudi reacts with astonishment: » I have an acquaintance possessing a Saab. First the brakes were defect then the injection pump broke. Furthermore there were always troubles with the electronics. After 3 years he sold the car for peanuts «.

Availability heuristic: Vividness and personal experience q Ex. 4 6: An anecdote (Nisbett & Ross, 1980): Due to the information from his friend Urs Burli decides to purchase a Volo. q On the basis of a single vivid report the evidence from hundreds of cases is ignored. q Generally, humans assign higher weight to information from personal experiences than to abstract statistical information.

Availability heuristic: Vividness and personal experience q E. g. Schindler’s list (from Steven Spielberg) had a much greater im pact on peoples’ perception of the atrocities of the Nazi regime than abstract statistics about how many millions of Jewish people were kil led by the regime. q The reason is obvious: The film portrays realistical ly the fate of individual people thus enabling one to witness the con crete destinies of these persons.

Availability heuristic: Examples and personal experience q Arguments based on examples: » My grand farther smoked more than 40 cigarettes a day and he lived nevertheless for over 90 years «. q The only reasonable answer: » Ok, but what do you want to prove with your statement? Dozens of empirical studies have found a positive relation between smoking and cancer as well as between smoking and a shortened life time «.

Representativeness Heuristic I Assessment of the frequency of events according to similarity / typicality. Example: Evaluation of the probability of random sequences: Choosing numbers in lotteries.

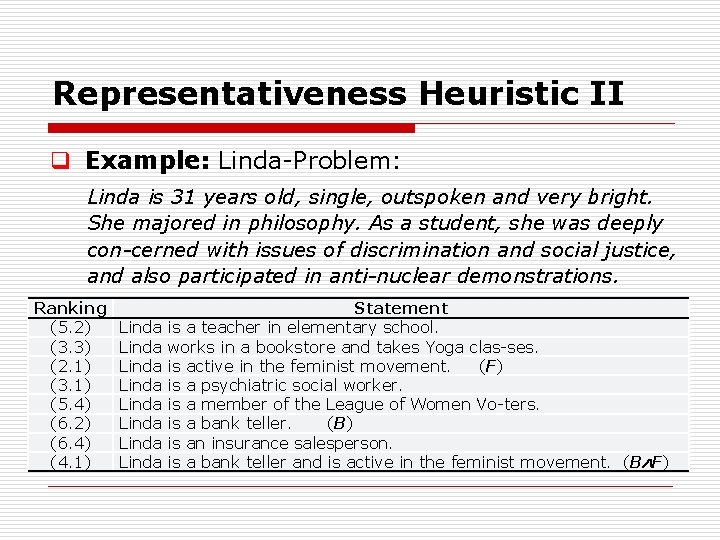

Representativeness Heuristic II q Example: Linda Problem: Linda is 31 years old, single, outspoken and very bright. She majored in philosophy. As a student, she was deeply con cerned with issues of discrimination and social justice, and also participated in anti nuclear demonstrations. Ranking (5. 2) (3. 3) (2. 1) (3. 1) (5. 4) (6. 2) (6. 4) (4. 1) Linda Linda Statement is a teacher in elementary school. works in a bookstore and takes Yoga clas ses. is active in the feminist movement. (F) is a psychiatric social worker. is a member of the League of Women Vo ters. is a bank teller. (B) is an insurance salesperson. is a bank teller and is active in the feminist movement. (B F)

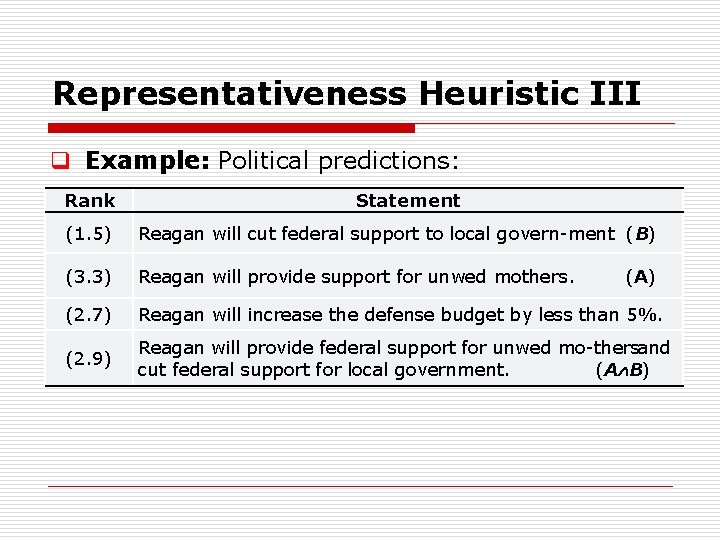

Representativeness Heuristic III q Example: Political predictions: Rank Statement (1. 5) Reagan will cut federal support to local govern ment. (B) (3. 3) Reagan will provide support for unwed mothers. (2. 7) Reagan will increase the defense budget by less than 5%. (2. 9) Reagan will provide federal support for unwed mo thersand cut federal support for local government. (A B) (A)

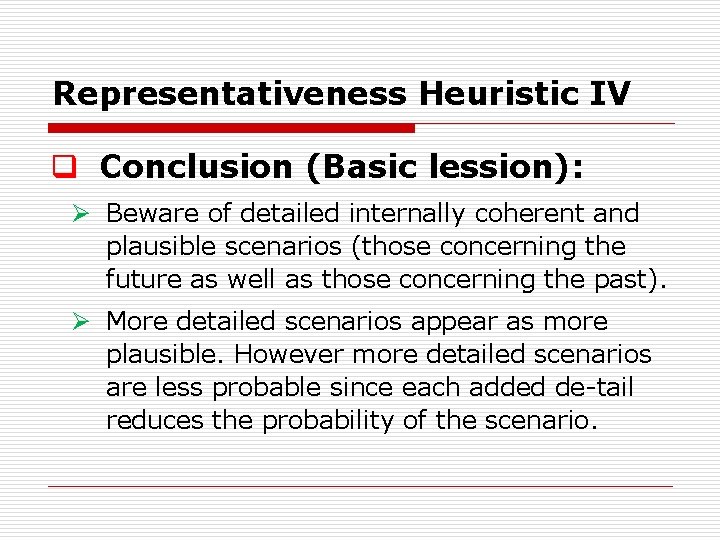

Representativeness Heuristic IV q Conclusion (Basic lession): Ø Beware of detailed internally coherent and plausible scenarios (those concerning the future as well as those concerning the past). Ø More detailed scenarios appear as more plausible. However more detailed scenarios are less probable since each added de tail reduces the probability of the scenario.

Probability Judgments: Probability Matching q Basic phenomenon: 70% 30% q Peoples’ answers reflect probabilities

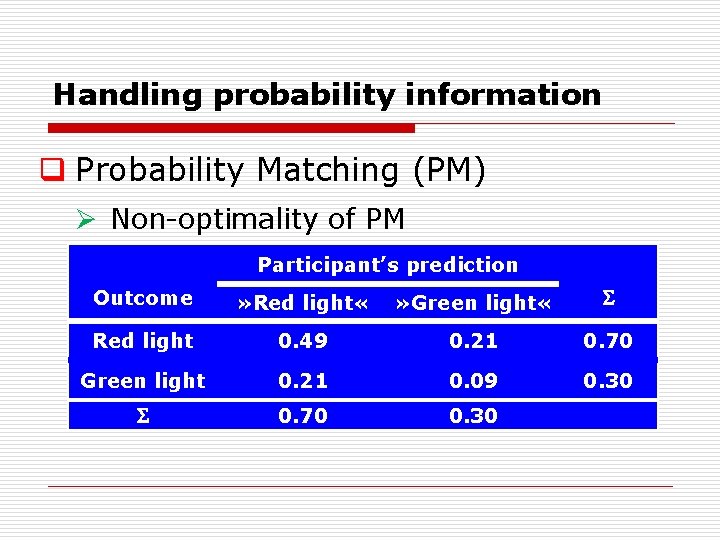

Handling probability information q Probability Matching (PM) Ø Non optimality of PM Participant’s prediction Outcome » Red light « » Green light « Red light 0. 49 0. 21 0. 70 Green light 0. 21 0. 09 0. 30 0. 70 0. 30

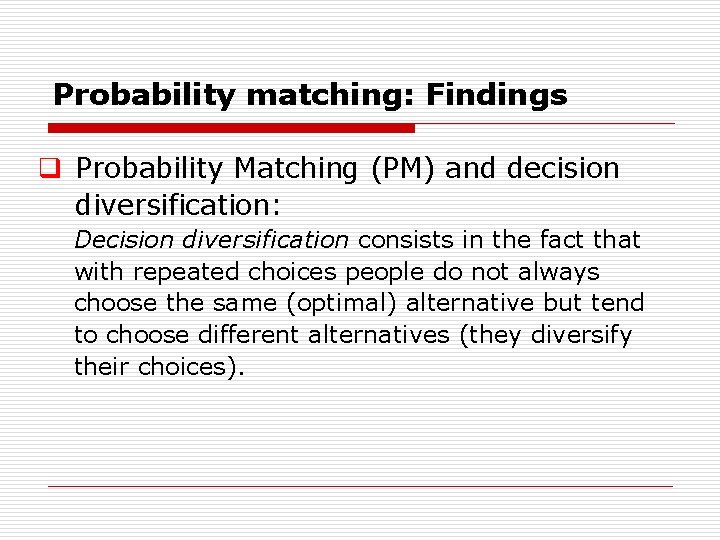

Probability matching: Findings q Probability Matching (PM) and decision diversification: Decision diversification consists in the fact that with repeated choices people do not always choose the same (optimal) alternative but tend to choose different alternatives (they diversify their choices).

Probability matching: Findings q Rubinstein (2002): A deck of 100 cards composed as follows: Ø 36 cards are green (G) Ø 25 cards are blue (B) Ø 22 cards are yellow (Y) Ø 17 cards are red (R) [original: brown] 5 cards are drawn at random and put into 5 separate en velopes A, B, C, D, E. Imagine that you receive a price for predicting the correct color of the card in each envelope. What would you pre dict for the different envelopes?

Probability matching: Findings q Rubinstein (2002): Results: Ø 42% (Study 1) and 38% (Study 2) of the participants made the optimal prediction: Green for each of the 5 envelopes. Ø All other participants used a diversification strategy. Ø About 30% of the participants used PM (about 50% of par ticipants who diversified).

Probability matching: Findings q Probability Matching (PM) and the search for patterns: Various authors argued that PM might indicate peoples’ attempt to search for patterns. An experiment of Gaissmaier & Schooler (2008) provides some evidence in favor of this explanation.

Probability matching: Findings q Gaissmaier & Schooler (2008): They presented participants with two sequen ces: Ø The first one was a purely random sequence comprising 288 trials with two possible events: A red square (R) with p = 2/3 and a green square (G) with p = 1/3. Ø The second sequence also comprised 288 trials. However, for this sequence the fixed pattern RRGRGRRRGGRR (12 events) was repeated 24 times.

Probability matching: Findings q Gaissmaier & Schooler (2008): Results: Ø People performing probability matching in the first phase were more likely to detect the pattern in the second phase. Ø Thus, it may be concluded that PM is an indication of peoples’ attempts to search for patterns. Ø Problems with this explanation: 1. No applicable to the results of Rubinstein. 2. If explained to them, people understand that PM is suboptimal (Koehler & James, 2008).

Probability matching: Findings q Probability Matching (PM) also found in wild living animals q Example 1: tits (Meisen, Mésanges): Ø Ø Ø The birds were allowed to hunt in different places with exact rates of yield. The hunting periods were short enough so that there was no significant reduction of yield in different regions. One might expect that the birds (following to an initi al exploration phase) would remain permanently within the region with the greatest rate of yield. The time of residence of the animals in different regions reflected approximately the relative rate of yield of the region.

Probability matching: Findings q Example 2: wild ducks: Ø Armed with bags containing pieces of bred of 2 g each, two experimenters went to the pond on several consecutive days. They positioned themselves 20 meters apart and started to throw the pieces of bred into the water. Ø The relative rate of throwing of the two experimenters was determined randomly so that it could not be predicted. Ø At the beginning of the experiment the wild ducks gathered in front of the two throwers where the duration of their residence corresponded approximately to the last rate of throwing.

Probability matching: Findings q Example 2: wild ducks: Ø Ø Ø Within 1 minute (during this time about 12 to 18 pieces have been thrown into the water and most ducks had not yet received a piece of bred) the ducks changed their positions in such a way that the relative duration of their stay reflected the actual rate of throwing. In some trials at the end the pieces of bred were thrown with equal rate of throwing. However, the pieces of one thrower were double the size of the other one. In this case the ducks first distributed themselves evenly over the two throwers. However after about 5 6 minutes they adjusted their distribution thus reflecting the product of size and rate of throwing.

Probability matching: Findings q Probability Matching (PM): Individual differences: Ø Intelligence and PM: People using the optimal strategy exhibited on average a higher cognitive capability (as measured be the SAT [Scholastic Aptitude Test]) compared to persons employing the strategy of probability matching. Ø Gender differences: Women engage more in PM than males.

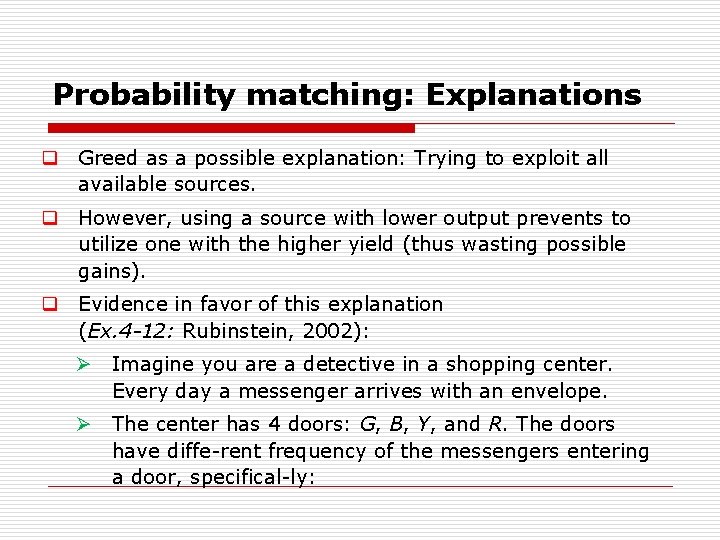

Probability matching: Explanations q Greed as a possible explanation: Trying to exploit all available sources. q However, using a source with lower output prevents to utilize one with the higher yield (thus wasting possible gains). q Evidence in favor of this explanation (Ex. 4 12: Rubinstein, 2002): Ø Imagine you are a detective in a shopping center. Every day a messenger arrives with an envelope. Ø The center has 4 doors: G, B, Y, and R. The doors have diffe rent frequency of the messengers entering a door, specifical ly:

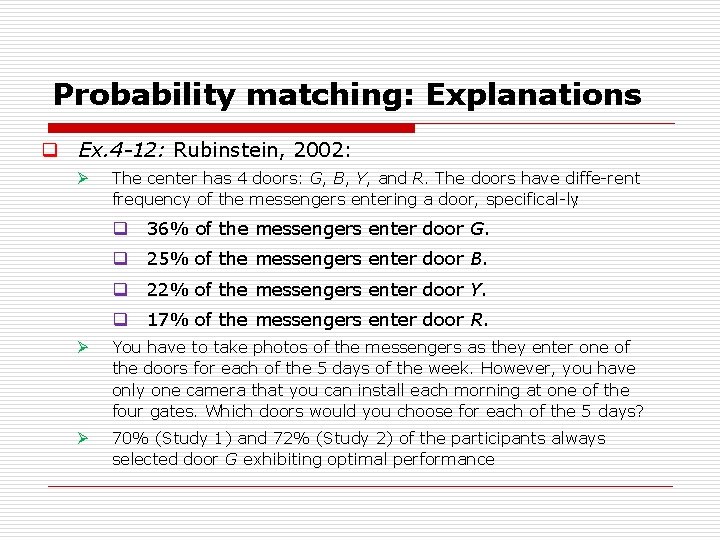

Probability matching: Explanations q Ex. 4 12: Rubinstein, 2002: Ø The center has 4 doors: G, B, Y, and R. The doors have diffe rent frequency of the messengers entering a door, specifical ly: q 36% of the messengers enter door G. q 25% of the messengers enter door B. q 22% of the messengers enter door Y. q 17% of the messengers enter door R. Ø You have to take photos of the messengers as they enter one of the doors for each of the 5 days of the week. However, you have only one camera that you can install each morning at one of the four gates. Which doors would you choose for each of the 5 days? Ø 70% (Study 1) and 72% (Study 2) of the participants always selected door G exhibiting optimal performance

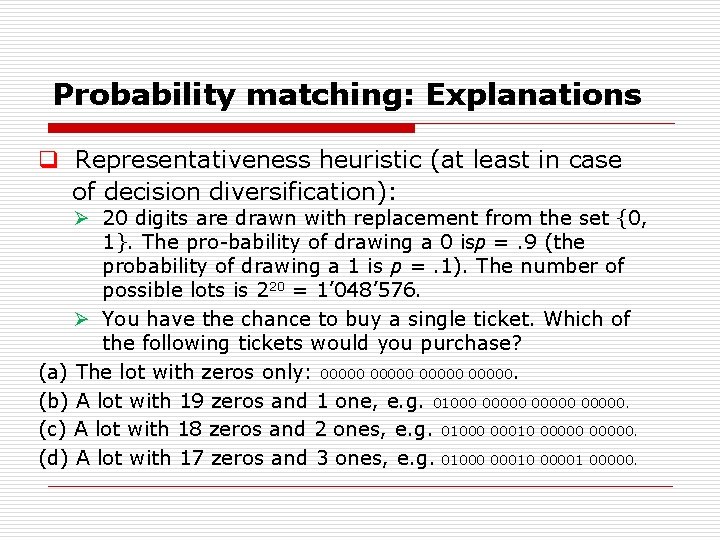

Probability matching: Explanations q Representativeness heuristic (at least in case of decision diversification): Ø 20 digits are drawn with replacement from the set {0, 1}. The pro bability of drawing a 0 isp =. 9 (the probability of drawing a 1 is p =. 1). The number of possible lots is 220 = 1’ 048’ 576. Ø You have the chance to buy a single ticket. Which of the following tickets would you purchase? (a) The lot with zeros only: 00000. (b) A lot with 19 zeros and 1 one, e. g. 01000 00000. (c) A lot with 18 zeros and 2 ones, e. g. 01000 00010 00000. (d) A lot with 17 zeros and 3 ones, e. g. 01000 00010 00001 00000.

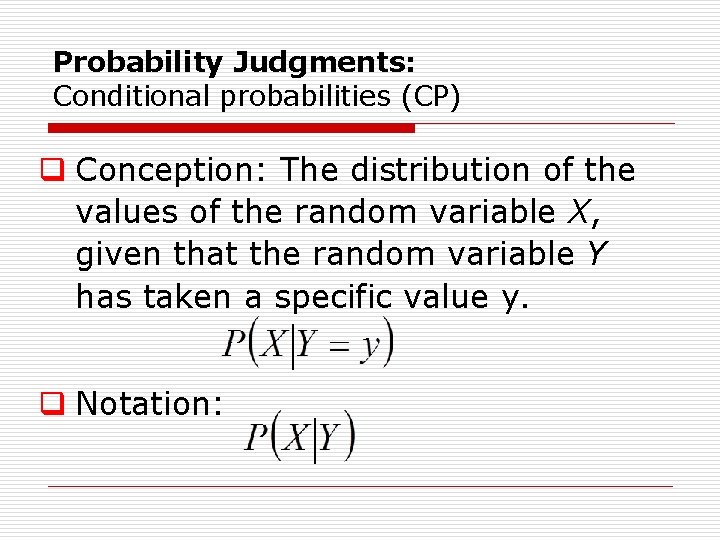

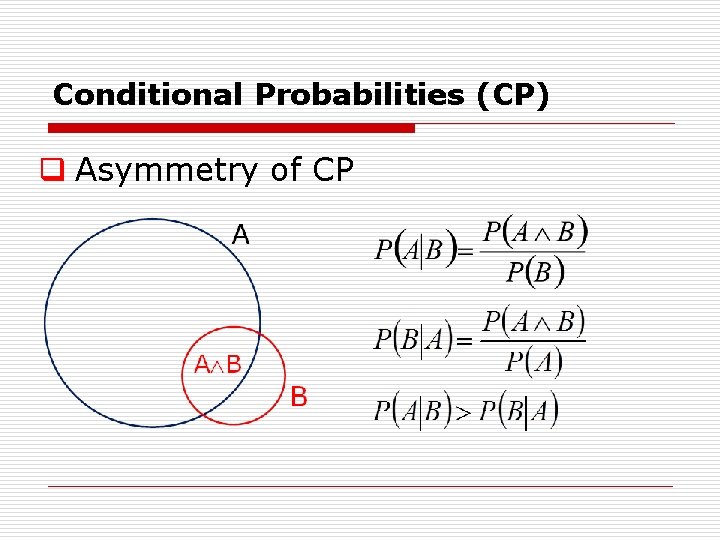

Probability Judgments: Conditional probabilities (CP) q Conception: The distribution of the values of the random variable X, given that the random variable Y has taken a specific value y. q Notation:

Conditional Probabilities (CP) q Asymmetry of CP

Conditional Probabilities (CP) q Contingency tables:

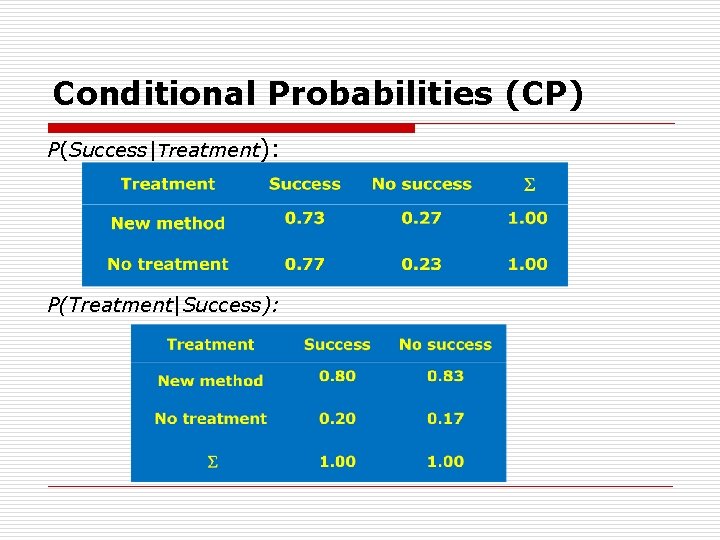

Conditional Probabilities (CP) P(Success|Treatment): P(Treatment|Success):

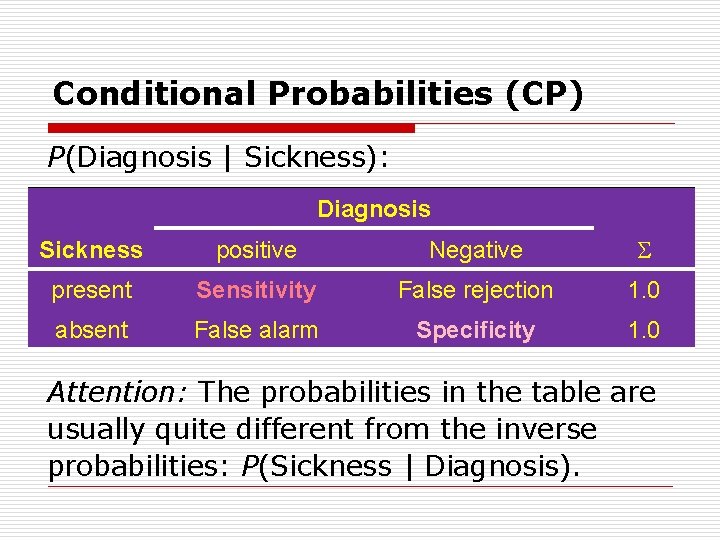

Conditional Probabilities (CP) P(Diagnosis | Sickness): Diagnosis Sickness positive Negative present Sensitivity False rejection 1. 0 absent False alarm Specificity 1. 0 Attention: The probabilities in the table are usually quite different from the inverse probabilities: P(Sickness | Diagnosis).

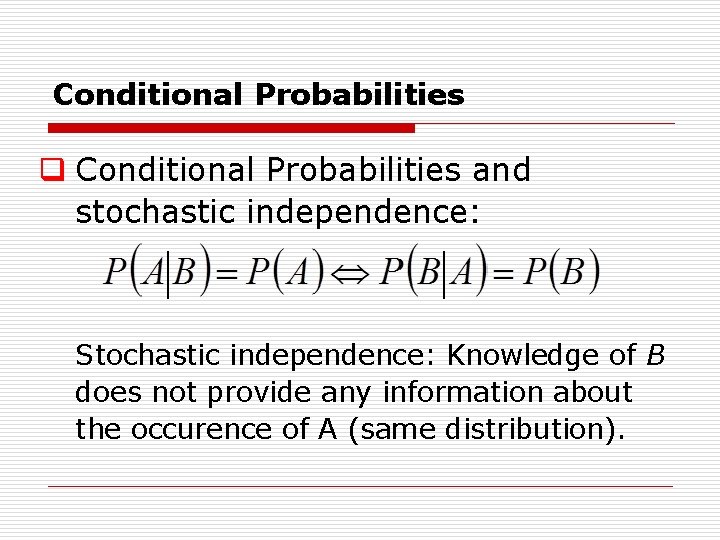

Conditional Probabilities q Conditional Probabilities and stochastic independence: Stochastic independence: Knowledge of B does not provide any information about the occurence of A (same distribution).

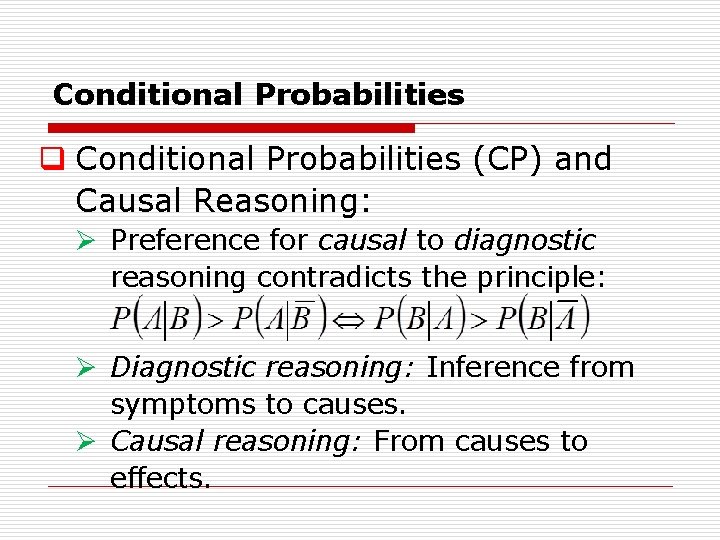

Conditional Probabilities q Conditional Probabilities (CP) and Causal Reasoning: Ø Preference for causal to diagnostic reasoning contradicts the principle: Ø Diagnostic reasoning: Inference from symptoms to causes. Ø Causal reasoning: From causes to effects.

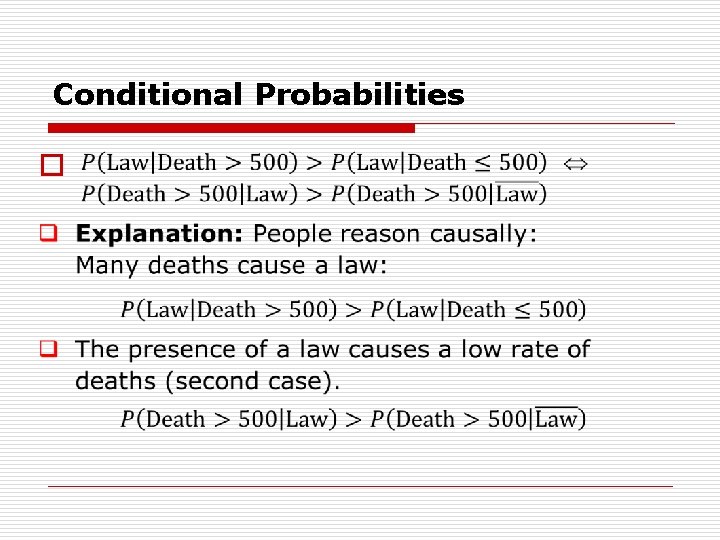

Conditional Probabilities q Problem A: Which of the following probabilities is higher? Ø The probability that, within the next five years, Con gress will pass a law to curb mercury pollution, if the number of deaths attributed to mercury poisoning dur ing the next five years exceeds 500. Ø The probability that, within the next five years, Con gress will pass a law to curb mercury pollution, if the number of deaths attributed to mercury poisoning dur ing the next five years does not exceed 500. q 140 of 166 subjects chose the first alternative.

Conditional Probabilities q Problem B: Which of the following probabilities is higher? Ø The probability that the number of death attributed to mercury poisoning during the next five years will ex ceed 500, if Congress passes a law within the next five years to curb mercury pollution. Ø The probability that the number of death attributed to mercury poisoning during the next five years will exceed 500, if Congress does not pass a law within the next five years to curb mercury pollution. q Most subjects chose the second alternative.

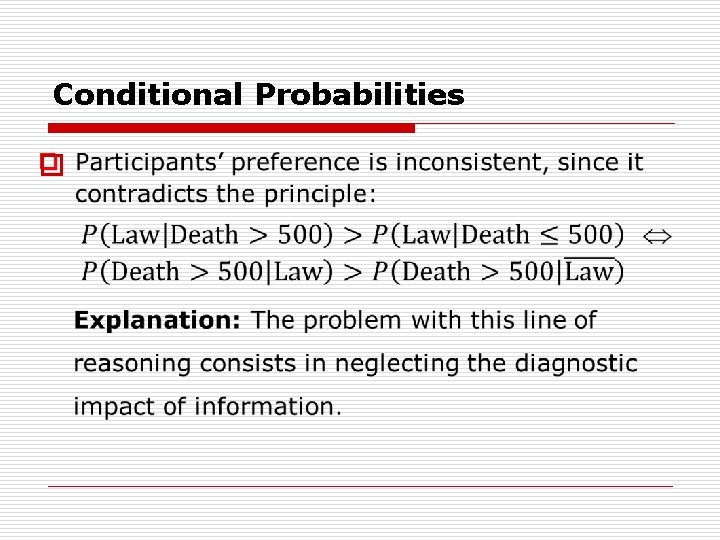

Conditional Probabilities o

Conditional Probabilities o

Conditional Probabilities o

Conditional probabilities q Principle lessions: Ø There exists a principle difference between human reasoning and the results of the probability calculus. Ø People prefer causal reasoning to diagnostic. Ø Probability calculus: Neither the causal direction nor time is relevant. Only the degree of stochastic dependency counts.

Conditional probabilities q Principle lessions: Ø Peoples’ error constists in the fact that different causes are used in the two problems (the same events play different roles in the two problems): Problem A: Death rate as a cause of the congress passing a law. Problem B: Presence of a law as a cause of the (low) death rate.

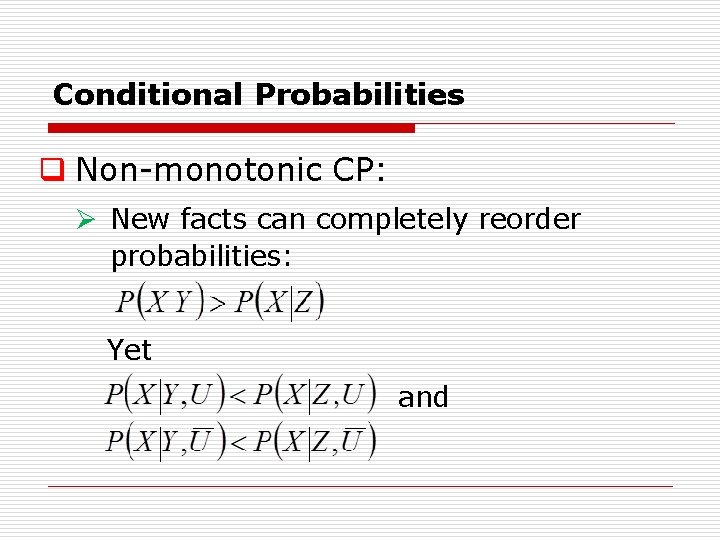

Conditional Probabilities q Non monotonic CP: Ø New facts can completely reorder probabilities: Yet and

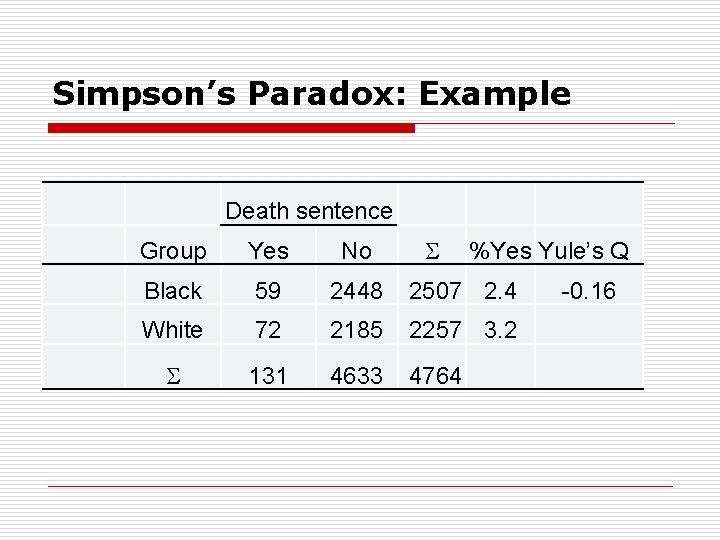

Simpson’s Paradox: Example Death sentence Group Yes No %Yes Yule’s Q Black 59 2448 2507 2. 4 White 72 2185 2257 3. 2 131 4633 4764 -0. 16

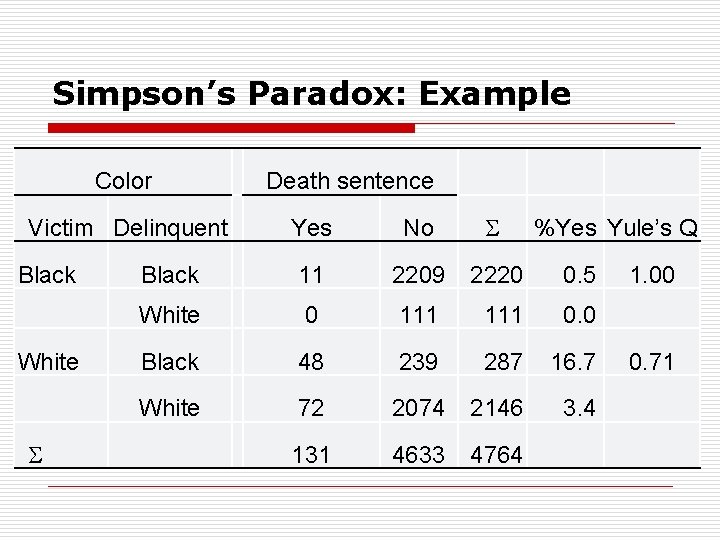

Simpson’s Paradox: Example Color Yes No Black 11 2209 2220 0. 5 White 0 111 0. 0 Black 48 239 287 16. 7 White 72 2074 2146 3. 4 131 4633 4764 Victim Delinquent Black White Death sentence %Yes Yule’s Q 1. 00 0. 71

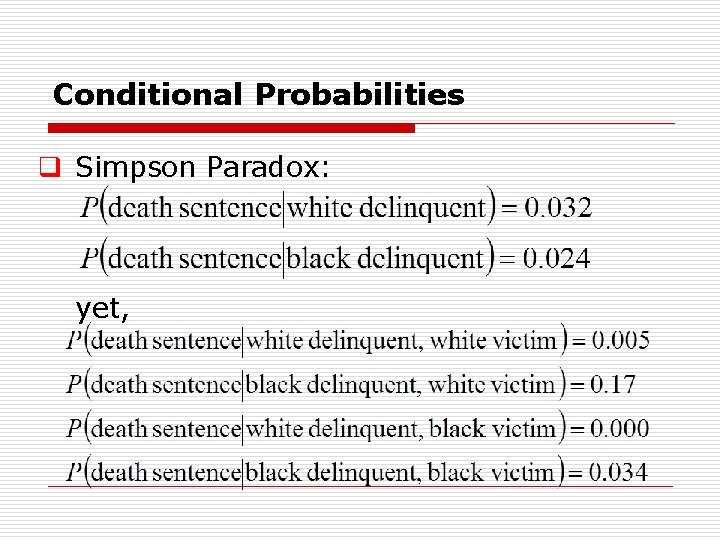

Conditional Probabilities q Simpson Paradox: yet,

Base rates q Ignoring base rates Ø What is base rate information? Ø Example: Base rate neglect. Ø Causal base rates.

Base rates q What are base rates? Ø Probabilities (distribution of) a feature within a specific population (reference class). Ø Examples: Proportion of women within the world’s population. Proportion of people with symtoms of depression within the Swiss population.

Base rates q Base rate neglect: Empirical result: Ø People ignore the information due to base rates in the presence of (more) diagnostic information.

Base rates q Example: Jack is a 45 year old man. He is married and has four children. He is generally conservative, careful, and ambitious. He shows no interest in political and social issues and spends most of his free time on his many hobbies which include home carpentry, sailing, and mathematical puzzles. Question: The probability that Jack is one of 30 (70) engineers in the sample of 100 is _______%. (Either 30 or 70 out of 100 persons were engineers or lawers)

Base rates q Results: Ø The base rate information (30/100 or 70/100) had practically no effect on peoples’ judgments. Ø With the null description base rates are taken into account: Suppose now that you are given no information whatsoever about an individual chosen at random from the sample. The probability that the man is one of 30 (70) engineers in the sample of 100 is _______%.

Base rates q Results: Ø With a perfect non diagnostic description base rates are ignored: Dick is a 30 year old man. He is married with no child ren. A man of high ability and motivation, he promises to be quite successful in his field. He is well liked by his colleagues. Ø People estimates were about 50% in both groups (30/70 vs. 70/30).

Base rates q Conclusion: In the presence of more specific information (either diagnostic or not) base rates are simply ignored.

Base rates q Causal Base Rates: The base rates are associated with a causal factor that is also relevant for the target event.

Base rates q Causal Base Rates: Example: Two descriptions: Ø Two years, ago a final exam war given in a course at Yale University. About 75% of the students failed (passed) the exam. Ø Two years ago, a final exam was given in a course at Yale University. An educational psychologist interested in scholastic achievements interviewed a large number of students who had taken the course. Since he was primarily concerned with reactions to success (failure), he selected mostly students who had passed (failed) the exam. Specifically, about 75% of the students in his sample had passed (failed) the exam.

Base rates q Causal Base Rates: Explanation Ø The first description indicates a causal factor: the difficulty of the exam (with a success rate of 75% the exam seems to be easy compared to a success rate of 25%). Ø No such indication is given by the second description.

Base rates q Causal Base Rates: Results The judged probability of a success in the exam of a target person with a specific academic ability (shortly described to participants) was quite different for the two descriptions: q With the first description: The (causal) base rates were taken into account. q With the second description base rates were ignored: The academic ability was the main factor for the decision.

Dual Process Theories and the CRT q Dual process theories of cognition: Existence of two processes of reasoning: 1. Intuitive: Quick, effortless, unconscious, error loaden 2. Reflective: Slow, effortful, conscious, correct ing for errors.

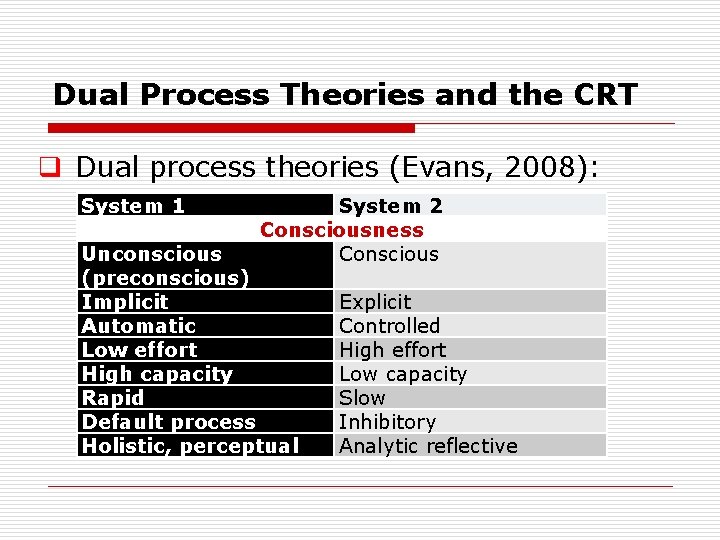

Dual Process Theories and the CRT q Dual process theories (Evans, 2008): System 1 System 2 Consciousness Conscious Unconscious (preconscious) Implicit Automatic Low effort High capacity Rapid Default process Holistic, perceptual Explicit Controlled High effort Low capacity Slow Inhibitory Analytic reflective

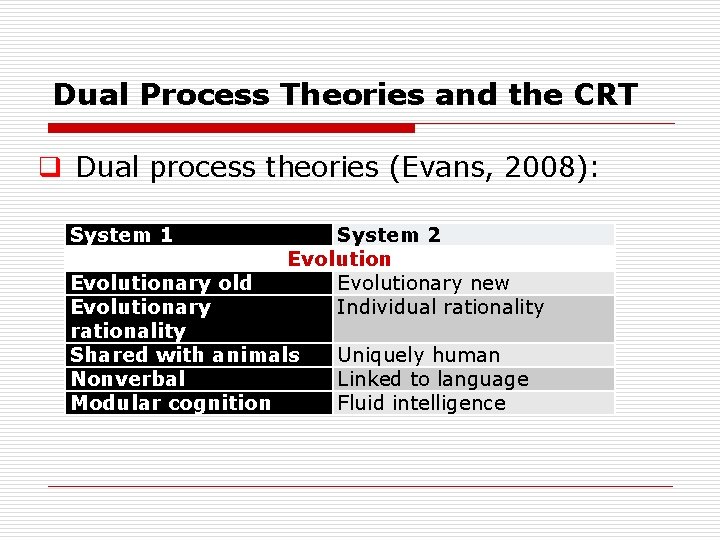

Dual Process Theories and the CRT q Dual process theories (Evans, 2008): System 1 System 2 Evolutionary new Individual rationality Evolutionary old Evolutionary rationality Shared with animals Nonverbal Modular cognition Uniquely human Linked to language Fluid intelligence

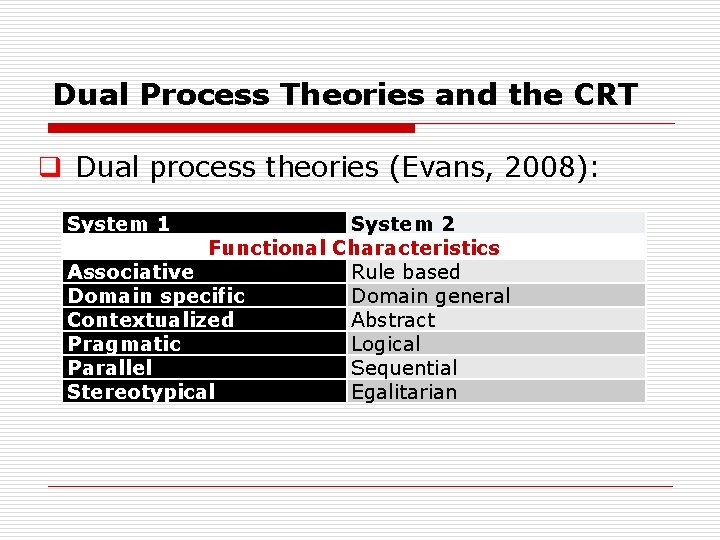

Dual Process Theories and the CRT q Dual process theories (Evans, 2008): System 1 System 2 Functional Characteristics Associative Rule based Domain specific Domain general Contextualized Abstract Pragmatic Logical Parallel Sequential Stereotypical Egalitarian

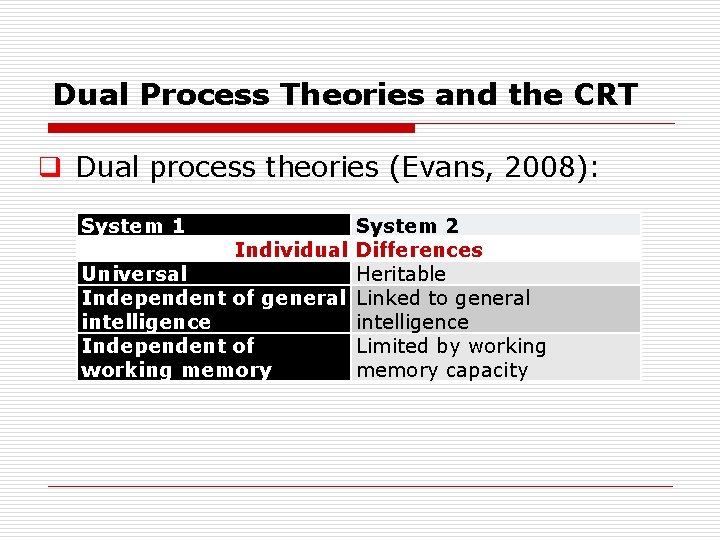

Dual Process Theories and the CRT q Dual process theories (Evans, 2008): System 1 System 2 Individual Differences Universal Heritable Independent of general Linked to general intelligence Independent of Limited by working memory capacity

Dual Process Theories and the CRT q Dual process theories: Application to judgment and decision biases: Ø Judgmental errors are due to System 1 processes that are not corrected by System 2 processes. Ø Example: Linda Problem: System 1 process = comparison by similarity. System 2 process = checking for set inclusion.

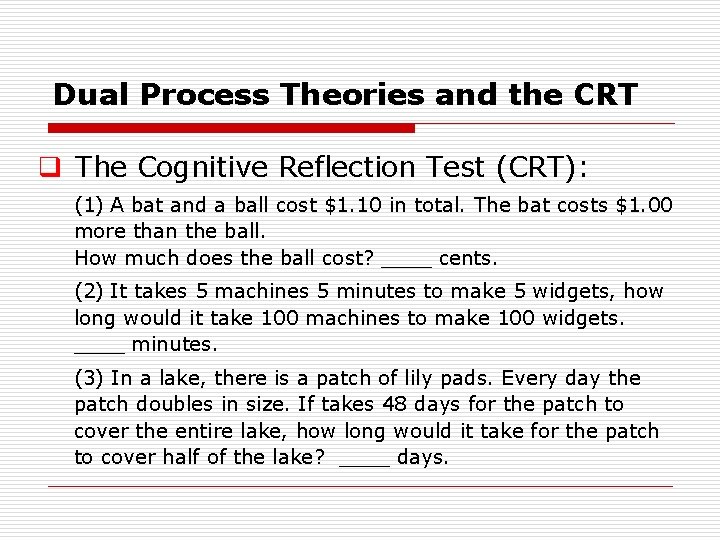

Dual Process Theories and the CRT q The Cognitive Reflection Test (CRT): (1) A bat and a ball cost $1. 10 in total. The bat costs $1. 00 more than the ball. How much does the ball cost? ____ cents. (2) It takes 5 machines 5 minutes to make 5 widgets, how long would it take 100 machines to make 100 widgets. ____ minutes. (3) In a lake, there is a patch of lily pads. Every day the patch doubles in size. If takes 48 days for the patch to cover the entire lake, how long would it take for the patch to cover half of the lake? ____ days.

Dual Process Theories and the CRT q The Cognitive Reflection Test (CRT): Basic idea: Ø Items elicit a wrong intuitive response that comes to mind immediately. Ø Humans are cognitive misers: They spend as little effort as possible. Thus they do not in voke effortful processing (System 2) to correct for the error.

Dual Process Theories and the CRT q The Cognitive Reflection Test (CRT): Results (Frederick, 2005; Toplak et al. , 2011): Ø Delay of gratification for short time horizons. Ø Higher willingness to take risks. Ø Gender difference. Ø Explains cognitive biases better than measures of intelligence. Ø Incremental predictive validity.

Dual Process Theories and the CRT q Criticism: Three types of criticism 1. Missing accordance concerning the characteristics. 2. Different modes of automatic processing. 3. Explanative power of dual processing theories for explaining judgment and decision biases.

Dual Process Theories and the CRT q Criticism 1: Missing accordance There is an accord concerning the following pairs of features for characterizing different forms of processing (e. g. Schneider & Shiffrin, 1977): Rapid – Slow Automatic – Controlled Low effort – high effort Low consciousness – high consciousness

Dual Process Theories and the CRT q Criticism 1: Missing accordance Other dichotomies are however more question able: For example, the assumption that System 1 processing is associative and System 2 processing rule based. This contradicts the fact that language proces sing is rule based and nevertheless fast, automatic and with little consciousness. Also the assumption that System 2 processing is only due to humans is problematic.

Dual Process Theories and the CRT q Criticism 2: Different forms of automatic processing The distinction between System 1 and 2 proces sing blurs the distinction between two types of automatic processing: 1. Processing of specialized modules, like visual processing. 2. Skilled performance. Both types share the focal features of System 1 processing: fast, effortless, automatic, opaque.

Dual Process Theories and the CRT q Criticism 2: Different forms of automatic processing The two types of automatic processing however differ with respect to knowledge: 1. Processing by specialized modules are completely encapsulated (» hard wired «) and immune to knowledge (e. g. , visual illusions). 2. Skilled performance is not » hard wired « and may be influenced by knowledge.

Dual Process Theories and the CRT q Criticism 2: Different forms of automatic processing Evans (2008) proposes to draw the distinction between System 1 and System 2 processing according to whether processes require working memory and are thus q effortful (requires cognitive resources), q limited by the capacity of working memory, q under conscious control.

Dual Process Theories and the CRT q Criticism 3: Explanatory power Structure of two systems explanations: Judgmental biases are due to System 1 mode of processing taking control with no corrective intervention of System 2 mode processing. Questions: q Is this a reasonable type of explanation? q Does this type of explanation add anything to existing explanations?

Dual Process Theories and the CRT q Criticism 3: Explanatory power Structure of a good explanation of judgmental errors: Consist of two parts: q Task analysis: Characterization of the problem to be solved. q Representation of the problem by the reasoning person and her strategies for solving the problem.

Dual Process Theories and the CRT q Criticism 3: Explanatory power Contribution of two process theories: If the two system approach should have any explanatory power then it must be shown: q System 1 mode of processing is associated with a different conceptualization of the problem compared to System 2 mode of processing. q This difference causes the observed error or bias.

Dual Process Theories and the CRT q Criticism 3: Explanatory power Example 1: Linda Problem: q The task consists in predicting the profession and personal characteristics of Linda using the cues presented in the short description of Linda. q An important aspect consists in checking for relations between sets, specifically, that the set of bank tellers that are active in the feminist movement is included in the set of bank tellers.

Dual Process Theories and the CRT q Criticism 3: Explanatory power Example 1: Linda Problem: q Results indicate that the relationship between different sets is not part of participants’ representation of the problem. q They predominately solve the problem by comparing the description of Linda with the des cription of the different jobs assigning ranks according to how closely the two fit together due to their subjective theories.

Dual Process Theories and the CRT q Criticism 3: Explanatory power Example 1: Linda Problem: To apply the two systems approach one has to assume that the similarity judgment (or the judgment by representativeness) is a System 1 mode of processing whereas assessing set inclusion has to be characterized as a System 2 mode of processing.

Dual Process Theories and the CRT q Criticism 3: Explanatory power Example 1: Linda Problem: q This assignment is completely arbitrary since it is questionable whether the deliberate consideration of personal characteristics for judging the profession of Linda requires less cognitive resources than checking for set inclusion. q This type of explanation does not contribute anything to our un derstandingof the error. It rather obscures the original explanation since it is less specific and more questionable.

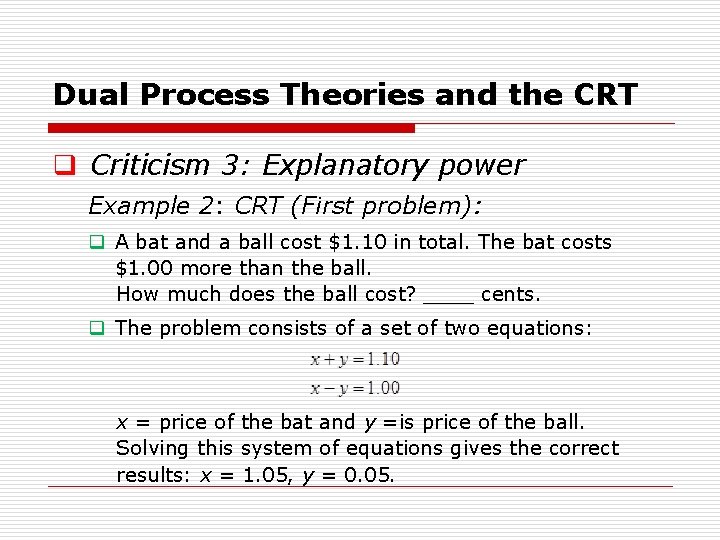

Dual Process Theories and the CRT q Criticism 3: Explanatory power Example 2: CRT (First problem): q A bat and a ball cost $1. 10 in total. The bat costs $1. 00 more than the ball. How much does the ball cost? ____ cents. q The problem consists of a set of two equations: x = price of the bat and y =is price of the ball. Solving this system of equations gives the correct results: x = 1. 05, y = 0. 05.

Dual Process Theories and the CRT o

Dual Process Theories and the CRT q Criticism 3: Explanatory power Example 2: CRT (First problem): This may be due to the fact that: q The objective given by the task description (that the bat has to be 1 Dollar more than the bat) is simply ignored, or q They do not want to spend further effort because of the intuitive appeal of the first solution that comes to mind. q Thus it might be argued that the high plausibility of the first solution that comes to mind prevents a more detailed examination of the problem.

Dual Process Theories and the CRT q Criticism 3: Explanatory power Example 2: CRT (First problem): q A two system’s explanation of participants’ failure to solve the task meets a similar problem as for the Linda problem: It is unreasonable that the processes resulting in an erroneous solution are automatic and require no or less cognitive resources than checking whether the dif ference between assumed prices for the bat and the ball is really 1. 00 Dollar. q In summary, the two examples presented do not reveal any significant contribution of the two system’s approach to our understanding of cognitive biases and judgmental errors.

- Slides: 98