Probability Certainty Intro Overview History of probability theory

Probability & Certainty: Intro

Overview • History of probability theory • Some basic probability theory – Calculating simple probabilities – Combining mutually-exclusive probabilities – Combining independent probabilities – More complex probabilities – Calculating conditional probabilities • Bayes’ Theorem, and why we should care about it • A test case: The ‘Let’s Make A Deal!’ problem Probability & Certainty: Intro

History of probability theory • Compress all of human history (350 K years) in one 24 hour day: – the first recorded general problem representation (geometry, invented by Thales of Miletus about 450 B. C. ) would have appeared only 9 minutes and 30 seconds ago – the first systematic large-scale collection of empirical facts (Tycho Brahe’s collection of astronomical observations) would have appeared only a minute and a half ago – the first mathematical equation which was able to predict an empirical phenomena (Newton’s 1697 equation for planetary motion) would have appeared only one minute and twelve seconds ago – Probability theory appeared between 1654 (a minute and a half ago) and 1843 (34 seconds ago). Probability & Certainty: Intro

History of probability theory • The emergence of elementary probability theory in the 1650 s met with enormous resistance and lack of comprehension when it was first introduced, despite its formal character, its utility, and (what we now recognize as) its simplicity. • The difficult points (Margolis, 1993) were philosophical rather than mathematical: the notions that one could count possibilities that had never actually existed, and that order could be obtained from randomness. Probability & Certainty: Intro

Basic probability theory: Example 1 • A boring standard example: How likely is it that we will throw a 6 with one dice? • Basic principle: The probability of any particular event is equal to the ratio of the number of ways the event can happen over the number of ways anything can happen (= the number of ways the event can fail to happen + the number of ways it can happen). Probability & Certainty: Intro

Basic probability theory: Example 2 How likely is it that we will throw a 7 with two die? • There is more than one way for the event to happen: 6 + 1, 1+6, 5 + 2, 2+5, 3 + 4, 4 + 3 = 6 ways • There are 36 (6 x 6) ways for anything to happen • So the probability of 7 with two die is 6/36 or 1/6. Probability & Certainty: Intro

Basic probability theory: Example 3 We roll the die 4 times, and never get a seven. What is the probability that we’ll get on the 5 th roll? • Independent events are events that don’t effect each other’s probability. Since the every roll is independent of every other, the odds are still 1/6. Probability & Certainty: Intro

Basic probability theory: Example 4 We roll the die twice and get a seven both times. What is the probability of that? • To combine probabilities of independent events, multiply the odds of each event. The odds of each 7 are 1/6, so the odds of two rolls of 7 in a row are 1/6 x 1/6 = 1/36. Probability & Certainty: Intro

Basic probability theory: Example 5 We roll the die. What are the odds are getting either a 7 or a 2? • Now the events are mutually exclusive: if one happens, the other cannot. To combine probabilities of mutually exclusive events, add them together. • 6/36 [odds of 7] + 1/36 [odds of 2] = 7/36 Probability & Certainty: Intro

Basic probability theory: Example 6. 1 We roll the die twice. What are the odds that we get at least one 7 from the two rolls? • Can we just add the probabilities of getting a 7 on each roll? • No: because the events are not mutually exclusive anymore • if we could, we’d be above 100%- guaranteed a 7 after 6 rolls! Where could the guarantee come from? Probability & Certainty: Intro

Basic probability theory: Example 6. 2 We roll the die twice. What are the odds that we get at least one 7 from the two rolls? • Can we just multiply the probabilities of getting a 7 on each roll? • No: because the events are not independent (Why not? ) • And 1/6 x 1/6 is less than 1/6 - so we’d have smaller chance with two rolls than with one! Probability & Certainty: Intro

Basic probability theory: Example 6. 3 We roll the die twice. What are the odds that we get at least one 7 from the two rolls? • We can turn part of the problem into a problem of mutual exclusivity by asking: what are the odds of there being exactly one seven out of two rolls? • one way is to roll 7 first, but not second - the odds of this are 1/6 * 5/6 (independent events) = 0. 138 - the odds of rolling 7 second are 5/6 * 1/6 (independent events) = 0. 138 - since these two outcomes are mutually exclusive, we can add them to get 0. 138 + 0. 138 = 0. 277 Probability & Certainty: Intro

Basic probability theory: Example 6. 4 We roll the die twice. What are the odds that we get at least one 7 from the two rolls? • Now we need to know: what are the odds of there being two sevens out of two rolls? • We already know: it’s 1/36 = 0. 03 • So: the odds that we get at least one 7 is the odds of two 7 s + the odds of one 7 (mutually exclusive events) = 0. 03 + 0. 27 = 0. 3 Probability & Certainty: Intro

Basic probability theory: The generalization • Does anyone know how to generalize this calculation, so we can easily calculate the odds of an event of probability p happening r times out of n tries, for any values of p, r, and n? • The binomial theorem: Tune in for the exciting next class! Probability & Certainty: Intro

Basic probability theory: Conditional probability • What if a dice is biased so that it rolls 6 twice as often as every other number? How can we deal with ‘uneven’ base rates? • Why should we care? – Because real life uses biased dice – eg. the conditional probability of being schizophrenic, given that a person has an appointment with a doctor who specializes in schizophrenia, is quite different from the unconditional probability that a person has schizophrenia (the base rate) Probability & Certainty: Intro

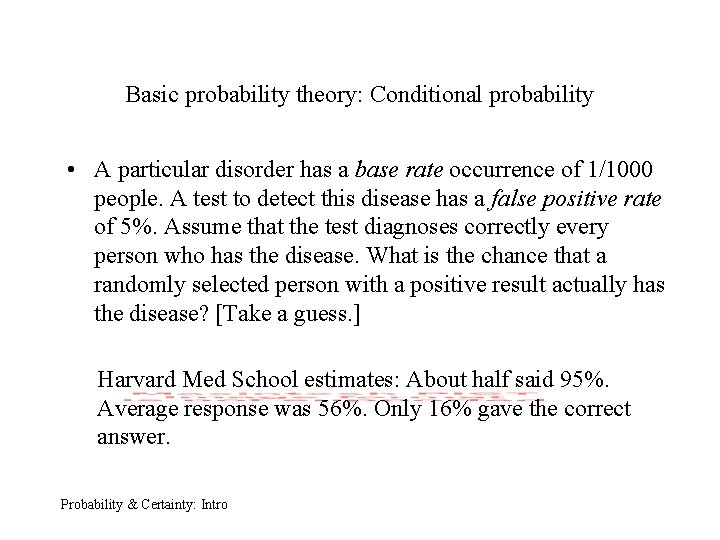

Basic probability theory: Conditional probability • A particular disorder has a base rate occurrence of 1/1000 people. A test to detect this disease has a false positive rate of 5%. Assume that the test diagnoses correctly every person who has the disease. What is the chance that a randomly selected person with a positive result actually has the disease? [Take a guess. ] Harvard Med School estimates: About half said 95%. Average response was 56%. Only 16% gave the correct answer. Probability & Certainty: Intro

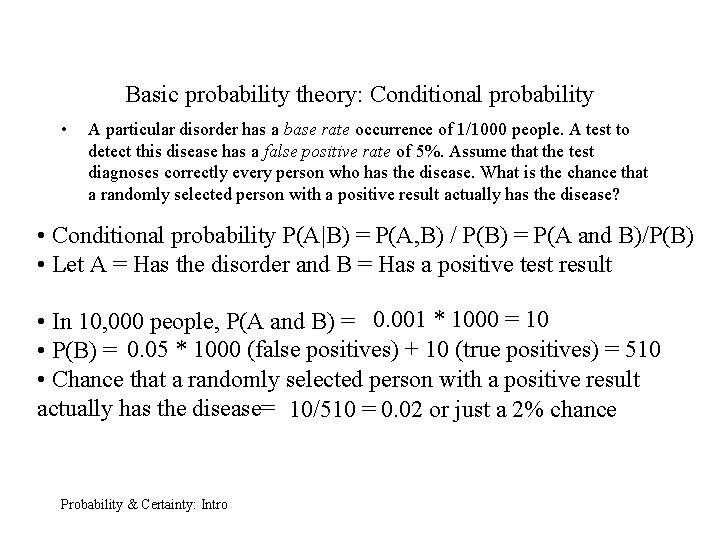

Basic probability theory: Conditional probability • A particular disorder has a base rate occurrence of 1/1000 people. A test to detect this disease has a false positive rate of 5%. Assume that the test diagnoses correctly every person who has the disease. What is the chance that a randomly selected person with a positive result actually has the disease? • Conditional probability P(A|B) = P(A, B) / P(B) = P(A and B)/P(B) • Let A = Has the disorder and B = Has a positive test result • In 10, 000 people, P(A and B) = 0. 001 * 1000 = 10 • P(B) = 0. 05 * 1000 (false positives) + 10 (true positives) = 510 • Chance that a randomly selected person with a positive result actually has the disease= 10/510 = 0. 02 or just a 2% chance Probability & Certainty: Intro

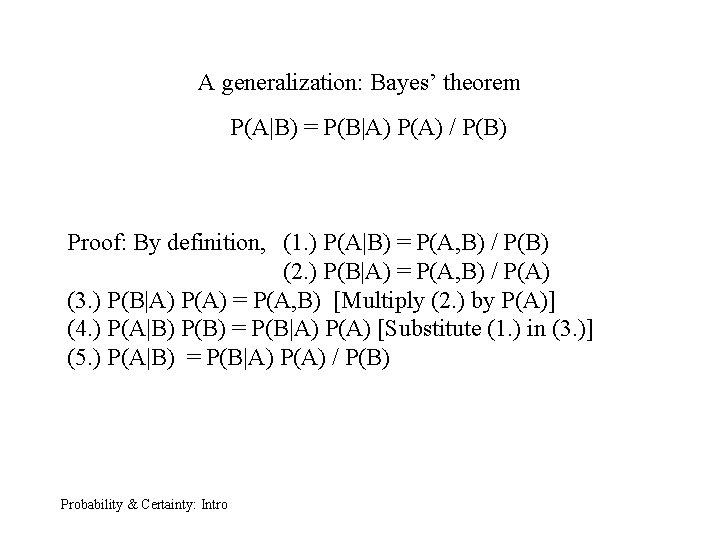

A generalization: Bayes’ theorem P(A|B) = P(B|A) P(A) / P(B) Proof: By definition, (1. ) P(A|B) = P(A, B) / P(B) (2. ) P(B|A) = P(A, B) / P(A) (3. ) P(B|A) P(A) = P(A, B) [Multiply (2. ) by P(A)] (4. ) P(A|B) P(B) = P(B|A) P(A) [Substitute (1. ) in (3. )] (5. ) P(A|B) = P(B|A) P(A) / P(B) Probability & Certainty: Intro

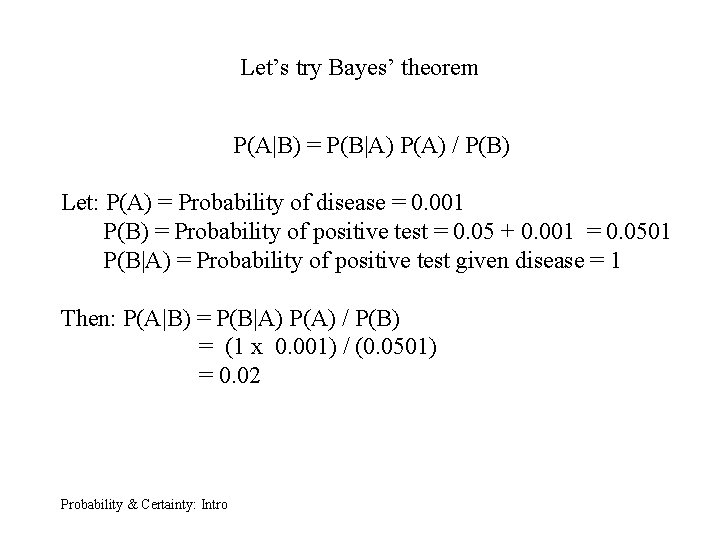

Let’s try Bayes’ theorem P(A|B) = P(B|A) P(A) / P(B) Let: P(A) = Probability of disease = 0. 001 P(B) = Probability of positive test = 0. 05 + 0. 001 = 0. 0501 P(B|A) = Probability of positive test given disease = 1 Then: P(A|B) = P(B|A) P(A) / P(B) = (1 x 0. 001) / (0. 0501) = 0. 02 Probability & Certainty: Intro

The Notorious 3 -Curtain (‘Let’s Make A Deal’) Problem! • • Three curtains hide prizes. One is good. Two are not. You choose a curtain. The MC opens another curtain. It’s not good. He gives you the chance to stay with our first choice, or switch to the remaining unopened curtain. • Should you stay or switch, or does it matter? Probability & Certainty: Intro

P(A|B) = P(B|A) P(A) / P(B) Assume you choose A and switch to the unopened one Let: P(A) = Probability it is behind the unopened one (B or C): 2/3 P(B) = Probability it is not behind A: 2/3 P(B|A) = Probability it is not behind A, given that it is behind the unopened one (B or C): 1 Then: P(A|B) = Probability it is behind the unopened one (B or C), given that it is not behind A = P(B|A) P(A) / P(B) = (1 x 2/3) / 2/3 = 100% of the time. But it is given that it is not behind A 2/3 of the time, so 2/3 of the time we can be certain of winning if we switch! Probability & Certainty: Intro

- Slides: 21