Prison Heritage and the Ethics of Public Engagement

Prison Heritage and the Ethics of Public Engagement Dr Maryse Tennant, Senior Lecturer, Canterbury Christ Church University @Maryse. Tennant #canterburyprison maryse. tennant@canterbury. ac. uk

Interpretation at penal heritage sites problematic and in need of refinement (see, for example, Garton-Smith, 2000; Wilson, 2008; Walby and Pichet, 2011; Gould, 2014; Welch, 2015, Hodgkinson and Urquhart, 2017) Prison museums are widely recognized as having the potential to enable the public to reflect on the use of imprisonment in contemporary society, although often they fail to do this (Turner and Peters, 2015, Hodgkinson and Urquhart, 2017 a, Wilson et al. , 2017: 5). The relationship between the past and the present is often seen as a key element in this, limiting the capacity of prison museums to enable and informed and critical consideration of the contemporary prison (Wilson, 2008: 44 -5, Turner and Peters, 2015)

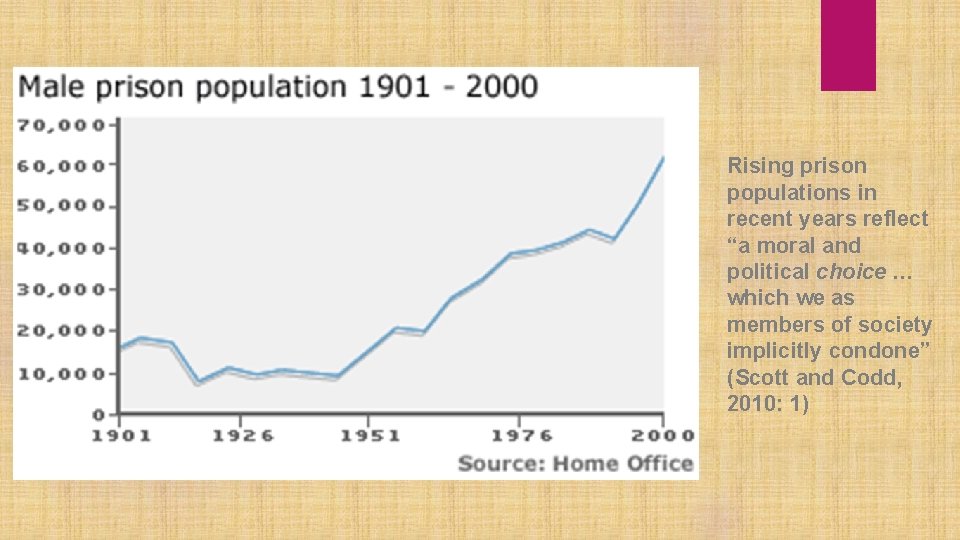

Rising prison populations in recent years reflect “a moral and political choice … which we as members of society implicitly condone” (Scott and Codd, 2010: 1)

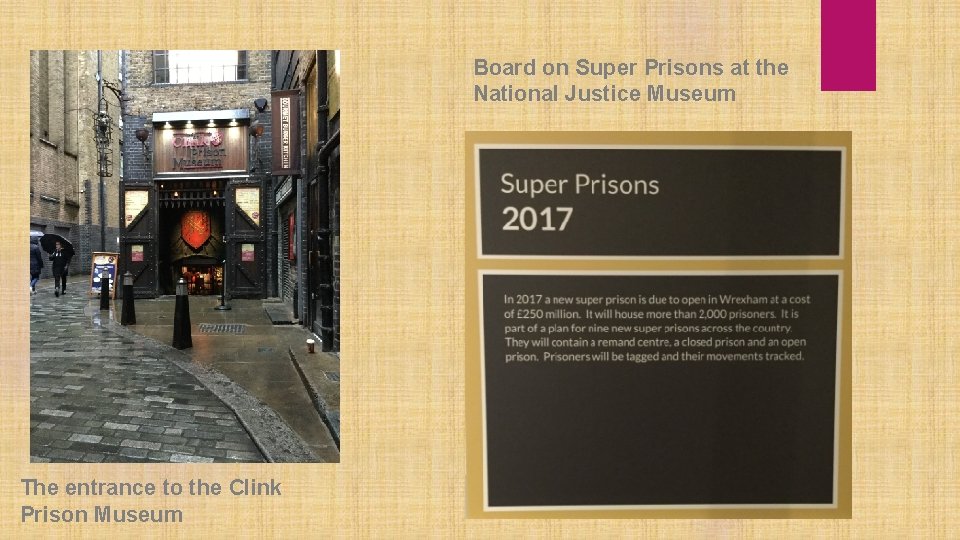

Board on Super Prisons at the National Justice Museum The entrance to the Clink Prison Museum

There is a need for “more ethical, multi-perspective and politically diverse interpretation within prison museums”(Barton and Brown, 2015: 237)

Dissonant Heritage Dissonance relates to a lack of agreement and consistency as to the meaning of heritage (Graham, Ashworth and Tunbridge, 2000: 24). Dissonance forms because heritage is produced through interpretation and selection in a context where multiple meanings are possible (Tunbridge and Ashworth, 1996). Prison heritage has multiple meanings that shift over time, and so dissonance is clearly of relevance for understanding penal sites more generally (Strange and Kempa, 2003: 388). Its presence is more subtle there, however, and also more complex because crime itself is inherently dissonant.

As Brown (2009: 9) reminds us, “punishment is always a narrative about a chain of pain” occurring: “against the backdrop of structural conditions of poverty and vast race and class inequalities, containing within it an immense number of narratives of pain and abuse, where perpetrators and victims bleed together”. The “useablity” of atrocity as heritage is greater when victims are clearly not complicit and perpetrators are “unambiguously identifiable” (Tunbridge and Ashworth, 1996: 104 -5) Rock (1988): the role of victims and offenders “may be reversed, and reversed more than once”.

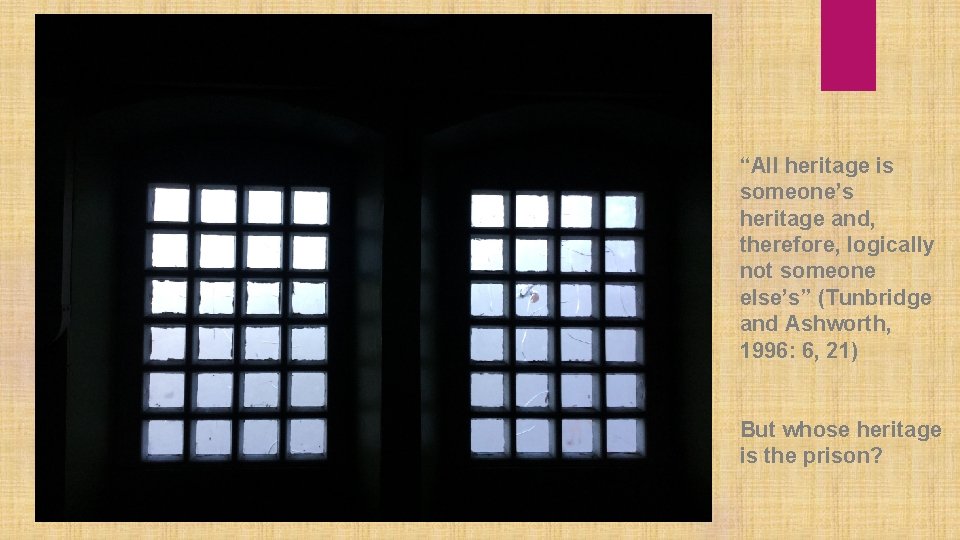

“All heritage is someone’s heritage and, therefore, logically not someone else’s” (Tunbridge and Ashworth, 1996: 6, 21) But whose heritage is the prison?

G’s mother had died in 1945 when he was just five and he was cared for by his maternal grandmother until his father remarried K two years later. She was younger than her husband they went on to have two of their own sons. On the evening of January 28 th 1958, aged just 17, G attacked K, assaulting her both physically and sexually, with the result that she died of her injuries. He then took a fairly large quantity of aspirin but was sick. After this he decided to hand himself in to the nearest police station where he was charged and remanded in custody at Canterbury prison. Graham was eventually convicted for manslaughter rather than murder and sentenced to life imprisonment.

Whilst in prison G confessed to both staff and his father that he had previously had sexual relations with his step-mother and that when she tried again to instigate sex it was this that prompted his attack. He was released after two years on 29 th August 1960 and returned to live with his father, his new step-mother and his two half brothers. G His step-mother His father His half brothers (the children of his victim) His new step-mother His maternal grandmother His step-mother’s parents

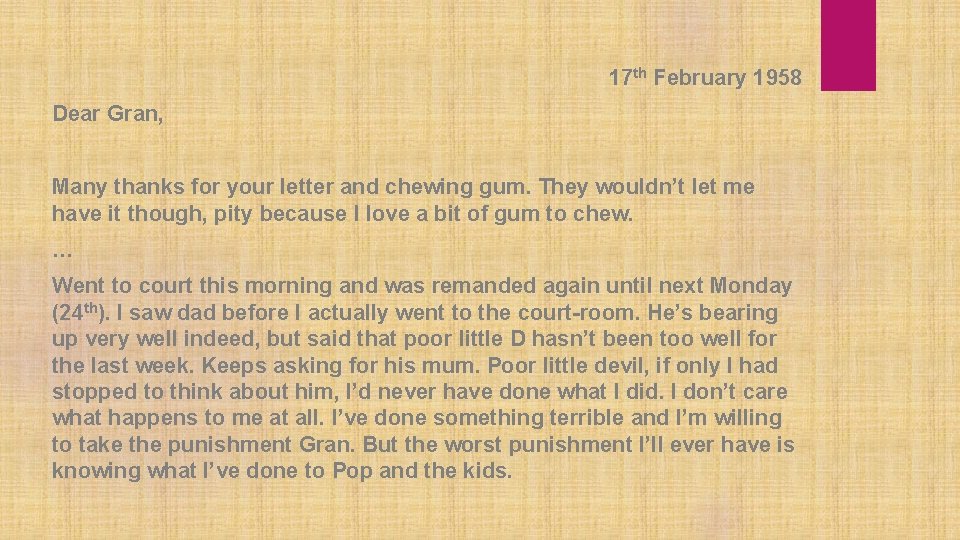

17 th February 1958 Dear Gran, Many thanks for your letter and chewing gum. They wouldn’t let me have it though, pity because I love a bit of gum to chew. … Went to court this morning and was remanded again until next Monday (24 th). I saw dad before I actually went to the court-room. He’s bearing up very well indeed, but said that poor little D hasn’t been too well for the last week. Keeps asking for his mum. Poor little devil, if only I had stopped to think about him, I’d never have done what I did. I don’t care what happens to me at all. I’ve done something terrible and I’m willing to take the punishment Gran. But the worst punishment I’ll ever have is knowing what I’ve done to Pop and the kids.

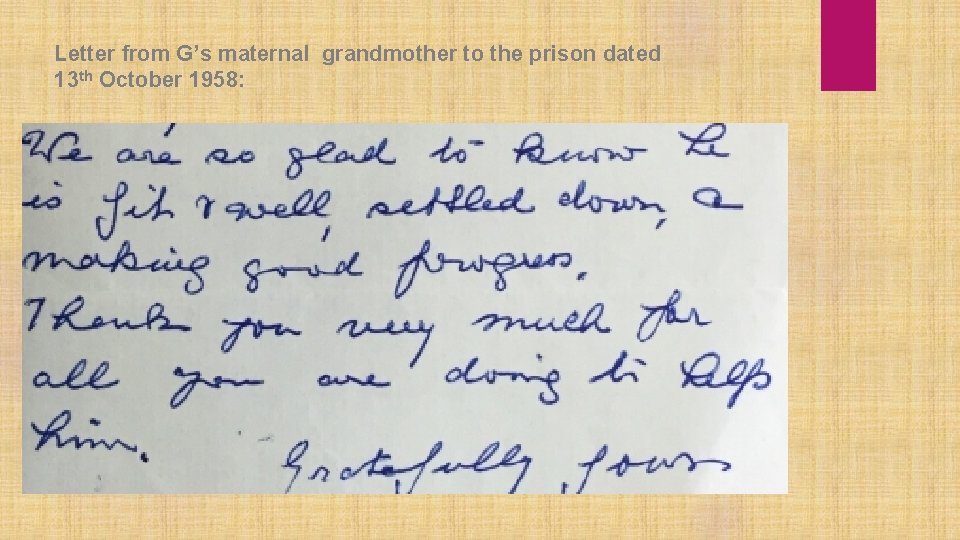

Letter from G’s maternal grandmother to the prison dated 13 th October 1958:

Statement of G’s father to the police January 1958 Letter from G’s father to the Prison Commissioners dated 23 rd September 1958

Letter from G’s new step-mother to Wakefield prison dated 26 rh January 1960

Plan of the crime scene

Letter from K’s parents to the Home Office following G’s release dated 15 th November 1960

Some Tentative Conclusions Heritage is inevitable dissonant. So, too, are crime and punishment. Traditional heritage responses to dissonance “obscure the wider cultural and political contexts within which heritage both sits and serves (Smith, 2006: 82). And so our engagement with dissonance in relation to penal heritage needs to be braoder. This raises challenges for the interpretation of penal heritage and requires us to address further ethical questions. Multi-perspective interpretation may not be possible. Conversely embracing dissonance may provide a way of challenging contemporary perceptions which rest on strict binaries. The creative arts could provide ways of assisting to develop such interpretations.

Barton, A. and Brown, A. (2015) ‘Show me the Prison! The development of prison tourism in the UK’, Crime, Media, Culture, 11(3). 237 -258. British Academy (2014) A Presumption Against Imprisonment: Social Order and Social Values, British Academy: London. Brown, M. (2009) The Culture of Punishment: Prison, Society and Spectacle, New York University Press: New York Condry, R. , Kotova, A. and Minson, S. (2016) ‘Social Injustice and Collateral Damage: The Families and Children of Prisoners’ in Y. Jewkes, J. Bennett and B. Crewe (eds) Handbook on Prisons, Routledge: London, pp. 622 -640. Farrall, S. and Maltby, S. (2003) ‘The Victimisation of Probationers’, Howard Journal of Criminal Justice, 42, 32 -54. Garton-Smith, J. (2000) ‘The prison wall: Interpretations problems for prison musuems’, Open Museum Journal 2, 1 -13 Golding, V. (2009) Learning at the Museum Frontiers: Identify, Race and Power, Ashgate: Surrey. Golding, V. (2017) ‘Developing Pedagogies of Human Rights and Social Justice in the Prison Museum’, in J. Z. Wilson, S. Hodgkinson, J. Piché and K. Walby (eds) Handbook of Prison Tourism, Palgrave: London, pp. 989 -1010. Garland, D. (2001) ‘Introduction: The Meaning of Mass Imprisonment’ in D. Garland (ed. ), Mass Imprisonment: Social Causes and Consequences, SAGE: London, pp. 1 -3.

Gould. M. R. (2014) ‘Return to Alcatraz: Dark Tourism and the Representation of Prison History’, in Death Tourism: Disaster Sites as Recreational Landscape, University of Chicago Press, Chicago, IL Graham, B. , Ashworth, G. J. and Tunbridge, J. E. (2000) A Geography of Heritage: Power, Culture and Economy, Arnold: London Hodgkinson, S. and Urquhart, D. (2017 a) ‘Prison Tourism: Exploring the Spectacle of Punishment in the UK’, G. Hooper and J. J. Lennon (eds) Dark Tourism: Practice and Interpretation, Routledge: Abingdon, pp. ? ? -? ? Hodgkinson, S. and Urquhart, D. (2017 b) ‘Ghost Hunting in Prison: Contemporary Death through sites of Incarceration and the Commodification of the Penal Past’, in J. Z. Wilson, S. Hodgkinson, J. Piché and K. Walby (eds) Handbook of Prison Tourism, Palgrave: London, pp. 559 -582. Home Office (1984) Prison Statistics England Wales 1983, The Stationery Office: London Jennings, W. G. , Piquero, A. R. and Reingle, J. M. (2012) ‘On the Overlap Between Victimization and Offending: A Review of the Literature’, Aggression and Violent Behaviour, 17, 16 -26. Kaufman, E. (2015) Punish and Expel: Border Control, Nationalism and the New Purpose of the Prison, Oxford University Press: Oxford. Kelly, S. (2011) ‘The Ethics (and Plausibility) of Emotional Detachment in Programming at Eastern State Penitentiary’, Museums and Social Justice, 6(1), 7 -17.

Logan, W. and Reeves, K. (2009) ‘Introduction: Remembering Places of Shame and Pain’ in W. Logan and K. Reeves (eds) Places of Pain and Shame: Dealing with ‘Difficult Heritage’, Routledge: London Millie, ? , Jacobson, J. and Hough, M. (2005) ‘Understanding the growth in the prison population in England Wales’, in C. Emsley (ed. ) The Persistent Prison, Francis Boutle: London, pp. 91 -112. Ministry of Justice (2018) Population Bulletin: Weekly 6 April 2018 available at: https: //www. gov. uk/government/statistics/prison-population-figures-2018 (Accessed 10 th April 2018). Pratt, J. (2007) Penal Populism, Routledge: London. Scott, D. and Codd, H. (2010) Controversial Issues in Prisons, Open University Press: Maidenhead Stone, P. R. (2009) ‘Dark Tourism: Morality and New Moral Spaces’ in in R. Sharpley and P. R. Stone (eds) The Darker Side of Travel: Theory and Practice of Dark Tourism, Channel View: Bristol, pp. 56 -72 Strange, C. and Kempa, M. (2003) ‘Shade of Dark Tourism: Alcatraz and Robben Island’, Annals of Tourism Research, 30 (2), 386 -405 Tunbridge, J. E. and Ashworth, G. J. (1996) Dissonant Heritage: The Management of the Past as a Resource in Conflict, Wiley and Sons: Chichester Turner, J. (2016) The Prison Boundary: Between Society and Carceral Space, Palgrave: London Turner, J. and Peters, K. (2015) ‘Doing Time-Travel: Peforming Past and Present at the Prison Museum’ in K. M. Morin and D. Morin (eds) Historical Geographies of Prison: Unlocking the Usable Carceral Past, Routledge: New York, pp. ? ? -? ? .

Walby, K. and Piché, J. (2011) ‘The Polysemy of Punishment Memorialisation: Dark Tourism and Ontario’s Penal History Museums’, Punishment and Society, 13(4), 451 -472 Welch, M. (2015) Escape to Prison: Penal Tourism and the Pull of Punishment, University of California Press: Oakland, CA Wilson, J. Z. (2008) Prison: Cultural Memory and Dark Tourism, Peter Lang: London Wilson, J. Z. , Hodgkinson, S. , Piché, J. and Walby, K. (2017) ‘Introduction: Prison Tourism in Context’ in J. Z. Wilson, S. Hodgkinson, J. Piché and K. Walby (eds) Handbook of Prison Tourism, Palgrave: London, pp. 1 -10.

- Slides: 21