Print referencing The effectiveness of focusing on print

- Slides: 1

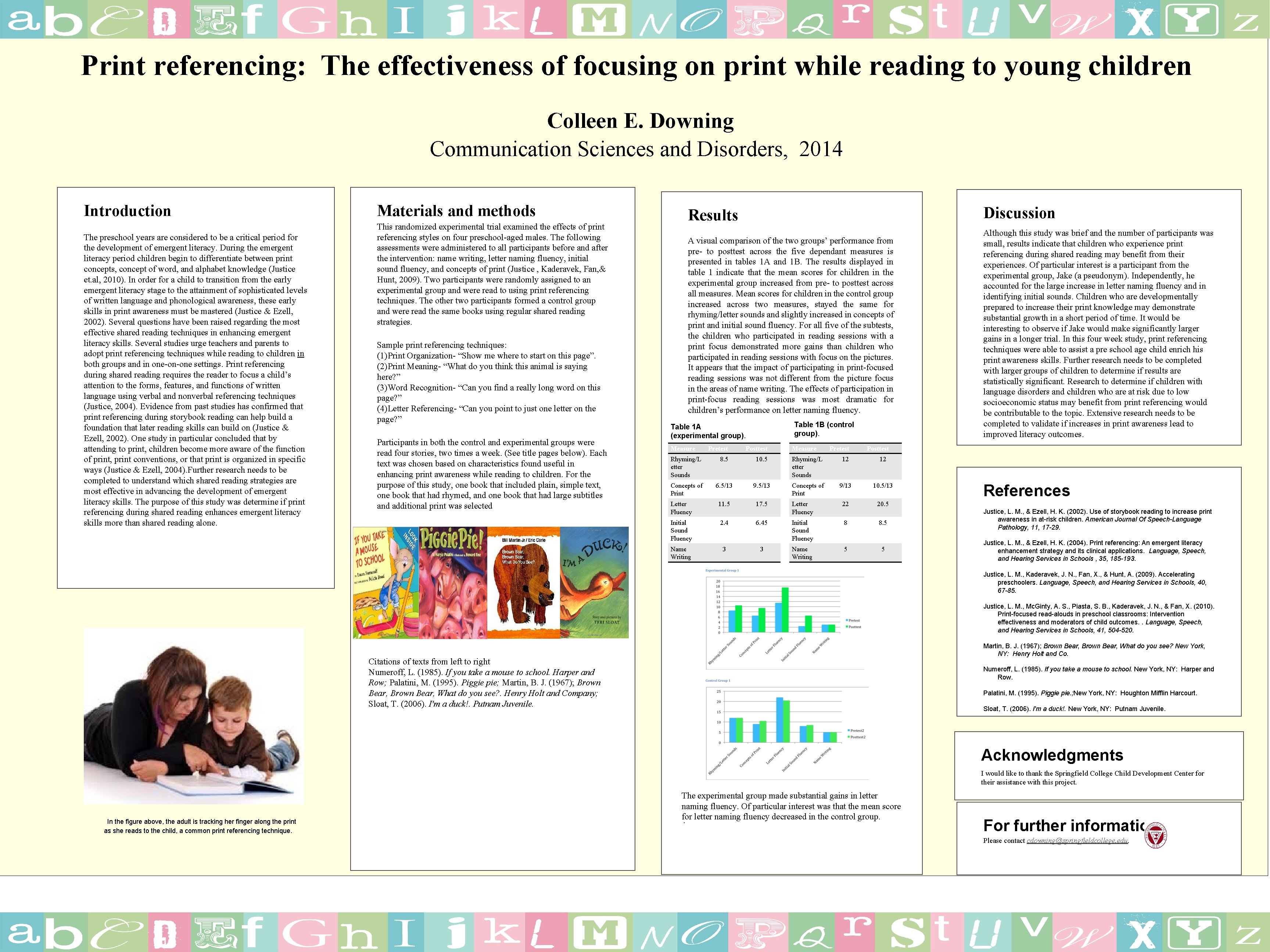

Print referencing: The effectiveness of focusing on print while reading to young children Colleen E. Downing Communication Sciences and Disorders, 2014 Introduction The preschool years are considered to be a critical period for the development of emergent literacy. During the emergent literacy period children begin to differentiate between print concepts, concept of word, and alphabet knowledge (Justice et. al, 2010). In order for a child to transition from the early emergent literacy stage to the attainment of sophisticated levels of written language and phonological awareness, these early skills in print awareness must be mastered (Justice & Ezell, 2002). Several questions have been raised regarding the most effective shared reading techniques in enhancing emergent literacy skills. Several studies urge teachers and parents to adopt print referencing techniques while reading to children in both groups and in one-on-one settings. Print referencing during shared reading requires the reader to focus a child’s attention to the forms, features, and functions of written language using verbal and nonverbal referencing techniques (Justice, 2004). Evidence from past studies has confirmed that print referencing during storybook reading can help build a foundation that later reading skills can build on (Justice & Ezell, 2002). One study in particular concluded that by attending to print, children become more aware of the function of print, print conventions, or that print is organized in specific ways (Justice & Ezell, 2004). Further research needs to be completed to understand which shared reading strategies are most effective in advancing the development of emergent literacy skills. The purpose of this study was determine if print referencing during shared reading enhances emergent literacy skills more than shared reading alone. Materials and methods This randomized experimental trial examined the effects of print referencing styles on four preschool-aged males. The following assessments were administered to all participants before and after the intervention: name writing, letter naming fluency, initial sound fluency, and concepts of print (Justice , Kaderavek, Fan, & Hunt, 2009). Two participants were randomly assigned to an experimental group and were read to using print referencing techniques. The other two participants formed a control group and were read the same books using regular shared reading strategies. Sample print referencing techniques: (1)Print Organization- “Show me where to start on this page”. (2)Print Meaning- “What do you think this animal is saying here? ” (3)Word Recognition- “Can you find a really long word on this page? ” (4)Letter Referencing- “Can you point to just one letter on the page? ” Participants in both the control and experimental groups were read four stories, two times a week. (See title pages below). Each text was chosen based on characteristics found useful in enhancing print awareness while reading to children. For the purpose of this study, one book that included plain, simple text, one book that had rhymed, and one book that had large subtitles and additional print was selected Discussion Results A visual comparison of the two groups’ performance from pre- to posttest across the five dependant measures is presented in tables 1 A and 1 B. The results displayed in table 1 indicate that the mean scores for children in the experimental group increased from pre- to posttest across all measures. Mean scores for children in the control group increased across two measures, stayed the same for rhyming/letter sounds and slightly increased in concepts of print and initial sound fluency. For all five of the subtests, the children who participated in reading sessions with a print focus demonstrated more gains than children who participated in reading sessions with focus on the pictures. It appears that the impact of participating in print-focused reading sessions was not different from the picture focus in the areas of name writing. The effects of participation in print-focus reading sessions was most dramatic for children’s performance on letter naming fluency. Table 1 B (control group). Table 1 A (experimental group). Measure Pretest Posttest Rhyming/L etter Sounds 8. 5 10. 5 Rhyming/L etter Sounds 12 12 Concepts of Print 6. 5/13 9. 5/13 Concepts of Print 9/13 10. 5/13 Letter Fluency 11. 5 17. 5 Letter Fluency 22 20. 5 Initial Sound Fluency 2. 4 Initial Sound Fluency 8 Name Writing 3 Name Writing 5 6. 45 3 Measure Pretest Although this study was brief and the number of participants was small, results indicate that children who experience print referencing during shared reading may benefit from their experiences. Of particular interest is a participant from the experimental group, Jake (a pseudonym). Independently, he accounted for the large increase in letter naming fluency and in identifying initial sounds. Children who are developmentally prepared to increase their print knowledge may demonstrate substantial growth in a short period of time. It would be interesting to observe if Jake would make significantly larger gains in a longer trial. In this four week study, print referencing techniques were able to assist a pre school age child enrich his print awareness skills. Further research needs to be completed with larger groups of children to determine if results are statistically significant. Research to determine if children with language disorders and children who are at risk due to low socioeconomic status may benefit from print referencing would be contributable to the topic. Extensive research needs to be completed to validate if increases in print awareness lead to improved literacy outcomes. Posttest 8. 5 5 References Justice, L. M. , & Ezell, H. K. (2002). Use of storybook reading to increase print awareness in at-risk children. American Journal Of Speech-Language Pathology, 11, 17 -29. Justice, L. M. , & Ezell, H. K. (2004). Print referencing: An emergent literacy enhancement strategy and its clinical applications. Language, Speech, and Hearing Services in Schools , 35, 185 -193. Justice, L. M. , Kaderavek, J. N. , Fan, X. , & Hunt, A. (2009). Accelerating preschoolers. Language, Speech, and Hearing Services in Schools, 40, 67 -85. Justice, L. M. , Mc. Ginty, A. S. , Piasta, S. B. , Kaderavek, J. N. , & Fan, X. (2010). Print-focused read-alouds in preschool classrooms: Intervention effectiveness and moderators of child outcomes. . Language, Speech, and Hearing Services in Schools, 41, 504 -520. Martin, B. J. (1967); Brown Bear, What do you see? New York, NY: Henry Holt and Co. Citations of texts from left to right Numeroff, L. (1985). If you take a mouse to school. Harper and Row; Palatini, M. (1995). Piggie pie; Martin, B. J. (1967); Brown Bear, What do you see? . Henry Holt and Company; . T. (2006). I'm a duck!. Putnam Juvenile. Sloat, Numeroff, L. (1985). If you take a mouse to school. New York, NY: Harper and Row. Palatini, M. (1995). Piggie pie. ; New York, NY: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. Sloat, T. (2006). I'm a duck!. New York, NY: Putnam Juvenile. Acknowledgments I would like to thank the Springfield College Child Development Center for their assistance with this project. In the figure above, the adult is tracking her finger along the print as she reads to the child, a common print referencing technique. The experimental group made substantial gains in letter naming fluency. Of particular interest was that the mean score for. letter naming fluency decreased in the control group. For further information Please contact cdowning@springfieldcollege. edu.