Principles of Stylistic Analysis Overview I Foregrounding and

- Slides: 14

Principles of Stylistic Analysis

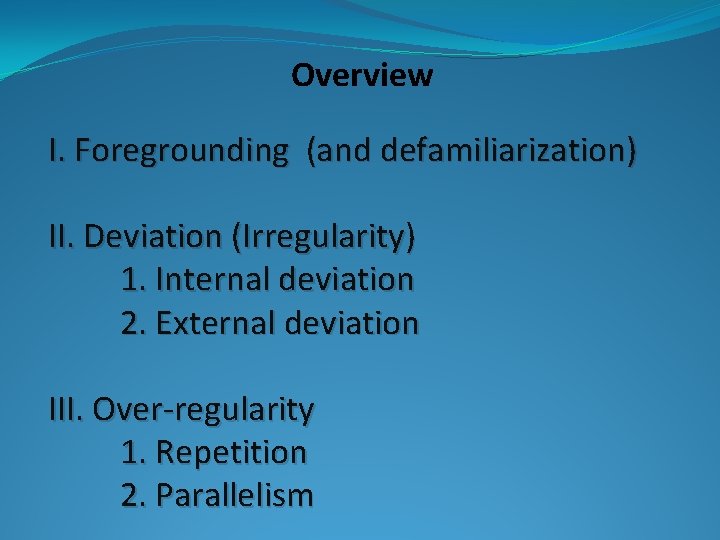

Overview I. Foregrounding (and defamiliarization) II. Deviation (Irregularity) 1. Internal deviation 2. External deviation III. Over-regularity 1. Repetition 2. Parallelism

Foregrounding • Foregrounding is conceptually associated with and derived from the Russian Formalist concept of ‘defamiliarization’ (i. e. ‘making strange’), which was introduced into literary criticism by Russian formalist Shklovsky in 1917 (Gibbons and Whiteley, 2018: 15). • Literary texts defamiliarize/make strange “the familiar to make us reperceive what we have stopped noticing because of its familiarity” (Nørgaard et al. , 2010: 96). • Defamiliarization can be triggered by “a motivated and unexpected linguistic irregularity or over-regularity within a regular context” (Emmott & Alexander, 2016: 291). • This aesthetically motivated manipulation of (ir)regularities is called foregrounding. Thus, foregrounding can be defined as a form of textual patterning which is motivated specifically for literary-aesthetic purposes (Simpson, 2004: 50).

Foregrounding • Foregrounding means that “certain aspects of a text can be made to stand out or appear prominent through forms of textual patterning” (Gibbons & Whiteley, 2018: 15). • Foregrounding can be triggered by the irregular use (i. e. deviation) or overuse (i. e. repetition and parallelism) of different linguistic devices at all levels of text description (Jeffries and Mc. Intyre, 2010: 31– 2; Emmott & Alexander, 2016: 291 -2). • These linguistic devices somehow stand out against the background of the text in which they occur, or against the contextual factors, such as genre and text-type.

Foregrounding • This linguistic salience and cognitive resonance is not arbitrary, but always stylistically motivated (Simpson, 2004: 50). • Unexpected irregularities (i. e. deviation) and over regularities (i. e. repetition and parallelism) tht are not aesthetically motivated cannot be considered instances of foregrounding, but rather linguistic or textual mistakes or anomalies. • Foregrounding makes texts cognitively salient and optimizes relevance, which consequently gives literary texts their aesthetic values. • Since foregrounding enhances the meaning potential of the text, it can be used an analytical category to evaluate the poetic effect of literary texts (Nørgaard et al. , 2010: 96).

Foregrounding • The cognitive salience created by foregrounding can be empirically tested. Being empirically testable, foregrounding can, then, make stylistic analysis more objective and replicable. • For instance, van Peer (2002) contends that foregrounding is more readily perceived by readers and that attention is drawn by deviation. • Texts characterized by foregrounding are processed more slowly, which increases and the amount of affective responses by the readers (van Peer, 2002). • This, arguably, enhances the aesthetic value of the text and reinforces its affective impact on the reader (Nørgaard et al. , 2010: 96).

Foregrounding • Despite its analytical importance, there are two issues that constitute challenges to the notion of foregrounding; these are potential variation of linguistic norms, and conventionalization of deviant forms (Simpson, 2004: 51). • First, linguistic norms may vary within a speech community or community of practice; this variation makes it difficult to determine what constitutes the norm against which the deviation can be made and measured. • Second, as argued by Simpson (2004: 51), once a deviant pattern (with a certain aesthetic value) gains currency, and consequently becomes conventionalized , it “gradually and unobtrusively slip into the background”, which makes it lose its aesthetic value (cf. the cases of dead metaphor and clichés).

Deviation • Deviation is a violation of linguistic norm or (con)textual convention that aims to enhance the aesthetic value of the text and to increase its effective impact on the readers. • Deviation is conceptualized as a motivated “irregularity” (Jeffries and Mc. Intyre, 2010: 31– 2) or “stylistic distortion” (Simpson, 2004: 50). • Deviation can be found at different levels of linguistic and textual description (Wales, 2014: 37). • Two types of deviation can be distinguished; namely, external and internal deviations (Short, 1996).

External Deviation • External deviation refers to the type of deviation that works across different texts. • Such a deviation would be considered stylistically motivated wherever it is used, and it “would therefore be unusual in any text” (Gibbons & Whiteley, 2018: 19). • External deviation is the most common and pervasive type of deviation. An interesting type of external deviation is the wellknown type of grammatical deviation know as ‘poetic license’. • See Gibbons & Whiteley (2018: 19 -20) and Gregoriou (2014: 90 -91) for some examples of external deviation.

Internal Deviation • Internal deviation refers to the type of deviation that works in a particular text only (Simpson, 2004: 51). • Internal deviation is a motivated violation of textual consistency. Such deviation is unusual, i. e. deviant, only in the text in which it is used. • Examples of internal deviation include character’s evident inconsistency or contradiction (Gibbons & Whiteley, 2018: 20 -21), or the use of a linguistic pattern that deviates from the rest of the text (Jeffries, 2014: 483). • See Gibbons & Whiteley (2018: 20 -21) and Gregoriou (2014: 90 -91) for more examples of internal deviation.

Over-regularity • The stylistic effect of foregrounding can also be brought about by means of overuse of regular linguistic patterns. • Overuse of regular patterns stand out against the background of the text or genre in which they occur. • Motivated overuse of regular patterns can be found at various levels of linguistic description(Gibbons & Whiteley, 2018: 19). • Two types of stylistically motivated over-regularities can be distinguished; these are repetition and parallelism. • Yet, some stylisticians prefer to use these terms interchangeably to refer to any case of motivated overuse/repetition of any linguistic pattern.

Repetition • When the overused pattern is a single sound or syllable it is called repetition. Below are some types of repetitions, which all reinforce the stylistic effect and memorability of the text. • Assonance is type of stylistically motivated repetition that involves repeating the same vowel sound in nearby words (Nørgaard et al. , 2010: 50) • Alliteration is type of stylistically motivated repetition that involves repeating a series of word-initial consonant sounds in nearby words (Nørgaard et al. , 2010: 49). • Consonance is type of stylistically motivated repetition that involves repeating a series of non-word-initial consonant sounds in nearby words (Nørgaard et al. , 2010: 63) • Rhyme is type of stylistically motivated repetition that involves repeating the last stressed vowel and the following sounds in two or more words, most typically positioned at the end of verse-lines (Nørgaard et al. , 2010: 145).

Parallelism • When the overused pattern is a word or a grammatical structure, rather than a sound or syllable , this type of over-regularity is called parallelism. • Parallelism tends to suggest to the readers that there is a relationship between two parallel patterns. In this way, the readers are led into seeking an interpretive association between these parallel patterns (Gibbons & Whiteley, 2018: 19). • Such an association can be an association of contrast or of correspondence (Short, 1996: 15; Gibbons & Whiteley, 2018: 19). • An interesting example of contrast parallelism can be found in the following antithesis “Man proposes, God disposes” • An Interesting example of correspondence parallelism can be found in the title of Robert Burns’ well-know poem ‘Red Rose’.

References Emmott, C. & Alexander, M. (2016) Defamiliarization and Foregrounding. In Strirova, v. (Ed. ) The Bloomsbury Companion to Stylistics. London: Bloomsbury. Gregoriou, C. (2014) The linguistic Levels of foregrounding in stylistics. In Burke, M. (Ed. ) The Routledge Handbook of Stylistics. London: Routledge. Jeffries, L. and Mc. Intyre, D. (2010) Stylistics. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Jeffries, L. (2014) Interpretation. In Stockwell, p. & Whiteley, S. (Eds. ) The Cambridge Handbook of Stylistics. London: Cambridge University Press. Nørgaard, N. ; Busse, B. & Montoro, R. (2010) Key Terms in Stylistics. London & New York: Continuum. Short, M. (1996) Exploring the language of poems, plays and prose. Harlow: Addison, Wesley. Longman, Ltd. Simpson, P. (2004) Stylistics: A resource book for students. London: Routledge. van Peer, W. (2002) Where do literary themes come from? . In Louwerse, M. and van Peer, W. (Eds) Thematics: Interdisciplinary Studies. Amsterdam and Philadelphia: John Benjamins. Wales, K. (2014) The Stylistic Tool-kit: Methods and subdisciplines. In Stockwell, p. & Whiteley, S. (Eds. ) The Cambridge Handbook of Stylistics. London: Cambridge University Press.

What are the principles of stylistics

What are the principles of stylistics Foregrounding and backgrounding in discourse analysis

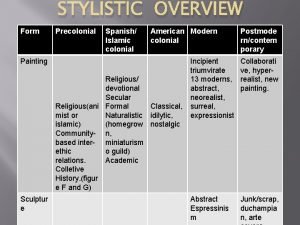

Foregrounding and backgrounding in discourse analysis What is stylistic overview

What is stylistic overview Lexical means

Lexical means Syntactical expressive means

Syntactical expressive means Expressive means and stylistic devices

Expressive means and stylistic devices Expressive means

Expressive means Stylistic continuum in interlanguage

Stylistic continuum in interlanguage Metaphors in romeo and juliet act 4

Metaphors in romeo and juliet act 4 Types of graphon

Types of graphon Blow winds and crack your cheeks stylistic devices

Blow winds and crack your cheeks stylistic devices Chapter 1 overview of financial statement analysis

Chapter 1 overview of financial statement analysis Literary techniques in to kill a mockingbird

Literary techniques in to kill a mockingbird Syntactical devices

Syntactical devices Is symbolism a literary device

Is symbolism a literary device