Primitive Data Types 2 Data Structure 1 C

![Arrays in C int list[5], *plist[5]; list[5]: five integers list[0], list[1], list[2], list[3], list[4] Arrays in C int list[5], *plist[5]; list[5]: five integers list[0], list[1], list[2], list[3], list[4]](https://slidetodoc.com/presentation_image_h2/7bba5c77cab6737f8ba24d713b99e176/image-34.jpg)

![Example: int one[] = {0, 1, 2, 3, 4}; //Goal: print out address and Example: int one[] = {0, 1, 2, 3, 4}; //Goal: print out address and](https://slidetodoc.com/presentation_image_h2/7bba5c77cab6737f8ba24d713b99e176/image-36.jpg)

![Arrays in C (cont’d) Compare int *list 1 and int list 2[5] in C. Arrays in C (cont’d) Compare int *list 1 and int list 2[5] in C.](https://slidetodoc.com/presentation_image_h2/7bba5c77cab6737f8ba24d713b99e176/image-37.jpg)

![Addressing ith element in N dimensional arrays • Address a[i][j] in a[N][M] is S Addressing ith element in N dimensional arrays • Address a[i][j] in a[N][M] is S](https://slidetodoc.com/presentation_image_h2/7bba5c77cab6737f8ba24d713b99e176/image-38.jpg)

![Row Major int a[4][4] ={{0, 1, 2, 3}, {4, 5, …. }} 39 Row Major int a[4][4] ={{0, 1, 2, 3}, {4, 5, …. }} 39](https://slidetodoc.com/presentation_image_h2/7bba5c77cab6737f8ba24d713b99e176/image-39.jpg)

![Column Major int a[4][4] ={{0, 1, 2, 3}, {4, 5, …. }} 40 Column Major int a[4][4] ={{0, 1, 2, 3}, {4, 5, …. }} 40](https://slidetodoc.com/presentation_image_h2/7bba5c77cab6737f8ba24d713b99e176/image-40.jpg)

![Array • int A[2][3][4] = {{{1, 2, 3, 4}, {5, 6, 7, 8}, {9, Array • int A[2][3][4] = {{{1, 2, 3, 4}, {5, 6, 7, 8}, {9,](https://slidetodoc.com/presentation_image_h2/7bba5c77cab6737f8ba24d713b99e176/image-41.jpg)

![Rectangular vs. Jagged matrices • int ar[10][5] 10*5*4 bytes address of ar[0][0]=ar ar+(2*5+3)*4 • Rectangular vs. Jagged matrices • int ar[10][5] 10*5*4 bytes address of ar[0][0]=ar ar+(2*5+3)*4 •](https://slidetodoc.com/presentation_image_h2/7bba5c77cab6737f8ba24d713b99e176/image-42.jpg)

![Explain 43 int a[][3]={{1, 2, 3}, {4, 5, 6}, {7, 8, 9}}; cout << Explain 43 int a[][3]={{1, 2, 3}, {4, 5, 6}, {7, 8, 9}}; cout <<](https://slidetodoc.com/presentation_image_h2/7bba5c77cab6737f8ba24d713b99e176/image-43.jpg)

![Explain Code short x[3][3]={{1, 2, 0}, {3, 4, 0}, {5, 6, 0}}; short *y[3]; Explain Code short x[3][3]={{1, 2, 0}, {3, 4, 0}, {5, 6, 0}}; short *y[3];](https://slidetodoc.com/presentation_image_h2/7bba5c77cab6737f8ba24d713b99e176/image-44.jpg)

![Representing Strings • Null terminated (C) • char str[8]=“HELLO” • Length-prefixed (Pascal) • Object Representing Strings • Null terminated (C) • char str[8]=“HELLO” • Length-prefixed (Pascal) • Object](https://slidetodoc.com/presentation_image_h2/7bba5c77cab6737f8ba24d713b99e176/image-46.jpg)

- Slides: 46

Primitive Data Types 2 Data Structure 1

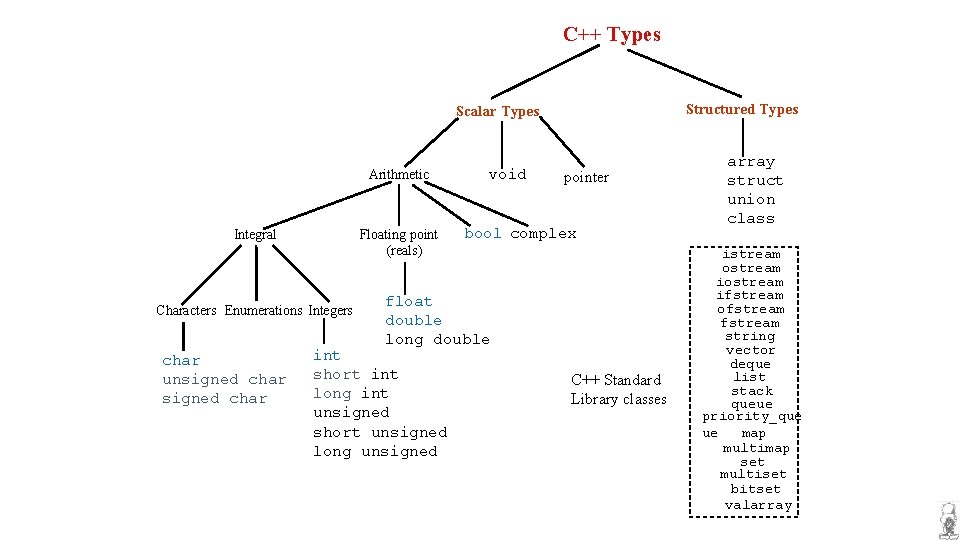

C++ Types Structured Types Scalar Types Arithmetic Integral Floating point (reals) Characters Enumerations Integers char unsigned char void pointer bool complex float double long double int short int long int unsigned short unsigned long unsigned C++ Standard Library classes array struct union class istream ostream ifstream ofstream string vector deque list stack queue priority_que ue map multimap set multiset bitset valarray

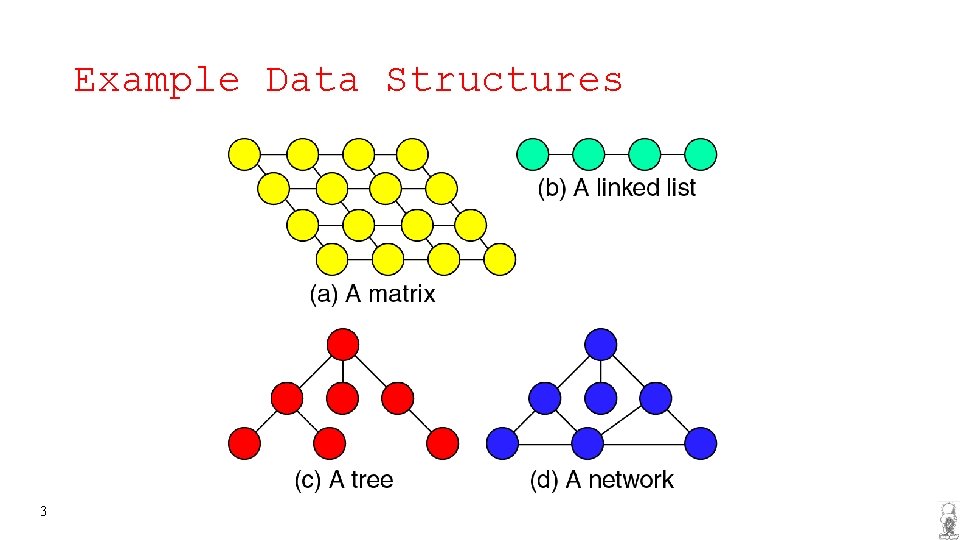

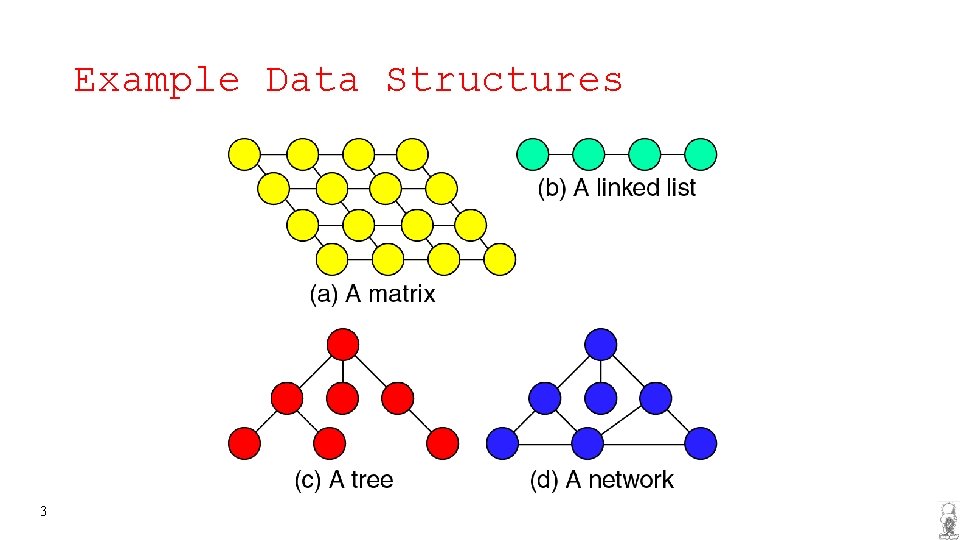

Example Data Structures 3

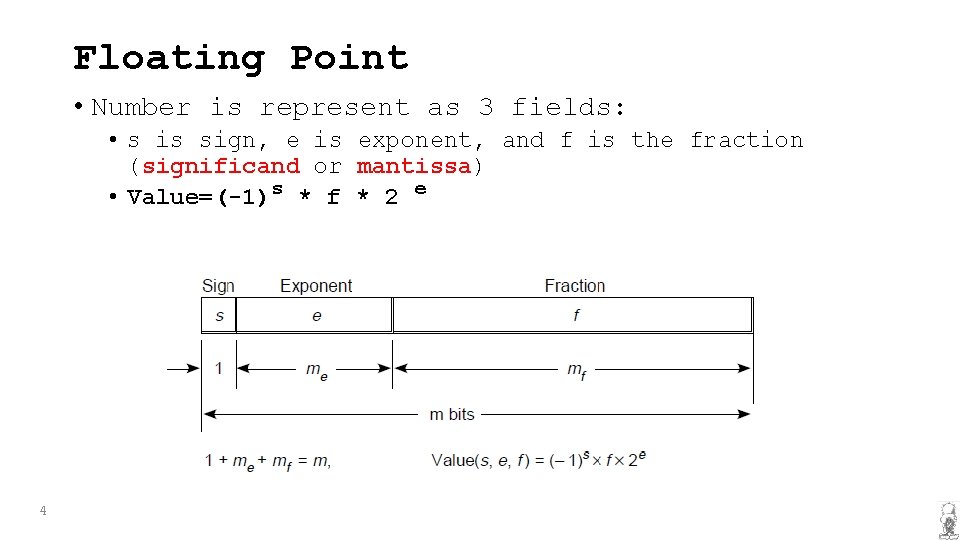

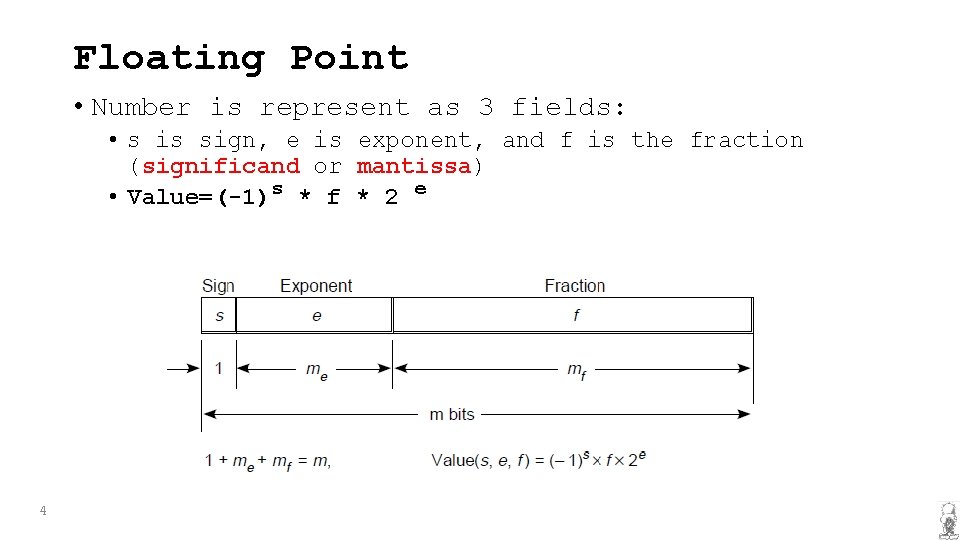

Floating Point • Number is represent as 3 fields: • s is sign, e is exponent, and f is the fraction (significand or mantissa) • Value=(-1)s * f * 2 e 4

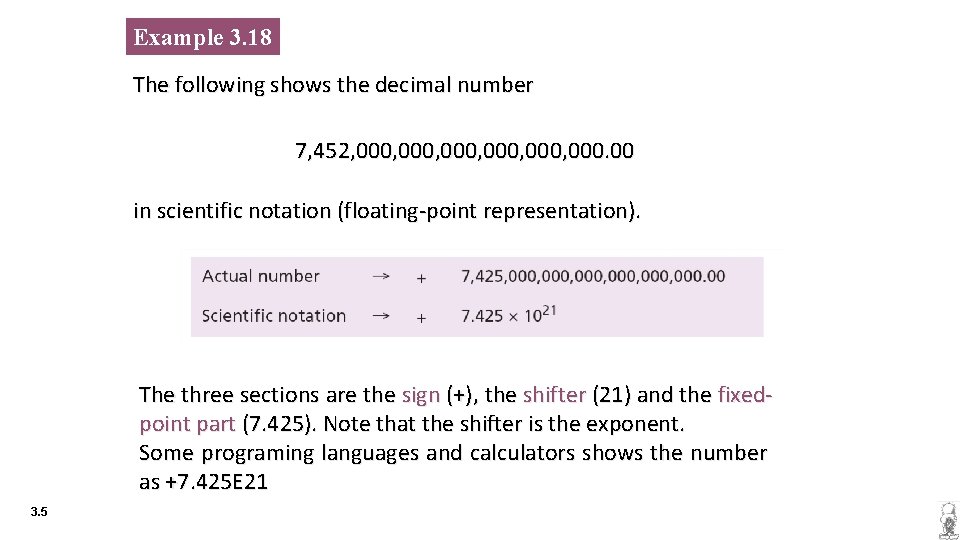

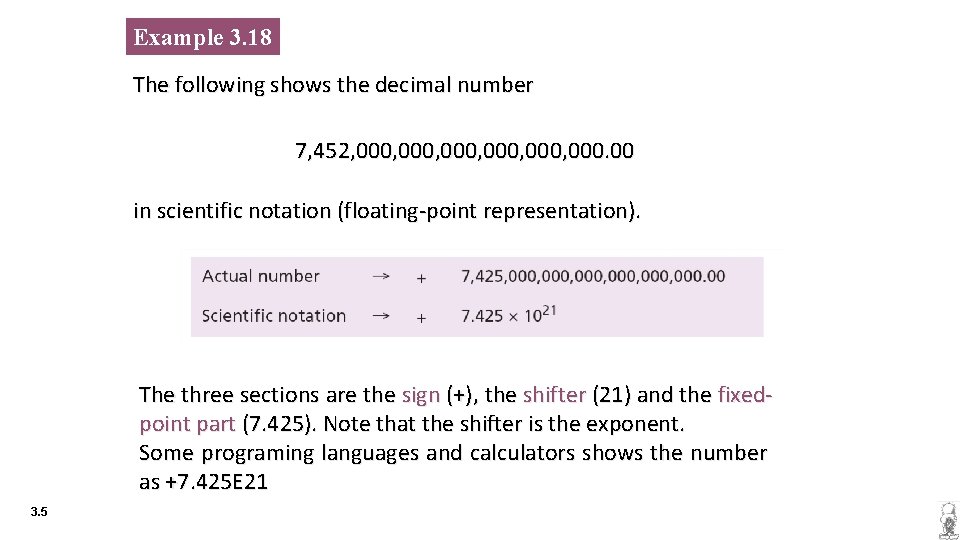

Example 3. 18 The following shows the decimal number 7, 452, 000, 000. 00 in scientific notation (floating-point representation). The three sections are the sign (+), the shifter (21) and the fixedpoint part (7. 425). Note that the shifter is the exponent. Some programing languages and calculators shows the number as +7. 425 E 21 3. 5

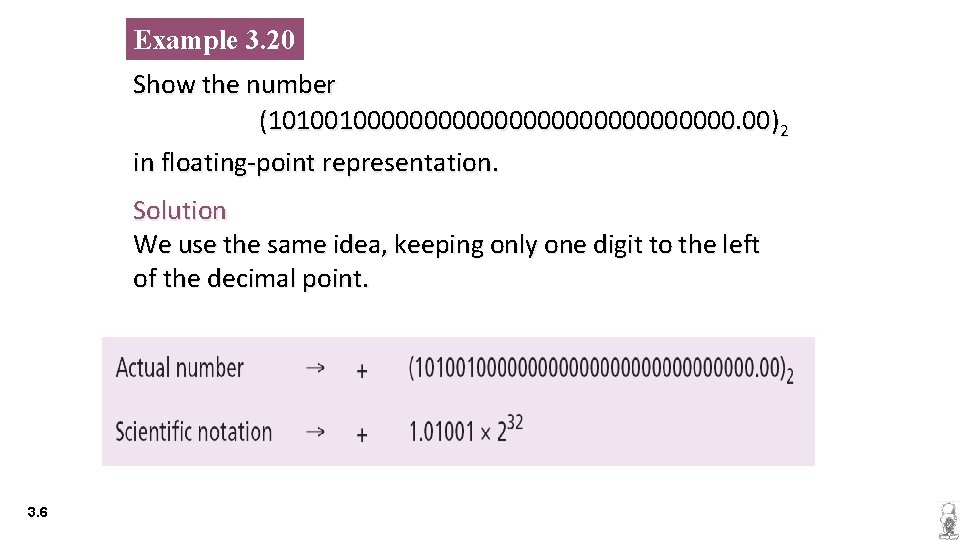

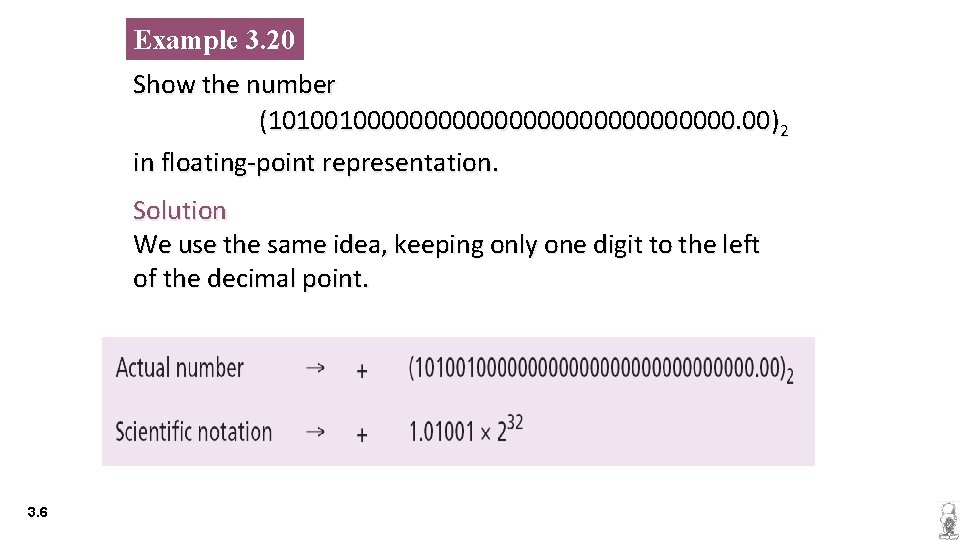

Example 3. 20 Show the number (10100100000000000000. 00) 2 in floating-point representation. Solution We use the same idea, keeping only one digit to the left of the decimal point. 3. 6

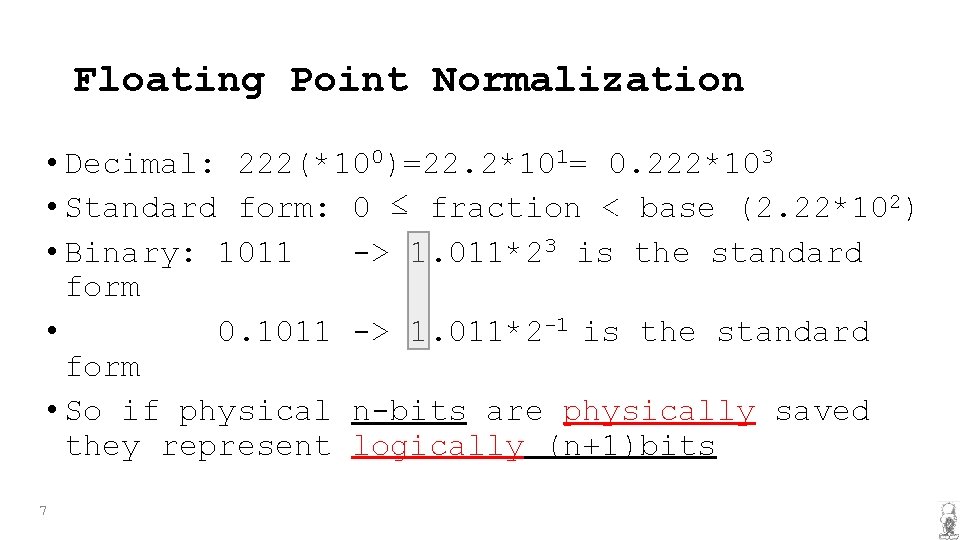

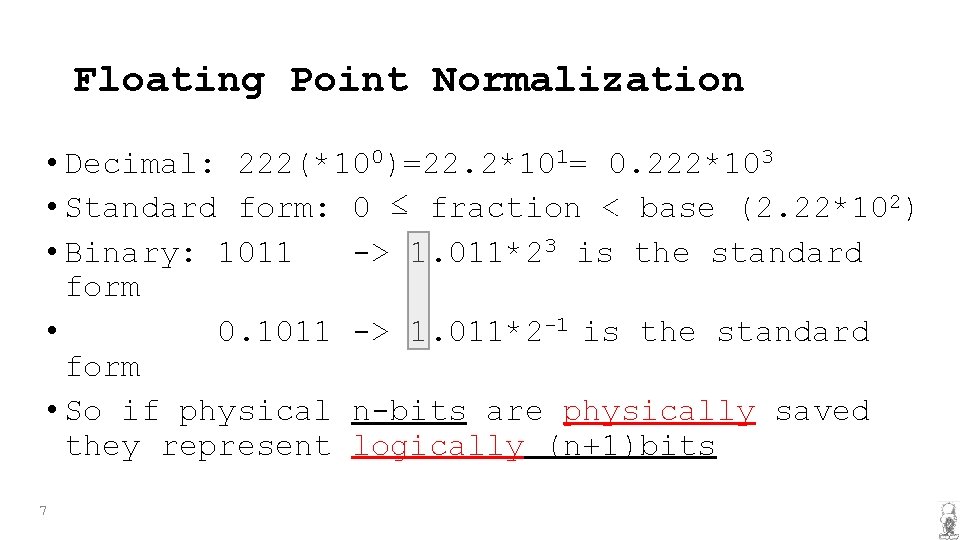

Floating Point Normalization • Decimal: 222(*100)=22. 2*101= 0. 222*103 • Standard form: 0 ≤ fraction < base (2. 22*102) • Binary: 1011 -> 1. 011*23 is the standard form • 0. 1011 -> 1. 011*2 -1 is the standard form • So if physical n-bits are physically saved they represent logically (n+1)bits 7

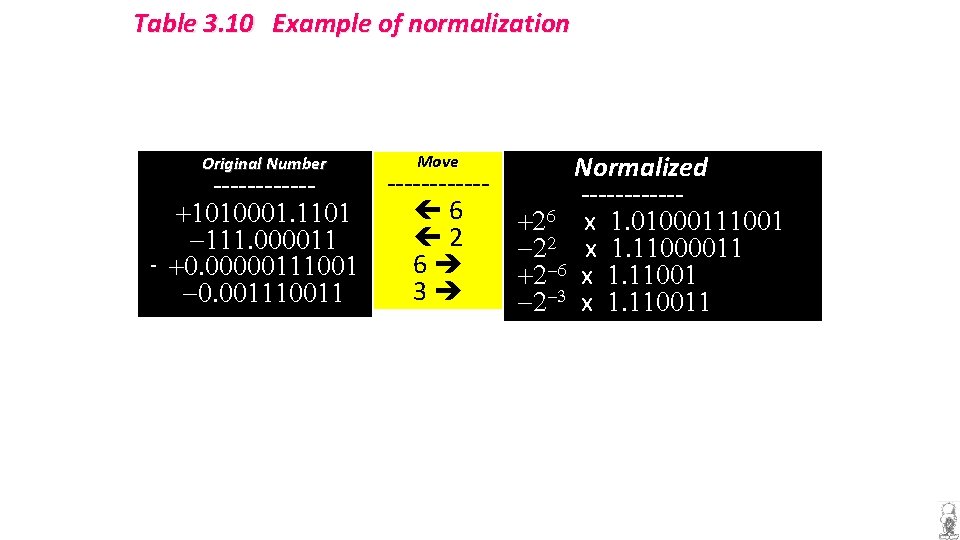

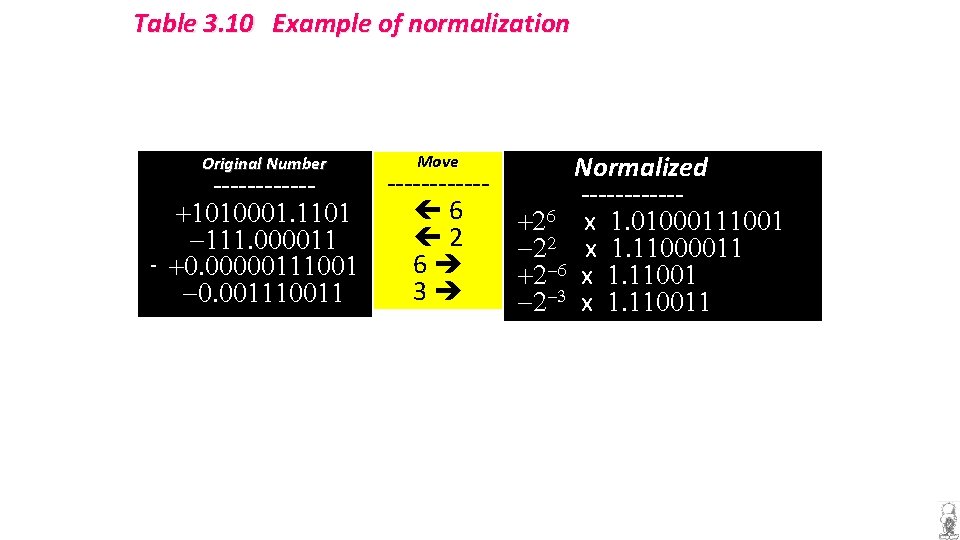

Table 3. 10 Example of normalization Original Number Move ----------------- 6 +1010001. 1101 2 -111. 000011 6 +0. 00000111001 3 -001110011 -0. 001110011 Normalized ------+26 x 1. 01000111001 -22 x 1. 11000011 +2 -6 x 1. 11001 -2 -3 x 1. 110011

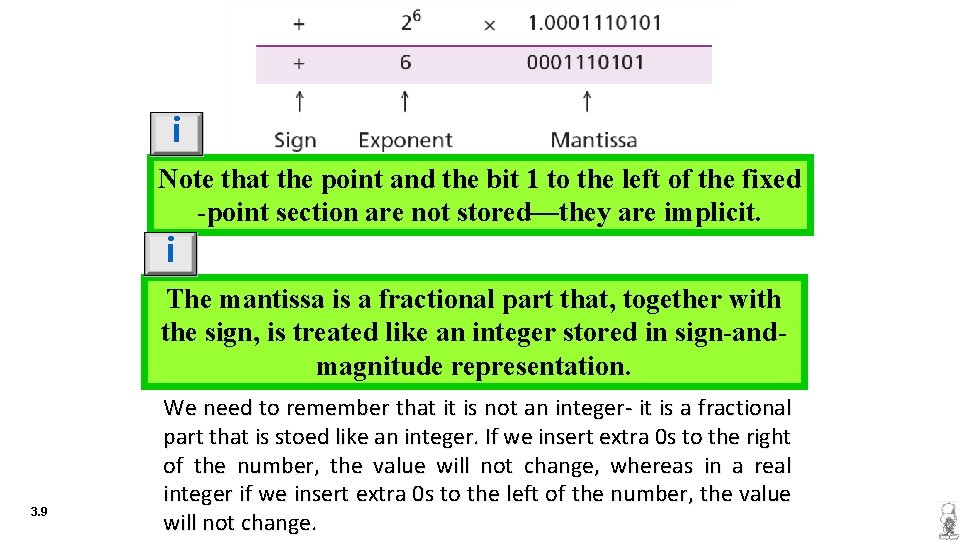

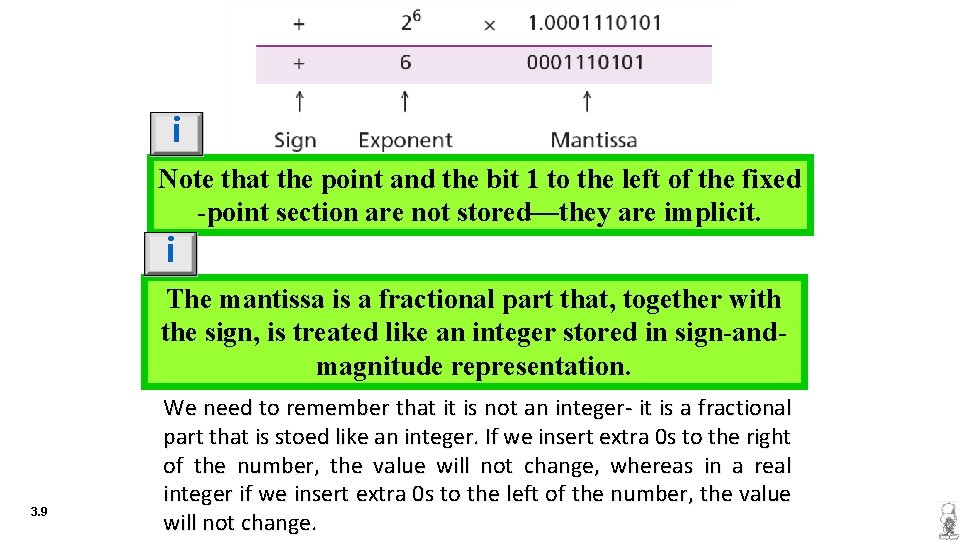

i Note that the point and the bit 1 to the left of the fixed -point section are not stored—they are implicit. i The mantissa is a fractional part that, together with the sign, is treated like an integer stored in sign-andmagnitude representation. 3. 9 We need to remember that it is not an integer- it is a fractional part that is stoed like an integer. If we insert extra 0 s to the right of the number, the value will not change, whereas in a real integer if we insert extra 0 s to the left of the number, the value will not change.

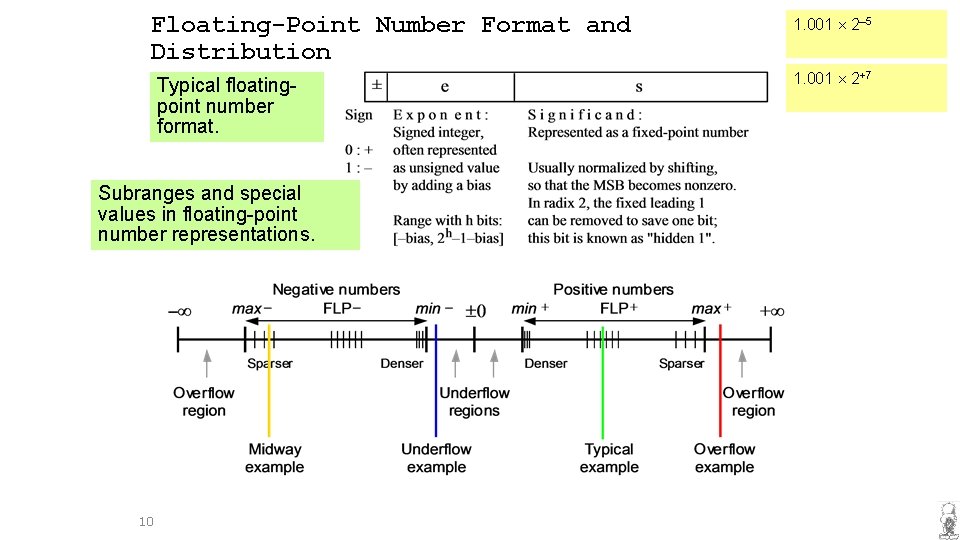

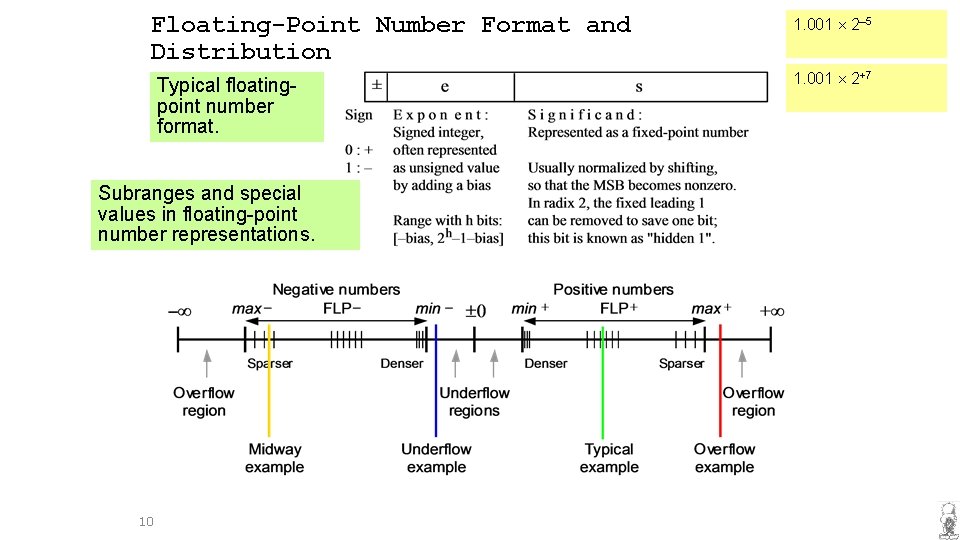

Floating-Point Number Format and Distribution Typical floatingpoint number format. Subranges and special values in floating-point number representations. 10 1. 001 2– 5 1. 001 2+7

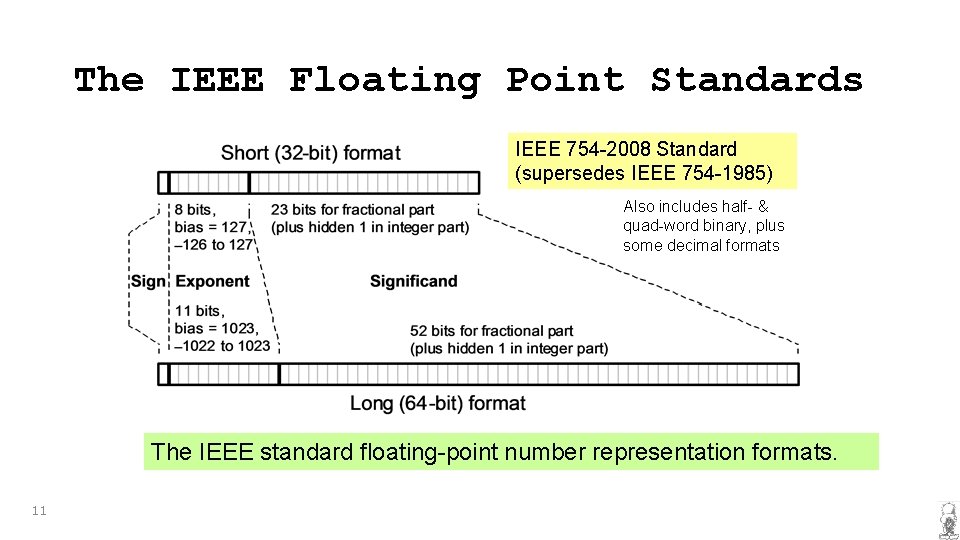

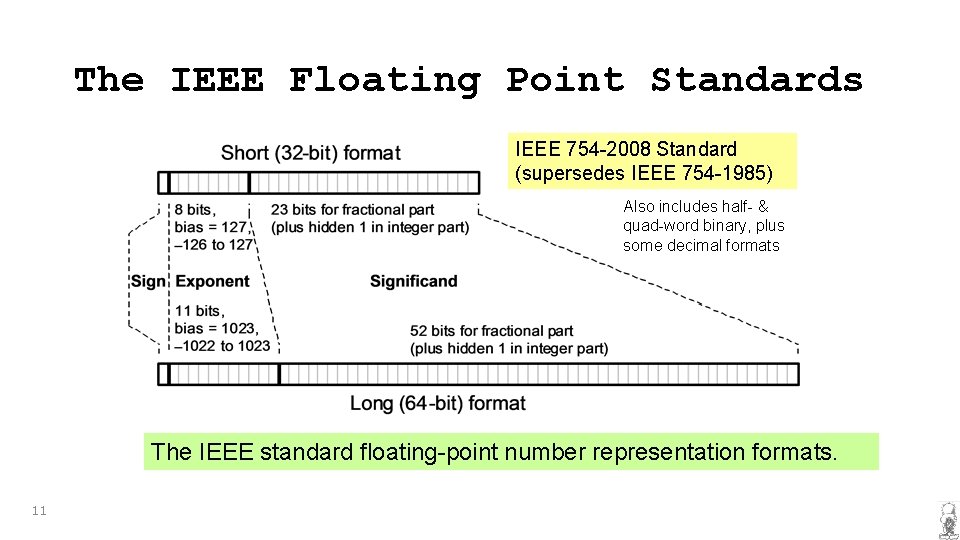

The IEEE Floating Point Standards IEEE 754 -2008 Standard (supersedes IEEE 754 -1985) Also includes half- & quad-word binary, plus some decimal formats The IEEE standard floating-point number representation formats. 11

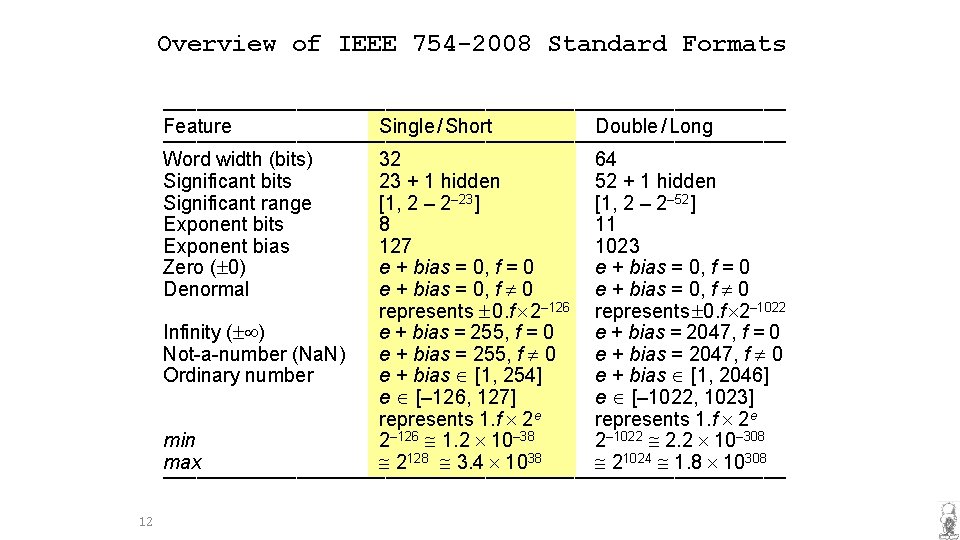

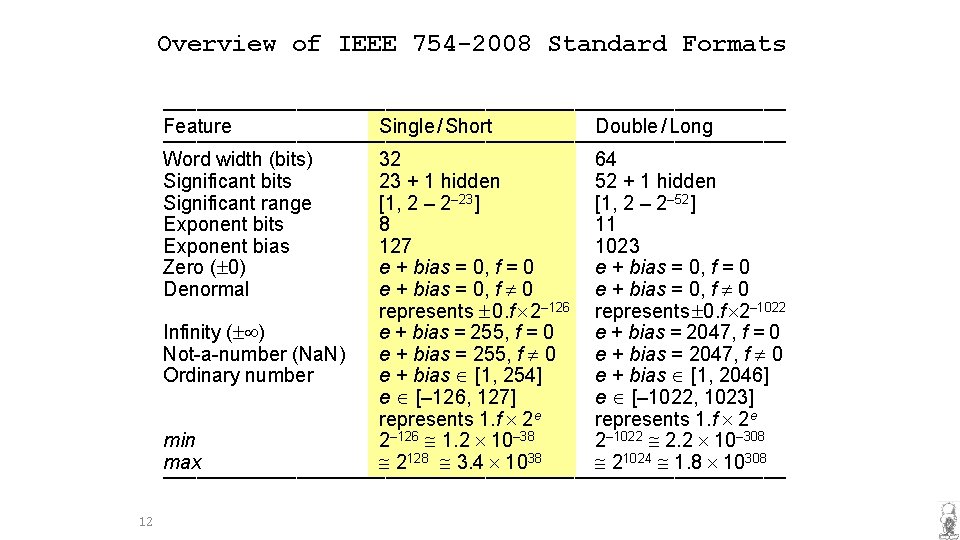

Overview of IEEE 754 -2008 Standard Formats –––––––––––––––––––––––––––– Feature Single / Short Double / Long –––––––––––––––––––––––––––– Word width (bits) 32 64 Significant bits 23 + 1 hidden 52 + 1 hidden Significant range [1, 2 – 2– 23] [1, 2 – 2– 52] Exponent bits 8 11 Exponent bias 127 1023 Zero ( 0) e + bias = 0, f = 0 Denormal e + bias = 0, f 0 represents 0. f 2– 126 represents 0. f 2– 1022 Infinity ( ) e + bias = 255, f = 0 e + bias = 2047, f = 0 Not-a-number (Na. N) e + bias = 255, f 0 e + bias = 2047, f 0 Ordinary number e + bias [1, 254] e + bias [1, 2046] e [– 126, 127] e [– 1022, 1023] represents 1. f 2 e min 2– 126 1. 2 10– 38 2– 1022 2. 2 10– 308 max 2128 3. 4 1038 21024 1. 8 10308 –––––––––––––––––––––––––––– 12

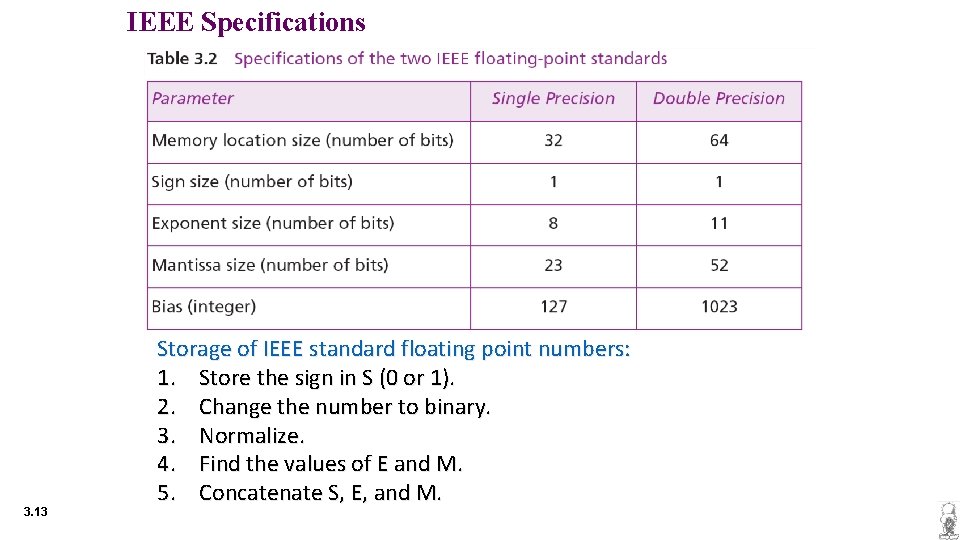

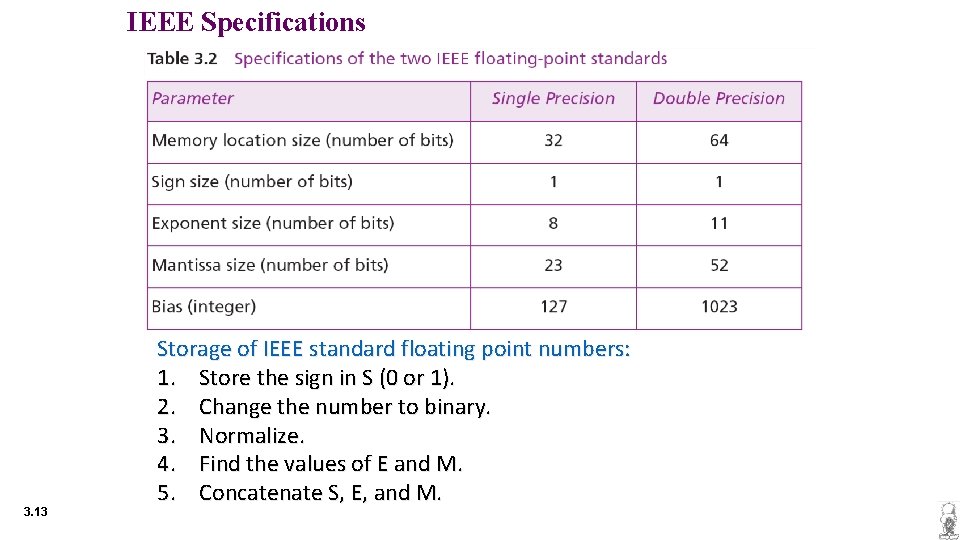

IEEE Specifications 3. 13 Storage of IEEE standard floating point numbers: 1. Store the sign in S (0 or 1). 2. Change the number to binary. 3. Normalize. 4. Find the values of E and M. 5. Concatenate S, E, and M.

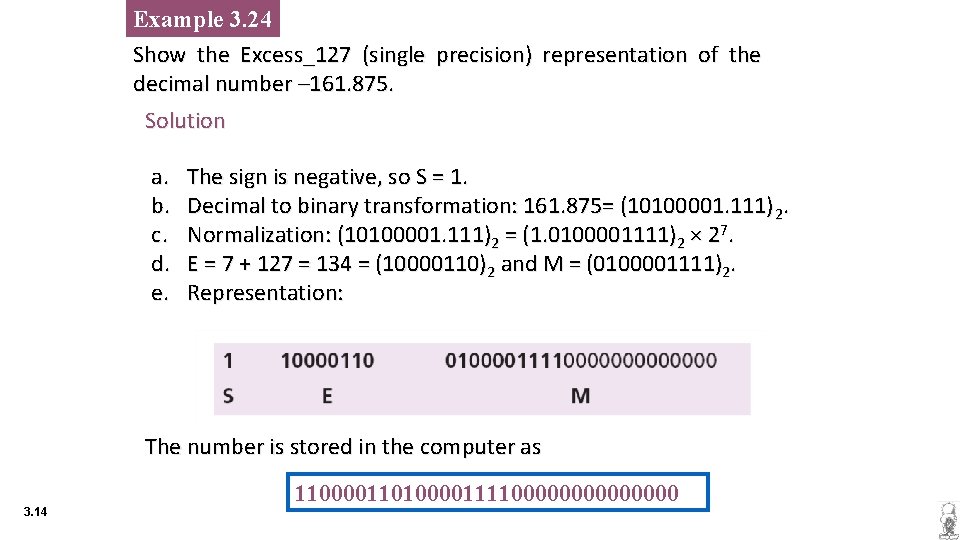

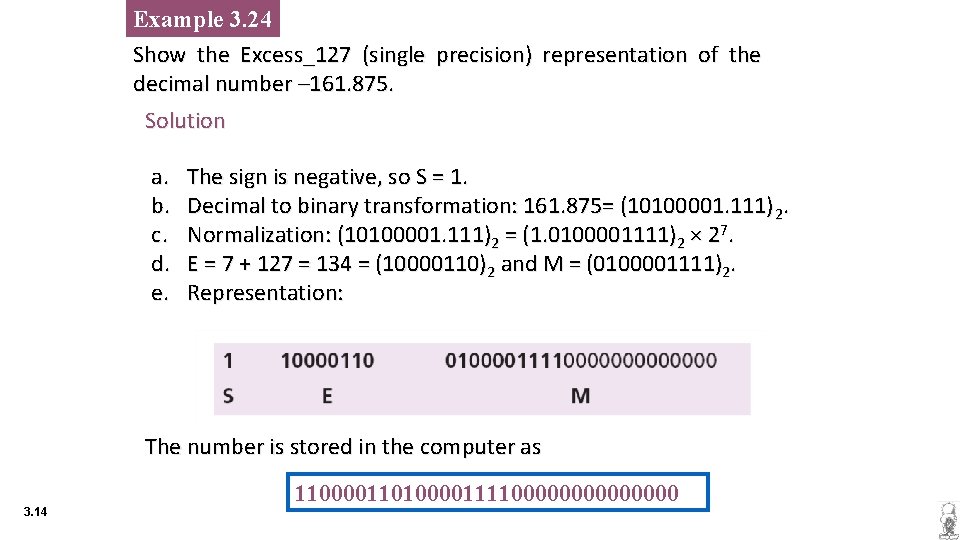

Example 3. 24 Show the Excess_127 (single precision) representation of the decimal number – 161. 875. Solution a. b. c. d. e. The sign is negative, so S = 1. Decimal to binary transformation: 161. 875= (10100001. 111) 2. Normalization: (10100001. 111)2 = (1. 0100001111)2 × 27. E = 7 + 127 = 134 = (10000110)2 and M = (0100001111)2. Representation: The number is stored in the computer as 3. 14 1100001101000011110000000

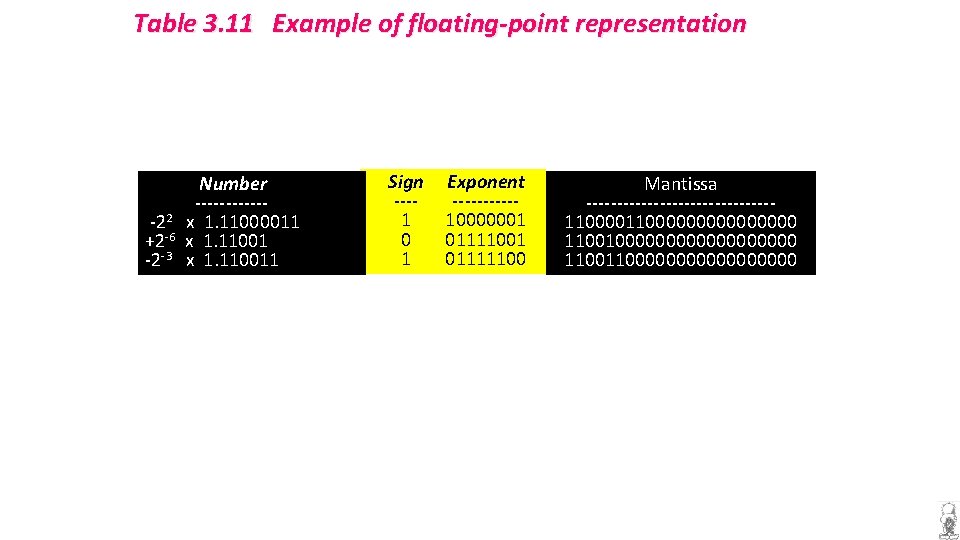

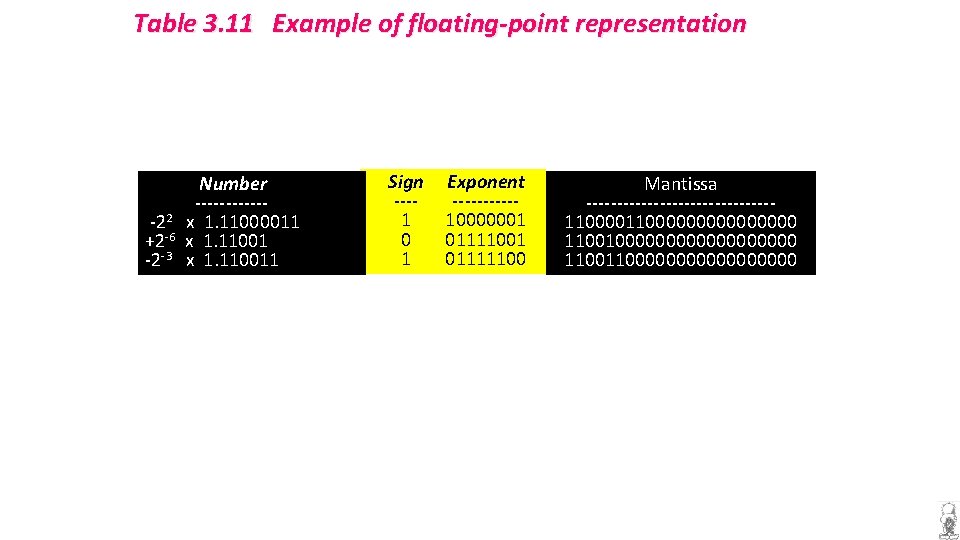

Table 3. 11 Example of floating-point representation Number ------2 -2 x 1. 11000011 +2 -6 x 1. 11001 -2 -3 x 1. 110011 Sign ---1 0 1 Exponent -----10000001 01111100 Mantissa ---------------110000000000 11001000000000 110000000000

Example 3. 26 The bit pattern (11001010000011100001111)2 is stored in Excess_127 format. Show the value in decimal. Solution a. The first bit represents S, the next eight bits, E and the remaining 23 bits, M. b. c. d. e. f. g. 3. 16 The sign is negative. The shifter = E − 127 = 148 − 127 = 21. This gives us (1. 000011100001111)2 × 221. The binary number is (10000111000011. 11)2. The absolute value is 2, 104, 378. 75. The number is − 2, 104, 378. 75.

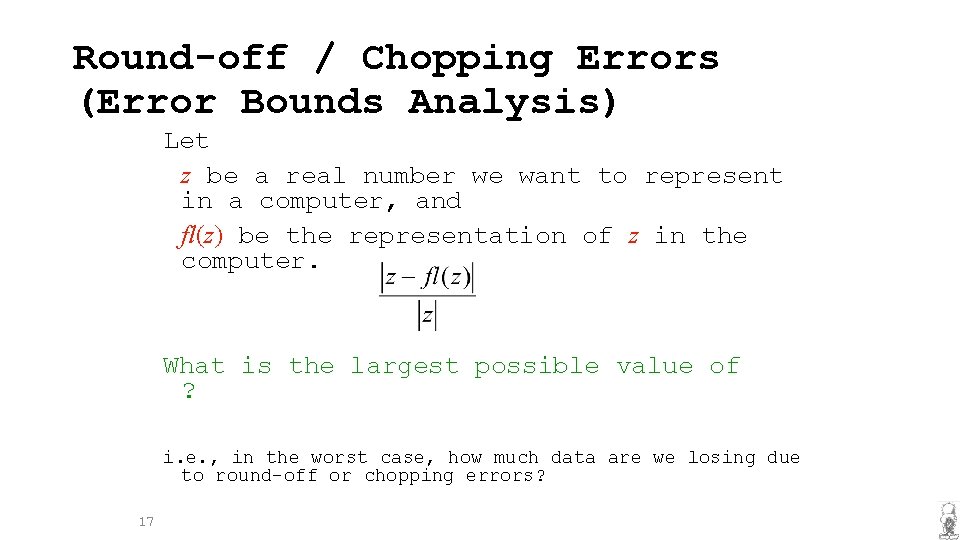

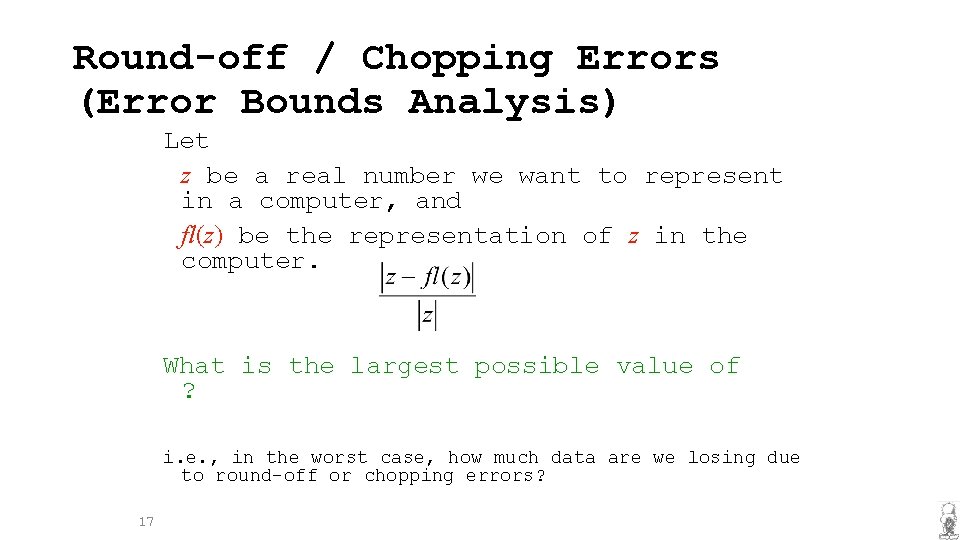

Round-off / Chopping Errors (Error Bounds Analysis) Let z be a real number we want to represent in a computer, and fl(z) be the representation of z in the computer. What is the largest possible value of ? i. e. , in the worst case, how much data are we losing due to round-off or chopping errors? 17

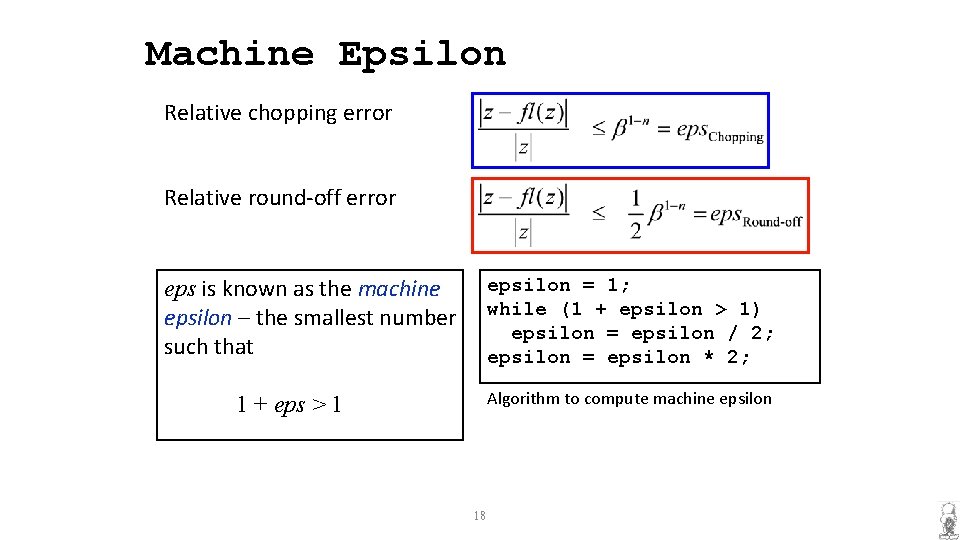

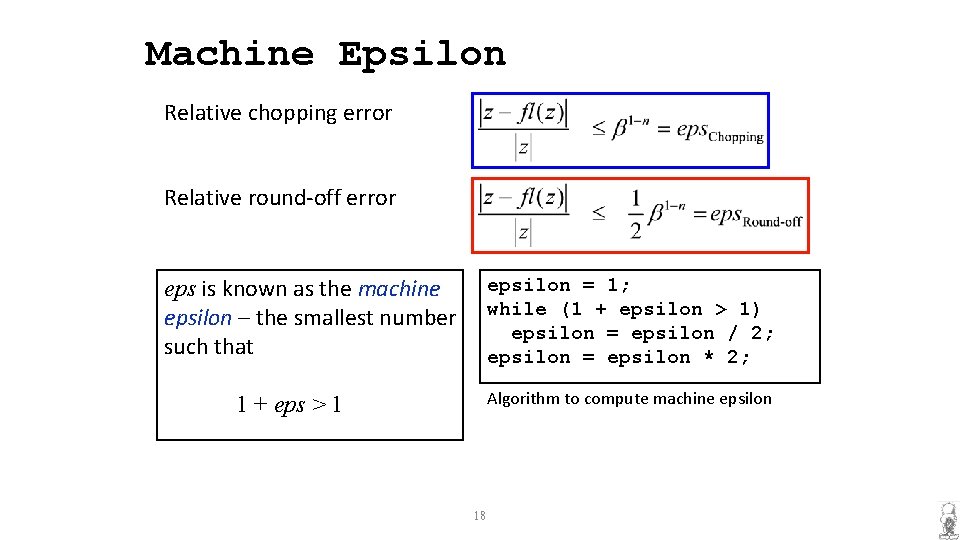

Machine Epsilon Relative chopping error Relative round-off error eps is known as the machine epsilon – the smallest number such that epsilon = 1; while (1 + epsilon > 1) epsilon = epsilon / 2; epsilon = epsilon * 2; Algorithm to compute machine epsilon 1 + eps > 1 18

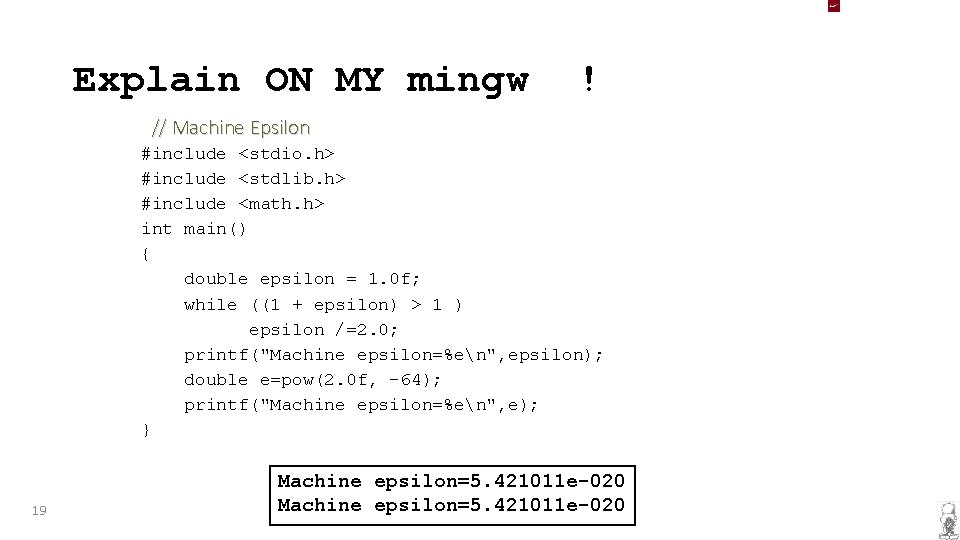

Explain ON MY mingw ! // Machine Epsilon #include <stdio. h> #include <stdlib. h> #include <math. h> int main() { double epsilon = 1. 0 f; while ((1 + epsilon) > 1 ) epsilon /=2. 0; printf("Machine epsilon=%en", epsilon); double e=pow(2. 0 f, -64); printf("Machine epsilon=%en", e); } 19 Machine epsilon=5. 421011 e-020

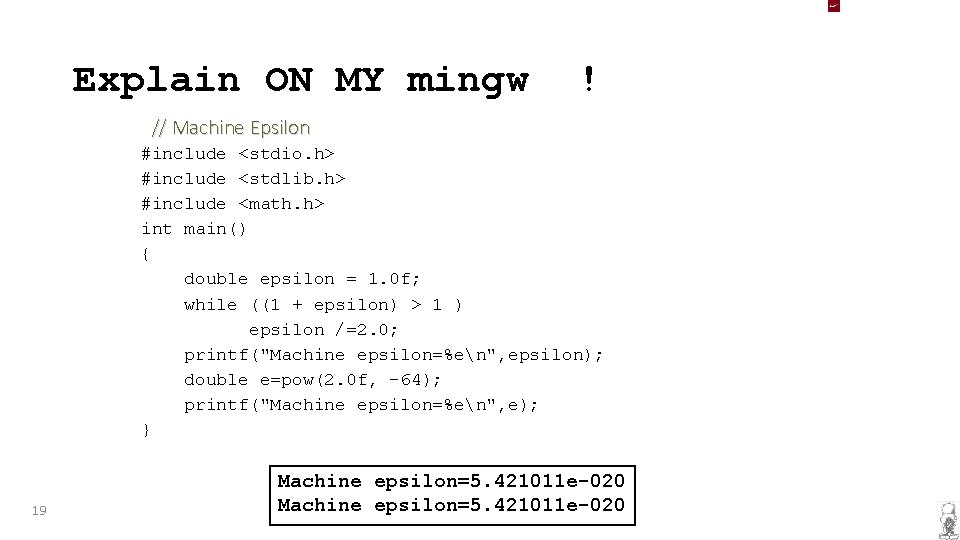

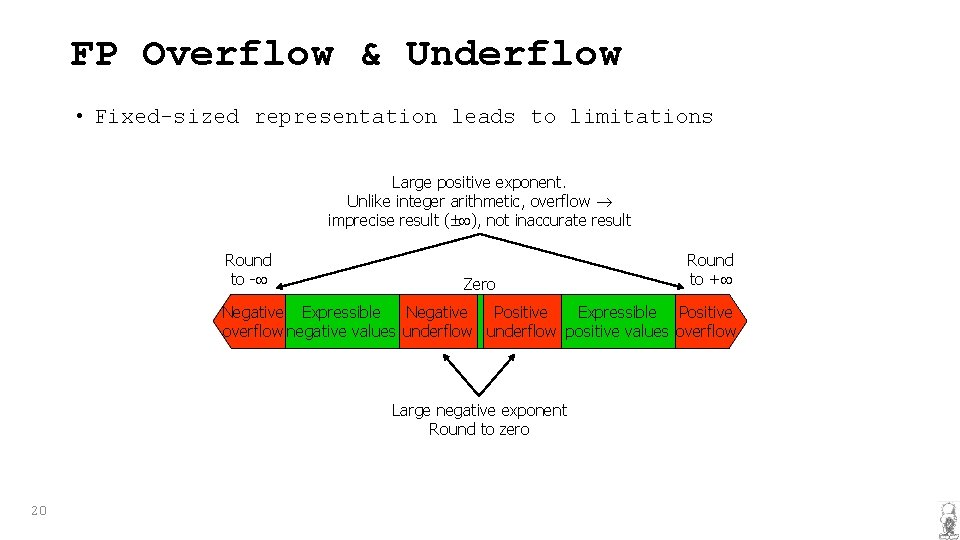

FP Overflow & Underflow • Fixed-sized representation leads to limitations Large positive exponent. Unlike integer arithmetic, overflow imprecise result ( ), not inaccurate result Round to - Zero Round to + Negative Expressible Negative Positive Expressible Positive overflow negative values underflow positive values overflow Large negative exponent Round to zero 20

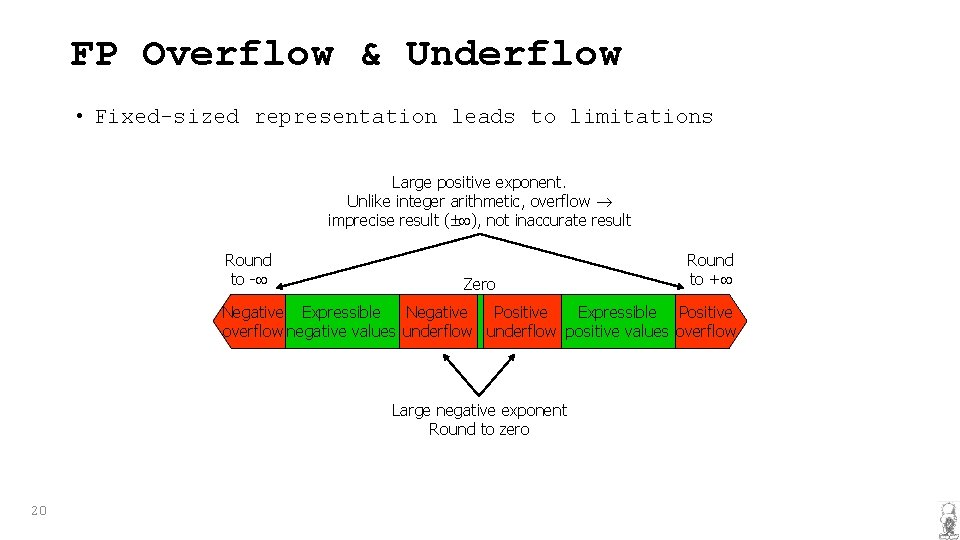

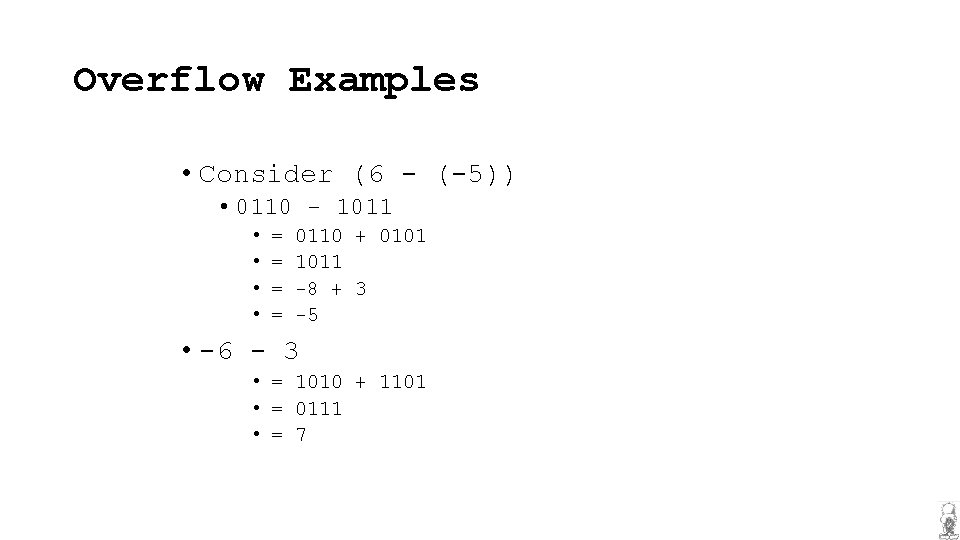

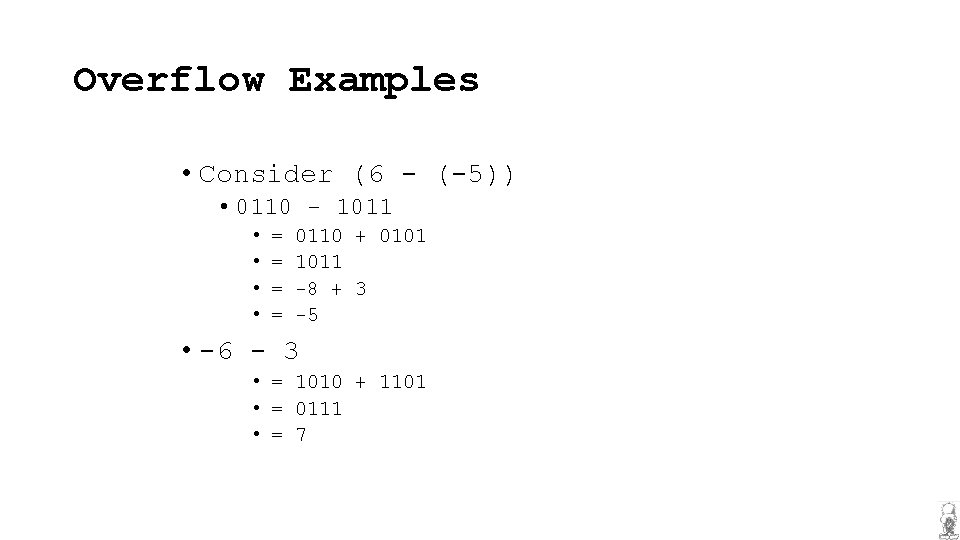

Overflow Examples • Consider (6 - (-5)) • 0110 - 1011 • • = = 0110 + 0101 1011 -8 + 3 -5 • -6 - 3 • = 1010 + 1101 • = 0111 • = 7

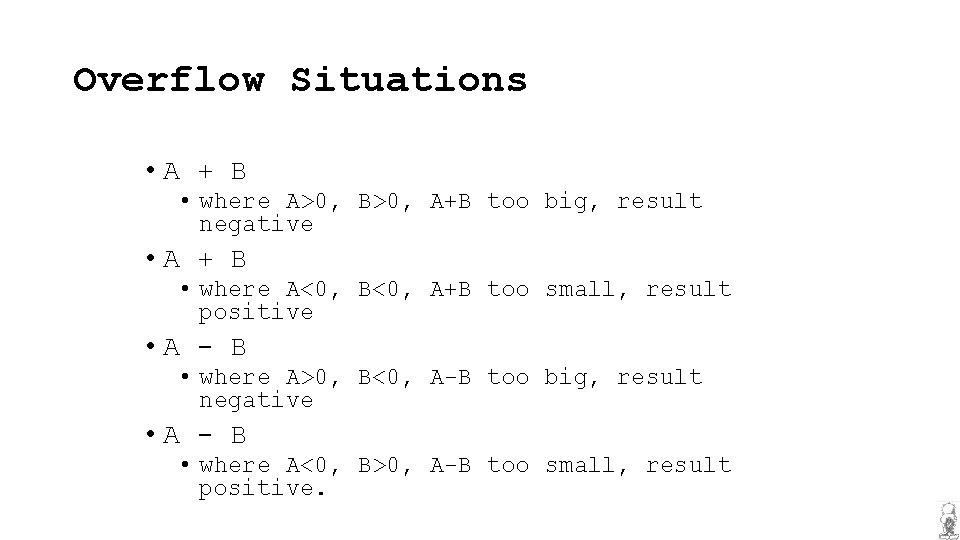

Overflow Situations • A + B • where A>0, B>0, A+B too big, result negative • A + B • where A<0, B<0, A+B too small, result positive • A - B • where A>0, B<0, A-B too big, result negative • A - B • where A<0, B>0, A-B too small, result positive.

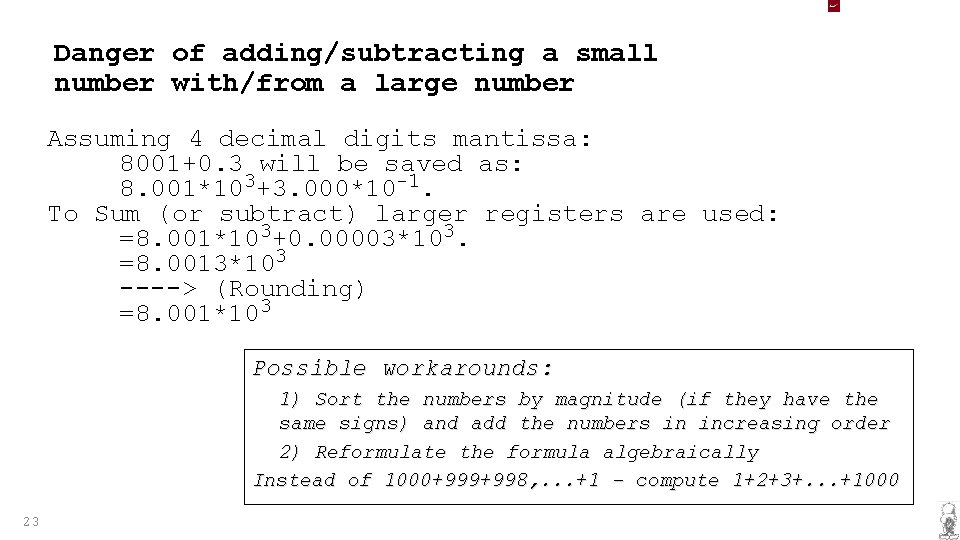

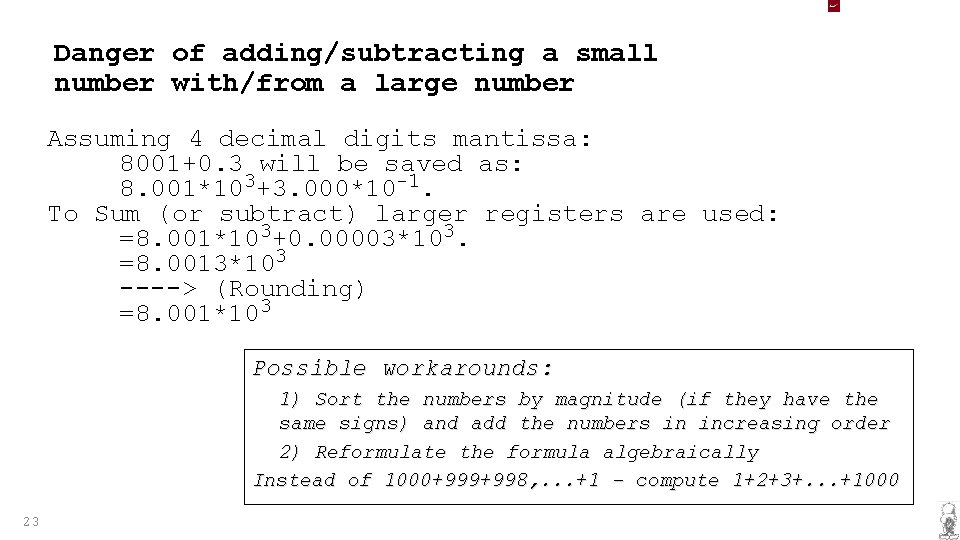

Danger of adding/subtracting a small number with/from a large number Assuming 4 decimal digits mantissa: 8001+0. 3 will be saved as: 8. 001*103+3. 000*10 -1. To Sum (or subtract) larger registers are used: =8. 001*103+0. 00003*103. =8. 0013*103 ----> (Rounding) =8. 001*103 Possible workarounds: 1) Sort the numbers by magnitude (if they have the same signs) and add the numbers in increasing order 2) Reformulate the formula algebraically Instead of 1000+999+998, . . . +1 - compute 1+2+3+. . . +1000 23

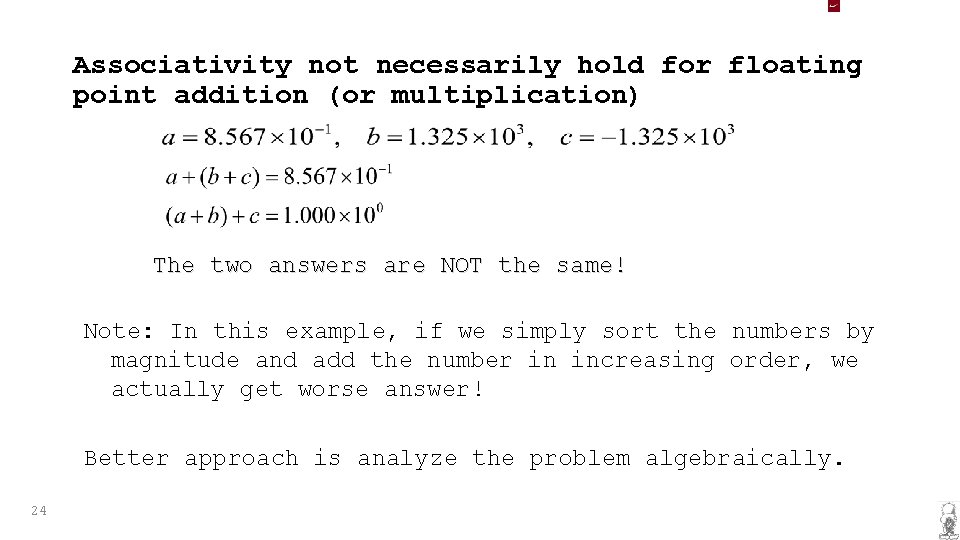

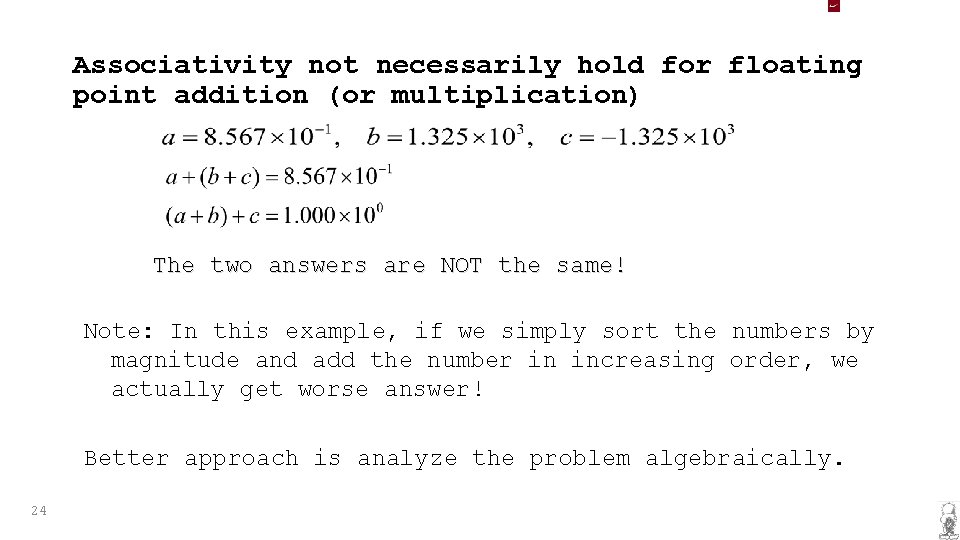

Associativity not necessarily hold for floating point addition (or multiplication) The two answers are NOT the same! Note: In this example, if we simply sort the numbers by magnitude and add the number in increasing order, we actually get worse answer! Better approach is analyze the problem algebraically. 24

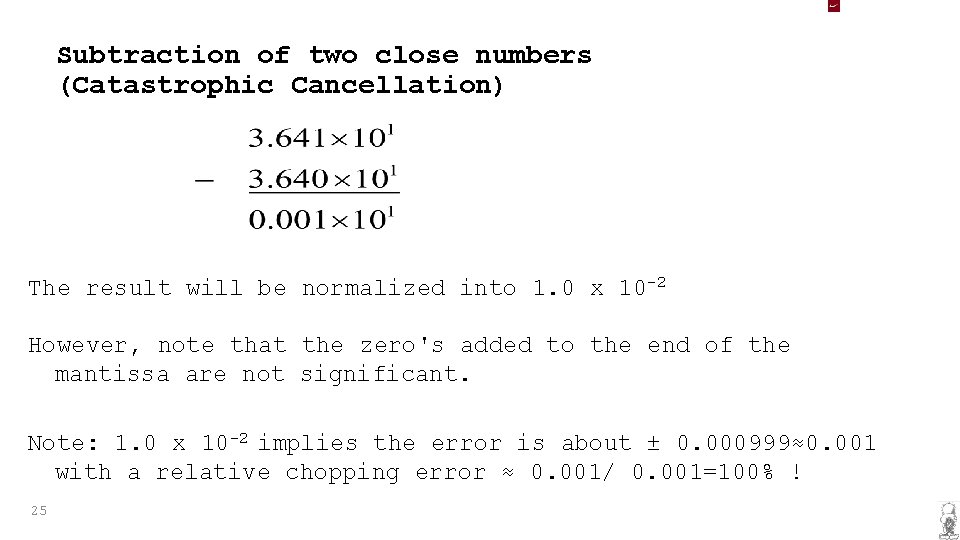

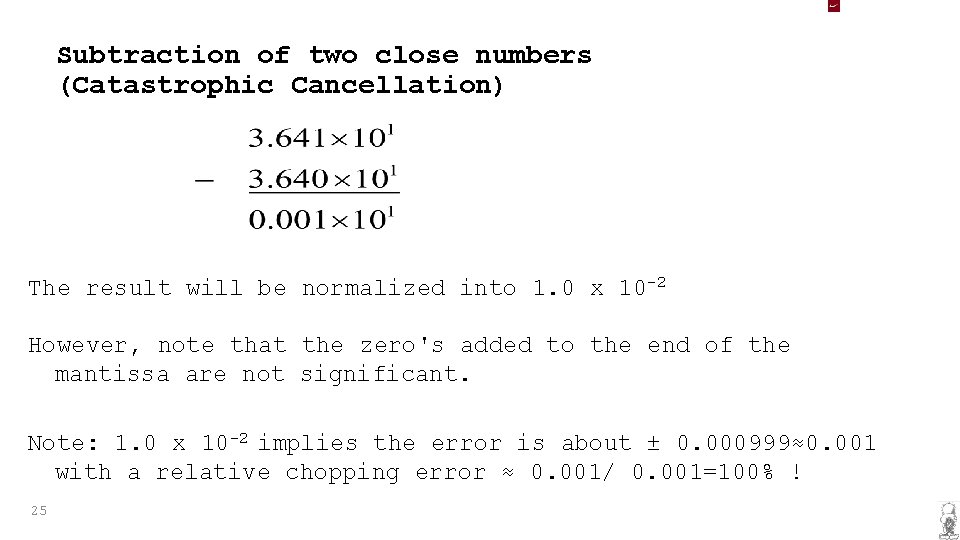

Subtraction of two close numbers (Catastrophic Cancellation) The result will be normalized into 1. 0 x 10 -2 However, note that the zero's added to the end of the mantissa are not significant. Note: 1. 0 x 10 -2 implies the error is about ± 0. 000999≈0. 001 with a relative chopping error ≈ 0. 001/ 0. 001=100% ! 25

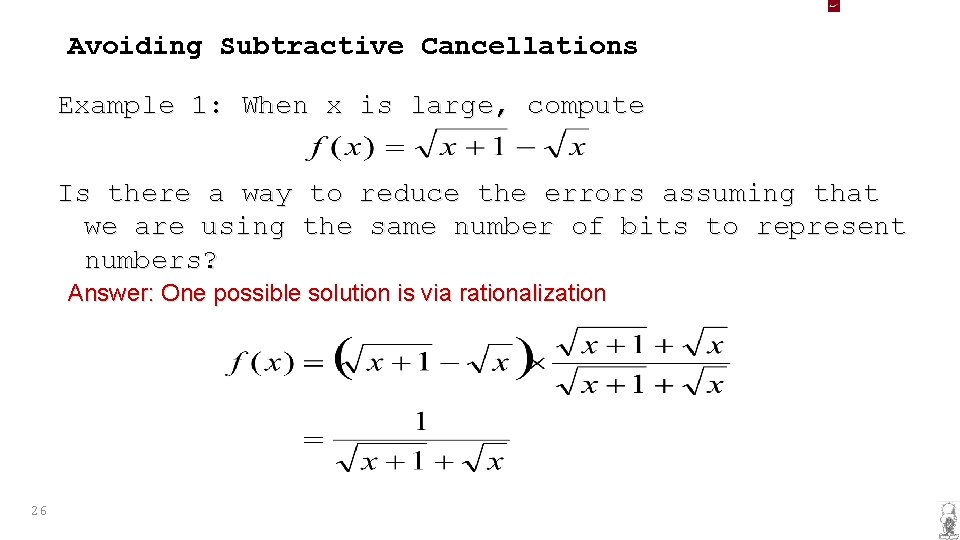

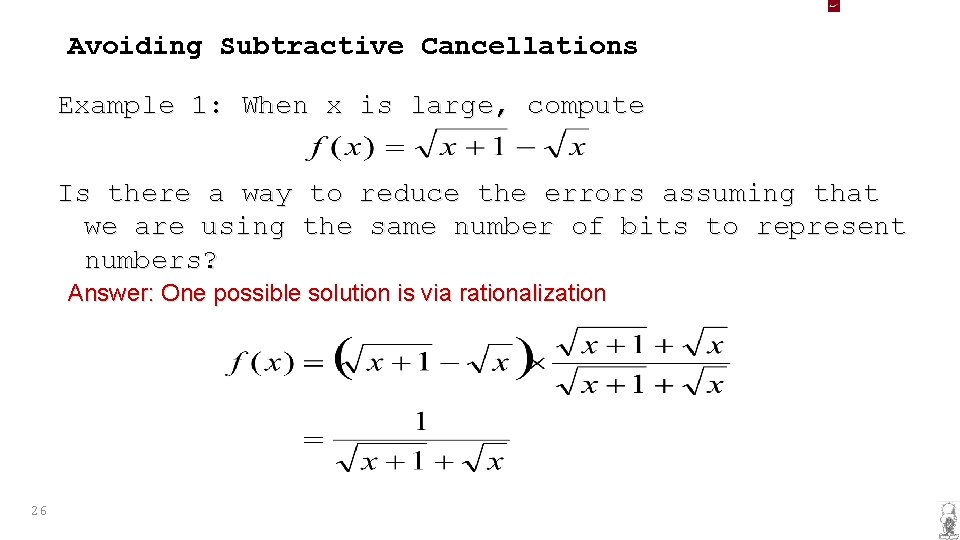

Avoiding Subtractive Cancellations Example 1: When x is large, compute Is there a way to reduce the errors assuming that we are using the same number of bits to represent numbers? Answer: One possible solution is via rationalization 26

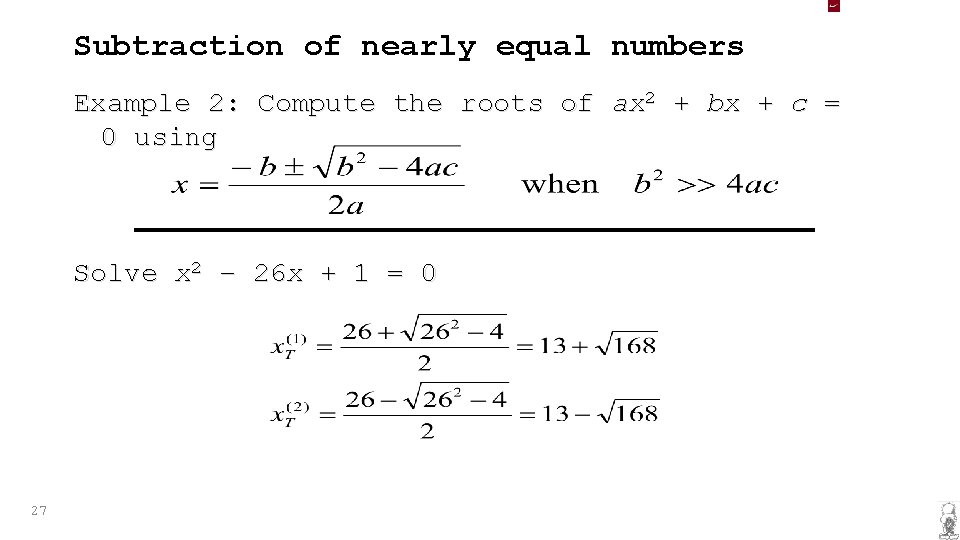

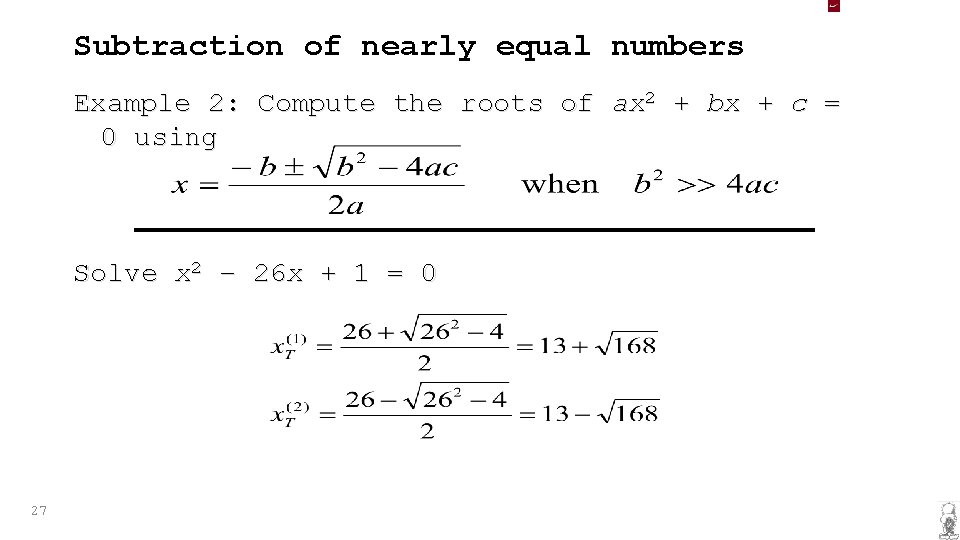

Subtraction of nearly equal numbers Example 2: Compute the roots of ax 2 + bx + c = 0 using Solve x 2 – 26 x + 1 = 0 27

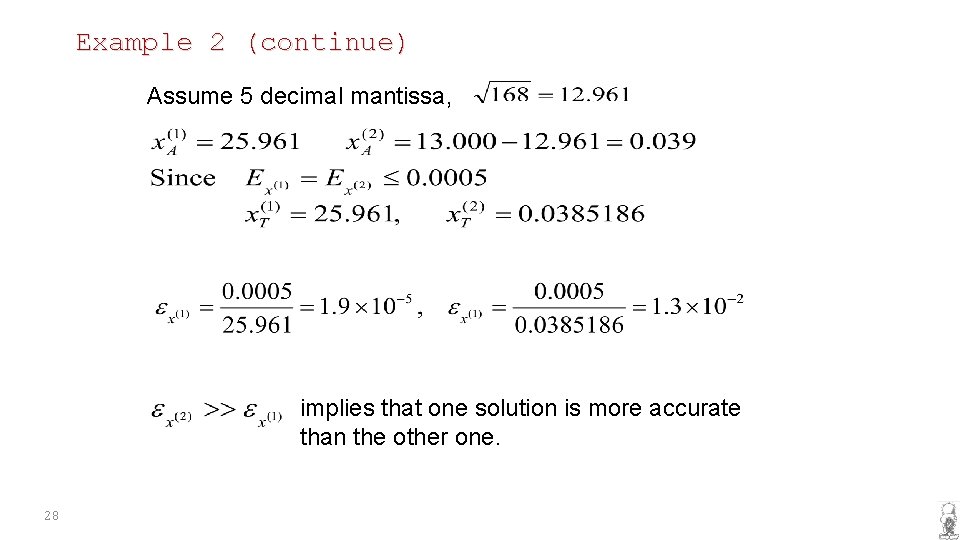

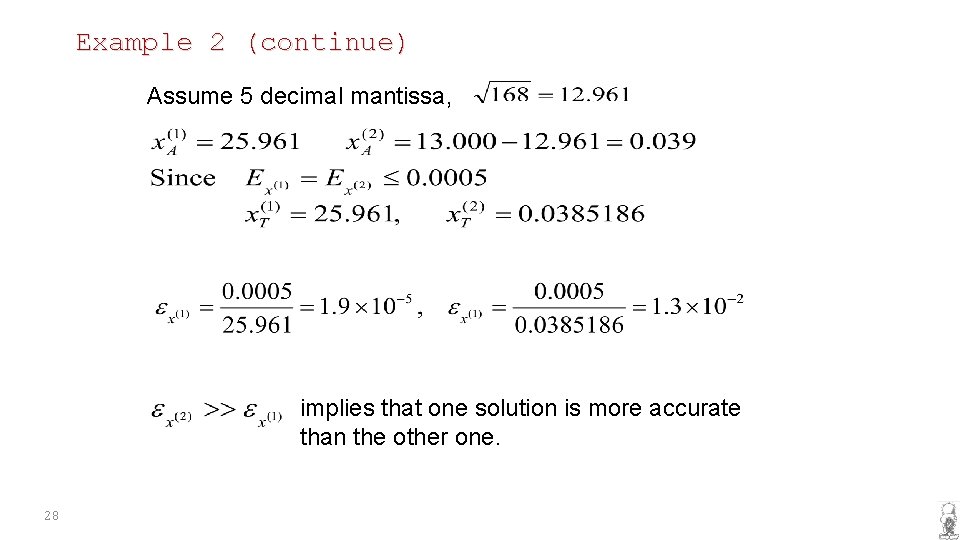

Example 2 (continue) Assume 5 decimal mantissa, implies that one solution is more accurate than the other one. 28

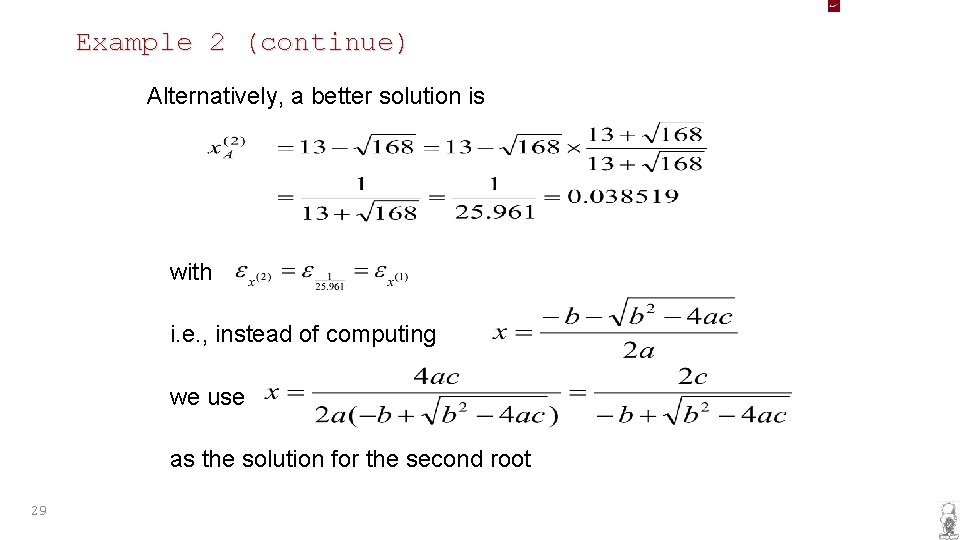

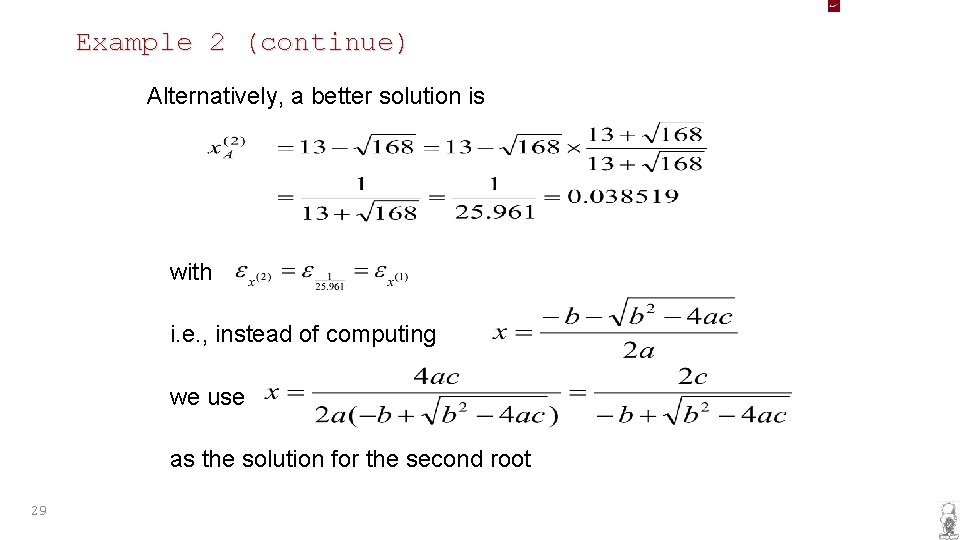

Example 2 (continue) Alternatively, a better solution is with i. e. , instead of computing we use as the solution for the second root 29

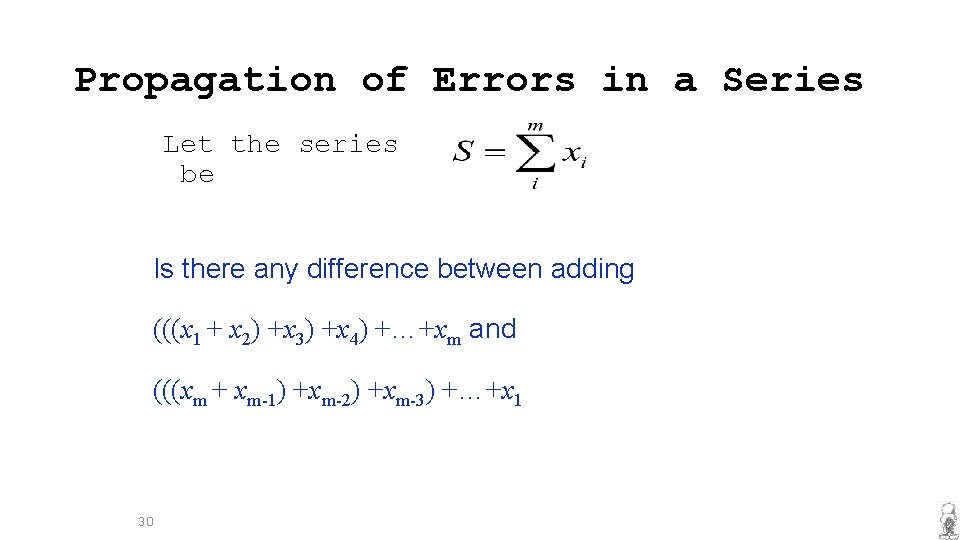

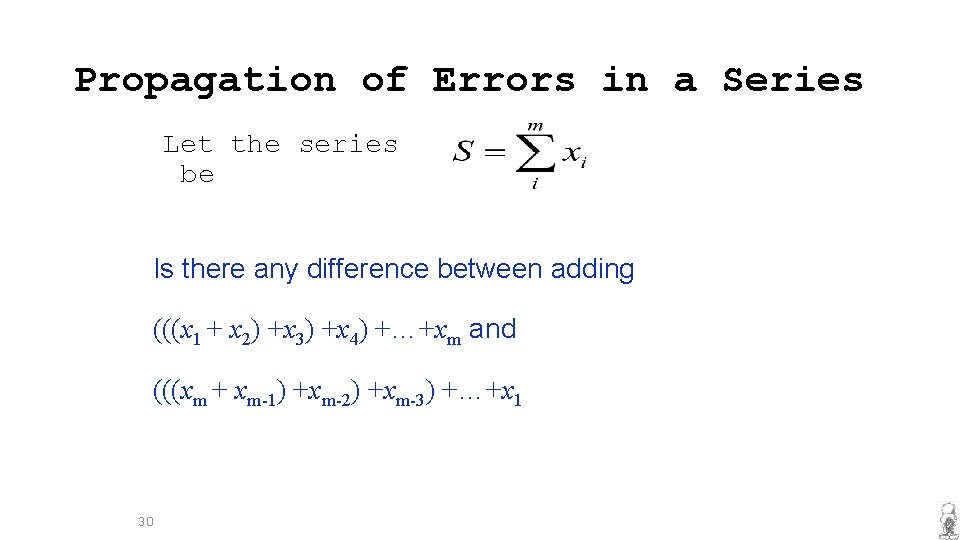

Propagation of Errors in a Series Let the series be Is there any difference between adding (((x 1 + x 2) +x 3) +x 4) +…+xm and (((xm + xm-1) +xm-2) +xm-3) +…+x 1 30

Example: #include <stdio. h> int main() { float sumx, x; float sumy, y; double sumz, z; int i; sumx = 0. 0; sumy = 0. 0; sumz = 0. 0; x = 1. 0; y = 0. 00001; z = 0. 00001; 31 for (i sumx sumy sumz } = = 0; i sumx sumy sumz < + + + 100000; i++) { x; y; z; printf("%sumx = %fn", sumx); printf("%sumy = %fn", sumy); printf("%sumz = %fn", sumz); return 0; } Output: sumx = 1000000 sumy = 1. 000990 sumz = 0. 999999808375506

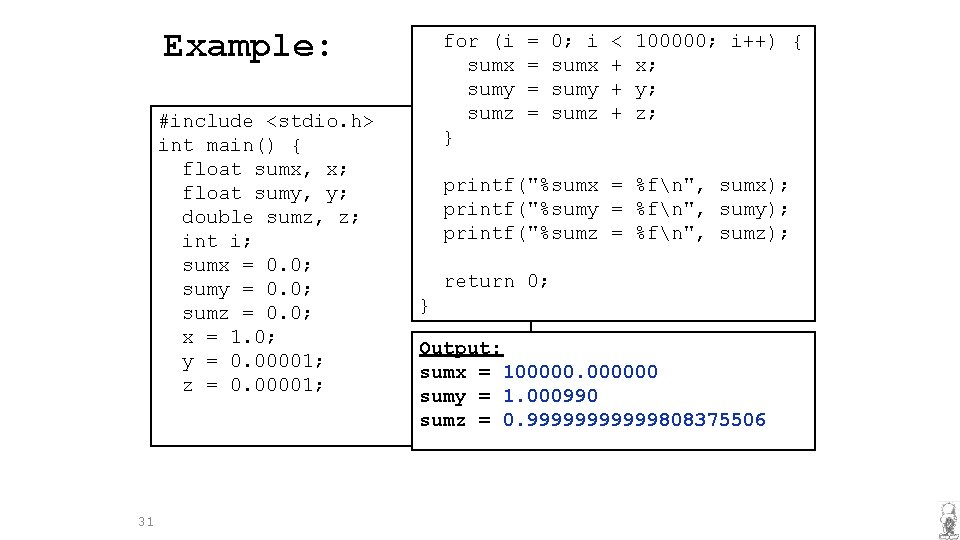

Characters • Char – ascii 7 bits : • • Letters Digits Special characters Control characters • 8 bits codepages: languages • Unicode and UTF 8 unsigned char i; for ( i=32; i<128; i++) printf("%dt%xt%cn", i, i, i); 32 32 33 34 35 36 20 21 22 23 24 ! " # $

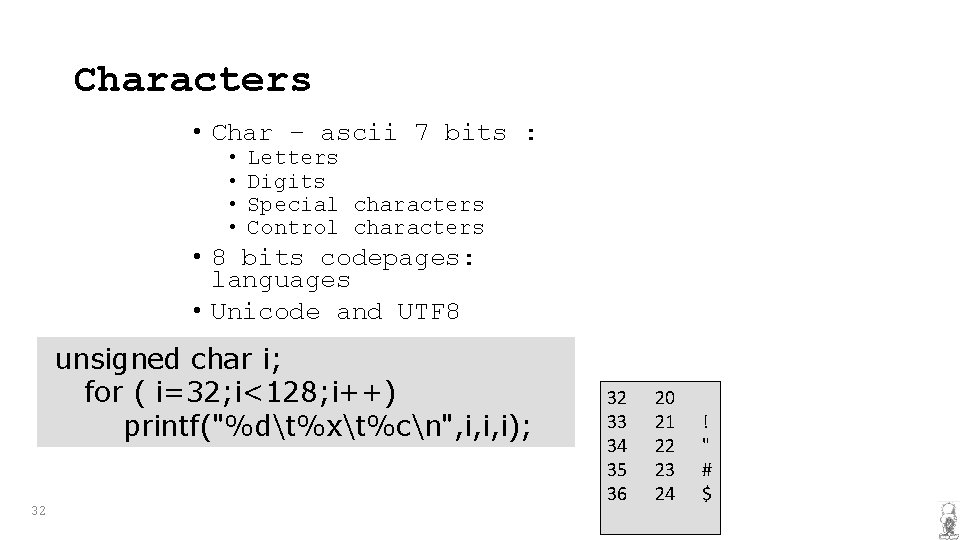

Arrays § Elementary data structure that exists as built-in in most programming languages. main( int argc, char** argv ) { int x[6]; int j; for(j=0; j < 6; j++) x[j] = 2*j; }

![Arrays in C int list5 plist5 list5 five integers list0 list1 list2 list3 list4 Arrays in C int list[5], *plist[5]; list[5]: five integers list[0], list[1], list[2], list[3], list[4]](https://slidetodoc.com/presentation_image_h2/7bba5c77cab6737f8ba24d713b99e176/image-34.jpg)

Arrays in C int list[5], *plist[5]; list[5]: five integers list[0], list[1], list[2], list[3], list[4] *plist[5]: five pointers to integers plist[0], plist[1], plist[2], plist[3], plist[4] implementation of 1 -D array list[0] base address = list[1] + sizeof(int) list[2] + 2*sizeof(int) list[3] + 3*sizeof(int) list[4] + 4*size(int)

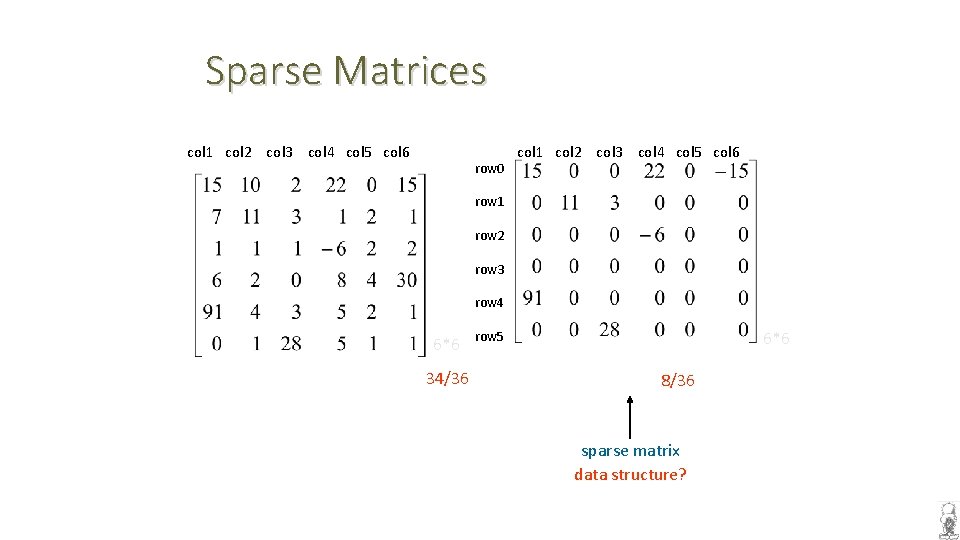

The Array Abstract Data Type • Array is a container which holds a fixed number of logically contiguous Homogenous items. Terms associated: • Element − Each item stored in an array is called an element. • Index − Each location of an element in an array has a numerical index, which is used to identify the element. • The basic function on arrays is get address of element[index] • If SA is the start address of <type> array[] of N elements, the address of array[i] is: SA+size(type>)*i in C syntax SA =array= &array[0] and SA+size(type)*i = array+i So: *(array+i)=array[i] 35

![Example int one 0 1 2 3 4 Goal print out address and Example: int one[] = {0, 1, 2, 3, 4}; //Goal: print out address and](https://slidetodoc.com/presentation_image_h2/7bba5c77cab6737f8ba24d713b99e176/image-36.jpg)

Example: int one[] = {0, 1, 2, 3, 4}; //Goal: print out address and value void print 1(int *ptr, int rows) { printf(“Address t. Contentsn”); for (i=0; i < rows; i++) printf(“%8 u%5 dn”, ptr+i, *(ptr+i)); printf(“n”); }

![Arrays in C contd Compare int list 1 and int list 25 in C Arrays in C (cont’d) Compare int *list 1 and int list 2[5] in C.](https://slidetodoc.com/presentation_image_h2/7bba5c77cab6737f8ba24d713b99e176/image-37.jpg)

Arrays in C (cont’d) Compare int *list 1 and int list 2[5] in C. Same: list 1 and list 2 are pointers. Difference: list 2 reserves five locations. Notations: list 2 - a pointer to list 2[0] (list 2 + i) - a pointer to list 2[i] (&list 2[i]) *(list 2 + i) - list 2[i]

![Addressing ith element in N dimensional arrays Address aij in aNM is S Addressing ith element in N dimensional arrays • Address a[i][j] in a[N][M] is S](https://slidetodoc.com/presentation_image_h2/7bba5c77cab6737f8ba24d713b99e176/image-38.jpg)

Addressing ith element in N dimensional arrays • Address a[i][j] in a[N][M] is S +s(i*M+j) • in C a+i*m+j • FOR: array A[N 1 ][N 2 ]…[Nd ] with dimensions N 1 *N 2 * N 3 …*Nd ; Nk (k=1. . . d); index of A[n 1] [n 2]…[nd] is (row-major) (column-major)

![Row Major int a44 0 1 2 3 4 5 39 Row Major int a[4][4] ={{0, 1, 2, 3}, {4, 5, …. }} 39](https://slidetodoc.com/presentation_image_h2/7bba5c77cab6737f8ba24d713b99e176/image-39.jpg)

Row Major int a[4][4] ={{0, 1, 2, 3}, {4, 5, …. }} 39

![Column Major int a44 0 1 2 3 4 5 40 Column Major int a[4][4] ={{0, 1, 2, 3}, {4, 5, …. }} 40](https://slidetodoc.com/presentation_image_h2/7bba5c77cab6737f8ba24d713b99e176/image-40.jpg)

Column Major int a[4][4] ={{0, 1, 2, 3}, {4, 5, …. }} 40

![Array int A234 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 Array • int A[2][3][4] = {{{1, 2, 3, 4}, {5, 6, 7, 8}, {9,](https://slidetodoc.com/presentation_image_h2/7bba5c77cab6737f8ba24d713b99e176/image-41.jpg)

Array • int A[2][3][4] = {{{1, 2, 3, 4}, {5, 6, 7, 8}, {9, 10, 11, 12}}, {{13, 14, 15, 16}, {17, 18, 19, 20}, {21, 22, 23, 24}}}; • Single operation: Access element indexed i For read or write • What is the difference between: • int c[10][20] and int *c[10] • int *c and int c[] 41

![Rectangular vs Jagged matrices int ar105 1054 bytes address of ar00ar ar2534 Rectangular vs. Jagged matrices • int ar[10][5] 10*5*4 bytes address of ar[0][0]=ar ar+(2*5+3)*4 •](https://slidetodoc.com/presentation_image_h2/7bba5c77cab6737f8ba24d713b99e176/image-42.jpg)

Rectangular vs. Jagged matrices • int ar[10][5] 10*5*4 bytes address of ar[0][0]=ar ar+(2*5+3)*4 • address of ar[2][3] = ar + 2*5 + 3 42 10 addresses (40 bytes) • int ar *[10] ar[0][0], ar[0][1], … ar[2][0], ar[2][1], … address of ar[2][3] = ar[2] + 3

![Explain 43 int a31 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 cout Explain 43 int a[][3]={{1, 2, 3}, {4, 5, 6}, {7, 8, 9}}; cout <<](https://slidetodoc.com/presentation_image_h2/7bba5c77cab6737f8ba24d713b99e176/image-43.jpg)

Explain 43 int a[][3]={{1, 2, 3}, {4, 5, 6}, {7, 8, 9}}; cout << a[0][4] <<endl; int *pt; pt=(int *)a; cout << pt <<" " << a << endl; cout << *pt << " " << *a << endl; cout << *(*a) << endl; cout << *(pt+2*3+1) << endl; char *ptc; int *pti; ptc=(char *)pt; pti=(int *) (ptc+(2*3+1)*sizeof(int) ); cout << *(pti) << endl; int r 1[]={1, 2, 3, 4}; int r 2[]={5, 6}; int *ar[]={r 1, r 2}; //Jagged cout << ar[0][4] << endl; 5 0 x 28 fedc 1 8 8 4273648

![Explain Code short x331 2 0 3 4 0 5 6 0 short y3 Explain Code short x[3][3]={{1, 2, 0}, {3, 4, 0}, {5, 6, 0}}; short *y[3];](https://slidetodoc.com/presentation_image_h2/7bba5c77cab6737f8ba24d713b99e176/image-44.jpg)

Explain Code short x[3][3]={{1, 2, 0}, {3, 4, 0}, {5, 6, 0}}; short *y[3]; y[0]=malloc(3*sizeof(short)); // Jagged array y[1]=malloc(2*sizeof(short)); y[2]=malloc(5*sizeof(short)); y[2][4]=777; printf("%dn", y[2][4]); 777 printf("%d %d", sizeof(x), sizeof(y)); 44 18 12

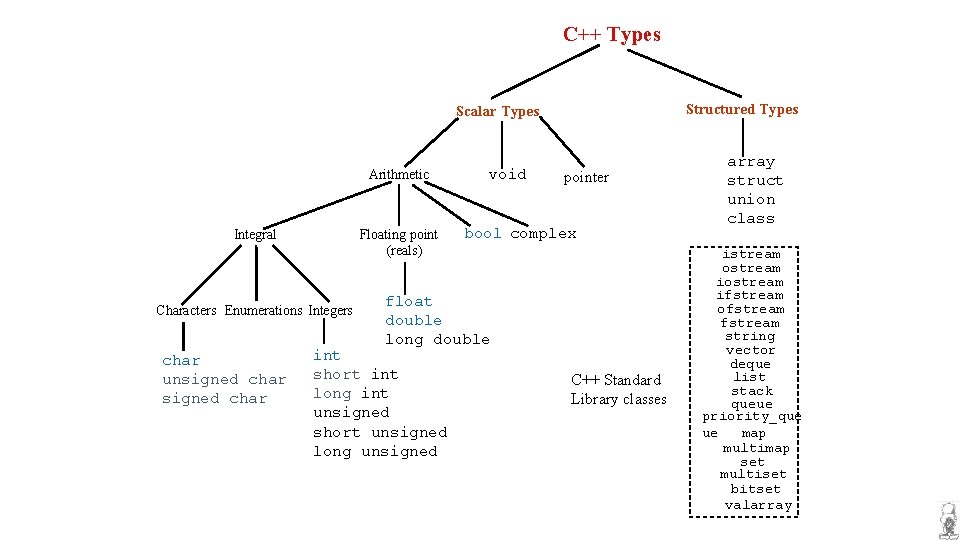

Sparse Matrices col 1 col 2 col 3 col 4 col 5 col 6 row 0 col 1 col 2 col 3 col 4 col 5 col 6 row 1 row 2 row 3 row 4 6*6 34/36 6*6 row 5 8/36 sparse matrix data structure?

![Representing Strings Null terminated C char str8HELLO Lengthprefixed Pascal Object Representing Strings • Null terminated (C) • char str[8]=“HELLO” • Length-prefixed (Pascal) • Object](https://slidetodoc.com/presentation_image_h2/7bba5c77cab6737f8ba24d713b99e176/image-46.jpg)

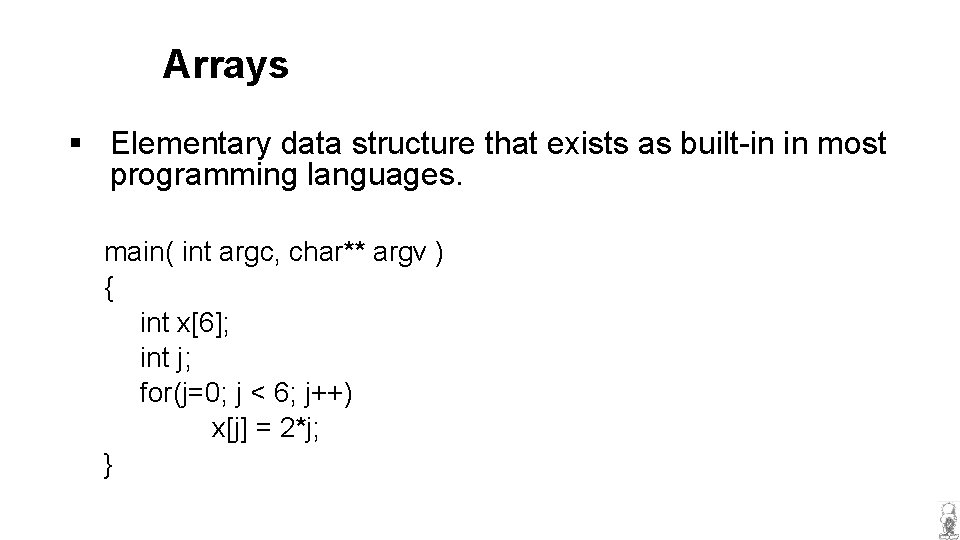

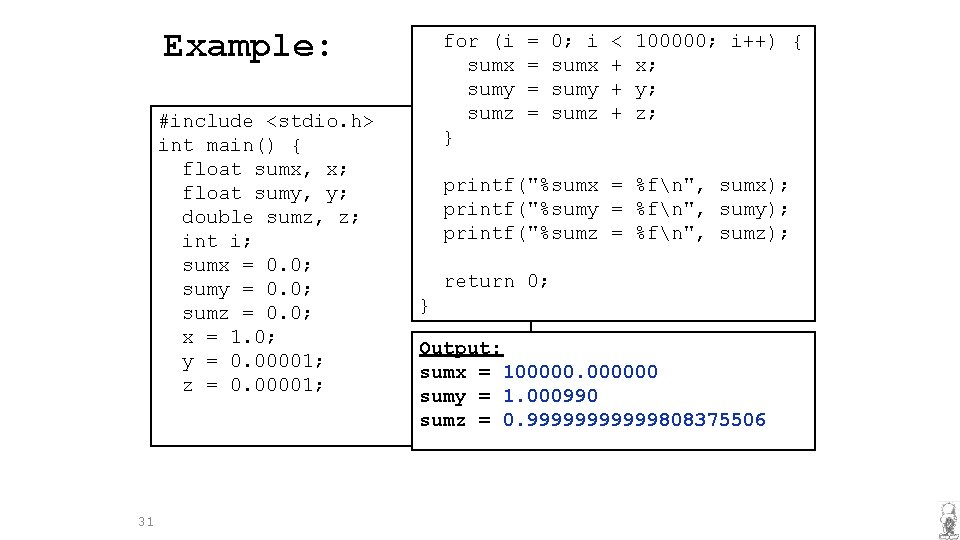

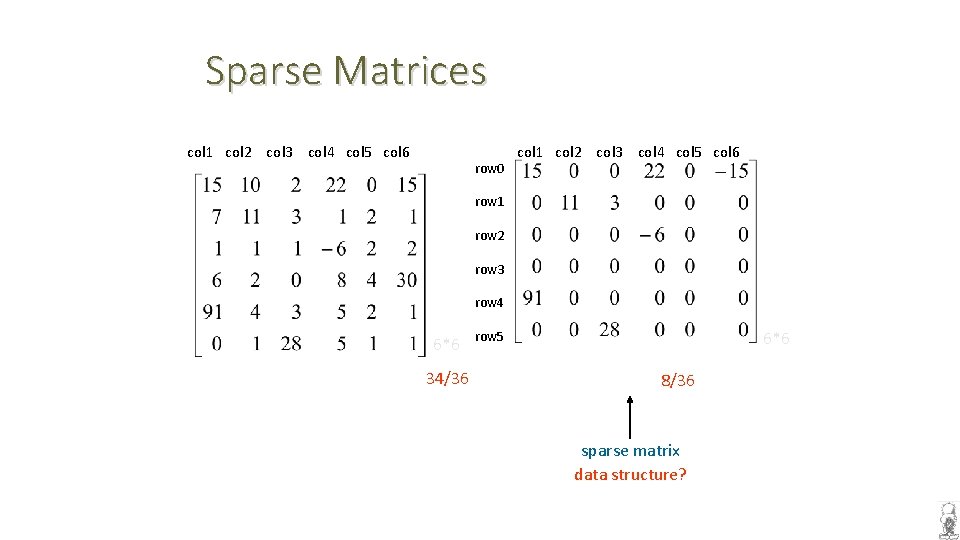

Representing Strings • Null terminated (C) • char str[8]=“HELLO” • Length-prefixed (Pascal) • Object Oriented (C++) ‘H’ ‘E’ ‘L’ ‘O’ 0 ? ? 5 ‘H’ ‘E’ ‘L’ ‘O’ • class string { int length; char *text; }; • Linked List (Haskel) ‘L’ 46 ‘O’ ‘H’ ‘E’ ‘L’