Primary Care of the Preterm Infant KAREN HUSSEIN

- Slides: 47

Primary Care of the Preterm Infant KAREN HUSSEIN, PGY-3

Goals and Objectives �Identify, understand manage the ongoing medical needs of the NICU graduate �Recognize the key role of the PCP in providing optimal continuity of treatment by coordinating transition of care from the neonatologist, providing direct medical care and facilitating ongoing care of the infant by subspecialists and other health professionals �Review of common screening topics and medical problems of the NICU graduate

Screening

Question #1 �A premature infant presents to your office for an initial visit after hospitalization. �What questions should be asked and topics should be covered in the initial hospital follow up visit then subsequent visits?

Initial Visit � NICU course � Current medications � Medical equipment Home oxygen Pulse oximetry Apnea and bradycardia monitor Ventilator Feeding pump � Growth parameters Current weight, length and head circumference as compared to at birth parameters � Vital signs � Nutrition Formula and kcal/oz Type of feeding (oral versus G-tube) Volume and frequency of feeds � Immunization record � Neonatal screening Metabolic and newborn screening Cranial imaging Hearing Ophthalmologic � Specific problems related to infant � Review of NICU discharge summary

Initial Visit �Evaluation of progress since discharge including growth �Time to listen and address the family’s concerns �Education for family about Medical diagnoses Cardiopulmonary resuscitation Any medications and/or equipment required in care �Review future appointments with subspecialty services , primary care visits and hearing and vision screening

Subsequent Visits �Timing depends on infant’s medical condition More frequent in the beginning to monitor and establish adequate growth �Focus on: Routine primary care (ie, immunizations) General care directed towards NICU graduate (ie, hearing, vision and development screening) Specific medical problems of the infant �Consistent care that provides continuity of information and psychosocial support to family

PREP Question #1 � A 24 -week-premature infant who is now 46 weeks of corrected gestational age is being seen in your office for concerns of decreasing oral intake and poor weight gain. The infant was discharged to home from the neonatal intensive care unit 2 weeks ago weighing 2, 400 grams. His medical problems include bronchopulmonary dysplasia that requires diuretics and gastroesophageal reflux that has been treated with omeprazole. The infant was sent home feeding a minimum of 45 m. L of premature formula concentrated to 27 calories per ounce orally every 3 hours using a slow flow nipple. At the first office visit 1 week ago, the infant weighed 2, 505 grams and was described as feeding slowly but taking the minimum volume of formula daily. Currently, the infant weighs 2, 610 g. The mother reports that the infant is feeding 35 to 45 m. L of formula every 3 hours. The mother describes her son as waking and hungry every 3 hours, although he often “shuts down” after 10 minutes of feeding and refuses to take more. The infant does not spit, arch, or turn red with feedings. He passes 2 soft, brown stools daily. The physical examination is otherwise unremarkable. When you observe a feeding, the infant has unlabored respiratory effort and maintains an oxygen saturation of 95%.

PREP Question #1 �Of the following, the MOST appropriate approach to help with the poor oral intake is to A. advance the caloric content of the formula B. change to a regular-flow nipple C. consult occupational therapy D. increase the diuretic dosage E. initiate oxygen via nasal cannula

Answer �C. consult occupational therapy �Consultation with an occupational therapist experienced with premature infants is recommended when feeding problems are identified in discharged premature infants. �Feeding problems are 7 times more common in infants born prematurely, with 33% of infants born at less than 26 weeks’ gestation having continued feeding issues at 30 months’ corrected gestational age.

Growth � At risk for inadequate growth due to increased caloric and nutrient requirements and feeding skills Swallowing problems Oral motor dysfunction Hypersensitivity Delayed feeding skill development Oral aversion problems � Plot growth curves and developmental milestones according to corrected age for the first two years of life � Initiate corrective measures Changes in the composition, volume, caloric density and mode of feeding � Evaluate for contributing conditions (ie, gastroesophageal reflux or feeding disorders) Prompt referral to a feeding specialist and/or nutritionist

Immunization �At increased risk for vaccine-preventable infections �AAP recommends that medically stable preterm infants should receive full immunization based upon their chronological age consistent with the schedule and dose recommended for full-term infants �May have been started in the NICU but delays are common, especially in unstable infants, so it is important to obtain an immunization record �Consider RSV prophylaxis with Palivizumab Please see dedicated CCC presentation for more details

PREP Question #2 �A 2 -year-old boy who has a history of premature birth has been diagnosed with hearing loss. He was born at 28 weeks’ gestation and required 2 weeks of mechanical ventilation. After discharge, he required home oxygen therapy for 3 months. His mother asks if any medications could have contributed to his hearing loss.

PREP Question #2 �Of the following, the medication exposure MOST likely to contribute to hearing loss is A. amphotericin B B. caffeine C. cefotaxime D. chlorothiazide E. furosemide

Answer � E. furosemide � The AAP Joint Committee on Infant Hearing Year 2007 position statement has identified risk factors for children with congenital or acquired hearing loss that include Neonatal Intensive Care Unit (NICU) hospitalization greater than 5 days, Extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO) Mechanical ventilation Hyperbilirubinemia requiring exchange transfusion Exposure to ototoxic medications, such as aminoglycosides (gentamicin and tobramycin) or loop diuretics (eg, furosemide) � Furosemide-induced ototoxicity can be either transient or permanent. � Aminoglycosides appear to potentiate the ototoxic effects of furosemide and, as such, it is recommended that efforts be made to avoid simultaneous use of aminoglycoside and loop diuretics.

Hearing �Estimated prevalence of bilateral sensorineural hearing loss is 1 -2 per 1000 newborns in the US, but is 10 -20 times higher among premature infants �Recommended to have automated auditory brainstem response as screening test for hearing �Follow up audiological evaluation during the first year of life or sooner if needed is critical to ensure the timely diagnosis on late-onset hearing loss �Infants with other risk factors, such as meningitis or cytomegalovirus, should have follow up testing performed soon after discharge

Vision �At increased risk for long-term ophthalmologic abnormalities including Retinopathy of prematurity (ROP) Strabismus Reduced visual acuity Myopia Amblyopia Anisometropia Retinal detachment

Neurodevelopment � At increased risk for developmental delays and disabilities Motor impairment and/or tone abnormalities Cerebral palsy Learning delay or disability Borderline low-average intelligence quotients (IQs) Autism or autism spectrum disorders Attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) Specific neuropsychological deficits (ie, visual motor integration, executive dysfunction) Behavior problems (ie, internalizing problems, social difficulties) � Risk is increased with decreasing gestational age � Need to identify and refer at-risk infants for further evaluation and early intervention services � Follow up with family to ensure infant is receiving appropriate services specific to developmental needs (PT, OT, ST for feeding, Early Steps)

Psychosocial Issues �Bringing home a NICU graduate can be very challenging to parents because of social, financial and psychological stresses �Siblings and spouses may feel neglected by the infant’s needs �Need to screen for these stressors �Provide support services Home health nursing visits Early child intervention services Support groups Social work services Child protective services

Car Seats and Beds �To prevent morbidity and mortality caused by motor vehicle accidents �Premature infants can be at increase risk for cardiopulmonary compromise while in car seats Greater decreases in oxygen saturation More frequent episodes of desaturation, bradycardia and apnea Greatest risk with infants with pre-discharge weights < 2000 g Need car seat challenge prior to discharge if at risk �Please see dedicated CCC presentation for more details

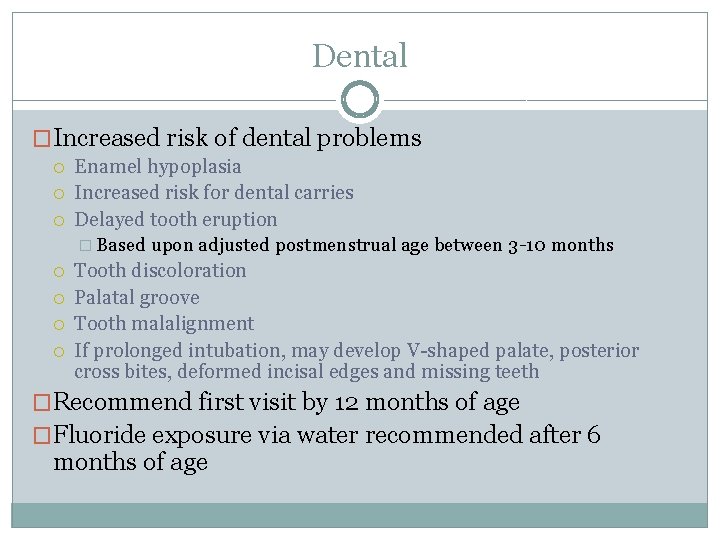

Dental �Increased risk of dental problems Enamel hypoplasia Increased risk for dental carries Delayed tooth eruption � Based upon adjusted postmenstrual age between 3 -10 months Tooth discoloration Palatal groove Tooth malalignment If prolonged intubation, may develop V-shaped palate, posterior cross bites, deformed incisal edges and missing teeth �Recommend first visit by 12 months of age �Fluoride exposure via water recommended after 6 months of age

Common Problems of the NICU Graduate

PREP Question #3 �A mother brings her 7 -week-old infant in for his first health supervision visit after being discharged from the neonatal intensive care unit. The infant was delivered at 31 weeks’ gestation because of placental abruption. He was intubated for 4 days after delivery and received 3 doses of surfactant for respiratory distress syndrome. He subsequently required oxygen by high flow nasal cannulae for 1 week. He has been in room air since that time and results of his chest radiograph are normal. His mother is worried that her infant has moderate to severe chronic lung disease.

PREP Question #3 �Of the following, the MOST appropriate information to provide to the mother is that infants who have chronic lung disease A. are born at less than or equal to 26 weeks’ gestation B. have chest radiographs with severe fibrosis and hyperventilation C. have received a minimum of 5 days of assisted ventilation D. maintain normal postnatal lung development E. require supplemental oxygen at 36 weeks’ corrected gestation

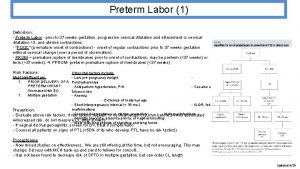

Answer �E. require supplemental oxygen at 36 weeks’ corrected gestation �The most commonly used definition of the “new BPD, ” currently referred to as chronic lung disease (CLD), is the requirement of oxygen at 36 weeks’ corrected gestation. �With the improvement in ventilator management and the incorporation of therapeutic modalities such as prenatal corticosteroids and surfactants into daily practice, the underlying mechanism for CLD is believed to be an arrest of normal lung development due to premature birth. �The radiographs of CLD often do not reveal the fibrosis and hyperinflation that was characteristic of infants diagnosed with BPD in the past.

Respiratory � Most common problem is bronchopulmonary dysplasia (BPD) or chronic lung disease (CLD) of prematurity Respiratory disease with requirement of supplemental oxygen at 36 weeks postmenstrual age and persistent abnormalities on chest radiographs At discharge, baseline studies include respiratory and heart rate, blood pressure, oxygen requirement, chest radiograph and echocardiogram to assess for presence of pulmonary hypertension May continue to require supplemental oxygen, medications (ie, diuretics, electrolyte supplements and bronchodilators) and increased caloric needs Most often allowed to outgrow diuretic dose and slow wean of home oxygen Morbidities include acute respiratory exacerbations, pulmonary edema, upper and lower respiratory tract infections, cardiac problems (ie, cor pulmonale and pulmonary hypertension) and growth failure Typically improves by two years of age � At risk for reactive airway disease and respiratory infections (ie, RSV and other virus or bacterial infections) � Be alert for late-onset sequelae of prolonged intubation (subglottic stenosis)

Apnea of Prematurity �Approximately in 25% of premature infants �Most outgrow by postmenstrual age of 40 weeks �Some will continue to have apnea and may be discharge home on methylxanthine therapy (ie, caffeine) or apnea monitors �Timing to discontinue these interventions is multifactorial, usually determined by the subspecialist or NICU follow up clinic

Question #2 �What is the second most common cause of childhood blindness?

Retinopathy of Prematurity � Second most common cause of childhood blindness � Treatment can reduce morbidity � Indicated in all infants with birth weight < 1500 g or gestational age less than 31 weeks � Also indicated in infants whose clinical course places them at increased risk as determined by the neonatologist � Typically presents at approximately 32 weeks gestation � Peaks at 38 to 40 weeks � Beings to regress by 46 weeks � Initial retinal screening 4 -6 weeks after birth � Additional examinations at intervals of 1 -3 weeks until retinal vessels have fully matured

PREP Question #4 �You are the primary care physician for newborn twins born at 33 weeks’ gestation and discharged from the neonatal intensive care unit after a 4 -week stay. They required oxygen for 3 days after birth, but little other respiratory support. They were diagnosed with gastroesophageal reflux disease. They have occasional episodes of coughing and gagging without color change. They are otherwise well.

PREP Question #4 �Of the following, the BEST advice to give the parents is to place the twins in A. prone sleep position B. side sleep position C. sitting devices, such as car seats, during sleep D. sleep positioners to keep their heads elevated E. supine sleep position

Answer �E. supine sleep position �Except in a very few instances, supine is the safest sleep position for an infant including those with gastroesophageal reflux. �The safest place for an infant to sleep is on a firm, wellfitted mattress in an approved crib, bassinet, or play yard free of other objects and located in the parents’ room. �Current American Academy of Pediatrics recommendations extend beyond “Back to Sleep” to address other sleep environment factors. �Bed sharing, while controversial, is not recommended, and even twins should sleep on separate sleep surfaces.

Sudden Infant Death Syndrome (SIDS) �Death of an infant less than one year of age that remains unexplained despite a thorough investigation �At greater risk than term infants with a peak risk at 50 -52 weeks postmenstrual age �No evidence that home apnea monitors decrease the risk �Screen at each visit to ensure families are following AAP recommendations of supine (back) sleeping position and ask about location of sleeping

Gastroesophageal Reflux �Common in premature infants and in those with CLD, neurological impairment or congenital defects (ie, tracheoesophageal fistulas or diaphragmatic hernias) �Monitor for complications including Poor weight gain due to decreased caloric intake Apnea and bradycardia Aspiration Choking Esophagitis Laryngospasms Discomfort

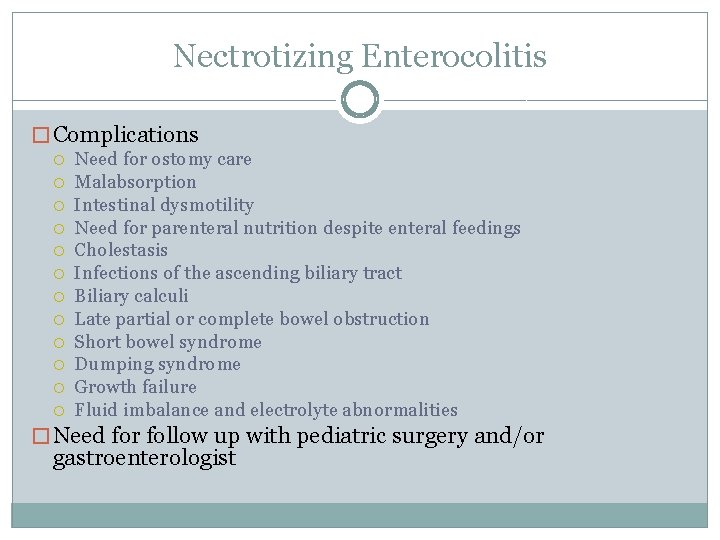

Nectrotizing Enterocolitis � Complications Need for ostomy care Malabsorption Intestinal dysmotility Need for parenteral nutrition despite enteral feedings Cholestasis Infections of the ascending biliary tract Biliary calculi Late partial or complete bowel obstruction Short bowel syndrome Dumping syndrome Growth failure Fluid imbalance and electrolyte abnormalities � Need for follow up with pediatric surgery and/or gastroenterologist

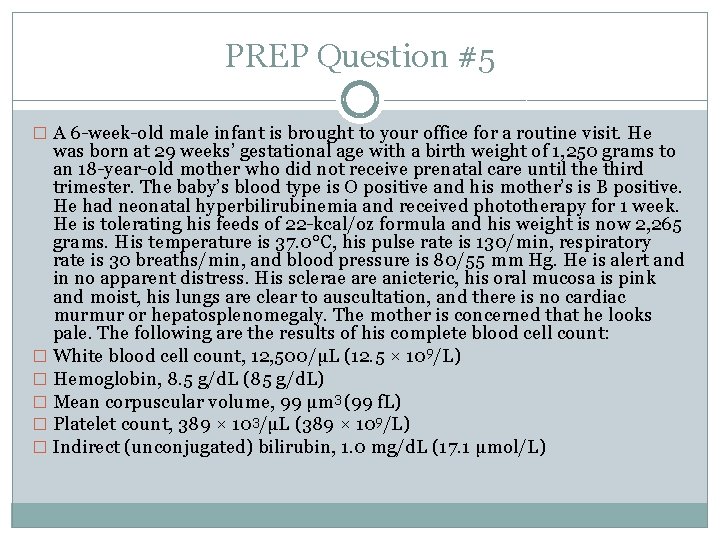

PREP Question #5 � A 6 -week-old male infant is brought to your office for a routine visit. He was born at 29 weeks’ gestational age with a birth weight of 1, 250 grams to an 18 -year-old mother who did not receive prenatal care until the third trimester. The baby’s blood type is O positive and his mother’s is B positive. He had neonatal hyperbilirubinemia and received phototherapy for 1 week. He is tolerating his feeds of 22 -kcal/oz formula and his weight is now 2, 265 grams. His temperature is 37. 0°C, his pulse rate is 130/min, respiratory rate is 30 breaths/min, and blood pressure is 80/55 mm Hg. He is alert and in no apparent distress. His sclerae are anicteric, his oral mucosa is pink and moist, his lungs are clear to auscultation, and there is no cardiac murmur or hepatosplenomegaly. The mother is concerned that he looks pale. The following are the results of his complete blood cell count: � White blood cell count, 12, 500/μL (12. 5 × 109/L) � Hemoglobin, 8. 5 g/d. L (85 g/d. L) � Mean corpuscular volume, 99 μm 3 (99 f. L) � Platelet count, 389 × 103/μL (389 × 109/L) � Indirect (unconjugated) bilirubin, 1. 0 mg/d. L (17. 1 μmol/L)

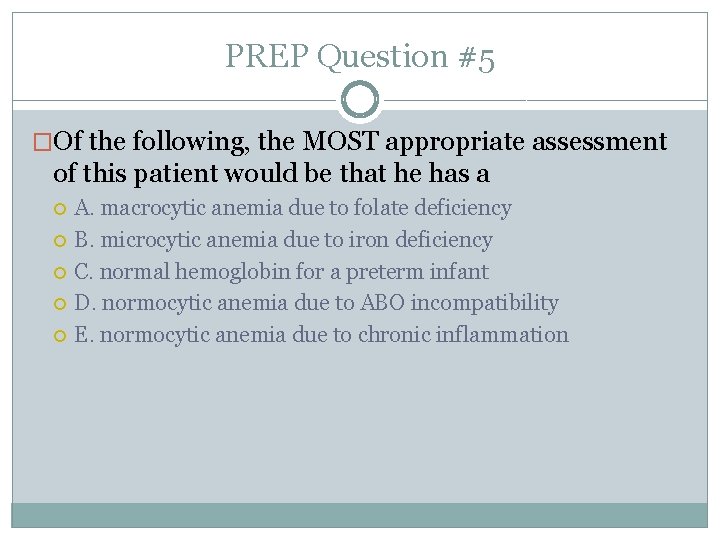

PREP Question #5 �Of the following, the MOST appropriate assessment of this patient would be that he has a A. macrocytic anemia due to folate deficiency B. microcytic anemia due to iron deficiency C. normal hemoglobin for a preterm infant D. normocytic anemia due to ABO incompatibility E. normocytic anemia due to chronic inflammation

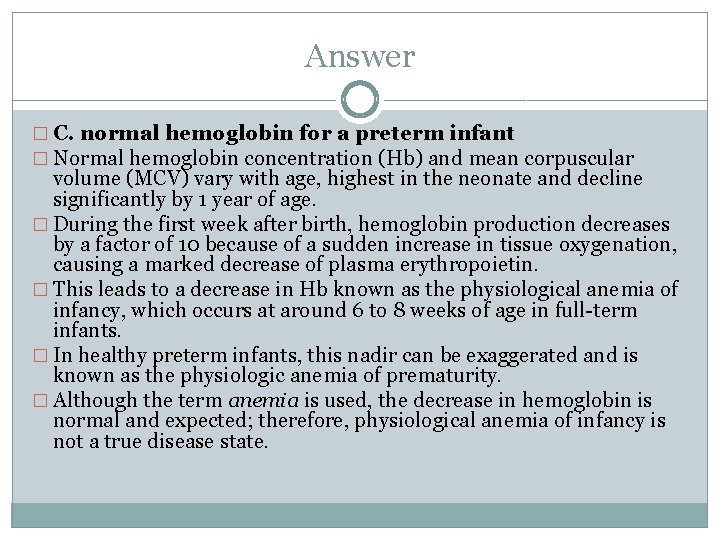

Answer � C. normal hemoglobin for a preterm infant � Normal hemoglobin concentration (Hb) and mean corpuscular volume (MCV) vary with age, highest in the neonate and decline significantly by 1 year of age. � During the first week after birth, hemoglobin production decreases by a factor of 10 because of a sudden increase in tissue oxygenation, causing a marked decrease of plasma erythropoietin. � This leads to a decrease in Hb known as the physiological anemia of infancy, which occurs at around 6 to 8 weeks of age in full-term infants. � In healthy preterm infants, this nadir can be exaggerated and is known as the physiologic anemia of prematurity. � Although the term anemia is used, the decrease in hemoglobin is normal and expected; therefore, physiological anemia of infancy is not a true disease state.

Anemia of Prematurity �At risk for anemia that occurs earlier and is more severe than physiologic anemia in term infants �Nadir for hemoglobin is 7 -10 g/d. L at 4 -8 weeks compared with 11 g/d. L at 8 -12 weeks in term infants �Treatment with iron supplementation (2 mg/kg/day or in multivitamin) results in lower rate of iron deficiency and iron deficiency anemia �Less additional supplementation needed if receiving iron-fortified formula versus exclusively breastfeeding �Symptomatic infants need red blood cell transfusion

Neurologic � Intraventricular hemorrhage (IVH), grades I-IV � Posthemorrhagic hydrocephalus occurs in 35% of infants with IVH and risk increases with severity (ie, grades III and IV) Early or late-onset Obstructive, communicating or both Transient or sustained Slow or rapid progression Shunt placement may be required with need for monitoring for malfunction or infection � Postmeningitic hydrocephalus � Periventricular leukomalacia Ischemic infarction of the white matter, most commonly adjacent to lateral ventricle � Seizures Common etiologies: hypoxic-ischemic injury, direct cerebral trauma, intracranial hemorrhage, metabolic abnormalities, malformations and infections

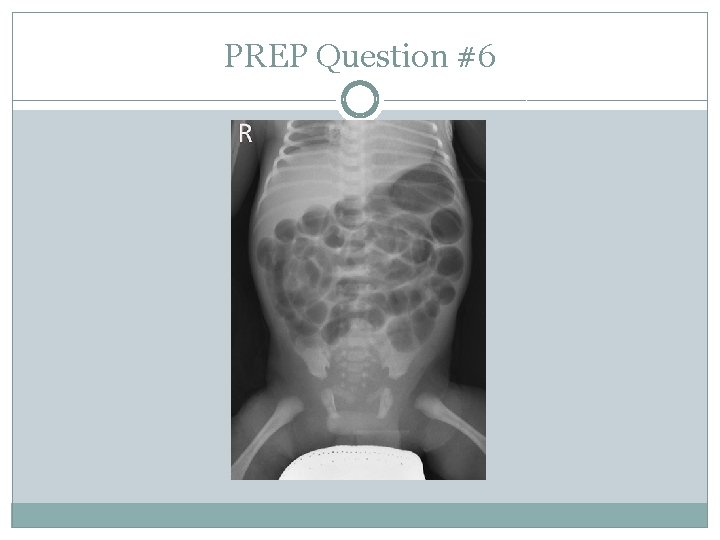

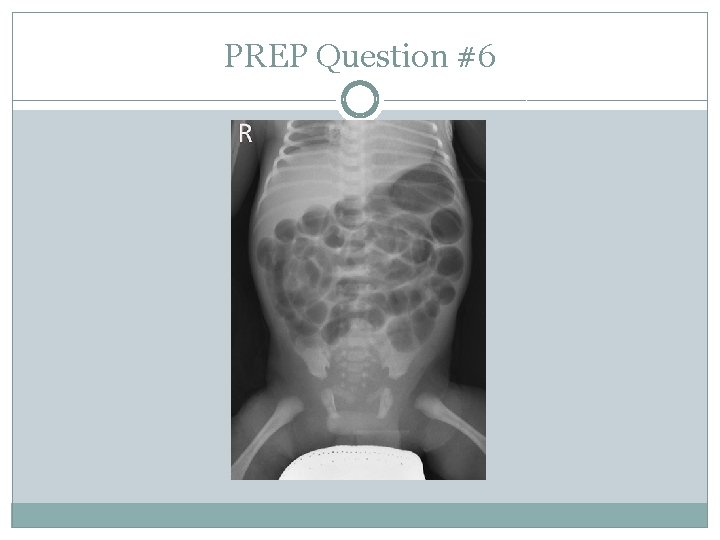

PREP Question #6 �An infant develops abdominal distention and bilious vomiting at 36 hours after birth. The 3. 9 -kg infant was born at 37 weeks of gestation to a mother with type 1 diabetes mellitus. The prenatal course was unremarkable, with negative carrier testing for cystic fibrosis. According to the mother, the infant has been breastfeeding and has had 4 wet diapers and 1 small smear of meconium. Examination reveals an uncomfortable infant with a distended, firm abdomen that is slightly tender to deep palpation. The rectum appears to be externally patent with an anal wink. A radiograph is obtained.

PREP Question #6

PREP Question #6 �Of the following, the MOST likely cause of the infant’s findings is A. anorectal malformation B. Hirschsprung disease C. meconium ileus D. neonatal small left colon syndrome E. pneumatosis coli

Answer �D. neonatal small left colon syndrome �An infant of a diabetic mother is at risk for hypoglycemia, hypocalcemia, polycythemia and neonatal small left colon syndrome.

Question #3 �What are some of the common surgical procedures performed on infants in the NICU?

Common Surgical Procedures �Surgical bowel resection secondary to necrotizing enterocolitis (NEC) and/or intestinal perforation �Gastrostomy tube placement �Fundoplication �Ventriculo-peritoneal shunts �Tracheostomy �Cardiac surgeries �Umbilical hernia repair due to incarceration �Inguinal hernia repair �Discuss care for surgical areas and follow up with surgical specialties

References � Committee on Fetus and Newborn (2008). Policy statement: Hospital discharge of the high-risk neonate. Pediatrics, 122(5), 1119 -1126. � Stewart, J. (2014). Care of the neonatal intensive care unit graduate. Retrieved from http: //www. uptodate. com. � Woods, S. & Riley, P. (2006). A role for community health care providers in neonatal follow-up. Paediatr Child Health; 11(5), 301 -302. � Andrews, B. , Pellertie, M. , Myers, P. & Hagerman, J. (2014). NICU follow-up: Medical and developmental management age 0 to 3 years. Neoreviews, 15(4), e 123 -e 132. � Sherman, M. P. (2013). Follow-up of the NICU patient. Retrieved from http: //emedicine. medscape. com/. � AAP PREP Questions

Karen hussein

Karen hussein Modified sims position for prolapsed cord

Modified sims position for prolapsed cord Primary secondary tertiary medical care

Primary secondary tertiary medical care Cervical length chart in mm

Cervical length chart in mm Chapter 13 preterm and postterm newborns

Chapter 13 preterm and postterm newborns Preterm labor nursing management

Preterm labor nursing management Amniotic fluid leakage images

Amniotic fluid leakage images Duvadilan drip preterm labour

Duvadilan drip preterm labour Neonatal resuscitation

Neonatal resuscitation Saguaro infant care and preschool

Saguaro infant care and preschool Infant oral health care

Infant oral health care Infant oral health care

Infant oral health care Hussein bey

Hussein bey Taha hussein challenges

Taha hussein challenges Laila hussein

Laila hussein Hussein al baya

Hussein al baya Uct computer science

Uct computer science Hussein suleman

Hussein suleman Hussein suleman

Hussein suleman Reporaproblem

Reporaproblem Dr. hussein shaqra

Dr. hussein shaqra Mbbsch

Mbbsch Hussein suleman

Hussein suleman Bassam hussein

Bassam hussein Bismillah hir rahman ir rahim alhamdulillahi rabbil alamin

Bismillah hir rahman ir rahim alhamdulillahi rabbil alamin Amina alifatik

Amina alifatik Emptiness

Emptiness Hussein mahmood 1985

Hussein mahmood 1985 Ananda sabil hussein

Ananda sabil hussein Saddam hussein

Saddam hussein Violence

Violence Advantages of selective primary health care

Advantages of selective primary health care Mbbsch

Mbbsch Saddam hussein

Saddam hussein Dr hussein saad

Dr hussein saad George h w bush apush

George h w bush apush Nadya hussein

Nadya hussein Hart plain infant school

Hart plain infant school The webinar will begin shortly

The webinar will begin shortly The infant industry argument

The infant industry argument Counter clockwise

Counter clockwise Keeping an infant safe and well section 7-3

Keeping an infant safe and well section 7-3 Equation

Equation Compression depth for child

Compression depth for child What is 90 degree angle for injection

What is 90 degree angle for injection Assessment of pain

Assessment of pain Newborn bilirubin levels chart

Newborn bilirubin levels chart Death rate formula

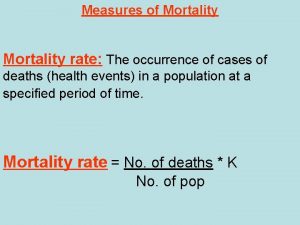

Death rate formula