Predicate Calculus Representing meaning 1 Revision Firstorder predicate

- Slides: 24

Predicate Calculus Representing meaning 1

Revision • • First-order predicate calculus Typical “semantic” representation Quite distant from syntax But still clearly a linguistic level of representation (it uses words, sort of) 2

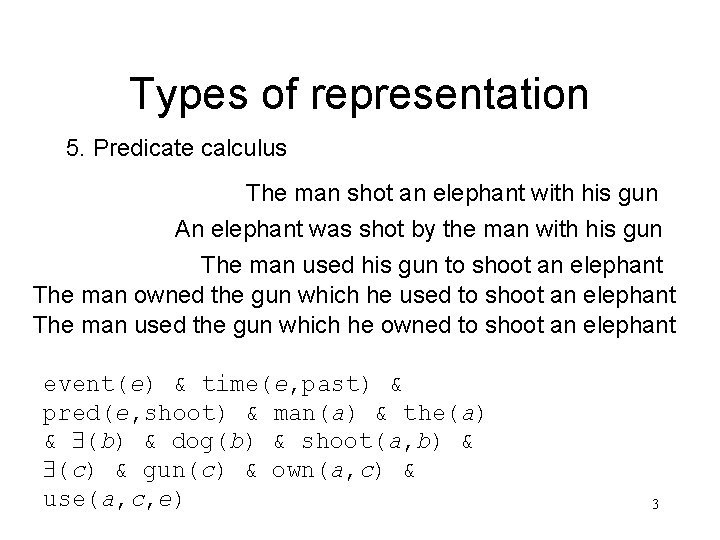

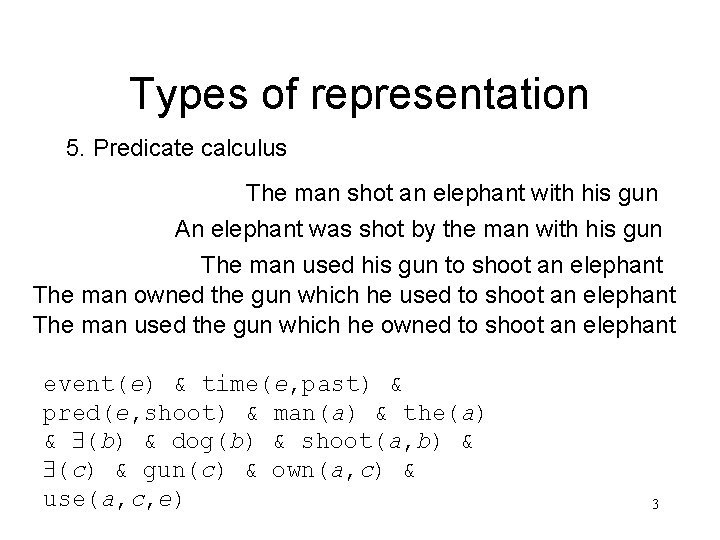

Types of representation 5. Predicate calculus The man shot an elephant with his gun An elephant was shot by the man with his gun The man used his gun to shoot an elephant The man owned the gun which he used to shoot an elephant The man used the gun which he owned to shoot an elephant event(e) & time(e, past) & pred(e, shoot) & man(a) & the(a) & (b) & dog(b) & shoot(a, b) & (c) & gun(c) & own(a, c) & use(a, c, e) 3

First-order predicate calculus • Computationally tractable • Well understood, mathematically sound • Therefore useful for inferencing, expressing equivalence • Can be made quite shallow (almost like a deep structure), or quite abstract • Good for expressing facts and relations • Therefore good for question-answering, information retrieval 4

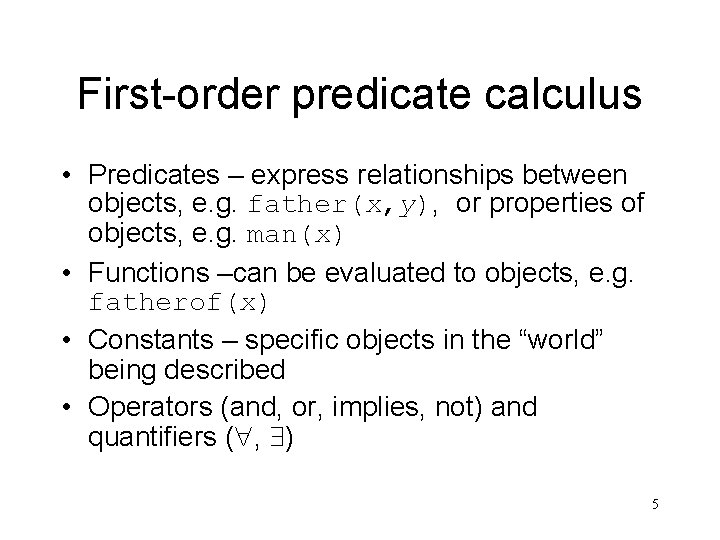

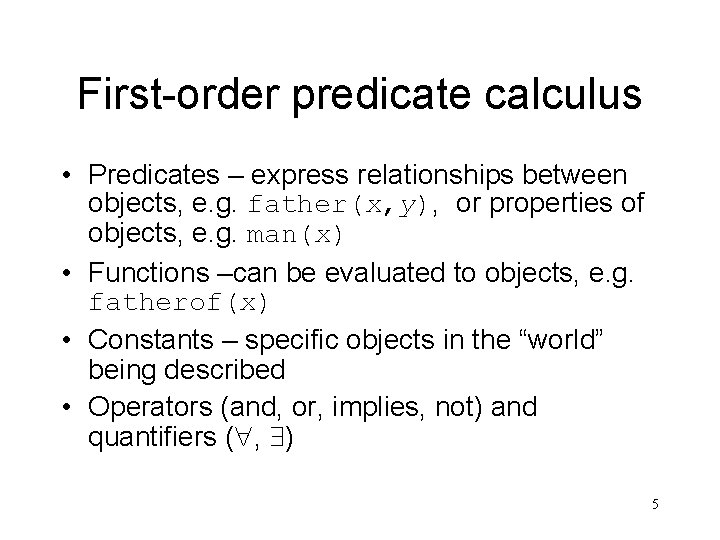

First-order predicate calculus • Predicates – express relationships between objects, e. g. father(x, y), or properties of objects, e. g. man(x) • Functions –can be evaluated to objects, e. g. fatherof(x) • Constants – specific objects in the “world” being described • Operators (and, or, implies, not) and quantifiers ( , ) 5

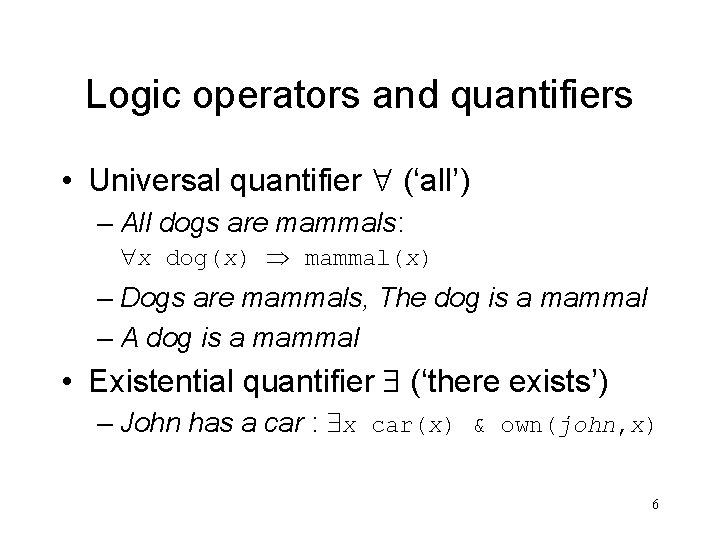

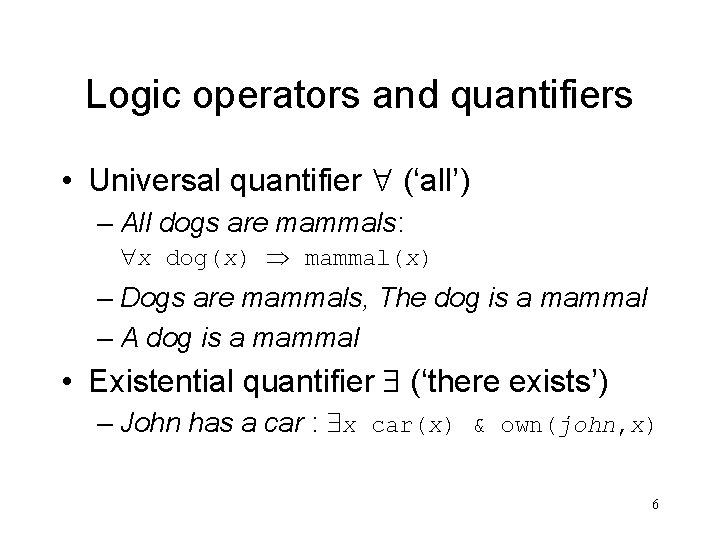

Logic operators and quantifiers • Universal quantifier (‘all’) – All dogs are mammals: x dog(x) mammal(x) – Dogs are mammals, The dog is a mammal – A dog is a mammal • Existential quantifier (‘there exists’) – John has a car : x car(x) & own(john, x) 6

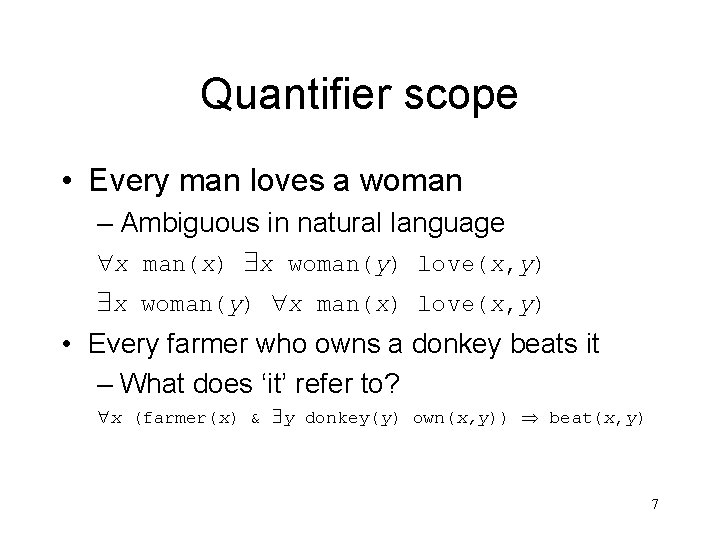

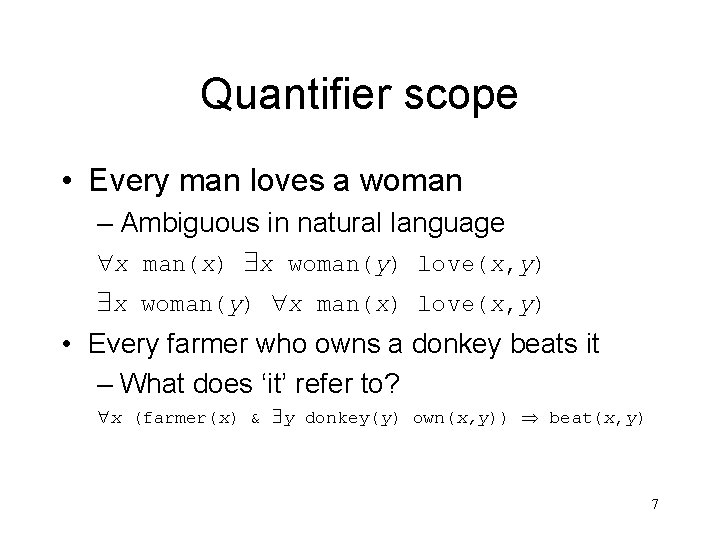

Quantifier scope • Every man loves a woman – Ambiguous in natural language x man(x) x woman(y) love(x, y) x woman(y) x man(x) love(x, y) • Every farmer who owns a donkey beats it – What does ‘it’ refer to? x (farmer(x) & y donkey(y) own(x, y)) beat(x, y) 7

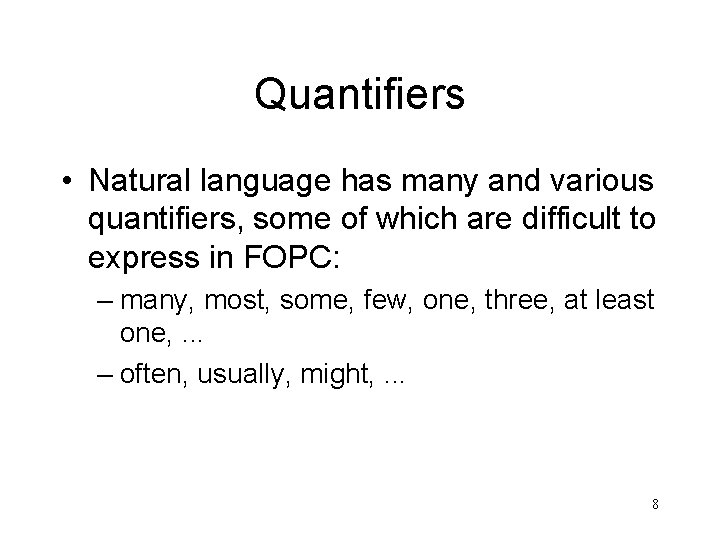

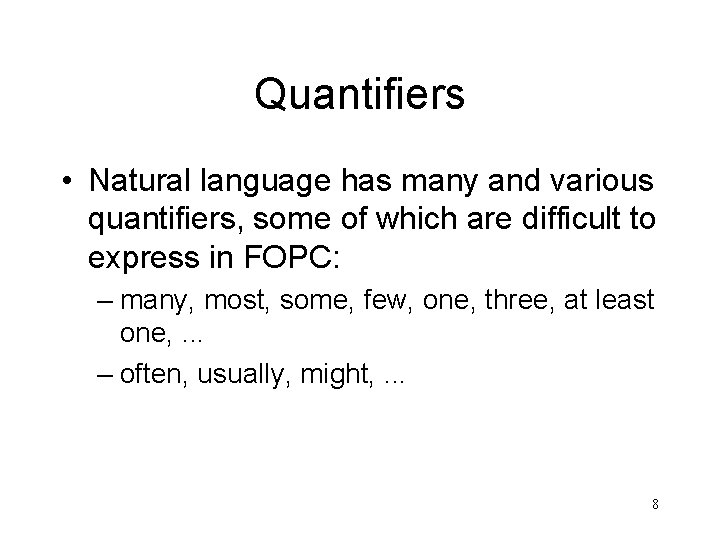

Quantifiers • Natural language has many and various quantifiers, some of which are difficult to express in FOPC: – many, most, some, few, one, three, at least one, . . . – often, usually, might, . . . 8

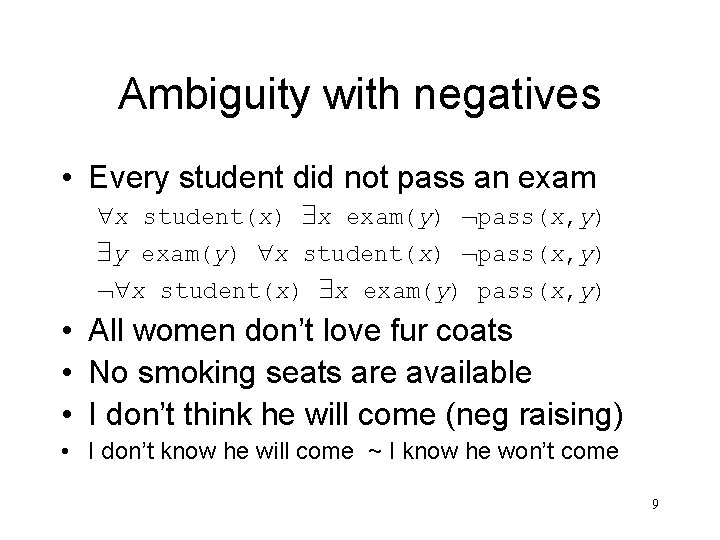

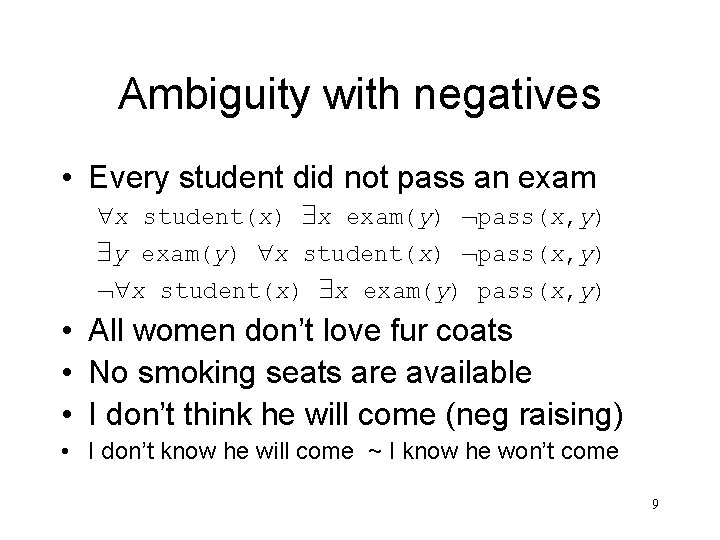

Ambiguity with negatives • Every student did not pass an exam x student(x) x exam(y) pass(x, y) y exam(y) x student(x) pass(x, y) x student(x) x exam(y) pass(x, y) • All women don’t love fur coats • No smoking seats are available • I don’t think he will come (neg raising) • I don’t know he will come ~ I know he won’t come 9

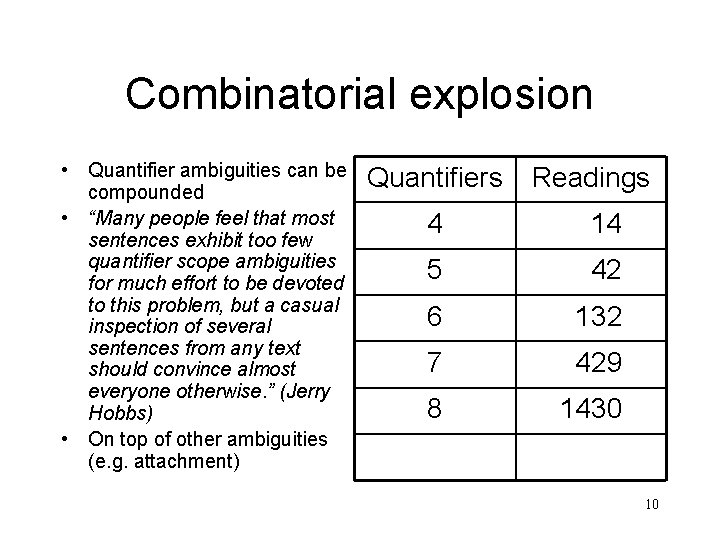

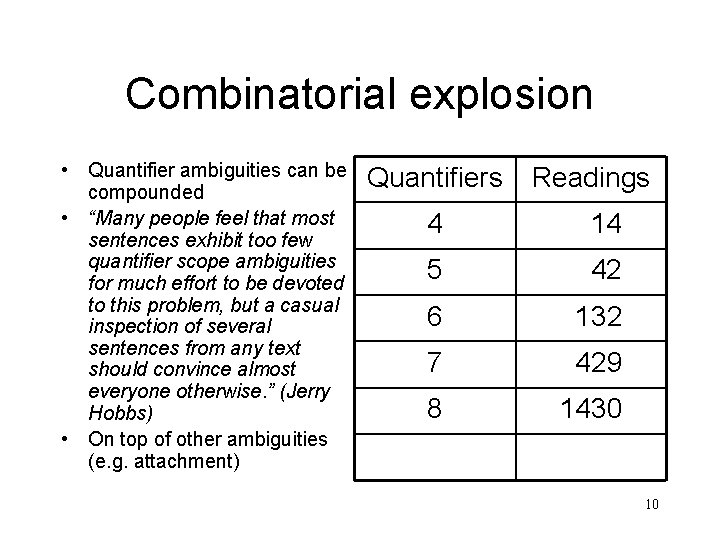

Combinatorial explosion • Quantifier ambiguities can be compounded • “Many people feel that most sentences exhibit too few quantifier scope ambiguities for much effort to be devoted to this problem, but a casual inspection of several sentences from any text should convince almost everyone otherwise. ” (Jerry Hobbs) • On top of other ambiguities (e. g. attachment) Quantifiers Readings 4 14 5 42 6 132 7 429 8 1430 10

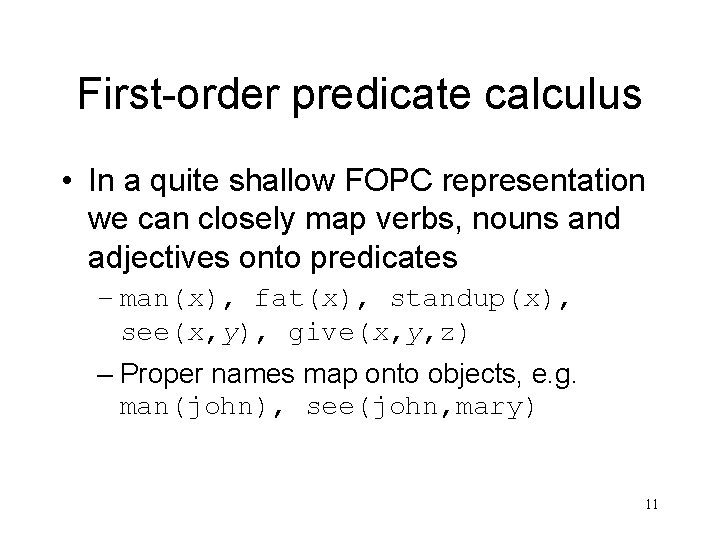

First-order predicate calculus • In a quite shallow FOPC representation we can closely map verbs, nouns and adjectives onto predicates – man(x), fat(x), standup(x), see(x, y), give(x, y, z) – Proper names map onto objects, e. g. man(john), see(john, mary) 11

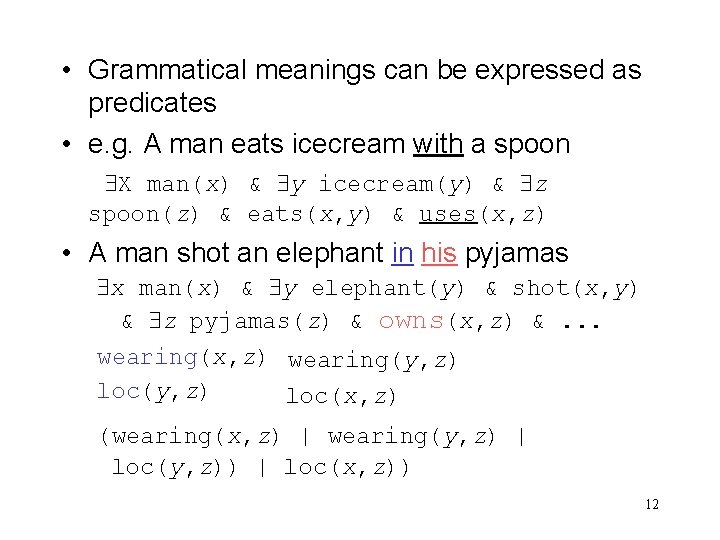

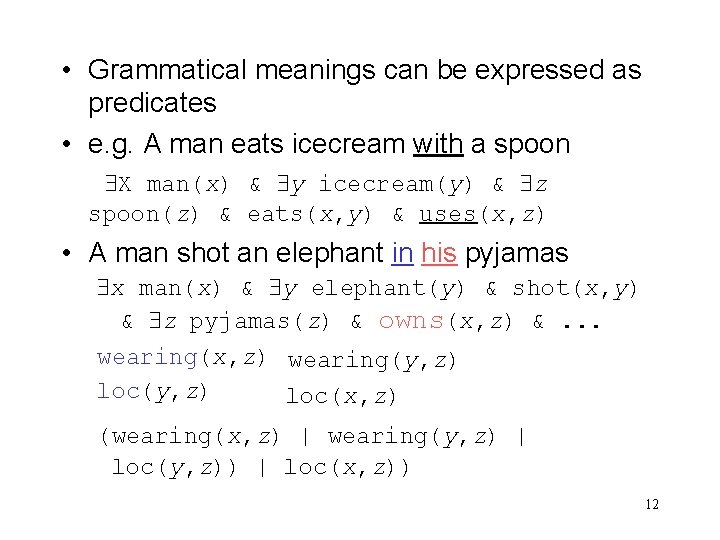

• Grammatical meanings can be expressed as predicates • e. g. A man eats icecream with a spoon X man(x) & y icecream(y) & z spoon(z) & eats(x, y) & uses(x, z) • A man shot an elephant in his pyjamas x man(x) & y elephant(y) & shot(x, y) & z pyjamas(z) & owns(x, z) &. . . wearing(x, z) wearing(y, z) loc(x, z) (wearing(x, z) | wearing(y, z) | loc(y, z)) | loc(x, z)) 12

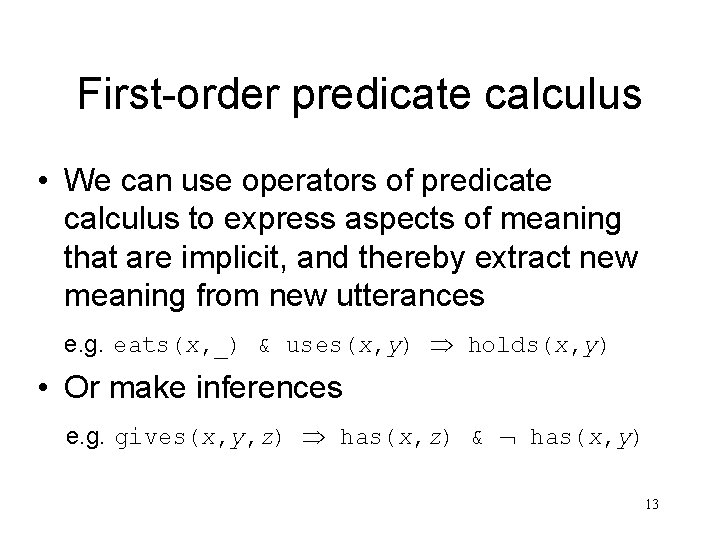

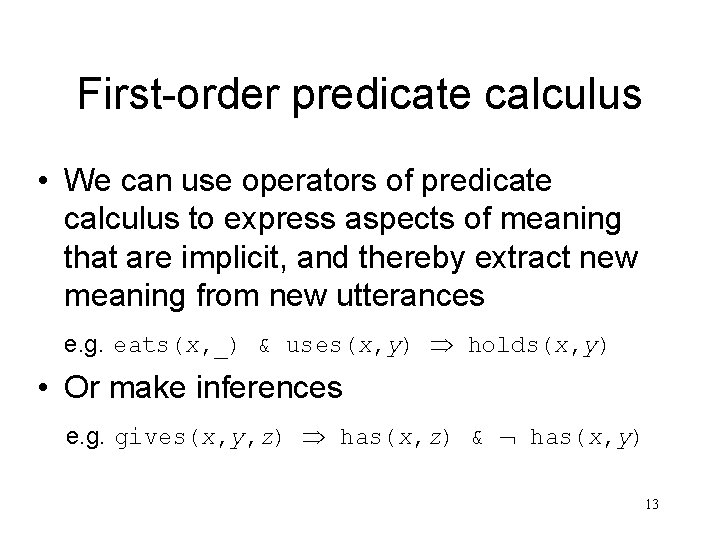

First-order predicate calculus • We can use operators of predicate calculus to express aspects of meaning that are implicit, and thereby extract new meaning from new utterances e. g. eats(x, _) & uses(x, y) holds(x, y) • Or make inferences e. g. gives(x, y, z) has(x, z) & has(x, y) 13

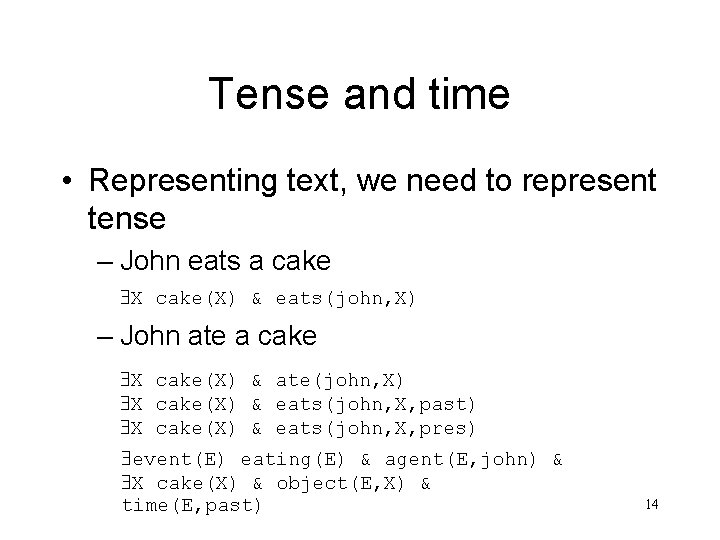

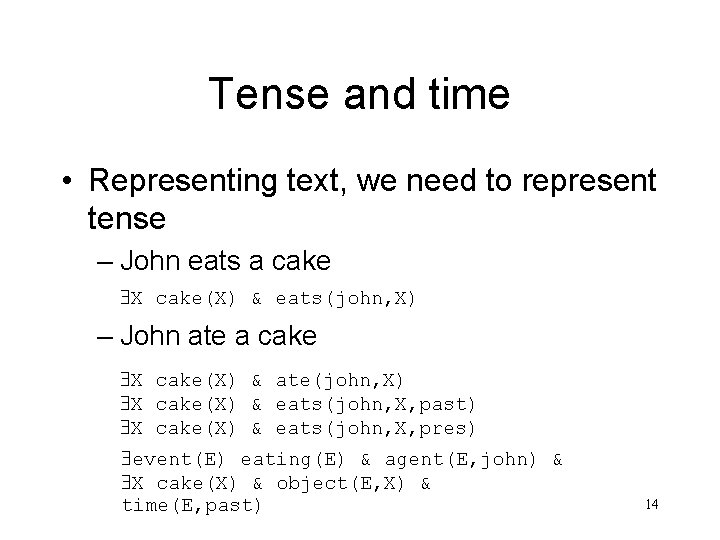

Tense and time • Representing text, we need to represent tense – John eats a cake X cake(X) & eats(john, X) – John ate a cake X cake(X) & ate(john, X) X cake(X) & eats(john, X, past) X cake(X) & eats(john, X, pres) event(E) eating(E) & agent(E, john) & X cake(X) & object(E, X) & time(E, past) past(E) 14

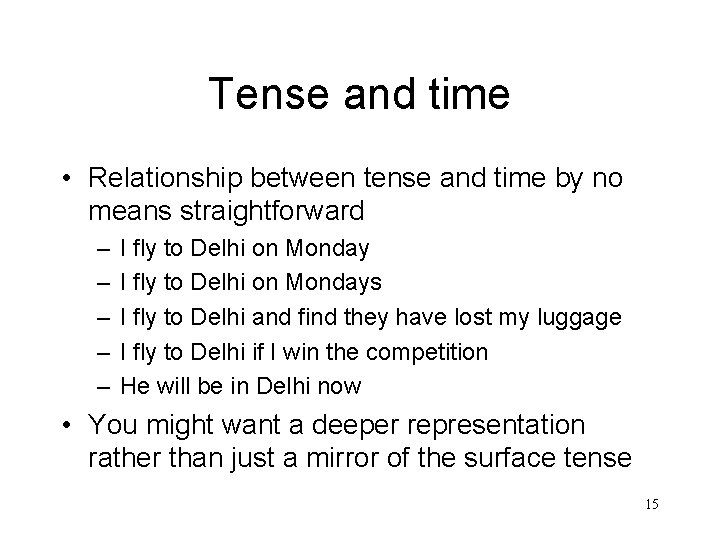

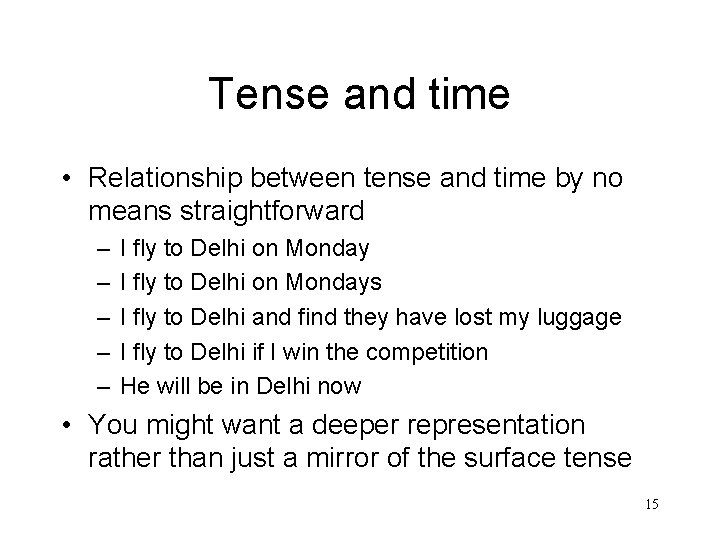

Tense and time • Relationship between tense and time by no means straightforward – – – I fly to Delhi on Mondays I fly to Delhi and find they have lost my luggage I fly to Delhi if I win the competition He will be in Delhi now • You might want a deeper representation rather than just a mirror of the surface tense 15

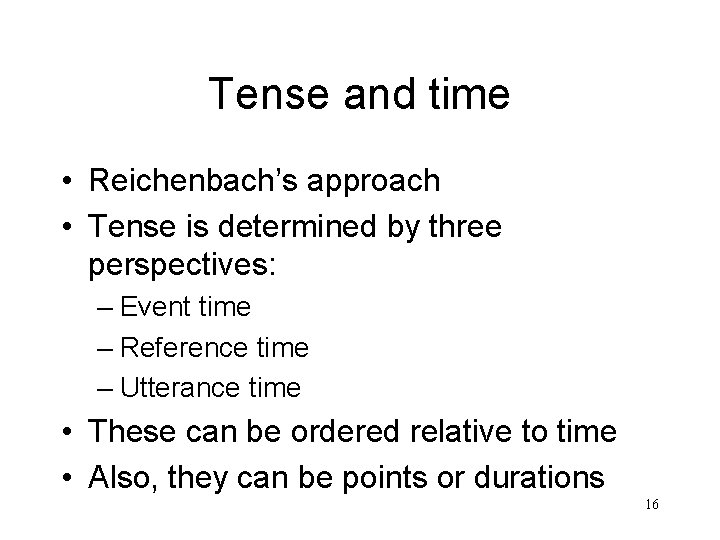

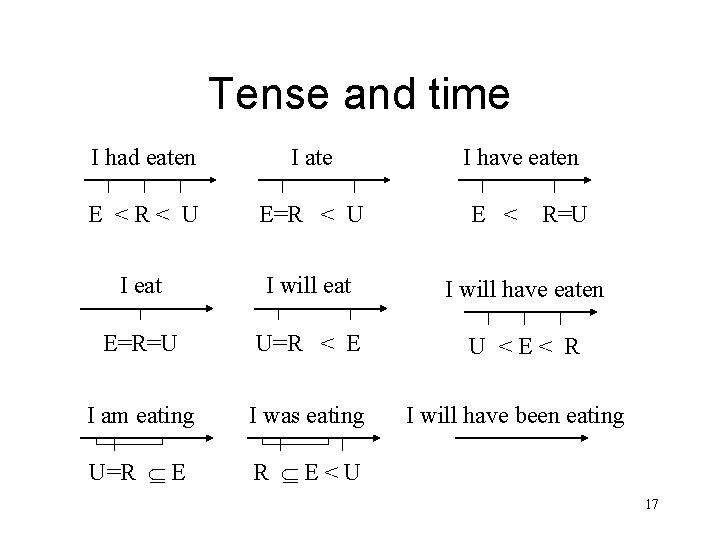

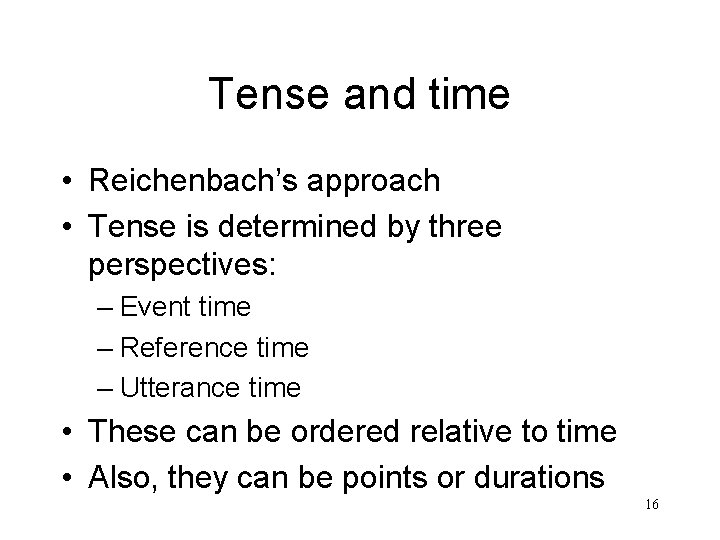

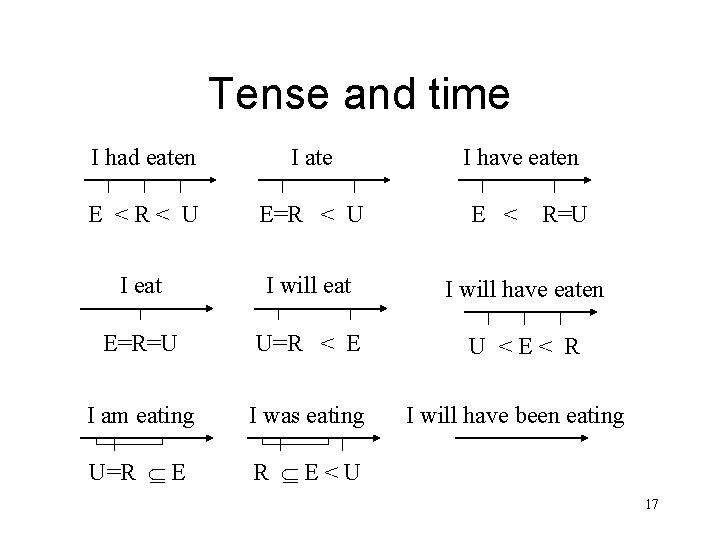

Tense and time • Reichenbach’s approach • Tense is determined by three perspectives: – Event time – Reference time – Utterance time • These can be ordered relative to time • Also, they can be points or durations 16

Tense and time I had eaten I ate I have eaten E <R< U E=R < U I eat I will have eaten E=R=U U=R < E U <E< R I am eating I was eating U=R E R E<U E < R=U I will have been eating 17

Linguistic issues • There are many other similarly tricky linguistic phenomena – Modality (could, should, would, must, may) – Aspect (completed, ongoing, resulting) – Determination (the, a, some, all, none) – Fuzzy sets (often, some, many, usually) 18

Semantic analysis • Syntax-driven semantic analysis – Compositionality • Semantic grammars – Procedural view of semantics 19

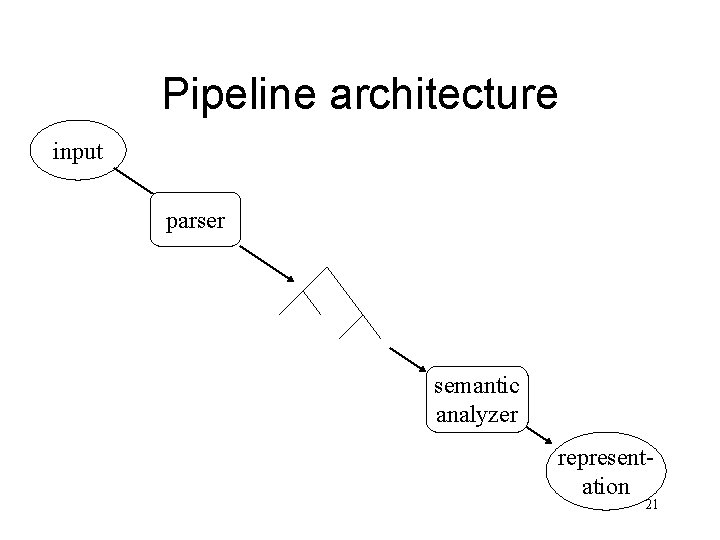

Syntax-driven semantic analysis • Based on syntactic grammars • CFG rules augmented by semantic annotations • Compositionality – Meaning of the whole is the sum of the meaning of its parts – But not just the parts, but also the way they fit together 20

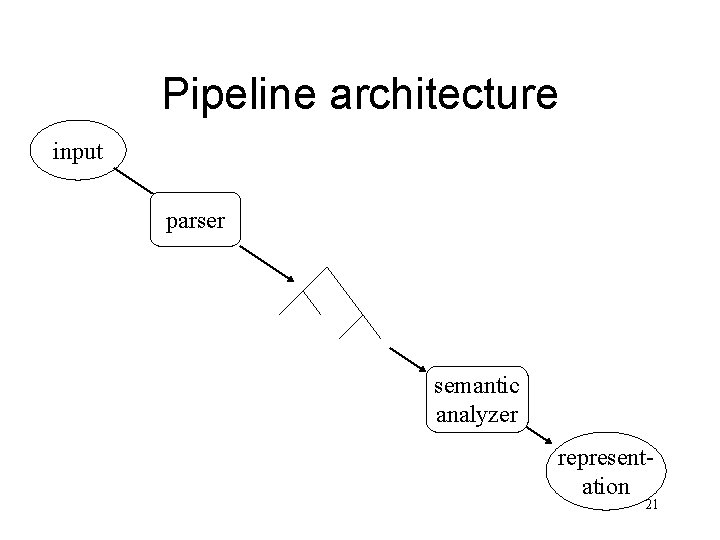

Pipeline architecture input parser semantic analyzer representation 21

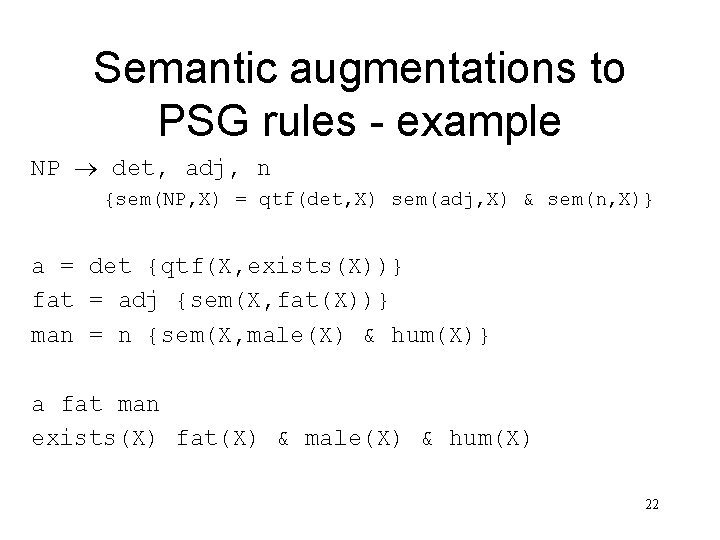

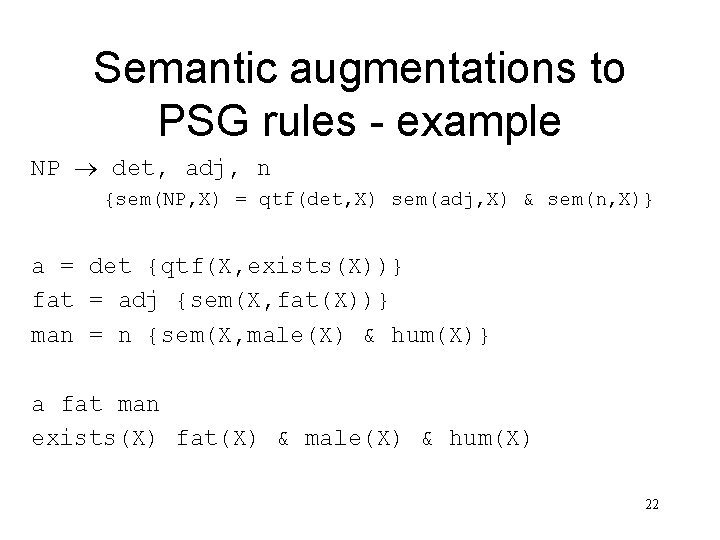

Semantic augmentations to PSG rules - example NP det, adj, n {sem(NP, X) = qtf(det, X) sem(adj, X) & sem(n, X)} a = det {qtf(X, exists(X))} fat = adj {sem(X, fat(X))} man = n {sem(X, male(X) & hum(X)} a fat man exists(X) fat(X) & male(X) & hum(X) 22

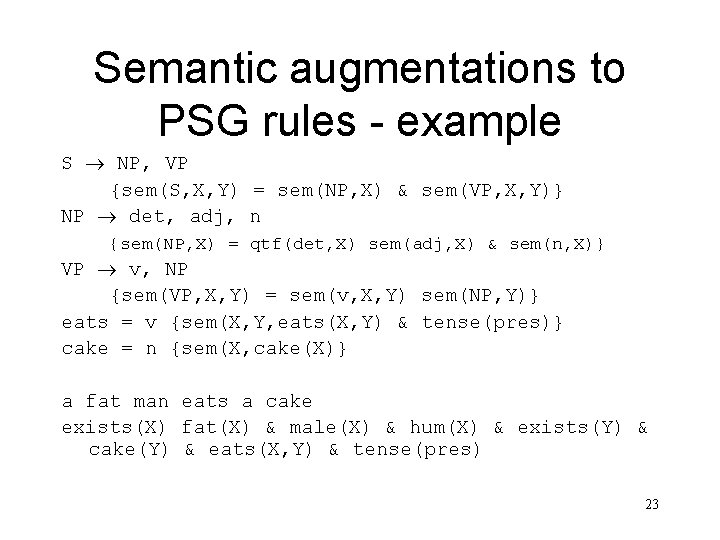

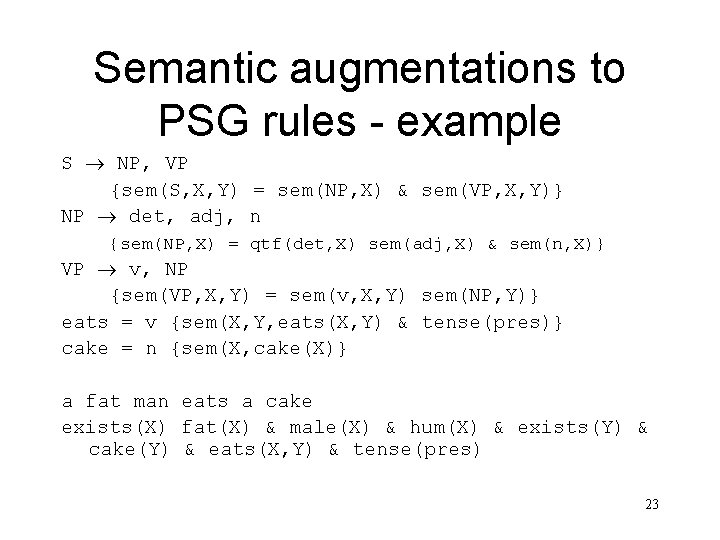

Semantic augmentations to PSG rules - example S NP, VP {sem(S, X, Y) = sem(NP, X) & sem(VP, X, Y)} NP det, adj, n {sem(NP, X) = qtf(det, X) sem(adj, X) & sem(n, X)} VP v, NP {sem(VP, X, Y) = sem(v, X, Y) sem(NP, Y)} eats = v {sem(X, Y, eats(X, Y) & tense(pres)} cake = n {sem(X, cake(X)} a fat man eats a cake exists(X) fat(X) & male(X) & hum(X) & exists(Y) & cake(Y) & eats(X, Y) & tense(pres) 23

How to do this • • Quite complex Fortunately, there is a mechanism Lambda calculus (Church 1940) See J&M ; -) • Such representations often called “quasi logical forms” because of their (too) close relation to syntax 24