Poverty Social Impacts of the NEP Removing barriers

Poverty & Social Impacts of the NEP Removing barriers to electricity access

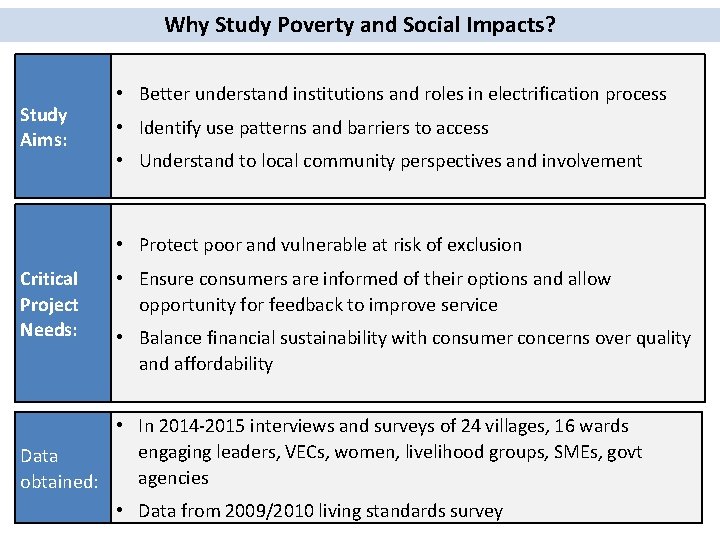

Why Study Poverty and Social Impacts? Study Aims: • Better understand institutions and roles in electrification process • Identify use patterns and barriers to access • Understand to local community perspectives and involvement • Protect poor and vulnerable at risk of exclusion Critical Project Needs: • Ensure consumers are informed of their options and allow opportunity for feedback to improve service • Balance financial sustainability with consumer concerns over quality and affordability • In 2014 -2015 interviews and surveys of 24 villages, 16 wards engaging leaders, VECs, women, livelihood groups, SMEs, govt Data agencies obtained: • Data from 2009/2010 living standards survey

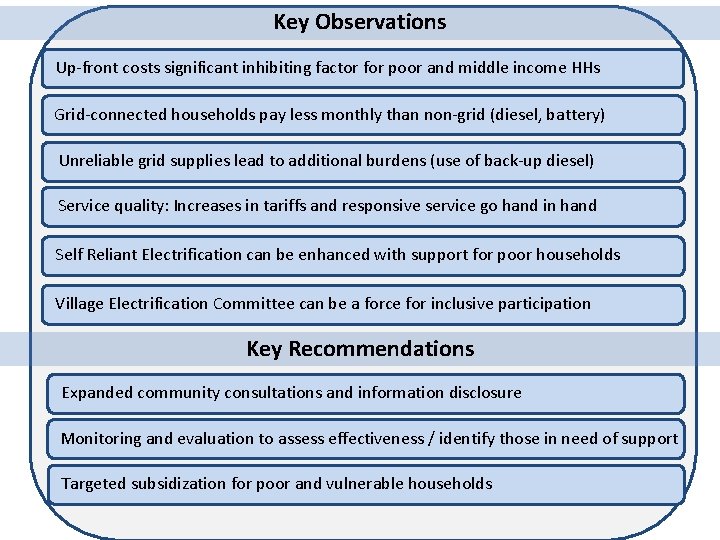

Key Observations Up-front costs significant inhibiting factor for poor and middle income HHs Grid-connected households pay less monthly than non-grid (diesel, battery) Unreliable grid supplies lead to additional burdens (use of back-up diesel) Service quality: Increases in tariffs and responsive service go hand in hand Self Reliant Electrification can be enhanced with support for poor households Village Electrification Committee can be a force for inclusive participation Key Recommendations Expanded community consultations and information disclosure Monitoring and evaluation to assess effectiveness / identify those in need of support Targeted subsidization for poor and vulnerable households

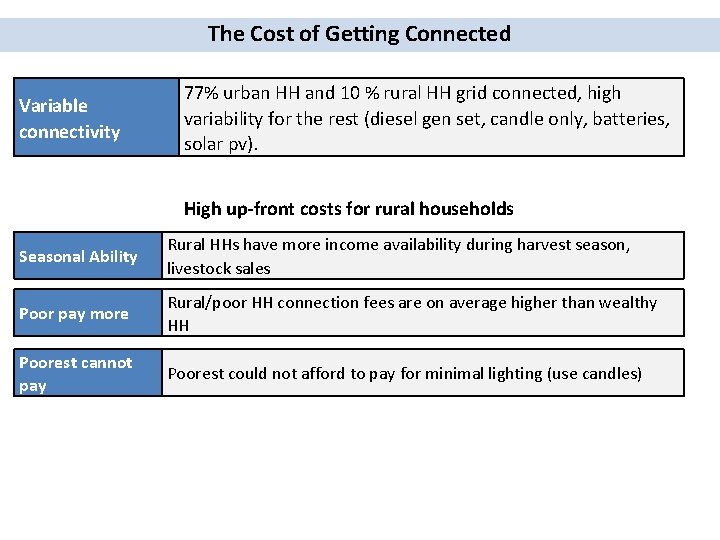

The Cost of Getting Connected Variable connectivity 77% urban HH and 10 % rural HH grid connected, high variability for the rest (diesel gen set, candle only, batteries, solar pv). High up-front costs for rural households Seasonal Ability Rural HHs have more income availability during harvest season, livestock sales Poor pay more Rural/poor HH connection fees are on average higher than wealthy HH Poorest cannot pay Poorest could not afford to pay for minimal lighting (use candles)

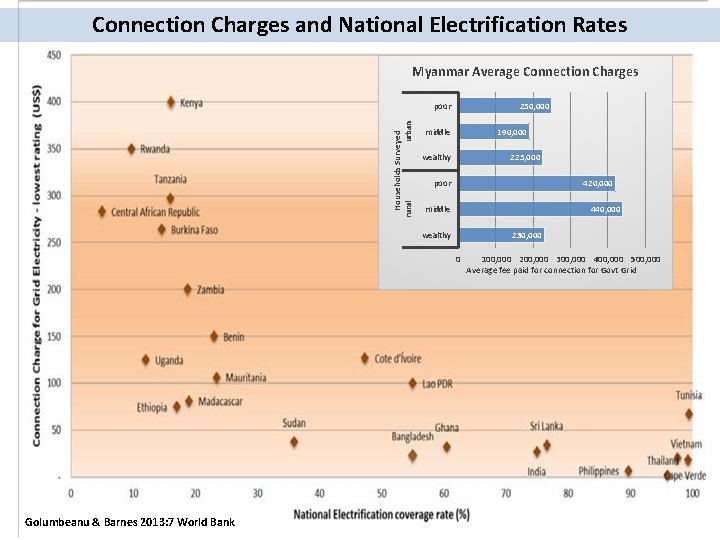

Connection Charges and National Electrification Rates Myanmar Average Connection Charges 250, 000 Households Surveyed rural urban poor middle 190, 000 wealthy 225, 000 poor 420, 000 middle 440, 000 wealthy 230, 000 0 Golumbeanu & Barnes 2013: 7 World Bank 100, 000 200, 000 300, 000 400, 000 500, 000 Average fee paid for connection for Govt Grid

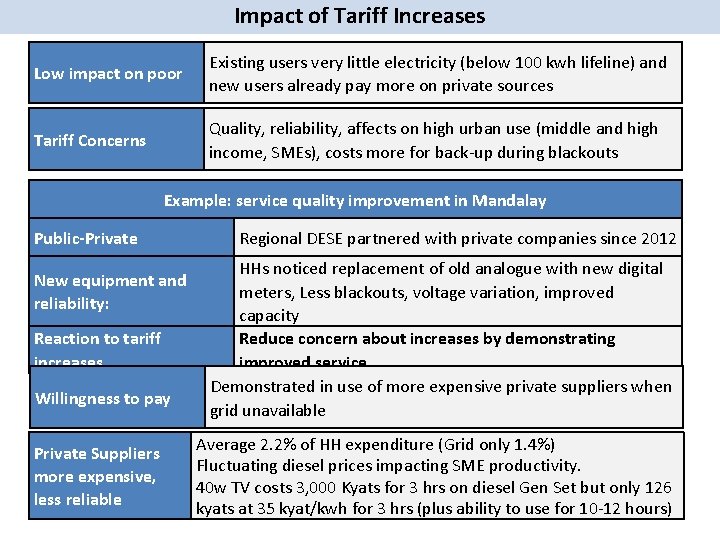

Impact of Tariff Increases Low impact on poor Existing users very little electricity (below 100 kwh lifeline) and new users already pay more on private sources Tariff Concerns Quality, reliability, affects on high urban use (middle and high income, SMEs), costs more for back-up during blackouts Example: service quality improvement in Mandalay Public-Private New equipment and reliability: Reaction to tariff increases Willingness to pay Private Suppliers more expensive, less reliable Regional DESE partnered with private companies since 2012 HHs noticed replacement of old analogue with new digital meters, Less blackouts, voltage variation, improved capacity Reduce concern about increases by demonstrating improved service Demonstrated in use of more expensive private suppliers when grid unavailable Average 2. 2% of HH expenditure (Grid only 1. 4%) Fluctuating diesel prices impacting SME productivity. 40 w TV costs 3, 000 Kyats for 3 hrs on diesel Gen Set but only 126 kyats at 35 kyat/kwh for 3 hrs (plus ability to use for 10 -12 hours)

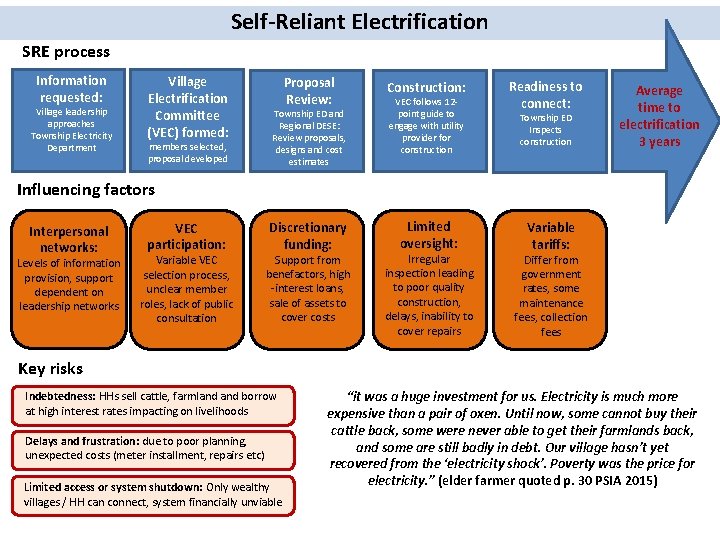

Self-Reliant Electrification SRE process Information requested: Village leadership approaches Township Electricity Department Village Electrification Committee (VEC) formed: members selected, proposal developed Proposal Review: Township ED and Regional DESE: Review proposals, designs and cost estimates Construction: VEC follows 12 point guide to engage with utility provider for construction Readiness to connect: Township ED Inspects construction Average time to electrification 3 years Influencing factors Interpersonal networks: Levels of information provision, support dependent on leadership networks VEC participation: Variable VEC selection process, unclear member roles, lack of public consultation Discretionary funding: Support from benefactors, high -interest loans, sale of assets to cover costs Limited oversight: Irregular inspection leading to poor quality construction, delays, inability to cover repairs Variable tariffs: Differ from government rates, some maintenance fees, collection fees Key risks Indebtedness: HHs sell cattle, farmland borrow at high interest rates impacting on livelihoods Delays and frustration: due to poor planning, unexpected costs (meter installment, repairs etc) Limited access or system shutdown: Only wealthy villages / HH can connect, system financially unviable “it was a huge investment for us. Electricity is much more expensive than a pair of oxen. Until now, some cannot buy their cattle back, some were never able to get their farmlands back, and some are still badly in debt. Our village hasn’t yet recovered from the ‘electricity shock’. Poverty was the price for electricity. ” (elder farmer quoted p. 30 PSIA 2015)

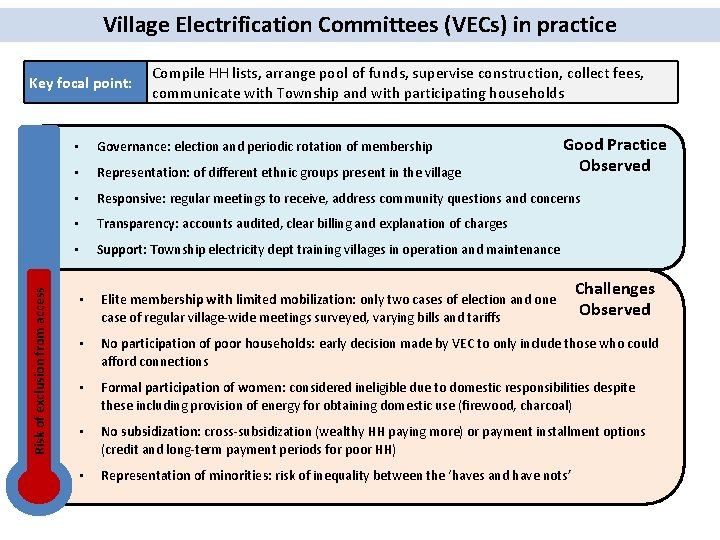

Village Electrification Committees (VECs) in practice Risk of exclusion from access Key focal point: Compile HH lists, arrange pool of funds, supervise construction, collect fees, communicate with Township and with participating households Good Practice Observed • Governance: election and periodic rotation of membership • Representation: of different ethnic groups present in the village • Responsive: regular meetings to receive, address community questions and concerns • Transparency: accounts audited, clear billing and explanation of charges • Support: Township electricity dept training villages in operation and maintenance Challenges Observed • Elite membership with limited mobilization: only two cases of election and one case of regular village-wide meetings surveyed, varying bills and tariffs • No participation of poor households: early decision made by VEC to only include those who could afford connections • Formal participation of women: considered ineligible due to domestic responsibilities despite these including provision of energy for obtaining domestic use (firewood, charcoal) • No subsidization: cross-subsidization (wealthy HH paying more) or payment installment options (credit and long-term payment periods for poor HH) • Representation of minorities: risk of inequality between the ‘haves and have nots’

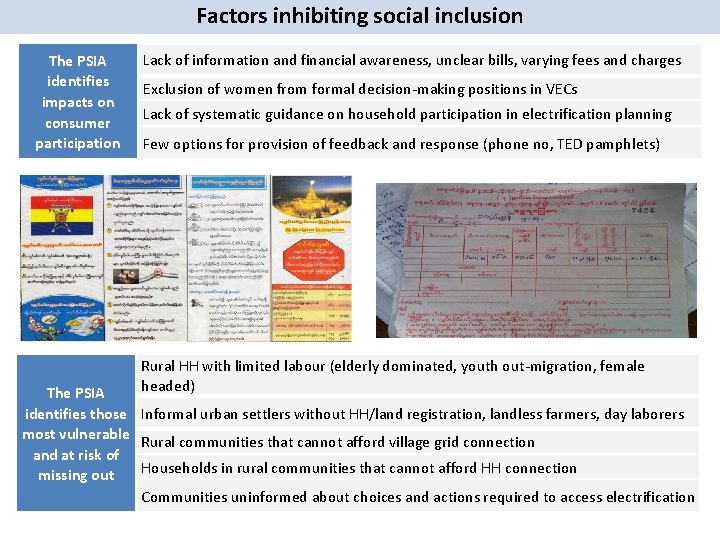

Factors inhibiting social inclusion The PSIA identifies impacts on consumer participation Lack of information and financial awareness, unclear bills, varying fees and charges Exclusion of women from formal decision-making positions in VECs Lack of systematic guidance on household participation in electrification planning Few options for provision of feedback and response (phone no, TED pamphlets) Rural HH with limited labour (elderly dominated, youth out-migration, female headed) The PSIA identifies those Informal urban settlers without HH/land registration, landless farmers, day laborers most vulnerable Rural communities that cannot afford village grid connection and at risk of Households in rural communities that cannot afford HH connection missing out Communities uninformed about choices and actions required to access electrification

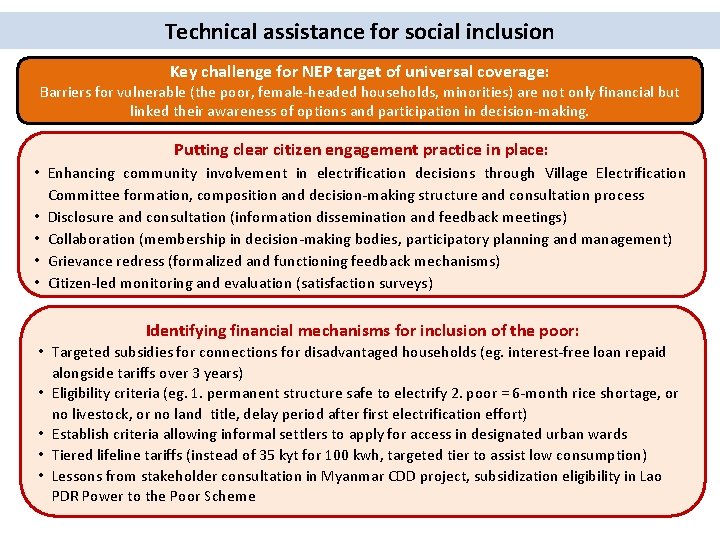

Technical assistance for social inclusion Key challenge for NEP target of universal coverage: Barriers for vulnerable (the poor, female-headed households, minorities) are not only financial but linked their awareness of options and participation in decision-making. Putting clear citizen engagement practice in place: • Enhancing community involvement in electrification decisions through Village Electrification Committee formation, composition and decision-making structure and consultation process • Disclosure and consultation (information dissemination and feedback meetings) • Collaboration (membership in decision-making bodies, participatory planning and management) • Grievance redress (formalized and functioning feedback mechanisms) • Citizen-led monitoring and evaluation (satisfaction surveys) Identifying financial mechanisms for inclusion of the poor: • Targeted subsidies for connections for disadvantaged households (eg. interest-free loan repaid alongside tariffs over 3 years) • Eligibility criteria (eg. 1. permanent structure safe to electrify 2. poor = 6 -month rice shortage, or no livestock, or no land title, delay period after first electrification effort) • Establish criteria allowing informal settlers to apply for access in designated urban wards • Tiered lifeline tariffs (instead of 35 kyt for 100 kwh, targeted tier to assist low consumption) • Lessons from stakeholder consultation in Myanmar CDD project, subsidization eligibility in Lao PDR Power to the Poor Scheme

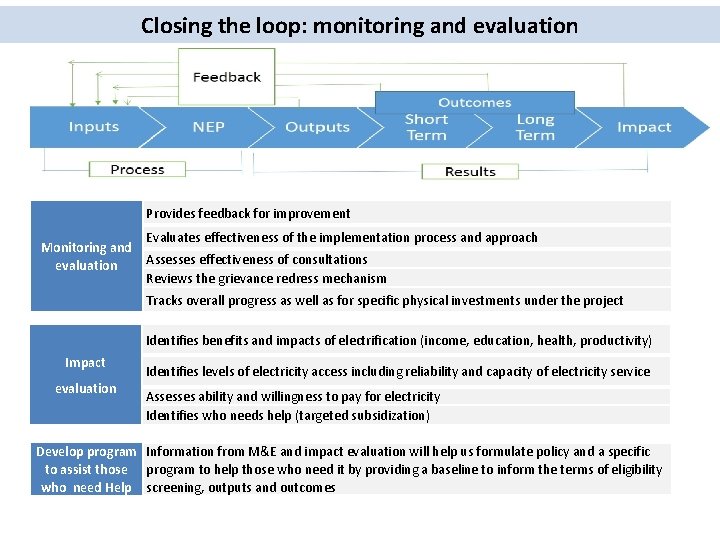

Closing the loop: monitoring and evaluation Provides feedback for improvement Monitoring and evaluation Evaluates effectiveness of the implementation process and approach Assesses effectiveness of consultations Reviews the grievance redress mechanism Tracks overall progress as well as for specific physical investments under the project Identifies benefits and impacts of electrification (income, education, health, productivity) Impact evaluation Identifies levels of electricity access including reliability and capacity of electricity service Assesses ability and willingness to pay for electricity Identifies who needs help (targeted subsidization) Develop program Information from M&E and impact evaluation will help us formulate policy and a specific to assist those program to help those who need it by providing a baseline to inform the terms of eligibility who need Help screening, outputs and outcomes

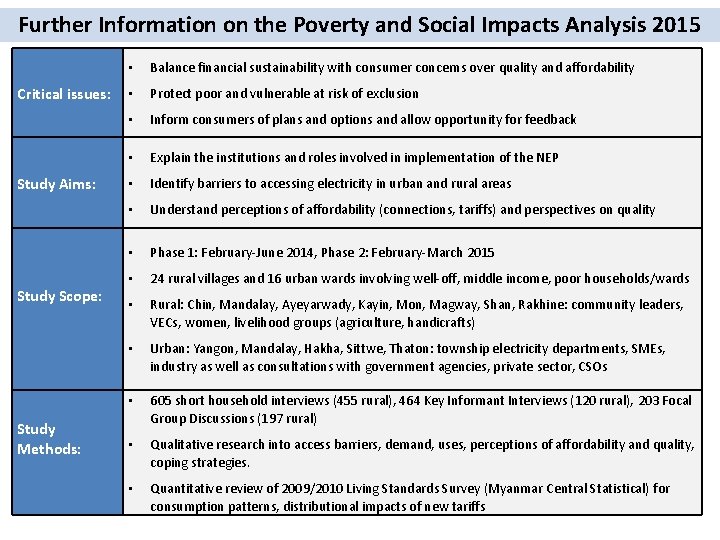

Further Information on the Poverty and Social Impacts Analysis 2015 Critical issues: Study Aims: Study Scope: Study Methods: • Balance financial sustainability with consumer concerns over quality and affordability • Protect poor and vulnerable at risk of exclusion • Inform consumers of plans and options and allow opportunity for feedback • Explain the institutions and roles involved in implementation of the NEP • Identify barriers to accessing electricity in urban and rural areas • Understand perceptions of affordability (connections, tariffs) and perspectives on quality • Phase 1: February-June 2014, Phase 2: February-March 2015 • 24 rural villages and 16 urban wards involving well-off, middle income, poor households/wards • Rural: Chin, Mandalay, Ayeyarwady, Kayin, Mon, Magway, Shan, Rakhine: community leaders, VECs, women, livelihood groups (agriculture, handicrafts) • Urban: Yangon, Mandalay, Hakha, Sittwe, Thaton: township electricity departments, SMEs, industry as well as consultations with government agencies, private sector, CSOs • 605 short household interviews (455 rural), 464 Key Informant Interviews (120 rural), 203 Focal Group Discussions (197 rural) • Qualitative research into access barriers, demand, uses, perceptions of affordability and quality, coping strategies. • Quantitative review of 2009/2010 Living Standards Survey (Myanmar Central Statistical) for consumption patterns, distributional impacts of new tariffs

- Slides: 12