Population Genetics Individuals dont evolve populations do Gene

- Slides: 48

Population Genetics: • Individuals don’t evolve, populations do. • Gene pools: entire collection of genes among a population; populations evolve as the relative frequencies of different alleles (genes) change.

Population Genetics: • Natural selection acts on the phenotypes (physical traits) of a population, not directly on the genes. But it can change the relative frequencies of the alleles in a gene pool (population) over time.

Population Genetics: • Gene Flow: the loss or gain of alleles from a population due to the emigration or immigration of fertile individuals, or the transfer of gametes between populations. This reduces the differences between populations.

Evolution of Species: • It is theorized that different species developed because of: 4. Genetic Drift: in small populations, individuals that carry a particular allele may leave more descendants than other individuals, just by chance, not selection.

Genetic Drift • Over time, a series of chance occurrences of this type can cause an allele to become common in a population. • For example, Amish of Lancaster, Pennsylvania have a recessive allele causing dwarfism and higher proportion of polydactylism (1 -in 14 compared to 1 -in-1, 000).

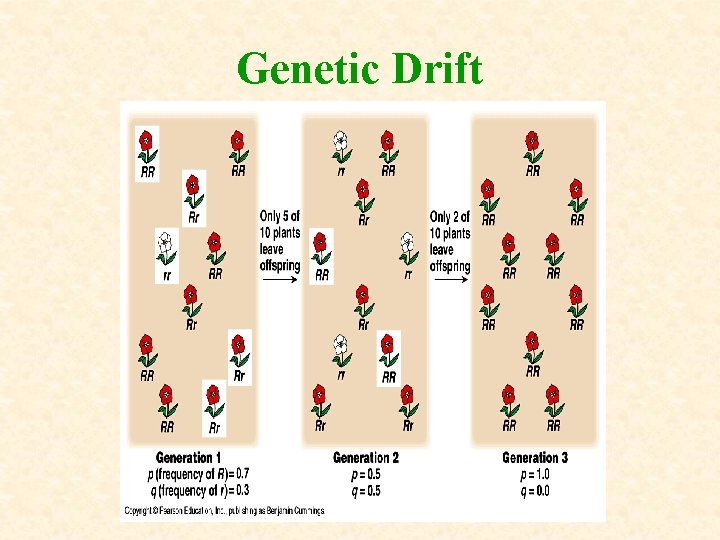

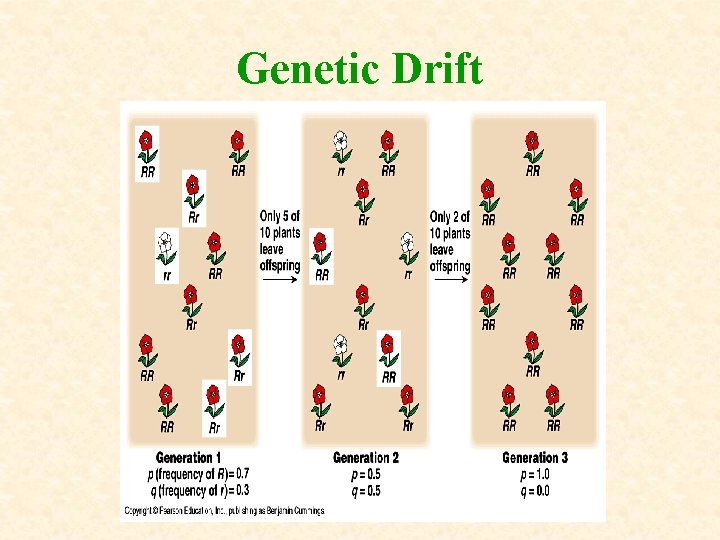

Genetic Drift

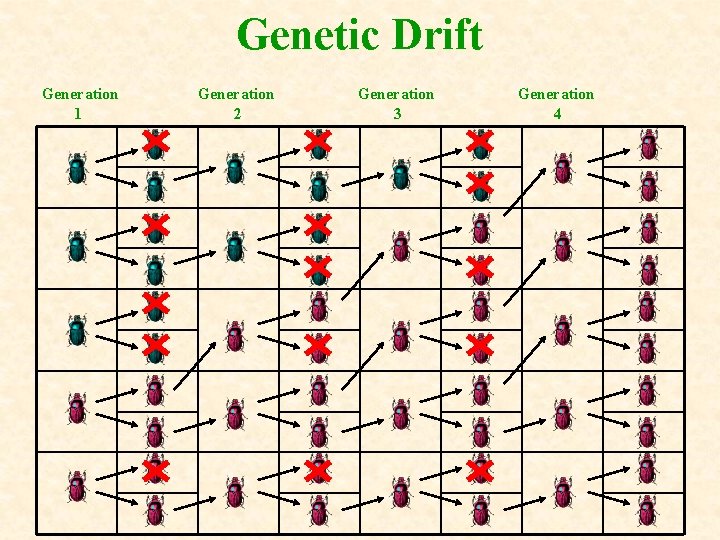

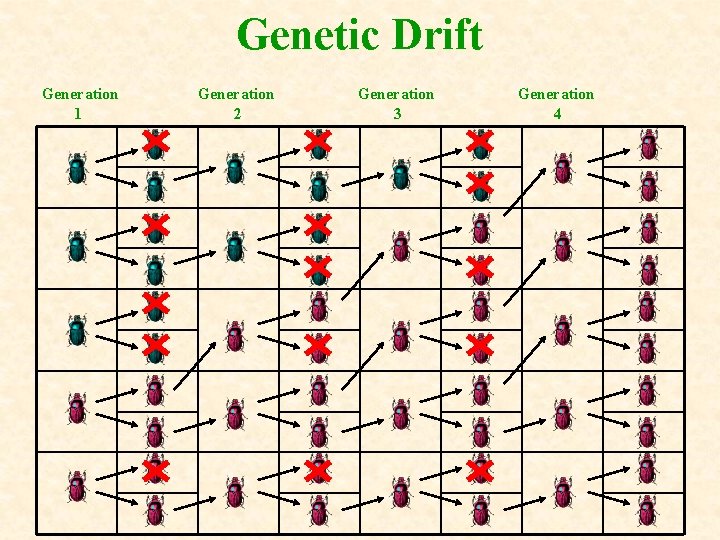

Genetic Drift Generation 1 Generation 2 Generation 3 Generation 4

Genetic Drift There are two common types of genetic drift: 1. The “Founder Effect” and 2. The “Bottleneck Effect. ”

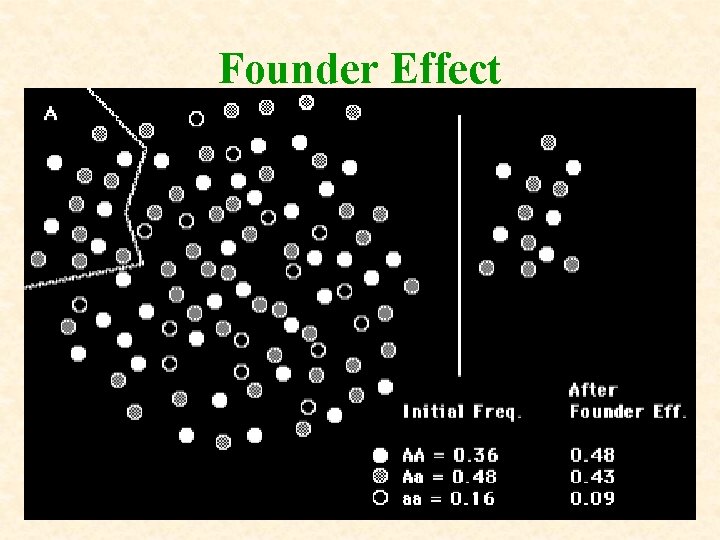

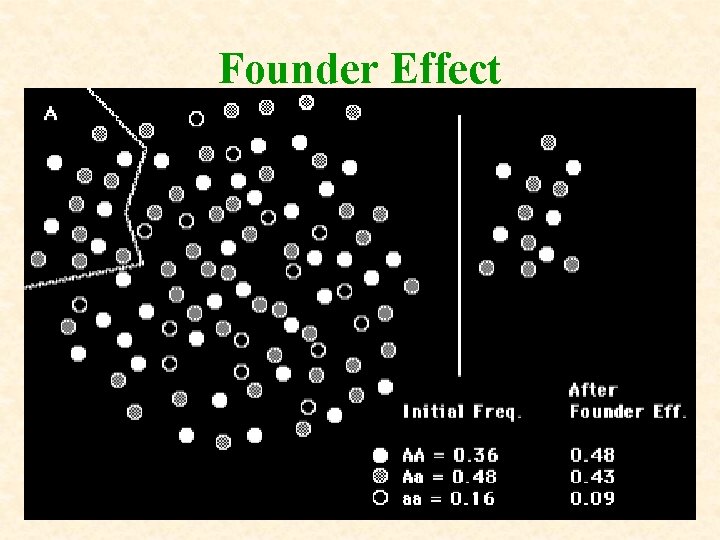

Genetic Drift A. The Founder Effect: Where individuals may not be representative of the population they came from, yet start a new population where their phenotypes come to be expressed frequently.

Founder Effect

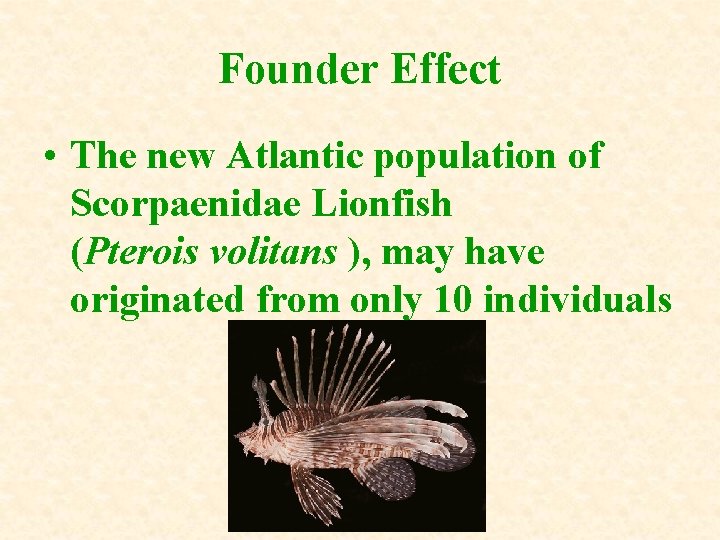

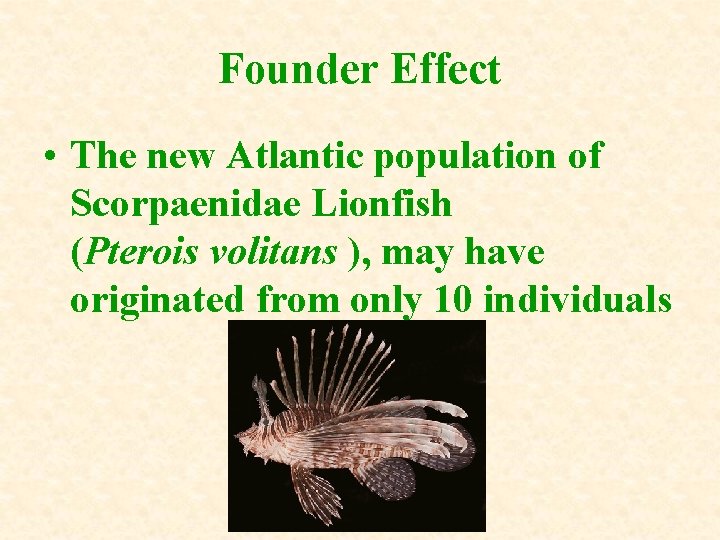

Founder Effect • The new Atlantic population of Scorpaenidae Lionfish (Pterois volitans ), may have originated from only 10 individuals

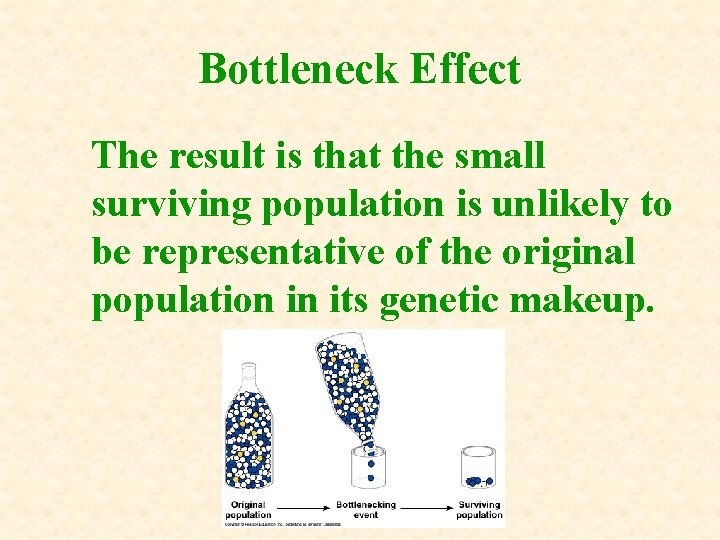

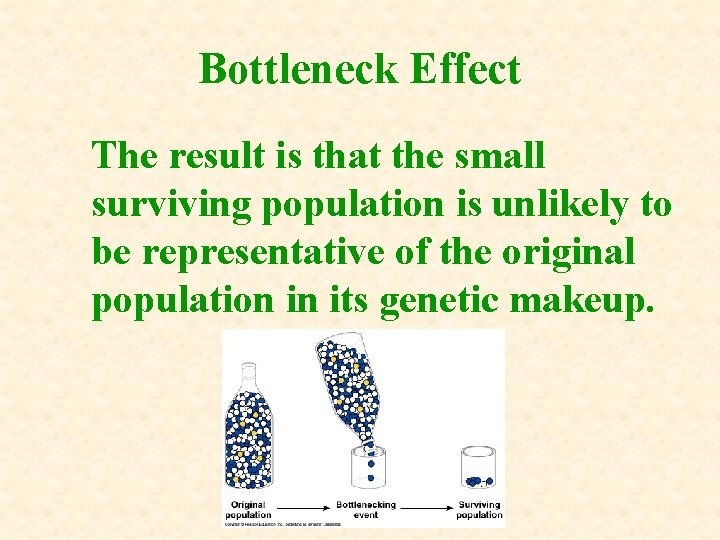

Genetic Drift B. The Bottleneck Effect: Disasters such as earthquakes, floods or fires may reduce the size of a population drastically, killing victims rather unselectively.

Bottleneck Effect The result is that the small surviving population is unlikely to be representative of the original population in its genetic makeup.

Bottleneck Effect Populations subjected to near extinction (like Cheetahs) endure a bottleneck.

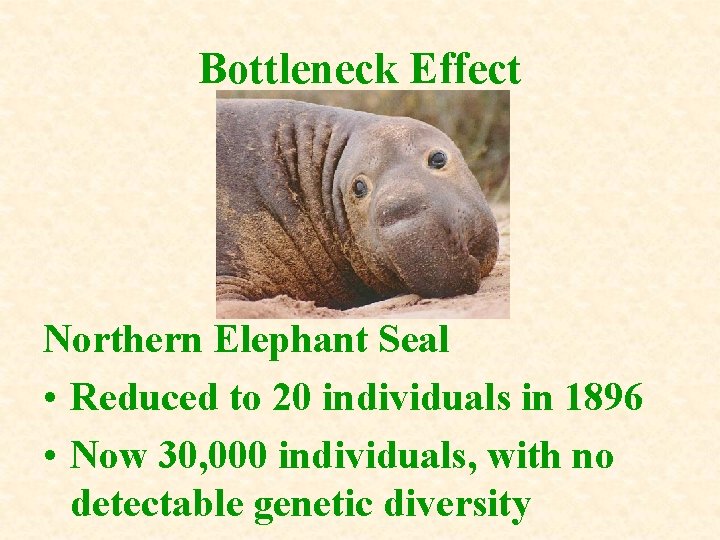

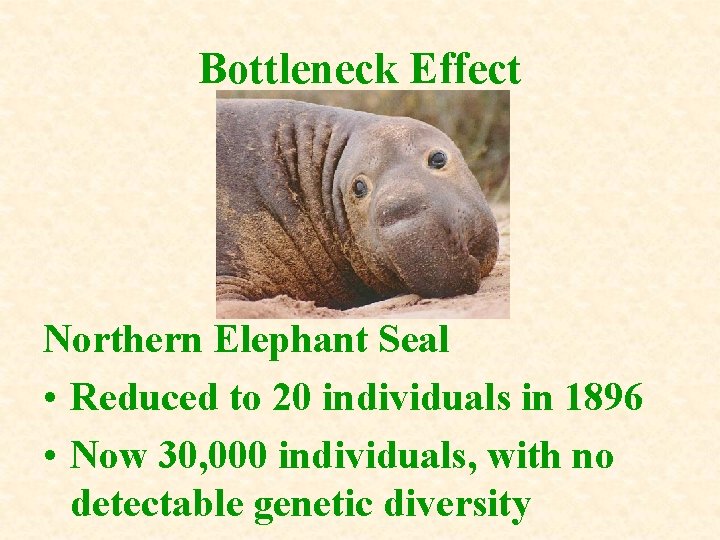

Bottleneck Effect Northern Elephant Seal • Reduced to 20 individuals in 1896 • Now 30, 000 individuals, with no detectable genetic diversity

Evolution of Species: • It is theorized that different species developed because of: 5. Non-Random Mating: inbreeding and assortive mating (both shift frequencies of different genotypes). Both homozygotes increase in frequency, but heterozygotes decrease.

Sources of Genetic Variation: • Mutation: change(s) in the DNA of an organism. This is the original source of genetic variation (raw material for natural selection). • Provides new alleles. • Seemingly harmful mutations can be source of variation for better adaptation to a new or changing environment.

Sources of Genetic Variation: • Genetic shuffling that takes place during meiosis prior to sexual reproduction. • Both the independent assortment of chromosomes during meiosis and the possibilities of “crossing over. ”

Population Genetics: • Natural Selection on Single-Gene Traits: when there are only two possible phenotypes, natural selection can lead to changes in allele frequency which don’t match typical expectations determined by punnett squares.

Population Genetics: • Natural Selection on Polygenic Traits: polygenic traits are those controlled by more than one set of genes. The phenotypes displayed by these traits often are displayed in a “normal distribution, ” also known as a bell-shaped curve.

Population Genetics: • When there are more than two variations of possible phenotypes, natural selection causes shifts in the distribution of traits. • There are three ways natural selection can effect the distribution of phenotypes.

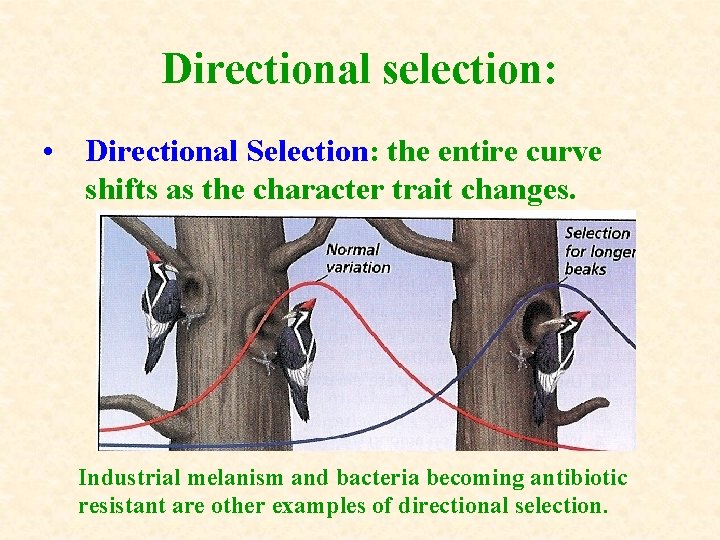

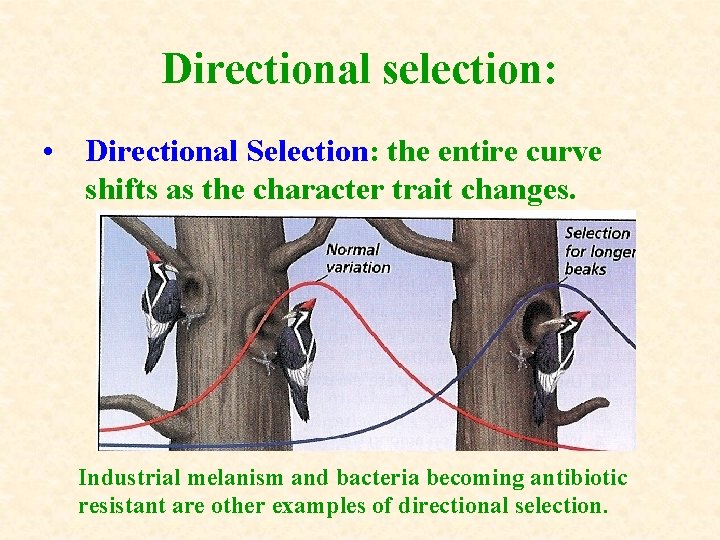

Three ways natural selection can effect the distribution of phenotypes: 1. Directional Selection: the entire curve shifts as the character trait changes.

Directional selection: • Occurs when one extreme of the distribution has an adaptation that could become favorable. • When an environmental change or species migrate – the new environment favors the extreme phenotype and the population evolves.

Directional selection: • For Example: woodpeckers that have shorter-lengthed beaks struggling to compete with woodpeckers that have longerlengthed beaks leading to the natural selection of the woodpeckers with longerlengthed beaks.

Directional selection: • Directional Selection: the entire curve shifts as the character trait changes. Industrial melanism and bacteria becoming antibiotic resistant are other examples of directional selection.

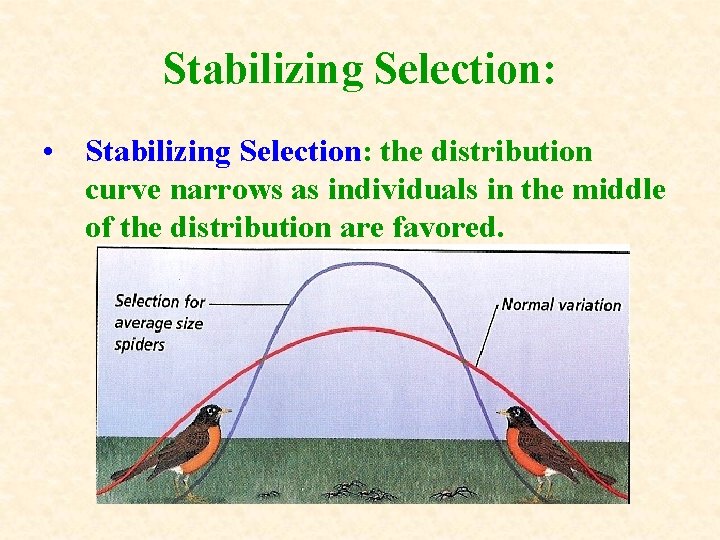

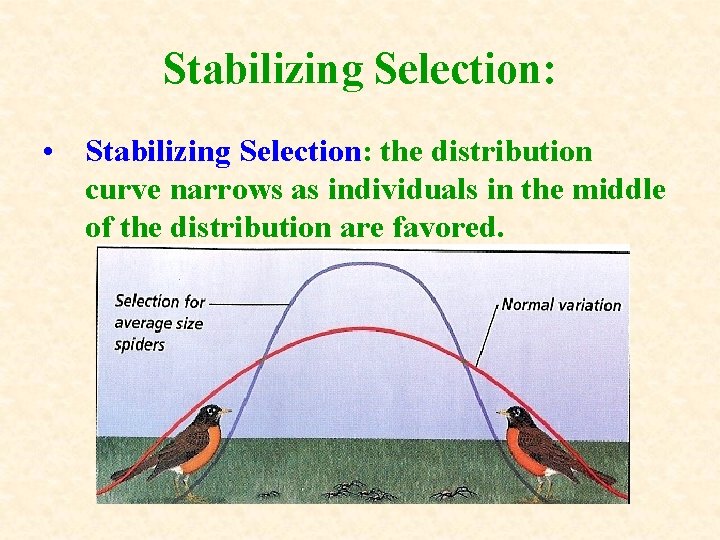

Three ways natural selection can effect the distribution of phenotypes: 2. Stabilizing Selection: the distribution curve narrows as individuals in the middle of the distribution are favored.

Stabilizing Selection: • Average phenotypes (individuals) are favorable and extremes are not. • Operates most of the time in most populations.

Stabilizing Selection: • Limits evolution as allele frequencies remain constant and the average individuals continue to dominate the population.

Stabilizing Selection: • For example: larger spiders are easily seen and eaten by predators. While smaller spiders find it difficult to find food. Therefore, average-sized spiders are favored by natural selection.

Stabilizing Selection: • Stabilizing Selection: the distribution curve narrows as individuals in the middle of the distribution are favored.

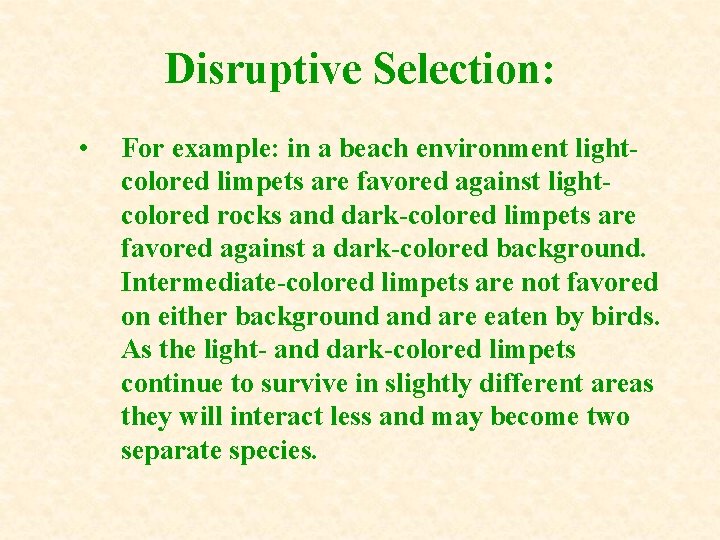

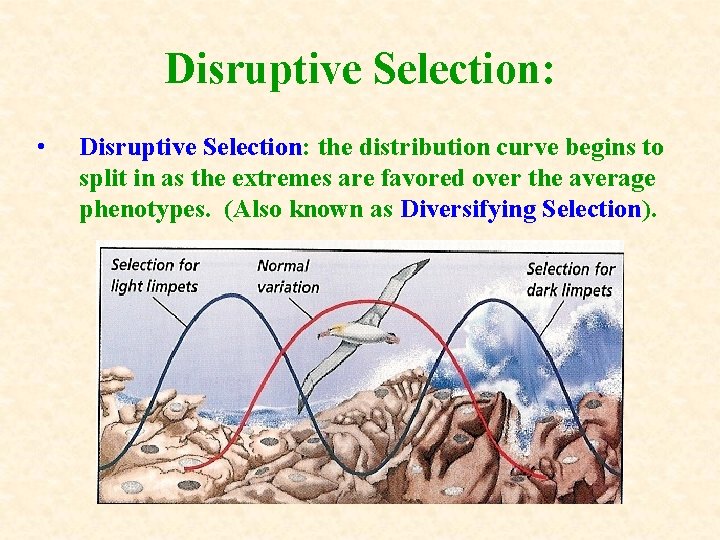

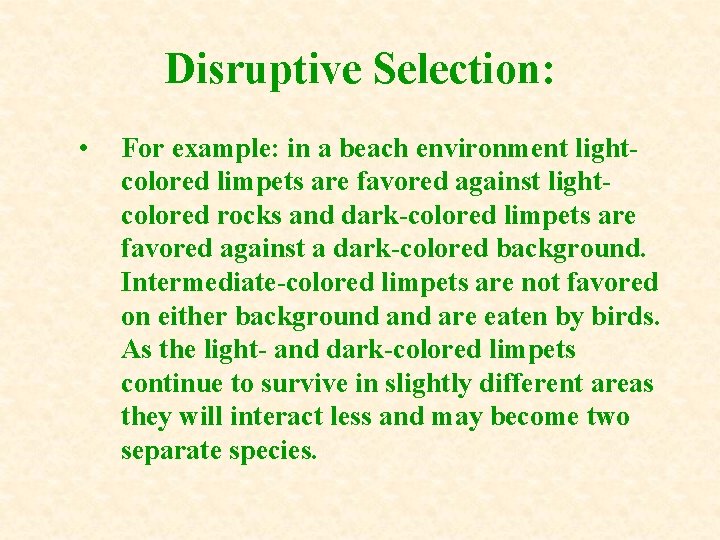

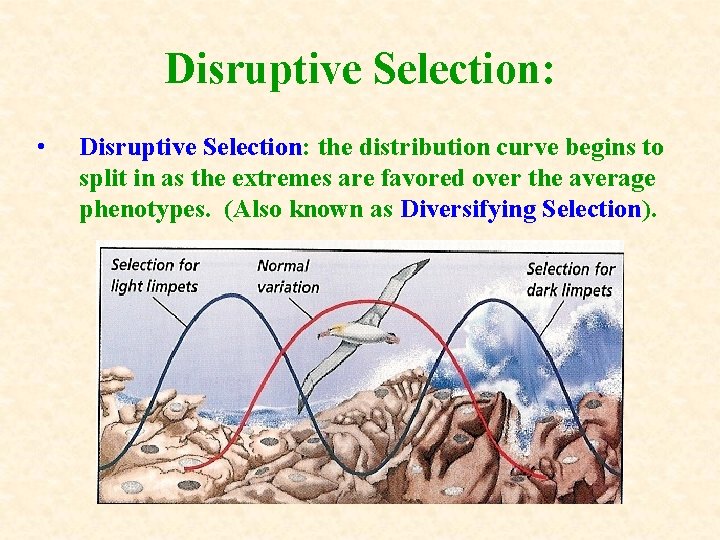

Three ways natural selection can effect the distribution of phenotypes: 3. Disruptive Selection: the distribution curve begins to split in as the extremes are favored over the average phenotypes. (Also known as Diversifying Selection).

Disruptive Selection: • Two opposite phenotypes are favored and the average phenotype is not. • Two subpopulations begin to form. If these subpopulations do not interbreed they can form two distinct species.

Disruptive Selection: • For example: in a beach environment lightcolored limpets are favored against lightcolored rocks and dark-colored limpets are favored against a dark-colored background. Intermediate-colored limpets are not favored on either background are eaten by birds. As the light- and dark-colored limpets continue to survive in slightly different areas they will interact less and may become two separate species.

Disruptive Selection: • Disruptive Selection: the distribution curve begins to split in as the extremes are favored over the average phenotypes. (Also known as Diversifying Selection).

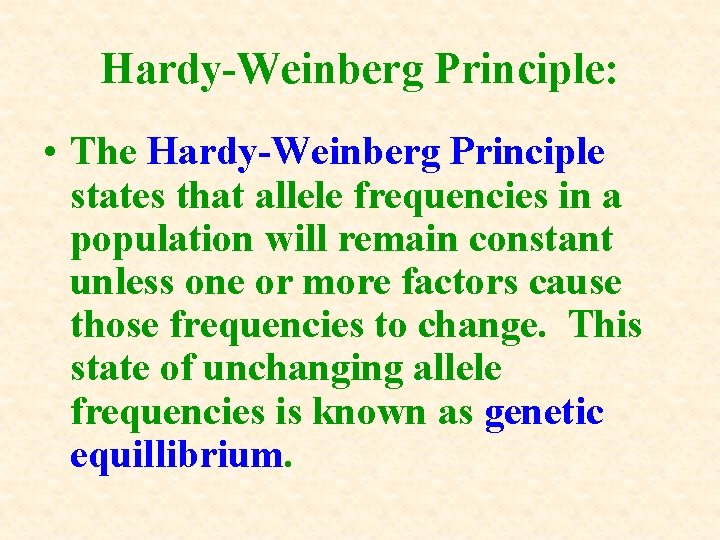

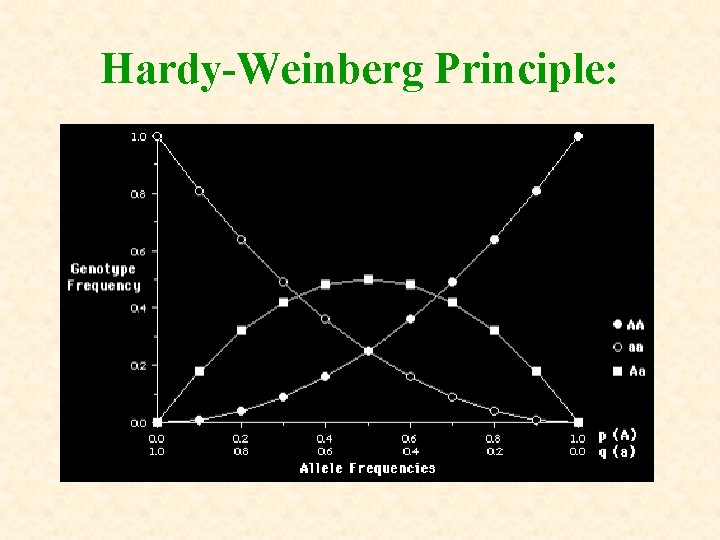

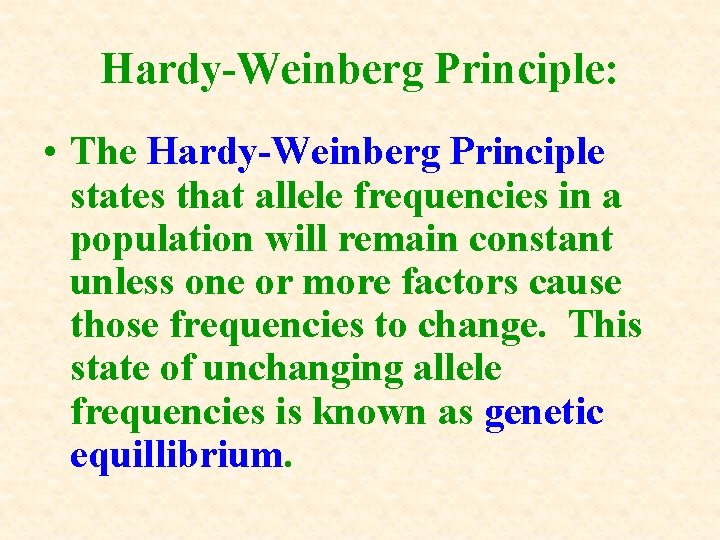

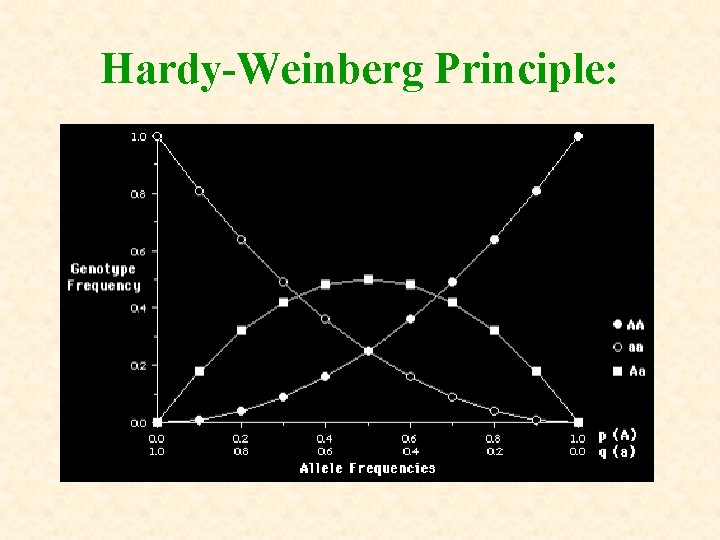

Hardy-Weinberg Principle: • The Hardy-Weinberg Principle states that allele frequencies in a population will remain constant unless one or more factors cause those frequencies to change. This state of unchanging allele frequencies is known as genetic equillibrium.

Hardy-Weinberg Principle:

Five conditions required to maintain genetic equilibrium (limit evolution of a population): 1. There must be random mating, in other words all individuals have the opportunity to produce offspring – rarely happens in nature.

Five conditions required to maintain genetic equilibrium (limit evolution of a population): 2. There must be a large population size. Genetic drift has less effect on large populations than on smaller populations.

Five conditions required to maintain genetic equilibrium (limit evolution of a population): 3. There must not be movement of individuals into or out of the population – no immigration or emigration.

Five conditions required to maintain genetic equilibrium (limit evolution of a population): 4. There must not be genetic mutations – no new alleles can be introduced.

Five conditions required to maintain genetic equilibrium (limit evolution of a population): 5. There must not be natural selection – meaning no traits are favored over other traits.

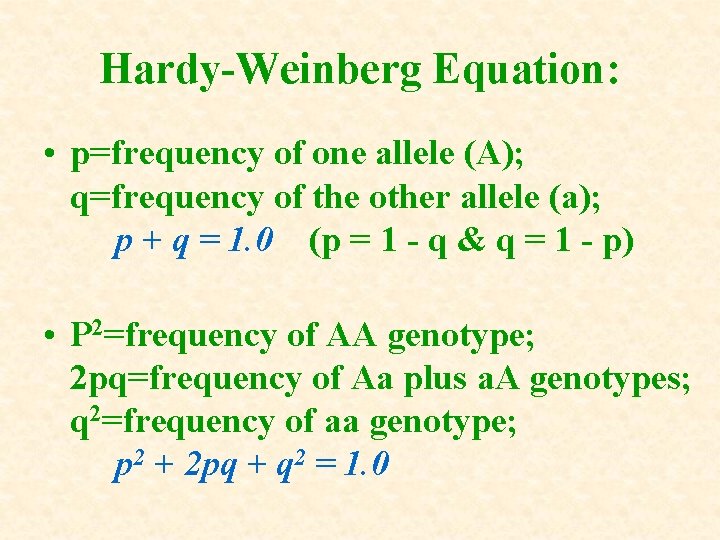

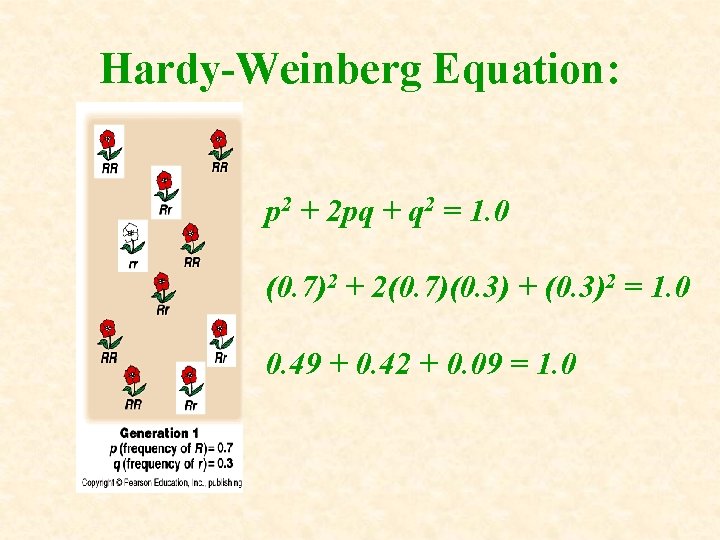

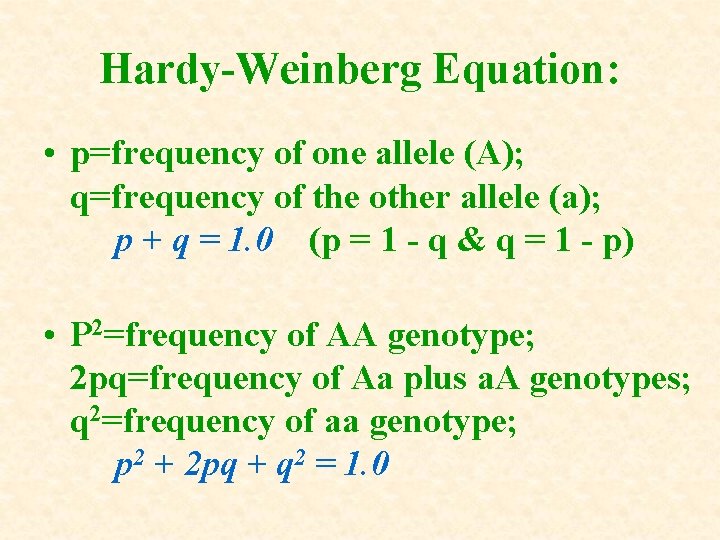

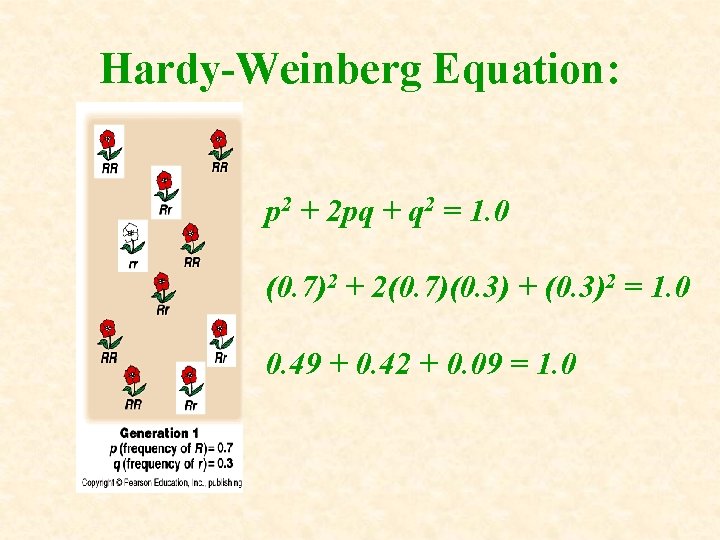

Hardy-Weinberg Equation: • p=frequency of one allele (A); q=frequency of the other allele (a); p + q = 1. 0 (p = 1 - q & q = 1 - p) • P 2=frequency of AA genotype; 2 pq=frequency of Aa plus a. A genotypes; q 2=frequency of aa genotype; p 2 + 2 pq + q 2 = 1. 0

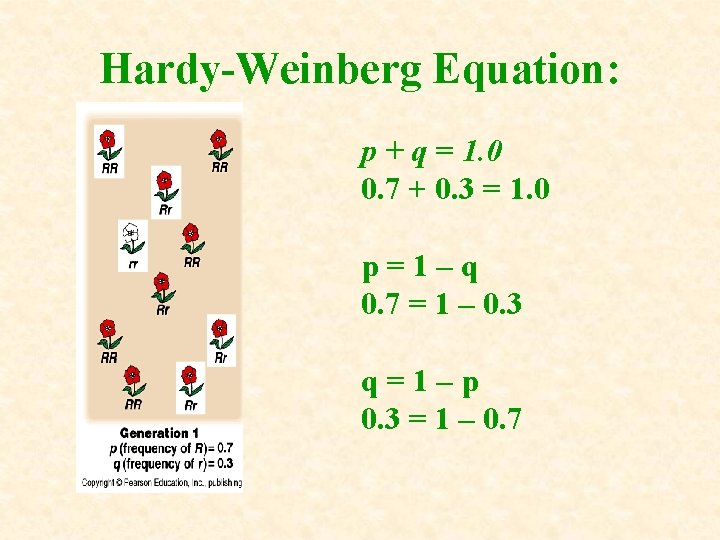

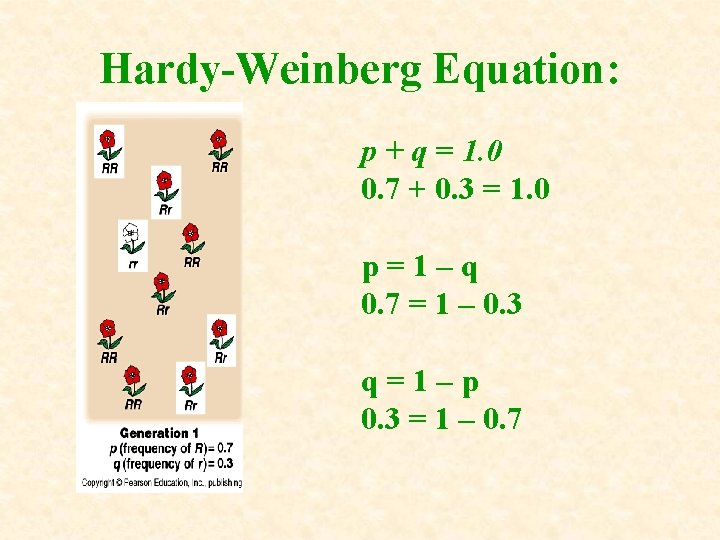

Hardy-Weinberg Equation: p + q = 1. 0 0. 7 + 0. 3 = 1. 0 p=1–q 0. 7 = 1 – 0. 3 q=1–p 0. 3 = 1 – 0. 7

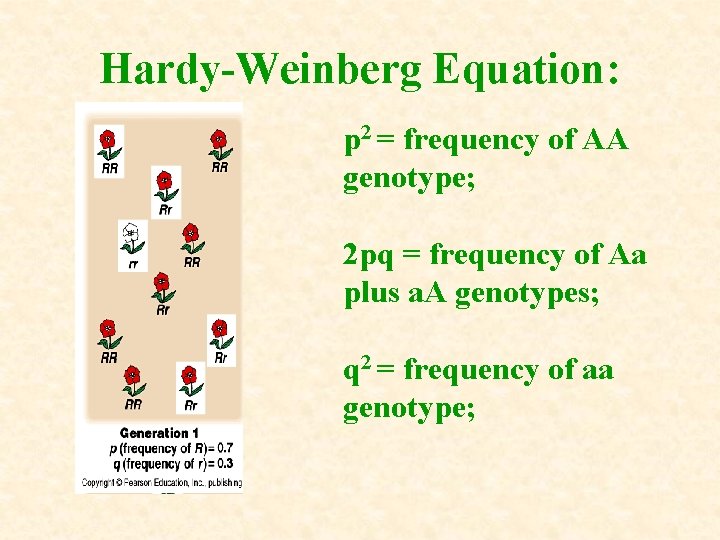

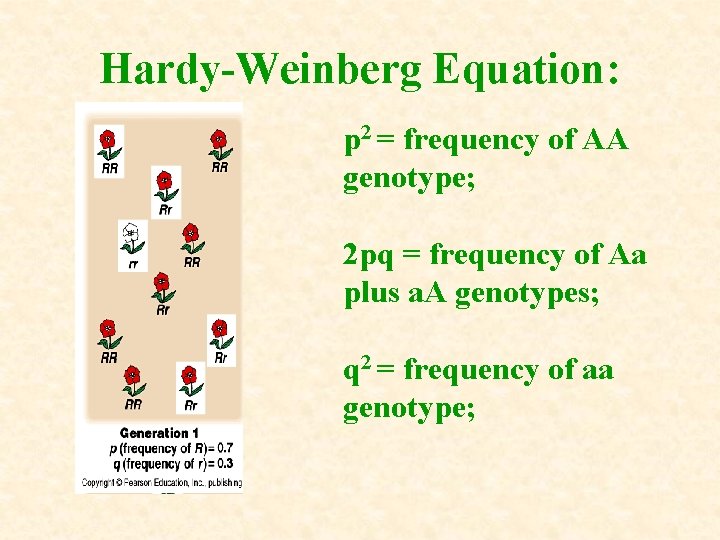

Hardy-Weinberg Equation: p 2 = frequency of AA genotype; 2 pq = frequency of Aa plus a. A genotypes; q 2 = frequency of aa genotype;

Hardy-Weinberg Equation: p 2 + 2 pq + q 2 = 1. 0 (0. 7)2 + 2(0. 7)(0. 3) + (0. 3)2 = 1. 0 0. 49 + 0. 42 + 0. 09 = 1. 0

Hardy-Weinberg Equation: • The five conditions of the Hardy. Weinberg principle are rarely met, so allele frequencies in the gene pool of a population do change from one generation to the next, resulting in evolution. We can now consider that any change of allele frequencies in a gene pool indicates that evolution has occurred.

Hardy-Weinberg Equation: • The Hardy-Weinberg principle proposes those factors that violate the conditions listed cause evolution. A Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium provides a baseline by which to judge whether evolution has occurred.

Hardy-Weinberg Equation: • Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium is a constancy of gene pool frequencies that remains across generations, and might best be found among stable populations with no natural selection or where selection is stabilizing.