Political Elites Democracy and Education Theory and Empirics

![This paper Ø A simple theoretical model [inspired by Acemoglu and Robinson (2006)] Ø This paper Ø A simple theoretical model [inspired by Acemoglu and Robinson (2006)] Ø](https://slidetodoc.com/presentation_image_h/e4c5ed571aafd25994b759434699aa82/image-5.jpg)

- Slides: 32

Political Elites, Democracy and Education: Theory and Empirics Mina Baliamoune-Lutz Department of Economics University of North Florida An earlier version of theoretical part in this paper was presented at the UN-WIDER Conference on ‘the Role of the Elites in Economic Development’, Helsinki (June 12 -13, 2009). The author is grateful to Tierry Verdier and James Robinson for useful comments. An older version of theoretical part is in ERF working paper no. 790 (2014).

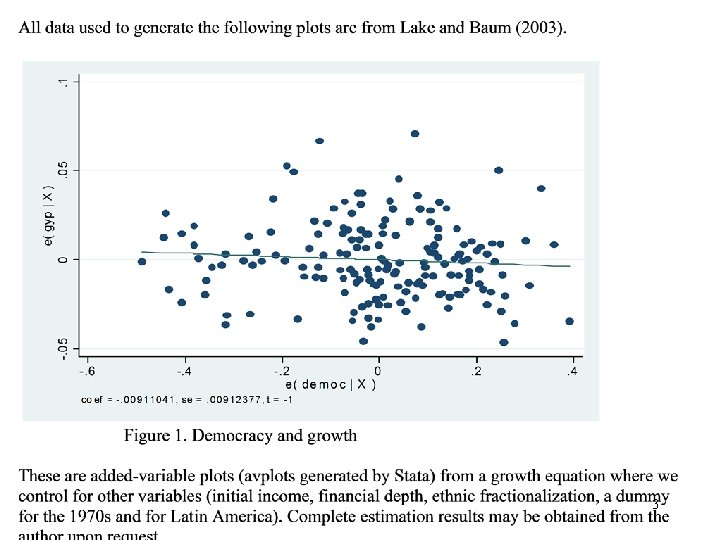

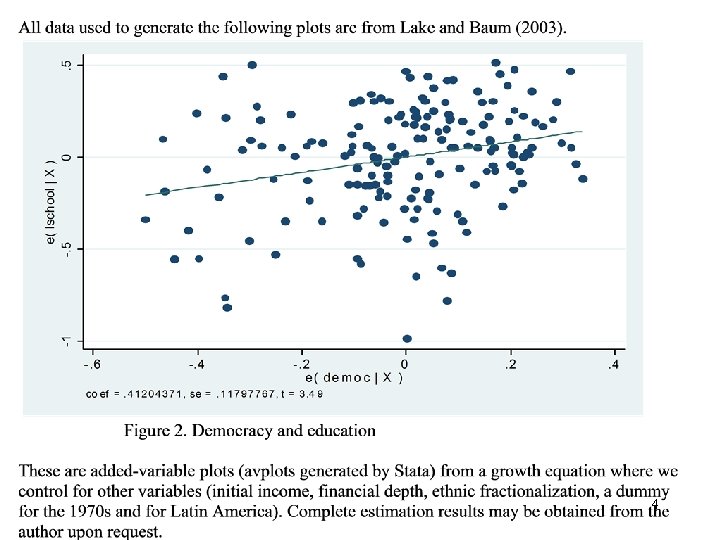

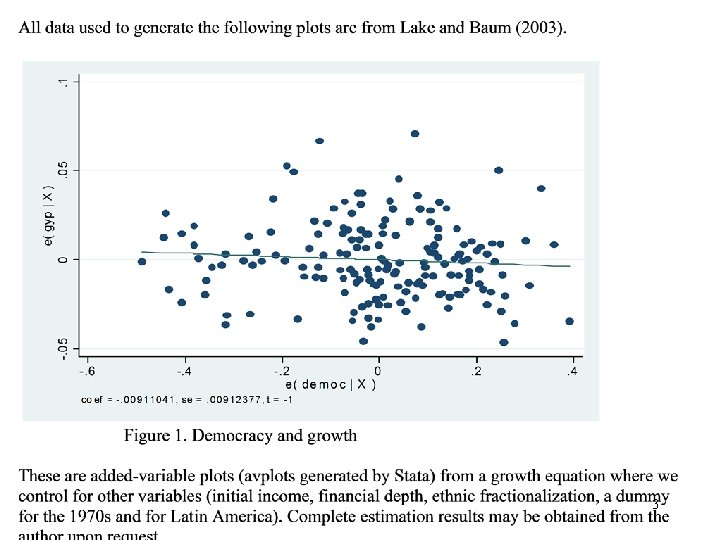

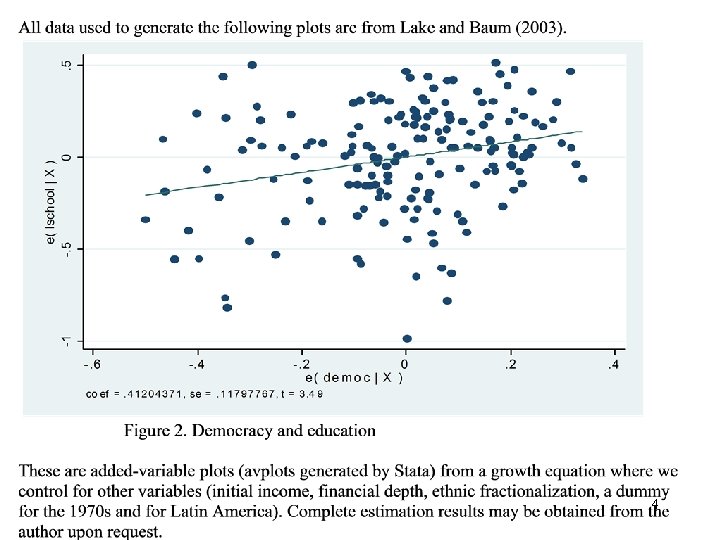

Motivation § The role of human capital in growth and development. § Yet, mass education may be viewed as a threat to the political elites. § The association between growth and development, and democracy: Mixed evidence. § The association between democracy and education (see Acemoglu et al. , 2005; Glaeser et al. , 2007): Mixed empirical evidence. § The interplay of political elites and education of the masses and the implications of this interplay for growth and income distribution (Perotti, 1993 and 1996; Galor and Zira, 1993; Saint-Paul and Verdier, 1993; Bourguignon and Verdier, 2000). 2

3

4

![This paper Ø A simple theoretical model inspired by Acemoglu and Robinson 2006 Ø This paper Ø A simple theoretical model [inspired by Acemoglu and Robinson (2006)] Ø](https://slidetodoc.com/presentation_image_h/e4c5ed571aafd25994b759434699aa82/image-5.jpg)

This paper Ø A simple theoretical model [inspired by Acemoglu and Robinson (2006)] Ø tries to identify the conditions under which the elite support democracy and education. • The control of de facto political power is the driving force behind the elites’ decisions. Øhope to offer useful insights into the cross-country differences in the elites’ preferences for investing in the education of the masses and democratization. 5

Ø The model differs from that in Acemoglu and Robinson (2006) in two important ways. 1. Assume that de facto political power can be generated from a general function. The main result (equation (11)) in Acemoglu and Robinson’s paper assumes that de facto political power is generated linearly. – I introduce this complication in order to examine cases where the elite is more or less than linearly productive in retaining power. This leads to a case where the elite may end up with more de facto power in more de jure democracy. 6

Ø The model differs from that in Acemoglu and Robinson (2006) in two important ways. 2. I account for the elites’ support of citizens’ education. Higher levels of spending on education reduce the elites’ rents directly and increase rents through positive externalities, but more education raises citizens’ political participation and, thus, may increase de jure political power of the citizens (see Bourguignon and Verdier, 2000; and Glaeser et al. , 2007). 7

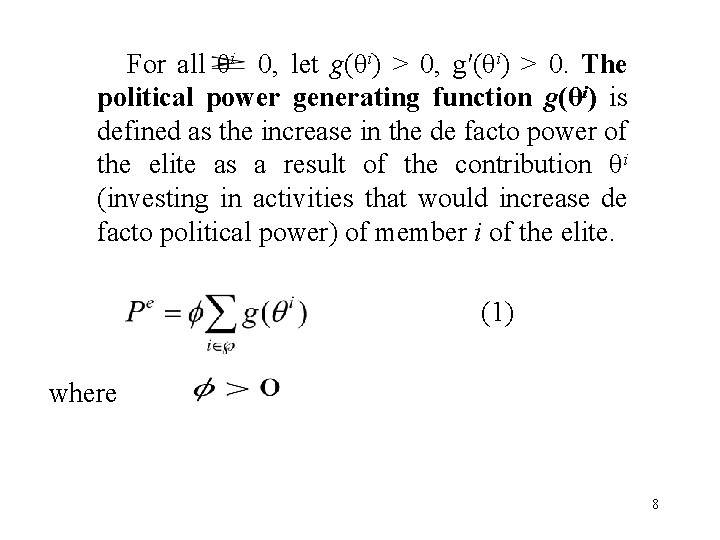

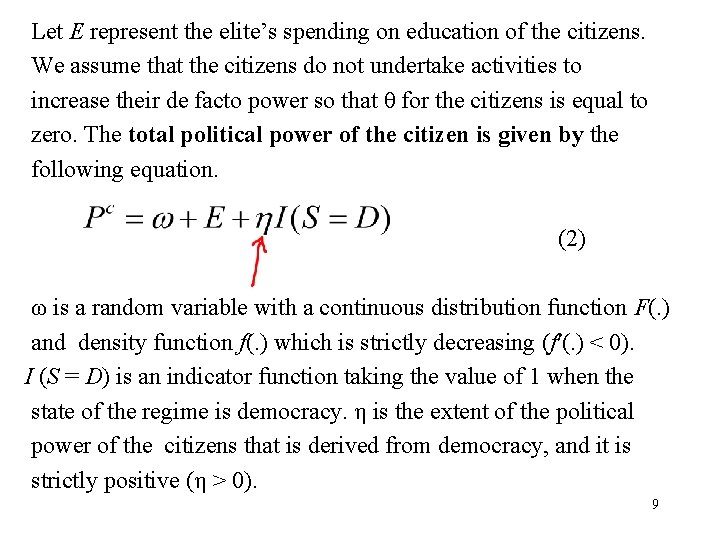

For all θi 0, let g(θi) > 0, g′(θi) > 0. The political power generating function g(θi) is defined as the increase in the de facto power of the elite as a result of the contribution θi (investing in activities that would increase de facto political power) of member i of the elite. (1) where 8

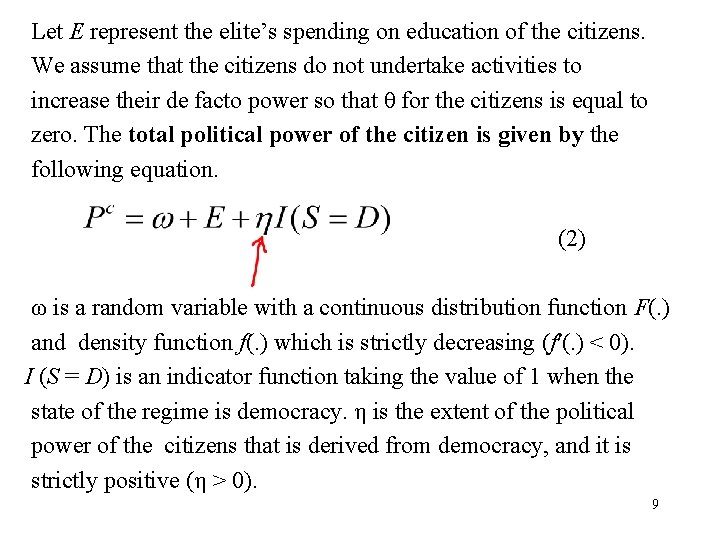

Let E represent the elite’s spending on education of the citizens. We assume that the citizens do not undertake activities to increase their de facto power so that θ for the citizens is equal to zero. The total political power of the citizen is given by the following equation. (2) ω is a random variable with a continuous distribution function F(. ) and density function f(. ) which is strictly decreasing (f′(. ) < 0). I (S = D) is an indicator function taking the value of 1 when the state of the regime is democracy. η is the extent of the political power of the citizens that is derived from democracy, and it is strictly positive (η > 0). 9

Equation (2) shows that the citizens can increase their political power from three different sources. 1. The citizens may manage to solve the collective action problem and come to a consensus that might allow them to have greater de facto political power (with ω having a positive effect). 2. More spending by the elites on education (E) enhances citizens’ political participation. 3. Third, more democracy (a higher value for η) implies more (de jure) political power for citizens. 10

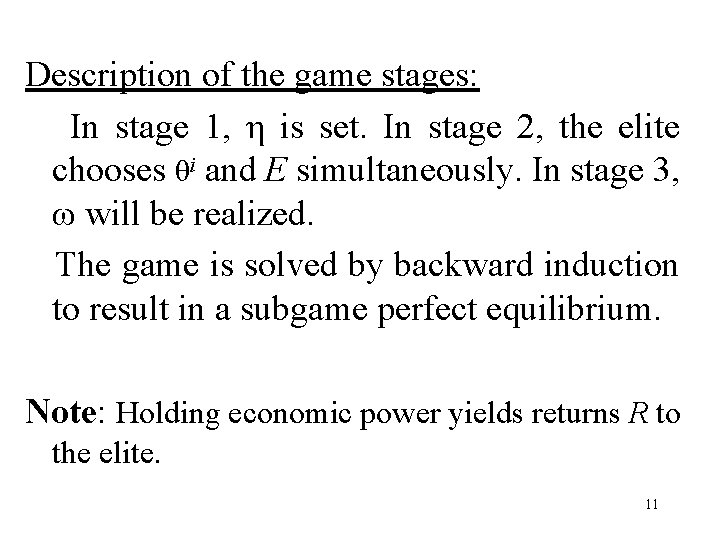

Description of the game stages: In stage 1, η is set. In stage 2, the elite chooses θi and E simultaneously. In stage 3, ω will be realized. The game is solved by backward induction to result in a subgame perfect equilibrium. Note: Holding economic power yields returns R to the elite. 11

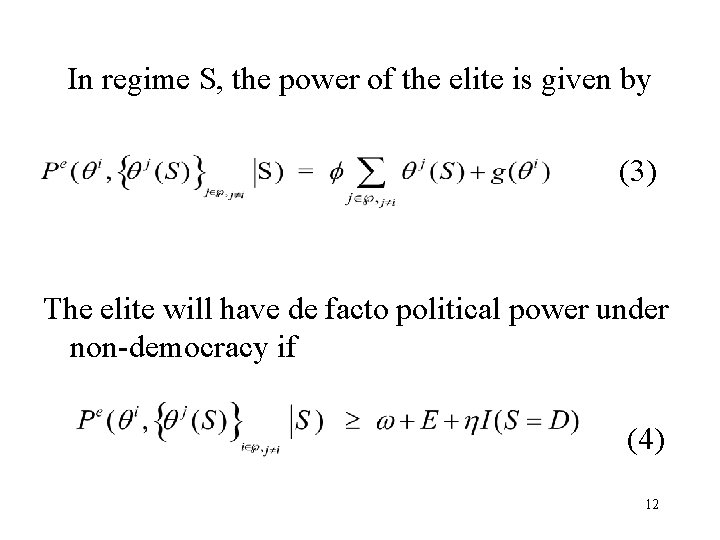

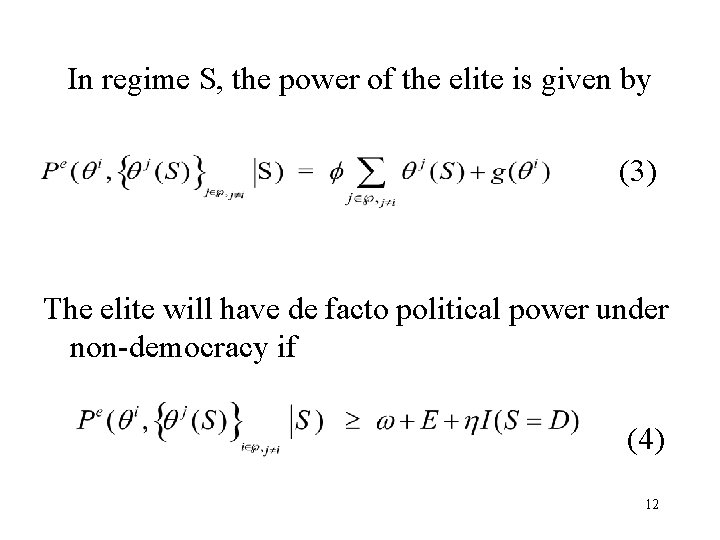

In regime S, the power of the elite is given by (3) The elite will have de facto political power under non-democracy if (4) 12

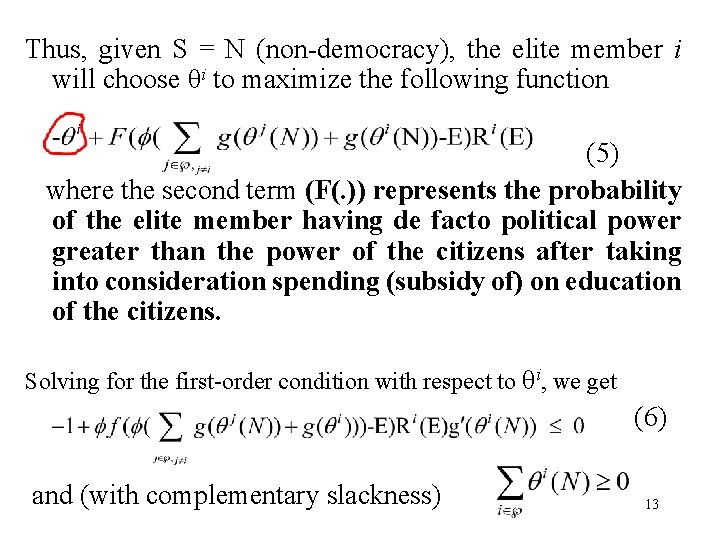

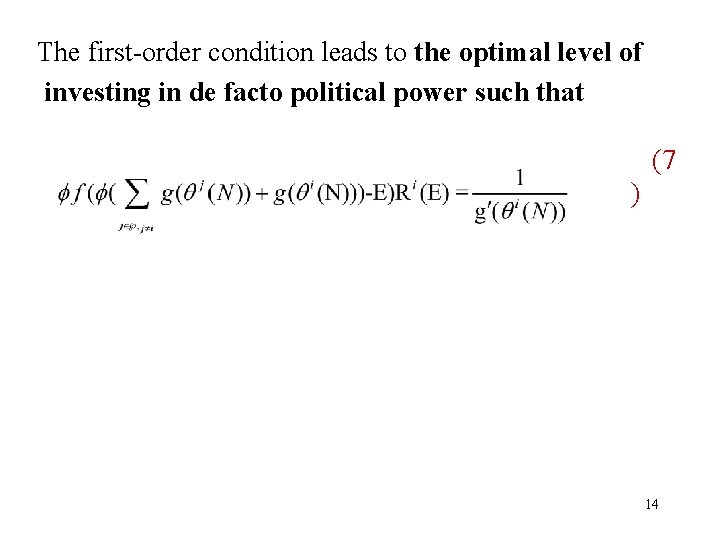

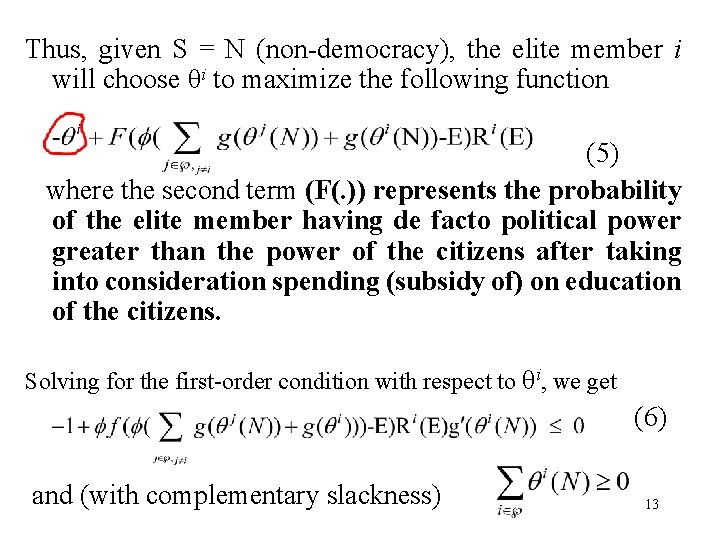

Thus, given S = N (non-democracy), the elite member i will choose θi to maximize the following function (5) where the second term (F(. )) represents the probability of the elite member having de facto political power greater than the power of the citizens after taking into consideration spending (subsidy of) on education of the citizens. Solving for the first-order condition with respect to θi, we get (6) and (with complementary slackness) 13

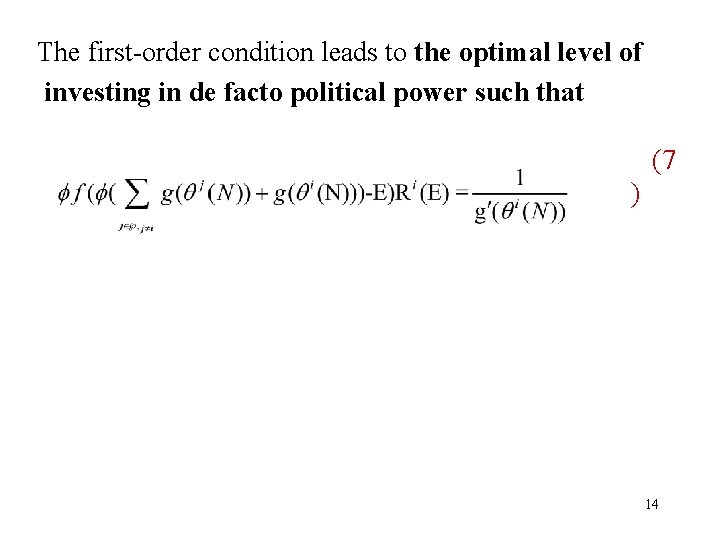

The first-order condition leads to the optimal level of investing in de facto political power such that (7 ) 14

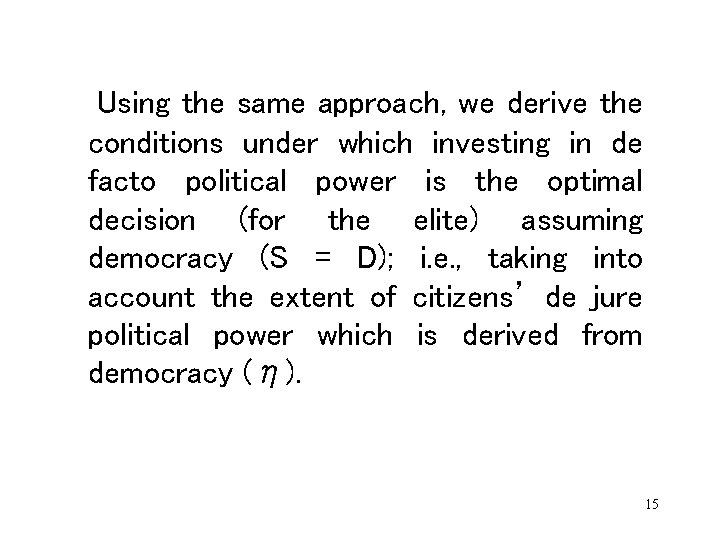

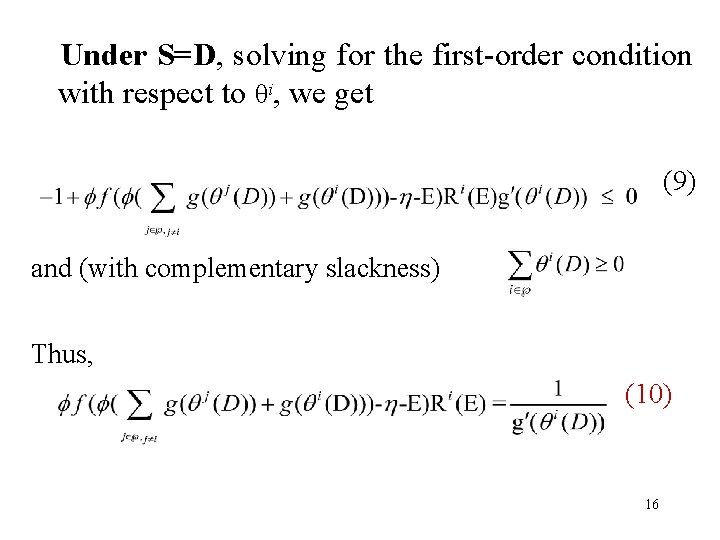

Using the same approach, we derive the conditions under which investing in de facto political power is the optimal decision (for the elite) assuming democracy (S = D); i. e. , taking into account the extent of citizens’ de jure political power which is derived from democracy (η). 15

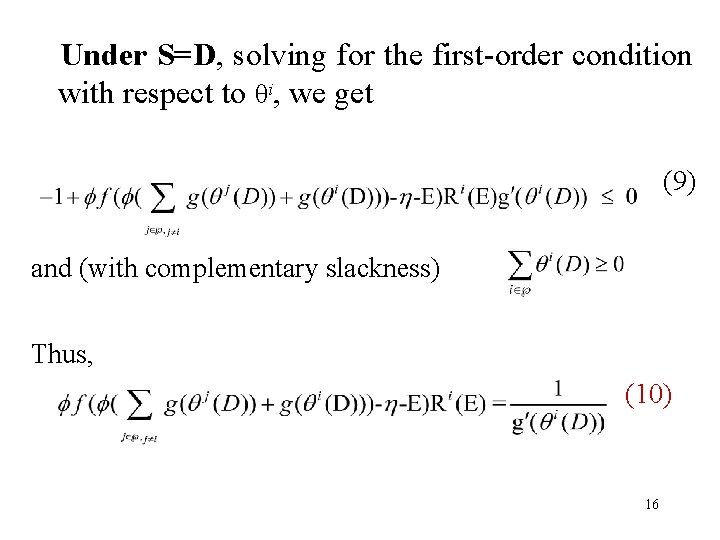

Under S=D, solving for the first-order condition with respect to θi, we get (9) and (with complementary slackness) Thus, (10) 16

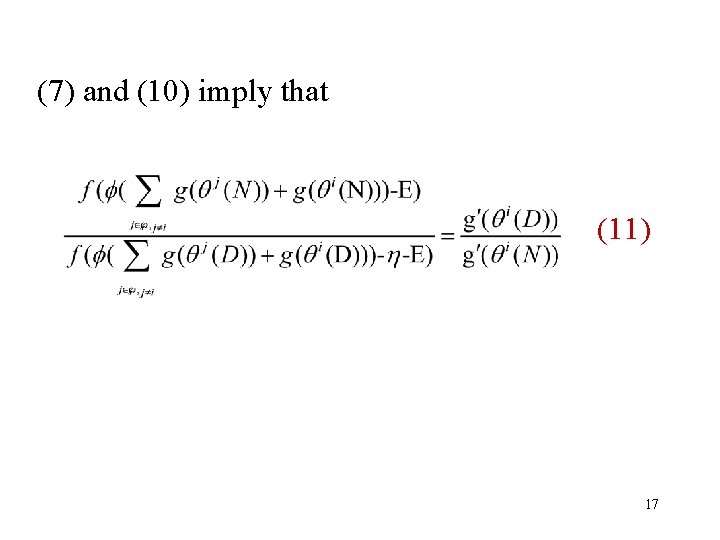

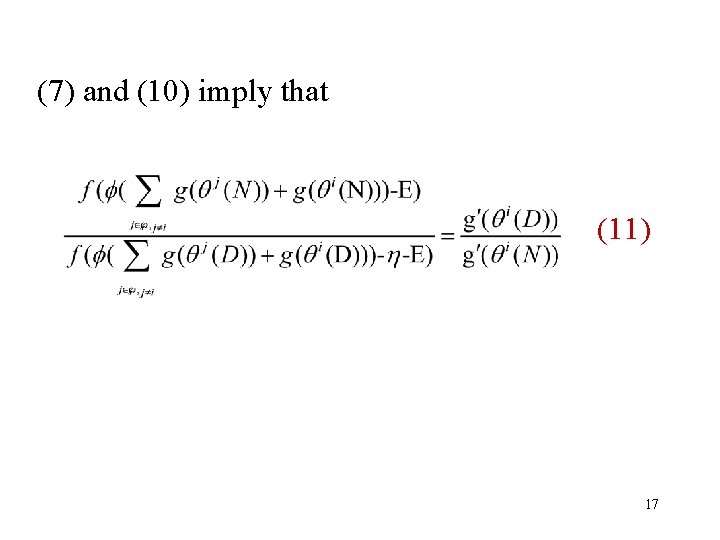

(7) and (10) imply that (11) 17

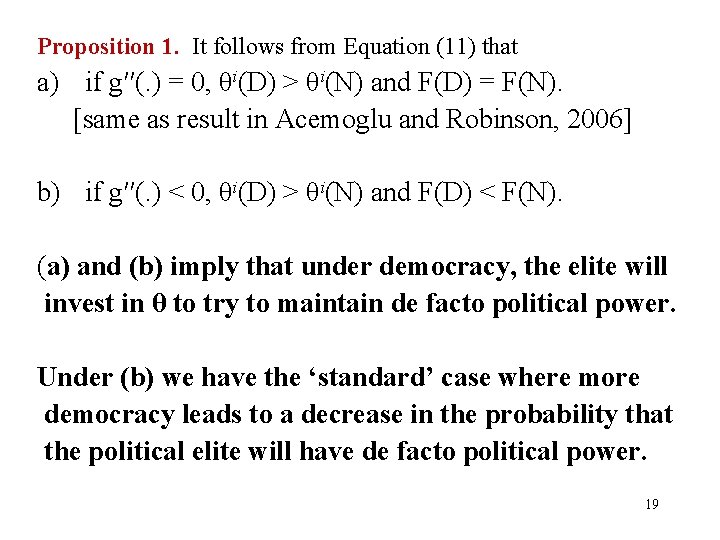

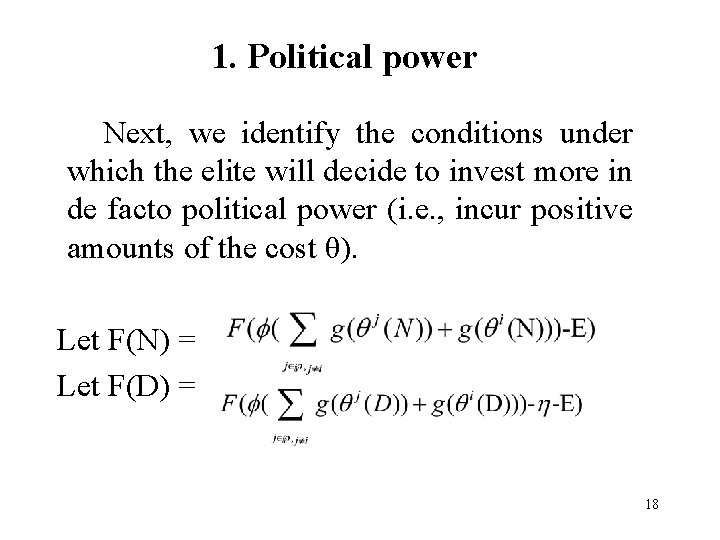

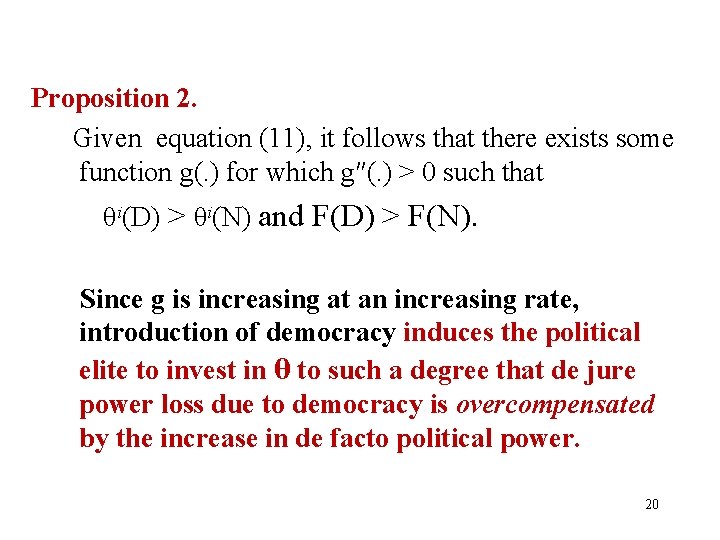

1. Political power Next, we identify the conditions under which the elite will decide to invest more in de facto political power (i. e. , incur positive amounts of the cost θ). Let F(N) = Let F(D) = 18

Proposition 1. It follows from Equation (11) that a) if g′′(. ) = 0, θi(D) > θi(N) and F(D) = F(N). [same as result in Acemoglu and Robinson, 2006] b) if g′′(. ) < 0, θi(D) > θi(N) and F(D) < F(N). (a) and (b) imply that under democracy, the elite will invest in θ to try to maintain de facto political power. Under (b) we have the ‘standard’ case where more democracy leads to a decrease in the probability that the political elite will have de facto political power. 19

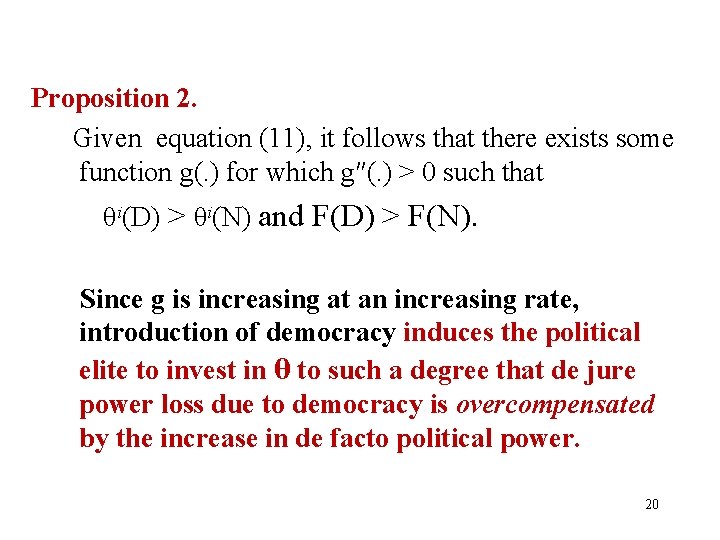

Proposition 2. Given equation (11), it follows that there exists some function g(. ) for which g″(. ) > 0 such that θi(D) > θi(N) and F(D) > F(N). Since g is increasing at an increasing rate, introduction of democracy induces the political elite to invest in θ to such a degree that de jure power loss due to democracy is overcompensated by the increase in de facto political power. 20

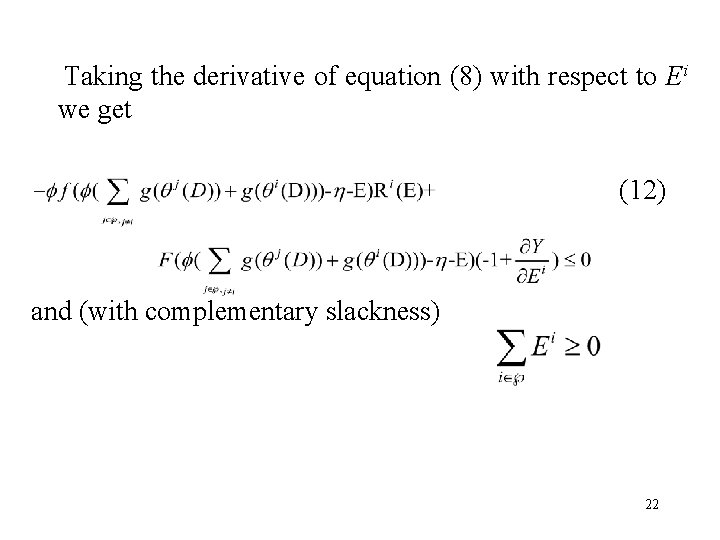

2. Education Examine how the elite chooses the amount of spending on the education of citizens. Rent (R) is defined as income minus total spending on education. Assumptions: 1. Imperfect capital markets. 2. Education (E) directly increases productivity and total product/income (Y). 21

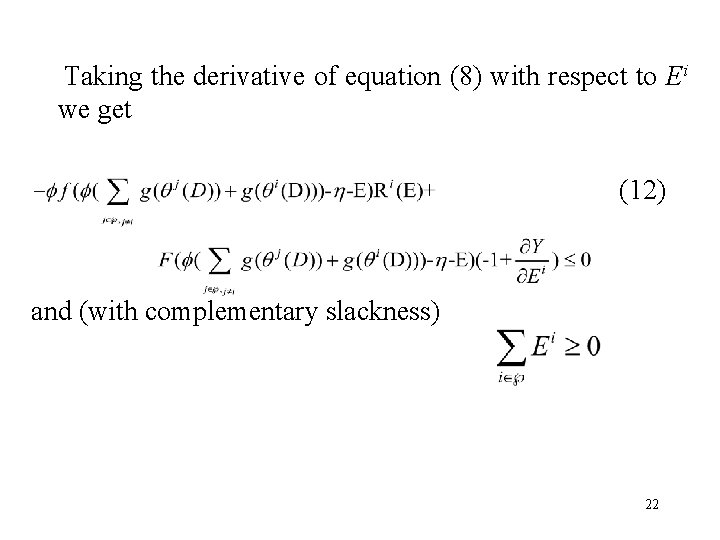

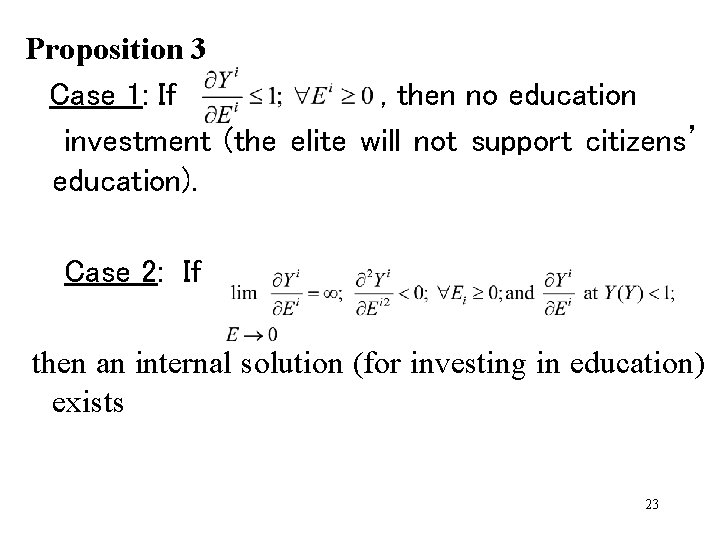

Taking the derivative of equation (8) with respect to Ei we get (12) and (with complementary slackness) 22

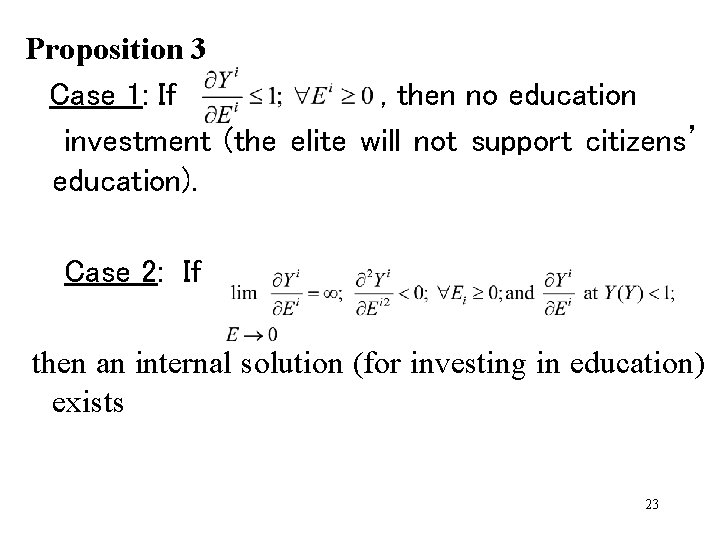

Proposition 3 Case 1: If , then no education investment (the elite will not support citizens’ education). Case 2: If then an internal solution (for investing in education) exists 23

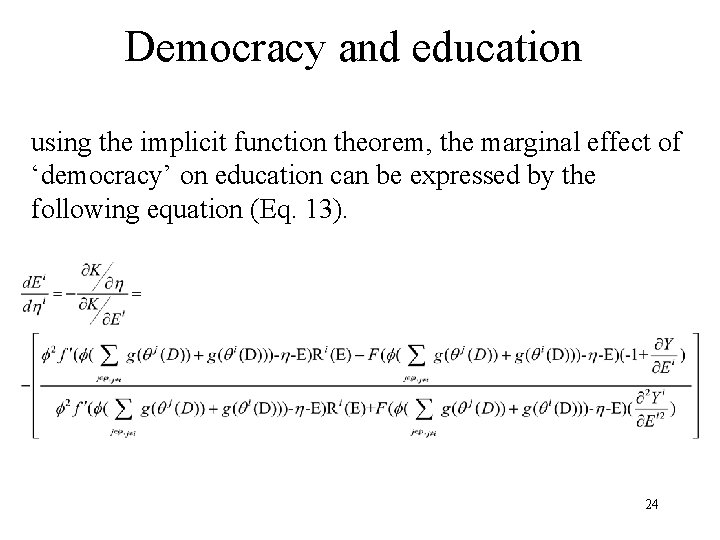

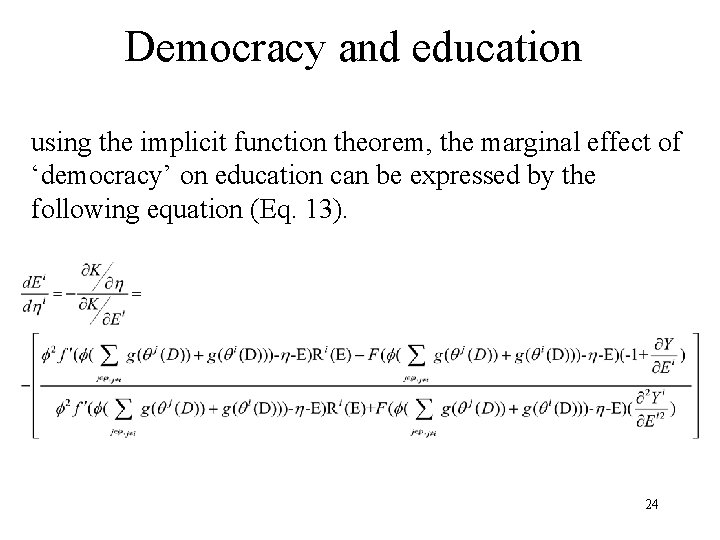

Democracy and education using the implicit function theorem, the marginal effect of ‘democracy’ on education can be expressed by the following equation (Eq. 13). 24

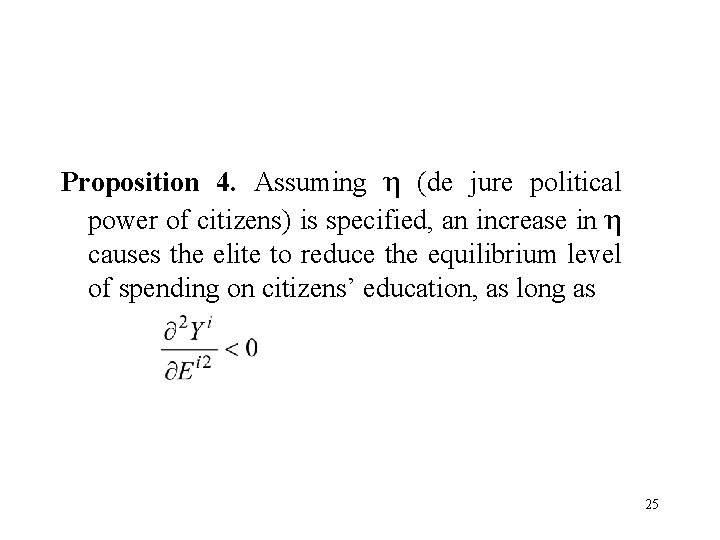

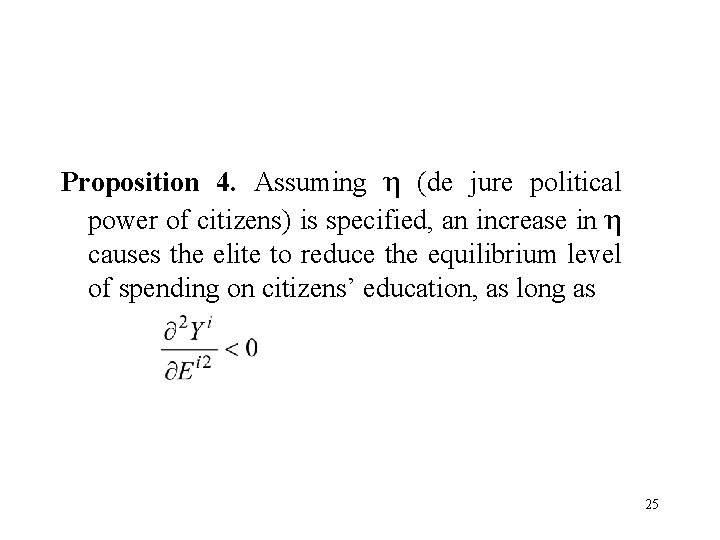

Proposition 4. Assuming η (de jure political power of citizens) is specified, an increase in η causes the elite to reduce the equilibrium level of spending on citizens’ education, as long as 25

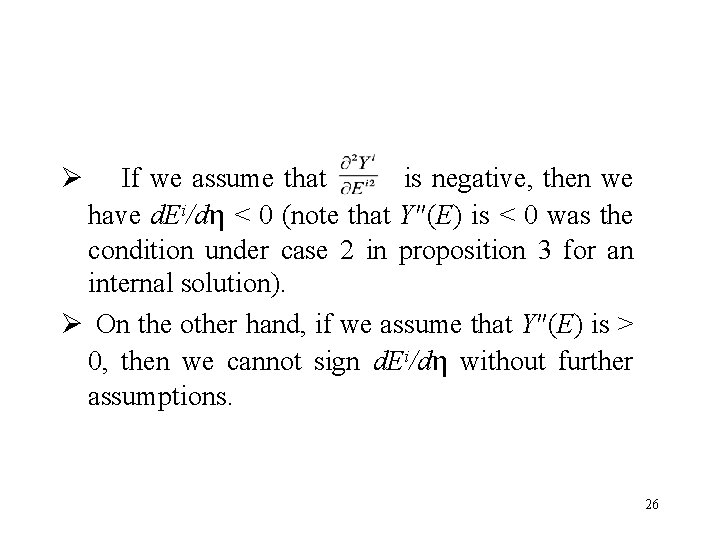

Ø If we assume that is negative, then we have d. Ei/dη < 0 (note that Y″(E) is < 0 was the condition under case 2 in proposition 3 for an internal solution). Ø On the other hand, if we assume that Y″(E) is > 0, then we cannot sign d. Ei/dη without further assumptions. 26

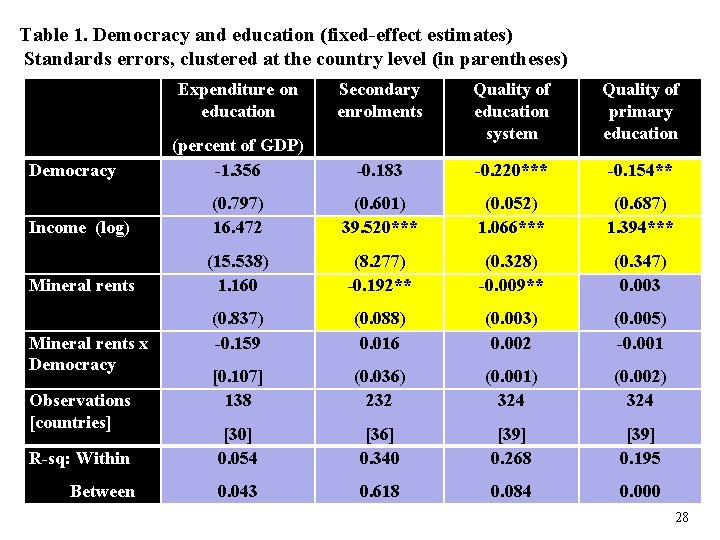

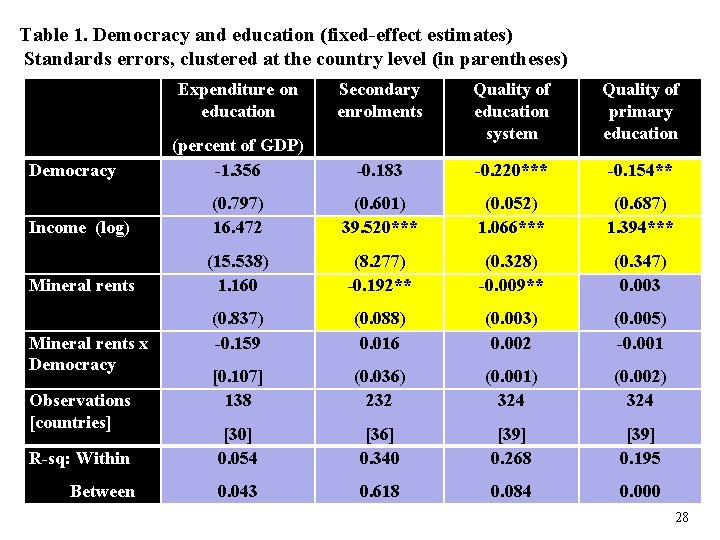

Preliminary empirical results • Test proposition 4 using the fixed-effects estimator and panel data from Africa, covering the period from 2007 to 2017. • Link between democracy and indicators of the quantity and quality of education after controlling for the role of income and mineral rents (proxy for the elite) as well as the interplay of mineral rents and democracy. 27

Table 1. Democracy and education (fixed-effect estimates) Standards errors, clustered at the country level (in parentheses) Expenditure on education Secondary enrolments (percent of GDP) -1. 356 Quality of education system Quality of primary education -0. 183 -0. 220*** -0. 154** Income (log) (0. 797) 16. 472 (0. 601) 39. 520*** (0. 052) 1. 066*** (0. 687) 1. 394*** Mineral rents (15. 538) 1. 160 (8. 277) -0. 192** (0. 328) -0. 009** (0. 347) 0. 003 (0. 837) -0. 159 (0. 088) 0. 016 (0. 003) 0. 002 (0. 005) -0. 001 [0. 107] 138 (0. 036) 232 (0. 001) 324 (0. 002) 324 R-sq: Within [30] 0. 054 [36] 0. 340 [39] 0. 268 [39] 0. 195 Between 0. 043 0. 618 0. 084 0. 000 Democracy Mineral rents x Democracy Observations [countries] 28

Summary and discussion ü Together, the four propositions suggest that the political elite may find an optimal η, then decide on the levels of investment in de facto political power (θ) and citizens’ education (E), given the other parameters. ü Under Proposition 1, the elite decides to invest in de facto political power to have control of overall political power while the citizens are offered de jure power (democracy). ü Proposition 2 implies that the elite may overinvest in securing de facto power to the point where the probability to have de facto political power is greater under democracy. § If the de facto power is used to maintain economic institutions that favor the elites, we may have inefficiencies and lower growth (see Acemoglu and Robinson, 2008). 29

ü Proposition 3 implies that the elite’s decision to support mass education depends on whether education has significant strong effects on the elite’s rents. ü An interesting corollary of Proposition 4 is that if d. Ei/dη is negative, education and democracy (political reform) could be viewed by the elite as substitutes. ü Under which circumstances would spending on education have strong positive effects on elites’ income (rents)? The answer (speculation? ) may depend (at least in part) on the stages of development and the size of the middle class. 30

Ø In theory, we cannot unambiguously determine what happens to democracy and spending on education when the elites simultaneously decide education and democracy. Ø An important implication for empirical analysis is that when examining cross-country experiences we might find conflicting results depending on the countries studied. 31

Conclusion Ø The model could be used to test empirically how democracy and education (and income) could be jointly determined by the size and de facto political power of the elite. Ø Although the present model is simple and static in nature, it should provide a way of reconciling the conflicting evidence on the links between democracy and education. 32