Planning for and Instructing Multilevel Classes Using the

- Slides: 60

Planning for and Instructing Multilevel Classes Using the Canadian Language Benchmarks 1

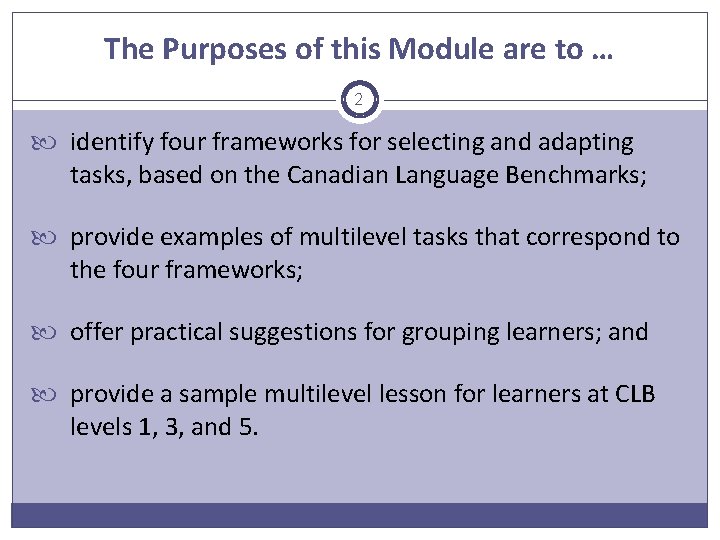

The Purposes of this Module are to … 2 identify four frameworks for selecting and adapting tasks, based on the Canadian Language Benchmarks; provide examples of multilevel tasks that correspond to the four frameworks; offer practical suggestions for grouping learners; and provide a sample multilevel lesson for learners at CLB levels 1, 3, and 5.

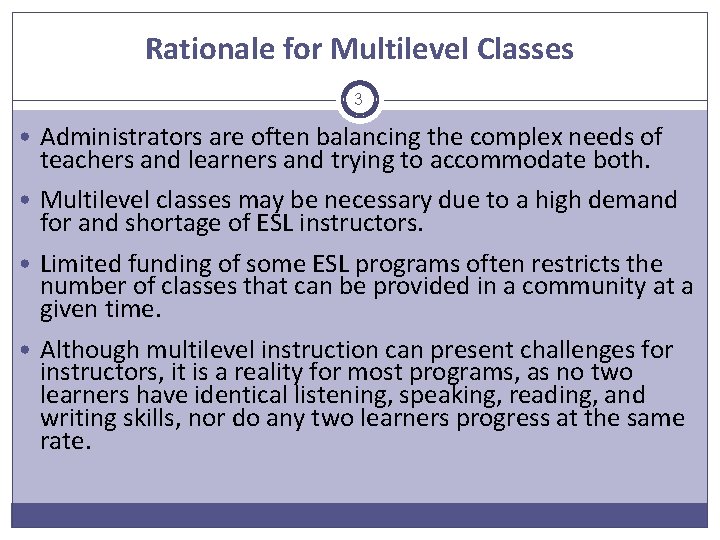

Rationale for Multilevel Classes 3 • Administrators are often balancing the complex needs of teachers and learners and trying to accommodate both. • Multilevel classes may be necessary due to a high demand for and shortage of ESL instructors. • Limited funding of some ESL programs often restricts the number of classes that can be provided in a community at a given time. • Although multilevel instruction can present challenges for instructors, it is a reality for most programs, as no two learners have identical listening, speaking, reading, and writing skills, nor do any two learners progress at the same rate.

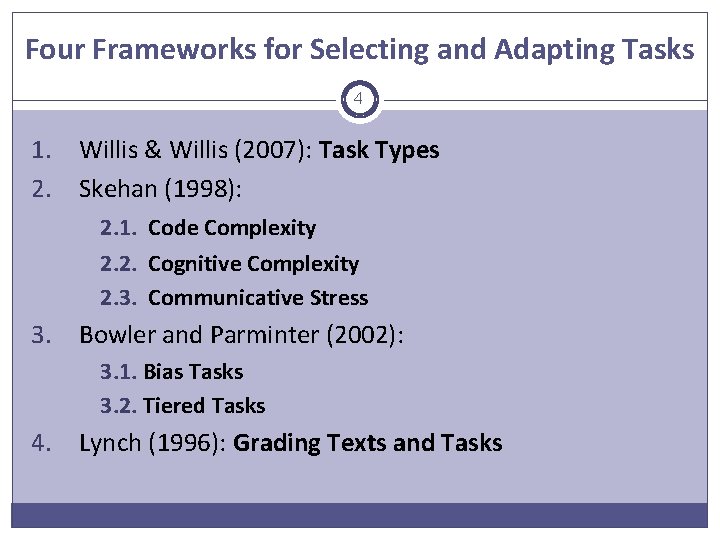

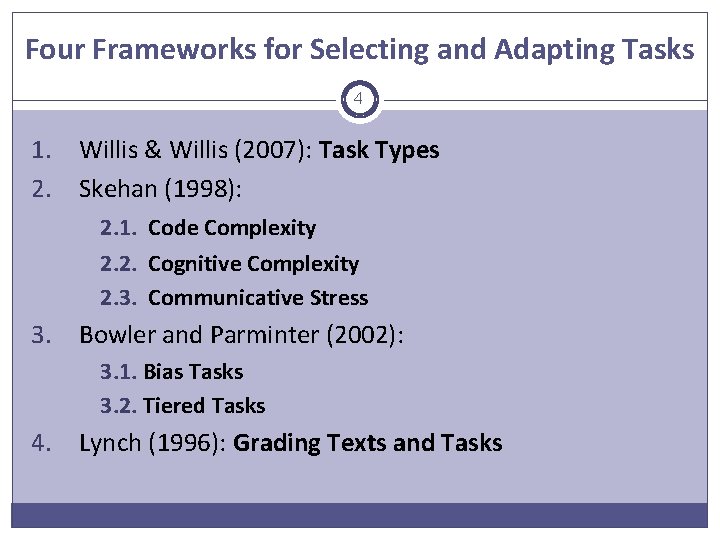

Four Frameworks for Selecting and Adapting Tasks 4 1. Willis & Willis (2007): Task Types 2. Skehan (1998): 2. 1. Code Complexity 2. 2. Cognitive Complexity 2. 3. Communicative Stress 3. Bowler and Parminter (2002): 3. 1. Bias Tasks 3. 2. Tiered Tasks 4. Lynch (1996): Grading Texts and Tasks

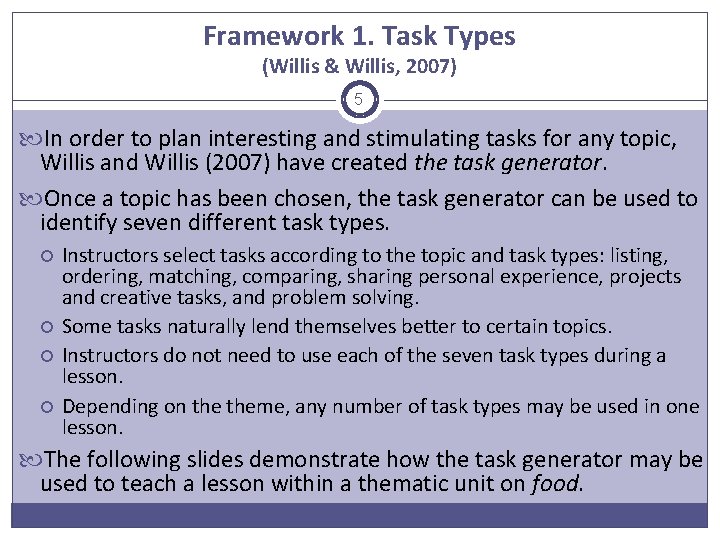

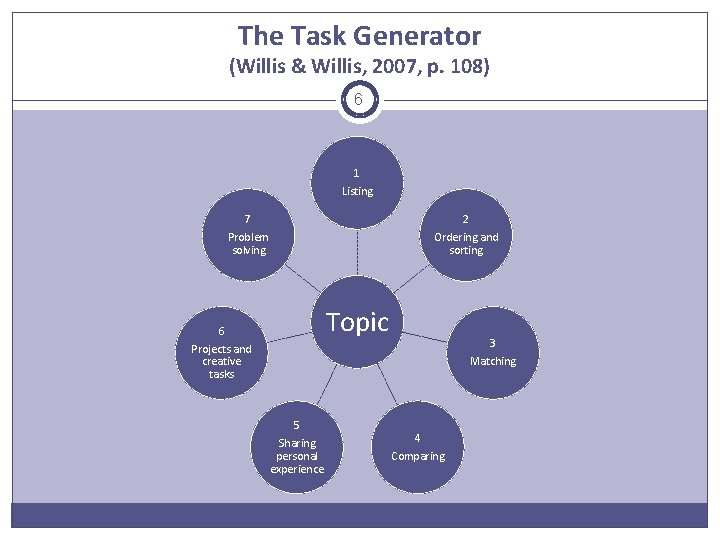

Framework 1. Task Types (Willis & Willis, 2007) 5 In order to plan interesting and stimulating tasks for any topic, Willis and Willis (2007) have created the task generator. Once a topic has been chosen, the task generator can be used to identify seven different task types. Instructors select tasks according to the topic and task types: listing, ordering, matching, comparing, sharing personal experience, projects and creative tasks, and problem solving. Some tasks naturally lend themselves better to certain topics. Instructors do not need to use each of the seven task types during a lesson. Depending on theme, any number of task types may be used in one lesson. The following slides demonstrate how the task generator may be used to teach a lesson within a thematic unit on food.

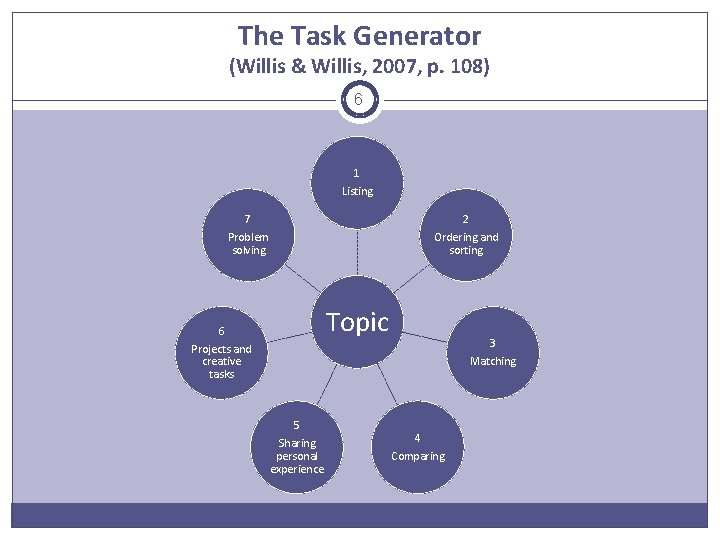

The Task Generator (Willis & Willis, 2007, p. 108) 6 1 Listing 7 Problem solving 2 Ordering and sorting Topic 6 Projects and creative tasks 5 Sharing personal experience 3 Matching 4 Comparing

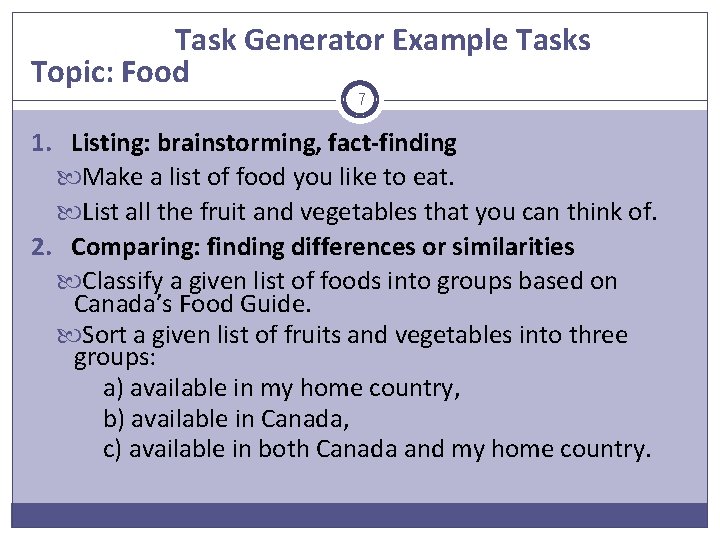

Task Generator Example Tasks Topic: Food 7 1. Listing: brainstorming, fact-finding Make a list of food you like to eat. List all the fruit and vegetables that you can think of. 2. Comparing: finding differences or similarities Classify a given list of foods into groups based on Canada’s Food Guide. Sort a given list of fruits and vegetables into three groups: a) available in my home country, b) available in Canada, c) available in both Canada and my home country.

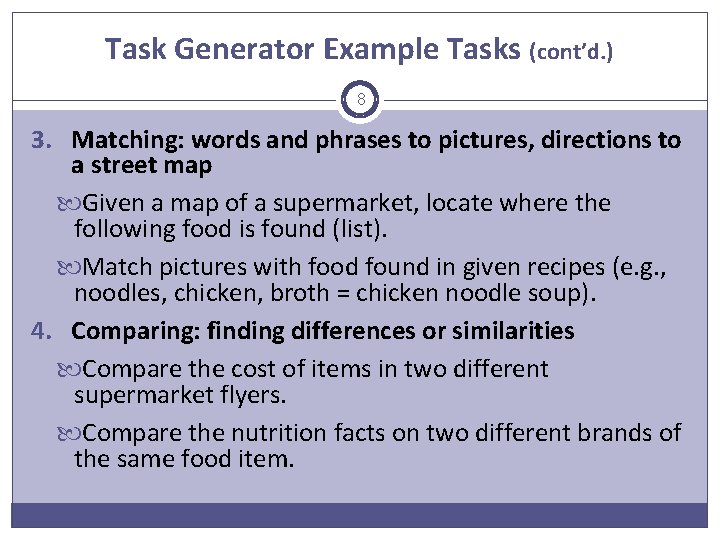

Task Generator Example Tasks (cont’d. ) 8 3. Matching: words and phrases to pictures, directions to a street map Given a map of a supermarket, locate where the following food is found (list). Match pictures with food found in given recipes (e. g. , noodles, chicken, broth = chicken noodle soup). 4. Comparing: finding differences or similarities Compare the cost of items in two different supermarket flyers. Compare the nutrition facts on two different brands of the same food item.

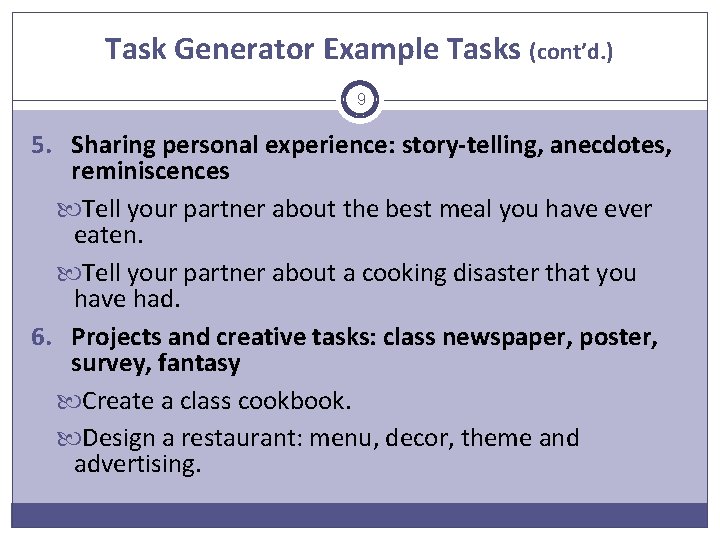

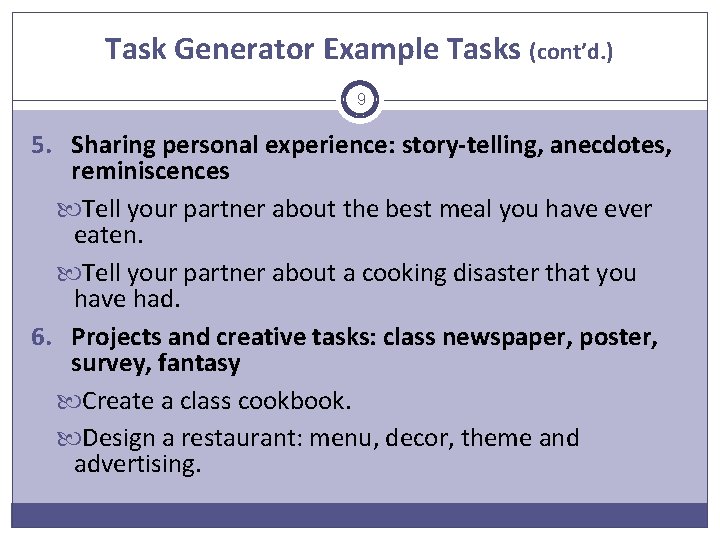

Task Generator Example Tasks (cont’d. ) 9 5. Sharing personal experience: story-telling, anecdotes, reminiscences Tell your partner about the best meal you have ever eaten. Tell your partner about a cooking disaster that you have had. 6. Projects and creative tasks: class newspaper, poster, survey, fantasy Create a class cookbook. Design a restaurant: menu, decor, theme and advertising.

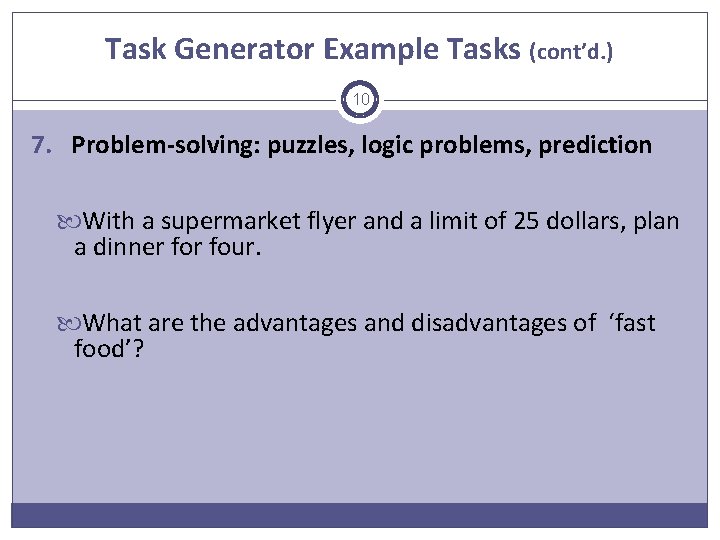

Task Generator Example Tasks (cont’d. ) 10 7. Problem-solving: puzzles, logic problems, prediction With a supermarket flyer and a limit of 25 dollars, plan a dinner four. What are the advantages and disadvantages of ‘fast food’?

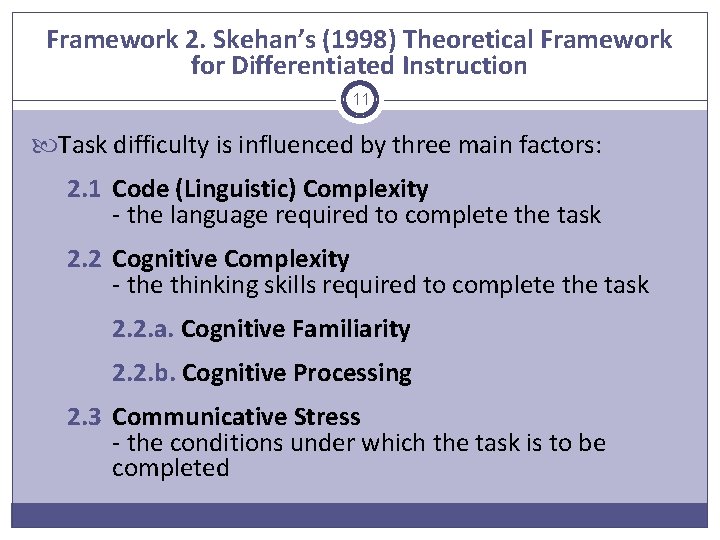

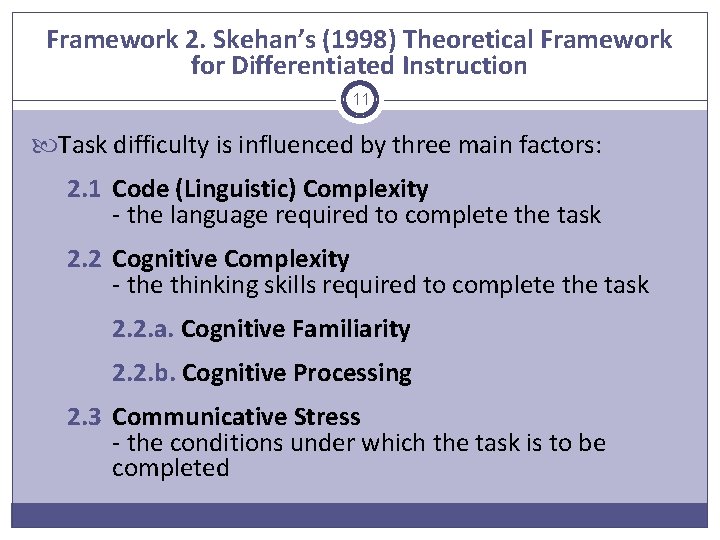

Framework 2. Skehan’s (1998) Theoretical Framework for Differentiated Instruction 11 Task difficulty is influenced by three main factors: 2. 1 Code (Linguistic) Complexity - the language required to complete the task 2. 2 Cognitive Complexity - the thinking skills required to complete the task 2. 2. a. Cognitive Familiarity 2. 2. b. Cognitive Processing 2. 3 Communicative Stress - the conditions under which the task is to be completed

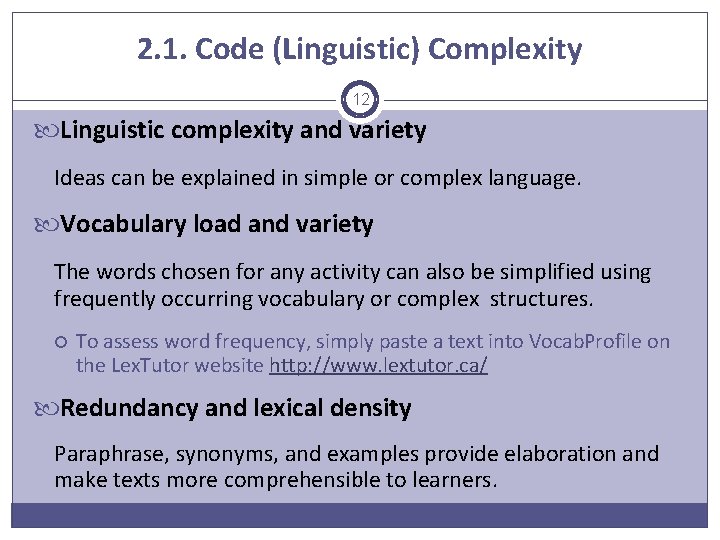

2. 1. Code (Linguistic) Complexity 12 Linguistic complexity and variety Ideas can be explained in simple or complex language. Vocabulary load and variety The words chosen for any activity can also be simplified using frequently occurring vocabulary or complex structures. To assess word frequency, simply paste a text into Vocab. Profile on the Lex. Tutor website http: //www. lextutor. ca/ Redundancy and lexical density Paraphrase, synonyms, and examples provide elaboration and make texts more comprehensible to learners.

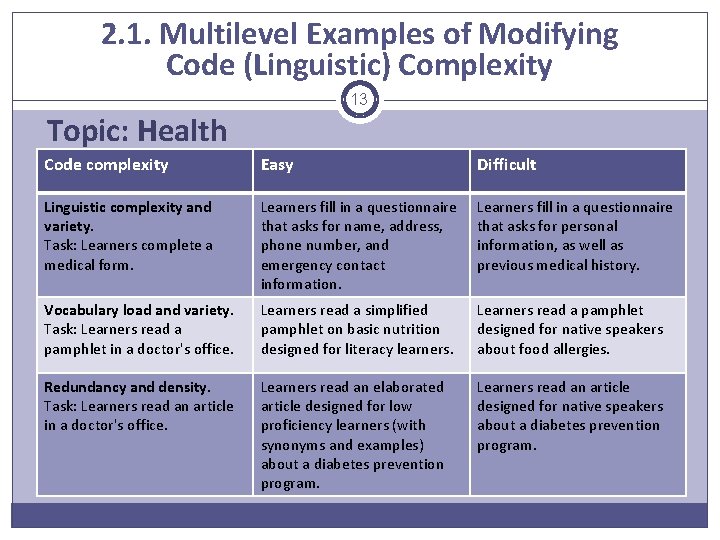

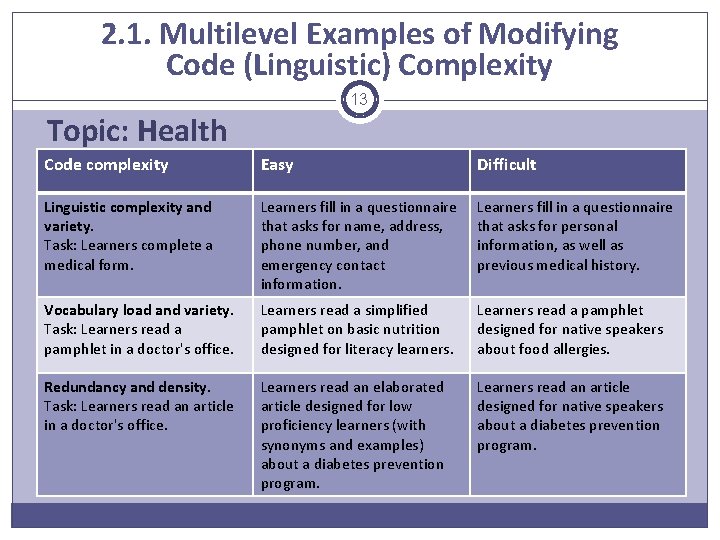

2. 1. Multilevel Examples of Modifying Code (Linguistic) Complexity 13 Topic: Health Code complexity Easy Difficult Linguistic complexity and variety. Task: Learners complete a medical form. Learners fill in a questionnaire that asks for name, address, phone number, and emergency contact information. Learners fill in a questionnaire that asks for personal information, as well as previous medical history. Vocabulary load and variety. Task: Learners read a pamphlet in a doctor's office. Learners read a simplified pamphlet on basic nutrition designed for literacy learners. Learners read a pamphlet designed for native speakers about food allergies. Redundancy and density. Task: Learners read an article in a doctor's office. Learners read an elaborated article designed for low proficiency learners (with synonyms and examples) about a diabetes prevention program. Learners read an article designed for native speakers about a diabetes prevention program.

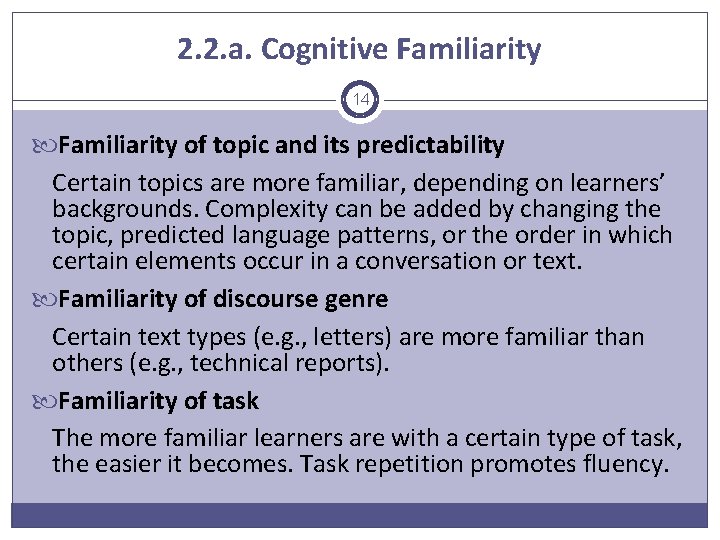

2. 2. a. Cognitive Familiarity 14 Familiarity of topic and its predictability Certain topics are more familiar, depending on learners’ backgrounds. Complexity can be added by changing the topic, predicted language patterns, or the order in which certain elements occur in a conversation or text. Familiarity of discourse genre Certain text types (e. g. , letters) are more familiar than others (e. g. , technical reports). Familiarity of task The more familiar learners are with a certain type of task, the easier it becomes. Task repetition promotes fluency.

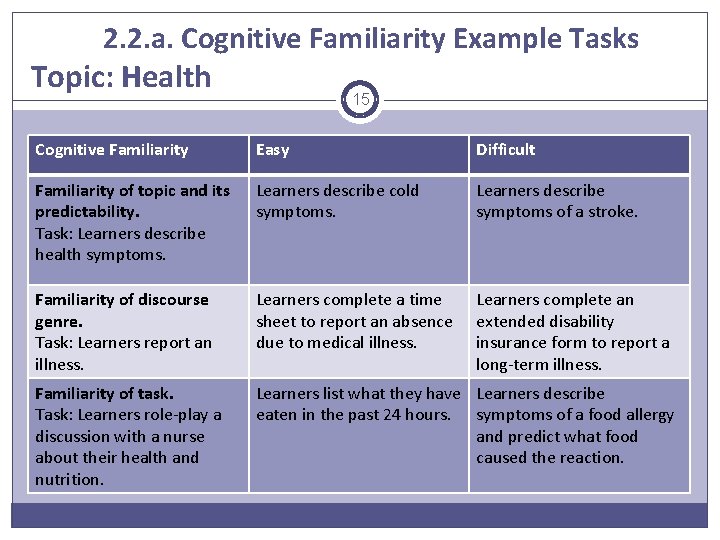

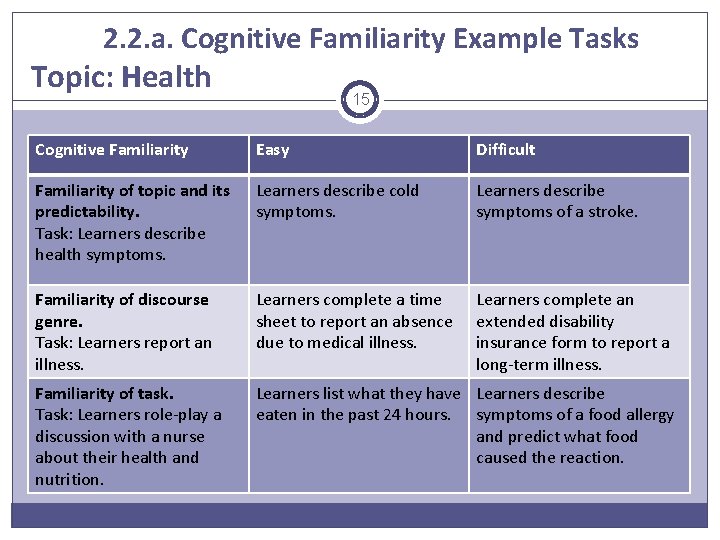

2. 2. a. Cognitive Familiarity Example Tasks Topic: Health 15 Cognitive Familiarity Easy Difficult Familiarity of topic and its predictability. Task: Learners describe health symptoms. Learners describe cold symptoms. Learners describe symptoms of a stroke. Familiarity of discourse genre. Task: Learners report an illness. Learners complete a time sheet to report an absence due to medical illness. Learners complete an extended disability insurance form to report a long-term illness. Familiarity of task. Task: Learners role-play a discussion with a nurse about their health and nutrition. Learners list what they have Learners describe eaten in the past 24 hours. symptoms of a food allergy and predict what food caused the reaction.

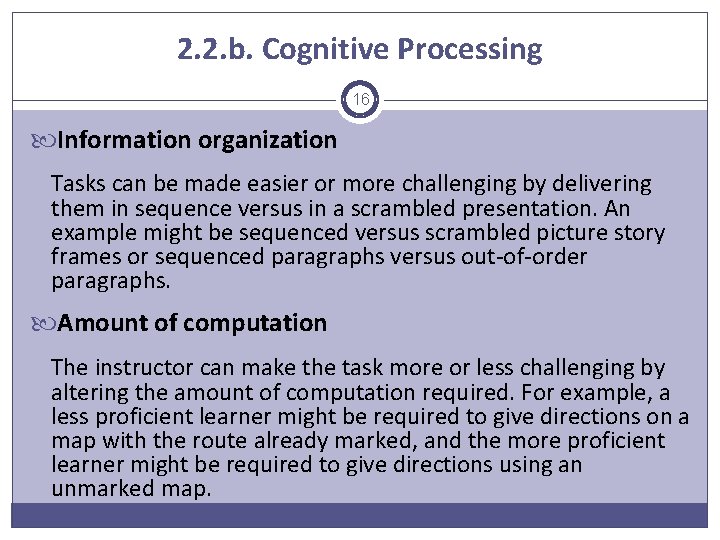

2. 2. b. Cognitive Processing 16 Information organization Tasks can be made easier or more challenging by delivering them in sequence versus in a scrambled presentation. An example might be sequenced versus scrambled picture story frames or sequenced paragraphs versus out-of-order paragraphs. Amount of computation The instructor can make the task more or less challenging by altering the amount of computation required. For example, a less proficient learner might be required to give directions on a map with the route already marked, and the more proficient learner might be required to give directions using an unmarked map.

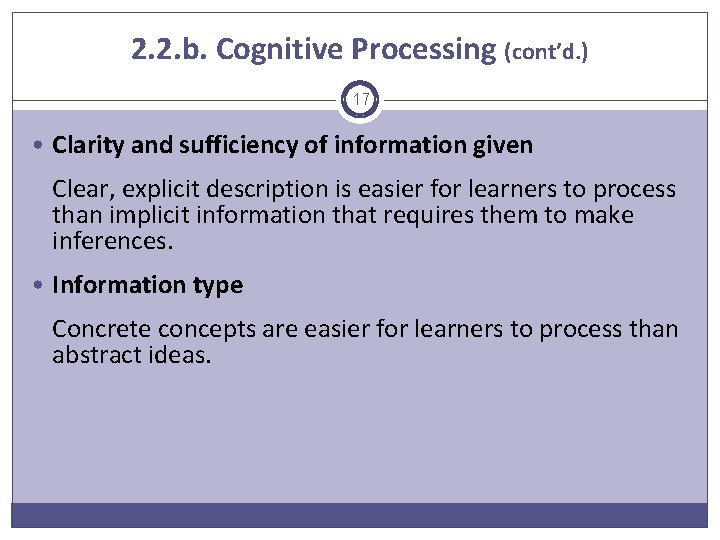

2. 2. b. Cognitive Processing (cont’d. ) 17 • Clarity and sufficiency of information given Clear, explicit description is easier for learners to process than implicit information that requires them to make inferences. • Information type Concrete concepts are easier for learners to process than abstract ideas.

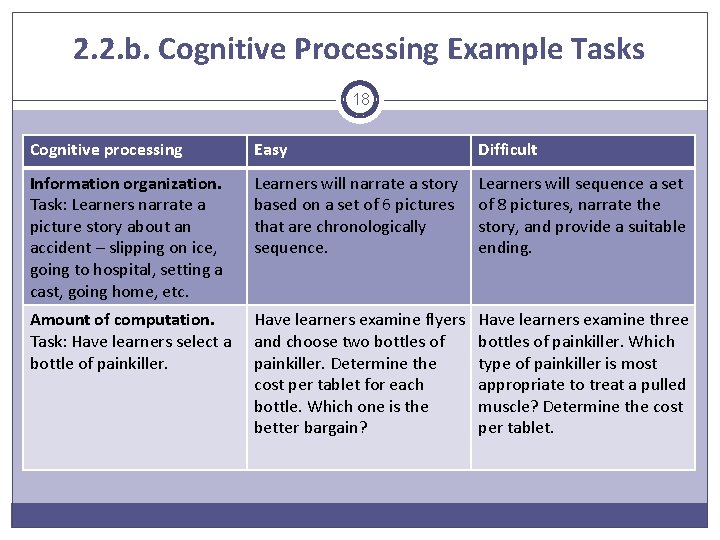

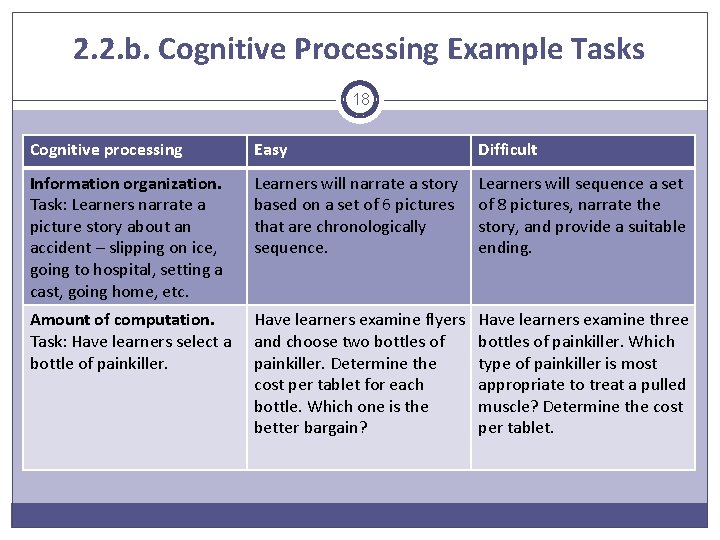

2. 2. b. Cognitive Processing Example Tasks 18 Cognitive processing Easy Difficult Information organization. Task: Learners narrate a picture story about an accident – slipping on ice, going to hospital, setting a cast, going home, etc. Learners will narrate a story based on a set of 6 pictures that are chronologically sequence. Learners will sequence a set of 8 pictures, narrate the story, and provide a suitable ending. Amount of computation. Task: Have learners select a bottle of painkiller. Have learners examine flyers and choose two bottles of painkiller. Determine the cost per tablet for each bottle. Which one is the better bargain? Have learners examine three bottles of painkiller. Which type of painkiller is most appropriate to treat a pulled muscle? Determine the cost per tablet.

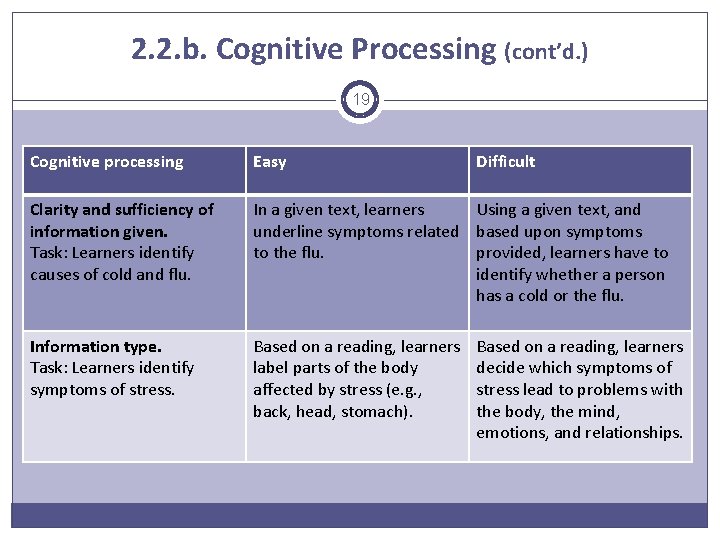

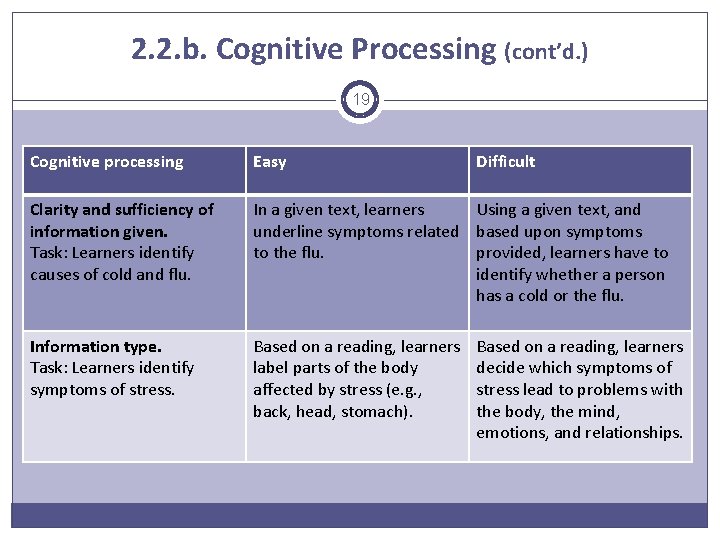

2. 2. b. Cognitive Processing (cont’d. ) 19 Cognitive processing Easy Difficult Clarity and sufficiency of information given. Task: Learners identify causes of cold and flu. In a given text, learners Using a given text, and underline symptoms related based upon symptoms to the flu. provided, learners have to identify whether a person has a cold or the flu. Information type. Task: Learners identify symptoms of stress. Based on a reading, learners label parts of the body affected by stress (e. g. , back, head, stomach). Based on a reading, learners decide which symptoms of stress lead to problems with the body, the mind, emotions, and relationships.

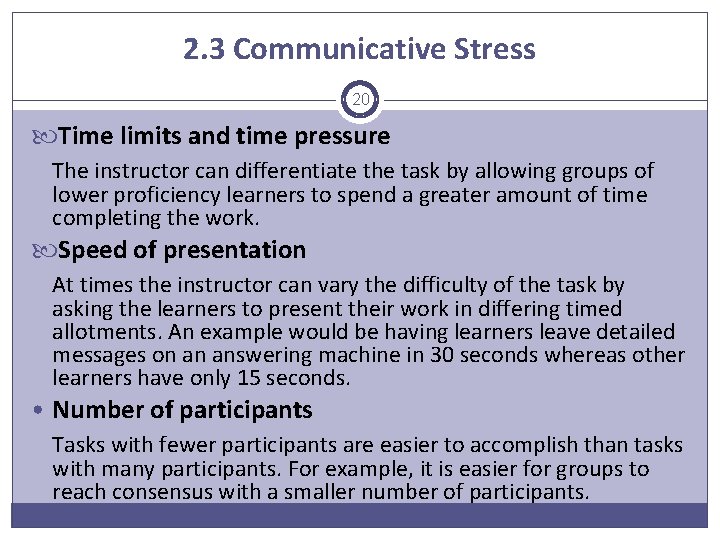

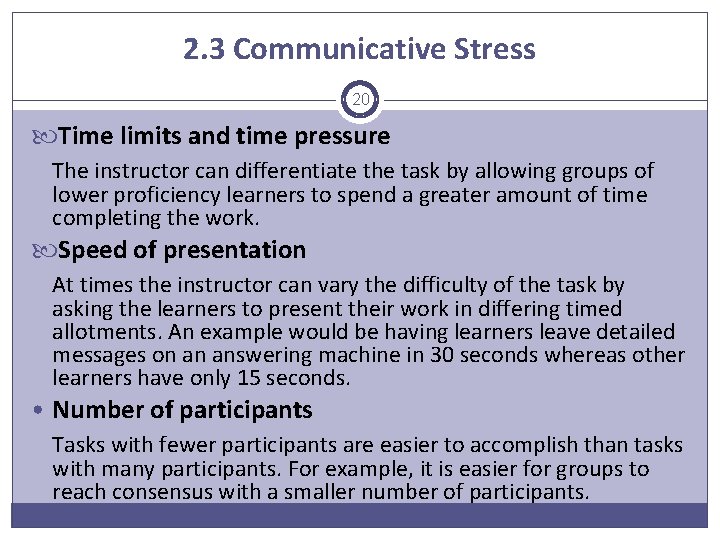

2. 3 Communicative Stress 20 Time limits and time pressure The instructor can differentiate the task by allowing groups of lower proficiency learners to spend a greater amount of time completing the work. Speed of presentation At times the instructor can vary the difficulty of the task by asking the learners to present their work in differing timed allotments. An example would be having learners leave detailed messages on an answering machine in 30 seconds whereas other learners have only 15 seconds. • Number of participants Tasks with fewer participants are easier to accomplish than tasks with many participants. For example, it is easier for groups to reach consensus with a smaller number of participants.

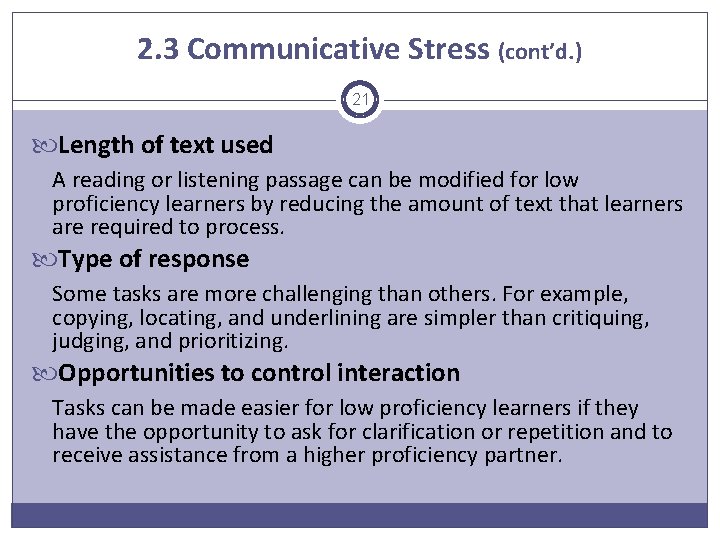

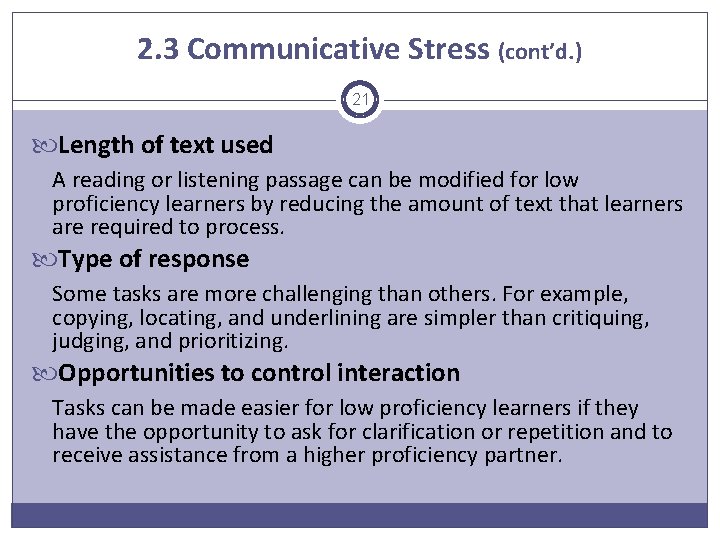

2. 3 Communicative Stress (cont’d. ) 21 Length of text used A reading or listening passage can be modified for low proficiency learners by reducing the amount of text that learners are required to process. Type of response Some tasks are more challenging than others. For example, copying, locating, and underlining are simpler than critiquing, judging, and prioritizing. Opportunities to control interaction Tasks can be made easier for low proficiency learners if they have the opportunity to ask for clarification or repetition and to receive assistance from a higher proficiency partner.

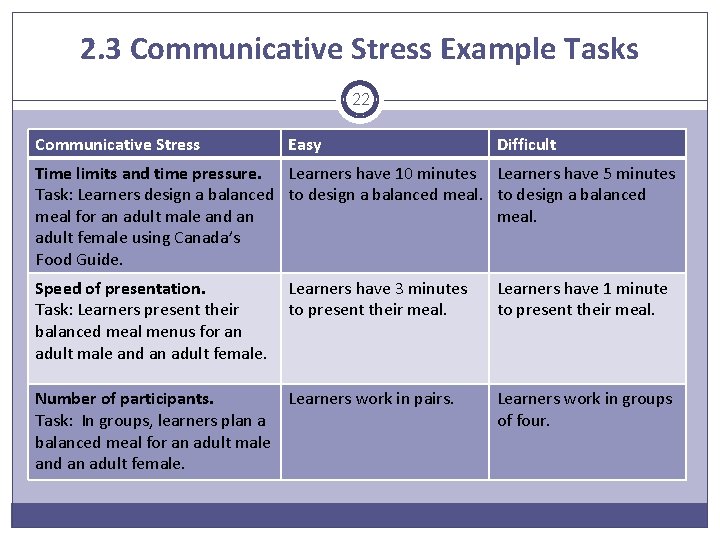

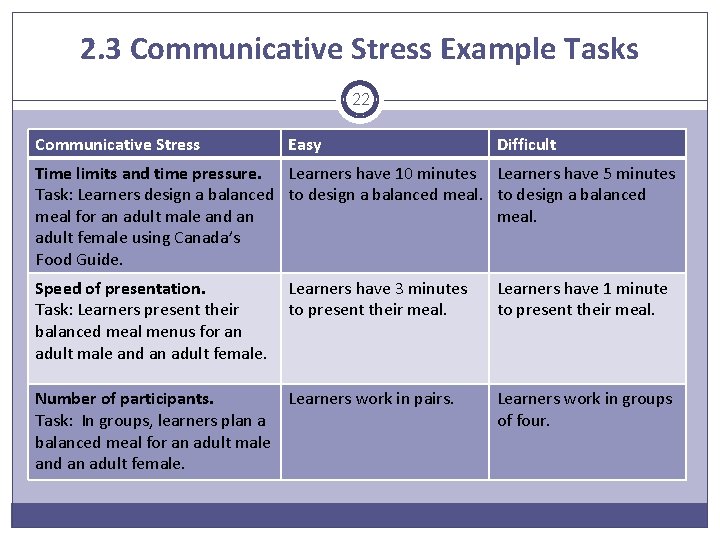

2. 3 Communicative Stress Example Tasks 22 Communicative Stress Easy Difficult Time limits and time pressure. Learners have 10 minutes Learners have 5 minutes Task: Learners design a balanced to design a balanced meal for an adult male and an meal. adult female using Canada’s Food Guide. Speed of presentation. Task: Learners present their balanced meal menus for an adult male and an adult female. Learners have 3 minutes to present their meal. Number of participants. Learners work in pairs. Task: In groups, learners plan a balanced meal for an adult male and an adult female. Learners have 1 minute to present their meal. Learners work in groups of four.

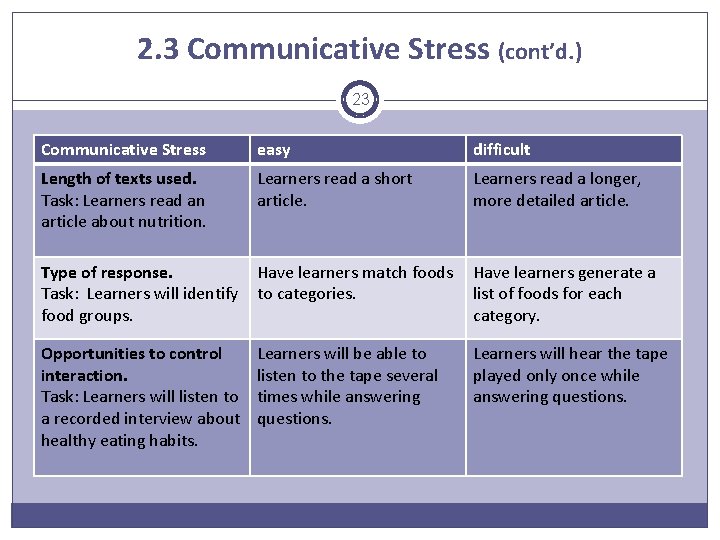

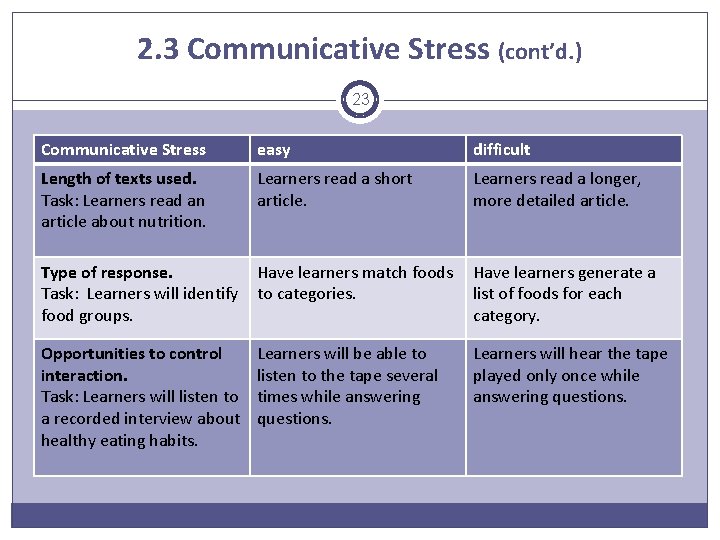

2. 3 Communicative Stress (cont’d. ) 23 Communicative Stress easy difficult Length of texts used. Task: Learners read an article about nutrition. Learners read a short article. Learners read a longer, more detailed article. Type of response. Task: Learners will identify food groups. Have learners match foods to categories. Have learners generate a list of foods for each category. Opportunities to control interaction. Task: Learners will listen to a recorded interview about healthy eating habits. Learners will be able to listen to the tape several times while answering questions. Learners will hear the tape played only once while answering questions.

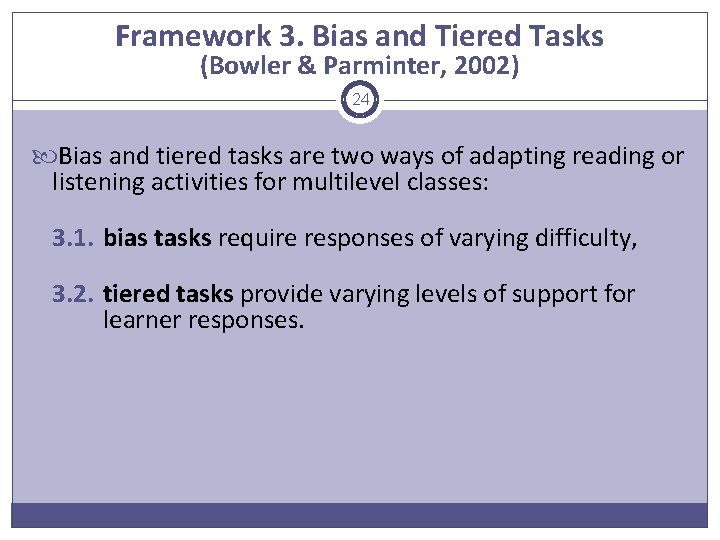

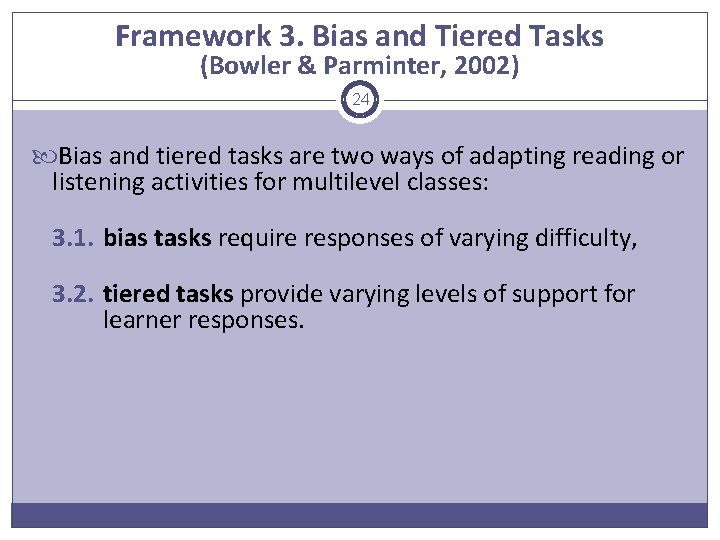

Framework 3. Bias and Tiered Tasks (Bowler & Parminter, 2002) 24 Bias and tiered tasks are two ways of adapting reading or listening activities for multilevel classes: 3. 1. bias tasks require responses of varying difficulty, 3. 2. tiered tasks provide varying levels of support for learner responses.

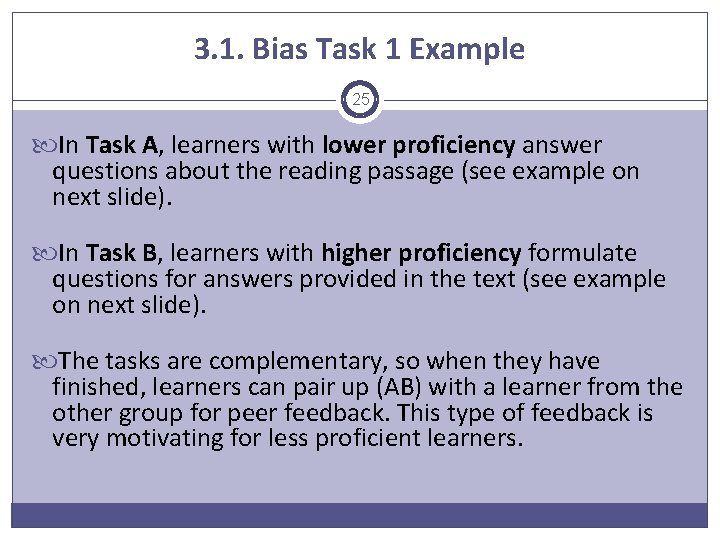

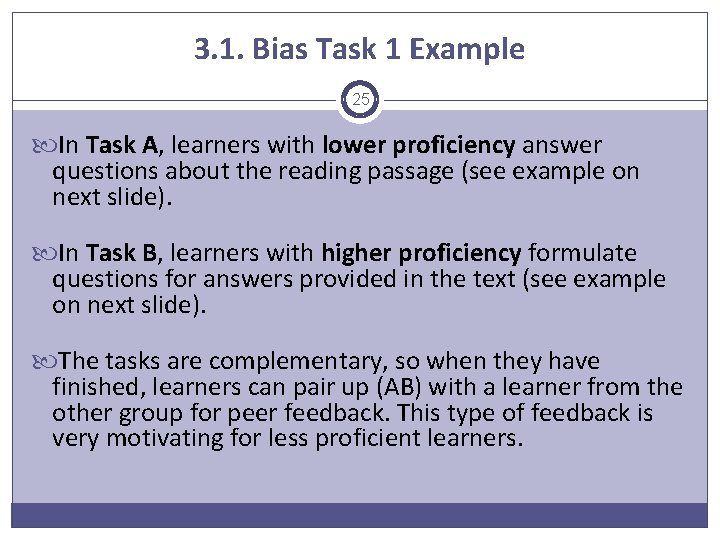

3. 1. Bias Task 1 Example 25 In Task A, learners with lower proficiency answer questions about the reading passage (see example on next slide). In Task B, learners with higher proficiency formulate questions for answers provided in the text (see example on next slide). The tasks are complementary, so when they have finished, learners can pair up (AB) with a learner from the other group for peer feedback. This type of feedback is very motivating for less proficient learners.

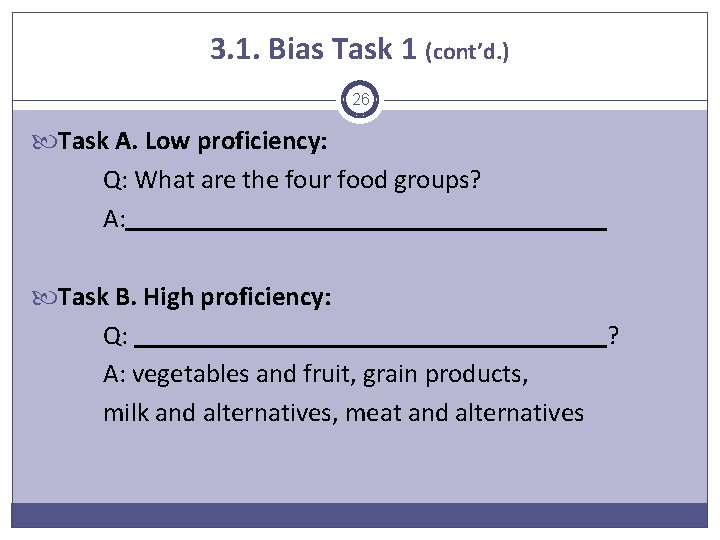

3. 1. Bias Task 1 (cont’d. ) 26 Task A. Low proficiency: Q: What are the four food groups? A: Task B. High proficiency: Q: ? A: vegetables and fruit, grain products, milk and alternatives, meat and alternatives

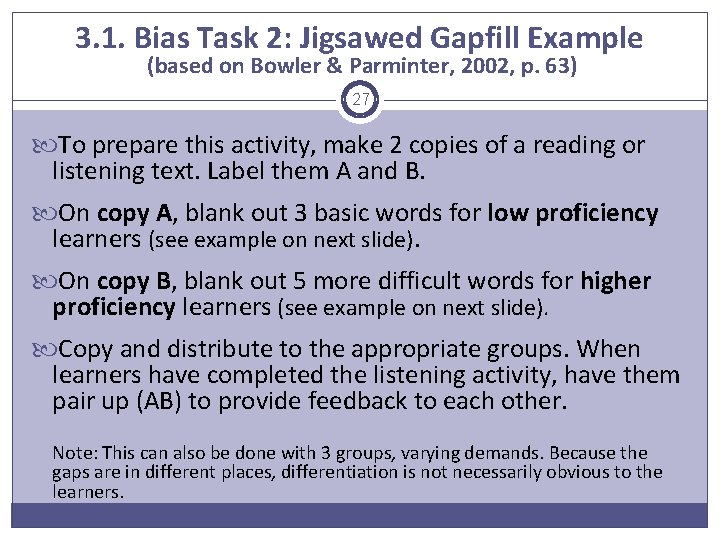

3. 1. Bias Task 2: Jigsawed Gapfill Example (based on Bowler & Parminter, 2002, p. 63) 27 To prepare this activity, make 2 copies of a reading or listening text. Label them A and B. On copy A, blank out 3 basic words for low proficiency learners (see example on next slide). On copy B, blank out 5 more difficult words for higher proficiency learners (see example on next slide). Copy and distribute to the appropriate groups. When learners have completed the listening activity, have them pair up (AB) to provide feedback to each other. Note: This can also be done with 3 groups, varying demands. Because the gaps are in different places, differentiation is not necessarily obvious to the learners.

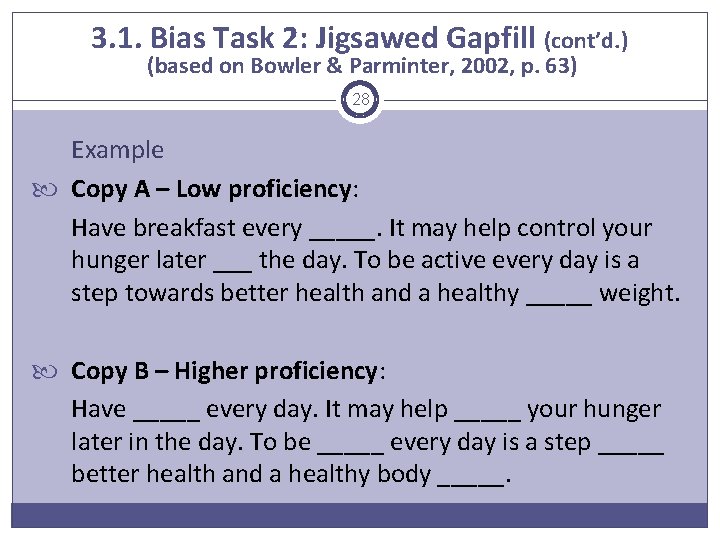

3. 1. Bias Task 2: Jigsawed Gapfill (cont’d. ) (based on Bowler & Parminter, 2002, p. 63) 28 Example Copy A – Low proficiency: Have breakfast every _____. It may help control your hunger later ___ the day. To be active every day is a step towards better health and a healthy _____ weight. Copy B – Higher proficiency: Have _____ every day. It may help _____ your hunger later in the day. To be _____ every day is a step _____ better health and a healthy body _____.

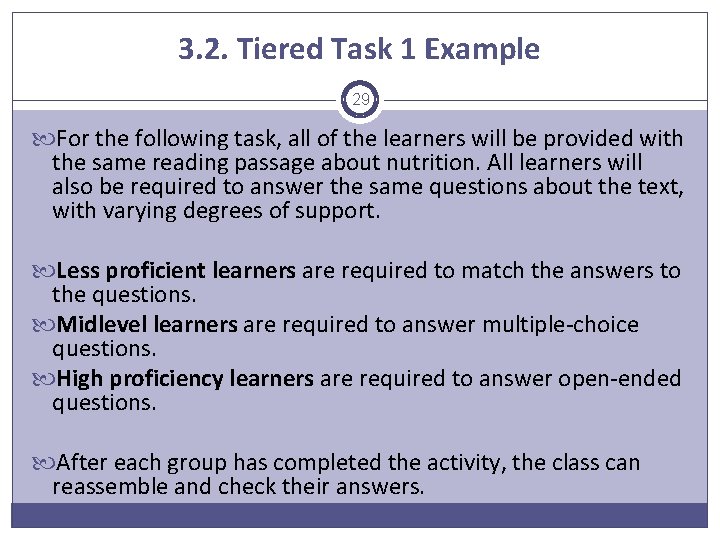

3. 2. Tiered Task 1 Example 29 For the following task, all of the learners will be provided with the same reading passage about nutrition. All learners will also be required to answer the same questions about the text, with varying degrees of support. Less proficient learners are required to match the answers to the questions. Midlevel learners are required to answer multiple-choice questions. High proficiency learners are required to answer open-ended questions. After each group has completed the activity, the class can reassemble and check their answers.

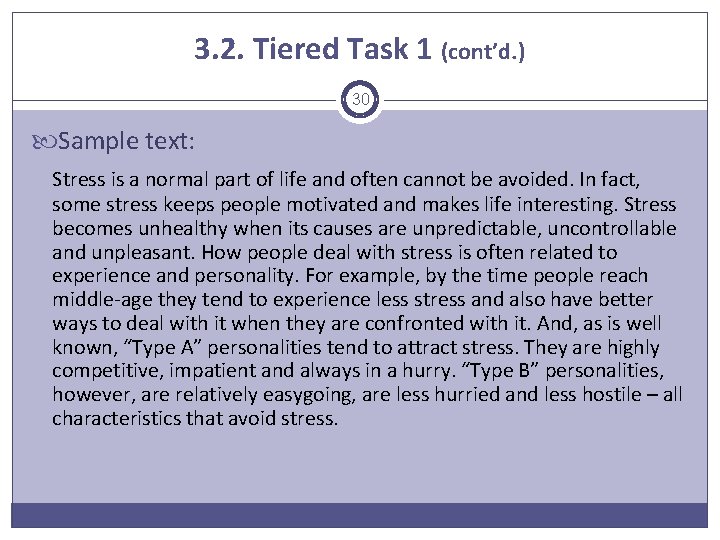

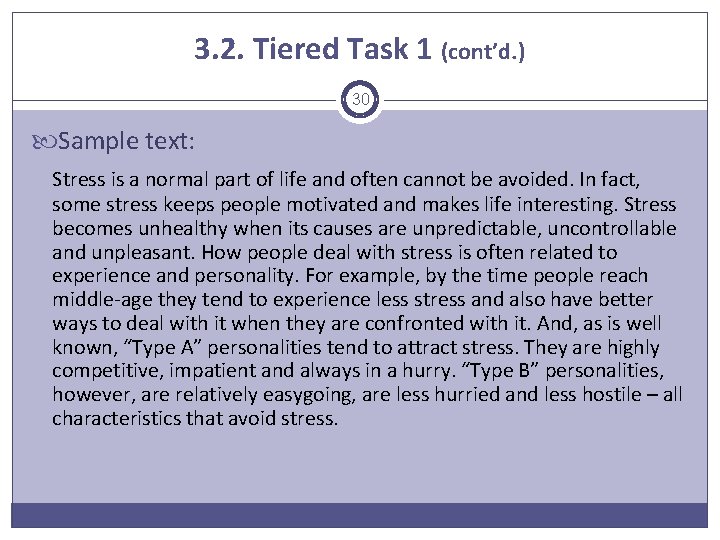

3. 2. Tiered Task 1 (cont’d. ) 30 Sample text: Stress is a normal part of life and often cannot be avoided. In fact, some stress keeps people motivated and makes life interesting. Stress becomes unhealthy when its causes are unpredictable, uncontrollable and unpleasant. How people deal with stress is often related to experience and personality. For example, by the time people reach middle-age they tend to experience less stress and also have better ways to deal with it when they are confronted with it. And, as is well known, “Type A” personalities tend to attract stress. They are highly competitive, impatient and always in a hurry. “Type B” personalities, however, are relatively easygoing, are less hurried and less hostile – all characteristics that avoid stress.

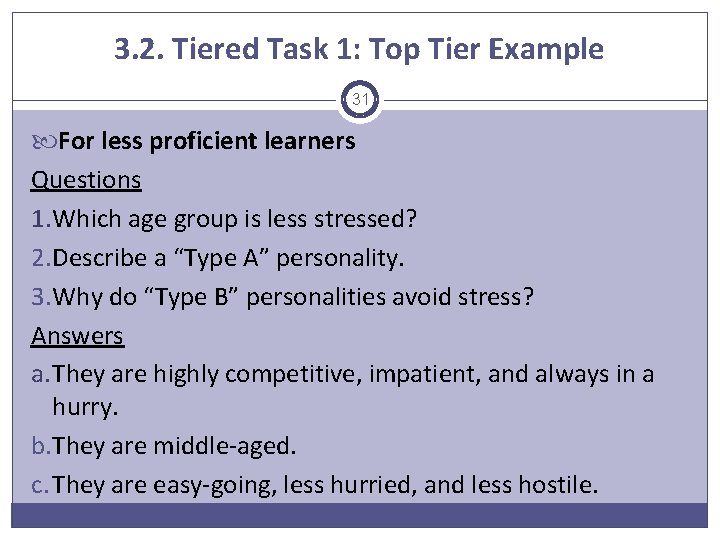

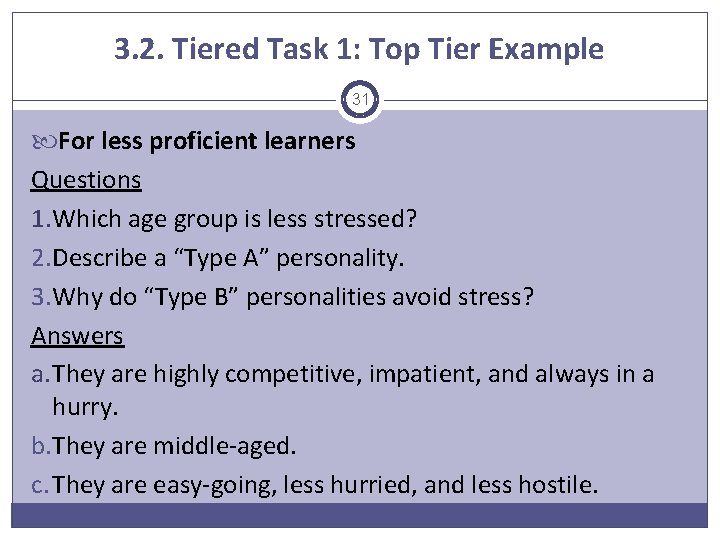

3. 2. Tiered Task 1: Top Tier Example 31 For less proficient learners Questions 1. Which age group is less stressed? 2. Describe a “Type A” personality. 3. Why do “Type B” personalities avoid stress? Answers a. They are highly competitive, impatient, and always in a hurry. b. They are middle-aged. c. They are easy-going, less hurried, and less hostile.

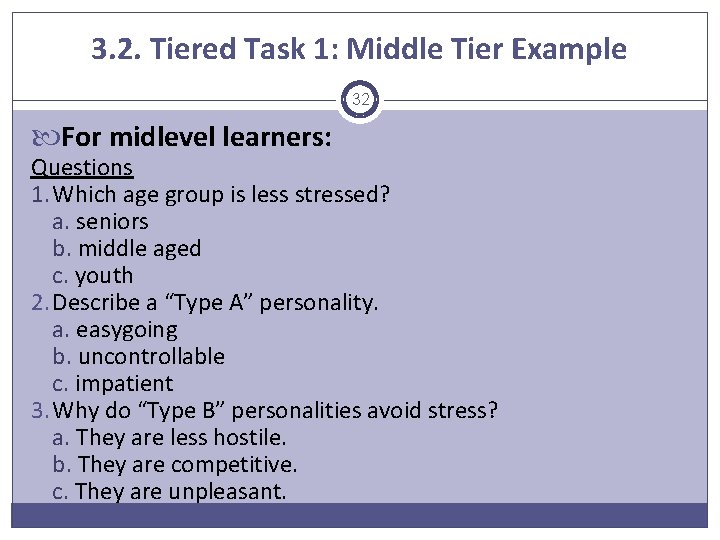

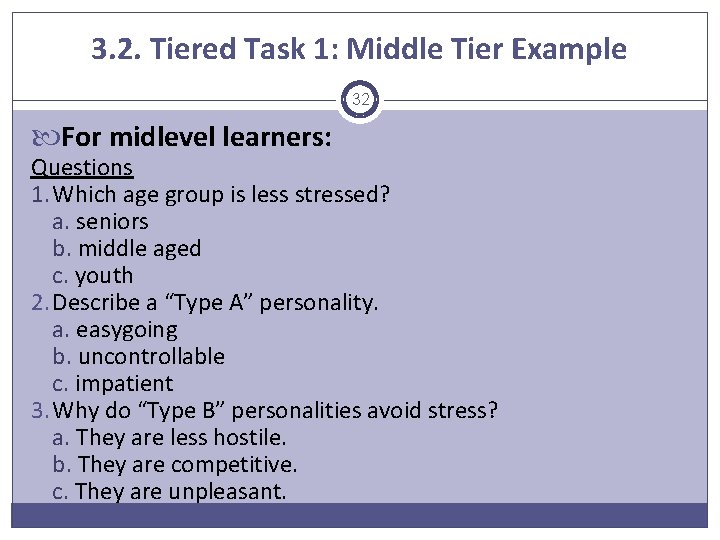

3. 2. Tiered Task 1: Middle Tier Example 32 For midlevel learners: Questions 1. Which age group is less stressed? a. seniors b. middle aged c. youth 2. Describe a “Type A” personality. a. easygoing b. uncontrollable c. impatient 3. Why do “Type B” personalities avoid stress? a. They are less hostile. b. They are competitive. c. They are unpleasant.

3. 2. Tiered Task 1: Bottom Tier Example 33 For high proficiency learners: 1. Which age group is less stressed? 2. Describe a “Type A” personality. 3. Why do “Type B” personalities avoid stress?

3. 2. Tiered Task 2: Dual Choice Gapfill Example 34 For this task, learners are assigned to two groups. The more proficient learners are given a reading or listening passage in which they are required to fill in a number of blanks. The less proficient learners are given the same passage and are required to choose between two possible answers for each gap. Like the previous tiered task, all learners are working on the same activity; therefore, it is possible for the answers to be corrected as a class. The song The Newcomers Song by Maria Dunn was chosen for this activity: http: //www. youtube. com/watch? v=LGs 5 fo 9 -DOk

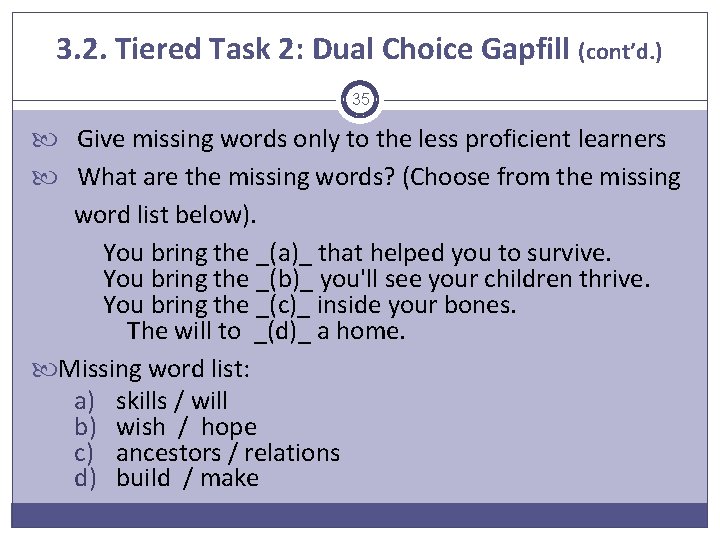

3. 2. Tiered Task 2: Dual Choice Gapfill (cont’d. ) 35 Give missing words only to the less proficient learners What are the missing words? (Choose from the missing word list below). You bring the _(a)_ that helped you to survive. You bring the _(b)_ you'll see your children thrive. You bring the _(c)_ inside your bones. The will to _(d)_ a home. Missing word list: a) skills / will b) wish / hope c) ancestors / relations d) build / make

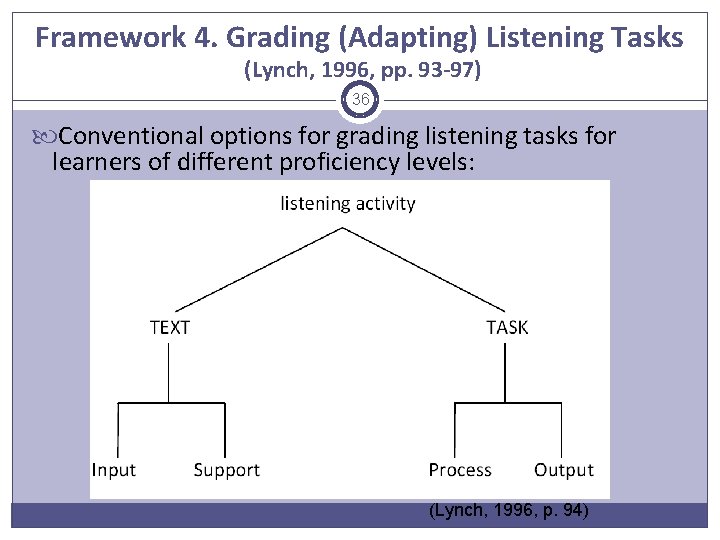

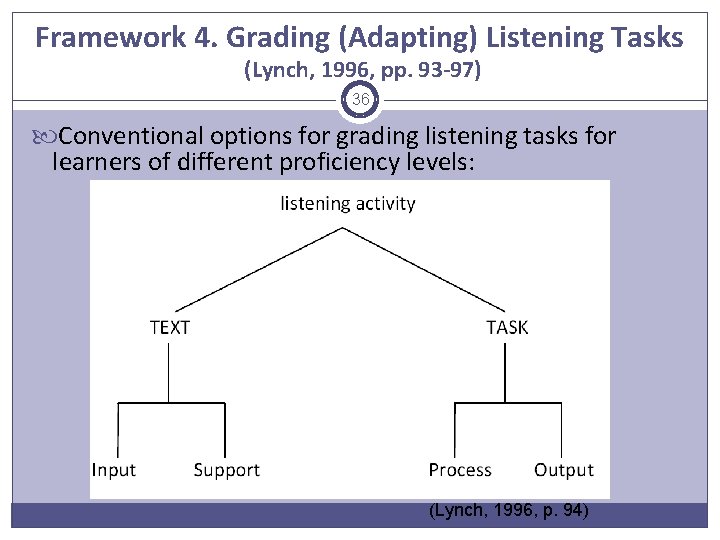

Framework 4. Grading (Adapting) Listening Tasks (Lynch, 1996, pp. 93 -97) 36 Conventional options for grading listening tasks for learners of different proficiency levels: (Lynch, 1996, p. 94)

4. Adapting Listening Texts 37 Input pre-modified (e. g. , restrict the number of unfamiliar items) post-modified (e. g. , select easier listening extracts for learners) Support Provide any form of materials (e. g. , an outline, a list of vocabulary) to assist the learners in understanding the text prior to hearing the passage.

4. Adapting Listening Tasks 38 Process This relates to the listening purpose (e. g. , listening for the main idea versus listening for specific details). Output This relates to increasing or reducing the response demands from learners (e. g. , a non-verbal response, such as a completing a checklist versus a verbal response). Slides 39 -43 give some examples about how the same text and task can be graded to allow learners of different linguistic abilities to use them.

4. Adapting Listening Tasks: Sample Passage 39 Sample listening passage Transcript: “Hi! I'm Tony Clement, Canada's Minister of Health, and today I'd like to share with you some "Food for Thought, " information available to everyone on Health Canada's web site. We're very fortunate in Canada to have not only a very productive agricultural sector, but also a wide variety of foods imported from around the world. When you set out to "eat healthy, " be sure to try Italian, Chinese, Middle Eastern or any of the other great ethnic foods Canada has to offer. Pay attention to portion sizes - by reading the new nutrition labels now required on food products you will see how many portions the package contains, and many people are surprised to discover they are actually eating two or more portions when they thought they were eating only one! Remember: Healthy eating and great taste go hand in hand; There are no "good" or "bad" foods - moderation is the key; And everything tastes better when you enjoy it with family and friends! I'm Tony Clement. You, stay healthy. ”

Grading the Text: Input (Lynch, 1996, p. 96) 40 Possible modifications (from least to most difficult): record a modified version replacing less familiar expressions with simpler ones, or taking out names and references that the learners may not know; reduce use the length of the listening passage; and the original text, but pause frequently to check for comprehension.

Grading the Text: Support (Lynch, 1996, p. 96) 41 Possible modifications: provide key visuals to help learners follow the conversation (e. g. , an outline, a map, etc. ); give learners a list of key vocabulary to be found in the passage, to aid comprehension; and give learners a full transcript with some of the words blanked out.

Grading the Task: Process (Lynch, 1996, p. 96) 42 Possible modifications (from least to most difficult): have learners listen for very general understanding (e. g. , It’s about healthy eating); have learners identify as many of the forms of ethnic food mentioned as possible; and require the learners to make decisions based on information in the text while listening (e. g. , Are you a healthy eater? Explain).

Grading the Task: Output (Lynch, 1996, p. 96) 43 Provide a range of response types: Completing checklists (e. g. , Which of the following foods are mentioned? ) Ordering (e. g. , In which order are these ideas mentioned? ) Matching (e. g. , foods to pictures, words to definitions) Filling-in-the-blanks Answering comprehension questions in the first language versus answering in English

Grouping Learners 44 Valuable grouping strategies include: a) whole group, b) small group, c) pair work, and d) individual work. Whole group activities are often used at the beginning and at the end of a lesson.

Grouping Learners (cont’d. ) 45 When carefully designed, small groups and pair work may create: a) greater opportunities for interaction and feedback (e. g. , learners can practise speaking to a variety of people and learn how to adjust their speech according to their audience). b) less intimidating environments (e. g. , shy, less confident learners may feel more comfortable speaking). c) more effective use of resources (i. e. , where resources are limited, they can be shared) Working individually allows learners to meet specific needs and interests, to build autonomy, and to develop strengths. It also accommodates learners who prefer to work alone.

Other Grouping Strategies 46 Other grouping strategies include: mixed-ability, same-language, and shared-interest groups. These strategies can be used to meet specific learning needs and objectives.

Mixed Ability Groups 47 Mixed-ability groups can complete the same activity, but at different levels. This allows all learners to start with the same listening or reading text and to complete activities that are modified to accommodate the varying proficiency levels of the learners (see examples on previous slides) Mixed-ability groups can also complete class projects in which every learner is responsible for part of the project (e. g. , creating a class newspaper or photo-story [see Bell, pp. 120121]).

Same-Ability Groups 48 Same-ability groups allow learners to focus on grammar, vocabulary, or other language skills that are particular to their proficiency level.

Same-Language/Interest Groups 49 Same-language groups allow learners to focus on English language difficulties that are related to their first language (e. g. , pronunciation or grammatical difficulties) Same-language groups may also use their first language to share understandings (e. g. , cultural, pragmatic, conceptual knowledge). Groups can also be created based on learner interests, expertise, and personal characteristics, such as age, marital status, learning style, recreation, hobbies, likes and dislikes, etc.

Guidelines for Multilevel Lesson Planning 50 1. Select learning objectives - see http: //www. language. ca/display_page. asp? page_id=206 2. Design the learning task - see previous slides 3. Activate prior knowledge (e. g. , brainstorming, reading captions/headings, viewing pictures, relating topic to learners' background) 4. Organize groups/tasks - see previous slides 5. Assign roles to learners (e. g. , timekeeper, recorder, presenter, moderator) 6. Provide task extensions (e. g. , if one group finishes early) - see previous slides 7. Evaluate learning – see Holmes (2005), Integrating CLB Assessment into your ESL classroom

Example Lesson 51 CLB health lesson – Medical Clinics (click link below) http: //www. language. ca/display_page. asp? page_id=318 How to adapt the lesson for a multi-level class: 1. Warm-up: see CCLB Medical Clinics lesson plan 2. Listening task (modifying length of text, Slide 21) Less proficient learners: see CCLB Medical Clinics lesson plan Midlevel learners: give these learners 15 names to match with office numbers High proficiency learners: give these learners all 20 names to match with office numbers

Lesson plan (cont’d. ) 52 2. Speaking task (modifying time pressure, Slide 20) Less proficient learners: have these learners complete the task for their list of 10 doctors Midlevel learners: have these learners complete the task using their list of 15 doctors in the same amount of time High proficiency learners: have these learners complete the task using their list of 20 doctors in the same amount of time

Lesson plan (cont’d. ) 53 2. Reading task (modifying amount of computation, Slide 16) Less proficient learners: use class charted directory, as described in the lesson Midlevel learners: use a directory (e. g. , the Yellow Pages) to locate general practitioners in your area High proficiency learners: use the Physician Search website below to locate general practitioners who are accepting new patients close to your home http: //www. cpsa. ab. ca/Physician. Search/Search. Results. aspx? City=Edmonton&Only. Show. Accepting=1&Specialists=0 3. Final task – see CCLB Medical Clinics lesson plan

Conclusion 54 Developing familiarity with a few good options for adapting tasks will make lesson planning more efficient and ESL instruction more effective.

References 55 Bell, J. S. (2004). Teaching multilevel classes in ESL (2 nd ed. ). Don Mills, ON: Pippin. Bowler, B. & Parminter, S. (2002). Mixed-level teaching: Tiered tasks and bias tasks. In J. C. Richards & W. A. Renandya (Eds. ), Methodology in language teaching: An anthology of current practice (pp. 59 -68). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Centre for Canadian Language Benchmarks. (2000). Canadian Language Benchmarks 2000: English as a second language for adults. Ottawa, ON: Author. Holmes, T. (2005). Integrating CLB Assessment into your ESL classroom. Ottawa, ON: Centre for Canadian Language Benchmarks.

References (cont’d. ) 56 Lynch, T. (1996). Communication in the language classroom. Oxford: Oxford University Press. Skehan, P. (1998). A cognitive approach to language learning. Oxford: Oxford University Press. Willis, D. , & Willis, J. (2007). Doing task-based teaching. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Additional References 57 Adelson-Goldstein, J. (2007). The step forward professional development program for multilevel instruction in adult ESL programs. New York: Oxford University Press. Brown, H. D. (2001). Teaching by principles: An interactive approach to language pedagogy (2 nd ed. ). Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall Regents. Center for Adult English Language Acquisition. (2006). Promoting success of multilevel ESL classes: What teachers and administrators can do. Retrieved October 24, 2008, from http: //www. cal. org/caela/esl_resources/briefs/multilevel. pdf Centre for Canadian Language Benchmarks. (2002). Canadian Language Benchmarks 2000: Additional sample task ideas. Ottawa, ON: Author. Retrieved October 24, 2008, from http: //www. language. ca/display_page. asp? page_id=259

Additional References (cont’d. ) 58 Colorado State University. (2008). Overview: ESL volunteer guide. Retrieved October 24, 2008, from http: //writing. colostate. edu/guides/teaching/esl/printformat. cfm? pri ntformat=yes Ellis, R. (2003). Task-based language learning and teaching. Oxford: Oxford University Press. Harmer, J. (2007). The practice of English language teaching (4 th ed. ). Harlow, UK: Pearson Longman. Hess, N. (2001). Teaching large multilevel classes. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Holmes, T. L. (2001). Canadian Language Benchmarks 2000: A guide to implementation. Ottawa, ON: Centre for Canadian Language Benchmarks.

Additional References (cont’d. ) 59 Lightbown, P. M. , & Spada, N. (2006). How languages are learned. Oxford: Oxford University Press. Mathews-Aydinli, J. , & Van Horne, R. (2006). Promoting success of multilevel ESL classes: What teachers and administrators can do. Washington, DC: Center for Applied Linguistics. Retrieved November 28, 2008, from http: //www. cal. org/caela/esl%5 Fresources/briefs/multilevel. html Roberts, M. (2007). Teaching in the multilevel classroom. Pearson Education. Retrieved March 25, 2008 from http: //www. pearsonlongman. com/ae/download/adulted/multilevel_monogr aph. pdf Willis, J. (1996). A framework for task-based learning. Harlow, UK: Longman.

Acknowledgements 60 Dr. Marilyn Abbott Dr. Marian Rossiter Carolyn Dieleman for funding from Alberta Employment and Immigration Gertrude Aberdeen for her research assistance Laura Monerris for her research assistance