PILOT Background PILOT Pulmonary Fibrosis Identification Lessons for

PILOT: Background • PILOT (Pulmonary Fibrosis Identification: Lessons for Optimizing • • • Treatment) is a national education initiative driven by The France Foundation, an ACCME-accredited provider Education focuses on the early and accurate diagnosis of IPF, while also addressing critical issues related to optimizing disease intervention and management Led by experts in the IPF field, PILOT has attained a level of recognition and credibility across practitioner and patient communities that places it as one of the primary sources for timely and innovative education on IPF In the 10+ years since its launch, PILOT has had over 13 million hits to its educational Web site, www. PILOTfor. IPF. org.

PILOT: Steering Committee

Pulmonary Fibrosis Foundation (PFF) A Collaborator in this Regional Activity The PFF was founded in 2000 by brothers Albert Rose and Michael Rosenzweig, Ph. D after the brothers experienced firsthand the devastating effects of PF when their sister Claire passed away from the disease. Both brothers were also diagnosed with PF, and it was their vision and dedication that led to the creation of the Foundation. The mission of the PFF is to serve as the trusted resource for the pulmonary fibrosis community by raising awareness, providing disease education, and funding research.

Learning Objectives: Non-Pharmacologic Management • Formulate an education and disease management plan with patients that • • accounts for therapeutic options, patient preferences, and treatment goals Identify opportunities for referral to specialized care as part of the multidisciplinary IPF management plan Describe common comorbidities of IPF and their management

Non-Pharmacologic Management Steven D. Nathan, MD Inova Health System Luca Richeldi, MD, Ph. D University of Southampton

Point of Discussion: Do you involve a tertiary ILD center in your management of patients with IPF? A. Yes B. No

Non-Pharmacologic Considerations • • Comorbidities Lung transplantation Oxygen therapy Pulmonary rehabilitation Patient communication Tertiary care center referral End–of–life issues

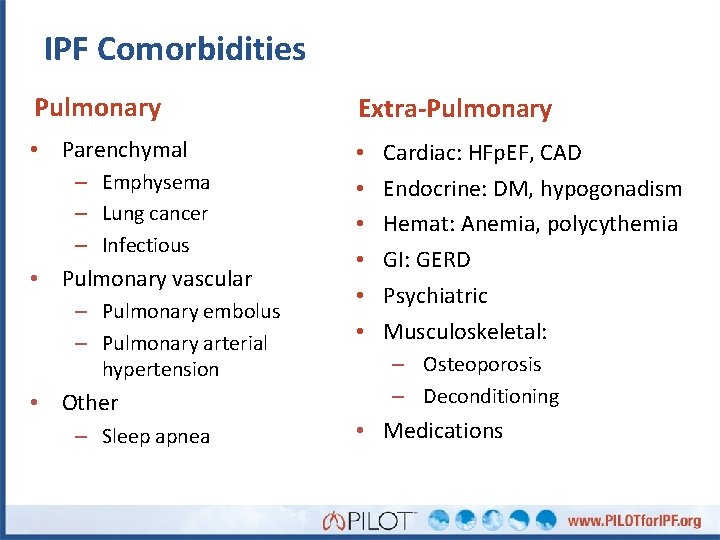

IPF Comorbidities Pulmonary Extra-Pulmonary • Parenchymal • • • – Emphysema – Lung cancer – Infectious • Pulmonary vascular – Pulmonary embolus – Pulmonary arterial hypertension • Other – Sleep apnea Cardiac: HFp. EF, CAD Endocrine: DM, hypogonadism Hemat: Anemia, polycythemia GI: GERD Psychiatric Musculoskeletal: – Osteoporosis – Deconditioning • Medications

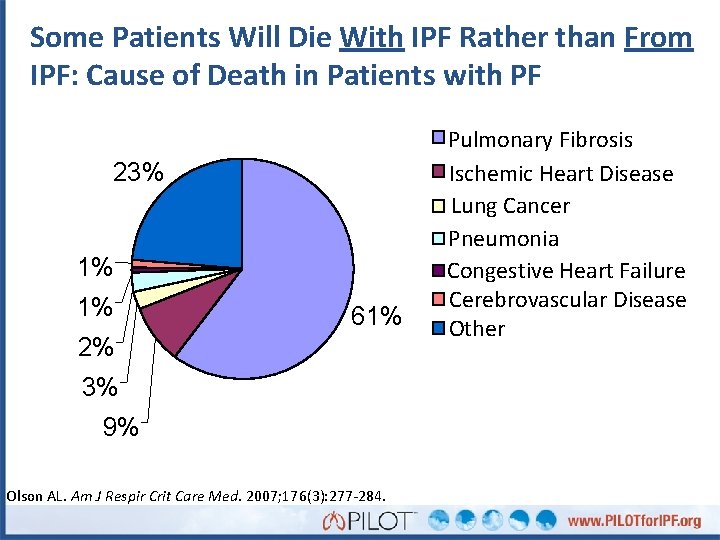

Some Patients Will Die With IPF Rather than From IPF: Cause of Death in Patients with PF 23% 1% 1% 61% 2% 3% 9% Olson AL. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2007; 176(3): 277 -284. Pulmonary Fibrosis Ischemic Heart Disease Lung Cancer Pneumonia Congestive Heart Failure Cerebrovascular Disease Other

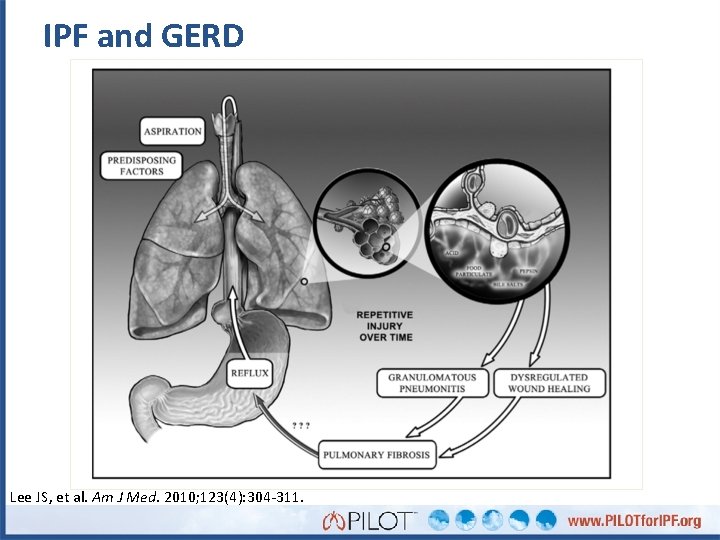

IPF and GERD Lee JS, et al. Am J Med. 2010; 123(4): 304 -311.

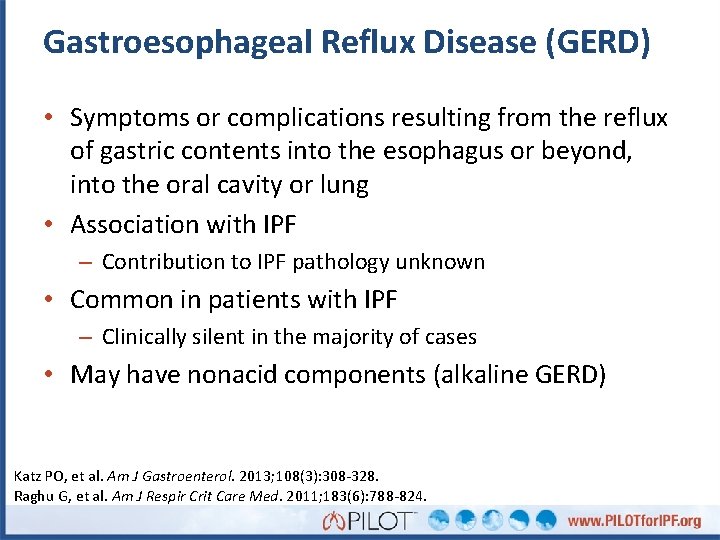

Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease (GERD) • Symptoms or complications resulting from the reflux of gastric contents into the esophagus or beyond, into the oral cavity or lung • Association with IPF – Contribution to IPF pathology unknown • Common in patients with IPF – Clinically silent in the majority of cases • May have nonacid components (alkaline GERD) Katz PO, et al. Am J Gastroenterol. 2013; 108(3): 308 -328. Raghu G, et al. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2011; 183(6): 788 -824.

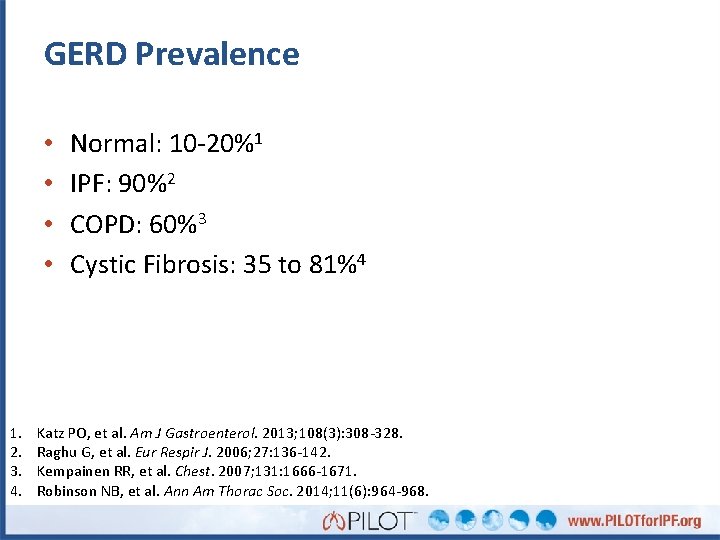

GERD Prevalence • • 1. 2. 3. 4. Normal: 10 -20%1 IPF: 90%2 COPD: 60%3 Cystic Fibrosis: 35 to 81%4 Katz PO, et al. Am J Gastroenterol. 2013; 108(3): 308 -328. Raghu G, et al. Eur Respir J. 2006; 27: 136 -142. Kempainen RR, et al. Chest. 2007; 131: 1666 -1671. Robinson NB, et al. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2014; 11(6): 964 -968.

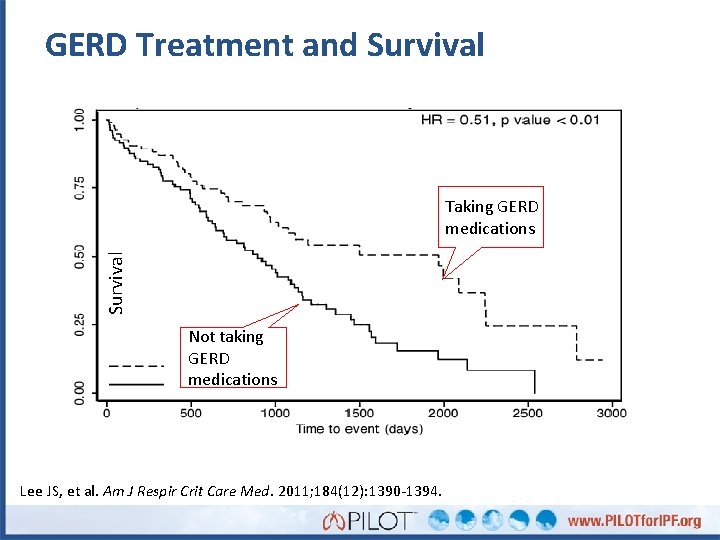

GERD Treatment and Survival Taking GERD medications Not taking GERD medications Lee JS, et al. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2011; 184(12): 1390 -1394.

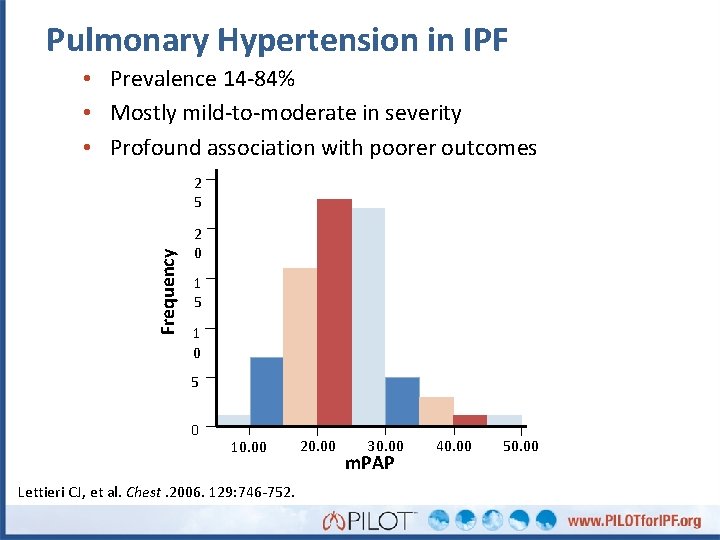

Pulmonary Hypertension in IPF • Prevalence 14 -84% • Mostly mild-to-moderate in severity • Profound association with poorer outcomes Frequency 2 5 2 0 1 5 1 0 5 0 10. 00 Lettieri CJ, et al. Chest. 2006. 129: 746 -752. 20. 00 30. 00 m. PAP 40. 00 50. 00

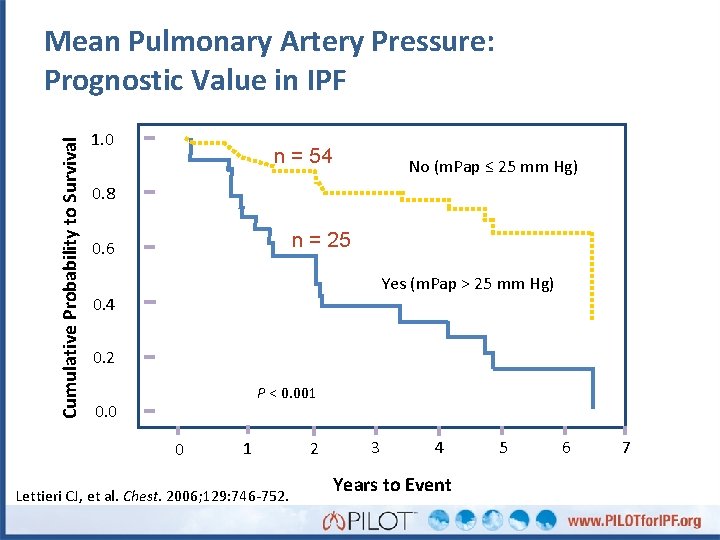

Cumulative Probability to Survival Mean Pulmonary Artery Pressure: Prognostic Value in IPF 1. 0 n = 54 No (m. Pap ≤ 25 mm Hg) 0. 8 n = 25 0. 6 Yes (m. Pap > 25 mm Hg) 0. 4 0. 2 P < 0. 001 0. 0 0 1 Lettieri CJ, et al. Chest. 2006; 129: 746 -752. 2 3 4 Years to Event 5 6 7

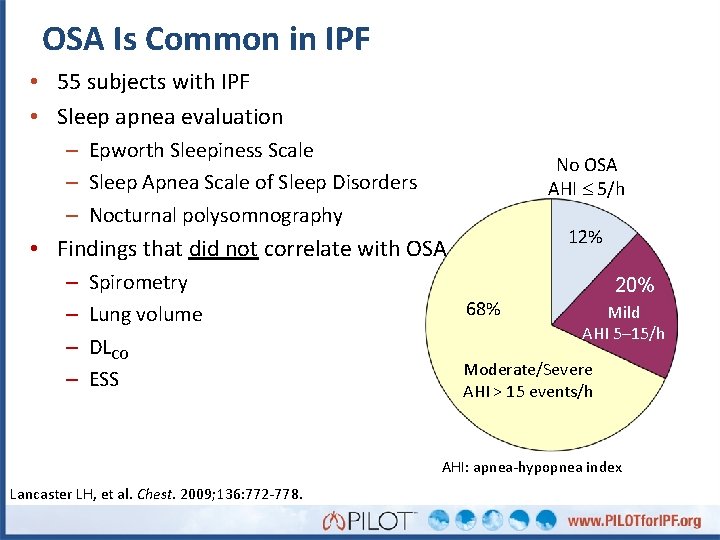

OSA Is Common in IPF • 55 subjects with IPF • Sleep apnea evaluation – Epworth Sleepiness Scale – Sleep Apnea Scale of Sleep Disorders – Nocturnal polysomnography No OSA AHI 5/h 12% • Findings that did not correlate with OSA – – Spirometry Lung volume DLCO ESS 68% 20% Mild AHI 5– 15/h Moderate/Severe AHI > 15 events/h AHI: apnea-hypopnea index Lancaster LH, et al. Chest. 2009; 136: 772 -778.

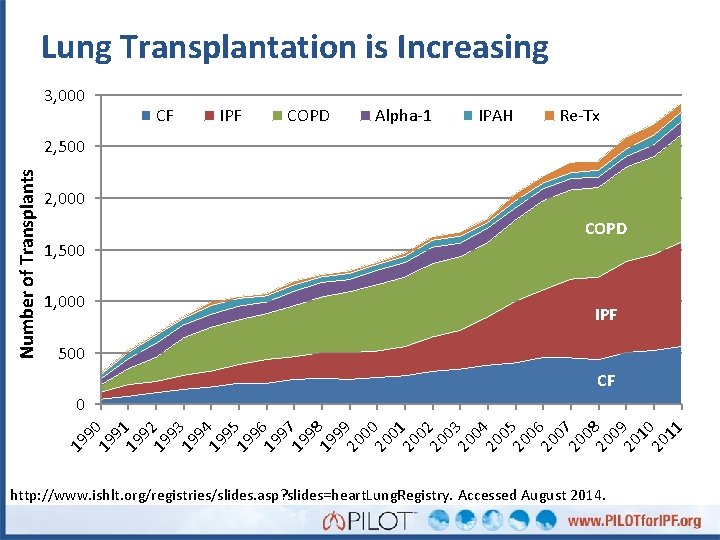

Lung Transplantation is Increasing 3, 000 CF IPF COPD Alpha-1 IPAH Re-Tx Number of Transplants 2, 500 2, 000 COPD 1, 500 1, 000 IPF 500 CF 9 19 2 9 19 3 9 19 4 9 19 5 96 19 97 19 98 19 99 20 00 20 01 20 02 20 03 20 0 20 4 0 20 5 0 20 6 07 20 08 20 09 20 10 20 11 19 91 19 19 90 0 http: //www. ishlt. org/registries/slides. asp? slides=heart. Lung. Registry. Accessed August 2014.

Lung Transplantation for IPF: 2014 Referral Guidelines • Histopathologic or radiographic evidence of usual interstitial pneumonitis (UIP) • Abnormal lung function: FVC < 80% predicted or DLCO < 40% predicted • Any dyspnea or functional limitation attributable to lung disease • Any oxygen requirement, even if only during exertion Weill D, et al. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2015; 34(1): 1 -15.

Timing of Listing for Lung Transplantation • 10% or greater drop in FVC during 6 months of follow- up (note: even a 5% drop is associated with a poorer prognosis and may warrant listing) • 15% or greater drop in DLCO during 6 months of follow- up • Desaturation to < 88% or distance < 250 m on 6 MWT, or > 50 m decline in 6 MWD over a six month period • Pulmonary hypertension on right heart catheterization or 2 D echo • Hospitalization due to respiratory decline, pneumothorax, or acute exacerbation Weill D, et al. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2015; 34(1): 1 -15.

Oxygen Therapy • Goal: Maintain Sp. O 2 > 89% – Rest, activity, sleep • Give patients control over their disease • Make sure patients are using O 2 correctly • Regular assessment – Nocturnal oximetry (yearly or with change in status) – Exercise oximetry (Q 3 months) • Special requirements for air travel (TSA)

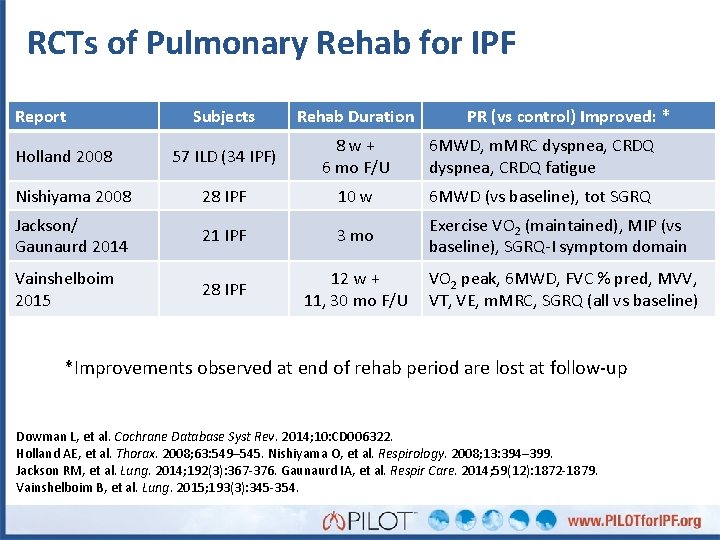

RCTs of Pulmonary Rehab for IPF Report Subjects Rehab Duration 57 ILD (34 IPF) 8 w + 6 mo F/U 6 MWD, m. MRC dyspnea, CRDQ fatigue Nishiyama 2008 28 IPF 10 w 6 MWD (vs baseline), tot SGRQ Jackson/ Gaunaurd 2014 21 IPF 3 mo Exercise VO 2 (maintained), MIP (vs baseline), SGRQ-I symptom domain Vainshelboim 2015 28 IPF Holland 2008 PR (vs control) Improved: * 12 w + VO 2 peak, 6 MWD, FVC % pred, MVV, 11, 30 mo F/U VT, VE, m. MRC, SGRQ (all vs baseline) *Improvements observed at end of rehab period are lost at follow-up Dowman L, et al. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014; 10: CD 006322. Holland AE, et al. Thorax. 2008; 63: 549– 545. Nishiyama O, et al. Respirology. 2008; 13: 394– 399. Jackson RM, et al. Lung. 2014; 192(3): 367 -376. Gaunaurd IA, et al. Respir Care. 2014; 59(12): 1872 -1879. Vainshelboim B, et al. Lung. 2015; 193(3): 345 -354.

Patient Communication: Provider Perspective • Discuss disease course, monitoring, therapy options, end–of–life issues – Use tools appropriate to patient • Share next steps – – ILD center referral, if appropriate Consideration of IPF therapy Comorbidity management Lung transplantation evaluation

Patient Communication: Patient Perspective • Give patients a role in their management – Share ILD checklist – Provide information resources – Specific patient actions (rehab, exercise, risk factor reduction, oxygen, etc) – Encourage seeking help from family or support group • Help patients sustain activities of daily life – PR and OT consultations – Palliative care consultation • Individualize care for patient circumstances

Support Groups • Education – From the facilitator/guest speaker – From others in the group • Support – Reduces isolation – Builds community – Shared coping practices • Goal directed activity – Gets patients out of the house • Not for everyone

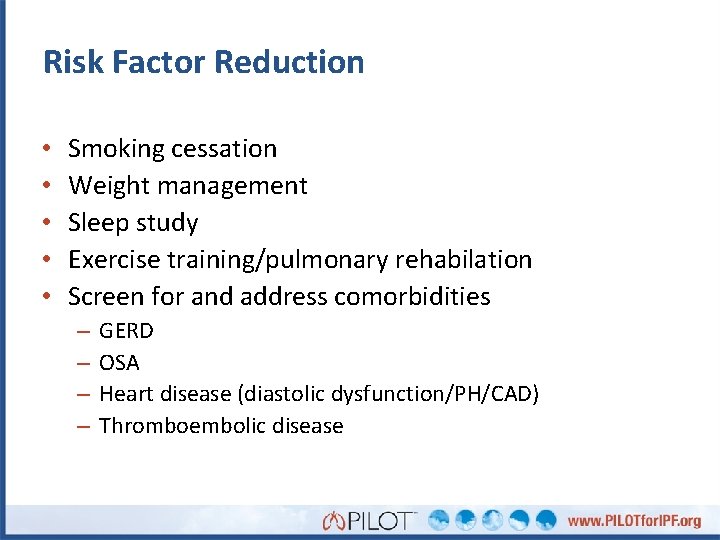

Risk Factor Reduction • • • Smoking cessation Weight management Sleep study Exercise training/pulmonary rehabilation Screen for and address comorbidities – – GERD OSA Heart disease (diastolic dysfunction/PH/CAD) Thromboembolic disease

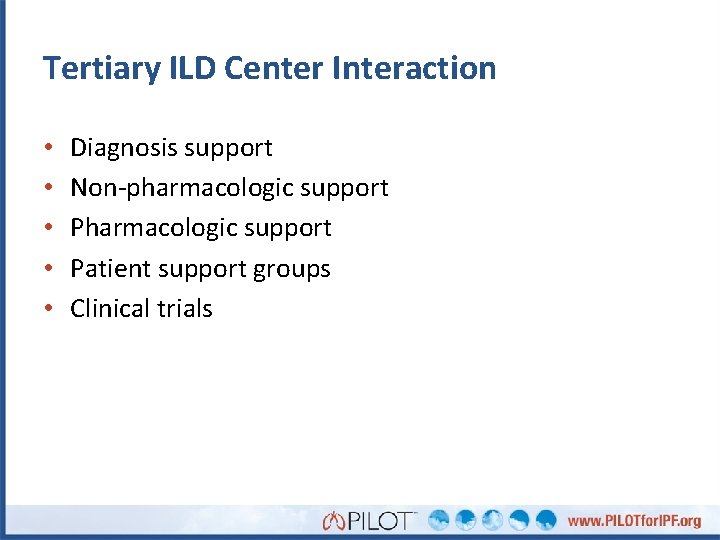

Tertiary ILD Center Interaction • • • Diagnosis support Non-pharmacologic support Patient support groups Clinical trials

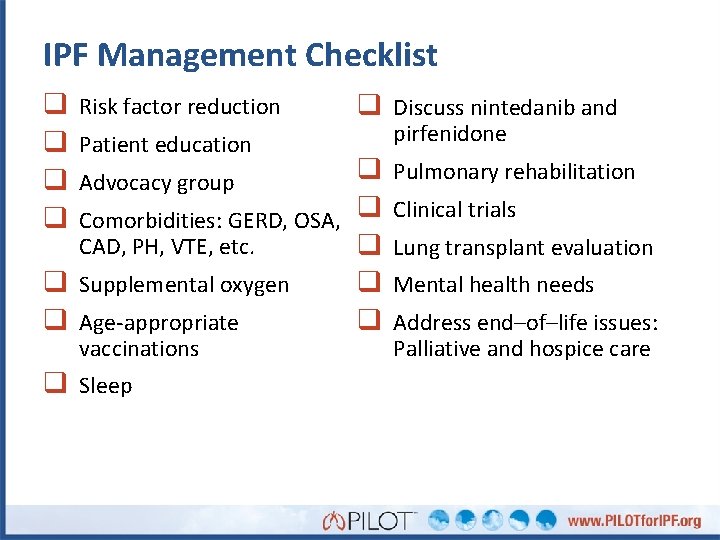

IPF Management Checklist q q Risk factor reduction Patient education q Discuss nintedanib and q Comorbidities: GERD, OSA, q CAD, PH, VTE, etc. q q Supplemental oxygen q q Age-appropriate q Advocacy group vaccinations q Sleep pirfenidone Pulmonary rehabilitation Clinical trials Lung transplant evaluation Mental health needs Address end–of–life issues: Palliative and hospice care

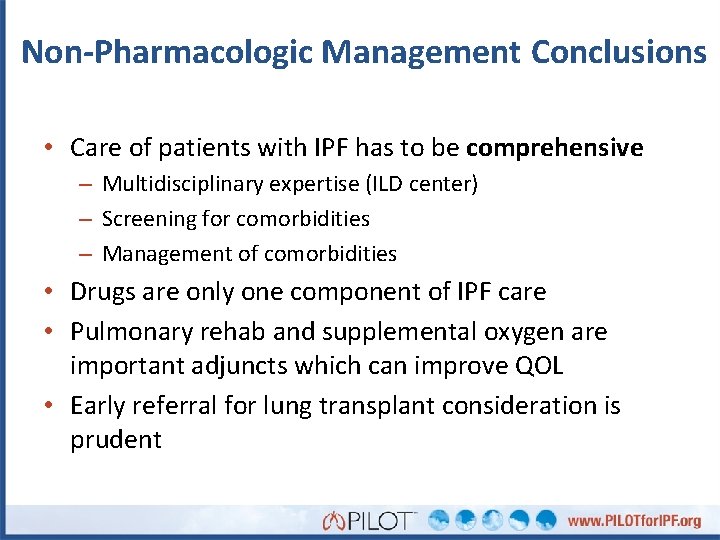

Non-Pharmacologic Management Conclusions • Care of patients with IPF has to be comprehensive – Multidisciplinary expertise (ILD center) – Screening for comorbidities – Management of comorbidities • Drugs are only one component of IPF care • Pulmonary rehab and supplemental oxygen are important adjuncts which can improve QOL • Early referral for lung transplant consideration is prudent

- Slides: 29