Physics 430 Lecture 13 Driven Oscillations and Resonance

- Slides: 9

Physics 430: Lecture 13 Driven Oscillations and Resonance Dale E. Gary NJIT Physics Department

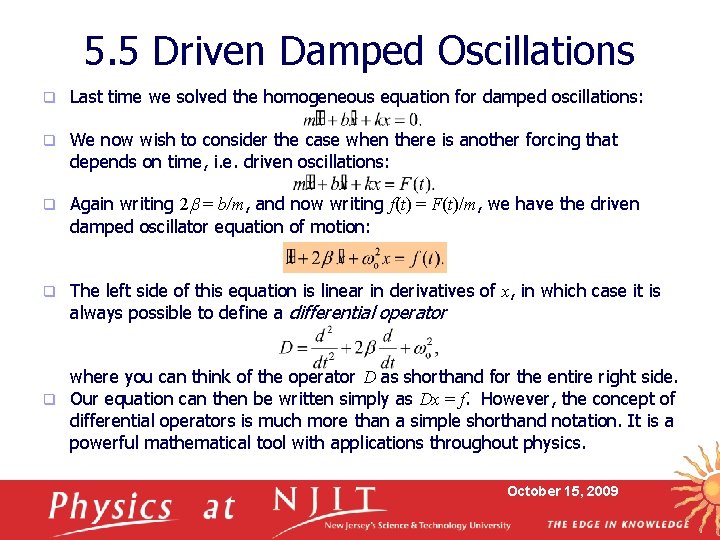

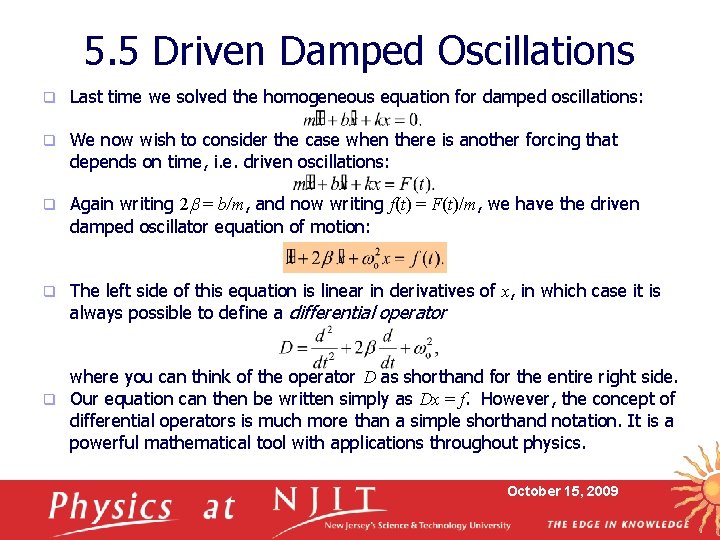

5. 5 Driven Damped Oscillations q Last time we solved the homogeneous equation for damped oscillations: q We now wish to consider the case when there is another forcing that depends on time, i. e. driven oscillations: q Again writing 2 b = b/m, and now writing f(t) = F(t)/m, we have the driven damped oscillator equation of motion: q The left side of this equation is linear in derivatives of x, in which case it is always possible to define a differential operator where you can think of the operator D as shorthand for the entire right side. q Our equation can then be written simply as Dx = f. However, the concept of differential operators is much more than a simple shorthand notation. It is a powerful mathematical tool with applications throughout physics. October 15, 2009

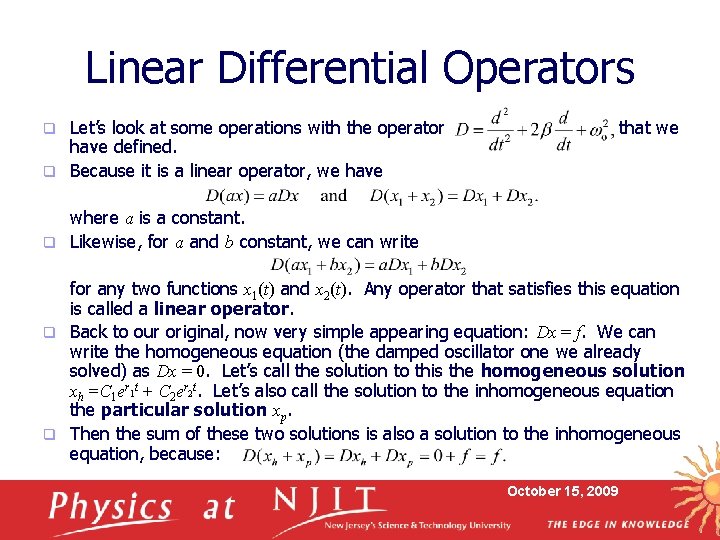

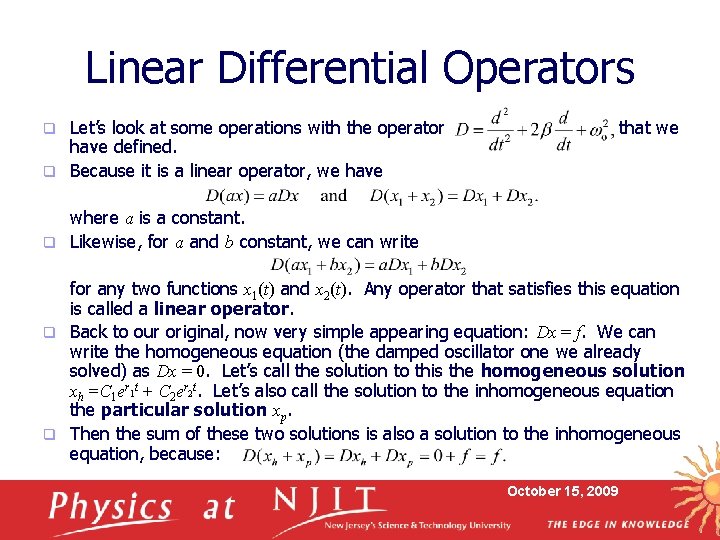

Linear Differential Operators Let’s look at some operations with the operator have defined. q Because it is a linear operator, we have that we q where a is a constant. q Likewise, for a and b constant, we can write for any two functions x 1(t) and x 2(t). Any operator that satisfies this equation is called a linear operator. q Back to our original, now very simple appearing equation: Dx = f. We can write the homogeneous equation (the damped oscillator one we already solved) as Dx = 0. Let’s call the solution to this the homogeneous solution xh =C 1 er 1 t + C 2 er 2 t. Let’s also call the solution to the inhomogeneous equation the particular solution xp. q Then the sum of these two solutions is also a solution to the inhomogeneous equation, because: October 15, 2009

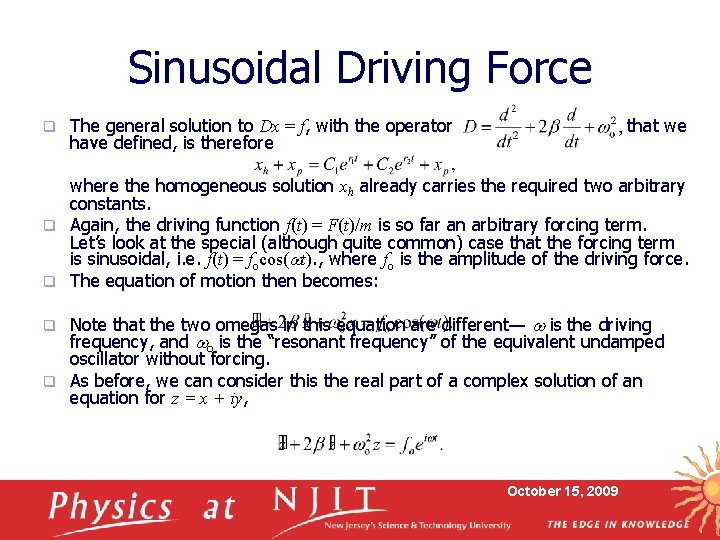

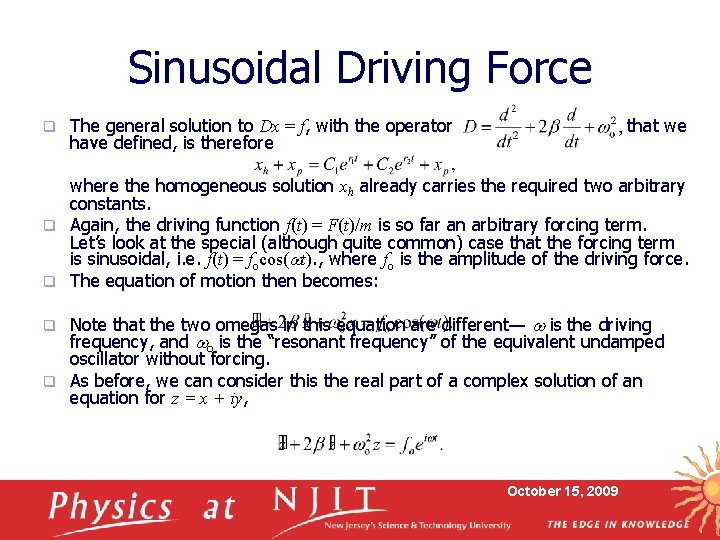

Sinusoidal Driving Force q The general solution to Dx = f, with the operator have defined, is therefore that we where the homogeneous solution xh already carries the required two arbitrary constants. q Again, the driving function f(t) = F(t)/m is so far an arbitrary forcing term. Let’s look at the special (although quite common) case that the forcing term is sinusoidal, i. e. f(t) = focos(wt). , where fo is the amplitude of the driving force. q The equation of motion then becomes: Note that the two omegas in this equation are different— w is the driving frequency, and wo is the “resonant frequency” of the equivalent undamped oscillator without forcing. q As before, we can consider this the real part of a complex solution of an equation for z = x + iy, q October 15, 2009

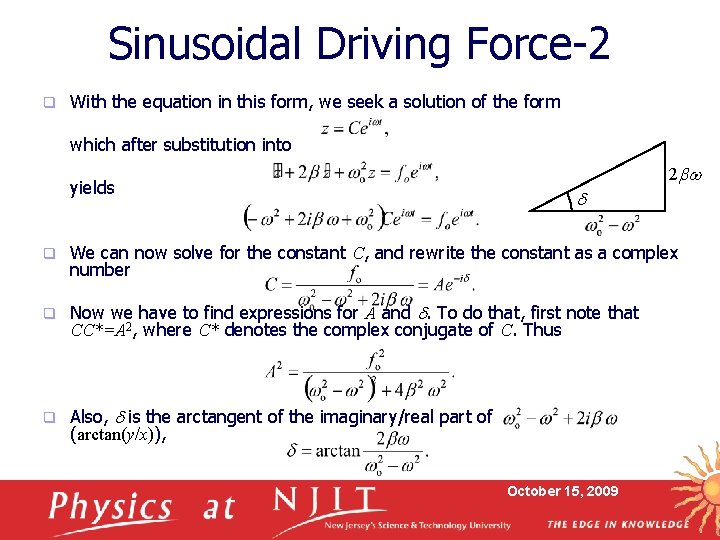

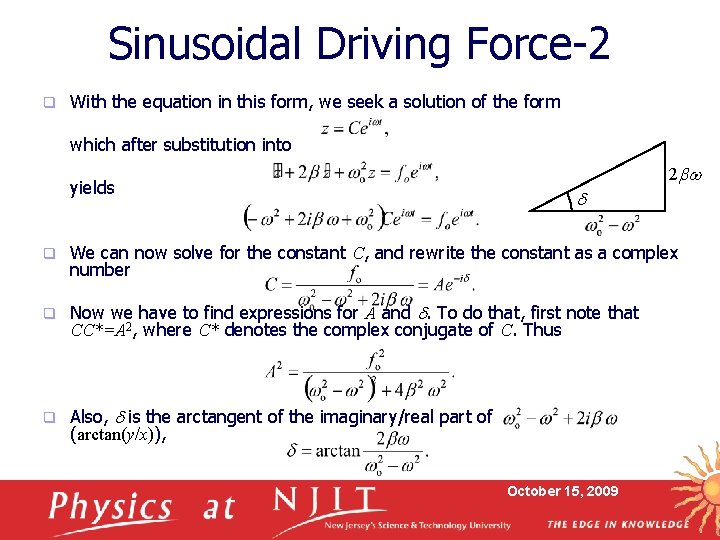

Sinusoidal Driving Force-2 q With the equation in this form, we seek a solution of the form which after substitution into yields 2 bw d q We can now solve for the constant C, and rewrite the constant as a complex number q Now we have to find expressions for A and d. To do that, first note that CC*=A 2, where C* denotes the complex conjugate of C. Thus q Also, d is the arctangent of the imaginary/real part of (arctan(y/x)), October 15, 2009

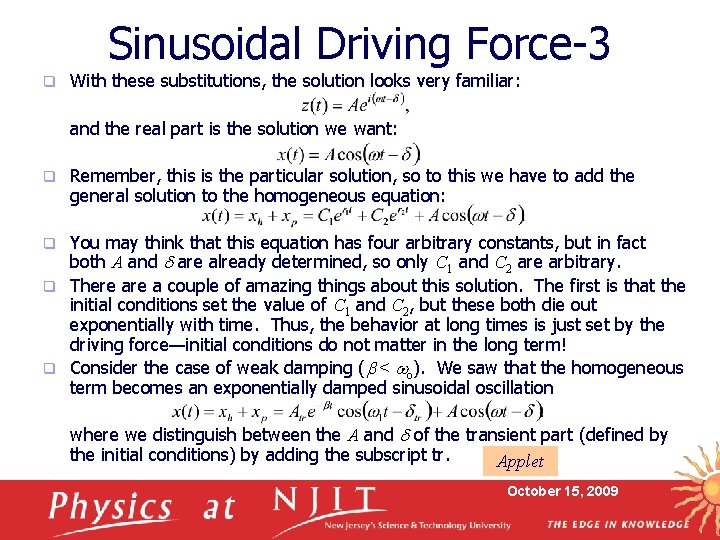

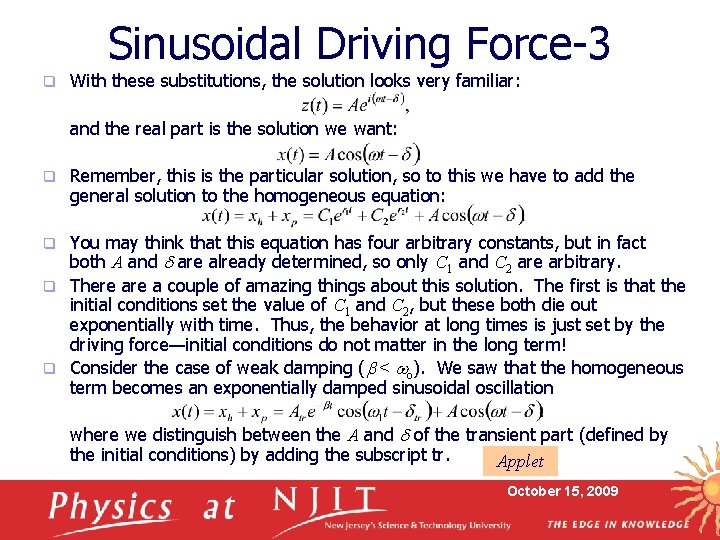

Sinusoidal Driving Force-3 q With these substitutions, the solution looks very familiar: and the real part is the solution we want: q Remember, this is the particular solution, so to this we have to add the general solution to the homogeneous equation: You may think that this equation has four arbitrary constants, but in fact both A and d are already determined, so only C 1 and C 2 are arbitrary. q There a couple of amazing things about this solution. The first is that the initial conditions set the value of C 1 and C 2, but these both die out exponentially with time. Thus, the behavior at long times is just set by the driving force—initial conditions do not matter in the long term! q Consider the case of weak damping (b < wo). We saw that the homogeneous term becomes an exponentially damped sinusoidal oscillation q where we distinguish between the A and d of the transient part (defined by the initial conditions) by adding the subscript tr. Applet October 15, 2009

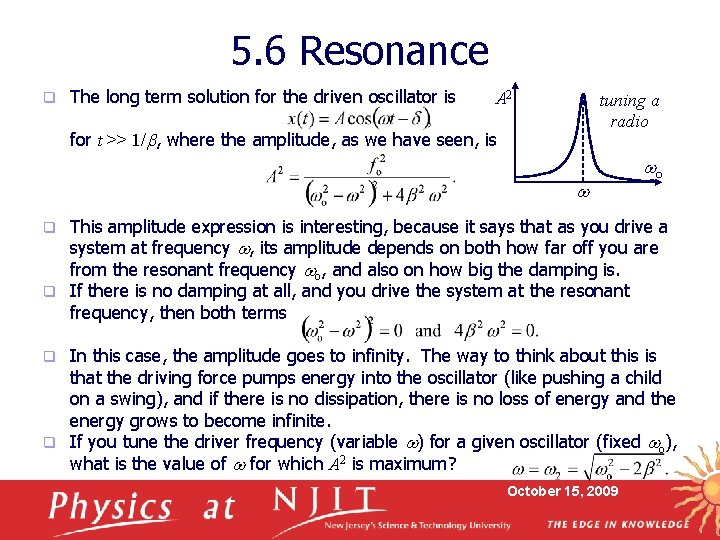

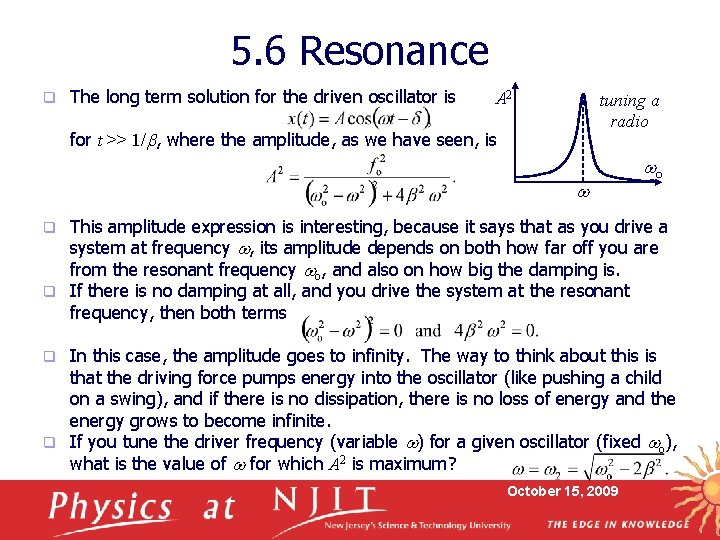

5. 6 Resonance q The long term solution for the driven oscillator is A 2 tuning a radio for t >> 1/b, where the amplitude, as we have seen, is w wo This amplitude expression is interesting, because it says that as you drive a system at frequency w, its amplitude depends on both how far off you are from the resonant frequency wo, and also on how big the damping is. q If there is no damping at all, and you drive the system at the resonant frequency, then both terms q In this case, the amplitude goes to infinity. The way to think about this is that the driving force pumps energy into the oscillator (like pushing a child on a swing), and if there is no dissipation, there is no loss of energy and the energy grows to become infinite. q If you tune the driver frequency (variable w) for a given oscillator (fixed wo), what is the value of w for which A 2 is maximum? q October 15, 2009

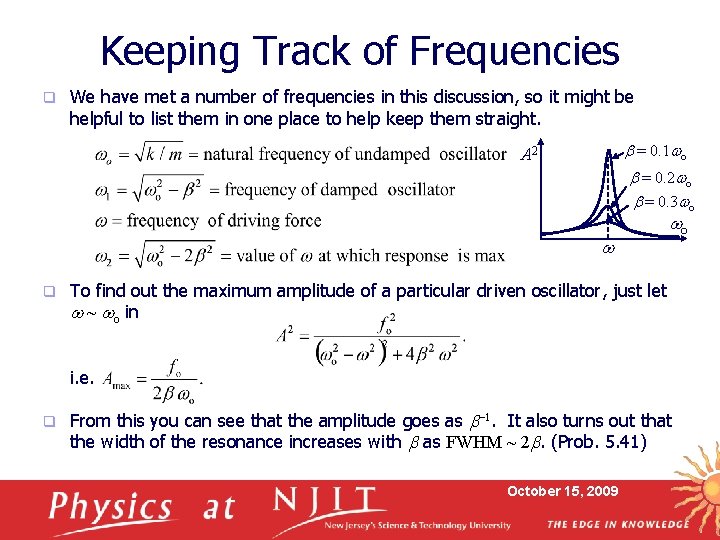

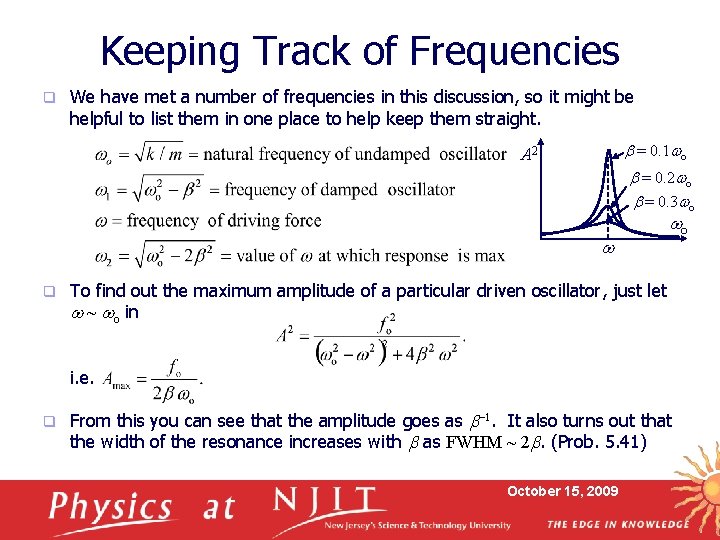

Keeping Track of Frequencies q We have met a number of frequencies in this discussion, so it might be helpful to list them in one place to help keep them straight. b = 0. 1 wo A 2 b = 0. 2 wo b = 0. 3 wo w q wo To find out the maximum amplitude of a particular driven oscillator, just let w ~ wo in i. e. q From this you can see that the amplitude goes as b-1. It also turns out that the width of the resonance increases with b as FWHM ~ 2 b. (Prob. 5. 41) October 15, 2009

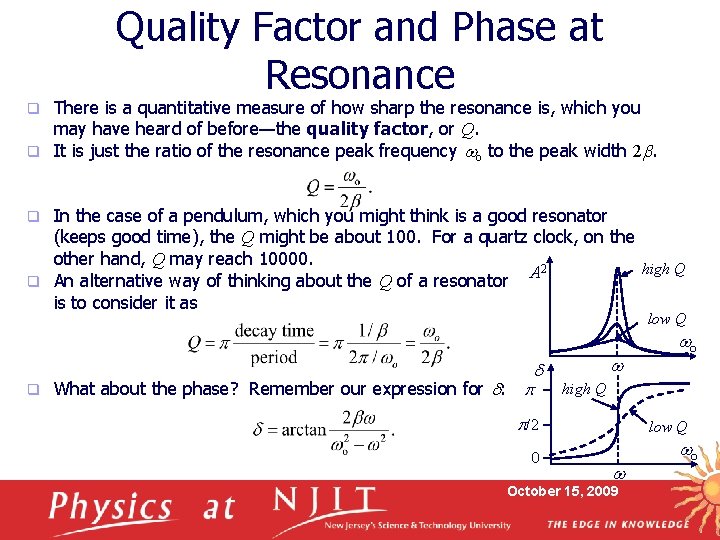

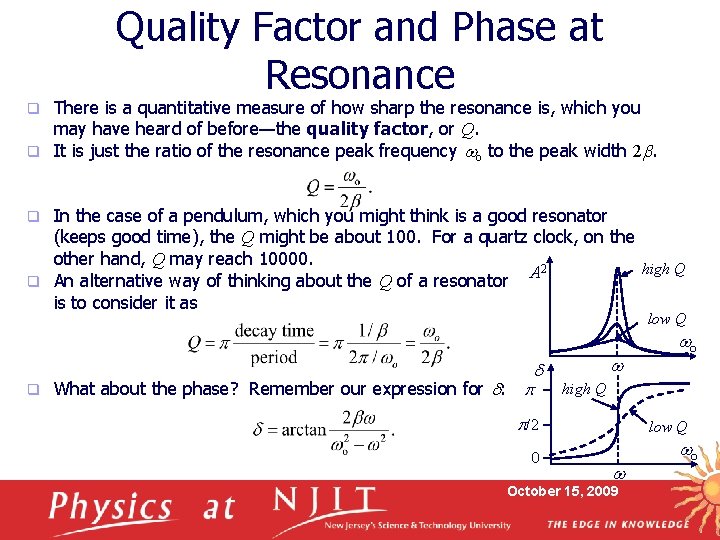

Quality Factor and Phase at Resonance There is a quantitative measure of how sharp the resonance is, which you may have heard of before—the quality factor, or Q. q It is just the ratio of the resonance peak frequency wo to the peak width 2 b. q In the case of a pendulum, which you might think is a good resonator (keeps good time), the Q might be about 100. For a quartz clock, on the other hand, Q may reach 10000. high Q A 2 q An alternative way of thinking about the Q of a resonator is to consider it as q low Q q What about the phase? Remember our expression for d: p d w high Q p/2 0 wo low Q w October 15, 2009 wo