Physical Climate Models n n Simulate behavior of

Physical Climate Models n n Simulate behavior of climate system u Ultimate objective t Understand the key physical, chemical and biological processes that govern climate t Obtain a clearer picture of past climates by comparison with empirical observation t Predict future climate change Models simulate climate on a variety of spatial and temporal scales u Regional climates u Global-scale climate models – simulate the climate of the entire planet

Climate Processes n Three processes that must be considered when constructing a climate model u 1) radiative - the transfer of radiation through the climate system (e. g. absorption, reflection); u 2) dynamic - the horizontal and vertical transfer of energy (e. g. advection, convection, diffusion); u 3) surface process - inclusion of processes involving land/ocean/ice, and the effects of albedo, emissivity and surface-atmosphere energy exchanges

Constructing Climate Models n n Basic laws and relationships necessary to model the climate system are expressed as a series of equations u Equations may be t Empirical derivations based on relationships observed in the real world t Primitive equations that represent theoretical relationships between variables t Combination of the two Equations solved by finite difference methods u Must consider the model resolution in time and space i. e. the time step of the model and the horizontal/vertical scales

Simplifying the Climate System All models must simplify complex climate system u Limited understanding of the climate system u Computational restraints n Simplification may be achieved by limiting u Space and time resolution u Parameterization of the processes that are simulated n

n n n Model Simplification Simplest models are zero order in spatial dimension u The state of the climate system is defined by a single global average Other models include an ever-increasing dimensional complexity u 1 -D, 2 -D and finally to 3 -D models Whatever the spatial dimension, further simplification requires limiting spatial resolution u Limited number of latitude bands in a 1 -D model u Limited number of grid points in a 2 -D model Time resolution of climate models varies substantially, from minutes to years depending on the models and the problem under investigation To preserve computational stability, spatial and temporal resolution must be linked Can pose problems when systems with different equilibrium time scales have to interact as a very different resolution in space and time may be needed

Parameterization n n Involves inclusion of a process as a simplified function rather than an explicit calculation from first principles u Sub-grid scale phenomena, like thunderstorms, must be parameterized t Not possible to deal with these explicitly u Other processes are parameterized to reduce computation required Certain processes omitted from model if their contribution negligible on time scale of interest u Role of deep ocean circulation while modeling changes over time scales of years to decades u Models may handle radiative transfers in detail but neglect or parameterize horizontal energy transport u Models may provide 3 -D representation but contain much less detailed radiative transfer information

Modeling Climate Response n n Ultimate purpose of a model u Identify response of the climate system u Change in the parameters and processes that control the state of the system Climate response occurs to restore equilibrium within the climate system u If radiative forcing associated with an increase in atmospheric CO 2 perturbs the climate system u Model will assess how the climate system responds to this perturbation to restore equilibrium

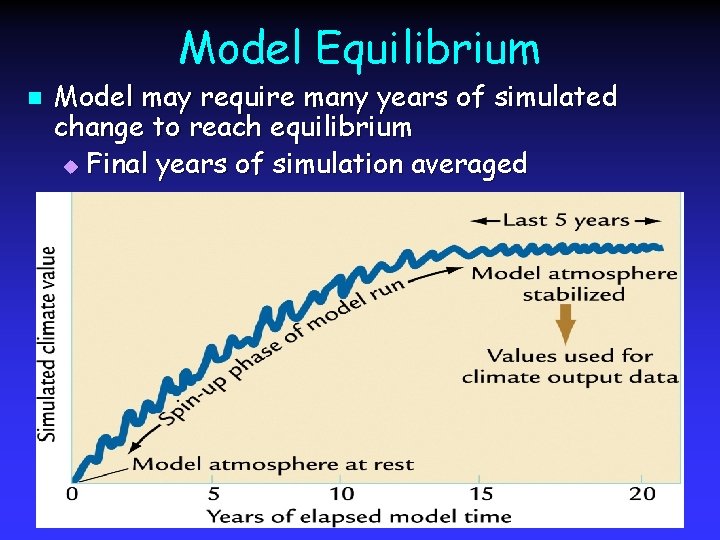

Model Equilibrium n Model may require many years of simulated change to reach equilibrium u Final years of simulation averaged

Nature of the Model n n One of two modes u Equilibrium mode t No account taken of energy storage processes that control evolution of climate response with time t Assume climate responds instantaneously following system perturbation u Transient mode t Inclusion of energy storage processes t Simulate development of a climate response with time Models typically run twice u In a control run with no forcing u In a test run including forcing and perturbation of the climate system

Climate Sensitivity n n n Critical parameters In the most complex models u Climate sensitivity calculated explicitly through simulations of processes involved In simpler models u Climate sensitivity is parameterized by reference to the range of values suggested by the more complex models t This approach, where more sophisticated models are nested in less complex models, is common in the field of climate modeling

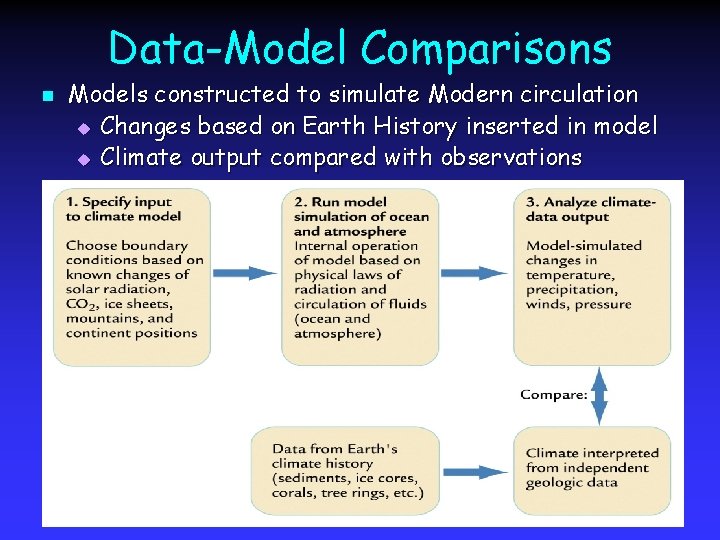

Data-Model Comparisons n Models constructed to simulate Modern circulation u Changes based on Earth History inserted in model u Climate output compared with observations

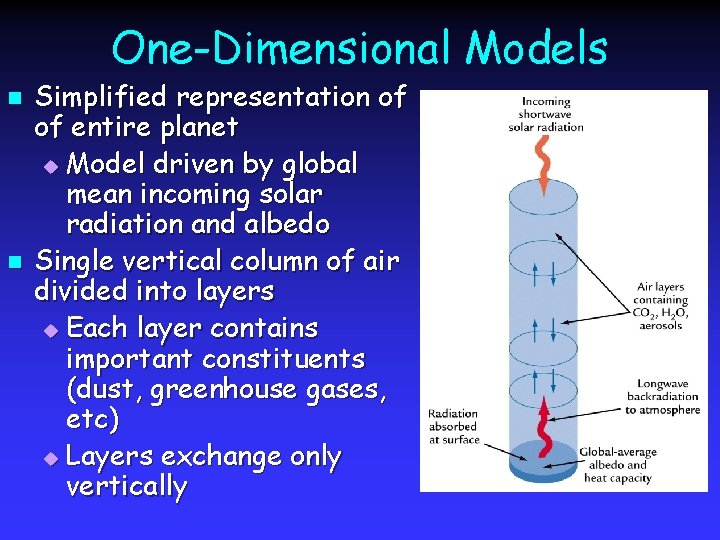

One-Dimensional Models n n Simplified representation of of entire planet u Model driven by global mean incoming solar radiation and albedo Single vertical column of air divided into layers u Each layer contains important constituents (dust, greenhouse gases, etc) u Layers exchange only vertically

Types of Models n n Energy balance models (EBMs) u Simulate two fundamental climate processes t Global radiation balance t Latitudinal (equator-to-pole) energy transfer Radiative-convective models (RCMs) u Simulate detailed energy transfer through the depth of the atmosphere t Radiative transformations that occur as energy is absorbed, emitted and scattered t Role of convection

EBMs n n 0 -D EBMs u Earth is a single point in space u Global radiation balance modeled In 1 -D models latitude is included u Temperature for each latitude band is calculated t Using latitudinal value for albedo, energy flux, etc. u Latitudinal energy transfer estimated from linear empirical relationships t Difference between latitudinal temperature and global average temperature

RBMs n n Surface albedo, cloud amount and atmospheric turbidity u Used to determine heating rates atmospheric layers u Imbalance between net radiation at top and bottom of each layer determined If calculated vertical temperature profile (lapse rate) exceeds some stability criterion (critical lapse rate) u Convection is assumed to take place (i. e. the vertical mixing of air) until the stability criterion is no longer breached

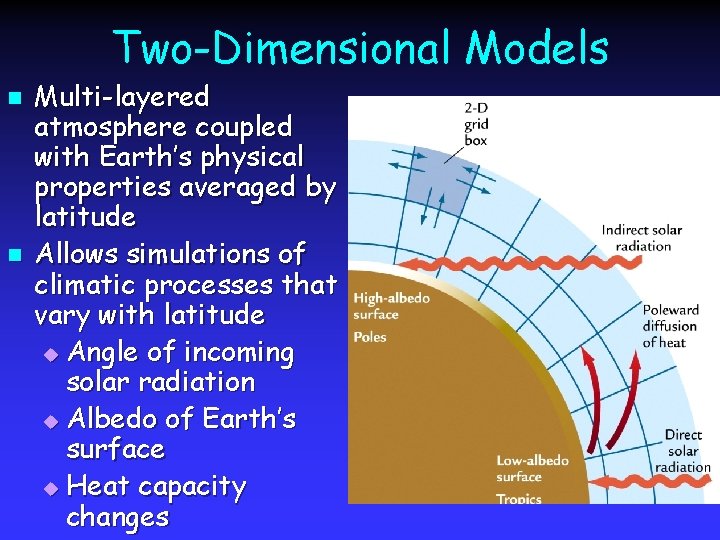

Two-Dimensional Models n n Multi-layered atmosphere coupled with Earth’s physical properties averaged by latitude Allows simulations of climatic processes that vary with latitude u Angle of incoming solar radiation u Albedo of Earth’s surface u Heat capacity changes

Statistical-Dynamical Models n Combine horizontal energy transfer modeled by EBMs with the radiative-convective approach of RCMs u Equator-to-pole energy transfer is more sophisticated t Parameters like wind speed and wind direction modeled by statistical relations t Laws of motion are used to obtain a measure of energy diffusion u Particular useful to investigate role of horizontal energy transfer and processes that directly disturb that transfer

2 -D Models Advantage u Simulate long intervals of time quickly and inexpensively n Disadvantage u Not sensitive to climate processes that depend on geographic position of continents and oceans n

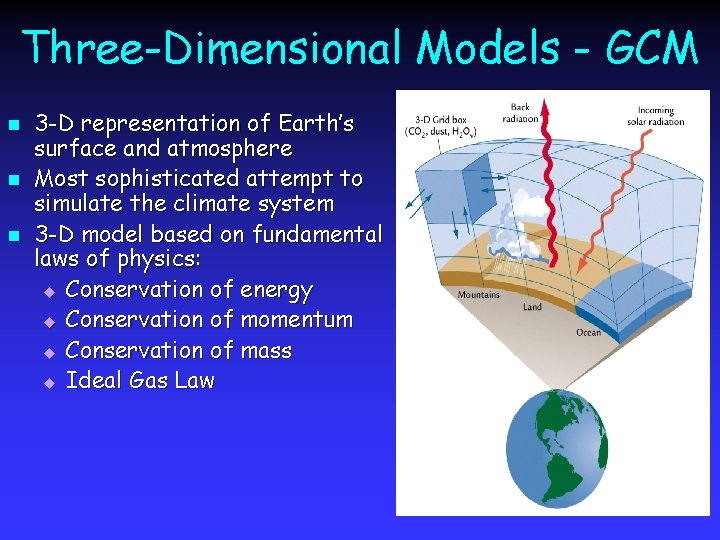

Three-Dimensional Models - GCM n n n 3 -D representation of Earth’s surface and atmosphere Most sophisticated attempt to simulate the climate system 3 -D model based on fundamental laws of physics: u Conservation of energy u Conservation of momentum u Conservation of mass u Ideal Gas Law

GCMs Represent key features affecting climate u Spatial distribution of land, water, ice u Regional variation in heat capacity and albedo of surface u Elevation of mountains and glaciers u Concentrations of greenhouse gases u Seasonal variations in solar radiation n Calculations at interactions of grid boxes n

GCMs n n n Atmospheric variables at each grid point requires the storage, retrieval, recalculation and re-storage of 10 5 figures at every time-step u Models contain thousands of grid points u GCMs are computationally expensive Can provide accurate representations of planetary climate u Simulate global and continental scale processes in detail GCMs cannot simulate synoptic regional meteorological phenomena (e. g. , tropical storms) u Play an important part in the latitudinal transfer of energy and momentum u Spatial resolution of GCMs limited in vertical dimension t Many boundary layer processes must be parameterized

Sensitivity Test n n Control case established u Modern climate simulated One boundary condition altered at a time u Model output compared with present day climate simulation u Information reveals impact of that boundary condition u Boundary condition examples t Continental configuration t Ice sheet expansion t Solar radiation influx t Greenhouse gas concentrations

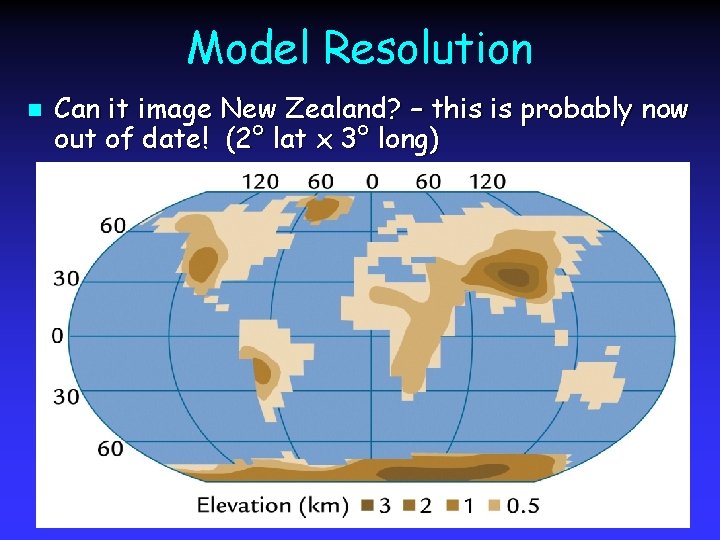

Model Resolution n Can it image New Zealand? – this is probably now out of date! (2° lat x 3° long)

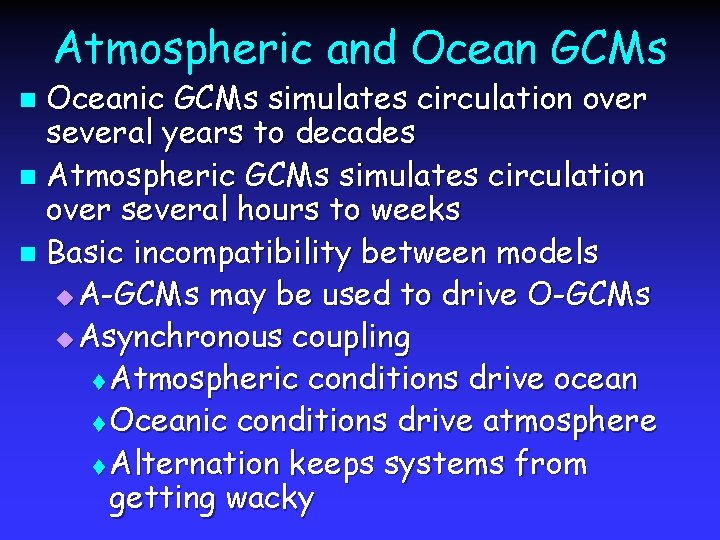

Atmospheric and Ocean GCMs Atmospheric GCM more sophisticated u Much detail known about atmospheric circulation, elevations, landmasses, etc. n Ocean GCM primitive u Rudimentary knowledge of oceanic circulation t Deep water formation u Difficult to model important small features t Fast-moving narrow currents n

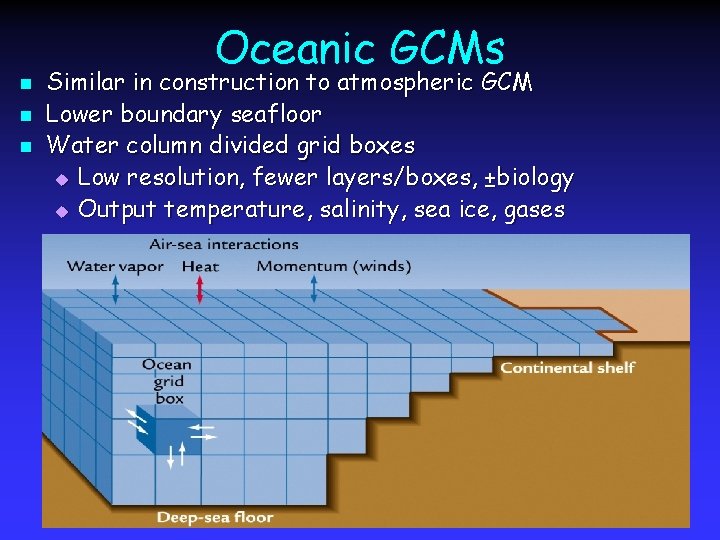

n n n Oceanic GCMs Similar in construction to atmospheric GCM Lower boundary seafloor Water column divided grid boxes u Low resolution, fewer layers/boxes, ±biology u Output temperature, salinity, sea ice, gases

Atmospheric and Ocean GCMs Oceanic GCMs simulates circulation over several years to decades n Atmospheric GCMs simulates circulation over several hours to weeks n Basic incompatibility between models u A-GCMs may be used to drive O-GCMs u Asynchronous coupling t Atmospheric conditions drive ocean t Oceanic conditions drive atmosphere t Alternation keeps systems from getting wacky n

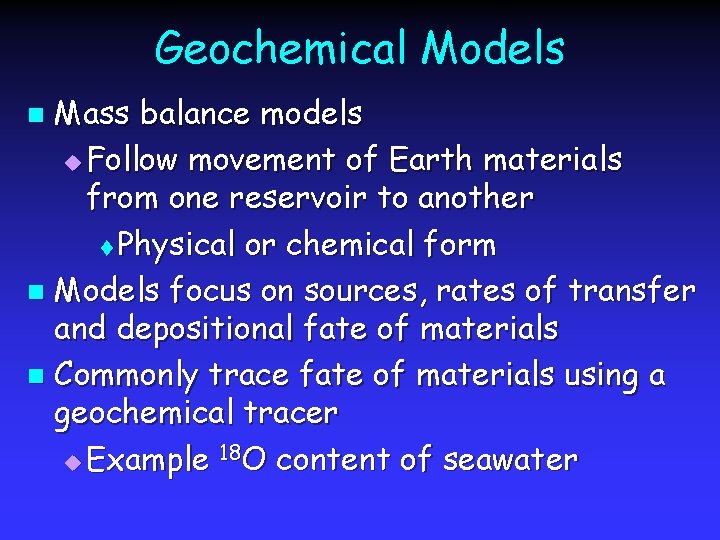

Geochemical Models Mass balance models u Follow movement of Earth materials from one reservoir to another t Physical or chemical form n Models focus on sources, rates of transfer and depositional fate of materials n Commonly trace fate of materials using a geochemical tracer u Example 18 O content of seawater n

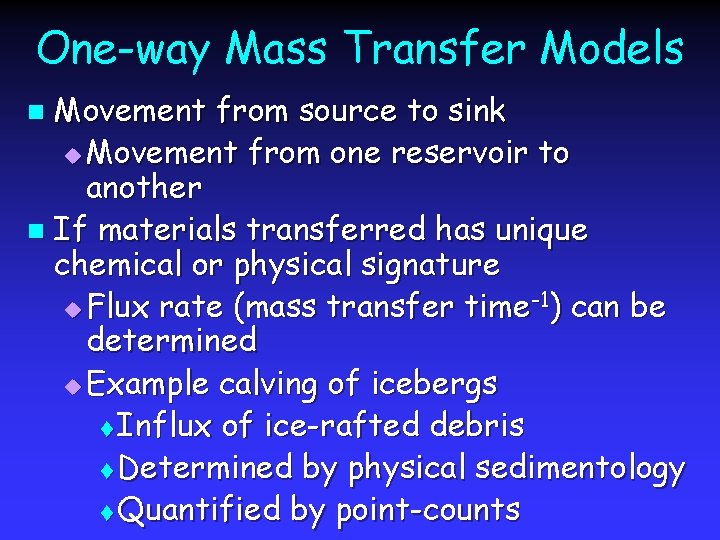

One-way Mass Transfer Models Movement from source to sink u Movement from one reservoir to another n If materials transferred has unique chemical or physical signature u Flux rate (mass transfer time-1) can be determined u Example calving of icebergs t Influx of ice-rafted debris t Determined by physical sedimentology t Quantified by point-counts n

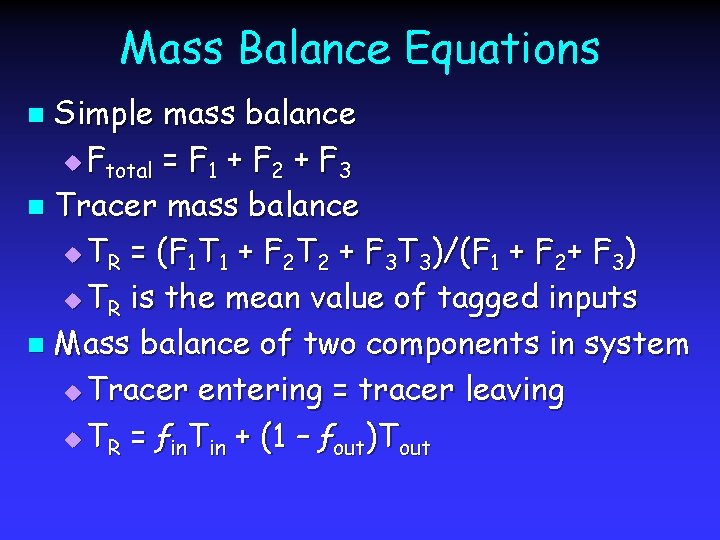

Mass Balance Equations Simple mass balance u Ftotal = F 1 + F 2 + F 3 n Tracer mass balance u TR = (F 1 T 1 + F 2 T 2 + F 3 T 3)/(F 1 + F 2+ F 3) u TR is the mean value of tagged inputs n Mass balance of two components in system u Tracer entering = tracer leaving u TR = ƒin. Tin + (1 – ƒout)Tout n

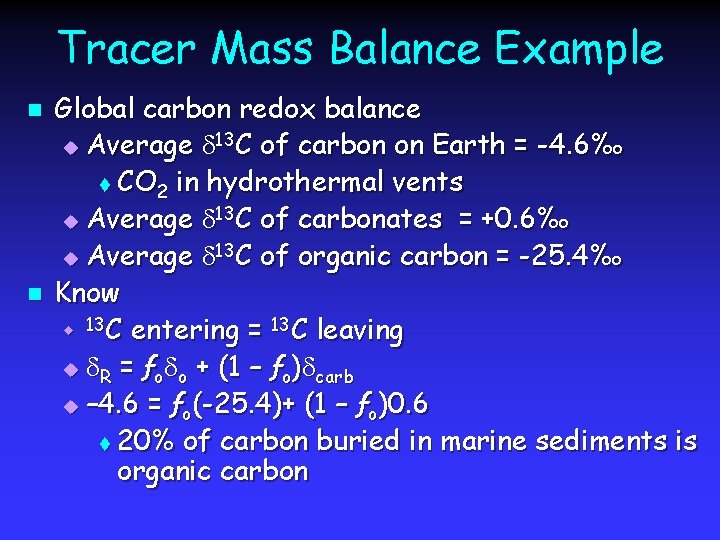

Tracer Mass Balance Example n n Global carbon redox balance u Average d 13 C of carbon on Earth = -4. 6‰ t CO 2 in hydrothermal vents u Average d 13 C of carbonates = +0. 6‰ u Average d 13 C of organic carbon = -25. 4‰ Know u 13 C entering = 13 C leaving u d. R = ƒodo + (1 – ƒo)dcarb u – 4. 6 = ƒo(-25. 4)+ (1 – ƒo)0. 6 t 20% of carbon buried in marine sediments is organic carbon

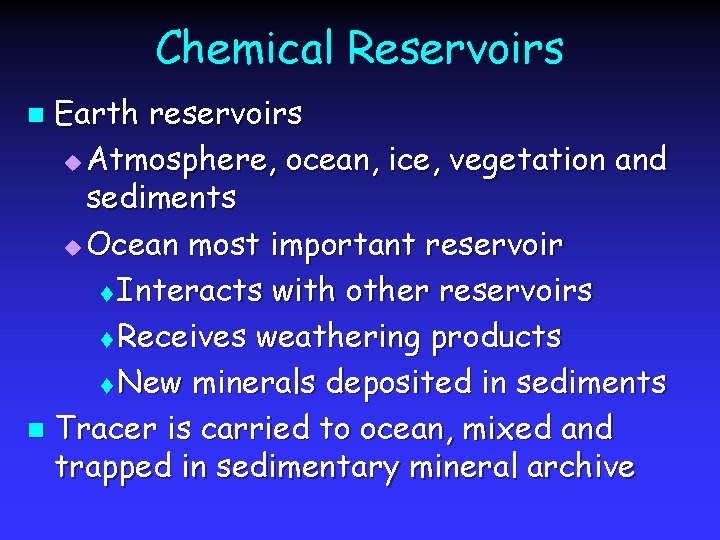

Chemical Reservoirs Earth reservoirs u Atmosphere, ocean, ice, vegetation and sediments u Ocean most important reservoir t Interacts with other reservoirs t Receives weathering products t New minerals deposited in sediments n Tracer is carried to ocean, mixed and trapped in sedimentary mineral archive n

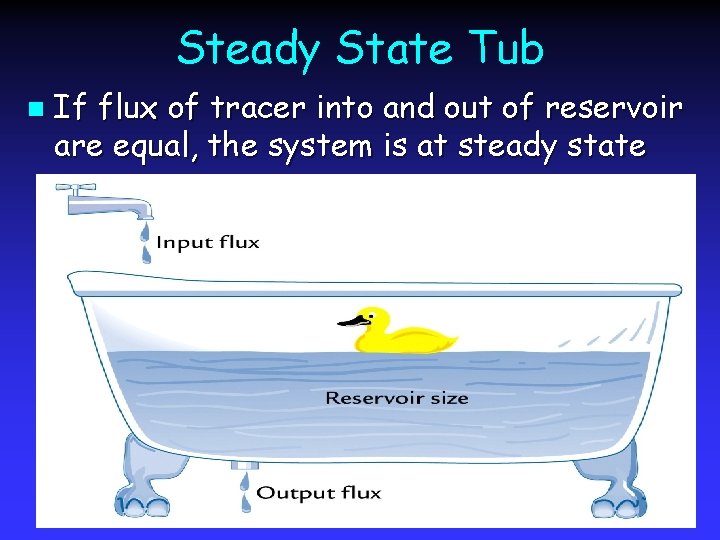

Steady State Tub n If flux of tracer into and out of reservoir are equal, the system is at steady state

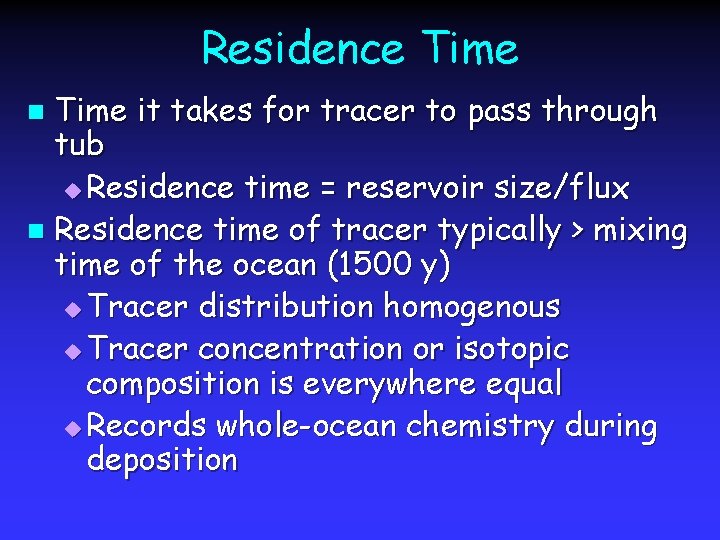

Residence Time it takes for tracer to pass through tub u Residence time = reservoir size/flux n Residence time of tracer typically > mixing time of the ocean (1500 y) u Tracer distribution homogenous u Tracer concentration or isotopic composition is everywhere equal u Records whole-ocean chemistry during deposition n

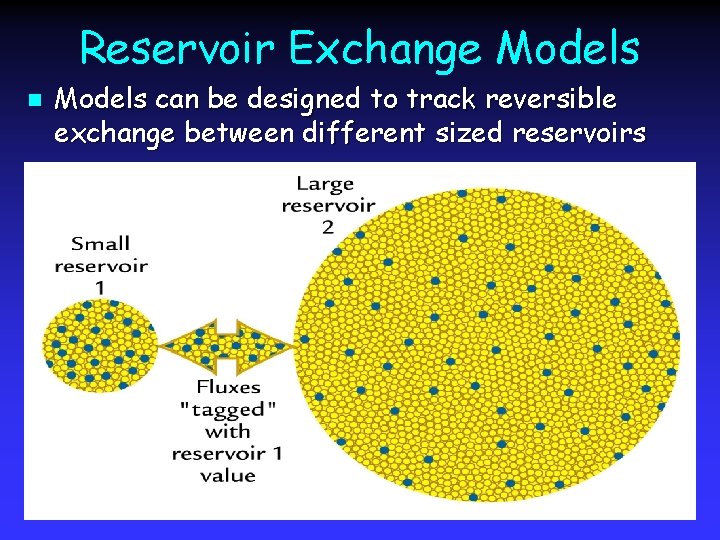

Reservoir Exchange Models n Models can be designed to track reversible exchange between different sized reservoirs

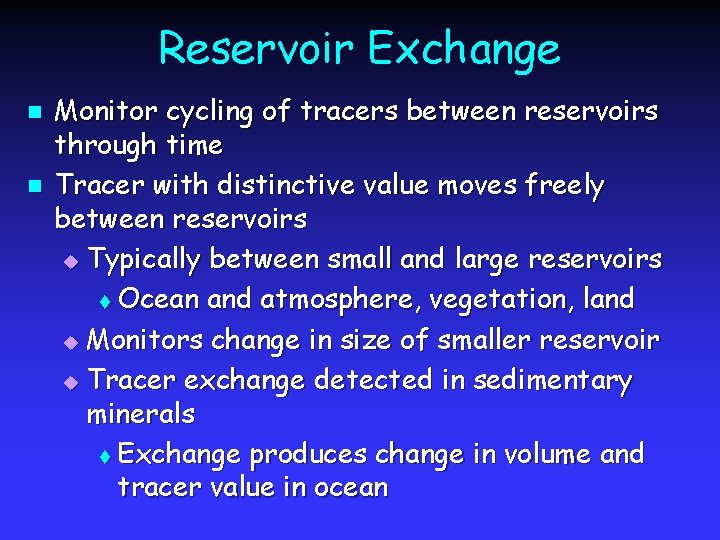

Reservoir Exchange n n Monitor cycling of tracers between reservoirs through time Tracer with distinctive value moves freely between reservoirs u Typically between small and large reservoirs t Ocean and atmosphere, vegetation, land u Monitors change in size of smaller reservoir u Tracer exchange detected in sedimentary minerals t Exchange produces change in volume and tracer value in ocean

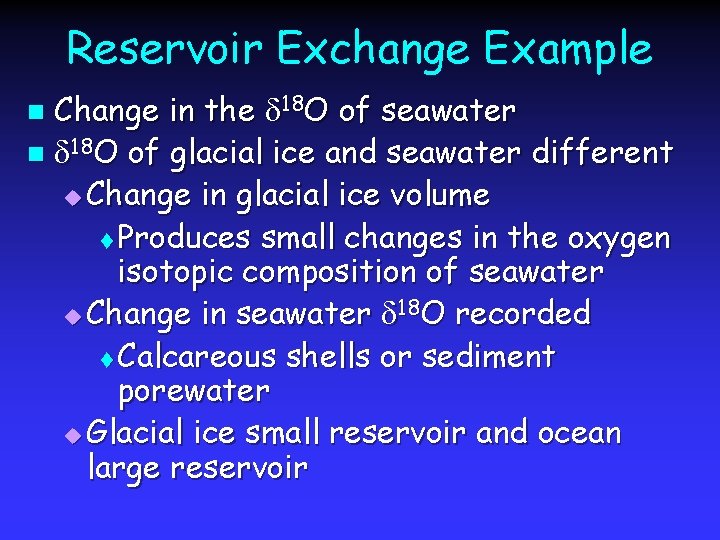

Reservoir Exchange Example Change in the d 18 O of seawater n d 18 O of glacial ice and seawater different u Change in glacial ice volume t Produces small changes in the oxygen isotopic composition of seawater u Change in seawater d 18 O recorded t Calcareous shells or sediment porewater u Glacial ice small reservoir and ocean large reservoir n

Time-Dependent Models n n n Most geochemical models assume steady-state conditions Time-dependent models assume steady-state only during equilibrium conditions Steady-state conditions imply no change in reservoir size u Time-dependent models allow changes in reservoir size u From one equilibrium state to another u Under equilibrium t Steady-state conditions prevail

CO 2 and Long-Term Climate n What has moderated Earth surface temperature over the last 4. 55 by so that u All surface vegetation did not spontaneously catch on fire and all lakes and oceans vaporize? u All lakes and ocean did not freeze solid?

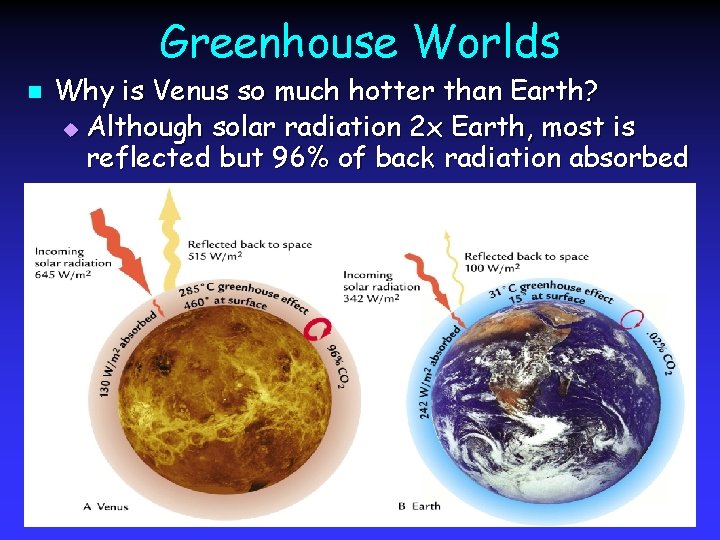

Greenhouse Worlds n Why is Venus so much hotter than Earth? u Although solar radiation 2 x Earth, most is reflected but 96% of back radiation absorbed

What originally controlled C? n n In solar nebula most carbon was CH 4 u Lost from Earth and Venus u Earth captured 1 in 3000 carbon atoms t Tiny carbon fraction in the atmosphere as CO 2 • 60 out of every million C atoms t Bulk of carbon in sediments on Earth • Ca. CO 3 (limestone and dolostone) and organic residues (kerogen) u Venus probably had similar early planetary history t Most carbon is in atmosphere as CO 2 Venus has conditions that would prevail on Earth u All CO 2 locked up in sediments were released to the atmosphere

Earth and Venus n n Water balance different on Earth and Venus If Venus and Earth started with same components u Venus should have either t Sizable oceans t Atmosphere dominated by steam u H present initially as H 2 O escaped to space t H 2 O transported "top" of the Venusian atmosphere t Disassociated forming H and O atoms t H escaped the atmosphere t Oxygen stirred back to surface • Reacted with iron forming iron oxide

Planetary Evolution Similar Although Earth and Venus started with same components u Earth evolved such that carbon safely buried in early sediments t Avoiding runaway greenhouse effect n Venus built up CO 2 in the atmosphere u Build-up led to high temperature t High enough to kill all life • If life ever did get a foothold u Once hot, could not cool n

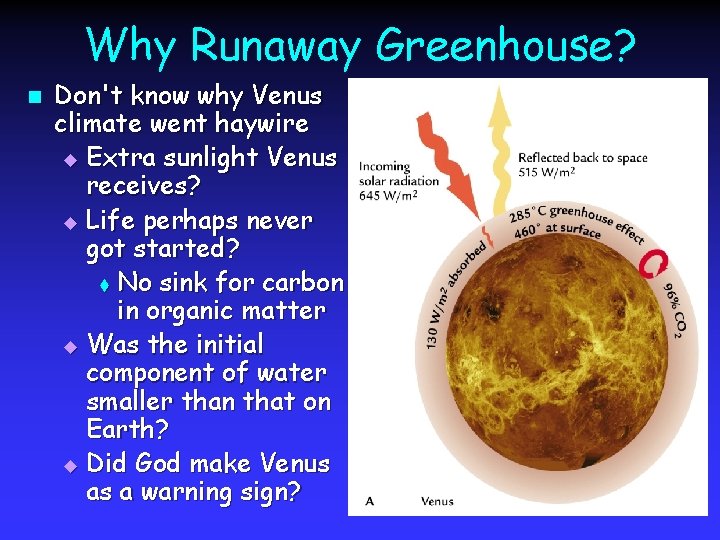

Why Runaway Greenhouse? n Don't know why Venus climate went haywire u Extra sunlight Venus receives? u Life perhaps never got started? t No sink for carbon in organic matter u Was the initial component of water smaller than that on Earth? u Did God make Venus as a warning sign?

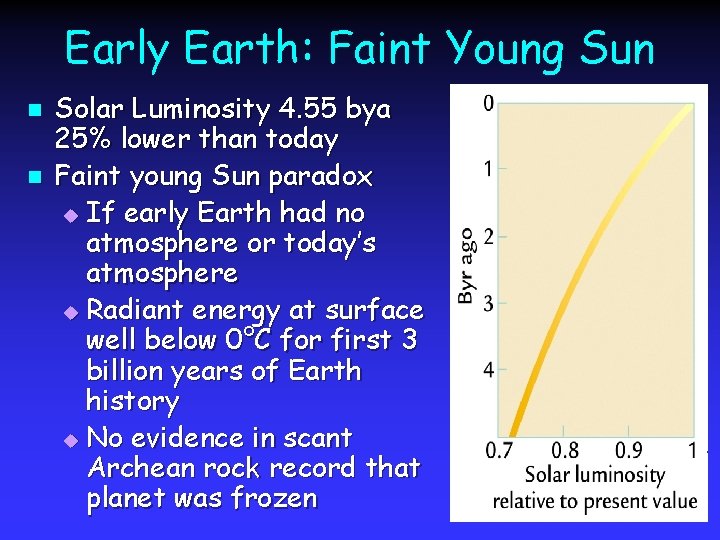

Early Earth: Faint Young Sun n n Solar Luminosity 4. 55 bya 25% lower than today Faint young Sun paradox u If early Earth had no atmosphere or today’s atmosphere u Radiant energy at surface well below 0°C for first 3 billion years of Earth history u No evidence in scant Archean rock record that planet was frozen

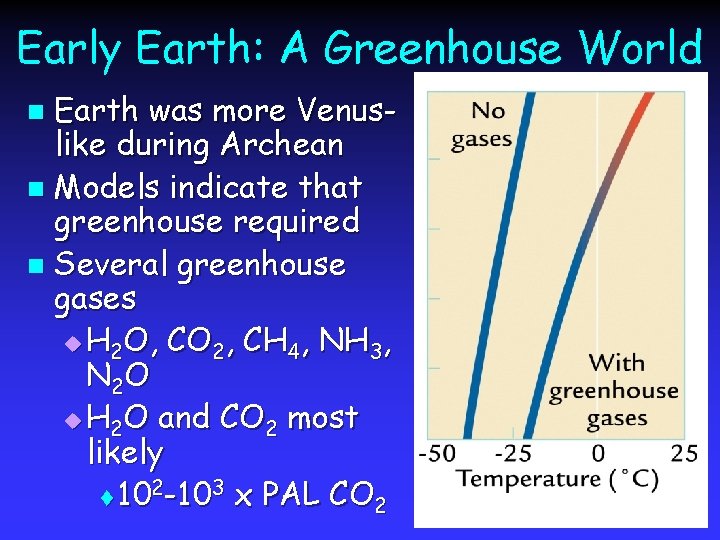

Early Earth: A Greenhouse World Earth was more Venuslike during Archean n Models indicate that greenhouse required n Several greenhouse gases u H 2 O, CO 2, CH 4, NH 3, N 2 O u H 2 O and CO 2 most likely t 102 -103 x PAL CO 2 n

Archean Atmosphere n Faint young Sun paradox presents dilemma u 1) What is the source for high levels of greenhouse gases in Earth’s earliest atmosphere? u 2) How were those gases removed with time? t Models indicate Sun’s strength increased slowly with time t Geologic record strongly suggests Earth maintained a moderate climate throughout Earth history (i. e. , no runaway greenhouse like on Venus)

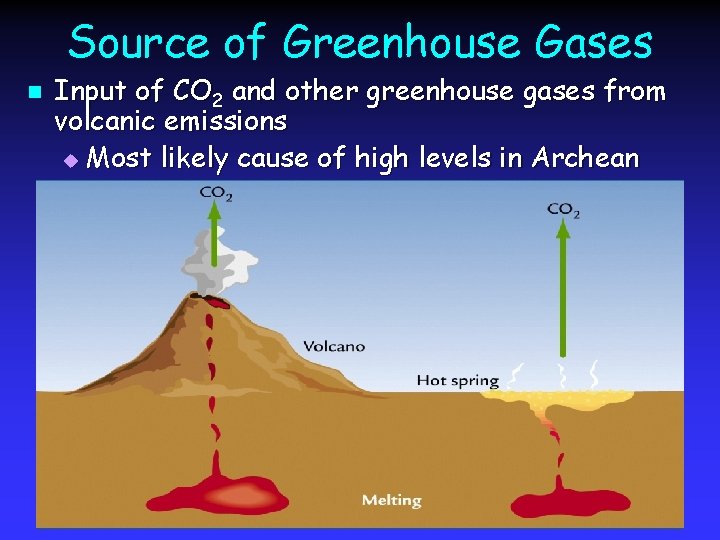

Source of Greenhouse Gases n Input of CO 2 and other greenhouse gases from volcanic emissions u Most likely cause of high levels in Archean

- Slides: 47