Perspectives of ICTs 1 The technocentric perspective n

- Slides: 30

Perspectives of ICTs 1

The techno-centric perspective n n n In much utopian writing, ICTs represent a revolutionary force that can fundamentally transform societies and individual lives. In this perspective, the imperatives of technological development determine social arrangements: technological potential drives history Furthermore, the techno-centric perspective holds that the. digital revolution. definitively marks the passage of world history into a post-industrial stage. The emerging global information society is characterized by positive features: there will be more effective health care, better education, more information and diversity of culture. New digital technologies create more choice for people in education, shopping, entertainment, news media and travel. 2

The techno-centric perspective n n The gravest problem with the techno-centric perspective is that it ignores the social origins of information and communication technologies. It suggests that they originate in a socio-economic vacuum, and fails to see the specific interests that generate them. Guided by this perspective, policy makers find it very difficult to accept that technological innovations do not, in and of themselves, create the institutional arrangements within which they function; and thus they fail to see that whether the potential of technologies will be realized in positive rather than negative ways depends much more on their institutional organization than on the features of their technical performance. 3

n n n The perspective of discontinuity The techno-centric perspective is characterized by a strong emphasis upon the discontinuity of historical processes. Its analytical approach is based upon the notion that a technological discontinuity (the Digital revolution) causes a social discontinuity In its fascination with revolutions, the perspective overlooks the fact that technological processes are only rarely revolutionary and most often proceed in gradual ways over longer periods of time. Technological developments can hardly ever be described as radical breakthroughs. Studies on technological inventions usually demonstrate that innovations have (often long) pre-histories of conceptual and technical development. u Thus today’s ICTs evolve quite logically from earlier technological generations. Size diminishes, speed increases and capacity expands. but this is hardly revolutionary. Almost all developments today are just further refinements of what was there already. 4

Utopian versus dystopian perspectives n The Utopian Perspective u This scenario couches its support for the deployment of ICTs in such terms as new civilization, information revolution or knowledge society, and thus subscribes to theory of historical discontinuity discussed above. u An array of positive developments are associated with the emerging information age. u New social values will evolve, new social relations will develop, and widespread access to the crucial resource known as information will bring the zero sum society to a definitive end. 5

The Utopian Perspective n The scenario forecasts radical changes in economics, politics and culture. u Economy - ICTs will expand productivity and improve employment opportunities, and will also upgrade the quality of work in many occupations. Moreover, they will offer a great many opportunities for small-scale, independent and decentralized forms of production. u Politics - decentralized and increased access to unprecedented volumes of information will improve the democratic process, and all people will ultimately be empowered to participate in public decisionmaking. u Culture - new and creative lifestyles will emerge, as well as vastly increased opportunities for different cultures to meet and understand each other. New virtual communities will be created that easily transcend all the traditional borderlines and barriers of age, gender, race and religion. 6

The Dystopian Perspective n Critical analysts reject the idea of discontinuity and stress the likelihood that ICT deployment will simply reinforce historical trends toward socio-economic disparities, inequality in political power and gaps between knowledge élites and the knowledge-disenfranchised. u Economic level - forecasts a perpetuation of the capitalist mode of production, with a further refinement of managerial control over production processes. In most countries, it foresees massive job displacement and deskilling. u Politics - a pseudo-democracy will emerge, allowing people to participate in marginal decisions only. ICTs will enable governments to exercise surveillance over their citizens more effectively than before. The proliferation of ICTs in the home will individualize information consumption to a degree that makes the formation of a democratic, public opinion no more than an illusion u cultural developments will be characterized by the play of antagonistic tendencies: one toward a forceful cultural globalization. (homogenizing all ways of life in the mould of global ‘Mc. Donaldization’), and another toward an aggressive cultural ‘tribalization’ (fragmenting cultural communities into fundamentalist cells with little or no understanding of different tribes). 7

Utopian versus Dystopian Perspectives n n n The debate between utopians and dystopians is not very helpful in designing policies and programmes that are intended to realize the development potential of digital technologies. The most important flaw in both perspectives is their failure to recognize the fundamental impossibility of foreseeing the future social and economic implications of technological innovations. Since there are no valid scientific instruments to predict future social impact, it is necessary to make social choices about the future under conditions of uncertainty 8

Different Views About ICTs and Their Impacts 9

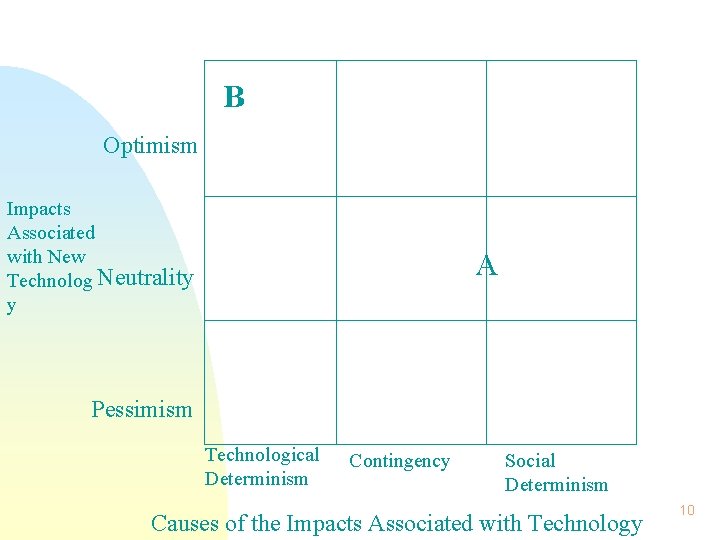

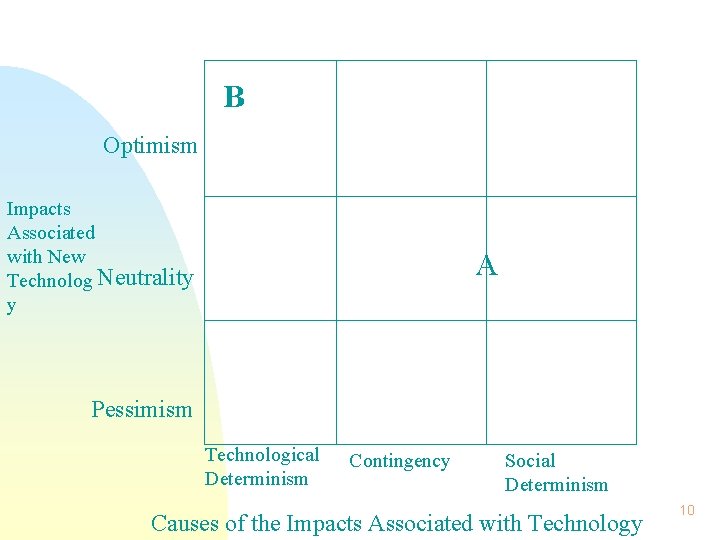

B Optimism Impacts Associated with New Technolog Neutrality y A Pessimism Technological Determinism Contingency Social Determinism Causes of the Impacts Associated with Technology 10

Social Shaping of Technology (SST) n n In contrast to the technological determinism tradition that only considered the social adjustments required by technology progress, SST has posited that technological change is patterned by conditions of its creation and use rather than developing solely according to an inner technical logic (Williams & Edge, 2001). SST goes beyond the social determinism notion of perceiving technology as reflecting a single rationality such as an economic imperative. 11

SST n n The argument of SST is that technology emerges not just from a single social determinant or through the unfolding of a predetermined technical logic, but that innovation can be understood as a ‘garden of forking paths’, whereby every stage of the design and implementation involves choices (conscious or unconscious) of different technical options, with the actual options selected depending on social, as well as technical factors. These choices shape the content of artifacts and direction (or trajectory) of innovation programs, resulting in many potential technological outcomes with differing implications for society as a whole and particular groups within it (Williams & Edge, 2001). 12

SST n On innovation, unlike the linear models of innovation which conceived of innovation as involving a one-way flow of information, ideas and solutions from basic science, through research and development (R&D), to production and the diffusion of stable artifacts through the market to consumers (Williams & Edge, 1996), SST proposes an alternative ‘interactive’ model of technological development as a ‘spiraling’ rather than a linear process, where it is proposed that crucial innovations take place in the implementation and use of technology as well as at its design stage, providing important feedback that helps shape future rounds of technological change. 13

SST n n SST Research on the political, economic, and social forces underlying the developments of new technology policy has highlighted the fact that the creation of a new technology often involves the building of a ‘social-technical constituency, ’ (Molina, 1989) which refers to the alliances of individuals and organizations involved – such as suppliers firms, technologists, and potential users – with their technical knowledge and other resources, with the values and interests of participants in its constituency underpinning the shape of a new technology (Williams & Edge, 2001). E. g. IT Revolution of the 1970 s in the Silicon Valley 14

SST Example n n The 1970 s Silicon Valley IT Revolution Castells (2002) brings out the context of the revolution where he says that the revolution: u though not coming out of any pre-determined necessity and hence technologically induced rather than being socially determined came into existence as a system under the influence of various institutional, economic and cultural factors, and upon coming into existence its development and applications and ultimately its content, was decisively shaped by the historical context into which it expanded …. . it can be said that the information technology revolution was culturally, historically and spatially contingent on a very specific set of circumstances whose characteristics earmarked its future evolution. 15

SST Example u u u Of importance also – according Castells – is the broader institutional and societal context including factors like market dynamics, cultural influences, legislation, and public policy. Further, Castells brings out the fact that the Information Technology revolution helped to bring together the milieux of innovations where discoveries and applications would interact in a recurrent process of trial and error, of learning and doing, and these mileux required the spatial concentrations of research centres, higher-education institutions, advanced-technology companies, a network of ancillary supplies of goods and services, and business networks of venture capital to finance start-ups. Further, knowledge, investment and talent was attracted from around the world 16

Failed Innovations n n Dutton (2001) describes the failure of AT&T’s Picturephone, commercialized in the late 1960 s, with a forecast that by 1980, it would make up to 1 percent of all domestic and 3 per cent of all business phones in the US. The phone, which was designed to transmit and receive sound plus black and white images, had to be abandoned in 1973 after investing between $ 130 million and $ 500 million. Other examples include the Warner-Amex thirty-channel interactive cable televised QUBE system in Columbus Ohio introduced in 1977. This Program-on-Demand system closed in 1984. 17

Failed Innovations n n The other is the Highly Interactive-Optical Visual Information Systems (HI-OVIS) introduced in Japan from 1978 to 1986. The system experimented with interactive TV, video conferencing, request video, electronic shopping, character and still picture information services and news. France Telecom’s Biarritz experiment of fibre-optic network providing voice, video and data services via multi-media terminals had to be discontinued due to disappointing subscriber use. 18

Failed Innovations n n All these ‘experiments’ failed because they were innovations based on a techno-centric vision for the forecasts rather than being user needs-driven innovations. Dutton (2001: 94) further points out the fact that ‘the success of the personal computer beyond its initial hobbyist ‘nerd’ market was based on ‘killer apps’ such as word processing and spreadsheets, which inspired a wide range of people to buy their own PC. ’ 19

Technology as Cultural Artifacts n n One of the views that emphasizes the importance of ‘social dimensions’ of technology looks at technology as embodying the various social factors involved in its design and development, such that the resulting material form of the technology reflects the social circumstances of development. In this view, technology can be thought of as ‘congealed social relations’ – a frozen assemblage of the practices, assumptions, beliefs, languages and other factors involved in its design and manufacture (Woolgar, 2001). This version suggests that the social relations which are built into the technology have consequences for subsequent usage. This sees technology as representing a kind of ‘social order, represented by linking together of sets of social relations (Latour, 1991). n 20

Technology as Cultural Artifacts n n Technology in this view is regarded as a cultural artifact or system of artifacts which provides for certain, often new, ways of acting and interrelating. According to Woolgar, 2001, this can be summarized by the slogan ‘technology is society made durable’ because it argues that a particular fixed version of social relations as the basis for action is ‘frozen in material form’ by the use of particular technology. 21

Technology as Cultural Artifacts n n In this way of looking at technology, users of a particular technology confront and respond to the social relations embodied within it, such that they experience the effects of the material artifact as far more immediately compelling than any mere interpretation or description. An illustration is the use of software; whereas it is possible to use it in ways other than those which the designer had in mind, it would be very costly (since alternative sets of material and human resources will be needed to counter and offset the effects of technology) and / or socially sanctioned. 22

Technology as Cultural Artifacts n n n To understand the impact of technology on a user, it would help to look at the way the user will respond to the social relations embodied within it. To be able to design software, the designers have a preconception of the user in terms of the user requirements, levels of skill and experience. These preconceptions may be gotten from the organization’s culture (which obviously is affected by the relations between the producer’s and the user’s organizations) or they may be gotten say from market analysis and research. 23

Technology as Cultural Artifacts n n In the process of developing software, it is possible to each of the different stakeholders (e. g. managers, systems analysts, designers) having a different view about the user. During the lifecycle of the ICT product (right from the inception up to the after-sales support) it is possible to have a struggle between these different stakeholders over the ‘true character’ of the user. 24

Technology as Cultural Artifacts n n Configuring the user therefore involves identifying the user, definition of the user and a series of decisions – in requirements gathering and definition, the design and the construction – which both enable and constrain the actions of the users. The dominant producer’s (analyst and designer) preconceptions of the user become embodied in the final product. When the technology is finally deployed, the actual users are effectively confronted by, and asked to engage with ‘configured users’ – the concretized preconceptions about themselves (Woolgar, 1993). 25

Technology as Cultural Artifacts n The emphasis of this perspective on the social relations between products and consumers provides a way to understand the ‘impact’ of technology; it enables the ‘impact’, ‘success’, ‘value’, and other outcomes of the use of a technology to be understood in terms of the extent to which users are willing or able to conform to – and in terms of the costs involved in challenging – the configured preconceptions embodied in the technology (Woolgar, 2001). 26

Technology as Cultural Artifacts n n In thinking about how ICTs can be utilized to for a certain purpose (say development), there is a temptation to concentrate on the characteristics of ICTs that can rend themselves to enabling development. The argument would therefore lean more on how ICTs can be used to enable development. From the arguments presented above, it is important to not only consider the community of social relations built into the technology but also the possible interpretations of the technology by the user. 27

Technology as Cultural Artifacts n n ICTs already have certain preferred meanings written into them by the producers. The ICTs will only be successful among the poor if the poor can be able to get the preferred readings. The question must be asked if the poor, more so the poor in developing countries (that are mostly found in rural areas and poor urban neighborhoods), are able to get the readings. 28

Technology as Cultural Artifacts n n The producers of the technology will have a certain conception of the ‘poor user’ which is ‘written’ into the technology. How this actual ‘poor’ user confronts and engages the ‘user’ already built into the technology and how close this ‘user’ is to the actual user will determine the success of the technology. 29

n THE END 30