PELVIC PAIN Introduction Acute and chronic lower abdominal

PELVIC PAIN Introduction Acute and chronic lower abdominal pain are common complaints in office and emergency room settings. They vary dramatically by definition, predominant etiologies, and neurophysiology. The mechanisms underlying the perception of pain are not yet fully defined, but appear to involve interactions between neurologic, psychological, immunologic, and endocrine factors. Pain may be considered visceral or somatic depending on the type of afferent nerve fibers involved. Additionally, pain may be described by the neurophysiologic steps that produce it and can be defined as inflammatory or neuropathic.

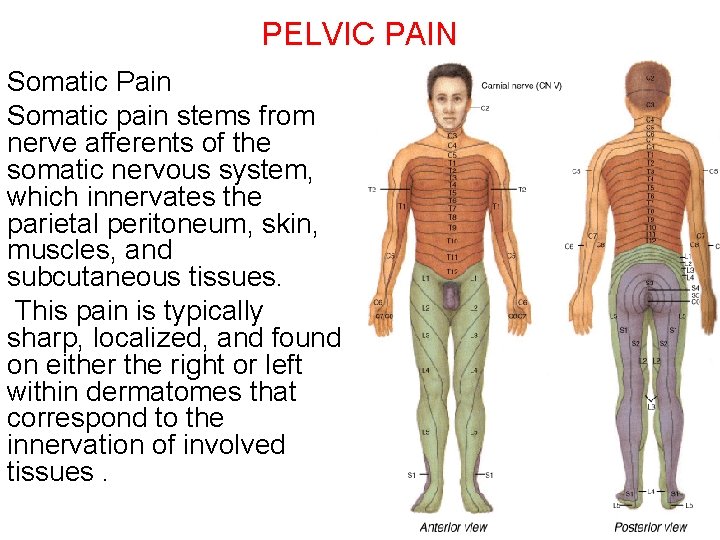

PELVIC PAIN Somatic Pain Somatic pain stems from nerve afferents of the somatic nervous system, which innervates the parietal peritoneum, skin, muscles, and subcutaneous tissues. This pain is typically sharp, localized, and found on either the right or left within dermatomes that correspond to the innervation of involved tissues.

PELVIC PAIN Visceral Pain Visceral pain stems from afferent fibers of the autonomic nervous system, which transmit information from the viscera and visceral peritoneum. Noxious stimuli typically involve stretching, distension, ischemia, or spasm of abdominal organs. The visceral afferent fibers that transfer these stimuli are sparse, and the resulting diffuse sensory input leads to pain that is often described as a generalized, dull ache. Visceral pain often localizes to the midline because visceral innervation of abdominal organs is typically bilateral. Visceral afferents follow a segmental distribution, and visceral pain is typically localized by the brain's sensory cortex to an approximate spinal cord level.

PELVIC PAIN Hindgut organs, such as the colon and intraperitoneal portions of the genitourinary tract, cause pain in the suprapubic or hypogastric area (Gallagher, 2004). Inflammatory Pain If tissues are injured, then inflammation typically follows. Commonly during an inflammatory process, sensitizing mediators are released into affected tissues and lower the conduction threshold of nociceptors in these tissues. This is termed peripheral sensitization

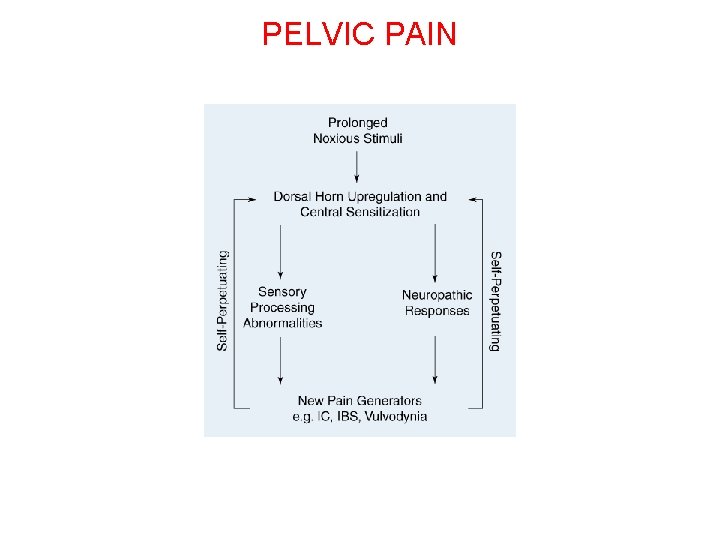

PELVIC PAIN Neuropathic Pain In some individuals, sustained noxious stimuli can lead to persistent central sensitization and to a loss of neuronal inhibition that is permanent. As a result, a decreased threshold to painful stimuli remains despite resolution of the inciting stimuli (Butrick, 2003). This persistence characterizes neuropathic pain, which is felt to underlie many chronic pain syndromes. The concept of neuropathic pain helps explain in part why many with chronic pain have pain disproportionately greater to the amount of co-existent disease found.

PELVIC PAIN

PELVIC PAIN Acute Pain Acute lower abdominal and pelvic pain are common complaints. The definition of these varies based on duration, but in general, discomfort is present less than 7 days. The sources of acute lower abdominal and pelvic pain are extensive and a thorough history and physical examination can aid in narrowing the list

PELVIC PAIN Etiologies of Acute Lower Abdominal and Pelvic Pain Periumbilical Appendicitis (early) Small bowel obstruction Gastroenteritis Mesenteric ischemia Abdominal aortic aneurysm rupture Abdominal aortic aneurysm dissection

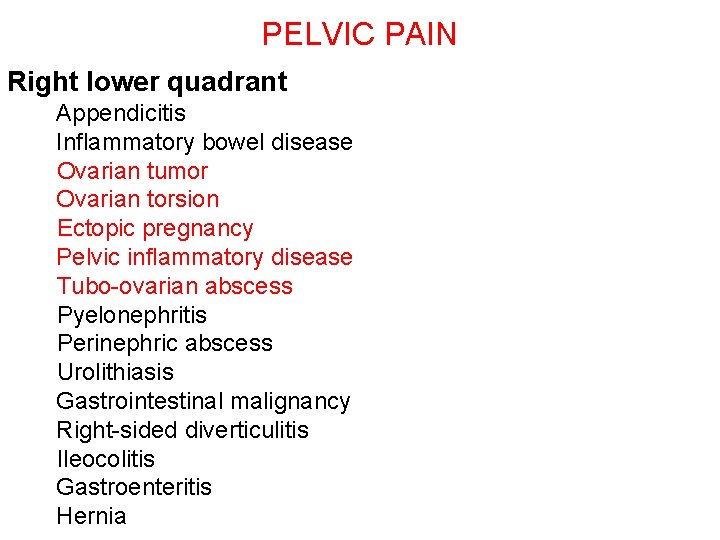

PELVIC PAIN Right lower quadrant Appendicitis Inflammatory bowel disease Ovarian tumor Ovarian torsion Ectopic pregnancy Pelvic inflammatory disease Tubo-ovarian abscess Pyelonephritis Perinephric abscess Urolithiasis Gastrointestinal malignancy Right-sided diverticulitis Ileocolitis Gastroenteritis Hernia

PELVIC PAIN Suprapubic Irritable bowel disease Ovarian tumor Ovarian torsion Ectopic pregnancy Pelvic inflammatory disease Tubo-ovarian abscess Dysmenorrhea Colonic disease Diverticulitis Cystitis Nephrolithiasis

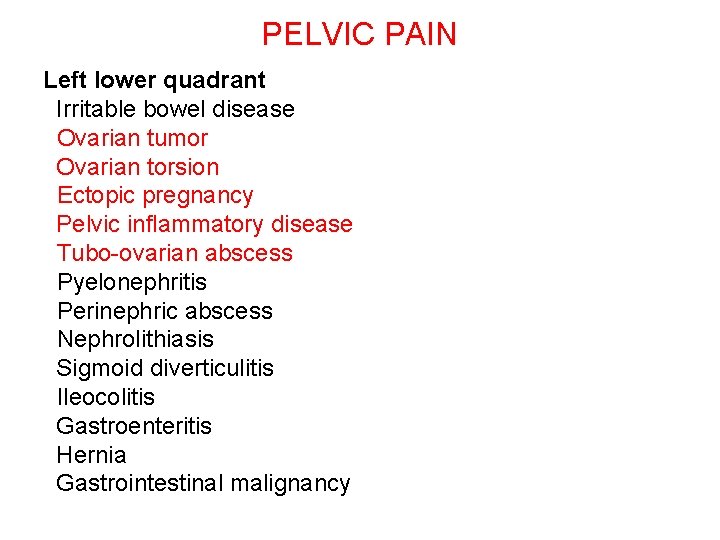

PELVIC PAIN Left lower quadrant Irritable bowel disease Ovarian tumor Ovarian torsion Ectopic pregnancy Pelvic inflammatory disease Tubo-ovarian abscess Pyelonephritis Perinephric abscess Nephrolithiasis Sigmoid diverticulitis Ileocolitis Gastroenteritis Hernia Gastrointestinal malignancy

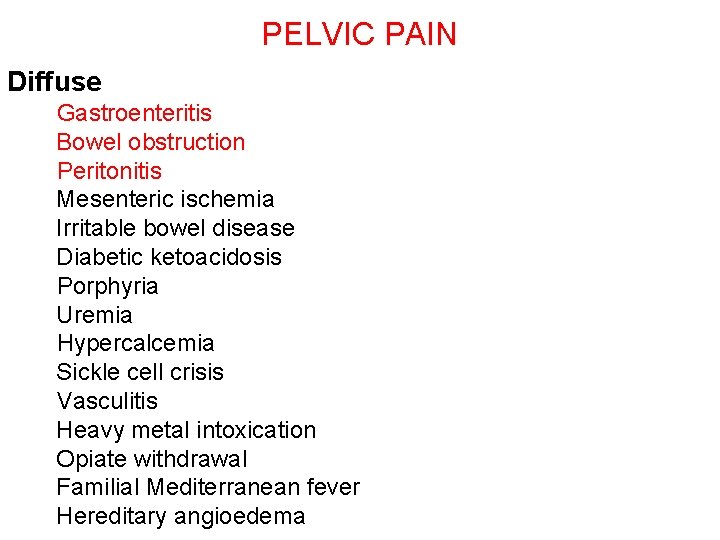

PELVIC PAIN Diffuse Gastroenteritis Bowel obstruction Peritonitis Mesenteric ischemia Irritable bowel disease Diabetic ketoacidosis Porphyria Uremia Hypercalcemia Sickle cell crisis Vasculitis Heavy metal intoxication Opiate withdrawal Familial Mediterranean fever Hereditary angioedema

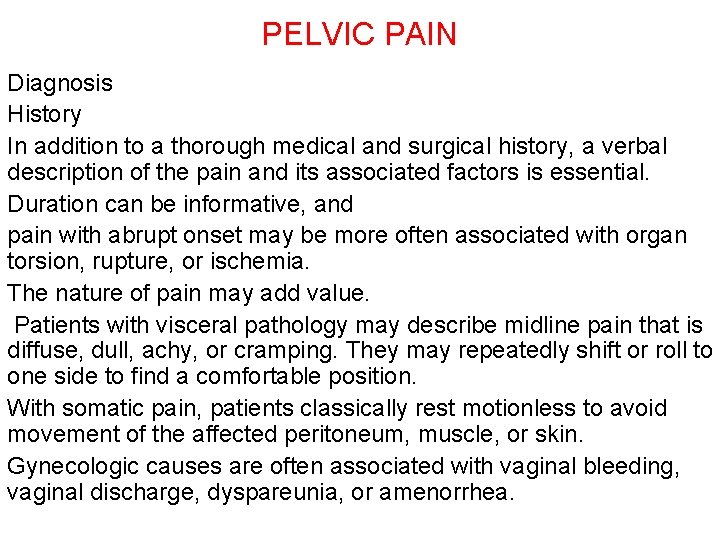

PELVIC PAIN Diagnosis History In addition to a thorough medical and surgical history, a verbal description of the pain and its associated factors is essential. Duration can be informative, and pain with abrupt onset may be more often associated with organ torsion, rupture, or ischemia. The nature of pain may add value. Patients with visceral pathology may describe midline pain that is diffuse, dull, achy, or cramping. They may repeatedly shift or roll to one side to find a comfortable position. With somatic pain, patients classically rest motionless to avoid movement of the affected peritoneum, muscle, or skin. Gynecologic causes are often associated with vaginal bleeding, vaginal discharge, dyspareunia, or amenorrhea.

PELVIC PAIN if vomiting is noted prior to pain or concurrent with it, a surgical abdomen is less likely (Miller, 2006). well-localized pain or tenderness persisting for longer than 6 hours and unrelieved by analgesics, has an increased likelihood of acute peritoneal pathology.

PELVIC PAIN Physical Examination Vital Signs Vital signs are assessed, and elevated temperature, tachycardia, and hypotension the risk for intra-abdominal pathology increases with their presence. Constant low-grade fever is common in inflammatory conditions such as diverticulitis and appendicitis, and higher temperatures may be seen with pelvic inflammatory disease (PID), advanced peritonitis, or pyelonephritis. Pulse and blood pressure evaluation should assess orthostatic changes if intravascular hypovolemia is suspected. A pulse increase of 30 beats per minute or a systolic blood pressure drop of 20 mm Hg or both, between lying and standing after 1 minute, is often reflective of hypovolemia

PELVIC PAIN Abdominal Examination Visual inspection of the abdomen focuses on prior surgical scars, which may increase the possibility of bowel obstruction from postoperative adhesions or incisional hernia. Abdominal distension may be seen with bowel obstruction, perforation, or ascites. After inspection, auscultation of the abdomen may identify hyperactive or high-pitched bowel sounds characteristic of bowel obstruction. Palpation of the abdomen should systematically explore each abdominal quadrant and begin away from the area of indicated pain. Peritoneal irritation is suggested by rebound tenderness or by abdominal rigidity due to involuntary guarding or reflex spasm of the abdominal muscles.

PELVIC PAIN Pelvic Examination Pelvic examination should be performed in reproductiveaged women, as gynecologic pathology and complications of pregnancy are a common cause of pain in this age group. In geriatric and pediatric patients may be based on clinical information. Purulent vaginal discharge or cervicitis may reflect PID. Vaginal bleeding may stem from pregnancy complications, benign or malignant reproductive tract neoplasia, or acute vaginal trauma. Pregnancy, leiomyomas, and adenomyosis are common causes of uterine enlargement. Cervical motion tenderness is commonly associated with peritoneal irritation and may be seen with PID, appendicitis, diverticulitis, and intra-abdominal bleeding.

PELVIC PAIN A tender adnexal mass may reflect ectopic pregnancy, tubo-ovarian abscess, or ovarian cyst with torsion, hemorrhage, or rupture. Rectal examination can additional information regarding the source and size of pelvic masses as well as the possibility of colorectal pathologies In emergency room settings, women with acute pain may experience waits between an initial assessment and laboratory testing, specialist consultation, or radiologic imaging. For these patients, recent literature supports early administration of analgesia. Fears that analgesia will mask patient symptoms and hinder accurate diagnosis have not been supported.

PELVIC PAIN Laboratory Testing In women with acute abdominal pain, complications of pregnancy are common. Thus, either urine or serum -h. CG testing is recommended in those of reproductive age without a history of hysterectomy. Complete blood count (CBC) can aid in assessment of hemorrhage, both vaginal and intra-abdominal, and assess the possibility of infection. Urinalysis may be used to evaluate possible urolithiasis or cystitis. In addition, microscopic evaluation and culture of vaginal discharge can add support to clinically suspected cases of PID.

PELVIC PAIN Radiologic Imaging In women with acute pelvic pain, sonography is commonly used. In most cases, a transvaginal approach offers superior resolution of reproductive organs. If pelvic organs are significantly large and lie outside the true pelvis, transabdominal sonography may be necessary to image entire structures. In cases in which sonographic findings are equivocal or nondiagnostic, computed tomography (CT) is widely used for its ability to detect a great variety of bowel, reproductive tract, and urinary disorders. Computed tomography has superior sensitivity compared with abdominal radiography.

PELVIC PAIN Laparoscopy Operative laparoscopy is the primary treatment for appendectomy, ovarian torsion, and for ruptured tubal ectopic pregnancy or ruptured ovarian cyst associated with symptomatic hemorrhage. Diagnostic laparoscopy may be useful if no pathology can be identified by conventional diagnostics. In stable patients with acute abdominal pain, noninvasive testing is typically fully exhausted before considering this approach (Sauerland, 2006).

PELVIC PAIN Chronic pelvic Pain Persistent pain symptoms in women may take several forms and include dysmenorrhea, dyspareunia, chronic pelvic pain (CPP), musculoskeletal pain, intestinal cramping, or dysuria. A woman with chronic pain may have more than one cause of pain and overlapping symptoms. A comprehensive evaluation of multiple organ systems and psychological state is essential for complete treatment.

PELVIC PAIN Gynecologic Extrauterine Adhesions Adnexal cysts Chronic ectopic pregnancy Chlamydial endometritis OR salpingitis Endometriosis Endosalpingiosis Neoplasia of the genital tract Ovarian retention syndrome (residual ovary syndrome) Ovarian remnant syndrome Ovulatory pain

PELVIC PAIN Uterine Adenomyosis Atypical dysmenorrhea or ovulatory pain Cervical stenosis Chronic endometritis Endometrial or endocervical polyps Intrauterine contraceptive device Leiomyomas

PELVIC PAIN Chronic pelvic Pain Define as *noncyclic pain that persists for 6 or more months; *localizes to the pelvis, infraumbilical anterior abdominal wall, or lumbosacral back or buttocks; *and leads to degrees of functional disability (American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, 2004). Etiology Causes of chronic pelvic pain fall within a broad spectrum, but endometriosis, symptomatic leiomyomas, interstitial cystitis, and irritable bowel syndrome are commonly diagnosed.

PELVIC PAIN History More than with many other gynecologic complaints, a detailed history and physical examination is integral to diagnosis. A pelvic pain questionnaire can be used initially to obtain information. What is the quality or character of your pain? Do you have pain with your periods? Does your pain worsen with menses or just before menses? Is there any cyclic pattern to your pain? Is it the same 24 hours a day, 7 days a week? Is your pain constant or intermittent? When and how did your pain start and how has it changed? Did pain start initially as menstrual cramps (dysmenorrhea)? What makes your pain better? What makes your pain worse?

PELVIC PAIN Obstetric History Pregnancy and delivery can be traumatic to neuromuscular structures and have been linked with pelvic organ prolapse, pelvic floor muscle myofascial pain syndromes, and symphyseal or sacroiliac joint pain. Injury to the ilioinguinal or iliohypogastric nerves during Pfannenstiel incision for cesarean delivery may lead to lower abdominal wall pain even years after the initial injury (Whiteside, 2003). In a nulliparous woman with infertility, pain may stem from endometriosis, pelvic adhesions, or pelvic inflammatory disease.

PELVIC PAIN Surgical History Prior abdominal surgery increases a woman's risk for pelvic adhesions, especially if infection, bleeding, or large areas of denuded peritoneal surfaces were involved. In addition, certain disorders persist or commonly recur, and thus information regarding prior surgeries for endometriosis, adhesive disease, or malignancy should be sought. If a woman notes the combination of dysmenorrhea, CPP, and dyspareunia, the risk of finding endometriosis at laparoscopy is threefold that in women with no symptoms (Fedele, 1992). Psychosocial History There is a significant association between physical, emotional, or sexual abuse and chronic pelvic pain.

PELVIC PAIN Physical examination Stance and gait Supine lateral Sitting Lithotomy

PELVIC PAIN Testing Laboratory Evaluation For women with chronic pelvic pain, diagnostic testing may add valuable information. Results from urinalysis and urine culture may indicate urinary tract stones, malignancy, or recurrent infection as sources of pain. Thyroid disease can affect physiologic functioning and may be found in those with bowel or bladder symptoms. TSH levels are commonly assayed. Diabetes can lead to neuropathy, and screening may be completed with urinalysis or serum evaluation. Radiologic Imaging and Endoscopy These modalities may be informative, and of these, transvaginal sonography is widely used by gynecologists to evaluate chronic pelvic pain. Sonography of the pelvic organs may reveal endometriomas, leiomyomas, ovarian cysts, and other structural lesions.

PELVIC PAIN One newer laparoscopic approach to CPP is performed under local anesthesia with the patient conscious and available for questioning regarding sites of pain (Howard, 2000; Swanton, 2006). Termed conscious pain mapping, this technique has resulted in improved postoperative pain scores but its clinical use to date has been limited.

PELVIC PAIN Treatment In many women with CPP, an identifying source is found and treatment is dictated by the diagnosis. In other cases, pathology may not be identified and treatment is directed toward dominant symptoms. Analgesics Treatment of pain typically begins with oral analgesics such as acetaminophen or nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs). These are particularly helpful if inflammatory states underlie the pain. If satisfactory relief is not achieved, then a mild opioid such as codeine or hydrocodone may be added to this regimen. Opioids are most effective and least addictive if given on a scheduled basis and at doses that adequately relieve pain. If pain persists, stronger opioids such as morphine, methadone, fentanyl, oxycodone, and hydromorphone can replace milder ones. Close and regular surveillance is essential.

PELVIC PAIN Hormonal Suppression Endometriosis is a common disorder found in women with CPP. Hormonal suppression may be considered, especially in those with co-existent dysmenorrhea or dyspareunia and who lack dominant bladder or bowel symptoms. Combination oral contraceptives, progestins, gonadotropin-releasing hormone (Gn. RH) agonists, and certain androgens have proven effective.

PELVIC PAIN Antidepressants and Anticonvulsants For many, CPP represents neuropathic pain, and therapy has been extrapolated from treatment of such pain in other disorders. Tricyclic antidepressants have repeatedly been shown to reduce neuropathic pain independent of their antidepressant effects (Saarto, 2005). Antidepressants are a logical choice, as clinically significant depression is commonly comorbid with pain. Amitriptyline (Elavil) and its metabolite nortriptyline (Pamelor) have the best documented efficacy in the treatment of neuropathic and non-neuropathic pain syndromes.

PELVIC PAIN Polypharmacy Combining drugs with different sites or mechanisms of action may often increase pain relief. For example, an NSAID and an opioid may be partnered, especially in conditions in which inflammation is a dominant component. If muscle spasm underlies pain, then pairing a tranquilizer or a muscle relaxant with an opioid or an NSAID may improve results

PELVIC PAIN Surgery Neurolysis Nerve destruction, termed neurolysis, involves nerve transection or injection of a neurotoxic chemical. Nerve transection cuts a specific peripheral nerve or may be performed on an entire nerve plexus. Presacral neurectomy (PSN) describes interruption of somatic pain fibers from the uterus that course with the primarily sympathetic superior hypogastric plexus. This procedure is performed by incising the pelvic peritoneum over the sacrum and then identifying and transecting the sacral nerve plexus. Alternatively, laparoscopic uterosacral nerve ablation (LUNA) involves the destruction of the uterine nerve fibers that pass to the uterus through the uterosacral ligament. Most surgeons destroy approximately 2 cm of uterosacral ligament near its attachment to the uterus (Lifford, 2002).

PELVIC PAIN Hysterectomy For many women with CPP, especially that is related to organic pathologies, hysterectomy is effective in resolving pain and improving quality of life (Kjerulff, 2000; Stovall, 1990). For others, hysterectomy may fail to relieve CPP. This result may follow more commonly in those who are younger than 30 years or those who have depression, psychological problems, or no identifiable pelvic pathology (Gunter, 2003). Almost 40 percent of women with no identified pelvic pathology will have persistent pain post-hysterectomy

PELVIC PAIN

PELVIC PAIN

PELVIC PAIN

PELVIC PAIN

PELVIC PAIN

PELVIC PAIN

PELVIC PAIN

PELVIC PAIN

PELVIC PAIN

PELVIC PAIN

PELVIC PAIN

PELVIC PAIN

PELVIC PAIN

PELVIC PAIN

PELVIC PAIN

PELVIC PAIN

PELVIC PAIN

PELVIC PAIN

PELVIC PAIN

PELVIC PAIN

PELVIC PAIN

PELVIC PAIN

PELVIC PAIN

PELVIC PAIN

PELVIC PAIN

PELVIC PAIN

PELVIC PAIN

PELVIC PAIN

PELVIC PAIN

PELVIC PAIN

PELVIC PAIN

PELVIC PAIN

PELVIC PAIN

PELVIC PAIN

PELVIC PAIN

PELVIC PAIN

PELVIC PAIN

PELVIC PAIN

PELVIC PAIN

PELVIC PAIN

PELVIC PAIN

PELVIC PAIN

PELVIC PAIN

PELVIC PAIN

PELVIC PAIN

PELVIC PAIN

PELVIC PAIN

PELVIC PAIN

PELVIC PAIN

PELVIC PAIN

PELVIC PAIN

PELVIC PAIN

- Slides: 89