Pediatric Intensivists Perspectives on Nudging Aliza Olive MD

- Slides: 1

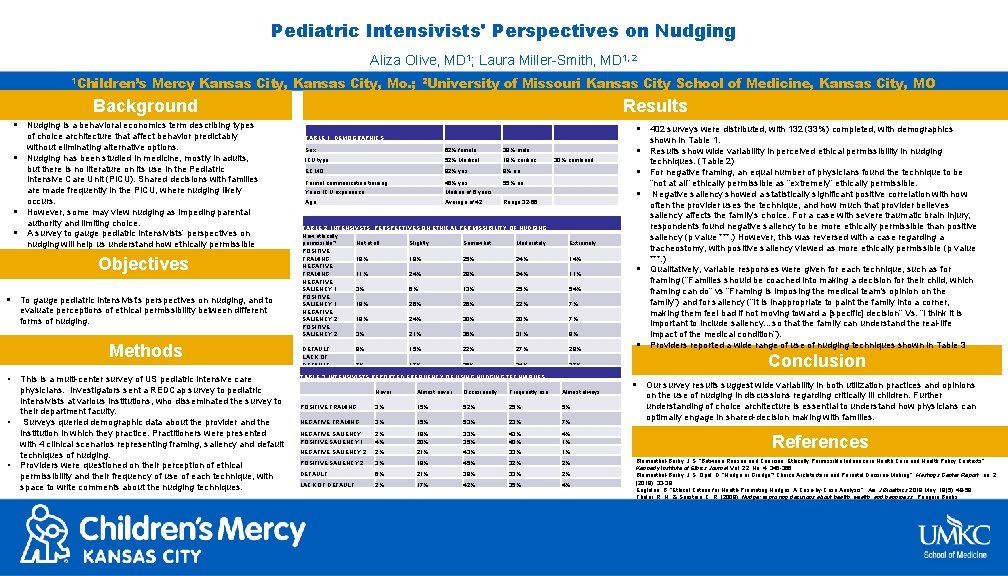

Pediatric Intensivists' Perspectives on Nudging Aliza Olive, MD 1; Laura Miller-Smith, MD 1, 2 1 Children’s Mercy Kansas City, Mo. ; 2 University of Missouri Kansas City School of Medicine, Kansas City, MO Background Results § Nudging is a behavioral economics term describing types § § § of choice architecture that affect behavior predictably without eliminating alternative options. Nudging has been studied in medicine, mostly in adults, but there is no literature on its use in the Pediatric Intensive Care Unit (PICU). Shared decisions with families are made frequently in the PICU, where nudging likely occurs. However, some may view nudging as impeding parental authority and limiting choice. A survey to gauge pediatric intensivists’ perspectives on nudging will help us understand how ethically permissible providers believe these techniques to be. Objectives § To gauge pediatric intensivist’s perspectives on nudging, and to evaluate perceptions of ethical permissibility between different forms of nudging. Methods • • • This is a multi-center survey of US pediatric intensive care physicians. Investigators sent a REDCap survey to pediatric intensivists at various institutions, who disseminated the survey to their department faculty. Surveys queried demographic data about the provider and the institution in which they practice. Practitioners were presented with 4 clinical scenarios representing framing, saliency and default techniques of nudging. Providers were questioned on their perception of ethical permissibility and their frequency of use of each technique, with space to write comments about the nudging techniques. § 402 surveys were distributed, with 132 (33%) completed, with demographics shown in Table 1. TABLE 1: DEMOGRAPHICS Sex 62% female 38% male ICU type 52% Medical 18% cardiac ECMO 92% yes 8% no Formal communication training 45% yes 55% no Years ICU experience Median of 6 years Age Average of 42 techniques. (Table 2) 30% combined § For negative framing, an equal number of physicians found the technique to be § Range 32 -66 TABLE 2: INTENSIVSTS PERSPECTIVES ON ETHICAL PERMISSIBILITY OF NUDGING How ethically permissible? Not at all Slightly Somewhat Moderately POSITIVE FRAMING 18% 19% 25% 24% NEGATIVE FRAMING 11% 24% 29% 24% NEGATIVE SALIENCY 1 3% 6% 13% 25% POSITIVE SALIENCY 1 19% 26% 22% NEGATIVE SALIENCY 2 18% 24% 30% 20% POSITIVE SALIENCY 2 3% 21% 36% 31% DEFAULT LACK OF DEFAULT § Results show wide variability in perceived ethical permissibility in nudging Extremely 14% 11% § 54% 7% 7% 9% 9% 15% 22% 27% 28% 7% 17% 26% 24% 27% TABLE 3: INTENSIVISTS REPORTED FREQUENCY OF USING NUDGING TECHNIQUES Never Almost never Occasionally Frequently use Almost always POSITIVE FRAMING 3% 15% 52% 25% 5% NEGATIVE FRAMING 3% 15% 53% 23% 7% NEGATIVE SALIENCY POSITIVE SALIENCY 1 2% 4% 18% 20% 33% 35% 43% 40% 4% 1% NEGATIVE SALIENCY 2 2% 21% 43% 33% 1% POSITIVE SALIENCY 2 3% 18% 45% 32% 2% DEFAULT 6% 21% 38% 33% 2% LACK OF DEFAULT 2% 17% 42% 35% 4% § “not at all” ethically permissible as “extremely” ethically permissible. Negative saliency showed a statistically significant positive correlation with how often the provider uses the technique, and how much that provider believes saliency affects the family’s choice. For a case with severe traumatic brain injury, respondents found negative saliency to be more ethically permissible than positive saliency (p value ***. ) However, this was reversed with a case regarding a tracheostomy, with positive saliency viewed as more ethically permissible (p value ***. ) Qualitatively, variable responses were given for each technique, such as for framing (“Families should be coached into making a decision for their child, which framing can do” vs “Framing is imposing the medical team's opinion on the family”) and for saliency (“It is inappropriate to paint the family into a corner, making them feel bad if not moving toward a [specific] decision” Vs. “I think it is important to include saliency…so that the family can understand the real-life impact of the medical condition”). Providers reported a wide range of use of nudging techniques shown in Table 3 Conclusion § Our survey results suggest wide variability in both utilization practices and opinions on the use of nudging in discussions regarding critically ill children. Further understanding of choice architecture is essential to understand how physicians can optimally engage in shared-decision making with families. References Blumenthal-Barby, J. S. “Between Reason and Coercion: Ethically Permissible Influence in Health Care and Health Policy Contexts”. Kennedy Institute of Ethics Journal Vol. 22, No. 4, 345 -366. Blumenthal-Barby, J. S, Opel, D. “Nudge or Grudge? Choice Architecture and Parental Decision-Making”. Hastings Center Report, no. 2 (2018): 33 -39. Englelen, B. “Ethical Criteria for Health-Promoting Nudges: A Case-by-Case Analysis”. Am J Bioethics 2019 May; 19(5): 48 -59. Thaler, R. H. , & Sunstein, C. R. (2009). Nudge: improving decisions about health, wealth, and happiness. Penguin Books.