Patterns for Life Moths Adaptations and Predators How

- Slides: 28

Patterns for Life Moths, Adaptations and Predators How the appearance and behaviour of moths fits their environment Laurence Cook & Michael Dockery

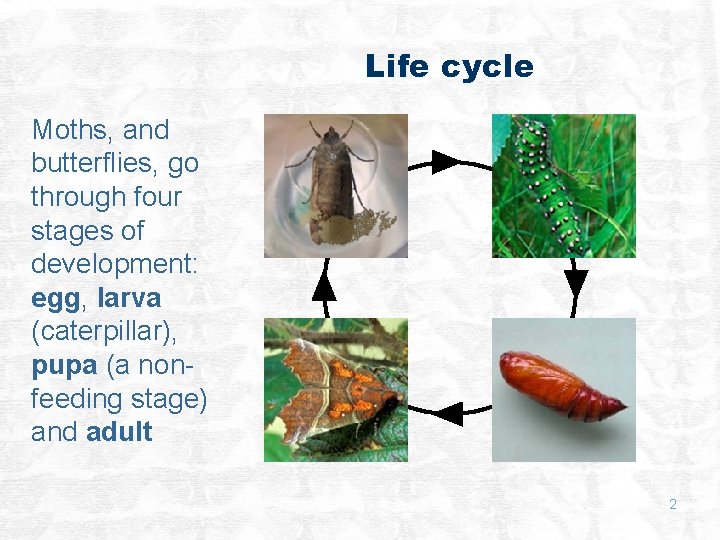

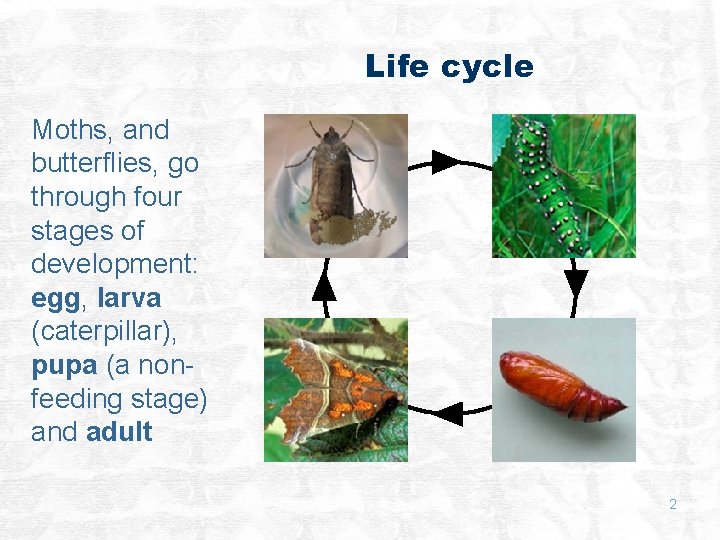

Life cycle Moths, and butterflies, go through four stages of development: egg, larva (caterpillar), pupa (a nonfeeding stage) and adult 2

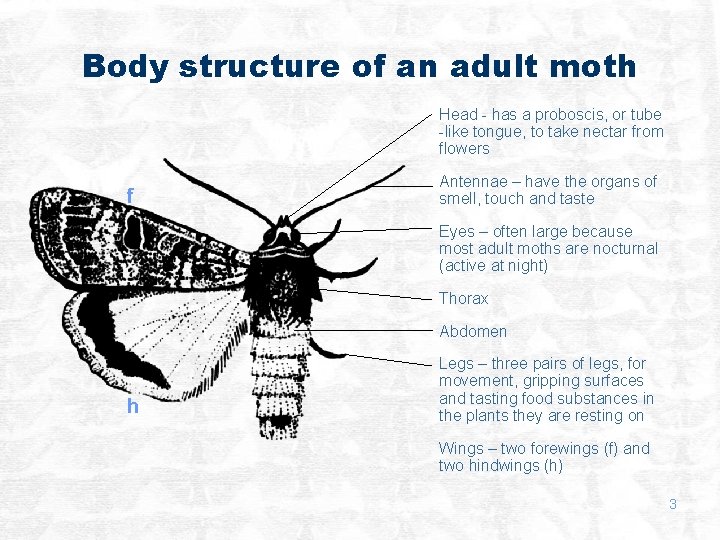

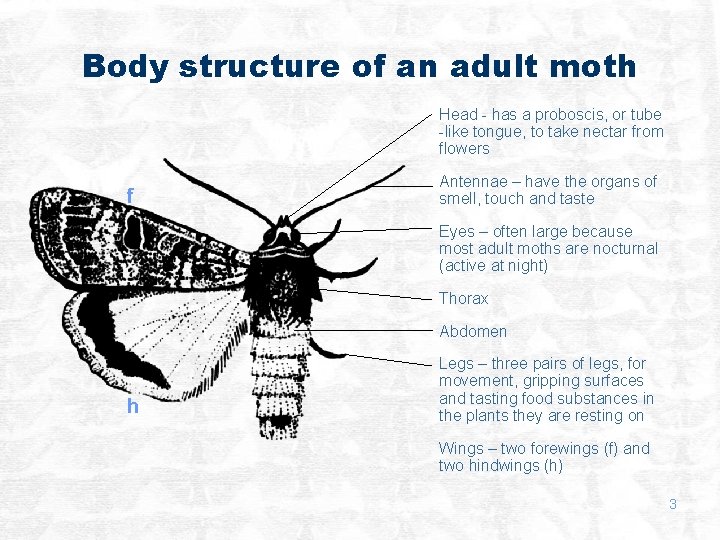

Body structure of an adult moth Head - has a proboscis, or tube -like tongue, to take nectar from flowers f Antennae – have the organs of smell, touch and taste Eyes – often large because most adult moths are nocturnal (active at night) Thorax Abdomen h Legs – three pairs of legs, for movement, gripping surfaces and tasting food substances in the plants they are resting on Wings – two forewings (f) and two hindwings (h) 3

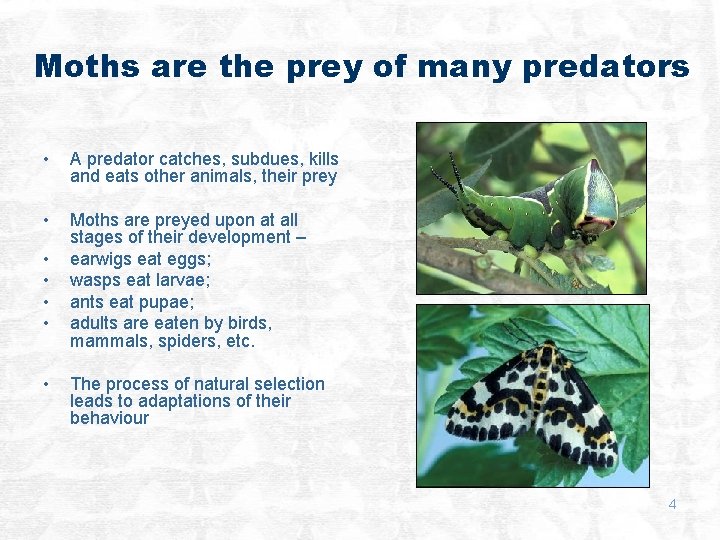

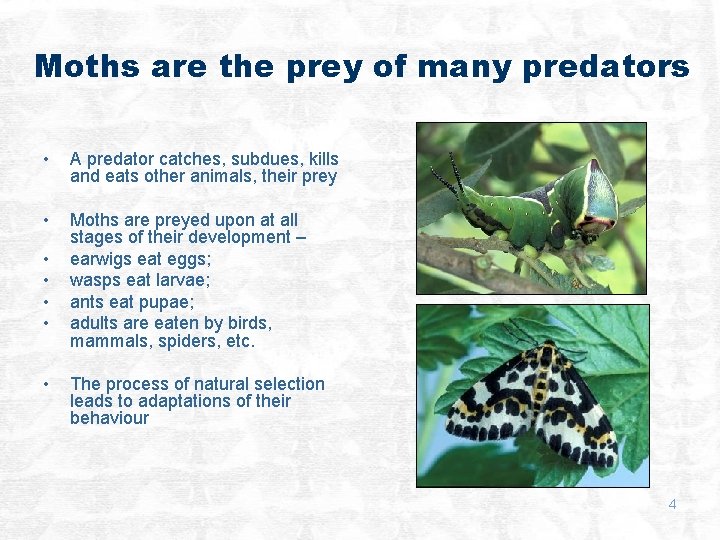

Moths are the prey of many predators • A predator catches, subdues, kills and eats other animals, their prey • Moths are preyed upon at all stages of their development – earwigs eat eggs; wasps eat larvae; ants eat pupae; adults are eaten by birds, mammals, spiders, etc. • • • The process of natural selection leads to adaptations of their behaviour 4

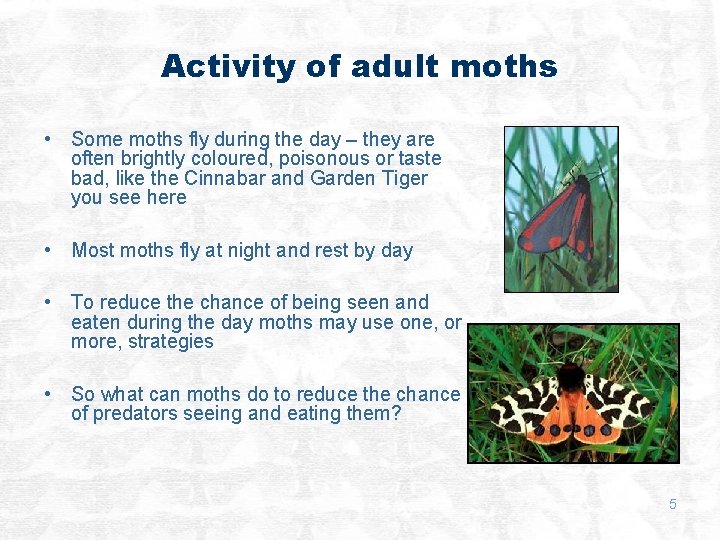

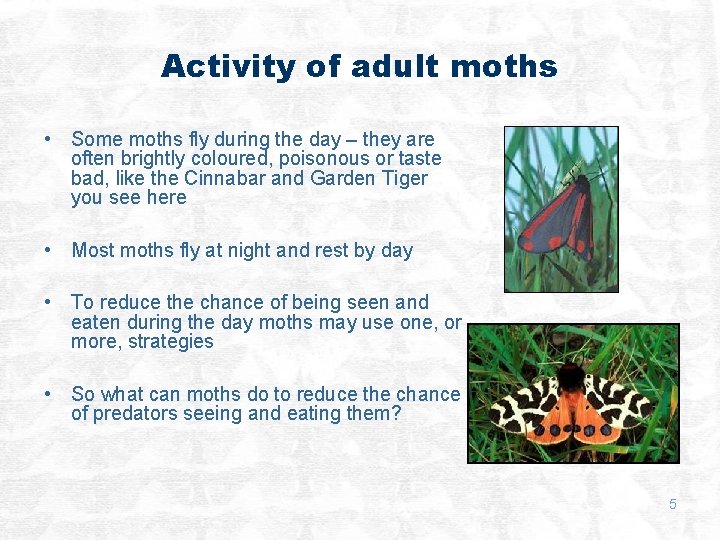

Activity of adult moths • Some moths fly during the day – they are often brightly coloured, poisonous or taste bad, like the Cinnabar and Garden Tiger you see here • Most moths fly at night and rest by day • To reduce the chance of being seen and eaten during the day moths may use one, or more, strategies • So what can moths do to reduce the chance of predators seeing and eating them? 5

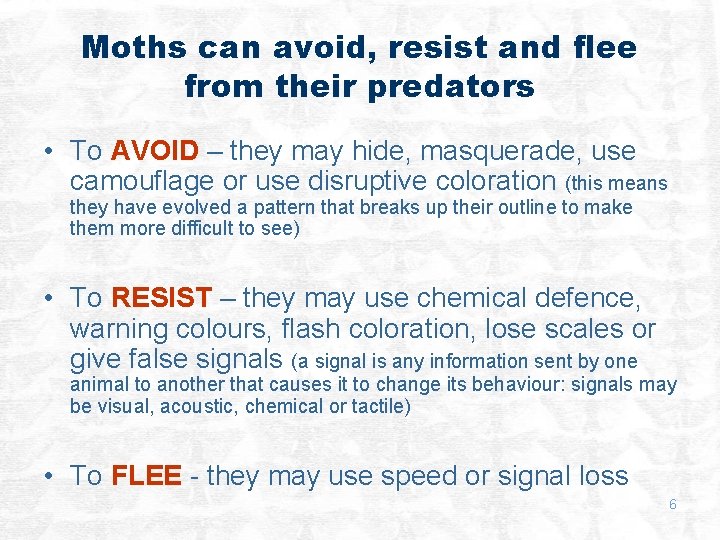

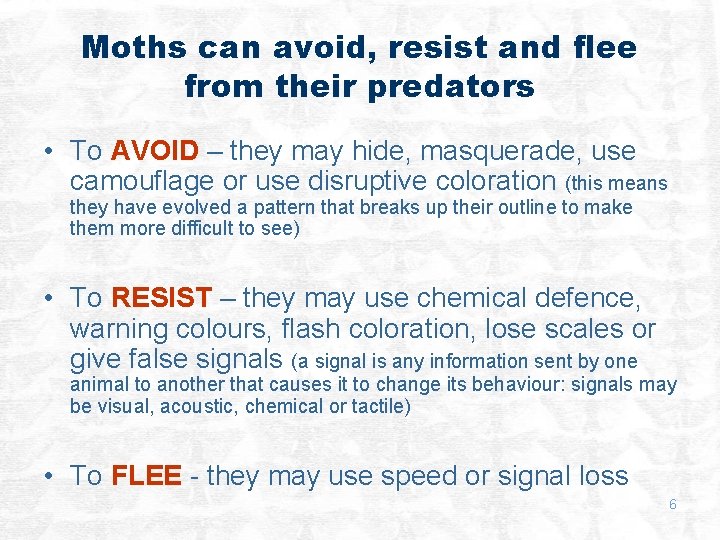

Moths can avoid, resist and flee from their predators • To AVOID – they may hide, masquerade, use camouflage or use disruptive coloration (this means they have evolved a pattern that breaks up their outline to make them more difficult to see) • To RESIST – they may use chemical defence, warning colours, flash coloration, lose scales or give false signals (a signal is any information sent by one animal to another that causes it to change its behaviour: signals may be visual, acoustic, chemical or tactile) • To FLEE - they may use speed or signal loss 6

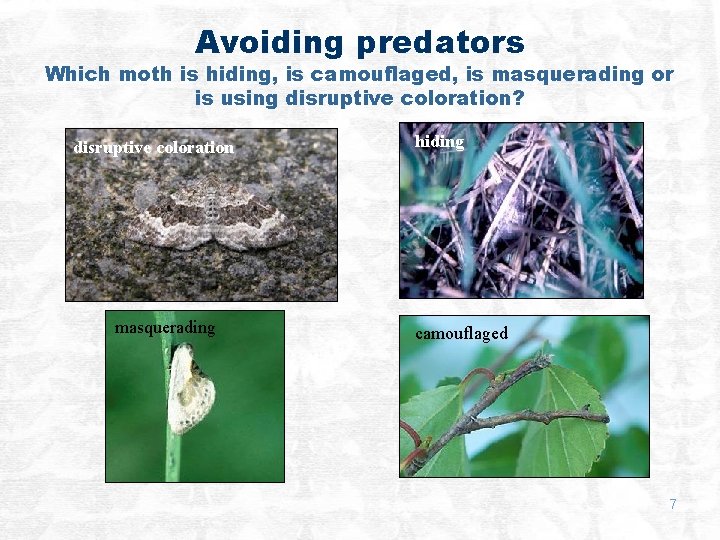

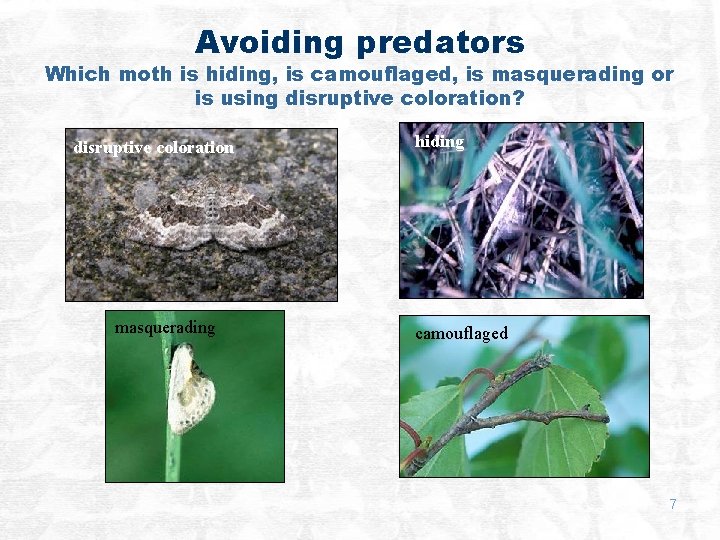

Avoiding predators Which moth is hiding, is camouflaged, is masquerading or is using disruptive coloration? disruptive coloration masquerading hiding camouflaged 7

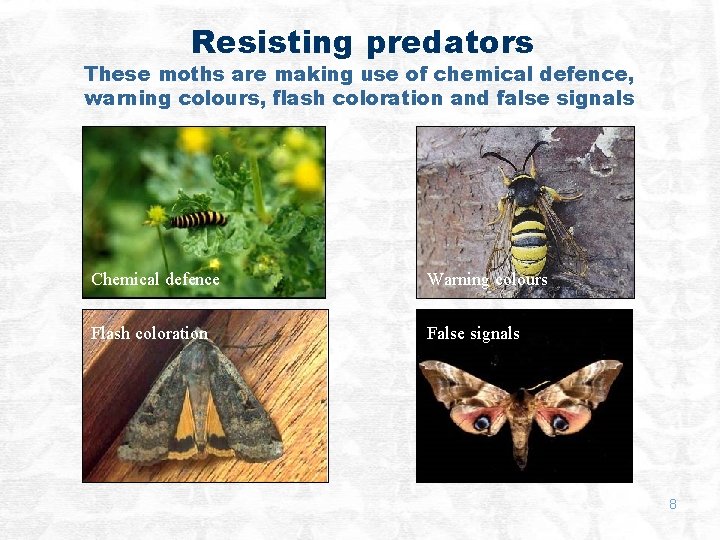

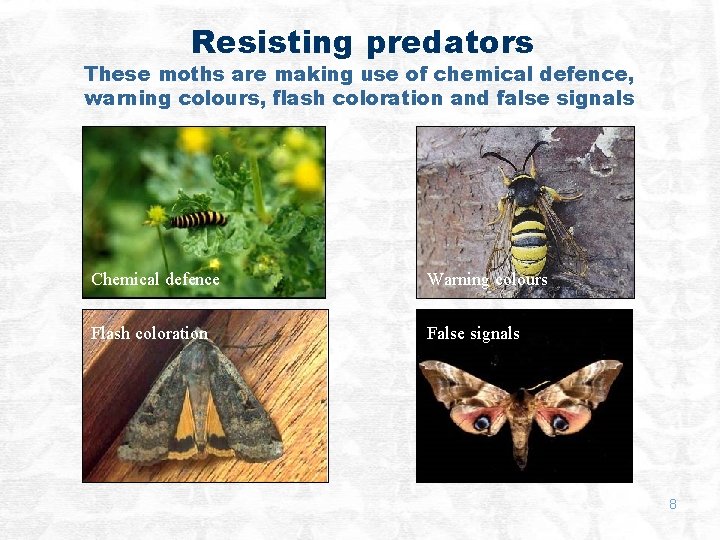

Resisting predators These moths are making use of chemical defence, warning colours, flash coloration and false signals Chemical defence Warning colours Flash coloration False signals 8

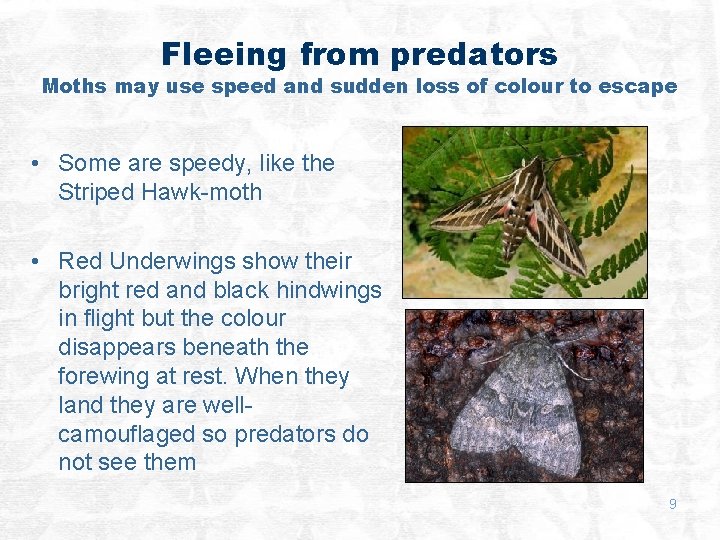

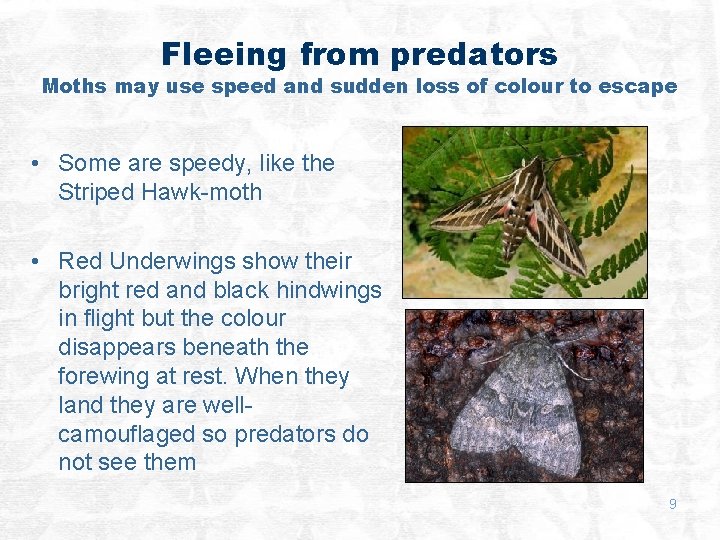

Fleeing from predators Moths may use speed and sudden loss of colour to escape • Some are speedy, like the Striped Hawk-moth • Red Underwings show their bright red and black hindwings in flight but the colour disappears beneath the forewing at rest. When they land they are wellcamouflaged so predators do not see them 9

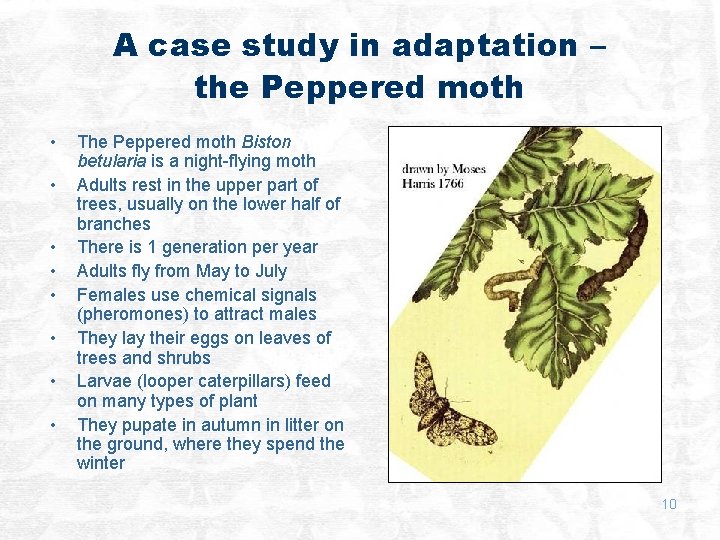

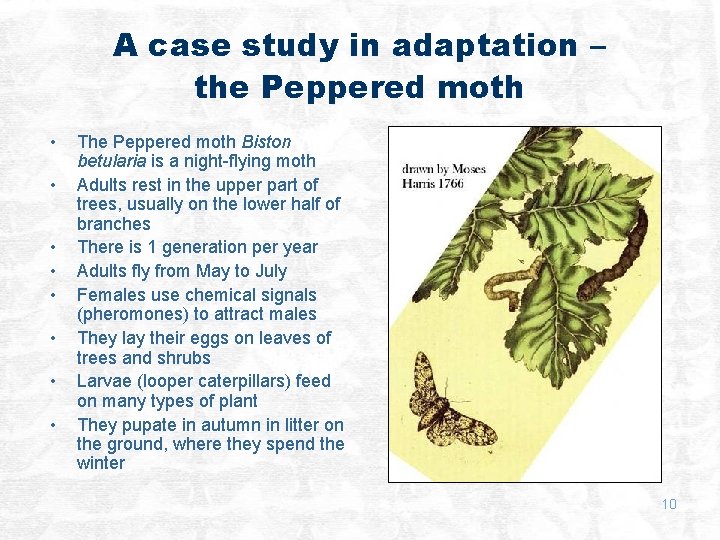

A case study in adaptation – the Peppered moth • • The Peppered moth Biston betularia is a night-flying moth Adults rest in the upper part of trees, usually on the lower half of branches There is 1 generation per year Adults fly from May to July Females use chemical signals (pheromones) to attract males They lay their eggs on leaves of trees and shrubs Larvae (looper caterpillars) feed on many types of plant They pupate in autumn in litter on the ground, where they spend the winter 10

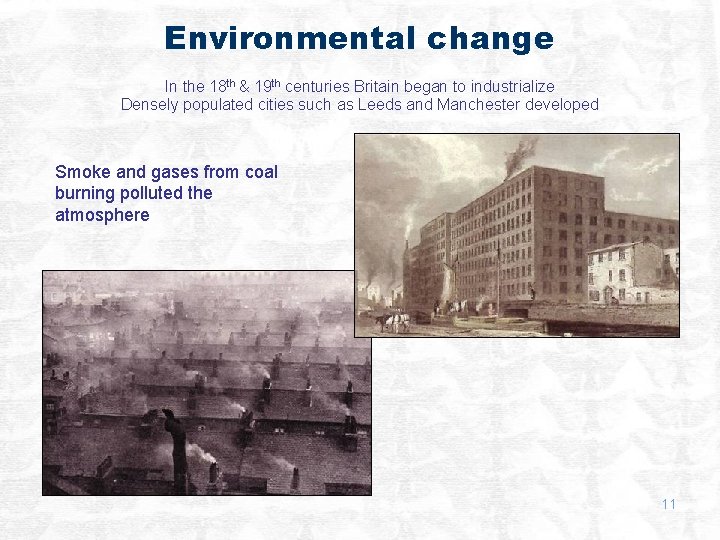

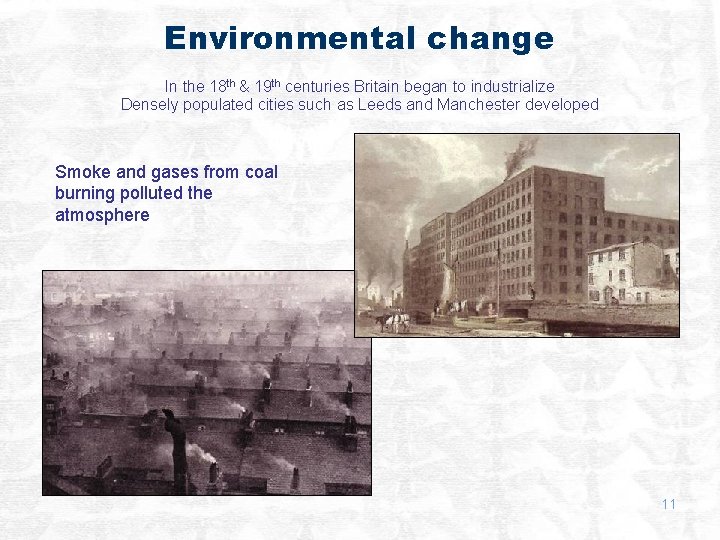

Environmental change In the 18 th & 19 th centuries Britain began to industrialize Densely populated cities such as Leeds and Manchester developed Smoke and gases from coal burning polluted the atmosphere 11

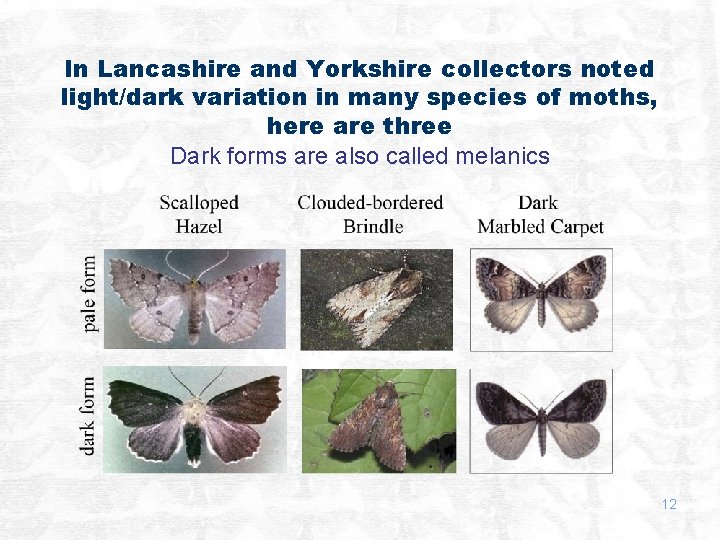

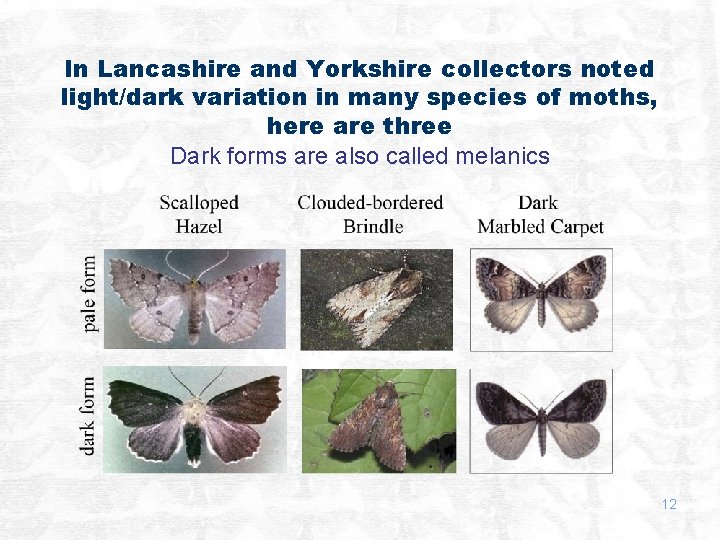

In Lancashire and Yorkshire collectors noted light/dark variation in many species of moths, here are three Dark forms are also called melanics 12

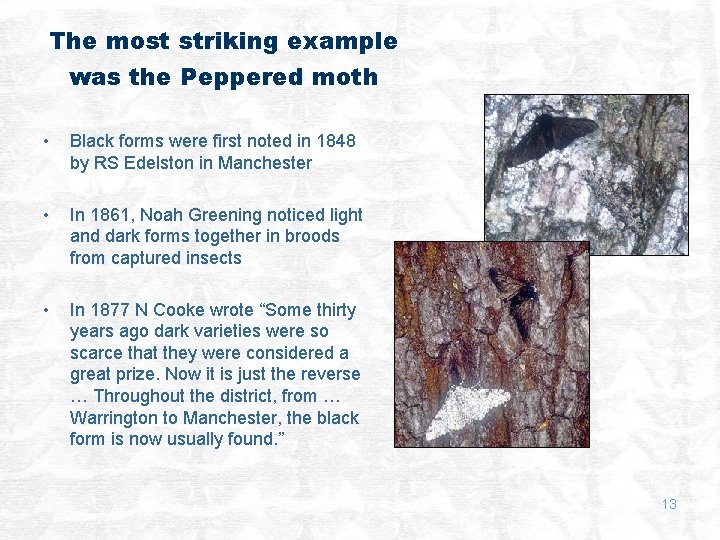

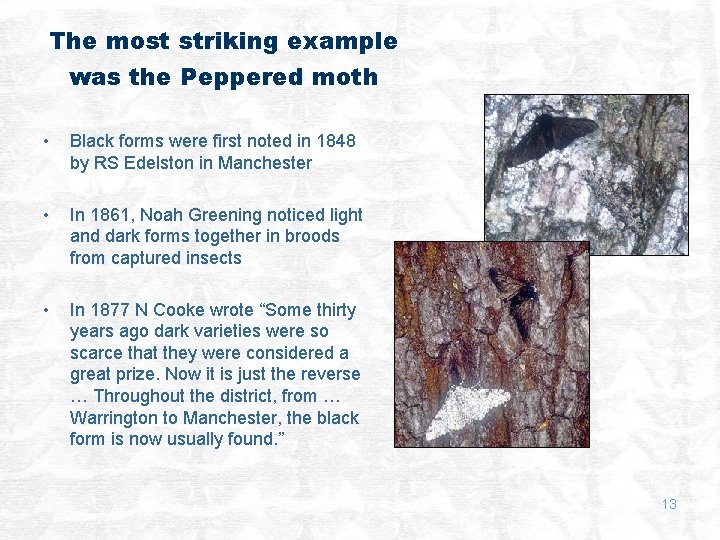

The most striking example was the Peppered moth • Black forms were first noted in 1848 by RS Edelston in Manchester • In 1861, Noah Greening noticed light and dark forms together in broods from captured insects • In 1877 N Cooke wrote “Some thirty years ago dark varieties were so scarce that they were considered a great prize. Now it is just the reverse … Throughout the district, from … Warrington to Manchester, the black form is now usually found. ” 13

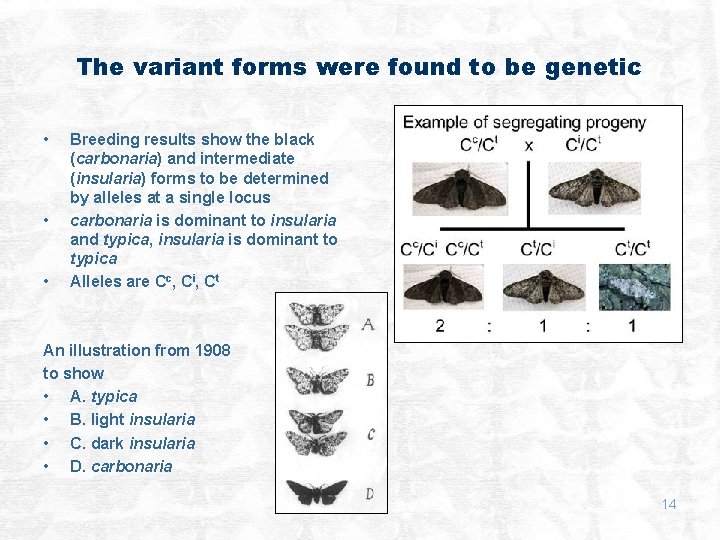

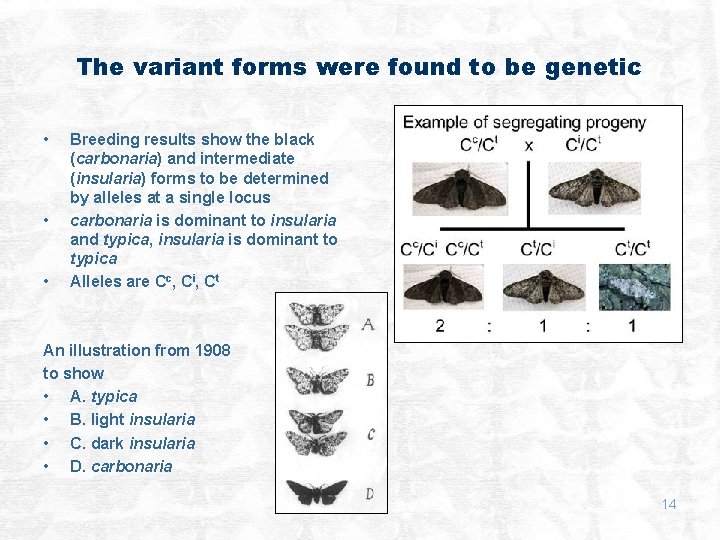

The variant forms were found to be genetic • • • Breeding results show the black (carbonaria) and intermediate (insularia) forms to be determined by alleles at a single locus carbonaria is dominant to insularia and typica, insularia is dominant to typica Alleles are Cc, Ci, Ct An illustration from 1908 to show • A. typica • B. light insularia • C. dark insularia • D. carbonaria 14

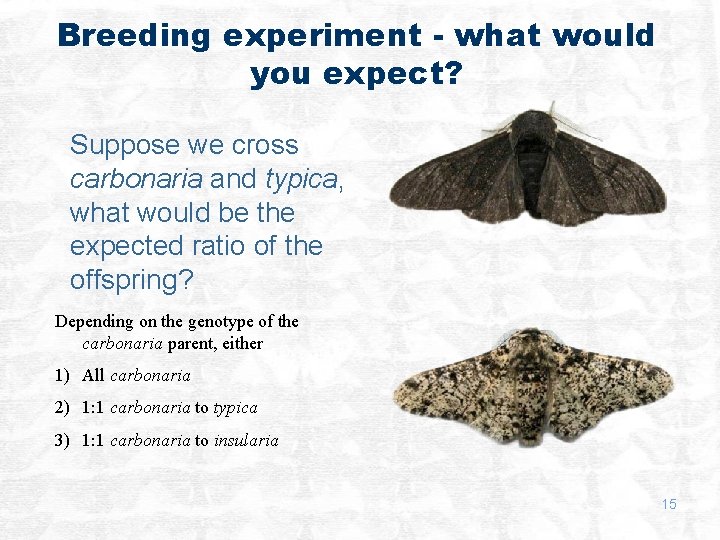

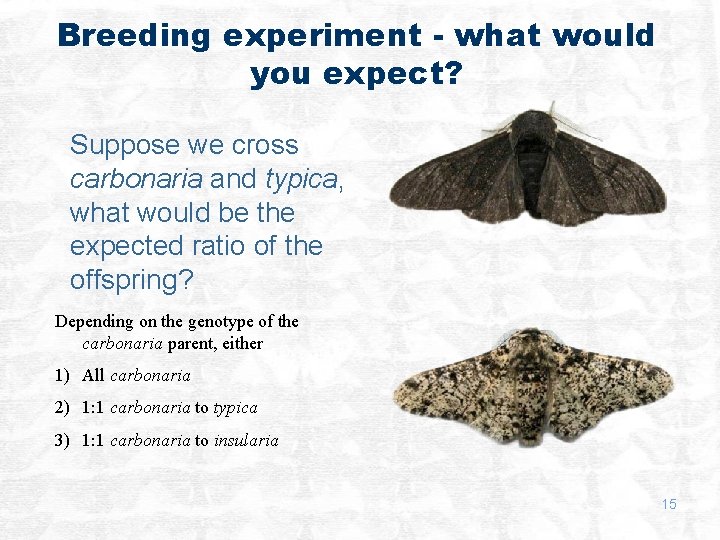

Breeding experiment - what would you expect? Suppose we cross carbonaria and typica, what would be the expected ratio of the offspring? Depending on the genotype of the carbonaria parent, either 1) All carbonaria 2) 1: 1 carbonaria to typica 3) 1: 1 carbonaria to insularia 15

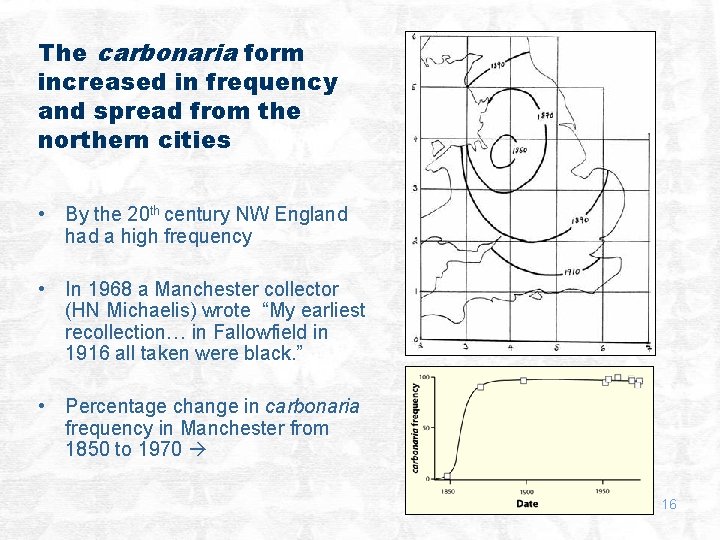

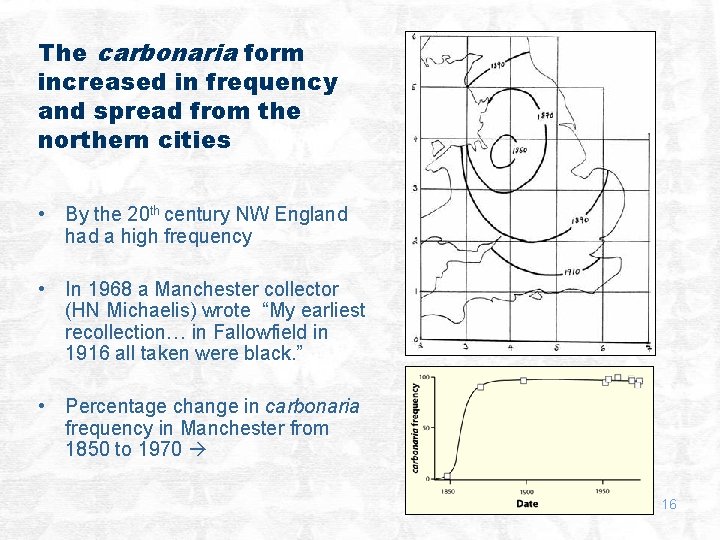

The carbonaria form increased in frequency and spread from the northern cities • By the 20 th century NW England had a high frequency • In 1968 a Manchester collector (HN Michaelis) wrote “My earliest recollection… in Fallowfield in 1916 all taken were black. ” • Percentage change in carbonaria frequency in Manchester from 1850 to 1970 16

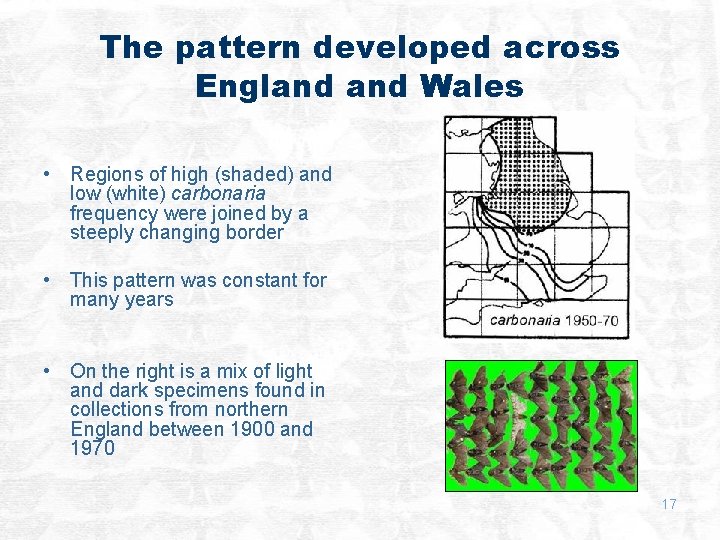

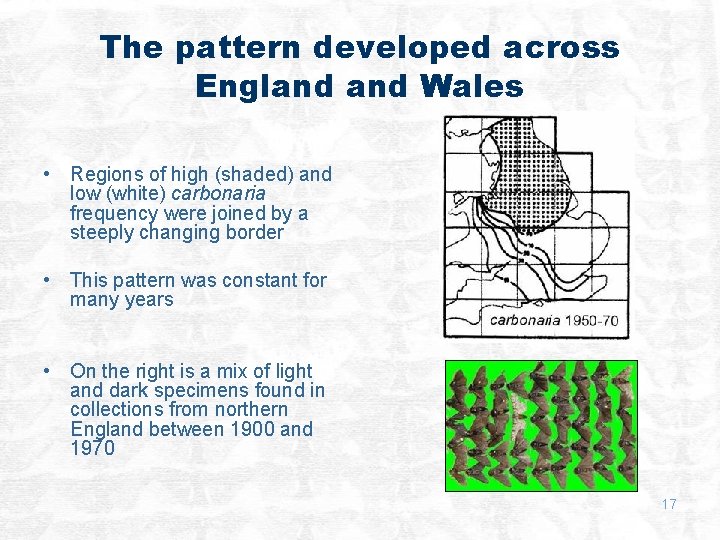

The pattern developed across England Wales • Regions of high (shaded) and low (white) carbonaria frequency were joined by a steeply changing border • This pattern was constant for many years • On the right is a mix of light and dark specimens found in collections from northern England between 1900 and 1970 17

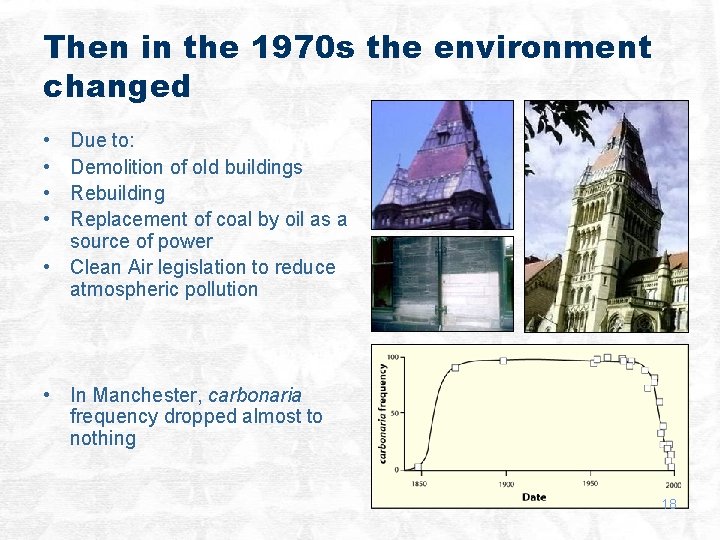

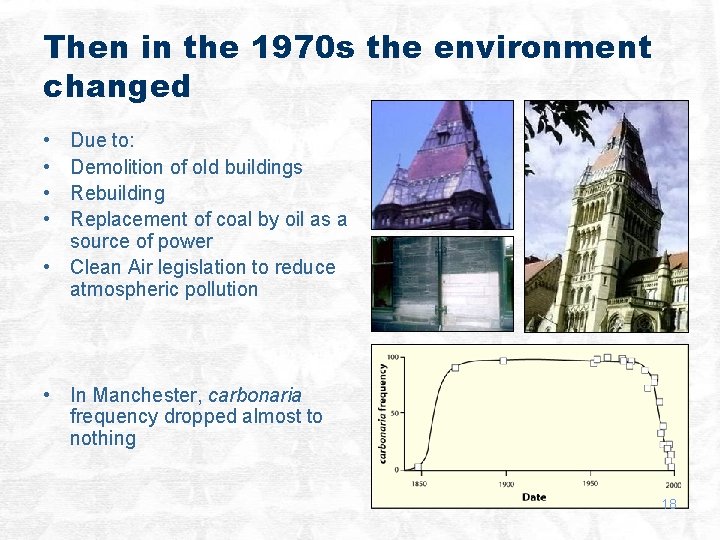

Then in the 1970 s the environment changed • • Due to: Demolition of old buildings Rebuilding Replacement of coal by oil as a source of power • Clean Air legislation to reduce atmospheric pollution • In Manchester, carbonaria frequency dropped almost to nothing 18

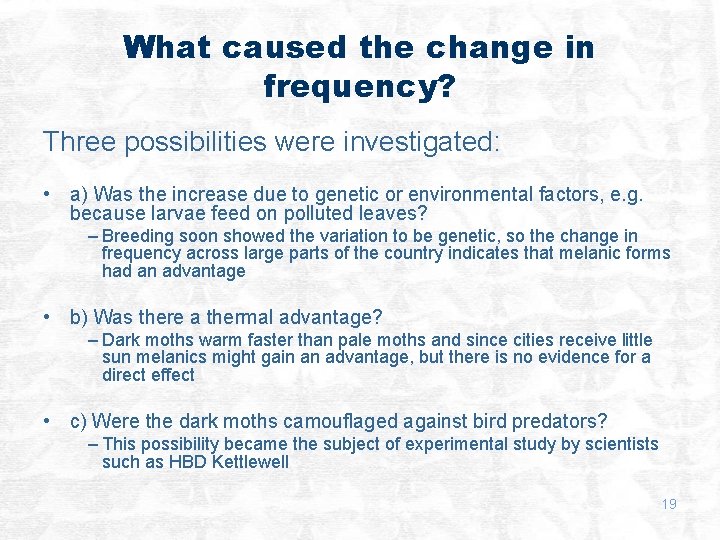

What caused the change in frequency? Three possibilities were investigated: • a) Was the increase due to genetic or environmental factors, e. g. because larvae feed on polluted leaves? – Breeding soon showed the variation to be genetic, so the change in frequency across large parts of the country indicates that melanic forms had an advantage • b) Was there a thermal advantage? – Dark moths warm faster than pale moths and since cities receive little sun melanics might gain an advantage, but there is no evidence for a direct effect • c) Were the dark moths camouflaged against bird predators? – This possibility became the subject of experimental study by scientists such as HBD Kettlewell 19

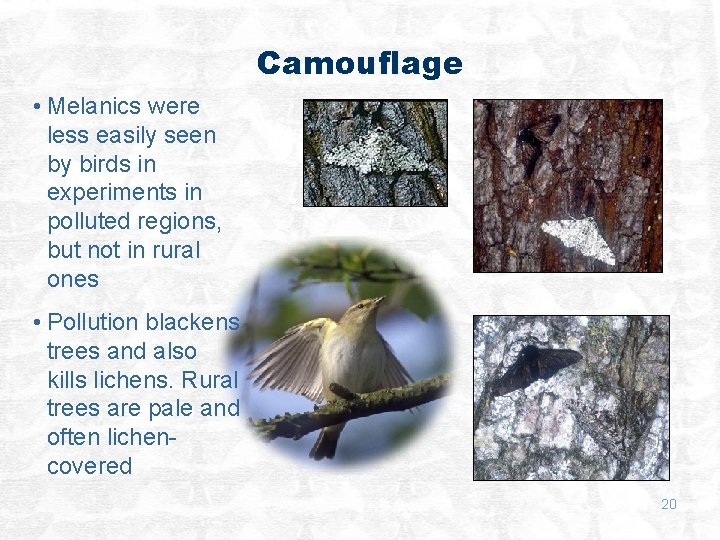

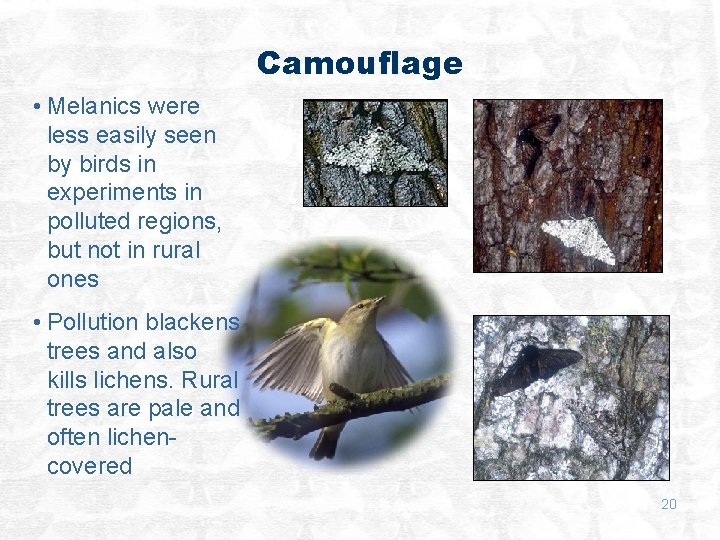

Camouflage • Melanics were less easily seen by birds in experiments in polluted regions, but not in rural ones • Pollution blackens trees and also kills lichens. Rural trees are pale and often lichencovered 20

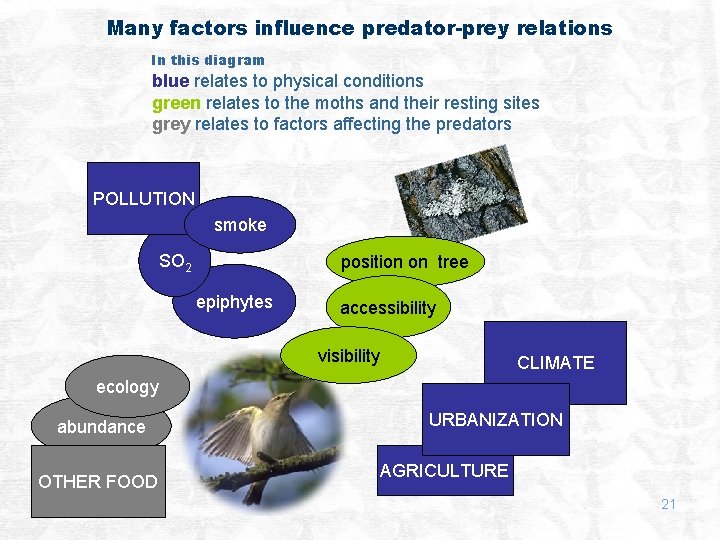

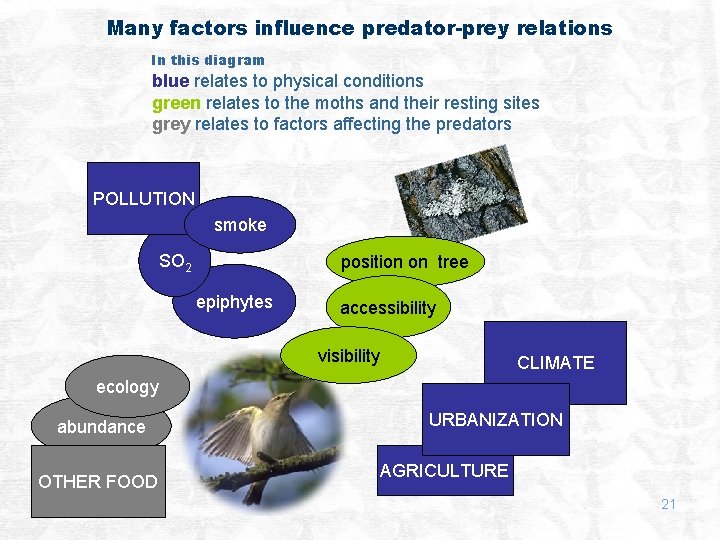

Many factors influence predator-prey relations In this diagram blue relates to physical conditions green relates to the moths and their resting sites grey relates to factors affecting the predators POLLUTION smoke SO 2 position on tree epiphytes accessibility visibility CLIMATE ecology abundance OTHER FOOD URBANIZATION AGRICULTURE 21

All evidence suggests selective predation is the driving force for allele frequency change in the Peppered moth • The Peppered moth has been an example of Evolutionary dynamics since the 1930 s • It has been an example of the importance of Ecology since the 1970 s 22

Evolutionary dynamics • In the 1930 s it was recognised that “the elementary process of evolution is change in allele frequency” • The Peppered moth story illustrates allele frequency change • This change in allele frequencies in a population can result from mutation, random drift, migration and selection. Change can be very rapid when there is selection • The Peppered moth data illustrate rapid change under strong selection 23

Ecology and environment • In the 1970 s many studies showed that human activities sometimes harm the environment, e. g. – Industrial pollution causes acid rain which harms plants – Pesticides and antibiotics cause resistance in pests and pathogens – Increasing population leads to exhaustion of resources – An increase in greenhouse gases leads to global warming but, –Decline in melanic frequency in Peppered moths (and regrowth of lichens) are evidence that our actions sometimes result in environmental improvement 24

Experimental approach • In the 1950 s, Kettlewell carried out studies on the effectiveness of the camouflage of typica and carbonaria Peppered moths • He put samples of the two forms on trees in polluted and unpolluted areas and recorded how many of each form were eaten by birds • More recently, other techniques have been used. For example, birds have looked for digital images of moths! 25

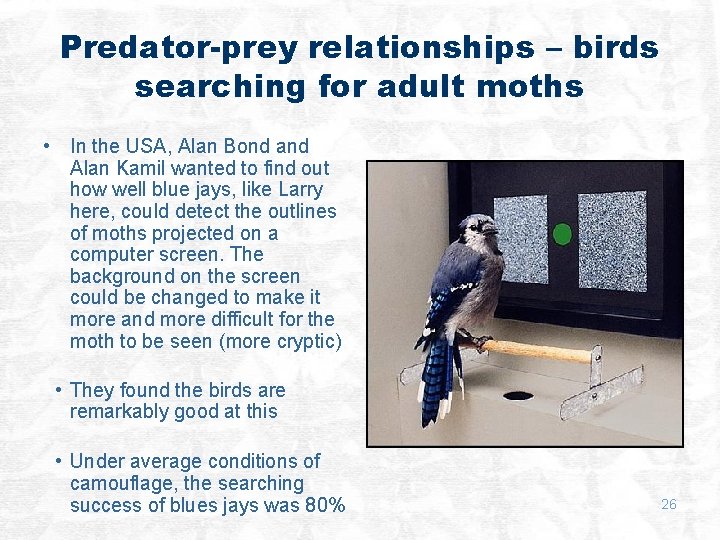

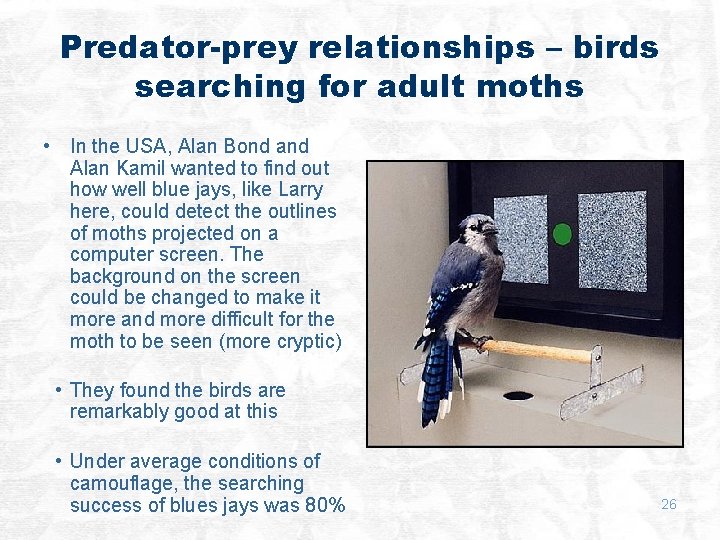

Predator-prey relationships – birds searching for adult moths • In the USA, Alan Bond and Alan Kamil wanted to find out how well blue jays, like Larry here, could detect the outlines of moths projected on a computer screen. The background on the screen could be changed to make it more and more difficult for the moth to be seen (more cryptic) • They found the birds are remarkably good at this • Under average conditions of camouflage, the searching success of blues jays was 80% 26

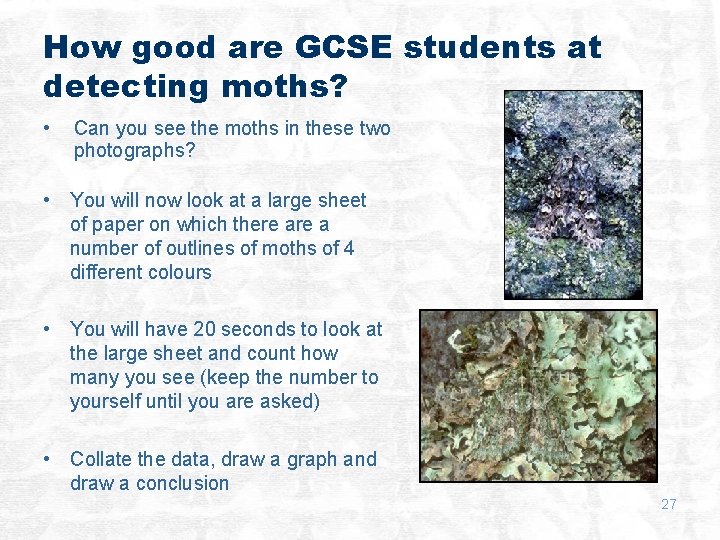

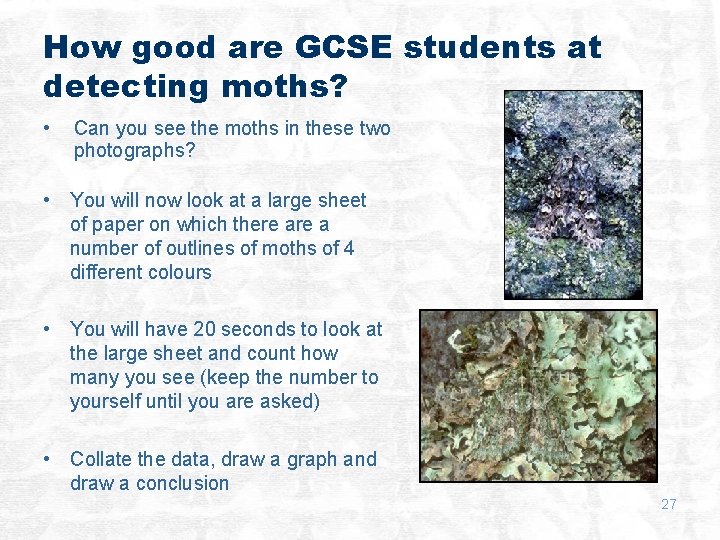

How good are GCSE students at detecting moths? • Can you see the moths in these two photographs? • You will now look at a large sheet of paper on which there a number of outlines of moths of 4 different colours • You will have 20 seconds to look at the large sheet and count how many you see (keep the number to yourself until you are asked) • Collate the data, draw a graph and draw a conclusion 27

Linking your results to the Peppered moth studies • Think about how the results from your investigation tie in with the suggestion that camouflage may be influential in explaining the change in the frequencies of the different forms of the Peppered moth in NW England from 1820 – 1950 • In 80 - 100 words, write a short account of the role of camouflage in the change of frequency in these forms The terms in the box may be helpful evolution - predators - environmental pollution - natural selection - prey - field experiment - different forms of a species changes in allele frequency 28