Part 9 Basic Cryptography 1 Introduction A cryptosystem

Part 9, Basic Cryptography 1

Introduction A cryptosystem is a tuple: (M, K, C, E, D) where M is the set of plaintexts K the set of keys C the set of ciphertexts E: M K C the set of enciphering functions D: C K M the set of deciphering functions 2

The Caesar cipher M = C is the set of sequences of Roman letters K : the set of integers: 0, 1, …, 25 E : the set of enciphering functions Ek , k K : Ek(m)=m+k (mod 26) D : the set of deciphering functions Dk , k K : Dk(c)= c - k (mod 26) 3

Example If the key is K=3, then: “HELLO” “KHOR” Since: H 1 I 2 J 3 K E F G H L M N O O P Q R 4

Cryptanalysis The goal of cryptography is to keep enciphered text secret. The goal of the adversary is to break a ciphertext. Attacks on cryptosystems: § Ciphertext only attacks: the adversary has only access to ciphertexts. The adversary must find a corresponding plaintext. § Known plaintext attacks: the adversary has access to some matched ciphertexts / plaintext pairs. The adversary must find the plaintext of some new ciphertext. § Chosen plaintext attacks: the adversary may ask that specific plaintexts are enciphered. The adversary must find the plaintext that corresponds to a new ciphertext. 5

Kerchoffs’ assumption The adversary knows all details of the encrypting function except the secret key 6

The transposition cipher A transposition cipher rearranges the characters in the plaintext; the key is a permutation p on the characters. The letters are not changed. So -- Ep(x) = p(x) -- Dp(y) = p-1(y) Example: rail-fence cipher Let the ciphertext be “HELLO WORLD”: Write it in two columns as HLOOL ELWRD The ciphertext is “HLOOLELWRD” 7

Anagramming Attacking a transposition cipher requires a rearrangement of the letters of the ciphertext. Anagramming uses tables of n-gram frequencies to identify common n-grams. For example, for the ciphertext “HLOOLELWRD” the digram “HE” occurs with frequency 0. 0305 in English (see textbook). Of the other possible digrams beginning with “H”, “HO” is the next highest. This suggest that “E” follows “H” in the plaintext. And so on. 8

The substitution cipher A substitution cipher changes the characters in the plaintext to produce the ciphertext. Caesar’s cipher is an example. Again the key for this cipher can be found by using a frequency analysis. 9

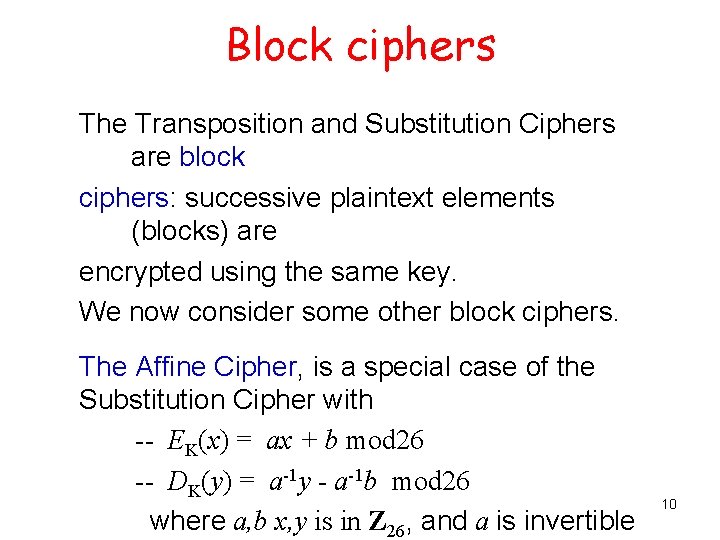

Block ciphers The Transposition and Substitution Ciphers are block ciphers: successive plaintext elements (blocks) are encrypted using the same key. We now consider some other block ciphers. The Affine Cipher, is a special case of the Substitution Cipher with -- EK(x) = ax + b mod 26 -- DK(y) = a-1 y - a-1 b mod 26 where a, b x, y is in Z 26, and a is invertible 10

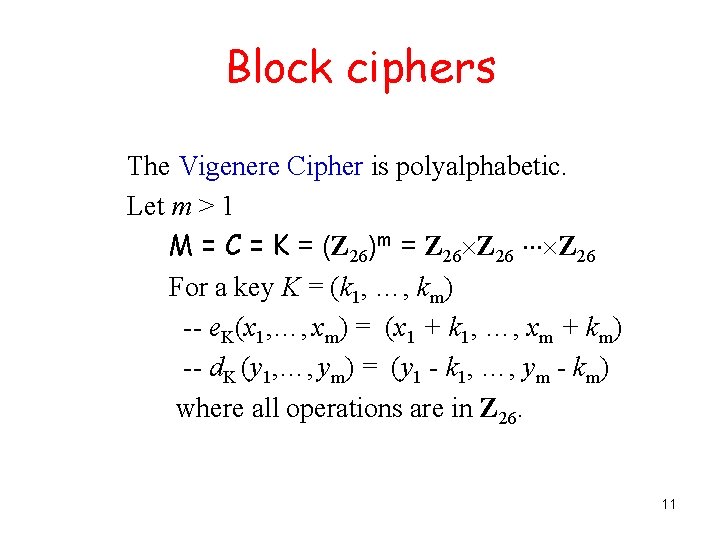

Block ciphers The Vigenere Cipher is polyalphabetic. Let m > 1 M = C = K = (Z 26)m = Z 26 For a key K = (k 1, …, km) -- e. K(x 1, …, xm) = (x 1 + k 1, …, xm + km) -- d. K (y 1, …, ym) = (y 1 - k 1, …, ym - km) where all operations are in Z 26. 11

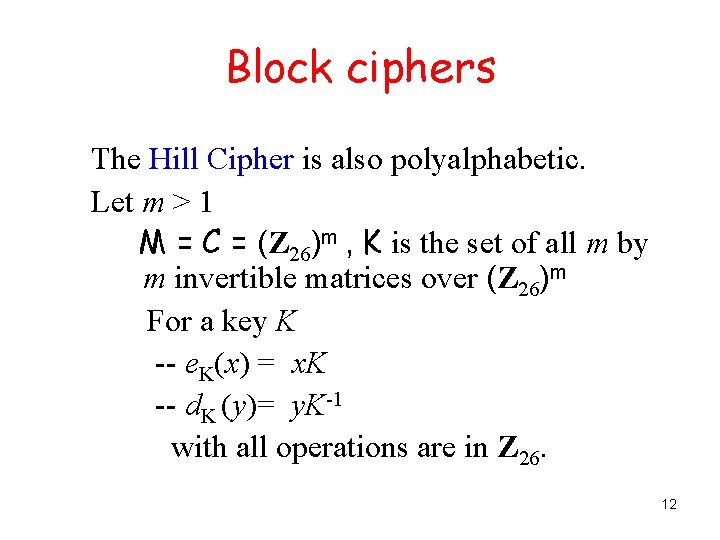

Block ciphers The Hill Cipher is also polyalphabetic. Let m > 1 M = C = (Z 26)m , K is the set of all m by m invertible matrices over (Z 26)m For a key K -- e. K(x) = x. K -- d. K (y)= y. K-1 with all operations are in Z 26. 12

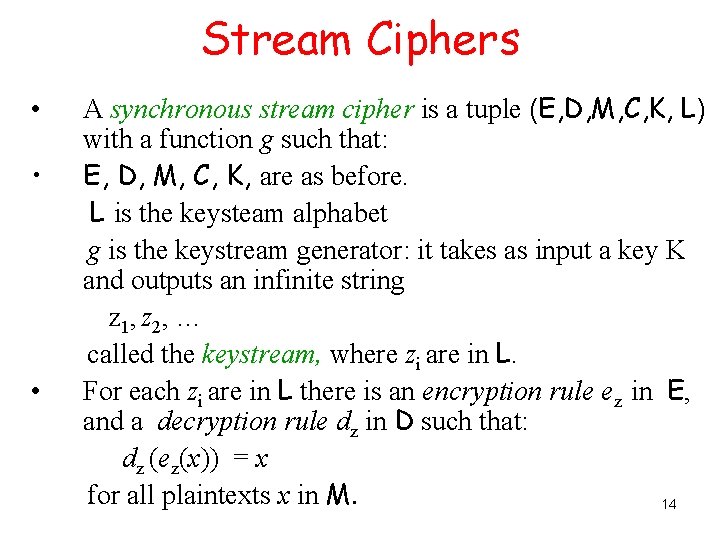

Stream Ciphers The ciphers considered so far are block ciphers. Another type of cryptosystem is the stream cipher. 13

Stream Ciphers • • • A synchronous stream cipher is a tuple (E, D, M, C, K, L) with a function g such that: E, D, M, C, K, are as before. L is the keysteam alphabet g is the keystream generator: it takes as input a key K and outputs an infinite string z 1, z 2, … called the keystream, where zi are in L. For each zi are in L there is an encryption rule ez in E, and a decryption rule dz in D such that: dz (ez(x)) = x for all plaintexts x in M. 14

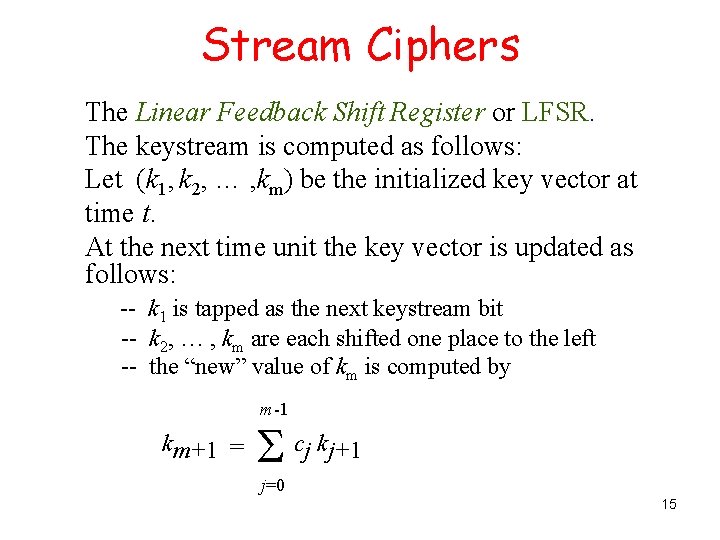

Stream Ciphers The Linear Feedback Shift Register or LFSR. The keystream is computed as follows: Let (k 1, k 2, … , km) be the initialized key vector at time t. At the next time unit the key vector is updated as follows: -- k 1 is tapped as the next keystream bit -- k 2, … , km are each shifted one place to the left -- the “new” value of km is computed by m-1 km+1 = S cj kj+1 j=0 15

Stream Ciphers Let x 1, x 2, … be the plaintext (a binary string). Then the ciphertext is: y 1, y 2, … where yi, = xi + ki, for i = 1, 2, … and the sum is bitwise xor. 16

Cryptanalysis Attacks on Cryptosystems • Ciphertext only attack: the adversary has access a string of ciphertexts: y 1, y 2, … • Known plaintext attack: the adversary has access a string of plaintexts x 1, x 2, … and the corresponding string of ciphertexts: y 1, y 2, … 17

Attacks on Cryptosystems • Chosen plaintext attack: the adversary can choose a string of plaintexts x 1, x 2, … and obtain the corresponding string of ciphertexts: y 1, y 2, … • Chosen ciphertext attack: the adversary can choose a string of ciphertexts: y 1, y 2, … and construct the corresponding string of plaintexts x 1, x 2, … 18

Attacks on Cryptosystems In all these attacks the adversary is given a new ciphertext and must find the corresponding plaintext 19

Cryptanalysis • Cryptanalysis of the transposition cipher and substitution cipher: Ciphertext attack -- use statistical properties of the language • Cryptanalysis of the affine and Vigenere cipher: Ciphertext attack -- use statistical: properties of the language • Attacks on the affine and Vigenere cipher: Ciphertext attack -- use statistical: properties of the language 20

Cryptanalysis • Cryptanalysis of the Hill cipher: Known plaintext attack • Cryptanalysis of the LFSR stream cipher: Known plaintext attack 21

One-time pad This is a variant of the Vigenere cipher. The key string is chosen as a random bit string and is at least as long as the bit string message (plaintext) This cipher has perfect secrecy. (defined later) 22

One-time pad Suppose the key is the bit string K = (k 1, …, km) and the plaintext is the bit string (x 1, …, xm). Then -- e. K(x 1, …, xm) = (x 1 XOR k 1, …, xm XOR km) -- d. K (y 1, …, ym) = (y 1 XOR k 1, …, ym XOR km) Note that (x XOR k) XOR k = x for all bits x, k. 23

Security • Computational security Computationally hard to break: requires super-polynomial computations (in the length of the ciphertext) • Provable security Security is reduced to a well studied problem though to be hard, e. g. factorization. • Unconditional security No bound on computation: cannot be broken even with infinite power/space. Only way to break is by “lucky” guessing. 24

![Some Probability Theory • The random variables X, Y are independent if: Pr[x, y] Some Probability Theory • The random variables X, Y are independent if: Pr[x, y]](http://slidetodoc.com/presentation_image_h/734d6dcab3c646cd7c004a2b6b26282b/image-25.jpg)

Some Probability Theory • The random variables X, Y are independent if: Pr[x, y] = Pr[x]. Pr[y], for all x, y in X In general, Pr[x, y] = Pr[x|y]. Pr[y] = Pr[y|x]. Pr[x], for all x, y in X 25

![Some Probability Theory • Bayes’ Law: Pr[x|y] Pr[y|x]. Pr[x] = --------Pr[y] for all x, Some Probability Theory • Bayes’ Law: Pr[x|y] Pr[y|x]. Pr[x] = --------Pr[y] for all x,](http://slidetodoc.com/presentation_image_h/734d6dcab3c646cd7c004a2b6b26282b/image-26.jpg)

Some Probability Theory • Bayes’ Law: Pr[x|y] Pr[y|x]. Pr[x] = --------Pr[y] for all x, y in X • Corollary: X, Y are independent random variables (r. v. ) if and only if Pr[x|y] = Pr[x] for all x, y in X 26

![Perfect secrecy A cryptosystem has perfect secrecy if : Pr[x|y] = Pr[x], for all Perfect secrecy A cryptosystem has perfect secrecy if : Pr[x|y] = Pr[x], for all](http://slidetodoc.com/presentation_image_h/734d6dcab3c646cd7c004a2b6b26282b/image-27.jpg)

Perfect secrecy A cryptosystem has perfect secrecy if : Pr[x|y] = Pr[x], for all x in M and y in C. That is: knowledge of the ciphertext y, offers no advantage to the adversary to determine the plaintext x. (there is no advantage in eavesdropping) 27

DES is a Feistel cipher. Block length 64 bits (effectively 56) Key length 56 bits Ciphertext length 64 bits 28

![DES It has a round function g for which: g([Li-1, Ri-1 ]), Ki ) DES It has a round function g for which: g([Li-1, Ri-1 ]), Ki )](http://slidetodoc.com/presentation_image_h/734d6dcab3c646cd7c004a2b6b26282b/image-29.jpg)

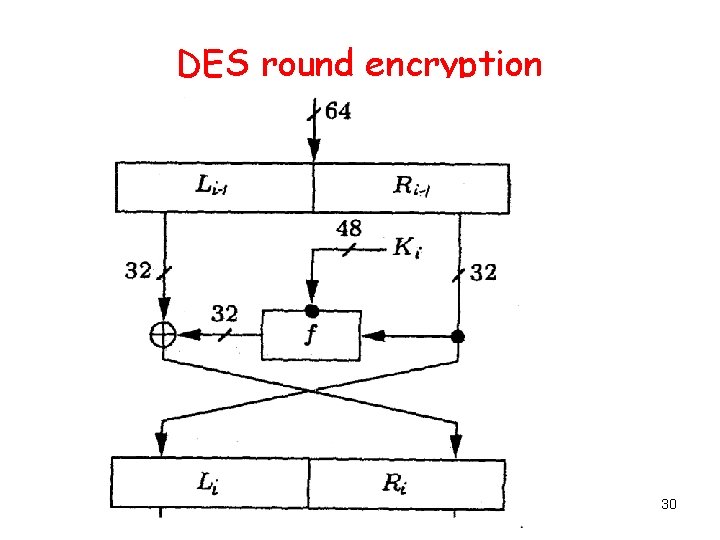

DES It has a round function g for which: g([Li-1, Ri-1 ]), Ki ) = (Li , Ri), where Li = Ri-1 and Ri = Li-1 XOR f (Ri-1, Ki). 29

DES round encryption 30

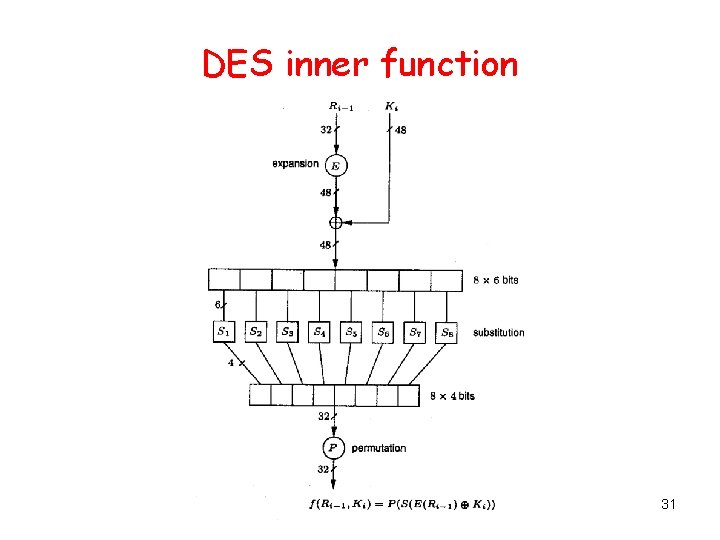

DES inner function 31

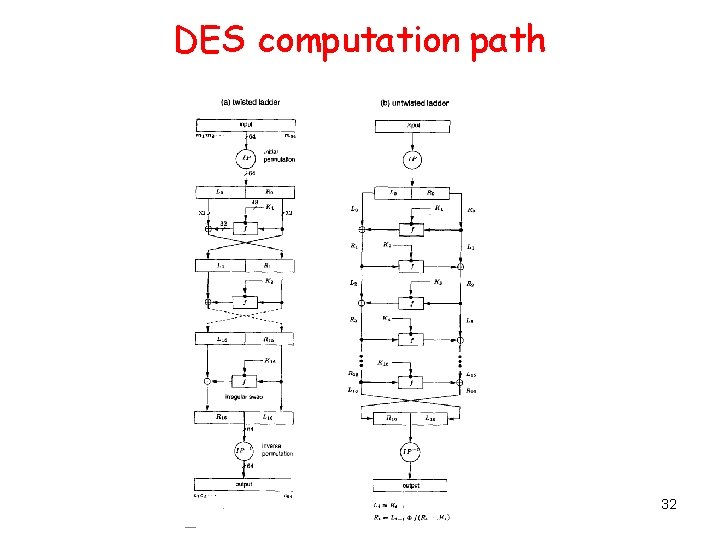

DES computation path 32

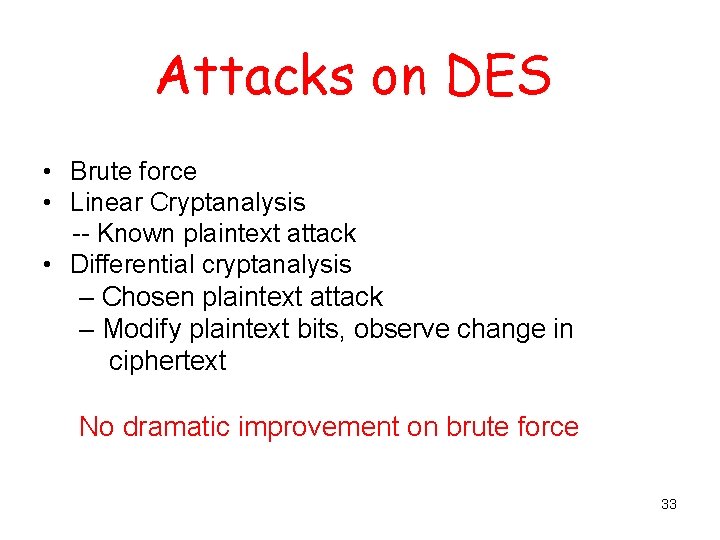

Attacks on DES • Brute force • Linear Cryptanalysis -- Known plaintext attack • Differential cryptanalysis – Chosen plaintext attack – Modify plaintext bits, observe change in ciphertext No dramatic improvement on brute force 33

Countering Attacks • Large keyspace combats brute force attack • Triple DES (say EDE mode, 2 or 3 keys) • Use AES 34

AES Block length 128 bits. Key lengths 128 (or 192 or 256). The AES is an iterated cipher with Nr=10 (or 12 or 14) In each round we have: • Subkey mixing • A substitution • A permutation 35

Modes of operation Four basic modes of operation are available for block ciphers: • Electronic codebook mode: ECB • Cipher block chaining mode: CBC • Cipher feedback mode: CFB • Output feedback mode: OFB 36

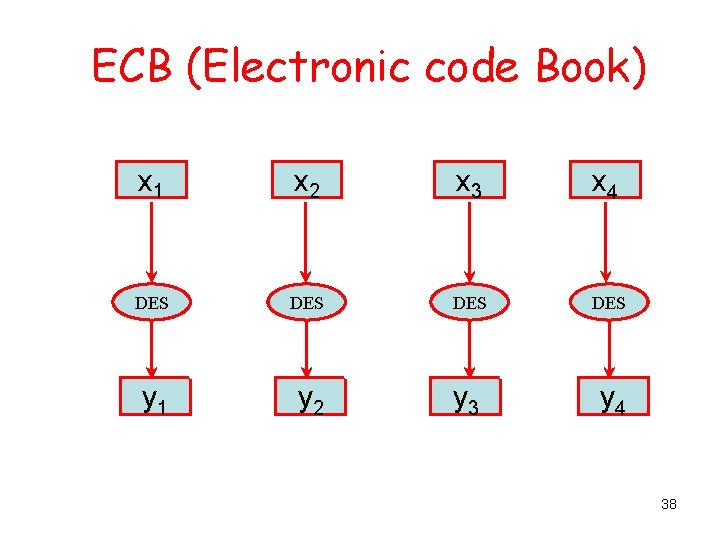

Electronic Codebook mode, ECB Each plaintext xi is encrypted with the same key K: yi = e. K(xi). So, the naïve use of a block cipher. 37

ECB (Electronic code Book) x 1 x 2 x 3 x 4 DES DES y 1 y 2 y 3 y 4 38

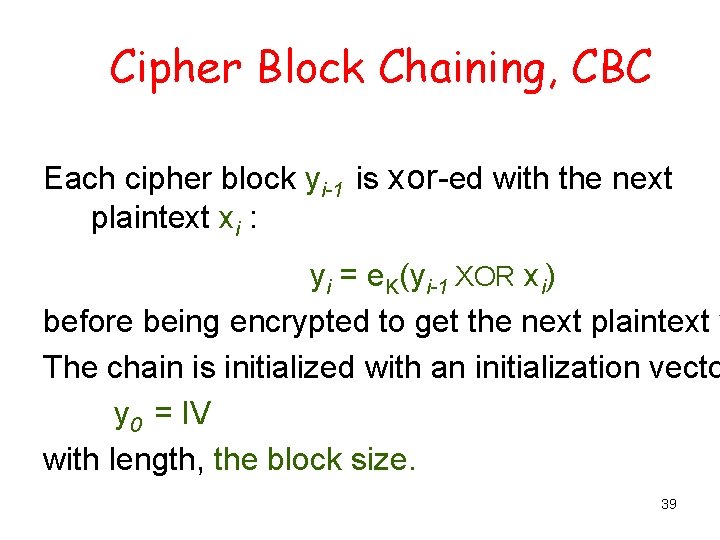

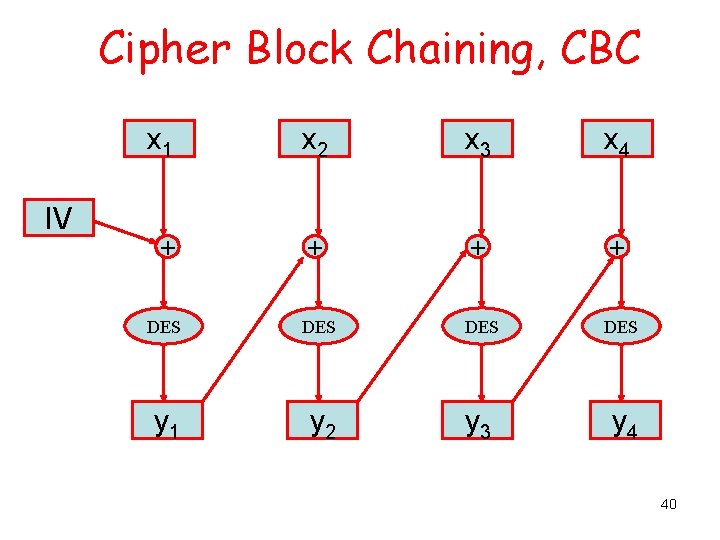

Cipher Block Chaining, CBC Each cipher block yi-1 is xor-ed with the next plaintext xi : yi = e. K(yi-1 XOR xi) before being encrypted to get the next plaintext y The chain is initialized with an initialization vecto y 0 = IV with length, the block size. 39

Cipher Block Chaining, CBC IV x 1 x 2 x 3 x 4 + + DES DES y 1 y 2 y 3 y 4 40

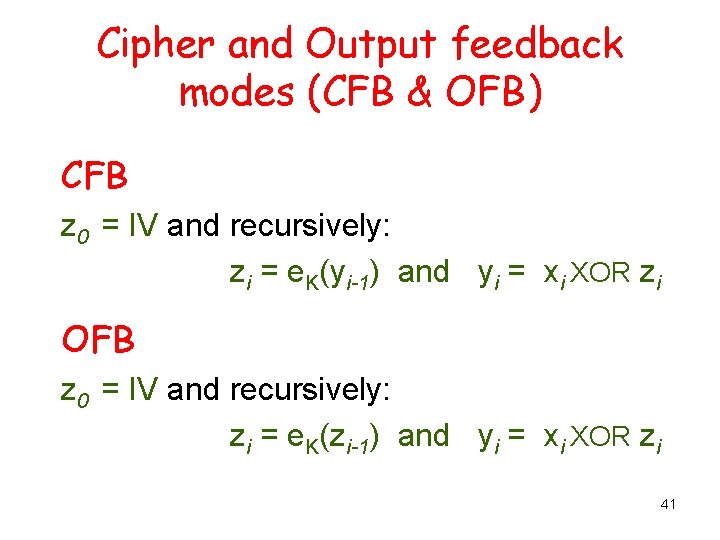

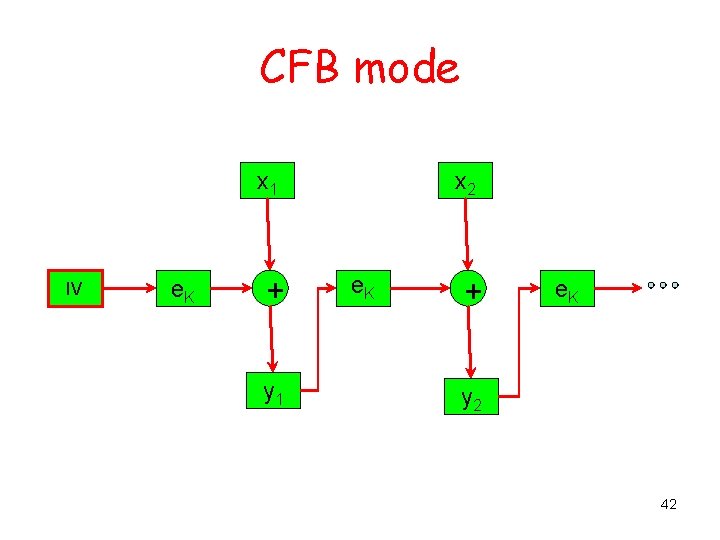

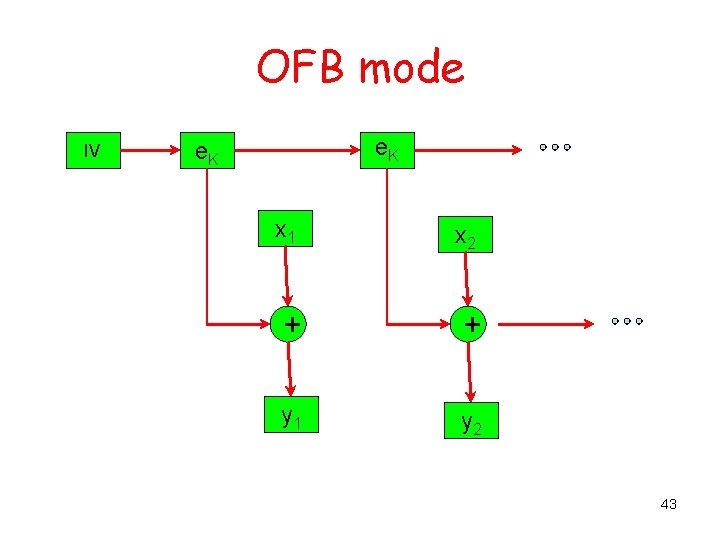

Cipher and Output feedback modes (CFB & OFB) CFB z 0 = IV and recursively: zi = e. K(yi-1) and yi = xi XOR zi OFB z 0 = IV and recursively: zi = e. K(zi-1) and yi = xi XOR zi 41

CFB mode x 1 IV e. K + y 1 x 2 e. K + e. K y 2 42

OFB mode IV e. K x 1 x 2 + + y 1 y 2 43

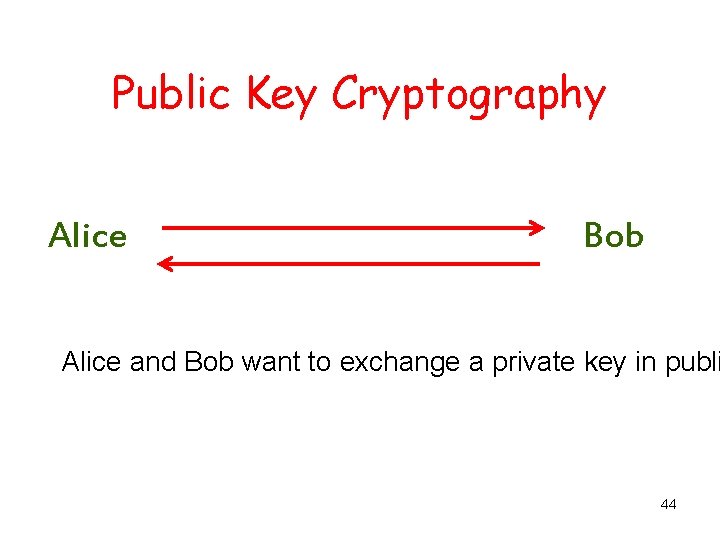

Public Key Cryptography Alice Bob Alice and Bob want to exchange a private key in publi 44

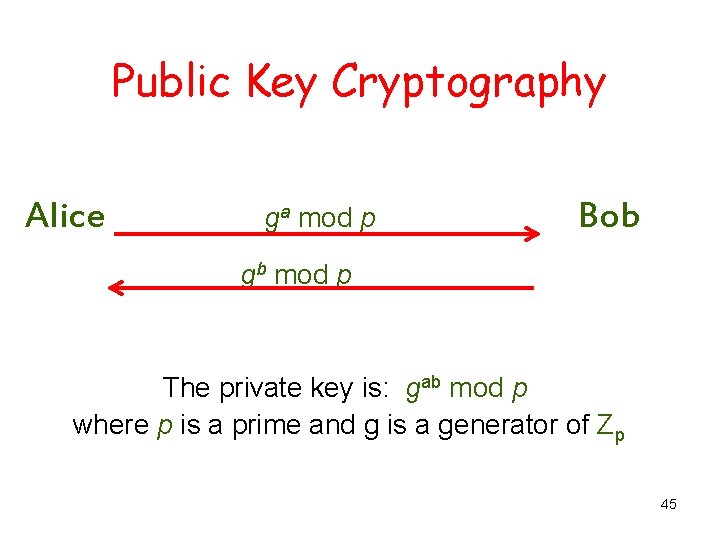

Public Key Cryptography Alice ga mod p Bob gb mod p The private key is: gab mod p where p is a prime and g is a generator of Zp 45

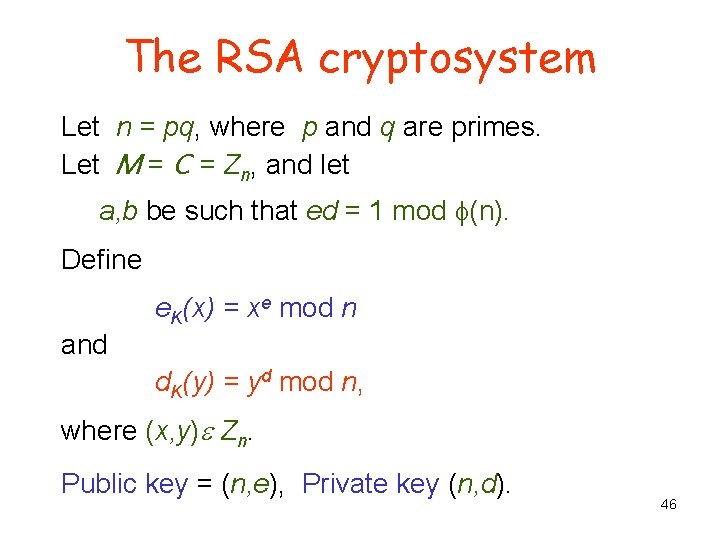

The RSA cryptosystem Let n = pq, where p and q are primes. Let M = C = Zn, and let a, b be such that ed = 1 mod f(n). Define e. K(x) = xe mod n and d. K(y) = yd mod n, where (x, y)e Zn. Public key = (n, e), Private key (n, d). 46

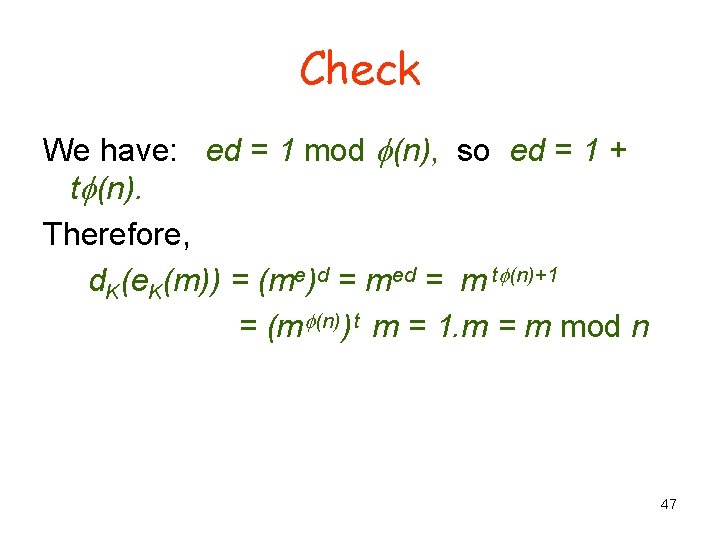

Check We have: ed = 1 mod f(n), so ed = 1 + tf(n). Therefore, d. K(e. K(m)) = (me)d = med = m tf(n)+1 = (mf(n)) t m = 1. m = m mod n 47

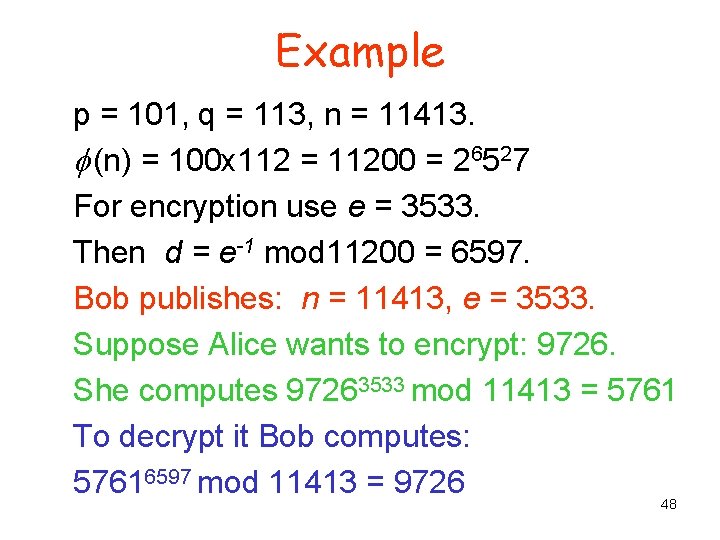

Example p = 101, q = 113, n = 11413. f (n) = 100 x 112 = 11200 = 26527 For encryption use e = 3533. Then d = e-1 mod 11200 = 6597. Bob publishes: n = 11413, e = 3533. Suppose Alice wants to encrypt: 9726. She computes 97263533 mod 11413 = 5761 To decrypt it Bob computes: 57616597 mod 11413 = 9726 48

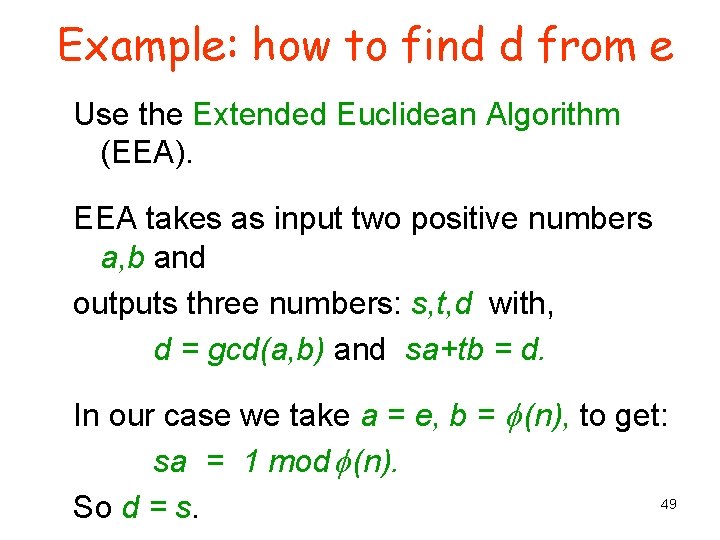

Example: how to find d from e Use the Extended Euclidean Algorithm (EEA). EEA takes as input two positive numbers a, b and outputs three numbers: s, t, d with, d = gcd(a, b) and sa+tb = d. In our case we take a = e, b = f (n), to get: sa = 1 mod f (n). 49 So d = s.

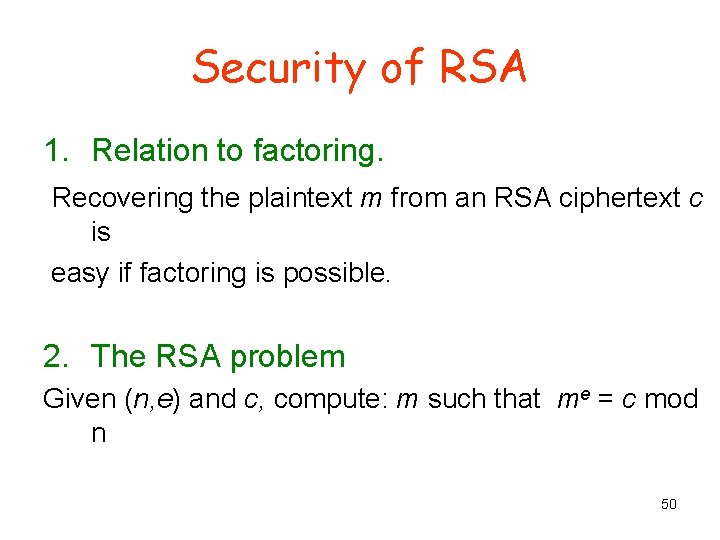

Security of RSA 1. Relation to factoring. Recovering the plaintext m from an RSA ciphertext c is easy if factoring is possible. 2. The RSA problem Given (n, e) and c, compute: m such that me = c mod n 50

The Rabin cryptosystem Let n = pq, p, q primes with p, q C = Z n* 3 mod 4. Let P = and define K = {(n, p, q)}. For K = (n, p, q) define e. K(x) = x 2 mod n d. K(y) = a square root of y mod n The value of n is the public key, while p, q are the private key. One needs the factors p, q of n to find the square root. 51

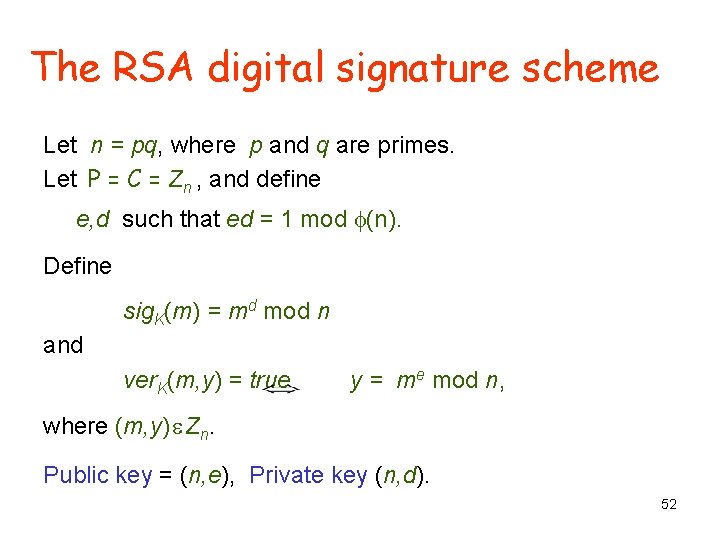

The RSA digital signature scheme Let n = pq, where p and q are primes. Let P = C = Zn , and define e, d such that ed = 1 mod f(n). Define sig. K(m) = md mod n and ver. K(m, y) = true y = me mod n, where (m, y) e Zn. Public key = (n, e), Private key (n, d). 52

The Digital Signature Algorithm Let p be a an L-bit prime, 512 L 1024 and L 0 mod 64 , let q be a 160 -bit prime that divides p-1 and Let e Zp* be a q-th root of 1 modulo p. Let M = Zp-1, C = Zq x Zq and K = {(x, y): y = x modp }. • The public key is p, q, , y. • The private key is (p, q, ), x. 53

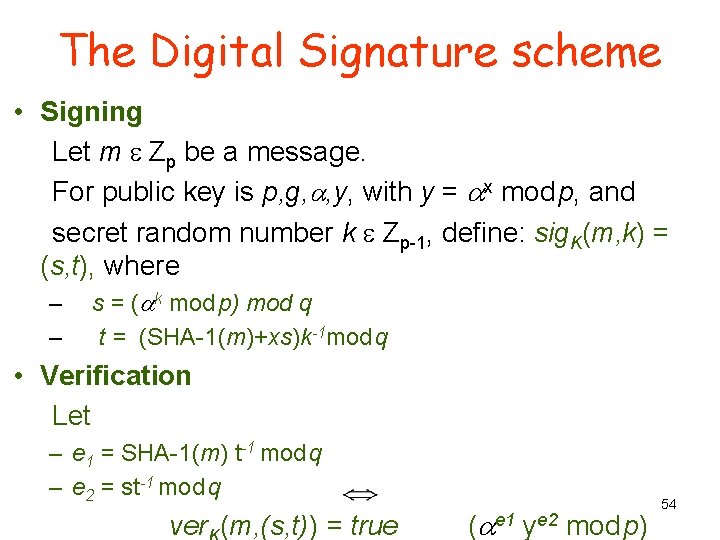

The Digital Signature scheme • Signing Let m e Zp be a message. For public key is p, g, , y, with y = x mod p, and secret random number k e Zp-1, define: sig. K(m, k) = (s, t), where – – s = ( k mod p) mod q t = (SHA-1(m)+xs)k-1 mod q • Verification Let – e 1 = SHA-1(m) t-1 mod q – e 2 = st-1 mod q ver (m, (s, t)) = true ( e 1 ye 2 mod p) 54

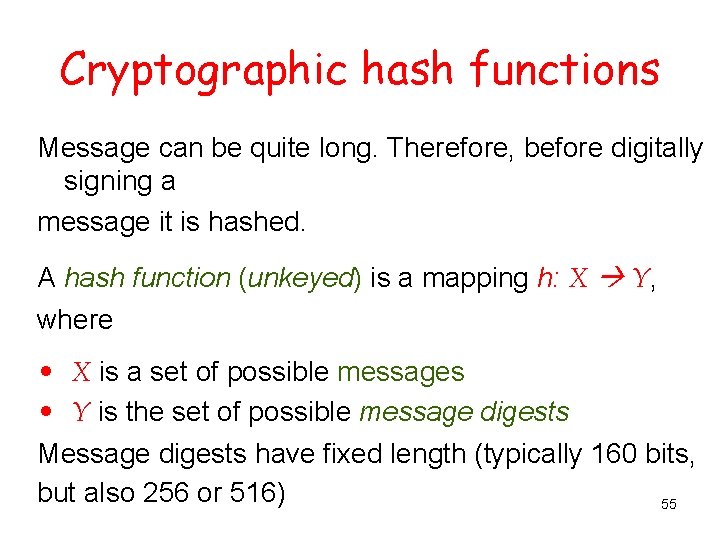

Cryptographic hash functions Message can be quite long. Therefore, before digitally signing a message it is hashed. A hash function (unkeyed) is a mapping h: X Y, where • X is a set of possible messages • Y is the set of possible message digests Message digests have fixed length (typically 160 bits, but also 256 or 516) 55

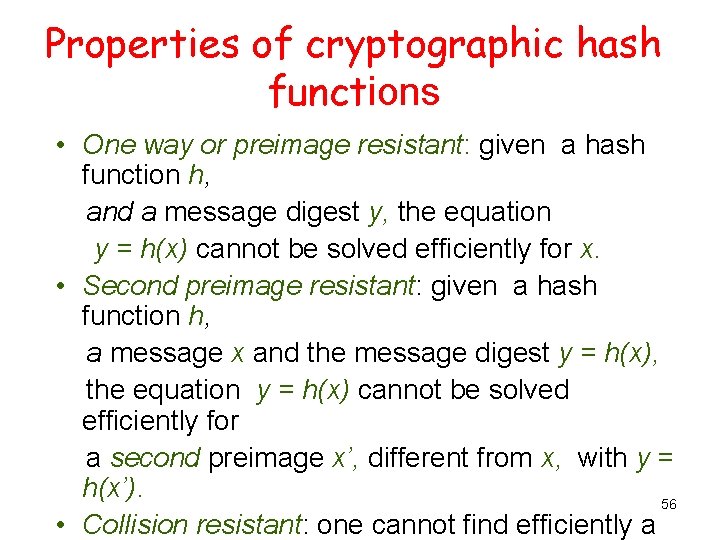

Properties of cryptographic hash functions • One way or preimage resistant: given a hash function h, and a message digest y, the equation y = h(x) cannot be solved efficiently for x. • Second preimage resistant: given a hash function h, a message x and the message digest y = h(x), the equation y = h(x) cannot be solved efficiently for a second preimage x’, different from x, with y = h(x’). 56 • Collision resistant: one cannot find efficiently a

- Slides: 56