Part 6 Special Topics Chapter 19 Shellcode Analysis

- Slides: 42

Part 6: Special Topics Chapter 19: Shellcode Analysis Chapter 20: C++ Analysis Chapter 21: 64 -bit Malware

Chapter 19: Shellcode Analysis

Shellcode Analysis Shellcode n n Payload of raw executable code that allows adversary to obtain interactive shell access on compromised system Often used alongside exploit to subvert running program Issues to overcome n n n Getting placed in preferred memory location Applying address locations if it cannot be placed properly Loading required libraries and resolving external dependencies

Shellcode Analysis 1. Position-Independent Code 2. Identifying Execution Location 3. Manual Symbol Resolution 4. Shellcode Encodings 5. NOP Sleds 6. Finding Shellcode

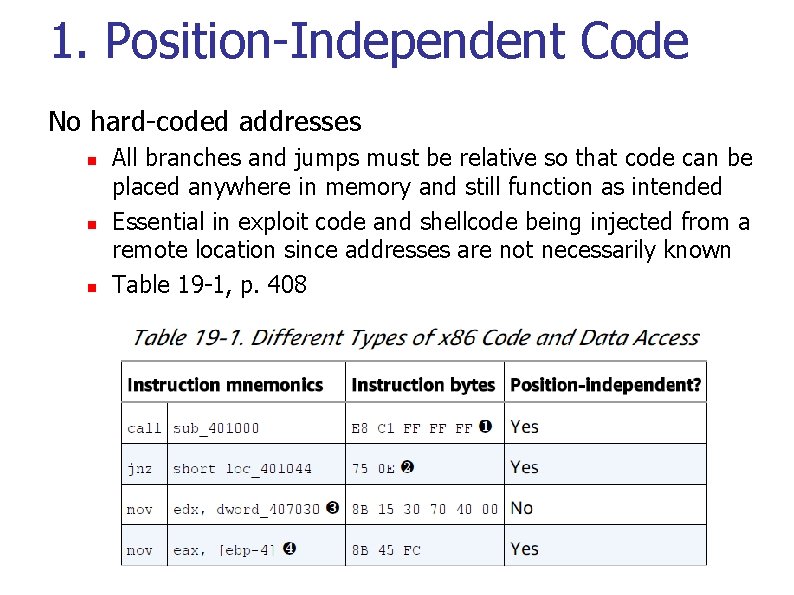

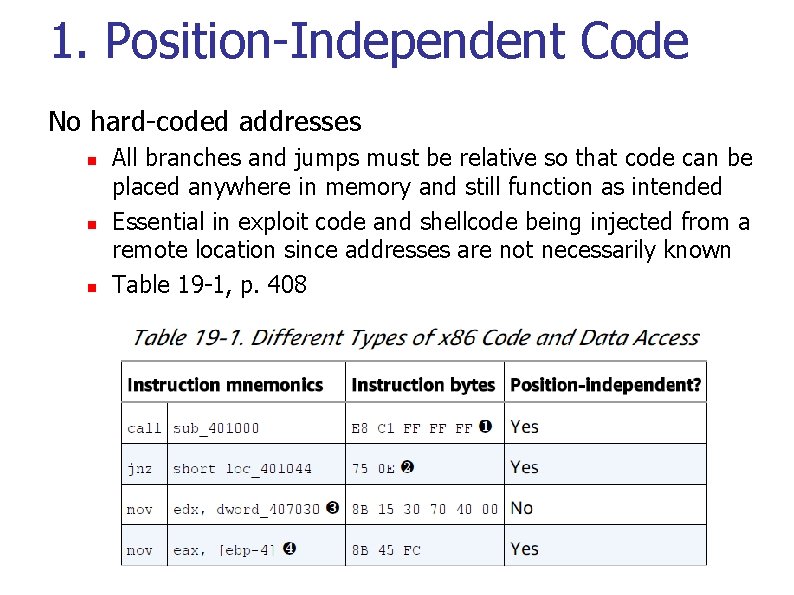

1. Position-Independent Code No hard-coded addresses n n n All branches and jumps must be relative so that code can be placed anywhere in memory and still function as intended Essential in exploit code and shellcode being injected from a remote location since addresses are not necessarily known Table 19 -1, p. 408

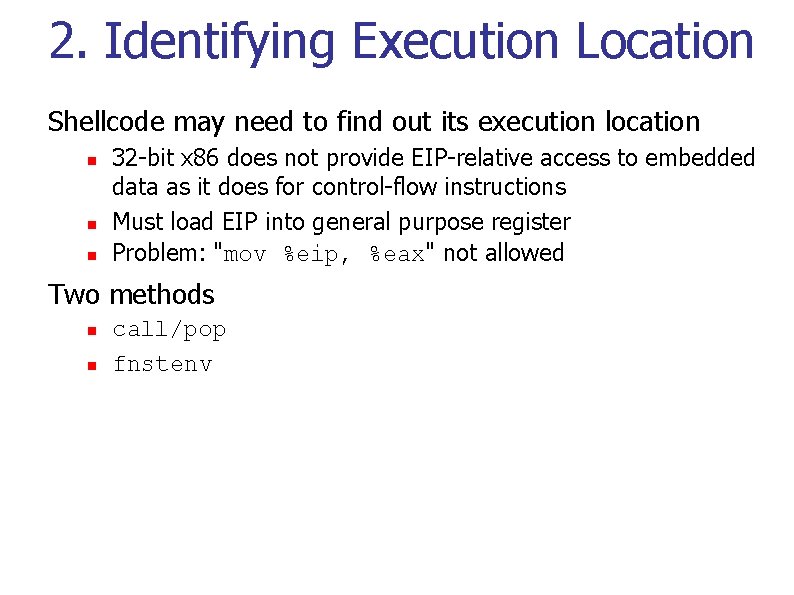

2. Identifying Execution Location Shellcode may need to find out its execution location n 32 -bit x 86 does not provide EIP-relative access to embedded data as it does for control-flow instructions Must load EIP into general purpose register Problem: "mov %eip, %eax" not allowed Two methods n n call/pop fnstenv

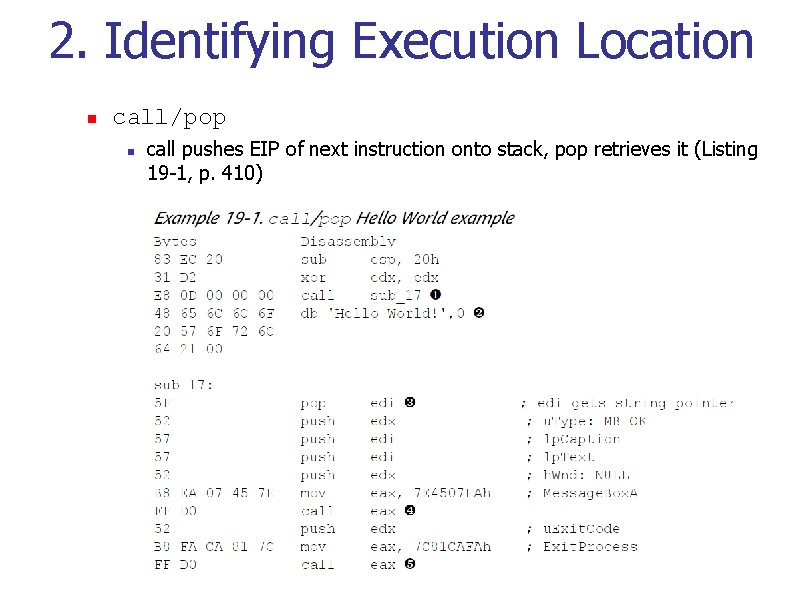

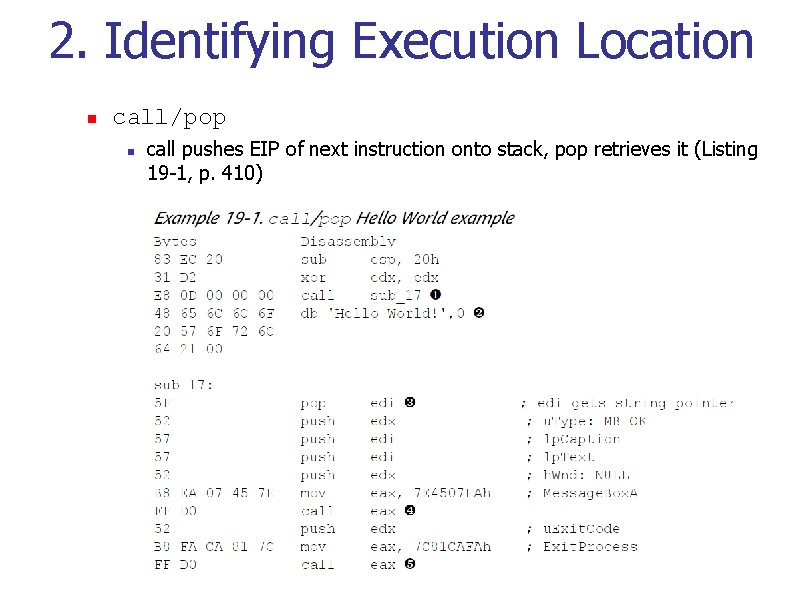

2. Identifying Execution Location n call/pop n call pushes EIP of next instruction onto stack, pop retrieves it (Listing 19 -1, p. 410)

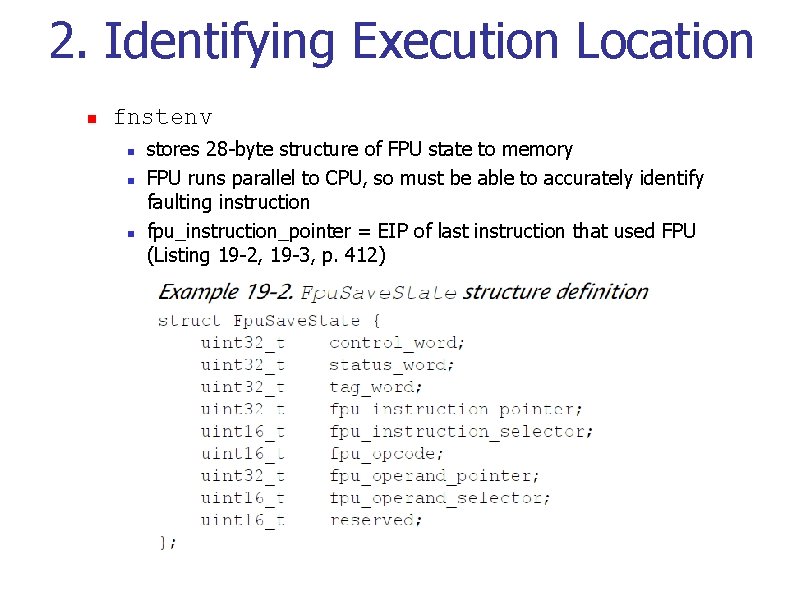

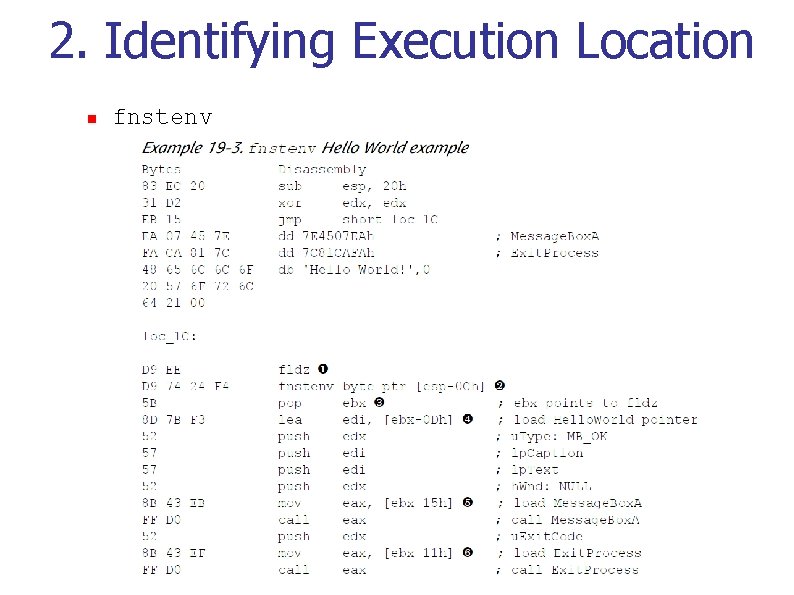

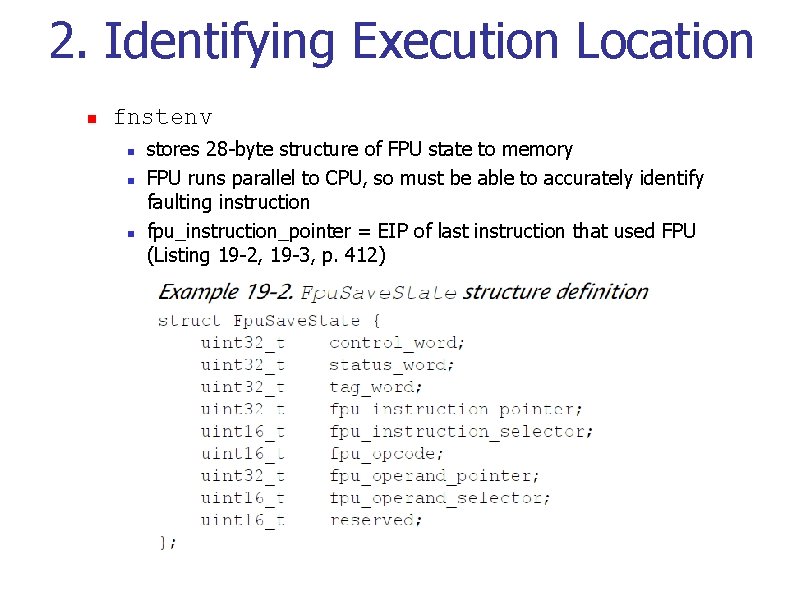

2. Identifying Execution Location n fnstenv n n n stores 28 -byte structure of FPU state to memory FPU runs parallel to CPU, so must be able to accurately identify faulting instruction fpu_instruction_pointer = EIP of last instruction that used FPU (Listing 19 -2, 19 -3, p. 412)

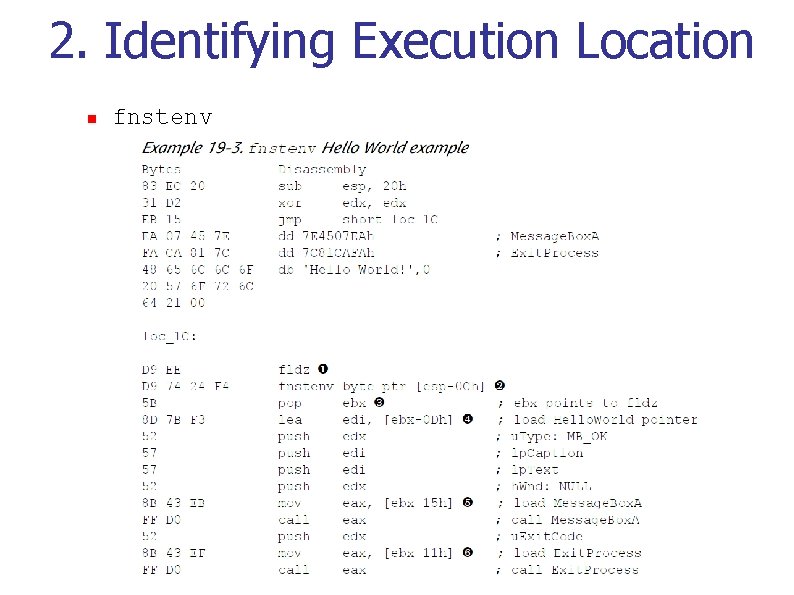

2. Identifying Execution Location n fnstenv

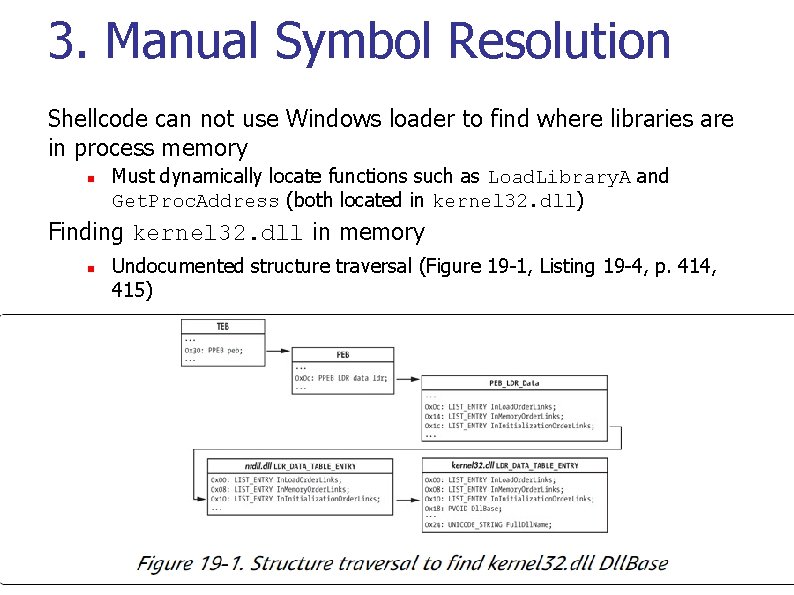

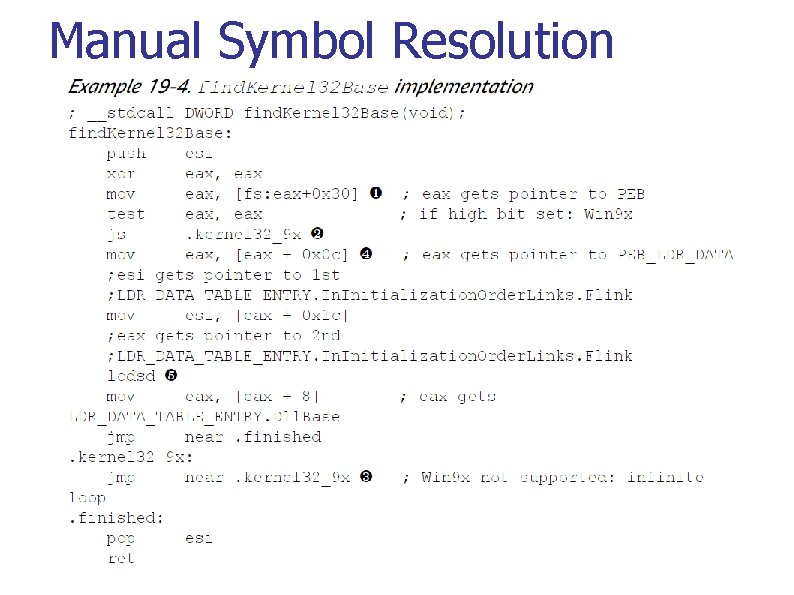

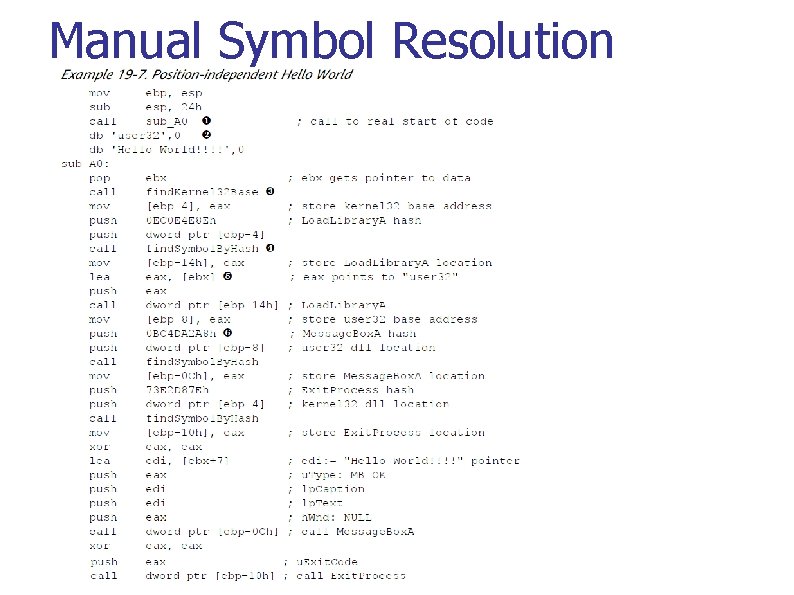

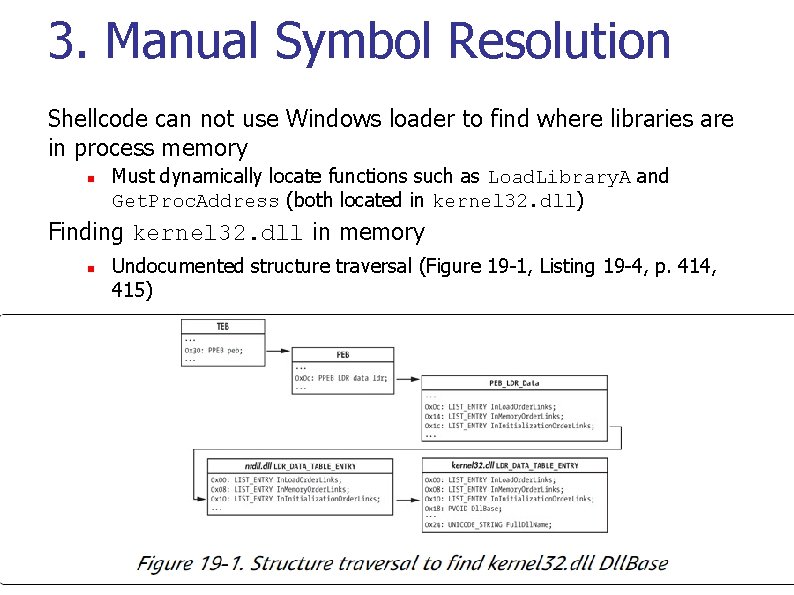

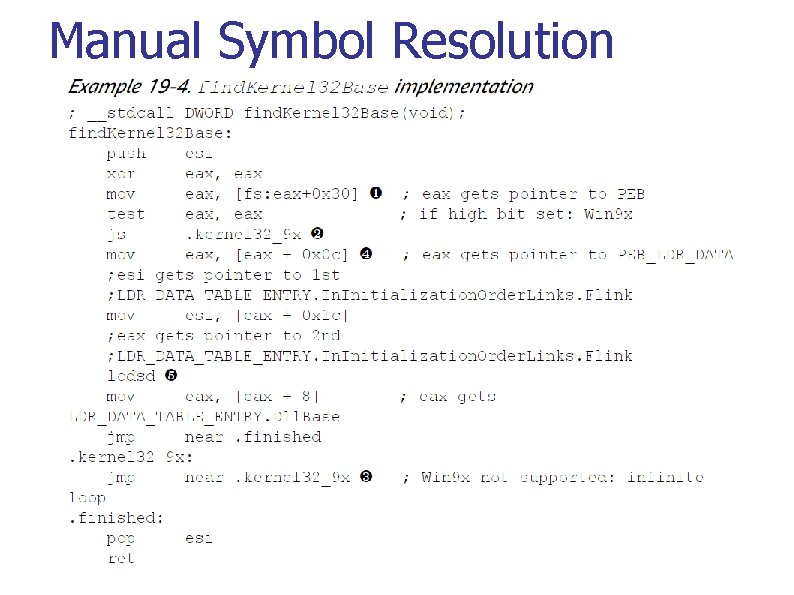

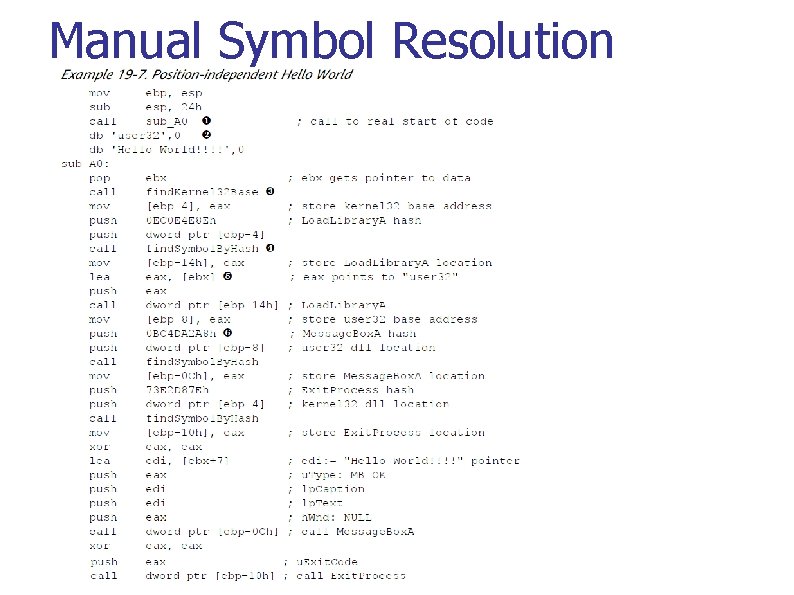

3. Manual Symbol Resolution Shellcode can not use Windows loader to find where libraries are in process memory n Must dynamically locate functions such as Load. Library. A and Get. Proc. Address (both located in kernel 32. dll) Finding kernel 32. dll in memory n Undocumented structure traversal (Figure 19 -1, Listing 19 -4, p. 414, 415)

Manual Symbol Resolution

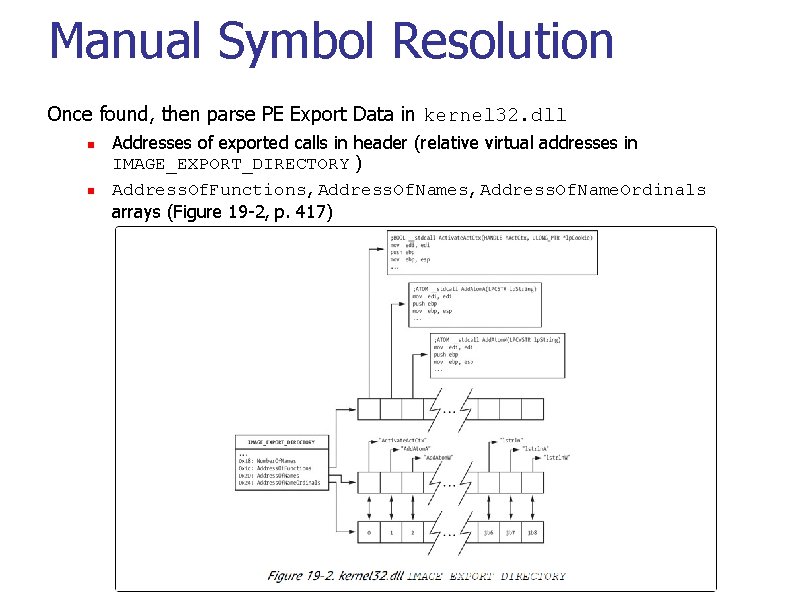

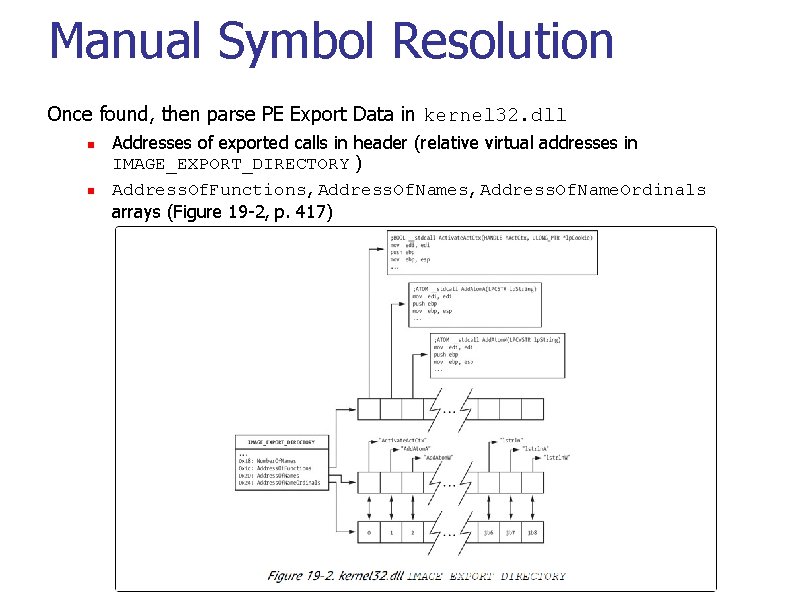

Manual Symbol Resolution Once found, then parse PE Export Data in kernel 32. dll n n Addresses of exported calls in header (relative virtual addresses in IMAGE_EXPORT_DIRECTORY ) Address. Of. Functions, Address. Of. Name. Ordinals arrays (Figure 19 -2, p. 417)

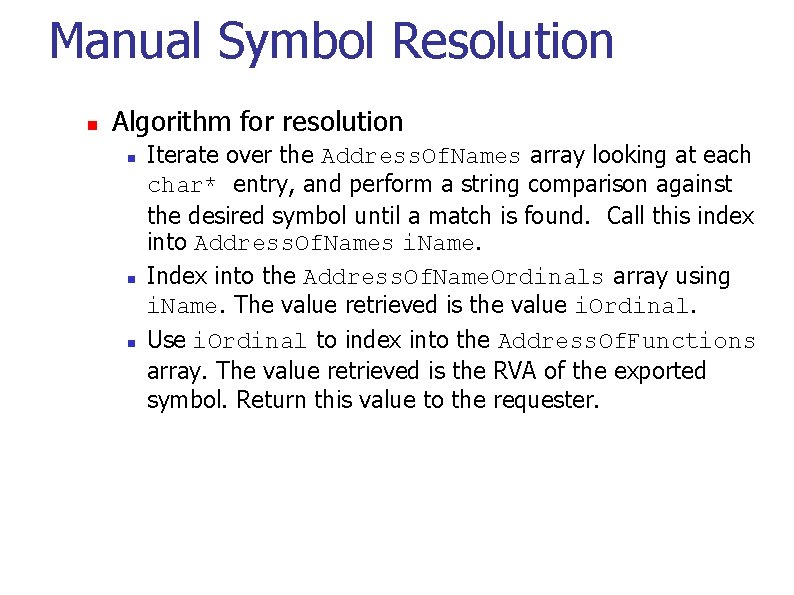

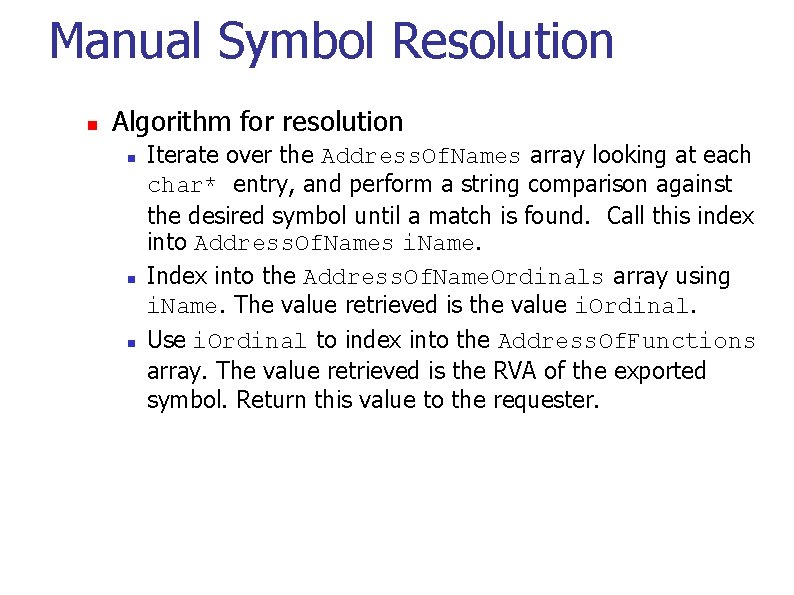

Manual Symbol Resolution n Algorithm for resolution n Iterate over the Address. Of. Names array looking at each char* entry, and perform a string comparison against the desired symbol until a match is found. Call this index into Address. Of. Names i. Name. Index into the Address. Of. Name. Ordinals array using i. Name. The value retrieved is the value i. Ordinal. Use i. Ordinal to index into the Address. Of. Functions array. The value retrieved is the RVA of the exported symbol. Return this value to the requester.

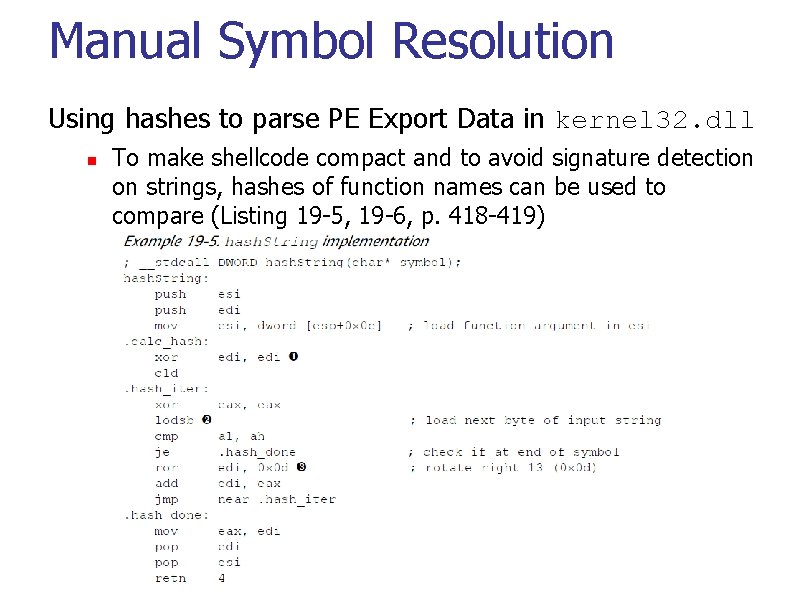

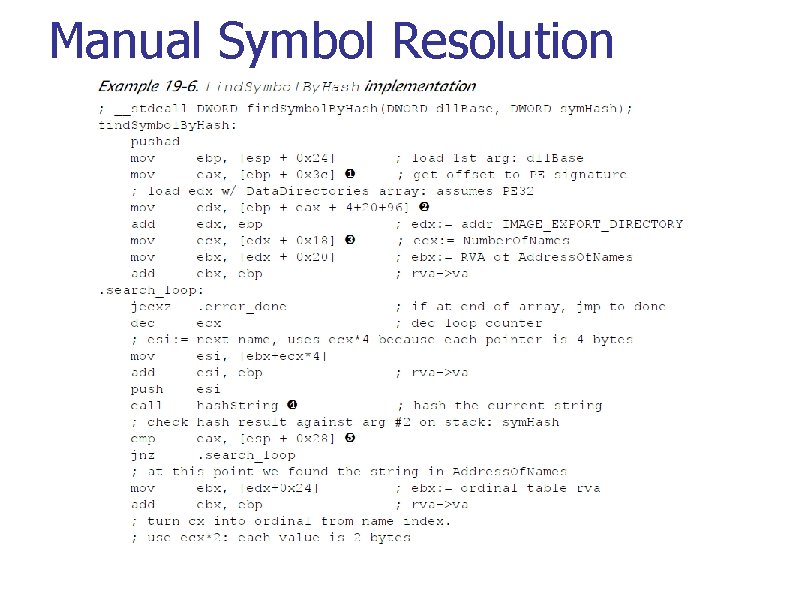

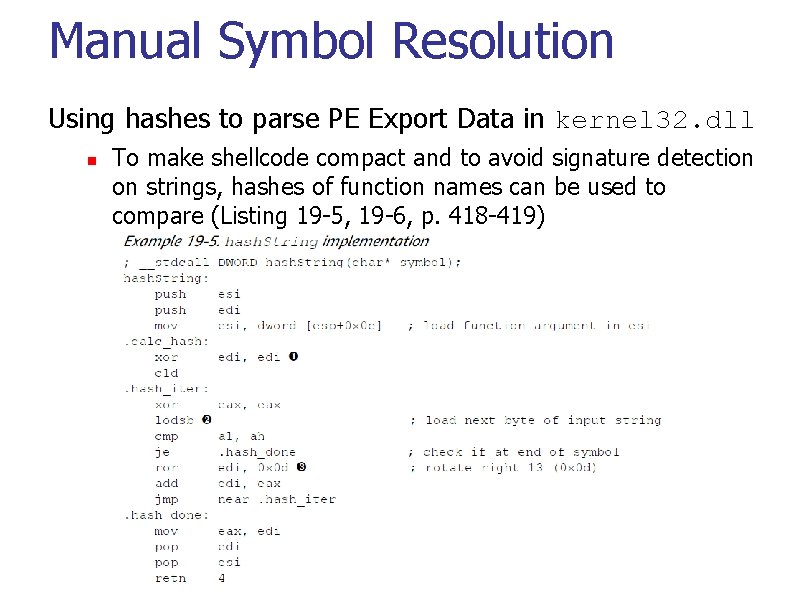

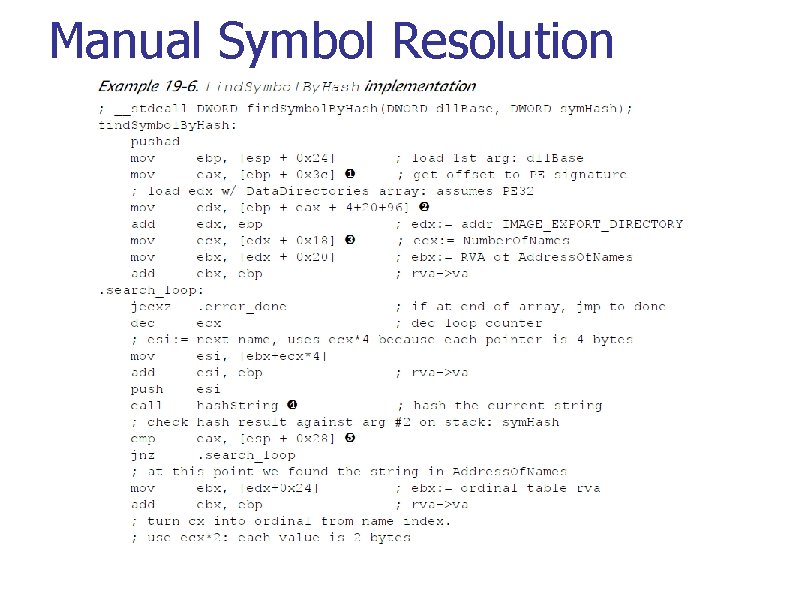

Manual Symbol Resolution Using hashes to parse PE Export Data in kernel 32. dll n To make shellcode compact and to avoid signature detection on strings, hashes of function names can be used to compare (Listing 19 -5, 19 -6, p. 418 -419)

Manual Symbol Resolution

Manual Symbol Resolution

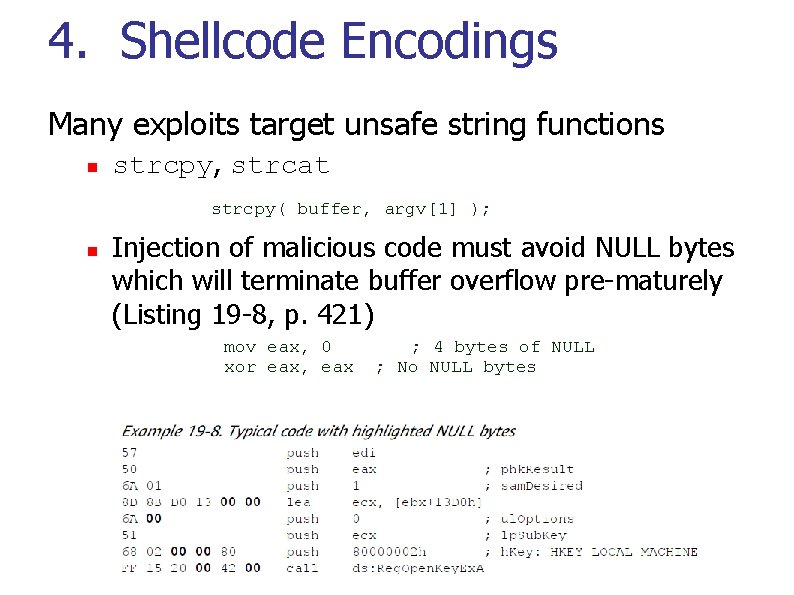

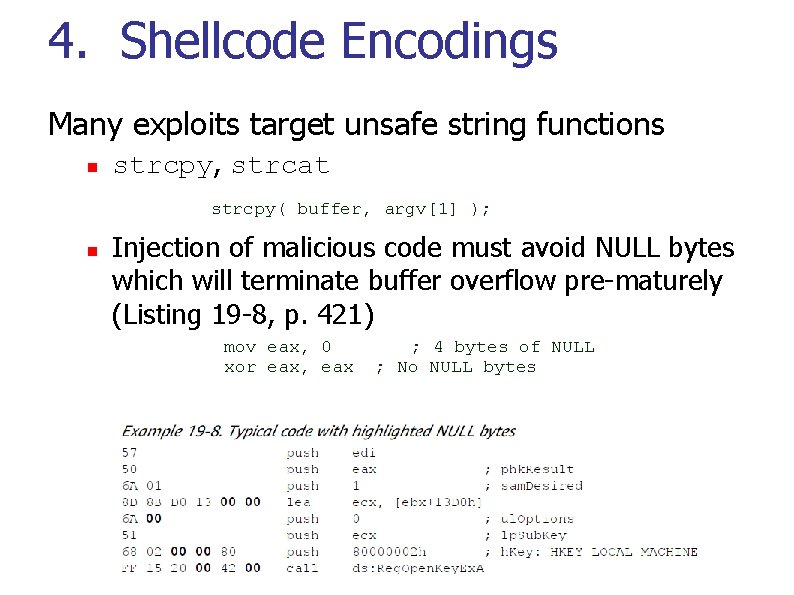

4. Shellcode Encodings Many exploits target unsafe string functions n strcpy, strcat strcpy( buffer, argv[1] ); n Injection of malicious code must avoid NULL bytes which will terminate buffer overflow pre-maturely (Listing 19 -8, p. 421) mov eax, 0 xor eax, eax ; 4 bytes of NULL ; No NULL bytes

Shellcode Encodings ASCII armor n n Hardens against buffer overflow If exploit requires injection of addresses, then force addresses to include NULL by putting all code/data within ASCII armor at beginning of address space

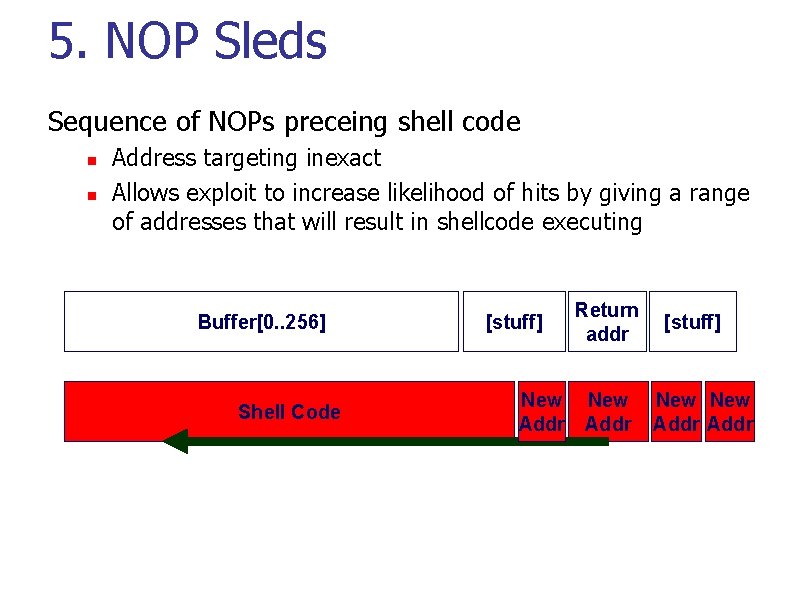

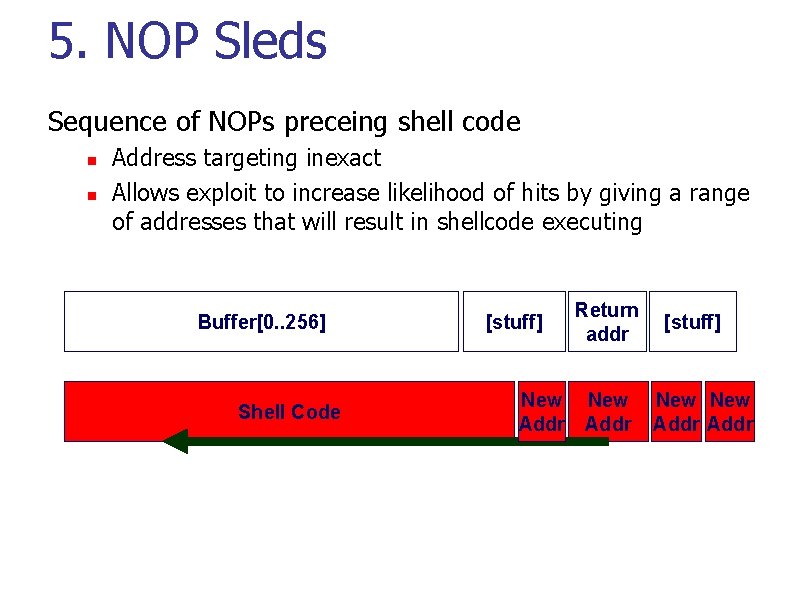

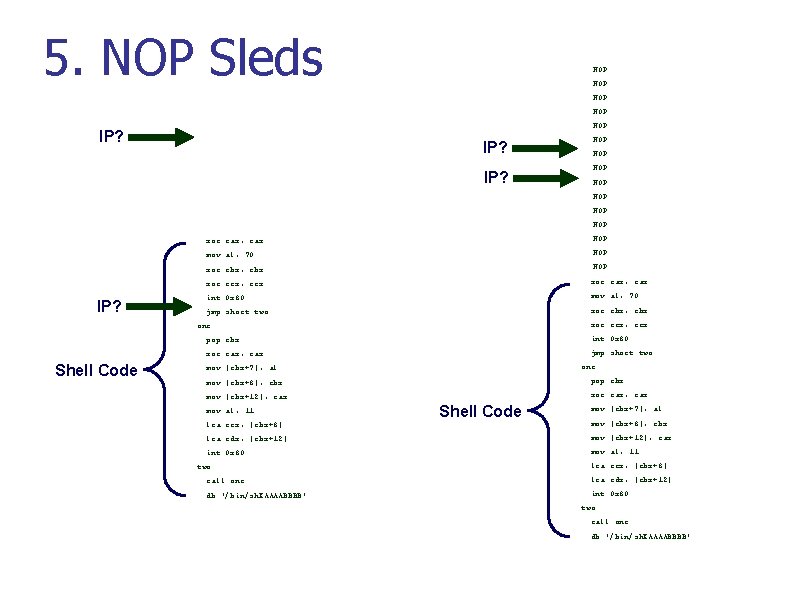

5. NOP Sleds Sequence of NOPs preceing shell code n n Address targeting inexact Allows exploit to increase likelihood of hits by giving a range of addresses that will result in shellcode executing Buffer[0. . 256] Shell Code [stuff] Return addr New Addr [stuff] New Addr

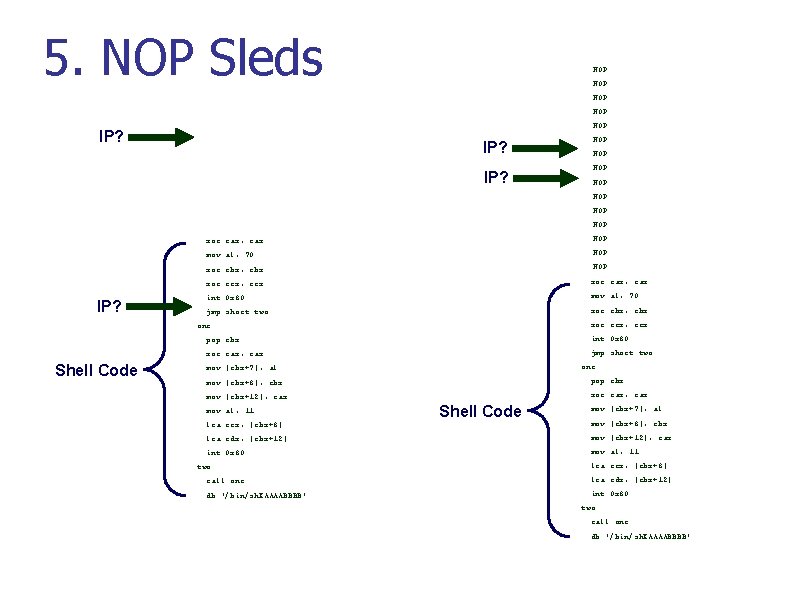

5. NOP Sleds NOP NOP NOP IP? IP? NOP NOP IP? xor eax, eax NOP mov al, 70 NOP xor ebx, ebx NOP xor ecx, ecx xor eax, eax int 0 x 80 mov al, 70 jmp short two xor ebx, ebx xor ecx, ecx one: Shell Code pop ebx int 0 x 80 xor eax, eax jmp short two one: mov [ebx+7], al mov [ebx+8], ebx pop ebx mov [ebx+12], eax xor eax, eax mov al, 11 Shell Code mov [ebx+7], al lea ecx, [ebx+8] mov [ebx+8], ebx lea edx, [ebx+12] mov [ebx+12], eax int 0 x 80 mov al, 11 two: call one db '/bin/sh. XAAAABBBB' lea ecx, [ebx+8] lea edx, [ebx+12] int 0 x 80 two: call one db '/bin/sh. XAAAABBBB'

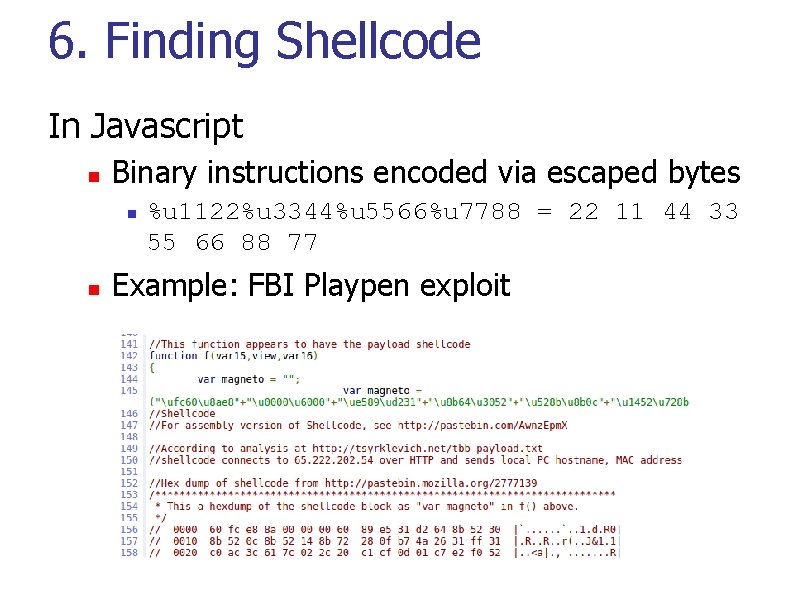

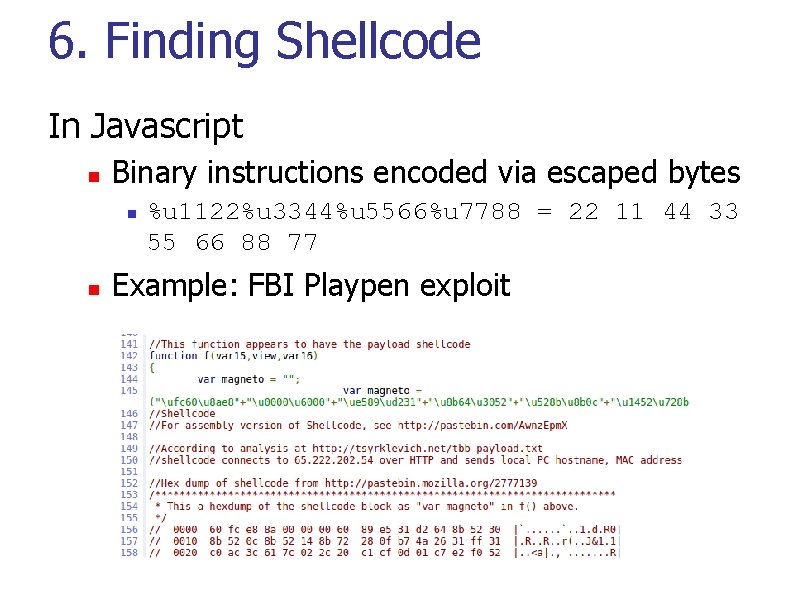

6. Finding Shellcode In Javascript n Binary instructions encoded via escaped bytes n n %u 1122%u 3344%u 5566%u 7788 = 22 11 44 33 55 66 88 77 Example: FBI Playpen exploit

6. Finding Shellcode In payloads n n Common API calls (Virtual. Alloc. Ex, Write. Process. Memory, Create. Remote. Thread) Common opcodes (Call, Unconditional jumps, Loops, Short conditional jumps)

Chapter 20: C++ Analysis

C++ Analysis 1. Object-Oriented Programming 2. Virtual vs. Nonvirtual Functions 3. Creating and Destroying Objects

1. Object-Oriented Programming Functions (i. e. methods) in C++ associated with particular classes of objects n n Classes used to define objects Similar to struct, but also include functions “this” pointer n n n Implicit pointer to object that holds the variable being accessed Implied in every variable access within a function that does not specify an object Passed as a compiler-generated parameter to a function (typically the ECX register, sometimes ESI) “thiscall” calling convention (compared to stdcall, cdecl, and fastcalling conventions) Listing 20 -2, Listing 20 -3, p. 429, 430 n n 3) loads this pointer into ecx 4) puts ecx into eax, then access x to compare it to 10

Object-Oriented Programming Overloading and Mangling n n Method overloading allows multiple functions to have same name, but accept different parameters When function called, compiler determines which version to use (Listing 20 -4, p. 431) C++ uses name mangling to support this construct in the PE file Algorithm for mangling is compiler-specific n IDA Pro demangles based on what it knows about specific compilers (Figure 20 -1, p. 431) ? Test. Function@Simple. Class@@QAEXHH@Z public: void __thiscall Simple. Class: : Test. Function(int, int) n Can use c++filt on linux (CTF level? ) mashimaro <~> f() 9: 19 AM % c++filt -n _Z 1 fv

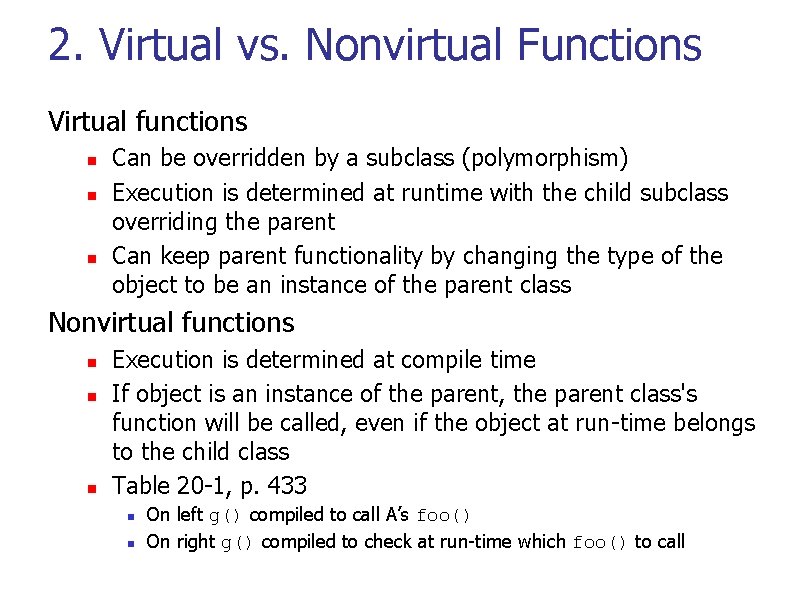

2. Virtual vs. Nonvirtual Functions Virtual functions n n n Can be overridden by a subclass (polymorphism) Execution is determined at runtime with the child subclass overriding the parent Can keep parent functionality by changing the type of the object to be an instance of the parent class Nonvirtual functions n n n Execution is determined at compile time If object is an instance of the parent, the parent class's function will be called, even if the object at run-time belongs to the child class Table 20 -1, p. 433 n n On left g() compiled to call A’s foo() On right g() compiled to check at run-time which foo() to call

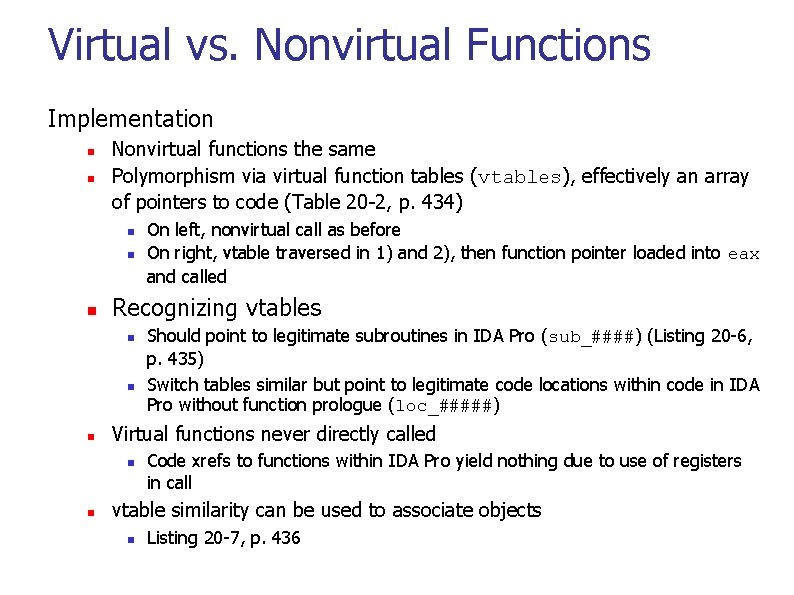

Virtual vs. Nonvirtual Functions Implementation n n Nonvirtual functions the same Polymorphism via virtual function tables (vtables), effectively an array of pointers to code (Table 20 -2, p. 434) n n n Recognizing vtables n n n Should point to legitimate subroutines in IDA Pro (sub_####) (Listing 20 -6, p. 435) Switch tables similar but point to legitimate code locations within code in IDA Pro without function prologue (loc_#####) Virtual functions never directly called n n On left, nonvirtual call as before On right, vtable traversed in 1) and 2), then function pointer loaded into eax and called Code xrefs to functions within IDA Pro yield nothing due to use of registers in call vtable similarity can be used to associate objects n Listing 20 -7, p. 436

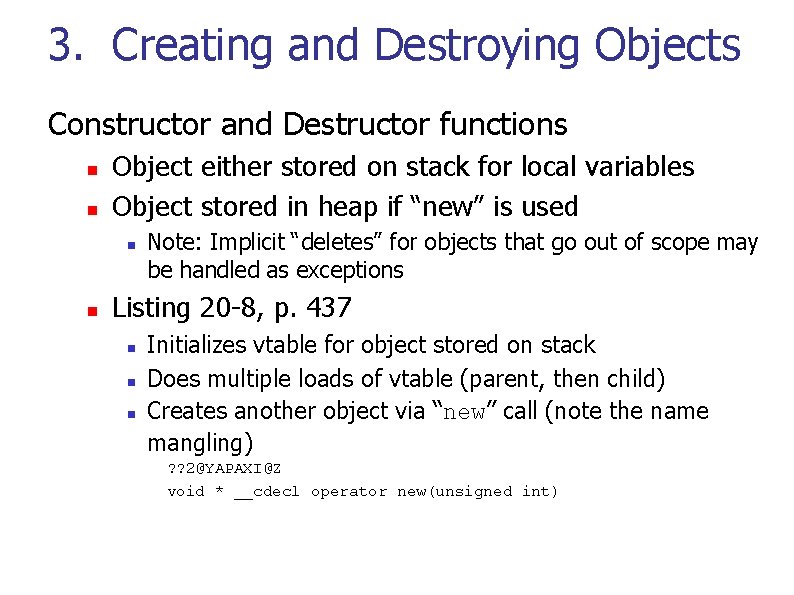

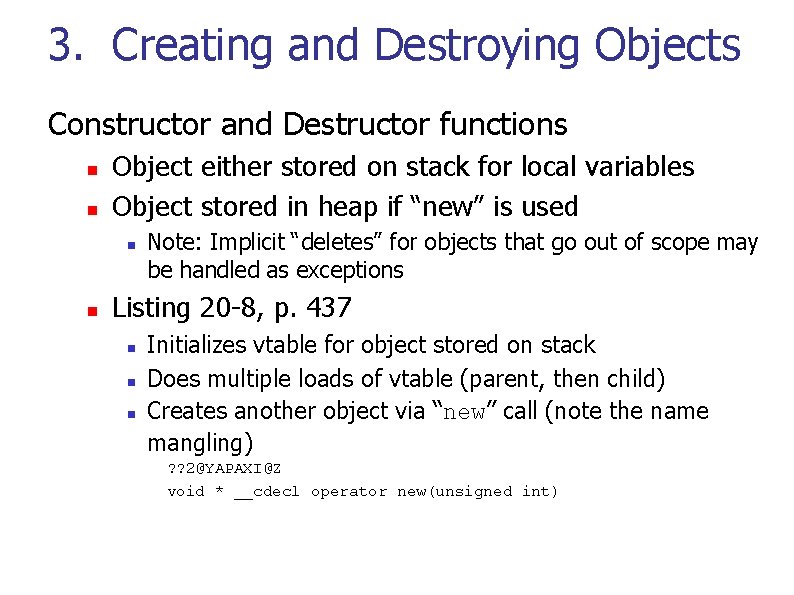

3. Creating and Destroying Objects Constructor and Destructor functions n n Object either stored on stack for local variables Object stored in heap if “new” is used n n Note: Implicit “deletes” for objects that go out of scope may be handled as exceptions Listing 20 -8, p. 437 n n n Initializes vtable for object stored on stack Does multiple loads of vtable (parent, then child) Creates another object via “new” call (note the name mangling) ? ? 2@YAPAXI@Z void * __cdecl operator new(unsigned int)

In-class exercise Lab 20 -1

Chapter 21: 64 -bit Malware

64 -bit Malware 1. Why 64 -bit Malware? 2. Differences in x 64 architectures 3. Windows 32 -Bit on Windows 64 -Bit 4. 64 -Bit Hints at Malware Functionality

1. Why 64 -bit Malware? AMD 64 now known as x 64 or x 86 -64 n n n Similar to 32 -bit x 86 with quad extensions Not all tools support it Backwards compatibility support for 32 -bit ensures that 32 -bit malware can run on both 32 -bit and 64 bit machines Reasons for 64 -bit malware n n Kernel rootkits must be 64 -bit for machines to run on a 64 -bit OS Malware and shellcode being injected into a 64 -bit process must be 64 -bit

2. Differences in x 64 Architecture 64 -bit vs. 32 -bit x 86 n n All addresses and pointers 64 -bit All general purpose registers 64 -bit (%rax vs. %eax) Special purpose registers also 64 -bit (%rip vs. %eip) Double the general purpose registers (%r 8 -%r 15) n n %r 8 = 64 -bits %r 8 d = 32 -bit DWORD %r 8 w = 16 -bit WORD %r 8 l = 8 -bit LOW byte

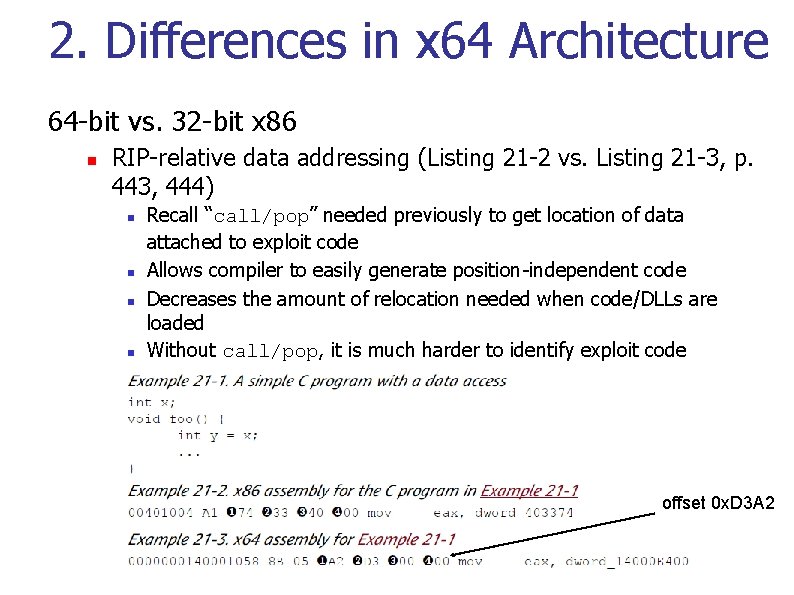

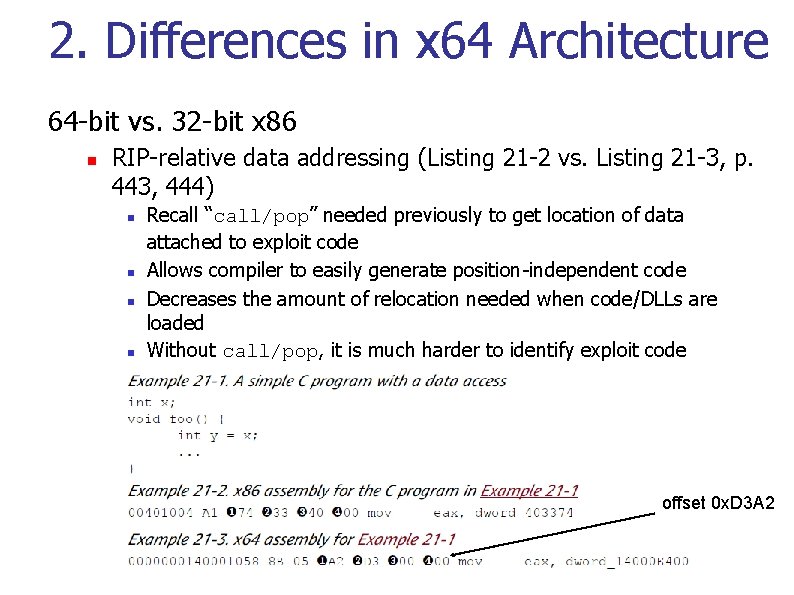

2. Differences in x 64 Architecture 64 -bit vs. 32 -bit x 86 n RIP-relative data addressing (Listing 21 -2 vs. Listing 21 -3, p. 443, 444) n n Recall “call/pop” needed previously to get location of data attached to exploit code Allows compiler to easily generate position-independent code Decreases the amount of relocation needed when code/DLLs are loaded Without call/pop, it is much harder to identify exploit code offset 0 x. D 3 A 2

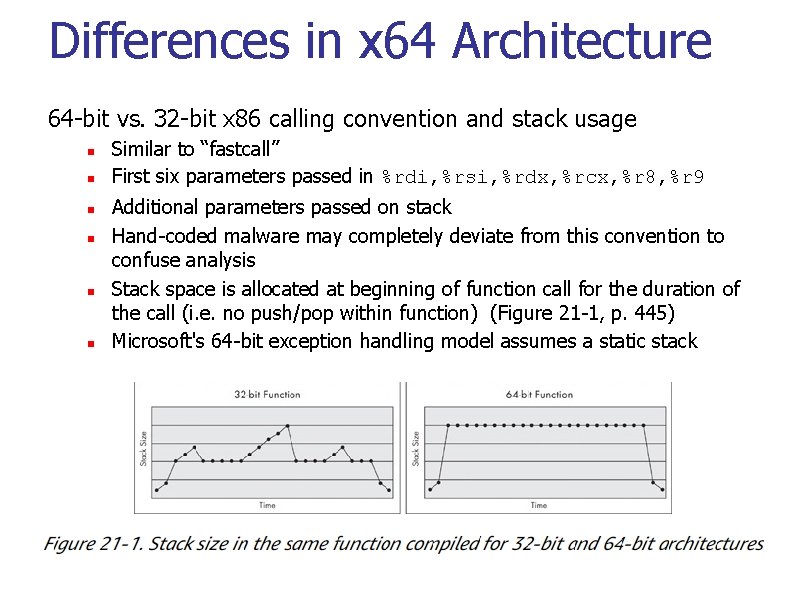

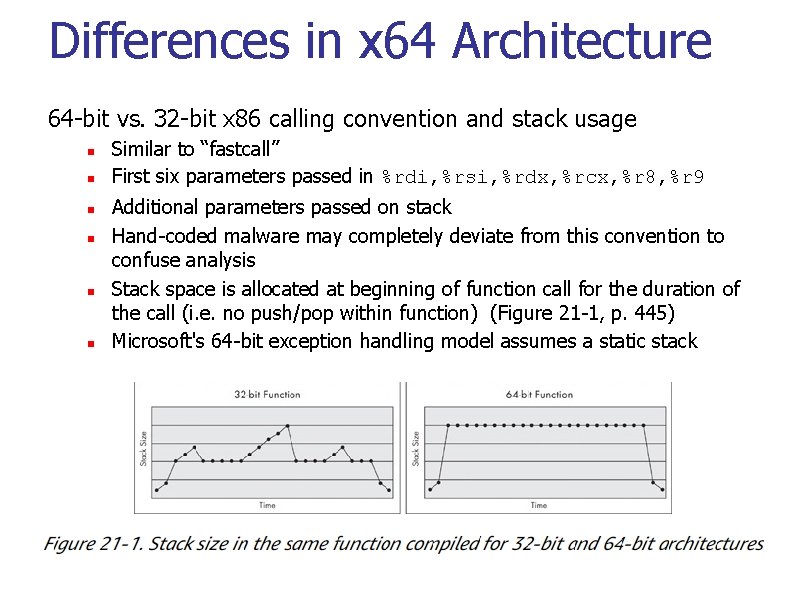

Differences in x 64 Architecture 64 -bit vs. 32 -bit x 86 calling convention and stack usage n n n Similar to “fastcall” First six parameters passed in %rdi, %rsi, %rdx, %rcx, %r 8, %r 9 Additional parameters passed on stack Hand-coded malware may completely deviate from this convention to confuse analysis Stack space is allocated at beginning of function call for the duration of the call (i. e. no push/pop within function) (Figure 21 -1, p. 445) Microsoft's 64 -bit exception handling model assumes a static stack

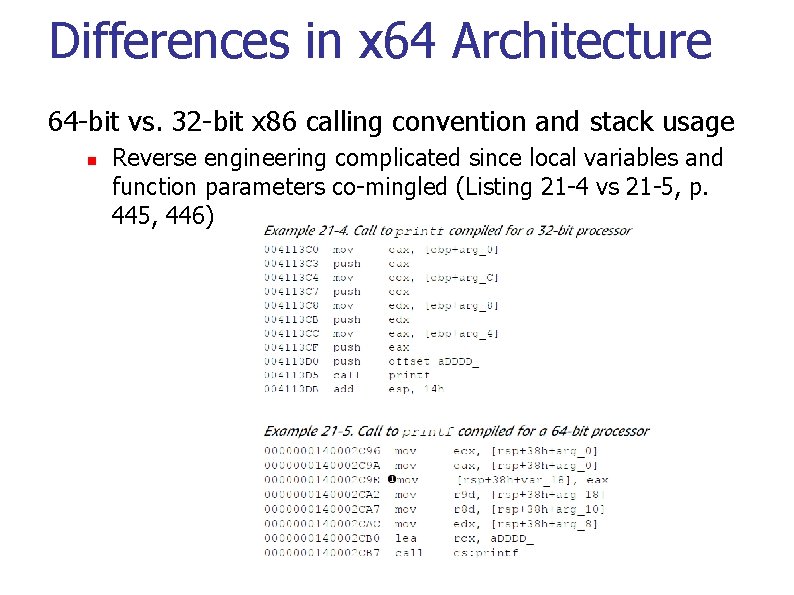

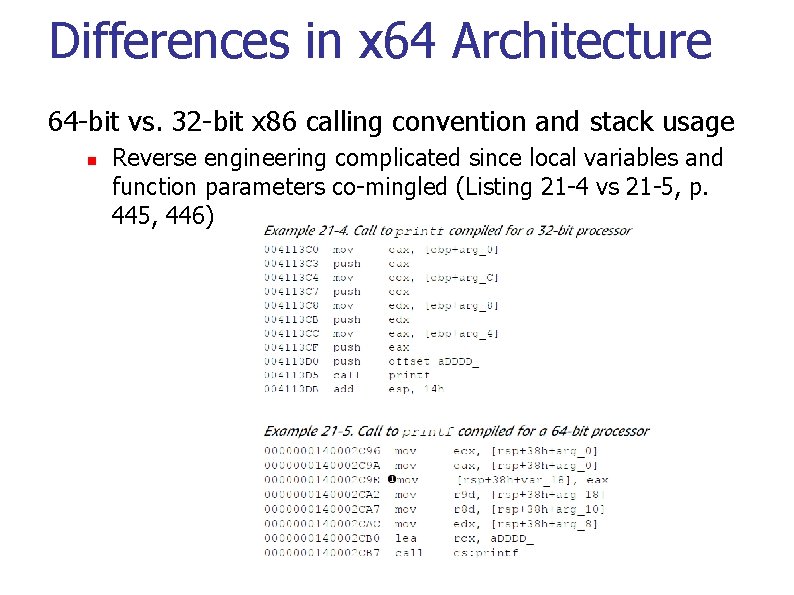

Differences in x 64 Architecture 64 -bit vs. 32 -bit x 86 calling convention and stack usage n Reverse engineering complicated since local variables and function parameters co-mingled (Listing 21 -4 vs 21 -5, p. 445, 446)

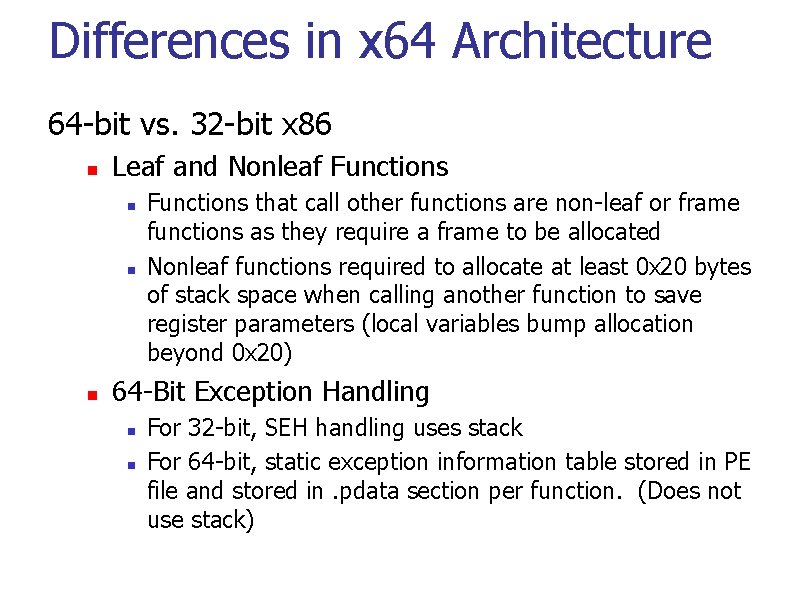

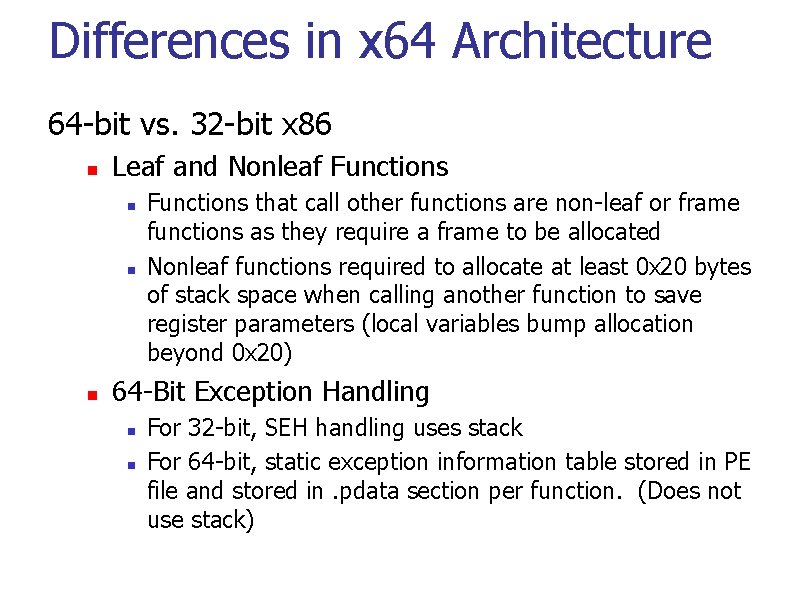

Differences in x 64 Architecture 64 -bit vs. 32 -bit x 86 n Leaf and Nonleaf Functions n n n Functions that call other functions are non-leaf or frame functions as they require a frame to be allocated Nonleaf functions required to allocate at least 0 x 20 bytes of stack space when calling another function to save register parameters (local variables bump allocation beyond 0 x 20) 64 -Bit Exception Handling n n For 32 -bit, SEH handling uses stack For 64 -bit, static exception information table stored in PE file and stored in. pdata section per function. (Does not use stack)

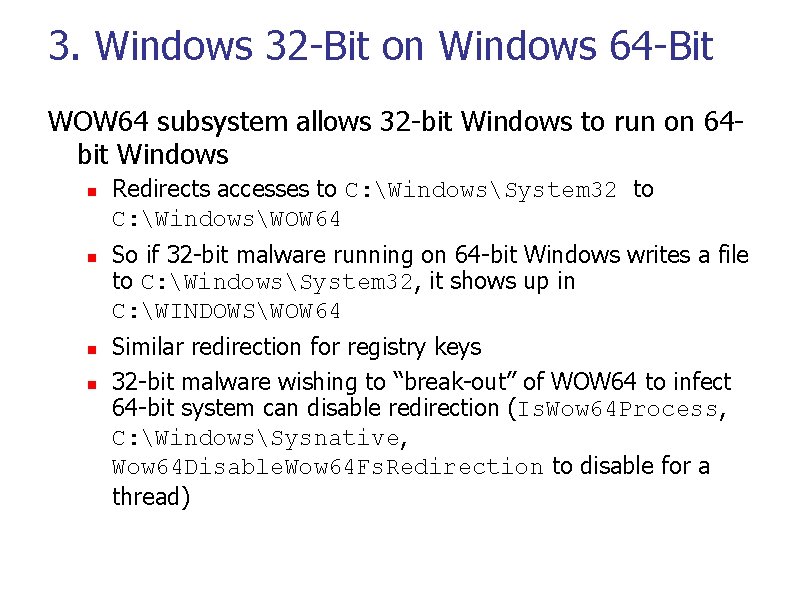

3. Windows 32 -Bit on Windows 64 -Bit WOW 64 subsystem allows 32 -bit Windows to run on 64 bit Windows n n Redirects accesses to C: WindowsSystem 32 to C: WindowsWOW 64 So if 32 -bit malware running on 64 -bit Windows writes a file to C: WindowsSystem 32, it shows up in C: WINDOWSWOW 64 Similar redirection for registry keys 32 -bit malware wishing to “break-out” of WOW 64 to infect 64 -bit system can disable redirection (Is. Wow 64 Process, C: WindowsSysnative, Wow 64 Disable. Wow 64 Fs. Redirection to disable for a thread)

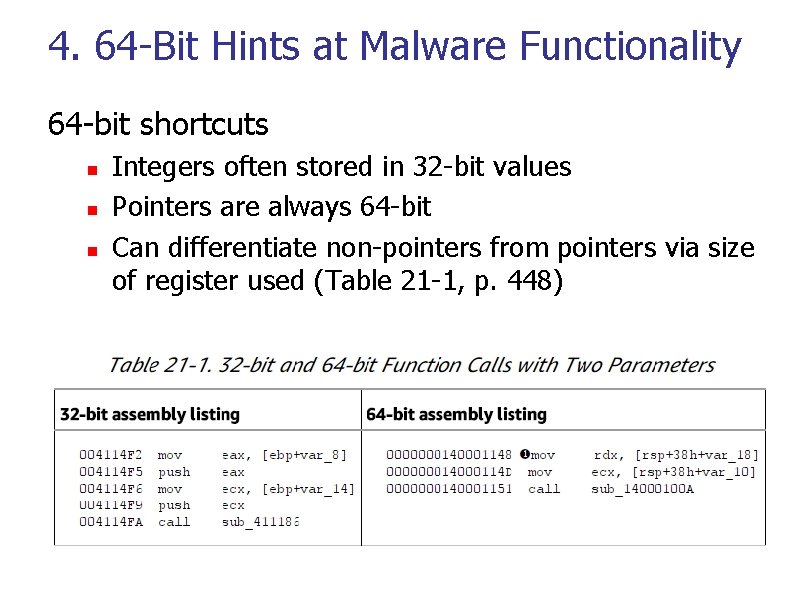

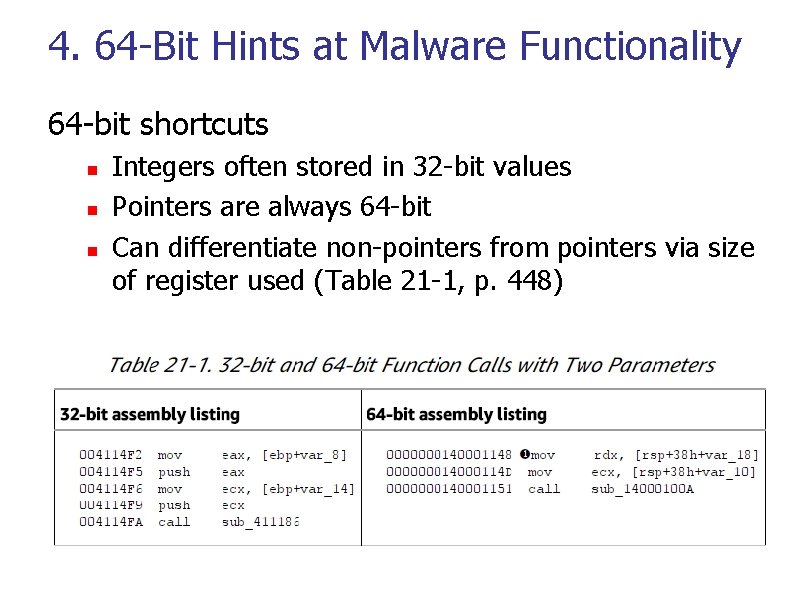

4. 64 -Bit Hints at Malware Functionality 64 -bit shortcuts n n n Integers often stored in 32 -bit values Pointers are always 64 -bit Can differentiate non-pointers from pointers via size of register used (Table 21 -1, p. 448)

Extra

Machine learning in malware n Polymorphic malware difficult to catch with signatures n n After unpacking, shares common functions Can use RCE to identify features to use in an ML model n n Humans (you) decide labels of good and bad Humans (you) decide features that are helpful or not Example: Cylance (End Point See) Issue n n n Difficult to get explainability out of results What if polymorphic game code gets flagged? Can one reason about what ML algorithm is doing?