Parsing Odds and Ends Lecture 14 P N

- Slides: 31

Parsing Odds and Ends Lecture 14 (P. N. Hilfinger, plus slides adapted from R. Bodik) 9/27/2006 Prof. Hilfinger, Lecture 14 1

Administrivia • Trial run of project autograder on Wednesday night (sometime). No other runs until Friday. 9/27/2006 Prof. Hilfinger, Lecture 14 2

Topics • Syntax-directed translation and LR parsing • Syntax-directed translation and recursive descent • Dealing with errors in LR parsing: quick and dirty approach 9/27/2006 Prof. Hilfinger, Lecture 14 3

Syntax-Directed Translation and LR Parsing • Idea: Add semantic stack, parallel to the parsing stack: – each symbol (terminal or non-terminal) on the parsing stack stores its value on the semantic stack – each reduction uses the values at the top of the stack to compute the new value to be associated with the symbol that’s produced – when the parse is finished, the semantic stack will hold just one value: the translation of the root non-terminal, which is the translation of the whole input. 9/27/2006 Prof. Hilfinger, Lecture 14 4

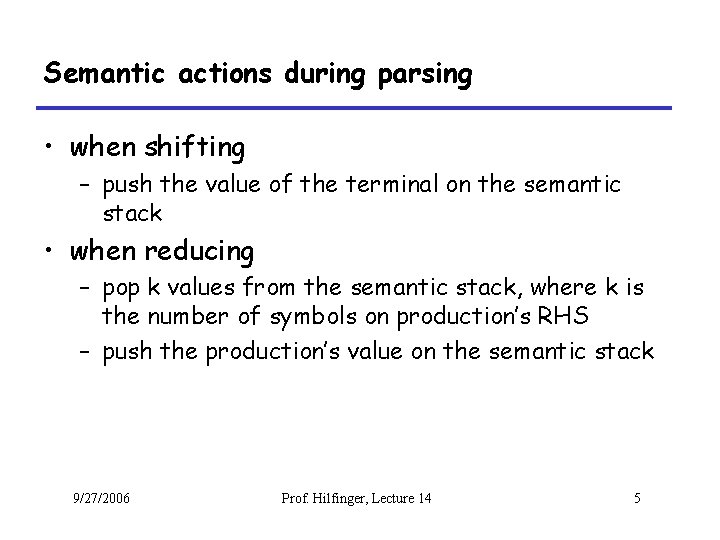

Semantic actions during parsing • when shifting – push the value of the terminal on the semantic stack • when reducing – pop k values from the semantic stack, where k is the number of symbols on production’s RHS – push the production’s value on the semantic stack 9/27/2006 Prof. Hilfinger, Lecture 14 5

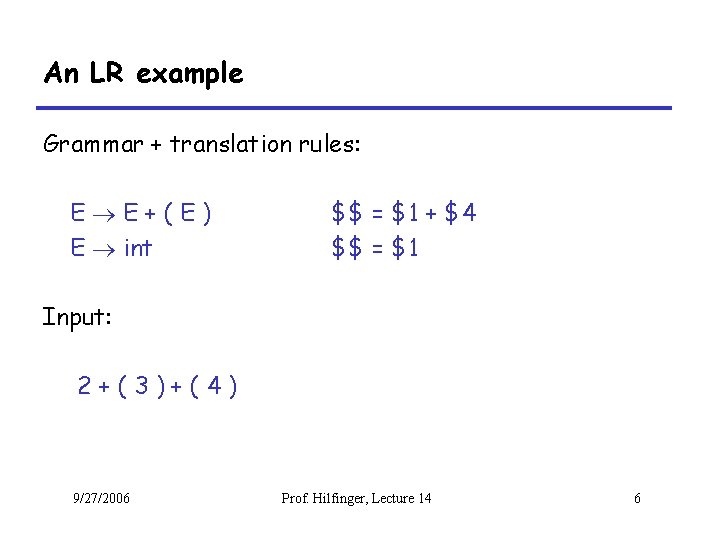

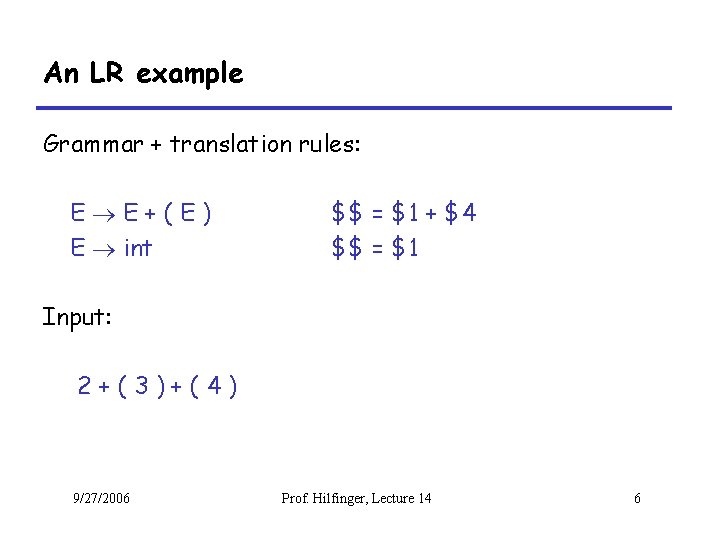

An LR example Grammar + translation rules: E E+(E) E int $$ = $1 + $4 $$ = $1 Input: 2+(3)+(4) 9/27/2006 Prof. Hilfinger, Lecture 14 6

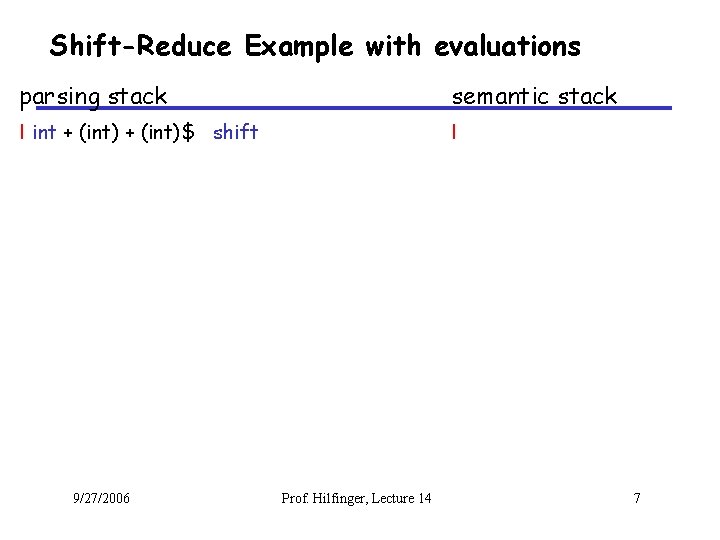

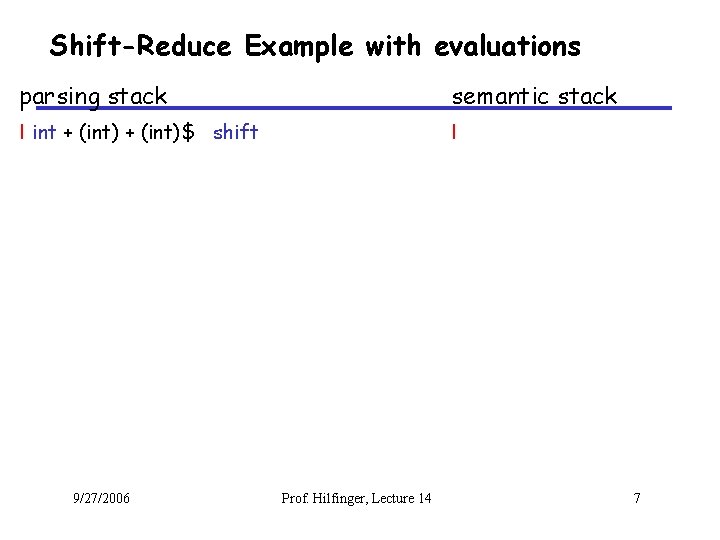

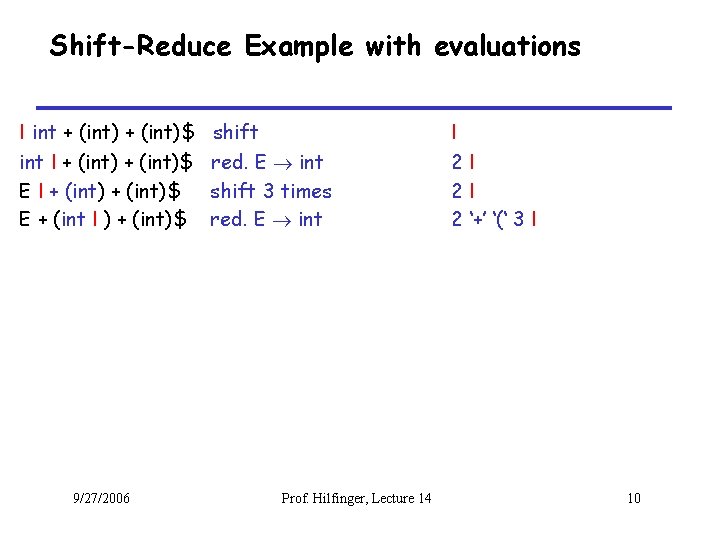

Shift-Reduce Example with evaluations parsing stack semantic stack I int + (int)$ shift I 9/27/2006 Prof. Hilfinger, Lecture 14 7

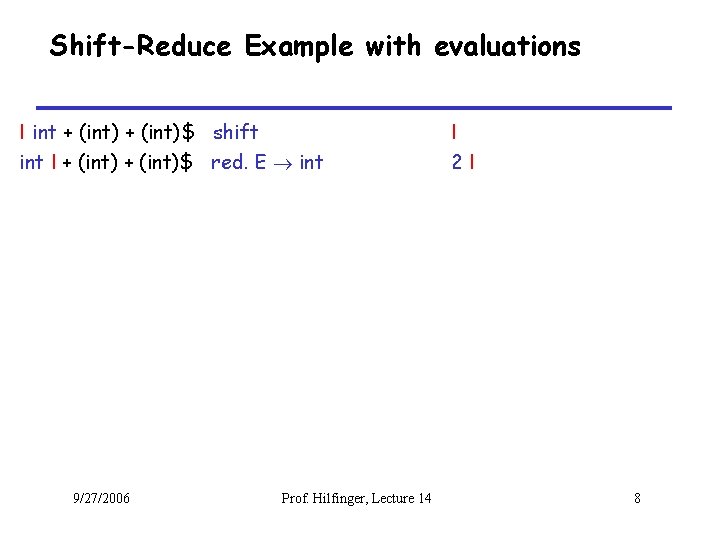

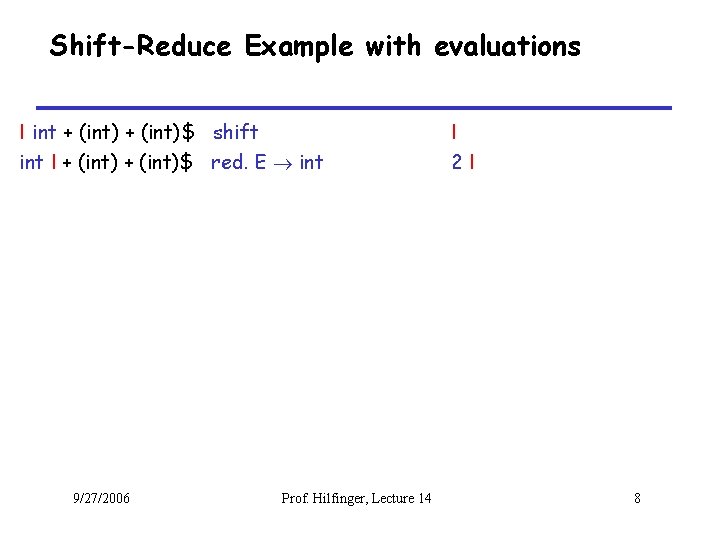

Shift-Reduce Example with evaluations I int + (int)$ shift int I + (int)$ red. E int 9/27/2006 Prof. Hilfinger, Lecture 14 I 2 I 8

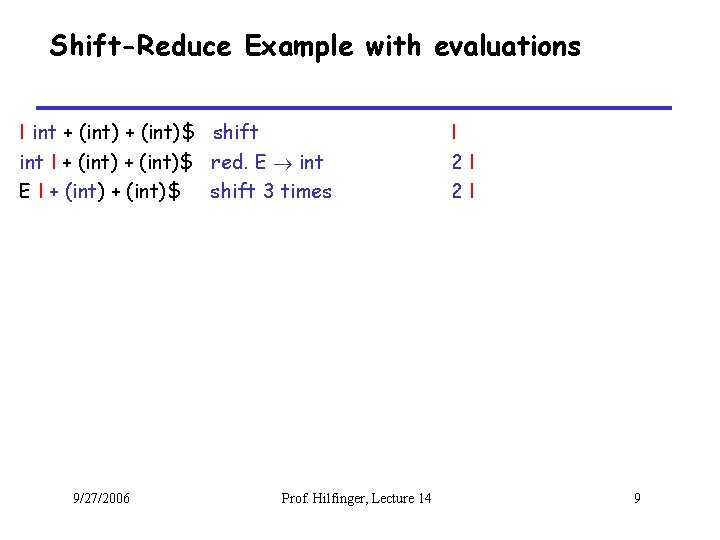

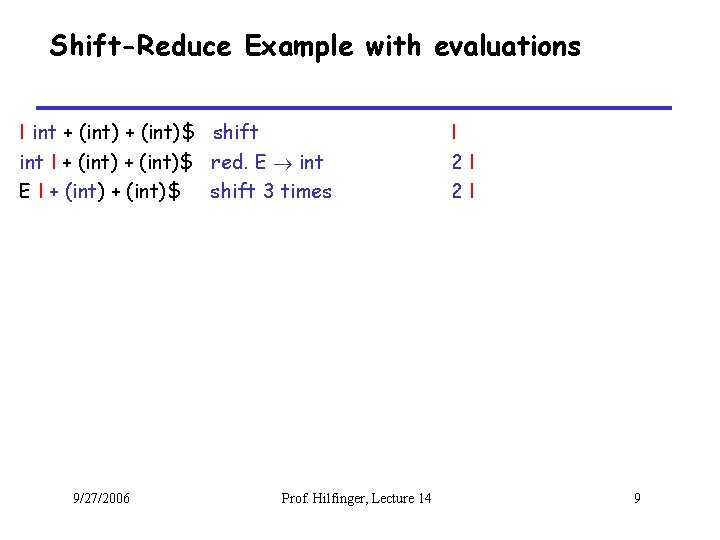

Shift-Reduce Example with evaluations I int + (int)$ shift int I + (int)$ red. E int E I + (int)$ shift 3 times 9/27/2006 Prof. Hilfinger, Lecture 14 I 2 I 2 I 9

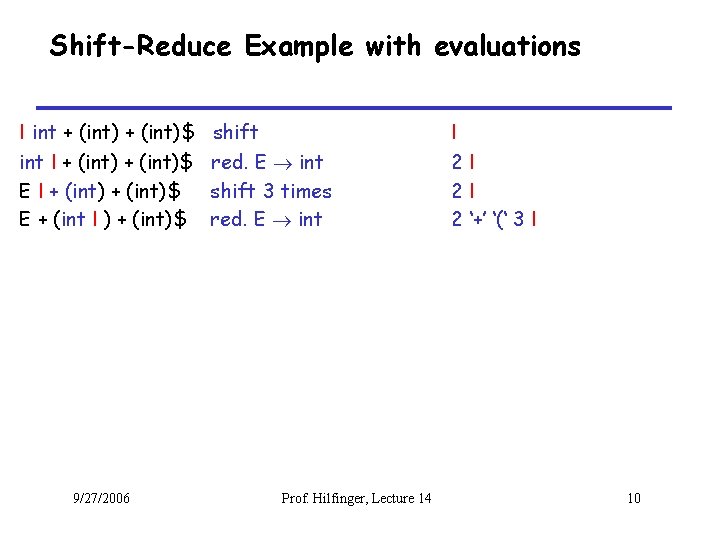

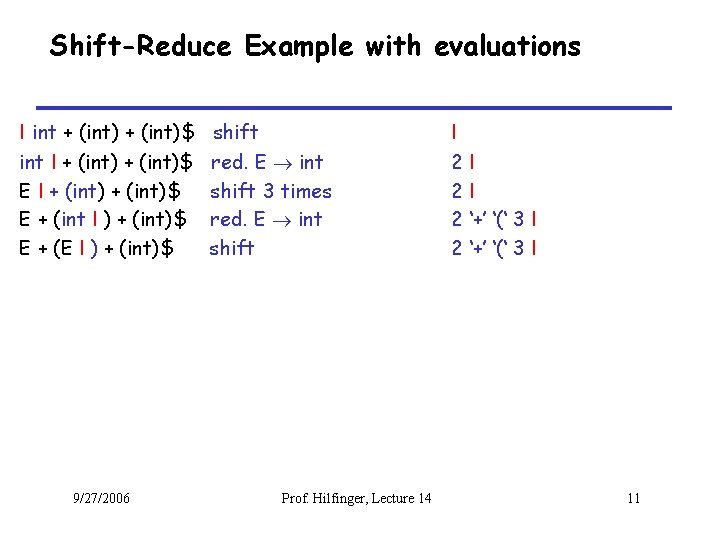

Shift-Reduce Example with evaluations I int + (int)$ int I + (int)$ E + (int I ) + (int)$ 9/27/2006 shift red. E int shift 3 times red. E int Prof. Hilfinger, Lecture 14 I 2 I 2 I 2 ‘+’ ‘(‘ 3 I 10

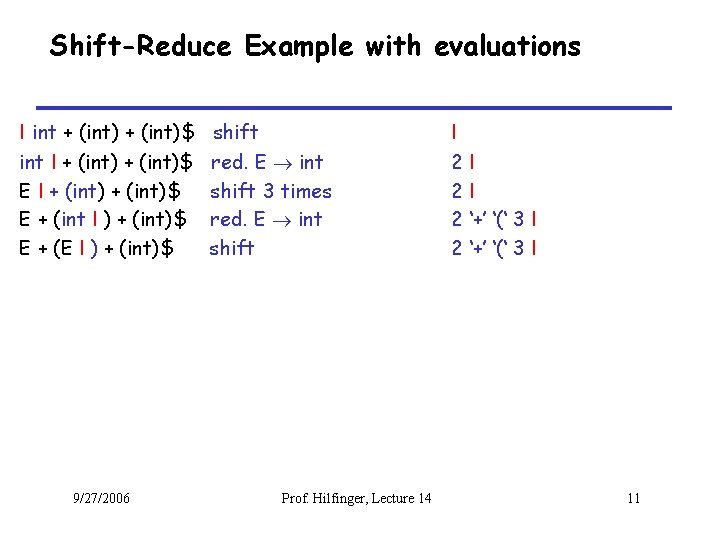

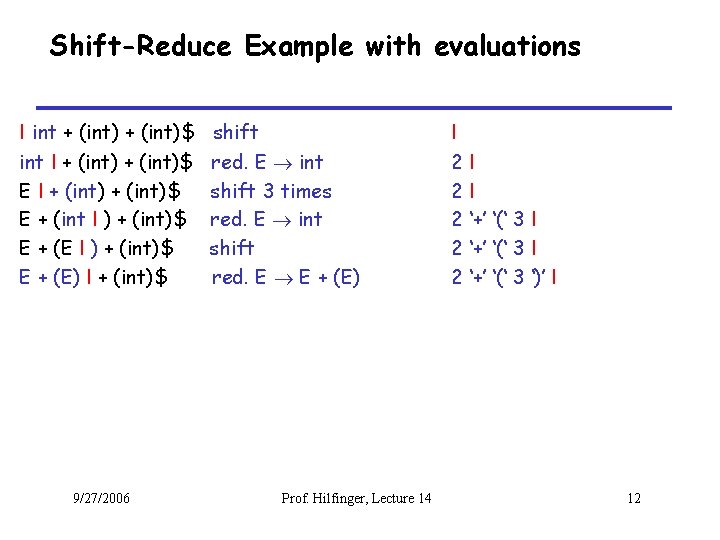

Shift-Reduce Example with evaluations I int + (int)$ int I + (int)$ E + (int I ) + (int)$ E + (E I ) + (int)$ 9/27/2006 shift red. E int shift 3 times red. E int shift Prof. Hilfinger, Lecture 14 I 2 I 2 I 2 ‘+’ ‘(‘ 3 I 11

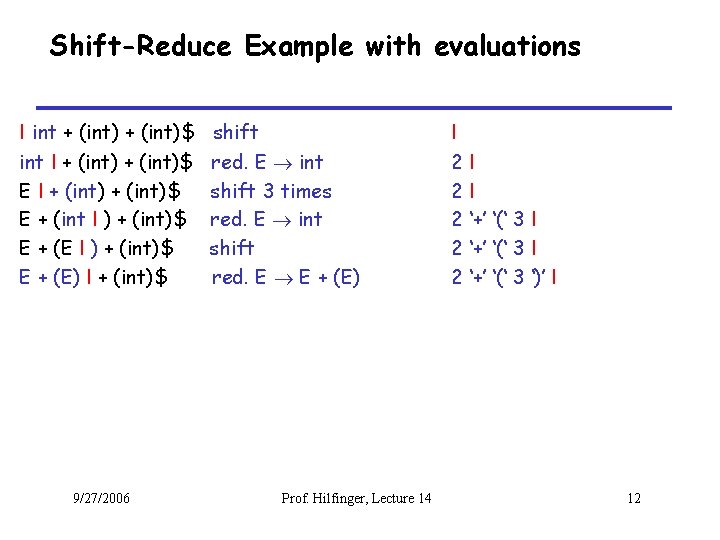

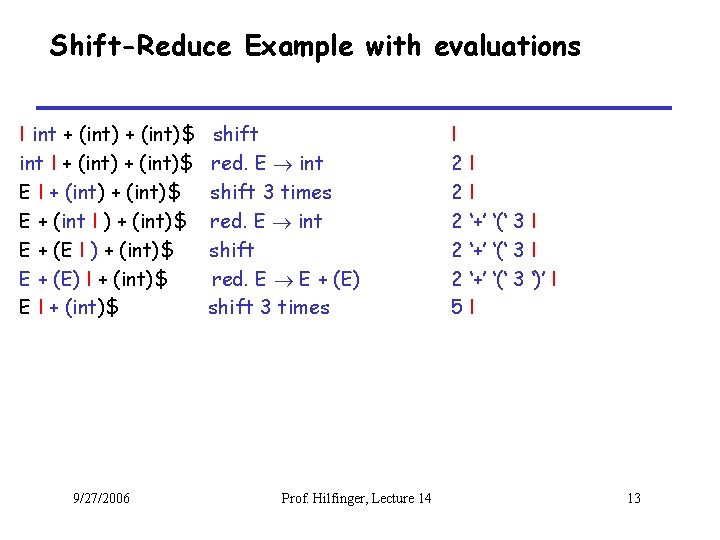

Shift-Reduce Example with evaluations I int + (int)$ int I + (int)$ E + (int I ) + (int)$ E + (E) I + (int)$ 9/27/2006 shift red. E int shift 3 times red. E int shift red. E E + (E) Prof. Hilfinger, Lecture 14 I 2 I 2 I 2 ‘+’ ‘(‘ 3 ‘)’ I 12

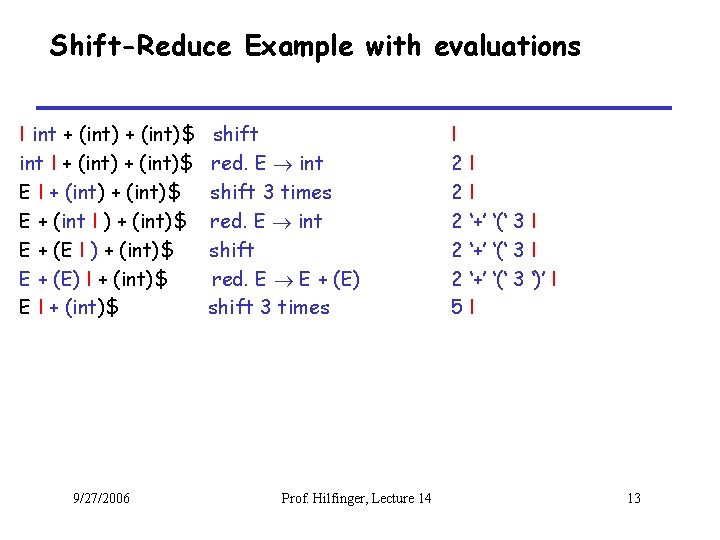

Shift-Reduce Example with evaluations I int + (int)$ int I + (int)$ E + (int I ) + (int)$ E + (E) I + (int)$ E I + (int)$ 9/27/2006 shift red. E int shift 3 times red. E int shift red. E E + (E) shift 3 times Prof. Hilfinger, Lecture 14 I 2 I 2 I 2 ‘+’ ‘(‘ 3 ‘)’ I 5 I 13

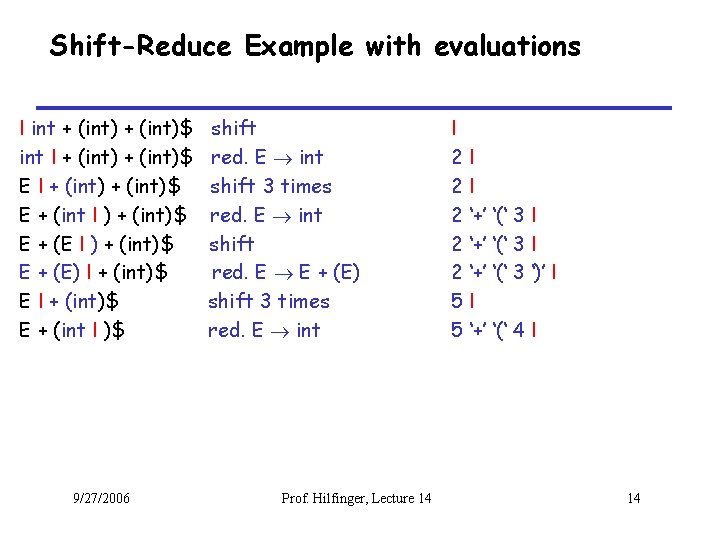

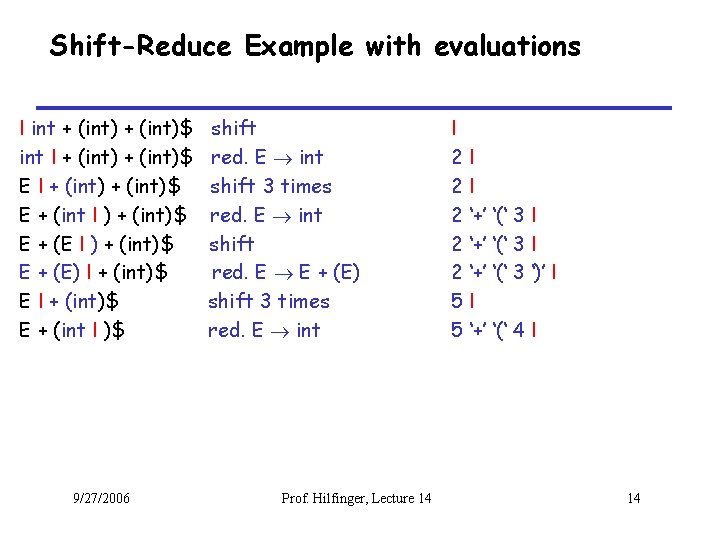

Shift-Reduce Example with evaluations I int + (int)$ int I + (int)$ E + (int I ) + (int)$ E + (E) I + (int)$ E + (int I )$ 9/27/2006 shift red. E int shift 3 times red. E int shift red. E E + (E) shift 3 times red. E int Prof. Hilfinger, Lecture 14 I 2 I 2 I 2 ‘+’ ‘(‘ 3 ‘)’ I 5 I 5 ‘+’ ‘(‘ 4 I 14

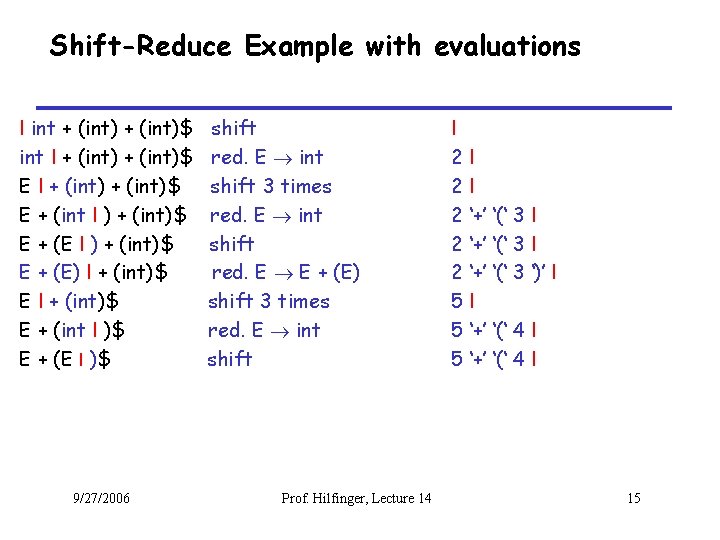

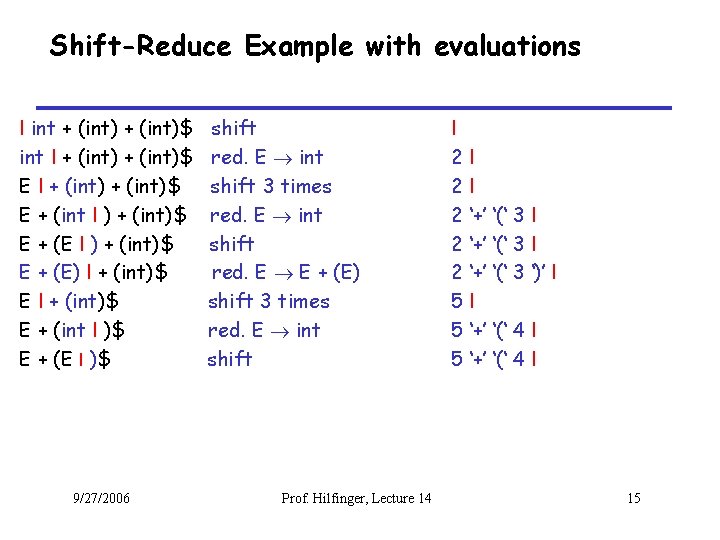

Shift-Reduce Example with evaluations I int + (int)$ int I + (int)$ E + (int I ) + (int)$ E + (E) I + (int)$ E + (int I )$ E + (E I )$ 9/27/2006 shift red. E int shift 3 times red. E int shift red. E E + (E) shift 3 times red. E int shift Prof. Hilfinger, Lecture 14 I 2 I 2 I 2 ‘+’ ‘(‘ 3 ‘)’ I 5 I 5 ‘+’ ‘(‘ 4 I 15

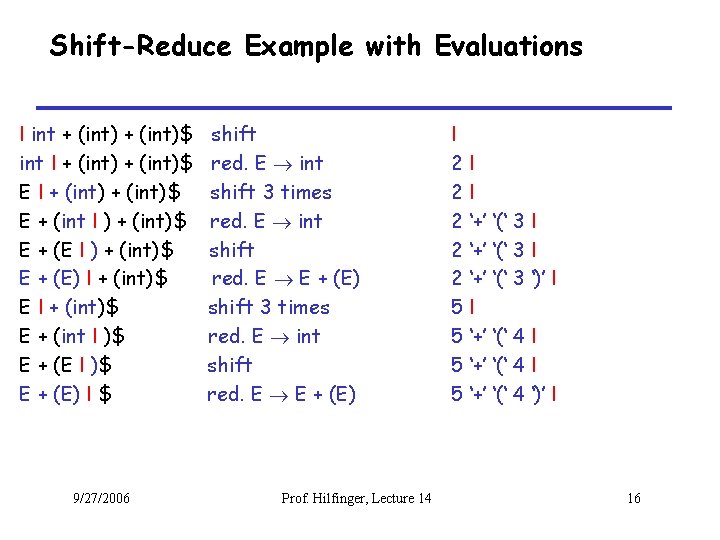

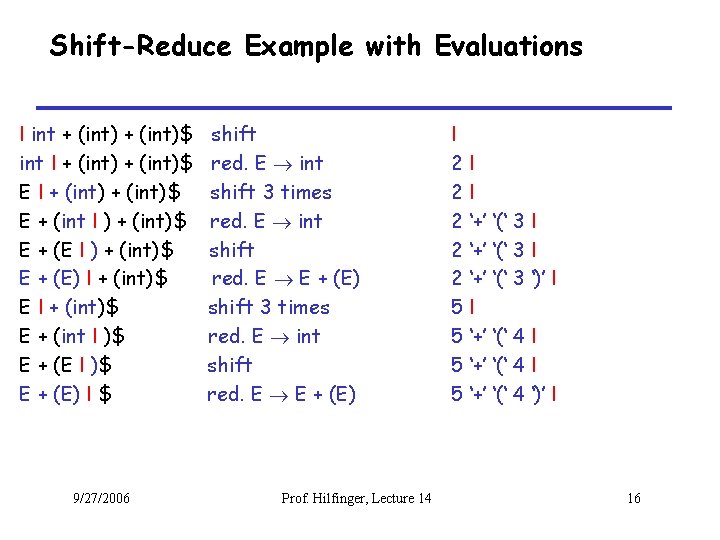

Shift-Reduce Example with Evaluations I int + (int)$ int I + (int)$ E + (int I ) + (int)$ E + (E) I + (int)$ E + (int I )$ E + (E) I $ 9/27/2006 shift red. E int shift 3 times red. E int shift red. E E + (E) Prof. Hilfinger, Lecture 14 I 2 I 2 I 2 ‘+’ ‘(‘ 3 ‘)’ I 5 I 5 ‘+’ ‘(‘ 4 ‘)’ I 16

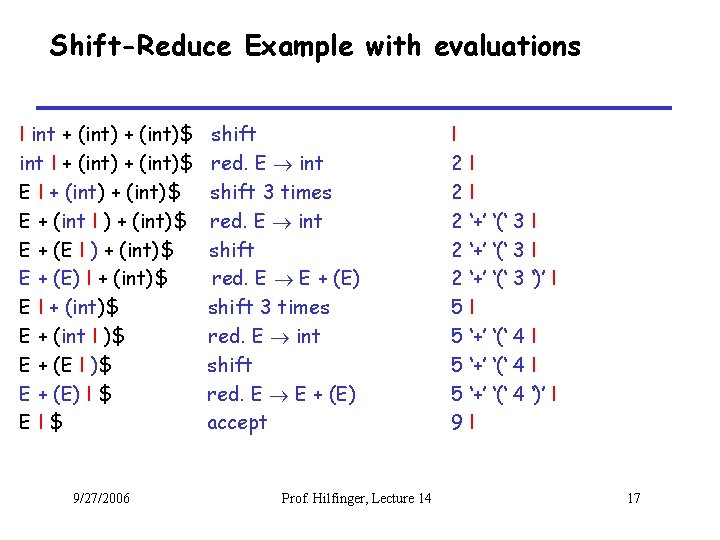

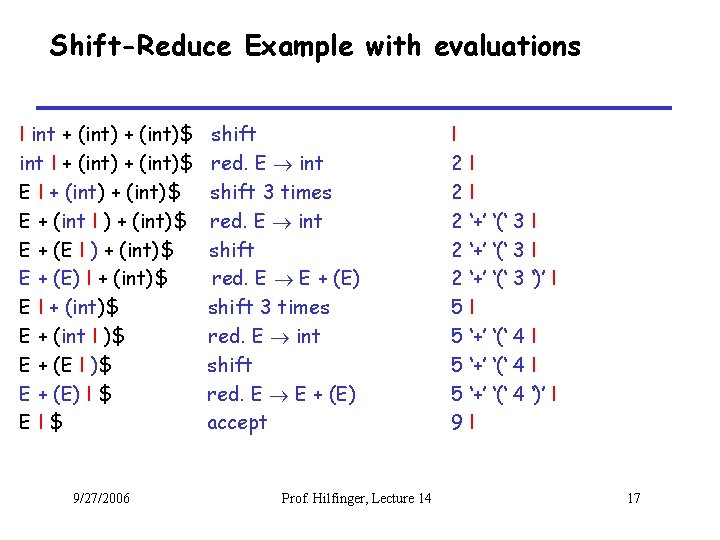

Shift-Reduce Example with evaluations I int + (int)$ int I + (int)$ E + (int I ) + (int)$ E + (E) I + (int)$ E + (int I )$ E + (E) I $ EI$ 9/27/2006 shift red. E int shift 3 times red. E int shift red. E E + (E) accept Prof. Hilfinger, Lecture 14 I 2 I 2 I 2 ‘+’ ‘(‘ 3 ‘)’ I 5 I 5 ‘+’ ‘(‘ 4 ‘)’ I 9 I 17

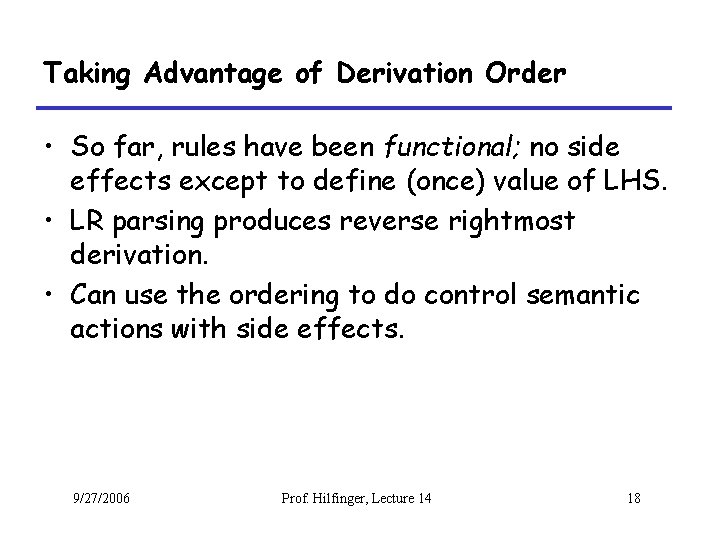

Taking Advantage of Derivation Order • So far, rules have been functional; no side effects except to define (once) value of LHS. • LR parsing produces reverse rightmost derivation. • Can use the ordering to do control semantic actions with side effects. 9/27/2006 Prof. Hilfinger, Lecture 14 18

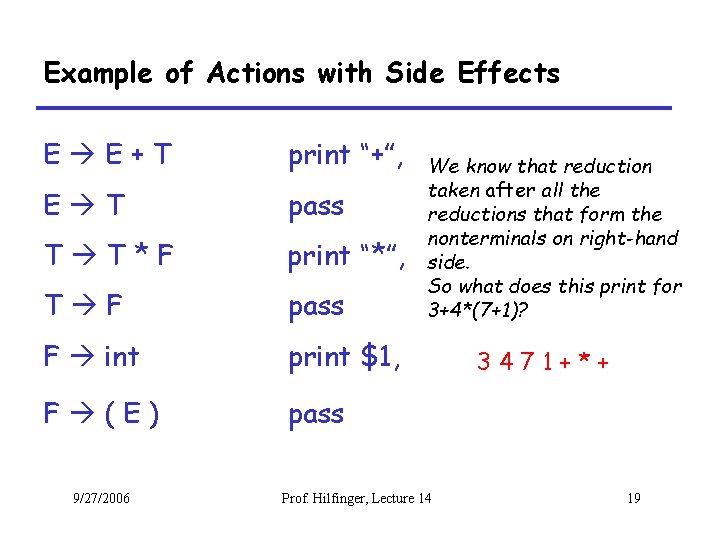

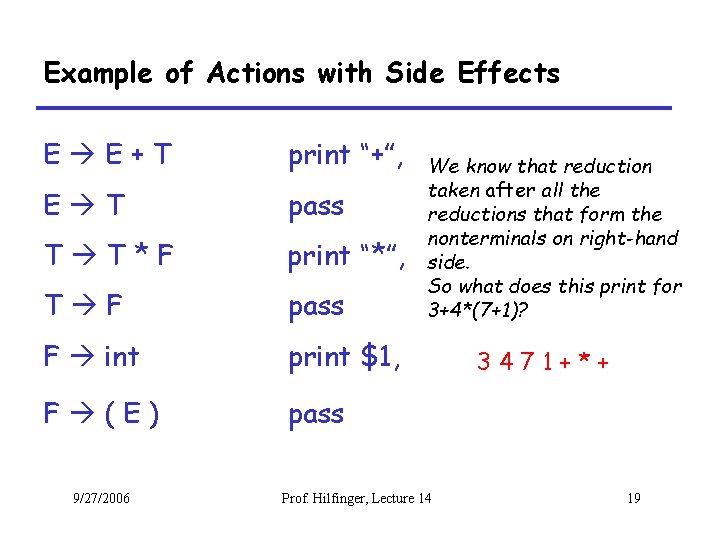

Example of Actions with Side Effects E E+T print “+”, E T pass T T*F print “*”, T F pass F int print $1, F (E) pass 9/27/2006 We know that reduction taken after all the reductions that form the nonterminals on right-hand side. So what does this print for 3+4*(7+1)? Prof. Hilfinger, Lecture 14 3471+*+ 19

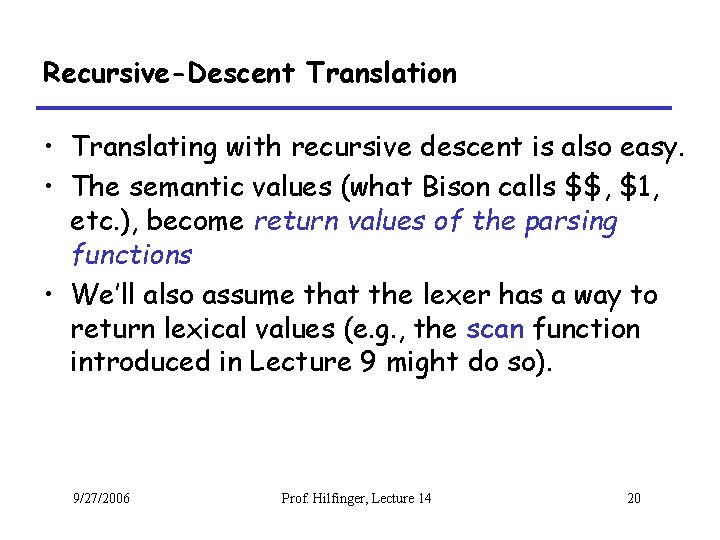

Recursive-Descent Translation • Translating with recursive descent is also easy. • The semantic values (what Bison calls $$, $1, etc. ), become return values of the parsing functions • We’ll also assume that the lexer has a way to return lexical values (e. g. , the scan function introduced in Lecture 9 might do so). 9/27/2006 Prof. Hilfinger, Lecture 14 20

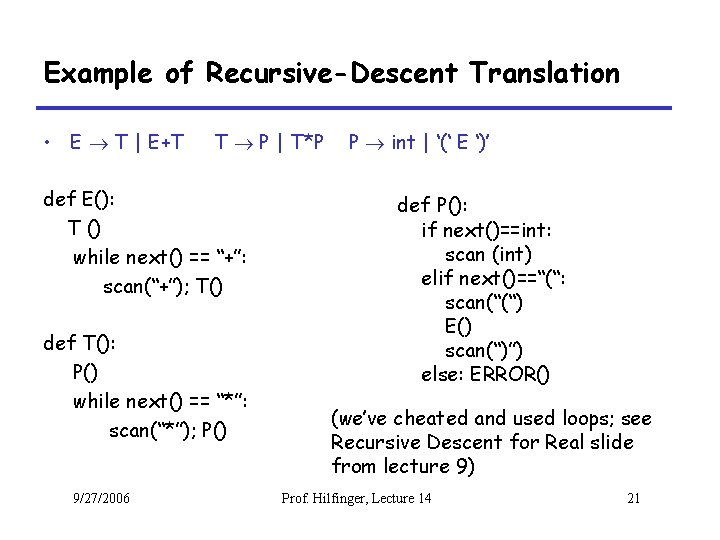

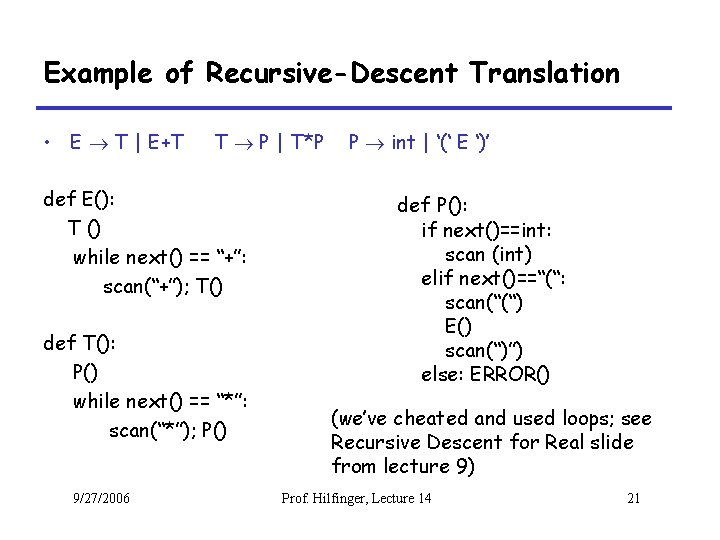

Example of Recursive-Descent Translation • E T | E+T T P | T*P def E(): T () while next() == “+”: scan(“+”); T() def T(): P() while next() == “*”: scan(“*”); P() 9/27/2006 P int | ‘(‘ E ‘)’ def P(): if next()==int: scan (int) elif next()==“(“: scan(“(“) E() scan(“)”) else: ERROR() (we’ve cheated and used loops; see Recursive Descent for Real slide from lecture 9) Prof. Hilfinger, Lecture 14 21

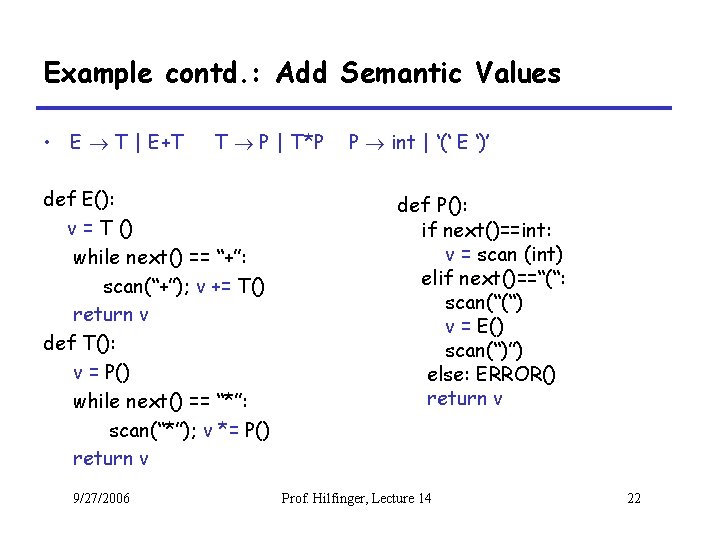

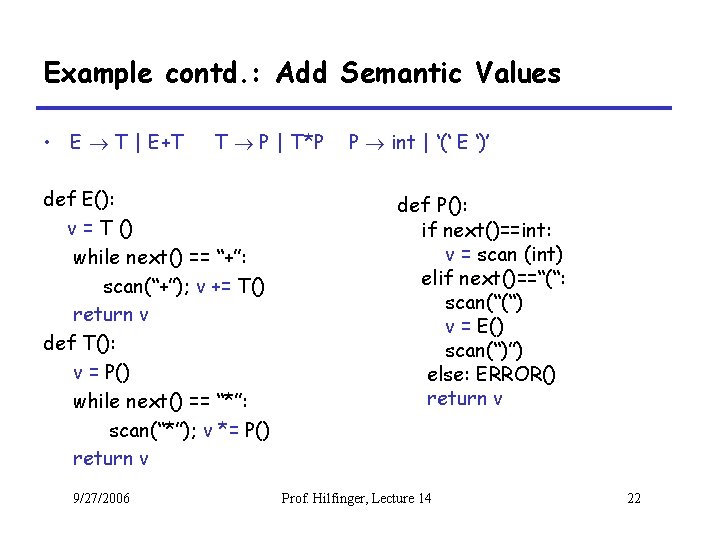

Example contd. : Add Semantic Values • E T | E+T T P | T*P def E(): v = T () while next() == “+”: scan(“+”); v += T() return v def T(): v = P() while next() == “*”: scan(“*”); v *= P() return v 9/27/2006 P int | ‘(‘ E ‘)’ def P(): if next()==int: v = scan (int) elif next()==“(“: scan(“(“) v = E() scan(“)”) else: ERROR() return v Prof. Hilfinger, Lecture 14 22

Table-Driven LL(1) • We can automate all this, and add to the LL(1) parser method from Lecture 9. • However, this gets a little involved, and I’m not sure it’s worth it. • (That is, let’s leave it to the LL(1) parser generators for now!) 9/27/2006 Prof. Hilfinger, Lecture 14 23

Dealing with Syntax Errors • One purpose of the parser is to filter out errors that show up in parsing • Later stages should not have to deal with possibility of malformed constructs • Parser must identify error so programmer knows what to correct • Parser should recover so that processing can continue (and other errors found) • Parser might even correct error (e. g. , PL/C compiler could “correct” some Fortran programs into equivalent PL/1 programs!) 9/27/2006 Prof. Hilfinger, Lecture 14 24

Identifying Errors • All of the valid parsers we’ve seen identify syntax errors “as soon as possible. ” • Valid prefix property: all the input that is shifted or scanned is the beginning of some valid program • … But the rest of the input might not be • So in principle, deleting the lookahead (and subsequent symbols) and inserting others will give a valid program. 9/27/2006 Prof. Hilfinger, Lecture 14 25

Automating Recovery • Unfortunately, best results require using semantic knowledge and hand tuning. – E. g. , a(i]. y = 5 might be turned to a[i]. y = 5 if a is statically known to be a list, or a(i). y = 5 if a function. • Some automatic methods can do an OK job that at least allows parser to catch more than one error. 9/27/2006 Prof. Hilfinger, Lecture 14 26

Bison’s Technique • The special terminal symbol error is never actually returned by the lexer. • Gets inserted by parser in place of erroneous tokens. • Parsing then proceeds normally. 9/27/2006 Prof. Hilfinger, Lecture 14 27

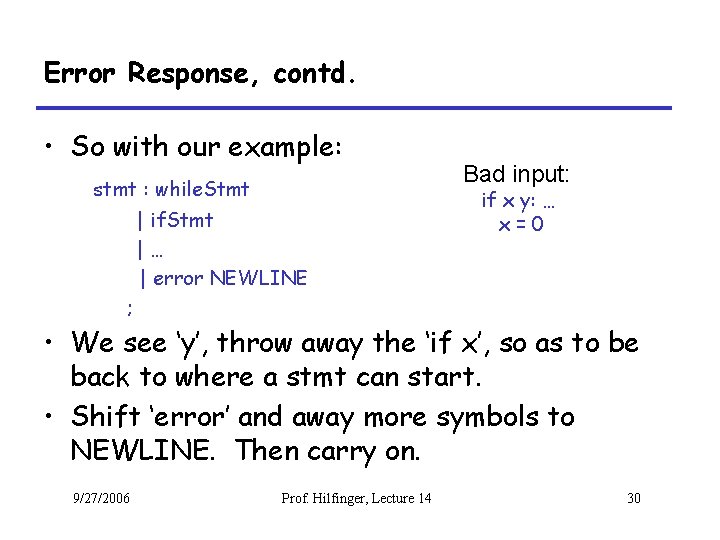

Example of Bison’s Error Rules • Suppose we want to throw away bad statements and carry on stmt : while. Stmt | if. Stmt |… | error NEWLINE ; 9/27/2006 Prof. Hilfinger, Lecture 14 28

Response to Error • Consider erroneous text like if x y: … • When parser gets to the y, will detect error. • Then pops items off parsing stack until it finds a state that allows a shift or reduction on ‘error’ terminal • Does reductions, then shifts ‘error’. • Finally, throws away input until it finds a symbol it can shift after ‘error’ 9/27/2006 Prof. Hilfinger, Lecture 14 29

Error Response, contd. • So with our example: stmt : while. Stmt | if. Stmt |… | error NEWLINE Bad input: if x y: … x=0 ; • We see ‘y’, throw away the ‘if x’, so as to be back to where a stmt can start. • Shift ‘error’ and away more symbols to NEWLINE. Then carry on. 9/27/2006 Prof. Hilfinger, Lecture 14 30

Of Course, It’s Not Perfect • “Throw away and punt” is sometimes called “panic-mode error recovery” • Results are often annoying. • For example, in our example, there’s an INDENT after the NEWLINE, which doesn’t fit the grammar and causes another error. • Bison compensates in this case by not reporting errors that are too close together • But in general, can get cascade of errors. • Doing it right takes a lot of work. 9/27/2006 Prof. Hilfinger, Lecture 14 31