Other Forms of Intermediate Code Local Optimizations Lecture

![Array Descriptors • Calculation of element address for e 1[e 2, e 3] has Array Descriptors • Calculation of element address for e 1[e 2, e 3] has](https://slidetodoc.com/presentation_image/3b6b596268ec104cba5a0a848a234a3d/image-14.jpg)

- Slides: 52

Other Forms of Intermediate Code. Local Optimizations Lecture 34 (Adapted from notes by R. Bodik and G. Necula) 4/18/08 Prof. Hilfinger CS 164 Lecture 34 1

Administrative • HW #5 is now on-line. Due next Friday. • If your test grade is not glookupable, please tell us. • Please submit test regrading pleas to the TAs. 4/18/08 Prof. Hilfinger CS 164 Lecture 34 2

Code Generation Summary • We have discussed – Runtime organization – Simple stack machine code generation • So far, compiler goes directly from AST to assembly language, and does not perform optimizations, • Whereas most real compilers use an intermediate language (IL), which they later convert to assembly or machine language. 4/18/08 Prof. Hilfinger CS 164 Lecture 34 3

Why Intermediate Languages ? • Slightly higher-level target simplifies translation of AST Code • IL can be sufficiently machine-independent to allow multiple backends (translators from IL to machine code) for different machines, which cuts down on labor of porting a compiler. 4/18/08 Prof. Hilfinger CS 164 Lecture 34 4

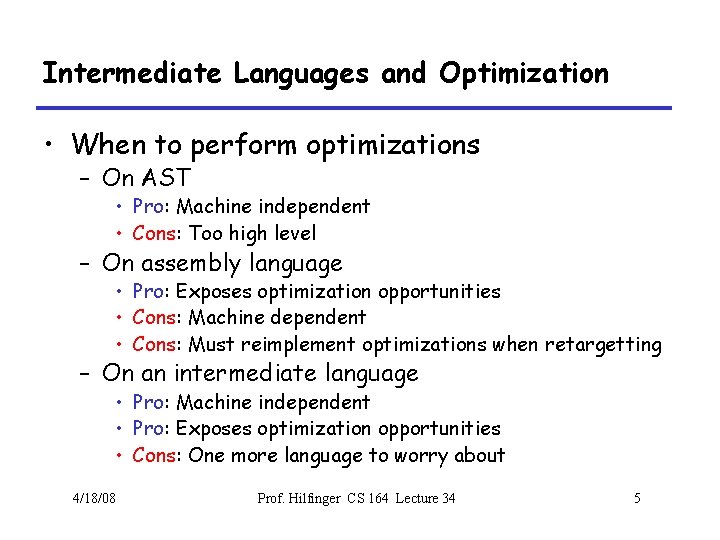

Intermediate Languages and Optimization • When to perform optimizations – On AST • Pro: Machine independent • Cons: Too high level – On assembly language • Pro: Exposes optimization opportunities • Cons: Machine dependent • Cons: Must reimplement optimizations when retargetting – On an intermediate language • Pro: Machine independent • Pro: Exposes optimization opportunities • Cons: One more language to worry about 4/18/08 Prof. Hilfinger CS 164 Lecture 34 5

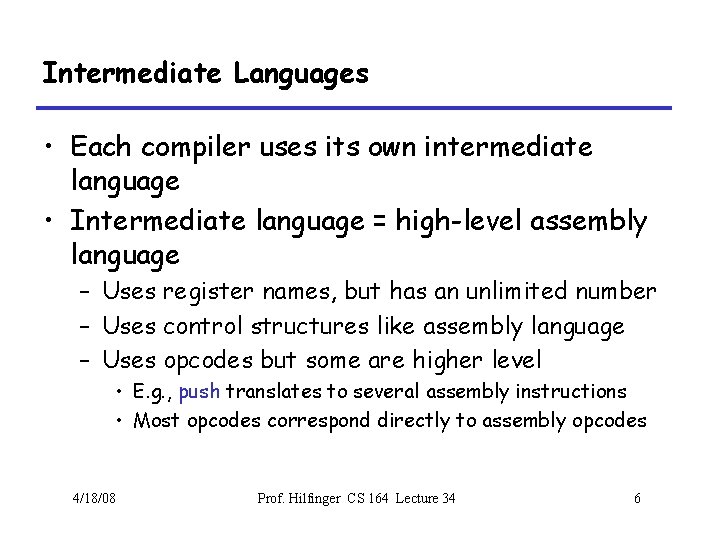

Intermediate Languages • Each compiler uses its own intermediate language • Intermediate language = high-level assembly language – Uses register names, but has an unlimited number – Uses control structures like assembly language – Uses opcodes but some are higher level • E. g. , push translates to several assembly instructions • Most opcodes correspond directly to assembly opcodes 4/18/08 Prof. Hilfinger CS 164 Lecture 34 6

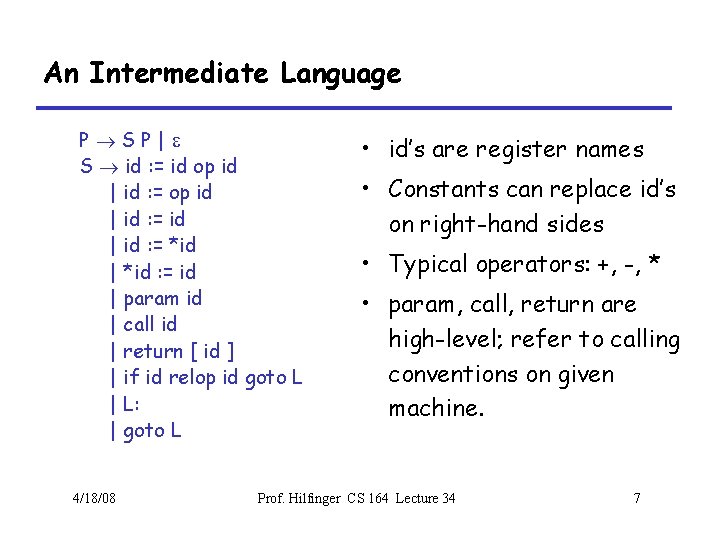

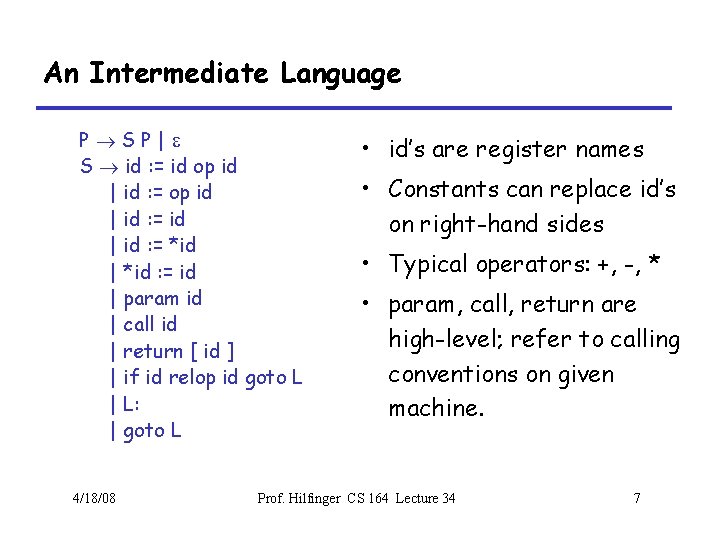

An Intermediate Language P®SP|e S ® id : = id op id | id : = *id | *id : = id | param id | call id | return [ id ] | if id relop id goto L | L: | goto L 4/18/08 • id’s are register names • Constants can replace id’s on right-hand sides • Typical operators: +, -, * • param, call, return are high-level; refer to calling conventions on given machine. Prof. Hilfinger CS 164 Lecture 34 7

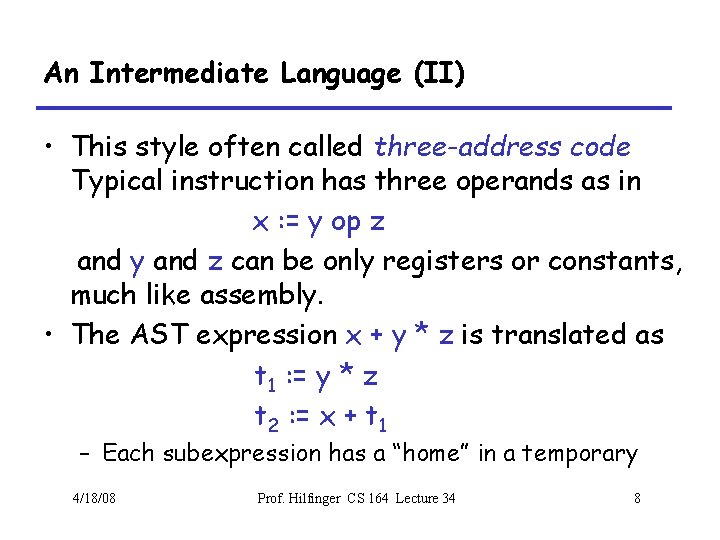

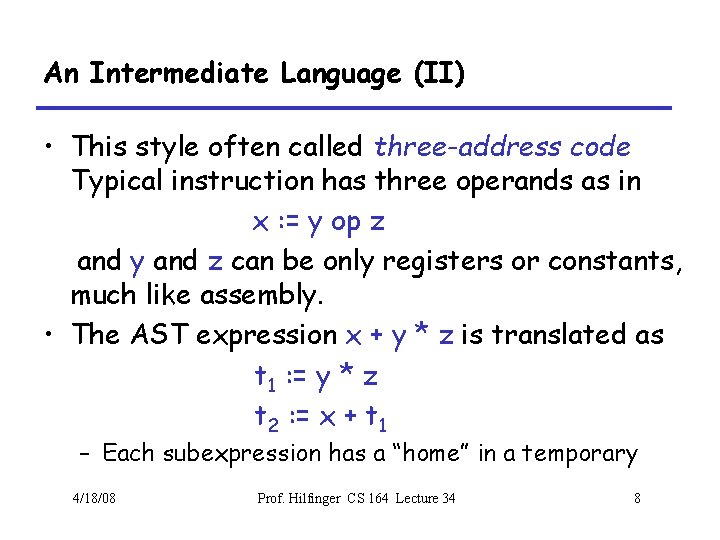

An Intermediate Language (II) • This style often called three-address code Typical instruction has three operands as in x : = y op z and y and z can be only registers or constants, much like assembly. • The AST expression x + y * z is translated as t 1 : = y * z t 2 : = x + t 1 – Each subexpression has a “home” in a temporary 4/18/08 Prof. Hilfinger CS 164 Lecture 34 8

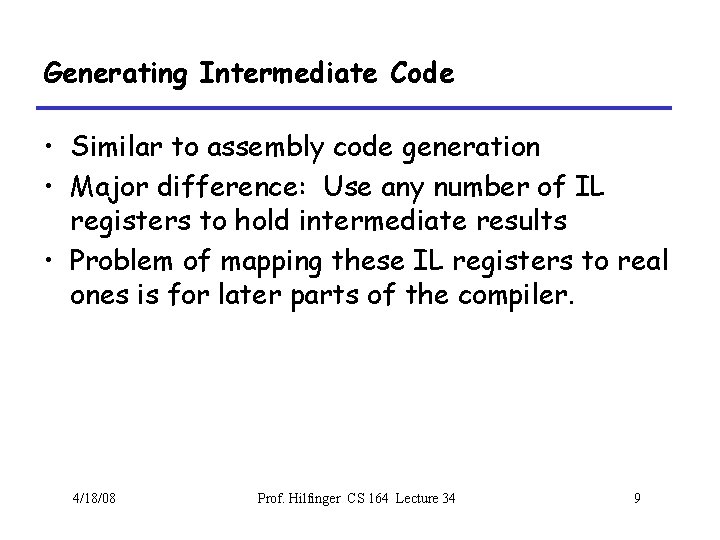

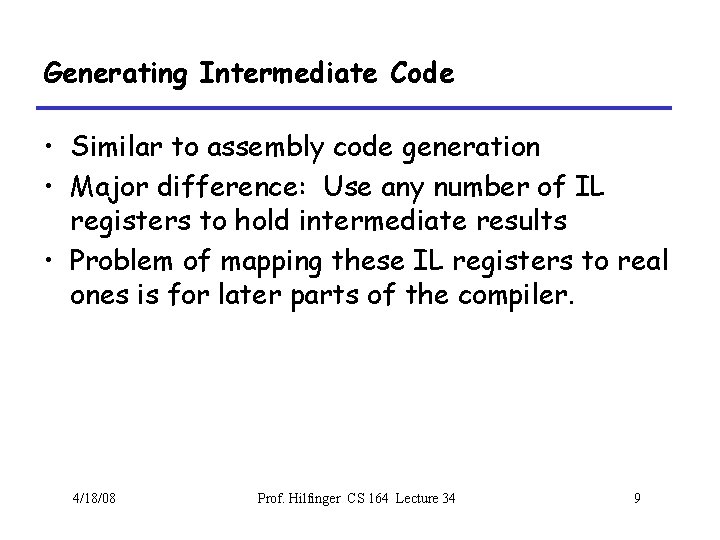

Generating Intermediate Code • Similar to assembly code generation • Major difference: Use any number of IL registers to hold intermediate results • Problem of mapping these IL registers to real ones is for later parts of the compiler. 4/18/08 Prof. Hilfinger CS 164 Lecture 34 9

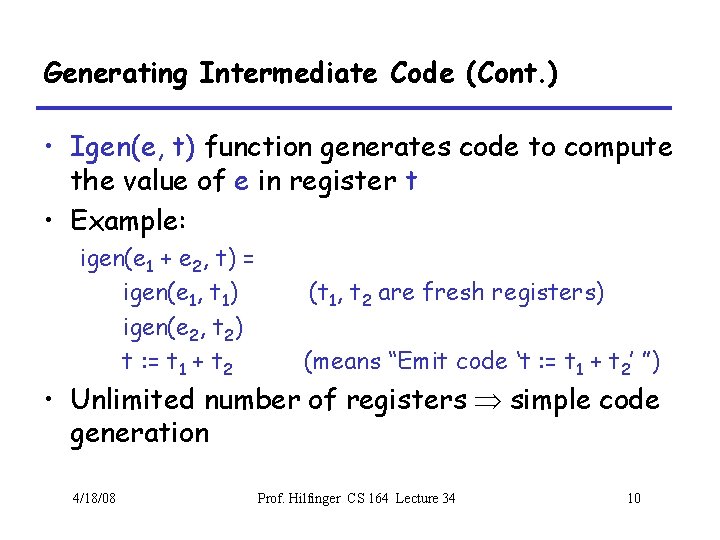

Generating Intermediate Code (Cont. ) • Igen(e, t) function generates code to compute the value of e in register t • Example: igen(e 1 + e 2, t) = igen(e 1, t 1) igen(e 2, t 2) t : = t 1 + t 2 (t 1, t 2 are fresh registers) (means “Emit code ‘t : = t 1 + t 2’ ”) • Unlimited number of registers Þ simple code generation 4/18/08 Prof. Hilfinger CS 164 Lecture 34 10

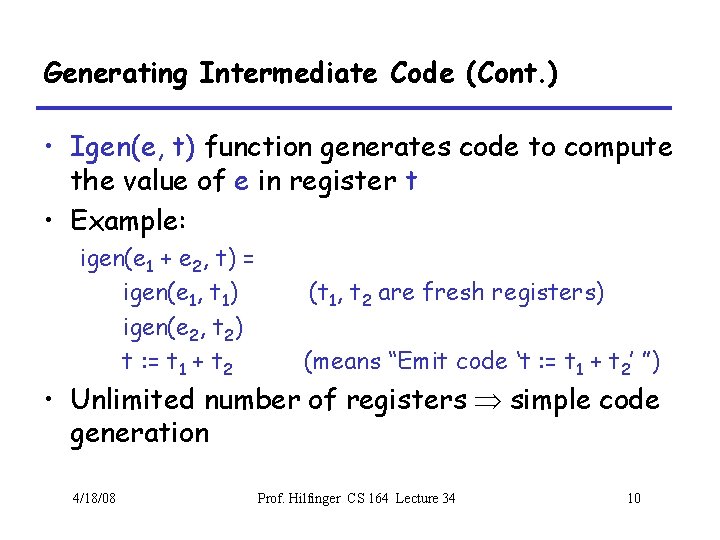

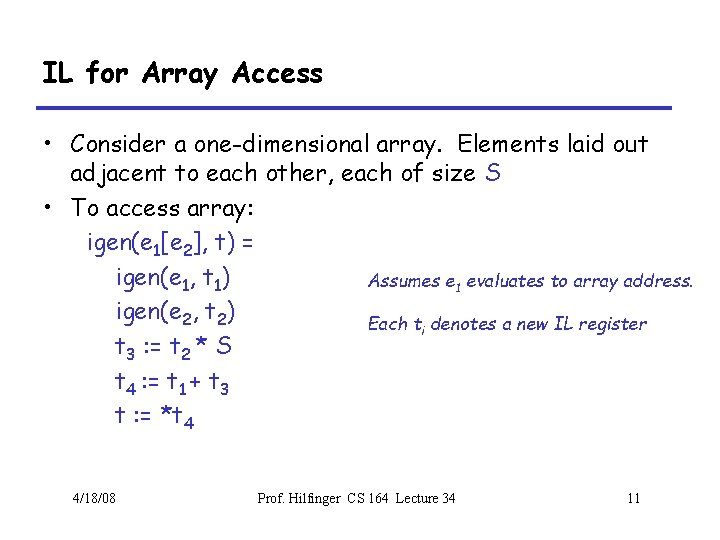

IL for Array Access • Consider a one-dimensional array. Elements laid out adjacent to each other, each of size S • To access array: igen(e 1[e 2], t) = igen(e 1, t 1) Assumes e 1 evaluates to array address. igen(e 2, t 2) Each ti denotes a new IL register t 3 : = t 2 * S t 4 : = t 1 + t 3 t : = *t 4 4/18/08 Prof. Hilfinger CS 164 Lecture 34 11

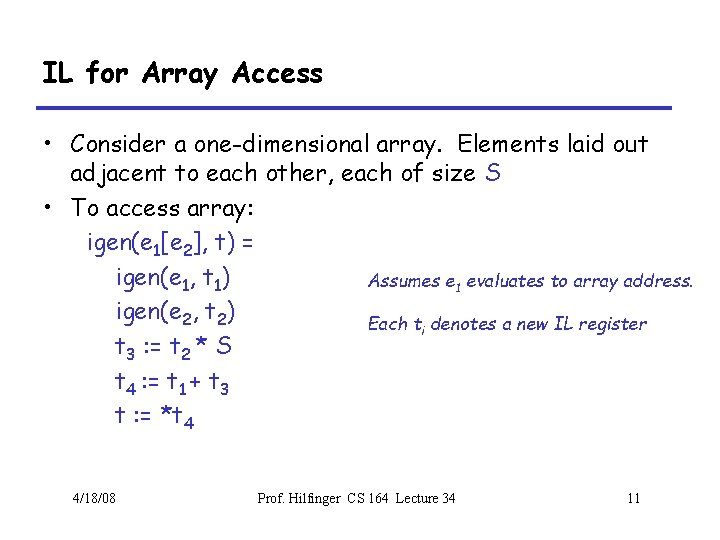

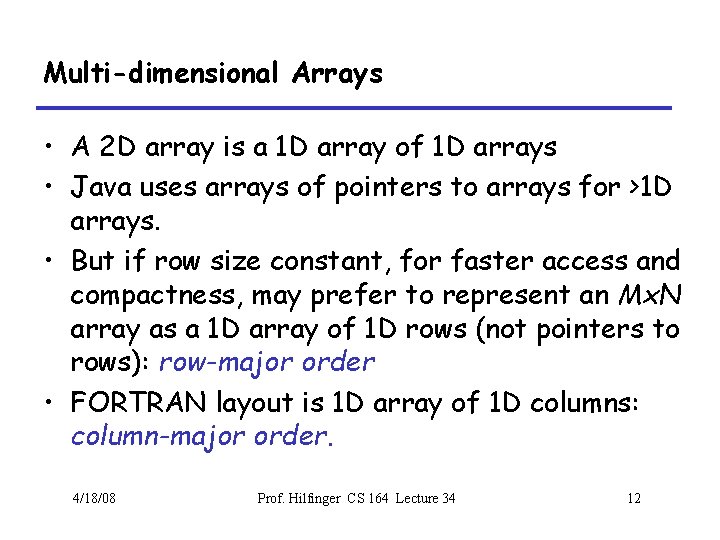

Multi-dimensional Arrays • A 2 D array is a 1 D array of 1 D arrays • Java uses arrays of pointers to arrays for >1 D arrays. • But if row size constant, for faster access and compactness, may prefer to represent an Mx. N array as a 1 D array of 1 D rows (not pointers to rows): row-major order • FORTRAN layout is 1 D array of 1 D columns: column-major order. 4/18/08 Prof. Hilfinger CS 164 Lecture 34 12

IL for 2 D Arrays (Row-Major Order) • Again, let S be size of one element, so that a row of length N has size Nx. S. igen(e 1[e 2, e 3], t) = igen(e 1, t 1); igen(e 2, t 2); igen(e 3, t 3) igen(N, t 4) (N need not be constant) t 5 : = t 4 * t 2; t 6 : = t 5 + t 3; t 7 : = t 6*S; t 8 : = t 7 + t 1 t : = *t 8 4/18/08 Prof. Hilfinger CS 164 Lecture 34 13

![Array Descriptors Calculation of element address for e 1e 2 e 3 has Array Descriptors • Calculation of element address for e 1[e 2, e 3] has](https://slidetodoc.com/presentation_image/3b6b596268ec104cba5a0a848a234a3d/image-14.jpg)

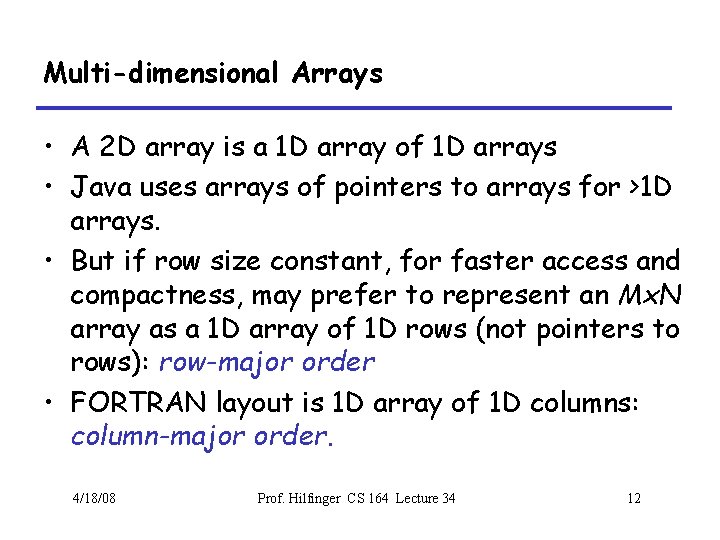

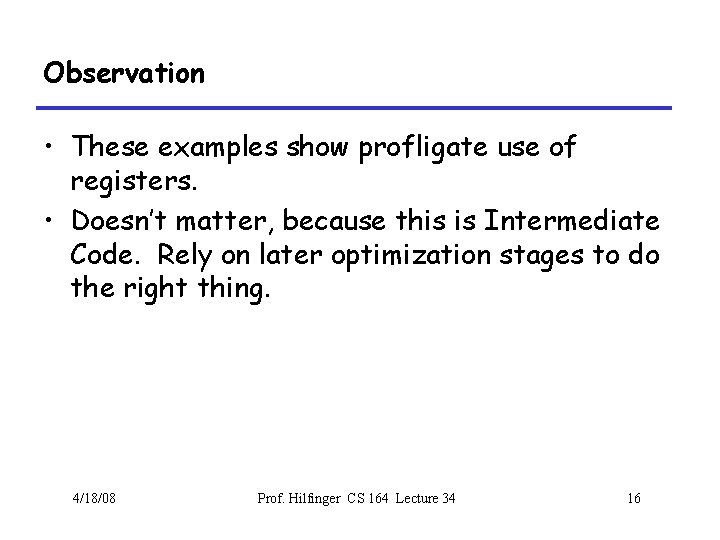

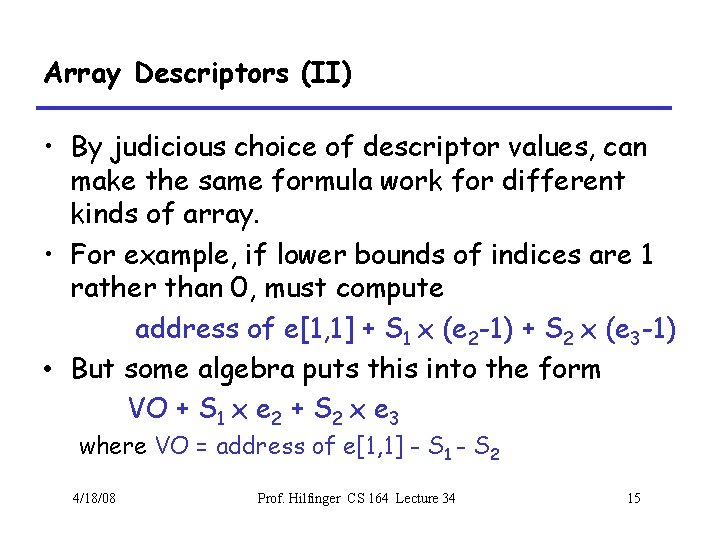

Array Descriptors • Calculation of element address for e 1[e 2, e 3] has form VO + S 1 x e 2 + S 2 x e 3, where – VO (address of e 1[0, 0]) is the virtual origin – S 1 and S 2 are strides – All three of these are constant throughout lifetime of array • Common to package these up into an array descriptor, which can be passed in lieu of the array itself. 4/18/08 Prof. Hilfinger CS 164 Lecture 34 14

Array Descriptors (II) • By judicious choice of descriptor values, can make the same formula work for different kinds of array. • For example, if lower bounds of indices are 1 rather than 0, must compute address of e[1, 1] + S 1 x (e 2 -1) + S 2 x (e 3 -1) • But some algebra puts this into the form VO + S 1 x e 2 + S 2 x e 3 where VO = address of e[1, 1] - S 1 - S 2 4/18/08 Prof. Hilfinger CS 164 Lecture 34 15

Observation • These examples show profligate use of registers. • Doesn’t matter, because this is Intermediate Code. Rely on later optimization stages to do the right thing. 4/18/08 Prof. Hilfinger CS 164 Lecture 34 16

Code Optimization: Basic Concepts 4/18/08 Prof. Hilfinger CS 164 Lecture 34 17

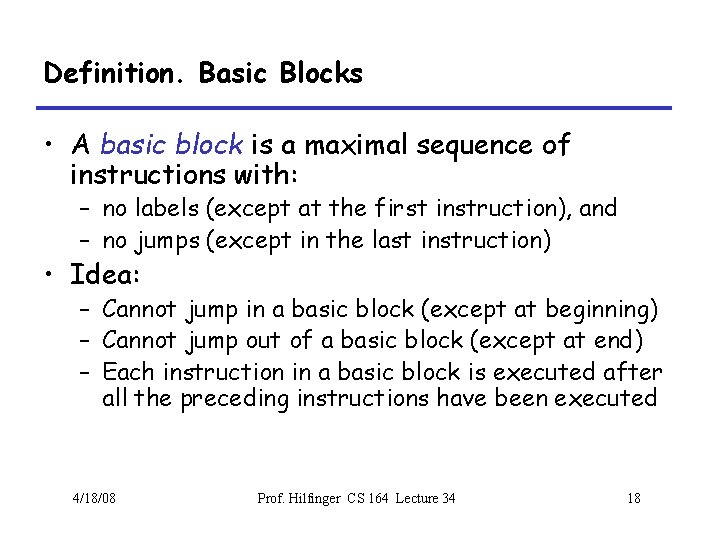

Definition. Basic Blocks • A basic block is a maximal sequence of instructions with: – no labels (except at the first instruction), and – no jumps (except in the last instruction) • Idea: – Cannot jump in a basic block (except at beginning) – Cannot jump out of a basic block (except at end) – Each instruction in a basic block is executed after all the preceding instructions have been executed 4/18/08 Prof. Hilfinger CS 164 Lecture 34 18

Basic Block Example • Consider the basic block 1. L: 2. t : = 2 * x 3. w : = t + x 4. if w > 0 goto L’ • No way for (3) to be executed without (2) having been executed right before – – We can change (3) to w : = 3 * x Can we eliminate (2) as well? 4/18/08 Prof. Hilfinger CS 164 Lecture 34 19

Definition. Control-Flow Graphs • A control-flow graph is a directed graph with – Basic blocks as nodes – An edge from block A to block B if the execution can flow from the last instruction in A to the first instruction in B – E. g. , the last instruction in A is jump LB – E. g. , the execution can fall-through from block A to block B • Frequently abbreviated as CFG 4/18/08 Prof. Hilfinger CS 164 Lecture 34 20

Control-Flow Graphs. Example. x : = 1 i : = 1 L: x : = x * x i : = i + 1 if i < 10 goto L 4/18/08 • The body of a method (or procedure) can be represented as a controlflow graph • There is one initial node • All “return” nodes are terminal Prof. Hilfinger CS 164 Lecture 34 21

Optimization Overview • Optimization seeks to improve a program’s utilization of some resource – – Execution time (most often) Code size Network messages sent Battery power used, etc. • Optimization should not alter what the program computes – The answer must still be the same 4/18/08 Prof. Hilfinger CS 164 Lecture 34 22

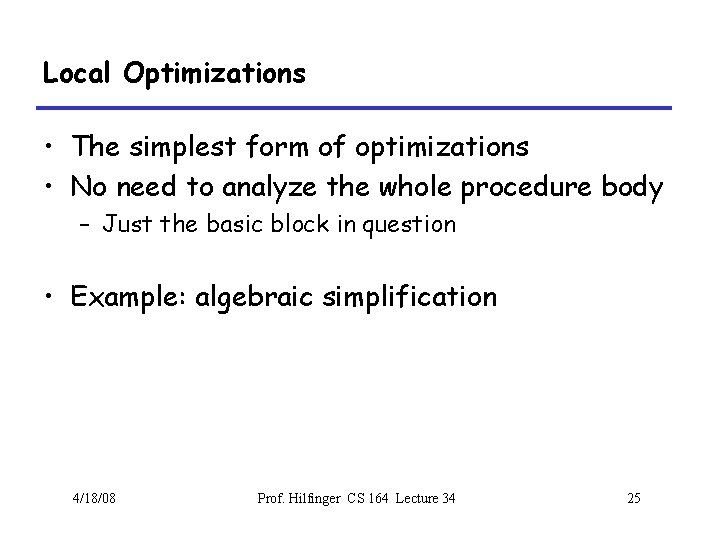

A Classification of Optimizations • For languages like C and Cool there are three granularities of optimizations 1. Local optimizations • Apply to a basic block in isolation 2. Global optimizations • Apply to a control-flow graph (method body) in isolation 3. Inter-procedural optimizations • • Apply across method boundaries Most compilers do (1), many do (2) and very few do (3) 4/18/08 Prof. Hilfinger CS 164 Lecture 34 23

Cost of Optimizations • In practice, a conscious decision is made not to implement the fanciest optimization known • Why? – Some optimizations are hard to implement – Some optimizations are costly in terms of compilation time – The fancy optimizations are both hard and costly • The goal: maximum improvement with minimum of cost 4/18/08 Prof. Hilfinger CS 164 Lecture 34 24

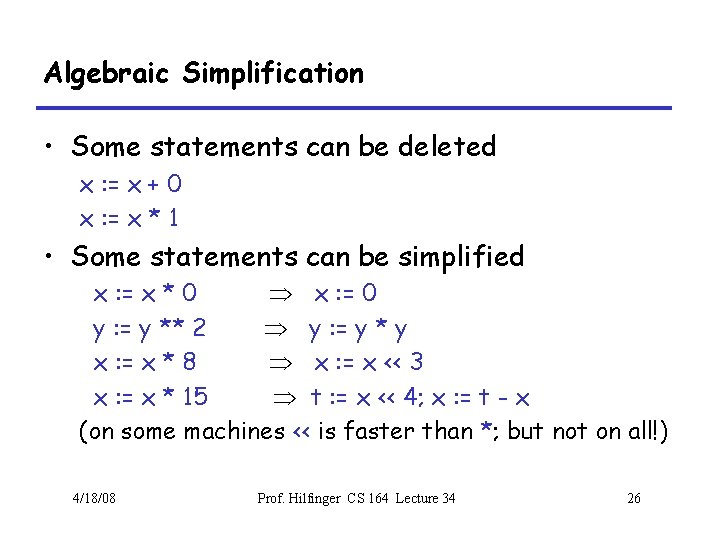

Local Optimizations • The simplest form of optimizations • No need to analyze the whole procedure body – Just the basic block in question • Example: algebraic simplification 4/18/08 Prof. Hilfinger CS 164 Lecture 34 25

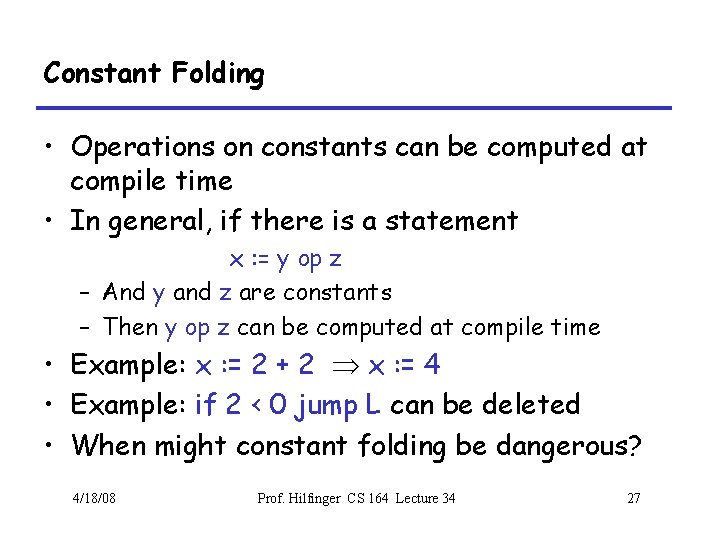

Algebraic Simplification • Some statements can be deleted x : = x + 0 x : = x * 1 • Some statements can be simplified x : = x * 0 Þ x : = 0 y : = y ** 2 Þ y : = y * y x : = x * 8 Þ x : = x << 3 x : = x * 15 Þ t : = x << 4; x : = t - x (on some machines << is faster than *; but not on all!) 4/18/08 Prof. Hilfinger CS 164 Lecture 34 26

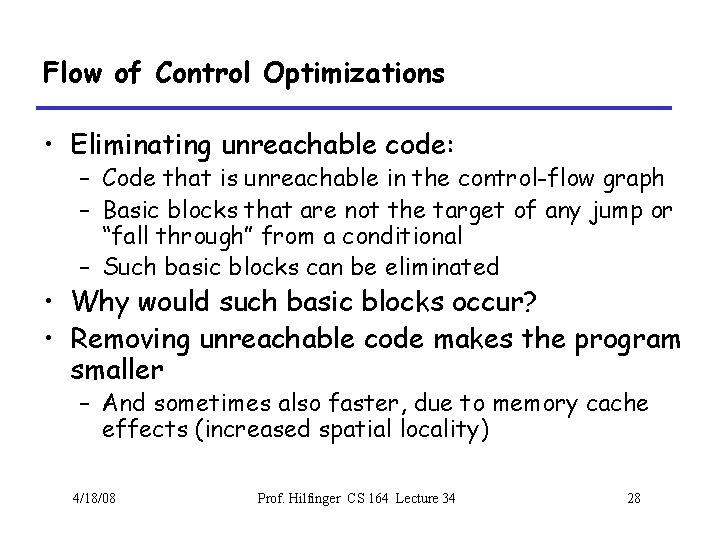

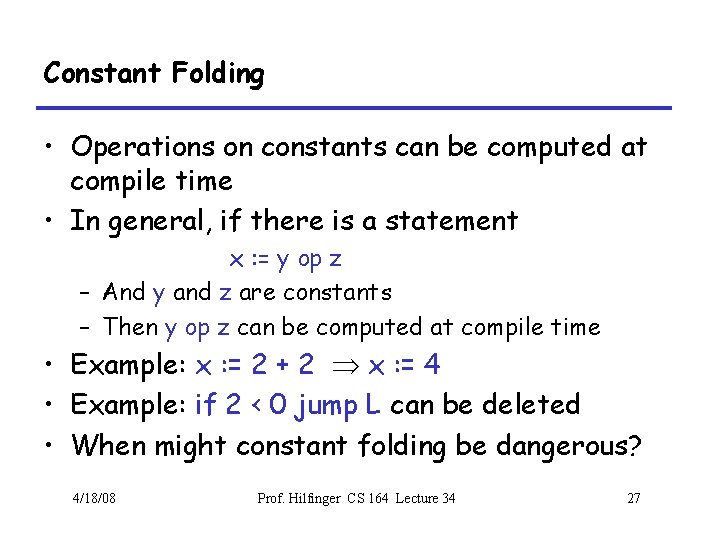

Constant Folding • Operations on constants can be computed at compile time • In general, if there is a statement x : = y op z – And y and z are constants – Then y op z can be computed at compile time • Example: x : = 2 + 2 Þ x : = 4 • Example: if 2 < 0 jump L can be deleted • When might constant folding be dangerous? 4/18/08 Prof. Hilfinger CS 164 Lecture 34 27

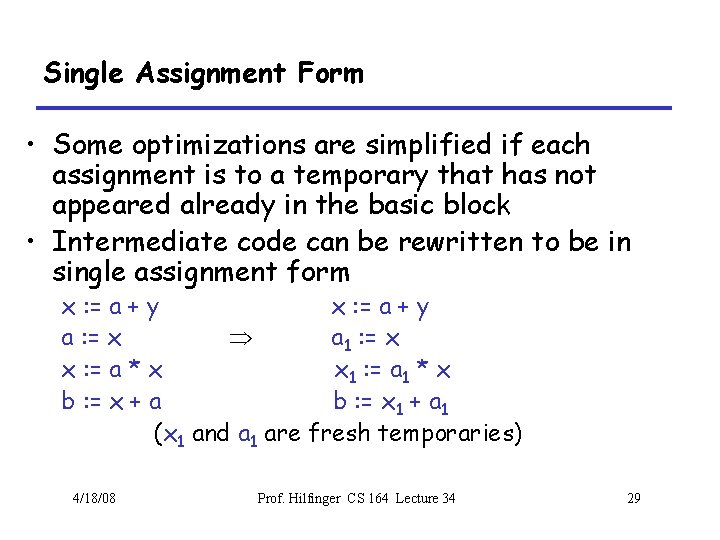

Flow of Control Optimizations • Eliminating unreachable code: – Code that is unreachable in the control-flow graph – Basic blocks that are not the target of any jump or “fall through” from a conditional – Such basic blocks can be eliminated • Why would such basic blocks occur? • Removing unreachable code makes the program smaller – And sometimes also faster, due to memory cache effects (increased spatial locality) 4/18/08 Prof. Hilfinger CS 164 Lecture 34 28

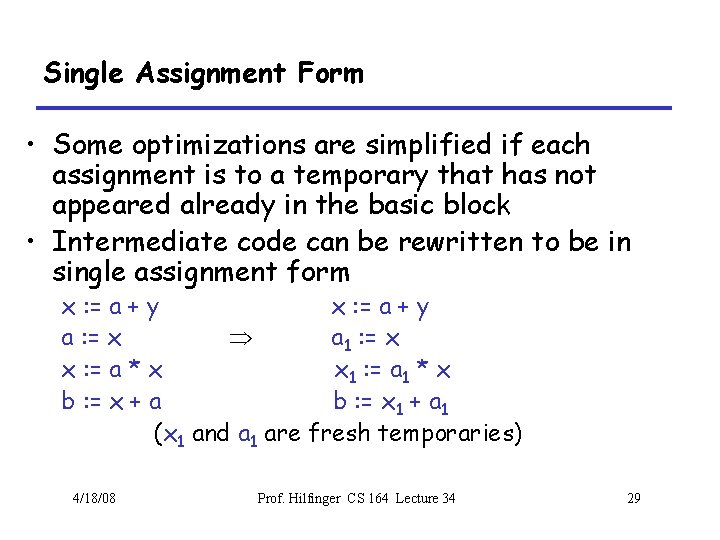

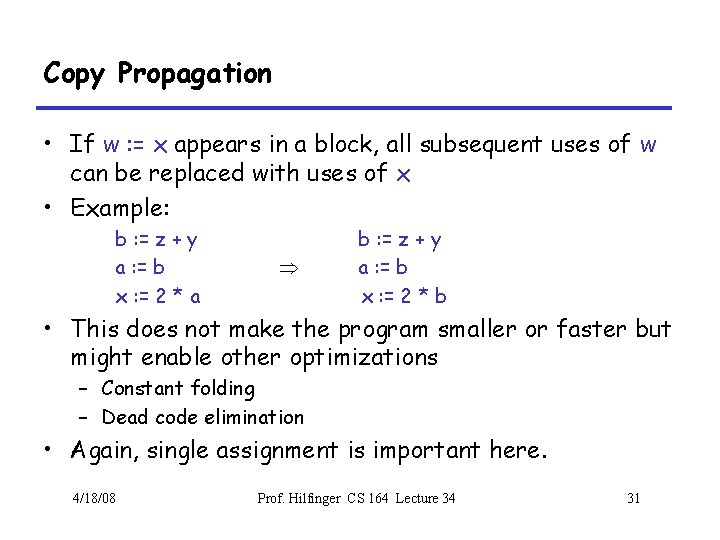

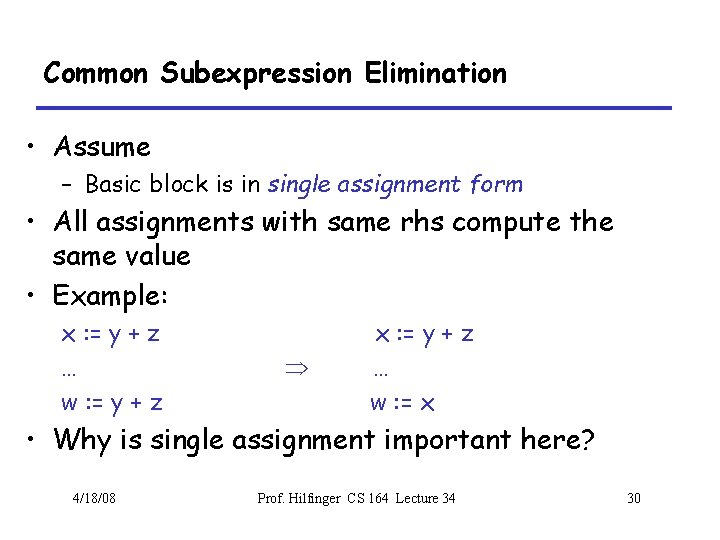

Single Assignment Form • Some optimizations are simplified if each assignment is to a temporary that has not appeared already in the basic block • Intermediate code can be rewritten to be in single assignment form x : = a + y a : = x Þ a 1 : = x x : = a * x x 1 : = a 1 * x b : = x + a b : = x 1 + a 1 (x 1 and a 1 are fresh temporaries) 4/18/08 Prof. Hilfinger CS 164 Lecture 34 29

Common Subexpression Elimination • Assume – Basic block is in single assignment form • All assignments with same rhs compute the same value • Example: x : = y + z … w : = y + z Þ x : = y + z … w : = x • Why is single assignment important here? 4/18/08 Prof. Hilfinger CS 164 Lecture 34 30

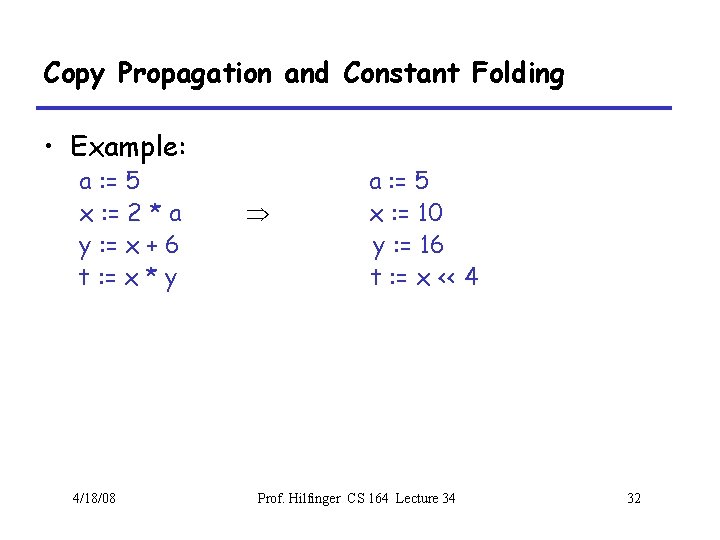

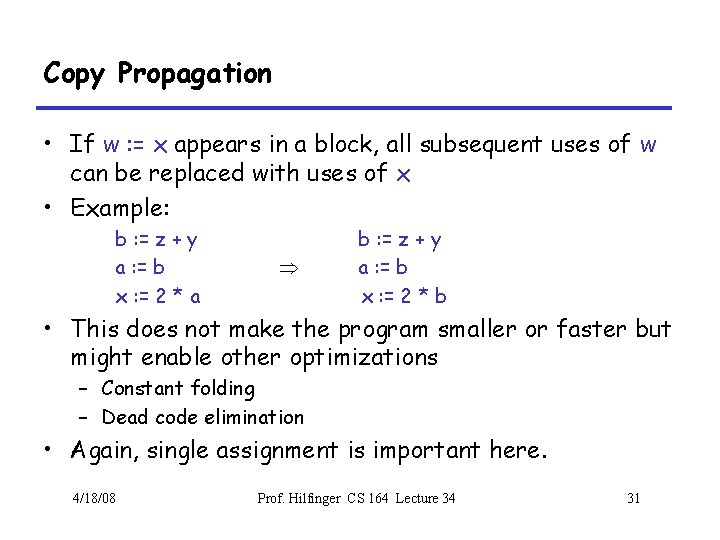

Copy Propagation • If w : = x appears in a block, all subsequent uses of w can be replaced with uses of x • Example: b : = z + y a : = b x : = 2 * a Þ b : = z + y a : = b x : = 2 * b • This does not make the program smaller or faster but might enable other optimizations – Constant folding – Dead code elimination • Again, single assignment is important here. 4/18/08 Prof. Hilfinger CS 164 Lecture 34 31

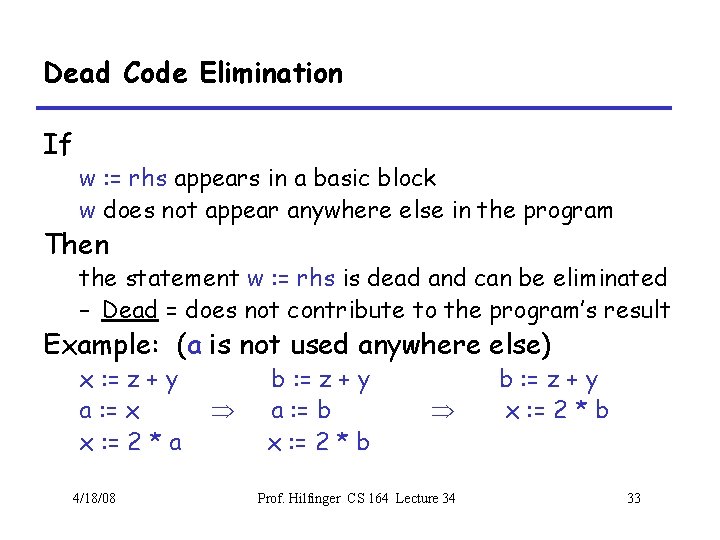

Copy Propagation and Constant Folding • Example: a : = 5 x : = 2 * a y : = x + 6 t : = x * y 4/18/08 Þ a : = 5 x : = 10 y : = 16 t : = x << 4 Prof. Hilfinger CS 164 Lecture 34 32

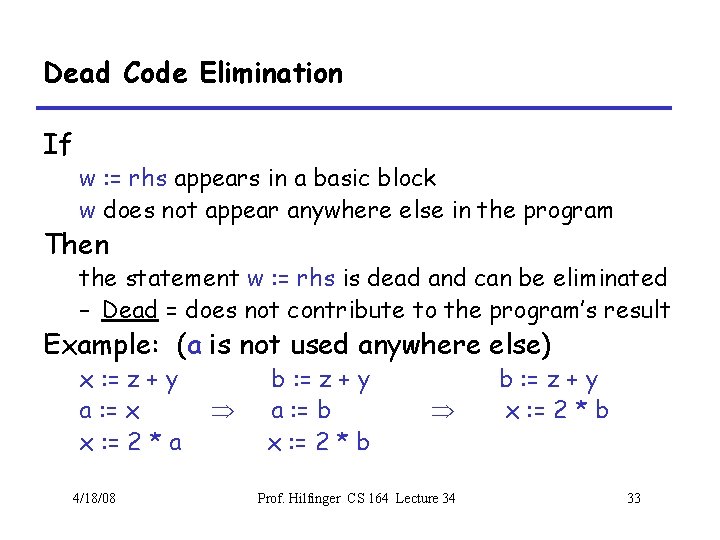

Dead Code Elimination If w : = rhs appears in a basic block w does not appear anywhere else in the program Then the statement w : = rhs is dead and can be eliminated – Dead = does not contribute to the program’s result Example: (a is not used anywhere else) x : = z + y a : = x x : = 2 * a 4/18/08 Þ b : = z + y a : = b x : = 2 * b Þ Prof. Hilfinger CS 164 Lecture 34 b : = z + y x : = 2 * b 33

Applying Local Optimizations • Each local optimization does very little by itself • Typically optimizations interact – Performing one optimizations enables other opt. • Typical optimizing compilers repeatedly perform optimizations until no improvement is possible – The optimizer can also be stopped at any time to limit the compilation time 4/18/08 Prof. Hilfinger CS 164 Lecture 34 34

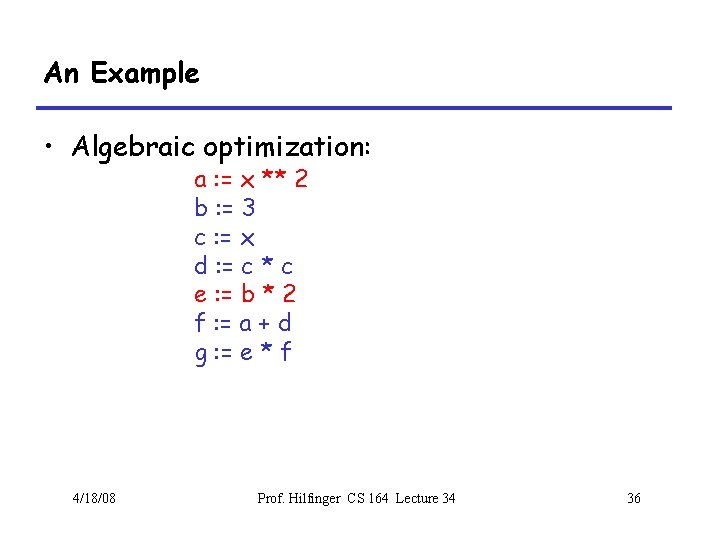

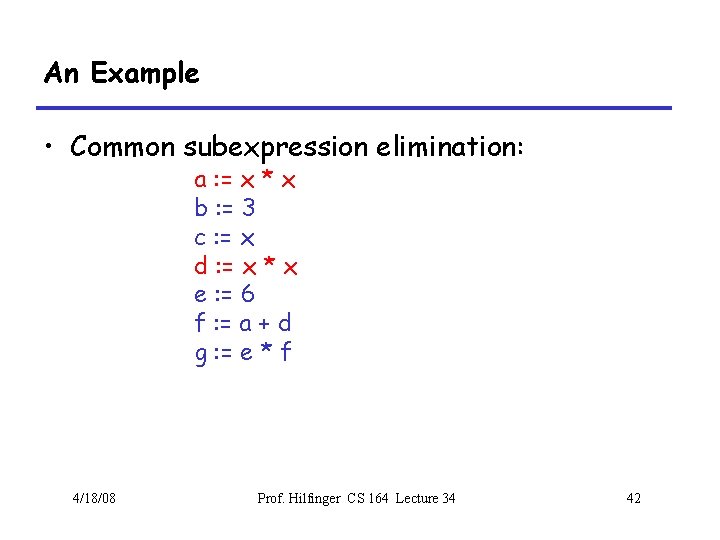

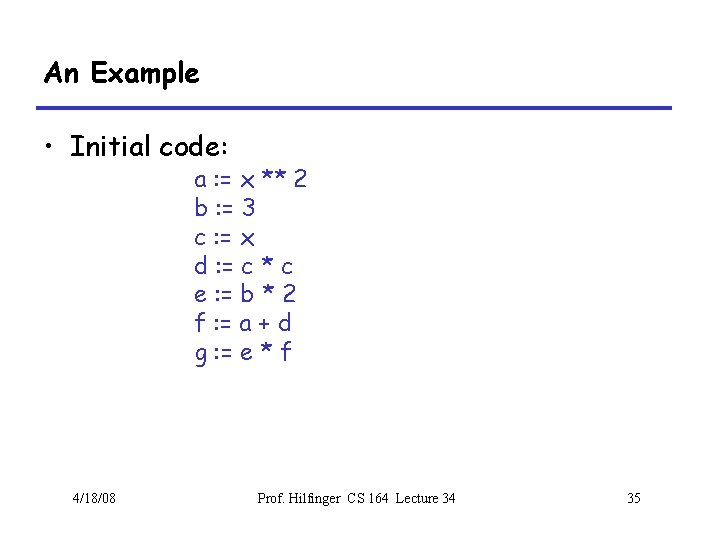

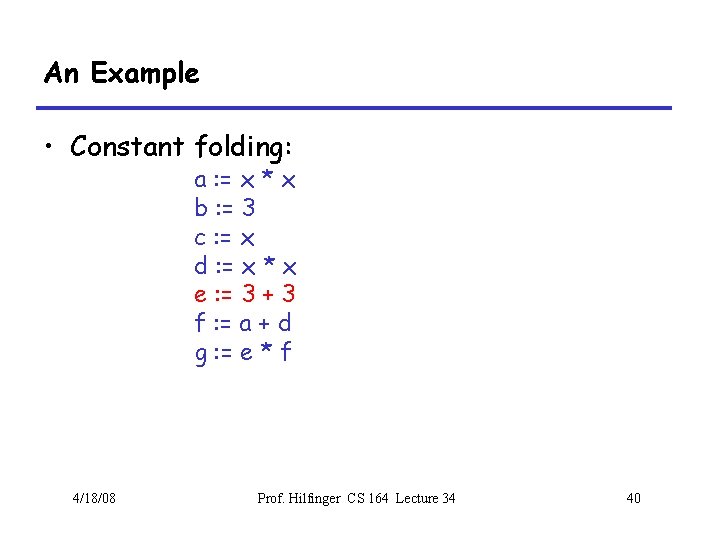

An Example • Initial code: a : = x ** 2 b : = 3 c : = x d : = c * c e : = b * 2 f : = a + d g : = e * f 4/18/08 Prof. Hilfinger CS 164 Lecture 34 35

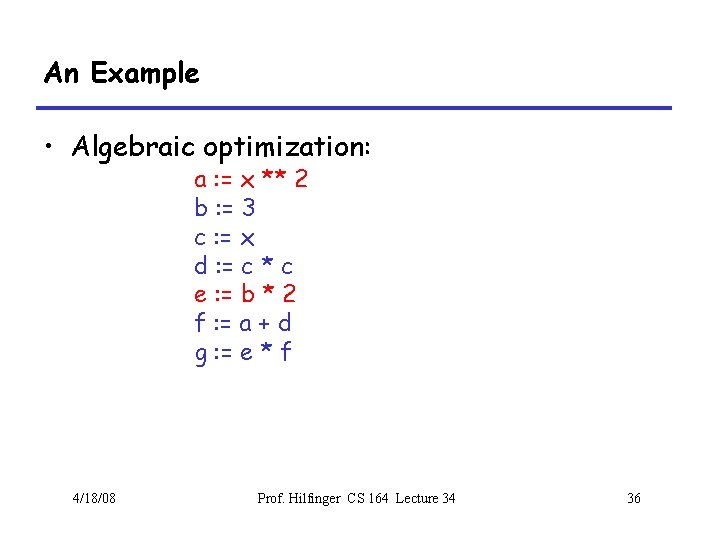

An Example • Algebraic optimization: a : = x ** 2 b : = 3 c : = x d : = c * c e : = b * 2 f : = a + d g : = e * f 4/18/08 Prof. Hilfinger CS 164 Lecture 34 36

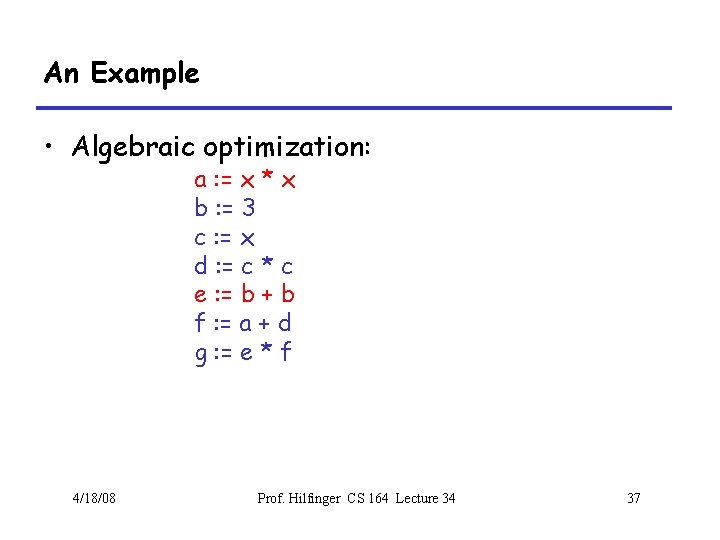

An Example • Algebraic optimization: a : = x * x b : = 3 c : = x d : = c * c e : = b + b f : = a + d g : = e * f 4/18/08 Prof. Hilfinger CS 164 Lecture 34 37

An Example • Copy propagation: a : = x * x b : = 3 c : = x d : = c * c e : = b + b f : = a + d g : = e * f 4/18/08 Prof. Hilfinger CS 164 Lecture 34 38

An Example • Copy propagation: a : = x * x b : = 3 c : = x d : = x * x e : = 3 + 3 f : = a + d g : = e * f 4/18/08 Prof. Hilfinger CS 164 Lecture 34 39

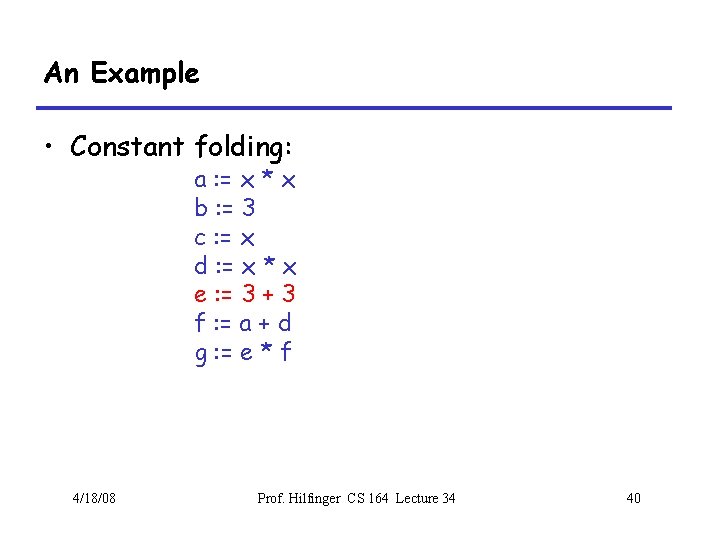

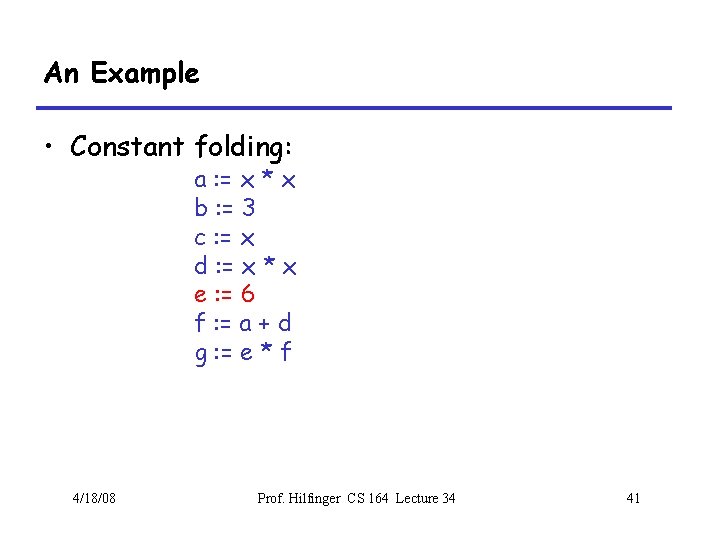

An Example • Constant folding: a : = x * x b : = 3 c : = x d : = x * x e : = 3 + 3 f : = a + d g : = e * f 4/18/08 Prof. Hilfinger CS 164 Lecture 34 40

An Example • Constant folding: a : = x * x b : = 3 c : = x d : = x * x e : = 6 f : = a + d g : = e * f 4/18/08 Prof. Hilfinger CS 164 Lecture 34 41

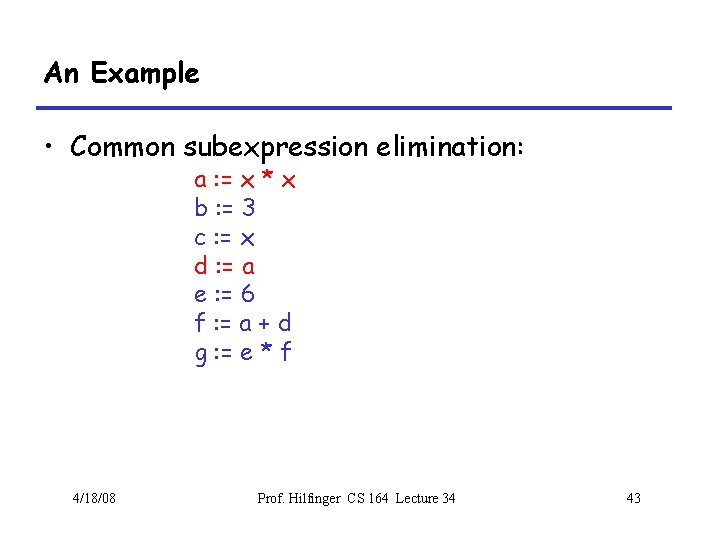

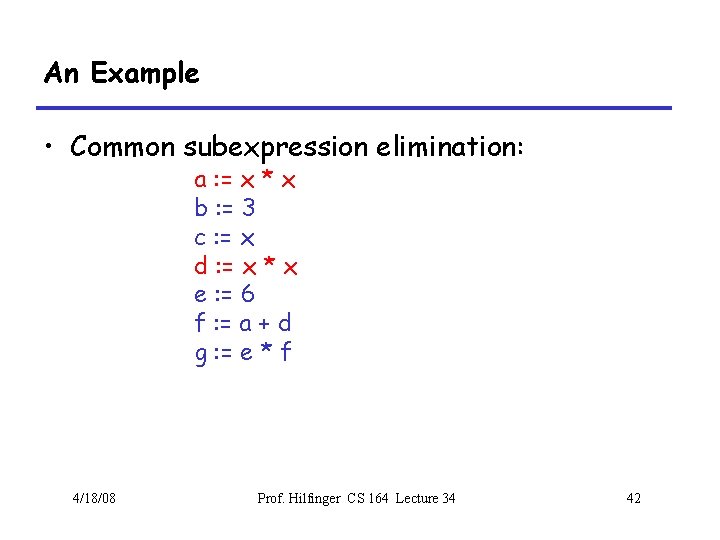

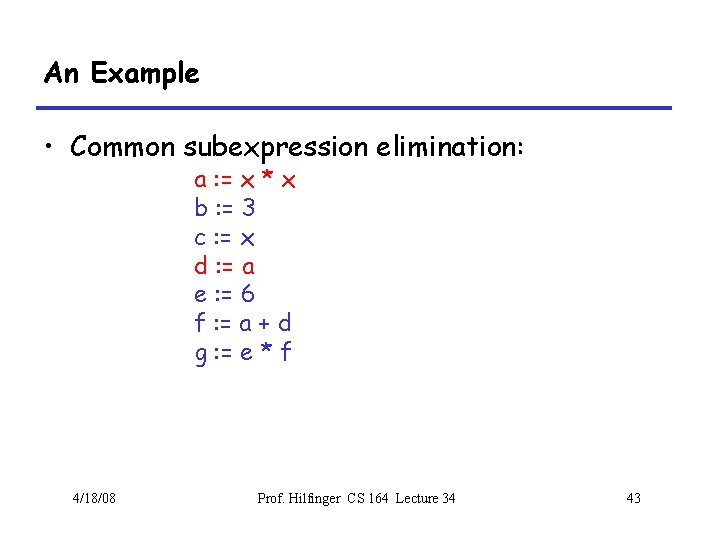

An Example • Common subexpression elimination: a : = x * x b : = 3 c : = x d : = x * x e : = 6 f : = a + d g : = e * f 4/18/08 Prof. Hilfinger CS 164 Lecture 34 42

An Example • Common subexpression elimination: a : = x * x b : = 3 c : = x d : = a e : = 6 f : = a + d g : = e * f 4/18/08 Prof. Hilfinger CS 164 Lecture 34 43

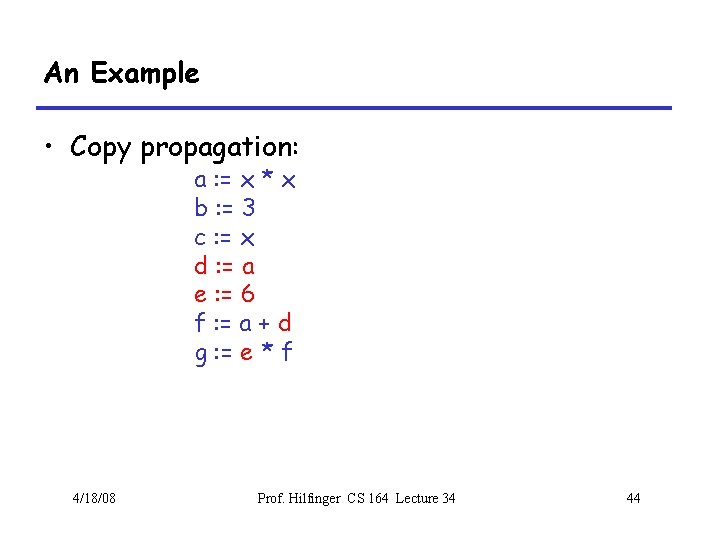

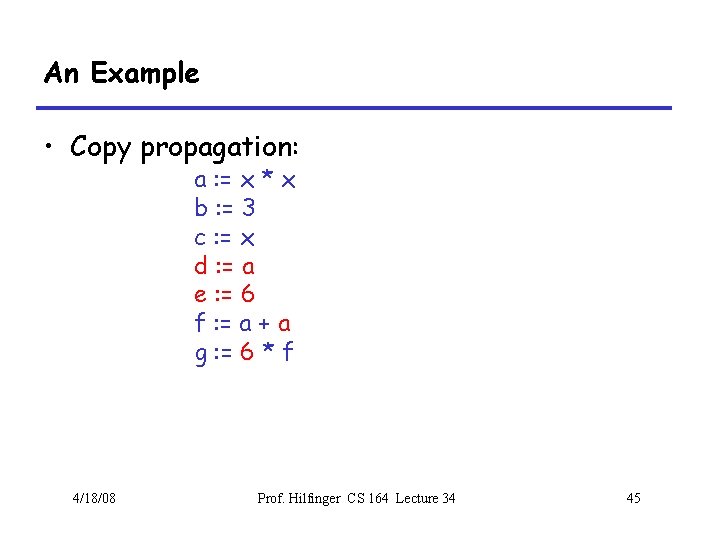

An Example • Copy propagation: a : = x * x b : = 3 c : = x d : = a e : = 6 f : = a + d g : = e * f 4/18/08 Prof. Hilfinger CS 164 Lecture 34 44

An Example • Copy propagation: a : = x * x b : = 3 c : = x d : = a e : = 6 f : = a + a g : = 6 * f 4/18/08 Prof. Hilfinger CS 164 Lecture 34 45

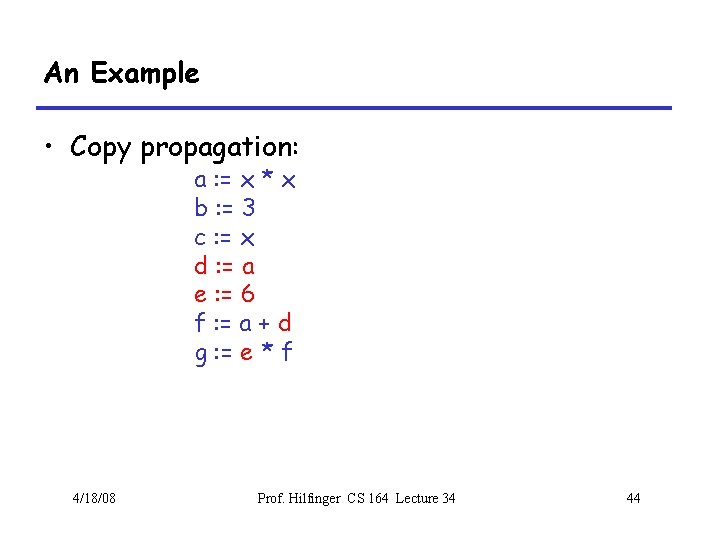

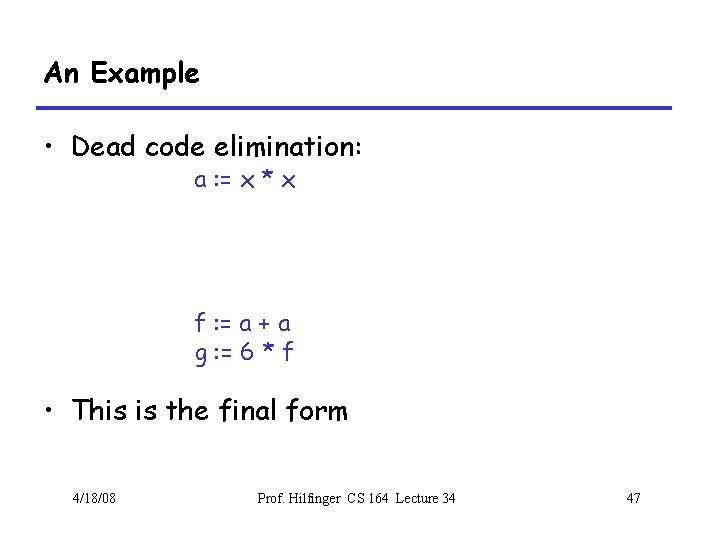

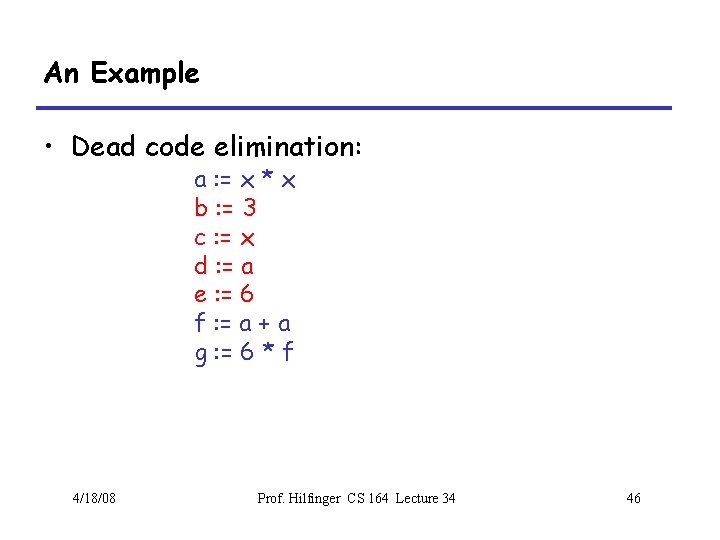

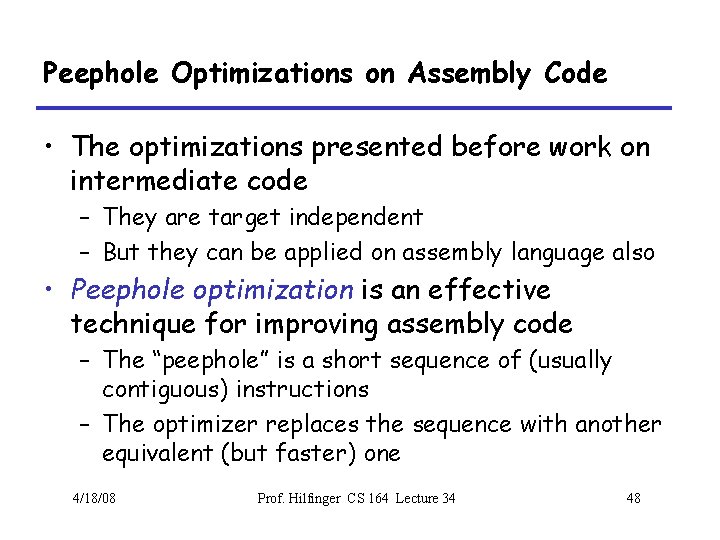

An Example • Dead code elimination: a : = x * x b : = 3 c : = x d : = a e : = 6 f : = a + a g : = 6 * f 4/18/08 Prof. Hilfinger CS 164 Lecture 34 46

An Example • Dead code elimination: a : = x * x f : = a + a g : = 6 * f • This is the final form 4/18/08 Prof. Hilfinger CS 164 Lecture 34 47

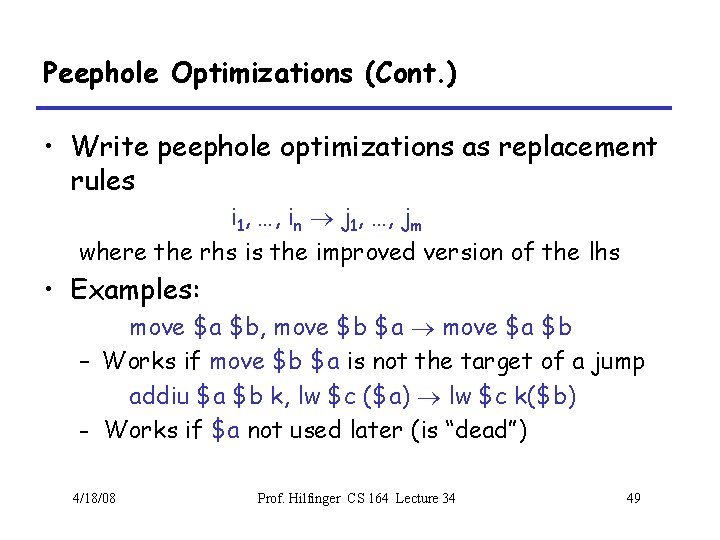

Peephole Optimizations on Assembly Code • The optimizations presented before work on intermediate code – They are target independent – But they can be applied on assembly language also • Peephole optimization is an effective technique for improving assembly code – The “peephole” is a short sequence of (usually contiguous) instructions – The optimizer replaces the sequence with another equivalent (but faster) one 4/18/08 Prof. Hilfinger CS 164 Lecture 34 48

Peephole Optimizations (Cont. ) • Write peephole optimizations as replacement rules i 1, …, in ® j 1, …, jm where the rhs is the improved version of the lhs • Examples: move $a $b, move $b $a ® move $a $b – Works if move $b $a is not the target of a jump addiu $a $b k, lw $c ($a) ® lw $c k($b) - Works if $a not used later (is “dead”) 4/18/08 Prof. Hilfinger CS 164 Lecture 34 49

Peephole Optimizations (Cont. ) • Many (but not all) of the basic block optimizations can be cast as peephole optimizations – Example: addiu $a $b 0 ® move $a $b – Example: move $a $a ® – These two together eliminate addiu $a $a 0 • Just like for local optimizations, peephole optimizations need to be applied repeatedly to get maximum effect 4/18/08 Prof. Hilfinger CS 164 Lecture 34 50

Local Optimizations. Notes. • Intermediate code is helpful for many optimizations • Many simple optimizations can still be applied on assembly language • “Program optimization” is grossly misnamed – Code produced by “optimizers” is not optimal in any reasonable sense – “Program improvement” is a more appropriate term 4/18/08 Prof. Hilfinger CS 164 Lecture 34 51

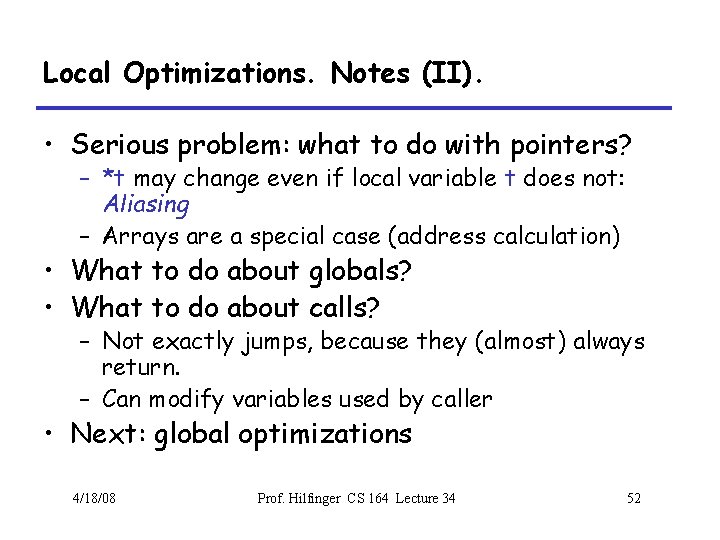

Local Optimizations. Notes (II). • Serious problem: what to do with pointers? – *t may change even if local variable t does not: Aliasing – Arrays are a special case (address calculation) • What to do about globals? • What to do about calls? – Not exactly jumps, because they (almost) always return. – Can modify variables used by caller • Next: global optimizations 4/18/08 Prof. Hilfinger CS 164 Lecture 34 52