ORBITAL CT SCAN Interpretation of CT imaging of

ORBITAL CT SCAN Interpretation of CT imaging of the eye and orbit A systematic approach Prof. Ahmad Mostafa 2014

Introduction n A simple question anyone might ask at this stage is: n Why should an ophthalmologist learn to interpret CT scans? n Why not just read the radiologist's report and proceed? " 2014

n n n Computed tomography (CT) is an important imaging tool in the evaluation of most orbital and some ocular lesions. This technique allows us to diagnose the location, extent and configuration of the lesion and its effect on adjacent structures. It also allows us to comment on the possible tissue mass composition. In addition, knowing the precise location of a lesion facilitates the planning of an appropriate surgical approach to minimise morbidity. A general ophthalmologist should have the ability to review a CT scan by himself, especially if orbital diseases and ocular oncology areas of his special interest. 2014

The CT machine Evolution and Principle n n n On their way through tissues, X-rays are attenuated due to absorption of energy. This "attenuation" is determined by the atomic number of the major tissue constituent. Different tissues provide different degrees of X -ray attenuation, attenuation and it is this property that forms the basis of all imaging techniques. 2014

n n n Plain radiography involves X-rays that pass through the patient, and create an image directly on a photographic film. A three-dimensional structure is thus depicted on a two dimensional plane, Moreover, its sensitivity to small differences in the attenuation is low, low i. e. , its contrast resolution is poor In traditional tomography, tomography the X-ray tube and the film is moved simultaneously in such a way that only a thin plane through the patient is imaged sharply, while structures located in other planes s become blurred 2014

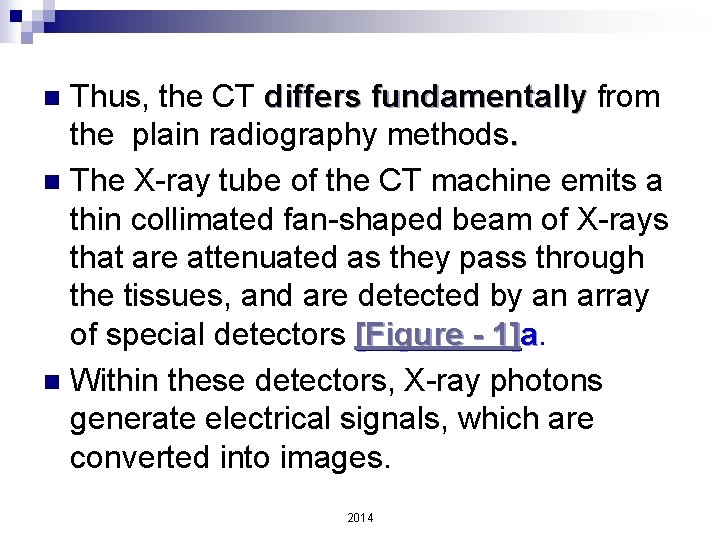

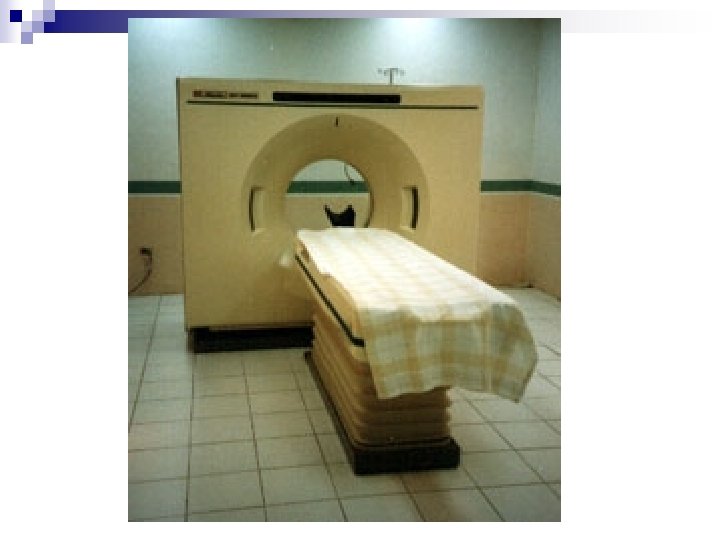

Thus, the CT differs fundamentally from the plain radiography methods. n The X-ray tube of the CT machine emits a thin collimated fan-shaped beam of X-rays that are attenuated as they pass through the tissues, and are detected by an array of special detectors [Figure - 1]a. n Within these detectors, X-ray photons generate electrical signals, which are converted into images. n 2014

2014

2014

2014

High density areas are depicted as white whereas low density areas appear black. n The CT images contain information from thin slices of tissue only, only and are thus devoid of superimposition. n The result contrast resolution is far superior to projection X-ray techniques. n 2014

n n n Recent technological advances have greatly enhanced the applications of CT scan. Today, it can be used for imaging any part of the body, and its role in the diagnosis of ocular and orbital disorders is well established. The widespread use of CT is accompanied by an excessive technical and radiological expressions. n An intimate knowledge of this, however, is not necessary to interpret a CT scan, just as it is not necessary to understand the complexities of a personal computer to benefit from it. 2014

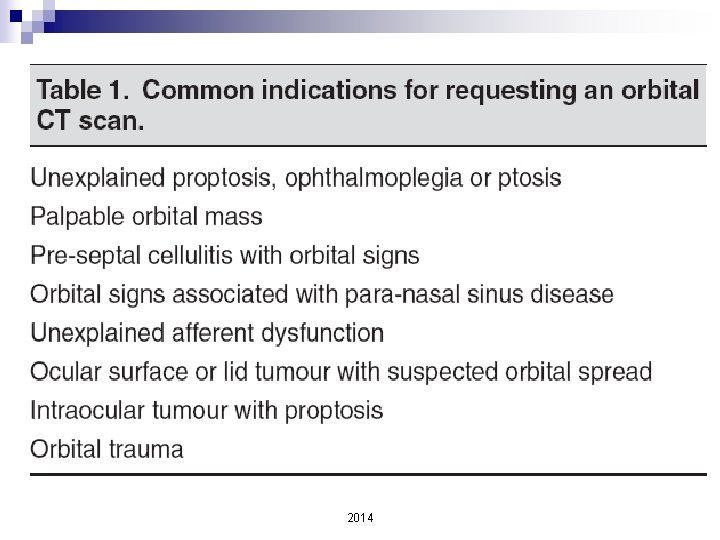

Requesting a CT Scan (Indications) n The list of indications for CT scanning of the orbit is exhaustive. n However, The common indications for CT scanning of the orbit are given in [Table - 1]. 2014

2014

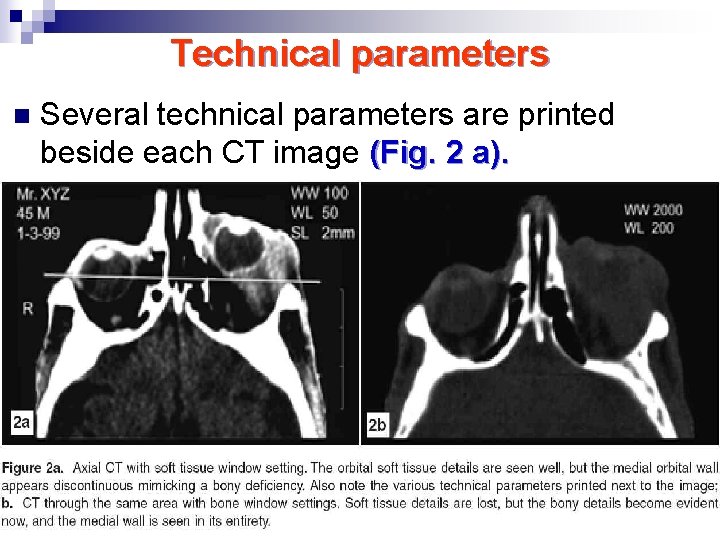

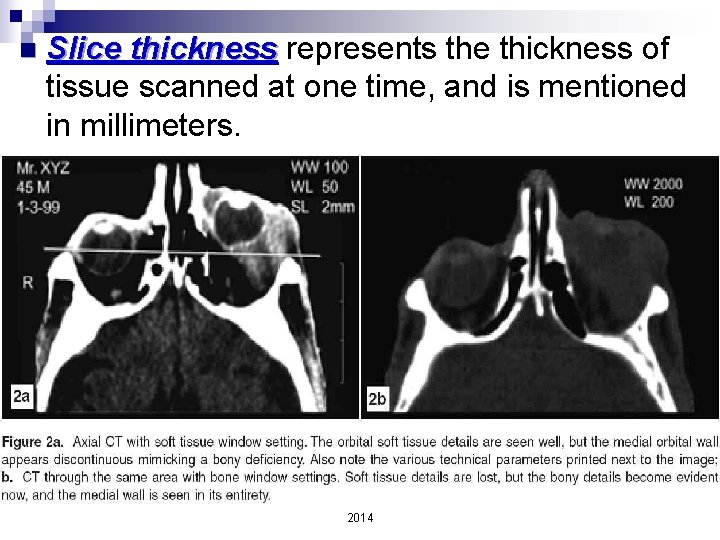

Technical parameters n Several technical parameters are printed beside each CT image (Fig. 2 a). 2014

n Though their location and number varies across machines, some common and important ones include: include Slice thickness n Scan time n Hounsfield number n Window width n Window level n 2014

n Slice thickness represents the thickness of tissue scanned at one time, and is mentioned in millimeters. 2014

Scan time represents the time taken (in seconds) to image each tissue slice. n The ideal scan time is less than 1 -2 seconds per image. n A longer scan time (few seconds) can lead to motion artifacts (especially in children and uncooperative patients) and the findings need to be interpreted in that condition. n 2014

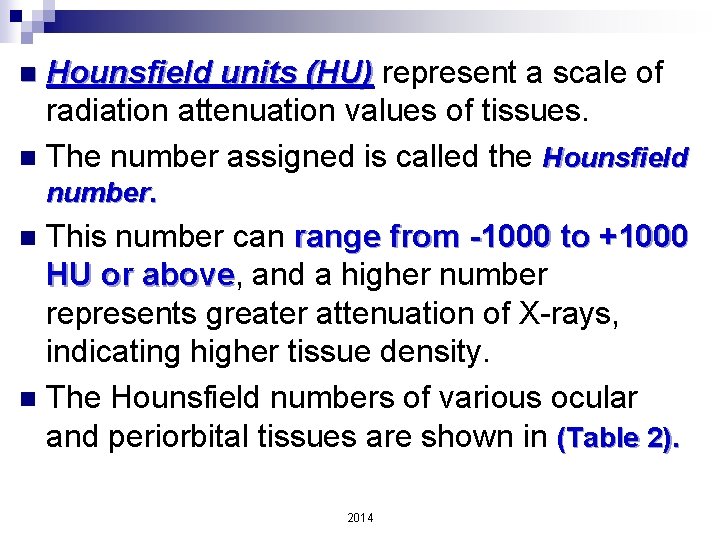

Hounsfield units (HU) represent a scale of radiation attenuation values of tissues. n The number assigned is called the Hounsfield n number. This number can range from -1000 to +1000 HU or above, above and a higher number represents greater attenuation of X-rays, indicating higher tissue density. n The Hounsfield numbers of various ocular and periorbital tissues are shown in (Table 2). n 2014

2014

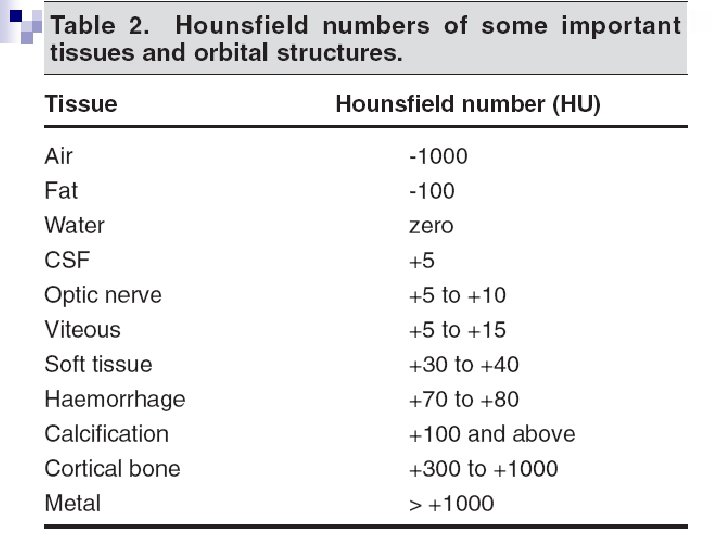

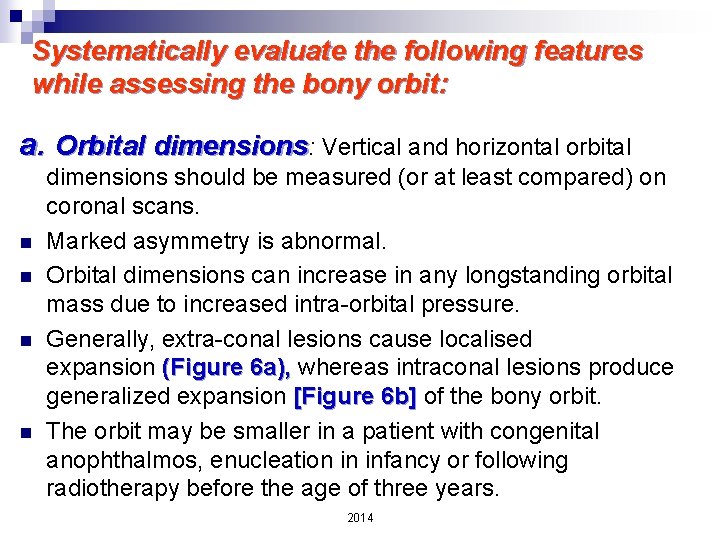

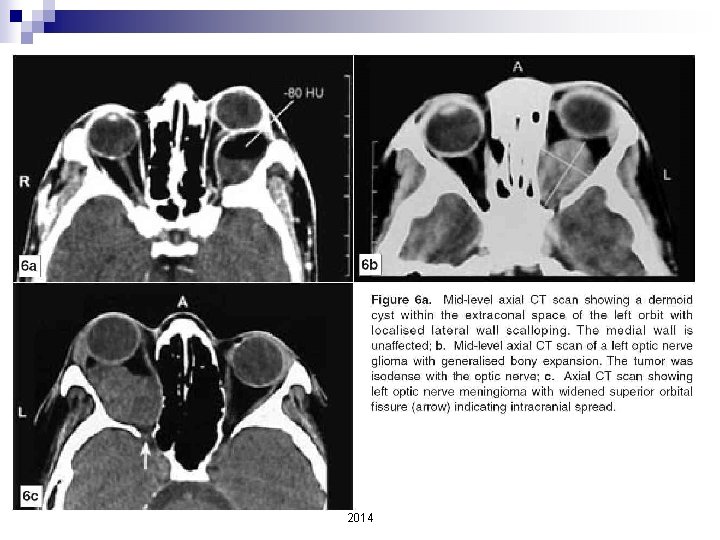

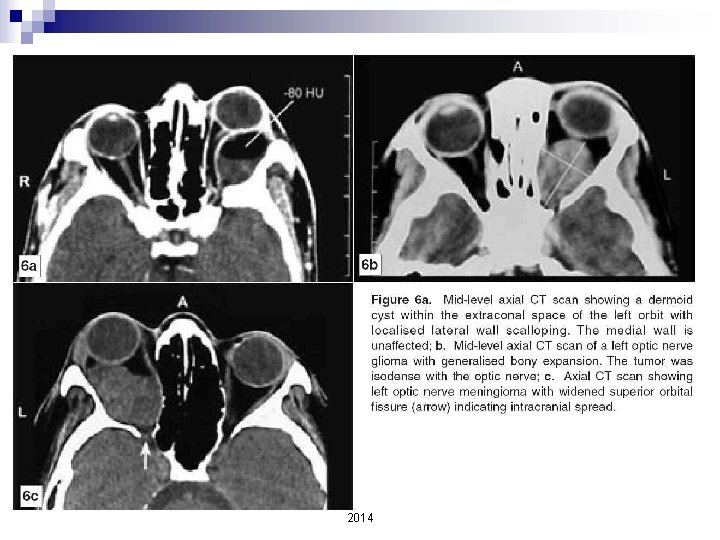

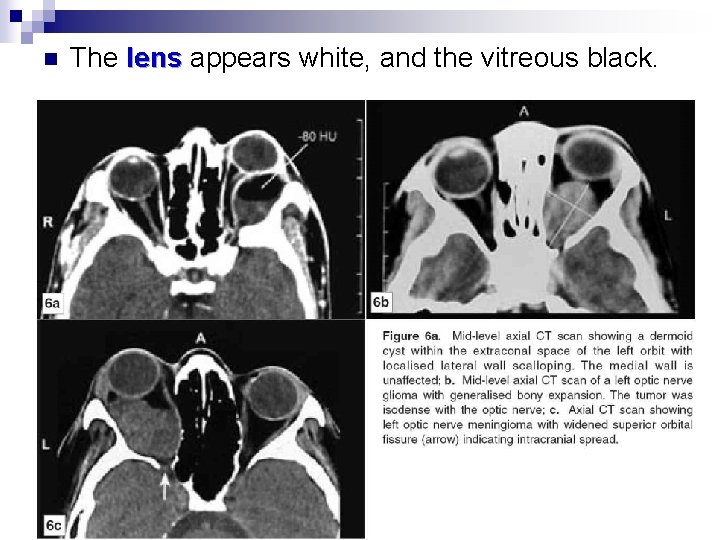

n n This can aid in the differential diagnosis For example, example a dermoid cyst (Fig. 6 a) will have a Hounsfield number below zero due to its fat content, whereas a haematoma, will have a number of +70 to + 80 HU. 2014

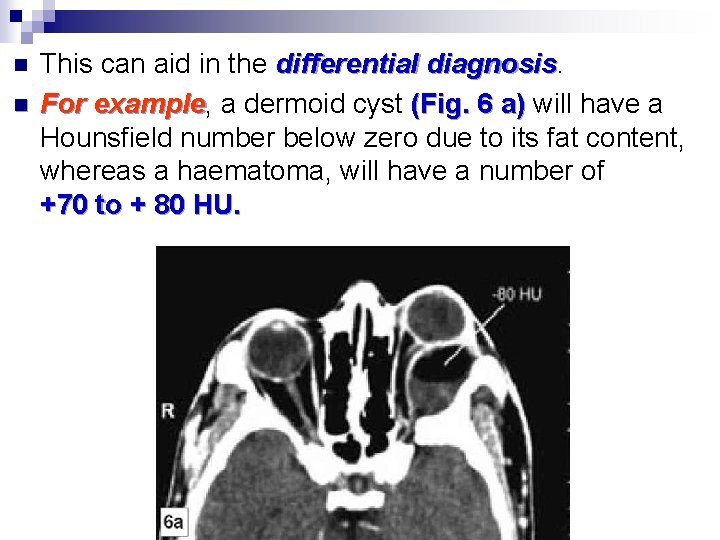

n n n Window width (WW) refers to the span of CT numbers on the Hounsfield scale that are selected to display the given image. It can vary from a few CT numbers to the entire range available on the system. Since the Hounsfield scale usually ranges from -1000 to +1000 HU or above, the maximum WW can be approximately 2000. Thus at a WW of 2000, air will be black and bone will be white. The rest of the tissues will be depicted in shades of gray between these two extremes of the spectrum. A wider WW thus depicts a large number of tissues, and bone details can be better appreciated. 2014

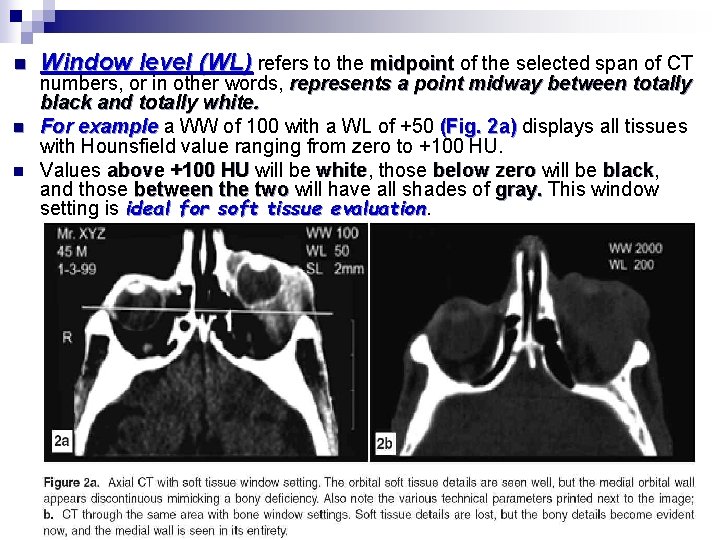

n n n Window level (WL) refers to the midpoint of the selected span of CT numbers, or in other words, represents a point midway between totally black and totally white. For example a WW of 100 with a WL of +50 (Fig. 2 a) displays all tissues with Hounsfield value ranging from zero to +100 HU. Values above +100 HU will be white, white those below zero will be black, black and those between the two will have all shades of gray. This window setting is ideal for soft tissue evaluation 2014

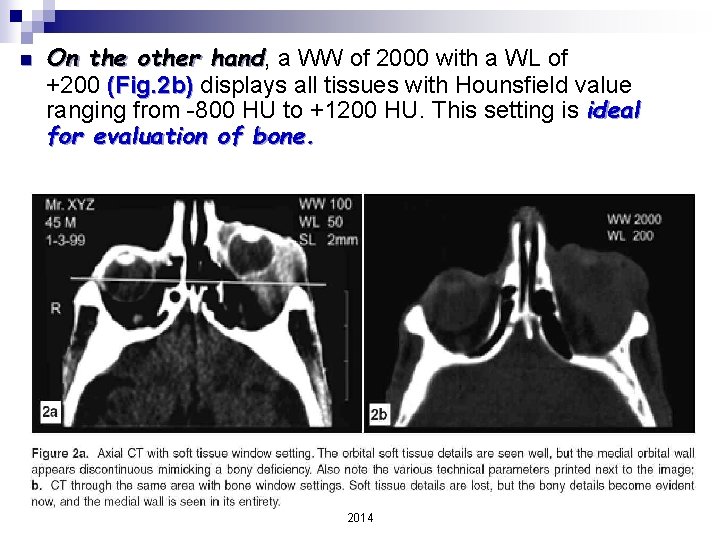

n On the other hand, hand a WW of 2000 with a WL of +200 (Fig. 2 b) displays all tissues with Hounsfield value ranging from -800 HU to +1200 HU. This setting is ideal for evaluation of bone. 2014

Major Considerations n n n CT scan is most informative when the ophthalmologist seeks active participation of the radiologist in the diagnostic workup. The clinical information supplied by the referring ophthalmologist is used by the radiologist both in the selection of appropriate techniques for imaging, and in deriving the most specific conclusion. Failure to communicate the patient's clinical data and the need for special scans to the radiologist is the most common cause for falsely negative CT scans. 2014

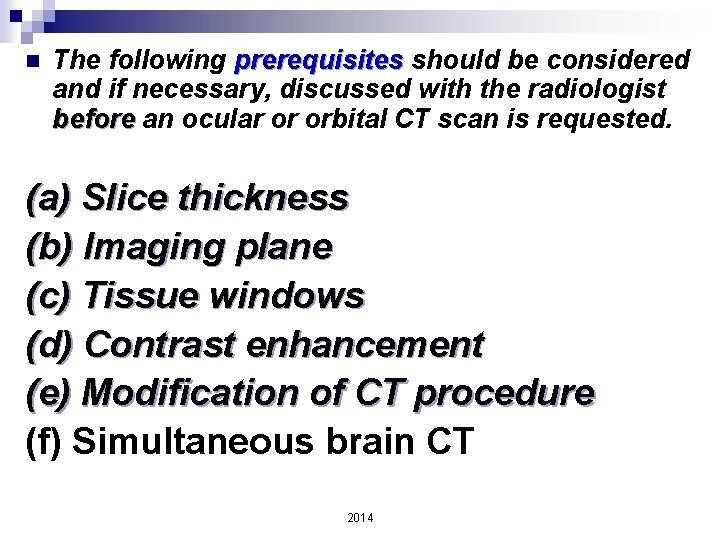

n The following prerequisites should be considered and if necessary, discussed with the radiologist before an ocular or orbital CT scan is requested. (a) Slice thickness (b) Imaging plane (c) Tissue windows (d) Contrast enhancement (e) Modification of CT procedure (f) Simultaneous brain CT 2014

(a) Slice thickness n n n n Spatial resolution of a CT depends on slice thickness. The thinner the slice, the higher the resolution. The slice thickness can varies from 1 -10 mm. mm Thin slices are good for spatial resolution, but require higher radiation dose, a greater number of slices, and eventually longer examination time. The choice of slice thickness therefore is a balance of these factors. Usually, 2 mm cuts are optimal for the eye and orbit. In special situations (like evaluation of the orbital apex), apex thinner slices of 1 mm can be more informative. 2014

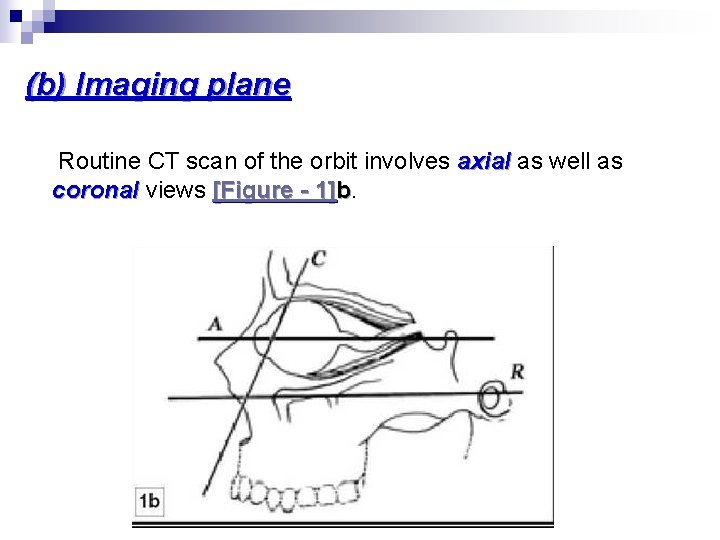

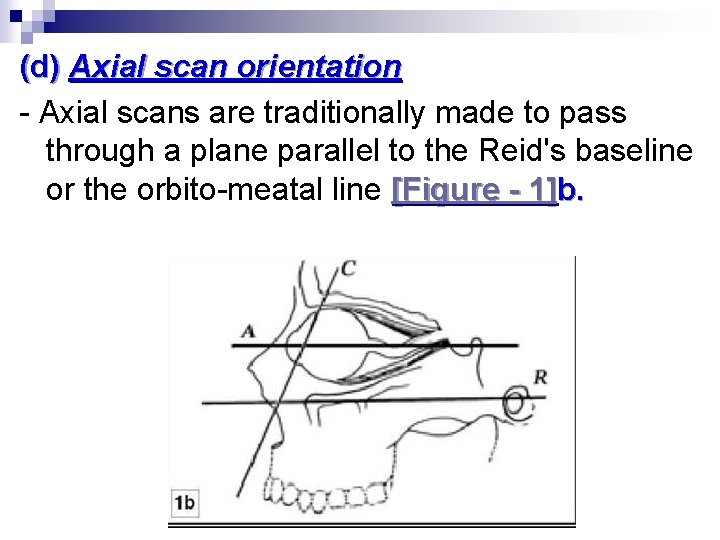

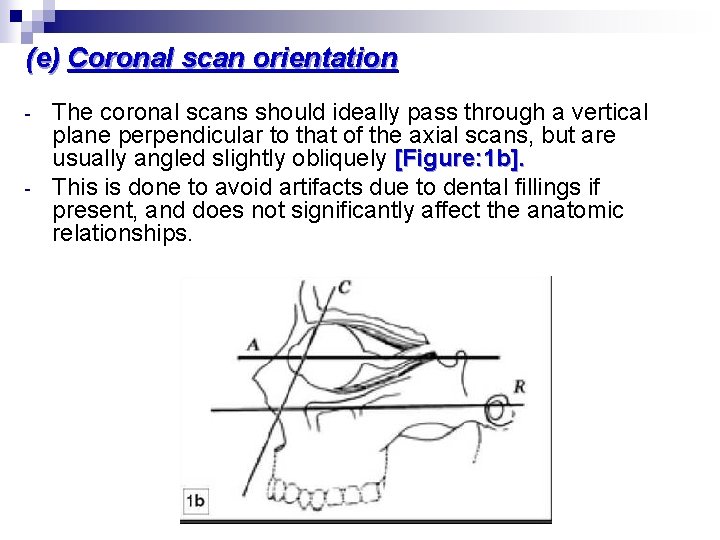

(b) Imaging plane Routine CT scan of the orbit involves axial as well as coronal views [Figure - 1]b. 2014

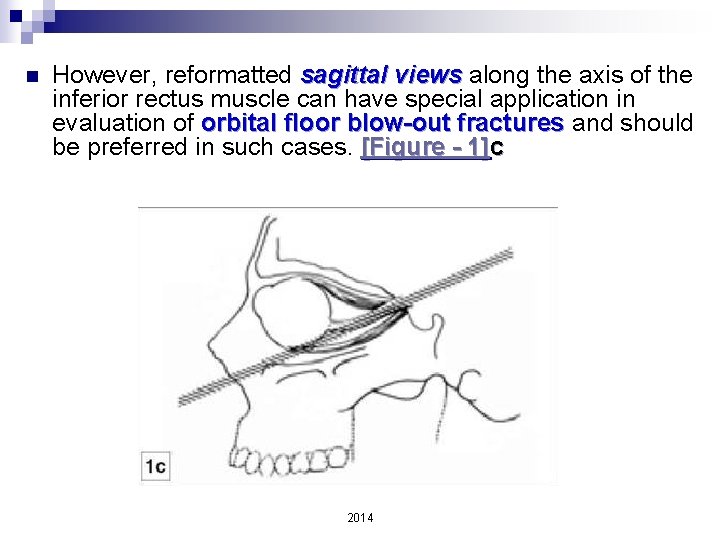

n However, reformatted sagittal views along the axis of the inferior rectus muscle can have special application in evaluation of orbital floor blow-out fractures and should be preferred in such cases. [Figure - 1]c 2014

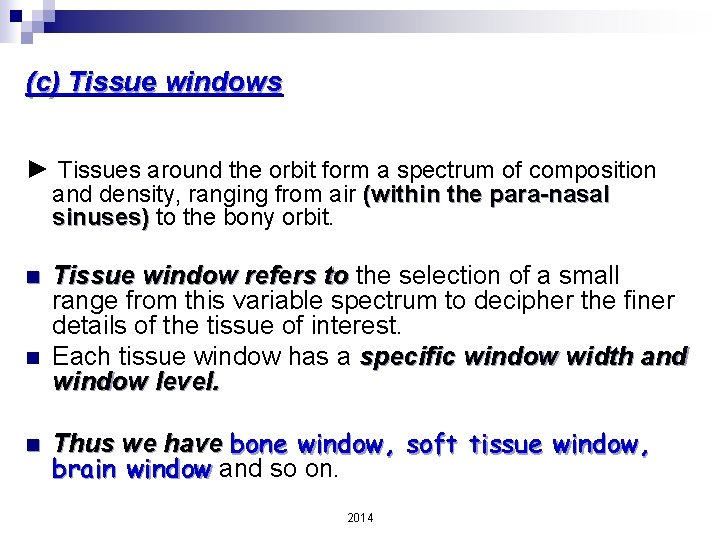

(c) Tissue windows ► Tissues around the orbit form a spectrum of composition and density, ranging from air (within the para-nasal sinuses) to the bony orbit. n n n Tissue window refers to the selection of a small range from this variable spectrum to decipher the finer details of the tissue of interest. Each tissue window has a specific window width and window level. Thus we have bone window, soft tissue window, brain window and so on. 2014

n A thorough evaluation of any tissue is possible only when it is scanned under appropriate window settings: n Soft-tissue window is best for evaluating orbital soft tissue lesions, whereas fractures and bony details are better seen with bone window settings. n Though tissue windows are selected by the radiologist, it is important for the ophthalmologist to be familiar with the concept 2014

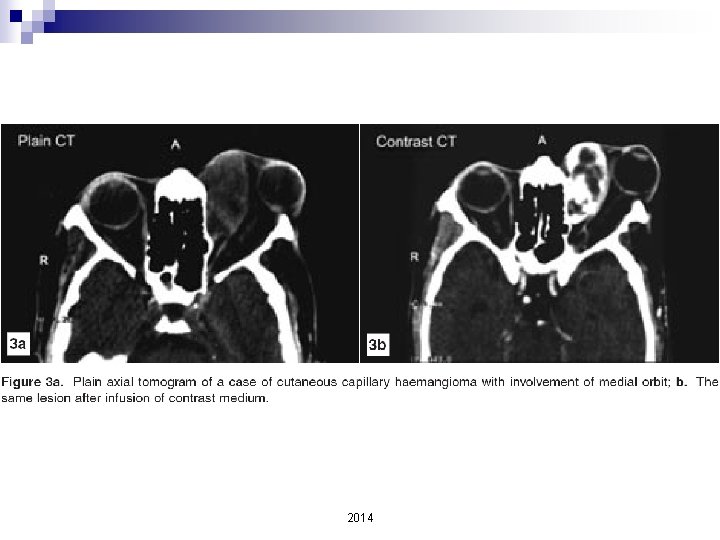

(d) Contrast enhancement n n Contrast study involves imaging the area of interest after intravenous injection of a radiological contrast medium [Figure - 3]a and [Figure - 3]b. Fortunately, orbital fat provides intrinsic background contrast, and most orbital pathologies can be easily visualised without infusion of a contrast medium. However, in certain situations, situations a contrast medium is essential. A contrast-enhancing lesion is one which becomes bright or more intense after contrast medium infusion. 2014

2014

Evaluation of optic chiasma, perisellar region and extra-orbital extensions of orbital tumors is best possible with contrast enhancement. n Contrast enhancement also helps to define vascular and cystic lesions as well as optic nerve lesions, lesions particularly meningioma and glioma. n n In short, the use of contrast enhancement is not routinely necessary for orbital pathologies unless they have intra-cranial extension, and its use is best left to the discretion of the radiologist. 2014

(e) Modification of CT procedure n n Certain cases may require special modifications during the scanning procedure to aid diagnosis. For example, example in a suspected case of orbital venous varix, varix in addition to the routine cuts, it is important to request for special scans (with contrast) while the patient performs a Valsalva maneuver 2014

(f) Simultaneous brain CT n n In certain situations it is mandatory to request CT brain along with that of the orbit. These include: 1. suspected neurocysticercosis with orbital involvement 2. head injury with orbital trauma 3. optic nerve meningiomas, 4. bilateral heritable retinoblastomas (to rule out pinealoblastoma), and 5. suspected perisellar lesions. 2014

Components of a CT Scan Plate 2014

For a complete and systematic evaluation of any CT scan, it is mandatory to familiarize oneself with the CT plates. n Unlike a plain radiograph, a CT scan usually provides three to four plates, each carrying multiple sequentially arranged images, with and without contrast. n Since we need to view sagittal and coronal images together, it is ideal to have a large X -ray viewer board which can simultaneously display at least two plates. n 2014

The various components of a CT plate can be categorized under the following headings: (a) Patient data - This includes the name, age, sex of the patient as well as the date of the CT scan. - It is always necessary to confirm that you are looking at the correct CT of the specific patient, done at the specific time before you begin to interpret. 2014

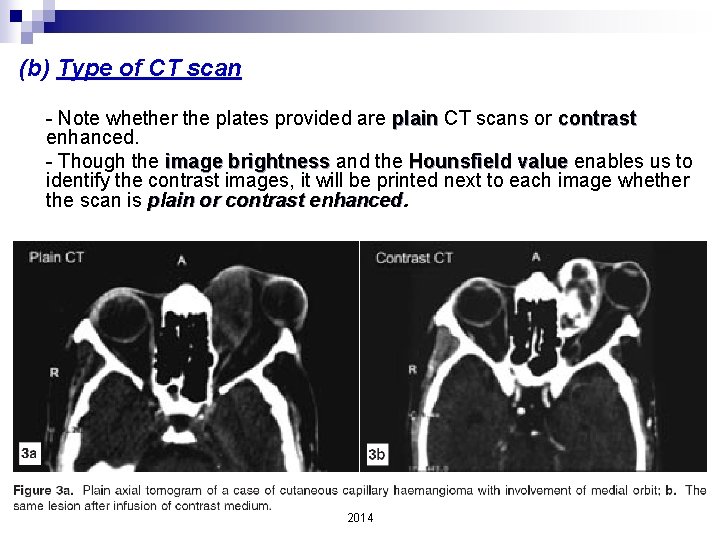

(b) Type of CT scan - Note whether the plates provided are plain CT scans or contrast enhanced. - Though the image brightness and the Hounsfield value enables us to identify the contrast images, it will be printed next to each image whether the scan is plain or contrast enhanced. 2014

(c) Laterality - Though the eye depicted on the right side of the image usually depicts the right eye, it is important to note that these conventions are not universal. - Therefore, the best way to confirm laterality is to look for the "R" or "L" mark which represents right or left respectively 2014

(d) Axial scan orientation - Axial scans are traditionally made to pass through a plane parallel to the Reid's baseline or the orbito-meatal line [Figure - 1]b. 2014

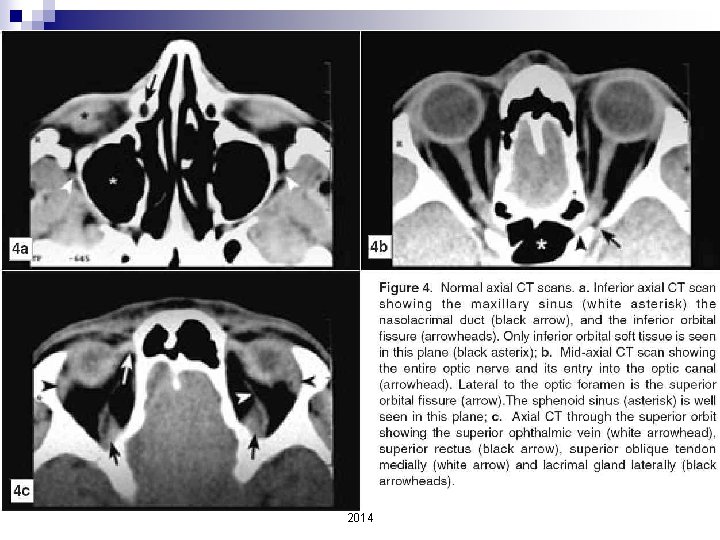

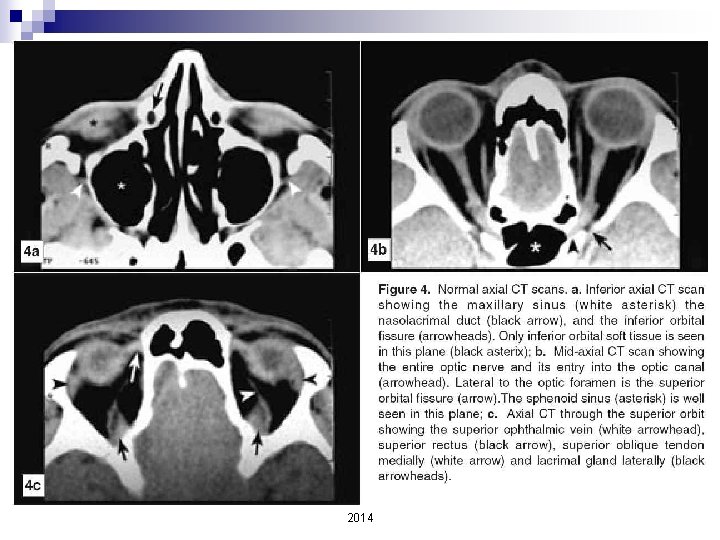

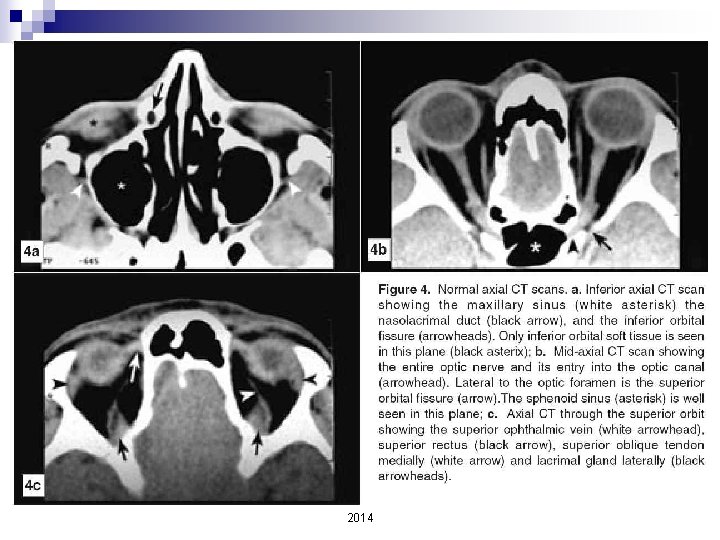

- To orient yourself to the axial scans, always begin with the lateral scout view depicted as a plain radiogram that shows the exact location of planes chosen for axial slices. - It is usually displayed as the first image on the plate, preceding the serial axial images. - A simple way to identify the level of the axial slice is to note that as we move from inferior to superior, superior the prominence of the nose flattens out anteriorly, and increasingly more brain parenchyma appears posteriorly. - Slices that depict the lens represent the mid-level axial plane [Figure - 4]. 2014

n Therefore, according to the level in the orbital cavity, we will have: ¨ A. Inferior axial orbital CT scan ¨ B. Mid-axial orbital CT scan ¨ C. Superior axial orbital CT scan 2014

2014

(e) Coronal scan orientation - - The coronal scans should ideally pass through a vertical plane perpendicular to that of the axial scans, but are usually angled slightly obliquely [Figure: 1 b]. This is done to avoid artifacts due to dental fillings if present, and does not significantly affect the anatomic relationships. 2014

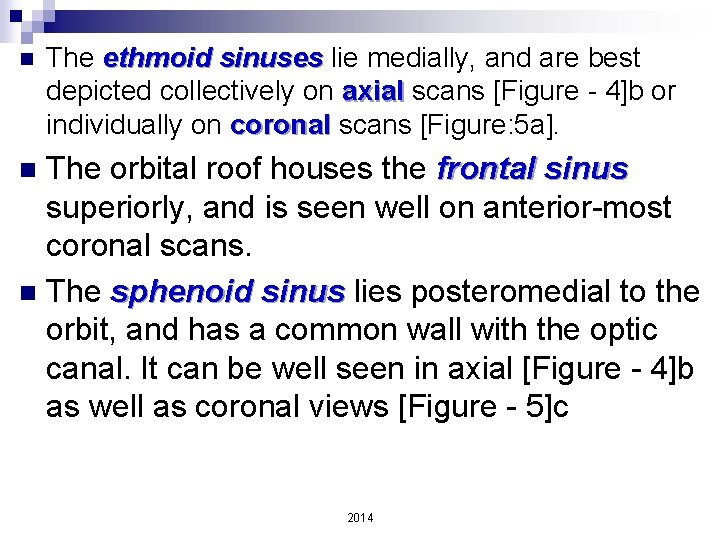

- - Evaluation of the coronal scans too, should begin with the lateral scout view. Coronal images are arranged to progress from anterior plane to posterior plane within the orbit. One must remember, that because of the oblique direction of coronal scans, the first few anterior images do not show the orbital floor. 2014

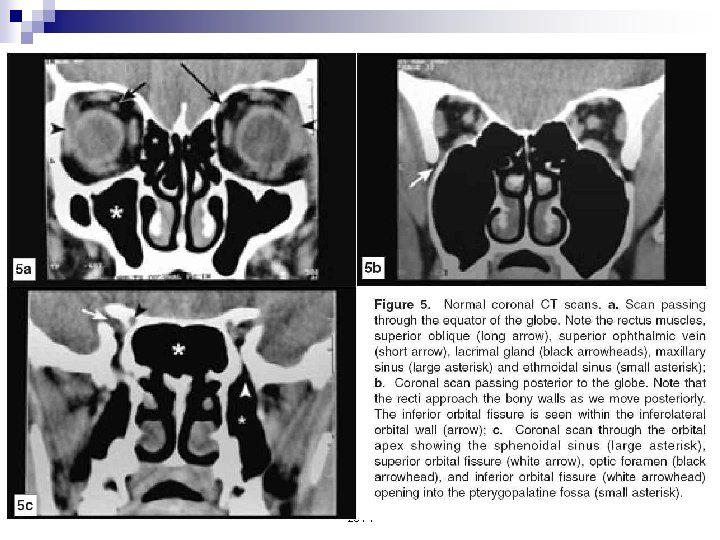

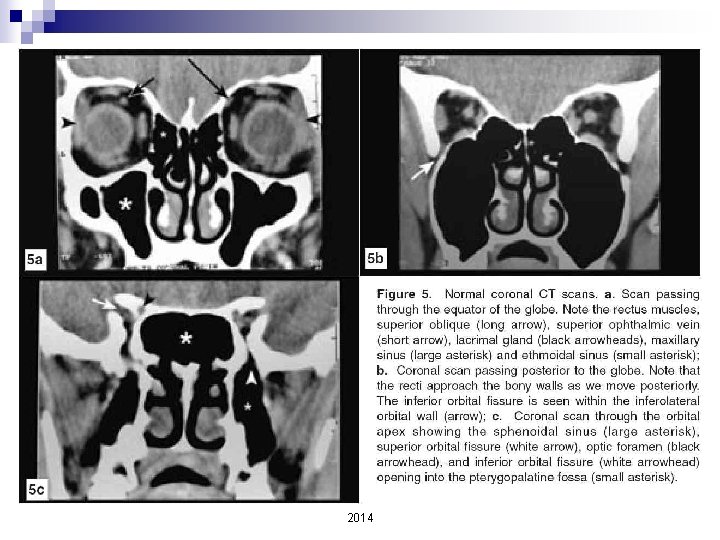

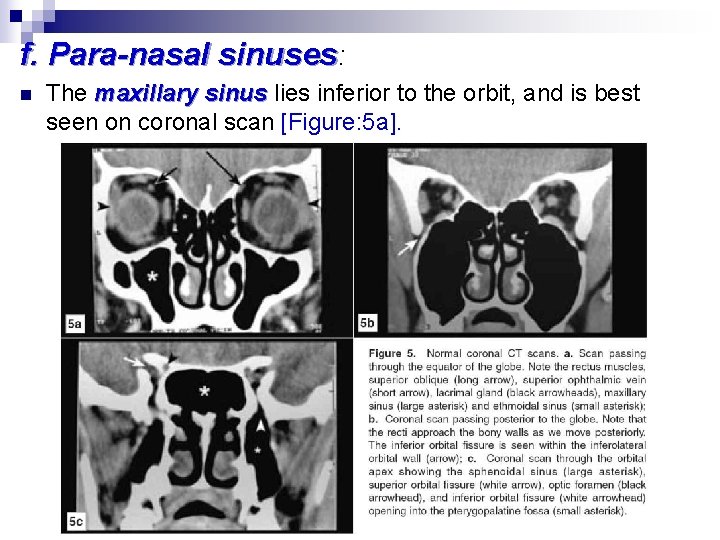

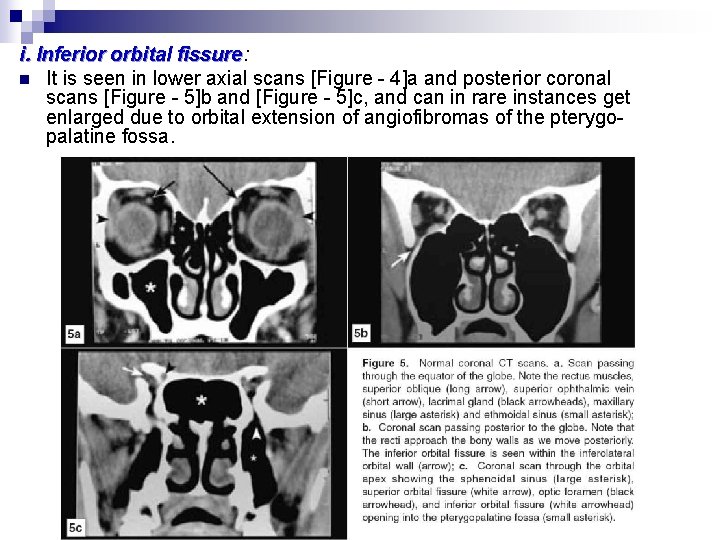

- - If a given image depicts the globe, it is an anterior coronal section [Figure - 5]a. The image with maximum globe diameter roughly represents the equator of the eyeball. A posterior coronal section is devoid of the globe image, and demonstrates the optic nerve and extra ocular muscles [Figure - 5]b. The cross-sectional size of the orbital cavity reduces as we move to the posterior [Figure - 5]. 2014

2014

Systematic Evaluation of Ocular and Orbital Structures on CT 2014

n CT evaluation is most convenient and informative if performed on the CT machine screen itself But this is not practical. One almost always has to read the hard copy plates sent by the radiologist. 2014

n We aim to describe the important structures, which can be divided into the following sub-headings so as to perform a systematic evaluation without missing any diagnostic clue. n 1. Bony orbit n 2. The eyeball n 3. Extra-ocular muscles n 4. Extraconal tissues n 5. Intraconal tissues n 6. Sella and para-sellar regions 2014

1. The bony orbit Begin your evaluation with the bony orbital wall. n The axial view is preferred for evaluating the lateral and medial wall, superior orbital fissure, and the optic canal [Figure - 4]. n The orbital floor and roof are best seen in coronal views [Figure - 5]. n 2014

2014

2014

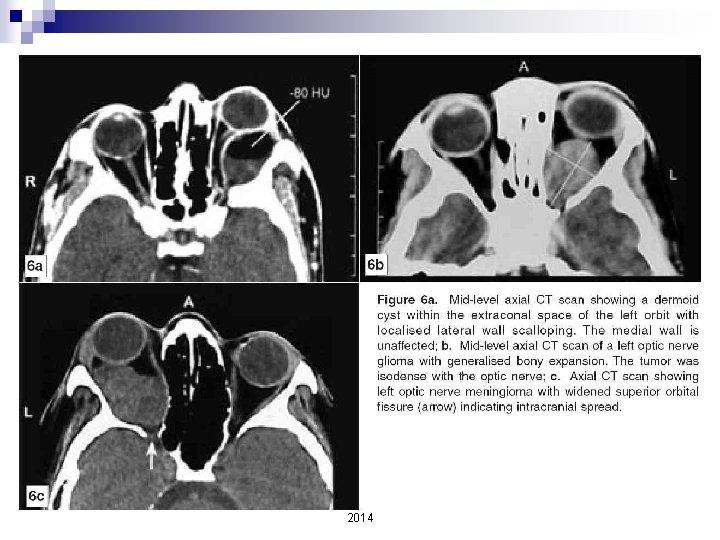

Systematically evaluate the following features while assessing the bony orbit: a. Orbital dimensions: Vertical and horizontal orbital n n dimensions should be measured (or at least compared) on coronal scans. Marked asymmetry is abnormal. Orbital dimensions can increase in any longstanding orbital mass due to increased intra-orbital pressure. Generally, extra-conal lesions cause localised expansion (Figure 6 a), whereas intraconal lesions produce generalized expansion [Figure 6 b] of the bony orbit. The orbit may be smaller in a patient with congenital anophthalmos, enucleation in infancy or following radiotherapy before the age of three years. 2014

2014

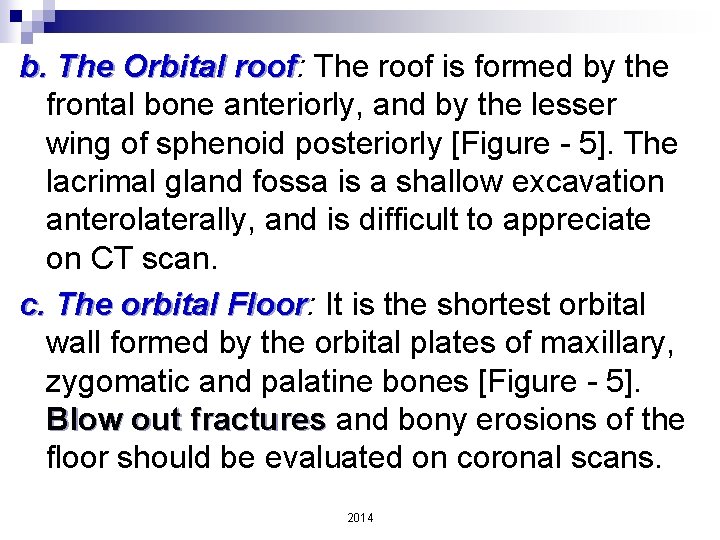

b. The Orbital roof: roof The roof is formed by the frontal bone anteriorly, and by the lesser wing of sphenoid posteriorly [Figure - 5]. The lacrimal gland fossa is a shallow excavation anterolaterally, and is difficult to appreciate on CT scan. c. The orbital Floor: Floor It is the shortest orbital wall formed by the orbital plates of maxillary, zygomatic and palatine bones [Figure - 5]. Blow out fractures and bony erosions of the floor should be evaluated on coronal scans. 2014

![d. Medial orbital wall: wall n It can be demonstrated by axial [Figure-4] as d. Medial orbital wall: wall n It can be demonstrated by axial [Figure-4] as](http://slidetodoc.com/presentation_image_h2/977ee1c1c6e700f71a7e352b8bfc424c/image-58.jpg)

d. Medial orbital wall: wall n It can be demonstrated by axial [Figure-4] as well as coronal scans [Figure - 5], and is formed by the following four bones: frontal process of maxilla, lacrimal, ethmoid, and body of sphenoid. n In lower axial scans, the bony nasolacrimal duct can be occasionally seen within the bony medial wall [Figure - 4]a. 2014

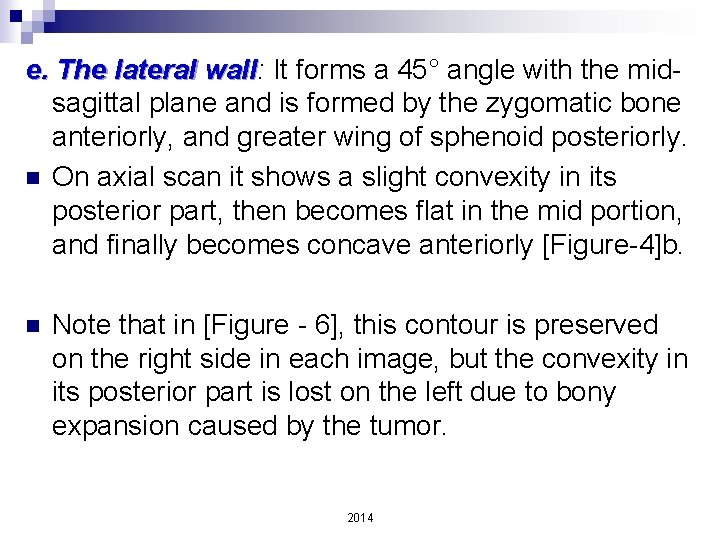

e. The lateral wall: wall It forms a 45° angle with the midsagittal plane and is formed by the zygomatic bone anteriorly, and greater wing of sphenoid posteriorly. n On axial scan it shows a slight convexity in its posterior part, then becomes flat in the mid portion, and finally becomes concave anteriorly [Figure-4]b. n Note that in [Figure - 6], this contour is preserved on the right side in each image, but the convexity in its posterior part is lost on the left due to bony expansion caused by the tumor. 2014

2014

2014

f. Para-nasal sinuses: n The maxillary sinus lies inferior to the orbit, and is best seen on coronal scan [Figure: 5 a]. 2014

n The ethmoid sinuses lie medially, and are best depicted collectively on axial scans [Figure - 4]b or individually on coronal scans [Figure: 5 a]. The orbital roof houses the frontal sinus superiorly, and is seen well on anterior-most coronal scans. n The sphenoid sinus lies posteromedial to the orbit, and has a common wall with the optic canal. It can be well seen in axial [Figure - 4]b as well as coronal views [Figure - 5]c n 2014

2014

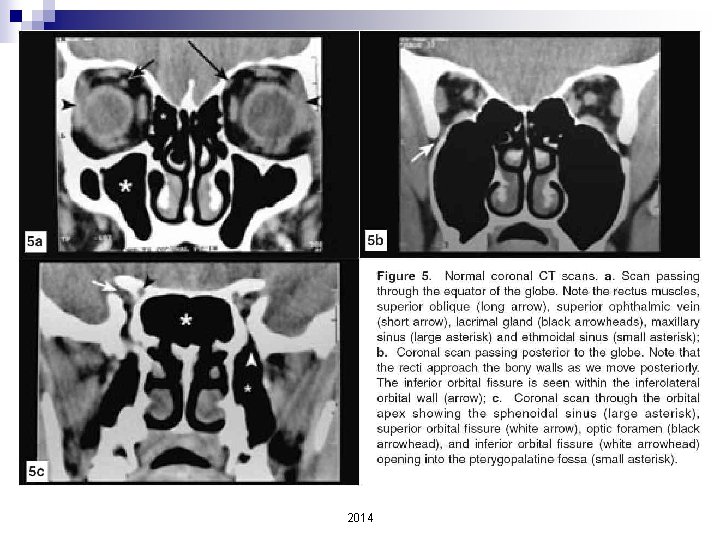

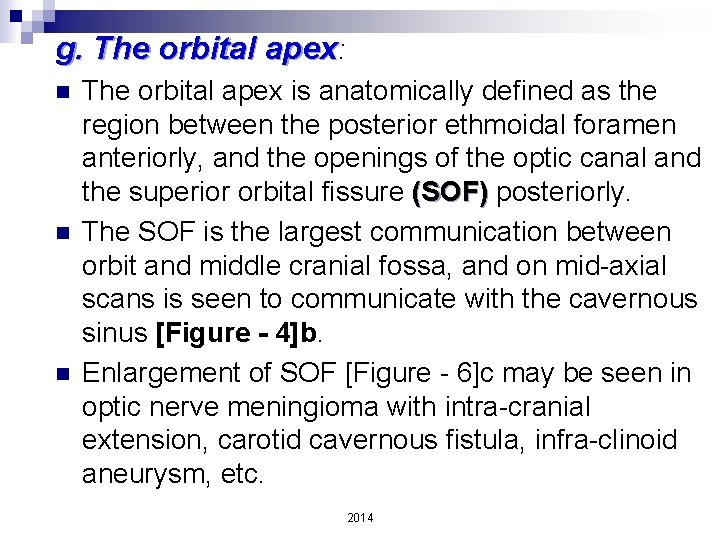

g. The orbital apex: n n n The orbital apex is anatomically defined as the region between the posterior ethmoidal foramen anteriorly, and the openings of the optic canal and the superior orbital fissure (SOF) posteriorly. The SOF is the largest communication between orbit and middle cranial fossa, and on mid-axial scans is seen to communicate with the cavernous sinus [Figure - 4]b. Enlargement of SOF [Figure - 6]c may be seen in optic nerve meningioma with intra-cranial extension, carotid cavernous fistula, infra-clinoid aneurysm, etc. 2014

2014

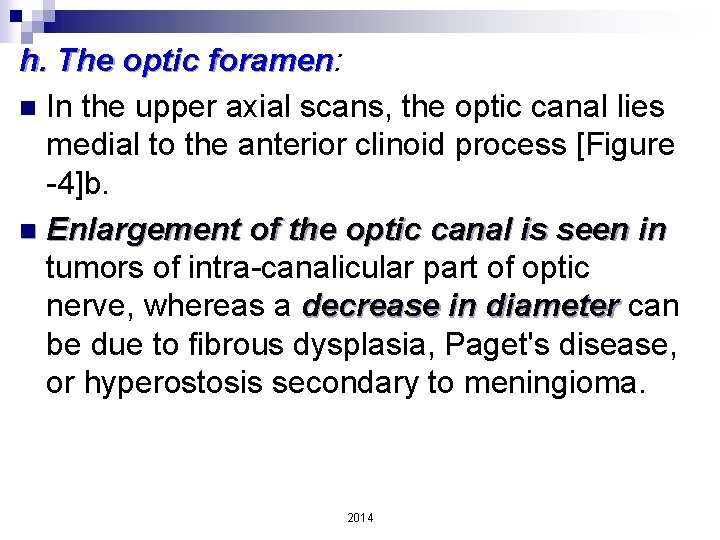

h. The optic foramen: foramen n In the upper axial scans, the optic canal lies medial to the anterior clinoid process [Figure -4]b. n Enlargement of the optic canal is seen in tumors of intra-canalicular part of optic nerve, whereas a decrease in diameter can be due to fibrous dysplasia, Paget's disease, or hyperostosis secondary to meningioma. 2014

i. Inferior orbital fissure: fissure n It is seen in lower axial scans [Figure - 4]a and posterior coronal scans [Figure - 5]b and [Figure - 5]c, and can in rare instances get enlarged due to orbital extension of angiofibromas of the pterygopalatine fossa. 2014

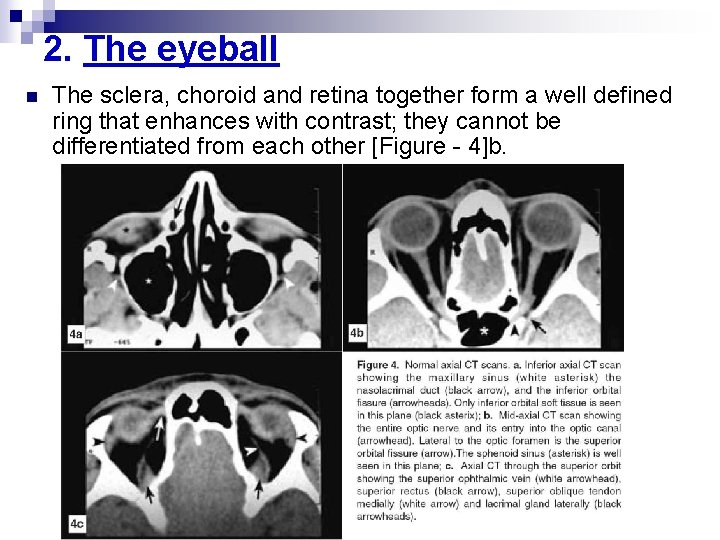

2. The eyeball n The sclera, choroid and retina together form a well defined ring that enhances with contrast; they cannot be differentiated from each other [Figure - 4]b. 2014

n The lens appears white, and the vitreous black. 2014

3. Extra-ocular muscles n n The extraocular muscles are well visualised on CT, and run parallel to the adjacent orbital wall. On axial cuts, only the horizontal recti are seen [Figure - 4]b. The superior and inferior recti, partially seen on axial scans, are visualised on coronal views [Figure - 5]a and [Figure - 5]b. The superior rectus and the levator palpebrae superioris are seen as a single soft tissue shadow on high axial scans [Figure - 4]c and coronal scans [Figure - 5]a and[Figure - 5]b. 2014

n n n The superior oblique is best seen in the coronal view lying supero-medial to the superior rectus [Figure - 5]a, but can also be seen on upper axial scans as it passes through the trochlea [Figure - 4]c. The inferior oblique is the least defined muscle on CT scan; only the insertion is occasionally visible on axial views. The extraocular muscles and the fibrous tissue septa connecting them form the muscle cone and divide the orbit into intraconal and extraconal spaces, a division of radiodiagnostic importance. 2014

Extraocular muscles should be evaluated for the following morphological characteristics on CT scan: n Size: ¨ There is an excellent symmetry between the extraocular muscles of both the orbits, and they are thus comparable in all respects. ¨ Actual measurements are not of much help, in view of fusiform configuration and artifactual asymmetry due to different scanning planes or positions of gaze. ¨ The most common muscle abnormalities relate to variations in muscle diameter. ¨ Enlargement is maximum in case of tumors or cysts; moderate enlargement is seen in thyroid ophthalmopathy, vascular lesions, and myositis. ¨ On the other hand, decreased muscle diameter suggests atrophy from denervation or myopathy. 2014

n Shape: Diffuse enlargement suggests inflammation, venous congestion or infiltration, whereas focal enlargement suggests a neoplasm or a cyst. Tendon involvement suggests myositis. 2014

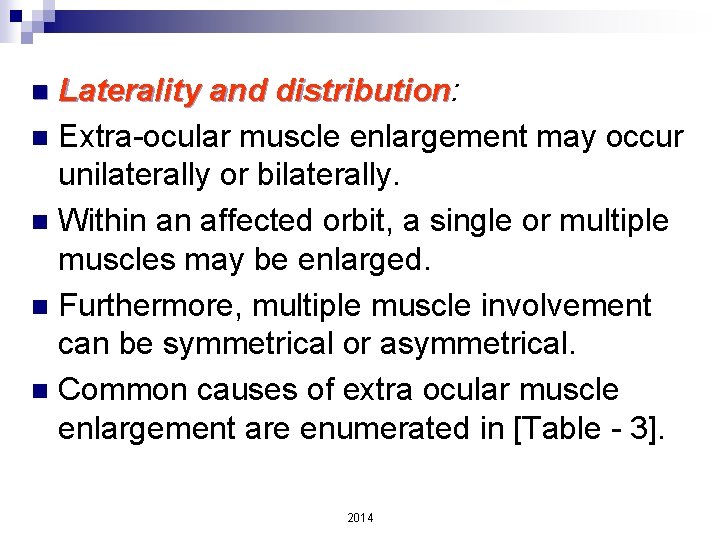

Laterality and distribution: distribution n Extra-ocular muscle enlargement may occur unilaterally or bilaterally. n Within an affected orbit, a single or multiple muscles may be enlarged. n Furthermore, multiple muscle involvement can be symmetrical or asymmetrical. n Common causes of extra ocular muscle enlargement are enumerated in [Table - 3]. n 2014

2014

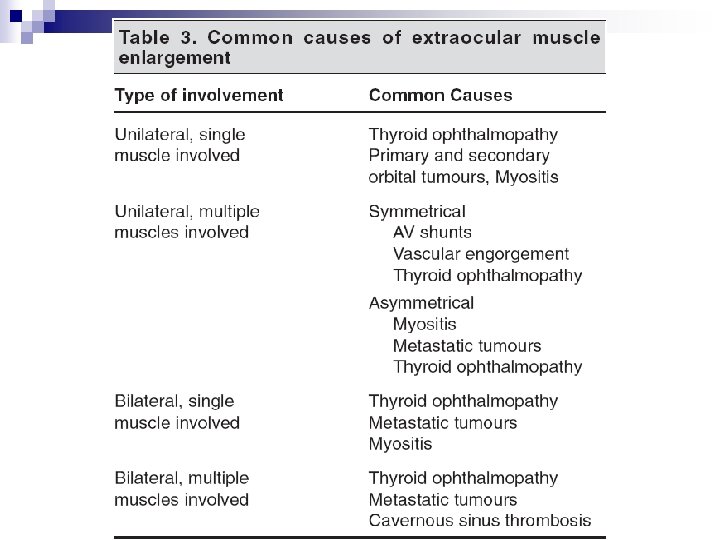

Muscle margin: n Healthy extra-ocular muscles have sharp margins. n Uniform configuration with distinct margins is seen in Graves' myopathy and vascular engorgement. n On the other hand, diffuse infiltration for example by metastatic disease may cause irregular enlargement with indistinct borders. n 2014

Contrast enhancement: enhancement n Normal muscles have moderate contrast enhancement, whereas marked enhancement is seen in thyroid ophthalmopathy or myositis. n Contrast enhancement is variable in arterio -venous fistulas and neoplasms. n 2014

4. Extraconal tissues The lids, conjunctiva, and the orbital septum together form an anterior soft tissue density which on axial scans is seen to extend from the pre-equatorial part of the globe to the lateral and medial orbital margins [Figure-4]b. n The lacrimal gland lies within its fossa superotemporally, and can be seen on high axial [Figure-4]c as well as anterior coronal scans [Figure - 5]a. n 2014

5. Intraconal tissues n The two most important structures within the intraconal space in terms of CT visualisation are: 1. The optic nerve and 2. The superior ophthalmic vein (SOV). 2014

n n n CT evaluation of optic nerve lesions is facilitated by 1. 5 mm axial scans and contrast study. The middle third of the intraorbital part of optic nerve has a slight downward dip [Figure - 1]b. It may therefore appear thinner in this area as a result of partial volume averaging. The entire anterior visual pathway can be seen only when the imaging plane lies -30° to the Reid's Baseline [Figure - 1]c. The patient should fix in upgaze so as to stretch the optic nerve and make it straight. The intracanalicular portion of the nerve is poorly imaged on CT due to absence of intrinsic contrast material and partial volume averaging from the adjacent bone. 2014

n n n The two most commonly occuring optic nerve tumours are glioma and meningioma. Gliomas usually occur in children and have fusiform enlargement with sharp delineation from the surrounding tissue [Figure - 6]b. They are isodense with the optic nerve, and show variable enhancement with contrast. Meningiomas are usually found in adults, and show irregular enlargement along the optic nerve [Figure - 6]c. They tend to be hyperdense to the optic nerve, and show a more consistent contrast enhancement. Calcification within the optic nerve shadow is also commonly seen with meningioma. 2014

From the neuro-ophthalmic point of view, the most common conditions that require imaging are optic neuritis, neuritis compressive optic neuropathies and papilloedema n MRI is the imaging modality of choice in optic neuritis, neuritis especially when multiple sclerosis is suspected. n Compressive optic neuropathy commonly has an intra-orbital cause, and papilloedema produces an enlargement of the optic nerve sheath. n 2014

n n n The SOV is an important vascular structure to note. It begins in the superior nasal quadrant near the trochlea, courses posteriorly and laterally beneath the superior rectus, and exits the orbit through the superior orbital fissure. It is seen well on high axial scans [Figure - 4]c as well as coronal scans [Figure - 5]a Drainage is into the cavernous sinus. Normal diameter on coronal scans is 2 mm anteriorly and 3. 5 mm posteriorly above which it is considered abnormal. 2014

6. Sella and para-sellar regions n n n The optic chiasma is more readily identified than the canalicular or intracranial part of the optic nerve, because it is surrounded by cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) in the supra-sellar region. Any mass in the region of chiasma should be considered a pituitary adenoma unless proved otherwise. The chiasma, sella turcica and the pituitary gland are best visualised on coronal sections 2014

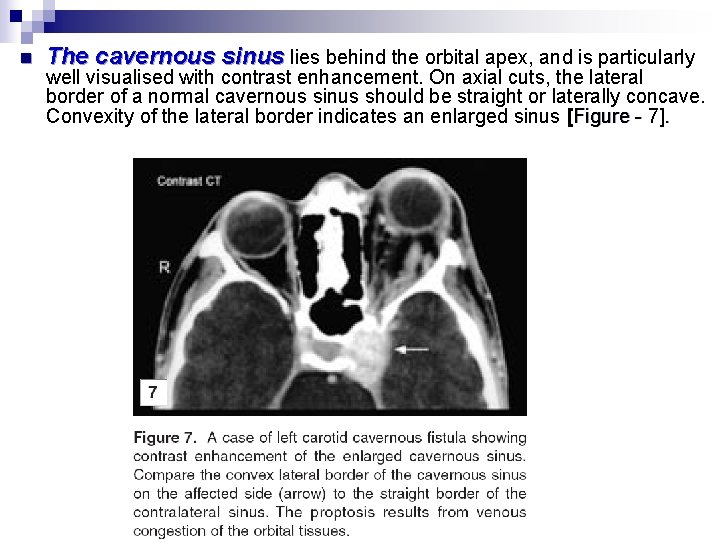

n The cavernous sinus lies behind the orbital apex, and is particularly well visualised with contrast enhancement. On axial cuts, the lateral border of a normal cavernous sinus should be straight or laterally concave. Convexity of the lateral border indicates an enlarged sinus [Figure - 7]. 2014

- Slides: 86