Optimizing Nuclear Physics Codes on the XT 5

- Slides: 58

Optimizing Nuclear Physics Codes on the XT 5 Rebecca J. Hartman-Baker hartmanbakrj@ornl. gov Hai Ah Nam namha@ornl. gov Oak Ridge Leadership Computing Facility Oak Ridge National Laboratory

Outline I. Why Nuclear Physics? II. Nuclear Physics Codes III. Performance Profiling IV. Compiler Optimization V. Compiler Feedback & Hand Tuning VI. Conclusions/Future Work 2

I. WHY NUCLEAR PHYSICS? The band Why? Source: http: //www. clashmusic. com/artists/why 3

I. Why Nuclear Physics? • Nuclear physics important to fundamental understanding of the universe • Useful for broad applications 4

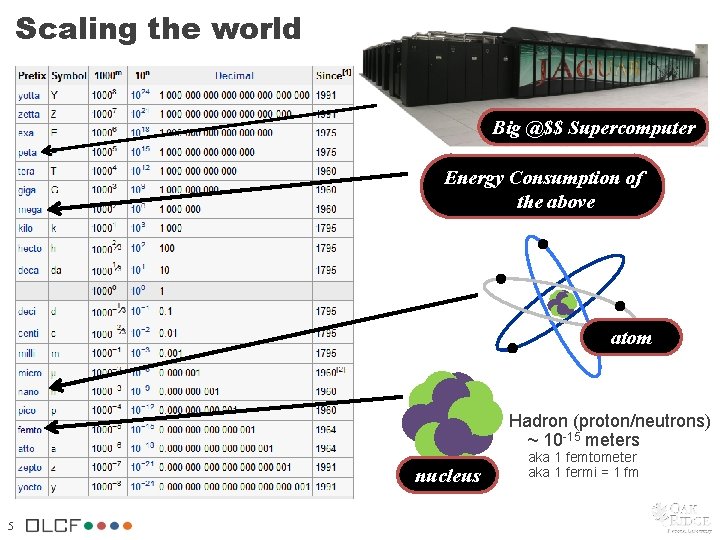

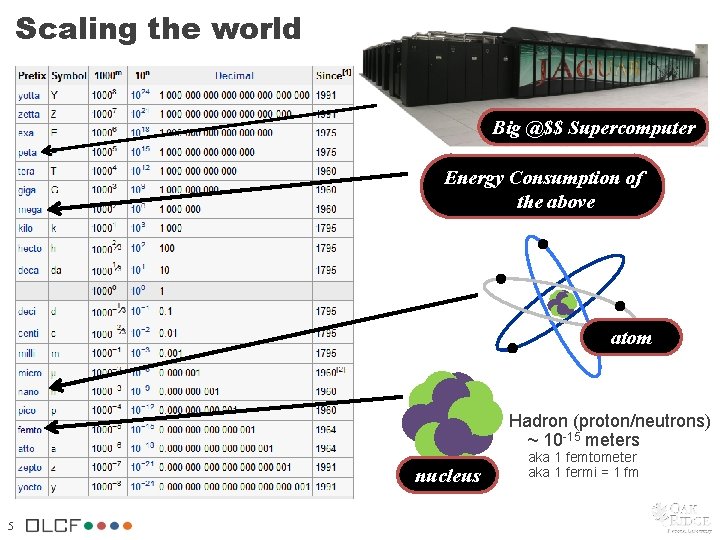

Scaling the world Big @$$ Supercomputer Energy Consumption of the above atom Hadron (proton/neutrons) ~ 10 -15 meters nucleus 5 aka 1 femtometer aka 1 fermi = 1 fm

Matter? You know the periodic table… but nuclear physicists view the elements differently Why are certain combinations of protons and neutrons stable, while others are unstable? In which energy states are protons and neutrons in a stable nucleus? 6

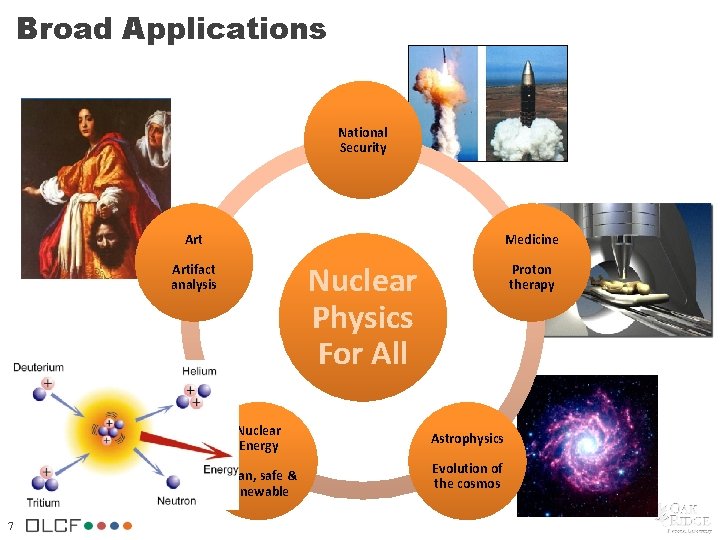

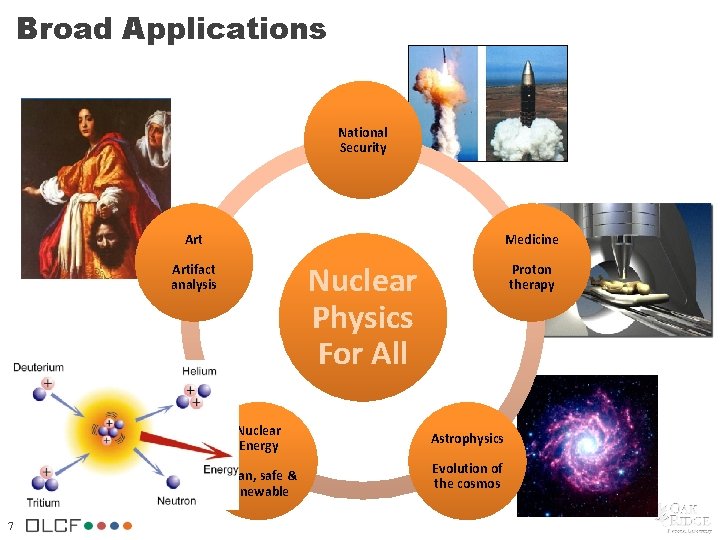

Broad Applications National Security Art Medicine Nuclear Physics For All Artifact analysis Nuclear Energy Clean, safe & renewable 7 Proton therapy Astrophysics Evolution of the cosmos

A whole lot of nuclei to study • Experiment There are nuclei we can’t measure or phenomena we can’t explain. • Theory Light Nuclei NCSM, GFMC, CC Medium Mass CI, CC Heavy Nuclei DFT 8

II. NUCLEAR PHYSICS CODES “Code Talkers, ” xkcd comic: http: //xkcd. com/257/ 9

II. Nuclear Physics Codes • Theoretical and Computational Methods • Representative Codes – NUCCOR – Bigstick 10

Complementary Methods Application AGFMC MFDn NUCCOR DFT Code Suite Description Argonne Green’s Function Monte Carlo Many Fermion Dynamics nuclear Nuclear Coupled. Cluster Oak Ridge Density Functional Theory Current Production Run Sizes 131, 072 cores @ 20 hours (1 trial wave function) Resource 200, 000 cores @ 5 hours (1 model space size) Jaguar 20, 000 cores @ 5 hours (1 nucleus) Jaguar 100, 000 cores @ 10 hours (entire mass table) Jaguar Intrepid • Validation & Verification – Enhance realistic predictive capability by comparing methods in overlap areas • Input from ab initio methods can be used to optimize/direct nuclear DFT • Strengths and weaknesses 11

The Need for HPC INCITE Utilization CPU-Hours (Millions) 120 100 80 60 40 148 700+ 20 0 2008 Jaguar Allocation 12 488 2009 Early Science (OLCF) Jaguar Usage Jan-Aug 2010 2011 Intrepid Allocation 2012 2013 Intrepid Usage Early Science Request (ALCF)

NUCCOR • Nuclear Coupled-Cluster Oak Ridge • Developed by David Dean et al. • Solves nuclear many-body problem using coupled-cluster approximation – Single and double excitations computed, plus thirdorder correction – Solves system of nonlinear equations with Broyden’s Method • Polynomial scaling with number of particles and single-particle states • 16, 000 lines of Fortran 90 • Parallelization with MPI; exclusively collective 13

Bigstick • Developed by Calvin Johnson at San Diego State University and Erich Ormand at Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory • Configuration Interaction (shell model) • Performs on-the-fly recalculation of Hamiltonian (smaller memory footprint than typical CI codes) • Lanczos diagonalization to solve for eigenvalues and eigenvectors representing ground and excited states of system • Written in Fortran 14

III. PERFORMANCE PROFILING http: //www. bmwblog. com/wp-content/uploads/bmw-135 i-performance-package-atalbert-park-australia. jpg 15

III. Performance Profiling • Cray. PAT – About Cray. PAT – Profiling NUCCOR • Vampir. Trace and Vampir – About Vampir. Trace/Vampir – Profiling Bigstick 16

Cray. PAT • Package for instrumenting and tracing codes on Cray systems • Run instrumented code to obtain overview of code behavior • Re-run with refined profiling, to trace most important subroutines • Analyzed NUCCOR with Cray. PAT 17

Cray. PAT: j-Coupled NUCCOR • We first profiled j-coupled version of NUCCOR with Cray. Pat • Discovered it spent >50% of its time sorting in test benchmark – Found it was using highly inefficient bubble-sort-like algorithm – Replaced “Frankenstein sort” with heapsort, reduced sorting to ~3% of time • Asked collaborators what they were sorting, and why? – Their response: “We’re sorting something? ” • Removed sorting altogether, code worked just 18

Cray. PAT: NUCCOR • We next profiled standard version • Discovered it spent nearly 70% of time in single subroutine: t 2_eqn_store_p_or_n • This subroutine became focus of subsequent work with NUCCOR 19

Vampir. Trace/Vampir • Vampir. Trace: instrument code to produce trace files – Compile with VT wrapper, run code and obtain trace output files • Vampir: use to visualize trace – Run in interactive job of nearly same size as job that produced trace files – Server on interactive job serves as analysis engine to local front-end • Analyzed Bigstick with Vampir. Trace and Vampir 20

Top-Level Overview 21

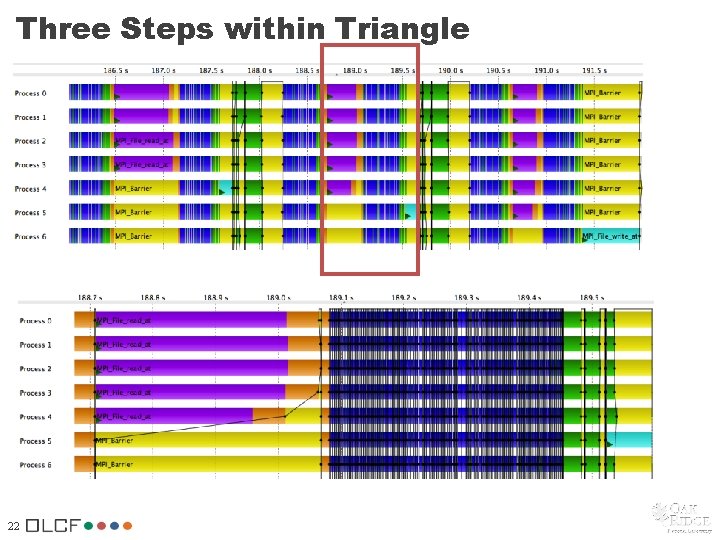

Three Steps within Triangle 22

Block Reduce Phase 23

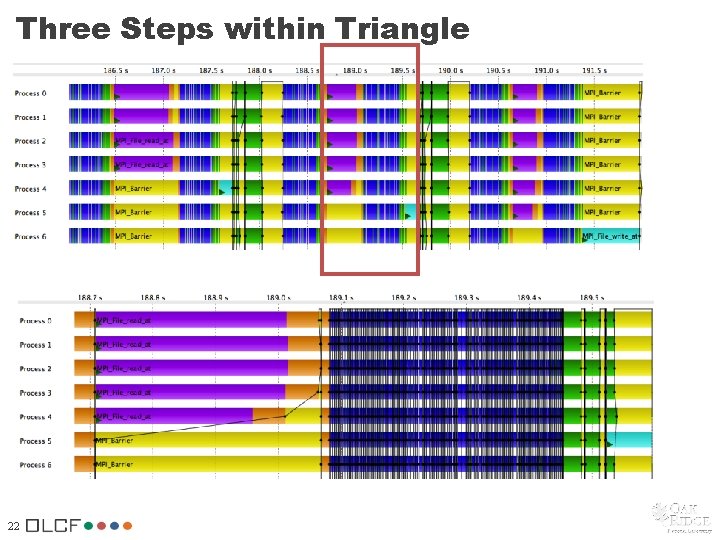

Bigstick: Analysis • Triangular pattern in overview reminiscent of sequential algorithm applied across processors – Digging deeper shows in orthogonalization phase, processors held up by single processor writing to Lanczos vector file – Suggestion: reduce amount of orthogonalization performed • Disproportionate time spent in MPI_Barrier (~30%) – Indicative of load imbalance – Barriers are within clocker subroutine, used for performance timings, obscuring evidence of load imbalance • Majority of time in block reduce phase spent in 24

Source: http: //img. domaintools. com/blog/dt-improved-performance. jpg IV. COMPILER OPTIMIZATION 25

IV. Compiler Optimization • Motivation • Experiments • Results 26

Motivation • Observed anomalous behavior in NUCCOR using Intel compiler on Jaguar • Turned out to be compiler bug • Nuclear Physics community relies heavily on Intel compiler • Question: How will NUCCOR perform when compiled with each of five available compilers on Jaguar? 27

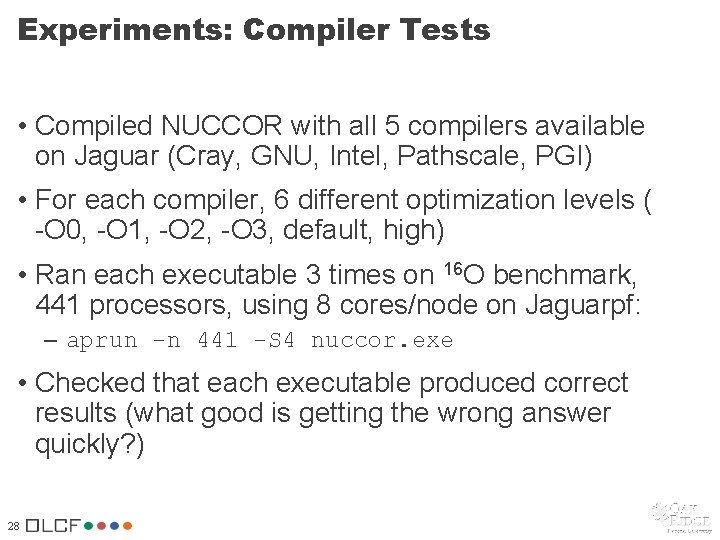

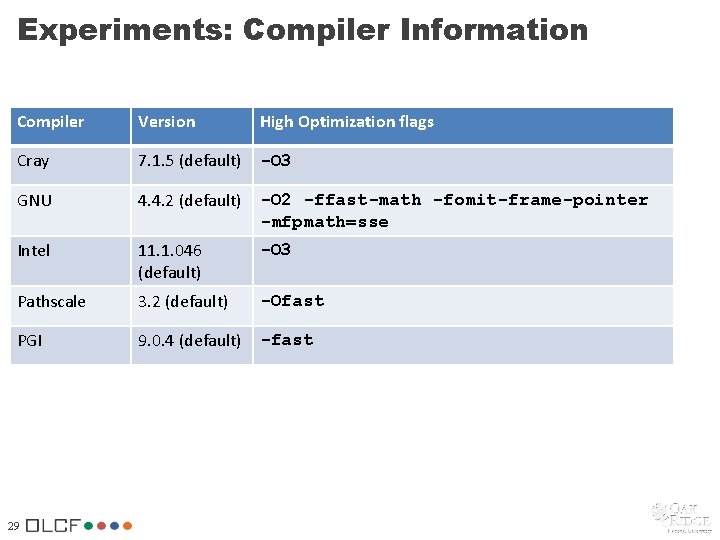

Experiments: Compiler Tests • Compiled NUCCOR with all 5 compilers available on Jaguar (Cray, GNU, Intel, Pathscale, PGI) • For each compiler, 6 different optimization levels ( -O 0, -O 1, -O 2, -O 3, default, high) • Ran each executable 3 times on 16 O benchmark, 441 processors, using 8 cores/node on Jaguarpf: – aprun -n 441 -S 4 nuccor. exe • Checked that each executable produced correct results (what good is getting the wrong answer quickly? ) 28

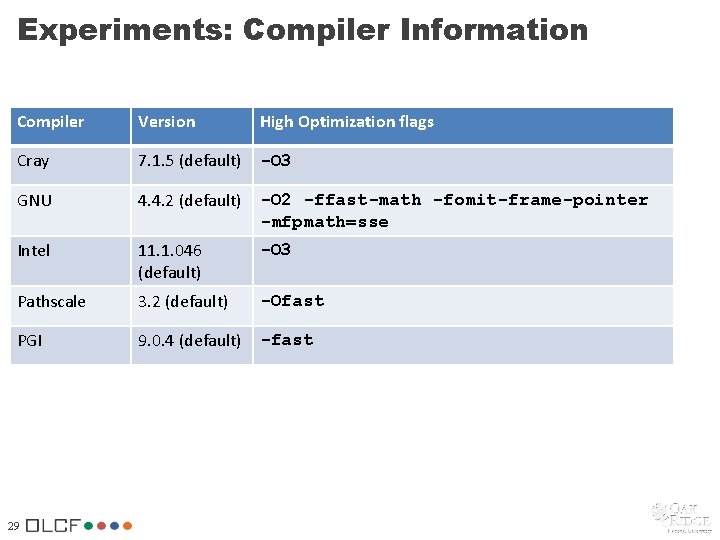

Experiments: Compiler Information Compiler Version High Optimization flags Cray 7. 1. 5 (default) -O 3 GNU 4. 4. 2 (default) -O 2 -ffast-math -fomit-frame-pointer -mfpmath=sse Intel 11. 1. 046 (default) -O 3 Pathscale 3. 2 (default) -Ofast PGI 9. 0. 4 (default) -fast 29

Results: -O 0 Optimization Level 4500 4000 Time (seconds) 3500 3000 2500 2000 1500 1000 500 0 Cray GNU Intel Compiler Elapsed Time 30 Iter Time Pathscale PGI

Results: -O 1 Optimization Level 4000 Time (seconds) 3500 3000 2500 2000 1500 1000 500 0 Cray GNU Intel Compiler Elapsed Time 31 Iter Time Pathscale PGI

Results: -O 2 Optimization Level 3500 Time (seconds) 3000 2500 2000 1500 1000 500 0 Cray GNU Intel Compiler Elapsed Time 32 Iter Time Pathscale PGI

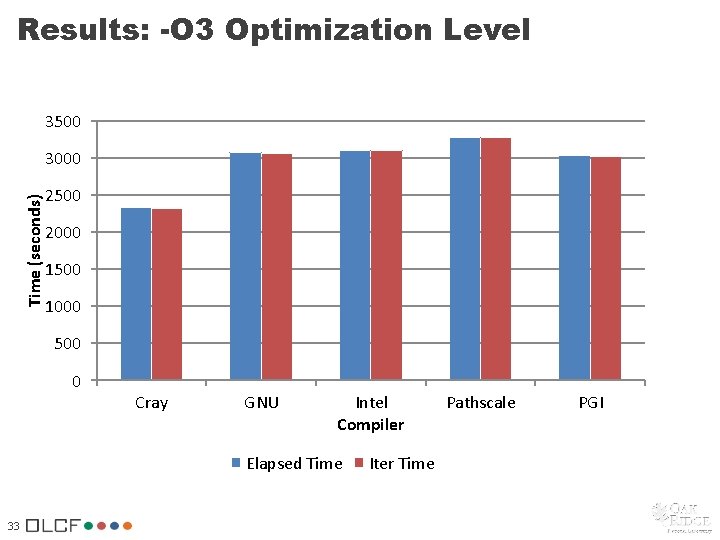

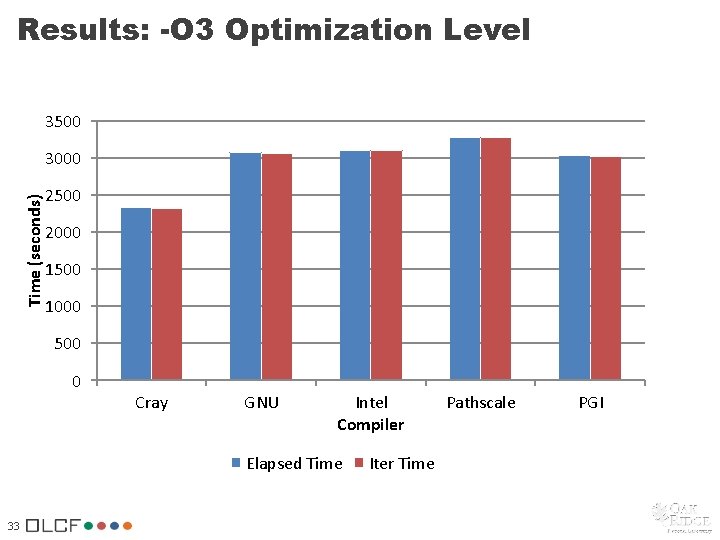

Results: -O 3 Optimization Level 3500 Time (seconds) 3000 2500 2000 1500 1000 500 0 Cray GNU Intel Compiler Elapsed Time 33 Iter Time Pathscale PGI

Results: Default Optimization Level 4500 4000 Time (seconds) 3500 3000 2500 2000 1500 1000 500 0 Cray GNU Intel Compiler Elapsed Time 34 Iter Time Pathscale PGI

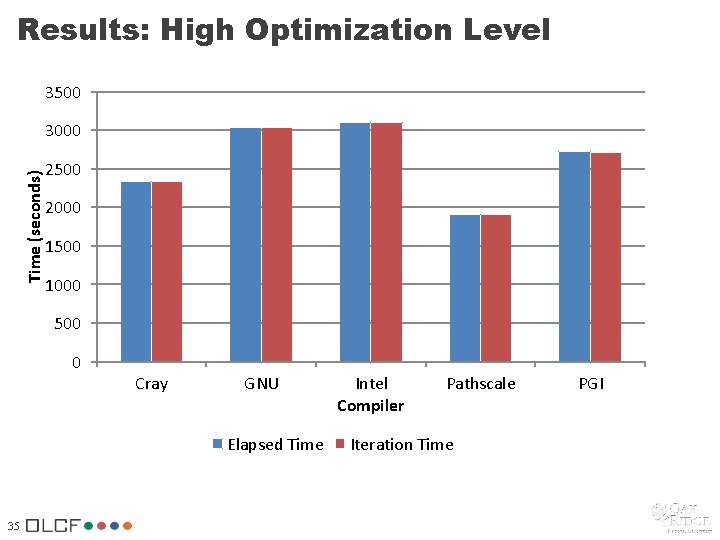

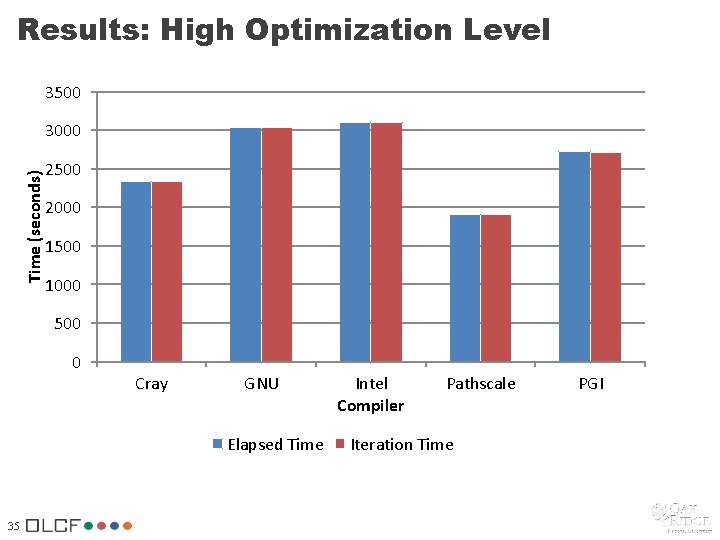

Results: High Optimization Level 3500 Time (seconds) 3000 2500 2000 1500 1000 500 0 Cray GNU Elapsed Time 35 Intel Compiler Pathscale Iteration Time PGI

Results: Aggregate Performance Results Compiler Performance by Optimization Level Elapsed Time (seconds) 5000 4000 3000 2000 1000 0 Cray O 0 36 GNU O 1 Intel Pathscal e O 2 O 3 PGI Default O 3 Default High O 2 O 1 O 0

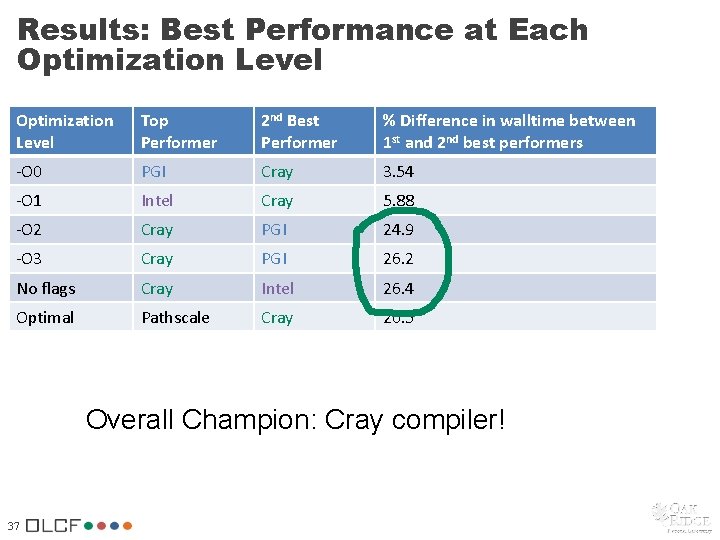

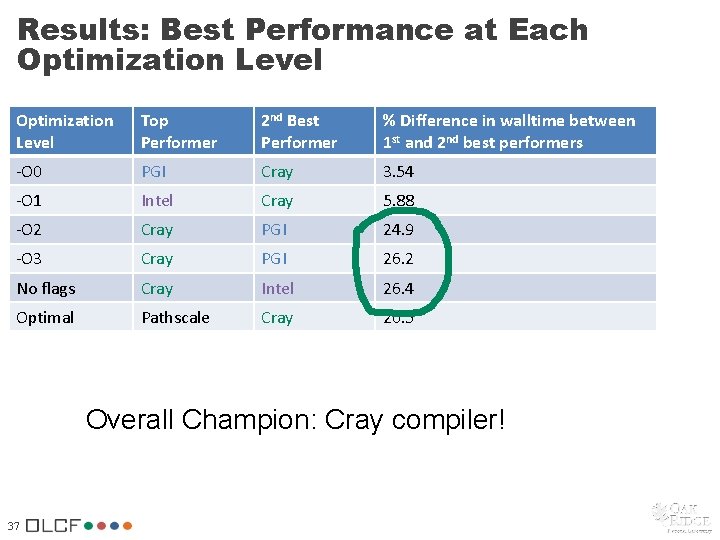

Results: Best Performance at Each Optimization Level Top Performer 2 nd Best Performer % Difference in walltime between 1 st and 2 nd best performers -O 0 PGI Cray 3. 54 -O 1 Intel Cray 5. 88 -O 2 Cray PGI 24. 9 -O 3 Cray PGI 26. 2 No flags Cray Intel 26. 4 Optimal Pathscale Cray 20. 5 Overall Champion: Cray compiler! 37

V. COMPILER FEEDBACK & HAND TUNING Tuning forks, http: //www. phys. cwru. edu/ccpi/Tuning_fork. html 38

V. Compiler Feedback & Hand Tuning • Motivation • Loop Optimization in NUCCOR • Compiler Feedback • Loop Reordering – Experiments – Results 39

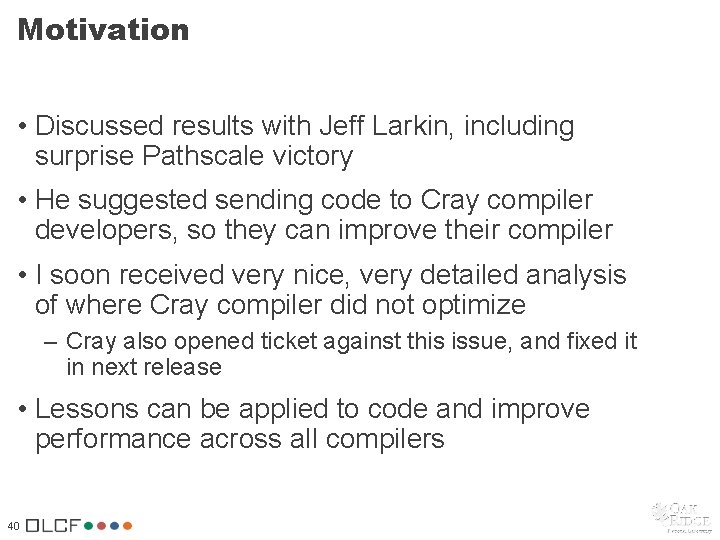

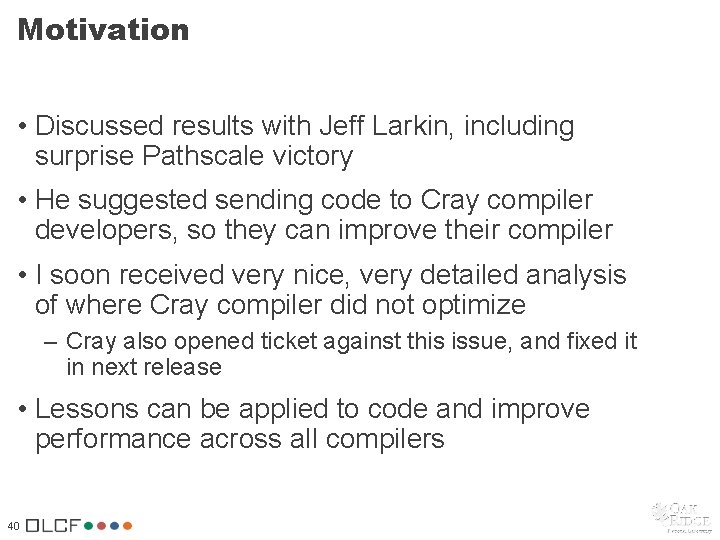

Motivation • Discussed results with Jeff Larkin, including surprise Pathscale victory • He suggested sending code to Cray compiler developers, so they can improve their compiler • I soon received very nice, very detailed analysis of where Cray compiler did not optimize – Cray also opened ticket against this issue, and fixed it in next release • Lessons can be applied to code and improve performance across all compilers 40

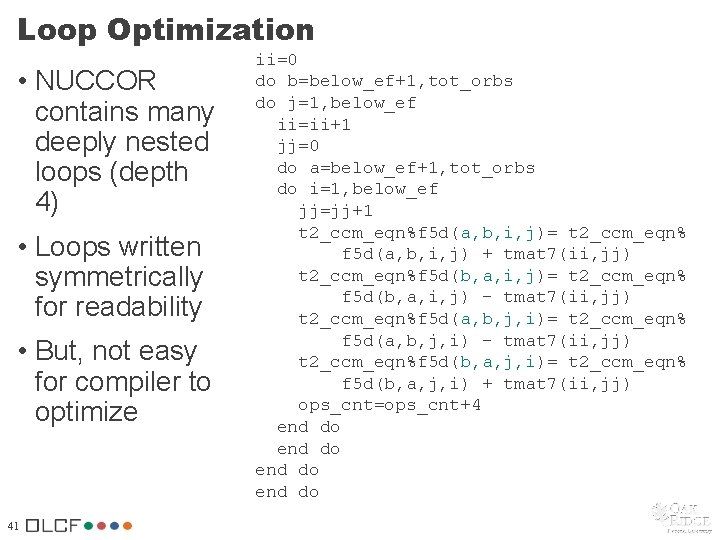

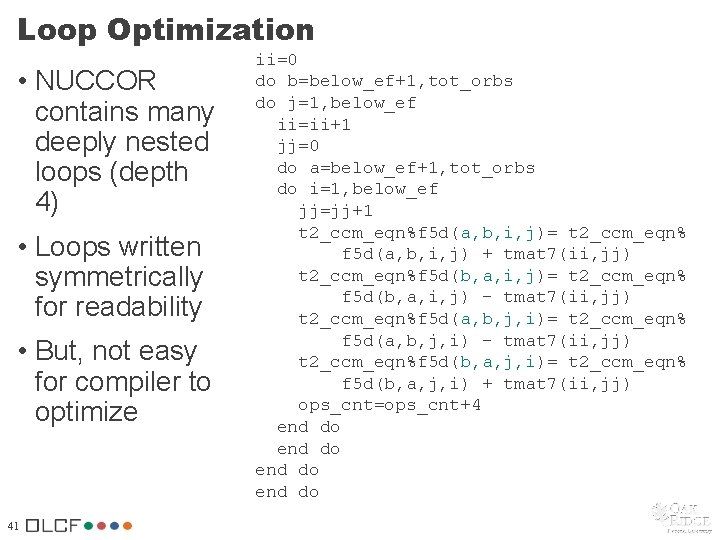

Loop Optimization • NUCCOR contains many deeply nested loops (depth 4) • Loops written symmetrically for readability • But, not easy for compiler to optimize 41 ii=0 do b=below_ef+1, tot_orbs do j=1, below_ef ii=ii+1 jj=0 do a=below_ef+1, tot_orbs do i=1, below_ef jj=jj+1 t 2_ccm_eqn%f 5 d(a, b, i, j)= t 2_ccm_eqn% f 5 d(a, b, i, j) + tmat 7(ii, jj) t 2_ccm_eqn%f 5 d(b, a, i, j)= t 2_ccm_eqn% f 5 d(b, a, i, j) - tmat 7(ii, jj) t 2_ccm_eqn%f 5 d(a, b, j, i)= t 2_ccm_eqn% f 5 d(a, b, j, i) - tmat 7(ii, jj) t 2_ccm_eqn%f 5 d(b, a, j, i)= t 2_ccm_eqn% f 5 d(b, a, j, i) + tmat 7(ii, jj) ops_cnt=ops_cnt+4 end do

Problems in Loop • Loop is easy for humans to read • But, strides through memory cause cache thrashing and increased bandwidth use • With below_ef = 16 and tot_orbs = 336, each cache line of t 2_ccm_eqn%f 5 d will have to be reloaded 8 times • Also, array tmat 7(ii, jj) referenced through 2 nd subscript, so poor stride • All compilers on Jaguar (except maybe Pathscale with -Ofast) fail to interchange loop nesting 42

Loop Memory Access (Poor Stride) 43

Loop Memory Access (Good Stride) 44

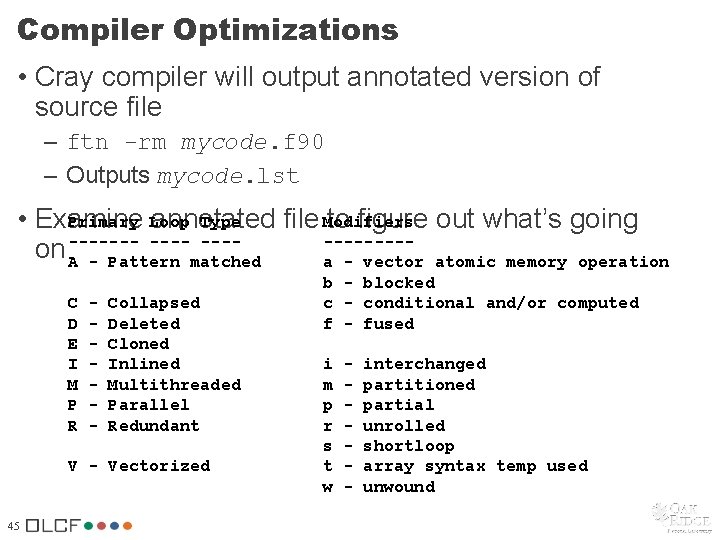

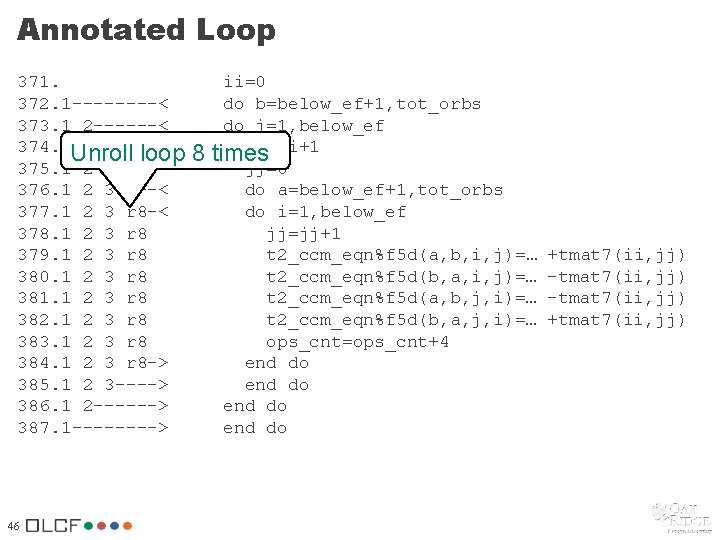

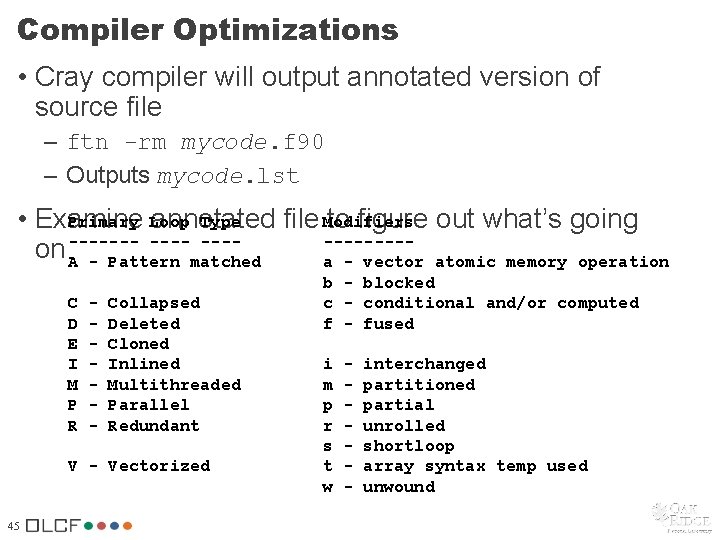

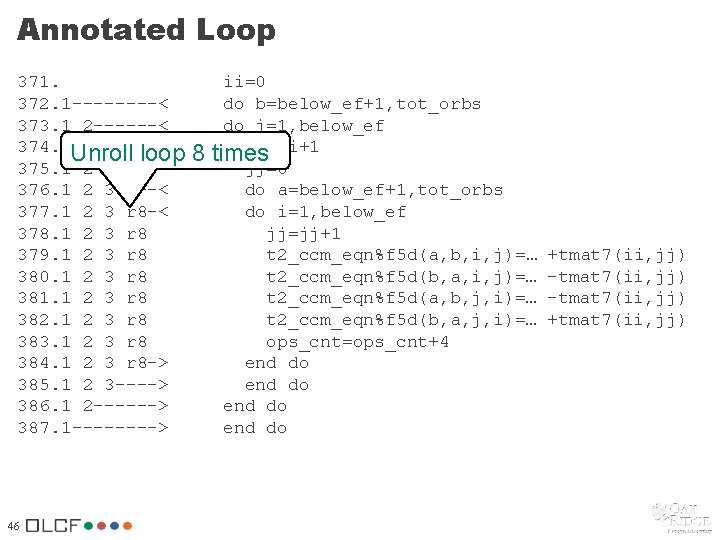

Compiler Optimizations • Cray compiler will output annotated version of source file – ftn -rm mycode. f 90 – Outputs mycode. lst Primary Loop Type • Examine annotated file Modifiers to figure out what’s going -----------on ------A - Pattern matched a - vector atomic memory operation C D E I M P R - Collapsed Deleted Cloned Inlined Multithreaded Parallel Redundant V - Vectorized 45 b - blocked c - conditional and/or computed f - fused i m p r s t w - interchanged partitioned partial unrolled shortloop array syntax temp used unwound

Annotated Loop 371. 372. 1 ----< 373. 1 2 ------< 374. 1 Unroll 2 loop 375. 1 2 376. 1 2 3 ----< 377. 1 2 3 r 8 -< 378. 1 2 3 r 8 379. 1 2 3 r 8 380. 1 2 3 r 8 381. 1 2 3 r 8 382. 1 2 3 r 8 383. 1 2 3 r 8 384. 1 2 3 r 8 -> 385. 1 2 3 ----> 386. 1 2 ------> 387. 1 ----> 46 8 ii=0 do b=below_ef+1, tot_orbs do j=1, below_ef ii=ii+1 times jj=0 do a=below_ef+1, tot_orbs do i=1, below_ef jj=jj+1 t 2_ccm_eqn%f 5 d(a, b, i, j)=… t 2_ccm_eqn%f 5 d(b, a, i, j)=… t 2_ccm_eqn%f 5 d(a, b, j, i)=… t 2_ccm_eqn%f 5 d(b, a, j, i)=… ops_cnt=ops_cnt+4 end do +tmat 7(ii, jj) -tmat 7(ii, jj) +tmat 7(ii, jj)

Loop Reordering: Two Things to Try • Improve stride: reorder so that tmat 7 is accessed by consecutive row, not column • Loop fission: put all f 5 d(a, b, : ) in one loop, all f 5 d(b, a, : ) in another • Test these two ideas in simple loop unrolling code 47

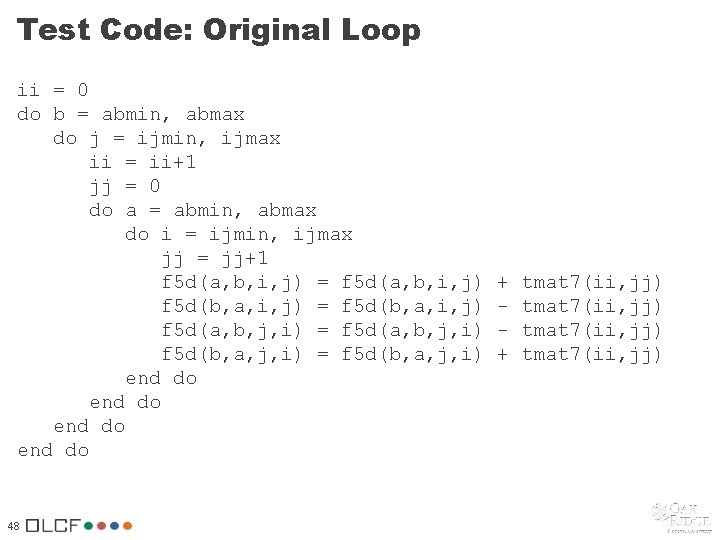

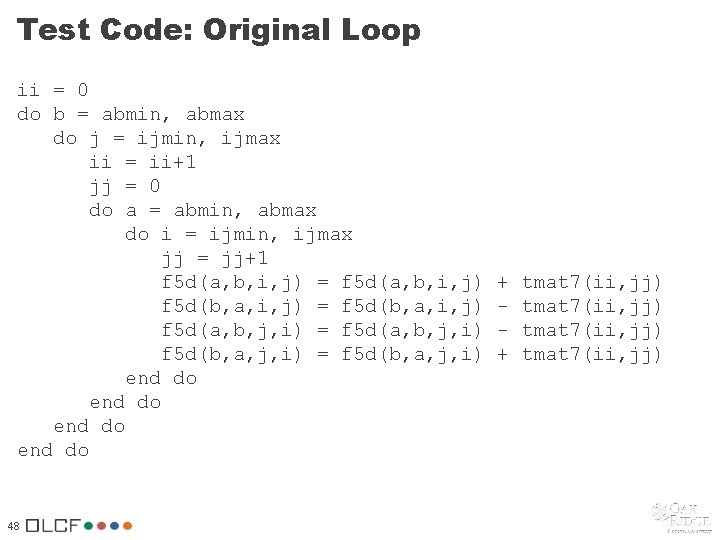

Test Code: Original Loop ii = 0 do b = abmin, abmax do j = ijmin, ijmax ii = ii+1 jj = 0 do a = abmin, abmax do i = ijmin, ijmax jj = jj+1 f 5 d(a, b, i, j) = f 5 d(a, b, i, j) f 5 d(b, a, i, j) = f 5 d(b, a, i, j) f 5 d(a, b, j, i) = f 5 d(a, b, j, i) f 5 d(b, a, j, i) = f 5 d(b, a, j, i) end do 48 + + tmat 7(ii, jj)

Test Code: Improved Stride do i = ijmin, ijmax jj = 0 do a = abmin, abmax do j=ijmin, ijmax jj = jj+1 ii = 0 do b = abmin, abmax ii = ii+1 f 5 d(a, b, i, j) = f 5 d(a, b, i, j) f 5 d(b, a, i, j) = f 5 d(b, a, i, j) f 5 d(a, b, j, i) = f 5 d(a, b, j, i) f 5 d(b, a, j, i) = f 5 d(b, a, j, i) end do 49 + + tmat 7(ii, jj)

Test Code: Loop Fission ii = 0 jj = 0 do j = ijmin, ijmax do i = ijmin, ijmax do b = abmin, abmax do a = abmin, abmax ii = ii+1 jj = jj+1 jj = 0 ii = 0 do i = ijmin, ijmax do j = ijmin, ijmax do a = abmin, abmax do b = abmin, abmax jj = jj+1 ii = ii+1 f 5 d(a, b, i, j) = f 5 d(b, a, i, j) = f 5 d(a, b, i, j) + f 5 d(b, a, i, j) tmat 7(ii, jj) f 5 d(a, b, j, i) = f 5 d(b, a, j, i) = f 5 d(a, b, j, i) f 5 d(b, a, i, j) + tmat 7(ii, jj) end do end do 50

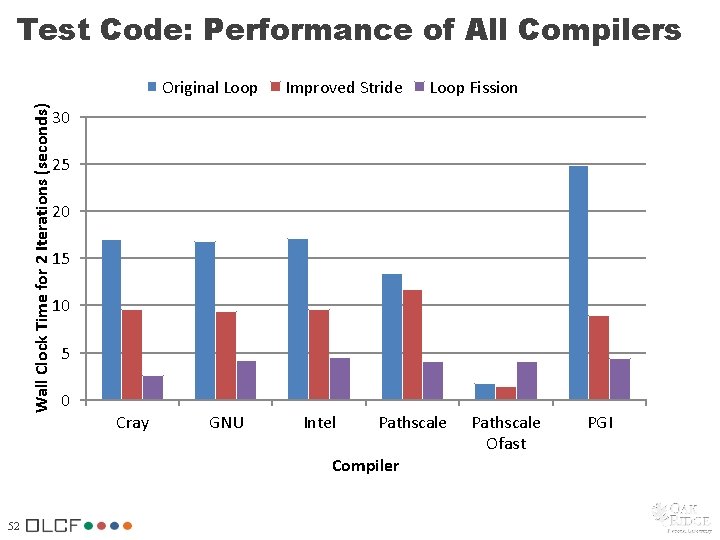

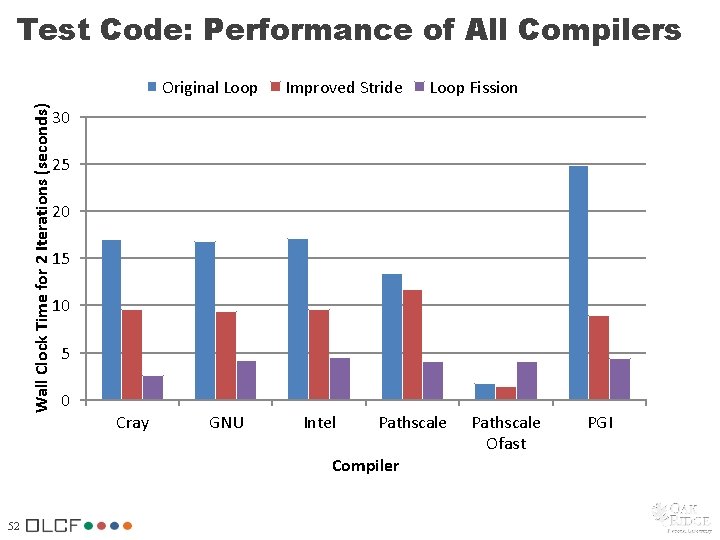

Test Code: Cray Compiler Behavior • Original Loop: unrolled 8 times • Improved Stride: conditionally vectorized, unrolled 2 times • Loop Fission: 1 st loop vectorized, partially unrolled 4 times; 2 nd loop vectorized, unrolled 4 times 51

Test Code: Performance of All Compilers Wall Clock Time for 2 Iterations (seconds) Original Loop Improved Stride 30 25 20 15 10 5 0 Cray GNU Intel Pathscale Compiler 52 Loop Fission Pathscale Ofast PGI

VI. CONCLUSIONS & FUTURE WORK Cartoon from Toothpaste for Dinner: http: //www. toothpastefordinner. com/052804/see-into-the-future. gif 53

VI. Conclusions & Future Work • Much potential for optimization in nuclear physics codes • To remain competitive, nuclear physicists must continue to evolve codes to run efficiently on HPC resources – Relatively simple changes can drastically improve performance – In-depth measures must be taken for further performance gains, especially as we move to hybrid systems – Need to get away from manager-worker, centralized paradigms • In process of implementing insights from this 54

Questions What does a nuclear physicist eat for lunch? Fission Chips! 55

Resources • Hai Ah Nam (2010) Femtoscale on Petascale: Nuclear Physics in HPC, LCF Seminar Series, ORNL. • Rebecca Hartman-Baker (2010) Try Anything Once: A Case Study Using NUCCOR, OLCF Hexcore Workshop, http: //www. nccs. gov/wpcontent/uploads/2010/02/try_anything 2. pdf. • OLCF software: – Craypat: http: //www. olcf. ornl. gov/kb_articles/software-jaguar -craypat/ – Vampir: http: //www. nccs. gov/computingresources/jaguar/software/? software=vampir – Vampir. Trace: http: //www. nccs. gov/computingresources/jaguar/software/? software=vampirtrace 56

Resources • UNEDF Nuclear Physics collaboration: http: //www. unedf. org • G. F. Bertsch, D. J. Dean and W. Nazarewich, Sci. DAC Rev. 6, 42 (2007) • D. J. Dean, G. Hagen, M. Hjorth-Jensen, and T. Papenbrock, “Computational aspects of nuclear coupled-cluster theory, ” Comput. Sci. Disc. 1, 015008 (2008) • Nuclear Science Advisory Committee, “The Frontiers of Nuclear Science: A Long Range Plan, ” http: //www. sc. doe. gov/np/nsac/docs/Nuclear. Science. Low-Res. pdf 57

Acknowledgments • A very big thank-you to – David Pigg (Vanderbilt) – Jeff Larkin, Nathan Wichmann, Vince Graziano (Cray) • This work was supported by the US Department of Energy under contract numbers DE-AC 0500 OR 22725 (Oak Ridge National Laboratory, managed by UT-Battelle, LLC). • This research used resources of the National Center for Computational Sciences at Oak Ridge National Laboratory, which is supported by the Office of Science of the U. S. Department of Energy under Contract No. DE- AC 0500 OR 22725. 58