Optimization through Redundancy Elimination Value Numbering at Different

Optimization through Redundancy Elimination: Value Numbering at Different Scopes COMP 512 Rice University Houston, Texas Fall 2003 Copyright 2003, Keith D. Cooper & Linda Torczon, all rights reserved. Students enrolled in Comp 512 at Rice University have explicit permission to make copies of these materials for their personal use. COMP 512, Fall 2003 1

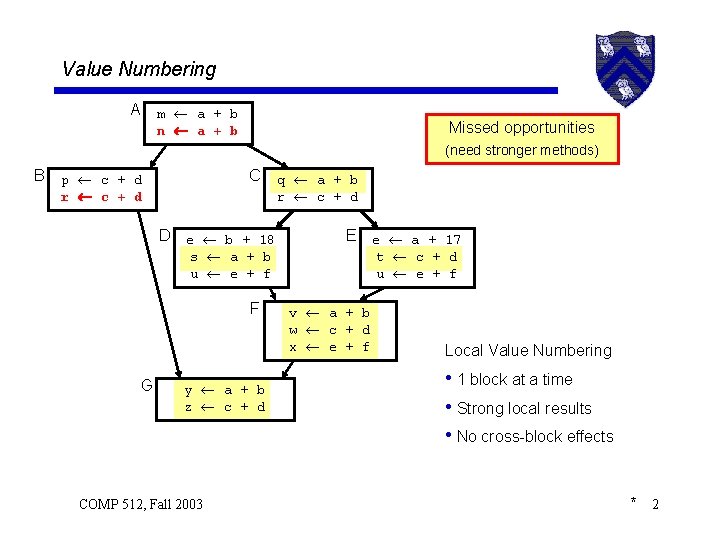

Value Numbering A m a + b n a + b Missed opportunities (need stronger methods) B C p c + d r c + d D e b + 18 s a + b u e + f F G y a + b z c + d COMP 512, Fall 2003 q a + b r c + d E e a + 17 t c + d u e + f v a + b w c + d x e + f Local Value Numbering • 1 block at a time • Strong local results • No cross-block effects * 2

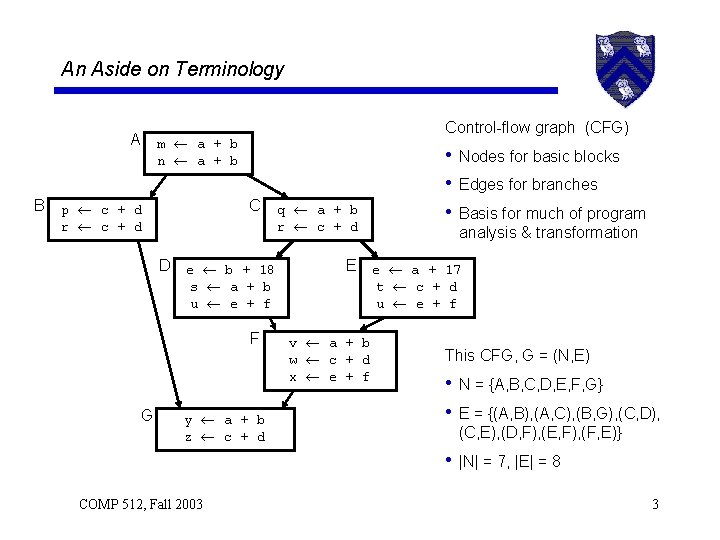

An Aside on Terminology A B Control-flow graph (CFG) m a + b n a + b C p c + d r c + d D e b + 18 s a + b u e + f F G y a + b z c + d q a + b r c + d • Nodes for basic blocks • Edges for branches • Basis for much of program analysis & transformation E e a + 17 t c + d u e + f v a + b w c + d x e + f This CFG, G = (N, E) • N = {A, B, C, D, E, F, G} • E = {(A, B), (A, C), (B, G), (C, D), (C, E), (D, F), (E, F), (F, E)} • |N| = 7, |E| = 8 COMP 512, Fall 2003 3

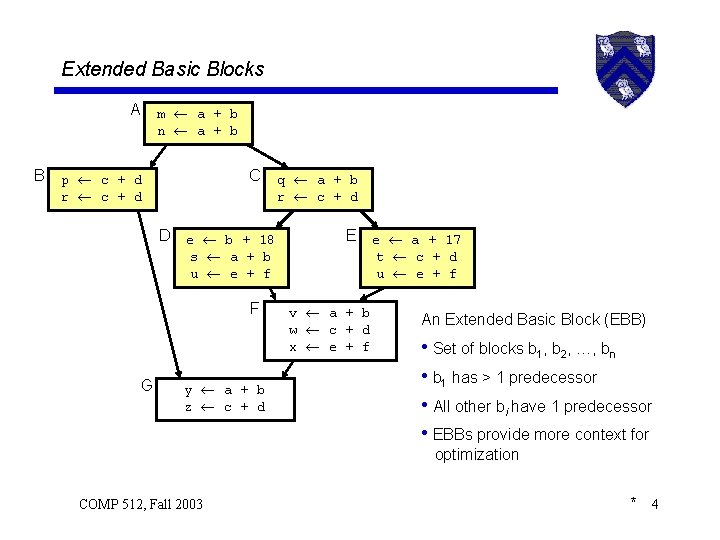

Extended Basic Blocks A B m a + b n a + b C p c + d r c + d D e b + 18 s a + b u e + f F G y a + b z c + d q a + b r c + d E e a + 17 t c + d u e + f v a + b w c + d x e + f An Extended Basic Block (EBB) • Set of blocks b 1, b 2, …, bn • b 1 has > 1 predecessor • All other bi have 1 predecessor • EBBs provide more context for optimization COMP 512, Fall 2003 * 4

Extended Basic Blocks A B m a + b n a + b An EBB contains 1 or more path C p c + d r c + d D e b + 18 s a + b u e + f F G y a + b z c + d If b 1, b 2, …, bn is a path q a + b r c + d • b 1 has > 1 predecessor • bi has 1 predecessor, bi-1 E e a + 17 t c + d u e + f v a + b w c + d x e + f {A, B, C, D, E} is an EBB • {A, B}, {A, C, D}, and {A, C, E} are paths in {A, B, C, D, E} {F} and {G} are also EBBs • They have only trivial paths COMP 512, Fall 2003 * 5

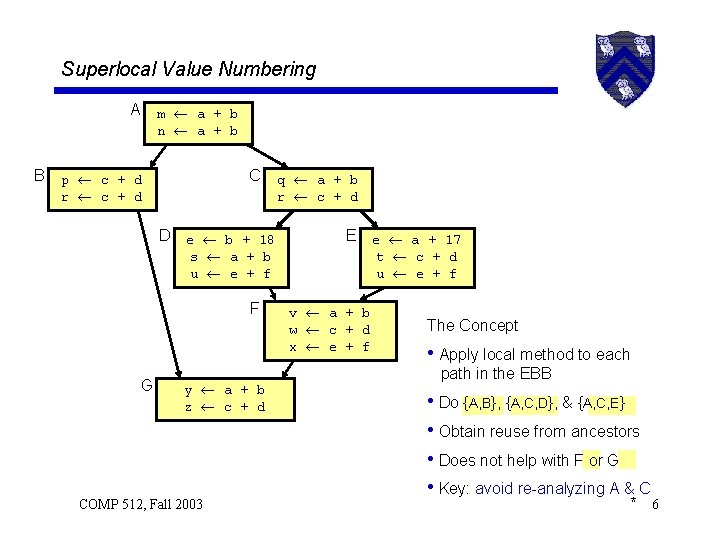

Superlocal Value Numbering A B m a + b n a + b C p c + d r c + d D e b + 18 s a + b u e + f F G y a + b z c + d COMP 512, Fall 2003 q a + b r c + d E e a + 17 t c + d u e + f v a + b w c + d x e + f The Concept • Apply local method to each path in the EBB • Do {A, B}, {A, C, D}, & {A, C, E} • Obtain reuse from ancestors • Does not help with F or G • Key: avoid re-analyzing A & C * 6

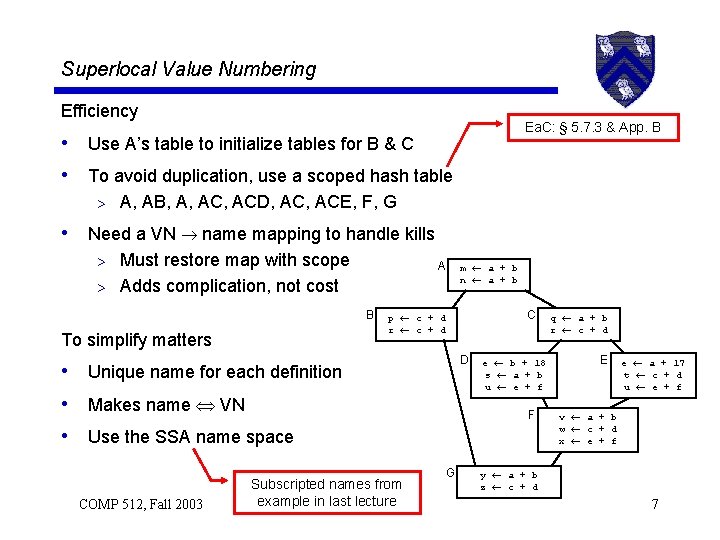

Superlocal Value Numbering Efficiency Ea. C: § 5. 7. 3 & App. B • Use A’s table to initialize tables for B & C • To avoid duplication, use a scoped hash table > A, AB, A, ACD, ACE, F, G • Need a VN name mapping to handle kills Must restore map with scope > Adds complication, not cost > A B To simplify matters m a + b n a + b C p c + d r c + d D • Unique name for each definition • Makes name VN • Use the SSA name space COMP 512, Fall 2003 Subscripted names from example in last lecture e b + 18 s a + b u e + f F G q a + b r c + d E e a + 17 t c + d u e + f v a + b w c + d x e + f y a + b z c + d 7

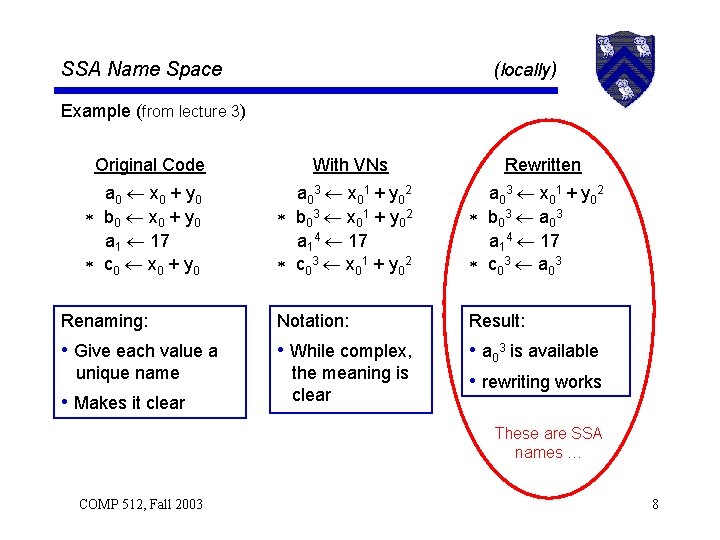

SSA Name Space (locally) Example (from lecture 3) Original Code a 0 x 0 + y 0 b 0 x 0 + y 0 a 1 17 c 0 x 0 + y 0 With VNs Rewritten a 0 3 x 0 1 + y 0 2 b 0 3 x 0 1 + y 0 2 a 14 17 c 0 3 x 0 1 + y 0 2 a 0 3 x 0 1 + y 0 2 b 0 3 a 0 3 a 14 17 c 0 3 a 0 3 Renaming: Notation: Result: • Give each value a • While complex, • a 03 is available • rewriting works unique name • Makes it clear the meaning is clear These are SSA names … COMP 512, Fall 2003 8

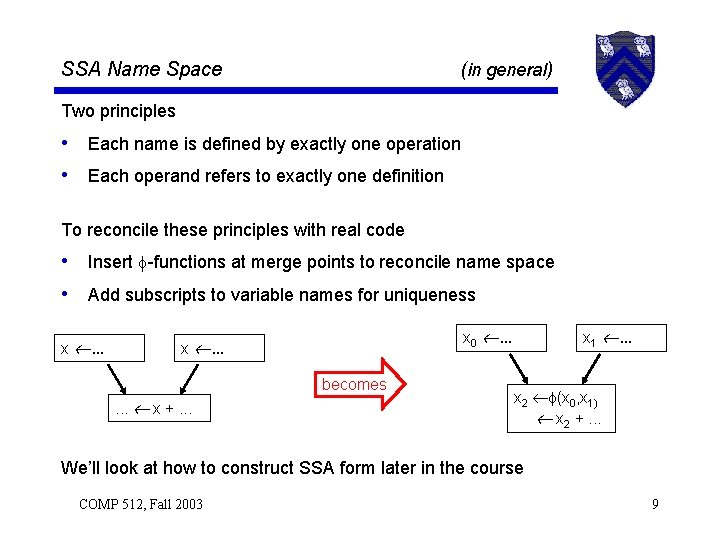

SSA Name Space (in general) Two principles • Each name is defined by exactly one operation • Each operand refers to exactly one definition To reconcile these principles with real code • Insert -functions at merge points to reconcile name space • Add subscripts to variable names for uniqueness x . . . x 0 . . . x . . . becomes. . . x +. . . x 1 . . . x 2 (x 0, x 1) x 2 +. . . We’ll look at how to construct SSA form later in the course COMP 512, Fall 2003 9

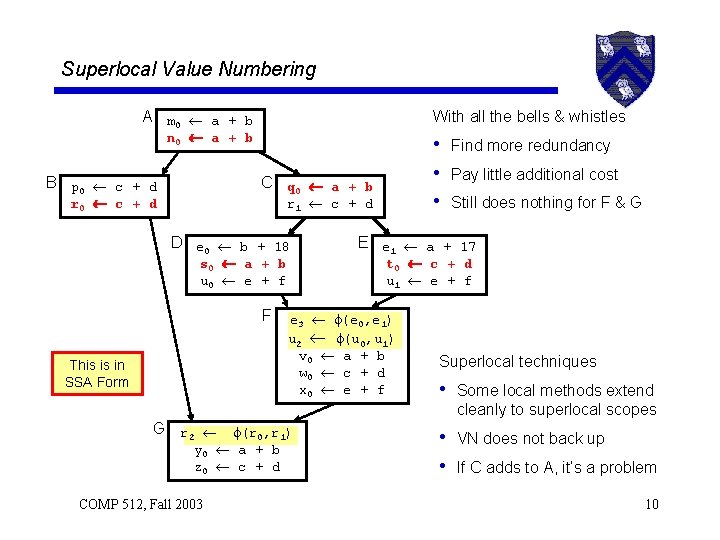

Superlocal Value Numbering With all the bells & whistles A m 0 a + b n 0 a + b B p 0 c + d • Find more redundancy • Pay little additional cost • Still does nothing for F & G C q 0 a + b r 0 c + d r 1 c + d D e 0 b + 18 s 0 a + b u 0 e + f F This is in SSA Form E e 1 a + 17 t 0 c + d u 1 e + f e 3 (e 0, e 1) u 2 (u 0, u 1) v 0 a + b w 0 c + d x 0 e + f Superlocal techniques • Some local methods extend cleanly to superlocal scopes G r 2 (r 0, r 1) y 0 a + b z 0 c + d COMP 512, Fall 2003 • VN does not back up • If C adds to A, it’s a problem 10

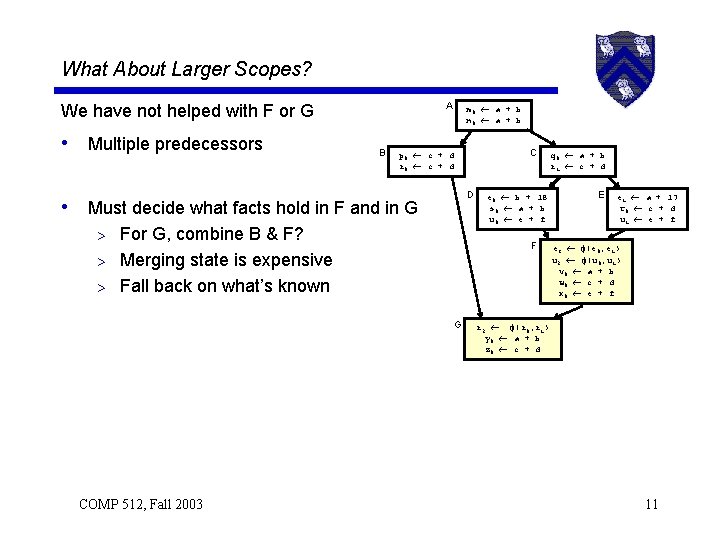

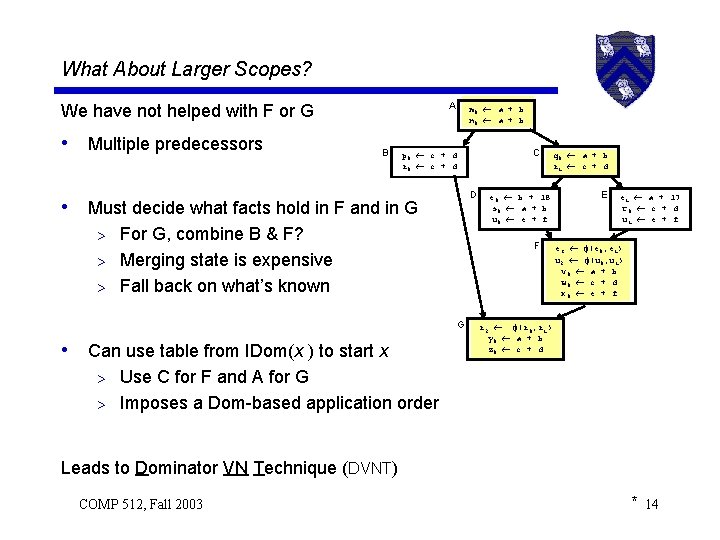

What About Larger Scopes? A We have not helped with F or G • Multiple predecessors B m 0 a + b n 0 a + b D • Must decide what facts hold in F and in G For G, combine B & F? > Merging state is expensive > Fall back on what’s known > e 0 b + 18 s 0 a + b u 0 e + f F G COMP 512, Fall 2003 C p 0 c + d r 0 c + d q 0 a + b r 1 c + d E e 1 a + 17 t 0 c + d u 1 e + f e 3 (e 0, e 1) u 2 (u 0, u 1) v 0 a + b w 0 c + d x 0 e + f r 2 (r 0, r 1) y 0 a + b z 0 c + d 11

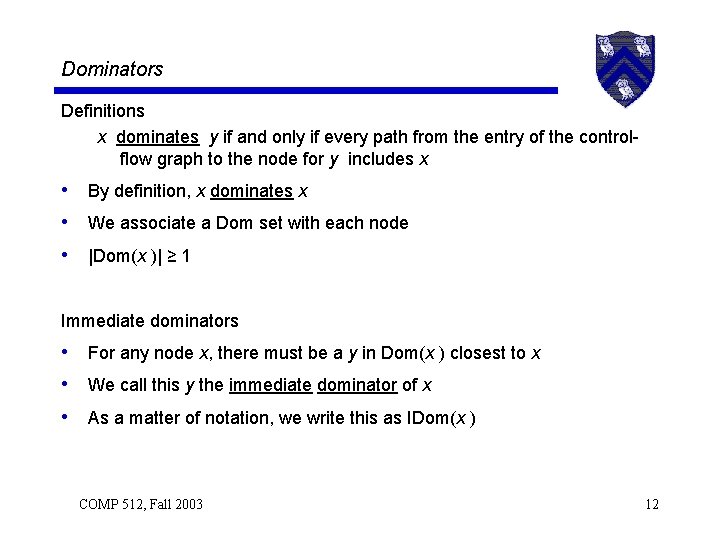

Dominators Definitions x dominates y if and only if every path from the entry of the controlflow graph to the node for y includes x • By definition, x dominates x • We associate a Dom set with each node • |Dom(x )| ≥ 1 Immediate dominators • For any node x, there must be a y in Dom(x ) closest to x • We call this y the immediate dominator of x • As a matter of notation, we write this as IDom(x ) COMP 512, Fall 2003 12

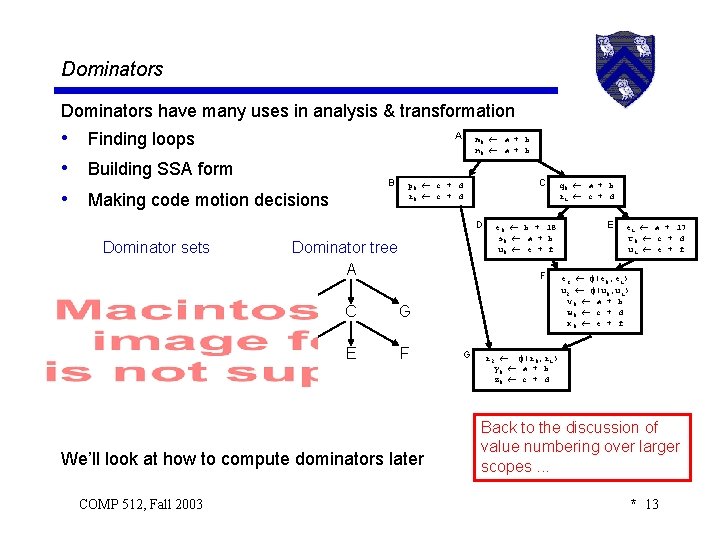

Dominators have many uses in analysis & transformation • Finding loops • Building SSA form • Making code motion decisions A B m 0 a + b n 0 a + b C p 0 c + d r 0 c + d D Dominator sets Dominator tree A F B C G D E F We’ll look at how to compute dominators later COMP 512, Fall 2003 e 0 b + 18 s 0 a + b u 0 e + f G q 0 a + b r 1 c + d E e 1 a + 17 t 0 c + d u 1 e + f e 3 (e 0, e 1) u 2 (u 0, u 1) v 0 a + b w 0 c + d x 0 e + f r 2 (r 0, r 1) y 0 a + b z 0 c + d Back to the discussion of value numbering over larger scopes. . . * 13

What About Larger Scopes? A We have not helped with F or G • Multiple predecessors B m 0 a + b n 0 a + b C p 0 c + d r 0 c + d D • Must decide what facts hold in F and in G For G, combine B & F? > Merging state is expensive > Fall back on what’s known > F G • Can use table from IDom(x ) to start x e 0 b + 18 s 0 a + b u 0 e + f q 0 a + b r 1 c + d E e 1 a + 17 t 0 c + d u 1 e + f e 3 (e 0, e 1) u 2 (u 0, u 1) v 0 a + b w 0 c + d x 0 e + f r 2 (r 0, r 1) y 0 a + b z 0 c + d Use C for F and A for G > Imposes a Dom-based application order > Leads to Dominator VN Technique (DVNT) COMP 512, Fall 2003 * 14

Dominator Value Numbering The DVNT Algorithm • Use superlocal algorithm on extended basic blocks > Retain use of scoped hash tables & SSA name space • Start each node with table from its IDom > DVNT generalizes the superlocal algorithm • No values flow along back edges • Constant folding, algebraic identities as before ( i. e. , around loops) Larger scope leads to (potentially) better results > Local + Superlocal + good start for new EBBs COMP 512, Fall 2003 15

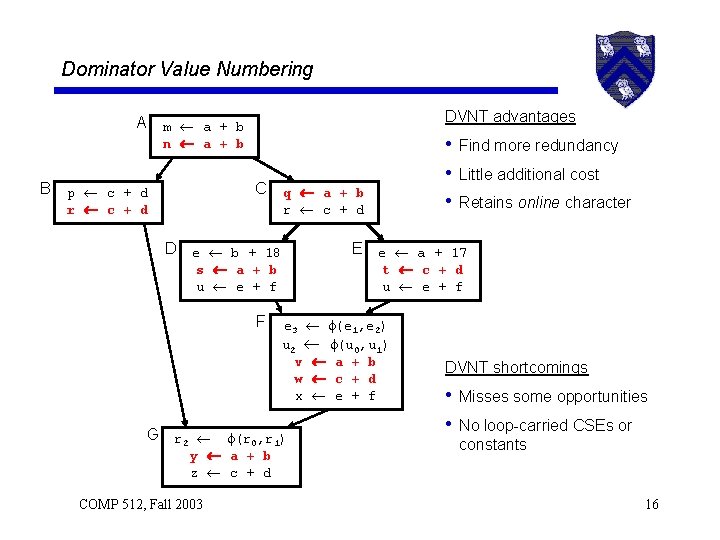

Dominator Value Numbering A B DVNT advantages m a + b n a + b C p c + d r c + d q a + b r c + d D e b + 18 E e a + 17 s a + b u e + f F G r 2 t c + d u e + f e 3 (e 1, e 2) u 2 (u 0, u 1) v a + b w c + d x e + f (r 0, r 1) y a + b z c + d COMP 512, Fall 2003 • Find more redundancy • Little additional cost • Retains online character DVNT shortcomings • Misses some opportunities • No loop-carried CSEs or constants 16

End of Lecture … COMP 512, Fall 2003 17

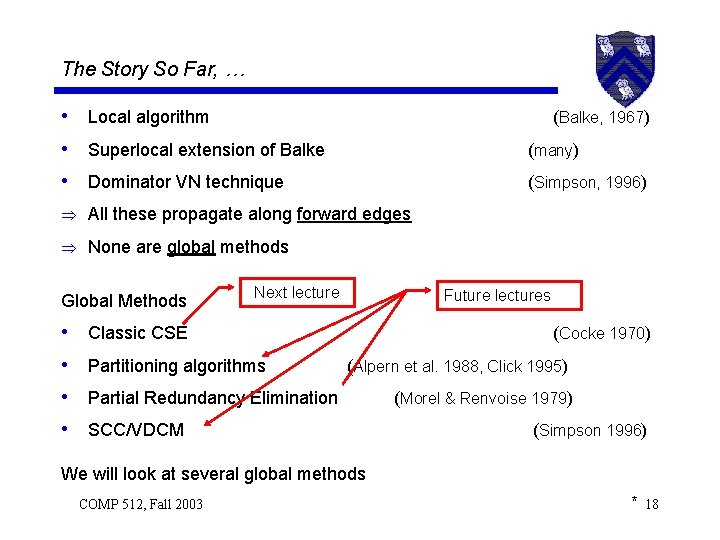

The Story So Far, … • Local algorithm • Superlocal extension of Balke • Dominator VN technique (Balke, 1967) (many) (Simpson, 1996) All these propagate along forward edges None are global methods Global Methods • • Next lecture Future lectures Classic CSE Partitioning algorithms (Cocke 1970) (Alpern et al. 1988, Click 1995) Partial Redundancy Elimination SCC/VDCM (Morel & Renvoise 1979) (Simpson 1996) We will look at several global methods COMP 512, Fall 2003 * 18

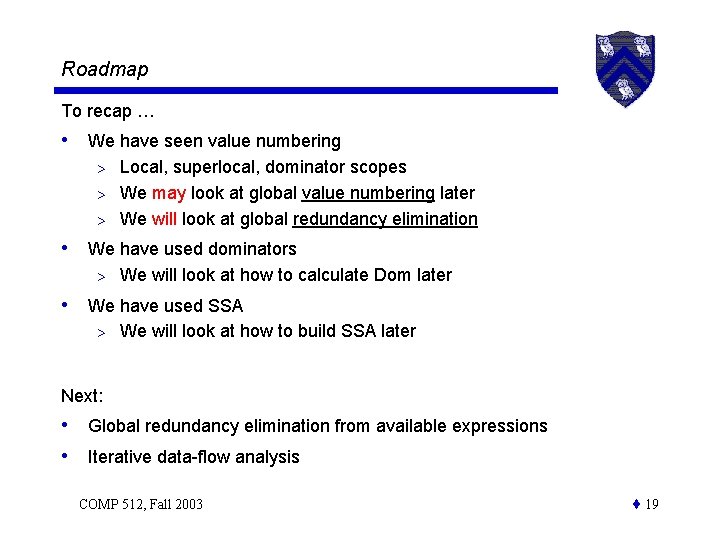

Roadmap To recap … • We have seen value numbering Local, superlocal, dominator scopes > We may look at global value numbering later > We will look at global redundancy elimination > • We have used dominators > We will look at how to calculate Dom later • We have used SSA > We will look at how to build SSA later Next: • Global redundancy elimination from available expressions • Iterative data-flow analysis COMP 512, Fall 2003 19

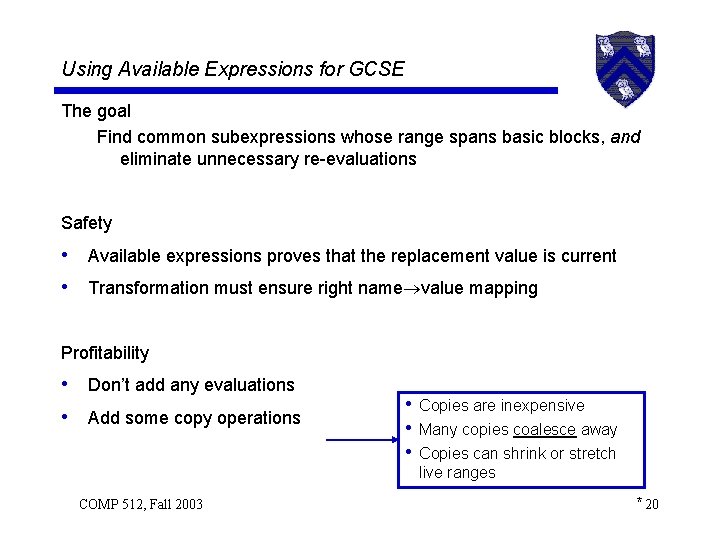

Using Available Expressions for GCSE The goal Find common subexpressions whose range spans basic blocks, and eliminate unnecessary re-evaluations Safety • Available expressions proves that the replacement value is current • Transformation must ensure right name value mapping Profitability • Don’t add any evaluations • Add some copy operations • Copies are inexpensive • Many copies coalesce away • Copies can shrink or stretch live ranges COMP 512, Fall 2003 * 20

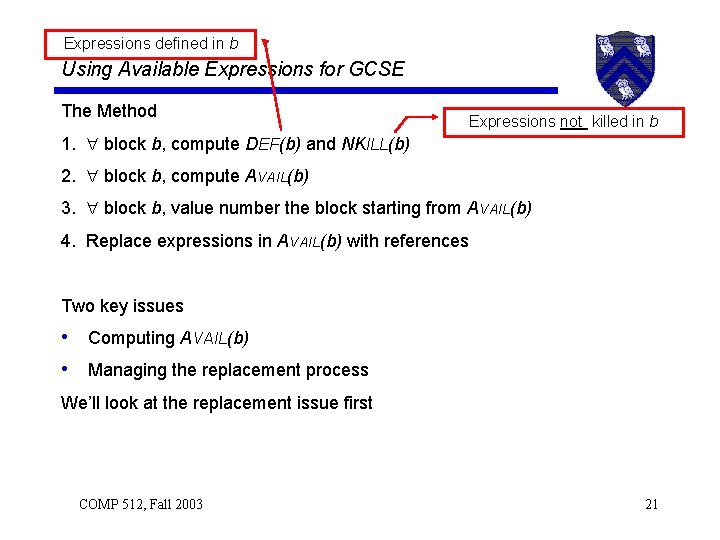

Expressions defined in b Using Available Expressions for GCSE The Method Expressions not killed in b 1. block b, compute DEF(b) and NKILL(b) 2. block b, compute AVAIL(b) 3. block b, value number the block starting from AVAIL(b) 4. Replace expressions in AVAIL(b) with references Two key issues • Computing AVAIL(b) • Managing the replacement process We’ll look at the replacement issue first COMP 512, Fall 2003 21

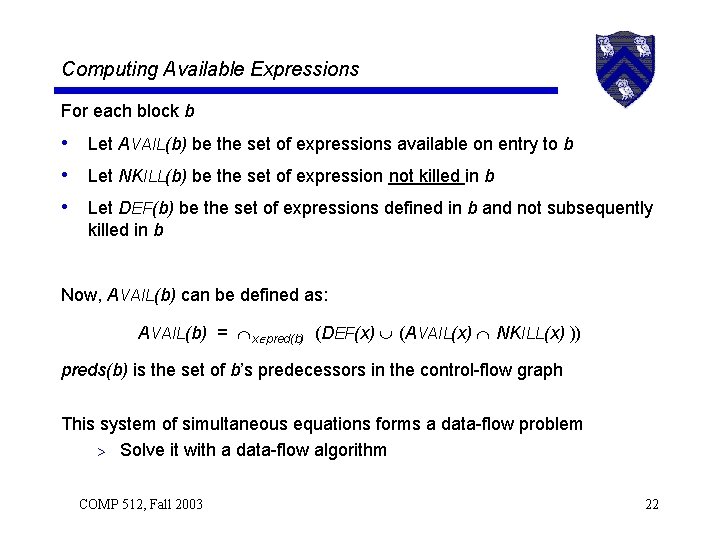

Computing Available Expressions For each block b • Let AVAIL(b) be the set of expressions available on entry to b • Let NKILL(b) be the set of expression not killed in b • Let DEF(b) be the set of expressions defined in b and not subsequently killed in b Now, AVAIL(b) can be defined as: AVAIL(b) = x pred(b) (DEF(x) (AVAIL(x) NKILL(x) )) preds(b) is the set of b’s predecessors in the control-flow graph This system of simultaneous equations forms a data-flow problem > Solve it with a data-flow algorithm COMP 512, Fall 2003 22

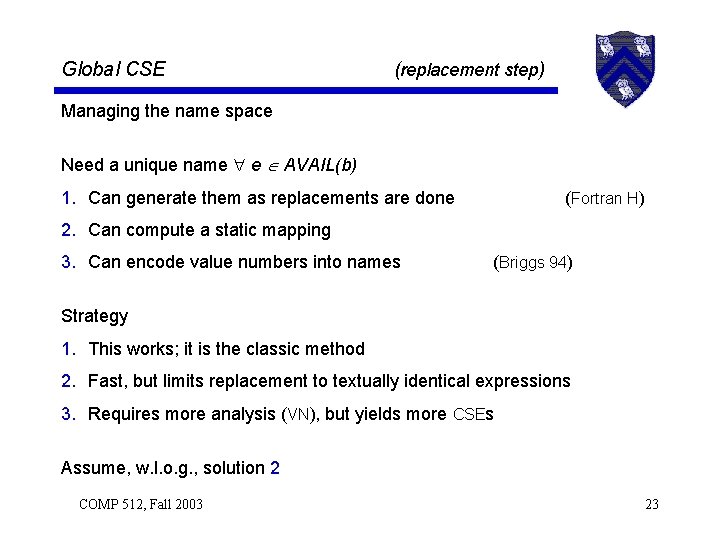

Global CSE (replacement step) Managing the name space Need a unique name e AVAIL(b) 1. Can generate them as replacements are done (Fortran H) 2. Can compute a static mapping 3. Can encode value numbers into names (Briggs 94) Strategy 1. This works; it is the classic method 2. Fast, but limits replacement to textually identical expressions 3. Requires more analysis (VN), but yields more CSEs Assume, w. l. o. g. , solution 2 COMP 512, Fall 2003 23

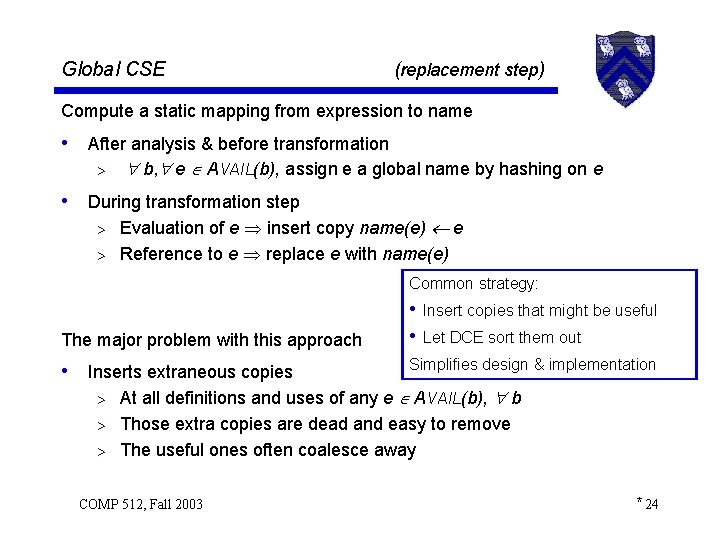

Global CSE (replacement step) Compute a static mapping from expression to name • After analysis & before transformation > b, e AVAIL(b), assign e a global name by hashing on e • During transformation step Evaluation of e insert copy name(e) e > Reference to e replace e with name(e) > Common strategy: The major problem with this approach • Inserts extraneous copies • Insert copies that might be useful • Let DCE sort them out Simplifies design & implementation At all definitions and uses of any e AVAIL(b), b > Those extra copies are dead and easy to remove > The useful ones often coalesce away > COMP 512, Fall 2003 * 24

An Aside on Dead Code Elimination What does “dead” mean? • Useless code — result is never used • Unreachable code — code that cannot execute • Both are lumped together as “dead” To perform DCE • Must have a global mechanism to recognize usefulness • Must have a global mechanism to eliminate unneeded stores • Must have a global mechanism to simplify control-flow predicates All of these will come later in the course COMP 512, Fall 2003 25

Global CSE Now a three step process • Compute AVAIL(b), block b • Assign unique global names to expressions in AVAIL(b) • Perform replacement with local value numbering Earlier in the lecture, we said Assume, without loss of generality, that we can compute available expressions for a procedure. This annotates each basic block, b, with a set AVAIL(b) that contains all expressions that are available on entry to b. Now, we need to make good on the assumption COMP 512, Fall 2003 26

Computing Available Expressions The Big Picture 1. Build a control-flow graph 2. Gather the initial (local) data — DEF(b) & NKILL(b) 3. Propagate information around the graph, evaluating the equation 4. Post-process the information to make it useful (if needed) All data-flow problems are solved, essentially, this way Next lecture: • Iterative computation of AVAIL information • From Chapter 8 of Ea. C COMP 512, Fall 2003 27

- Slides: 27