Optimization of Research Cheng Xiang Cheng Zhai Department

- Slides: 42

Optimization of Research Cheng. Xiang (“Cheng”) Zhai Department of Computer Science University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign 1

What is Research? • Research – Discover new knowledge – Seek answers to questions • Publishable research: the new knowledge has significant values for others • Basic research – Goal: Expand man’s knowledge (e. g. , which genes control social behavior of honey bees? ) – Often driven by curiosity (but not always) – High impact examples: relativity theory, DNA, … • Applied research – Goal: Improve human condition (i. e. , improve the wolrd) (e. g. , how to cure cancers? ) – Driven by practical needs – High impact examples: computers, transistors, vaccinations, … • The boundary is vague; distinction isn’t important 2

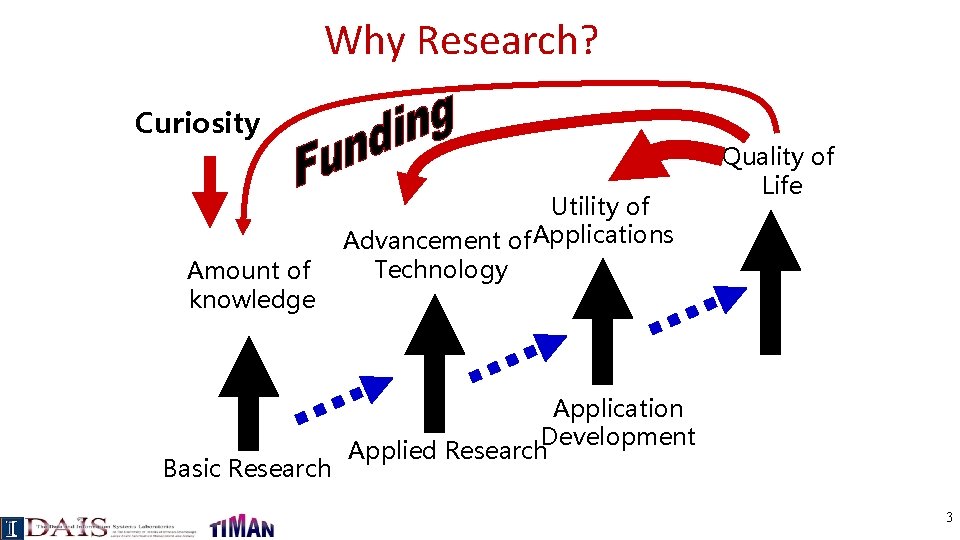

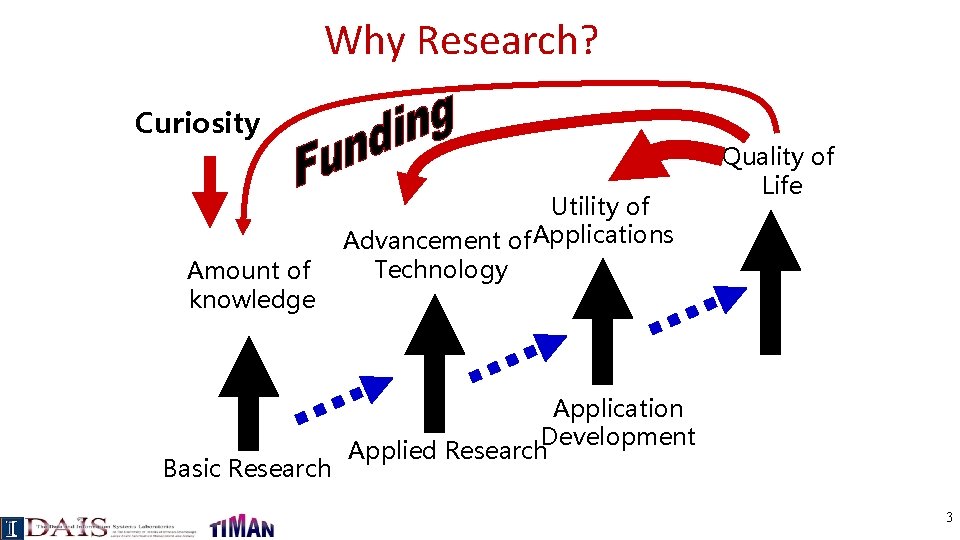

Why Research? Curiosity Amount of knowledge Basic Research Utility of Advancement of Applications Technology Quality of Life Application Development Applied Research 3

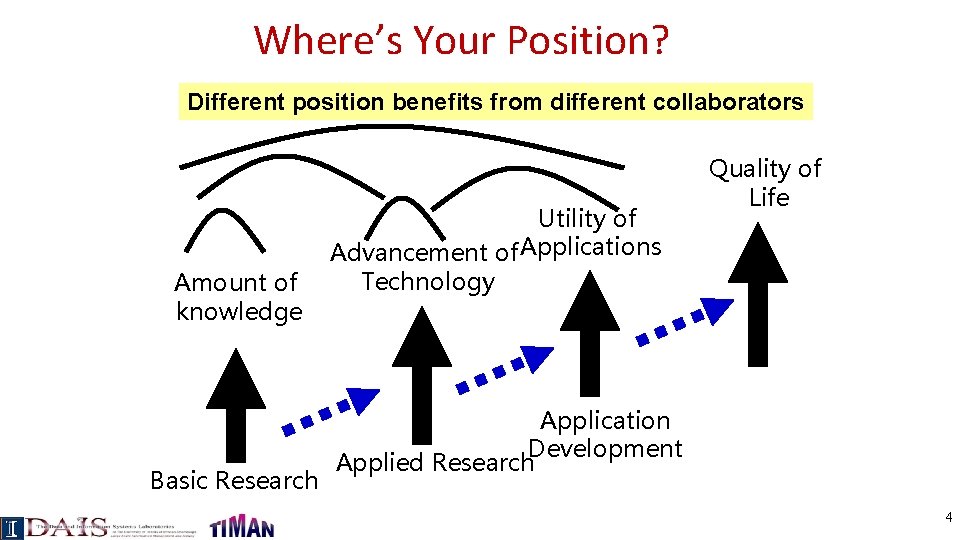

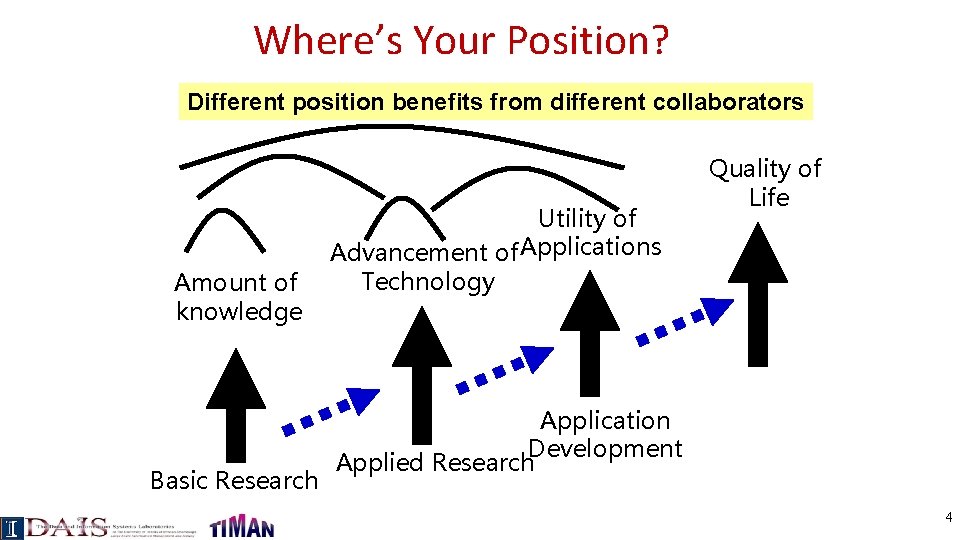

Where’s Your Position? Different position benefits from different collaborators Amount of knowledge Basic Research Utility of Advancement of Applications Technology Quality of Life Application Development Applied Research 4

Thoughts on Impact • Impact (Q, A)=Importance. Of. Problem(Q)*Qualityof. Solution(A) – Quality. Of. Answer(A): [0, 100/100], thus – Impact(Q, A) <=Importance. Of. Problem(Q) • Interactive impact: – Make Impact(P 1, …, Pk) >=Impact(P 1)+…+Impact(Pk) – This is possible if P 1, …, Pk form a coherent story (together they enable something bigger) • Suggestions: – Think big maximize Importance. Of. Problem – Solve synergistic problems maximize interactive impact – Strive for BEST solution maximize Qualityof. Solution 5

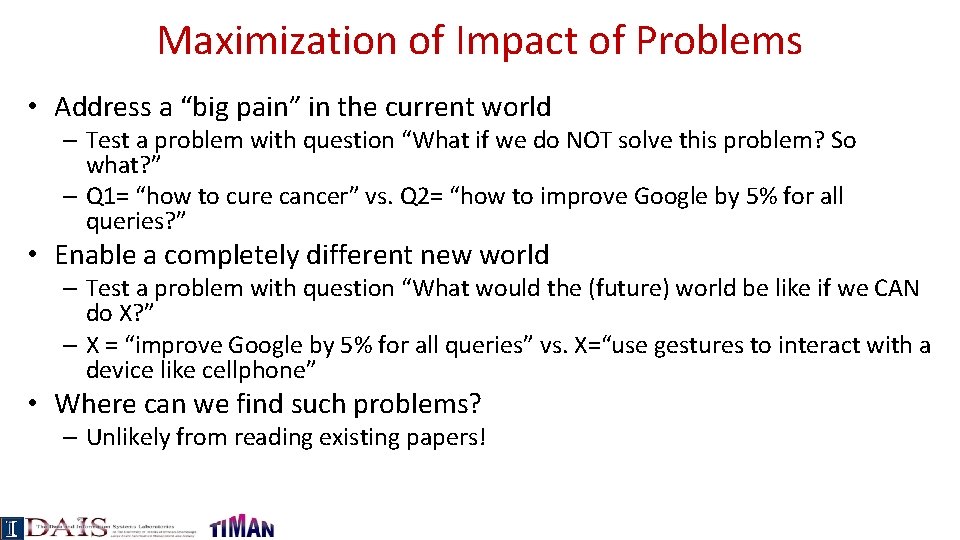

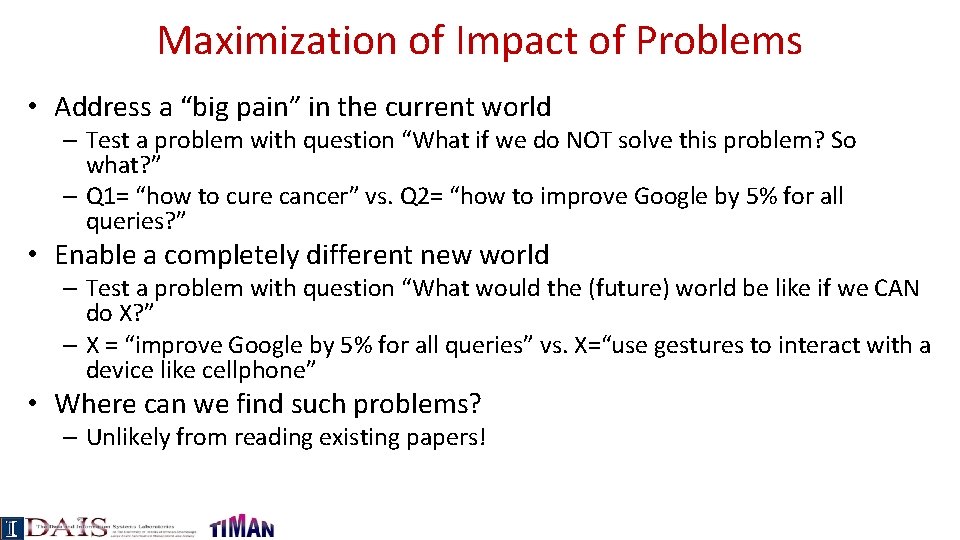

Maximization of Impact of Problems • Address a “big pain” in the current world – Test a problem with question “What if we do NOT solve this problem? So what? ” – Q 1= “how to cure cancer” vs. Q 2= “how to improve Google by 5% for all queries? ” • Enable a completely different new world – Test a problem with question “What would the (future) world be like if we CAN do X? ” – X = “improve Google by 5% for all queries” vs. X=“use gestures to interact with a device like cellphone” • Where can we find such problems? – Unlikely from reading existing papers!

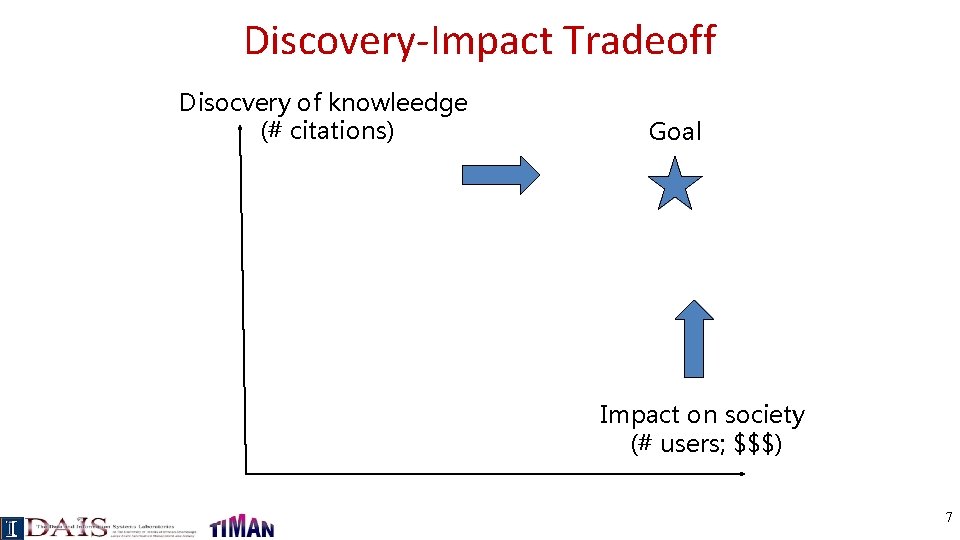

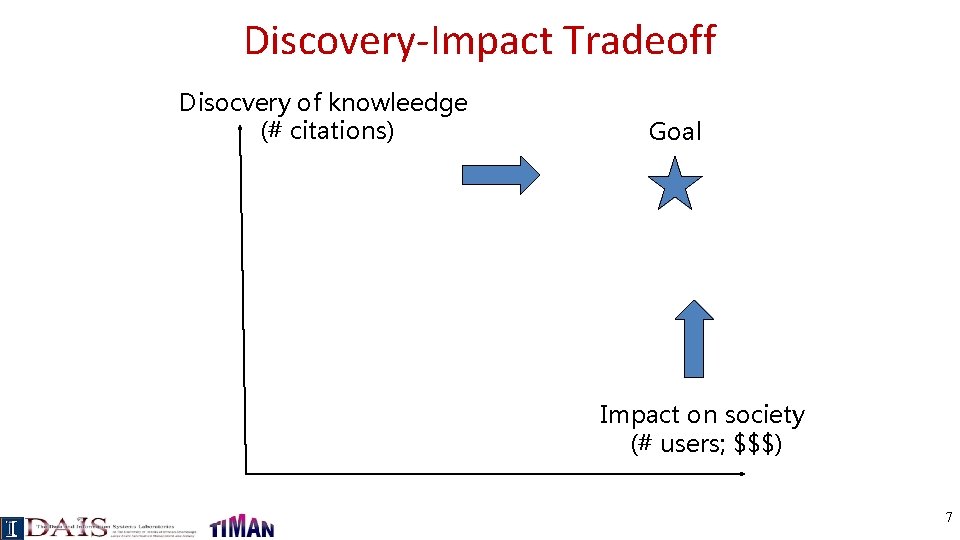

Discovery-Impact Tradeoff Disocvery of knowleedge (# citations) Goal Impact on society (# users; $$$) 7

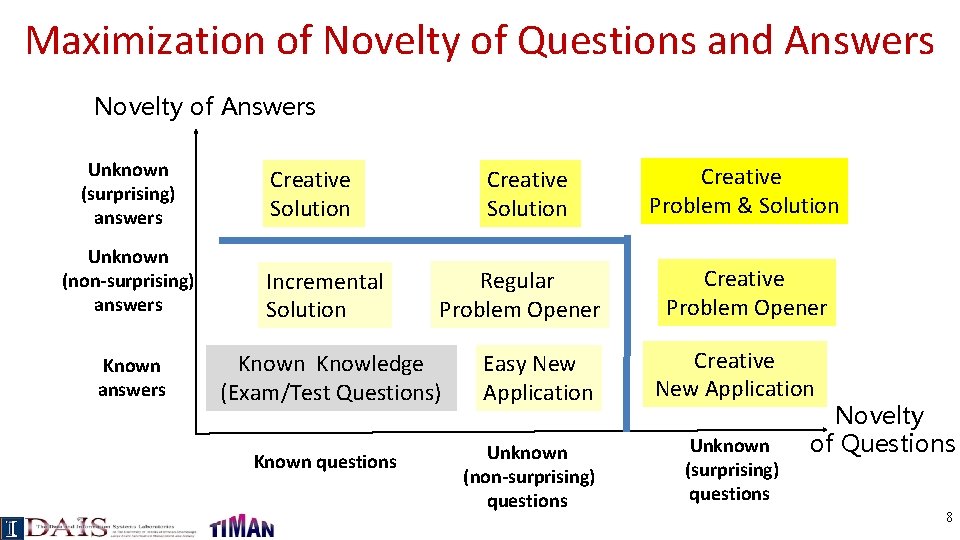

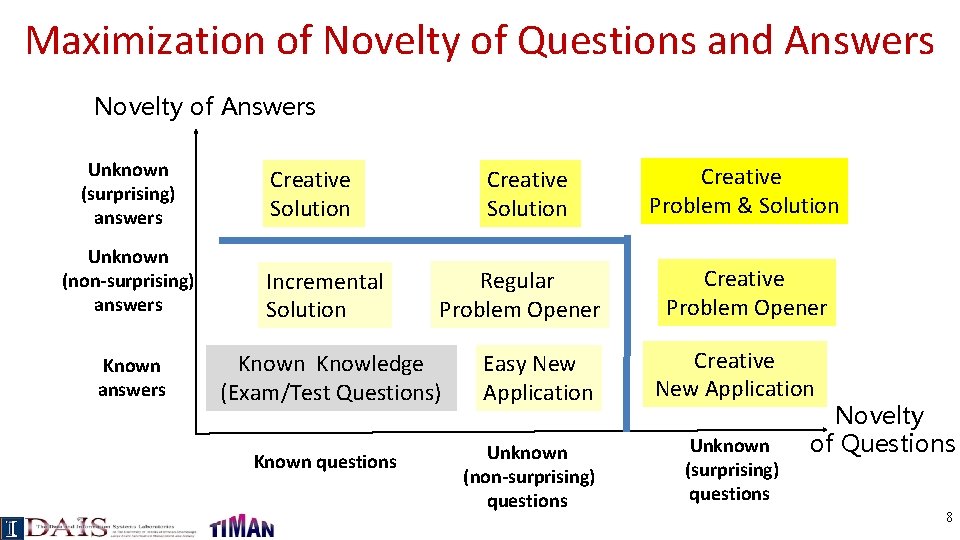

Maximization of Novelty of Questions and Answers Novelty of Answers Unknown (surprising) answers Unknown (non-surprising) answers Known answers Creative Solution Incremental Solution Creative Solution Regular Problem Opener Known Knowledge (Exam/Test Questions) Known questions Easy New Application Unknown (non-surprising) questions Creative Problem & Solution Creative Problem Opener Creative New Application Unknown (surprising) questions Novelty of Questions 8

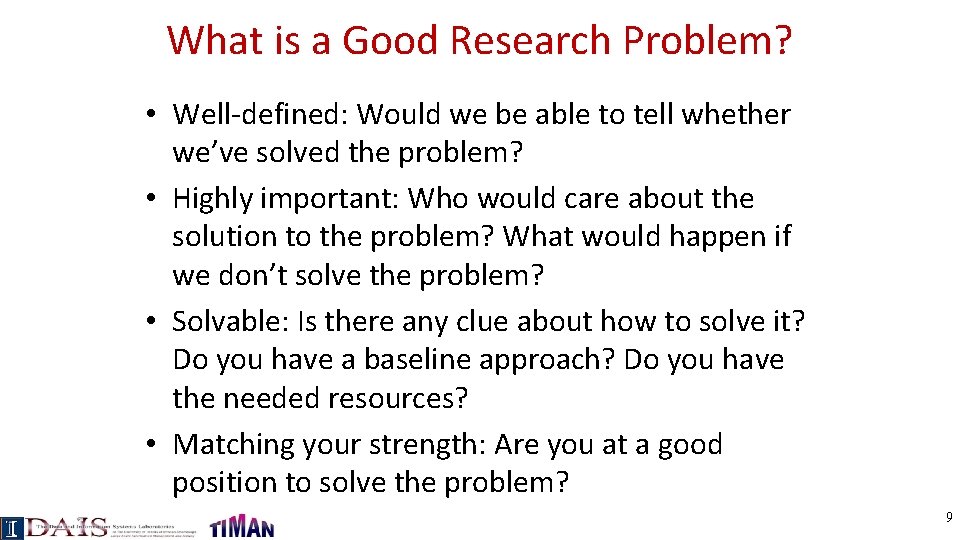

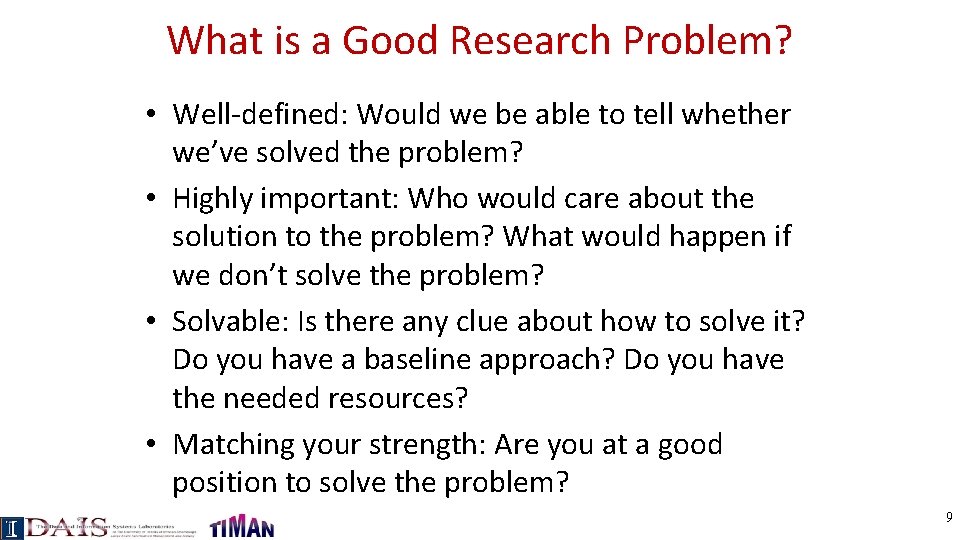

What is a Good Research Problem? • Well-defined: Would we be able to tell whether we’ve solved the problem? • Highly important: Who would care about the solution to the problem? What would happen if we don’t solve the problem? • Solvable: Is there any clue about how to solve it? Do you have a baseline approach? Do you have the needed resources? • Matching your strength: Are you at a good position to solve the problem? 9

How to Find a Problem? • Application-driven (Find a nail, then make a hammer) – Identify a need by people/users that cannot be satisfied well currently (“complaints” about current data/information management systems? ) – How difficult is it to solve the problem? • No big technical challenges: do a startup • Lots of big challenges: write a research proposal – Identify one technical challenge as your topic – Formulate/frame the problem appropriately so that you can solve it • Aim at a completely new application/function (find a high-stake nail) 10

How to Find a Problem? (cont. ) • Tool-driven (Hold a hammer, and look for a nail) – Choose your favorite state-of-the-art tools • Ideally, you have a “secret weapon” • Otherwise, bring tools from area X to area Y – Look around for possible applications – Find a novel application that seems to match your tools – How difficult is it to use your tools to solve the problem? • No big technical challenges: do a startup • Lots of big challenges: write a research proposal – Identify one technical challenge as your topic – Formulate/frame the problem appropriately so that you can solve it • Aim at important extension of the tool (find an unexpected application and use the best hammer) 11

How to Find a Problem? (cont. ) • In practice, you do both in various kinds of ways – You talk to people in application domains and identify new “nails” – You take courses and read books to acquire new “hammers” – You check out related areas for both new “nails” and new “hammers” – You read visionary papers and the “future work” sections of research papers, and then take a problem from there –… 12

General Steps to Define a Research Problem • Generate and Test: Raise a question and do the following tests • Novelty test: How novel is the question? You want to maximize novelty – Ideally, the question has never been studied in the existing literature – If it has been studied, what’s the reason for further studying the question? Can you identify any COMMON deficiency of ALL existing work addressing the problem? • Yes: your research problem is how to address the identified common deficiency • No: it’s not a compelling research problem (but can you make the question more challenging? ) • Importance/Impact test: How important is the question? What’s the expected impact? – Why do we need to address this question? What if we don’t address this question? – How would the world benefit from addressing this question? Who will benefit from it? – Aim to address a “big pain” or at least a “real pain” • Every time you reframe a problem, try to do all the tests again. 13

Rigorously Define Your Research Problem • Exploratory: what is the scope of exploration? What is the goal of exploration? Can you rigorously answer these questions? • Descriptive: what does it look like? How does it work? Can you formally define a principle? • Evaluative: can you clearly state the assumptions about data collection? Can you rigorously define measures? • Explanatory: how can you rigorously verify a cause? • Predictive: can you rigorously define what prediction is to be made? 14

Frame a New Computation Task • • Define basic concepts Specify the input Specify the output Specify any preferences or constraints 15

From a new application to a clearly defined research problem • Try to picture a new system, thus clarify what new functionality is to be provided and what benefit you’ll bring to a user • Among all the system modules, which are easy to build and which are challenging? • Pick a challenge and try to formalize the challenge – What exactly would be the input? – What exactly would be the output? • Is this challenge really a new challenge (not immediately clear how to solve it)? – Yes, your research problem is how to solve this new problem – No, it can be reduced to some known challenge: are existing methods sufficient? • Yes, not a good problem to work on • No, your research problem is how to extend/adapt existing methods to solve your new challenge • Tuning the problem

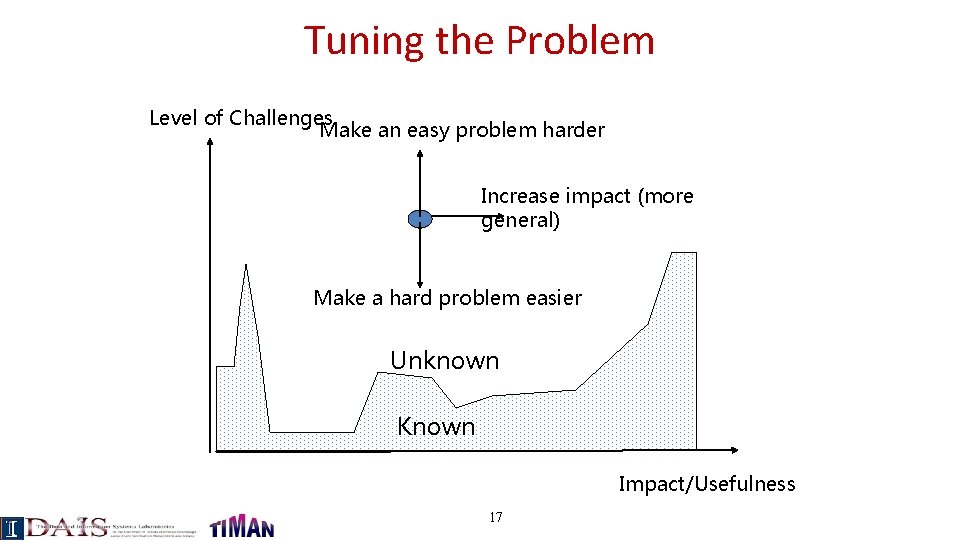

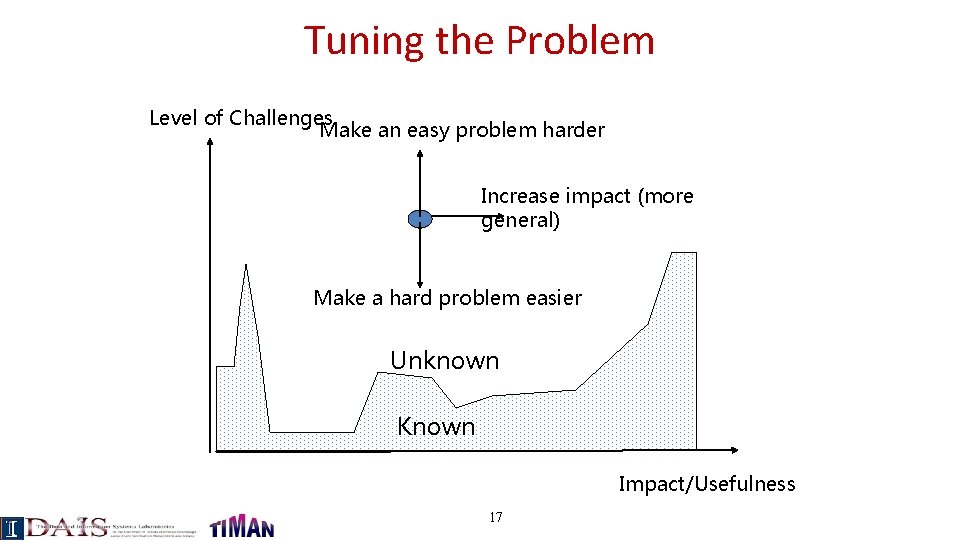

Tuning the Problem Level of Challenges Make an easy problem harder Increase impact (more general) Make a hard problem easier Unknown Known Impact/Usefulness 17

“Short-Cut” for starting IR research • • Scan most recently published papers to find papers that you like or can understand Read such papers in detail Track down background papers to increase your understanding Brainstorm ideas of extending the work – Start with ideas mentioned in the future work part – Systematically question the solidness of the paper (have the authors answered all the questions? Can you think of questions that aren’t answered? ) – Is there a better formulation of the problem – Is there a better method for solving the problem – Is the evaluation solid? • Pick one new idea and work on it 18

Formulate Research Hypotheses • Typical hypotheses in IR: – Hypothesis about user characteristics (tested with user studies or user-log analysis, e. g. , clickthrough bias) – Hypothesis about data characteristics (tested with fitting actual data, e. g. , Zipf’s law) – Hypothesis about methods (tested with experiments): • Method A works (or doesn’t work) for task B under condition C by measure D (feasibility) • Method A performs better than method A’ for task B under condition C by measure D (comparative) • Introduce baselines naturally lead to hypotheses • Carefully study existing literature to figure our where exactly you can make a new contribution (what do you want others to cite your work as? ) • The more specialized a hypothesis is, the more likely it’s new, but a narrow hypothesis has lower impact than a general one, so try to generalize as much as you can to increase impact • But avoid over-generalize (must be supported by your experiments) • Tuning hypotheses 19

Procedure of Hypothesis Testing • Clearly define the hypothesis to be tested (include any necessary conditions) • Design the right experiments to test it (experiments must match the hypothesis in all aspects) • Carefully analyze results (seek for understanding and explanation rather than just description) • Unless you’ve got a complete understanding of everything, always attempts to formulate a further hypothesis to achieve better understanding 20

Clearly Define a Hypothesis • A clearly defined hypothesis helps you choose the right data and right measures • Make sure to include any necessary conditions so that you don’t over claim • Be clear about any justification for your hypothesis (testing a random hypothesis requires more data than testing a well-justified hypothesis) 21

Design the Right Experiments • Flawed experiment design is a common cause of rejection of an IR paper (e. g. , a poorly chosen baseline) • The data should match the hypothesis – A general claim like “method A is better than B” would need a variety of representative data sets to prove • The measure should match the hypothesis – Multiple measures are often needed (e. g. , both precision and recall) • The experiment procedure shouldn’t be biased – Comparing A with B requires using identical procedure for both – Common mistake: baseline method not tuned or not tuned seriously • Test multiple hypotheses simultaneously if possible (for the sake of efficiency) 22

Carefully Analyze the Results • Do the significance test if possible/meaningful • Go beyond just getting a yes/no answer – If positive: seek for evidence to support your original justification of the hypothesis. – If negative: look into reasons to understand how your hypothesis should be modified – In general, seek for explanations of everything! • Get as much as possible out of the results of one experiment before jumping to run another – Don’t throw away negative data – Try to think of alternative ways of looking at data 23

Modify a Hypothesis • Don’t stop at the current hypothesis; try to generate a modified hypothesis to further discover new knowledge • If your hypothesis is supported, think about the possibility of further generalizing the hypothesis and test the new hypothesis • If your hypothesis isn’t supported, think about how to narrow it down to some special cases to see if it can be supported in a weaker form 24

Derive New Hypotheses • After you finish testing some hypotheses and reaching conclusions, try to see if you can derive interesting new hypotheses – Your data may suggest an additional (sometimes unrelated) hypothesis; you get a by-product – A new hypothesis can also logically follow a current hypothesis or help further support a current hypothesis • New hypotheses may help find causes: – If the cause is X, then H 1 must be true, so we test H 1 25

What It Takes to Do Research • • Curiosity: allow you to ask questions Critical thinking: allow you to challenge assumptions Learning: take you to the frontier of knowledge Persistence: so that you don’t give up Respect data and truth: ensure your research is solid Communication: allow you to publish your work … 26

Critical Thinking • • Develop a habit of asking questions, especially why questions Always try to make sense of what you have read/heard; don’t let any question pass by Get used to challenging everything Practical advice – Question every claim made in a paper or a talk (can you argue the other way? ) – Try to write two opposite reviews of a paper (one mainly to argue for accepting the paper and the other for rejecting it) – Force yourself to challenge one point in every talk that you attend and raise a question 27

Respect Data and Truth • Be honest with the experiment results – Don’t throw away negative results! – Try to learn from negative results • • Don’t twist data to fit your hypothesis; instead, let the hypothesis choose data Be objective in data analysis and interpretation; don’t mislead readers Aim at understanding/explanation instead of just good results Be careful not to over-generalize (for both good and bad results); you may be far from the truth 28

Communications • General communication skills: – Oral and written – Formal and informal – Talk to people with different level of backgrounds • Be clear, concise, accurate, and adaptive (elaborate with examples, summarize by abstraction) • English proficiency • Get used to talking to people from different fields 29

Persistence • Work only on topics that you are passionate about • Work only on hypotheses that you believe in • Don’t draw negative conclusions prematurely and give up easily – positive results may be hidden in negative results – In many cases, negative results don’t completely reject a hypothesis • Be comfortable with criticisms about your work (learn from negative reviews of a rejected paper) • Think of possibilities of repositioning a work 30

Optimize Your Training • Know your strengths and weaknesses – strong in math vs. strong in system development – creative vs. thorough –… • Train yourself to fix weaknesses • Find strategic partners • Position yourself to take advantage of your strengths 31

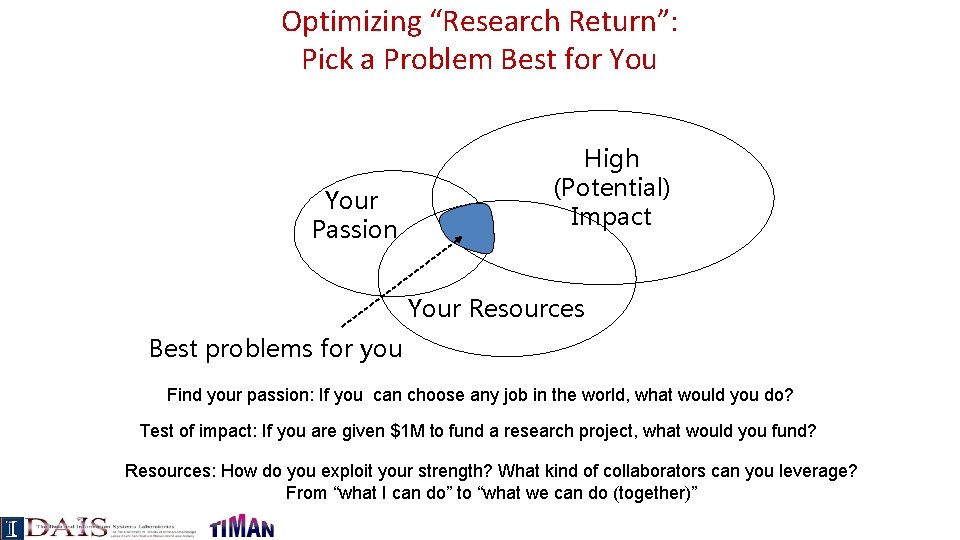

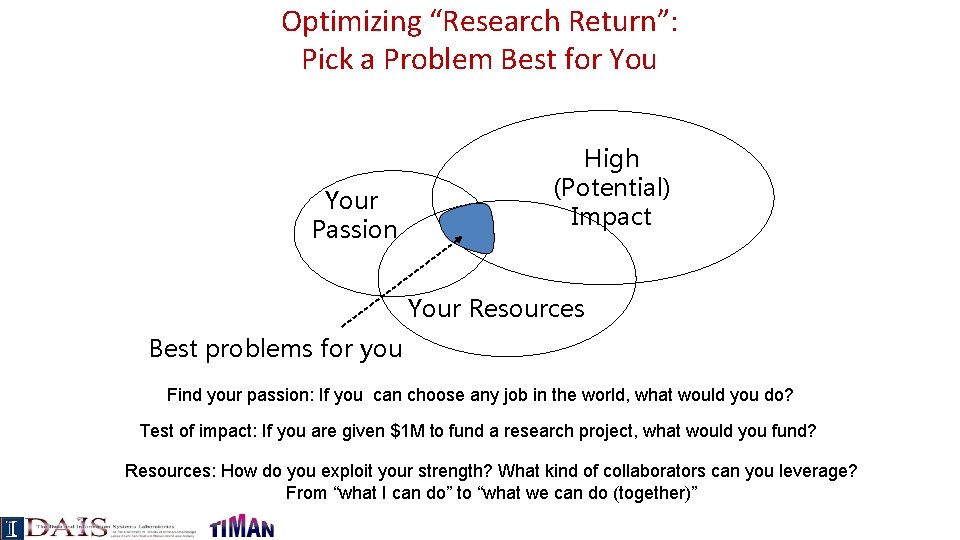

Optimizing “Research Return”: Pick a Problem Best for Your Passion High (Potential) Impact Your Resources Best problems for you Find your passion: If you can choose any job in the world, what would you do? Test of impact: If you are given $1 M to fund a research project, what would you fund? Resources: How do you exploit your strength? What kind of collaborators can you leverage? From “what I can do” to “what we can do (together)”

Typical Structure of a Research Paper • 1. Introduction Background discussion to motivate your problem Define your problem Argue why it’s important to solve the problem Identify knowledge gap in existing work or point out deficiency of existing answers/solutions – Summarize your contributions – Briefly mention potential impact – – • Tips: – Start with sentences understandable to almost everyone – Tell the story at a high-level so that the entire introduction is understandable to people with no/little technical background in the topic – Use examples if possible

Typical Structure of a Research Paper (cont. ) • 2. Previous/Related work – Sometimes this part is included in the introduction or appears later – Previous work = work that you extend (readers must be familiar with it to understand your contribution) – Related work = work related to your work (readers can until later in the paper to know about it) • Tips: – Make sure not to miss important related work – Always safer to include more related work – Discuss the existing work and its connection to your work • Your work extends … • Your work is similar to … but differs in that … • Your work represents an alternative way of … – Whenever possible, explicitly discuss your contribution in the context of existing work

Typical Structure of a Research Paper (cont. ) • 3. Problem definition/formulation – Clearly define your problem • If it’s a new problem, discuss its relation to existing related problems • If it’s an old problem, cite the previous work – Justify why you define the problem in this way – Discuss challenges in solving the problem • Tips: – Give both an informal description and a formal description if possible – Make sure that you mention any assumption you make when defining the problem (e. g. , your focus may be on studying the problem in certain conditions)

Typical Structure of a Research Paper (cont. ) • 4. Overview of the solution(s) (can be merged with the next part) – Give a high-level information description of the proposed solutions or solutions you study – Use examples if possible • 5. Specific components of your solution(s) – Be precise (formal description helps) – Use intuitive descriptions to help people understand it • Tips: – make sure that you organize this part so that it’s understandable to people with various backgrounds – Don’t just throw in formulas; include high-level intuitive descriptions whenever possible

Typical Structure of a Research Paper (cont. ) • 6. Experiment design: make sure you justify it – Data set – Measures – Experiment procedure • Tips: – Given enough details so that people can reproduce your experiments – Discuss limitation/bias if any, and discuss its potential influence on your study 37

Typical Structure of a Research Paper (cont. ) • 7. Result analysis: – Organized based on research questions to be answered or hypotheses tested – Be comprehensive, but focus on the major conclusions – Include “standard” components • • • Baseline comparison Individual component analysis Parameter sensitivity analysis Individual query analysis Significance test – Discuss the influence of any bias or limitation • Tips – Don’t leave any question unanswered (try to provide an explanation for all the observed results) – Discuss your findings in the context of existing work if possible • Similar observations have also been made in … • This is in contrast to … observed in … One explanation is …. 38

Typical Structure of a Research Paper (cont. ) • 8. Conclusions and future work – Summarize your contributions – Discuss its potential impact – Discuss its limitation and point out directions for future work • 9. References 39

Tips on Polishing your Paper • Start with the core messages you want to convey in the paper and expand your paper by following the core story • Try to convey the core messages at different levels so that people with different knowledge background can all get them • Try to write a review of your paper yourself, commenting on its originality, technical soundness, significance, evaluation, etc, and then revise the paper if needed • Check out reviewer’s instructions, e. g. , the following: http: //nips 07. stanford. edu/nips 07 reviewers. html (not necessarily matching your conference, but should share a lot of common requirements) • Try to polish English as much as you can 40

After You Get Reviews Back • Carefully classify comments into: – Unreasonable comments (e. g. , misunderstanding): • Try to improve the clarity of your writing – Reasonable comments • Constructive: easy to implement • Non-constructive: think about it, either argue the other way or mention weakness of your work in the paper • If paper is accepted – Take the last chance to polish the paper as much as you can – You’ll regret if later you discover an inaccurate statement or a typo in your published paper • If paper is rejected – Digest comments and try to improve the research work and the paper – Run more experiments if necessary – Don’t try to please reviewers (the next reviewer might say something opposite); instead use your own judgments and use their comments to help improve your judgments – Reposition the paper if necessary (again, don’t reposition it just because a reviewer rejected your original positioning) 41

Summary • Research is about discovery and increase our knowledge (innovation & understanding) • Intellectual curiosity and critical thinking are extremely important • Work on important problems that you are passionate about • Aim at becoming a top expert in one topic area – Obtain complete knowledge about the literature on the topic (read all the important papers and monitor the progress) – Write a survey if appropriate – Publish one or more high-quality papers on the topic • Don’t give up! 42