Optimalittstheorie und Pragmatik Kompaktseminar an der Universitt Wien

- Slides: 30

Optimalitätstheorie und Pragmatik Kompaktseminar an der Universität Wien Sommersemester 2005 Manfred Krifka Stochastische Optimalitätstheorie Lernalgorithmen Evolutionäre Optimalitätstheorie

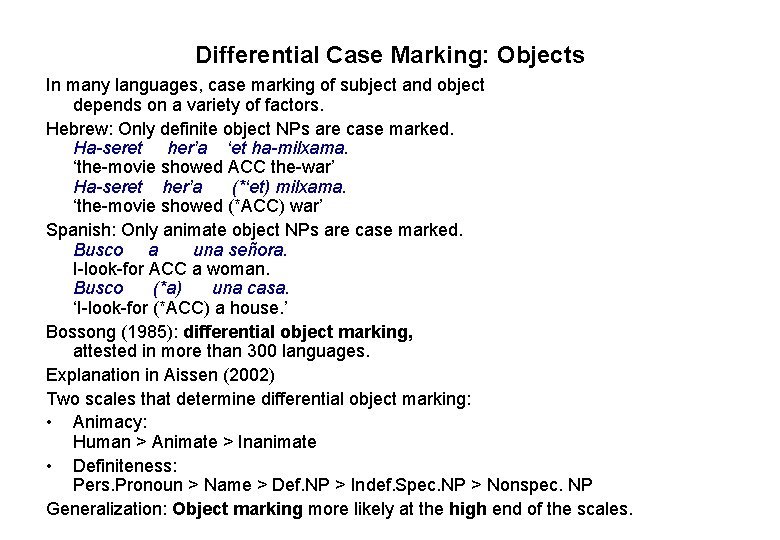

Differential Case Marking: Objects In many languages, case marking of subject and object depends on a variety of factors. Hebrew: Only definite object NPs are case marked. Ha-seret her’a ‘et ha-milxama. ‘the-movie showed ACC the-war’ Ha-seret her’a (*‘et) milxama. ‘the-movie showed (*ACC) war’ Spanish: Only animate object NPs are case marked. Busco a una señora. I-look-for ACC a woman. Busco (*a) una casa. ‘I-look-for (*ACC) a house. ’ Bossong (1985): differential object marking, attested in more than 300 languages. Explanation in Aissen (2002) Two scales that determine differential object marking: • Animacy: Human > Animate > Inanimate • Definiteness: Pers. Pronoun > Name > Def. NP > Indef. Spec. NP > Nonspec. NP Generalization: Object marking more likely at the high end of the scales.

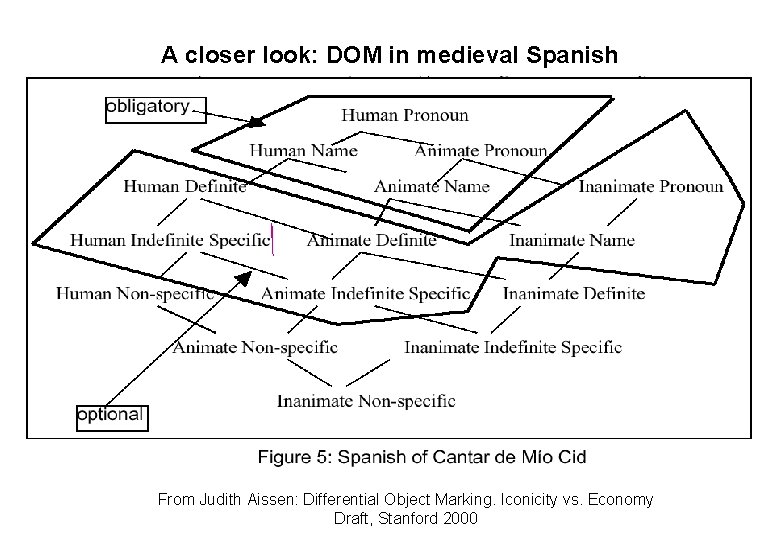

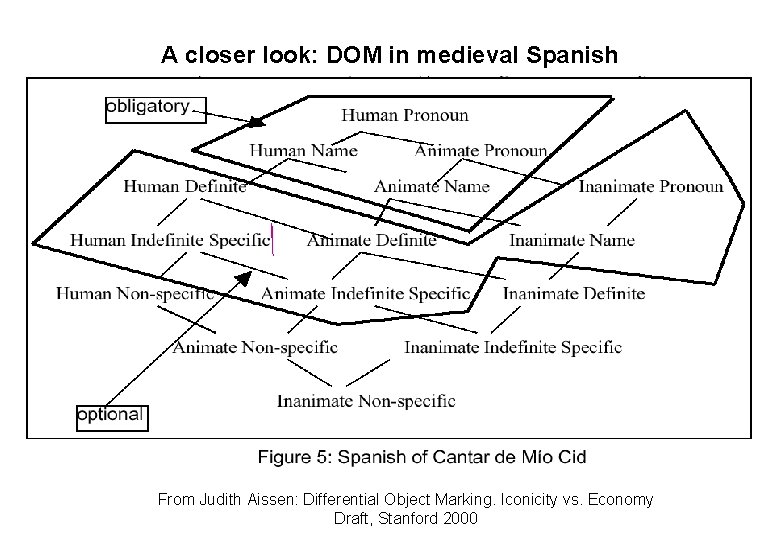

A closer look: DOM in medieval Spanish From Judith Aissen: Differential Object Marking. Iconicity vs. Economy Draft, Stanford 2000

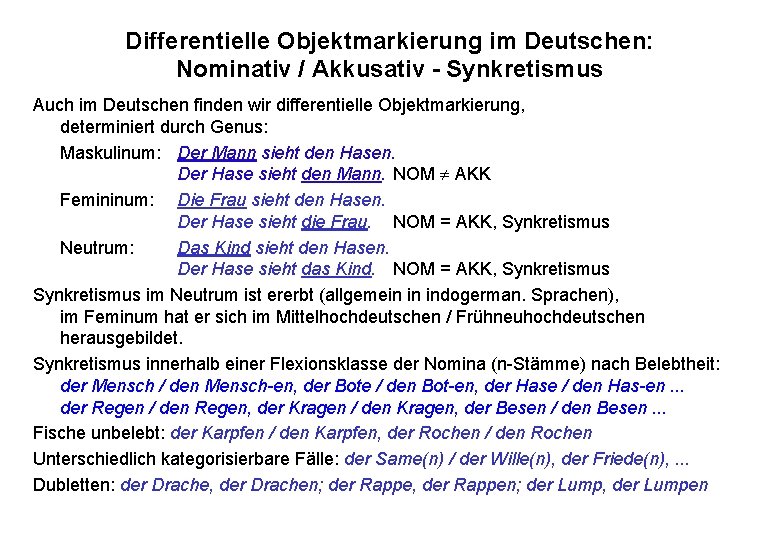

Differentielle Objektmarkierung im Deutschen: Nominativ / Akkusativ - Synkretismus Auch im Deutschen finden wir differentielle Objektmarkierung, determiniert durch Genus: Maskulinum: Der Mann sieht den Hasen. Der Hase sieht den Mann. NOM AKK Femininum: Die Frau sieht den Hasen. Der Hase sieht die Frau. NOM = AKK, Synkretismus Neutrum: Das Kind sieht den Hasen. Der Hase sieht das Kind. NOM = AKK, Synkretismus im Neutrum ist ererbt (allgemein in indogerman. Sprachen), im Feminum hat er sich im Mittelhochdeutschen / Frühneuhochdeutschen herausgebildet. Synkretismus innerhalb einer Flexionsklasse der Nomina (n-Stämme) nach Belebtheit: der Mensch / den Mensch-en, der Bote / den Bot-en, der Hase / den Has-en. . . der Regen / den Regen, der Kragen / den Kragen, der Besen / den Besen. . . Fische unbelebt: der Karpfen / den Karpfen, der Rochen / den Rochen Unterschiedlich kategorisierbare Fälle: der Same(n) / der Wille(n), der Friede(n), . . . Dubletten: der Drache, der Drachen; der Rappe, der Rappen; der Lump, der Lumpen

Differentielle Objektmarkierung im Deutschen: Nominativ / Akkusativ - Synkretismus Belebtheit als ein Faktor des Kasus-Synkretismus im Allgemeinen: Maskuline Nomina sind wahrscheinlicher belebt als femine. Beispiel: Korpus von Ruoff (1981), 500. 000 Wörter, gesprochene Alltagserzählungen aus dem schwäbischen Raum

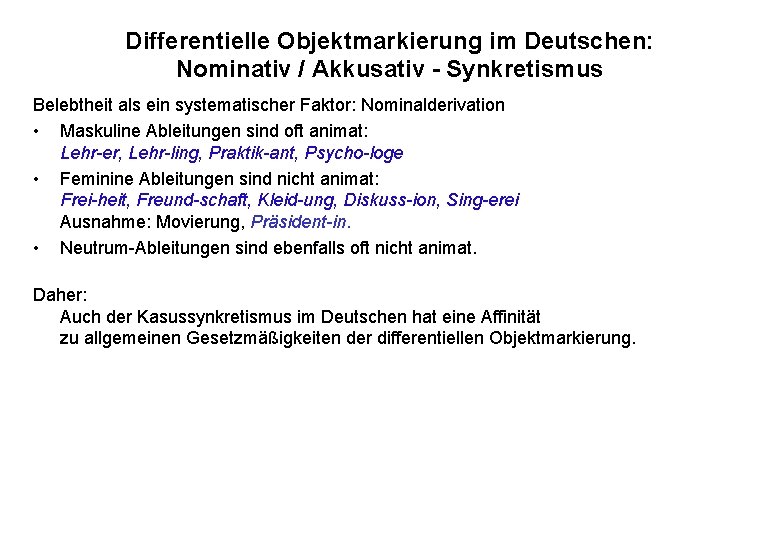

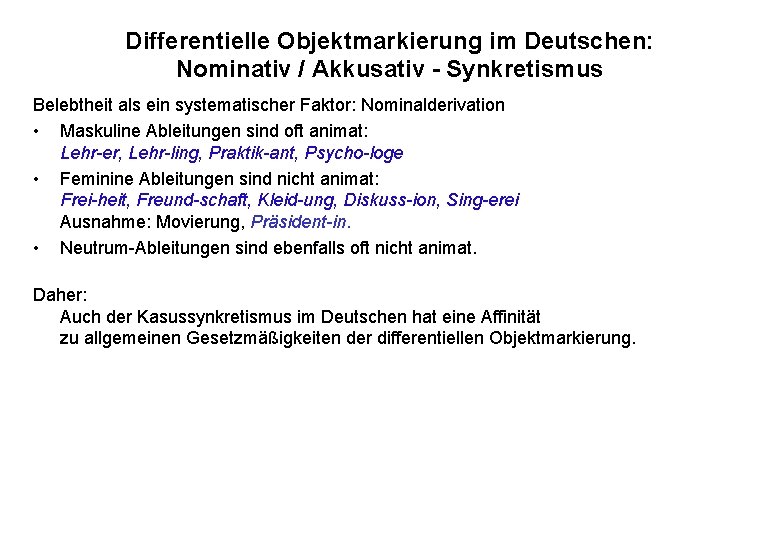

Differentielle Objektmarkierung im Deutschen: Nominativ / Akkusativ - Synkretismus Belebtheit als ein systematischer Faktor: Nominalderivation • Maskuline Ableitungen sind oft animat: Lehr-er, Lehr-ling, Praktik-ant, Psycho-loge • Feminine Ableitungen sind nicht animat: Frei-heit, Freund-schaft, Kleid-ung, Diskuss-ion, Sing-erei Ausnahme: Movierung, Präsident-in. • Neutrum-Ableitungen sind ebenfalls oft nicht animat. Daher: Auch der Kasussynkretismus im Deutschen hat eine Affinität zu allgemeinen Gesetzmäßigkeiten der differentiellen Objektmarkierung.

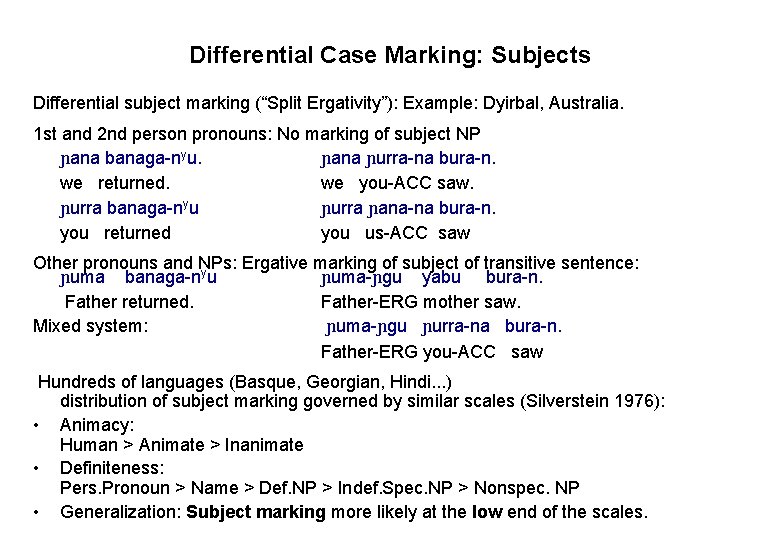

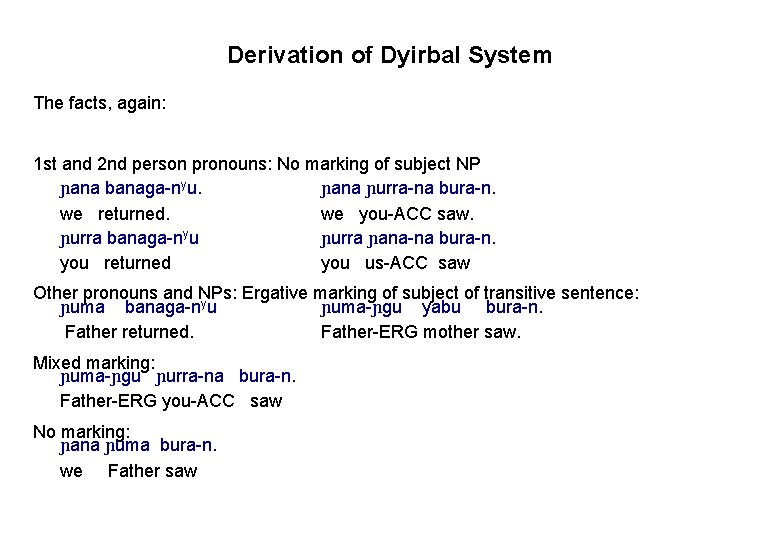

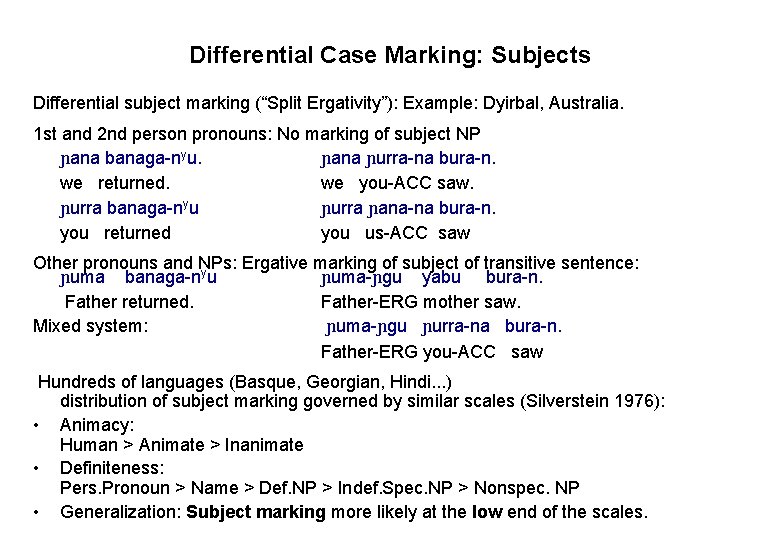

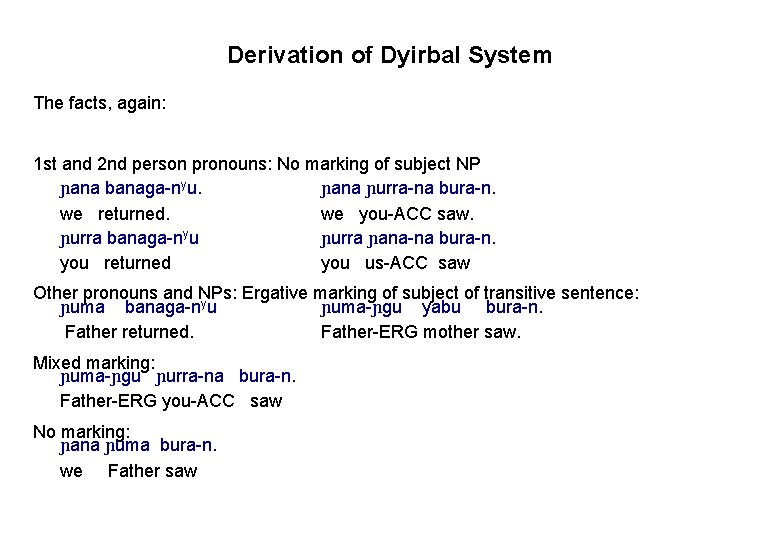

Differential Case Marking: Subjects Differential subject marking (“Split Ergativity”): Example: Dyirbal, Australia. 1 st and 2 nd person pronouns: No marking of subject NP ɲana banaga-nyu. ɲana ɲurra-na bura-n. we returned. we you-ACC saw. ɲurra banaga-nyu ɲurra ɲana-na bura-n. you returned you us-ACC saw Other pronouns and NPs: Ergative marking of subject of transitive sentence: ɲuma banaga-nyu ɲuma-ɲgu yabu bura-n. Father returned. Father-ERG mother saw. Mixed system: ɲuma-ɲgu ɲurra-na bura-n. Father-ERG you-ACC saw Hundreds of languages (Basque, Georgian, Hindi. . . ) distribution of subject marking governed by similar scales (Silverstein 1976): • Animacy: Human > Animate > Inanimate • Definiteness: Pers. Pronoun > Name > Def. NP > Indef. Spec. NP > Nonspec. NP • Generalization: Subject marking more likely at the low end of the scales.

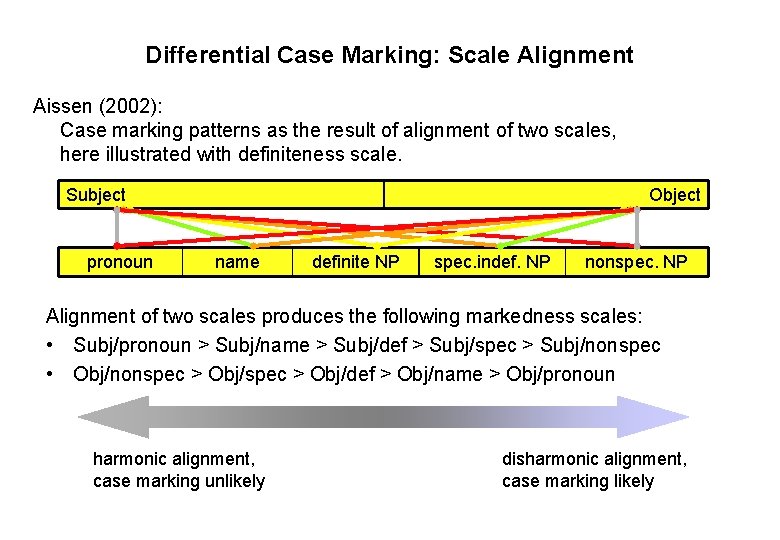

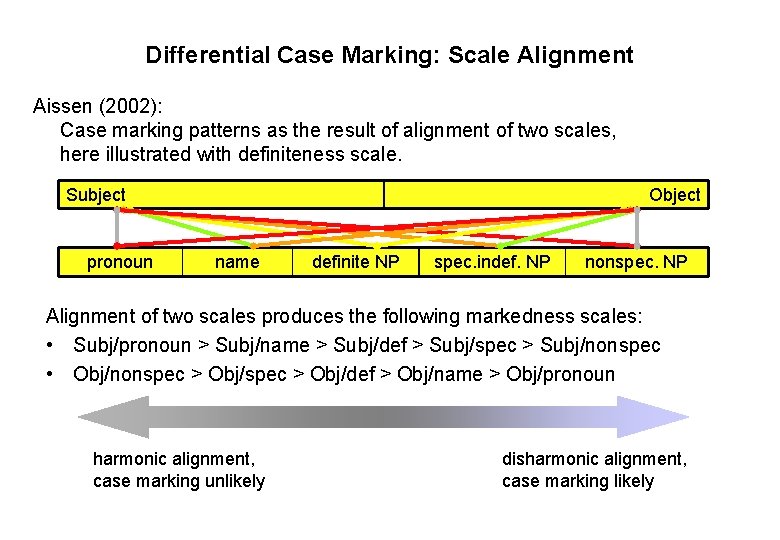

Differential Case Marking: Scale Alignment Aissen (2002): Case marking patterns as the result of alignment of two scales, here illustrated with definiteness scale. Subject pronoun Object name definite NP spec. indef. NP nonspec. NP Alignment of two scales produces the following markedness scales: • Subj/pronoun > Subj/name > Subj/def > Subj/spec > Subj/nonspec • Obj/nonspec > Obj/def > Obj/name > Obj/pronoun harmonic alignment, case marking unlikely disharmonic alignment, case marking likely

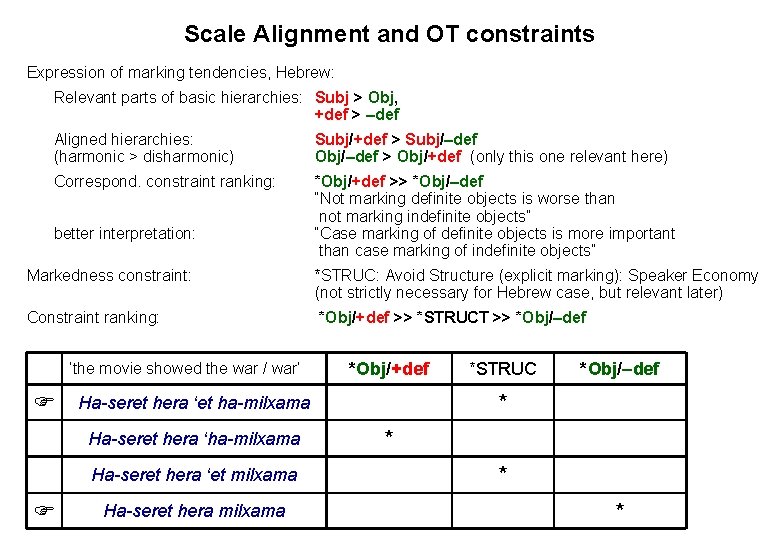

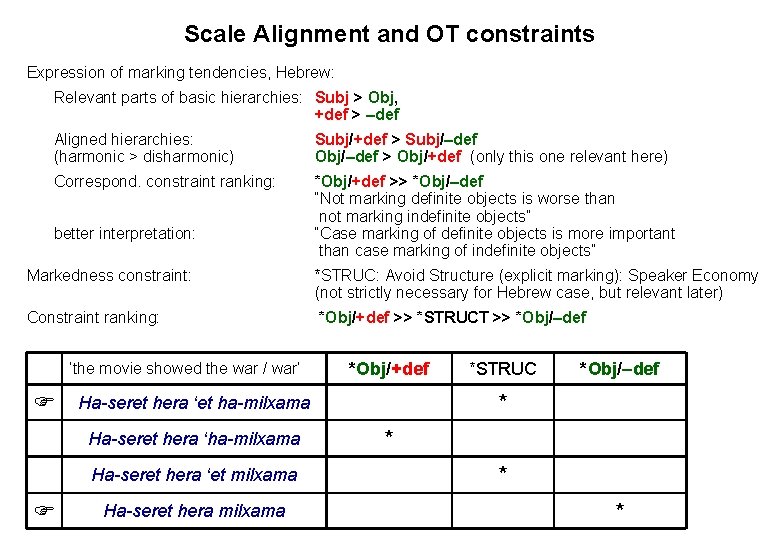

Scale Alignment and OT constraints Expression of marking tendencies, Hebrew: Relevant parts of basic hierarchies: Subj > Obj, +def > –def Aligned hierarchies: (harmonic > disharmonic) Subj/+def > Subj/–def Obj/–def > Obj/+def (only this one relevant here) Correspond. constraint ranking: *Obj/+def >> *Obj/–def “Not marking definite objects is worse than not marking indefinite objects” “Case marking of definite objects is more important than case marking of indefinite objects” better interpretation: Markedness constraint: *STRUC: Avoid Structure (explicit marking): Speaker Economy (not strictly necessary for Hebrew case, but relevant later) Constraint ranking: *Obj/+def >> *STRUCT >> *Obj/–def ‘the movie showed the war / war’ Ha-seret hera ‘et milxama Ha-seret hera milxama *STRUC *Obj/–def * Ha-seret hera ‘et ha-milxama Ha-seret hera ‘ha-milxama *Obj/+def * * *

Derivation of Dyirbal System The facts, again: 1 st and 2 nd person pronouns: No marking of subject NP ɲana banaga-nyu. ɲana ɲurra-na bura-n. we returned. we you-ACC saw. ɲurra banaga-nyu ɲurra ɲana-na bura-n. you returned you us-ACC saw Other pronouns and NPs: Ergative marking of subject of transitive sentence: y ɲuma banaga-n u ɲuma-ɲgu yabu bura-n. Father returned. Father-ERG mother saw. Mixed marking: ɲuma-ɲgu ɲurra-na bura-n. Father-ERG you-ACC saw No marking: ɲana ɲuma bura-n. we Father saw

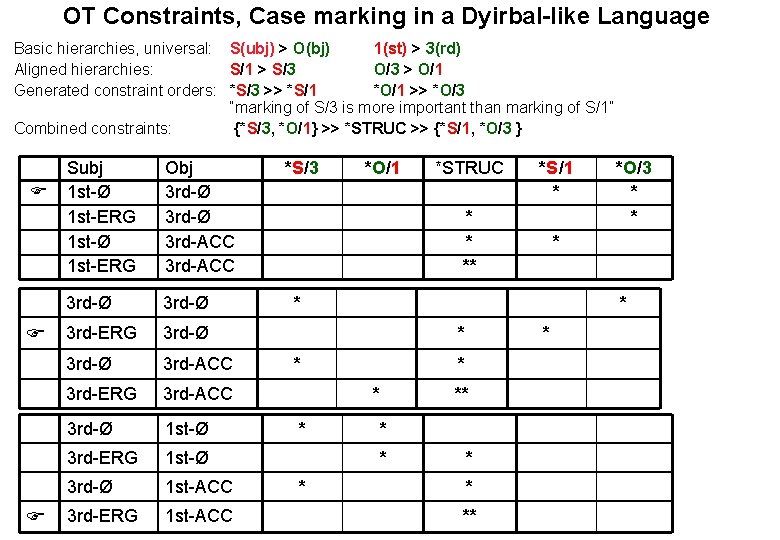

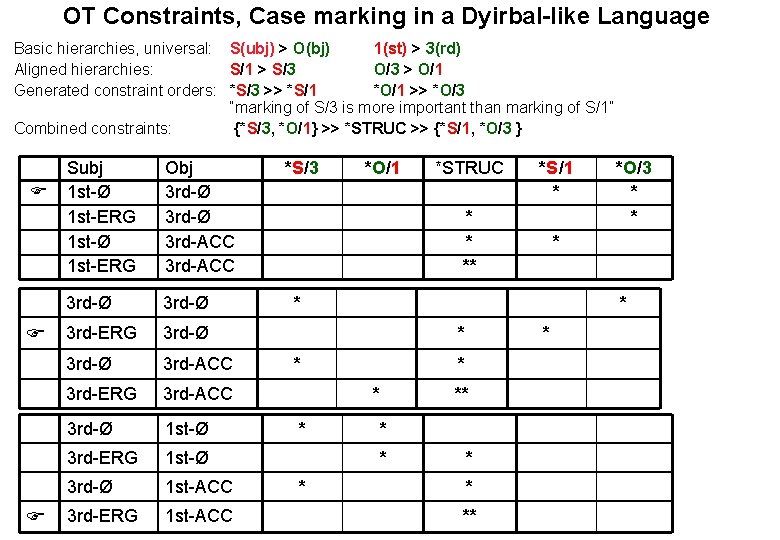

OT Constraints, Case marking in a Dyirbal-like Language Basic hierarchies, universal: S(ubj) > O(bj) 1(st) > 3(rd) Aligned hierarchies: S/1 > S/3 O/3 > O/1 Generated constraint orders: *S/3 >> *S/1 *O/1 >> *O/3 “marking of S/3 is more important than marking of S/1” Combined constraints: {*S/3, *O/1} >> *STRUC >> {*S/1, *O/3 } Subj 1 st-Ø 1 st-ERG Obj 3 rd-Ø 3 rd-ACC 3 rd-Ø 3 rd-ERG 3 rd-Ø 3 rd-ACC 3 rd-ERG 3 rd-ACC 3 rd-Ø 1 st-Ø 3 rd-ERG 1 st-Ø 3 rd-Ø 1 st-ACC 3 rd-ERG 1 st-ACC *S/3 *O/1 *STRUC *S/1 * * * ** * *O/3 * * **

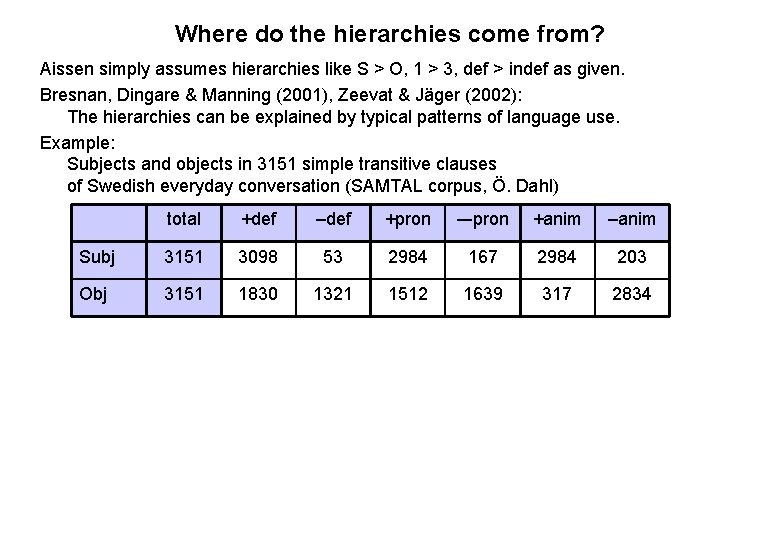

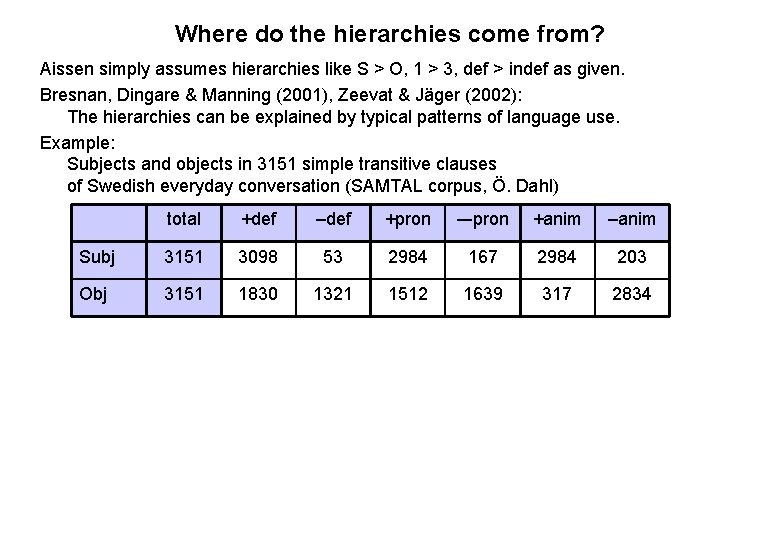

Where do the hierarchies come from? Aissen simply assumes hierarchies like S > O, 1 > 3, def > indef as given. Bresnan, Dingare & Manning (2001), Zeevat & Jäger (2002): The hierarchies can be explained by typical patterns of language use. Example: Subjects and objects in 3151 simple transitive clauses of Swedish everyday conversation (SAMTAL corpus, Ö. Dahl) total +def –def +pron –-pron +anim –anim Subj 3151 3098 53 2984 167 2984 203 Obj 3151 1830 1321 1512 1639 317 2834

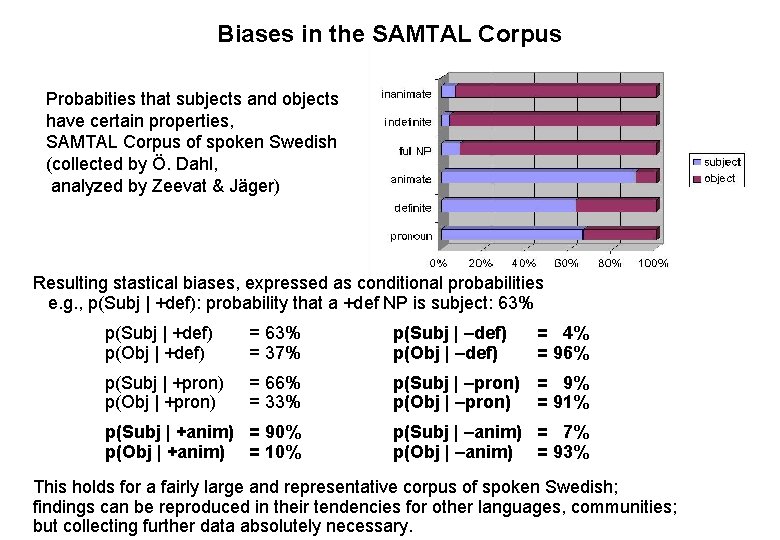

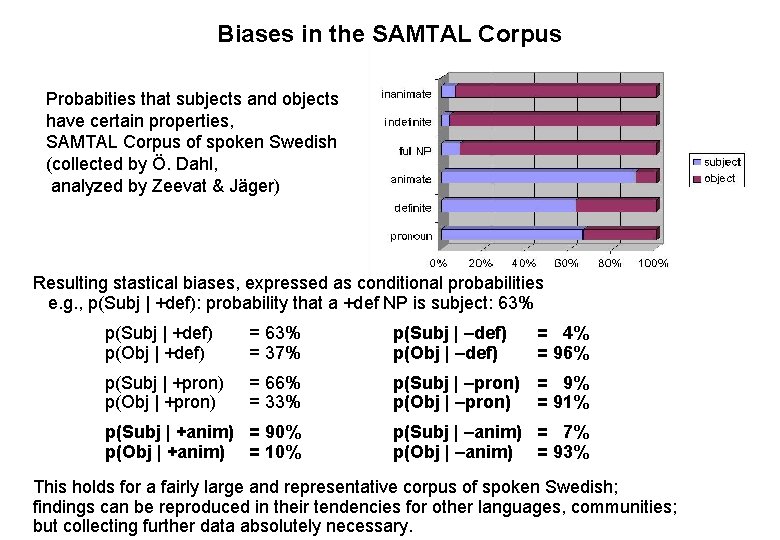

Biases in the SAMTAL Corpus Probabities that subjects and objects have certain properties, SAMTAL Corpus of spoken Swedish (collected by Ö. Dahl, analyzed by Zeevat & Jäger) Resulting stastical biases, expressed as conditional probabilities e. g. , p(Subj | +def): probability that a +def NP is subject: 63% p(Subj | +def) p(Obj | +def) = 63% = 37% p(Subj | –def) p(Obj | –def) = 4% = 96% p(Subj | +pron) p(Obj | +pron) = 66% = 33% p(Subj | –pron) = 9% p(Obj | –pron) = 91% p(Subj | +anim) = 90% p(Obj | +anim) = 10% p(Subj | –anim) = 7% p(Obj | –anim) = 93% This holds for a fairly large and representative corpus of spoken Swedish; findings can be reproduced in their tendencies for other languages, communities; but collecting further data absolutely necessary.

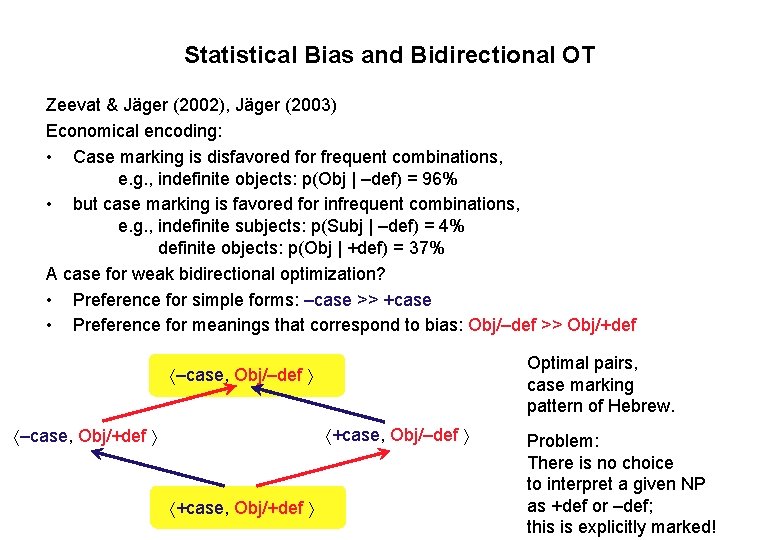

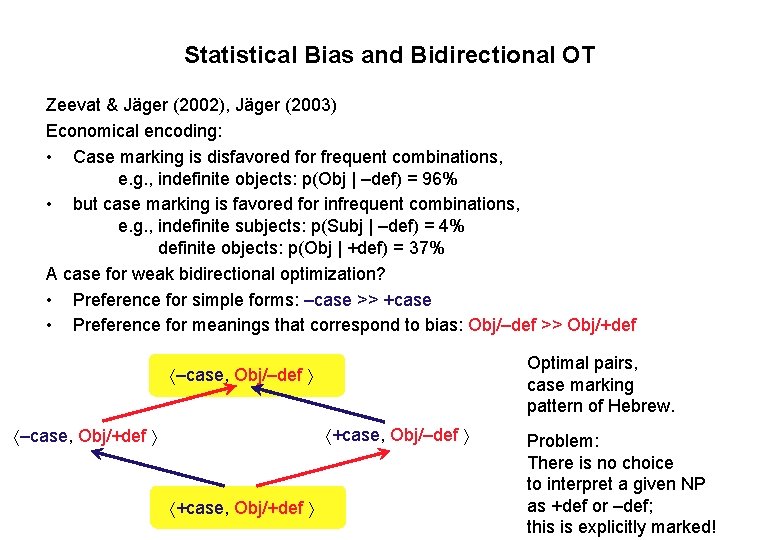

Statistical Bias and Bidirectional OT Zeevat & Jäger (2002), Jäger (2003) Economical encoding: • Case marking is disfavored for frequent combinations, e. g. , indefinite objects: p(Obj | –def) = 96% • but case marking is favored for infrequent combinations, e. g. , indefinite subjects: p(Subj | –def) = 4% definite objects: p(Obj | +def) = 37% A case for weak bidirectional optimization? • Preference for simple forms: –case >> +case • Preference for meanings that correspond to bias: Obj/–def >> Obj/+def Optimal pairs, case marking pattern of Hebrew. –case, Obj/–def +case, Obj/–def –case, Obj/+def +case, Obj/+def Problem: There is no choice to interpret a given NP as +def or –def; this is explicitly marked!

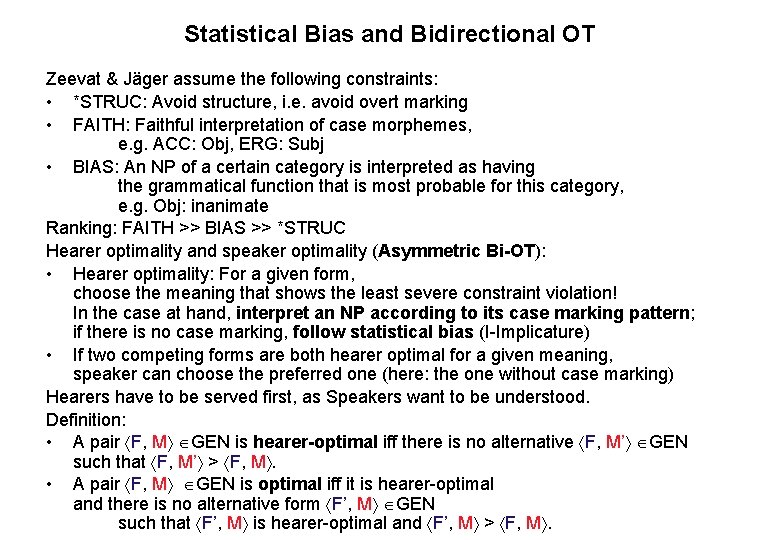

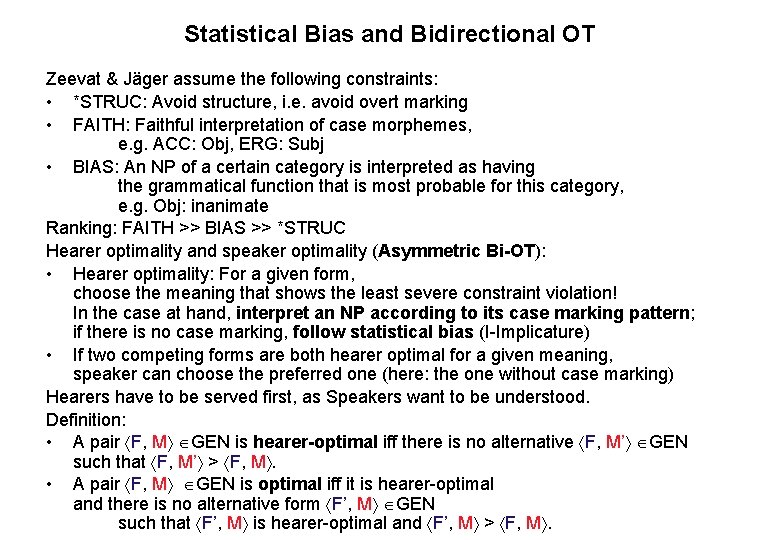

Statistical Bias and Bidirectional OT Zeevat & Jäger assume the following constraints: • *STRUC: Avoid structure, i. e. avoid overt marking • FAITH: Faithful interpretation of case morphemes, e. g. ACC: Obj, ERG: Subj • BIAS: An NP of a certain category is interpreted as having the grammatical function that is most probable for this category, e. g. Obj: inanimate Ranking: FAITH >> BIAS >> *STRUC Hearer optimality and speaker optimality (Asymmetric Bi-OT): • Hearer optimality: For a given form, choose the meaning that shows the least severe constraint violation! In the case at hand, interpret an NP according to its case marking pattern; if there is no case marking, follow statistical bias (I-Implicature) • If two competing forms are both hearer optimal for a given meaning, speaker can choose the preferred one (here: the one without case marking) Hearers have to be served first, as Speakers want to be understood. Definition: • A pair F, M GEN is hearer-optimal iff there is no alternative F, M’ GEN such that F, M’ > F, M. • A pair F, M GEN is optimal iff it is hearer-optimal and there is no alternative form F’, M GEN such that F’, M is hearer-optimal and F’, M > F, M.

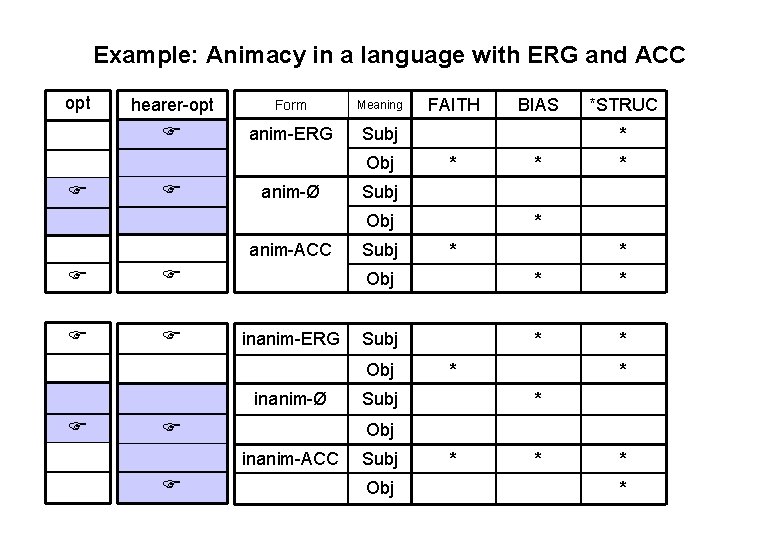

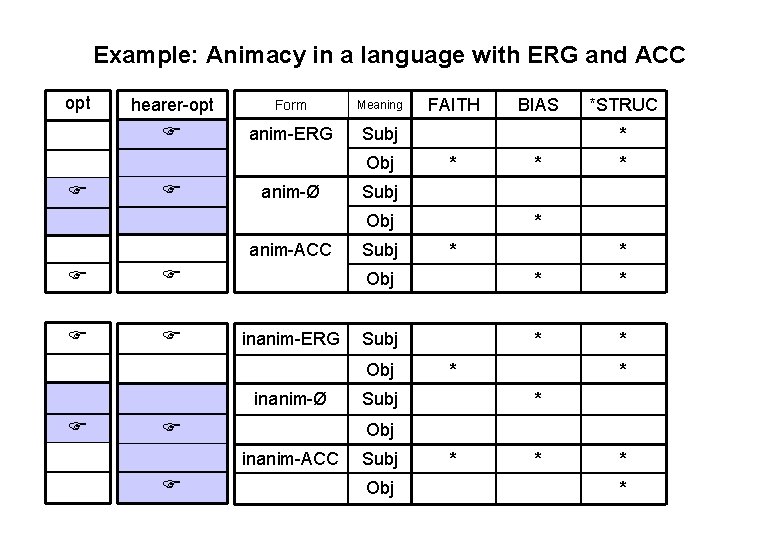

Example: Animacy in a language with ERG and ACC opt hearer-opt Form Meaning anim-ERG Subj Obj anim-Ø FAITH inanim-ERG * * Subj * * * Obj * * Subj * * Obj inanim-ACC * Subj Obj inanim-Ø *STRUC * Obj anim-ACC BIAS Subj Obj * *

From Pragmatics to Grammar? One caveat: The OT-tableaus typically abstract away from important factors, e. g. word order, plausibility, selectional restrictions. The lightning killed the man. Even though the man is animate and in object position, it wouldn’t need case marking, as only animates can be killed. A second caveat: Case marking is typically part of the core grammar, and not derived by pragmatic rules. But: Pragmatic tendencies as one source of core grammar (functionalist view of grammar).

Motivation for Stochastic Optimality Theory Judith Aissen (2000) and Joan Bresnan (2002): There is not just a universal tendency towards differential case marking in the core grammars of language, but it can be also describe optional case marking within a language. Example: Case marking by postpositions in colloquial Japanese (data: Fry 2001, Ellipsis and w-marking in Japanese): Subj/anim: 60% Subj/inanim: 70% Obj/anim: 54% Obj/inanim: 47% Obligatory case marking patterns can be seen as extreme cases of statistical marking patterns, e. g. Spanish: Obj/anim: 100% Obj/inanim: 0% Stochastic Optimaltiy Theory (St. OT), Boersma (1998), Functional Phonology developed originally for phonological phenomena, can be used to model this intuition: Core grammar phenomena are not essentially different from statistical tendencies based on usage in phenomena that core grammar leaves, to a certain degree, optional.

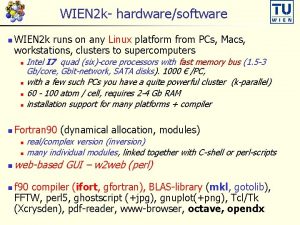

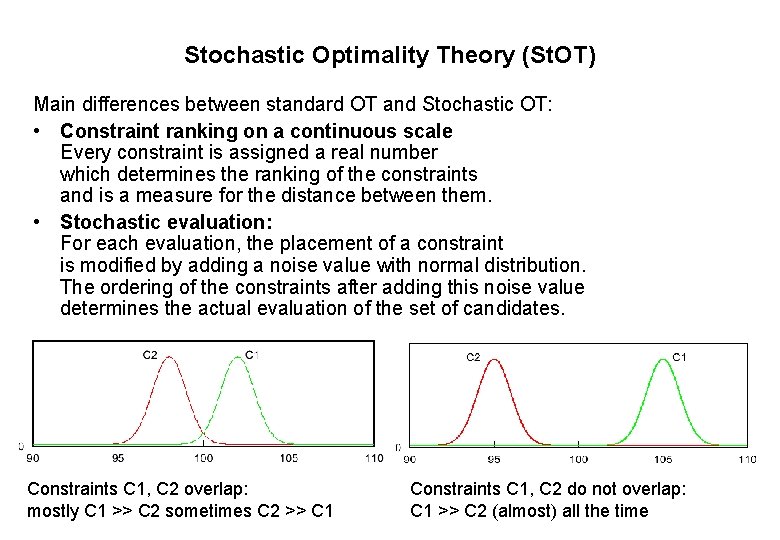

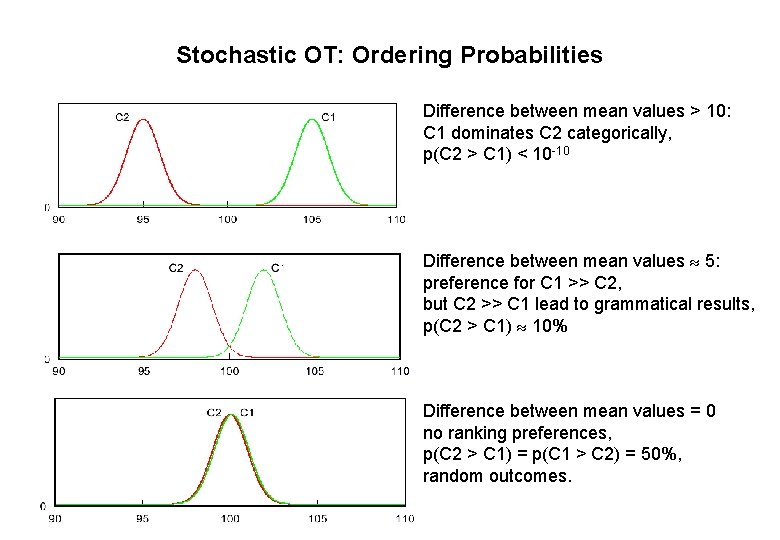

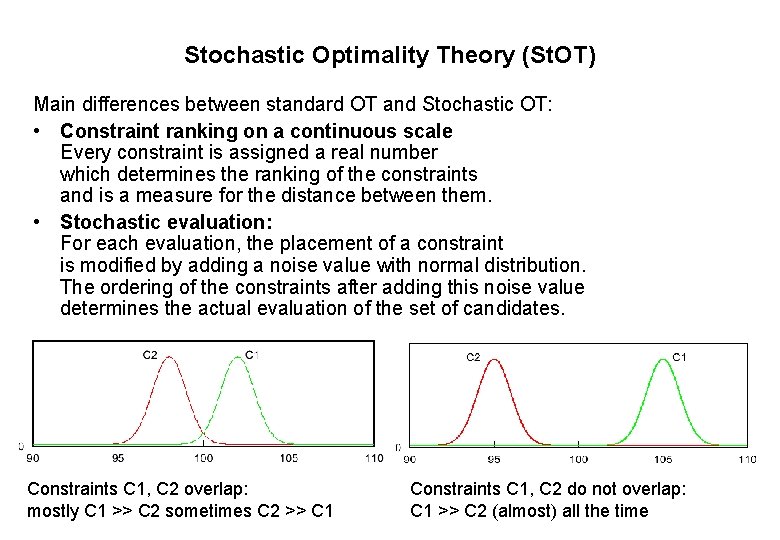

Stochastic Optimality Theory (St. OT) Main differences between standard OT and Stochastic OT: • Constraint ranking on a continuous scale Every constraint is assigned a real number which determines the ranking of the constraints and is a measure for the distance between them. • Stochastic evaluation: For each evaluation, the placement of a constraint is modified by adding a noise value with normal distribution. The ordering of the constraints after adding this noise value determines the actual evaluation of the set of candidates. Constraints C 1, C 2 overlap: mostly C 1 >> C 2 sometimes C 2 >> C 1 Constraints C 1, C 2 do not overlap: C 1 >> C 2 (almost) all the time

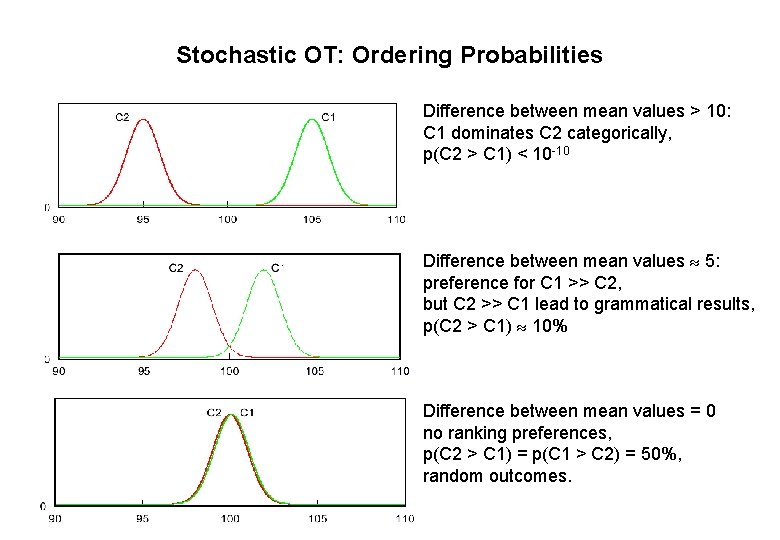

Stochastic OT: Ordering Probabilities Difference between mean values > 10: C 1 dominates C 2 categorically, p(C 2 > C 1) < 10 -10 Difference between mean values 5: preference for C 1 >> C 2, but C 2 >> C 1 lead to grammatical results, p(C 2 > C 1) 10% Difference between mean values = 0 no ranking preferences, p(C 2 > C 1) = p(C 1 > C 2) = 50%, random outcomes.

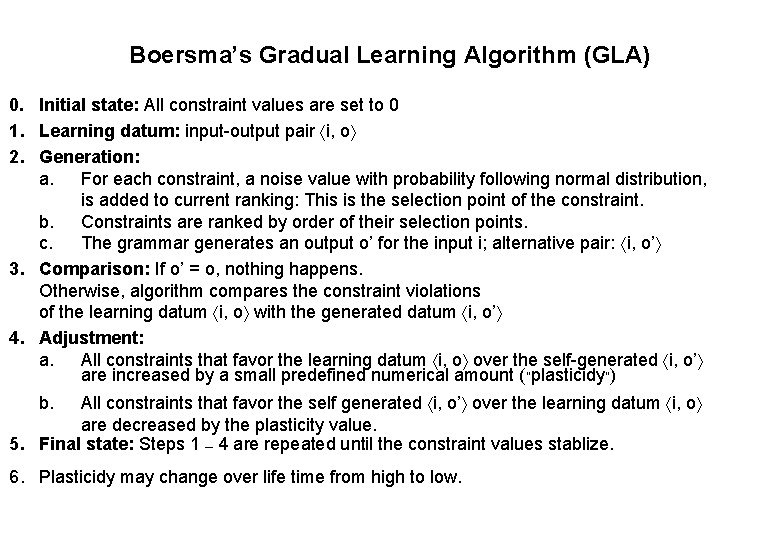

Statistical OT and Gradual Learning Boersma (1998), Boersma & Hayes (2001), in Linguistic Inquiry: Gradual Learning Algorithm (GLA) for learning constraint rankings (not for learning of possible candidates, GEN) • In phonology: GEN: pairs of phonological forms and phonetic interpretations: / /, [ ] • In semantics/pragmatics: GEN: pairs of syntactic/morphological forms and semantic/pragmatic interpretations: F, M

Boersma’s Gradual Learning Algorithm (GLA) 0. Initial state: All constraint values are set to 0 1. Learning datum: input-output pair i, o 2. Generation: a. For each constraint, a noise value with probability following normal distribution, is added to current ranking: This is the selection point of the constraint. b. Constraints are ranked by order of their selection points. c. The grammar generates an output o’ for the input i; alternative pair: i, o’ 3. Comparison: If o’ = o, nothing happens. Otherwise, algorithm compares the constraint violations of the learning datum i, o with the generated datum i, o’ 4. Adjustment: a. All constraints that favor the learning datum i, o over the self-generated i, o’ are increased by a small predefined numerical amount (“plasticidy”) All constraints that favor the self generated i, o’ over the learning datum i, o are decreased by the plasticity value. 5. Final state: Steps 1 – 4 are repeated until the constraint values stablize. b. 6. Plasticidy may change over life time from high to low.

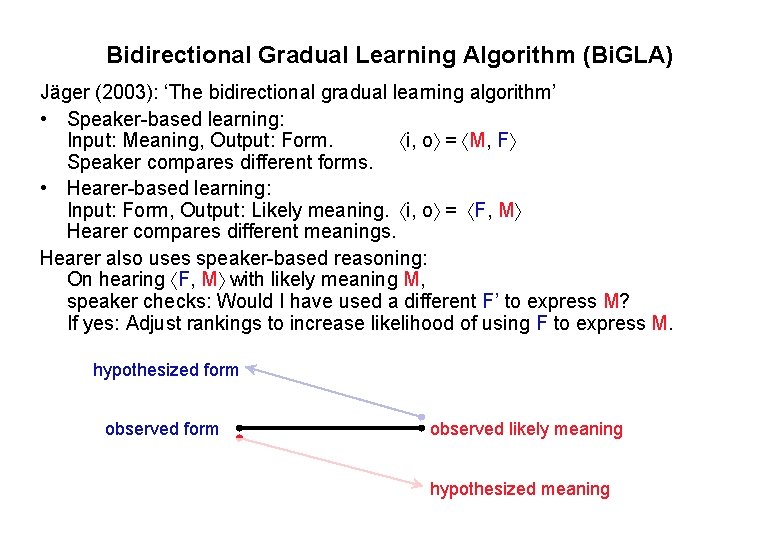

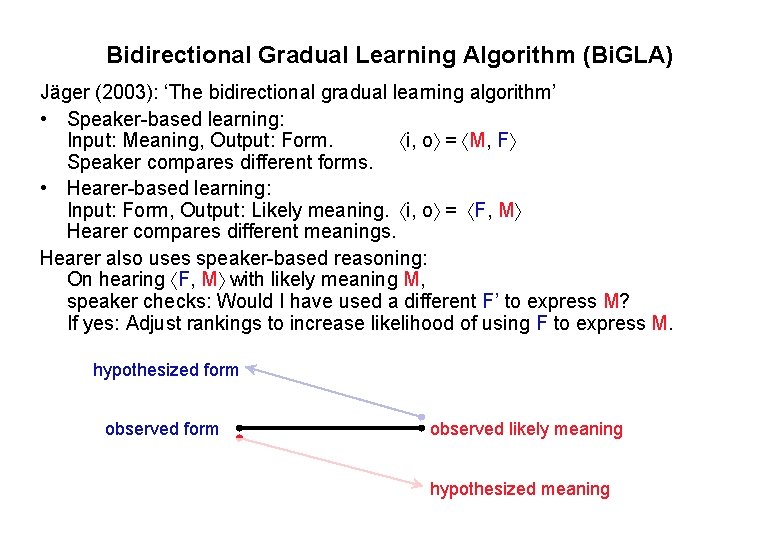

Bidirectional Gradual Learning Algorithm (Bi. GLA) Jäger (2003): ‘The bidirectional gradual learning algorithm’ • Speaker-based learning: Input: Meaning, Output: Form. i, o = M, F Speaker compares different forms. • Hearer-based learning: Input: Form, Output: Likely meaning. i, o = F, M Hearer compares different meanings. Hearer also uses speaker-based reasoning: On hearing F, M with likely meaning M, speaker checks: Would I have used a different F’ to express M? If yes: Adjust rankings to increase likelihood of using F to express M. hypothesized form observed likely meaning hypothesized meaning

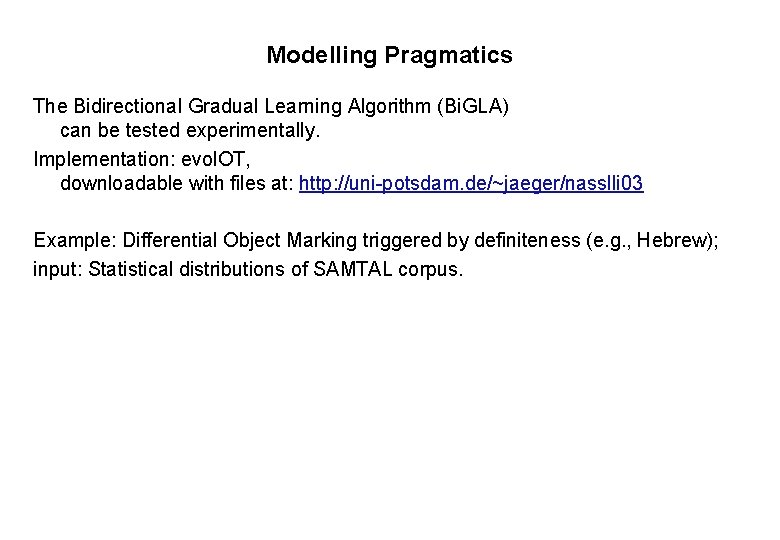

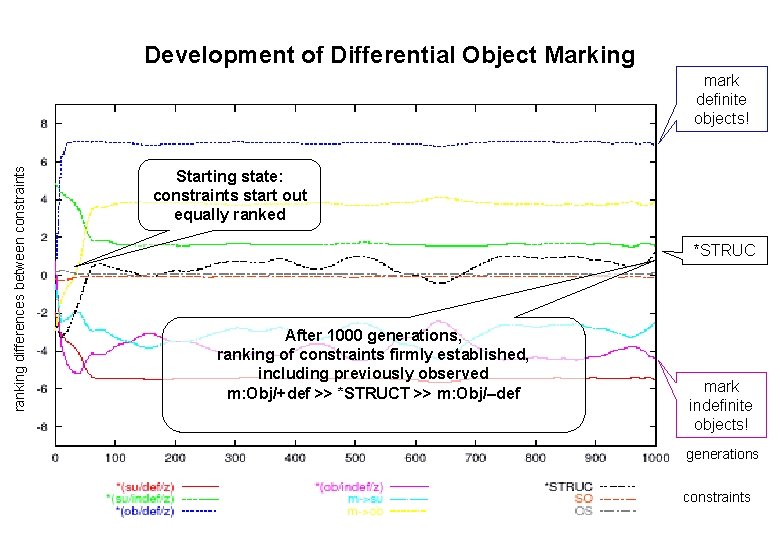

Modelling Pragmatics The Bidirectional Gradual Learning Algorithm (Bi. GLA) can be tested experimentally. Implementation: evol. OT, downloadable with files at: http: //uni-potsdam. de/~jaeger/nasslli 03 Example: Differential Object Marking triggered by definiteness (e. g. , Hebrew); input: Statistical distributions of SAMTAL corpus.

Development of Differential Object Marking ranking differences between constraints mark definite objects! Starting state: constraints start out equally ranked *STRUC After 1000 generations, ranking of constraints firmly established, including previously observed m: Obj/+def >> *STRUCT >> m: Obj/–def mark indefinite objects! generations constraints

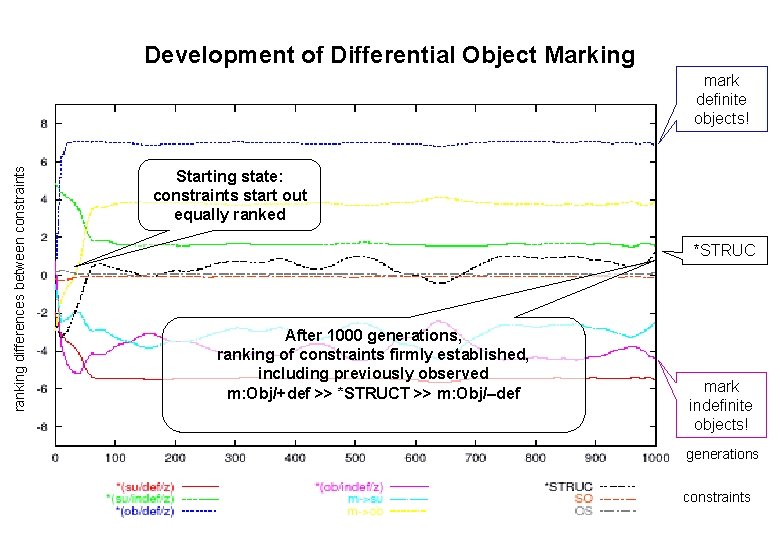

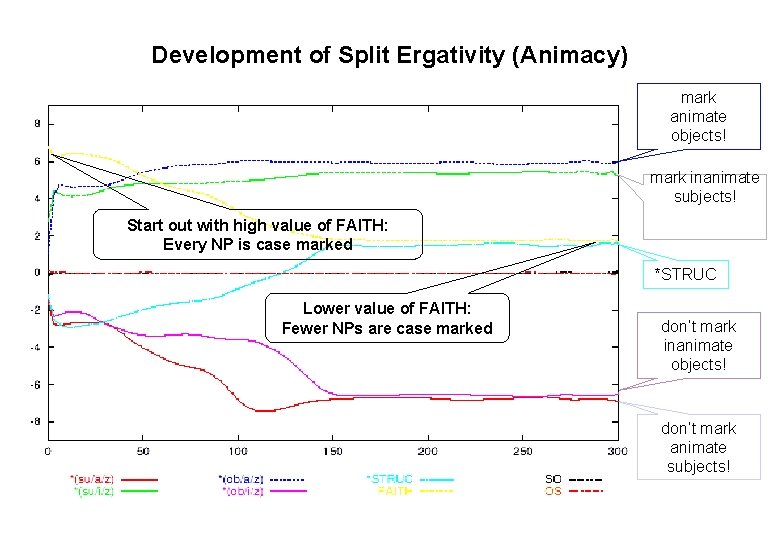

Development of Split Ergativity (Animacy) mark animate objects! mark inanimate subjects! Start out with high value of FAITH: Every NP is case marked *STRUC Lower value of FAITH: Fewer NPs are case marked don’t mark inanimate objects! don’t mark animate subjects!

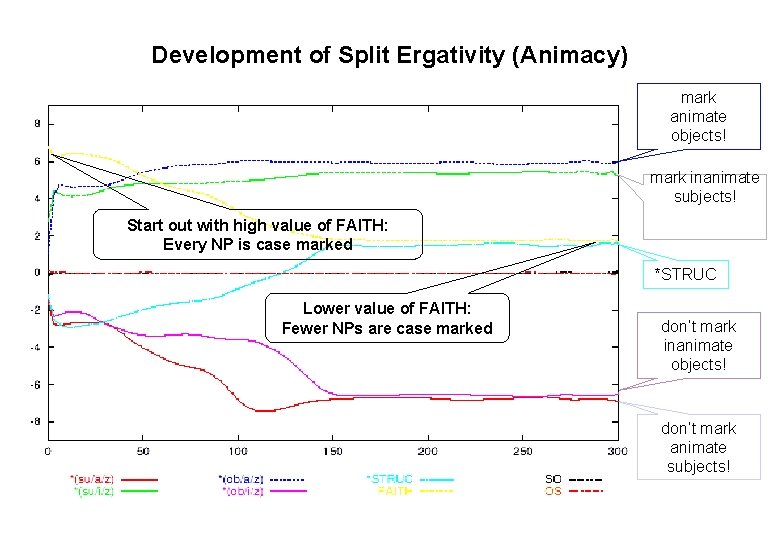

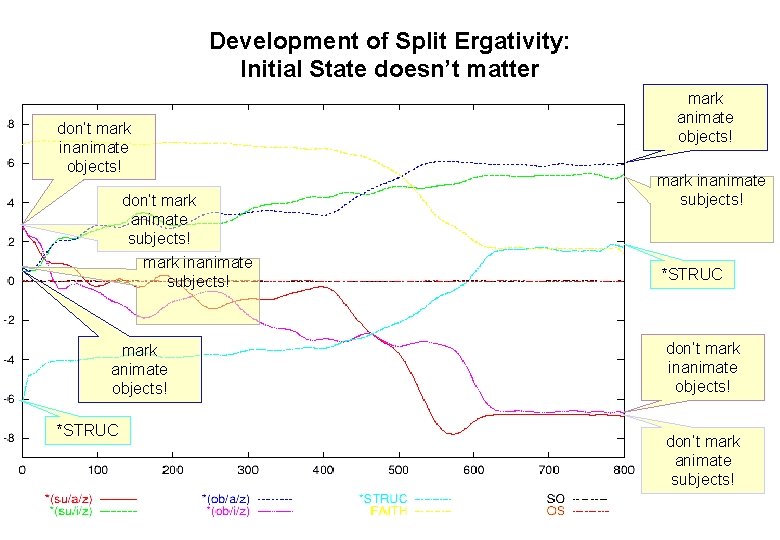

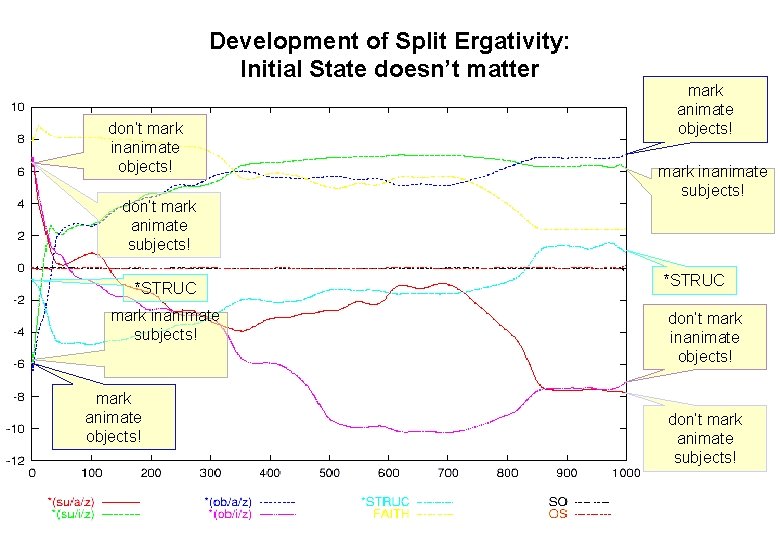

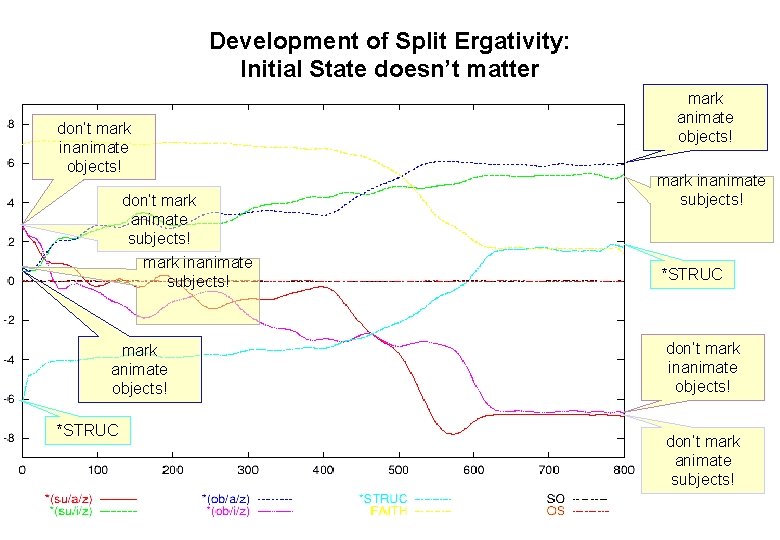

Development of Split Ergativity: Initial State doesn’t matter don’t mark inanimate objects! don’t mark animate subjects! mark inanimate subjects! mark animate objects! *STRUC mark animate objects! mark inanimate subjects! *STRUC don’t mark inanimate objects! don’t mark animate subjects!

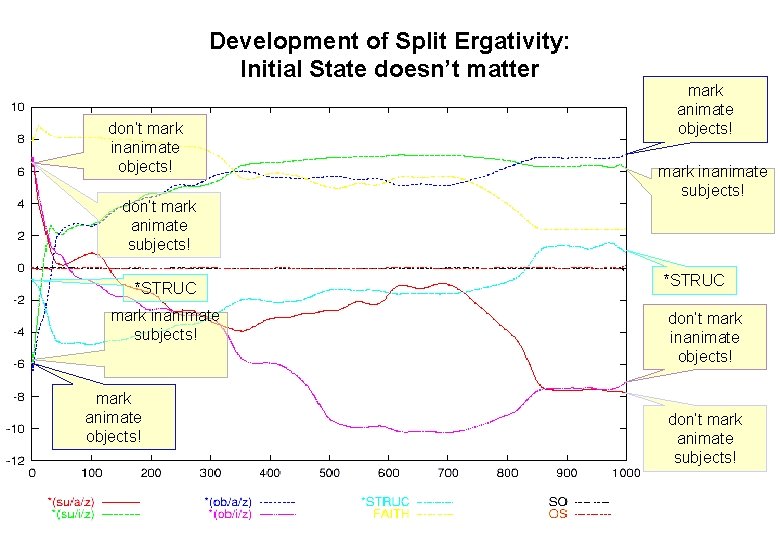

Development of Split Ergativity: Initial State doesn’t matter don’t mark inanimate objects! don’t mark animate subjects! *STRUC mark inanimate subjects! mark animate objects! mark inanimate subjects! *STRUC don’t mark inanimate objects! don’t mark animate subjects!

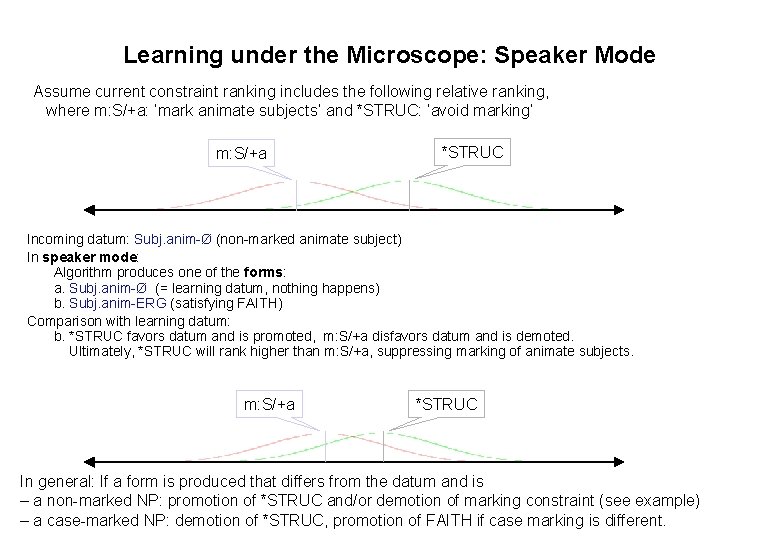

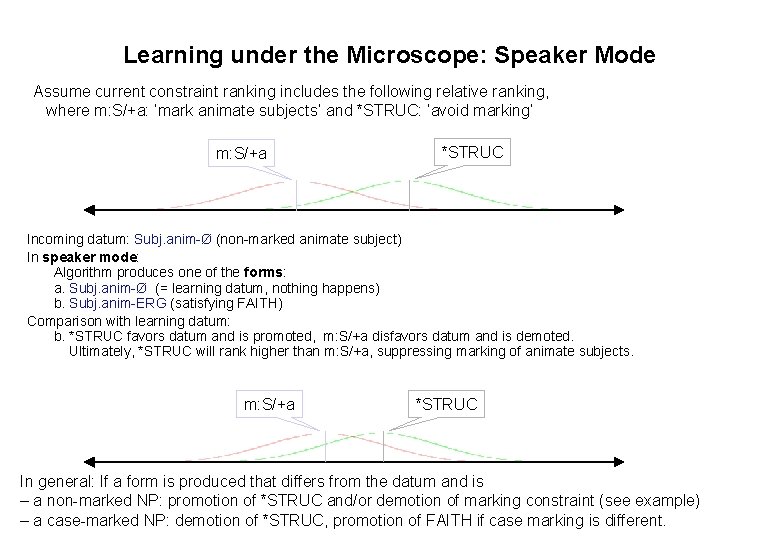

Learning under the Microscope: Speaker Mode Assume current constraint ranking includes the following relative ranking, where m: S/+a: ‘mark animate subjects’ and *STRUC: ‘avoid marking’ m: S/+a *STRUC Incoming datum: Subj. anim-Ø (non-marked animate subject) In speaker mode: Algorithm produces one of the forms: a. Subj. anim-Ø (= learning datum, nothing happens) b. Subj. anim-ERG (satisfying FAITH) Comparison with learning datum: b. *STRUC favors datum and is promoted, m: S/+a disfavors datum and is demoted. Ultimately, *STRUC will rank higher than m: S/+a, suppressing marking of animate subjects. m: S/+a *STRUC In general: If a form is produced that differs from the datum and is – a non-marked NP: promotion of *STRUC and/or demotion of marking constraint (see example) – a case-marked NP: demotion of *STRUC, promotion of FAITH if case marking is different.

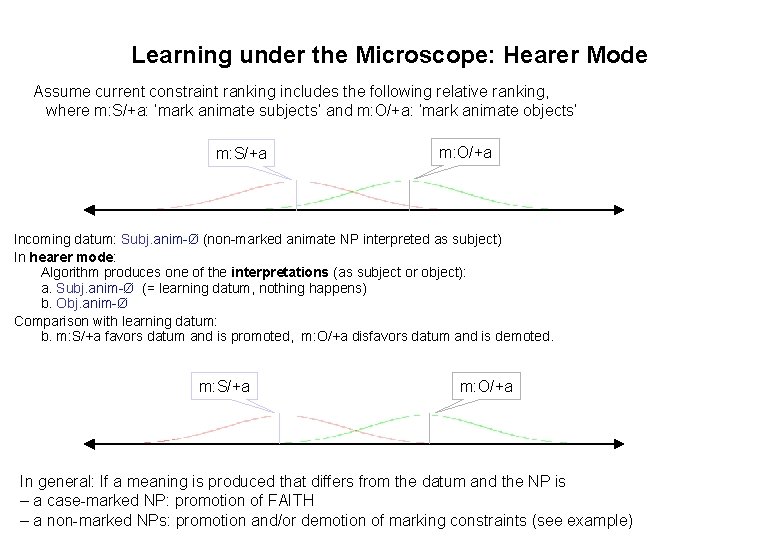

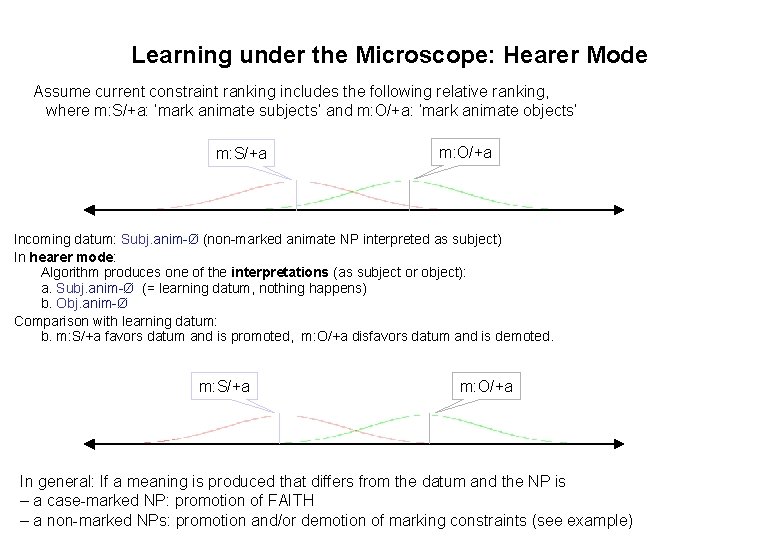

Learning under the Microscope: Hearer Mode Assume current constraint ranking includes the following relative ranking, where m: S/+a: ‘mark animate subjects’ and m: O/+a: ‘mark animate objects’ m: S/+a m: O/+a Incoming datum: Subj. anim-Ø (non-marked animate NP interpreted as subject) In hearer mode: Algorithm produces one of the interpretations (as subject or object): a. Subj. anim-Ø (= learning datum, nothing happens) b. Obj. anim-Ø Comparison with learning datum: b. m: S/+a favors datum and is promoted, m: O/+a disfavors datum and is demoted. m: S/+a m: O/+a In general: If a meaning is produced that differs from the datum and the NP is – a case-marked NP: promotion of FAITH – a non-marked NPs: promotion and/or demotion of marking constraints (see example)

Universitt wien

Universitt wien Universitt freiburg

Universitt freiburg Universitt

Universitt Harvard universitt

Harvard universitt Pragmatik

Pragmatik Stail pragmatik

Stail pragmatik Variabel sintaktik

Variabel sintaktik Pragmatiker definition

Pragmatiker definition Contoh tes pragmatik

Contoh tes pragmatik Lexikalisering

Lexikalisering Bilgi aktarmayı aksatan etkenler

Bilgi aktarmayı aksatan etkenler Sicherheitsakademie

Sicherheitsakademie Der gang vor die hunde kapitel zusammenfassung

Der gang vor die hunde kapitel zusammenfassung Www.bmi.gv.at

Www.bmi.gv.at Der erste tag der woche

Der erste tag der woche Der seele heimat ist der sinn

Der seele heimat ist der sinn Auf einem häuserblocke sitzt er breit

Auf einem häuserblocke sitzt er breit Der daumen pflückt die pflaumen

Der daumen pflückt die pflaumen Sorrowing old man painting

Sorrowing old man painting Steuerung der atmung

Steuerung der atmung Weltuntergangstheorie

Weltuntergangstheorie Gründer der modernen türkei

Gründer der modernen türkei Geschichte frosch skorpion

Geschichte frosch skorpion Aufbau einer burg mittelalter

Aufbau einer burg mittelalter Der gegenstand der psychologie

Der gegenstand der psychologie Garagengesetz nrw

Garagengesetz nrw Qualifikationsplan

Qualifikationsplan Antitetisk tolkning

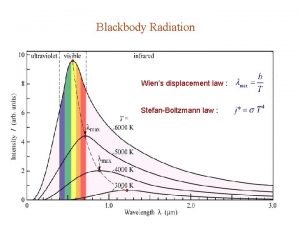

Antitetisk tolkning Boltzman law

Boltzman law Boku wien

Boku wien Maronistand wien

Maronistand wien