Operations Management Chapter 15 ShortTerm Scheduling Power Point

- Slides: 77

Operations Management Chapter 15 – Short-Term Scheduling Power. Point presentation to accompany Heizer/Render Principles of Operations Management, 6 e Operations Management, 8 e © 2006 Prentice Hall, Inc. © 2006 Prentice 15 –

Outline þ Global Company Profile: Delta Airlines þ The Strategic Importance Of Short. Term Scheduling þ Scheduling Issues þ Forward and Backward Scheduling þ Scheduling Criteria © 2006 Prentice Hall, Inc. 15 –

Outline – Continued þ Scheduling Process-Focused Facilities þ Loading Jobs þ Input-Output Control þ Gantt Charts þ Assignment Method © 2006 Prentice Hall, Inc. 15 –

Outline – Continued þ Sequencing Jobs þ Priority Rules for Dispatching Jobs þ Critical Ratio þ Sequencing N Jobs on Two Machines: Johnson’s Rule þ Limitations Of Rule-Based Dispatching Systems þ Finite Capacity Scheduling (FCS) © 2006 Prentice Hall, Inc. 15 –

Outline – Continued þ Theory Of Constraints þ Bottlenecks þ Drum, Buffer, Rope þ Scheduling Repetitive Facilities þ Scheduling Service Employees with Cyclical Scheduling © 2006 Prentice Hall, Inc. 15 –

Learning Objectives When you complete this chapter, you should be able to: Identify or Define: þ Gantt charts þ Assignment method þ Sequencing rules þ Johnson’s rule þ Bottlenecks © 2006 Prentice Hall, Inc. 15 –

Learning Objectives When you complete this chapter, you should be able to: Describe or Explain: þ Scheduling þ Sequencing þ Shop loading þ Theory of constraints © 2006 Prentice Hall, Inc. 15 –

Delta Airlines þ About 10% of Delta’s flights are disrupted per year, half because of weather þ Cost is $440 million in lost revenue, overtime pay, food and lodging vouchers þ The $33 million Operations Control Center adjusts to changes and keeps flights flowing þ Saves Delta $35 million per year © 2006 Prentice Hall, Inc. 15 –

Strategic Importance of Short-Term Scheduling þ Effective and efficient scheduling can be a competitive advantage þ Faster movement of goods through a facility means better use of assets and lower costs þ Additional capacity resulting from faster throughput improves customer service through faster delivery þ Good schedules result in more reliable deliveries © 2006 Prentice Hall, Inc. 15 –

Scheduling Issues þ Scheduling deals with the timing of operations þ The task is the allocation and prioritization of demand þ Significant issues are þ The type of scheduling, forward or backward þ The criteria for priorities © 2006 Prentice Hall, Inc. 15 –

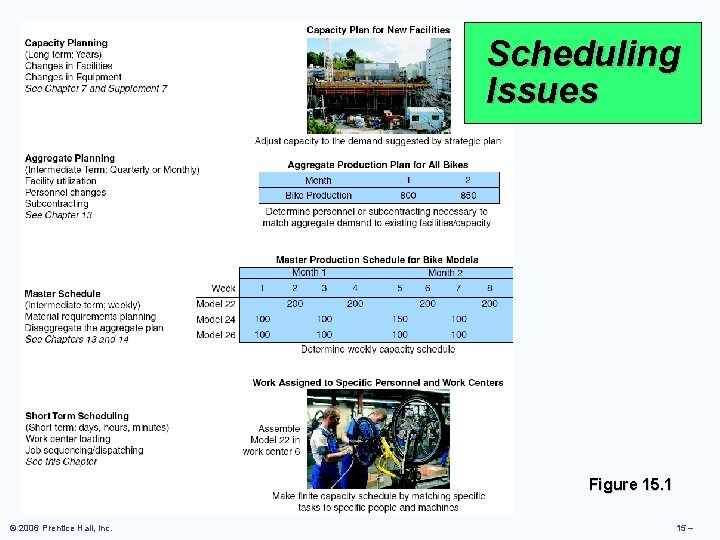

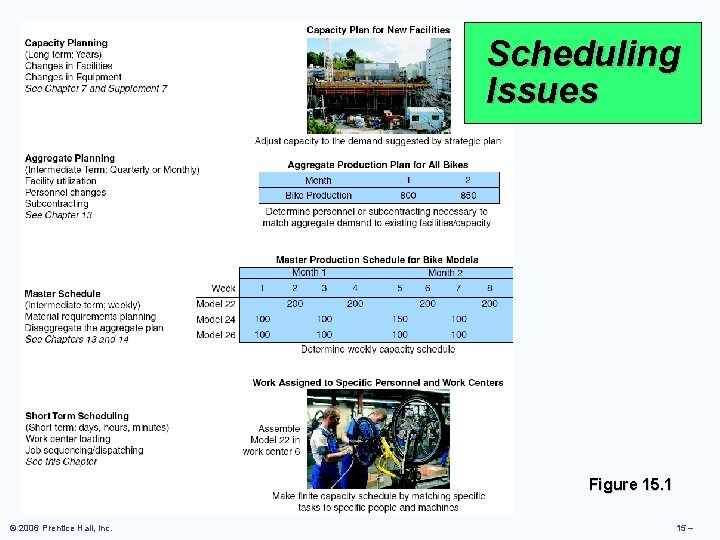

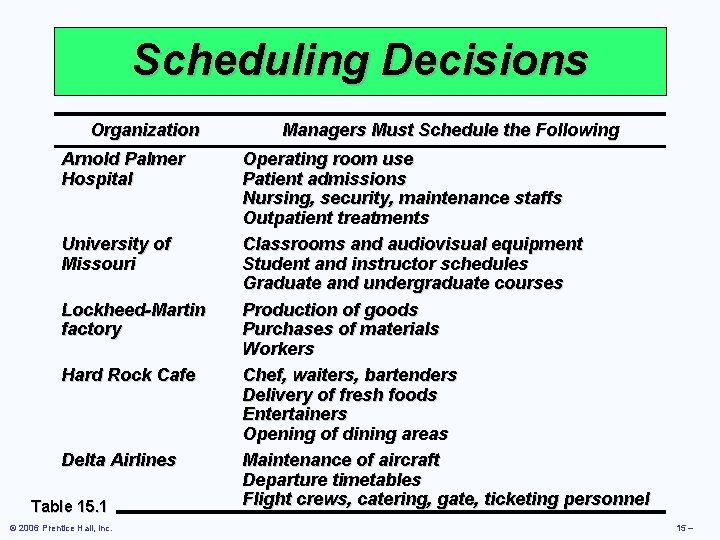

Scheduling Issues Figure 15. 1 © 2006 Prentice Hall, Inc. 15 –

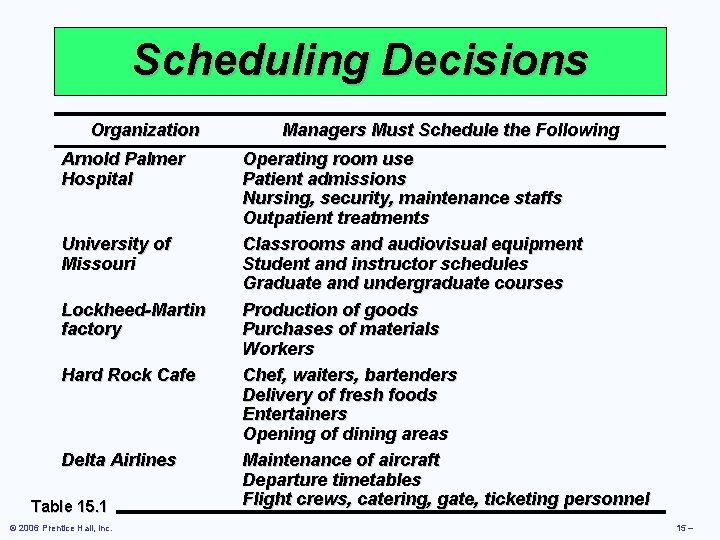

Scheduling Decisions Organization Arnold Palmer Hospital University of Missouri Lockheed-Martin factory Hard Rock Cafe Delta Airlines Table 15. 1 © 2006 Prentice Hall, Inc. Managers Must Schedule the Following Operating room use Patient admissions Nursing, security, maintenance staffs Outpatient treatments Classrooms and audiovisual equipment Student and instructor schedules Graduate and undergraduate courses Production of goods Purchases of materials Workers Chef, waiters, bartenders Delivery of fresh foods Entertainers Opening of dining areas Maintenance of aircraft Departure timetables Flight crews, catering, gate, ticketing personnel 15 –

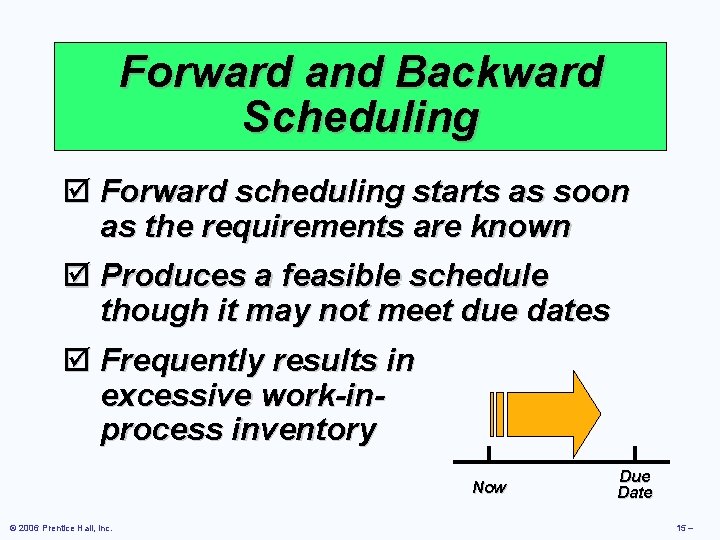

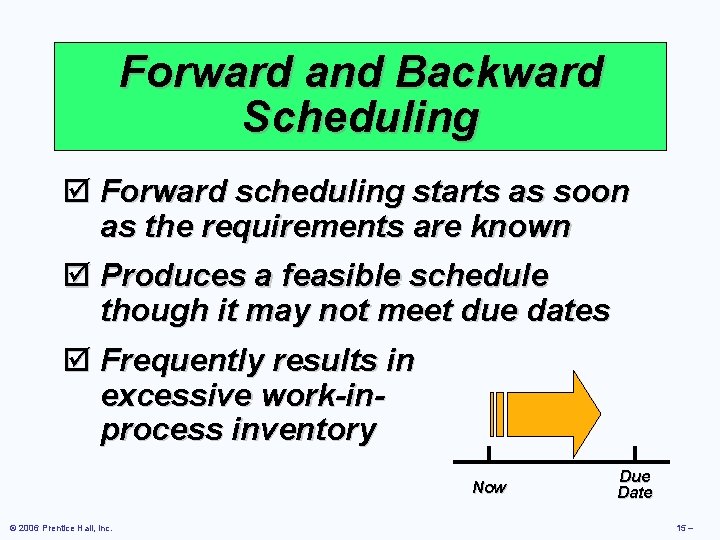

Forward and Backward Scheduling þ Forward scheduling starts as soon as the requirements are known þ Produces a feasible schedule though it may not meet due dates þ Frequently results in excessive work-inprocess inventory Now © 2006 Prentice Hall, Inc. Due Date 15 –

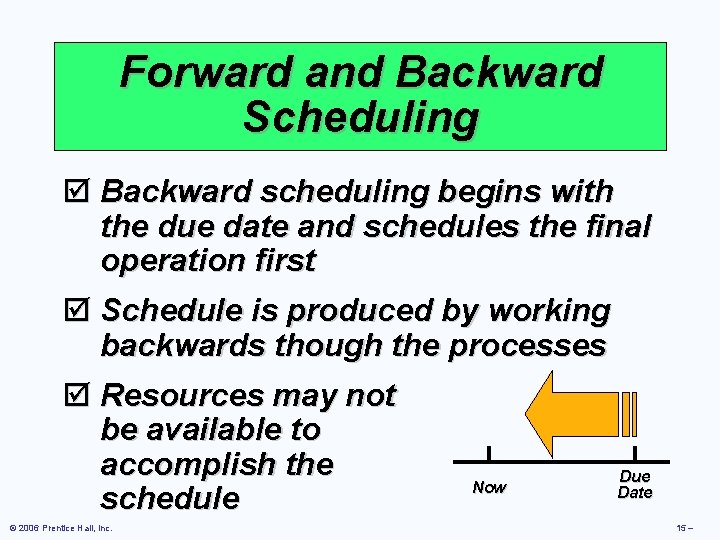

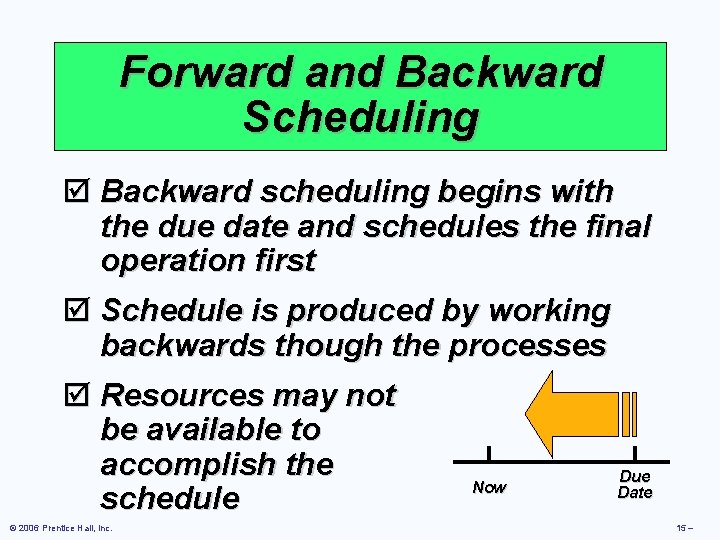

Forward and Backward Scheduling þ Backward scheduling begins with the due date and schedules the final operation first þ Schedule is produced by working backwards though the processes þ Resources may not be available to accomplish the Due Now Date schedule © 2006 Prentice Hall, Inc. 15 –

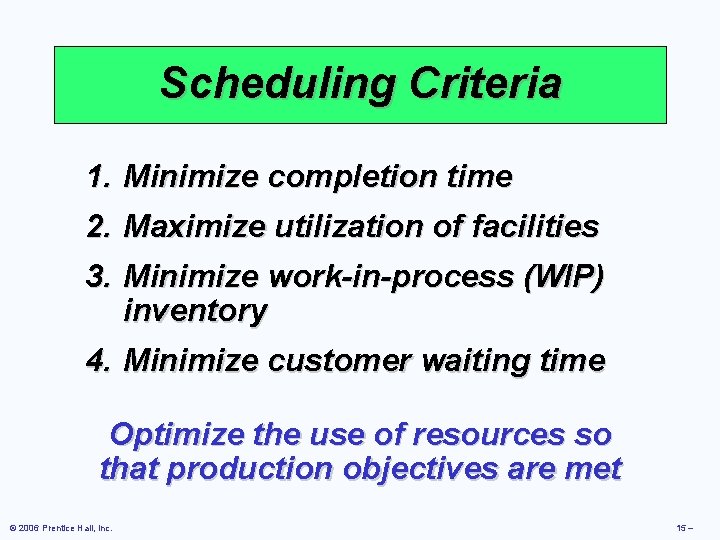

Scheduling Criteria 1. Minimize completion time 2. Maximize utilization of facilities 3. Minimize work-in-process (WIP) inventory 4. Minimize customer waiting time Optimize the use of resources so that production objectives are met © 2006 Prentice Hall, Inc. 15 –

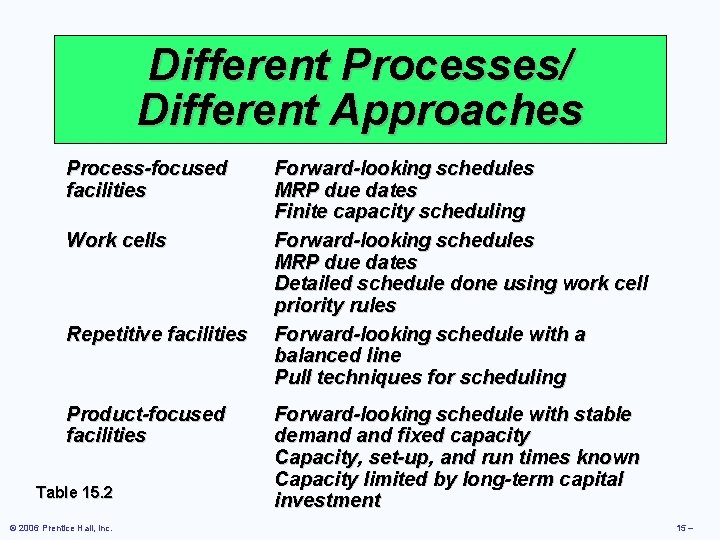

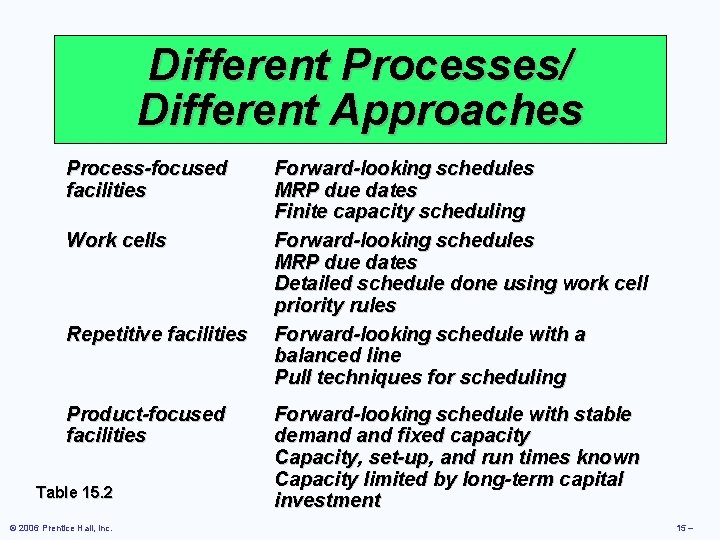

Different Processes/ Different Approaches Process-focused facilities Work cells Repetitive facilities Product-focused facilities Table 15. 2 © 2006 Prentice Hall, Inc. Forward-looking schedules MRP due dates Finite capacity scheduling Forward-looking schedules MRP due dates Detailed schedule done using work cell priority rules Forward-looking schedule with a balanced line Pull techniques for scheduling Forward-looking schedule with stable demand fixed capacity Capacity, set-up, and run times known Capacity limited by long-term capital investment 15 –

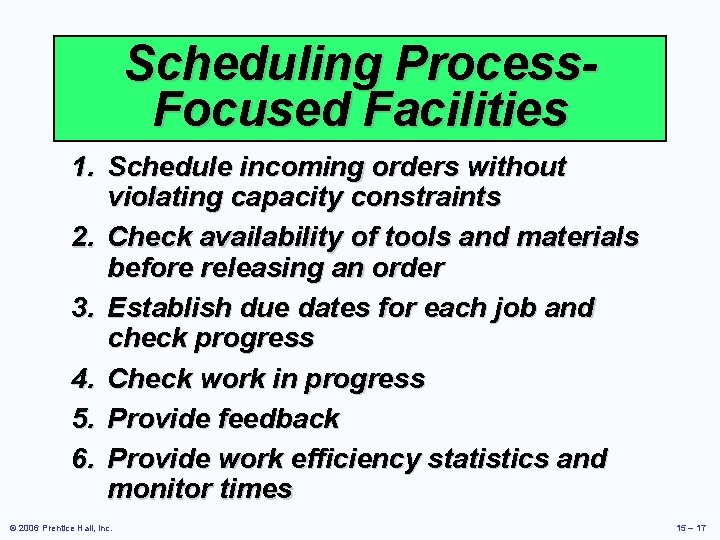

Scheduling Process. Focused Facilities 1. Schedule incoming orders without violating capacity constraints 2. Check availability of tools and materials before releasing an order 3. Establish due dates for each job and check progress 4. Check work in progress 5. Provide feedback 6. Provide work efficiency statistics and monitor times © 2006 Prentice Hall, Inc. 15 – 17

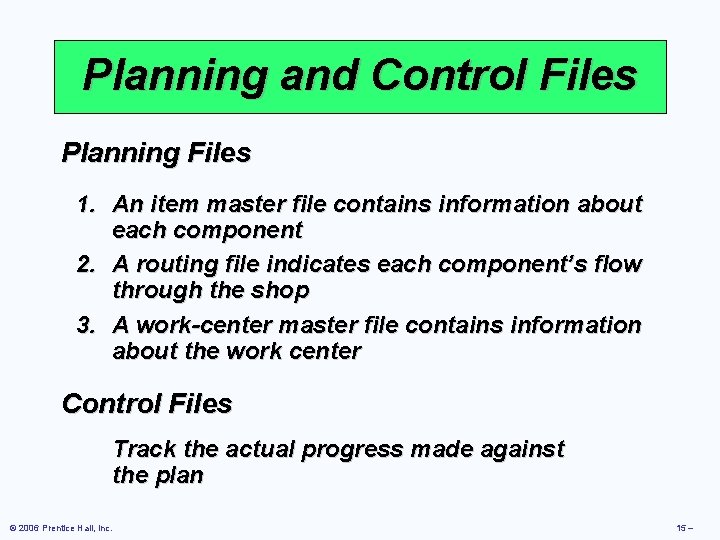

Planning and Control Files Planning Files 1. An item master file contains information about each component 2. A routing file indicates each component’s flow through the shop 3. A work-center master file contains information about the work center Control Files Track the actual progress made against the plan © 2006 Prentice Hall, Inc. 15 –

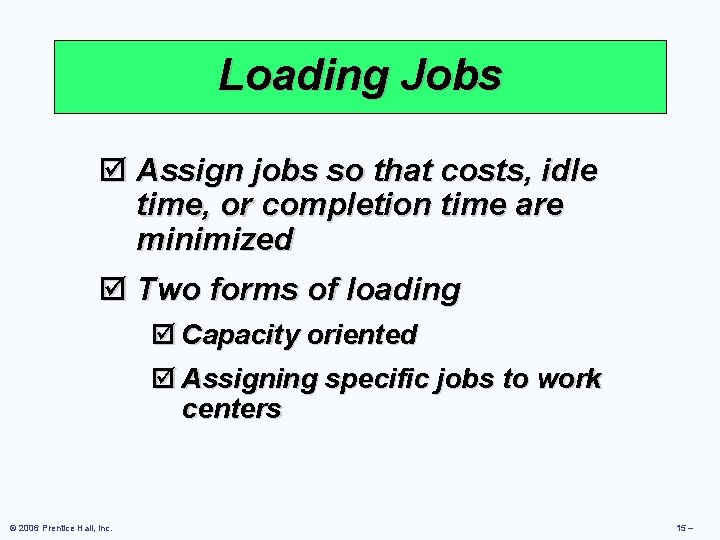

Loading Jobs þ Assign jobs so that costs, idle time, or completion time are minimized þ Two forms of loading þ Capacity oriented þ Assigning specific jobs to work centers © 2006 Prentice Hall, Inc. 15 –

Input-Output Control þ Identifies overloading and underloading conditions þ Prompts managerial action to resolve scheduling problems þ Can be maintained using Con. WIP cards that control the scheduling of batches © 2006 Prentice Hall, Inc. 15 –

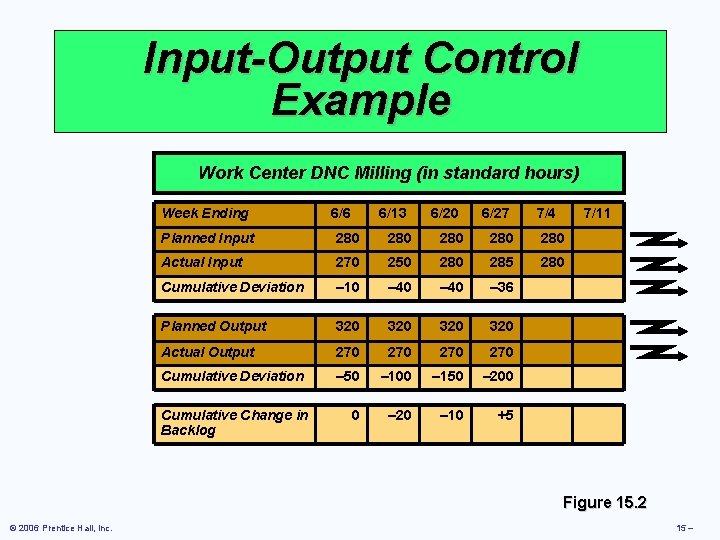

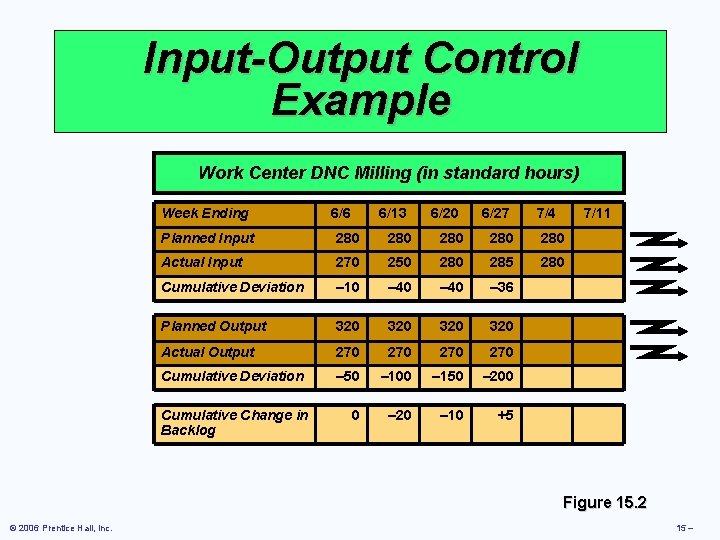

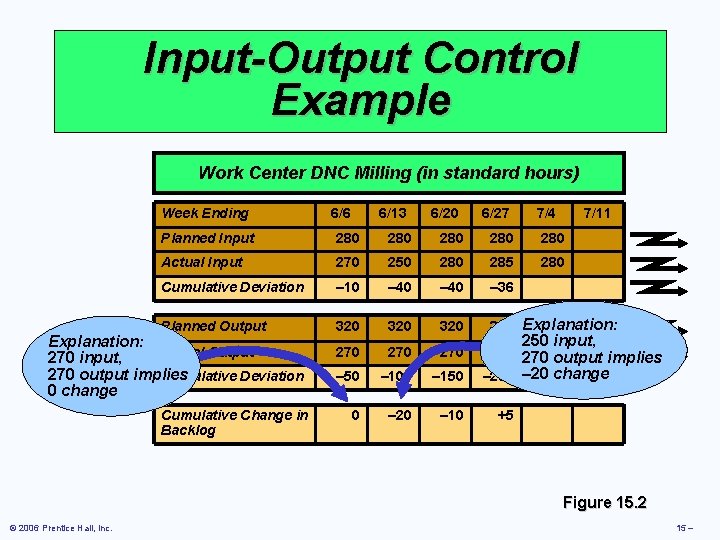

Input-Output Control Example Work Center DNC Milling (in standard hours) Week Ending 6/6 6/13 6/20 6/27 7/4 7/11 Planned Input 280 280 280 Actual Input 270 250 285 280 Cumulative Deviation – 10 – 40 – 36 Planned Output 320 320 Actual Output 270 270 Cumulative Deviation – 50 – 100 – 150 – 200 0 – 20 – 10 +5 Cumulative Change in Backlog Figure 15. 2 © 2006 Prentice Hall, Inc. 15 –

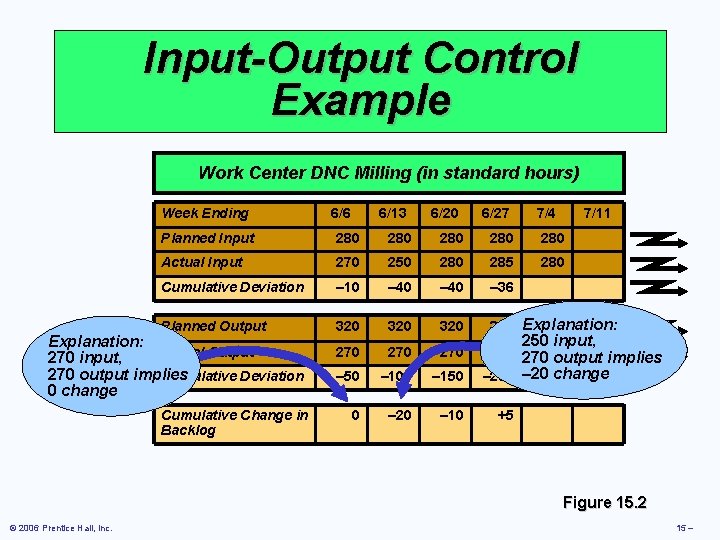

Input-Output Control Example Work Center DNC Milling (in standard hours) Week Ending 6/6 6/13 6/20 6/27 7/4 7/11 Planned Input 280 280 280 Actual Input 270 250 285 280 Cumulative Deviation – 10 – 40 – 36 Planned Output 320 320 Explanation: 270 270 – 50 – 100 – 150 0 – 20 – 10 Explanation: Actual Output 270 input, 270 output implies Cumulative Deviation 0 change Cumulative Change in Backlog 250 input, 270 output implies – 200 – 20 change +5 Figure 15. 2 © 2006 Prentice Hall, Inc. 15 –

Input-Output Control Example Options available to operations personnel include: 1. Correcting performances 2. Increasing capacity 3. Increasing or reducing input to the work center © 2006 Prentice Hall, Inc. 15 –

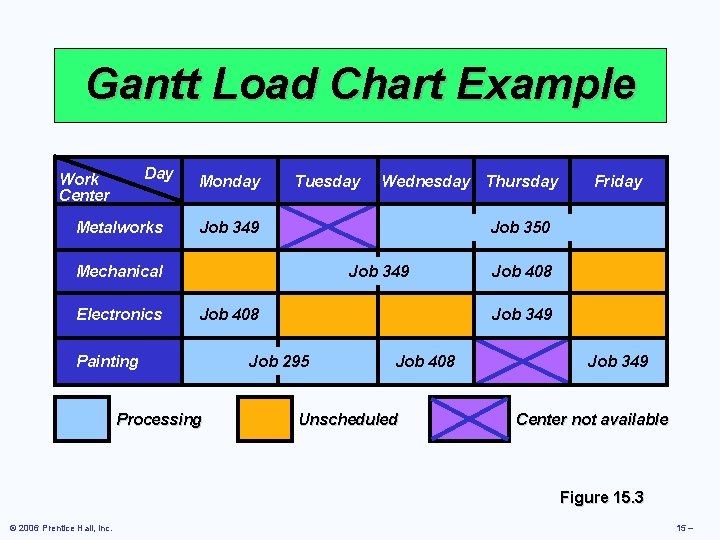

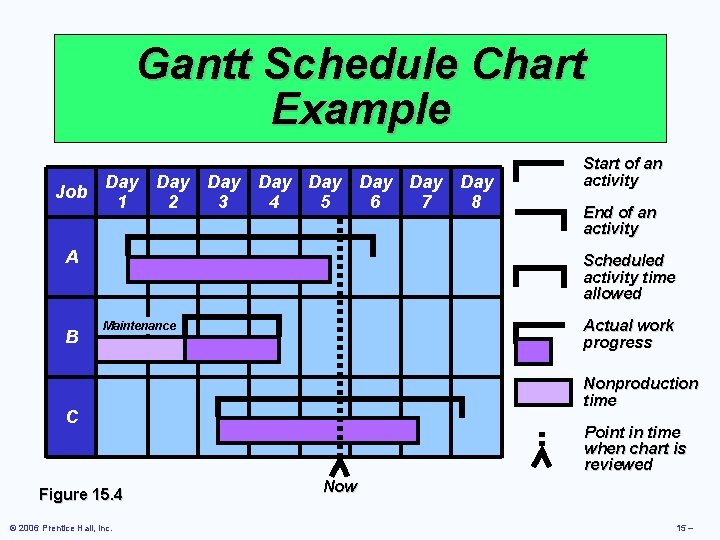

Gantt Charts þ Load chart shows the loading and idle times of departments, machines, or facilities þ Displays relative workloads over time þ Schedule chart monitors jobs in process þ All Gantt charts need to be updated frequently © 2006 Prentice Hall, Inc. 15 –

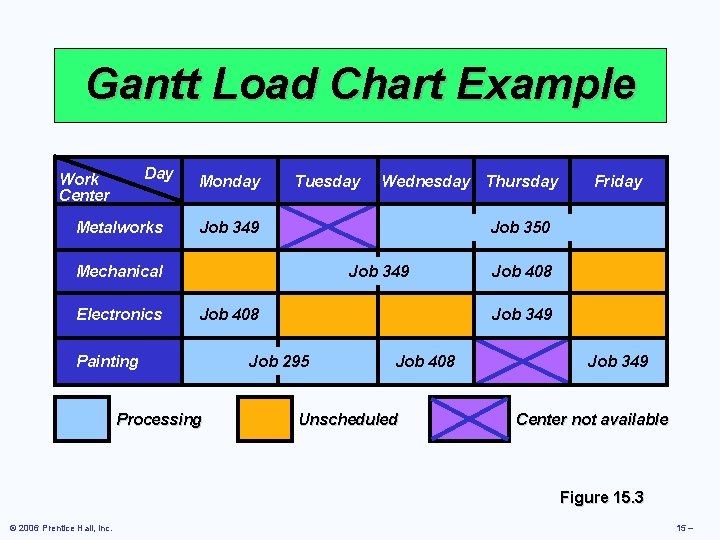

Gantt Load Chart Example Day Work Center Metalworks Monday Tuesday Job 349 Job 408 Painting Processing Friday Job 350 Mechanical Electronics Wednesday Thursday Job 408 Job 349 Job 295 Job 408 Unscheduled Job 349 Center not available Figure 15. 3 © 2006 Prentice Hall, Inc. 15 –

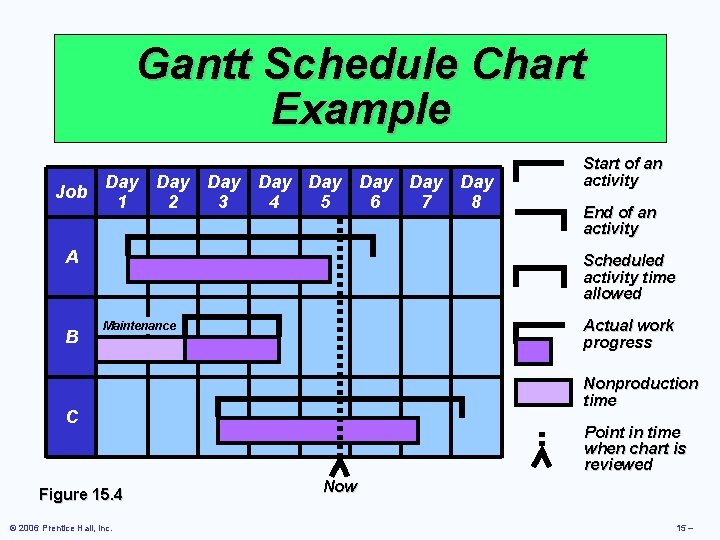

Gantt Schedule Chart Example Job Day Day 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 A B Start of an activity End of an activity Scheduled activity time allowed Actual work progress Maintenance Nonproduction time C Figure 15. 4 © 2006 Prentice Hall, Inc. Point in time when chart is reviewed Now 15 –

Assignment Method þ A special class of linear programming models that assign tasks or jobs to resources þ Objective is to minimize cost or time þ Only one job (or worker) is assigned to one machine (or project) © 2006 Prentice Hall, Inc. 15 –

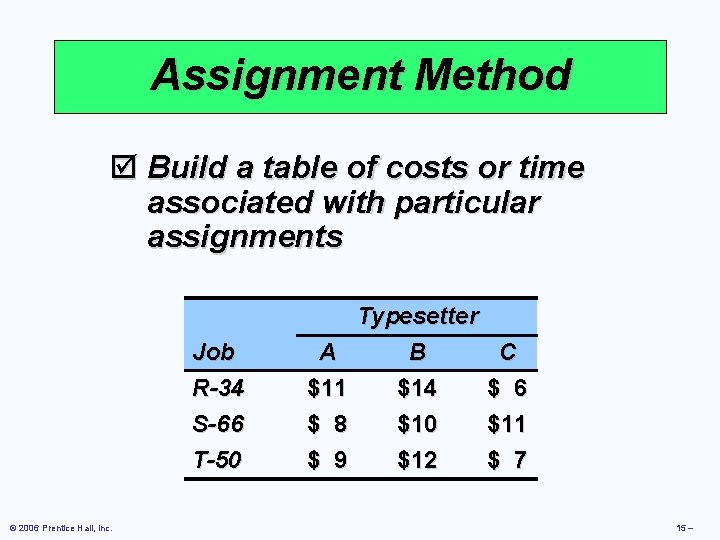

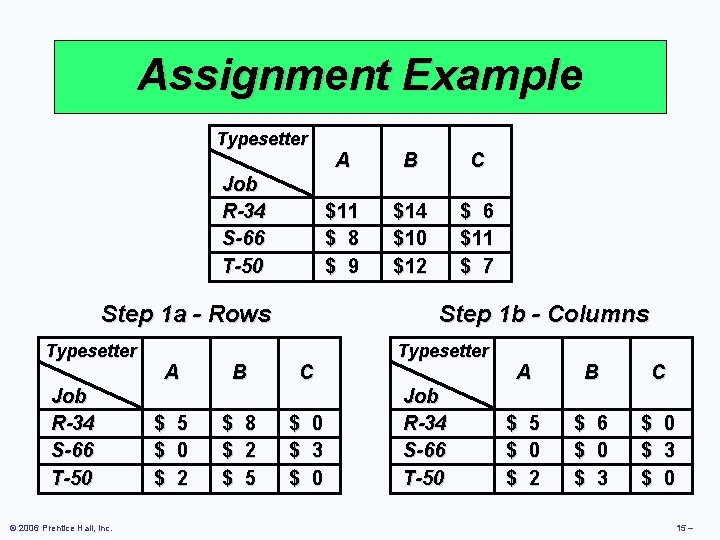

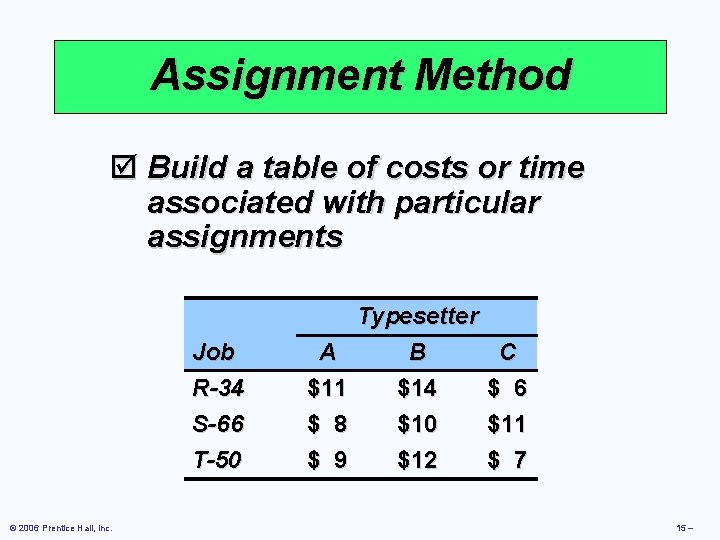

Assignment Method þ Build a table of costs or time associated with particular assignments Job R-34 S-66 T-50 © 2006 Prentice Hall, Inc. A $11 $ 8 $ 9 Typesetter B $14 $10 $12 C $ 6 $11 $ 7 15 –

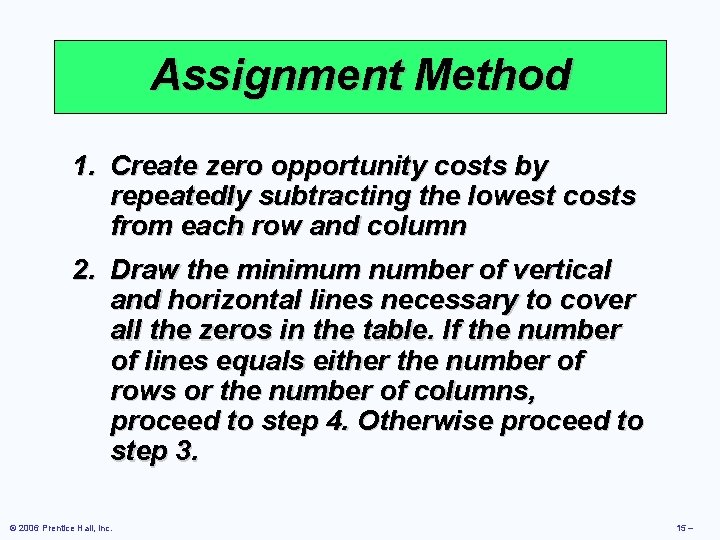

Assignment Method 1. Create zero opportunity costs by repeatedly subtracting the lowest costs from each row and column 2. Draw the minimum number of vertical and horizontal lines necessary to cover all the zeros in the table. If the number of lines equals either the number of rows or the number of columns, proceed to step 4. Otherwise proceed to step 3. © 2006 Prentice Hall, Inc. 15 –

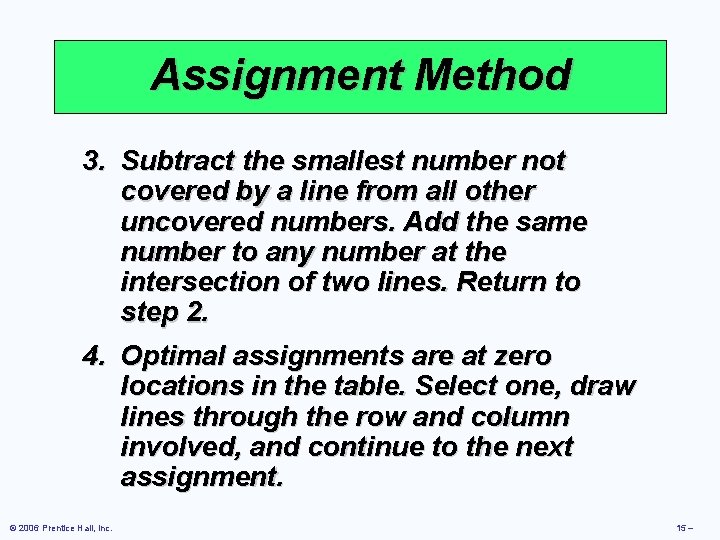

Assignment Method 3. Subtract the smallest number not covered by a line from all other uncovered numbers. Add the same number to any number at the intersection of two lines. Return to step 2. 4. Optimal assignments are at zero locations in the table. Select one, draw lines through the row and column involved, and continue to the next assignment. © 2006 Prentice Hall, Inc. 15 –

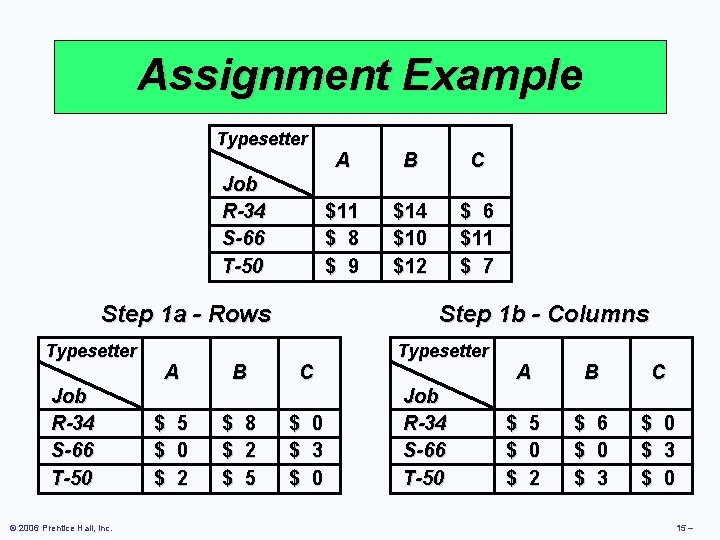

Assignment Example Typesetter Job R-34 S-66 T-50 Step 1 a - Rows Typesetter Job R-34 S-66 T-50 © 2006 Prentice Hall, Inc. A $ 5 $ 0 $ 2 B $ 8 $ 2 $ 5 A B C $11 $ 8 $ 9 $14 $10 $12 $ 6 $11 $ 7 Step 1 b - Columns C $ 0 $ 3 $ 0 Typesetter Job R-34 S-66 T-50 A B C $ 5 $ 0 $ 2 $ 6 $ 0 $ 3 $ 0 15 –

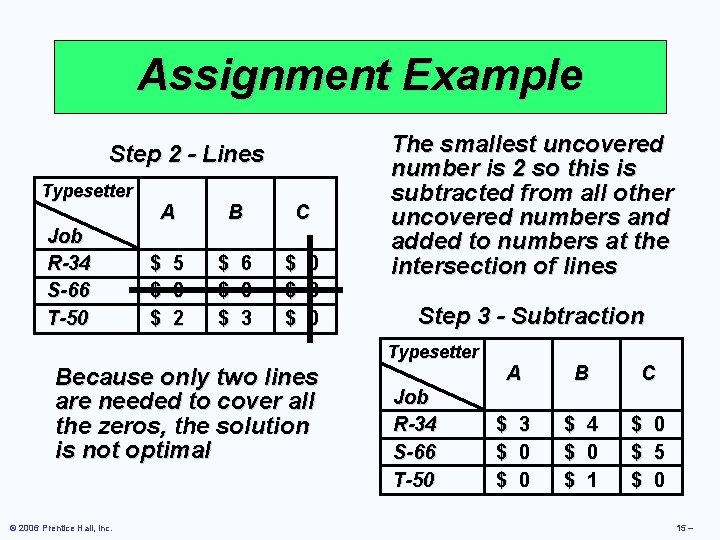

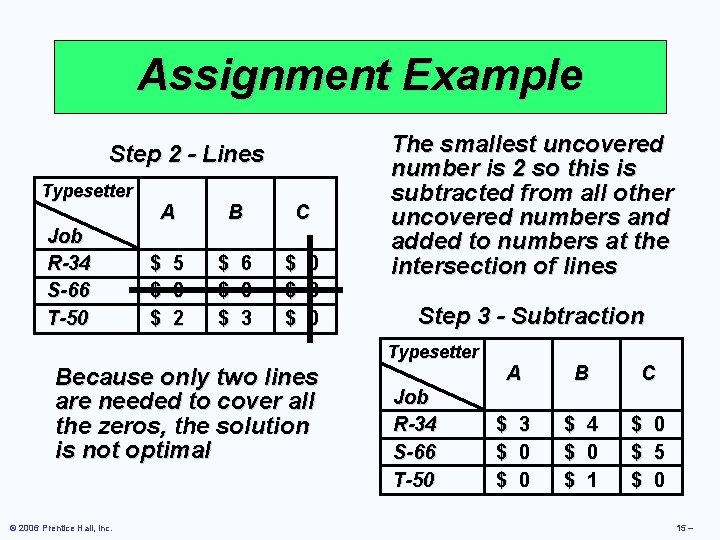

Assignment Example Step 2 - Lines Typesetter Job R-34 S-66 T-50 A B C $ 5 $ 0 $ 2 $ 6 $ 0 $ 3 $ 0 Because only two lines are needed to cover all the zeros, the solution is not optimal © 2006 Prentice Hall, Inc. The smallest uncovered number is 2 so this is subtracted from all other uncovered numbers and added to numbers at the intersection of lines Step 3 - Subtraction Typesetter Job R-34 S-66 T-50 A $ $ $ 3 0 0 B $ $ $ 4 0 1 C $ $ $ 0 5 0 15 –

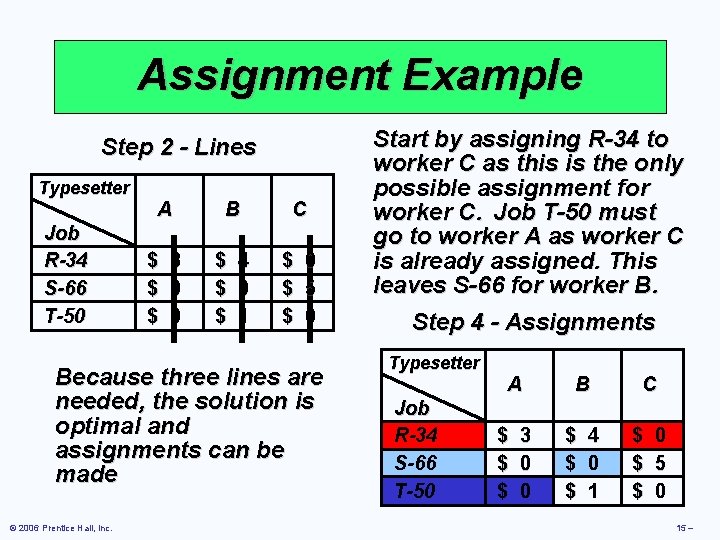

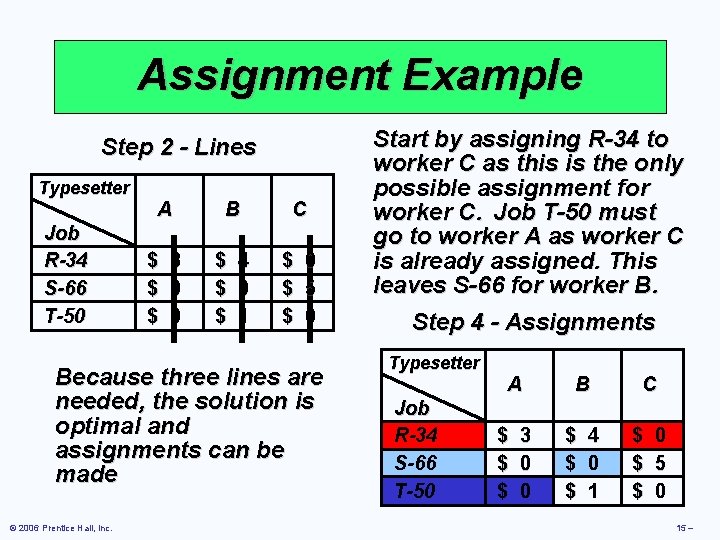

Assignment Example Step 2 - Lines Typesetter Job R-34 S-66 T-50 A $ $ $ 3 0 0 B $ $ $ 4 0 1 C $ $ $ 0 5 0 Because three lines are needed, the solution is optimal and assignments can be made © 2006 Prentice Hall, Inc. Start by assigning R-34 to worker C as this is the only possible assignment for worker C. Job T-50 must go to worker A as worker C is already assigned. This leaves S-66 for worker B. Step 4 - Assignments Typesetter Job R-34 S-66 T-50 A B C $ 3 $ 0 $ 4 $ 0 $ 1 $ 0 $ 5 $ 0 15 –

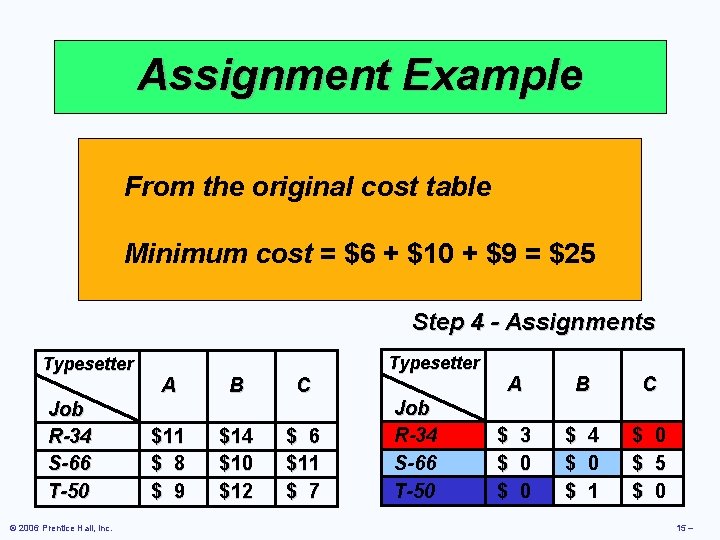

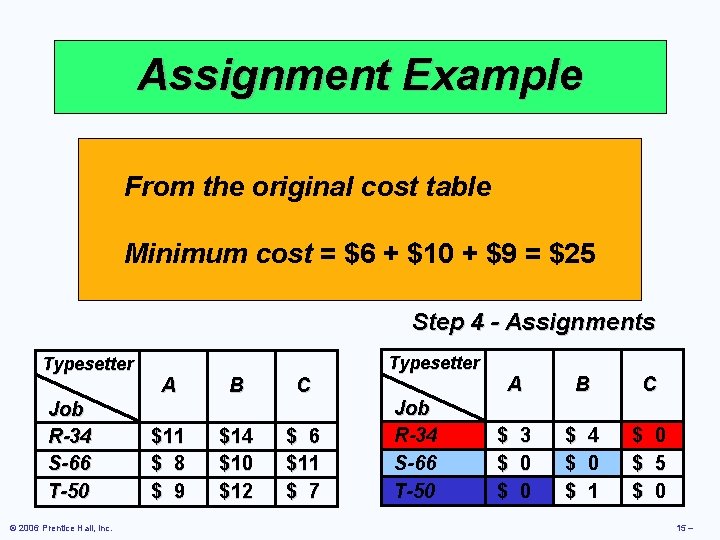

Assignment Example From the original cost table Minimum cost = $6 + $10 + $9 = $25 Step 4 - Assignments Typesetter Job R-34 S-66 T-50 © 2006 Prentice Hall, Inc. A $11 $ 8 $ 9 B $14 $10 $12 C $ 6 $11 $ 7 Typesetter Job R-34 S-66 T-50 A B C $ 3 $ 0 $ 4 $ 0 $ 1 $ 0 $ 5 $ 0 15 –

Sequencing Jobs þ Specifies the order in which jobs should be performed at work centers þ Priority rules are used to dispatch or sequence jobs þ FCFS: First come, first served þ SPT: Shortest processing time þ EDD: Earliest due date þ LPT: Longest processing time © 2006 Prentice Hall, Inc. 15 –

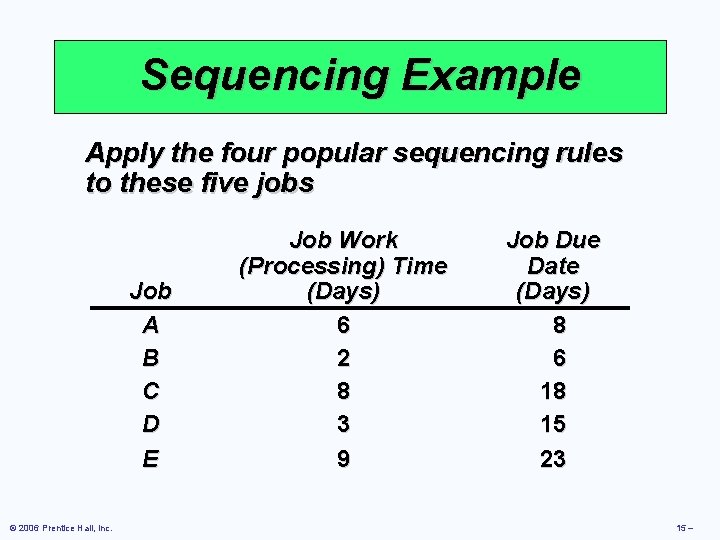

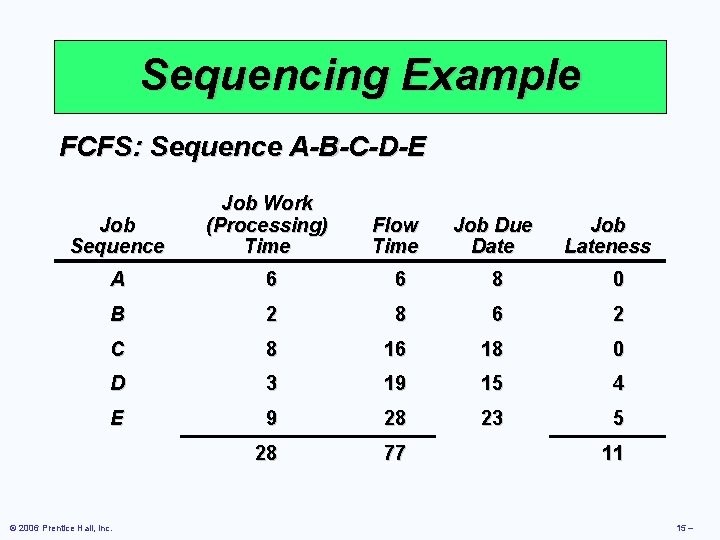

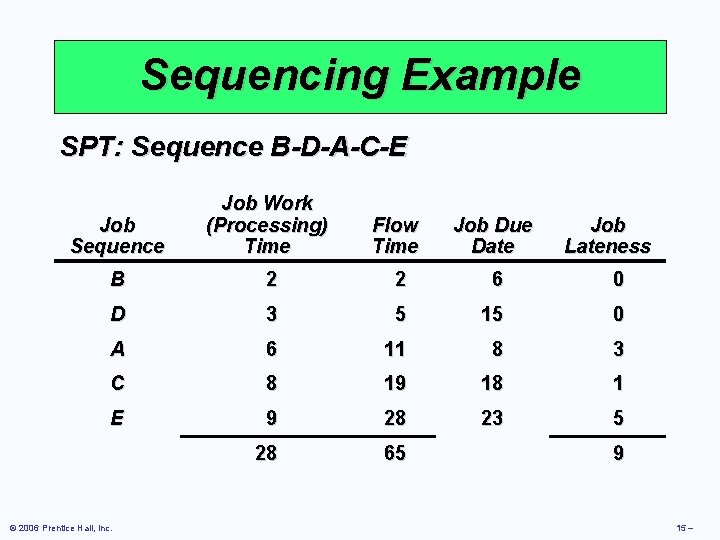

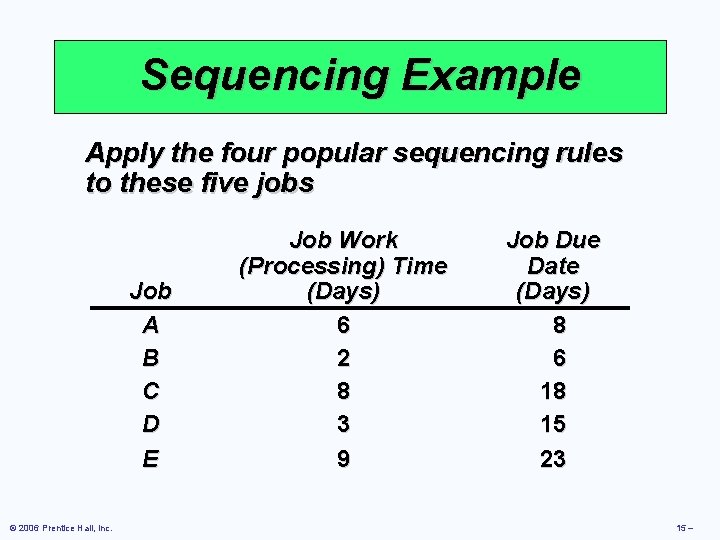

Sequencing Example Apply the four popular sequencing rules to these five jobs Job A B C D E © 2006 Prentice Hall, Inc. Job Work (Processing) Time (Days) 6 2 8 3 9 Job Due Date (Days) 8 6 18 15 23 15 –

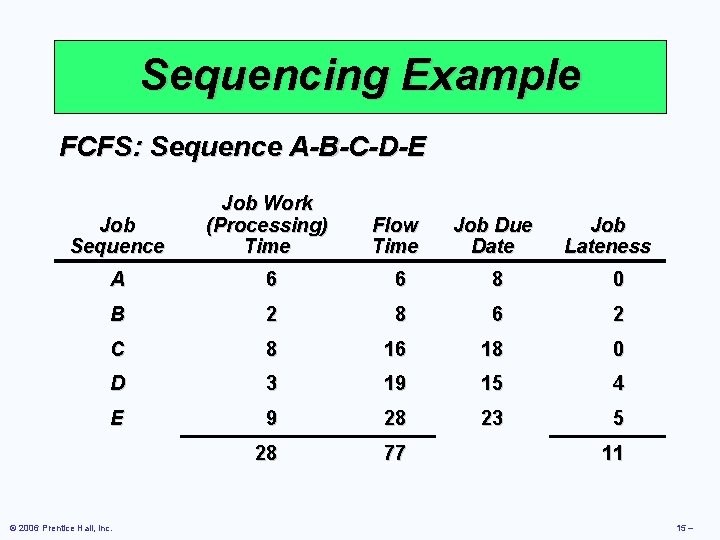

Sequencing Example FCFS: Sequence A-B-C-D-E Job Sequence Job Work (Processing) Time Flow Time Job Due Date A 6 6 8 0 B 2 8 6 2 C 8 16 18 0 D 3 19 15 4 E 9 28 23 5 28 77 © 2006 Prentice Hall, Inc. Job Lateness 11 15 –

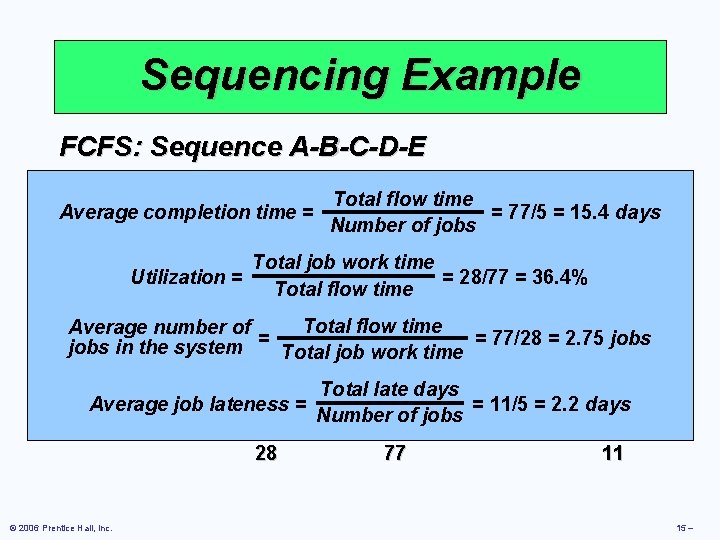

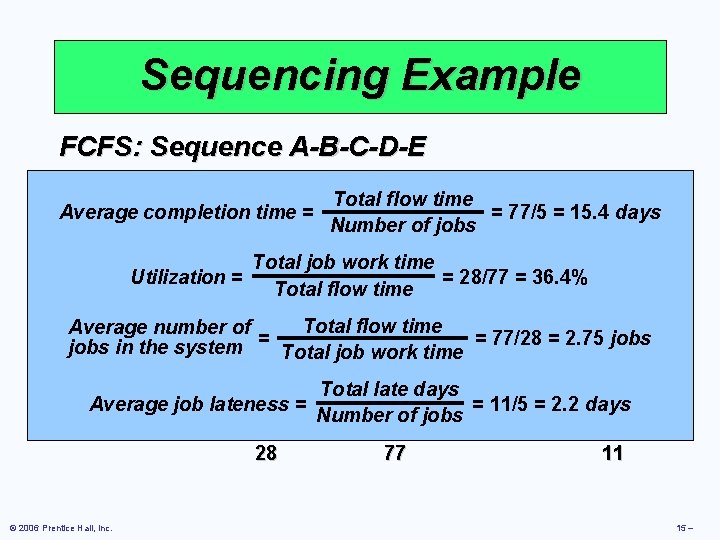

Sequencing Example FCFS: Sequence A-B-C-D-E Total flow time Jobtime Work Average completion = = 77/5 = 15. 4 days Job (Processing) Number Flowof jobs Job Due Job Sequence Time Date Lateness Total job work time = 28/77 A Utilization = 6 Total flow time 6 8 = 36. 4% 0 B 2 8 6 2 Total flow time Average number of = 77/28 = 2. 75 jobs. Cin the system =8 Total job work 16 time 18 0 D 3 19 days 15 4 Total late Average job lateness = = 11/5 = 2. 2 days Number of jobs E 9 28 23 5 28 © 2006 Prentice Hall, Inc. 77 11 15 –

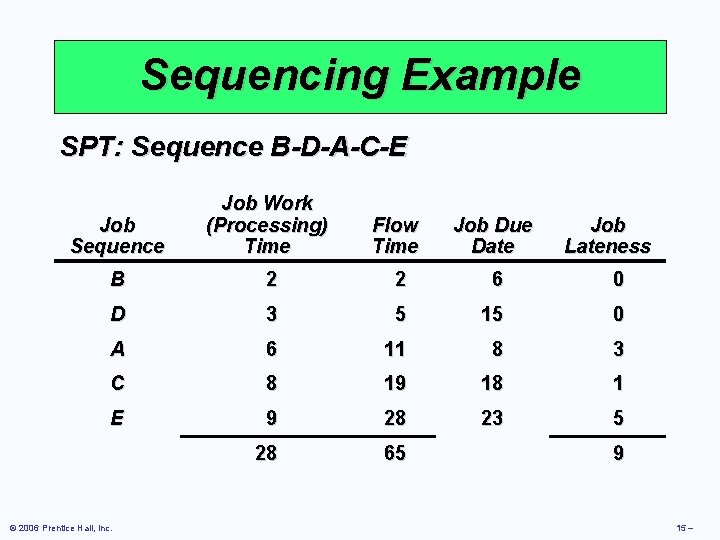

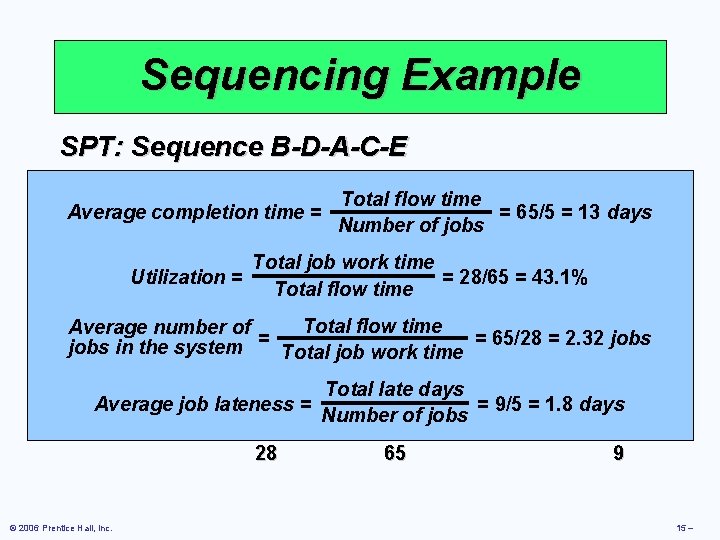

Sequencing Example SPT: Sequence B-D-A-C-E Job Sequence Job Work (Processing) Time Flow Time Job Due Date B 2 2 6 0 D 3 5 15 0 A 6 11 8 3 C 8 19 18 1 E 9 28 23 5 28 65 © 2006 Prentice Hall, Inc. Job Lateness 9 15 –

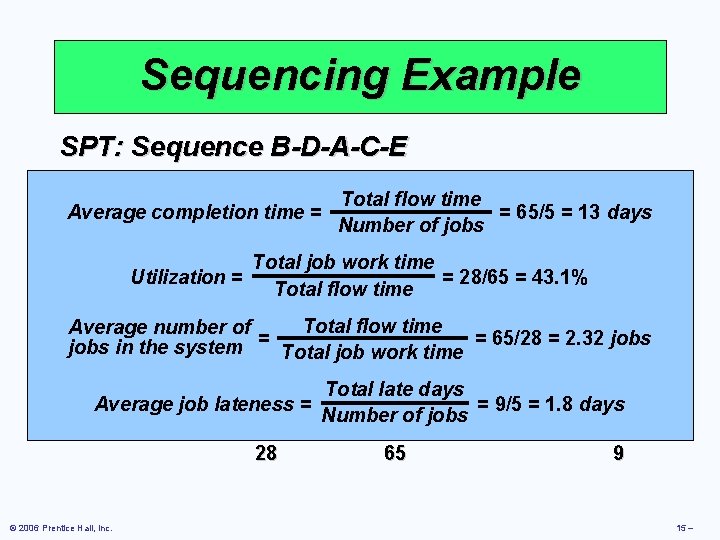

Sequencing Example SPT: Sequence B-D-A-C-E Total flow time Job Work Average completion time = = 65/5 = 13 days Job (Processing) Number Flow of jobs Job Due Job Sequence Time Date Lateness Total job work time = 28/65 B Utilization = 2 Total flow time 2 6 = 43. 1% 0 D 3 5 15 0 Total flow time Average number of = 65/28 = 2. 32 jobs. Ain the system =6 Total job work 11 time 8 3 C 8 19 days 18 1 Total late Average job lateness = = 9/5 = 1. 8 days Number of jobs E 9 28 23 5 28 © 2006 Prentice Hall, Inc. 65 9 15 –

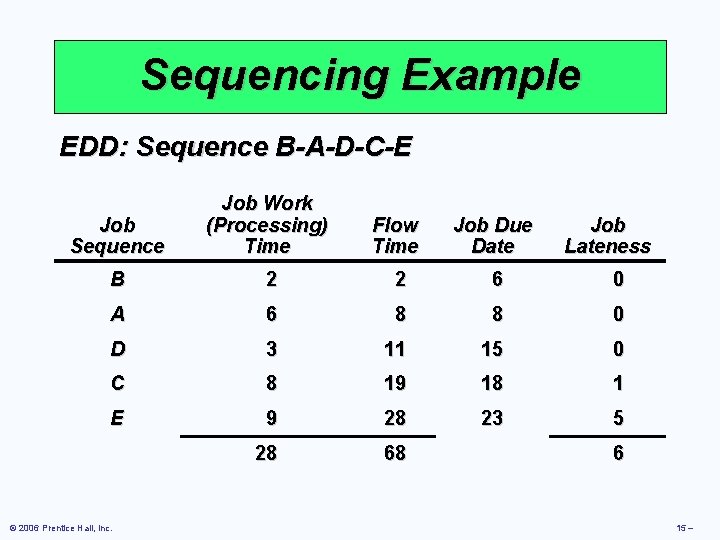

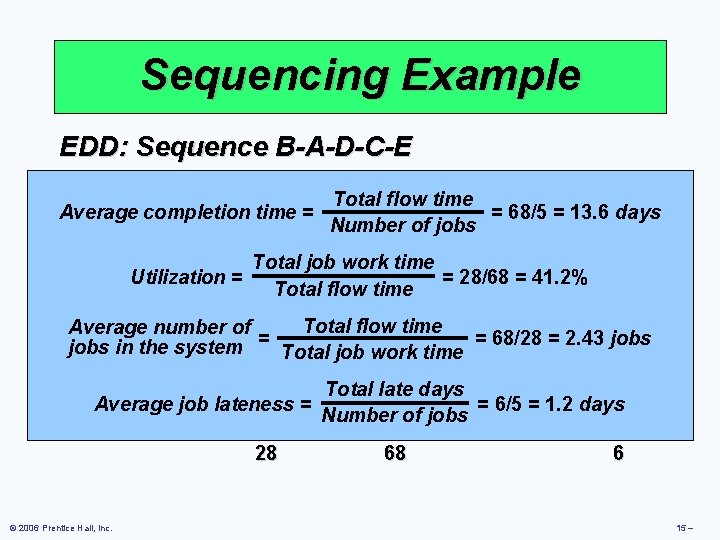

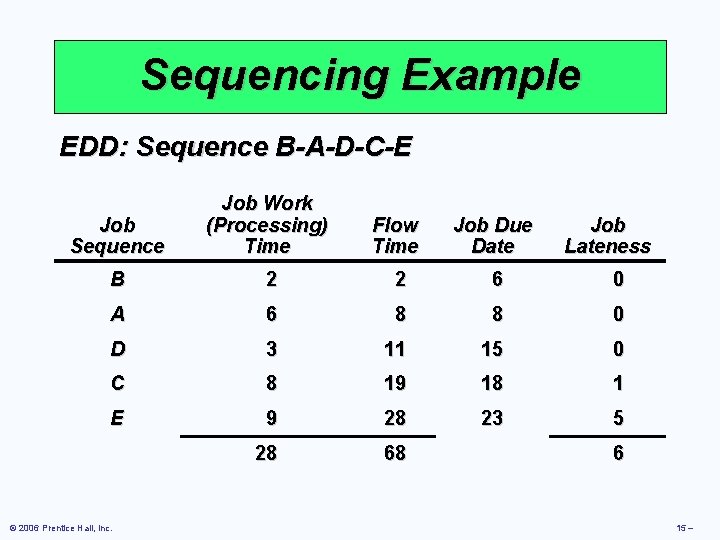

Sequencing Example EDD: Sequence B-A-D-C-E Job Sequence Job Work (Processing) Time Flow Time Job Due Date B 2 2 6 0 A 6 8 8 0 D 3 11 15 0 C 8 19 18 1 E 9 28 23 5 28 68 © 2006 Prentice Hall, Inc. Job Lateness 6 15 –

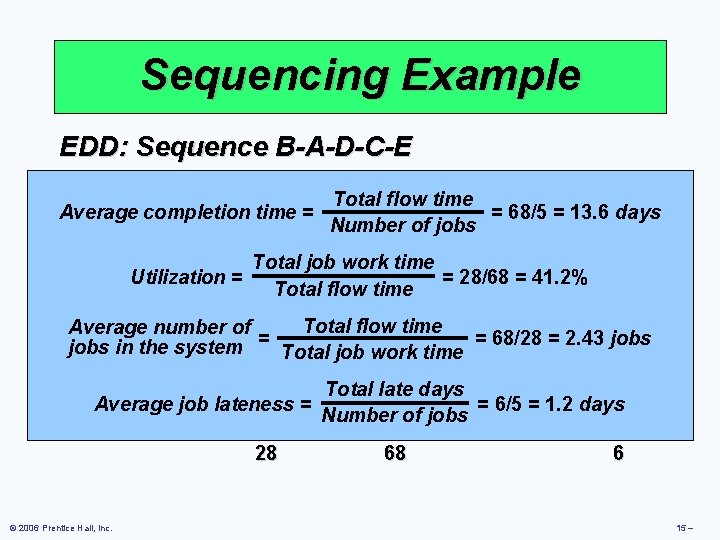

Sequencing Example EDD: Sequence B-A-D-C-E Total flow time Jobtime Work Average completion = = 68/5 = 13. 6 days Job (Processing) Number Flowof jobs Job Due Job Sequence Time Date Lateness Total job work time = 28/68 B Utilization = 2 Total flow time 2 6 = 41. 2% 0 A 6 8 8 0 Total flow time Average number of = 68/28 = 2. 43 jobs. Din the system =3 Total job work 11 time 15 0 C 8 19 days 18 1 Total late Average job lateness = = 6/5 = 1. 2 days Number of jobs E 9 28 23 5 28 © 2006 Prentice Hall, Inc. 68 6 15 –

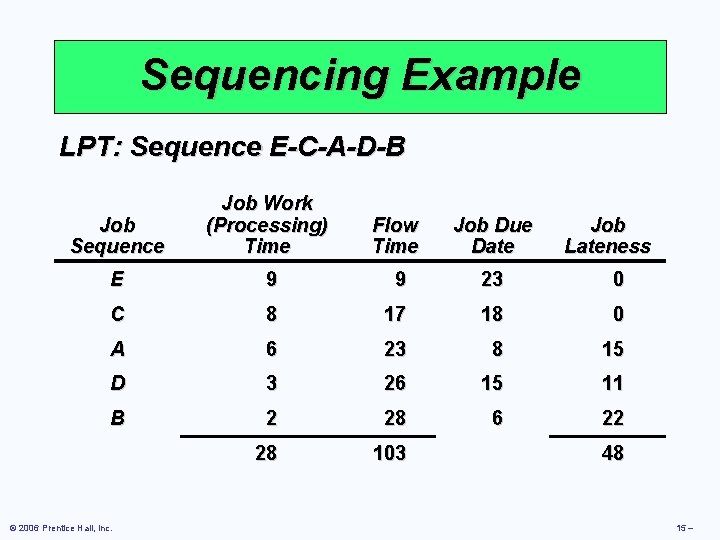

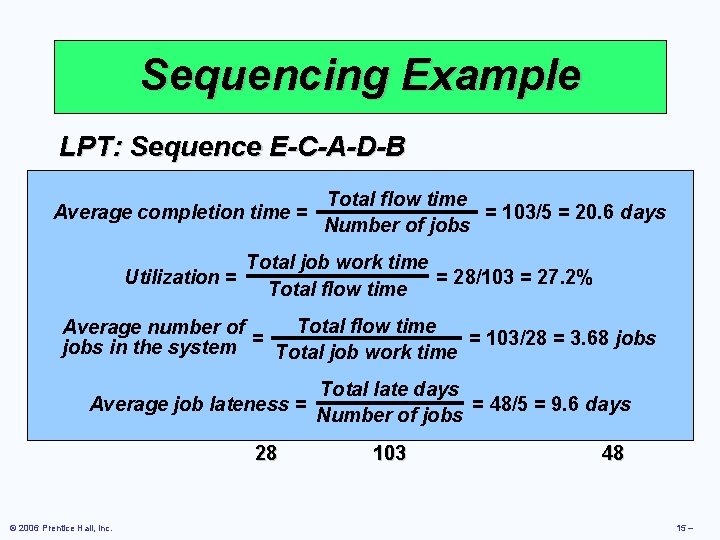

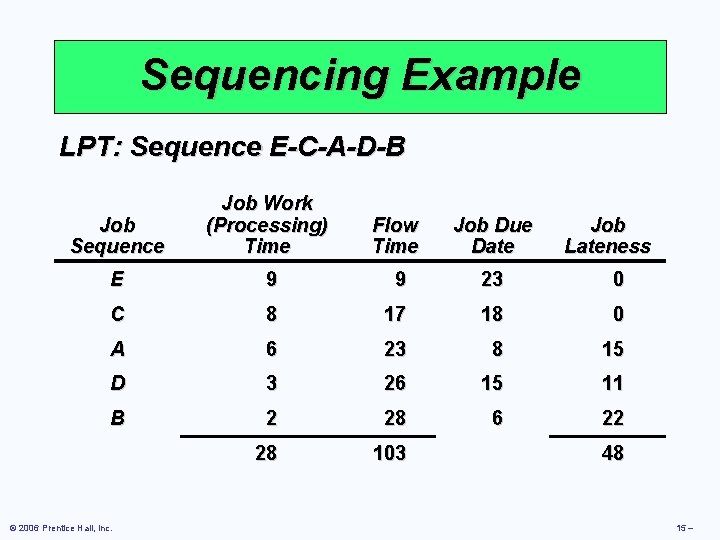

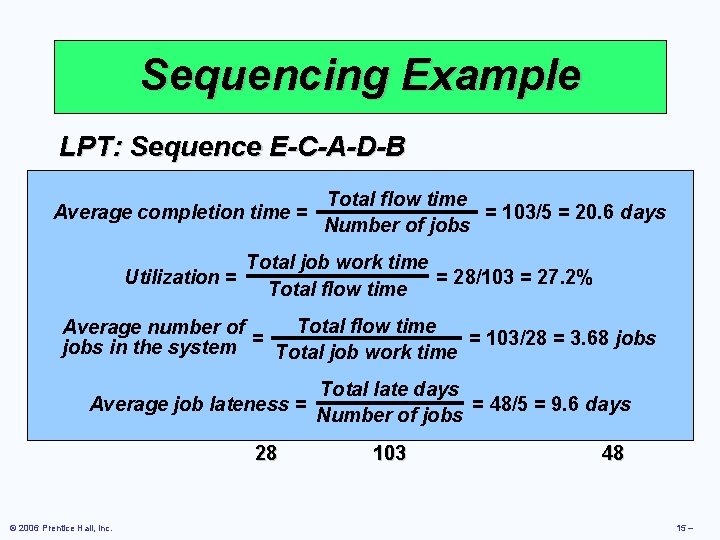

Sequencing Example LPT: Sequence E-C-A-D-B Job Sequence Job Work (Processing) Time Flow Time Job Due Date E 9 9 23 0 C 8 17 18 0 A 6 23 8 15 D 3 26 15 11 B 2 28 6 22 28 103 © 2006 Prentice Hall, Inc. Job Lateness 48 15 –

Sequencing Example LPT: Sequence E-C-A-D-B Total flow time Jobtime Work Average completion = = 103/5 = 20. 6 days Job (Processing)Number Flow Job of jobs Due Sequence Time Date Lateness Total job work time = 28/103 EUtilization = 9 Total flow time 9 23 = 27. 2% 0 C 8 17 18 0 Total flow time Average number of = = 103/28 = 3. 68 jobs in A the system 6 Total job work 23 time 8 15 D 3 26 days 15 11 Total late Average job lateness = = 48/5 = 9. 6 days Number of jobs B 2 28 6 22 28 © 2006 Prentice Hall, Inc. 103 48 15 –

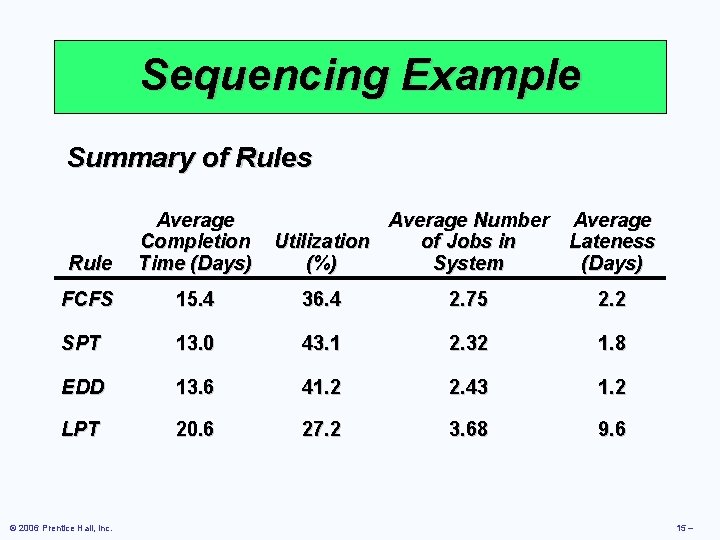

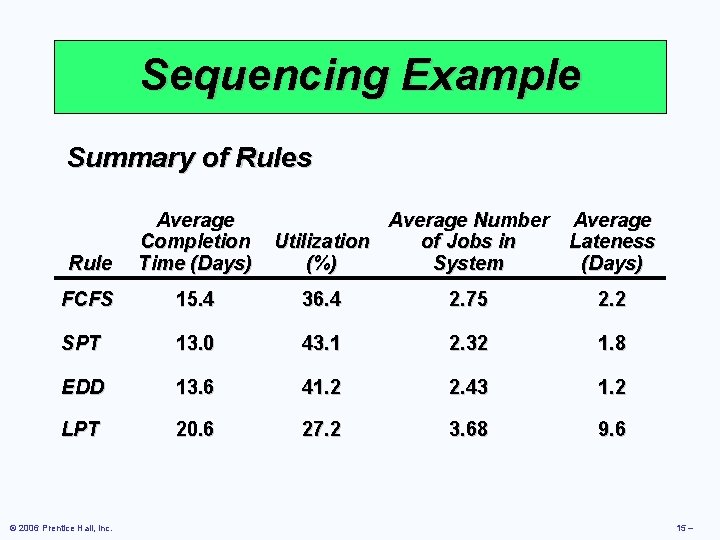

Sequencing Example Summary of Rules Rule Average Completion Time (Days) FCFS 15. 4 36. 4 2. 75 2. 2 SPT 13. 0 43. 1 2. 32 1. 8 EDD 13. 6 41. 2 2. 43 1. 2 LPT 20. 6 27. 2 3. 68 9. 6 © 2006 Prentice Hall, Inc. Average Number Average Utilization of Jobs in Lateness (%) System (Days) 15 –

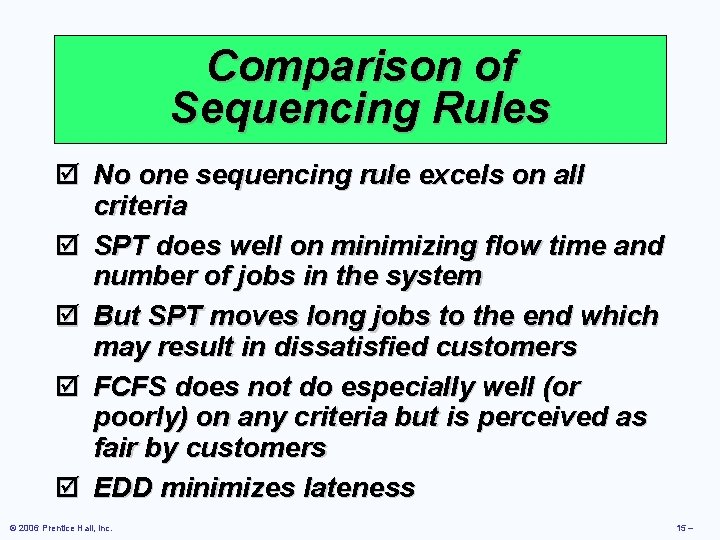

Comparison of Sequencing Rules þ No one sequencing rule excels on all criteria þ SPT does well on minimizing flow time and number of jobs in the system þ But SPT moves long jobs to the end which may result in dissatisfied customers þ FCFS does not do especially well (or poorly) on any criteria but is perceived as fair by customers þ EDD minimizes lateness © 2006 Prentice Hall, Inc. 15 –

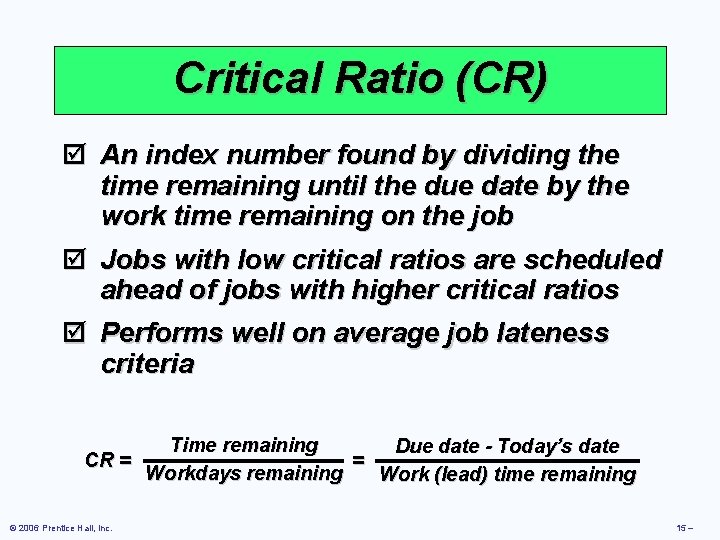

Critical Ratio (CR) þ An index number found by dividing the time remaining until the due date by the work time remaining on the job þ Jobs with low critical ratios are scheduled ahead of jobs with higher critical ratios þ Performs well on average job lateness criteria Time remaining Due date - Today’s date CR = = Workdays remaining Work (lead) time remaining © 2006 Prentice Hall, Inc. 15 –

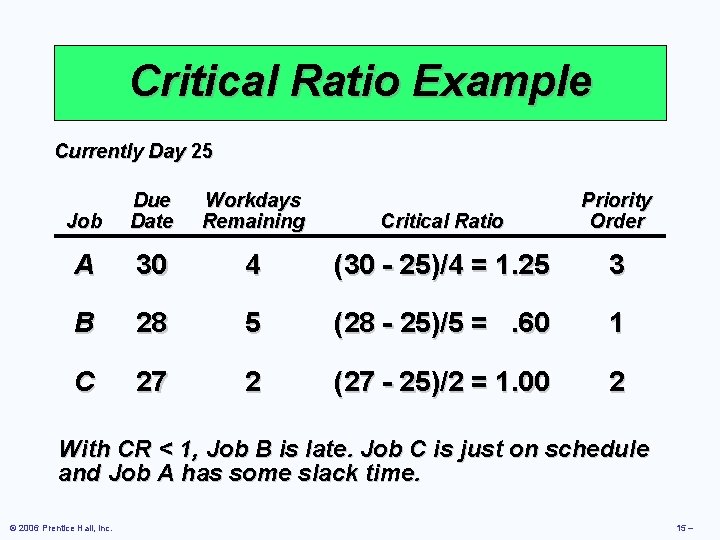

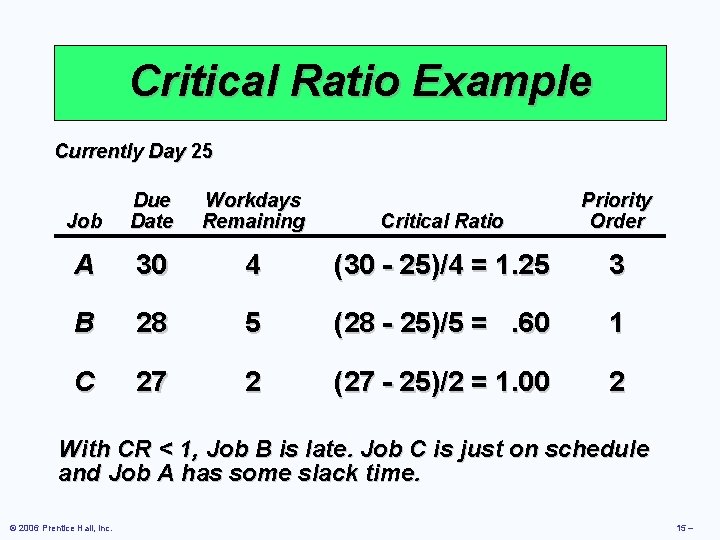

Critical Ratio Example Currently Day 25 Job Due Date Workdays Remaining Critical Ratio Priority Order A 30 4 (30 - 25)/4 = 1. 25 3 B 28 5 (28 - 25)/5 =. 60 1 C 27 2 (27 - 25)/2 = 1. 00 2 With CR < 1, Job B is late. Job C is just on schedule and Job A has some slack time. © 2006 Prentice Hall, Inc. 15 –

Critical Ratio Technique 1. Helps determine the status of specific jobs 2. Establishes relative priorities among jobs on a common basis 3. Relates both stock and make-to-order jobs on a common basis 4. Adjusts priorities automatically for changes in both demand job progress 5. Dynamically tracks job progress © 2006 Prentice Hall, Inc. 15 –

Sequencing N Jobs on Two Machines: Johnson’s Rule þ Works with two or more jobs that pass through the same two machines or work centers þ Minimizes total production time and idle time © 2006 Prentice Hall, Inc. 15 –

Johnson’s Rule 1. List all jobs and times for each work center 2. Choose the job with the shortest activity time. If that time is in the first work center, schedule the job first. If it is in the second work center, schedule the job last. 3. Once a job is scheduled, it is eliminated from the list 4. Repeat steps 2 and 3 working toward the center of the sequence © 2006 Prentice Hall, Inc. 15 –

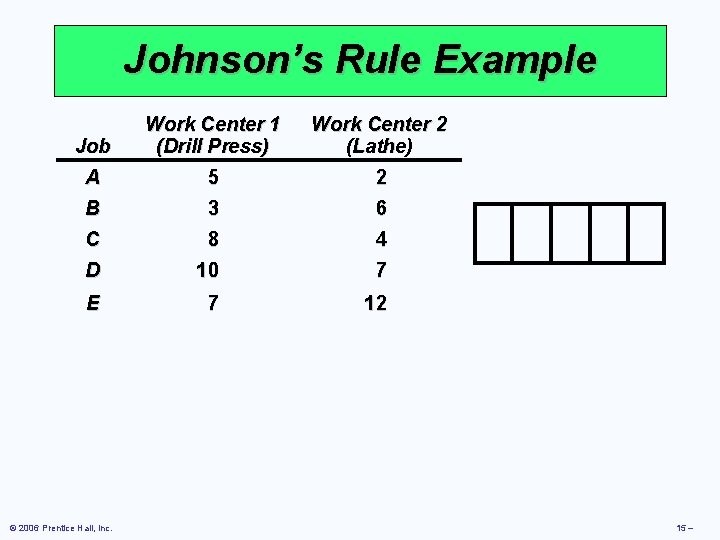

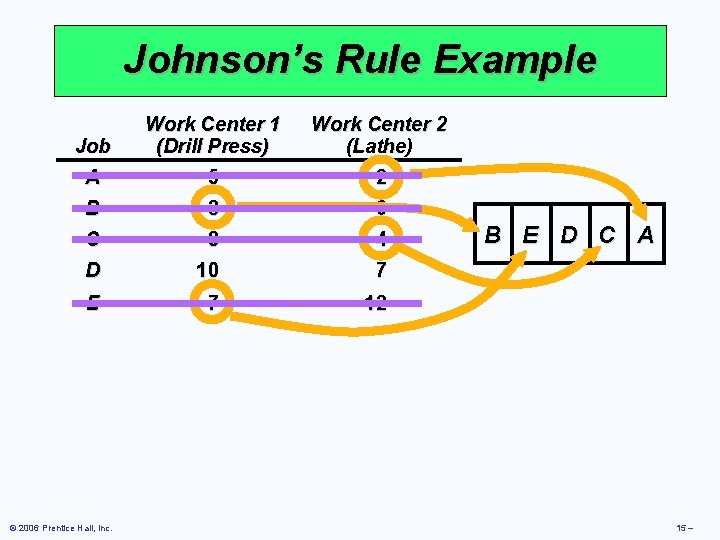

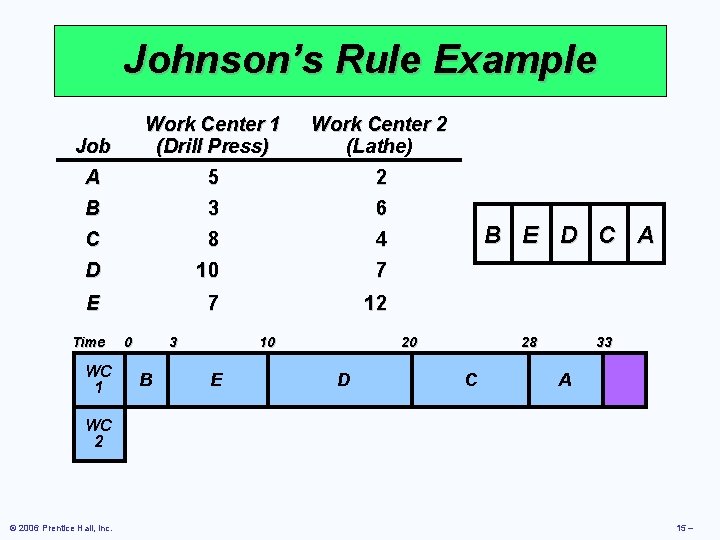

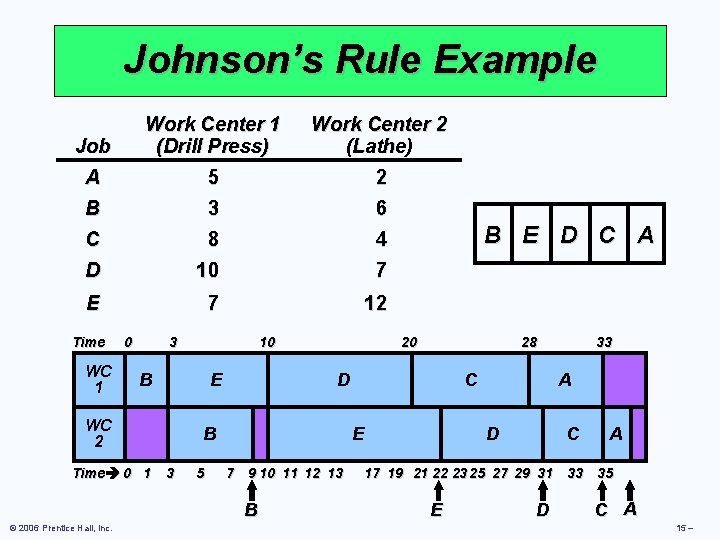

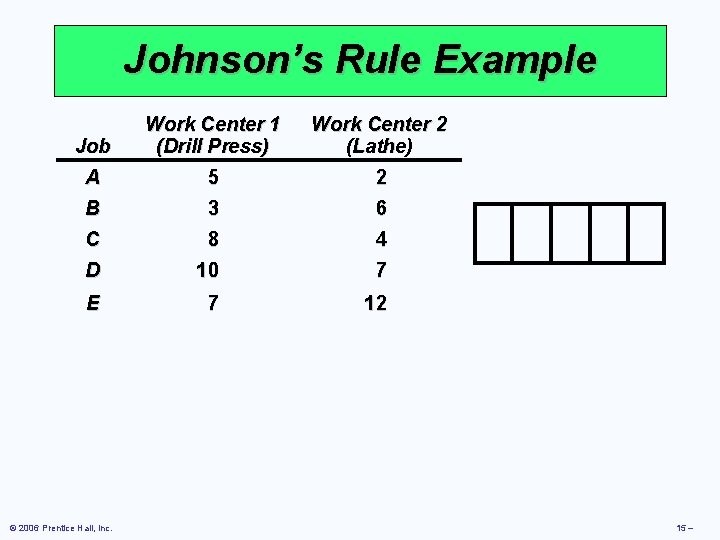

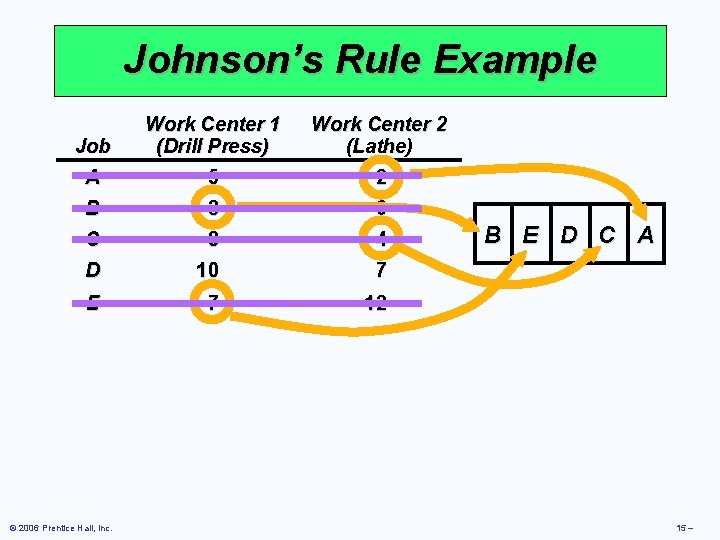

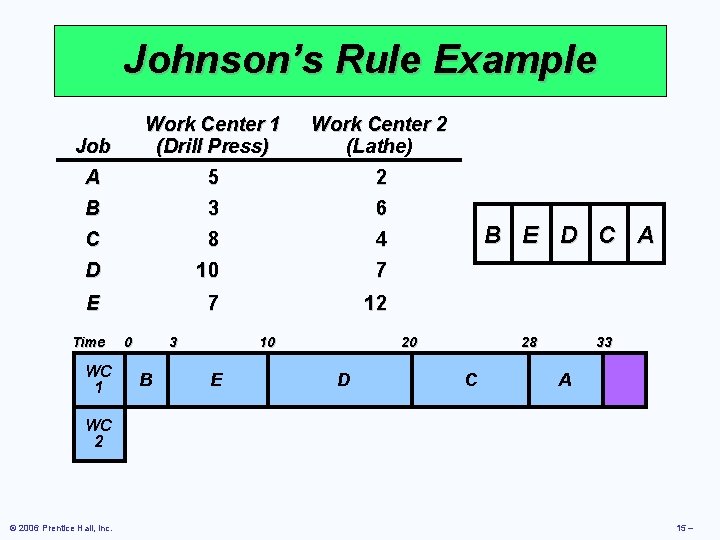

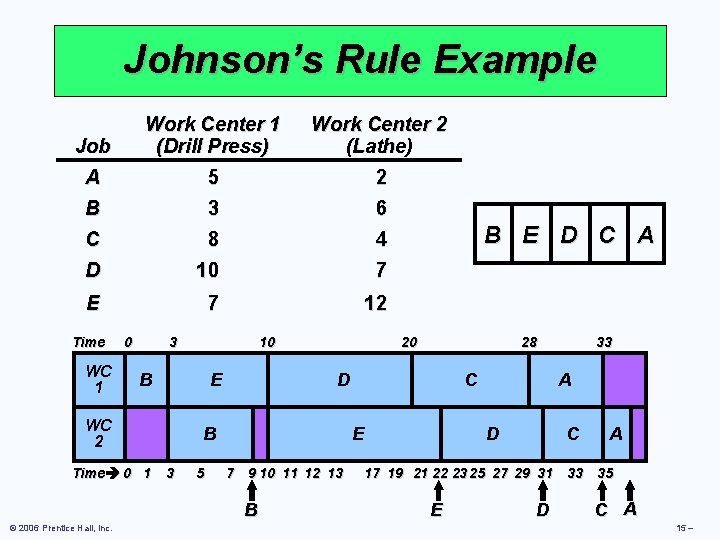

Johnson’s Rule Example Job Work Center 1 (Drill Press) Work Center 2 (Lathe) A 5 2 B 3 6 C 8 4 D 10 7 E 7 12 © 2006 Prentice Hall, Inc. 15 –

Johnson’s Rule Example Job Work Center 1 (Drill Press) Work Center 2 (Lathe) A 5 2 B 3 6 C 8 4 D 10 7 E 7 12 © 2006 Prentice Hall, Inc. B E D C A 15 –

Johnson’s Rule Example Job Work Center 1 (Drill Press) Work Center 2 (Lathe) A 5 2 B 3 6 C 8 4 D 10 7 E 7 12 Time WC 1 0 3 B 10 E B E D C A 20 D 28 C 33 A WC 2 © 2006 Prentice Hall, Inc. 15 –

Johnson’s Rule Example Job Work Center 1 (Drill Press) Work Center 2 (Lathe) A 5 2 B 3 6 C 8 4 D 10 7 E 7 12 Time WC 1 0 3 10 B E WC 2 Time 0 1 5 28 D C E 7 9 10 11 12 13 B © 2006 Prentice Hall, Inc. 20 B 3 B E D C A 33 A D C A 17 19 21 22 23 25 27 29 31 33 35 E D C A 15 –

Limitations of Rule-Based Dispatching Systems 1. Scheduling is dynamic and rules need to be revised to adjust to changes 2. Rules do not look upstream or downstream 3. Rules do not look beyond due dates © 2006 Prentice Hall, Inc. 15 –

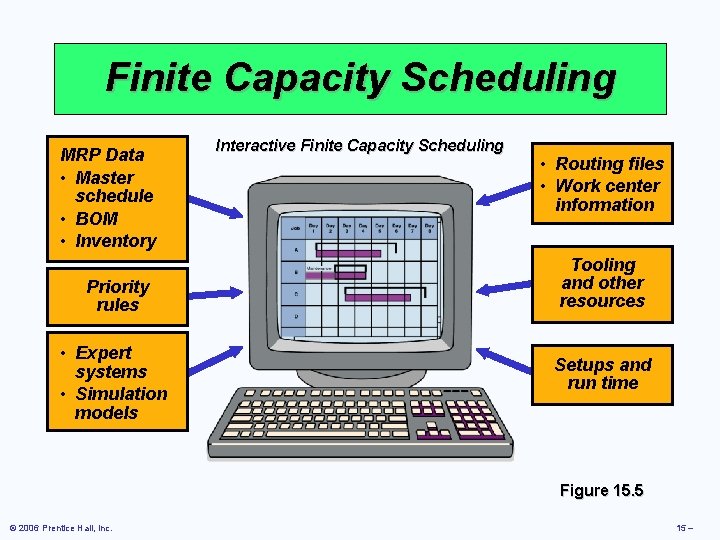

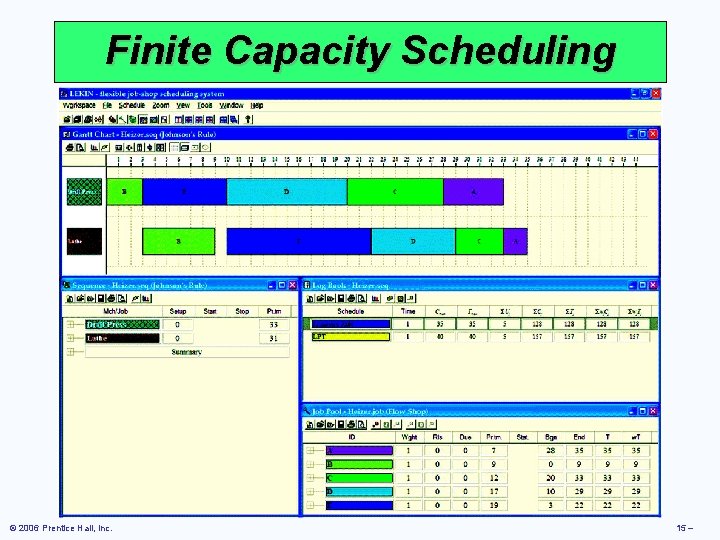

Finite Capacity Scheduling þ Overcomes disadvantages of rule-based systems by providing an interactive, computer-based graphical system þ May include rules and expert systems or simulation to allow real-time response to system changes þ Initial data often from an MRP system þ FCS allows the balancing of delivery needs and efficiency © 2006 Prentice Hall, Inc. 15 –

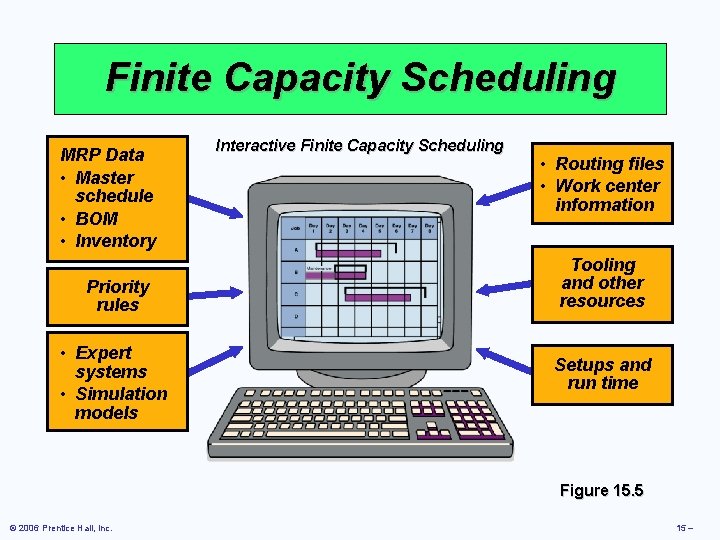

Finite Capacity Scheduling MRP Data • Master schedule • BOM • Inventory Priority rules • Expert systems • Simulation models Interactive Finite Capacity Scheduling • Routing files • Work center information Tooling and other resources Setups and run time Figure 15. 5 © 2006 Prentice Hall, Inc. 15 –

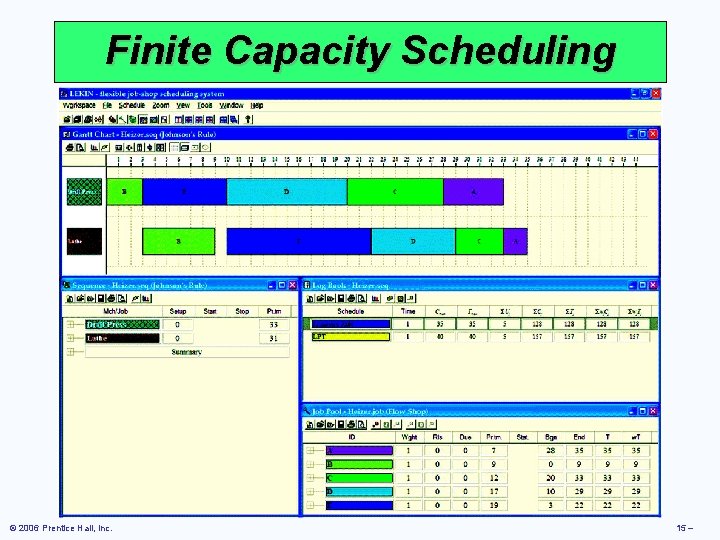

Finite Capacity Scheduling © 2006 Prentice Hall, Inc. 15 –

Theory of Constraints þ Throughput is the number of units processed through the facility and sold þ TOC deals with the limits an organization faces in achieving its goals 1. 2. 3. 4. Identify the constraints Develop a plan for overcoming the constraints Focus resources on accomplishing the plan Reduce the effects of constraints by offloading work or increasing capacity 5. Once successful, return to step 1 and identify new constraints © 2006 Prentice Hall, Inc. 15 –

Bottlenecks þ Bottleneck work centers are constraints that limit output þ Common occurrence due to frequent changes þ Management techniques include: þ Increasing the capacity of the constraint þ Cross-trained employees and maintenance þ Alternative routings þ Moving inspection and test þ Scheduling throughput to match bottleneck capacity © 2006 Prentice Hall, Inc. 15 –

Drum, Buffer, Rope þ The drum is the beat of the system and provides the schedule or pace of production þ The buffer is the inventory necessary to keep constraints operating at capacity þ The rope provides the synchronization necessary to pull units through the system © 2006 Prentice Hall, Inc. 15 –

Scheduling Repetitive Facilities þ Level material use can help repetitive facilities þ Better satisfy customer demand þ Lower inventory investment þ Reduce batch size þ Better utilize equipment and facilities © 2006 Prentice Hall, Inc. 15 –

Scheduling Repetitive Facilities þ Advantages include: 1. Lower inventory levels 2. Faster product throughput 3. Improved component quality 4. 5. Reduced floor-space requirements Improved communications 6. Smoother production process © 2006 Prentice Hall, Inc. 15 –

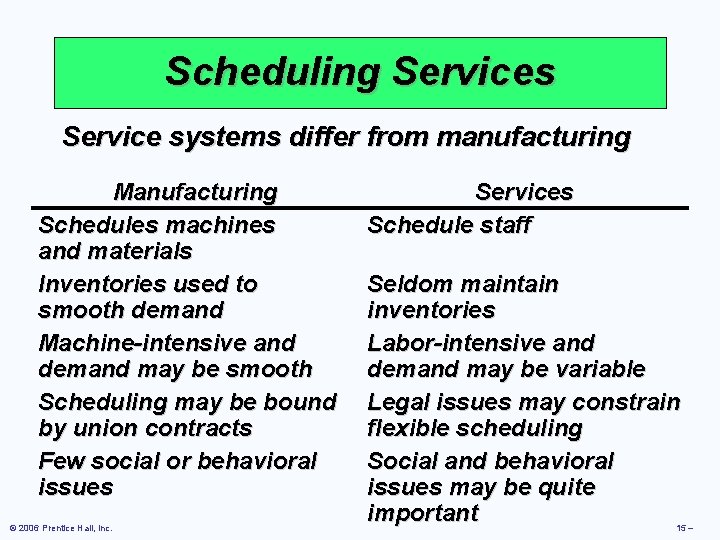

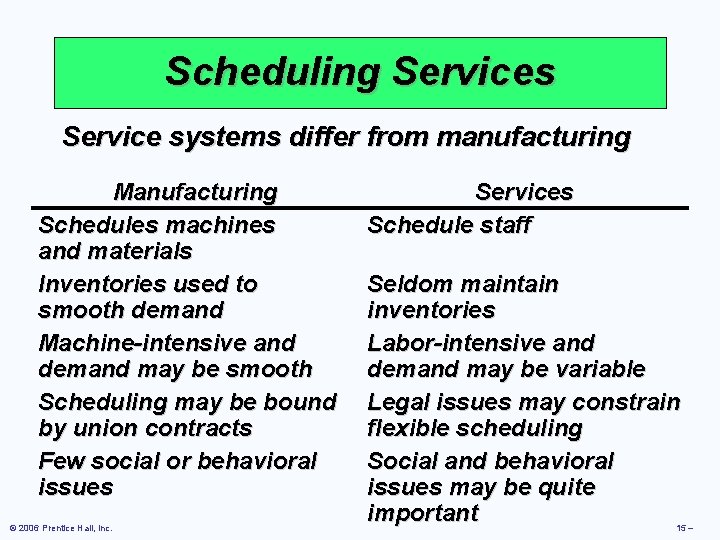

Scheduling Services Service systems differ from manufacturing Manufacturing Schedules machines and materials Inventories used to smooth demand Machine-intensive and demand may be smooth Scheduling may be bound by union contracts Few social or behavioral issues © 2006 Prentice Hall, Inc. Services Schedule staff Seldom maintain inventories Labor-intensive and demand may be variable Legal issues may constrain flexible scheduling Social and behavioral issues may be quite important 15 –

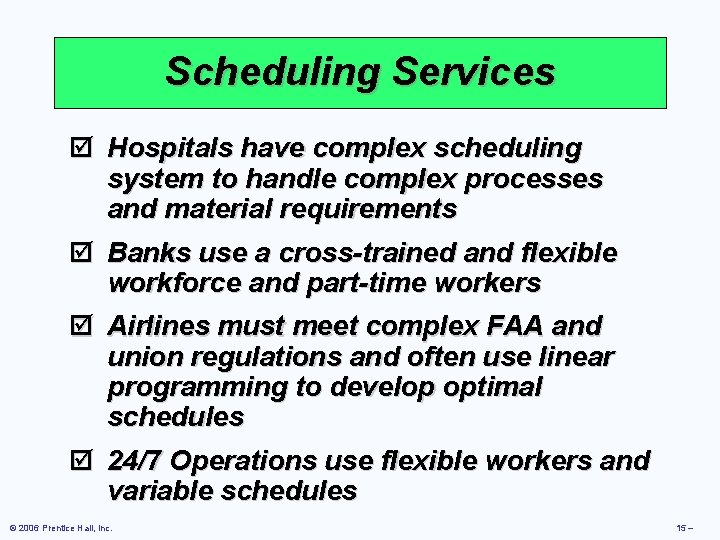

Scheduling Services þ Hospitals have complex scheduling system to handle complex processes and material requirements þ Banks use a cross-trained and flexible workforce and part-time workers þ Airlines must meet complex FAA and union regulations and often use linear programming to develop optimal schedules þ 24/7 Operations use flexible workers and variable schedules © 2006 Prentice Hall, Inc. 15 –

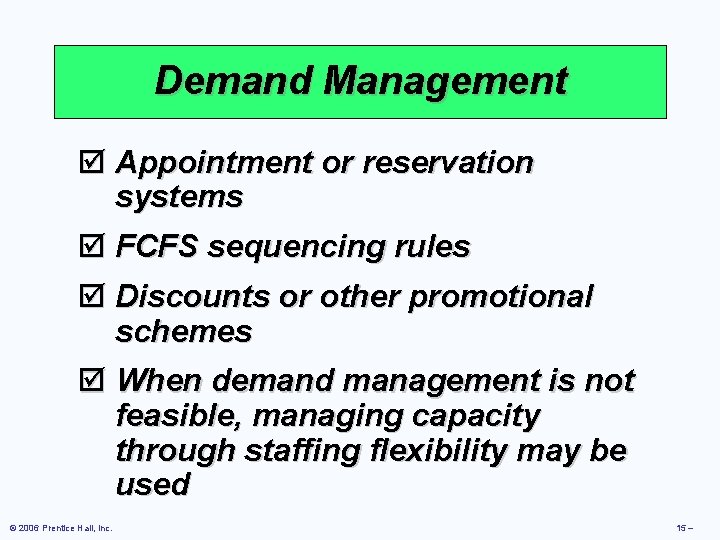

Demand Management þ Appointment or reservation systems þ FCFS sequencing rules þ Discounts or other promotional schemes þ When demand management is not feasible, managing capacity through staffing flexibility may be used © 2006 Prentice Hall, Inc. 15 –

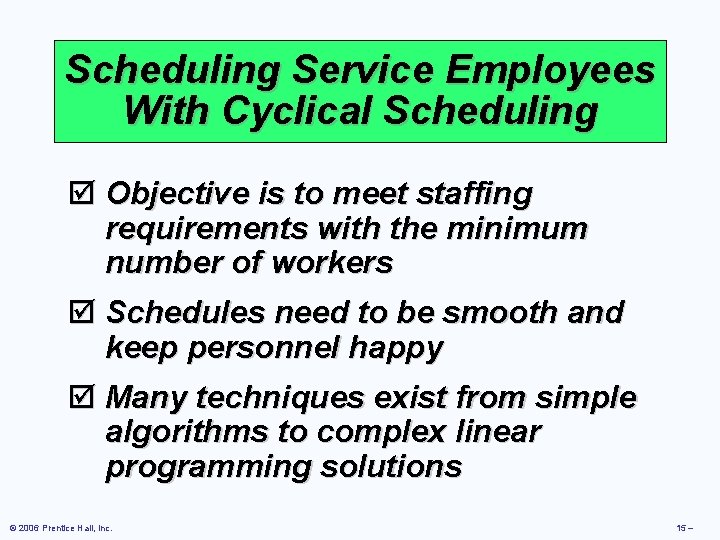

Scheduling Service Employees With Cyclical Scheduling þ Objective is to meet staffing requirements with the minimum number of workers þ Schedules need to be smooth and keep personnel happy þ Many techniques exist from simple algorithms to complex linear programming solutions © 2006 Prentice Hall, Inc. 15 –

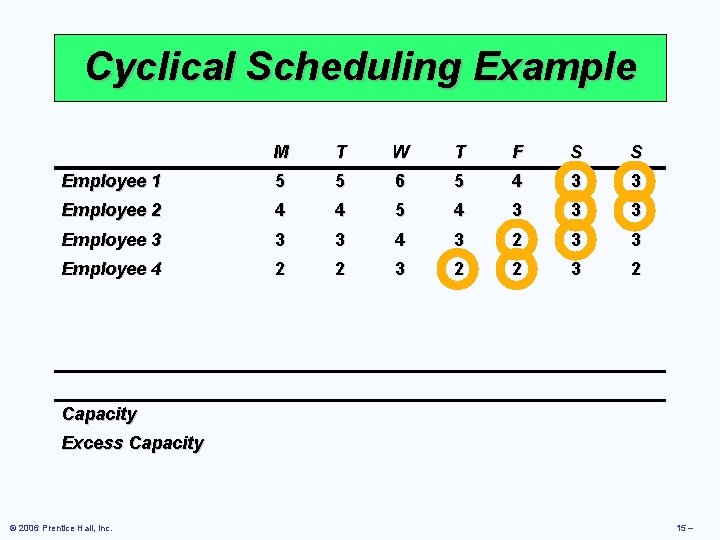

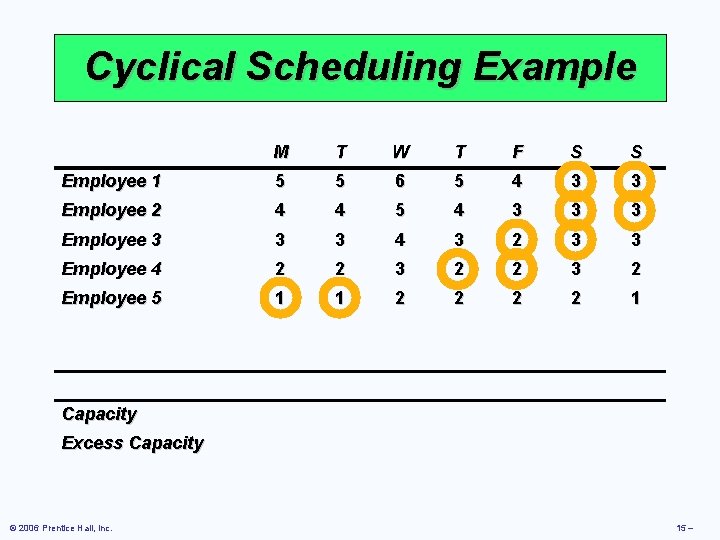

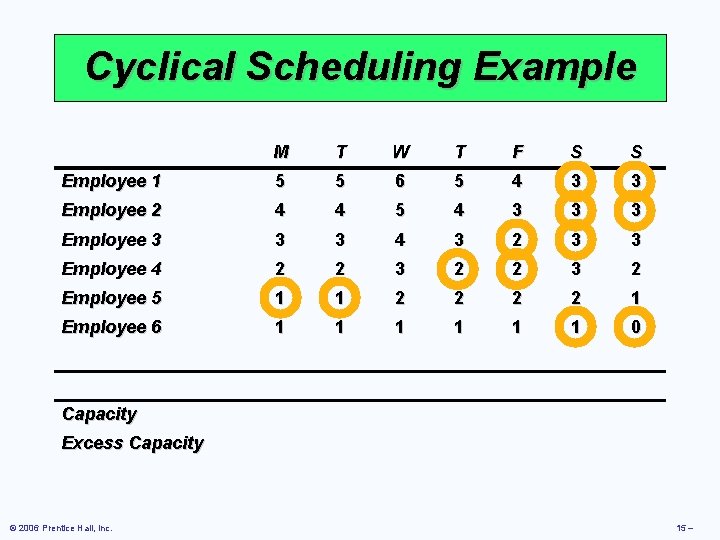

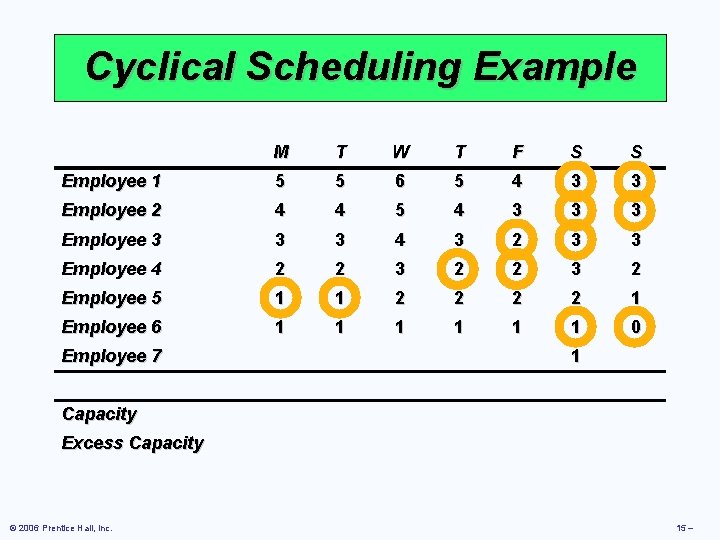

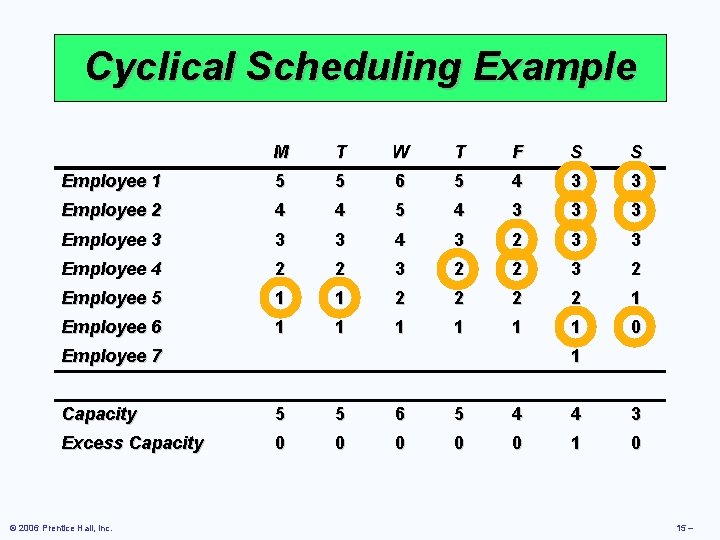

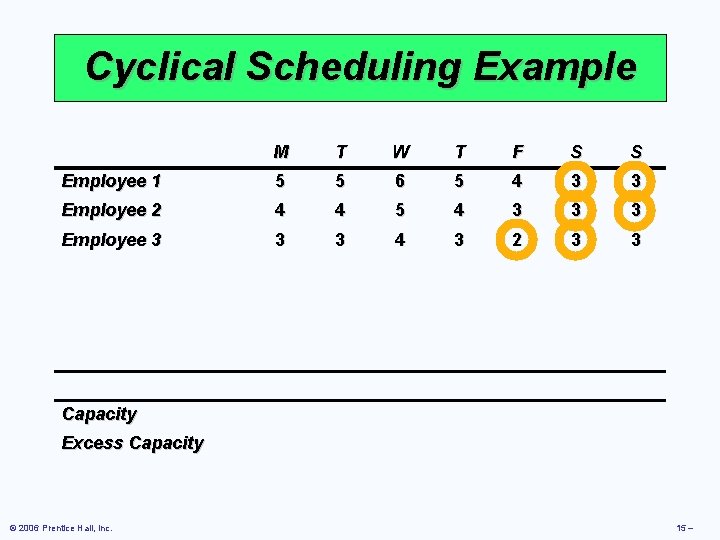

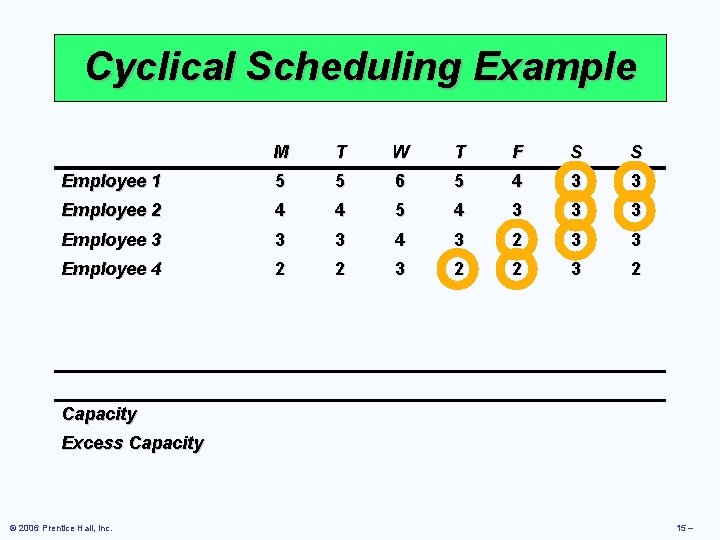

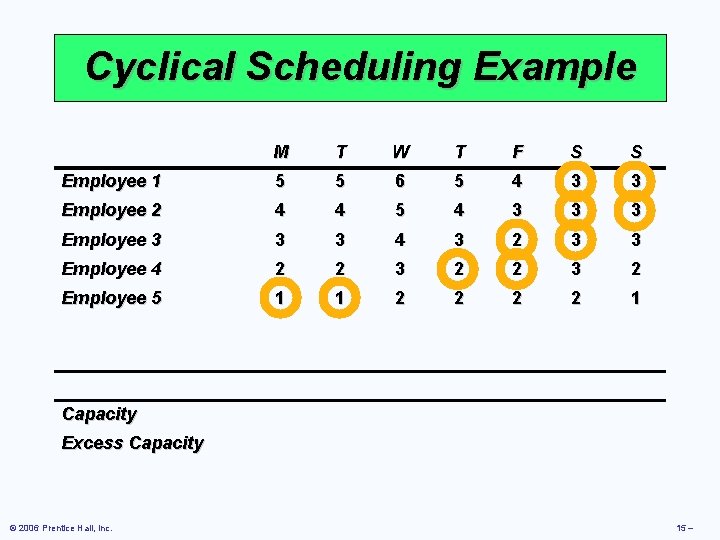

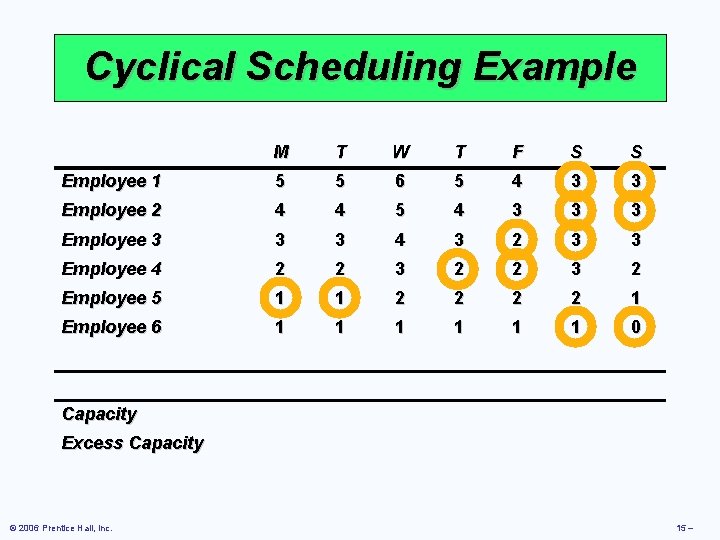

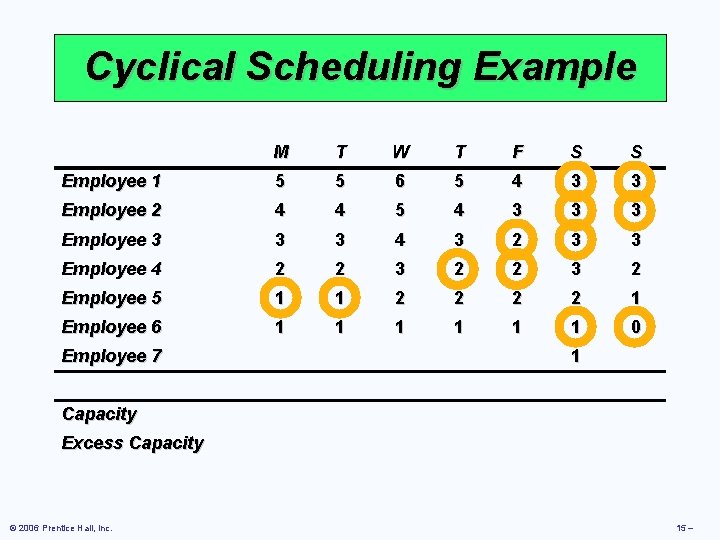

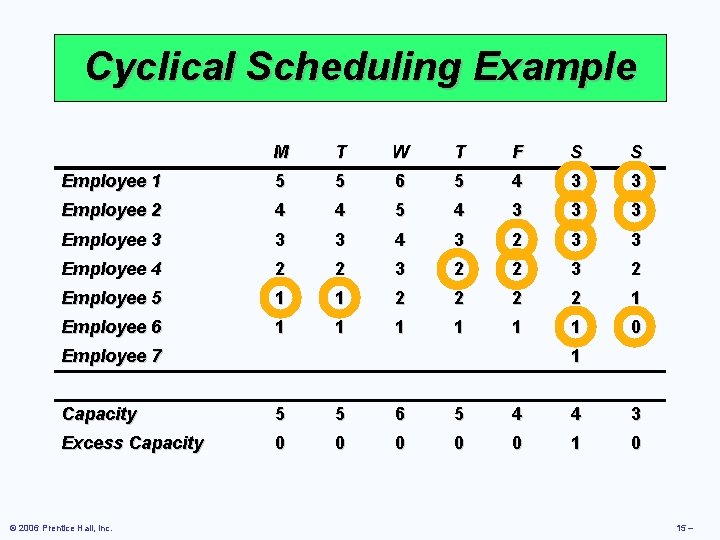

Cyclical Scheduling Example 1. 2. Determine the staffing requirements Identify two consecutive days with the lowest total requirements and assign these as days off 3. Make a new set of requirements subtracting the days worked by the first employee 4. Apply step 2 to the new row 5. Repeat steps 3 and 4 until all requirements have been met © 2006 Prentice Hall, Inc. 15 –

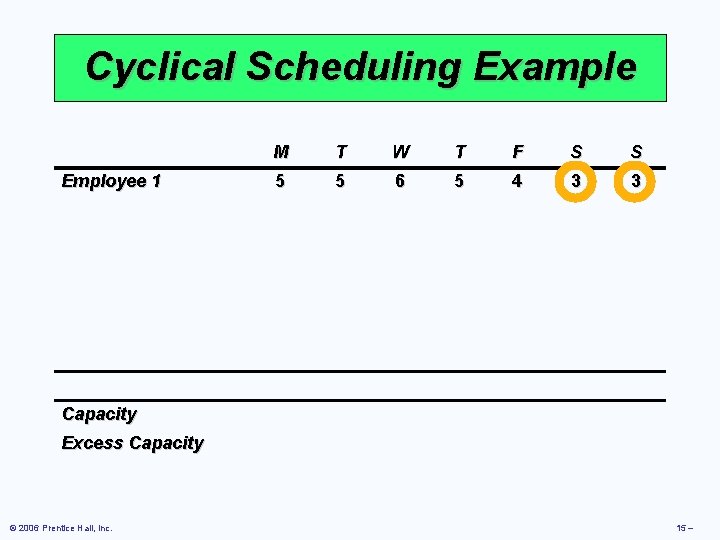

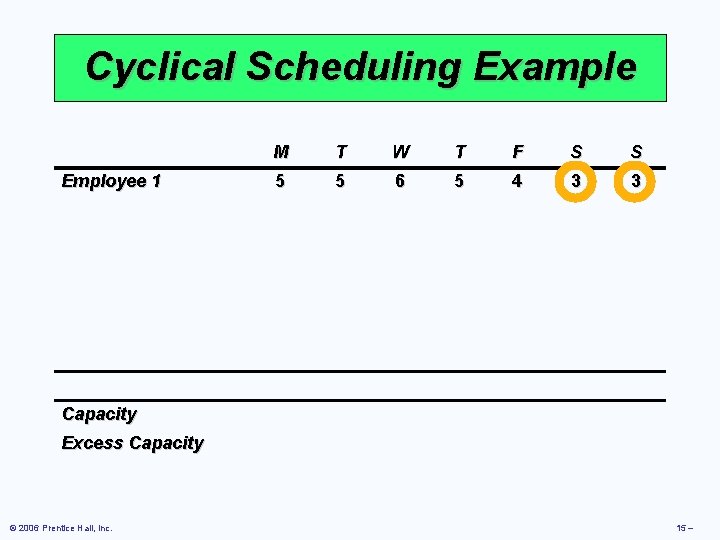

Cyclical Scheduling Example Employee 1 M T W T F S S 5 5 6 5 4 3 3 Capacity Excess Capacity © 2006 Prentice Hall, Inc. 15 –

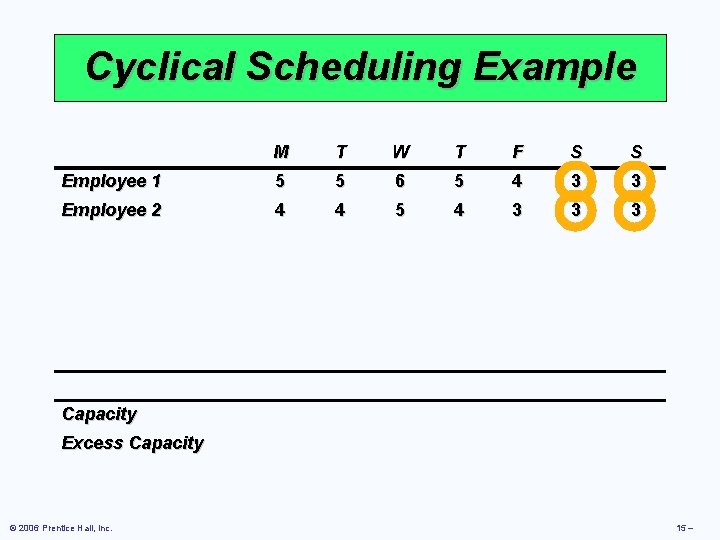

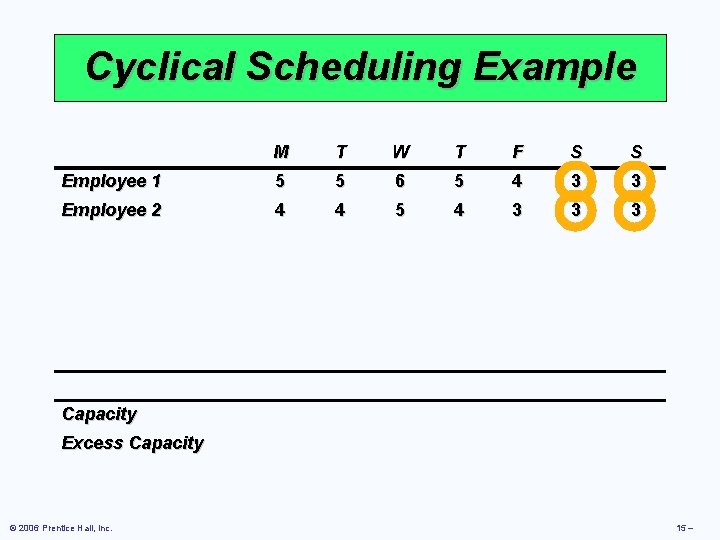

Cyclical Scheduling Example M T W T F S S Employee 1 5 5 6 5 4 3 3 Employee 2 4 4 5 4 3 3 3 Capacity Excess Capacity © 2006 Prentice Hall, Inc. 15 –

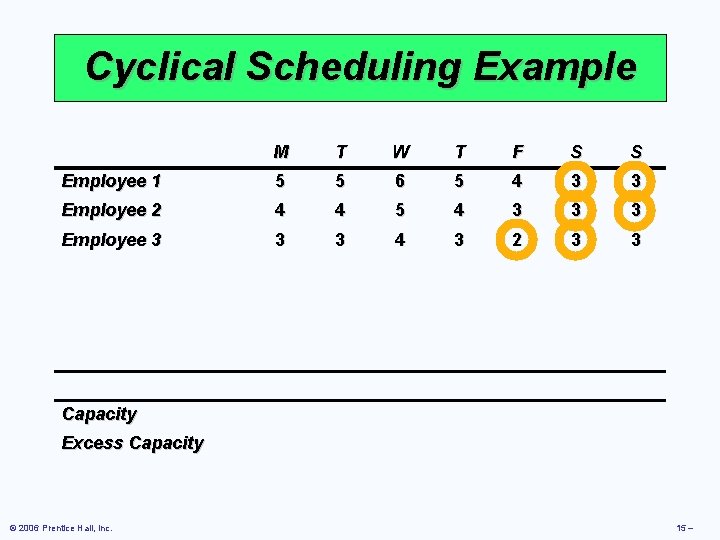

Cyclical Scheduling Example M T W T F S S Employee 1 5 5 6 5 4 3 3 Employee 2 4 4 5 4 3 3 3 Employee 3 3 3 4 3 2 3 3 Capacity Excess Capacity © 2006 Prentice Hall, Inc. 15 –

Cyclical Scheduling Example M T W T F S S Employee 1 5 5 6 5 4 3 3 Employee 2 4 4 5 4 3 3 3 Employee 3 3 3 4 3 2 3 3 Employee 4 2 2 3 2 Capacity Excess Capacity © 2006 Prentice Hall, Inc. 15 –

Cyclical Scheduling Example M T W T F S S Employee 1 5 5 6 5 4 3 3 Employee 2 4 4 5 4 3 3 3 Employee 3 3 3 4 3 2 3 3 Employee 4 2 2 3 2 Employee 5 1 1 2 2 1 Capacity Excess Capacity © 2006 Prentice Hall, Inc. 15 –

Cyclical Scheduling Example M T W T F S S Employee 1 5 5 6 5 4 3 3 Employee 2 4 4 5 4 3 3 3 Employee 3 3 3 4 3 2 3 3 Employee 4 2 2 3 2 Employee 5 1 1 2 2 1 Employee 6 1 1 1 0 Capacity Excess Capacity © 2006 Prentice Hall, Inc. 15 –

Cyclical Scheduling Example M T W T F S S Employee 1 5 5 6 5 4 3 3 Employee 2 4 4 5 4 3 3 3 Employee 3 3 3 4 3 2 3 3 Employee 4 2 2 3 2 Employee 5 1 1 2 2 1 Employee 6 1 1 1 0 Employee 7 1 Capacity Excess Capacity © 2006 Prentice Hall, Inc. 15 –

Cyclical Scheduling Example M T W T F S S Employee 1 5 5 6 5 4 3 3 Employee 2 4 4 5 4 3 3 3 Employee 3 3 3 4 3 2 3 3 Employee 4 2 2 3 2 Employee 5 1 1 2 2 1 Employee 6 1 1 1 0 Employee 7 1 Capacity 5 5 6 5 4 4 3 Excess Capacity 0 0 0 1 0 © 2006 Prentice Hall, Inc. 15 –