Oh My Aching Back A Review of Spinal

Oh, My Aching Back! A Review of Spinal Arthropathies Educational Exhibit, 2014 RSNA Annual Meeting, #MKE 106 Elana B. Smith, MD Kimberly Gardner, MD Kiran S. Talekar, MD Adam E. Flanders, MD Adam C. Zoga, MD Correspondence can be addressed to: Elana B. Smith, MD Thomas Jefferson University Hospital Department of Radiology 132 South 10 th Street Suite 1088, 10 Main Philadelphia, PA 19107 elana. smith@ucdenver. edu 215 -955 -6028 The authors have no financial disclosures.

Background Information • Low back pain is the second most common reason for symptomatic physician visits each year and is a leading cause of disability. • According to the World Health Organization, the estimated costs associated with low back pain range from $100 billion to $200 billion a year (including costs of treatment, lost wages, and decreased productivity). • Although the most common cause of back pain is degenerative, other causes must also be considered, and imaging plays an important role in diagnosis.

Learning Objectives • Review pertinent anatomy relevant to spinal arthropathy. • Explain the difference between syndesmophytes and osteophytes. • Discuss the pathophysiology and clinical course of the following: – – – Degenerative disk disease Rheumatoid arthritis Ankylosing spondylitis Psoriatic arthritis Crystal deposition diseases Metabolic diseases • Describe the spectrum of imaging features and distinguishing imaging features of these spinal arthropathies, which can be used to differentiate these entities.

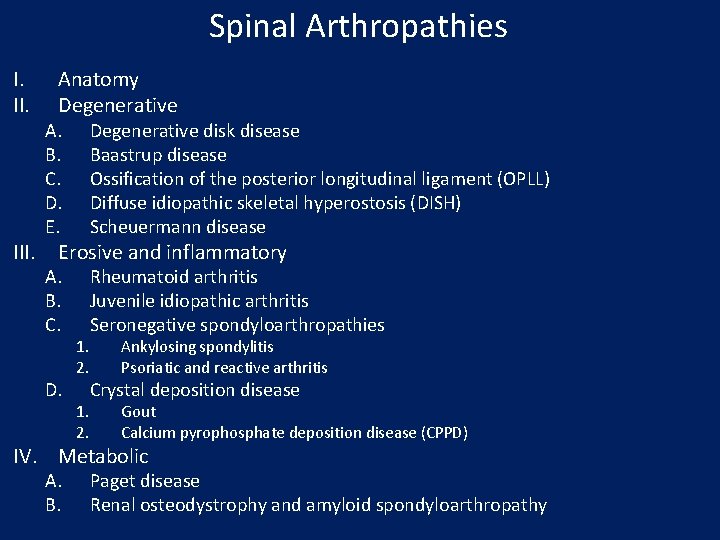

Spinal Arthropathies I. II. Anatomy Degenerative A. B. C. D. E. Degenerative disk disease Baastrup disease Ossification of the posterior longitudinal ligament (OPLL) Diffuse idiopathic skeletal hyperostosis (DISH) Scheuermann disease A. B. C. Rheumatoid arthritis Juvenile idiopathic arthritis Seronegative spondyloarthropathies III. Erosive and inflammatory D. 1. 2. Ankylosing spondylitis Psoriatic and reactive arthritis Crystal deposition disease Gout Calcium pyrophosphate deposition disease (CPPD) IV. Metabolic A. B. Paget disease Renal osteodystrophy and amyloid spondyloarthropathy

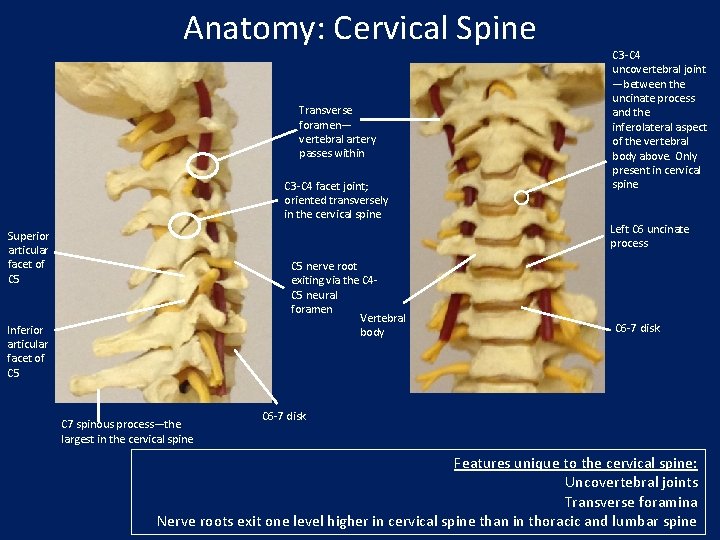

Anatomy: Cervical Spine Transverse foramen— vertebral artery passes within C 3 -C 4 facet joint; oriented transversely in the cervical spine Superior articular facet of C 5 nerve root exiting via the C 4 C 5 neural foramen Vertebral body Inferior articular facet of C 5 C 7 spinous process—the largest in the cervical spine C 3 -C 4 uncovertebral joint —between the uncinate process and the inferolateral aspect of the vertebral body above. Only present in cervical spine Left C 6 uncinate process C 6 -7 disk Features unique to the cervical spine: Uncovertebral joints Transverse foramina Nerve roots exit one level higher in cervical spine than in thoracic and lumbar spine

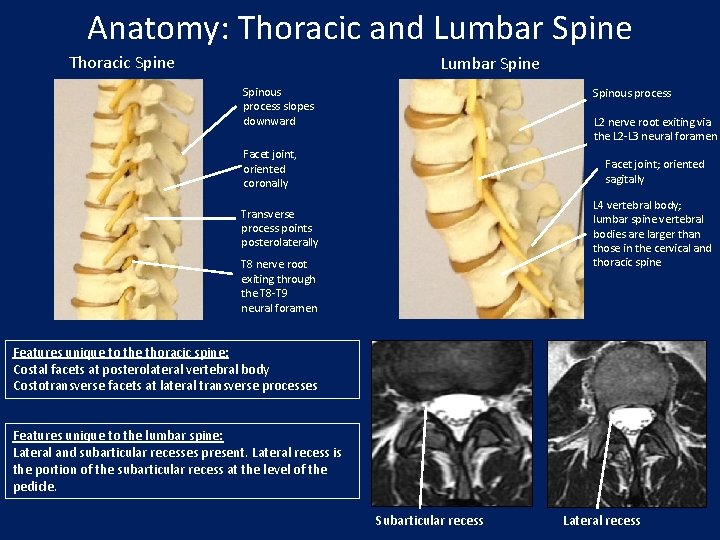

Anatomy: Thoracic and Lumbar Spine Thoracic Spine Lumbar Spine Spinous process slopes downward Spinous process L 2 nerve root exiting via the L 2 -L 3 neural foramen Facet joint, oriented coronally Facet joint; oriented sagitally L 4 vertebral body; lumbar spine vertebral bodies are larger than those in the cervical and thoracic spine Transverse process points posterolaterally T 8 nerve root exiting through the T 8 -T 9 neural foramen Features unique to the thoracic spine: Costal facets at posterolateral vertebral body Costotransverse facets at lateral transverse processes Features unique to the lumbar spine: Lateral and subarticular recesses present. Lateral recess is the portion of the subarticular recess at the level of the pedicle. Subarticular recess Lateral recess

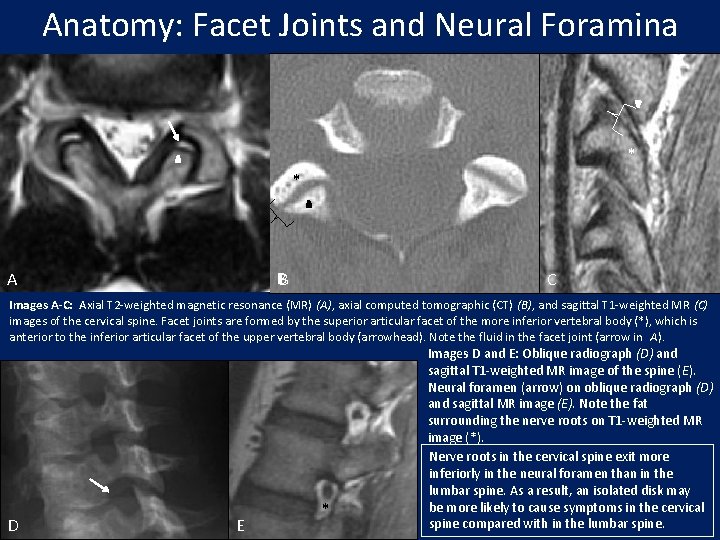

Anatomy: Facet Joints and Neural Foramina * * * B A C Images A-C: Axial T 2 -weighted magnetic resonance (MR) (A), axial computed tomographic (CT) (B), and sagittal T 1 -weighted MR (C) images of the cervical spine. Facet joints are formed by the superior articular facet of the more inferior vertebral body (*), which is anterior to the inferior articular facet of the upper vertebral body (arrowhead). Note the fluid in the facet joint (arrow in A). D E * Images D and E: Oblique radiograph (D) and sagittal T 1 -weighted MR image of the spine (E). Neural foramen (arrow) on oblique radiograph (D) and sagittal MR image (E). Note the fat surrounding the nerve roots on T 1 -weighted MR image (*). Nerve roots in the cervical spine exit more inferiorly in the neural foramen than in the lumbar spine. As a result, an isolated disk may be more likely to cause symptoms in the cervical spine compared with in the lumbar spine.

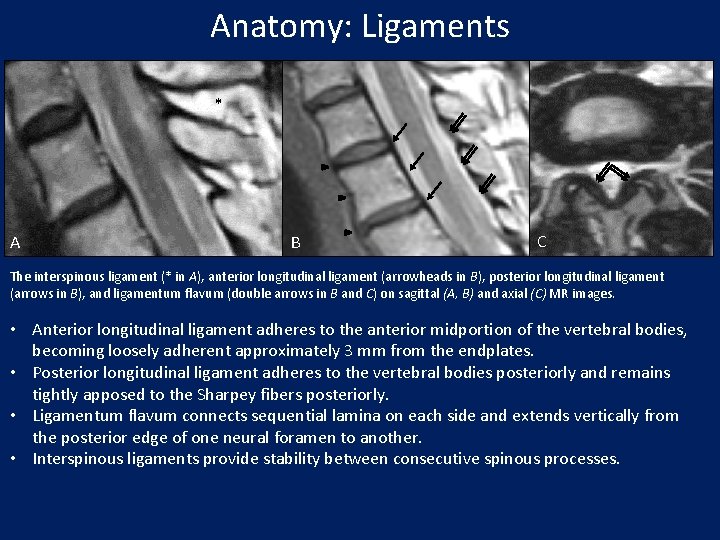

Anatomy: Ligaments * A B C The interspinous ligament (* in A), anterior longitudinal ligament (arrowheads in B), posterior longitudinal ligament (arrows in B), and ligamentum flavum (double arrows in B and C) on sagittal (A, B) and axial (C) MR images. • Anterior longitudinal ligament adheres to the anterior midportion of the vertebral bodies, becoming loosely adherent approximately 3 mm from the endplates. • Posterior longitudinal ligament adheres to the vertebral bodies posteriorly and remains tightly apposed to the Sharpey fibers posteriorly. • Ligamentum flavum connects sequential lamina on each side and extends vertically from the posterior edge of one neural foramen to another. • Interspinous ligaments provide stability between consecutive spinous processes.

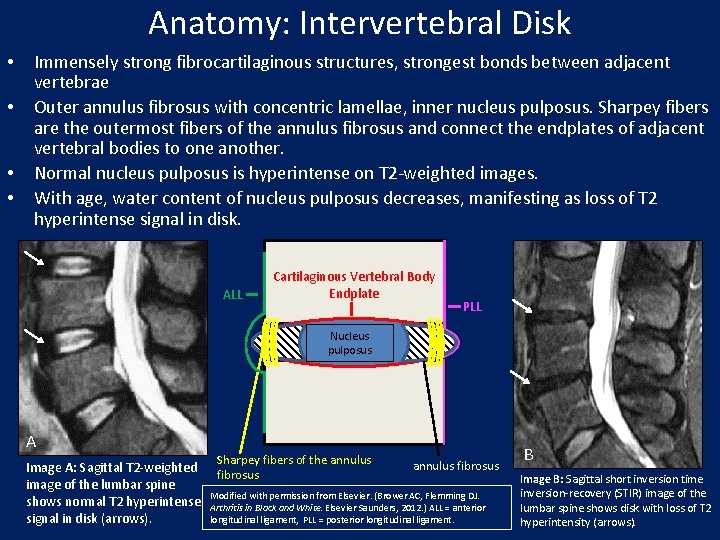

Anatomy: Intervertebral Disk • • Immensely strong fibrocartilaginous structures, strongest bonds between adjacent vertebrae Outer annulus fibrosus with concentric lamellae, inner nucleus pulposus. Sharpey fibers are the outermost fibers of the annulus fibrosus and connect the endplates of adjacent vertebral bodies to one another. Normal nucleus pulposus is hyperintense on T 2 -weighted images. With age, water content of nucleus pulposus decreases, manifesting as loss of T 2 hyperintense signal in disk. ALL Cartilaginous Vertebral Body Endplate PLL Nucleus pulposus A Image A: Sagittal T 2 -weighted image of the lumbar spine shows normal T 2 hyperintense signal in disk (arrows). Sharpey fibers of the annulus fibrosus Modified with permission from Elsevier. (Brower AC, Flemming DJ. Arthritis in Black and White. Elsevier Saunders, 2012. ) ALL = anterior longitudinal ligament, PLL = posterior longitudinal ligament. B Image B: Sagittal short inversion time inversion-recovery (STIR) image of the lumbar spine shows disk with loss of T 2 hyperintensity (arrows).

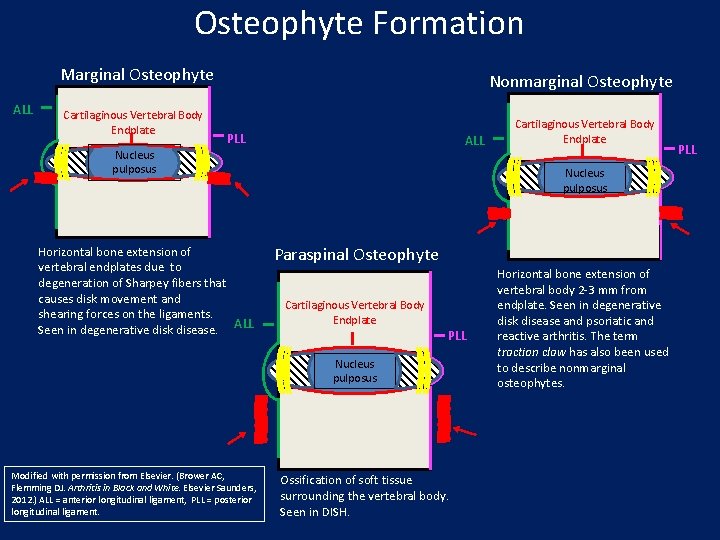

Osteophyte Formation Marginal Osteophyte ALL Cartilaginous Vertebral Body Endplate Nonmarginal Osteophyte PLL ALL Nucleus pulposus Horizontal bone extension of vertebral endplates due to degeneration of Sharpey fibers that causes disk movement and shearing forces on the ligaments. Seen in degenerative disk disease. ALL Nucleus pulposus Paraspinal Osteophyte Cartilaginous Vertebral Body Endplate PLL Nucleus pulposus Modified with permission from Elsevier. (Brower AC, Flemming DJ. Arthritis in Black and White. Elsevier Saunders, 2012. ) ALL = anterior longitudinal ligament, PLL = posterior longitudinal ligament. Cartilaginous Vertebral Body Endplate Ossification of soft tissue surrounding the vertebral body. Seen in DISH. Horizontal bone extension of vertebral body 2 -3 mm from endplate. Seen in degenerative disk disease and psoriatic and reactive arthritis. The term traction claw has also been used to describe nonmarginal osteophytes. PLL

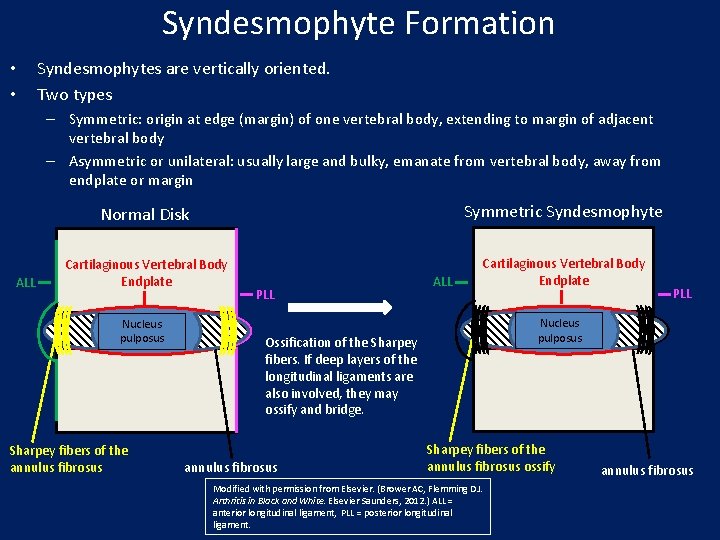

Syndesmophyte Formation • • Syndesmophytes are vertically oriented. Two types – Symmetric: origin at edge (margin) of one vertebral body, extending to margin of adjacent vertebral body – Asymmetric or unilateral: usually large and bulky, emanate from vertebral body, away from endplate or margin ALL Normal Disk Symmetric Syndesmophyte Cartilaginous Vertebral Body Endplate Nucleus pulposus Sharpey fibers of the annulus fibrosus PLL ALL Nucleus pulposus Ossification of the Sharpey fibers. If deep layers of the longitudinal ligaments are also involved, they may ossify and bridge. annulus fibrosus PLL Sharpey fibers of the annulus fibrosus ossify Modified with permission from Elsevier. (Brower AC, Flemming DJ. Arthritis in Black and White. Elsevier Saunders, 2012. ) ALL = anterior longitudinal ligament, PLL = posterior longitudinal ligament. annulus fibrosus

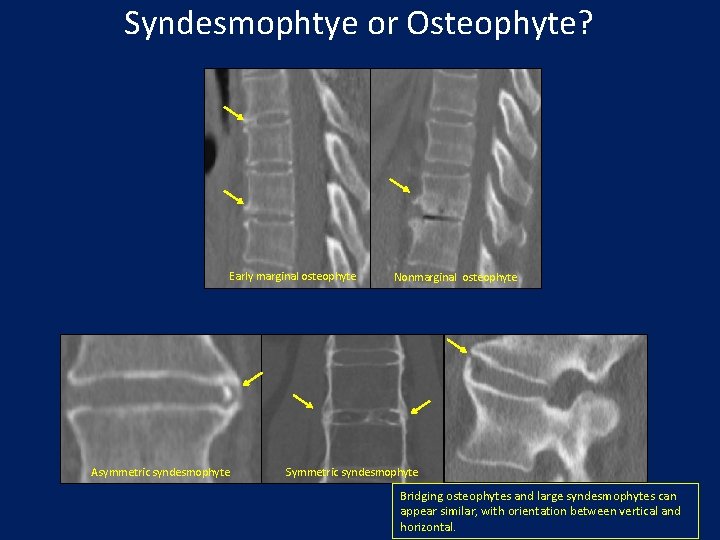

Syndesmophtye or Osteophyte? Early marginal osteophyte Asymmetric syndesmophyte Nonmarginal osteophyte Symmetric syndesmophyte Bridging osteophytes and large syndesmophytes can appear similar, with orientation between vertical and horizontal.

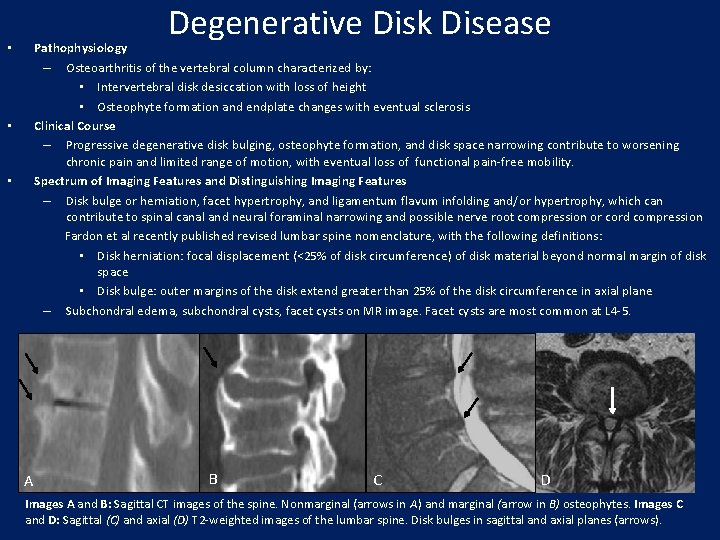

Degenerative Disk Disease Pathophysiology – Osteoarthritis of the vertebral column characterized by: • Intervertebral disk desiccation with loss of height • Osteophyte formation and endplate changes with eventual sclerosis Clinical Course – Progressive degenerative disk bulging, osteophyte formation, and disk space narrowing contribute to worsening chronic pain and limited range of motion, with eventual loss of functional pain-free mobility. Spectrum of Imaging Features and Distinguishing Imaging Features – Disk bulge or herniation, facet hypertrophy, and ligamentum flavum infolding and/or hypertrophy, which can contribute to spinal canal and neural foraminal narrowing and possible nerve root compression or cord compression Fardon et al recently published revised lumbar spine nomenclature, with the following definitions: • Disk herniation: focal displacement (<25% of disk circumference) of disk material beyond normal margin of disk space • Disk bulge: outer margins of the disk extend greater than 25% of the disk circumference in axial plane – Subchondral edema, subchondral cysts, facet cysts on MR image. Facet cysts are most common at L 4 -5. • • • A B C D Images A and B: Sagittal CT images of the spine. Nonmarginal (arrows in A) and marginal (arrow in B) osteophytes. Images C and D: Sagittal (C) and axial (D) T 2 -weighted images of the lumbar spine. Disk bulges in sagittal and axial planes (arrows).

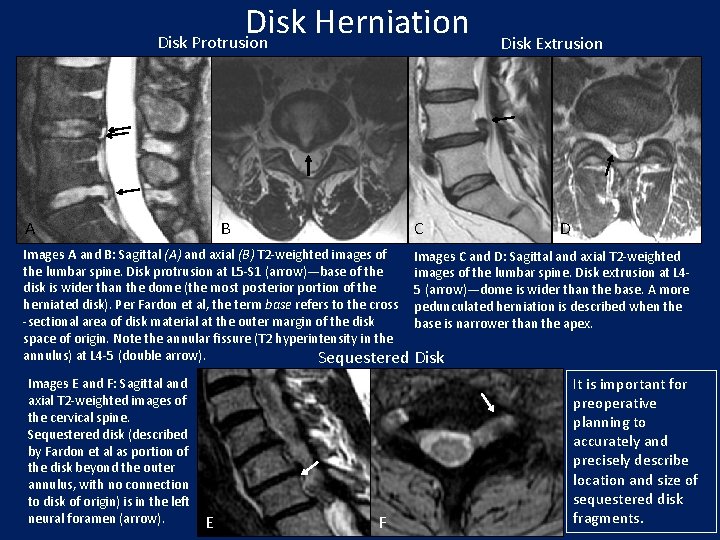

Disk Herniation Disk Protrusion A B C Disk Extrusion D Images A and B: Sagittal (A) and axial (B) T 2 -weighted images of Images C and D: Sagittal and axial T 2 -weighted the lumbar spine. Disk protrusion at L 5 -S 1 (arrow)—base of the images of the lumbar spine. Disk extrusion at L 4 disk is wider than the dome (the most posterior portion of the 5 (arrow)—dome is wider than the base. A more herniated disk). Per Fardon et al, the term base refers to the cross pedunculated herniation is described when the -sectional area of disk material at the outer margin of the disk base is narrower than the apex. space of origin. Note the annular fissure (T 2 hyperintensity in the annulus) at L 4 -5 (double arrow). Sequestered Disk Images E and F: Sagittal and axial T 2 -weighted images of the cervical spine. Sequestered disk (described by Fardon et al as portion of the disk beyond the outer annulus, with no connection to disk of origin) is in the left neural foramen (arrow). E F It is important for preoperative planning to accurately and precisely describe location and size of sequestered disk fragments.

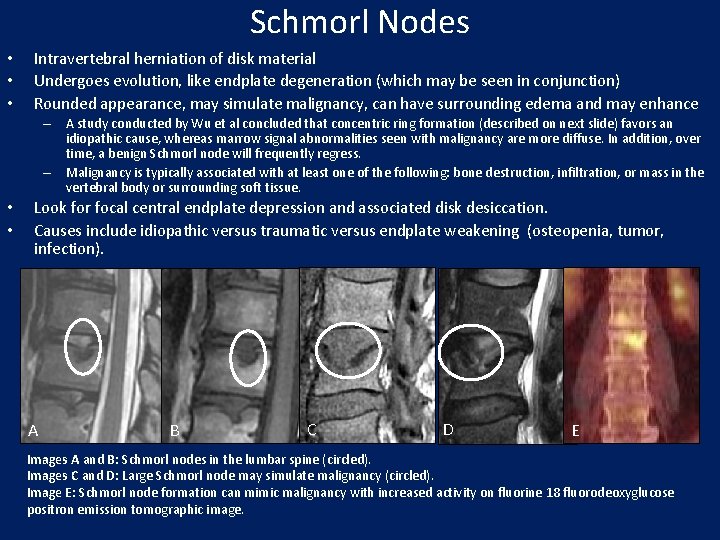

Schmorl Nodes • • • Intravertebral herniation of disk material Undergoes evolution, like endplate degeneration (which may be seen in conjunction) Rounded appearance, may simulate malignancy, can have surrounding edema and may enhance – A study conducted by Wu et al concluded that concentric ring formation (described on next slide) favors an idiopathic cause, whereas marrow signal abnormalities seen with malignancy are more diffuse. In addition, over time, a benign Schmorl node will frequently regress. – Malignancy is typically associated with at least one of the following: bone destruction, infiltration, or mass in the vertebral body or surrounding soft tissue. • • Look for focal central endplate depression and associated disk desiccation. Causes include idiopathic versus traumatic versus endplate weakening (osteopenia, tumor, infection). A B C D E Images A and B: Schmorl nodes in the lumbar spine (circled). Images C and D: Large Schmorl node may simulate malignancy (circled). Image E: Schmorl node formation can mimic malignancy with increased activity on fluorine 18 fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomographic image.

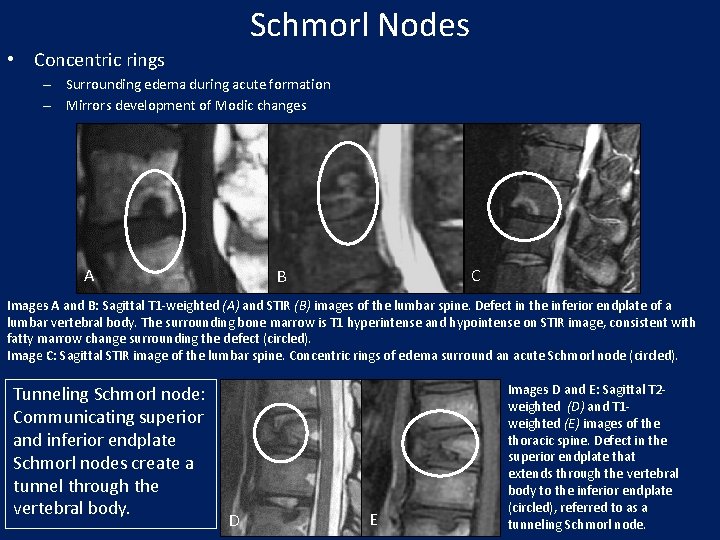

Schmorl Nodes • Concentric rings – Surrounding edema during acute formation – Mirrors development of Modic changes A C B Images A and B: Sagittal T 1 -weighted (A) and STIR (B) images of the lumbar spine. Defect in the inferior endplate of a lumbar vertebral body. The surrounding bone marrow is T 1 hyperintense and hypointense on STIR image, consistent with fatty marrow change surrounding the defect (circled). Image C: Sagittal STIR image of the lumbar spine. Concentric rings of edema surround an acute Schmorl node (circled). Tunneling Schmorl node: Communicating superior and inferior endplate Schmorl nodes create a tunnel through the vertebral body. D E Images D and E: Sagittal T 2 weighted (D) and T 1 weighted (E) images of the thoracic spine. Defect in the superior endplate that extends through the vertebral body to the inferior endplate (circled), referred to as a tunneling Schmorl node.

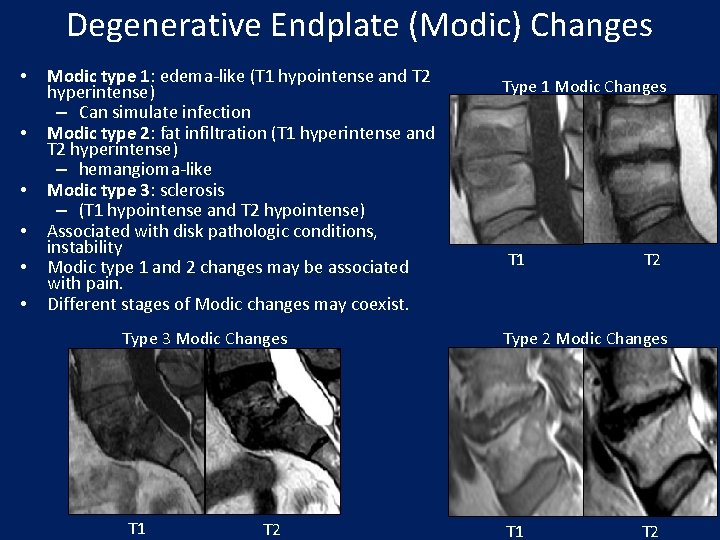

Degenerative Endplate (Modic) Changes • • • Modic type 1: edema-like (T 1 hypointense and T 2 hyperintense) – Can simulate infection Modic type 2: fat infiltration (T 1 hyperintense and T 2 hyperintense) – hemangioma-like Modic type 3: sclerosis – (T 1 hypointense and T 2 hypointense) Associated with disk pathologic conditions, instability Modic type 1 and 2 changes may be associated with pain. Different stages of Modic changes may coexist. Type 3 Modic Changes T 1 T 2 Type 1 Modic Changes T 1 T 2 Type 2 Modic Changes T 1 T 2

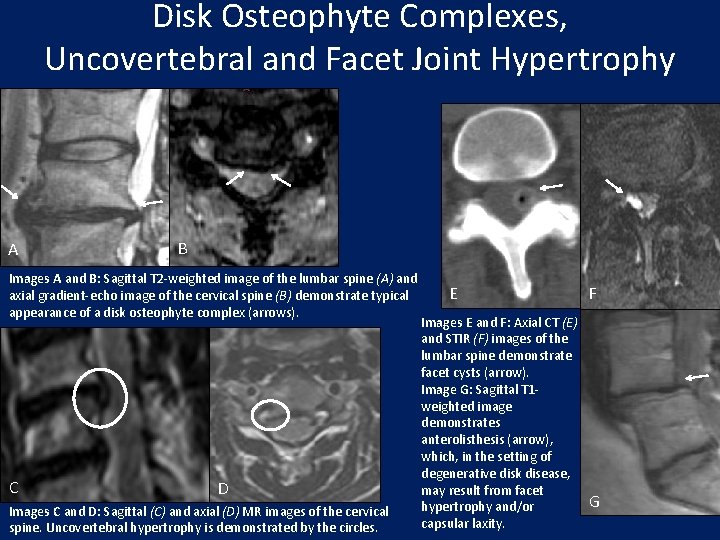

Disk Osteophyte Complexes, Uncovertebral and Facet Joint Hypertrophy A B Images A and B: Sagittal T 2 -weighted image of the lumbar spine (A) and axial gradient-echo image of the cervical spine (B) demonstrate typical appearance of a disk osteophyte complex (arrows). C D Images C and D: Sagittal (C) and axial (D) MR images of the cervical spine. Uncovertebral hypertrophy is demonstrated by the circles. E Images E and F: Axial CT (E) and STIR (F) images of the lumbar spine demonstrate facet cysts (arrow). Image G: Sagittal T 1 weighted image demonstrates anterolisthesis (arrow), which, in the setting of degenerative disk disease, may result from facet hypertrophy and/or capsular laxity. F G

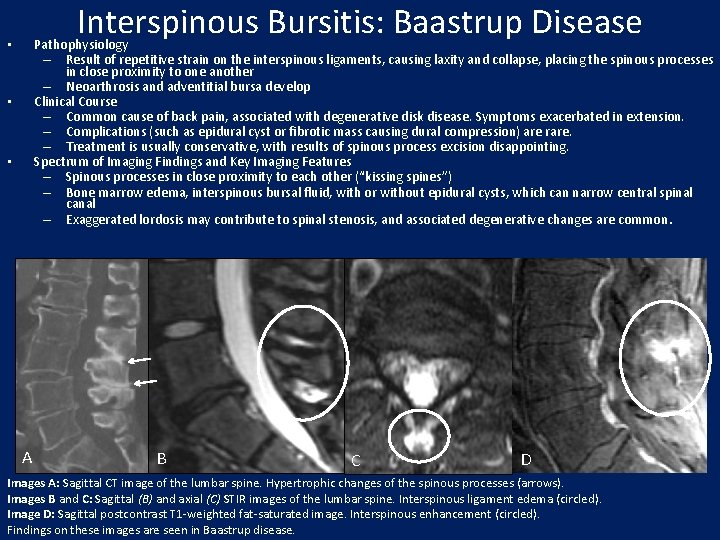

Interspinous Bursitis: Baastrup Disease Pathophysiology – Result of repetitive strain on the interspinous ligaments, causing laxity and collapse, placing the spinous processes in close proximity to one another – Neoarthrosis and adventitial bursa develop Clinical Course – Common cause of back pain, associated with degenerative disk disease. Symptoms exacerbated in extension. – Complications (such as epidural cyst or fibrotic mass causing dural compression) are rare. – Treatment is usually conservative, with results of spinous process excision disappointing. Spectrum of Imaging Findings and Key Imaging Features – Spinous processes in close proximity to each other (“kissing spines”) – Bone marrow edema, interspinous bursal fluid, with or without epidural cysts, which can narrow central spinal canal – Exaggerated lordosis may contribute to spinal stenosis, and associated degenerative changes are common. • • • A B C D Images A: Sagittal CT image of the lumbar spine. Hypertrophic changes of the spinous processes (arrows). Images B and C: Sagittal (B) and axial (C) STIR images of the lumbar spine. Interspinous ligament edema (circled). Image D: Sagittal postcontrast T 1 -weighted fat-saturated image. Interspinous enhancement (circled). Findings on these images are seen in Baastrup disease.

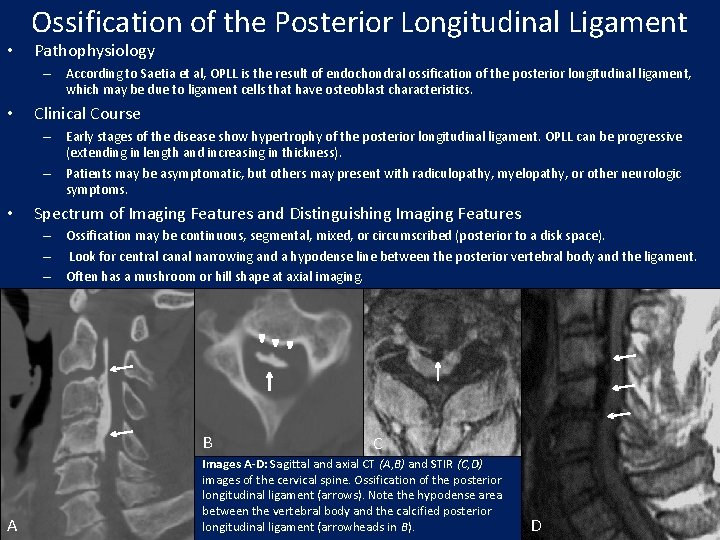

• Ossification of the Posterior Longitudinal Ligament Pathophysiology – According to Saetia et al, OPLL is the result of endochondral ossification of the posterior longitudinal ligament, which may be due to ligament cells that have osteoblast characteristics. • Clinical Course – Early stages of the disease show hypertrophy of the posterior longitudinal ligament. OPLL can be progressive (extending in length and increasing in thickness). – Patients may be asymptomatic, but others may present with radiculopathy, myelopathy, or other neurologic symptoms. • Spectrum of Imaging Features and Distinguishing Imaging Features – Ossification may be continuous, segmental, mixed, or circumscribed (posterior to a disk space). – Look for central canal narrowing and a hypodense line between the posterior vertebral body and the ligament. – Often has a mushroom or hill shape at axial imaging. B A C Images A-D: Sagittal and axial CT (A, B) and STIR (C, D) images of the cervical spine. Ossification of the posterior longitudinal ligament (arrows). Note the hypodense area between the vertebral body and the calcified posterior longitudinal ligament (arrowheads in B). D

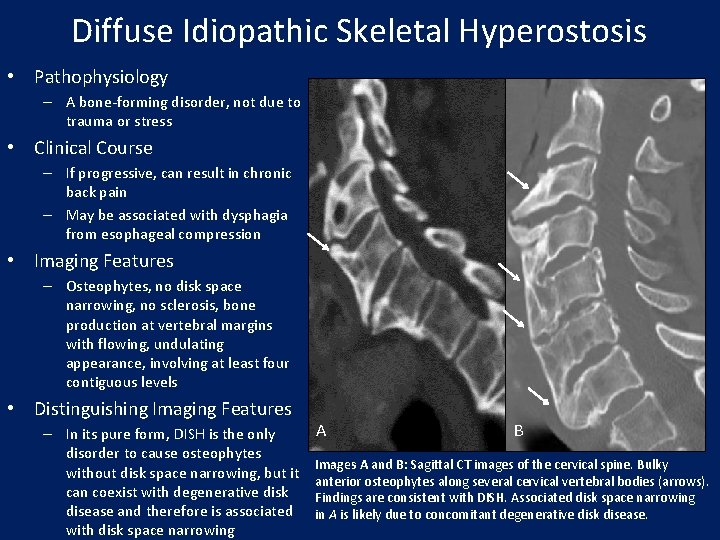

Diffuse Idiopathic Skeletal Hyperostosis • Pathophysiology – A bone-forming disorder, not due to trauma or stress • Clinical Course – If progressive, can result in chronic back pain – May be associated with dysphagia from esophageal compression • Imaging Features – Osteophytes, no disk space narrowing, no sclerosis, bone production at vertebral margins with flowing, undulating appearance, involving at least four contiguous levels • Distinguishing Imaging Features – In its pure form, DISH is the only disorder to cause osteophytes without disk space narrowing, but it can coexist with degenerative disk disease and therefore is associated with disk space narrowing A B Images A and B: Sagittal CT images of the cervical spine. Bulky anterior osteophytes along several cervical vertebral bodies (arrows). Findings are consistent with DISH. Associated disk space narrowing in A is likely due to concomitant degenerative disk disease.

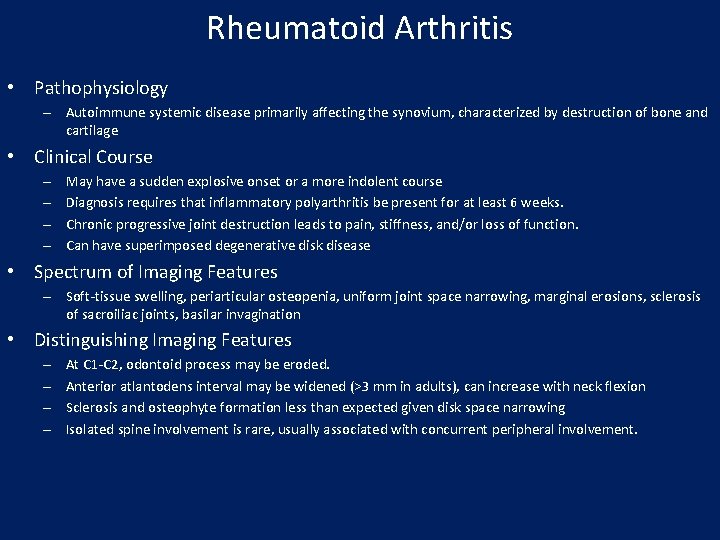

Rheumatoid Arthritis • Pathophysiology – Autoimmune systemic disease primarily affecting the synovium, characterized by destruction of bone and cartilage • Clinical Course – – May have a sudden explosive onset or a more indolent course Diagnosis requires that inflammatory polyarthritis be present for at least 6 weeks. Chronic progressive joint destruction leads to pain, stiffness, and/or loss of function. Can have superimposed degenerative disk disease • Spectrum of Imaging Features – Soft-tissue swelling, periarticular osteopenia, uniform joint space narrowing, marginal erosions, sclerosis of sacroiliac joints, basilar invagination • Distinguishing Imaging Features – – At C 1 -C 2, odontoid process may be eroded. Anterior atlantodens interval may be widened (>3 mm in adults), can increase with neck flexion Sclerosis and osteophyte formation less than expected given disk space narrowing Isolated spine involvement is rare, usually associated with concurrent peripheral involvement.

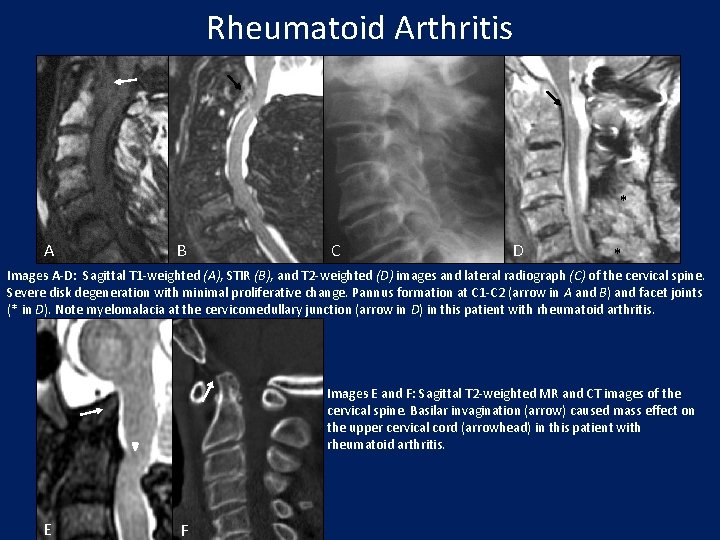

Rheumatoid Arthritis * A B C D * Images A-D: Sagittal T 1 -weighted (A), STIR (B), and T 2 -weighted (D) images and lateral radiograph (C) of the cervical spine. Severe disk degeneration with minimal proliferative change. Pannus formation at C 1 -C 2 (arrow in A and B) and facet joints (* in D). Note myelomalacia at the cervicomedullary junction (arrow in D) in this patient with rheumatoid arthritis. Images E and F: Sagittal T 2 -weighted MR and CT images of the cervical spine. Basilar invagination (arrow) caused mass effect on the upper cervical cord (arrowhead) in this patient with rheumatoid arthritis. E F

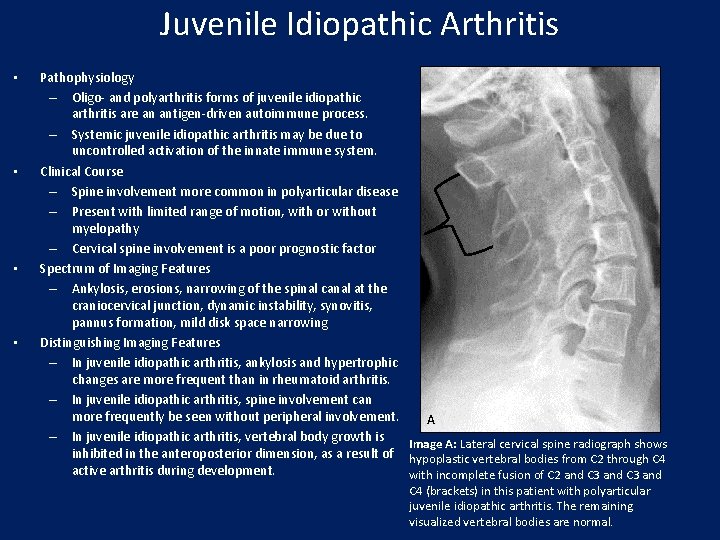

Juvenile Idiopathic Arthritis • • Pathophysiology – Oligo- and polyarthritis forms of juvenile idiopathic arthritis are an antigen-driven autoimmune process. – Systemic juvenile idiopathic arthritis may be due to uncontrolled activation of the innate immune system. Clinical Course – Spine involvement more common in polyarticular disease – Present with limited range of motion, with or without myelopathy – Cervical spine involvement is a poor prognostic factor Spectrum of Imaging Features – Ankylosis, erosions, narrowing of the spinal canal at the craniocervical junction, dynamic instability, synovitis, pannus formation, mild disk space narrowing Distinguishing Imaging Features – In juvenile idiopathic arthritis, ankylosis and hypertrophic changes are more frequent than in rheumatoid arthritis. – In juvenile idiopathic arthritis, spine involvement can more frequently be seen without peripheral involvement. A – In juvenile idiopathic arthritis, vertebral body growth is Image A: Lateral cervical spine radiograph shows inhibited in the anteroposterior dimension, as a result of hypoplastic vertebral bodies from C 2 through C 4 active arthritis during development. with incomplete fusion of C 2 and C 3 and C 4 (brackets) in this patient with polyarticular juvenile idiopathic arthritis. The remaining visualized vertebral bodies are normal.

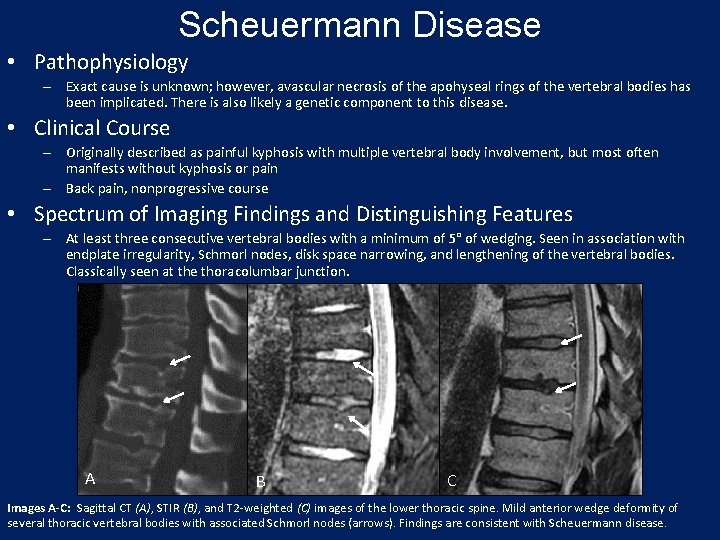

Scheuermann Disease • Pathophysiology – Exact cause is unknown; however, avascular necrosis of the apohyseal rings of the vertebral bodies has been implicated. There is also likely a genetic component to this disease. • Clinical Course – Originally described as painful kyphosis with multiple vertebral body involvement, but most often manifests without kyphosis or pain – Back pain, nonprogressive course • Spectrum of Imaging Findings and Distinguishing Features – At least three consecutive vertebral bodies with a minimum of 5° of wedging. Seen in association with endplate irregularity, Schmorl nodes, disk space narrowing, and lengthening of the vertebral bodies. Classically seen at the thoracolumbar junction. A B C Images A-C: Sagittal CT (A), STIR (B), and T 2 -weighted (C) images of the lower thoracic spine. Mild anterior wedge deformity of several thoracic vertebral bodies with associated Schmorl nodes (arrows). Findings are consistent with Scheuermann disease.

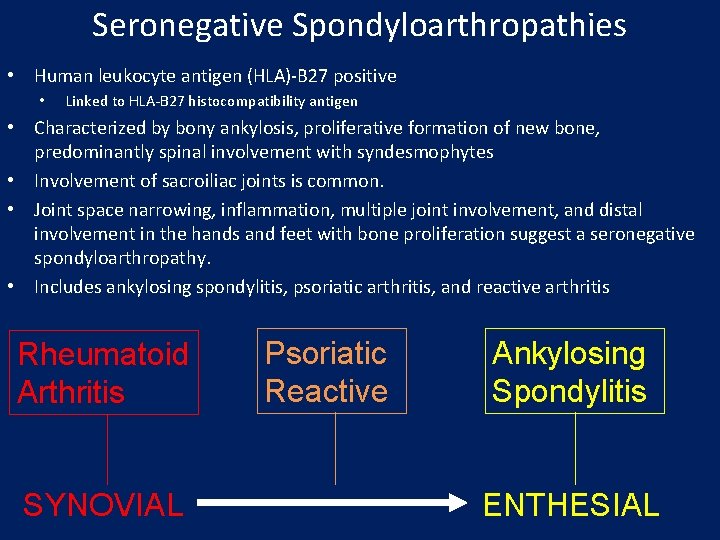

Seronegative Spondyloarthropathies • Human leukocyte antigen (HLA)-B 27 positive • Linked to HLA-B 27 histocompatibility antigen • Characterized by bony ankylosis, proliferative formation of new bone, predominantly spinal involvement with syndesmophytes • Involvement of sacroiliac joints is common. • Joint space narrowing, inflammation, multiple joint involvement, and distal involvement in the hands and feet with bone proliferation suggest a seronegative spondyloarthropathy. • Includes ankylosing spondylitis, psoriatic arthritis, and reactive arthritis Rheumatoid Arthritis SYNOVIAL Psoriatic Reactive Ankylosing Spondylitis ENTHESIAL

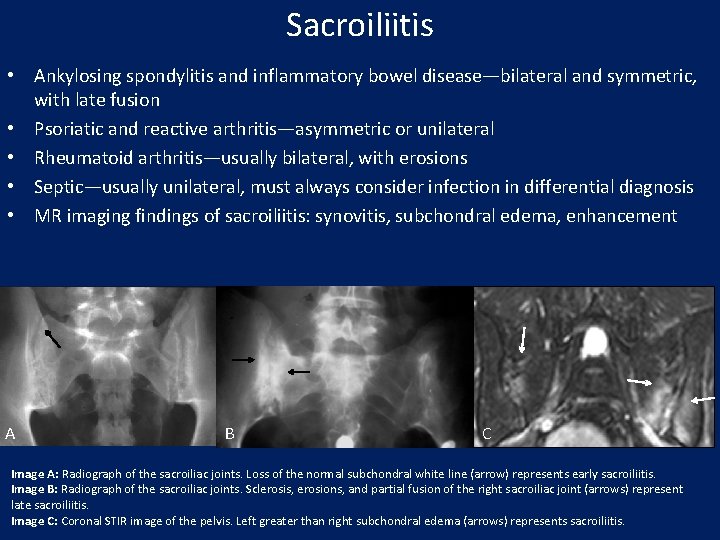

Sacroiliitis • Ankylosing spondylitis and inflammatory bowel disease—bilateral and symmetric, with late fusion • Psoriatic and reactive arthritis—asymmetric or unilateral • Rheumatoid arthritis—usually bilateral, with erosions • Septic—usually unilateral, must always consider infection in differential diagnosis • MR imaging findings of sacroiliitis: synovitis, subchondral edema, enhancement A B C Image A: Radiograph of the sacroiliac joints. Loss of the normal subchondral white line (arrow) represents early sacroiliitis. Image B: Radiograph of the sacroiliac joints. Sclerosis, erosions, and partial fusion of the right sacroiliac joint (arrows) represent late sacroiliitis. Image C: Coronal STIR image of the pelvis. Left greater than right subchondral edema (arrows) represents sacroiliitis.

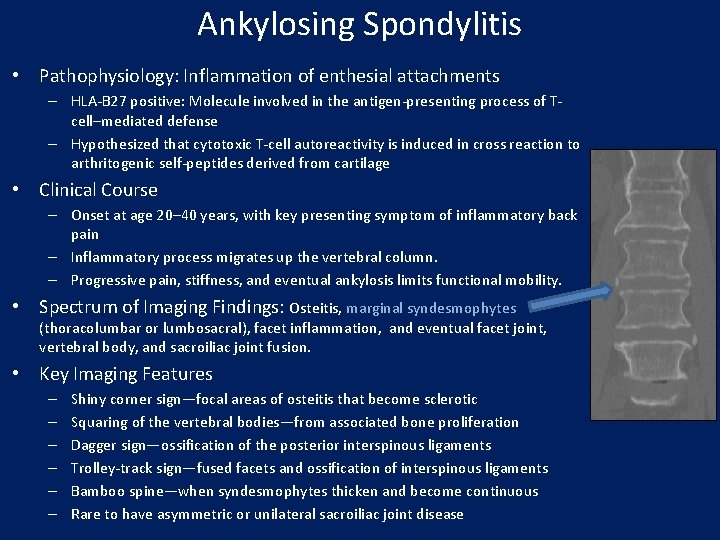

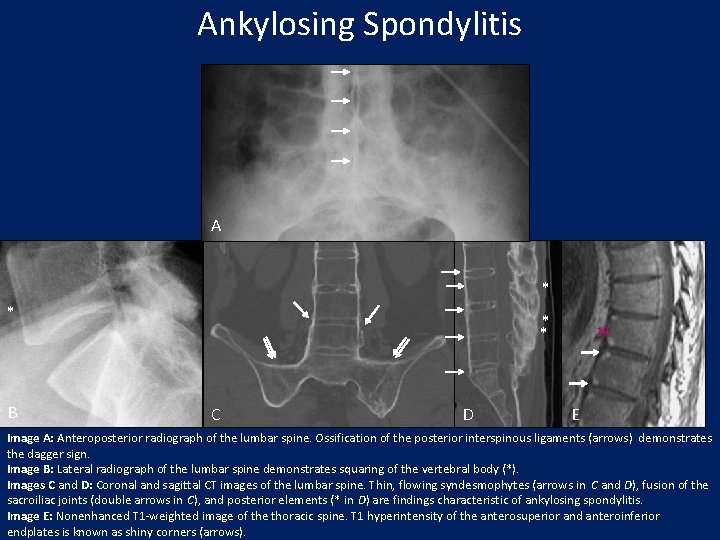

Ankylosing Spondylitis • Pathophysiology: Inflammation of enthesial attachments – HLA-B 27 positive: Molecule involved in the antigen-presenting process of Tcell–mediated defense – Hypothesized that cytotoxic T-cell autoreactivity is induced in cross reaction to arthritogenic self-peptides derived from cartilage • Clinical Course – Onset at age 20– 40 years, with key presenting symptom of inflammatory back pain – Inflammatory process migrates up the vertebral column. – Progressive pain, stiffness, and eventual ankylosis limits functional mobility. • Spectrum of Imaging Findings: Osteitis, marginal syndesmophytes (thoracolumbar or lumbosacral), facet inflammation, and eventual facet joint, vertebral body, and sacroiliac joint fusion. • Key Imaging Features – – – Shiny corner sign—focal areas of osteitis that become sclerotic Squaring of the vertebral bodies—from associated bone proliferation Dagger sign—ossification of the posterior interspinous ligaments Trolley-track sign—fused facets and ossification of interspinous ligaments Bamboo spine—when syndesmophytes thicken and become continuous Rare to have asymmetric or unilateral sacroiliac joint disease

Ankylosing Spondylitis A * * B * * C D E Image A: Anteroposterior radiograph of the lumbar spine. Ossification of the posterior interspinous ligaments (arrows) demonstrates the dagger sign. Image B: Lateral radiograph of the lumbar spine demonstrates squaring of the vertebral body (*). Images C and D: Coronal and sagittal CT images of the lumbar spine. Thin, flowing syndesmophytes (arrows in C and D), fusion of the sacroiliac joints (double arrows in C), and posterior elements (* in D) are findings characteristic of ankylosing spondylitis. Image E: Nonenhanced T 1 -weighted image of the thoracic spine. T 1 hyperintensity of the anterosuperior and anteroinferior endplates is known as shiny corners (arrows).

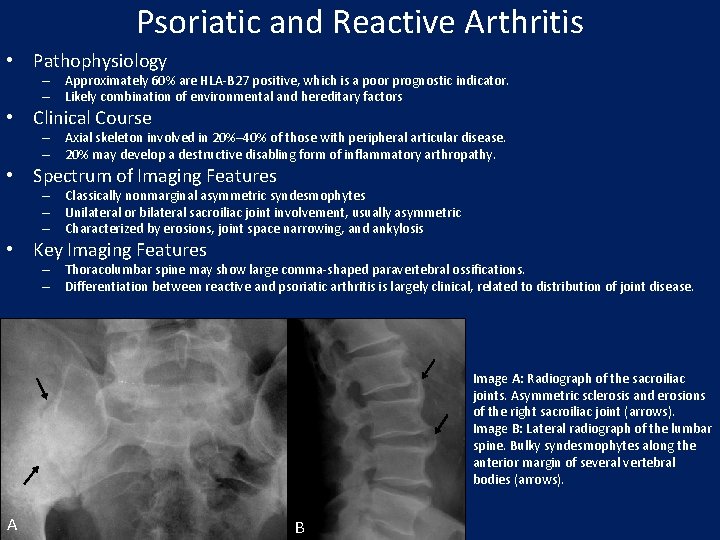

Psoriatic and Reactive Arthritis • Pathophysiology – Approximately 60% are HLA-B 27 positive, which is a poor prognostic indicator. – Likely combination of environmental and hereditary factors • Clinical Course – Axial skeleton involved in 20%– 40% of those with peripheral articular disease. – 20% may develop a destructive disabling form of inflammatory arthropathy. • Spectrum of Imaging Features – Classically nonmarginal asymmetric syndesmophytes – Unilateral or bilateral sacroiliac joint involvement, usually asymmetric – Characterized by erosions, joint space narrowing, and ankylosis • Key Imaging Features – Thoracolumbar spine may show large comma-shaped paravertebral ossifications. – Differentiation between reactive and psoriatic arthritis is largely clinical, related to distribution of joint disease. Image A: Radiograph of the sacroiliac joints. Asymmetric sclerosis and erosions of the right sacroiliac joint (arrows). Image B: Lateral radiograph of the lumbar spine. Bulky syndesmophytes along the anterior margin of several vertebral bodies (arrows). A B

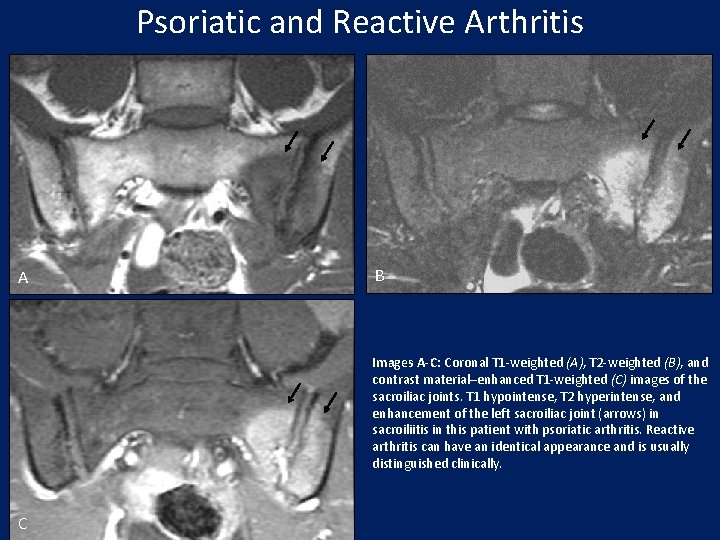

Psoriatic and Reactive Arthritis A B Images A-C: Coronal T 1 -weighted (A), T 2 -weighted (B), and contrast material–enhanced T 1 -weighted (C) images of the sacroiliac joints. T 1 hypointense, T 2 hyperintense, and enhancement of the left sacroiliac joint (arrows) in sacroiliitis in this patient with psoriatic arthritis. Reactive arthritis can have an identical appearance and is usually distinguished clinically. C

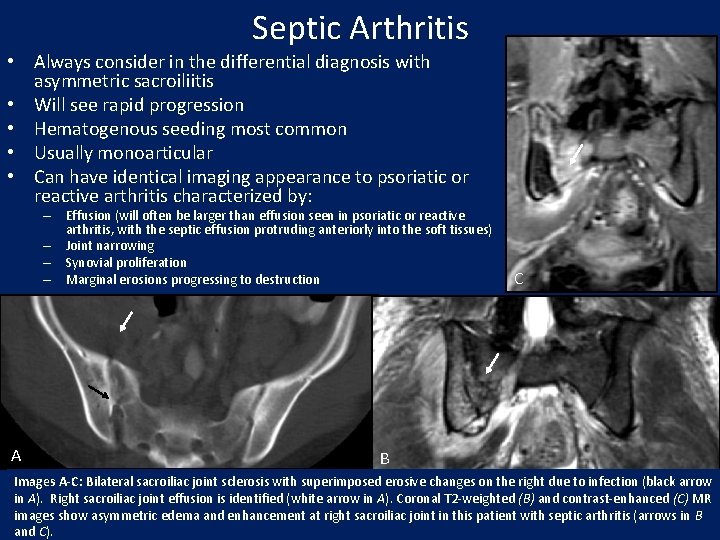

Septic Arthritis • Always consider in the differential diagnosis with asymmetric sacroiliitis • Will see rapid progression • Hematogenous seeding most common • Usually monoarticular • Can have identical imaging appearance to psoriatic or reactive arthritis characterized by: – Effusion (will often be larger than effusion seen in psoriatic or reactive arthritis, with the septic effusion protruding anteriorly into the soft tissues) – Joint narrowing – Synovial proliferation – Marginal erosions progressing to destruction A C B Images A-C: Bilateral sacroiliac joint sclerosis with superimposed erosive changes on the right due to infection (black arrow in A). Right sacroiliac joint effusion is identified (white arrow in A). Coronal T 2 -weighted (B) and contrast-enhanced (C) MR images show asymmetric edema and enhancement at right sacroiliac joint in this patient with septic arthritis (arrows in B and C).

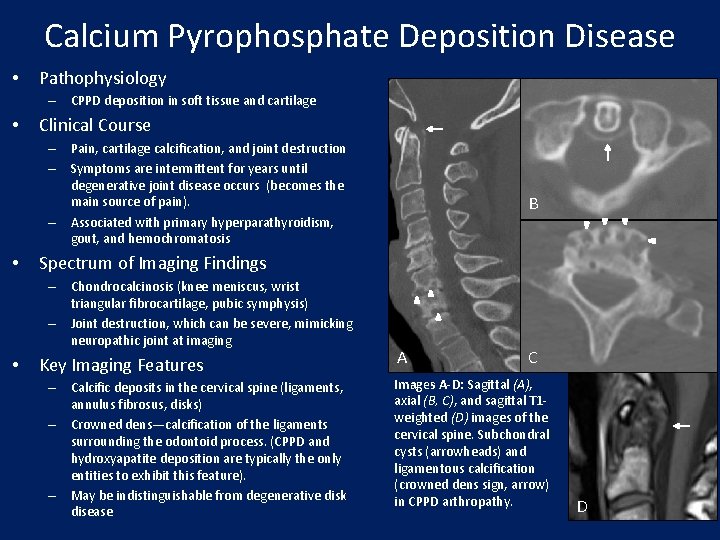

Calcium Pyrophosphate Deposition Disease • Pathophysiology – CPPD deposition in soft tissue and cartilage • Clinical Course – Pain, cartilage calcification, and joint destruction – Symptoms are intermittent for years until degenerative joint disease occurs (becomes the main source of pain). – Associated with primary hyperparathyroidism, gout, and hemochromatosis • Spectrum of Imaging Findings – Chondrocalcinosis (knee meniscus, wrist triangular fibrocartilage, pubic symphysis) – Joint destruction, which can be severe, mimicking neuropathic joint at imaging • B Key Imaging Features – Calcific deposits in the cervical spine (ligaments, annulus fibrosus, disks) – Crowned dens—calcification of the ligaments surrounding the odontoid process. (CPPD and hydroxyapatite deposition are typically the only entities to exhibit this feature). – May be indistinguishable from degenerative disk disease A C Images A-D: Sagittal (A), axial (B, C), and sagittal T 1 weighted (D) images of the cervical spine. Subchondral cysts (arrowheads) and ligamentous calcification (crowned dens sign, arrow) in CPPD arthropathy. D

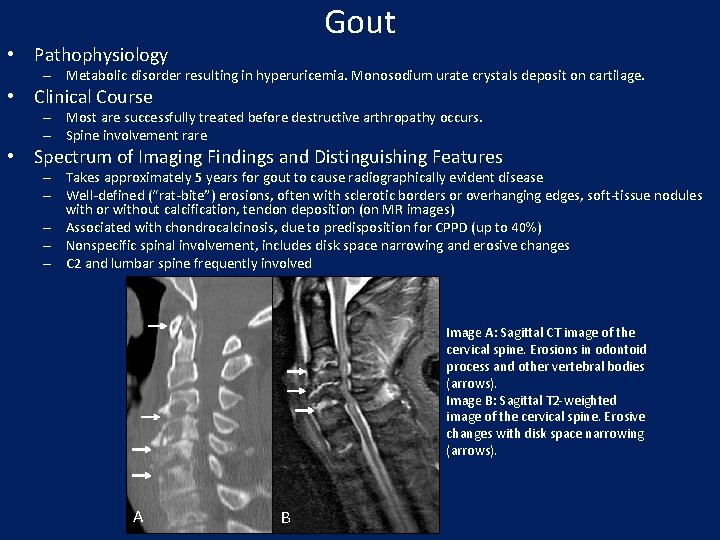

Gout • Pathophysiology – Metabolic disorder resulting in hyperuricemia. Monosodium urate crystals deposit on cartilage. • Clinical Course – Most are successfully treated before destructive arthropathy occurs. – Spine involvement rare • Spectrum of Imaging Findings and Distinguishing Features – Takes approximately 5 years for gout to cause radiographically evident disease – Well-defined (“rat-bite”) erosions, often with sclerotic borders or overhanging edges, soft-tissue nodules with or without calcification, tendon deposition (on MR images) – Associated with chondrocalcinosis, due to predisposition for CPPD (up to 40%) – Nonspecific spinal involvement, includes disk space narrowing and erosive changes – C 2 and lumbar spine frequently involved Image A: Sagittal CT image of the cervical spine. Erosions in odontoid process and other vertebral bodies (arrows). Image B: Sagittal T 2 -weighted image of the cervical spine. Erosive changes with disk space narrowing (arrows). A B

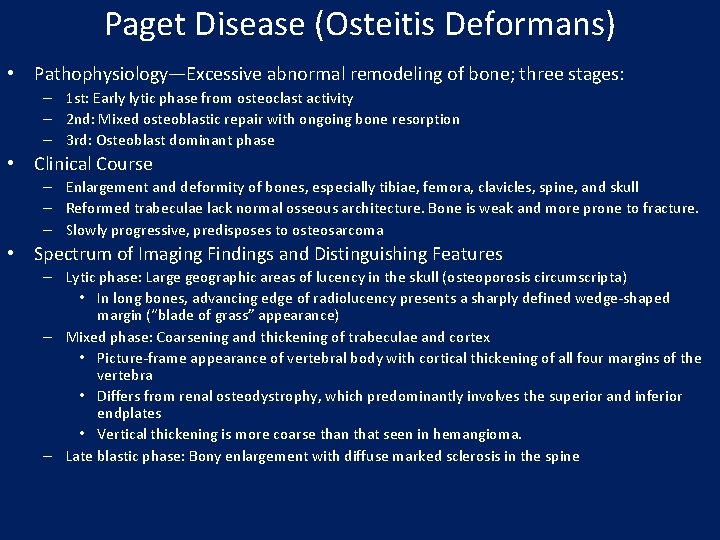

Paget Disease (Osteitis Deformans) • Pathophysiology—Excessive abnormal remodeling of bone; three stages: – 1 st: Early lytic phase from osteoclast activity – 2 nd: Mixed osteoblastic repair with ongoing bone resorption – 3 rd: Osteoblast dominant phase • Clinical Course – Enlargement and deformity of bones, especially tibiae, femora, clavicles, spine, and skull – Reformed trabeculae lack normal osseous architecture. Bone is weak and more prone to fracture. – Slowly progressive, predisposes to osteosarcoma • Spectrum of Imaging Findings and Distinguishing Features – Lytic phase: Large geographic areas of lucency in the skull (osteoporosis circumscripta) • In long bones, advancing edge of radiolucency presents a sharply defined wedge-shaped margin (“blade of grass” appearance) – Mixed phase: Coarsening and thickening of trabeculae and cortex • Picture-frame appearance of vertebral body with cortical thickening of all four margins of the vertebra • Differs from renal osteodystrophy, which predominantly involves the superior and inferior endplates • Vertical thickening is more coarse than that seen in hemangioma. – Late blastic phase: Bony enlargement with diffuse marked sclerosis in the spine

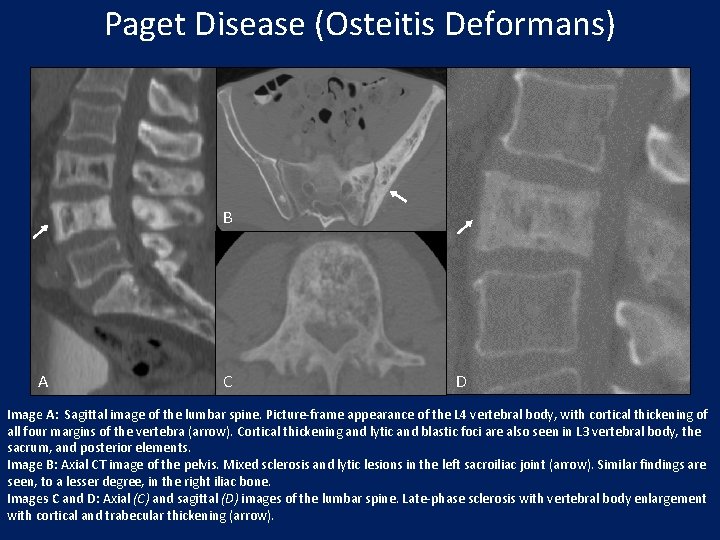

Paget Disease (Osteitis Deformans) B A C D Image A: Sagittal image of the lumbar spine. Picture-frame appearance of the L 4 vertebral body, with cortical thickening of all four margins of the vertebra (arrow). Cortical thickening and lytic and blastic foci are also seen in L 3 vertebral body, the sacrum, and posterior elements. Image B: Axial CT image of the pelvis. Mixed sclerosis and lytic lesions in the left sacroiliac joint (arrow). Similar findings are seen, to a lesser degree, in the right iliac bone. Images C and D: Axial (C) and sagittal (D) images of the lumbar spine. Late-phase sclerosis with vertebral body enlargement with cortical and trabecular thickening (arrow).

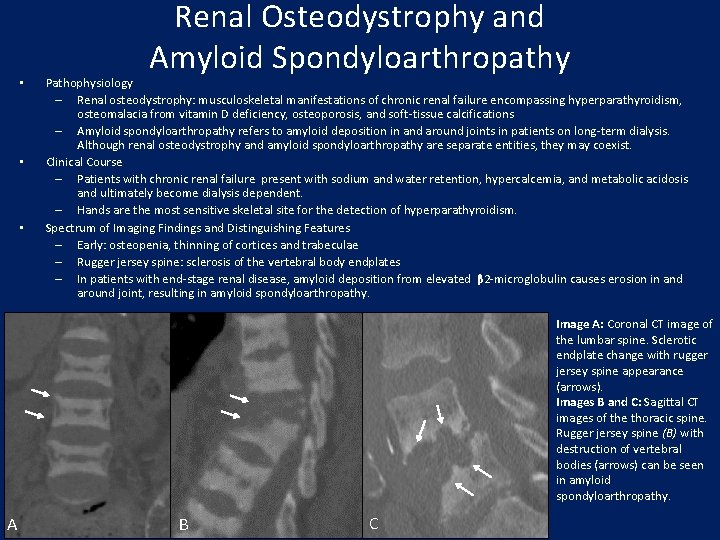

• • • Renal Osteodystrophy and Amyloid Spondyloarthropathy Pathophysiology – Renal osteodystrophy: musculoskeletal manifestations of chronic renal failure encompassing hyperparathyroidism, osteomalacia from vitamin D deficiency, osteoporosis, and soft-tissue calcifications – Amyloid spondyloarthropathy refers to amyloid deposition in and around joints in patients on long-term dialysis. Although renal osteodystrophy and amyloid spondyloarthropathy are separate entities, they may coexist. Clinical Course – Patients with chronic renal failure present with sodium and water retention, hypercalcemia, and metabolic acidosis and ultimately become dialysis dependent. – Hands are the most sensitive skeletal site for the detection of hyperparathyroidism. Spectrum of Imaging Findings and Distinguishing Features – Early: osteopenia, thinning of cortices and trabeculae – Rugger jersey spine: sclerosis of the vertebral body endplates – In patients with end-stage renal disease, amyloid deposition from elevated β 2 -microglobulin causes erosion in and around joint, resulting in amyloid spondyloarthropathy. Image A: Coronal CT image of the lumbar spine. Sclerotic endplate change with rugger jersey spine appearance (arrows). Images B and C: Sagittal CT images of the thoracic spine. Rugger jersey spine (B) with destruction of vertebral bodies (arrows) can be seen in amyloid spondyloarthropathy. A B C

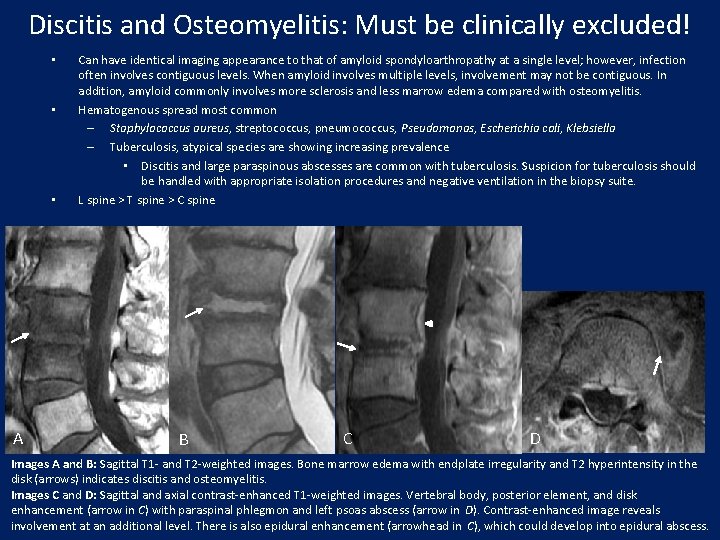

Discitis and Osteomyelitis: Must be clinically excluded! • • • A Can have identical imaging appearance to that of amyloid spondyloarthropathy at a single level; however, infection often involves contiguous levels. When amyloid involves multiple levels, involvement may not be contiguous. In addition, amyloid commonly involves more sclerosis and less marrow edema compared with osteomyelitis. Hematogenous spread most common – Staphylococcus aureus, streptococcus, pneumococcus, Pseudomonas, Escherichia coli, Klebsiella – Tuberculosis, atypical species are showing increasing prevalence • Discitis and large paraspinous abscesses are common with tuberculosis. Suspicion for tuberculosis should be handled with appropriate isolation procedures and negative ventilation in the biopsy suite. L spine > T spine > C spine B C D Images A and B: Sagittal T 1 - and T 2 -weighted images. Bone marrow edema with endplate irregularity and T 2 hyperintensity in the disk (arrows) indicates discitis and osteomyelitis. Images C and D: Sagittal and axial contrast-enhanced T 1 -weighted images. Vertebral body, posterior element, and disk enhancement (arrow in C) with paraspinal phlegmon and left psoas abscess (arrow in D). Contrast-enhanced image reveals involvement at an additional level. There is also epidural enhancement (arrowhead in C), which could develop into epidural abscess.

Summary • • Hallmarks of degenerative disk disease include disk height narrowing and desiccation, osteophyte formation, and endplate changes. Osteophytes in degenerative disk disease are horizontal bone extensions from vertebral body endplates, whereas syndesmophytes in inflammatory arthropathy are due to ossification of Sharpey fibers. DISH, in its pure form, is the only disorder to produce osteophytes without disk space narrowing. Rheumatoid arthritis, an autoimmune disease primarily affecting the synovium, is characterized by periarticular osteopenia, uniform joint space narrowing, marginal erosions, and soft-tissue swelling. Characteristics specific to the spine include basilar invagination and sclerosis of the sacroiliac joints. Psoriatic arthritis manifests in the spine with nonmarginal asymmetric syndesmophytes and unilateral or asymmetric bilateral sacroiliac joint involvement. Ankylosing spondylitis, an HLA-B 27 positive spondyloarthopathy theorized to be mediated by cytotoxic T-cell autoreactivity, is characterized by symmetric sacroiliitis, with the inflammatory process migrating up the spinal column. Crowned dens appearance is typically seen only in CPPD arthropathy and hydroxyapatite deposition. Examining other joints will aid in determining cause. Amyloid spondyloarthropathy and discitis and/or osteomyelitis can be indistinguishable at imaging. Their diagnosis must be made on clinical grounds.

References • • • • • Atlas D, Deyo R. Evaluating and managing acute low back pain in the primary care setting. J Gen Intern Med 2001; 16(2): 120 -131. Brant WE, Helms CA (2006). Fundamentals of diagnostic radiology. Volume IV 3 rd ed. New York, NY: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2010; 1132 -1155. Brower AC, Flemming DJ. Arthritis in black and white. Philadelphia , Pa: Elsevier Saunders, 2012. Duprez TP, Malghem J, Vande Berg BC, et al. Gout in the cervical spine: MR pattern mimicking diskovertebral infection. AJNR Am J Neuroradiology 1996; 17(1): 151 -153. Elhai M, Wipff J, Bazeli R, et al. Radiological cervical spine involvement in young adults with polyarticular JIA. Rheumatology 2013; 52(2): 267 -275. Fardon DF, Williams AL, Dohring EJ, et al. Lumbar disc nomenclature: version 2. 0 : recommendations of the combined task forces of the North American Spine Society, the American Society of Spine Radiology and the American Society of Neuroradiology. Spine J 2014; 14: 2525 – 2545. Gladman DD, Antoni C, Mease P, et al. Psoriatic arthritis and psoriasis: classification, clinical features, pathophysiology, immunology, genetics. Ann Rheum Dis 2005; 64: ii 14 -ii 17. Hahn, YS and Kim, JG. Pathogenesis and clinical manifestations of juvenile rheumatoid arthritis. Korean J Pediatr 2010; 53(11): 921– 930. Hospach T, Maier J, Muller-Abt P, et al. Cervical spine involvement in patients with juvenile idiopathic arthritis: MRI followup study. Pediatr Rheumatol Online J 2014; 12: 9. Jacobson JA, Girish G, Jiang Y, et al. Radiographic evaluation of arthritis: inflammatory conditions. Radiology 2008; 248(2): 378– 389. Kwong Y, Rao N, and Latief K. MDCT findings in Baastrup disease: disease or normal feature of the aging spine? AJR Am J Roentgenol 2011; 196(5): 1156 -1159. Pope TL, Bloem HL, Beltran J, et al. Imaging of the musculoskeletal system. Volume II 1 st ed. Philadelphia, Pa: Elsevier Saunders, 2008. Ristolainen, Kettunen JA, Heliövaara M, et al. Untreated Scheuermann’s disease: a 37 -year follow-up study. Eur Spine J 2012; 21(5): 819 -824. Saetia K, Cho D, Lee S, et al. Ossification of the posterior longitudinal ligament: a review. Neurosurg Focus 2011; 30(3): E 1. Scutellari PN, Galeotti R, Leprotti S, et al. The crowned dens syndrome: evaluation with CT imaging. Radiol Med 2007; 112(2): 195 -207. Talekar K, Flanders A. Imaging algorithm for discitis, epidural, and paraspinal infection. Tech Orthop 2011; 26(4): 256– 261. Weishaupt D, Zanetti M, Hodler J, et al. Painful lumbar disk derangement: relevance of endplate abnormalities at MR imaging. Radiology 2001; 218: 420– 427. World Health Organization Web site. http: //www. who. int/medicines/areas/priority_medicines/Ch 6_24 LBP. pdf. Accessed June 21, 2015. Wu, HT, Morrison WB, Schweitzer, ME. Edematous Schmorl's nodes on thoracolumbar MR imaging: characteristic patterns and changes over time. Skeletal Radiol 2006; 35(4): 212 -219.

- Slides: 40