Oedipus the King and Greek Tragedy The origins

- Slides: 19

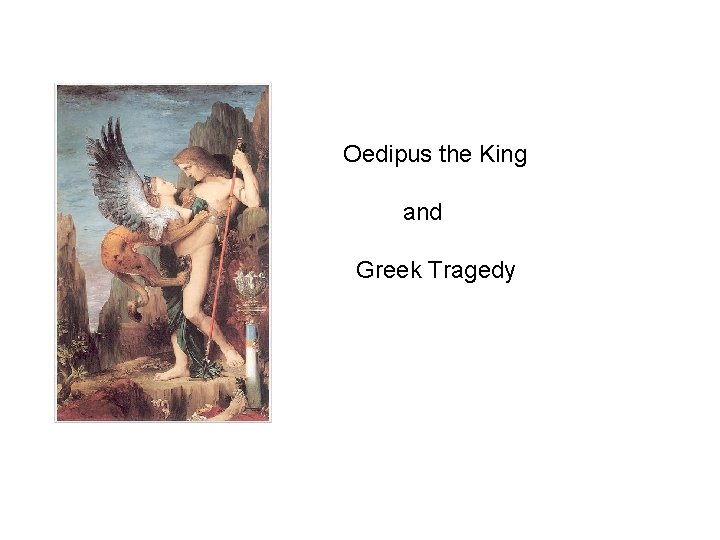

Oedipus the King and Greek Tragedy

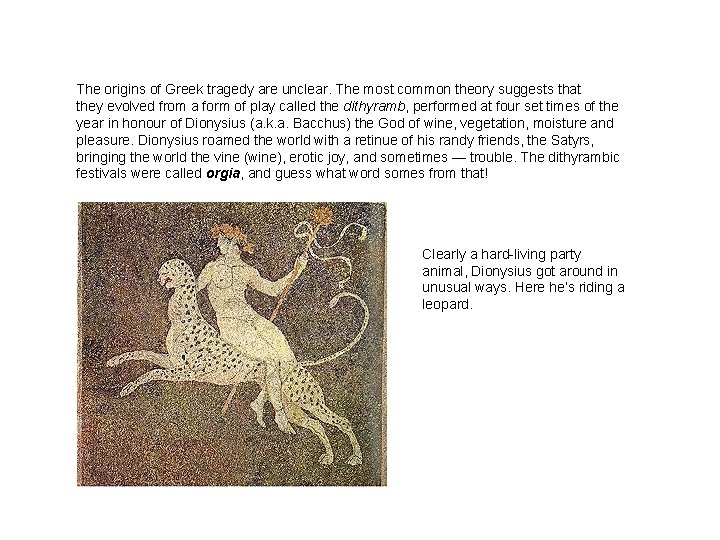

The origins of Greek tragedy are unclear. The most common theory suggests that they evolved from a form of play called the dithyramb, performed at four set times of the year in honour of Dionysius (a. k. a. Bacchus) the God of wine, vegetation, moisture and pleasure. Dionysius roamed the world with a retinue of his randy friends, the Satyrs, bringing the world the vine (wine), erotic joy, and sometimes — trouble. The dithyrambic festivals were called orgia, and guess what word somes from that! Clearly a hard-living party animal, Dionysius got around in unusual ways. Here he’s riding a leopard.

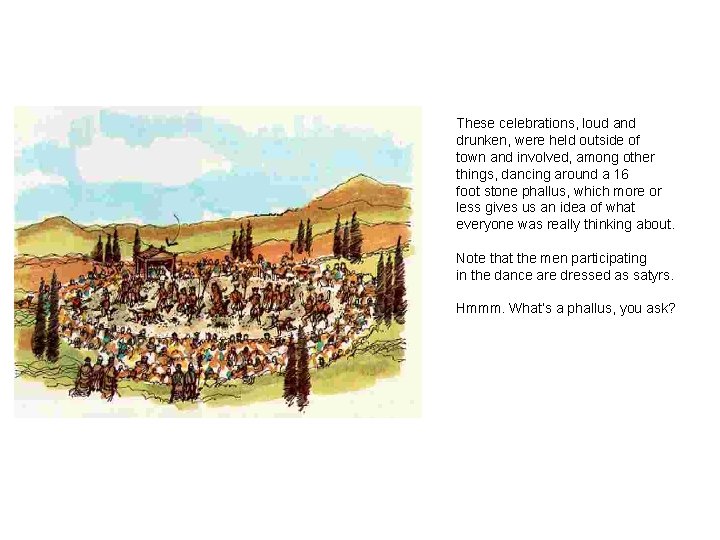

These celebrations, loud and drunken, were held outside of town and involved, among other things, dancing around a 16 foot stone phallus, which more or less gives us an idea of what everyone was really thinking about. Note that the men participating in the dance are dressed as satyrs. Hmmm. What’s a phallus, you ask?

The phallus usually refers to the male penis or sex organ. The word may also refer to a type of mushroom having the cap hanging free around the stem. Any object that visually resembles a penis may be referred to as a "phallus", however, such objects are more correctly refered to as being "phallic. “ No, I am not making this up. No, I will not provide a picture for this slide.

Dionysius hung around with satyrs, creatures described as half ram and half man. Below you will find a “polite” picture of a satyr.

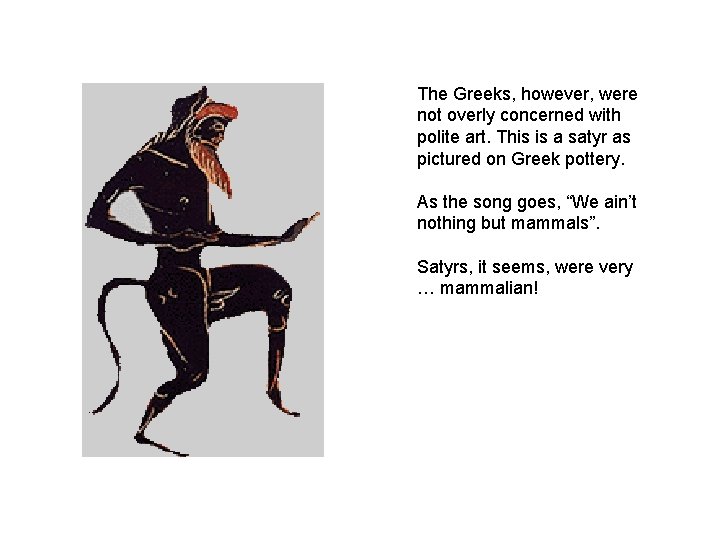

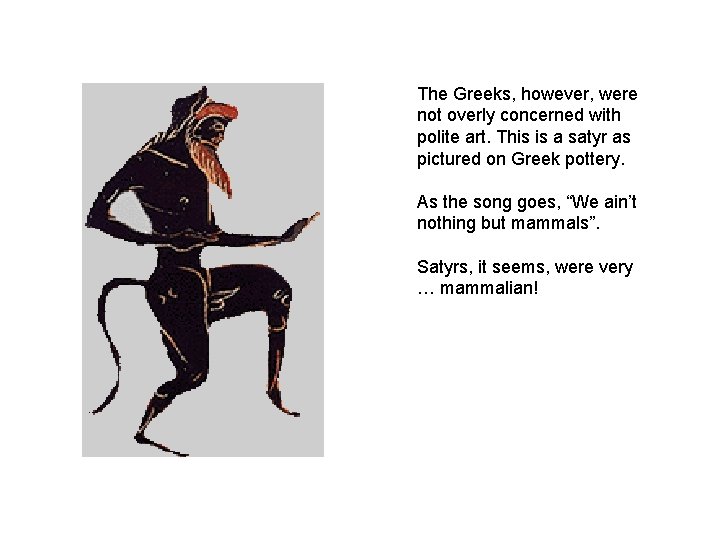

The Greeks, however, were not overly concerned with polite art. This is a satyr as pictured on Greek pottery. As the song goes, “We ain’t nothing but mammals”. Satyrs, it seems, were very … mammalian!

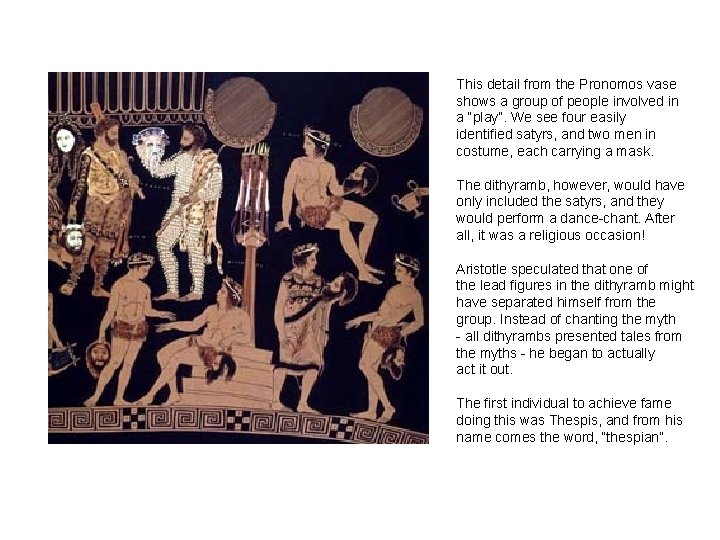

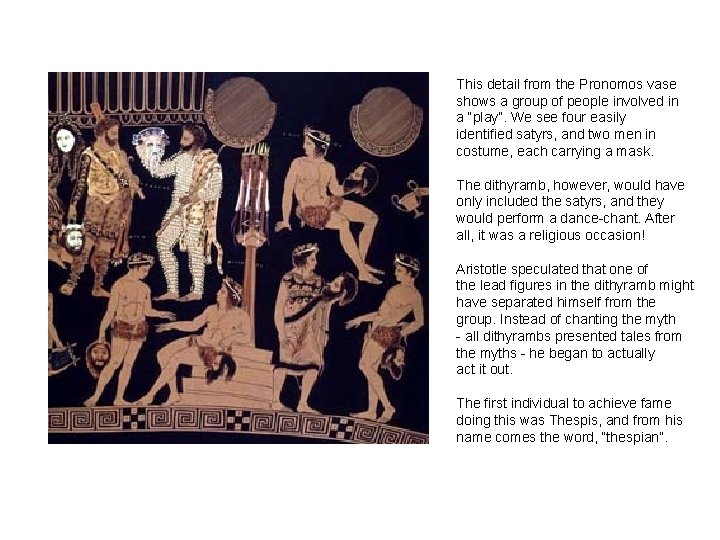

This detail from the Pronomos vase shows a group of people involved in a “play”. We see four easily identified satyrs, and two men in costume, each carrying a mask. The dithyramb, however, would have only included the satyrs, and they would perform a dance-chant. After all, it was a religious occasion! Aristotle speculated that one of the lead figures in the dithyramb might have separated himself from the group. Instead of chanting the myth - all dithyrambs presented tales from the myths - he began to actually act it out. The first individual to achieve fame doing this was Thespis, and from his name comes the word, “thespian”.

If this is true, then this represents the birth of the play in something close to its modern form. For instead of just a chorus, a group performing a dance-chant together, we now had a single actor and a chorus. However, the actor, of necessity, interacted only with the chorus, answering their questions or relating a narrative to them. The great Greek playwright, Aeschylus, added a second actor. Our hero, Sophocles, the greatest of them all, added a third actor! Unheard of! Absurd! But theatre as we know it was born. Aeschylus Sophocles

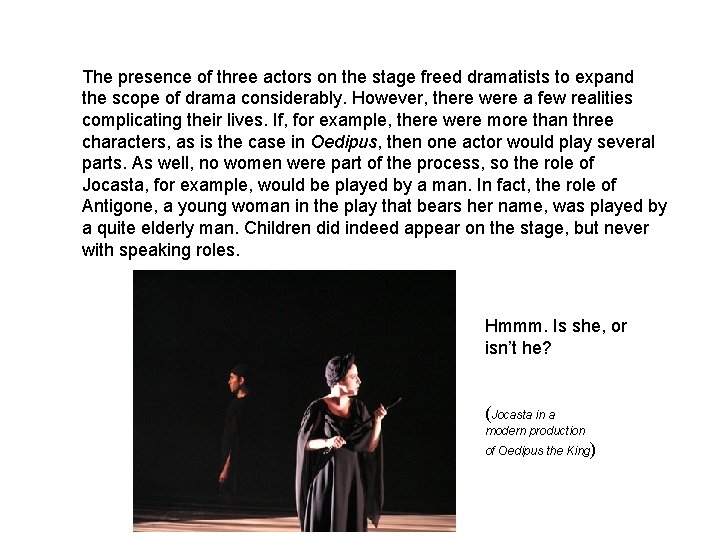

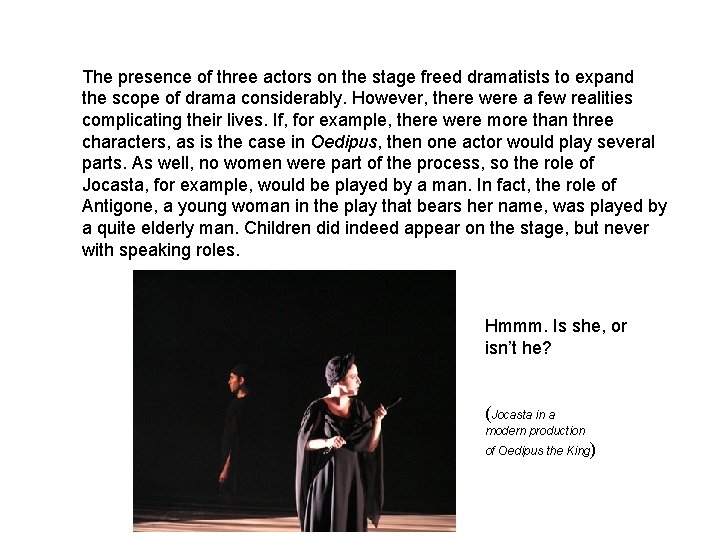

The presence of three actors on the stage freed dramatists to expand the scope of drama considerably. However, there were a few realities complicating their lives. If, for example, there were more than three characters, as is the case in Oedipus, then one actor would play several parts. As well, no women were part of the process, so the role of Jocasta, for example, would be played by a man. In fact, the role of Antigone, a young woman in the play that bears her name, was played by a quite elderly man. Children did indeed appear on the stage, but never with speaking roles. Hmmm. Is she, or isn’t he? (Jocasta in a modern production of Oedipus the King)

While the scope of drama grew far beyond the dithyrambs, tragedy remained linked to Dionysius. In Athens, plays were presented at the Theatre of Dionysius, a large structure capable of holding audiences of 15, 000. While the plays were not themselves religious ritual, they were performed as part of great events honoring the divinities. And like the Olympic Games, the presentation of plays was a competition. Theatre of Dionysius

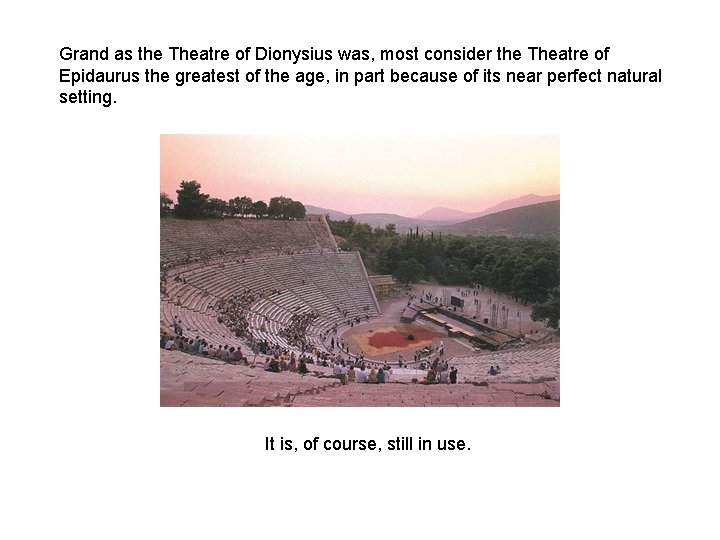

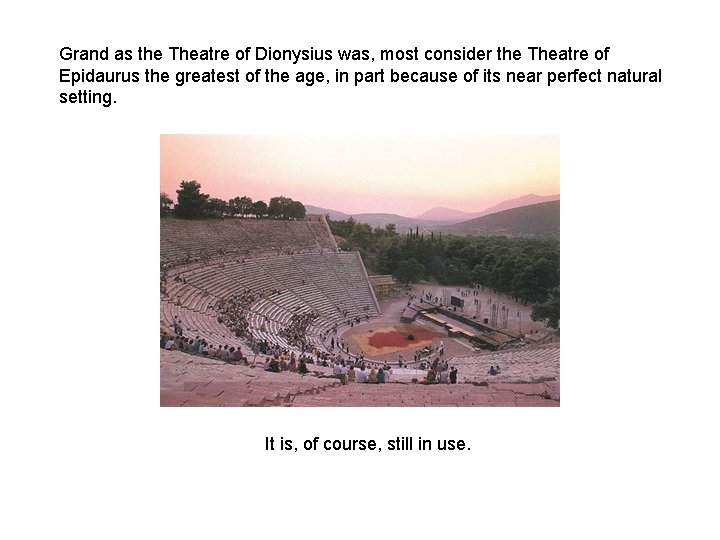

Grand as the Theatre of Dionysius was, most consider the Theatre of Epidaurus the greatest of the age, in part because of its near perfect natural setting. It is, of course, still in use.

During the great competitions, each playwright would present a series of three tragedies and a satyr play. A Satyr play was a burlesque comedy performed as comic relief after a classical Greek tragic trilogy. “Burlesque" was originally a form of art that mocked by imitation. It was often ridiculous in that it imitated several styles and combined imitations of authors and artists with absurd descriptions. Burlesque is a term covering a host of fairly raunchy musical comedy shows, often incorporating social satire. Popular in the 20’s and 30’s, it is once again staging a comeback.

Sophocles won many of these competitions. But before looking at him specifically, let’s examine what became of the chorus after the evolution of tragedy from dithyramb to the works of Sophocles. Chorus (defined): 1. A group of masked dancers who performed ceremonial songs at religious festivals in early Greek times. 2. The group in a classical Greek drama whose songs and dances present an exposition of or, in later tradition, a disengaged commentary on the action. 3. The portion of a classical Greek drama consisting of choric dance and song. http: //www. theatrehistory. com/ancient/chorus 001. html

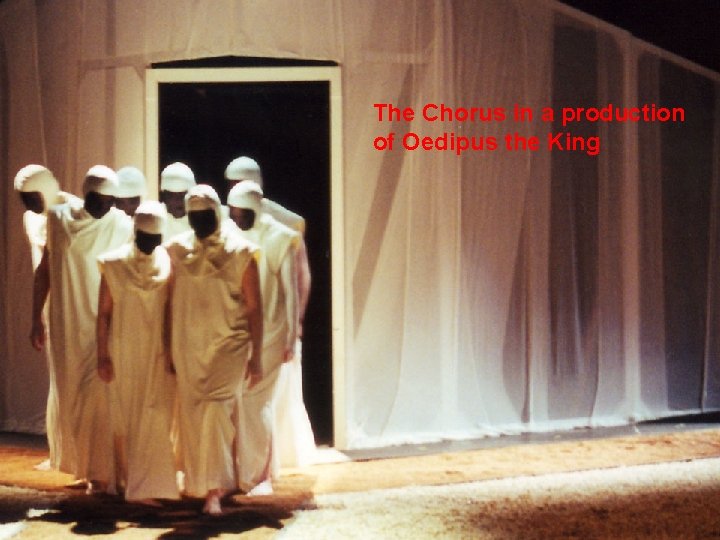

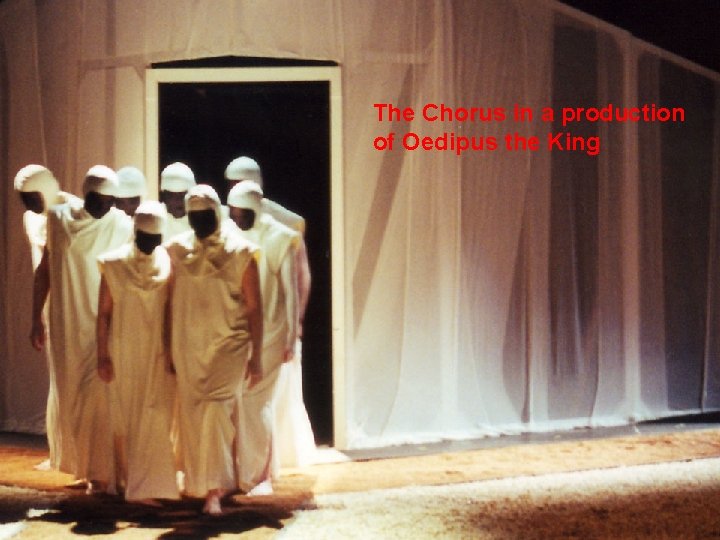

The Chorus in a production of Oedipus the King

In classical tragedy, the chorus represented a kind of “everyman”. In the play we are studying, they are the citizens of Corinth, the common people. By watching and listening to them, we gain a clearer understanding of Oedipus. This is achieved via contrast. The chorus is a kind of “foil” to Oedipus. Foil A character in a play who sets off the main character or other characters by comparison. In Shakespeare's "Romeo and Juliet" Benvolio and Mercutio are young men who behave very differently to Romeo

The chorus sings and “dances”. We are not entirely sure what form the dances took. However, certain terms do provide clues. Choral songs in tragedy are often divided into three sections: strophe ("turning, circling"), antistrophe ("counter-turning, countercircling") and epode ("after-song"). So perhaps the chorus would dance one way around the orchestra ("dancing-floor") while singing the strophe, turn another way during the antistrophe, and then stand still during the epode. Other key terms: Prologue: spoken by one (or two) characters at the beginning of the play. Episode: the dramatic segments in the play when the chorus and characters talk. Stasimon: a choral ode performed by the chorus after each episode.

The chorus usually numbered twelve. Sophocles increased this to fifteen. When they sang and danced, they were accompanied by an auletes – a flute player.

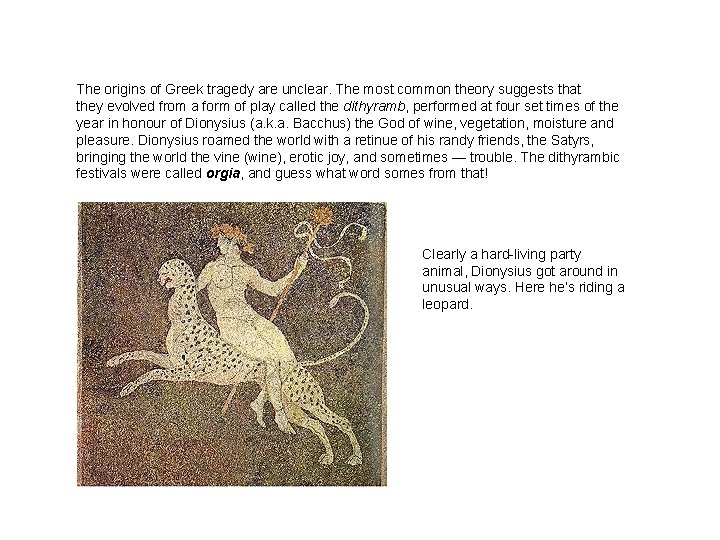

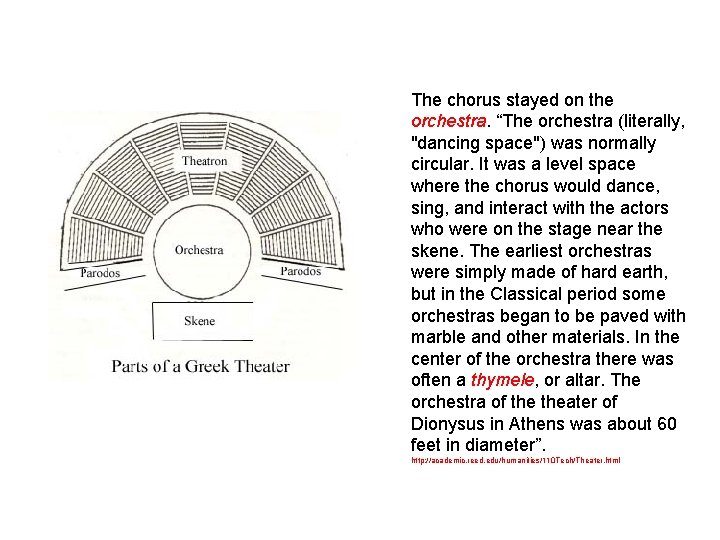

The chorus stayed on the orchestra. “The orchestra (literally, "dancing space") was normally circular. It was a level space where the chorus would dance, sing, and interact with the actors who were on the stage near the skene. The earliest orchestras were simply made of hard earth, but in the Classical period some orchestras began to be paved with marble and other materials. In the center of the orchestra there was often a thymele, or altar. The orchestra of theater of Dionysus in Athens was about 60 feet in diameter”. http: //academic. reed. edu/humanities/110 Tech/Theater. html

The End