Odds Section 3 Lets talk about one of

Odds Section 3

Let’s talk about one of the biggest applications of probability, GAMBLING!!

Simple Gambling Game Suppose I offer a game in which you pay a dollar to guess the outcome of next die roll I make. If you guess incorrectly, I keep your dollar. : ) If you guess correctly, not only do you get your dollar back, but I pay you an additional dollar. Question: Is this a fair game? Answer: NO!

How to make this game fair The problem is that the payout of $1 is far too low. The probability of winning the game once is ⅙, meaning that on average, you will win only once every six games and lose the remaining 5 games. If you are paying $1 for each game you lose, the payouts when you win should cover the costs of those lost games.

How to make this game fair A fair version of this game would have a winning payout of $5. On average, the one time you win in each six games will make up for the five other times you lost $1. In the long run, you should break even from this game.

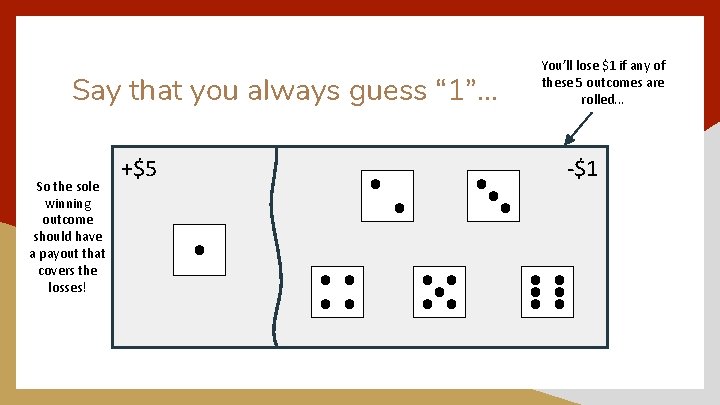

Say that you always guess “ 1”. . . So the sole winning outcome should have a payout that covers the losses! +$5 You’ll lose $1 if any of these 5 outcomes are rolled. . . -$1

A Slightly Different Game Same game as before, but this time you pay $1 to make TWO guesses for the outcome of my next die roll. If one of your guesses is correct, you get back your dollar and I pay you an additional $5. Question: Is this a fair game? Answer: NO! (for me this time)

A Slightly Different Game On average, for every six games, you will lose four times and win twice. So if you lose $4 for those four losses, your two wins should have a total payout of $4 in order for this to be a fair game. So, each win should have a payout of $4/2 = $2.

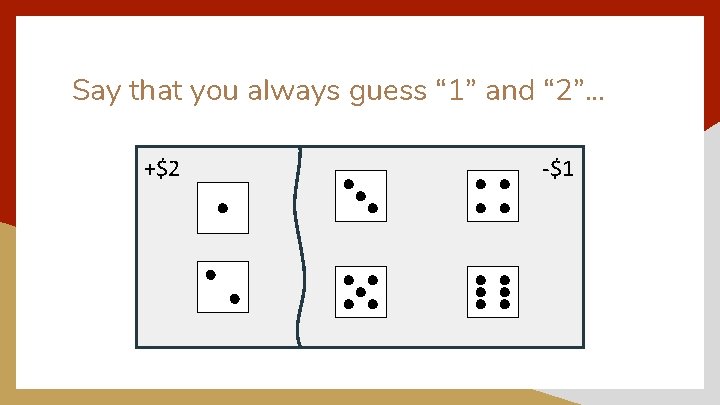

Say that you always guess “ 1” and “ 2”. . . +$2 -$1

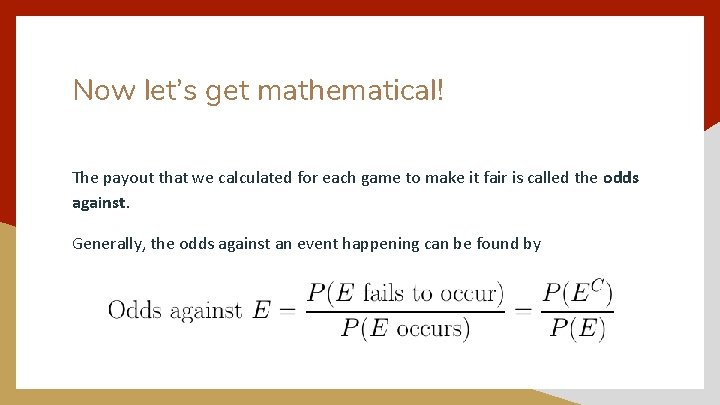

Now let’s get mathematical! The payout that we calculated for each game to make it fair is called the odds against. Generally, the odds against an event happening can be found by

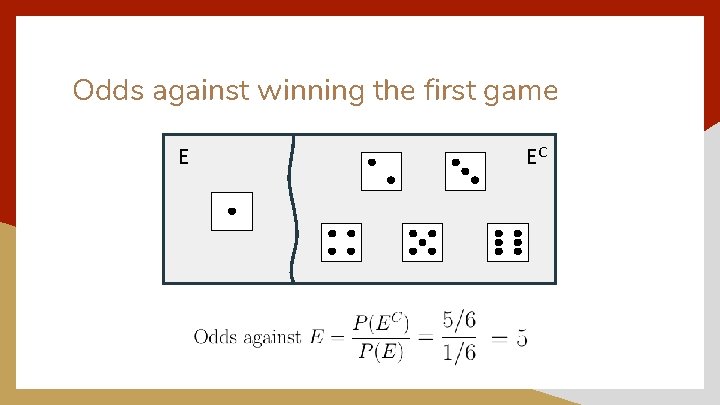

Odds against winning the first game E EC

Odds Against Another way of finding odds against just involves counting the number of outcomes both inside and outside of the event. In practice, we usually say that the odds against something happening as “blank : blank”, or “blank to blank”. So for the last calculation, we’d say the odds against are 5: 1 or 5 to 1 instead of just the number 5.

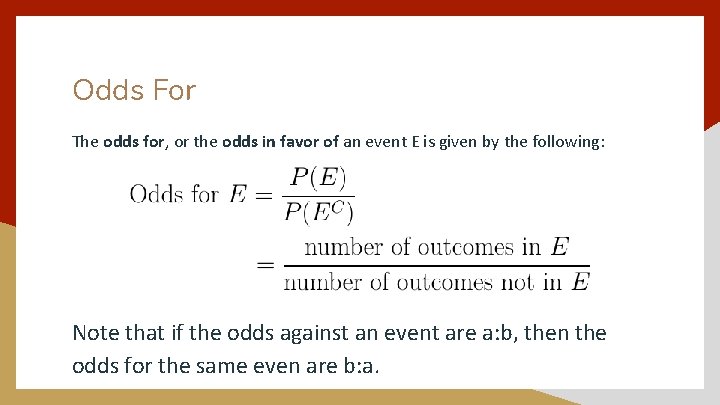

Odds For The odds for, or the odds in favor of an event E is given by the following: Note that if the odds against an event are a: b, then the odds for the same even are b: a.

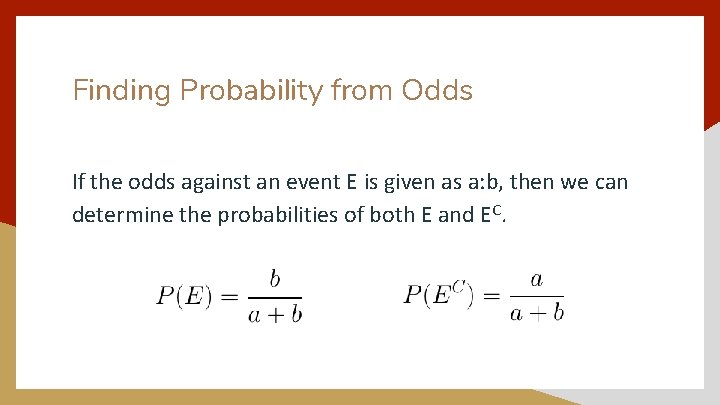

Finding Probability from Odds If the odds against an event E is given as a: b, then we can determine the probabilities of both E and EC.

Question Is anything TRULY random?

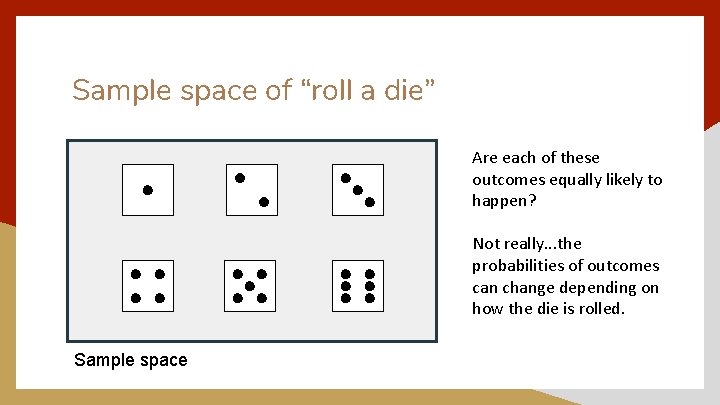

Sample space of “roll a die” Are each of these outcomes equally likely to happen? Not really. . . the probabilities of outcomes can change depending on how the die is rolled. Sample space

Dice Throws - Predictable? In 2012, physicists at the Technical University of Lodz in Poland were able to find a way to predict dice throws, when considering such properties as the viscosity of the air, the friction of the table, etc.

Drawing a Card A deck of playing cards always starts in a certain order; by suit and then by rank. The way most people shuffle cards - called the riffle shuffle - might not mix the cards well enough from its starting order. Mathematicians discovered in 1992 that it takes at least 7 riffle shuffles to sufficiently mix a deck of 52 playing cards.

Generating “random” numbers on a computer Random numbers generated on computers aren’t truly random. We call them pseudorandom numbers, because they are practically unpredictable for humans, but do rely on patterns. These pseudorandom numbers might depend on a determined sequence in a program’s library, or may use a computer’s real time clock as input. If someone were to understand these functions, they could accurately predict the outcome of a pseudorandom number generator.

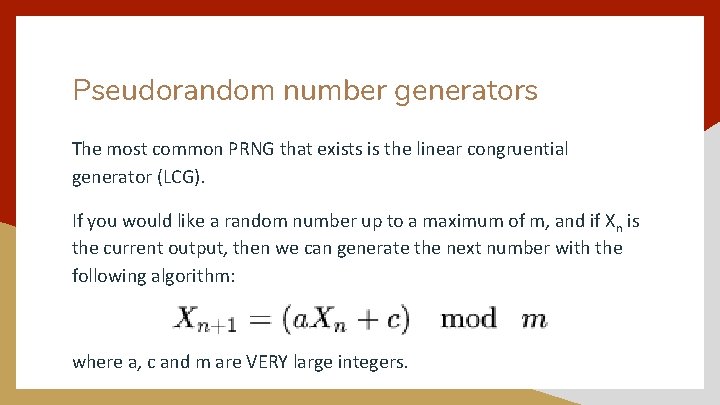

Pseudorandom number generators The most common PRNG that exists is the linear congruential generator (LCG). If you would like a random number up to a maximum of m, and if Xn is the current output, then we can generate the next number with the following algorithm: where a, c and m are VERY large integers.

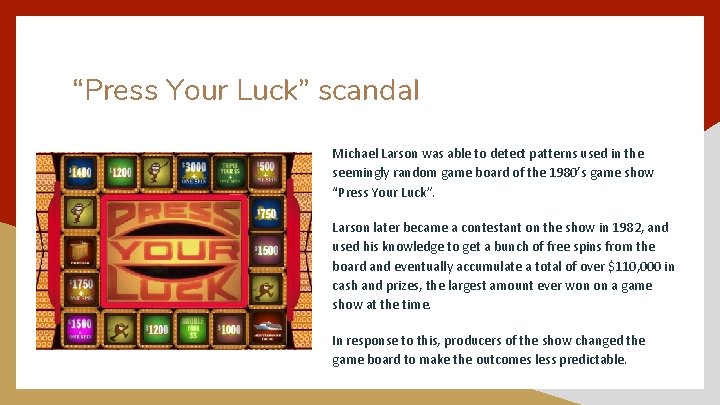

“Press Your Luck” scandal Michael Larson was able to detect patterns used in the seemingly random game board of the 1980’s game show “Press Your Luck”. Larson later became a contestant on the show in 1982, and used his knowledge to get a bunch of free spins from the board and eventually accumulate a total of over $110, 000 in cash and prizes, the largest amount ever won on a game show at the time. In response to this, producers of the show changed the game board to make the outcomes less predictable.

In conclusion to this rant. . . It may be possible for us humans to predict chaotic experiments, as we gain more knowledge of how the world around us works. However, many of the ways we use to collect random results can still be varied enough for their outcomes to be unpredictable to us.

- Slides: 22