Oceanic ecosystems 1 Tectonics and ocean basin evolution

Oceanic ecosystems 1. Tectonics and ocean basin evolution 2. Late Cenozoic climates (and biogeographic consequences) 3. Ecosystem structure and function 4. Short-term spatio-temporal variations 5. Reef, forest, and smoker communities

Oceanic environments basin oceanic plate area: ecosystem: trench ridge shelf slope continental plate open ocean 60% coastal 10% pelagic neritic terrestrial 30%

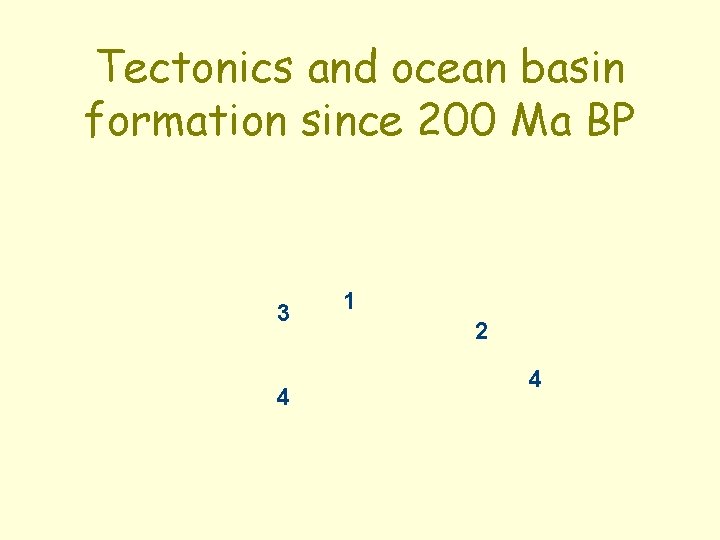

Tectonics and ocean basin formation since 200 Ma BP 3 4 1 2 4

Major Cenozoic changes Tectonic (see previous slide) 1. 2. 3. 4. Opening of Atlantic Ocean Closing of Tethys Sea Closing of Panama gap Opening of Antarctic circulation Climatic a. Climatic cooling in polar latitudes b. Glacio-eustatic changes in relative sea level

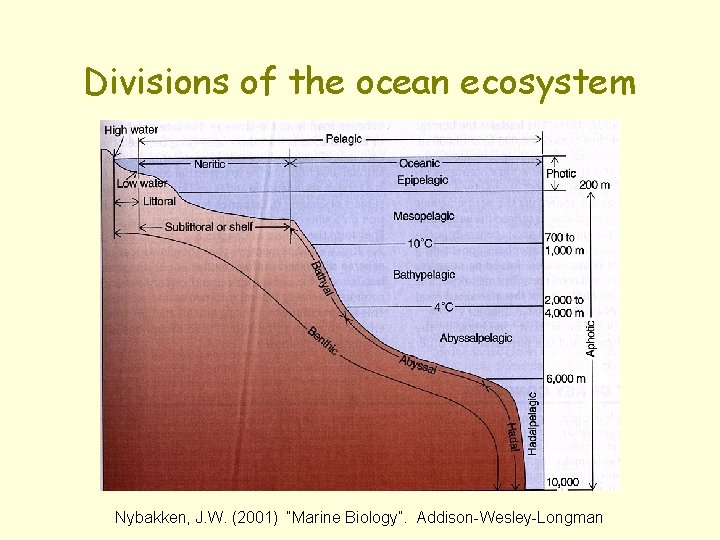

Divisions of the ocean ecosystem Nybakken, J. W. (2001) “Marine Biology”. Addison-Wesley-Longman

Definitions of terms littoral: neritic: pelagic: benthic: abyssal: hadal:

Spatio-temporal variations in sea-surface temperature

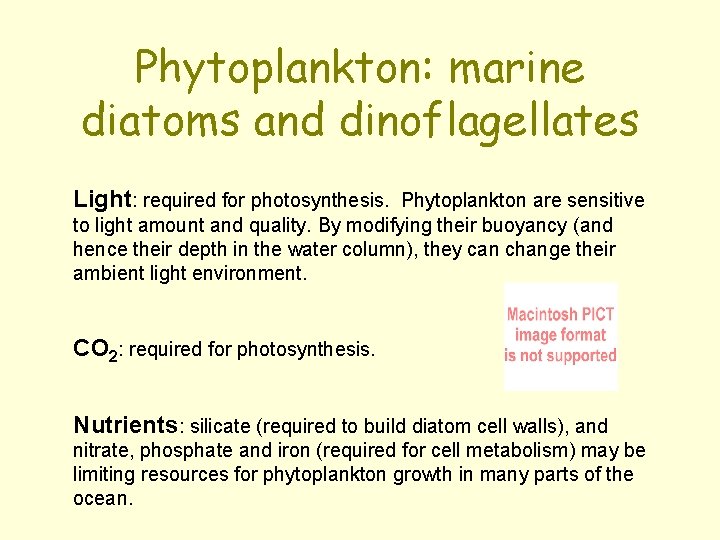

Phytoplankton: marine diatoms and dinoflagellates Light: required for photosynthesis. Phytoplankton are sensitive to light amount and quality. By modifying their buoyancy (and hence their depth in the water column), they can change their ambient light environment. CO 2: required for photosynthesis. Nutrients: silicate (required to build diatom cell walls), and nitrate, phosphate and iron (required for cell metabolism) may be limiting resources for phytoplankton growth in many parts of the ocean.

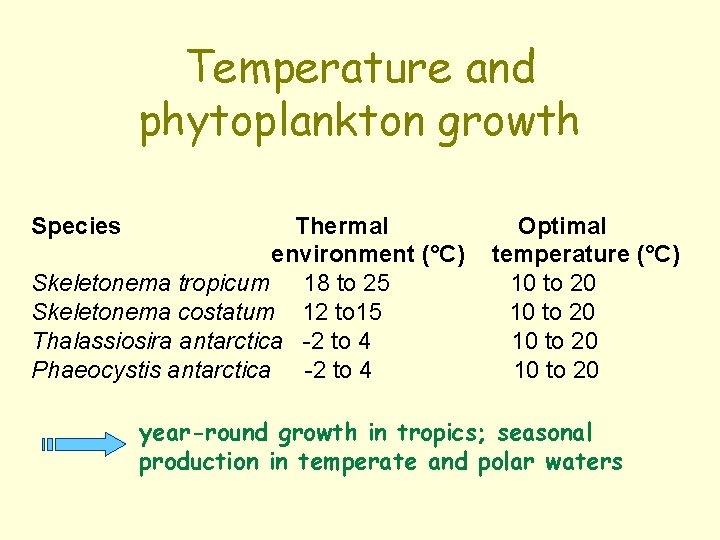

Temperature and phytoplankton growth Species Thermal environment (°C) Skeletonema tropicum 18 to 25 Skeletonema costatum 12 to 15 Thalassiosira antarctica -2 to 4 Phaeocystis antarctica -2 to 4 Optimal temperature (°C) 10 to 20 year-round growth in tropics; seasonal production in temperate and polar waters

Spatio-temporal variations in primary production

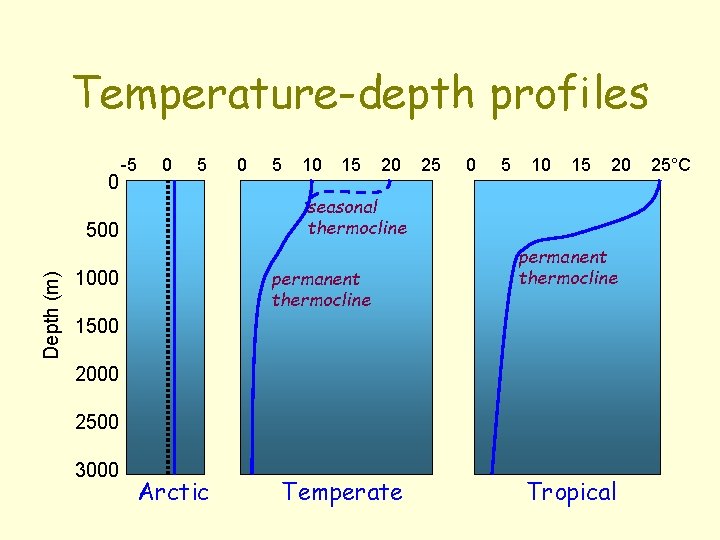

Temperature-depth profiles 0 -5 0 5 5 10 15 20 25 0 5 10 15 20 seasonal thermocline 500 Depth (m) 0 permanent thermocline 1000 permanent thermocline 1500 2000 2500 3000 Arctic Temperate Tropical 25°C

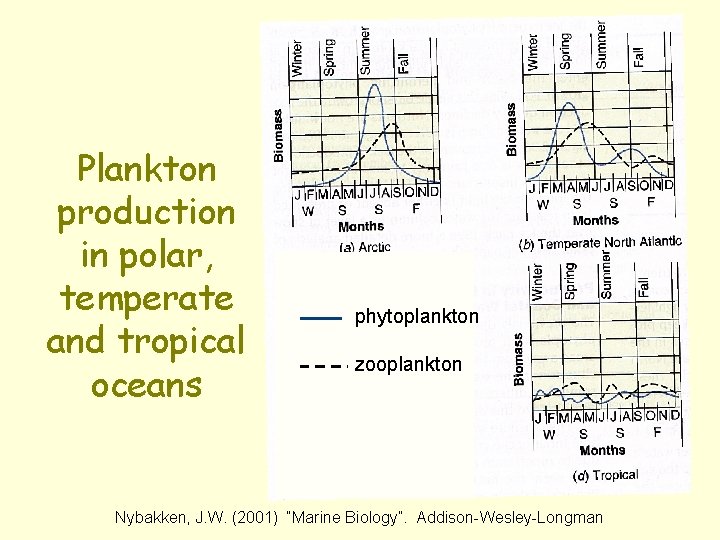

Plankton production in polar, temperate and tropical oceans phytoplankton zooplankton Nybakken, J. W. (2001) “Marine Biology”. Addison-Wesley-Longman

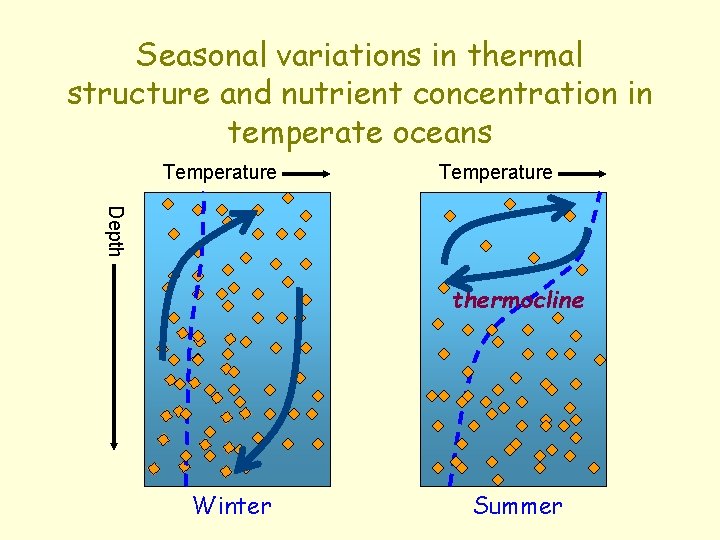

Seasonal variations in thermal structure and nutrient concentration in temperate oceans Temperature Depth thermocline Winter Summer

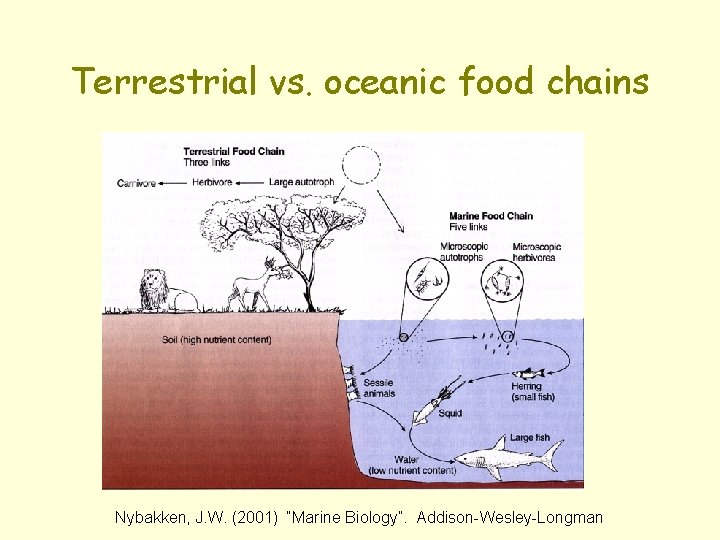

Terrestrial vs. oceanic food chains Nybakken, J. W. (2001) “Marine Biology”. Addison-Wesley-Longman

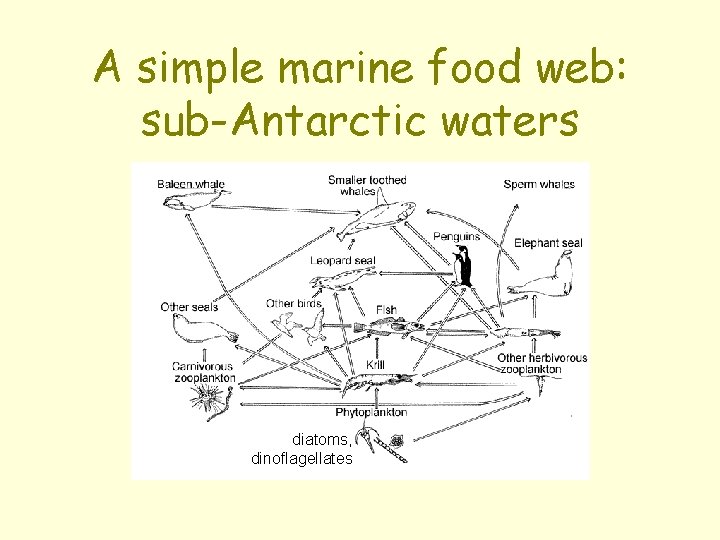

A simple marine food web: sub-Antarctic waters diatoms, dinoflagellates

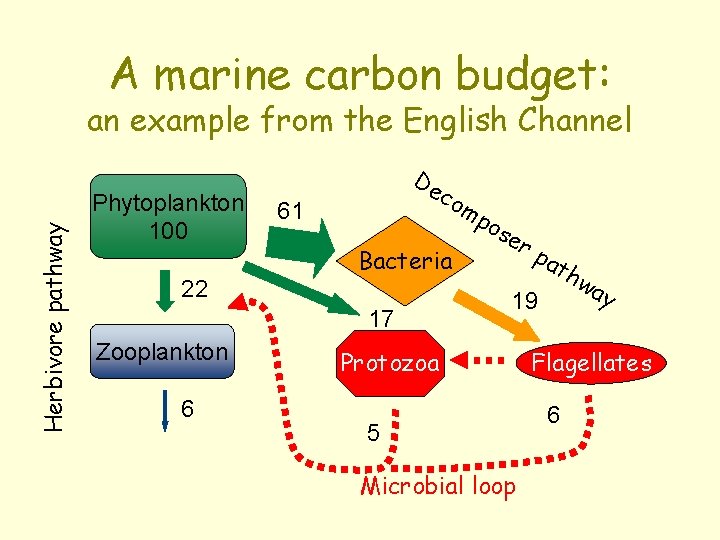

A marine carbon budget: Herbivore pathway an example from the English Channel Phytoplankton 100 22 De co mp 61 Bacteria 17 Zooplankton 6 os e rp at hw a 19 Protozoa 5 Microbial loop y Flagellates 6

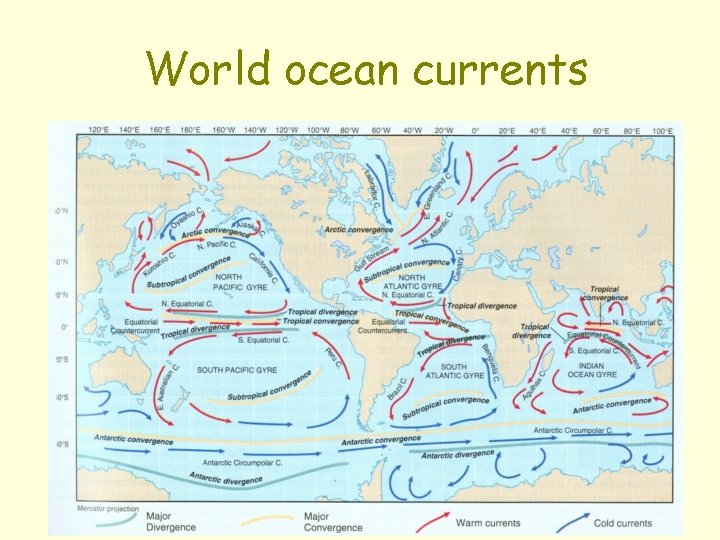

World ocean currents

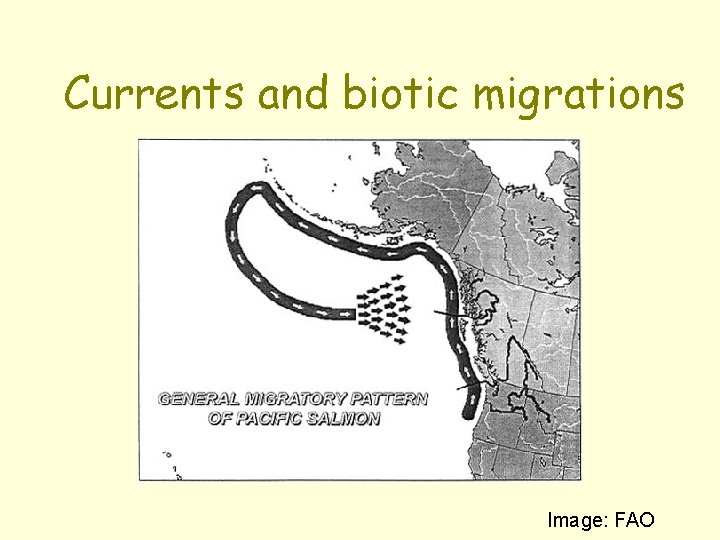

Currents and biotic migrations Image: FAO

Seasonal variations in circulation L H Maps: Thompson et al. , 1989. “Vancouver Island coastal current…

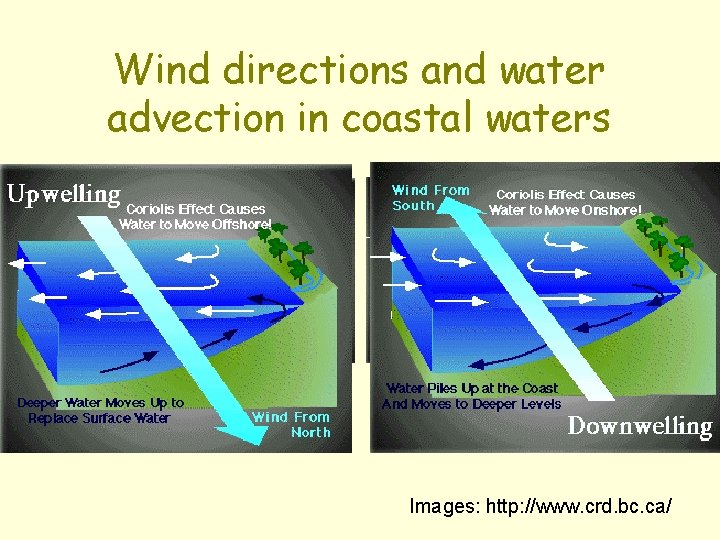

Wind directions and water advection in coastal waters Images: http: //www. crd. bc. ca/

Upwelling zones

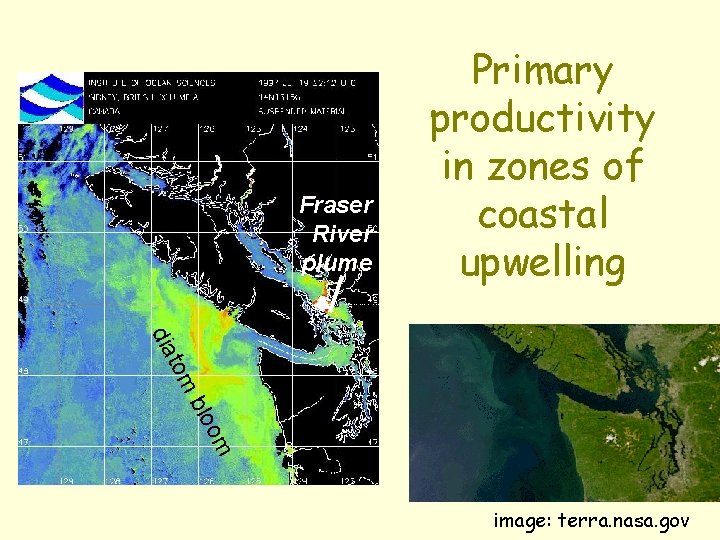

Fraser River plume Primary productivity in zones of coastal upwelling om t dia m o blo image: terra. nasa. gov

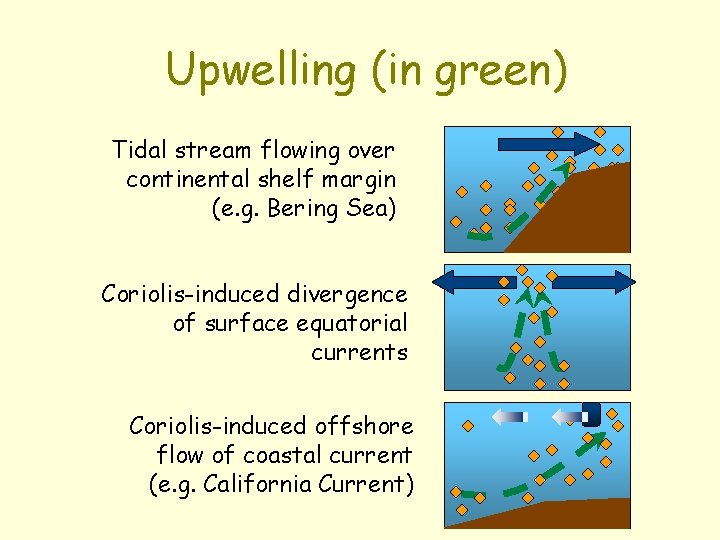

Upwelling (in green) Tidal stream flowing over continental shelf margin (e. g. Bering Sea) Coriolis-induced divergence of surface equatorial currents Coriolis-induced offshore flow of coastal current (e. g. California Current)

Ocean Fronts and Eddies FRONT: the interface between two water masses with differing physical characteristics (temperature and salinity) with resulting variations in density. Some fronts which have weak boundaries at the surface have strong “walls” below the surface. The boundary zones are sites of increased biological production. EDDY: a rotating mass of water with a ± uniform physical characteristics. They can be thought of as circular fronts. Their boundaries are associated with increased productivity.

Fronts and eddies: Gulf Stream Labrador Current boundary zone seis. natsci. csulb. edu/rbehl/gulfstream. htm

Oceanic front productivity e n o z l a front

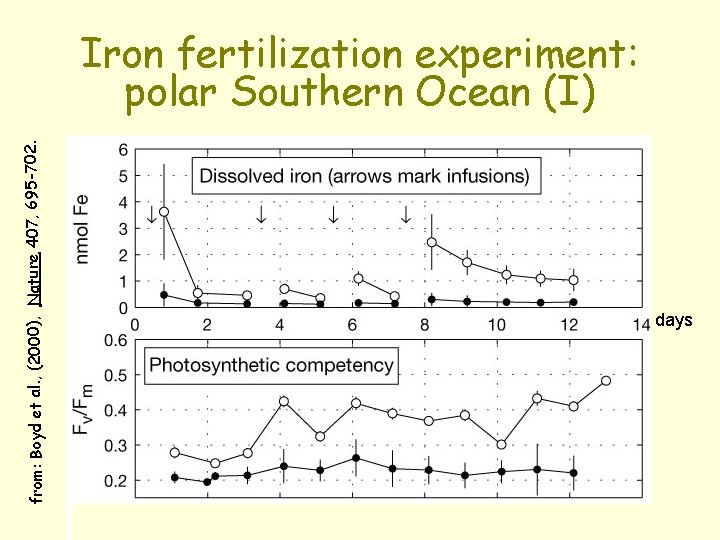

from: Boyd et al. , (2000), Nature 407, 695 -702. Iron fertilization experiment: polar Southern Ocean (I) days

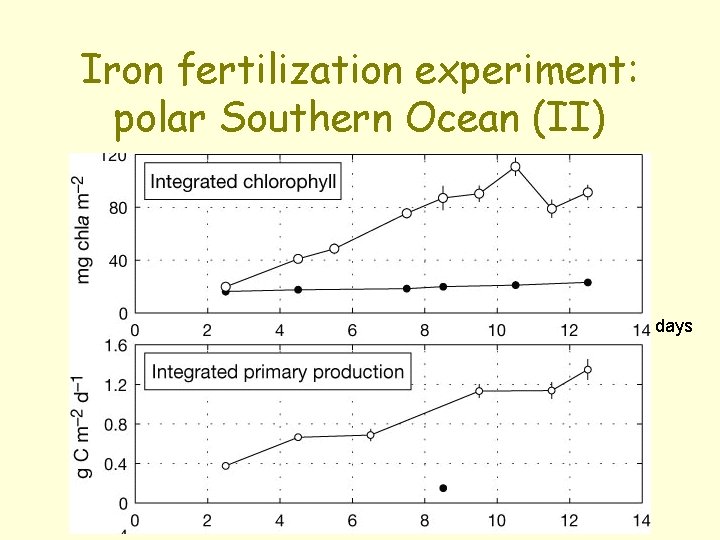

Iron fertilization experiment: polar Southern Ocean (II) days

Sahara dust storm over adjacent Atlantic Ocean image: terra. nasa. gov

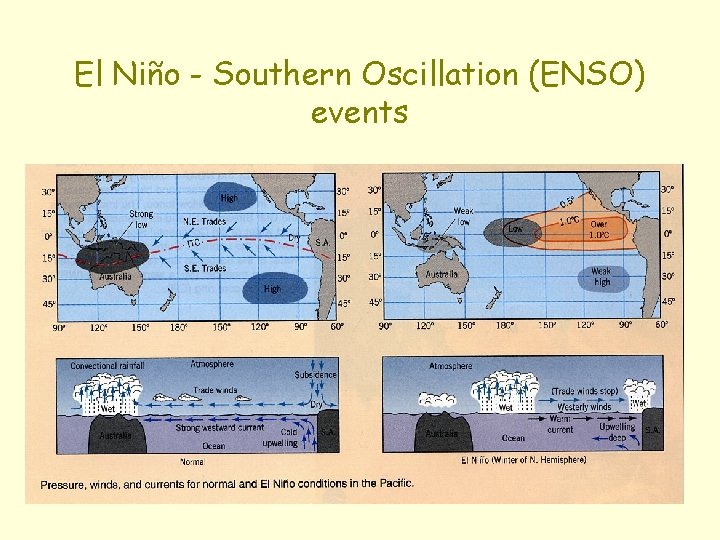

El Niño - Southern Oscillation (ENSO) events

El Niño (1982 -83) High SSTs and reduced upwelling of nutrients in eastern tropical Pacific Ocean

Sea level and thermocline depth variations in the central Pacific during the El Niño event of 1997 -8

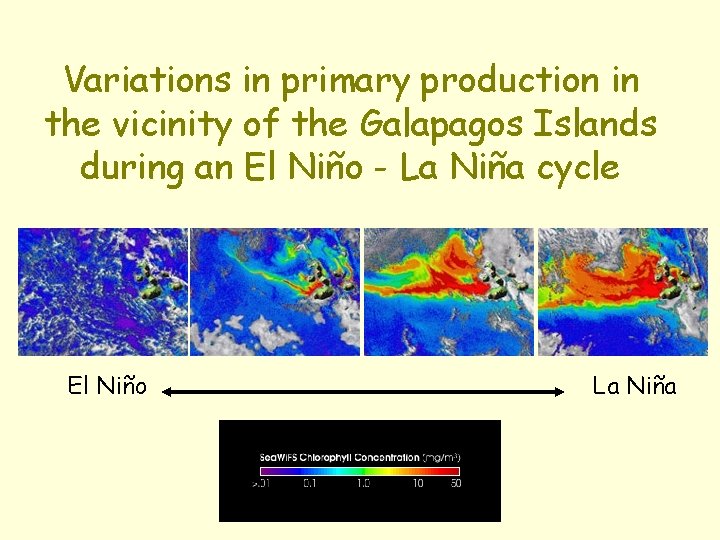

Variations in primary production in the vicinity of the Galapagos Islands during an El Niño - La Niña cycle El Niño La Niña

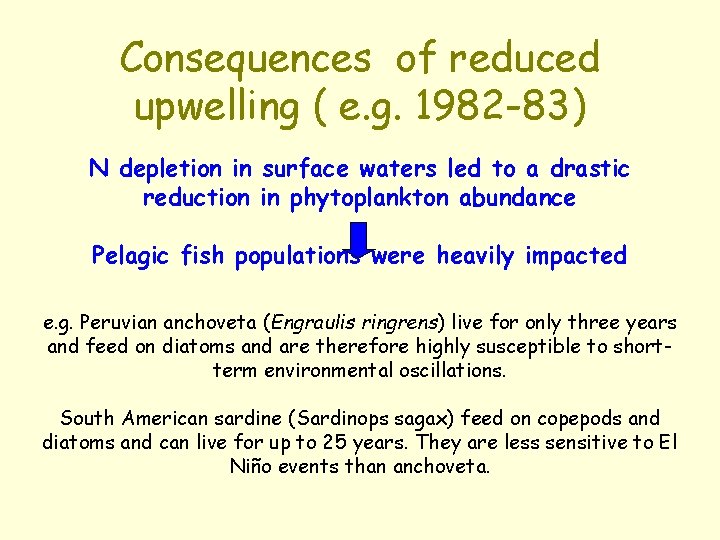

Consequences of reduced upwelling ( e. g. 1982 -83) N depletion in surface waters led to a drastic reduction in phytoplankton abundance Pelagic fish populations were heavily impacted e. g. Peruvian anchoveta (Engraulis ringrens) live for only three years and feed on diatoms and are therefore highly susceptible to shortterm environmental oscillations. South American sardine (Sardinops sagax) feed on copepods and diatoms and can live for up to 25 years. They are less sensitive to El Niño events than anchoveta.

Peruvian anchovy landings and El Niño events major minor

Marine iguanas Sea lions and fur seals Ecological consequences of El Niño events

Decadal-scale fluctuations: the Pacific Decadal Oscillation SST anomalies “warm phase” “cool phase”

PDO regime shifts and ecological consequences Russian sockeye catch

Deep-sea communities Feed on organic particles in ooze that accumulates on ocean floor at rates of <0. 01 mm yr-1. Sediment includes aeolian deposits and biogenic detritus.

Deep-sea communities • Largely (~80%) sediment deposit feeders; • Predators include crustaceans and primitive fish; • Spatially and temporally variable, despite apparent locally uniform water masses; • Diverse (= numerous sediment microhabitats and heavy predation? ) but poorly known; ? 10 M species yet to be described from deep-sea sediments.

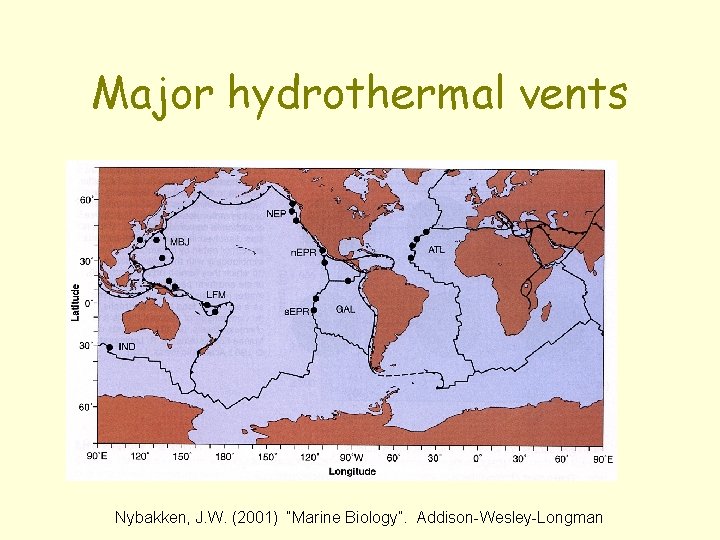

Major hydrothermal vents Nybakken, J. W. (2001) “Marine Biology”. Addison-Wesley-Longman

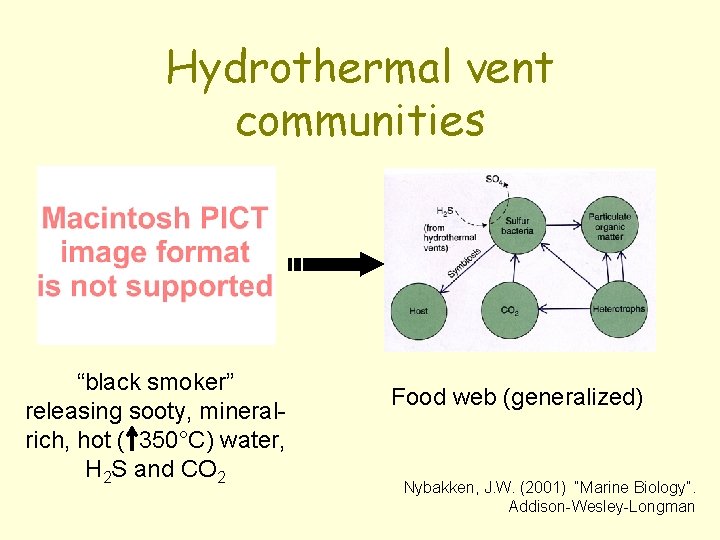

Hydrothermal vent communities “black smoker” releasing sooty, mineralrich, hot ( 350°C) water, H 2 S and CO 2 Food web (generalized) Nybakken, J. W. (2001) “Marine Biology”. Addison-Wesley-Longman

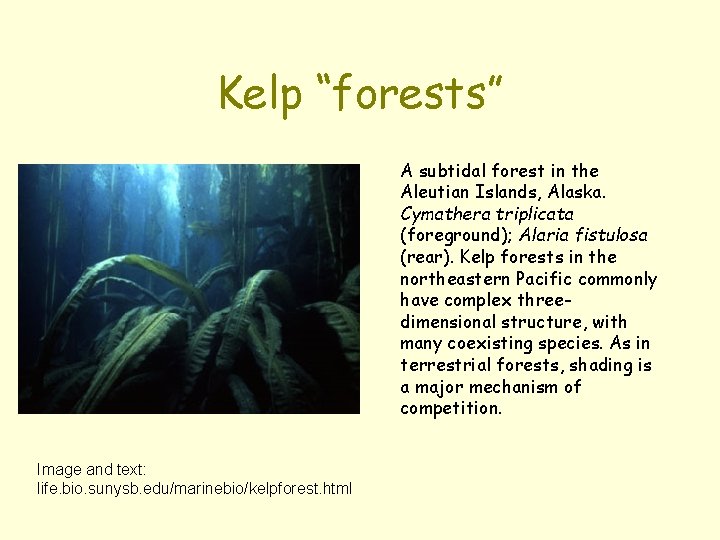

Kelp “forests” A subtidal forest in the Aleutian Islands, Alaska. Cymathera triplicata (foreground); Alaria fistulosa (rear). Kelp forests in the northeastern Pacific commonly have complex threedimensional structure, with many coexisting species. As in terrestrial forests, shading is a major mechanism of competition. Image and text: life. bio. sunysb. edu/marinebio/kelpforest. html

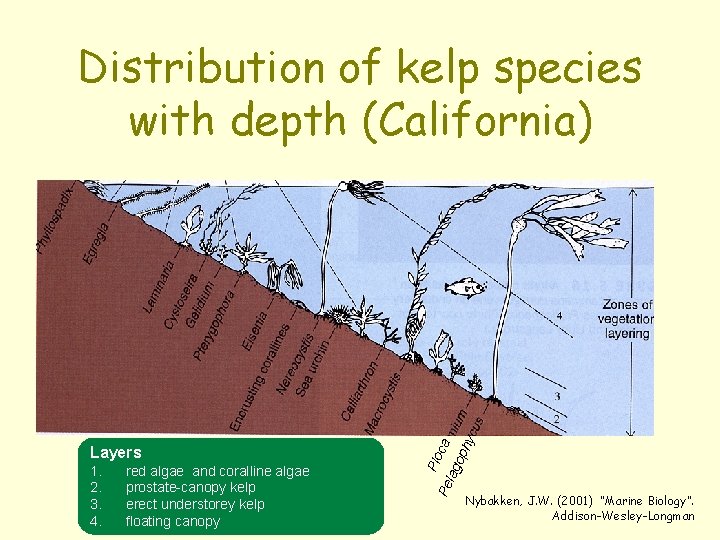

Layers 1. 2. 3. 4. red algae and coralline algae prostate-canopy kelp erect understorey kelp floating canopy P Pe loca lag op hy Distribution of kelp species with depth (California) Nybakken, J. W. (2001) “Marine Biology”. Addison-Wesley-Longman

Kelp biogeography Miocene? 26 genera ~83 spp. 5 genera 11 -18 spp. Pliocene? Pleistocene? 4 genera 10 -12 spp. Originated in north Pacific in early Cenozoic; rapid radiation of new forms; dispersed in mid to late Cenozoic? to N. Atlantic, and in Pleistocene? to southern oceans.

Kelp forest food webs Orcas (1990 s) research. amnh. org/biodiversity/crisis/foodweb. html

Effects of sea otters on species diversity of kelps in southern Alaska no otters present Sea otter harvesting sea urchin otters <2 yr otters >15 yr

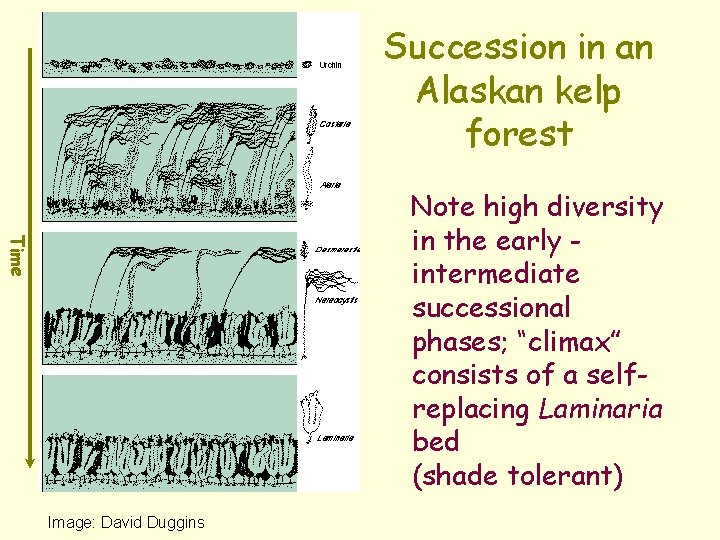

Succession in an Alaskan kelp forest Time Note high diversity in the early intermediate successional phases; “climax” consists of a selfreplacing Laminaria bed (shade tolerant) Image: David Duggins

- Slides: 48